TL;DR#

Many believe that bigger language models are better. This paper challenges this notion by focusing on exploration, a crucial aspect of intelligence. The study uses the game Little Alchemy 2 as a benchmark, where players must combine elements to discover new ones. It finds that most large language models struggle in this open-ended task, unlike humans who can effectively balance exploration and exploitation. This is because most LLMs overemphasize short-term gains, hindering exploration.

The researchers employ various techniques like regression models and sparse autoencoders to analyze the exploration strategies of both LLMs and humans. They find that LLMs primarily rely on uncertainty-driven strategies, prioritizing the exploration of uncertain elements, while humans balance this with ’empowerment’, a tendency to make choices that expand future possibilities. The study reveals that uncertainty and choices are processed much earlier in LLMs than empowerment, which may explain their poor performance. This insightful analysis identifies critical limitations and paves the way for creating more adaptable and human-like AI systems that can effectively explore and discover.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and cognitive science as it challenges the prevalent assumption that larger language models automatically excel at exploration. It highlights the need for more nuanced approaches to model design, focusing not just on size but on fostering effective exploration strategies. The findings could significantly impact the development of more adaptable and intelligent AI systems.

Visual Insights#

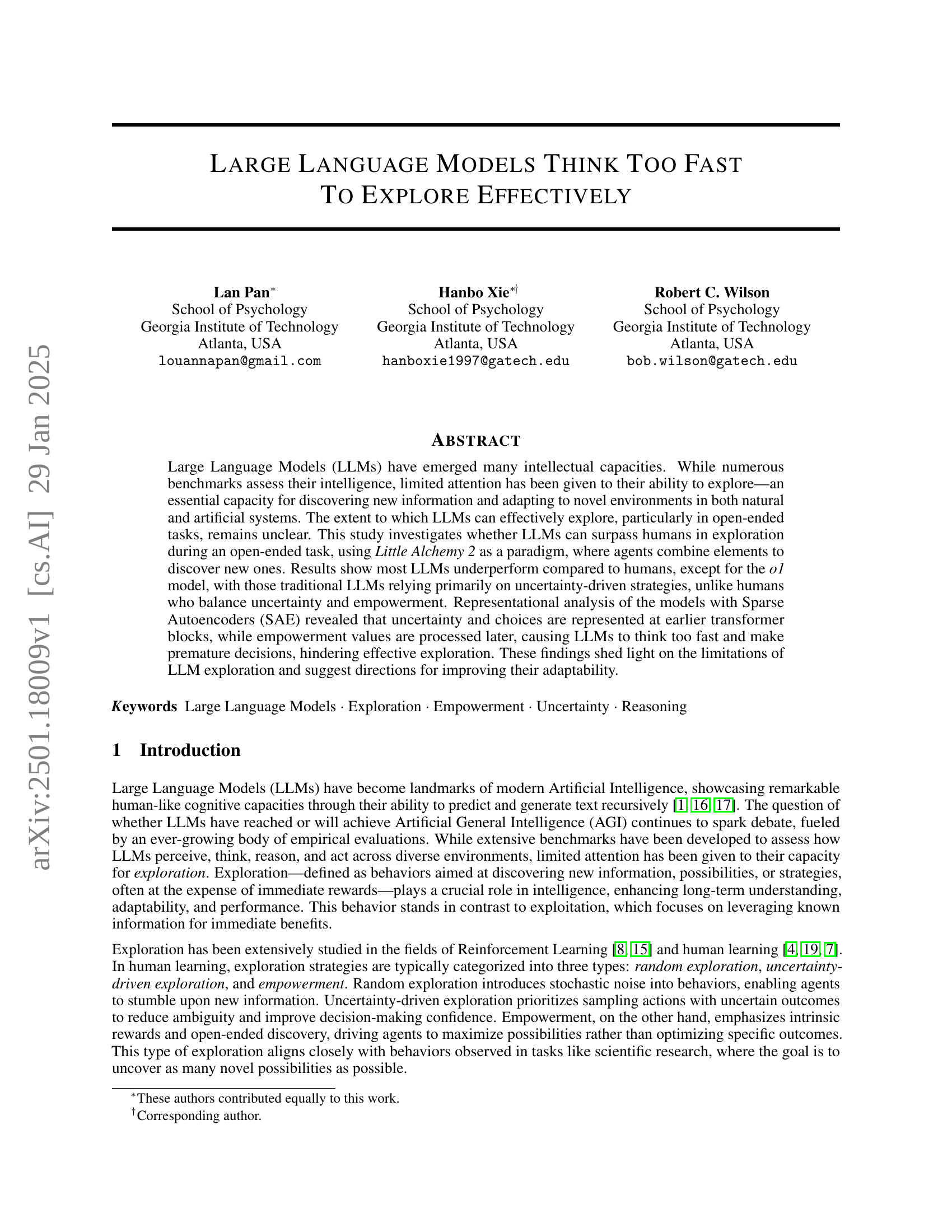

🔼 Figure 1 displays three aspects of the Little Alchemy 2 game. Panel A illustrates the process used by LLMs to play the game, showing how they select two elements for each trial, considering both the existing inventory and the history of past trials. Panel B contrasts this with the human game interface, providing a visual representation of how humans interact with the game, choosing two elements and observing the results of their combinations. This highlights the difference in decision-making processes between LLMs and humans. Finally, panel C presents a comparison of the performance of various LLMs and human players, showcasing the average number of elements discovered by each group within a set number of trials. This comparison directly demonstrates the disparity in exploration capabilities between LLMs and humans.

read the caption

Figure 1: A: LLMs Game Process. LLMs select two elements per trial based on the inventory and trial history. B: Human Game Interface. Players select two elements to discover new elements, added to the inventory. C: LLMs and Human Performance.

In-depth insights#

LLM Exploration Gap#

The hypothetical ‘LLM Exploration Gap’ highlights a critical limitation: current large language models (LLMs) underperform humans in open-ended exploratory tasks. This gap isn’t simply about finding new information, but proactively seeking out novel possibilities, a hallmark of higher-level intelligence. Existing benchmarks often focus on immediate performance, neglecting the crucial role of exploration in long-term adaptation and understanding. Uncertainty-driven exploration, while present in LLMs, is insufficient. Humans effectively balance this with empowerment, the intrinsic drive to maximize future potential. This difference in strategies suggests LLMs may process information too quickly, making premature decisions that hinder effective exploration. Addressing the LLM Exploration Gap demands new benchmarks that assess open-ended exploration capabilities, and model architectures better suited to balancing uncertainty with the pursuit of broader possibilities.

Alchemy 2 Paradigm#

The Little Alchemy 2 paradigm, employed in this research, offers a valuable framework for studying exploration in LLMs. Its open-ended nature, where agents combine elements to discover new ones, effectively mirrors real-world problem-solving scenarios that necessitate exploration. Unlike more structured benchmarks, Little Alchemy 2 requires creative combination and strategic thinking, assessing not just immediate reward maximization but long-term discovery. The game’s combinatorial space provides rich data, allowing for nuanced analysis of LLM exploration strategies including uncertainty-driven and empowerment-based approaches. By comparing LLM performance against human players in this setting, the study effectively reveals the strengths and limitations of LLMs in open-ended exploratory tasks, highlighting the need for more adaptable and intelligent AI systems.

Empowerment Deficit#

An ‘Empowerment Deficit’ in large language models (LLMs) signifies a critical limitation in their ability to explore effectively in open-ended tasks. Unlike humans who balance uncertainty and empowerment in their explorations, LLMs predominantly rely on uncertainty-driven strategies. This means they focus on reducing uncertainty by exploring possibilities with unknown outcomes rather than strategically seeking out actions that maximize long-term potential (empowerment). This deficit is linked to how LLMs process information: uncertainty and choice are processed early in the model’s architecture, leading to premature decisions. Conversely, empowerment is processed later, hindering its influence on exploration behavior. This ’thinking too fast’ is a significant constraint that impedes LLM adaptability and effectiveness in complex, open-ended environments. Addressing this deficit will require advancements in model architecture and training methodologies that foster a more balanced approach to exploration, integrating both uncertainty-driven and empowerment-driven strategies. Investigating and addressing the underlying computational mechanisms responsible for the empowerment deficit is crucial for enhancing LLM capabilities to approach human-like exploration and general intelligence.

SAE Representation#

The study leverages Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) to analyze the internal representations within LLMs during exploration tasks. SAEs reveal how LLMs process information related to uncertainty, choices, and empowerment. The findings suggest a temporal discrepancy: uncertainty and choices are processed in earlier transformer layers while empowerment is processed later. This temporal separation potentially explains why LLMs often make premature decisions, hindering effective exploration. The SAE analysis provides crucial insights into the cognitive mechanisms underlying LLM exploration limitations, offering a valuable tool for understanding and potentially improving the adaptability of these models. By highlighting the dissociation between representation and decision-making processes, the research sheds light on the challenge of creating truly intelligent and adaptive AI systems.

Fast Thinking#

The concept of “Fast Thinking” in the context of Large Language Models (LLMs) highlights a critical limitation in their exploration capabilities. LLMs process uncertainty and make choices in early transformer blocks, leading to premature decisions. This contrasts with humans who balance uncertainty and empowerment, allowing for more thoughtful exploration. The SAE analysis supports this, showing uncertainty’s representation in early layers while empowerment is processed later. This “fast thinking” hinders effective exploration because the models prioritize short-term gains (reducing uncertainty) over long-term understanding (maximizing empowerment). The temporal mismatch between uncertainty and empowerment processing is a key factor in the suboptimal exploratory behavior of LLMs. This suggests a need for architectural changes to allow for more balanced processing of these cognitive factors, enabling LLMs to think more deeply and strategically before making decisions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

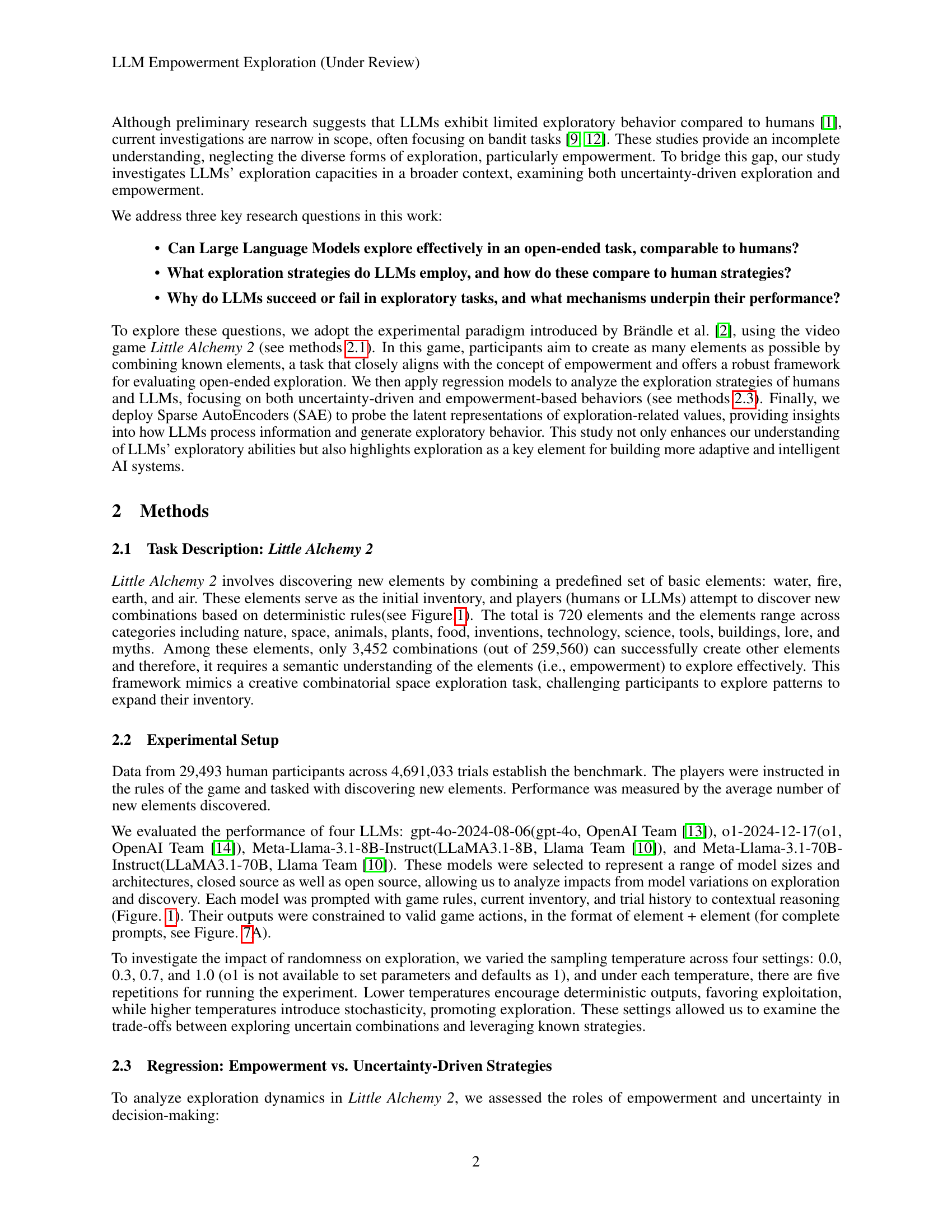

🔼 Figure 2 presents a comparative analysis of the performance of LLMs and humans in the Little Alchemy 2 game across different temperatures. Panel A displays the average inventory size (number of unique elements discovered) over 500 trials for various LLMs (gpt-4o, LLaMA3.1-8B, LLaMA3.1-70B) and humans, each tested at four different temperatures (0.0, 0.3, 0.7, and 1.0). The best performance for the LLMs is observed at temperature 1.0. Panel B shows the breakdown of trial behaviors (repeated, successful, initial combinations, etc.) at their respective best temperatures, comparing the LLMs to humans and the exceptionally performing 01 model. Panel C illustrates the LLM inventory size relative to human percentiles, further contextualizing the LLMs’ performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: A: Human and LLMs different Temperatures’ Performance.LLM and Human Performance Across Temperatures. For LLMs, we set four temperatures(0, 0.3, 0.7, 1). LLMs (gpt-4o, LLaMA3.1-8B, LLaMA3.1-70B) achieve their best performance at temperature=1temperature1\text{temperature}=1temperature = 1. B: Human and LLMs Best Temperatures’ Behaviors. According to whether the combination selected by each trial is repeated, successful, and initial, the behavior of each LLM trial is divided into 5 categories. Compare the temperature at which LLM performs best with humans and o1 behavior. C: LLM Inventory Performance Relative to Human Percentiles.

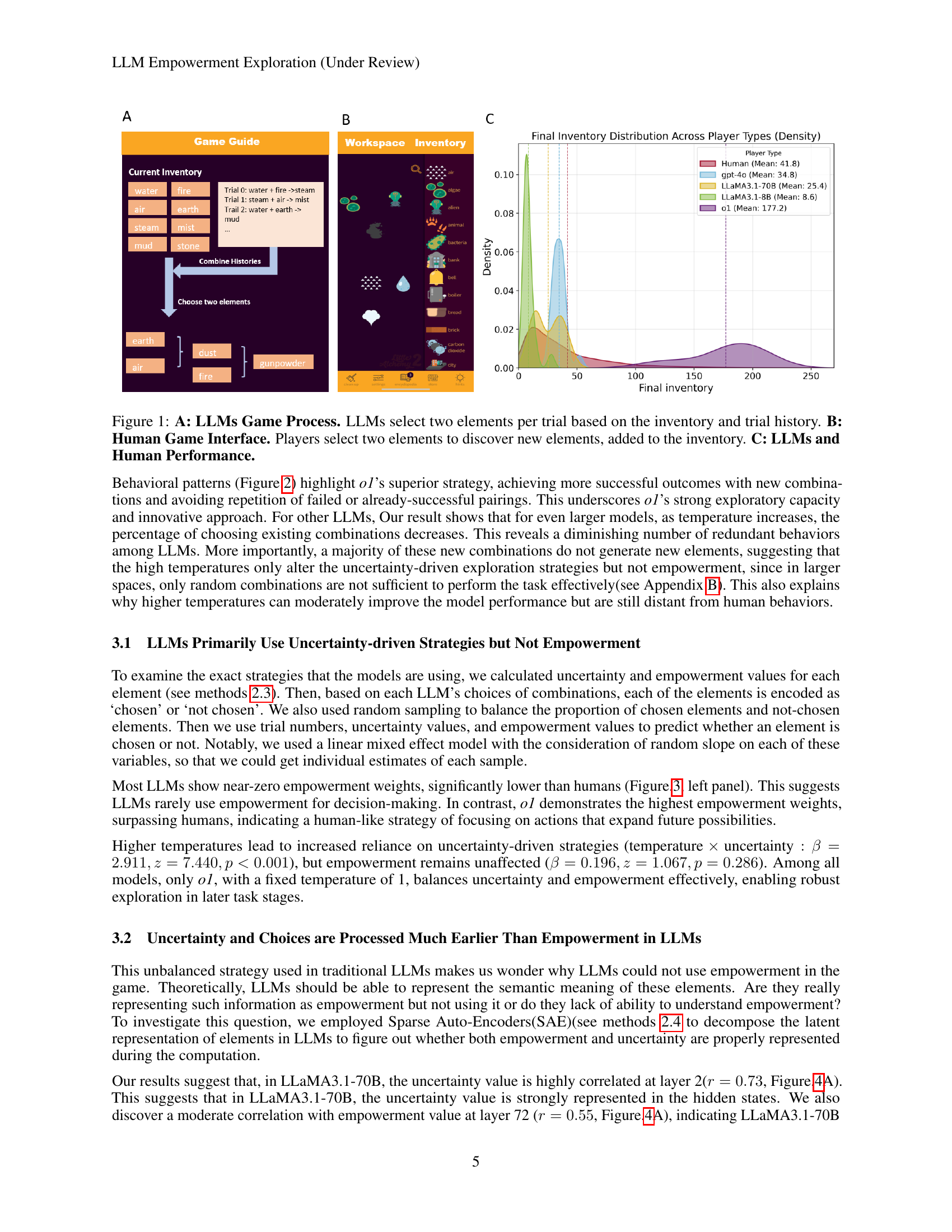

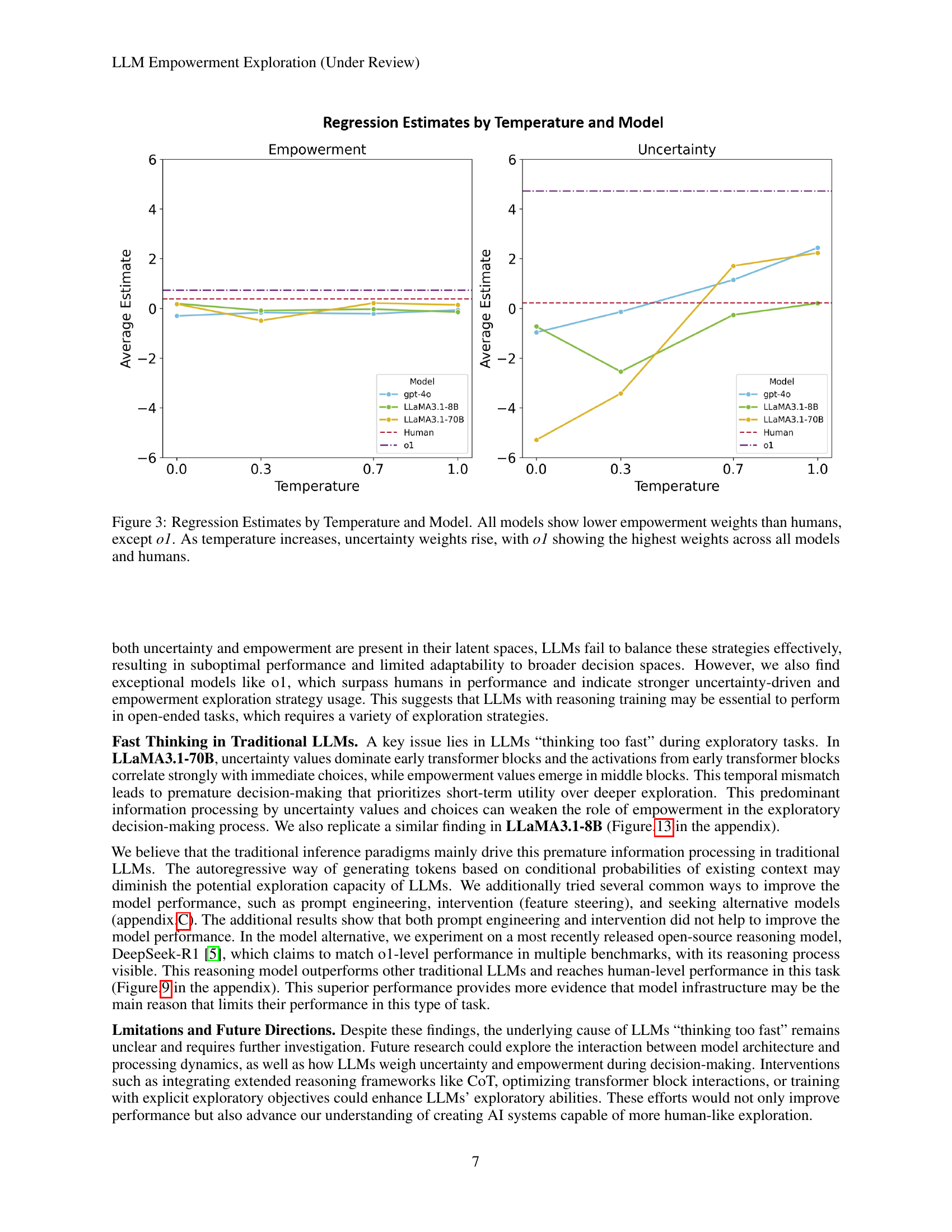

🔼 Figure 3 presents a regression analysis examining the influence of temperature and model type on empowerment and uncertainty in decision-making during an exploration task. The graph displays the average regression estimates for empowerment and uncertainty across different temperature settings (0.0, 0.3, 0.7, 1.0) for various language models (gpt-4o, LLaMA3.1-8B, LLaMA3.1-70B, and o1) and humans. The results reveal that all language models except o1 demonstrate lower empowerment weights than humans. Conversely, as the temperature increases, uncertainty weights tend to increase for all models, with model o1 exhibiting the highest uncertainty weights, mirroring the pattern observed in human participants.

read the caption

Figure 3: Regression Estimates by Temperature and Model. All models show lower empowerment weights than humans, except o1. As temperature increases, uncertainty weights rise, with o1 showing the highest weights across all models and humans.

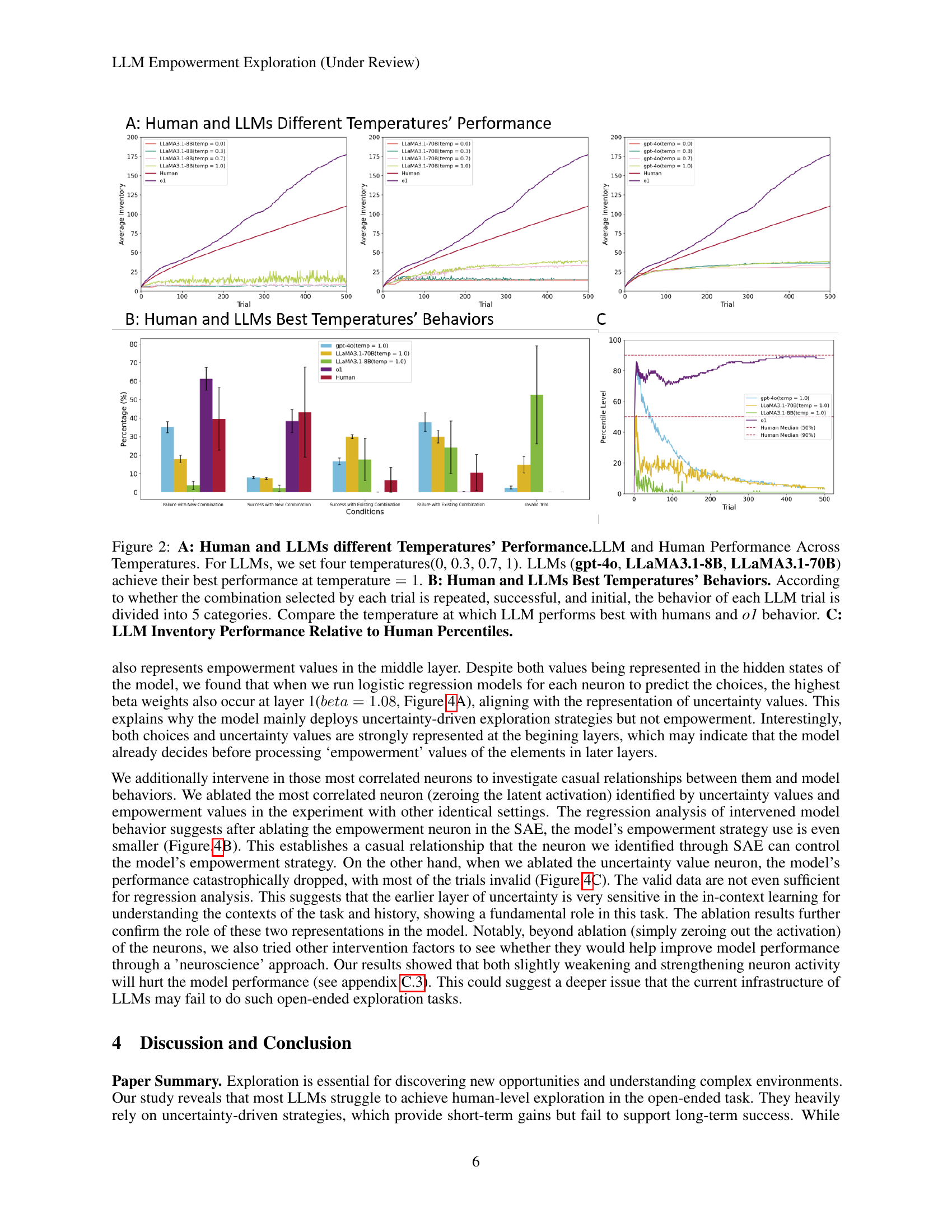

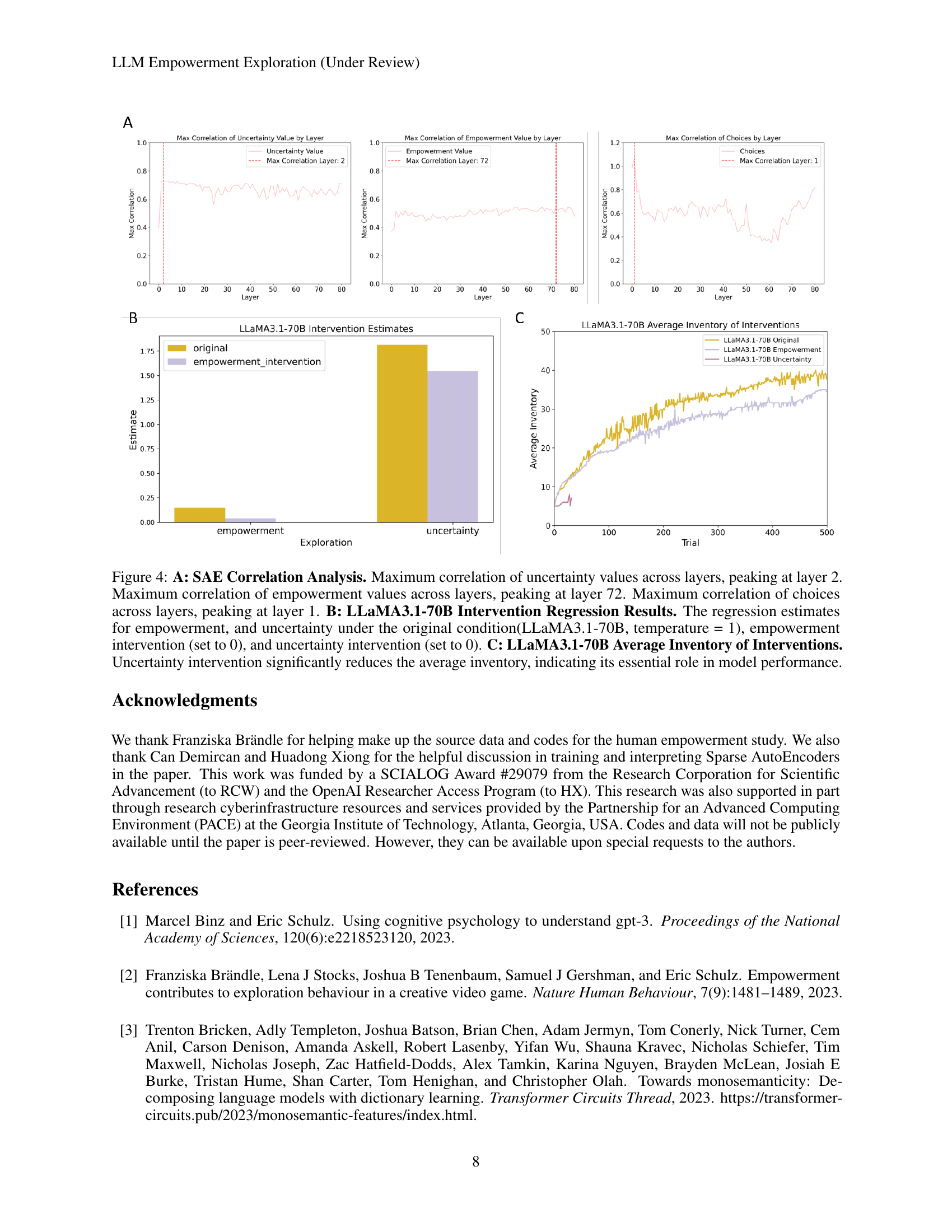

🔼 Figure 4 presents a comprehensive analysis of the exploration strategies employed by large language models (LLMs) in the Little Alchemy 2 game. Panel A reveals the correlation between cognitive variables (uncertainty, empowerment, choices) and different transformer layers within the LLM using Sparse Autoencoders (SAE). The analysis shows that uncertainty and choices are predominantly represented in early layers, whereas empowerment is processed in later layers, suggesting a temporal mismatch in information processing that hinders effective exploration. Panel B displays regression results, showing the impact of ablating either empowerment or uncertainty on the model’s performance. This highlights the crucial role of uncertainty-driven strategies in the task. Panel C demonstrates that reducing uncertainty significantly lowers the average number of elements discovered by the model, which further reinforces the importance of uncertainty in driving exploration.

read the caption

Figure 4: A: SAE Correlation Analysis. Maximum correlation of uncertainty values across layers, peaking at layer 2. Maximum correlation of empowerment values across layers, peaking at layer 72. Maximum correlation of choices across layers, peaking at layer 1. B: LLaMA3.1-70B Intervention Regression Results. The regression estimates for empowerment, and uncertainty under the original condition(LLaMA3.1-70B, temperature = 1), empowerment intervention (set to 0), and uncertainty intervention (set to 0). C: LLaMA3.1-70B Average Inventory of Interventions. Uncertainty intervention significantly reduces the average inventory, indicating its essential role in model performance.

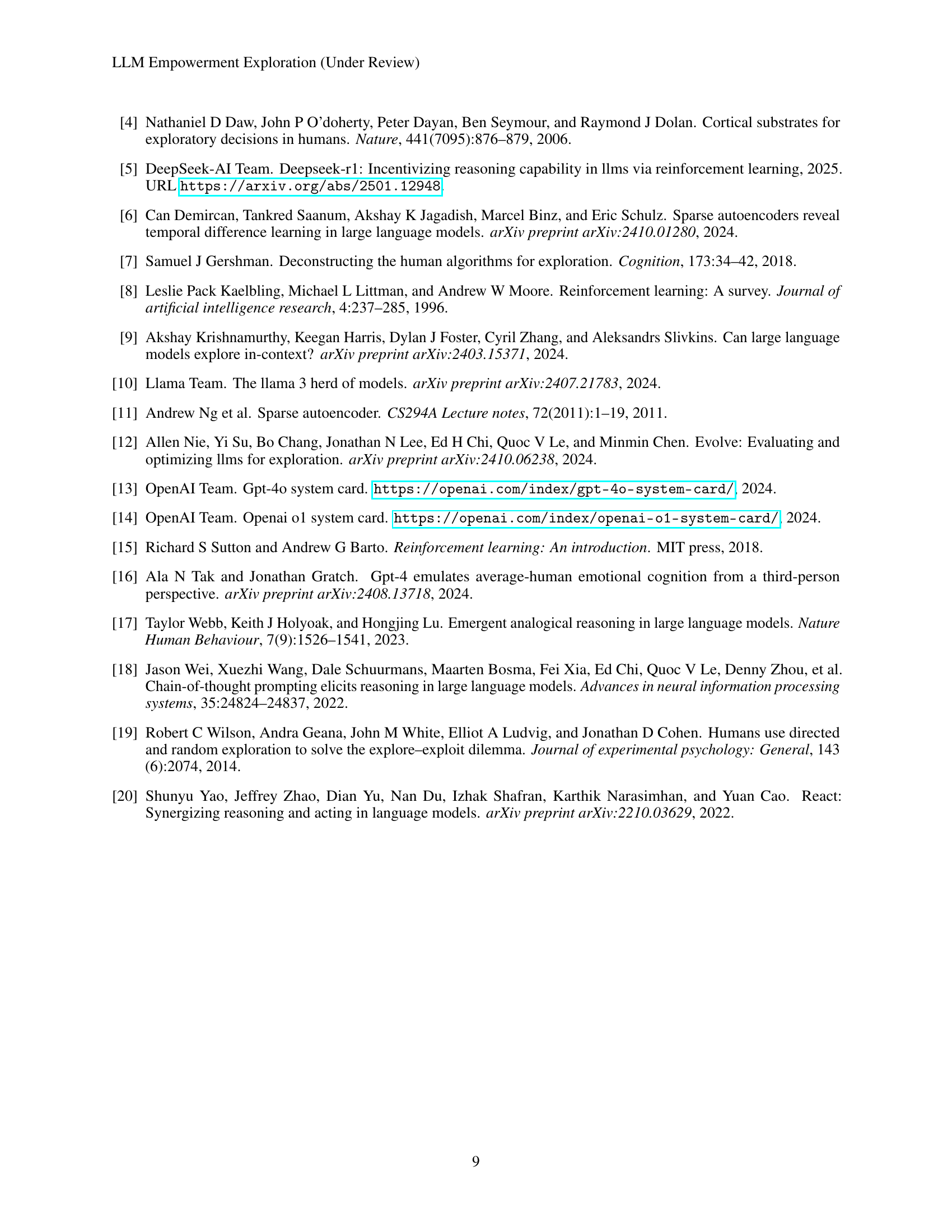

🔼 This figure illustrates the relationship between inventory size and the probability of success in the Little Alchemy 2 game. As the inventory size (number of elements discovered) increases, the probability of successfully creating new elements by combining existing ones decreases. This is because the number of possible combinations grows exponentially with the inventory size, while the number of successful combinations remains limited by the game’s design. The curve shows a rapid initial decrease in success probability as the number of elements grows, demonstrating an increasing challenge in discovering new elements as players progress in the game.

read the caption

Figure 5: Game Difficulty vs. Inventory Size. Based on the real game tree, each inventory size has a different success probability.

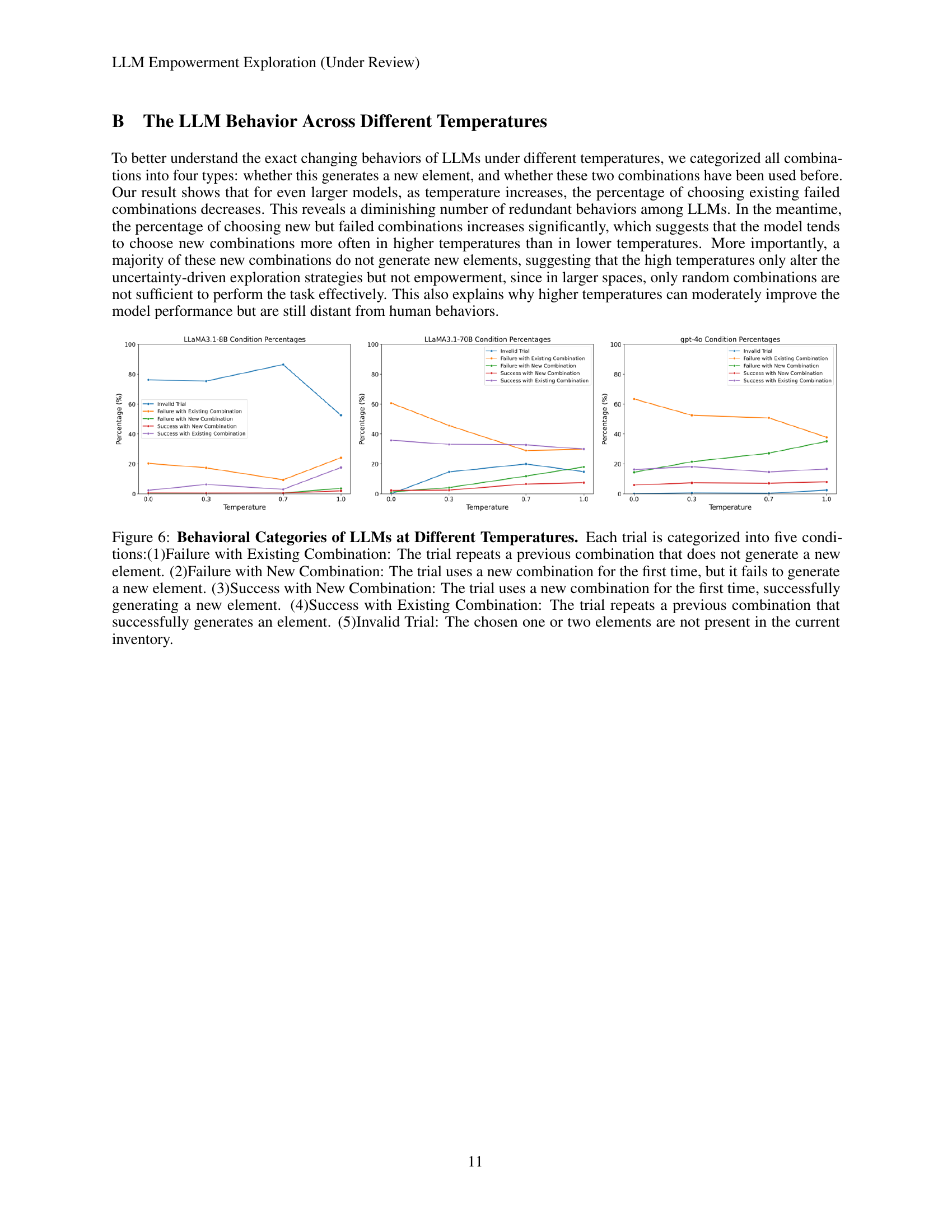

🔼 This figure analyzes the behavior of different LLMs at various temperatures by categorizing each trial into five distinct conditions. These conditions represent the combinations of elements chosen and whether those combinations are novel or repeated, and whether they successfully produce new elements or fail. The categories are: 1) Failure with an Existing Combination (a previously used, unsuccessful combination); 2) Failure with a New Combination (a new, unsuccessful combination); 3) Success with a New Combination (a new, successful combination); 4) Success with an Existing Combination (a previously used, successful combination); and 5) Invalid Trial (a combination of elements not currently in the inventory). By examining the proportion of each condition at different temperatures, the figure helps to understand how temperature affects the exploration strategies of the models, illustrating a shift from exploiting known combinations to exploring novel ones with increasing temperature.

read the caption

Figure 6: Behavioral Categories of LLMs at Different Temperatures. Each trial is categorized into five conditions:(1)Failure with Existing Combination: The trial repeats a previous combination that does not generate a new element. (2)Failure with New Combination: The trial uses a new combination for the first time, but it fails to generate a new element. (3)Success with New Combination: The trial uses a new combination for the first time, successfully generating a new element. (4)Success with Existing Combination: The trial repeats a previous combination that successfully generates an element. (5)Invalid Trial: The chosen one or two elements are not present in the current inventory.

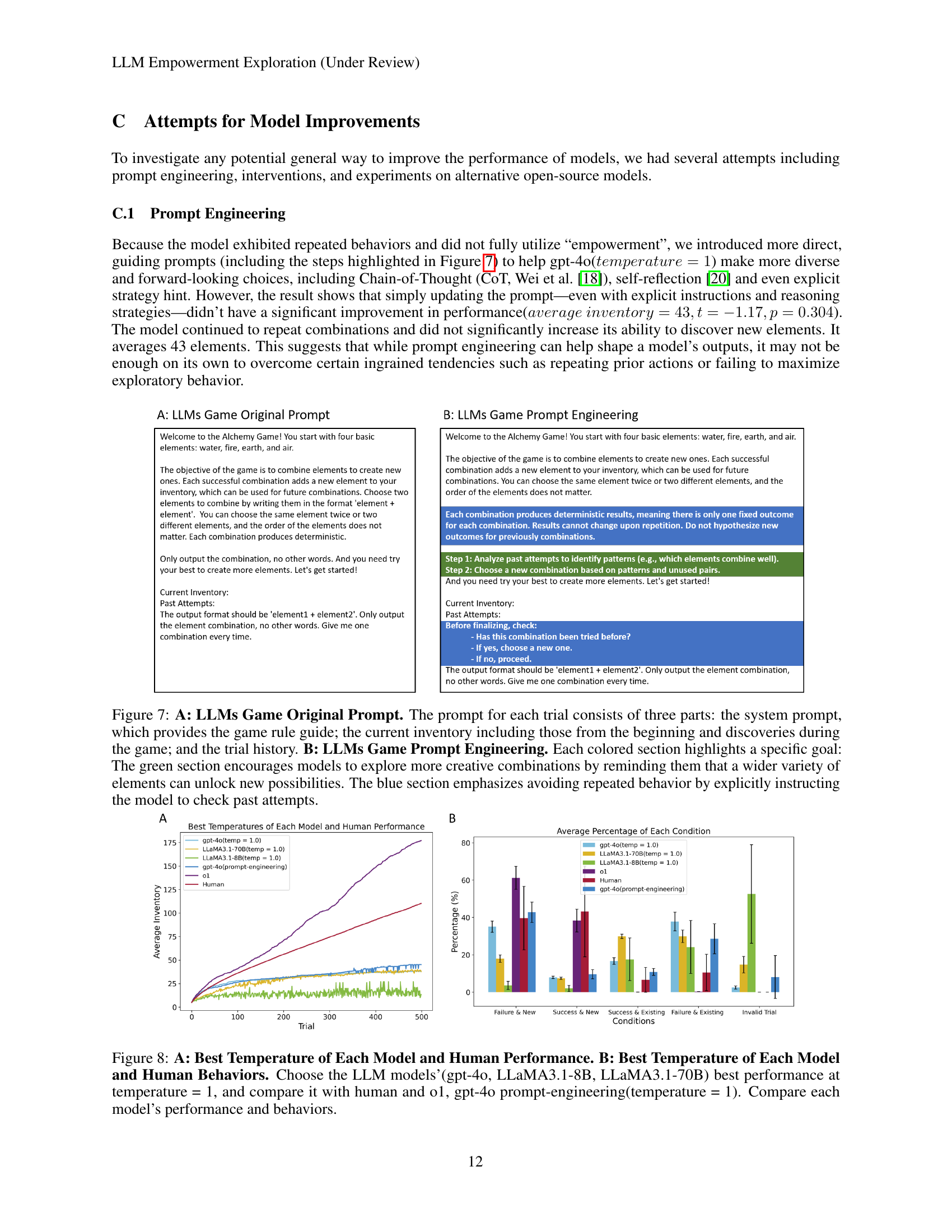

🔼 Figure 7 demonstrates two different prompt engineering approaches used to improve the performance of LLMs in the Little Alchemy 2 game. Panel A displays the original prompt structure, which includes the game rules, current inventory (both initial and discovered elements), and past trial history. Panel B introduces modifications to the original prompt. The green section encourages exploration by emphasizing that combining various elements creates new possibilities. The blue section discourages repetitive behavior by explicitly instructing the models to avoid repeated combinations from previous trials. This comparative illustration highlights how careful prompt engineering can influence LLMs’ exploratory behavior, aiming to guide them towards more creative and less repetitive strategies.

read the caption

Figure 7: A: LLMs Game Original Prompt. The prompt for each trial consists of three parts: the system prompt, which provides the game rule guide; the current inventory including those from the beginning and discoveries during the game; and the trial history. B: LLMs Game Prompt Engineering. Each colored section highlights a specific goal: The green section encourages models to explore more creative combinations by reminding them that a wider variety of elements can unlock new possibilities. The blue section emphasizes avoiding repeated behavior by explicitly instructing the model to check past attempts.

🔼 Figure 8 presents a comparative analysis of the performance and behavioral patterns of various large language models (LLMs) and humans in the Little Alchemy 2 game. Panel A displays the average inventory size (number of elements discovered) over 500 trials for each model at its optimal temperature setting (temperature = 1.0 for gpt-40, LLaMA3.1-8B, and LLaMA3.1-70B). Human performance is also included, along with results for the 01 model and gpt-40 with prompt engineering. This showcases the overall performance of each model in terms of discovering new elements. Panel B delves into the behavior of each model at its optimal temperature, categorizing trials based on whether they result in a new element, repeat previously tried combinations, or result in invalid attempts. This provides insights into the strategies and patterns employed by each model in the exploratory task. The comparison highlights the differences in exploration strategies and the relative performance of various LLMs compared to humans.

read the caption

Figure 8: A: Best Temperature of Each Model and Human Performance. B: Best Temperature of Each Model and Human Behaviors. Choose the LLM models’(gpt-4o, LLaMA3.1-8B, LLaMA3.1-70B) best performance at temperature = 1, and compare it with human and o1, gpt-4o prompt-engineering(temperature = 1). Compare each model’s performance and behaviors.

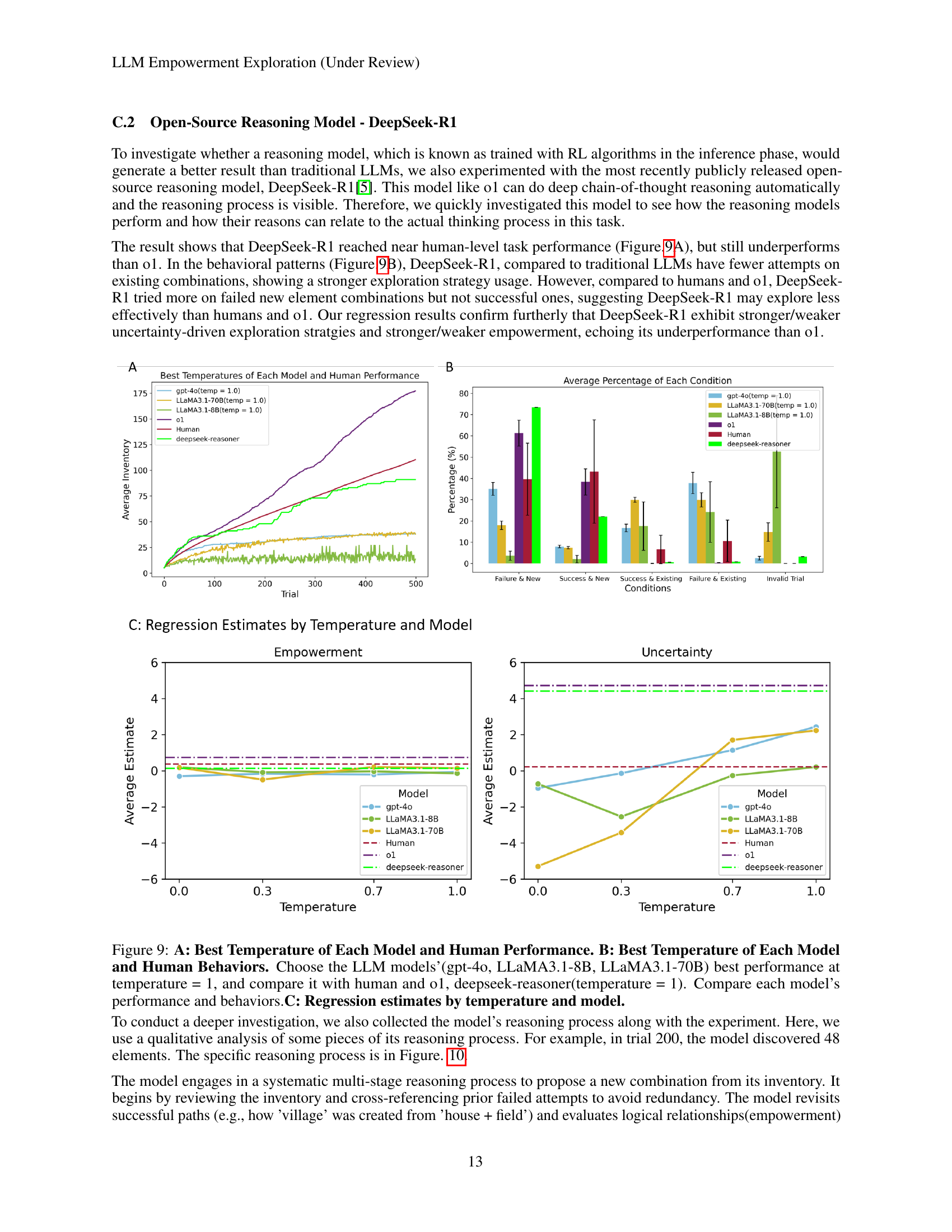

🔼 Figure 9 presents a comparative analysis of the performance and behavior of various large language models (LLMs) and humans in an open-ended exploration task. Panel A shows the average inventory size (number of unique elements discovered) over 500 trials for different models at their optimal temperature setting (temperature=1). The performance of the LLMs is compared against human performance and that of the o1 model (a strong performer). Panel B provides a breakdown of behavioral patterns by categorizing each trial based on the outcome (success/failure with new or existing combinations) for the same models, allowing for a comparison of their exploration strategies. Finally, Panel C displays regression estimates for empowerment and uncertainty across different models at varying temperatures, illustrating the role of these factors in decision-making during exploration.

read the caption

Figure 9: A: Best Temperature of Each Model and Human Performance. B: Best Temperature of Each Model and Human Behaviors. Choose the LLM models’(gpt-4o, LLaMA3.1-8B, LLaMA3.1-70B) best performance at temperature = 1, and compare it with human and o1, deepseek-reasoner(temperature = 1). Compare each model’s performance and behaviors.C: Regression estimates by temperature and model.

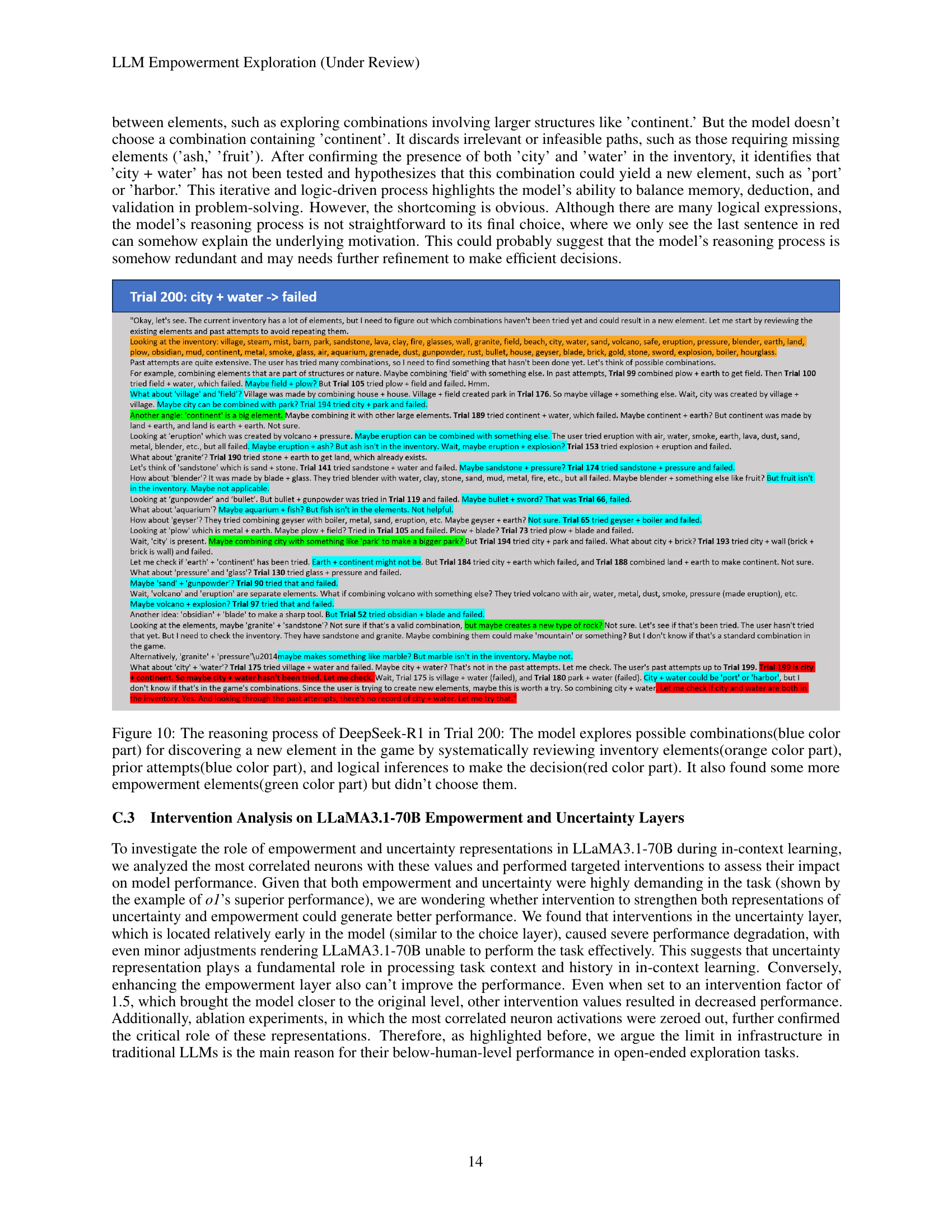

🔼 Figure 10 presents a detailed breakdown of DeepSeek-R1’s reasoning process during a specific trial (Trial 200) in the Little Alchemy 2 game. The figure visually highlights the model’s systematic approach to finding new element combinations. It starts by reviewing the available elements in its inventory (orange text), then considers past attempts (blue text) to avoid repeating unsuccessful combinations. This process involves logical deductions and inferences (red text) to evaluate the potential of different combinations. The model also identifies elements with high empowerment potential (green text), meaning combinations with those elements have a greater chance of leading to the discovery of new elements, but does not choose those combinations in this specific trial. The figure’s detailed annotations make the model’s reasoning process completely transparent and allow us to understand its decision-making in more depth.

read the caption

Figure 10: The reasoning process of DeepSeek-R1 in Trial 200: The model explores possible combinations(blue color part) for discovering a new element in the game by systematically reviewing inventory elements(orange color part), prior attempts(blue color part), and logical inferences to make the decision(red color part). It also found some more empowerment elements(green color part) but didn’t choose them.

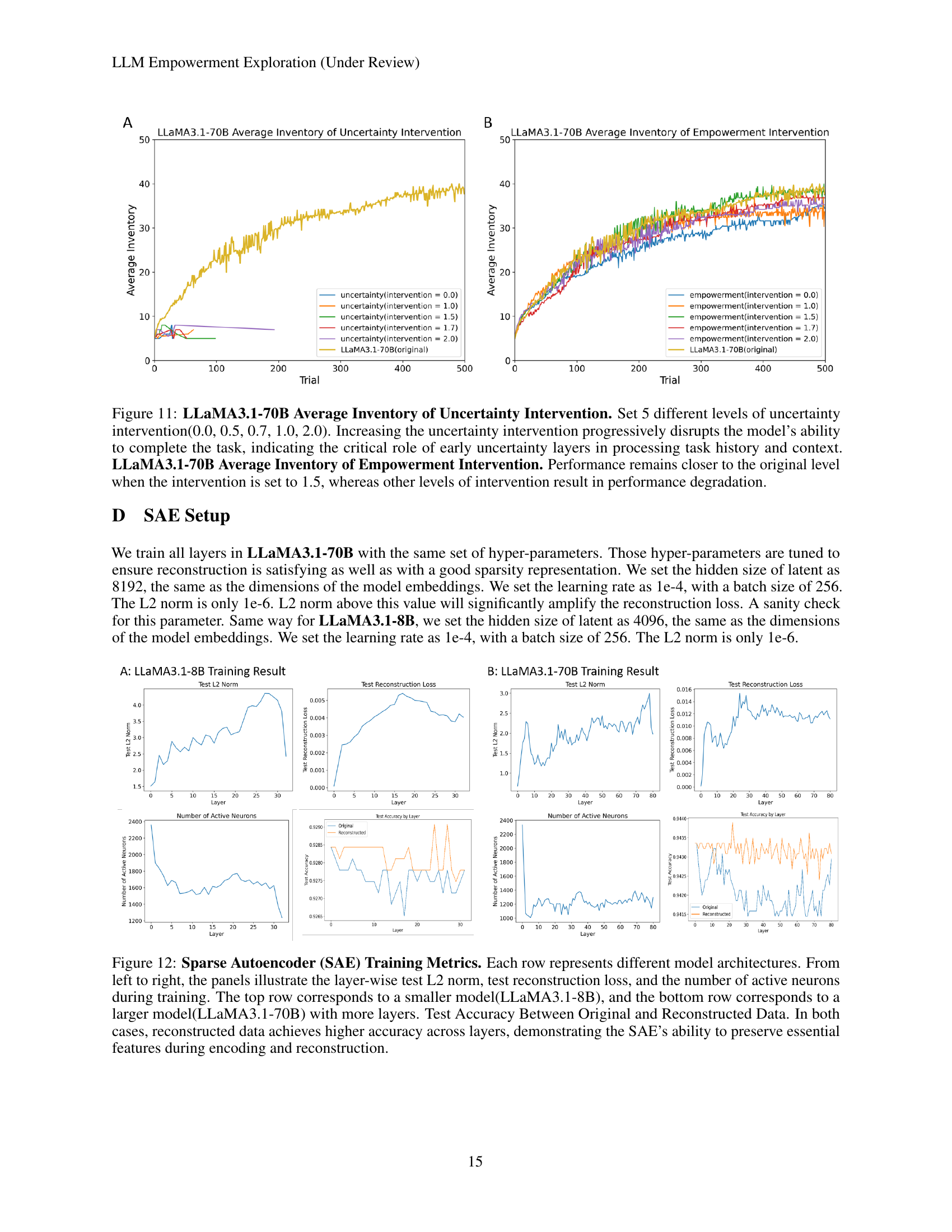

🔼 This figure displays the average inventory size achieved by the LLaMA3.1-70B language model in the Little Alchemy 2 game under varying levels of intervention targeting uncertainty and empowerment layers. The left panel shows that increasing the strength of the uncertainty intervention (from 0.0 to 2.0) progressively harms the model’s performance, dramatically decreasing the number of elements discovered. This highlights how crucial uncertainty is for the model to effectively process past trials and learn. The right panel shows that intervening on the empowerment layer has a more nuanced effect. While moderate adjustments (intervention = 1.5) maintain performance near the original level, stronger interventions significantly worsen results. This suggests that empowerment, while important, plays a more subtle role in the model’s exploration strategy than uncertainty.

read the caption

Figure 11: LLaMA3.1-70B Average Inventory of Uncertainty Intervention. Set 5 different levels of uncertainty intervention(0.0, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0, 2.0). Increasing the uncertainty intervention progressively disrupts the model’s ability to complete the task, indicating the critical role of early uncertainty layers in processing task history and context. LLaMA3.1-70B Average Inventory of Empowerment Intervention. Performance remains closer to the original level when the intervention is set to 1.5, whereas other levels of intervention result in performance degradation.

🔼 This figure displays the training metrics for Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) applied to two different sized language models: LLaMA3.1-8B (smaller model) and LLaMA3.1-70B (larger model). Each row shows results for one of the models. Within each row, three panels show: 1) Layer-wise Test L2 Norm (measuring the reconstruction error); 2) Layer-wise Test Reconstruction Loss (also measuring reconstruction error); and 3) The number of active neurons in each layer during training. A final panel in each row shows a comparison of test accuracy between the original data and the SAE’s reconstructed data. The consistent high accuracy of the reconstructed data across all layers demonstrates the effectiveness of the SAEs in preserving essential features throughout the encoding and reconstruction process.

read the caption

Figure 12: Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) Training Metrics. Each row represents different model architectures. From left to right, the panels illustrate the layer-wise test L2 norm, test reconstruction loss, and the number of active neurons during training. The top row corresponds to a smaller model(LLaMA3.1-8B), and the bottom row corresponds to a larger model(LLaMA3.1-70B) with more layers. Test Accuracy Between Original and Reconstructed Data. In both cases, reconstructed data achieves higher accuracy across layers, demonstrating the SAE’s ability to preserve essential features during encoding and reconstruction.

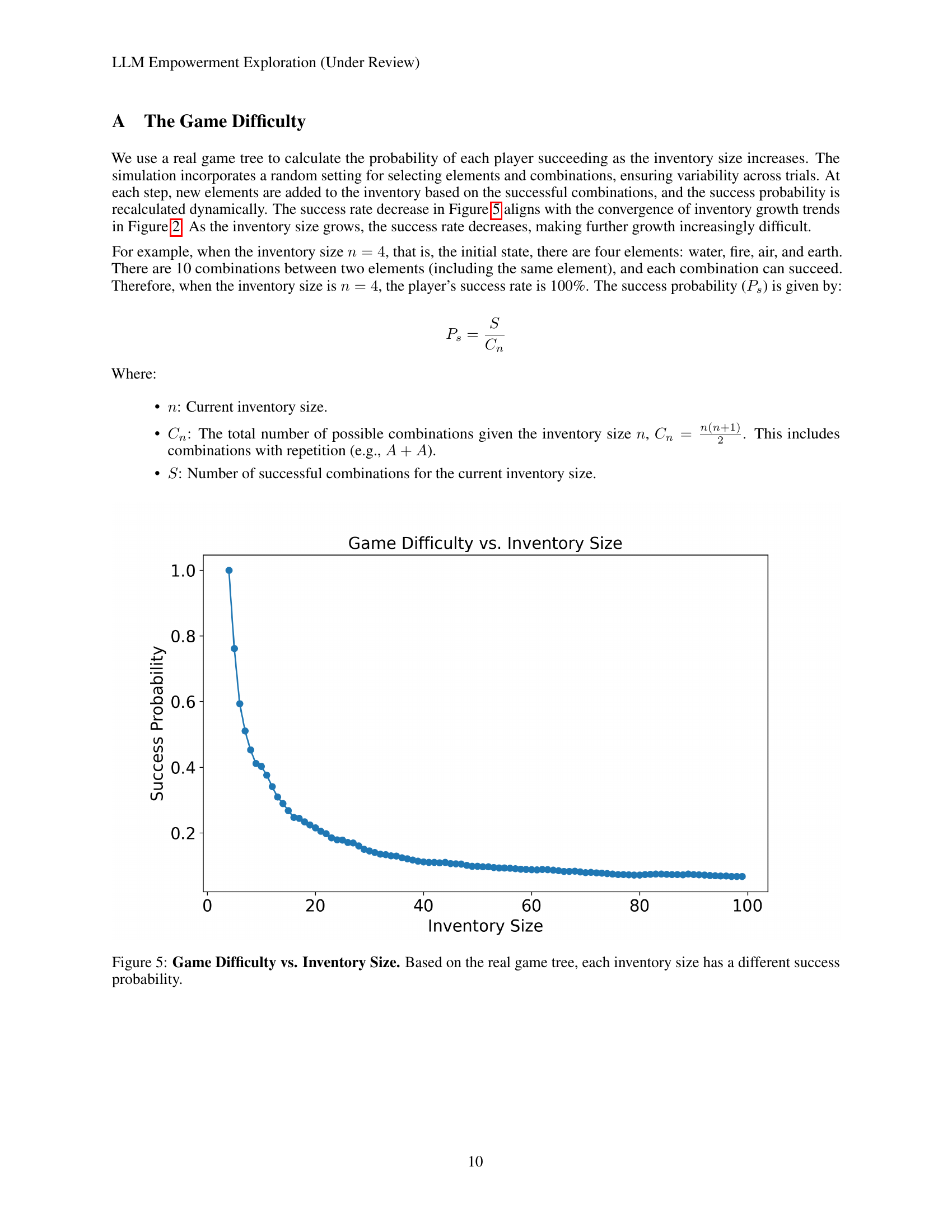

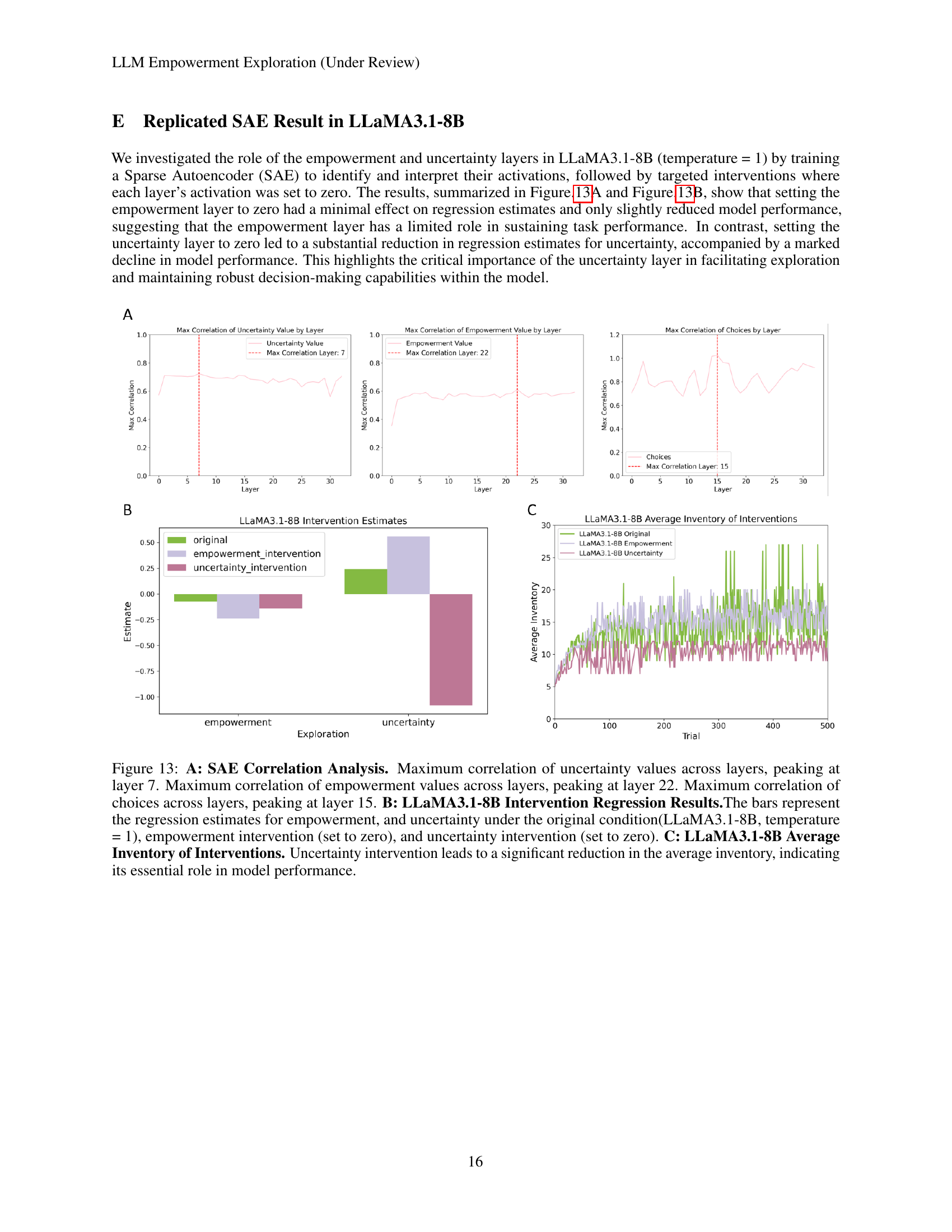

🔼 Figure 13 presents a comprehensive analysis of the LLaMA3.1-8B model’s exploration strategies using Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs). Panel A displays the maximum correlations between latent representations in SAE layers and three key variables: uncertainty, empowerment, and choices. Uncertainty shows the strongest correlation at layer 7, empowerment at layer 22, and choices at layer 15, suggesting that these factors are processed at different stages within the model’s architecture. Panel B shows regression results after interventions to the model. Setting the empowerment layer’s activation to zero has minimal impact on the model’s performance, while zeroing the uncertainty layer causes a significant drop. Panel C shows the average inventory (number of unique elements discovered) across trials. The uncertainty intervention leads to a substantially smaller average inventory. Overall, this figure demonstrates the crucial role of uncertainty in LLaMA3.1-8B’s exploration capabilities and the comparatively less significant contribution of empowerment.

read the caption

Figure 13: A: SAE Correlation Analysis. Maximum correlation of uncertainty values across layers, peaking at layer 7. Maximum correlation of empowerment values across layers, peaking at layer 22. Maximum correlation of choices across layers, peaking at layer 15. B: LLaMA3.1-8B Intervention Regression Results.The bars represent the regression estimates for empowerment, and uncertainty under the original condition(LLaMA3.1-8B, temperature = 1), empowerment intervention (set to zero), and uncertainty intervention (set to zero). C: LLaMA3.1-8B Average Inventory of Interventions. Uncertainty intervention leads to a significant reduction in the average inventory, indicating its essential role in model performance.

Full paper#