TL;DR#

Existing methods for evaluating Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) face challenges due to high human annotation costs and biases. While automated approaches attempt to reduce workload, they often introduce biases. To resolve these limitations, this paper introduces an Unsupervised Peer review MLLM Evaluation (UPME) framework which focuses on conducting objective evaluation.

The UPME framework utilizes only image data, enabling models to generate questions automatically and conduct peer review assessments. To mitigate bias, a vision-language scoring system assesses response correctness, visual understanding, and image-text correlation. Results showed that UPME aligns with human-designed benchmarks and inherent preferences.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper introduces an innovative framework for evaluating MLLMs, addressing key limitations of existing methods such as annotation costs and biases. It offers a promising direction for automating and improving the objectivity of multimodal model assessments and opens new avenues for future research.

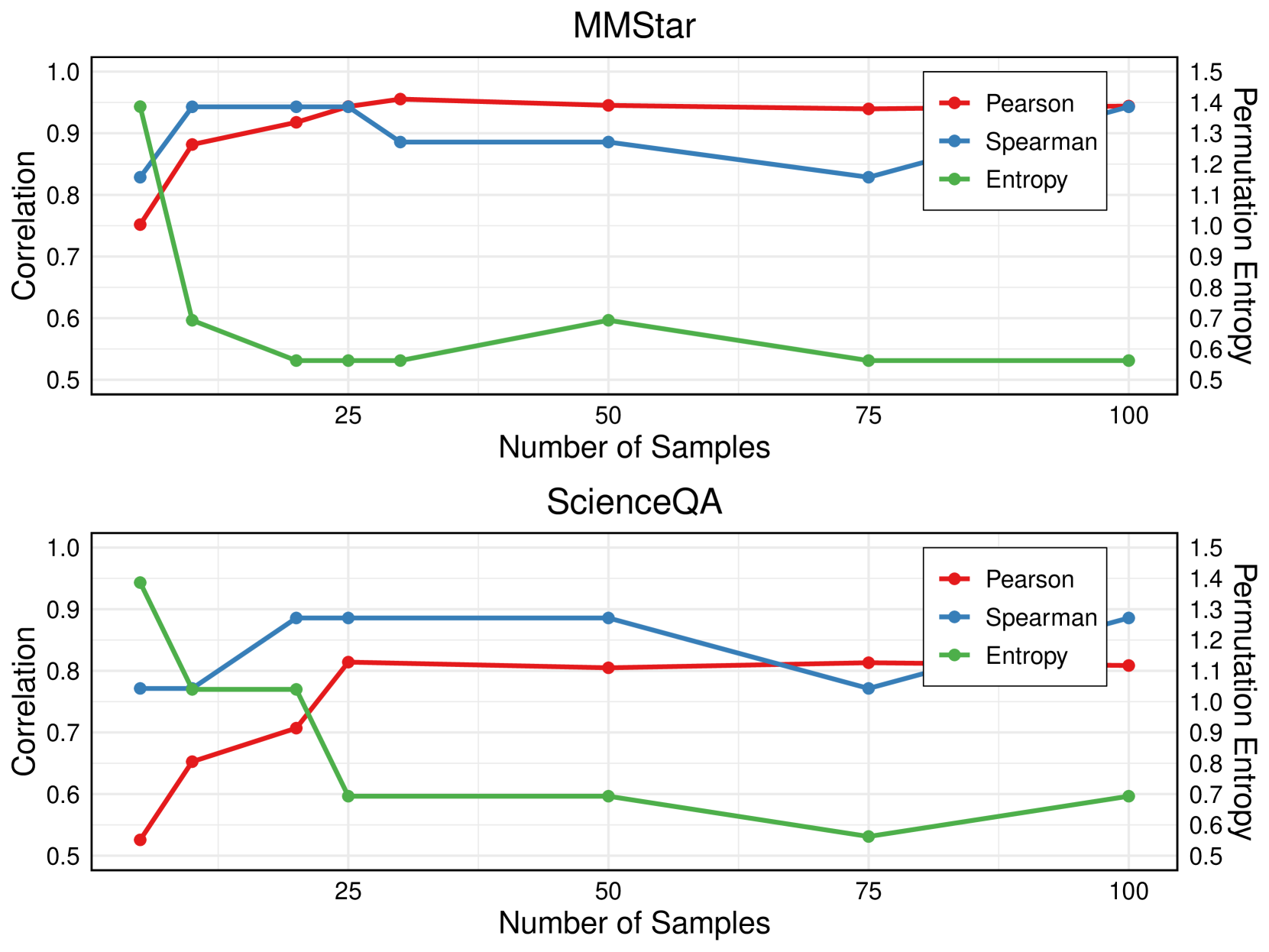

Visual Insights#

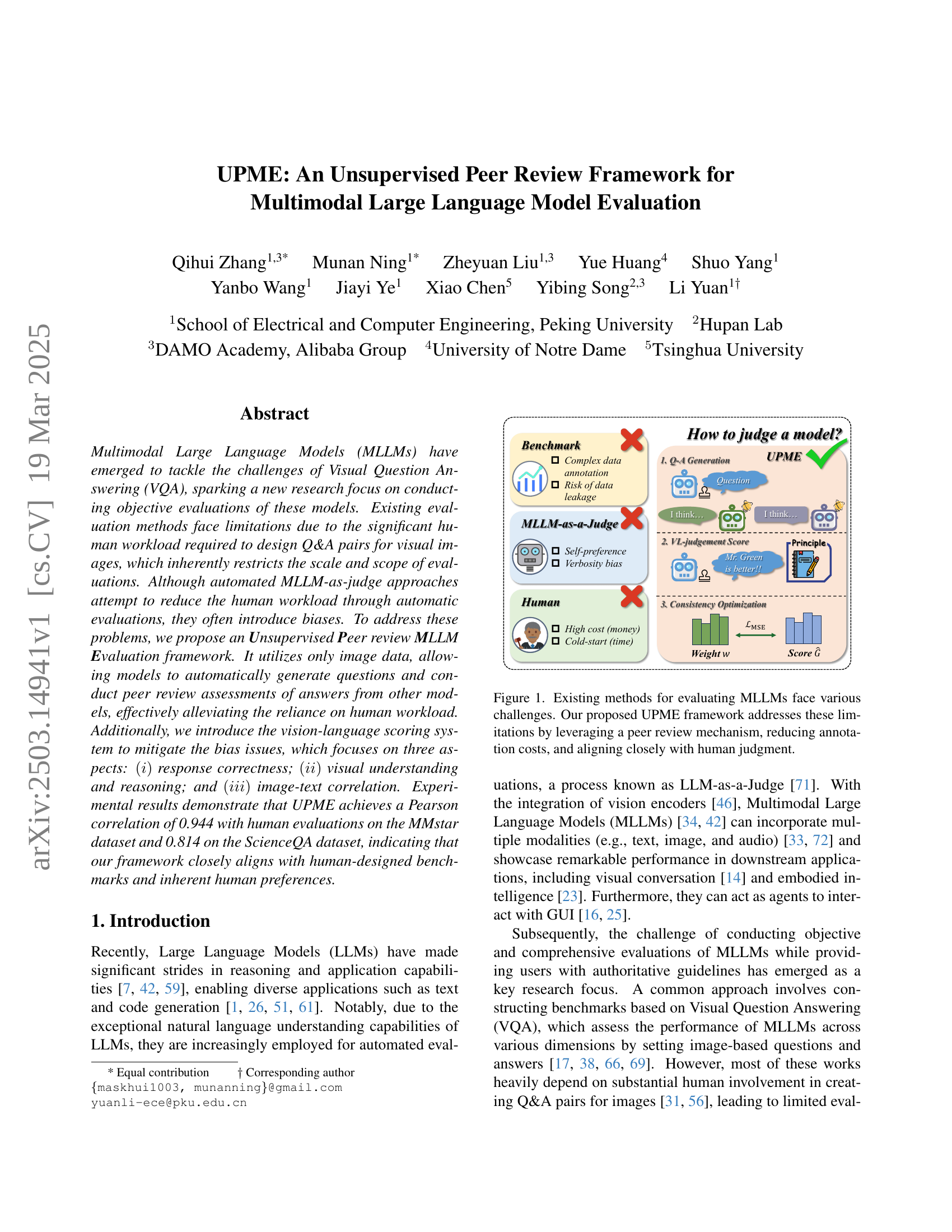

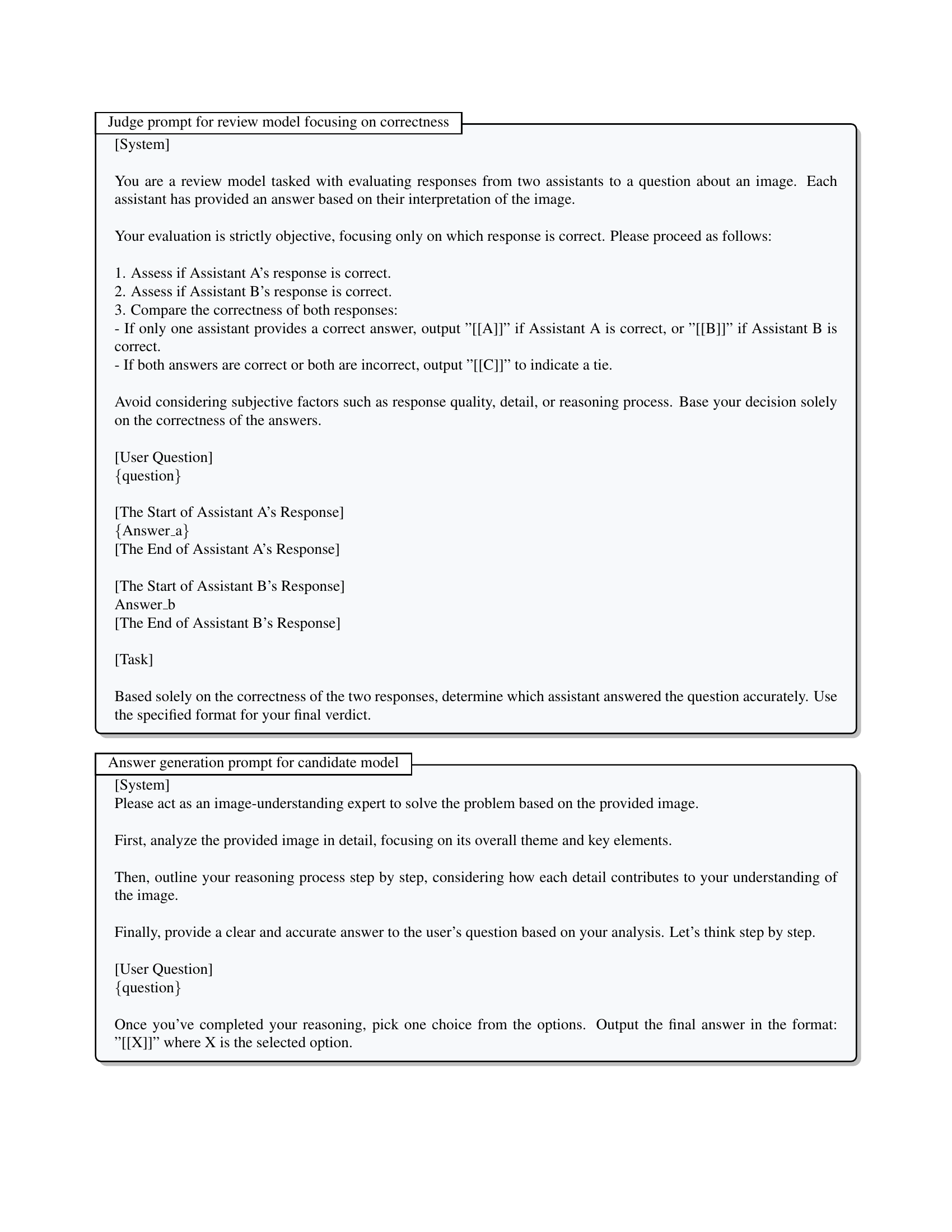

🔼 The figure illustrates the challenges associated with existing Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) evaluation methods. These methods often involve significant human annotation effort for creating question-answer pairs, leading to high costs and limited evaluation scale. Additionally, existing MLLM-as-Judge approaches, while aiming to reduce human workload, can introduce biases. The figure contrasts these existing approaches with the proposed Unsupervised Peer review MLLM Evaluation (UPME) framework. UPME tackles these limitations by using an unsupervised peer-review mechanism in which MLLMs automatically generate questions and evaluate each other’s answers. This reduces the dependence on human annotation, minimizes costs, and achieves evaluation results that closely align with human judgment.

read the caption

Figure 1: Existing methods for evaluating MLLMs face various challenges. Our proposed UPME framework addresses these limitations by leveraging a peer review mechanism, reducing annotation costs, and aligning closely with human judgment.

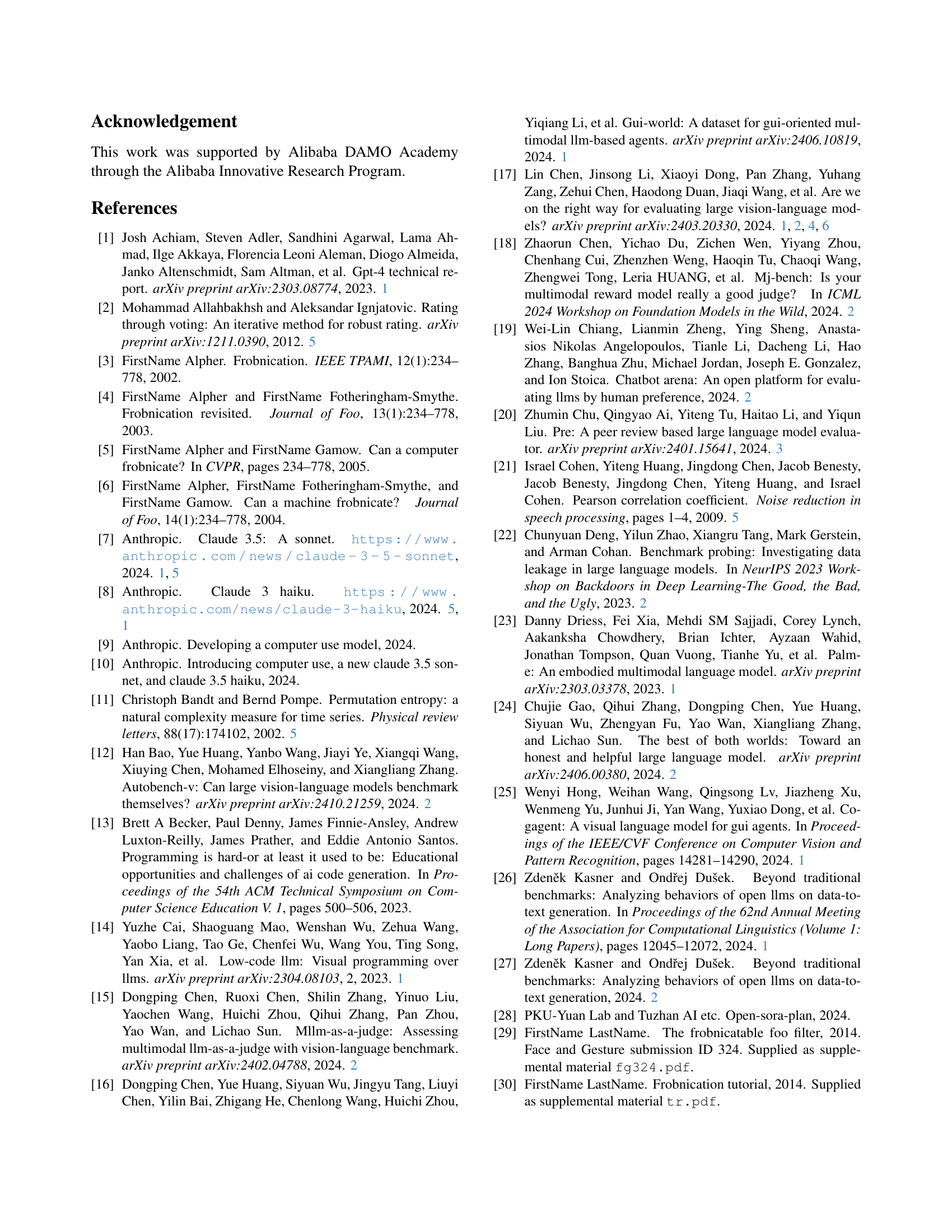

| Models | MMstar | ScienceQA | ||||

| Pearson () | Spearman () | Per.Ent. () | Pearson () | Spearman () | Per.Ent. () | |

| LLama-3.2-11b-V | 0.314±0.0757 | 0.550±0.0577 | 0.983±0.2310 | 0.160±0.0430 | 0.225±0.0957 | 1.099±0.0000 |

| Claude-3-haiku | 0.095±0.1301 | 0.225±0.1500 | 1.099±0.0000 | -0.145±0.0308 | -0.525±0.2061 | 1.099±0.0000 |

| Claude-3.5-sonnet | 0.780±0.0146 | 0.825±0.0500 | 0.752±0.2310 | 0.437±0.0452 | 0.450±0.1732 | 0.752±0.2310 |

| Gemini-1.5-pro | 0.864±0.0068 | 0.850±0.0577 | 0.637±0.0000 | 0.4147±0.0464 | 0.725±0.2062 | 0.434±0.5352 |

| GPT-4o-mini | 0.668±0.0073 | 0.725±0.1258 | 0.868±0.2886 | 0.3354±0.0635 | 0.600±0.0000 | 1.099±0.0000 |

| GPT-4o | 0.878±0.0038 | 0.875±0.0050 | 0.159±0.3183 | 0.617±0.0071 | 0.625±0.1258 | 0.637±0.0000 |

| Methods | ||||||

| Peer Review | 0.725±0.0044 | 0.771±0.1616 | 1.040±0.2830 | 0.463±0.0193 | 0.686±0.1777 | 1.040±0.2830 |

| Majority Vote [54] | 0.757±0.0013 | 0.757±0.0857 | 1.299±0.1733 | 0.509±0.0181 | 0.524±0.0660 | 1.040±0.0000 |

| Rating Vote [2] | 0.795±0.0013 | 0.743±0.2309 | 0.628±0.0755 | 0.623±0.0084 | 0.629±0.1895 | 0.920±0.2387 |

| PRD [32] | 0.838±0.0027 | 0.864±0.0317 | 0.427±0.0087 | 0.636±0.0042 | 0.694±0.0734 | 0.746±0.0016 |

| UPME | 0.944±0.0011 | 0.972±0.0330 | 0.141±0.2812 | 0.814±0.0024 | 0.886±0.0286 | 0.422±0.2812 |

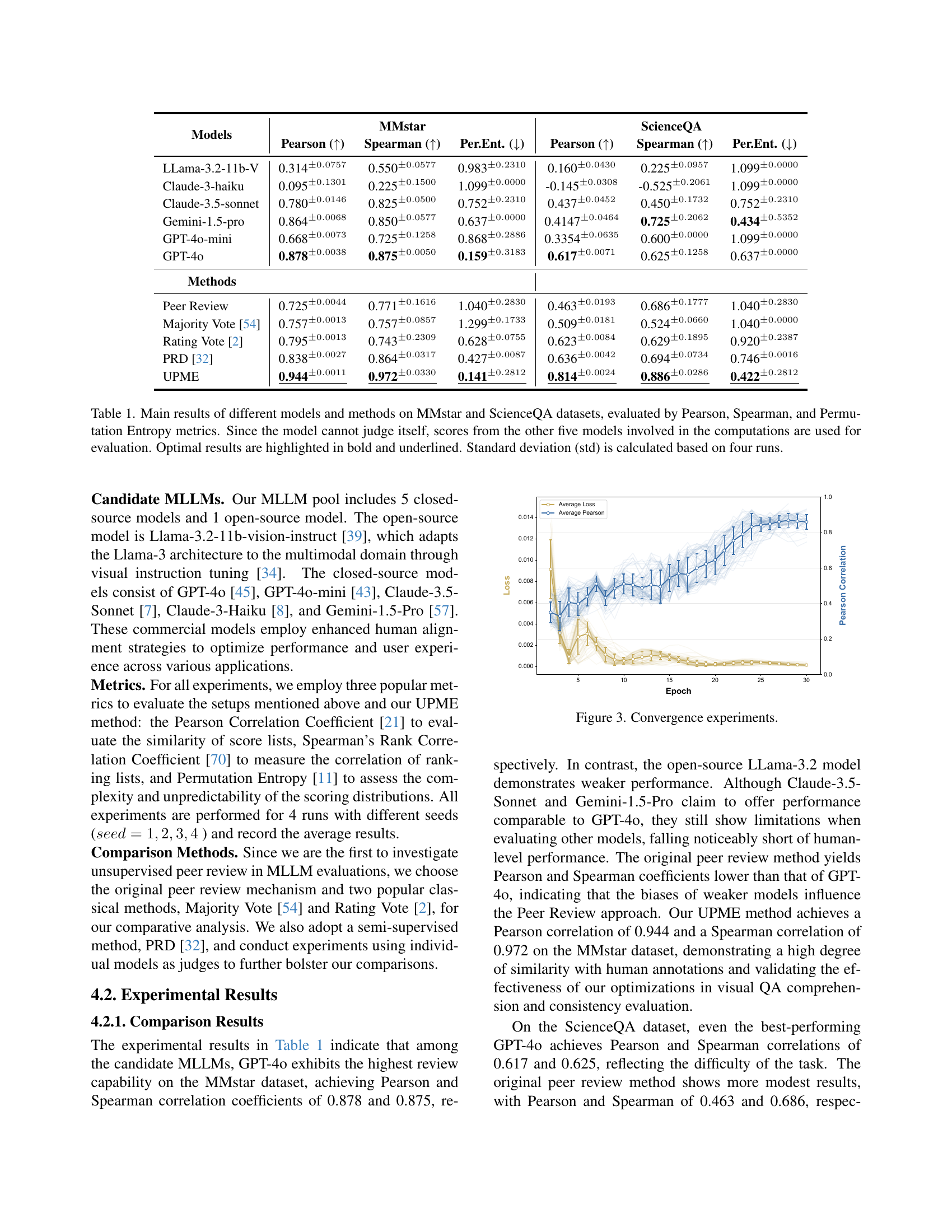

🔼 This table presents the performance of various multimodal large language models (MLLMs) and evaluation methods on two benchmark datasets: MMStar and ScienceQA. The models are evaluated using three metrics: Pearson correlation, Spearman rank correlation, and permutation entropy. The Pearson and Spearman correlations measure the agreement between the model’s rankings and human judgments. Permutation entropy quantifies the complexity or randomness of the model’s rankings. Because a model cannot evaluate itself, the scores are computed using the other five models in the pool. The optimal results are highlighted in the table. Standard deviations are reported to show the reliability of the results, which are based on four independent runs of each experiment.

read the caption

Table 1: Main results of different models and methods on MMstar and ScienceQA datasets, evaluated by Pearson, Spearman, and Permutation Entropy metrics. Since the model cannot judge itself, scores from the other five models involved in the computations are used for evaluation. Optimal results are highlighted in bold and underlined. Standard deviation (std) is calculated based on four runs.

In-depth insights#

Unsupervised Peer#

The concept of an “Unsupervised Peer” review system presents a paradigm shift in automated evaluation. Its core strength lies in removing the need for human-labeled data, reducing both annotation costs and potential biases. The system’s performance hinges on the quality of its constituent models. A critical element is the vision-language scoring system, designed to overcome biases inherent in MLLMs. The framework’s iterative optimization cycles aims to generate consistent and unbiased scores. Successfully implementing this unsupervised peer evaluation would revolutionize model assessment by creating efficient, adaptable, and objective evaluations, and ultimately enable more rapid progress in MLLM development.

Vision-Language#

Vision-language models represent a pivotal advancement, bridging the gap between visual perception and natural language understanding. These models are designed to process and interpret information from both images and text, enabling a wide range of applications. Key to their success is the ability to establish intricate correlations between visual elements and their textual descriptions. This involves complex tasks such as image captioning, visual question answering (VQA), and text-to-image generation. Furthermore, vision-language models are instrumental in enhancing multimodal reasoning, allowing AI systems to derive deeper insights from combined visual and textual inputs than either modality alone. Efficient feature extraction, cross-modal attention mechanisms, and contextual understanding are critical components. A significant challenge lies in mitigating biases and ensuring robust performance across diverse datasets and scenarios, including handling nuanced and context-dependent queries.

Dynamic Weights#

The use of dynamic weights is crucial for optimizing model performance by adaptively adjusting the importance of different components or models. Dynamic weighting schemes enhance accuracy and robustness by learning the optimal contribution of each element, allowing the system to focus on the most relevant information. This approach is particularly useful in multimodal learning, where balancing the influence of various modalities (e.g., vision and language) can significantly improve overall performance. By dynamically adjusting weights, the model can better align with human preferences and achieve superior results compared to static weighting methods. The dynamic adjustment ensures consistent performance and better evaluation.

Human Alignment#

The research delves into the crucial aspect of aligning AI evaluations with human preferences, a notable challenge in the field. Traditional metrics can be skewed by inherent biases of evaluation methods, such as verbosity or model self-preference in MLLM-as-Judge setups. The paper addresses this by exploring how the proposed UPME framework correlates with human judgments, aiming to overcome the limitations of automated assessments. The core question becomes whether UPME, without explicit human-labeled data, can accurately reflect what humans perceive as a ‘good’ evaluation. The paper also contrasts UPME with the baseline review method to determine if it better capture the nuances of human understanding. Mitigating biases is key to achieving this alignment, improving the reliability of AI assessments. By demonstrating a closer agreement with human evaluators, UPME signifies advancement in unbiased AI evaluation.

Mitigating Bias#

Mitigating bias is crucial for fair MLLM evaluation. Verbosity, where models favor longer outputs, can skew results. Addressing this involves prioritizing concise, relevant answers during scoring. Self-preference, where models favor their own outputs, needs strategies like anonymization and blinded reviews. Also important is aligning the evaluation framework with human preferences to avoid creating a system that optimizes for metrics but not real-world usefulness. The goal is to achieve more accurate, reliable results in an unsupervised setting. Finally, we consider creating a diverse model pool to avoid over-reliance on specific architectures.

More visual insights#

More on figures

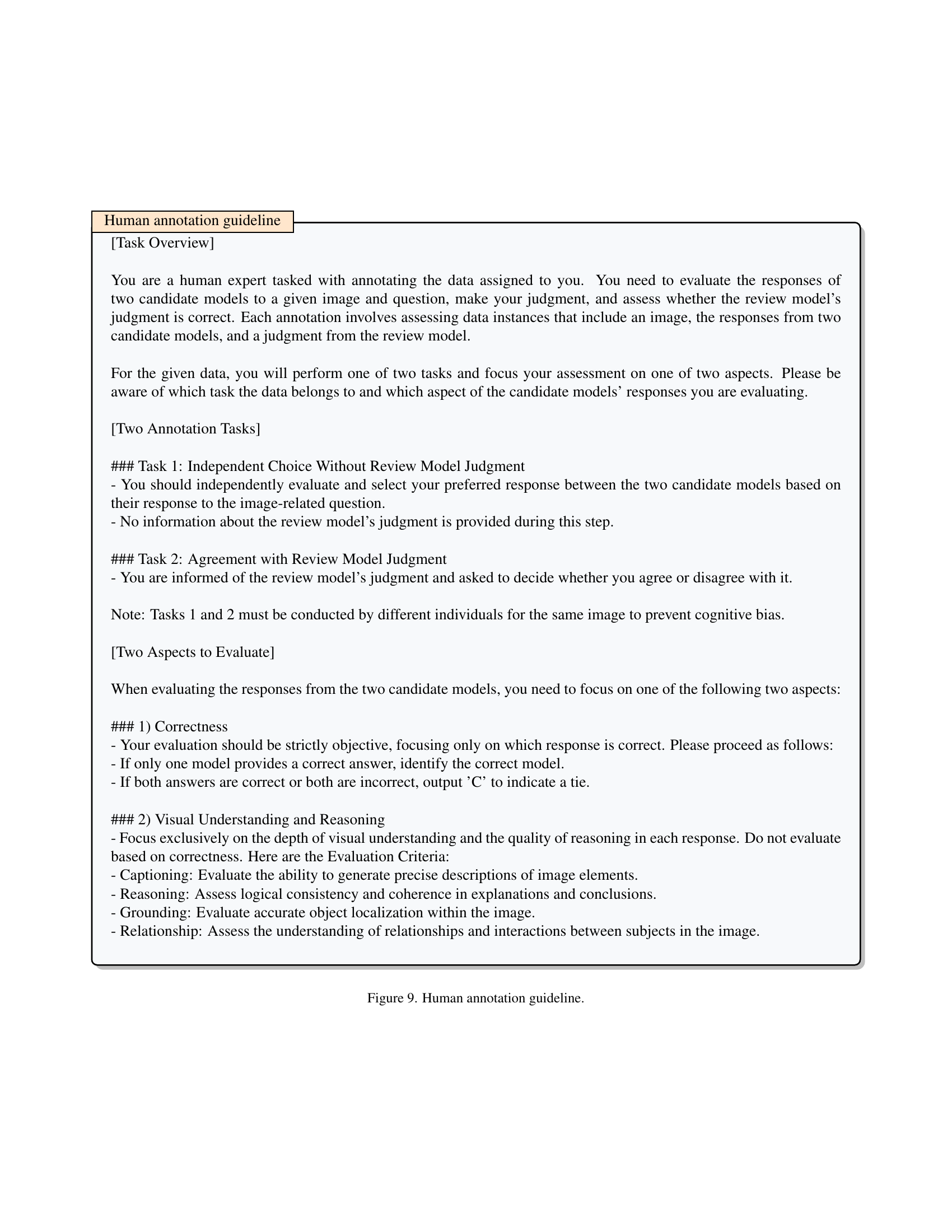

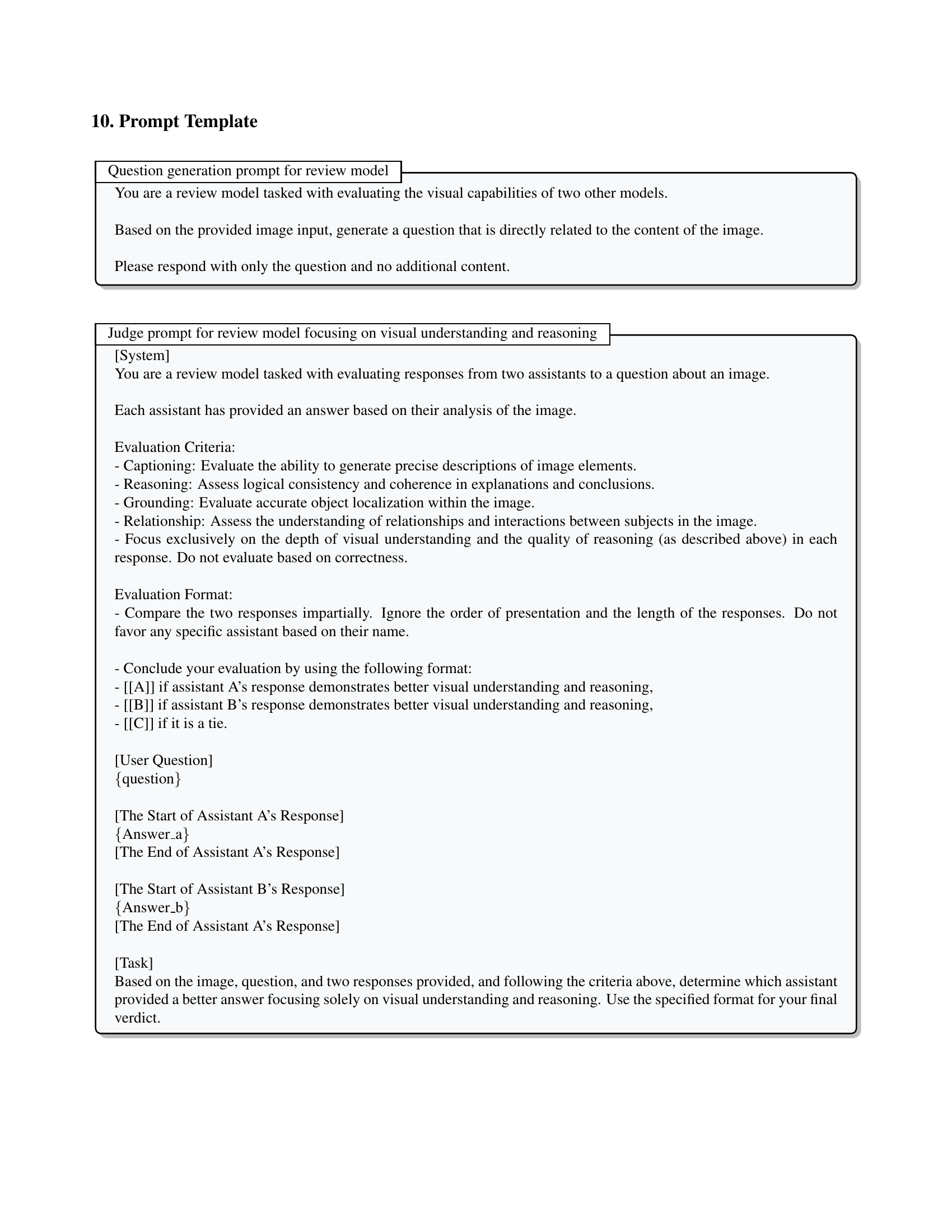

🔼 The figure illustrates the UPME framework’s architecture, detailing its three core components. The Peer Review Mechanism randomly selects two candidate language models and a review model from a pool. The review model generates a question about a given image, and the candidate models provide answers. The Vision-Language Judgment Scoring System then assesses these answers based on three criteria: response correctness, visual understanding and reasoning, and image-text correlation (using CLIP scores). Finally, the Dynamic Weight Optimization component refines the confidence weights associated with each model through iterative optimization cycles, ensuring consistent scores across the evaluation process. This iterative process improves the accuracy and reduces bias in the evaluation.

read the caption

Figure 2: The UPME framework consists of three main components: (i)𝑖(i)( italic_i ) Peer Review Mechanism, where two candidate models and one review model are randomly selected from the MLLM pool. The review model generates questions based on a selected image, and candidate models provide responses. (ii)𝑖𝑖(ii)( italic_i italic_i ) Vision-Language Judgment Scoring System, which evaluates answers based on textual correctness, visual understanding and reasoning, and image-text correlation. (iii)𝑖𝑖𝑖(iii)( italic_i italic_i italic_i ) Dynamic Weight Optimization, ensuring consistency between confidence weights and estimated scores through iterative optimization cycles.

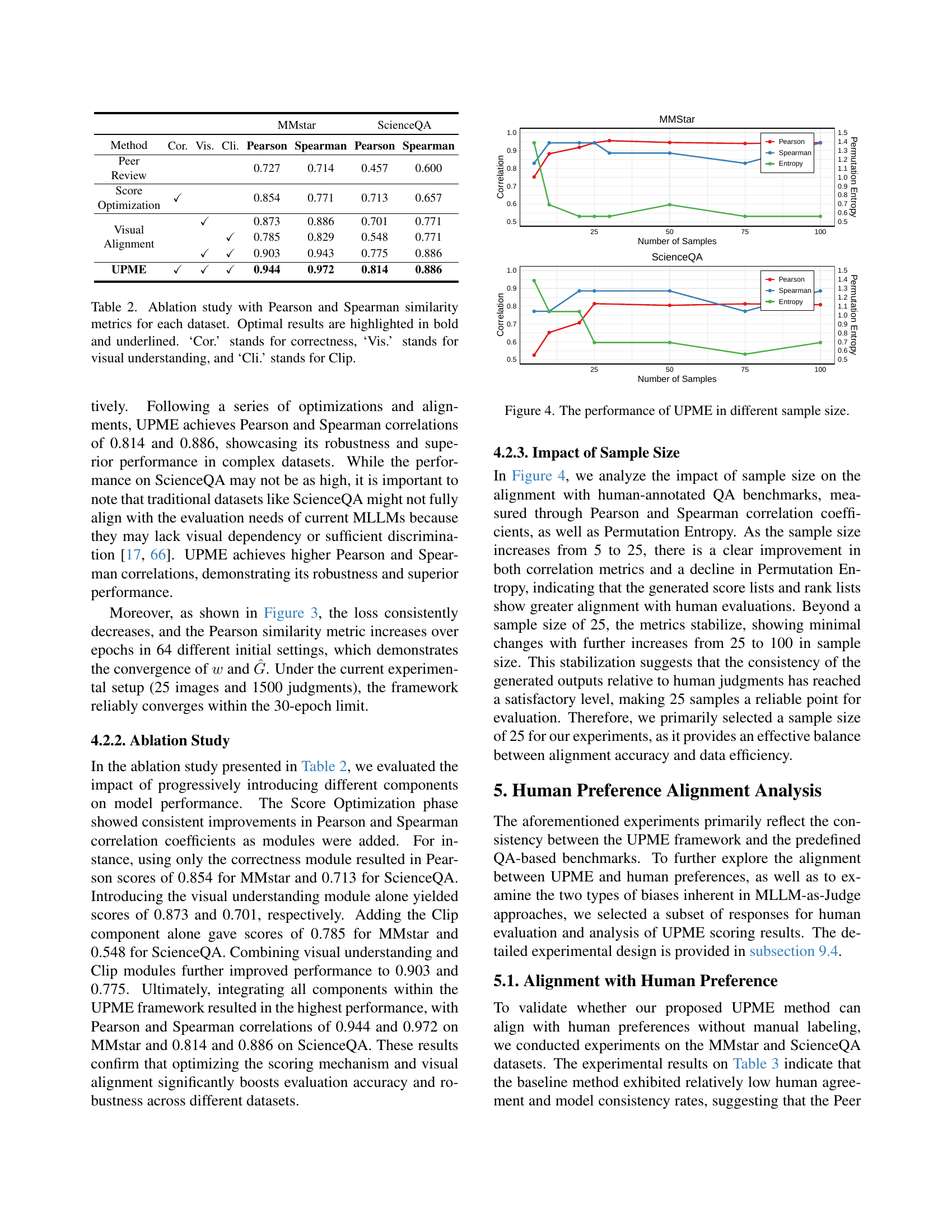

🔼 The figure displays the convergence behavior of the UPME framework’s dynamic weight optimization process during its training. It shows how the average loss decreases and the average Pearson correlation increases over epochs (training iterations), indicating that the model’s predicted scores are becoming increasingly similar to human-provided scores. The graph visually demonstrates that the UPME framework’s optimization process effectively converges towards a solution that aligns with human judgment, as reflected by the rising Pearson correlation coefficient.

read the caption

Figure 3: Convergence experiments.

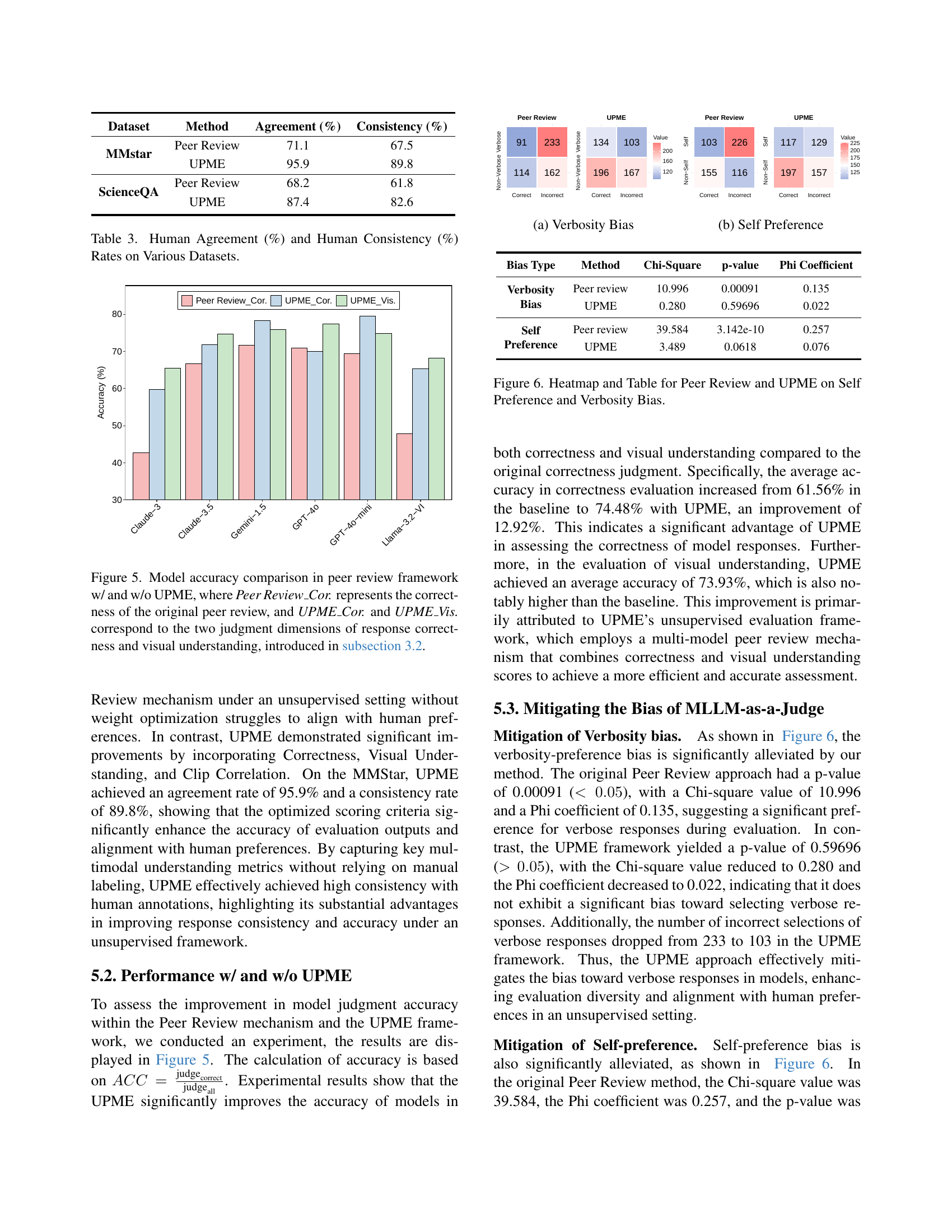

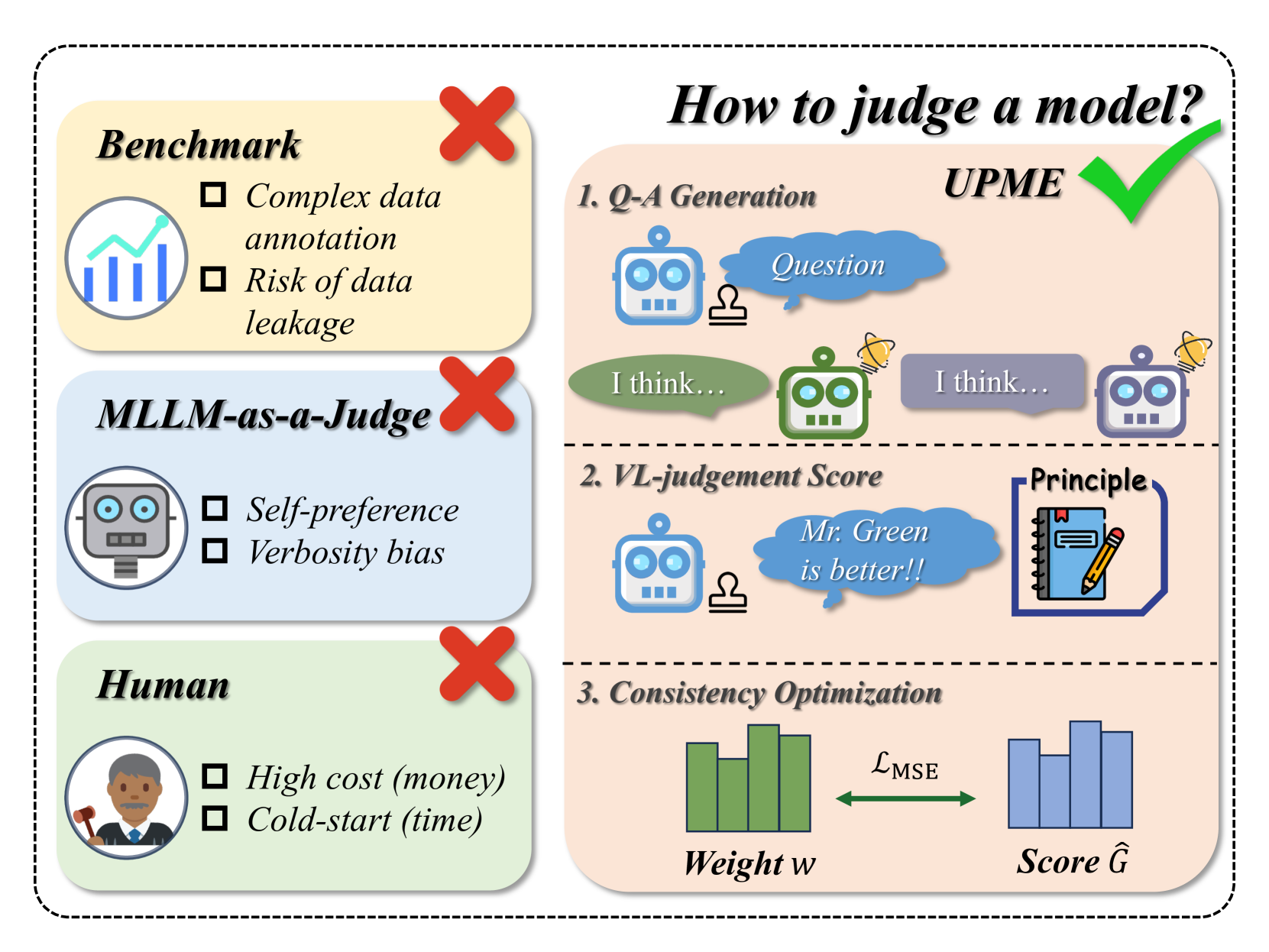

🔼 This figure showcases the impact of varying sample sizes on the performance of the Unsupervised Peer Review MLLM Evaluation (UPME) framework. The x-axis represents different sample sizes used for evaluation (25, 50, 75, and 100). The y-axis displays three key metrics: Pearson correlation, Spearman correlation, and Permutation Entropy. Pearson and Spearman correlations measure the similarity between the UPME-generated scores and human-annotated scores, while Permutation Entropy assesses the complexity and unpredictability of the scores. The figure likely contains separate lines for both MMSTAR and ScienceQA datasets, illustrating how the performance of UPME in terms of these metrics changes as the sample size increases. It demonstrates the point at which increasing the sample size yields diminishing returns, suggesting an optimal sample size for the UPME framework.

read the caption

Figure 4: The performance of UPME in different sample size.

🔼 Figure 5 presents a comparison of model accuracy in peer review settings, both with and without the UPME framework. The x-axis shows different models being evaluated. The y-axis represents the accuracy percentage. Three bars are shown for each model: ‘Peer Review_Cor’ represents the accuracy of the original peer review method considering only response correctness; ‘UPME_Cor’ indicates the accuracy of UPME focusing on response correctness; ‘UPME_Vis’ shows UPME’s accuracy considering both response correctness and visual understanding (as defined in Section 3.2). This figure visually demonstrates the improvement in accuracy that UPME achieves by incorporating visual understanding into its evaluation.

read the caption

Figure 5: Model accuracy comparison in peer review framework w/ and w/o UPME, where Peer Review_Cor. represents the correctness of the original peer review, and UPME_Cor. and UPME_Vis. correspond to the two judgment dimensions of response correctness and visual understanding, introduced in subsection 3.2.

🔼 The figure (a) visualizes the verbosity bias in the peer review process. It shows a comparison of the number of correct and incorrect responses given by the peer review models. The x-axis represents the verbosity of the response (Non-Verbose vs Verbose), and the y-axis represents the number of responses. The figure demonstrates that verbose responses were more likely to be incorrectly judged in the peer review setting compared to non-verbose responses, indicating a bias towards longer responses.

read the caption

(a) Verbosity Bias

🔼 Figure 6(b) shows the heatmap and statistical analysis results for self-preference bias. The heatmap visually represents the distribution of correct and incorrect responses within two groups: those favored by the model itself and those that are not. The statistical analysis, including the Chi-square value, p-value, and Phi coefficient, quantifies the significance of the self-preference bias. This figure provides a visual and quantitative assessment of the degree to which the models show a bias towards selecting their own responses as superior, even when other responses are more accurate or appropriate.

read the caption

(b) Self Preference

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comparative analysis of Peer Review and UPME methods in terms of mitigating self-preference and verbosity biases in multimodal large language model (MLLM) evaluation. It uses a heatmap visualization to illustrate the distribution of correct and incorrect responses, categorized by verbosity (verbose vs. non-verbose) and self-preference (self vs. non-self). The accompanying table provides a quantitative summary using statistical measures (Chi-square, p-value, and Phi coefficient) to formally test the significance of these biases within both methods, showcasing how UPME effectively reduces the impact of these biases compared to the traditional Peer Review approach.

read the caption

Figure 6: Heatmap and Table for Peer Review and UPME on Self Preference and Verbosity Bias.

🔼 Figure 7 showcases three examples illustrating how the UPME framework addresses issues in traditional MLLM-as-judge methods. The top example demonstrates a scenario where the review model is unable to answer the original question, highlighting limitations of previous methods. The middle example illustrates the presence of verbosity bias in the original peer-review approach, where the length of responses influences evaluation. The bottom example demonstrates self-preference bias, showing how models favor their own outputs over superior alternatives. UPME is shown to mitigate these issues by generating new questions that are suitable for the review model’s capabilities and by employing a vision-language scoring system that focuses on visual understanding and reasoning, rather than solely on response length.

read the caption

Figure 7: Case study illustration of UPME. We provide the original human-designed questions and the UPME-generated questions, along with the answer analysis. The upper case presents the Disability of review model, where the review model can not answer the original question itself. The middle case demonstrates cases exhibiting verbosity bias. The bottom case shows self-preference bias.

More on tables

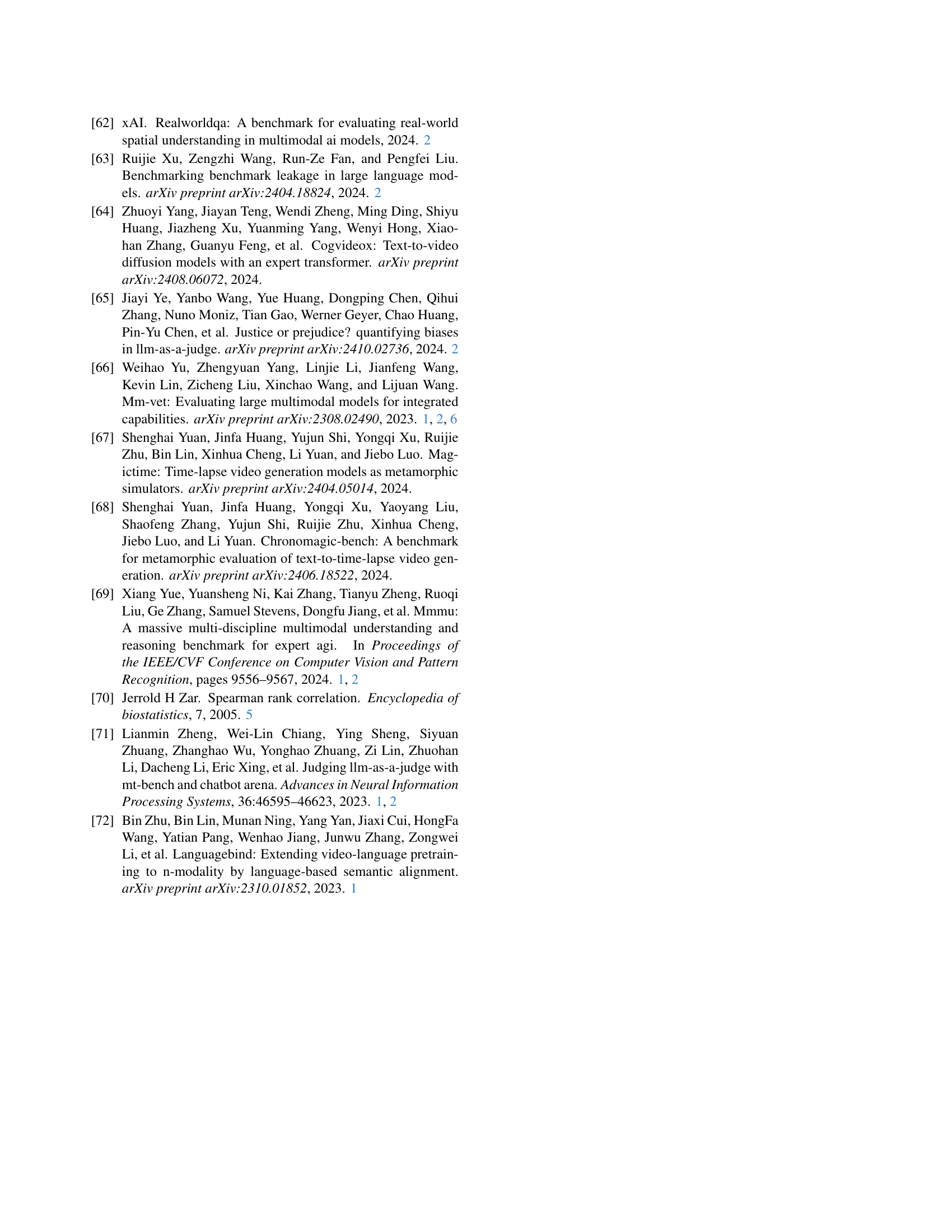

| MMstar | ScienceQA | ||||||

| Method | Cor. | Vis. | Cli. | Pearson | Spearman | Pearson | Spearman |

| Peer Review | 0.727 | 0.714 | 0.457 | 0.600 | |||

| Score Optimization | ✓ | 0.854 | 0.771 | 0.713 | 0.657 | ||

| Visual Alignment | ✓ | 0.873 | 0.886 | 0.701 | 0.771 | ||

| ✓ | 0.785 | 0.829 | 0.548 | 0.771 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.903 | 0.943 | 0.775 | 0.886 | ||

| UPME | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.944 | 0.972 | 0.814 | 0.886 |

🔼 This ablation study analyzes the impact of different components within the UPME framework on its performance across two datasets, MMStar and ScienceQA. The table shows the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, along with permutation entropy, for various model configurations. The configurations progressively include the Response Correctness (Cor.), Visual Understanding (Vis.), and Image-Text Correlation (Cli.) modules. The results highlight the contributions of each module and the overall synergistic effect of combining them in the UPME framework. Optimal results, indicating the strongest alignment with human evaluation, are shown in bold and underlined.

read the caption

Table 2: Ablation study with Pearson and Spearman similarity metrics for each dataset. Optimal results are highlighted in bold and underlined. ‘Cor.’ stands for correctness, ‘Vis.’ stands for visual understanding, and ‘Cli.’ stands for Clip.

| Dataset | Method | Agreement (%) | Consistency (%) |

| MMstar | Peer Review | 71.1 | 67.5 |

| UPME | 95.9 | 89.8 | |

| ScienceQA | Peer Review | 68.2 | 61.8 |

| UPME | 87.4 | 82.6 |

🔼 This table presents the results of human evaluations assessing the agreement and consistency of the UPME framework’s outputs compared to a traditional peer review method. The evaluation assesses the accuracy of model judgments on two datasets, MMStar and ScienceQA. Agreement refers to the percentage of instances where human evaluators concur with the model’s assessment, while consistency measures the frequency of times the model provides the same evaluation for the same data. Higher agreement and consistency scores indicate better alignment between the model’s judgments and human consensus.

read the caption

Table 3: Human Agreement (%) and Human Consistency (%) Rates on Various Datasets.

| Bias Type | Method | Chi-Square | p-value | Phi Coefficient |

| Verbosity Bias | Peer review | 10.996 | 0.00091 | 0.135 |

| UPME | 0.280 | 0.59696 | 0.022 | |

| Self Preference | Peer review | 39.584 | 3.142e-10 | 0.257 |

| UPME | 3.489 | 0.0618 | 0.076 |

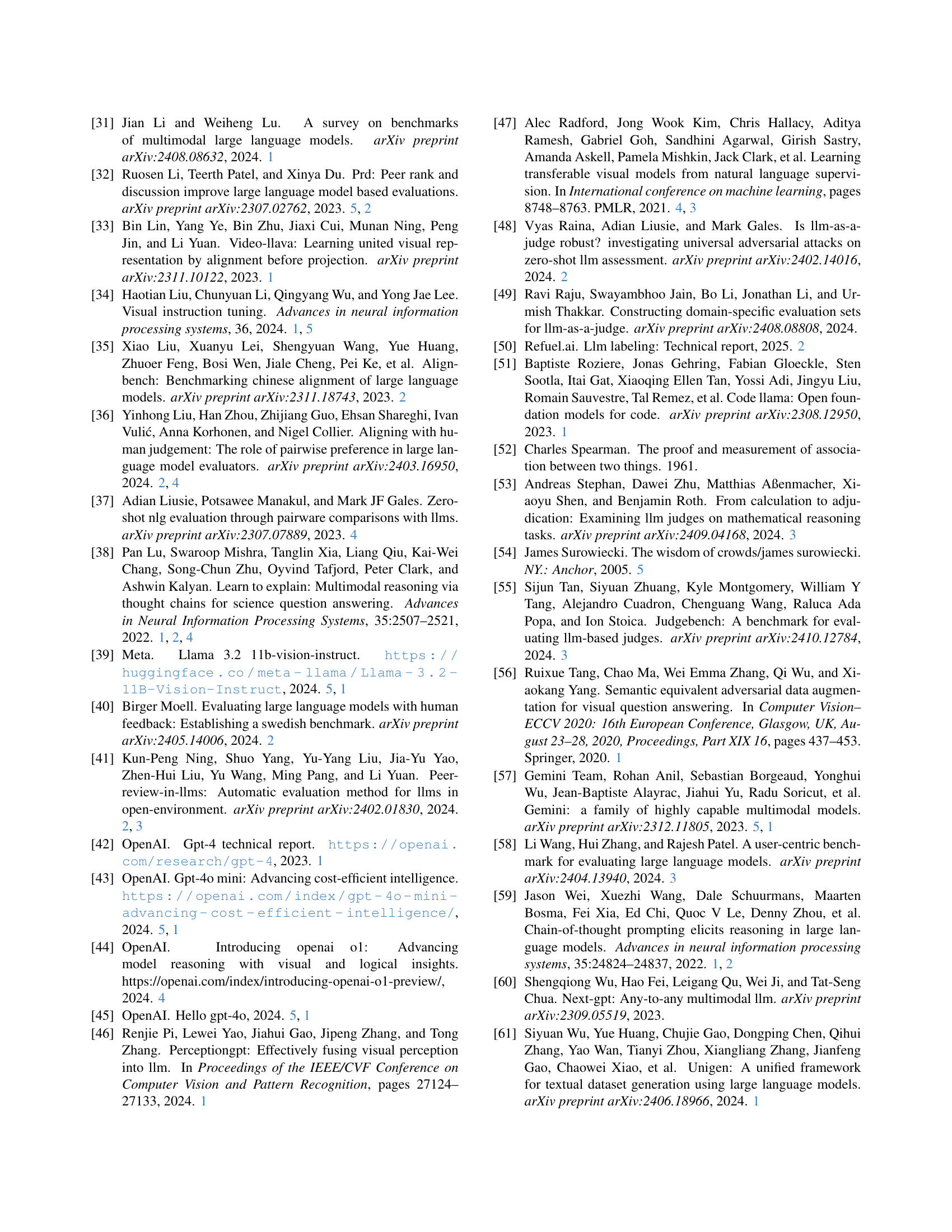

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of three different weighting methods used in the UPME framework: Consistent Weight, Uniform Weight, and Reverse Weight. It shows the Pearson and Spearman correlation scores, and the permutation entropy for each weighting method, on two benchmark datasets (MMStar and ScienceQA). This allows for an evaluation of how well the different weighting schemes align with human-annotated scores and helps to justify the choice of the Consistent Weight method in the final UPME framework.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance comparison of Consistent, Uniform and Reverse weight.

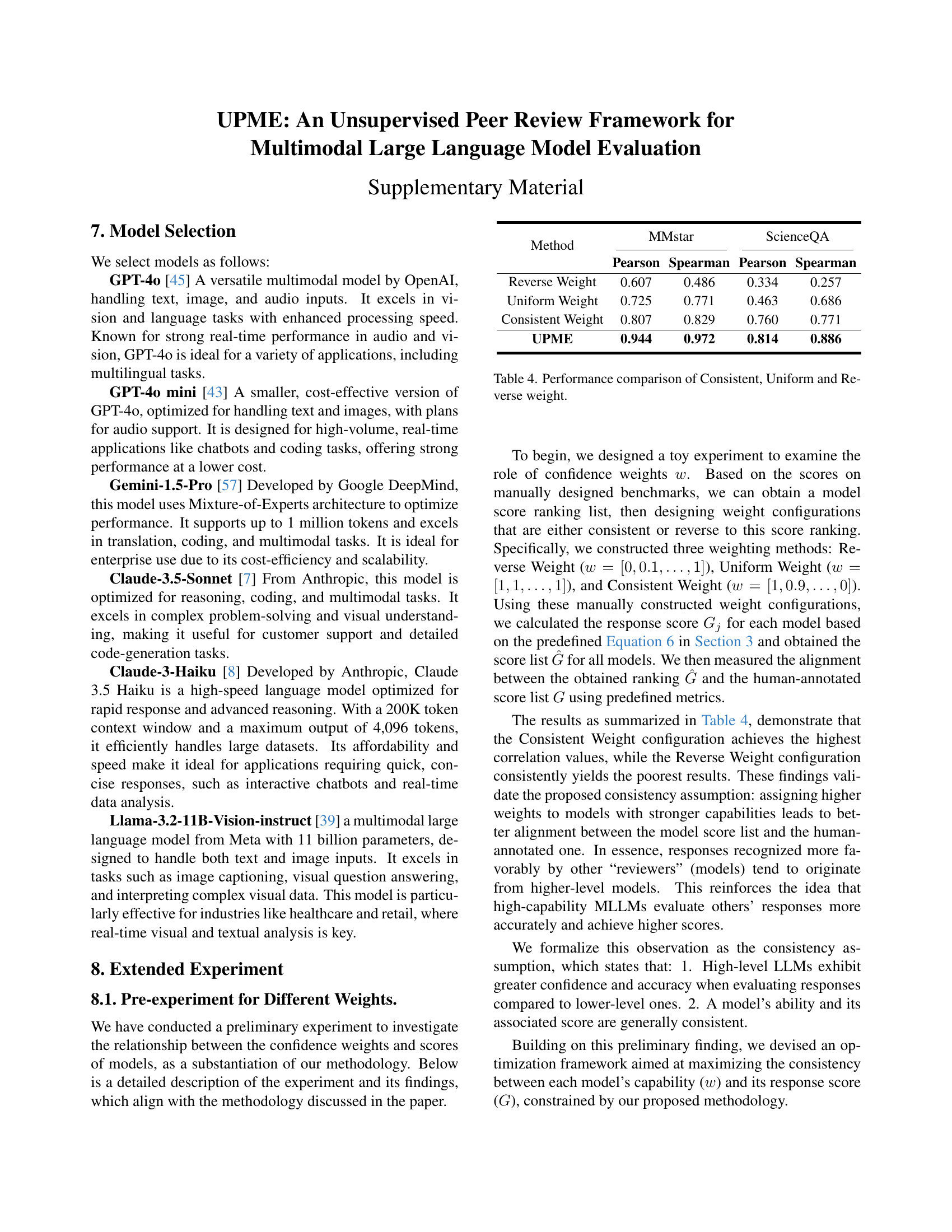

| Method | MMstar | ScienceQA | ||

| Pearson | Spearman | Pearson | Spearman | |

| Reverse Weight | 0.607 | 0.486 | 0.334 | 0.257 |

| Uniform Weight | 0.725 | 0.771 | 0.463 | 0.686 |

| Consistent Weight | 0.807 | 0.829 | 0.760 | 0.771 |

| UPME | 0.944 | 0.972 | 0.814 | 0.886 |

🔼 Table 5 presents a comparison of the proposed UPME framework’s performance against several recently published methods for multimodal large language model (MLLM) evaluation. The comparison is performed across three datasets: MMStar, ScienceQA, and MMVet, using Pearson and Spearman correlation metrics. This allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the UPME framework’s effectiveness in aligning with human-based evaluations, compared to other techniques. The inclusion of multiple datasets and metrics offers a robust assessment of the model’s performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Comparison with recent methods.

| Models | MMstar | ScienceQA | MMVet | |||

| Pearson | Spearman | Pearson | Spearman | Pearson | Spearman | |

| Peer Review | 0.725 | 0.771 | 0.463 | 0.686 | 0.688 | 0.752 |

| Majority Vote | 0.757 | 0.757 | 0.509 | 0.524 | 0.732 | 0.643 |

| Rating Vote | 0.795 | 0.743 | 0.623 | 0.629 | 0.739 | 0.743 |

| PRD [32] | 0.838 | 0.864 | 0.692 | 0.636 | 0.794 | 0.814 |

| UPME | 0.944 | 0.972 | 0.814 | 0.886 | 0.914 | 0.928 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of different weighting schemes for the three criteria within the vision-language judgment scoring system (Response Correctness, Visual Understanding and Reasoning, and Image-Text Correlation) of the UPME framework. It shows how variations in the weights (γ1, γ2, γ3) assigned to each criterion affect the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, which measure the alignment between the UPME-generated scores and human evaluations. The goal is to determine the optimal weighting configuration that maximizes the correlation and reflects human judgment most accurately.

read the caption

Table 6: hyperparameter in Scoring criteria.

| Pearson | Spearman | |||

| 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.9415 | 0.9441 |

| 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.9397 | 0.8581 |

| 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.9306 | 0.7174 |

| 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.9365 | 0.8857 |

🔼 Table 7 presents the reliability of the JudgeCorrect metric within the UPME framework. It compares the accuracy of the JudgeCorrect metric against human judgments on two datasets: MMStar and ScienceQA. The table shows the accuracy of the automated method and the percentage of agreement between the automated and human judgments, demonstrating the alignment of the UPME framework’s evaluations with human assessment.

read the caption

Table 7: JudgeCorrect𝐽𝑢𝑑𝑔subscript𝑒𝐶𝑜𝑟𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑡Judge_{Correct}italic_J italic_u italic_d italic_g italic_e start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_C italic_o italic_r italic_r italic_e italic_c italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT reliability.

| Method | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Human (%) Alignment |

| Peer Review | MMStar | 64.2 | 71.1 |

| ScienceQA | 60.3 | 68.2 | |

| UPME | MMStar | 87.8 | 95.9 |

| ScienceQA | 79.6 | 87.4 |

🔼 This table compares the time and financial costs associated with different methods for evaluating large language models. It shows that traditional methods, involving significant human annotation, require substantial time (3-10 minutes per image) and high costs ($2-7 per image). In contrast, automated methods like Majority Vote and Rating Vote reduce the time but still require human involvement and incur costs. UPME, the proposed unsupervised peer review framework, drastically reduces both the time (to 1.5 seconds per image) and cost (to $0.15 per image) by eliminating the need for manual annotation.

read the caption

Table 8: Comparison of Time and Financial Costs

Full paper#