TL;DR#

Existing video understanding benchmarks primarily focus on general-purpose tasks, lacking evaluation of expert-level reasoning in specialized domains. This creates a gap in assessing foundation models’ capabilities in knowledge-intensive video understanding, particularly critical for fields like healthcare and science. The lack of comprehensive benchmarks hinders the development of more robust and capable AI systems.

The paper introduces MMVU, a comprehensive benchmark with 3000 expert-annotated questions across four disciplines. MMVU’s key advancements are its focus on expert-level reasoning using domain-specific knowledge, human expert annotation, and inclusion of reasoning rationales. Evaluation of 32 models reveals a significant gap between model and human performance, offering valuable insights for future research and development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical need for evaluating foundation models’ ability to handle expert-level knowledge in video understanding, a largely unexplored area. Its comprehensive benchmark, MMVU, and in-depth analysis provide valuable insights for future advancements in this field, particularly for specialized domains. This work directly contributes to the development of more robust and capable multimodal AI systems.

Visual Insights#

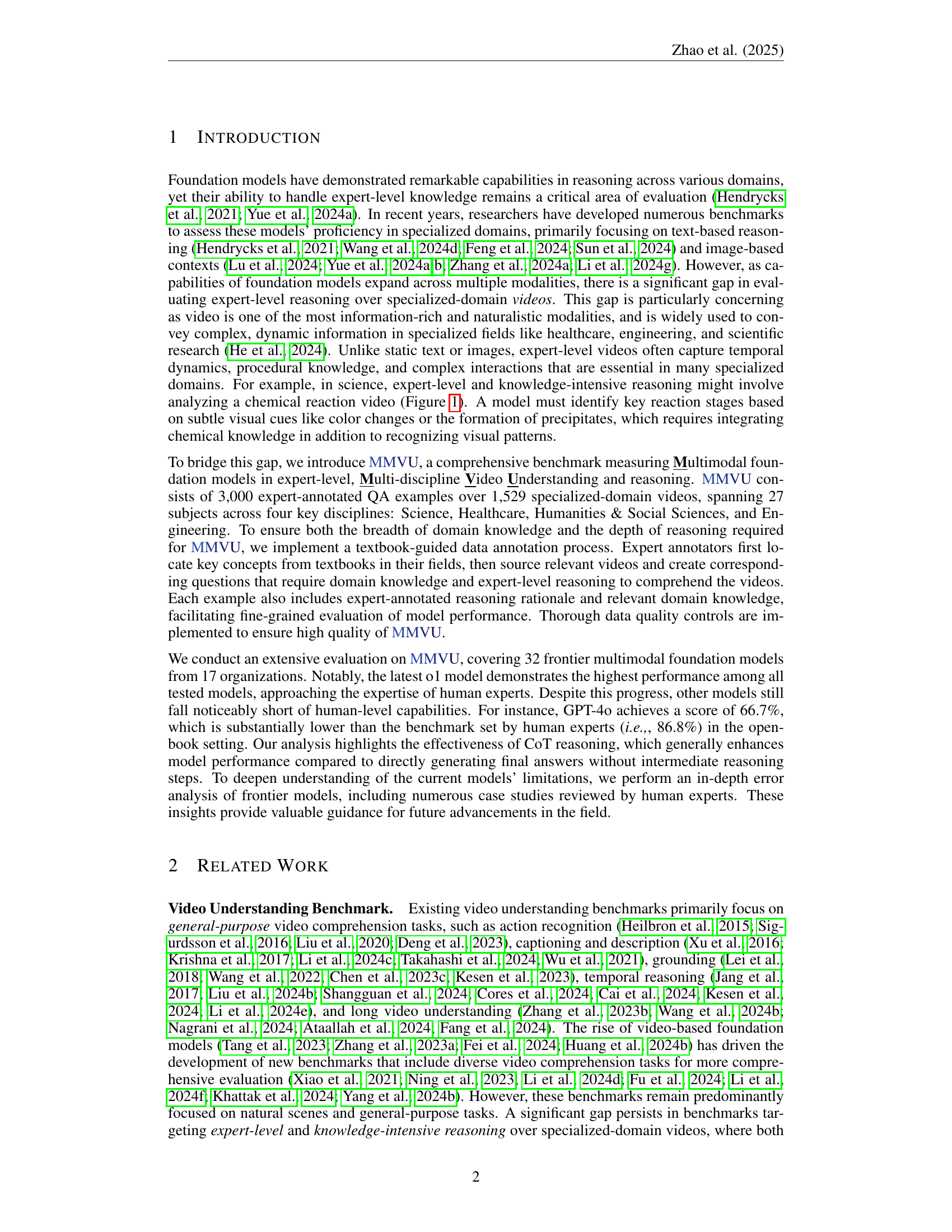

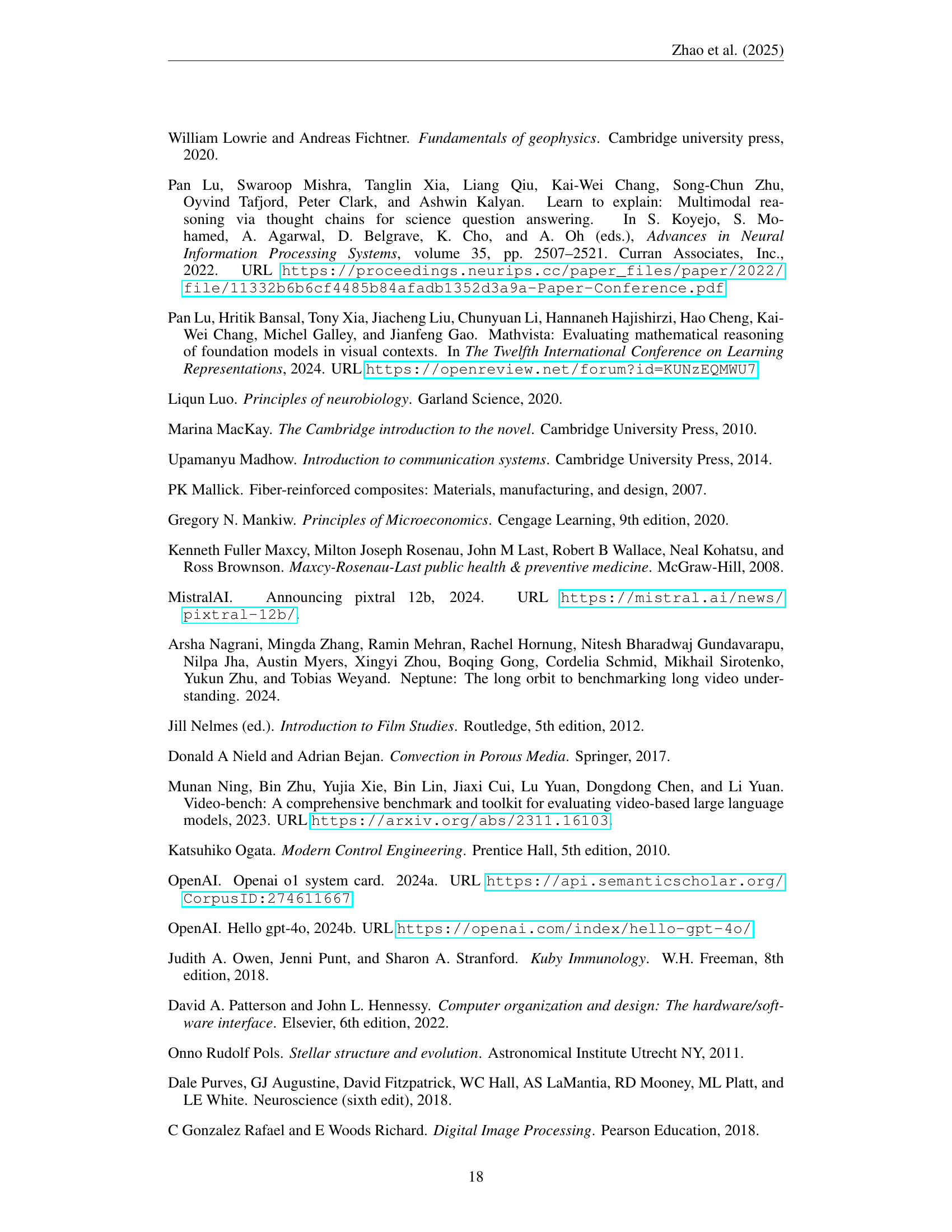

🔼 MMVU is a benchmark dataset for evaluating multimodal foundation models’ ability to understand and reason with videos at an expert level. It contains 3000 expert-annotated question-answer pairs across 27 subjects within four core disciplines: Science, Healthcare, Humanities & Social Sciences, and Engineering. The questions are designed to challenge models’ knowledge and reasoning capabilities by requiring them to analyze specialized videos and apply domain-specific expertise.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of the \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 benchmark. \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 includes 3,000 expert-annotated examples, covering 27 subjects across four core disciplines. It is specifically designed to assess multimodal foundation models in expert-level, knowledge-intensive video understanding and reasoning tasks.

| Project Page: | mmvu-benchmark.github.io | |

| \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 Data: | huggingface.co/datasets/yale-nlp/MMVU | |

| \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 Code: | github.com/yale-nlp/MMVU |

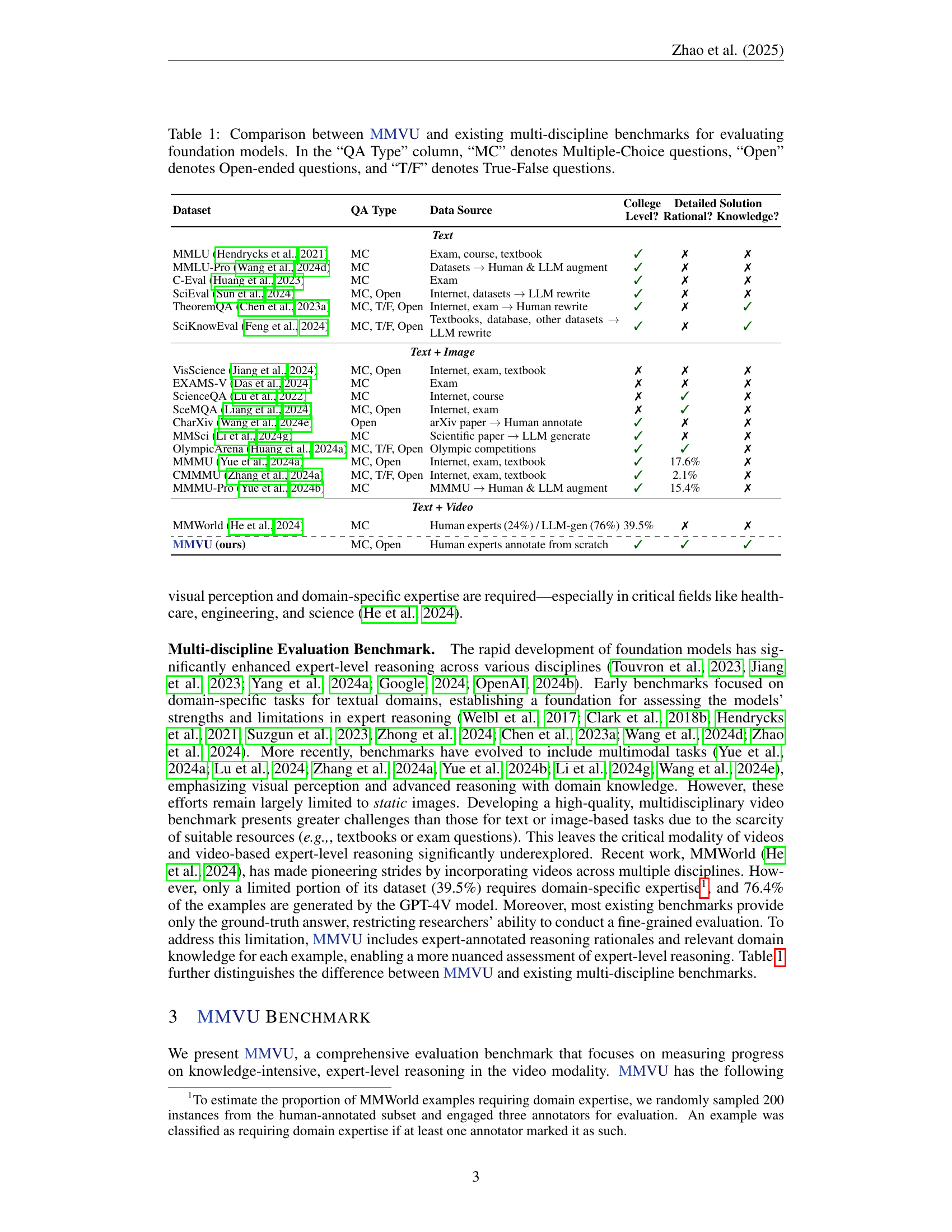

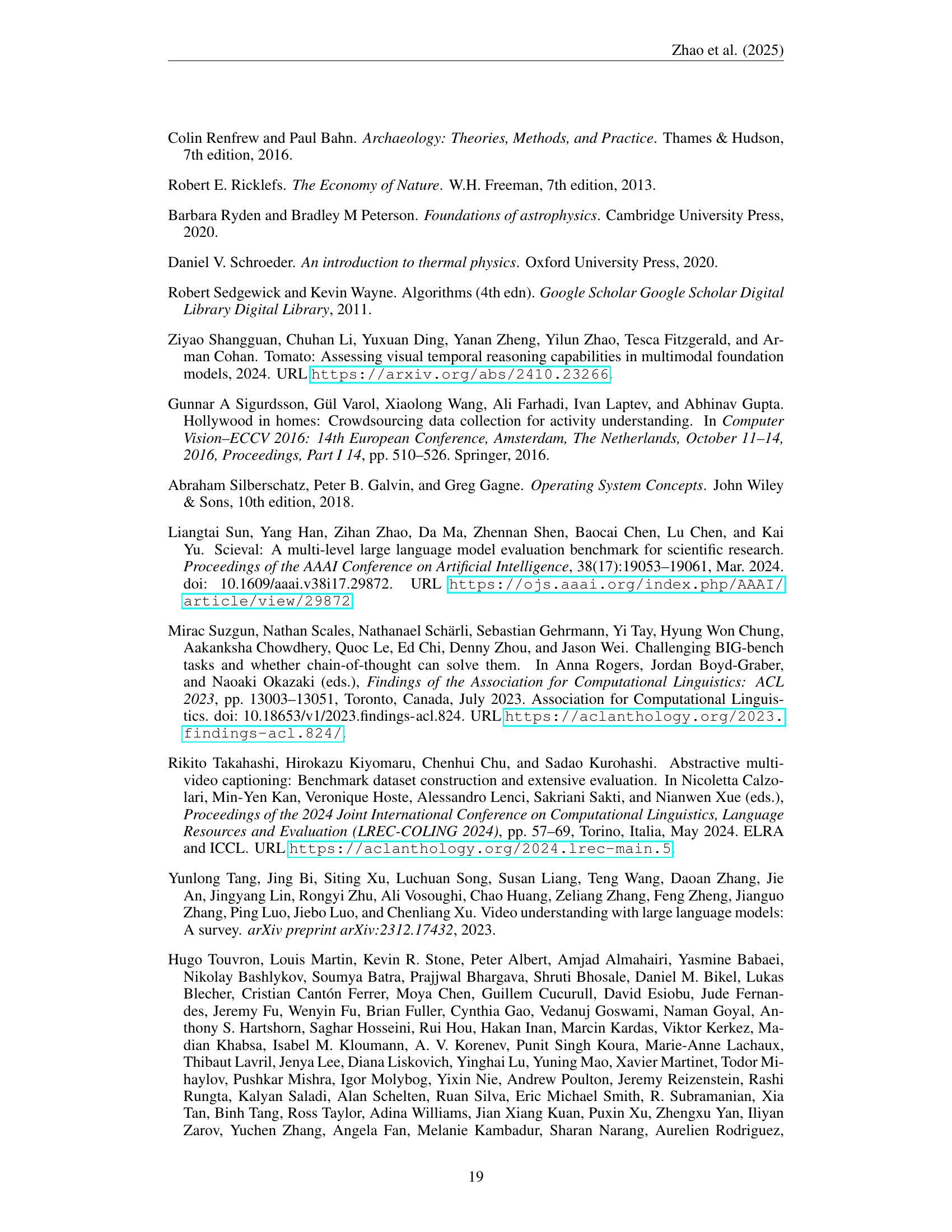

🔼 This table compares the MMVU benchmark with other existing multi-disciplinary benchmarks used for evaluating foundation models. It details key characteristics of each benchmark, including the type of questions (multiple-choice, open-ended, true/false), the source of the data used to create the questions, and whether the benchmark provides detailed solutions, rationales, and domain-specific knowledge for each question. This allows for a comparison of the complexity and depth of reasoning required by each benchmark, and helps to highlight the unique features of MMVU.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison between \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 and existing multi-discipline benchmarks for evaluating foundation models. In the “QA Type” column, “MC” denotes Multiple-Choice questions, “Open” denotes Open-ended questions, and “T/F” denotes True-False questions.

In-depth insights#

MMVU Benchmark#

The MMVU benchmark represents a notable contribution to the field of video understanding by providing a high-quality, expert-level, multi-disciplinary evaluation dataset. Its key strength lies in its focus on expert-level reasoning, moving beyond simple visual perception to assess models’ ability to apply domain-specific knowledge. The textbook-guided annotation process ensures both breadth and depth in the questions, enhancing the evaluation’s rigor. Furthermore, the inclusion of reasoning rationales and domain knowledge allows for fine-grained error analysis, providing valuable insights for future model development. While current models show promise, MMVU highlights the significant challenge of achieving human-level performance in this complex task, suggesting that future research should focus on bridging the gap between model capabilities and expert-level reasoning. The benchmark’s multi-disciplinary nature also offers a broader and more realistic evaluation compared to existing benchmarks focused on specific domains.

Expert Annotation#

Expert annotation in research papers is a crucial process that significantly impacts the quality and reliability of the resulting data. It involves engaging experts in a specific field to carefully label or annotate data points, such as images, videos, or text, according to predefined guidelines. The expertise of annotators is key, ensuring that the annotations are accurate, consistent, and reflect the nuances of the domain. This approach improves data quality by reducing errors and biases that might arise from automated or less experienced annotation methods. High-quality annotations are particularly important when dealing with complex or subtle concepts where machine learning algorithms might struggle. However, expert annotation is resource-intensive, requiring significant time, effort, and financial investments. Careful planning and management are essential to ensure efficiency and effectiveness in the process, potentially incorporating quality control measures to maintain accuracy and consistency. Despite the challenges, expert annotation remains a valuable tool in building accurate and reliable datasets, which can facilitate advancements in various fields, including machine learning research and application.

Model Evaluation#

A robust model evaluation is crucial for assessing the effectiveness of any machine learning model, especially in complex domains like video understanding. A multifaceted approach is needed, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative methods. Quantitative evaluations often focus on metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, but these should be carefully selected and interpreted in the context of the specific task and dataset. Qualitative analysis, on the other hand, involves a deeper examination of model outputs, including error analysis and case studies, which can reveal valuable insights not captured by numerical metrics alone. For video understanding, evaluating the model’s ability to handle temporal dynamics and integrate visual and contextual information is particularly important. A comprehensive model evaluation should also consider the model’s efficiency, scalability, and ethical implications, providing a holistic view of its capabilities and limitations.

Qualitative Analysis#

A qualitative analysis of a research paper would delve into a detailed examination of the findings, moving beyond mere statistics to explore the nuances and complexities of the data. It would likely involve in-depth case studies, perhaps focusing on instances where the model’s performance deviated significantly from expected results. Error analysis would be a crucial component, categorizing mistakes by type (e.g., visual perception errors, reasoning failures) and searching for recurring patterns. This approach could highlight limitations in the model’s understanding of specific concepts or its ability to integrate different forms of information such as visual and textual inputs. By examining individual cases, researchers would potentially uncover subtle issues not apparent in aggregate statistics, revealing the model’s strengths and weaknesses with greater granularity. The integration of human expert review is crucial to providing context and verifying the accuracy of the analysis. Ultimately, a well-executed qualitative analysis helps refine the model and potentially lead to advancements in the field.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize developing more robust and comprehensive benchmarks for evaluating multimodal foundation models, particularly focusing on expert-level reasoning in specialized domains. This includes expanding the scope of benchmarks beyond static images and text to encompass more diverse modalities like video, which better reflects real-world scenarios and expert workflows. Addressing the limitations of current models revealed in the analysis will require exploring novel architectures and training techniques such as improving visual perception and incorporating domain-specific knowledge more effectively. Advanced reasoning methods like chain-of-thought prompting show promise but require further refinement and broader application to achieve human-level performance. Finally, investigating the interaction between different modalities and understanding how models integrate information from multiple sources is crucial for advancing the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure illustrates the three-stage pipeline for creating the MMVU benchmark dataset. Stage 1 (Preliminary Setup) involves selecting subjects through a user study and recruiting and training expert annotators. Stage 2 (Textbook-Guided QA Annotation) details the process of collecting videos with Creative Commons licenses, creating question-answer pairs, and annotating detailed solutions and relevant domain knowledge. The final stage (Quality Control) describes the measures used to ensure data quality, including expert validation and compensation for annotator time spent.

read the caption

Figure 2: An overview of the \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 benchmark construction pipeline.

🔼 Figure 3 shows an example from the MMVU dataset, specifically focusing on a chemistry question. The figure highlights the comprehensive nature of the dataset by showcasing the question, multiple-choice options, relevant textbook information, and a detailed, step-by-step expert-annotated reasoning process. The inclusion of textbook references and rationales demonstrates the level of detail and expert-level knowledge-intensive reasoning that MMVU aims to evaluate in multimodal foundation models.

read the caption

Figure 3: A dataset example from \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 with the discipline of chemistry. Each example in \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 includes expert annotation of relevant domain knowledge and step-by-step reasoning rational.

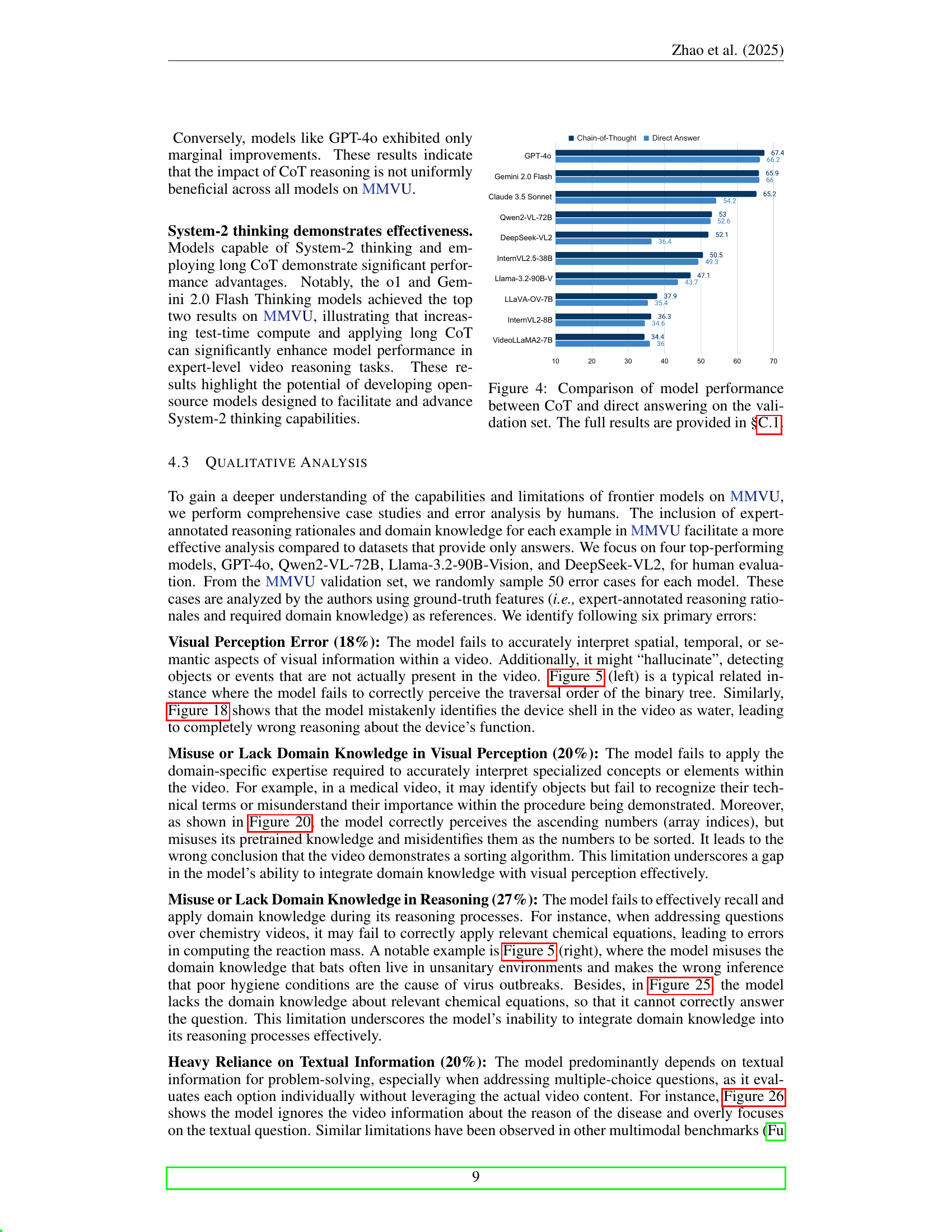

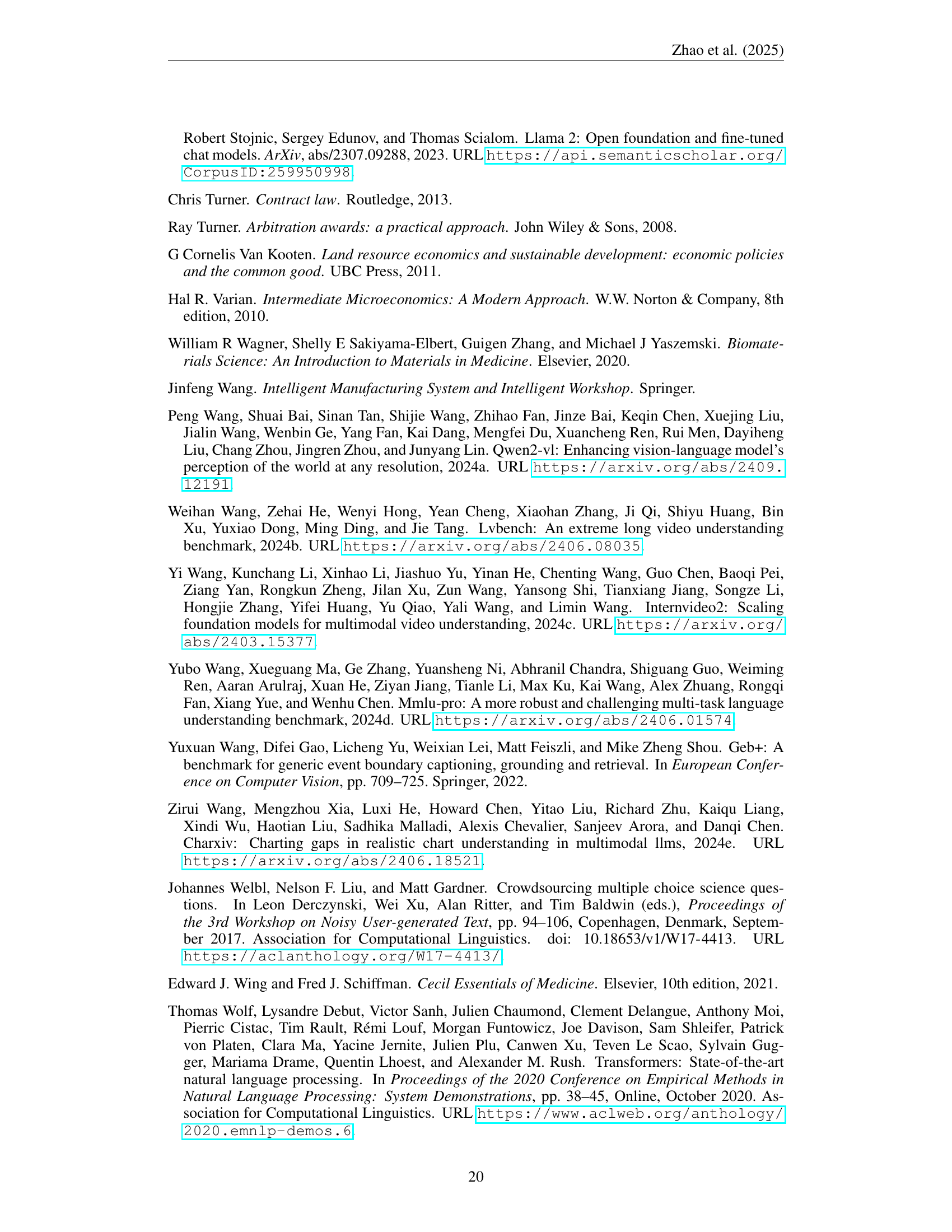

🔼 Figure 4 presents a bar chart comparing the performance of various multimodal foundation models on the MMVU validation set using both Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting and direct answering. For each model, two bars are displayed: one representing accuracy when using CoT and another showing accuracy without CoT. This visualization allows for a direct comparison of how much the use of CoT improves model performance for each model. The models are ordered by their overall performance on the validation set. More detailed results are available in section C.1 of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of model performance between CoT and direct answering on the validation set. The full results are provided in §C.1.

🔼 Figure 5 presents two examples highlighting common errors made by multimodal foundation models when processing video data for complex reasoning tasks. The left panel illustrates a ‘visual perception error’ where the model incorrectly interprets the traversal order of a binary tree in a video, demonstrating a failure to accurately perceive visual information. The right panel showcases a ‘misuse or lack of domain knowledge in reasoning’ error. Here, the model incorrectly associates the presence of bats (shown in a video about a virus) with poor sanitation, leading to a false conclusion about the type of virus. These examples demonstrate the challenges models face in correctly integrating visual and domain-specific knowledge for accurate answers.

read the caption

Figure 5: Illustrations of visual perception error and misuse or lack domain knowledge in reasoning.

🔼 This figure shows the first step in the MMVU benchmark’s annotation process. Annotators must provide a YouTube video URL and select a question type (multiple choice or open-ended). The system then automatically checks if the video has a Creative Commons license using the YouTube Data API v3. If the license is invalid, an error message appears, and submission is blocked. Successful submission proceeds to step 2 of the annotation process.

read the caption

Figure 6: Annotation Interface - Step 1: Video Collection. In this step, annotators are required to input the YouTube video URL and select the desired question type. The backend system of the interface will automatically verify whether the provided YouTube video is under a Creative Commons license using the YouTube Data API v3. If the video does not meet this requirement, as shown in the figure, a warning message will be displayed, and the submission will be blocked. Once a valid example is submitted, the annotation interface will proceed to Step 2, which is illustrated in the following two figures.

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the annotation interface used in the MMVU benchmark creation process. Specifically, it depicts Step 2 of the annotation process, focusing on the creation of multiple-choice questions. The interface allows annotators to input a video’s start and end times, the question text, multiple-choice options, the correct answer, relevant domain knowledge (with links to Wikipedia pages), and the reasoning process behind the correct answer. The annotator can shuffle the options and add or remove Wikipedia links as needed. This detailed interface ensures the quality and consistency of the expert-level annotations in the MMVU benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 7: Annotation Interface - Step 2: Multiple-choice Question Annotation.

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the annotation interface used in the MMVU benchmark creation process. Specifically, it depicts Step 2 of the annotation process, where annotators are creating and annotating open-ended questions. The interface displays a video player showing a segment of a video, fields to enter start and end times of the relevant video segment, spaces to add question text, enter the open-ended answer, specify the relevant textbook and chapter, enter related domain knowledge (linking to Wikipedia pages), and detail the reasoning process used to arrive at the answer. The interface also allows annotators to add or remove Wikipedia links supporting the domain knowledge.

read the caption

Figure 8: Annotation Interface - Step 2: Open-ended Question Annotation.

🔼 This figure shows the interface used for validating annotations in the MMVU benchmark. Human validators carefully check each annotation, ensuring consistency with benchmark criteria and guidelines. If corrections are needed, detailed feedback is given to the annotator, who then revises and resubmits their work. Low-quality annotations that cannot be improved are discarded.

read the caption

Figure 9: Validation Interface. Human validators are required to thoroughly review each annotation feature to ensure alignment with benchmark construction criteria and annotation guidelines. If revisions are not feasible, detailed feedback must be provided to the original annotator, who will then revise and resubmit the annotation for a second review. Additionally, validators may discard examples deemed to be of low quality and unlikely to meet the desired criteria through revision.

🔼 This figure shows the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompt used in the MMVU benchmark for answering multiple-choice questions. The prompt guides the model to answer the question step-by-step, explaining its reasoning process clearly before providing the final answer. This approach encourages more detailed and transparent reasoning from the model, making it easier to analyze the model’s thought process and identify potential weaknesses. The prompt is adapted from the MMMU-Pro benchmark, indicating a lineage and methodological connection to prior work in evaluating multi-modal models. The use of CoT in this context is a significant aspect of how MMVU aims to assess expert-level reasoning.

read the caption

Figure 10: CoT reasoning prompt, adopted from MMMU-Pro Yue et al. (2024b), for answering multiple-choice question.

🔼 This figure shows the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompt used in the MMVU benchmark for open-ended questions. The prompt instructs the model to answer the question step-by-step, explaining its reasoning process clearly before providing the final answer. The format for the final answer is specified to ensure consistency. The prompt includes placeholders for the question and the processed video input, highlighting the multimodal nature of the task.

read the caption

Figure 11: CoT reasoning prompt for answering open-ended question.

🔼 This figure shows the prompt used in the MMVU benchmark for multiple-choice questions when the model is instructed to directly answer without providing any reasoning steps. It’s a more straightforward approach than the chain-of-thought prompting. The prompt includes the question, the multiple-choice options (A-E), and the visual information from the video. The model is instructed to simply output the letter corresponding to the correct answer, without providing any intermediate reasoning steps.

read the caption

Figure 12: Direct Answer prompt, adopted from MMMU-Pro Yue et al. (2024b), for answering multiple-choice question.

🔼 This figure shows the prompt used in the MMVU benchmark for evaluating the models’ ability to directly answer open-ended questions without generating intermediate reasoning steps. The prompt instructs the model to directly output the final answer using only the provided question and video information, without any intermediate reasoning or step-by-step explanation.

read the caption

Figure 13: Direct Answer prompt for answering open-ended question.

🔼 This figure shows the evaluation prompt used to assess the accuracy of the model’s responses to multiple-choice questions. The prompt instructs the evaluator (likely GPT-4) to extract the model’s answer, then compare it to the ground truth, and finally output a JSON object indicating whether the extracted answer is correct. This process ensures a standardized and objective evaluation of the model’s performance on multiple choice questions.

read the caption

Figure 14: Evaluation prompt used for assessing the accuracy of multi-choice QA.

🔼 This figure shows the evaluation prompt used to assess the accuracy of open-ended questions in the MMVU benchmark. The prompt instructs the evaluator (in this case, GPT-4) to extract the final answer from the model’s response and compare it to the ground truth answer. It emphasizes that a correct answer doesn’t need to be verbatim but should reflect the same technique or concept as the ground truth. The prompt also specifies the expected output format: a JSON object containing the extracted answer (as a string) and a boolean value indicating whether the answer is correct.

read the caption

Figure 15: Evaluation prompt used for assessing the accuracy of open-ended QA.

🔼 This bar chart compares the performance of various multimodal foundation models on the MMVU validation set, using both Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning and direct answering approaches. For each model, two bars represent its accuracy scores, one for CoT and one for direct answering. This allows for a visual comparison of how each model’s performance changes when using CoT prompting versus directly generating an answer. The chart helps to illustrate the effectiveness of CoT prompting in improving model performance on the MMVU benchmark. Models are ranked by their CoT accuracy score in descending order.

read the caption

Figure 16: Comparison of model performance between CoT reasoning and direct answering on the validation set.

🔼 This figure shows an example from the MMVU benchmark where the model incorrectly identifies a thermodynamic process. The model is shown the animation of an adiabatic compression. The correct answer is adiabatic compression (B), because the gas is thermally isolated and returns to its original state through compression. However, the model incorrectly identifies the process as adiabatic expansion (D). The model’s reasoning is based on a misinterpretation of the graph showing pressure versus volume, and a failure to account for the thermal isolation of the system. This illustrates the challenges of accurately assessing visual information and applying domain knowledge in video understanding.

read the caption

Figure 17: An error case of Thermodynamics.

🔼 The figure shows a model’s incorrect interpretation of a video depicting a change in a circuit’s resistance. The model hallucinates the presence of water and misinterprets the change in resistance as a change in deformation, demonstrating a visual perception error.

read the caption

Figure 18: An error case of Electromagnetism.

🔼 This figure shows an example where the model incorrectly identifies the cinematic technique used in a video. The video shows a dolly zoom, a technique that creates a visual distortion effect by simultaneously adjusting the focal length of the lens while the camera is moving. However, the model incorrectly identifies the technique as panning, where the camera simply moves horizontally. This highlights a failure in the model’s ability to accurately perceive and interpret visual motion in video.

read the caption

Figure 19: An error case of Art.

🔼 The figure shows an example where the model incorrectly identifies the algorithm shown in a video. The video depicts a selection sort algorithm, where the algorithm repeatedly finds the minimum element from the unsorted part and puts it at the beginning. However, the model mistakenly identifies the array indices as the values themselves and therefore incorrectly identifies the algorithm as a selection sort. This highlights the model’s difficulty in accurately interpreting visual information and applying domain-specific knowledge in algorithm recognition.

read the caption

Figure 20: An error case of Computer Science.

🔼 The figure shows an example where the model incorrectly identifies a resistor as an inductor in a circuit diagram. This misidentification leads to an incorrect conclusion about the type of filter implemented in the circuit. The model’s reasoning process is detailed, demonstrating its reliance on visual information and domain knowledge, but also highlighting a gap in understanding basic electrical components.

read the caption

Figure 21: An error case of Electrical Engineering.

🔼 The figure showcases a qualitative analysis case study focusing on a model’s error in the Pharmacy discipline within the MMVU benchmark. The model misinterprets the visual depiction of an embryo transfer procedure. Instead of correctly identifying the procedure as embryo transfer, the model hallucinates and describes the process as fetal development. This misidentification stems from the model’s inaccurate understanding of the visual elements presented in the video and a misuse of domain-specific knowledge.

read the caption

Figure 22: An error case of Pharmacy.

🔼 The figure shows a model’s error in identifying a sorting algorithm from a video. The video depicts a selection sort, where elements are repeatedly selected and placed in their correct sorted position. The model, however, misidentifies the algorithm as a bubble sort, demonstrating a failure to accurately perceive and reason over the visual steps of the sorting process and a misuse of domain-specific knowledge about visual representations of algorithms.

read the caption

Figure 23: An error case of Computer Science.

More on tables

| Dataset | QA Type | Data Source | College Level? | Detailed Solution | |

| Rational? | Knowledge? | ||||

| Text | |||||

| MMLU Hendrycks et al. (2021) | MC | Exam, course, textbook | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MMLU-Pro Wang et al. (2024d) | MC | Datasets Human & LLM augment | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| C-Eval Huang et al. (2023) | MC | Exam | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| SciEval Sun et al. (2024) | MC, Open | Internet, datasets LLM rewrite | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| TheoremQA Chen et al. (2023a) | MC, T/F, Open | Internet, exam Human rewrite | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| SciKnowEval Feng et al. (2024) | MC, T/F, Open | Textbooks, database, other datasets LLM rewrite | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Text + Image | |||||

| VisScience Jiang et al. (2024) | MC, Open | Internet, exam, textbook | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| EXAMS-V Das et al. (2024) | MC | Exam | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| ScienceQA Lu et al. (2022) | MC | Internet, course | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| SceMQA Liang et al. (2024) | MC, Open | Internet, exam | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| CharXiv Wang et al. (2024e) | Open | arXiv paper Human annotate | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MMSci Li et al. (2024g) | MC | Scientific paper LLM generate | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| OlympicArena Huang et al. (2024a) | MC, T/F, Open | Olympic competitions | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| MMMU Yue et al. (2024a) | MC, Open | Internet, exam, textbook | ✓ | 17.6% | ✗ |

| CMMMU Zhang et al. (2024a) | MC, T/F, Open | Internet, exam, textbook | ✓ | 2.1% | ✗ |

| MMMU-Pro Yue et al. (2024b) | MC | MMMU Human & LLM augment | ✓ | 15.4% | ✗ |

| Text + Video | |||||

| MMWorld He et al. (2024) | MC | Human experts (24%) / LLM-gen (76%) | 39.5% | ✗ | ✗ |

| \hdashline \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 (ours) | MC, Open | Human experts annotate from scratch | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

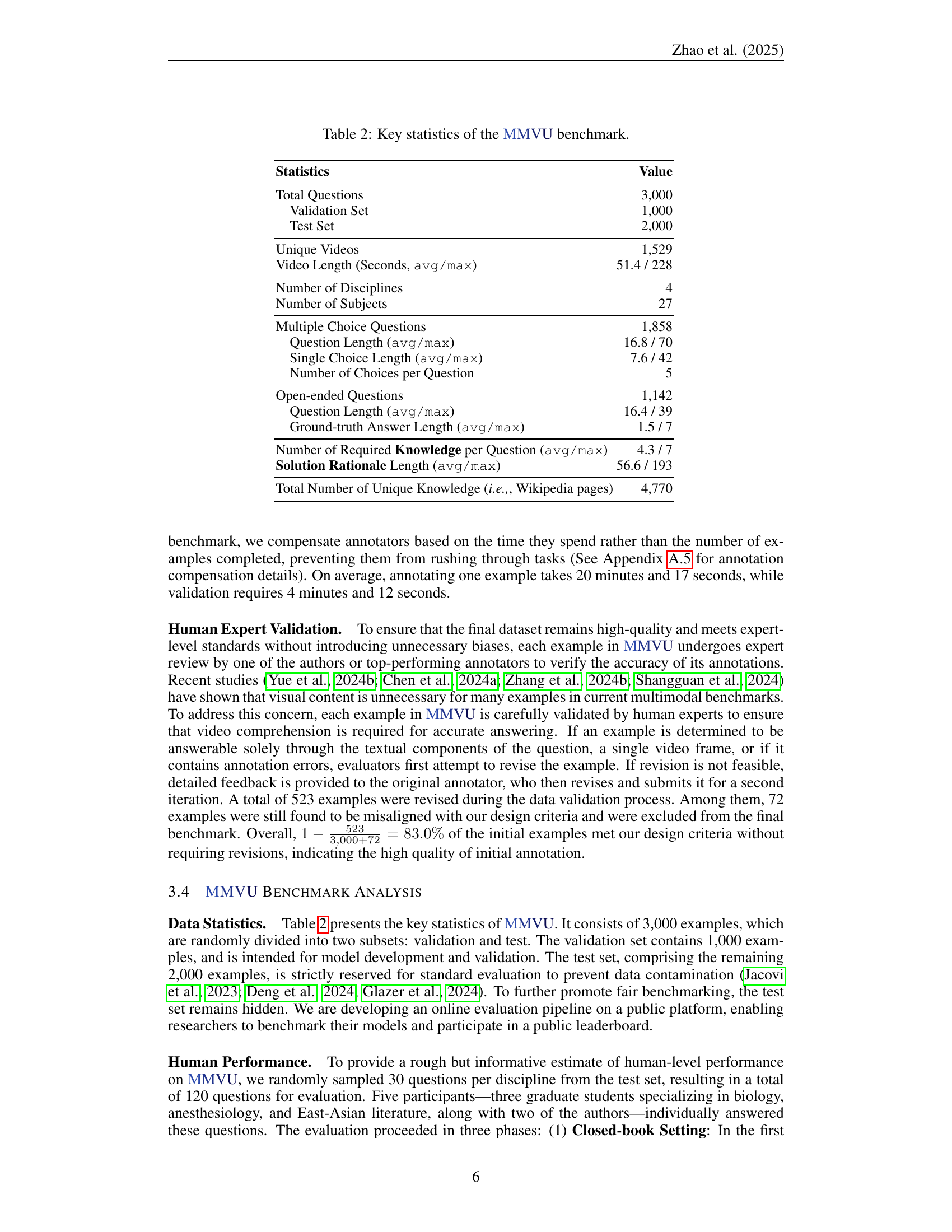

🔼 This table presents a detailed statistical overview of the MMVU benchmark dataset. It covers key aspects like the total number of questions, their distribution across training and testing sets, and the number of unique videos included. Furthermore, it provides insights into the characteristics of the questions themselves, such as the type (multiple choice vs. open-ended), length (average and maximum), and the amount of domain knowledge required for each. Video length statistics (average and maximum) are also included, providing comprehensive details about the size and scope of the MMVU benchmark. Finally, it details the number of Wikipedia pages utilized in constructing the benchmark. This comprehensive view helps to understand the scale, complexity, and characteristics of the dataset.

read the caption

Table 2: Key statistics of the \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 benchmark.

| Statistics | Value |

| Total Questions | 3,000 |

| Validation Set | 1,000 |

| Test Set | 2,000 |

| Unique Videos | 1,529 |

| Video Length (Seconds, avg/max) | 51.4 / 228 |

| Number of Disciplines | 4 |

| Number of Subjects | 27 |

| Multiple Choice Questions | 1,858 |

| Question Length (avg/max) | 16.8 / 70 |

| Single Choice Length (avg/max) | 7.6 / 42 |

| Number of Choices per Question | 5 |

| \hdashline Open-ended Questions | 1,142 |

| Question Length (avg/max) | 16.4 / 39 |

| Ground-truth Answer Length (avg/max) | 1.5 / 7 |

| Number of Required Knowledge per Question (avg/max) | 4.3 / 7 |

| Solution Rationale Length (avg/max) | 56.6 / 193 |

| Total Number of Unique Knowledge (i.e.,, Wikipedia pages) | 4,770 |

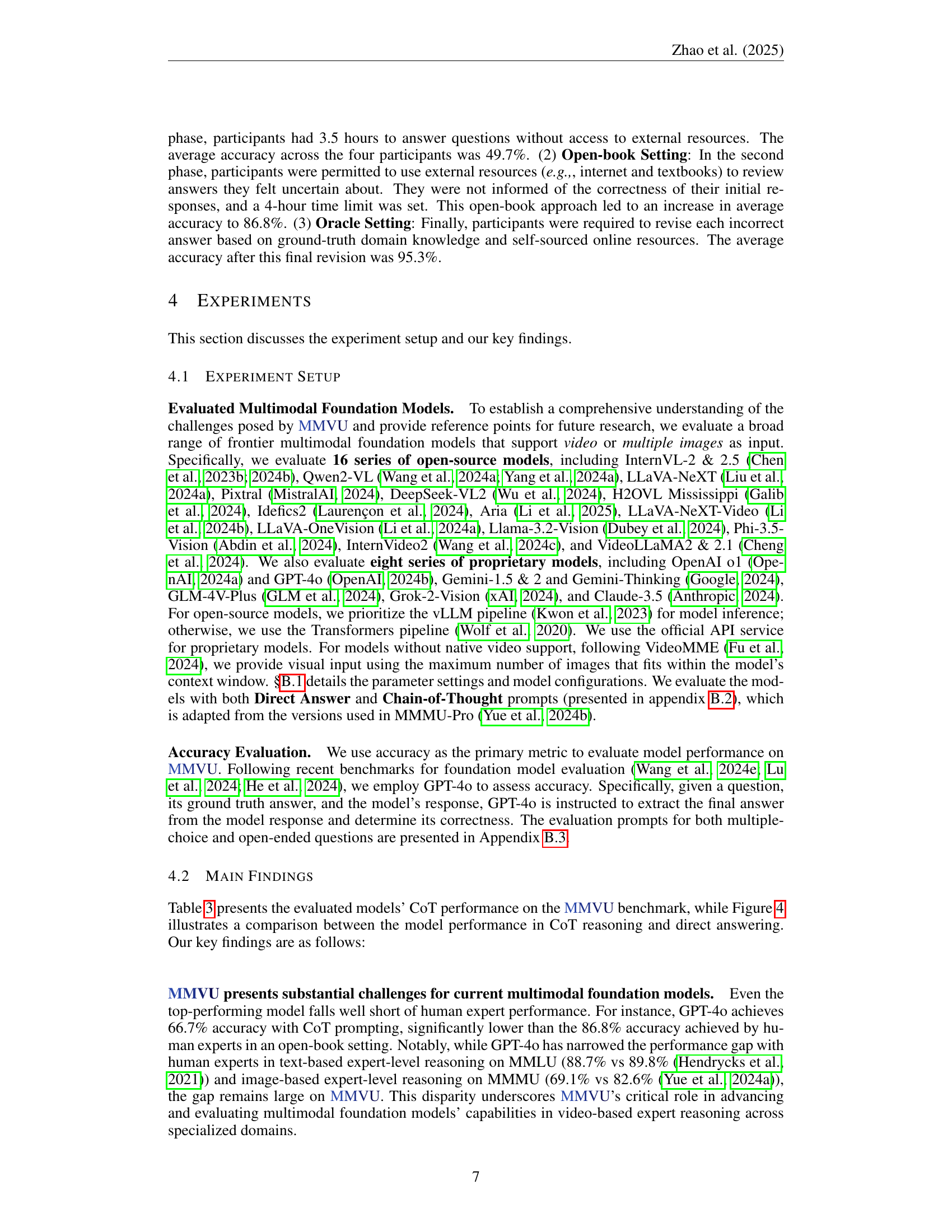

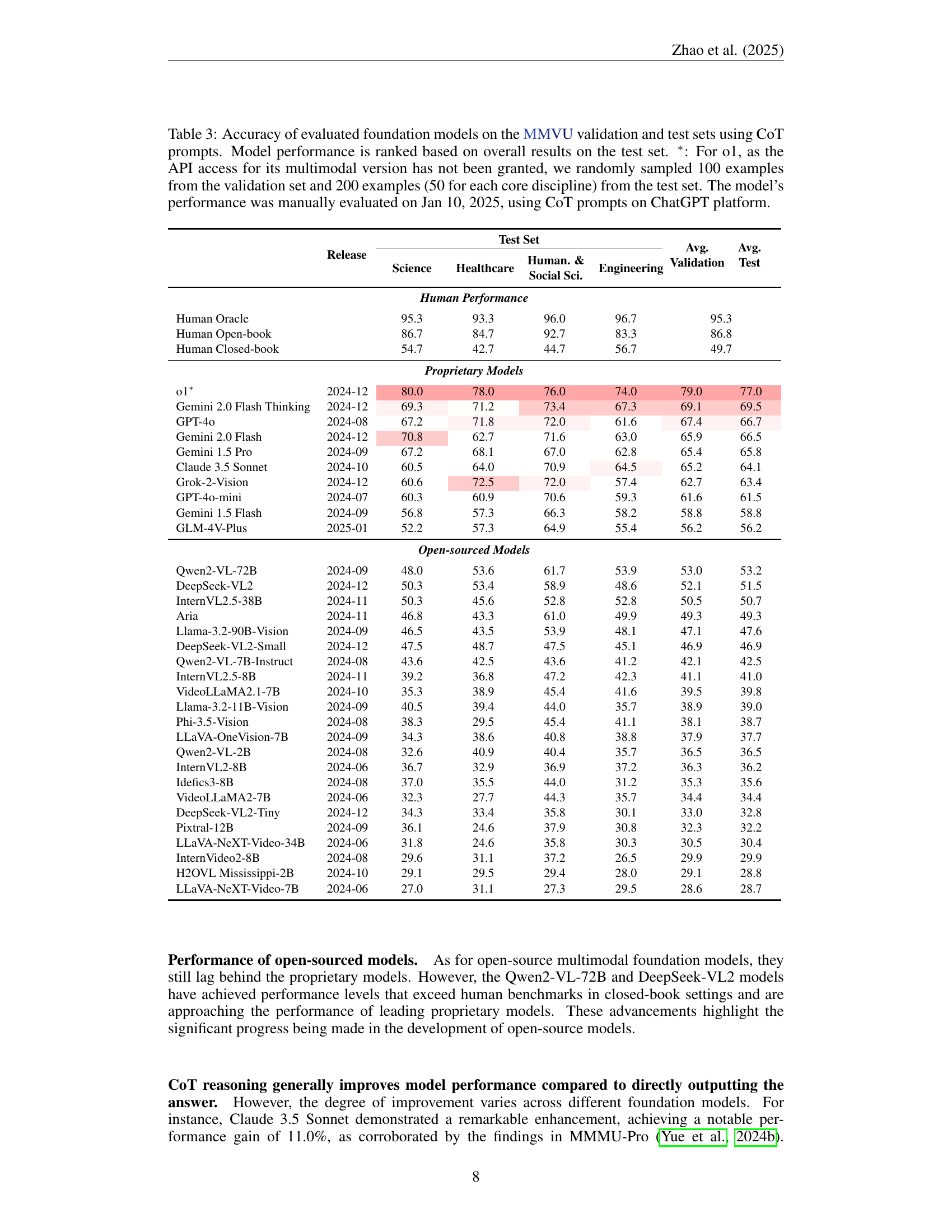

🔼 Table 3 presents the performance of various foundation models on the MMVU benchmark. The accuracy of 32 models is shown, broken down by discipline (Science, Healthcare, Humanities & Social Sciences, Engineering) and set (validation, test). The models are ranked by their overall test set accuracy. A special note is made for the o1 model, as only a subset of the validation and test sets were evaluated due to API access limitations. These evaluations for o1 were conducted manually using ChatGPT on January 10th, 2025.

read the caption

Table 3: Accuracy of evaluated foundation models on the \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 validation and test sets using CoT prompts. Model performance is ranked based on overall results on the test set. ∗: For o1, as the API access for its multimodal version has not been granted, we randomly sampled 100 examples from the validation set and 200 examples (50 for each core discipline) from the test set. The model’s performance was manually evaluated on Jan 10, 2025, using CoT prompts on ChatGPT platform.

| Release | Test Set | Avg. Validation | Avg. Test | ||||

| Science | Healthcare | Human. & Social Sci. | Engineering | ||||

| Human Performance | |||||||

| Human Oracle | 95.3 | 93.3 | 96.0 | 96.7 | 95.3 | ||

| Human Open-book | 86.7 | 84.7 | 92.7 | 83.3 | 86.8 | ||

| Human Closed-book | 54.7 | 42.7 | 44.7 | 56.7 | 49.7 | ||

| Proprietary Models | |||||||

| o1∗ | 2024-12 | 80.0 | 78.0 | 76.0 | 74.0 | 79.0 | 77.0 |

| Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking | 2024-12 | 69.3 | 71.2 | 73.4 | 67.3 | 69.1 | 69.5 |

| GPT-4o | 2024-08 | 67.2 | 71.8 | 72.0 | 61.6 | 67.4 | 66.7 |

| Gemini 2.0 Flash | 2024-12 | 70.8 | 62.7 | 71.6 | 63.0 | 65.9 | 66.5 |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro | 2024-09 | 67.2 | 68.1 | 67.0 | 62.8 | 65.4 | 65.8 |

| Claude 3.5 Sonnet | 2024-10 | 60.5 | 64.0 | 70.9 | 64.5 | 65.2 | 64.1 |

| Grok-2-Vision | 2024-12 | 60.6 | 72.5 | 72.0 | 57.4 | 62.7 | 63.4 |

| GPT-4o-mini | 2024-07 | 60.3 | 60.9 | 70.6 | 59.3 | 61.6 | 61.5 |

| Gemini 1.5 Flash | 2024-09 | 56.8 | 57.3 | 66.3 | 58.2 | 58.8 | 58.8 |

| GLM-4V-Plus | 2025-01 | 52.2 | 57.3 | 64.9 | 55.4 | 56.2 | 56.2 |

| Open-sourced Models | |||||||

| Qwen2-VL-72B | 2024-09 | 48.0 | 53.6 | 61.7 | 53.9 | 53.0 | 53.2 |

| DeepSeek-VL2 | 2024-12 | 50.3 | 53.4 | 58.9 | 48.6 | 52.1 | 51.5 |

| InternVL2.5-38B | 2024-11 | 50.3 | 45.6 | 52.8 | 52.8 | 50.5 | 50.7 |

| Aria | 2024-11 | 46.8 | 43.3 | 61.0 | 49.9 | 49.3 | 49.3 |

| Llama-3.2-90B-Vision | 2024-09 | 46.5 | 43.5 | 53.9 | 48.1 | 47.1 | 47.6 |

| DeepSeek-VL2-Small | 2024-12 | 47.5 | 48.7 | 47.5 | 45.1 | 46.9 | 46.9 |

| Qwen2-VL-7B-Instruct | 2024-08 | 43.6 | 42.5 | 43.6 | 41.2 | 42.1 | 42.5 |

| InternVL2.5-8B | 2024-11 | 39.2 | 36.8 | 47.2 | 42.3 | 41.1 | 41.0 |

| VideoLLaMA2.1-7B | 2024-10 | 35.3 | 38.9 | 45.4 | 41.6 | 39.5 | 39.8 |

| Llama-3.2-11B-Vision | 2024-09 | 40.5 | 39.4 | 44.0 | 35.7 | 38.9 | 39.0 |

| Phi-3.5-Vision | 2024-08 | 38.3 | 29.5 | 45.4 | 41.1 | 38.1 | 38.7 |

| LLaVA-OneVision-7B | 2024-09 | 34.3 | 38.6 | 40.8 | 38.8 | 37.9 | 37.7 |

| Qwen2-VL-2B | 2024-08 | 32.6 | 40.9 | 40.4 | 35.7 | 36.5 | 36.5 |

| InternVL2-8B | 2024-06 | 36.7 | 32.9 | 36.9 | 37.2 | 36.3 | 36.2 |

| Idefics3-8B | 2024-08 | 37.0 | 35.5 | 44.0 | 31.2 | 35.3 | 35.6 |

| VideoLLaMA2-7B | 2024-06 | 32.3 | 27.7 | 44.3 | 35.7 | 34.4 | 34.4 |

| DeepSeek-VL2-Tiny | 2024-12 | 34.3 | 33.4 | 35.8 | 30.1 | 33.0 | 32.8 |

| Pixtral-12B | 2024-09 | 36.1 | 24.6 | 37.9 | 30.8 | 32.3 | 32.2 |

| LLaVA-NeXT-Video-34B | 2024-06 | 31.8 | 24.6 | 35.8 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 30.4 |

| InternVideo2-8B | 2024-08 | 29.6 | 31.1 | 37.2 | 26.5 | 29.9 | 29.9 |

| H2OVL Mississippi-2B | 2024-10 | 29.1 | 29.5 | 29.4 | 28.0 | 29.1 | 28.8 |

| LLaVA-NeXT-Video-7B | 2024-06 | 27.0 | 31.1 | 27.3 | 29.5 | 28.6 | 28.7 |

🔼 Table 4 presents biographical information for the 73 experts who annotated the MMVU dataset. The table includes each annotator’s ID, year of study, major, the subject(s) they annotated, and whether they were an author or validator for the project. However, to protect the privacy of the annotators, their full names and other identifying details are not shown.

read the caption

Table 4: Biographies of 73 annotators involved in \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 construction (Author biographies are hidden to protect identity confidentiality).

| ID | Year | Major | Assigned Subject(s) | Author? | Validator? |

| 1 | 1st year Master | Biomedical Engineering | Biomedical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| Computer Science | |||||

| Electrical Engineering | |||||

| 2 | 1st year Master | Bioinformatics | Biomedical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| 3 | 1st year Master | Biological Engineering | Biomedical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| 4 | 2nd year Master | Biomedical Engineering | Biomedical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| Electronics and Communication | |||||

| 5 | 5th year PhD | Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering | Biomedical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| 6 | 2nd year Master | Architecture | Civil Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| 7 | 3rd year PhD | Civil Engineering | Civil Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mechanical Engineering | |||||

| 8 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 9 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Electrical Engineering | Computer Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| Electrical Engineering | |||||

| 10 | 2nd year Master | Electrical Engineering | Computer Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| Electronics and Communication | |||||

| 11 | 2nd year Master | Electrical Engineering | Computer Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mechanical Engineering | |||||

| 12 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Software Engineering | Computer Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| 13 | 2nd year Master | Computer Science | Computer Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| 14 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✗ |

| Electrical Engineering | |||||

| 15 | 1st year PhD | Electrical Engineering | Computer Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| Electronics and Communication | |||||

| 16 | 1st year PhD | Electrical Engineering | Electrical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| 17 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 18 | 1st year Master | Electrical Engineering | Electrical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mechanical Engineering | |||||

| 19 | 1st year PhD | Electrical Engineering | Electronics and Communication | ✗ | ✗ |

| 20 | 3rd year PhD | Food Science | Mechanics | ✗ | ✗ |

| 21 | 4th year PhD | Materials Science | Materials Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| 22 | 4th year Undergraduate | Aerospace Engineering | Materials Science | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mechanical Engineering | |||||

| 23 | 4th year Undergraduate | Mechanical Engineering | Materials Science | ✗ | ✓ |

| Mechanical Engineering | |||||

| 24 | 2nd year PhD | Mechanical Engineering | Mechanical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| 25 | 1st year PhD | Mechanical Engineering | Mechanical Engineering | ✗ | ✗ |

| 26 | 1st year Master | Medicine | Basic Medicine | ✗ | ✗ |

| Clinical Medicine | |||||

| 27 | 1st year Master | Radiology | Basic Medicine | ✗ | ✗ |

| Clinical Medicine | |||||

| 28 | 1st year Master | Dentistry | Basic Medicine | ✗ | ✗ |

| Dentistry | |||||

| 29 | 1st year PhD | Nursing | Basic Medicine | ✗ | ✗ |

| Pharmacy | |||||

| 30 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Epidemiology | Basic Medicine | ✗ | ✗ |

| Preventive Medicine | |||||

| 31 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Medicine | Clinical Medicine | ✗ | ✗ |

| 32 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 33 | 2nd year PhD | Medicine | Clinical Medicine | ✗ | ✗ |

| Pharmacy |

🔼 Table 5 presents biographical information for the 73 experts who annotated the MMVU dataset. Due to privacy concerns, only minimal identifying details are shown, such as their year of study, major, and the subjects they annotated. The table provides a snapshot of the expertise involved in creating the high-quality MMVU benchmark. This information helps readers understand the background and credentials of those who contributed to the dataset’s development and its expert-level nature.

read the caption

Table 5: Biographies of 73 annotators involved in \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80 construction (Author biographies are hidden to protect identity confidentiality).

| ID | Year | Major | Assigned Subject(s) | Author? | Validator? |

| 34 | 4th year PhD | Dentistry | Dentistry | ✗ | ✗ |

| 35 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Dentistry | Dentistry | ✗ | ✗ |

| 36 | 4th year PhD | Dentistry | Dentistry | ✗ | ✗ |

| 37 | 1st year PhD | Public Health | Pharmacy | ✗ | ✗ |

| Preventive Medicine | |||||

| 38 | 4th year Undergraduate | Pharmacy | Pharmacy | ✗ | ✗ |

| 39 | 3rd year PhD | East Asian Studies | Art | ✗ | ✗ |

| 40 | 4th year PhD | Literature | Art | ✗ | ✗ |

| History | |||||

| Literature | |||||

| 41 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✗ |

| History | |||||

| 42 | 1st year PhD | Economics | Economics | ✗ | ✗ |

| 43 | 4th year Undergraduate | Accounting | Economics | ✗ | ✗ |

| Law | |||||

| 44 | 4th year PhD | Finance | Economics | ✗ | ✗ |

| 45 | 3rd year PhD | Public Administration | Law | ✗ | ✗ |

| Management | |||||

| 46 | 1st year Master | Literature | Literature | ✗ | ✗ |

| 47 | 5th year PhD | Linguistics | Literature | ✗ | ✗ |

| 48 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Public Administration | Management | ✗ | ✗ |

| 49 | 5th year PhD | Astronomy | Astronomy | ✗ | ✗ |

| 50 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 51 | 2nd year Master | Astronomy | Astronomy | ✗ | ✗ |

| 52 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✗ |

| Geography | |||||

| 53 | 3rd year PhD | Biology | Biology | ✗ | ✗ |

| 54 | 1st year PhD | Biology | Biology | ✗ | ✗ |

| Neurobiology | |||||

| 55 | 3rd year PhD | Marine Biology | Biology | ✗ | ✗ |

| Chemistry | |||||

| 56 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✗ |

| 57 | 1st year PhD | Chemistry | Chemistry | ✗ | ✗ |

| 58 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Chemistry | Chemistry | ✗ | ✗ |

| 59 | 1st year PhD | Physics | Electromagnetism | ✗ | ✗ |

| 60 | 4th year Undergraduate | Physics | Electromagnetism | ✗ | ✗ |

| Thermodynamics | |||||

| 61 | 4th year PhD | Physics | Electromagnetism | ✗ | ✗ |

| 62 | 1st year PhD | Physics | Electromagnetism | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mechanics | |||||

| Thermodynamics | |||||

| 63 | 1st year Master | Physics | Thermodynamics | ✗ | ✗ |

| Electromagnetism | |||||

| 64 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Agricultural and Environmental Sciences | Geography | ✗ | ✗ |

| 65 | 4th year PhD | Physics | Thermodynamics | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mechanics | |||||

| Modern Physics | |||||

| 66 | 1st year PhD | Physics | Mechanics | ✗ | ✗ |

| 67 | 3rd year PhD | Physics | Mechanics | ✗ | ✗ |

| 68 | 4th year PhD | Physics | Modern Physics | ✗ | ✗ |

| 69 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Neurobiology | Neurobiology | ✗ | ✗ |

| 70 | 1st year PhD | Neurobiology | Neurobiology | ✗ | ✗ |

| 71 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 72 | 3rd year Undergraduate | Biology | Neurobiology | ✗ | ✗ |

| 73 | 1st year Master | Biology | Neurobiology | ✗ | ✗ |

🔼 Table 6 presents a list of textbooks used in the creation of the MMVU benchmark, specifically for the Science discipline. For each subject within the Science discipline (Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry, Electromagnetism, Geography, Mechanics, Modern Physics, and Neurobiology, and Thermodynamics), the table lists the specific textbook(s) and edition(s) that were consulted by expert annotators to create the questions and answers in the MMVU dataset. This detailed list provides transparency regarding the resources used to develop the benchmark and ensures the accuracy and depth of the expert-level knowledge assessed within the Science domain.

read the caption

Table 6: List of textbooks and corresponding example numbers for the Science discipline.

| Subject | Textbook |

| Astronomy | 1. Foundations of Astrophysics Ryden & Peterson (2020) |

| 2. Stellar Structure And Evolution Pols (2011) | |

| Biology | 1. Biology, 2nd Edition Clark et al. (2018a) |

| 2. Introduction to Agricultural Engineering Technology: A Problem Solving Approach, 4th Edition Field & Long (2018) | |

| 3. Introduction to Environmental Engineering, 5th Edition Davis & Cornwell (2012) | |

| 4. The Economy of Nature, 7th Edition Ricklefs (2013) | |

| 5. The Molecular Biology of the Cell, 6th Edition Alberts et al. (2014) | |

| Chemistry | 1. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry, 12th Edition Atkins et al. (2023) |

| 2. Chemistry, 2nd Edition Flowers et al. (2019) | |

| 3. Chemistry: The Central Science, 15th Edition Brown et al. (2023) | |

| 4. Organic Chemistry As A Second Language Klein (2024) | |

| 5. Organic Chemistry, 2nd Edition Clayden et al. (2012) | |

| Electromagnetism | 1. Introduction to Electrodynamics, 4th Edition Griffiths (2023) |

| 2. University Physics Volume 2 (Electromagnetism) Ling et al. (2016b) | |

| Geography | 1. Fundamentals of Geophysics, 2nd Edition Lowrie & Fichtner (2020) |

| 2. Human Geography, 12th Edition Fouberg & Murphy (2020) | |

| 3. Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation, 10th Edition Hess & McKnight (2021) | |

| Mechanics | 1. University Physics Volume 1 Ling et al. (2016a) |

| Modern Physics | 1. University Physics Volume 3 Ling et al. (2016c) |

| Neurobiology | 1. Neuroscience, 6th Edition Purves et al. (2018) |

| 2. Principles of Neural Science, 6th Edition Kandel et al. (2021) | |

| 3. Principles of Neurobiology Luo (2020) | |

| Thermodynamics | 1. An Introduction to Thermal Physics Schroeder (2020) |

| 2. University Physics Volume 2 (Thermodynamics) Ling et al. (2016b) |

🔼 This table lists the textbooks used by expert annotators to create questions for the Engineering discipline within the MMVU benchmark. Each textbook is linked to the specific subjects it covers in the benchmark. This detailed breakdown helps to understand the scope and depth of knowledge represented in the engineering-related questions in the MMVU dataset.

read the caption

Table 7: List of textbooks and corresponding example numbers for the Engineering discipline.

| Subject | Textbook |

| Biomedical Engineering | 1. Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine, 4th Edition Wagner et al. (2020) |

| 2. Biomaterials and Biopolymers Domb et al. (2023) | |

| 3. Fundamentals and Advances in Medical Biotechnology Anwar et al. (2022) | |

| 4. Introduction to Biomedical Engineering, 4th Edition Enderle & Bronzino (2017) | |

| Civil Engineering | 1. Engineering Geology and Construction Bell (2004) |

| 2. Principles of Geotechnical Engineering, 9th Edition Das (2017) | |

| 3. Structure for Architects: A Case Study in Steel, Wood, and Reinforced Concrete Design Bedi & Dabby (2019) | |

| Computer Science | 1. Algorithms, 4th Edition Sedgewick & Wayne (2011) |

| 2. Computer Organization and Design: The Hardware/Software Interface, 6th Edition Patterson & Hennessy (2022) | |

| 3. Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective, 3rd Edition Bryant & O’Hallaron (2011) | |

| 4. Deep Learning Goodfellow et al. (2016) | |

| 5. Digital Image Processing, 4th Edition Rafael & Richard (2018) | |

| 6. Introduction to Algorithms, 4th Edition Cormen et al. (2022) | |

| 7. Operating System Concepts, 10th Edition Silberschatz et al. (2018) | |

| Electrical Engineering | 1. Electrical Engineering: Principles and Applications, 7th Edition Hambley (2018) |

| Electronics and Communication | 1. CMOS Analog Circuit Design, 3rd Edition Allen & Holberg (2011) |

| 2. Introduction to Communication Systems Madhow (2014) | |

| 3. The Art of Electronics, 3rd Edition Horowitz & Hill (2015) | |

| Materials Science | 1. Composite Materials: Science and Engineering, 3rd Edition Chawla (2012) |

| 2. Convection in Porous Media, 5th Edition Nield & Bejan (2017) | |

| 3. Fiber-Reinforced Composites Materials, Manufacturing, and Design, 3rd Edition Mallick (2007) | |

| 4. Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction, 10th Edition Callister Jr & Rethwisch (2020) | |

| Mechanical Engineering | 1. Industrial Automation: An Engineering Approach |

| 2. Industrial Robotics Control: Mathematical Models, Software Architecture, and Electronics Design Frigeni (2022) | |

| 3. Intelligent Manufacturing System and Intelligent Workshop Wang | |

| 4. Machine Tool Practices, 11th Edition Kibbe et al. (2019) | |

| 5. Marks’ Standard Handbook for Mechanical Engineers, 12th Edition Avallone et al. (2018) | |

| 6. Modern Control Engineering, 5th Edition Ogata (2010) |

🔼 This table lists the textbooks used to curate questions for the Healthcare discipline within the MMVU benchmark. For each subject area within Healthcare (Basic Medicine, Clinical Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Preventive Medicine), it indicates the specific textbook(s) and edition(s) used as authoritative sources for generating expert-level questions related to video content. This detailed breakdown allows for a better understanding of the knowledge base underpinning the MMVU benchmark’s Healthcare questions.

read the caption

Table 8: List of textbooks and corresponding example numbers for the Healthcare discipline.

| Subject | Textbook |

| Basic Medicine | 1. Kuby Immunology, 8th Edition Owen et al. (2018) |

| 2. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 10th Edition Kumar et al. (2020) | |

| 3. Tissue Barriers in Disease, Injury and Regeneration Gorbunov (2022) | |

| Clinical Medicine | 1. Cecil Essentials of Medicine, 10th Edition Wing & Schiffman (2021) |

| 2. Kumar and Clark’s Clinical Medicine, 10th Edition Feather et al. (2020) | |

| Dentistry | 1. Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry, 7th Edition Yagiela et al. (2010) |

| Pharmacy | 1. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 13th Edition Brunton et al. (2017) |

| Preventive Medicine | 1. Public Health and Preventive Medicine, 15th Edition Maxcy et al. (2008) |

🔼 Table 9 presents the textbooks used for question creation within the Humanities and Social Science disciplines of the MMVU benchmark. For each subject (Art, Economics, History, Law, Literature, and Management), the table lists the specific textbooks that served as authoritative references during the question annotation process. This detailed listing provides context on the range of knowledge assessed in the Humanities and Social Science domain within the MMVU benchmark.

read the caption

Table 9: List of textbooks and corresponding example numbers for the Humanities and Social Science discipline.

| Subject | Textbook |

| Art | 1. Art Through the Ages: A Global History Volume I, 16th Edition Kleiner (2020) |

| 2. Introduction to Film Studies, 5th Edition Nelmes (2012) | |

| 3. The Filmmaker’s Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for the Digital Age, 5th Edition Ascher & Pincus (2012) | |

| Economics | 1. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach, 8th Edition Varian (2010) |

| 2. Land Resource Economics and Sustainable Development: Economic Policies and the Common Good Van Kooten (2011) | |

| 3. Macroeconomics, 9th Edition Blanchard (2024) | |

| 4. Principles of Economics, 3rd Edition Greenlaw et al. (2023) | |

| 5. Principles of Microeconomics, 9th Edition Mankiw (2020) | |

| History | 1. Archaeology: Theories Methods and Practice, 7th Edition Renfrew & Bahn (2016) |

| 2. World History Volume 1: to 1500 Kordas et al. (2022) | |

| Law | 1. Arbitration Awards: A Practical Approach Turner (2008) |

| 2. Contract Law Turner (2013) | |

| 3. The CISG: A new textbook for students and practitioners Huber & Mullis (2009) | |

| Literature | 1. An Introduction to Language, 11th Edition Fromkin et al. (2017) |

| 2. The Cambridge Introduction to the Novel MacKay (2010) | |

| Management | 1. Principles of Management Bright et al. (2019) |

🔼 Table 10 details the configurations of the 32 multimodal foundation models evaluated in the MMVU benchmark. It lists each model’s name, release date, version, whether it supports video input, the number of input frames used (if multi-image input is supported), and the inference pipeline used. For proprietary models, the ‘Source’ column provides a URL; for open-source models, it gives the Hugging Face model name. The number of input frames is chosen from 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32, based on the model’s context window limitations. ‘HF’ indicates that the model was accessed through Hugging Face.

read the caption

Table 10: Details of the multimodal foundation models evaluated in \gradientRGBMMVU53,93,20310,10,80. The “Source” column includes URLs for proprietary models and Hugging Face model names for open-source models. The “# Input Frames” column, for those models only support multi-image input, represents the default number of input frames, chosen from 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, based on the maximum value that does not exceed the model’s context window. “HF” means “Hugging Face”.

Full paper#