TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) often struggle to retain factual knowledge, leading to errors. Exhaustively evaluating LLMs against full-scale knowledge bases is computationally prohibitive, especially for closed-weight models. Therefore, pinpointing knowledge deficiencies is hard. Researchers typically construct static knowledge-intensive benchmarks. However, it’s infeasible to curate static benchmarks that cover all knowledge, so a versatile approach is needed to uncover LLM’s knowledge deficiencies.

This paper introduces Stochastic Error Ascent (SEA), a scalable framework for discovering knowledge deficiencies in closed-weight LLMs under a query budget. SEA formulates error discovery as stochastic optimization, iteratively retrieving high-error candidates using semantic similarity to previous failures. It uses hierarchical retrieval across document and paragraph levels, and models error propagation with a relation directed acyclic graph. SEA uncovers more errors at a lower cost and reveals correlated failure patterns.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper introduces SEA, a framework to discover LLMs’ knowledge deficiencies, which is significant for high-stakes applications. Its scalability and efficiency address the challenge of evaluating closed-weight models, offering new directions for targeted fine-tuning and better data coverage in LLM development.

Visual Insights#

🔼 The figure illustrates the SEA (Stochastic Error Ascent) framework. Starting with a knowledge base and a closed-weight language model, SEA iteratively identifies knowledge gaps. It begins by randomly sampling a small set of questions from the knowledge base to assess the model’s accuracy. Subsequent iterations leverage semantic similarity to identify additional questions likely to reveal further errors, making the process efficient. A directed acyclic graph tracks error dependencies to highlight systematic failures. The process continues until a pre-defined budget (e.g., number of queries) is exhausted. The final output helps pinpoint the model’s specific knowledge deficiencies and patterns of errors.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overall workflow of stochastic error ascent (SEA). We search for a closed-weight model’s unknown knowledge iteratively from a given knowledge base until we reach the budget. The result from SEA can be further used to analyze the model’s unknown categories and error patterns.

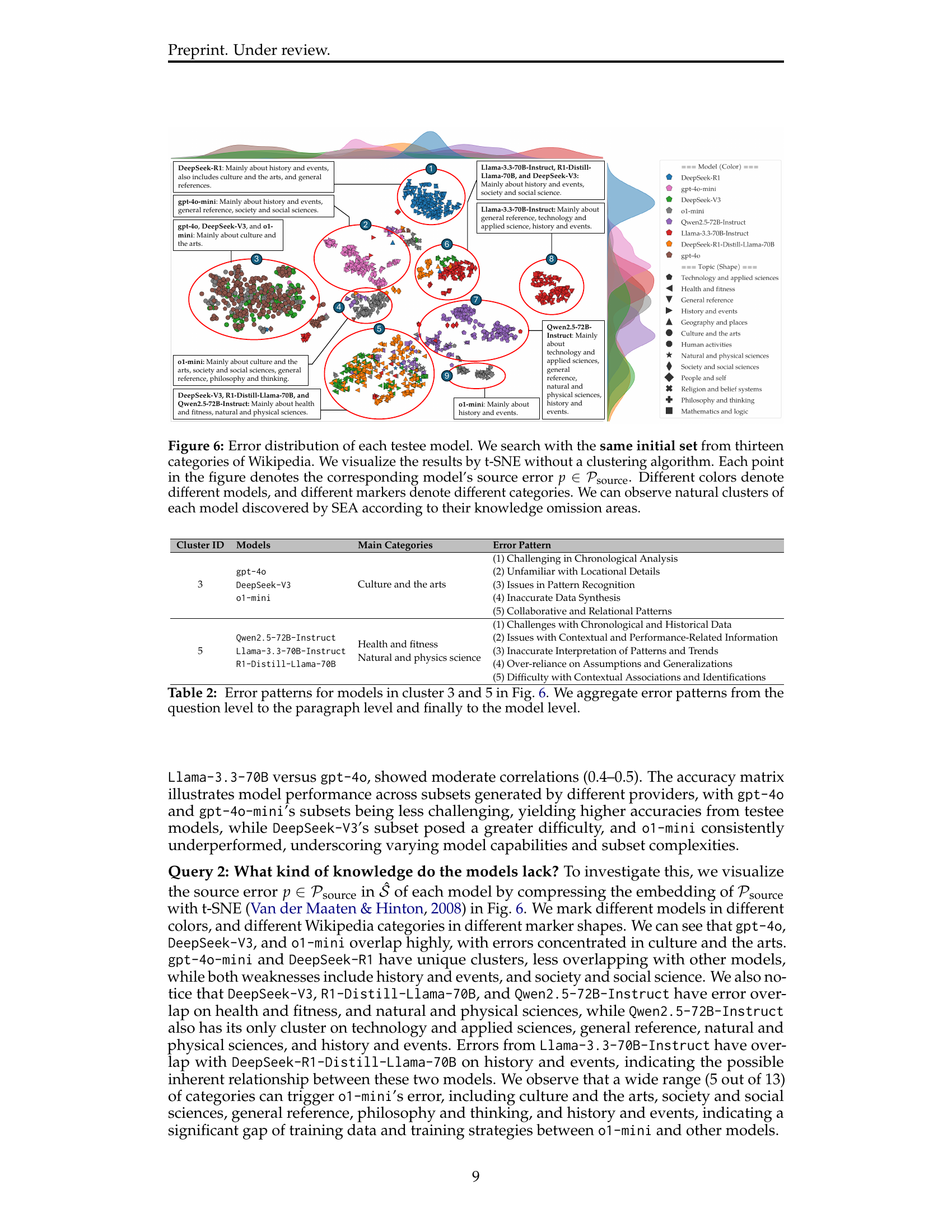

| \rowcolorgray!50 Cluster ID | Models | Main Categories | Error Pattern | ||||||||||

| 3 |

| Culture and the arts |

| ||||||||||

| 5 |

|

|

|

🔼 This table presents an analysis of error patterns exhibited by different language models within two specific clusters (3 and 5) identified in Figure 6. The analysis is hierarchical: it starts by examining individual question-level errors, aggregates them into paragraph-level patterns, and ultimately summarizes these patterns at the model level. This provides a detailed understanding of the types of knowledge deficiencies and systematic weaknesses present in each model within the clusters.

read the caption

Table 1: Error patterns for models in cluster 3 and 5 in Fig. 6. We aggregate error patterns from the question level to the paragraph level and finally to the model level.

In-depth insights#

Error Ascent#

The Error Ascent strategy, likely a key component of this research, appears to be an iterative process for identifying and rectifying weaknesses in a system, perhaps an AI model. It probably involves intentionally introducing errors or noise to understand how the system responds, then using that insight to refine its abilities. The “ascent” part suggests a gradual, step-by-step improvement. This approach could be particularly effective when dealing with complex tasks. In essence, Error Ascent seems to be a targeted and progressive methodology for enhancing system robustness and reliability by actively confronting and mitigating vulnerabilities. The overall goal would be to minimize failures and maximize accuracy. This iterative method is designed for a closed-weight LM.

Relation DAG#

Relation DAG, as described in the paper, is crucial for identifying systematic weaknesses in language models (LLMs). It traces dependencies between source errors, forming a directed acyclic graph. By linking paragraphs based on semantic similarity and error propagation, the DAG helps uncover flaws localized within specific regions of the knowledge base. The DAG prunes low-impact nodes based on cumulative errors, enhancing efficiency. This targeted approach enables a deeper understanding of how errors propagate and correlate within LLMs, offering insights beyond isolated instances of misinformation. Analyzing the Relation DAG provides a structured method for pinpointing vulnerabilities, leading to more effective mitigation strategies.

Model Biases#

Analyzing model biases is critical for understanding the limitations and potential failures of language models. Different models exhibit different biases due to variations in architecture, training data, and optimization strategies. These biases can manifest as preferences for certain demographics, topics, or reasoning styles, leading to unfair or inaccurate outputs. Careful analysis can uncover these biases, potentially through techniques like counterfactual testing or probing internal representations, enabling the development of mitigation strategies and more reliable, trustworthy models. It is important to note that all models have biases; identifying and quantifying them is the key step.

Scalable Defect#

Scalable Defect in language models refers to knowledge deficiencies that persist even with increased model size and data. The paper addresses this by proposing Stochastic Error Ascent (SEA), a scalable approach to uncover those flaws. SEA discovers more errors than baselines, highlighting that many LLM errors are systematic rather than random. This means simply scaling model size won’t eliminate them; targeted interventions are needed. It’s crucial to acknowledge that, as more parameters don’t guarantee factual accuracy or eliminate biases, scalable defect is a critical area for exploration, it shows us how LLMs’ knowledge can be enhanced.

Evolving Bench.#

Evolving benchmarks address limitations of static datasets. Traditional benchmarks can suffer from data leakage or be gamed by models, losing their diagnostic value. An evolving benchmark adapts over time, often through automated data generation or adversarial interaction. This can help continuously challenge models and reveal new weaknesses as they improve. The goal is a benchmark that remains relevant and informative, driving progress by exposing model limitations in a dynamic way, ensuring continued evaluation of capabilities, and providing researchers a method to evaluate model performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

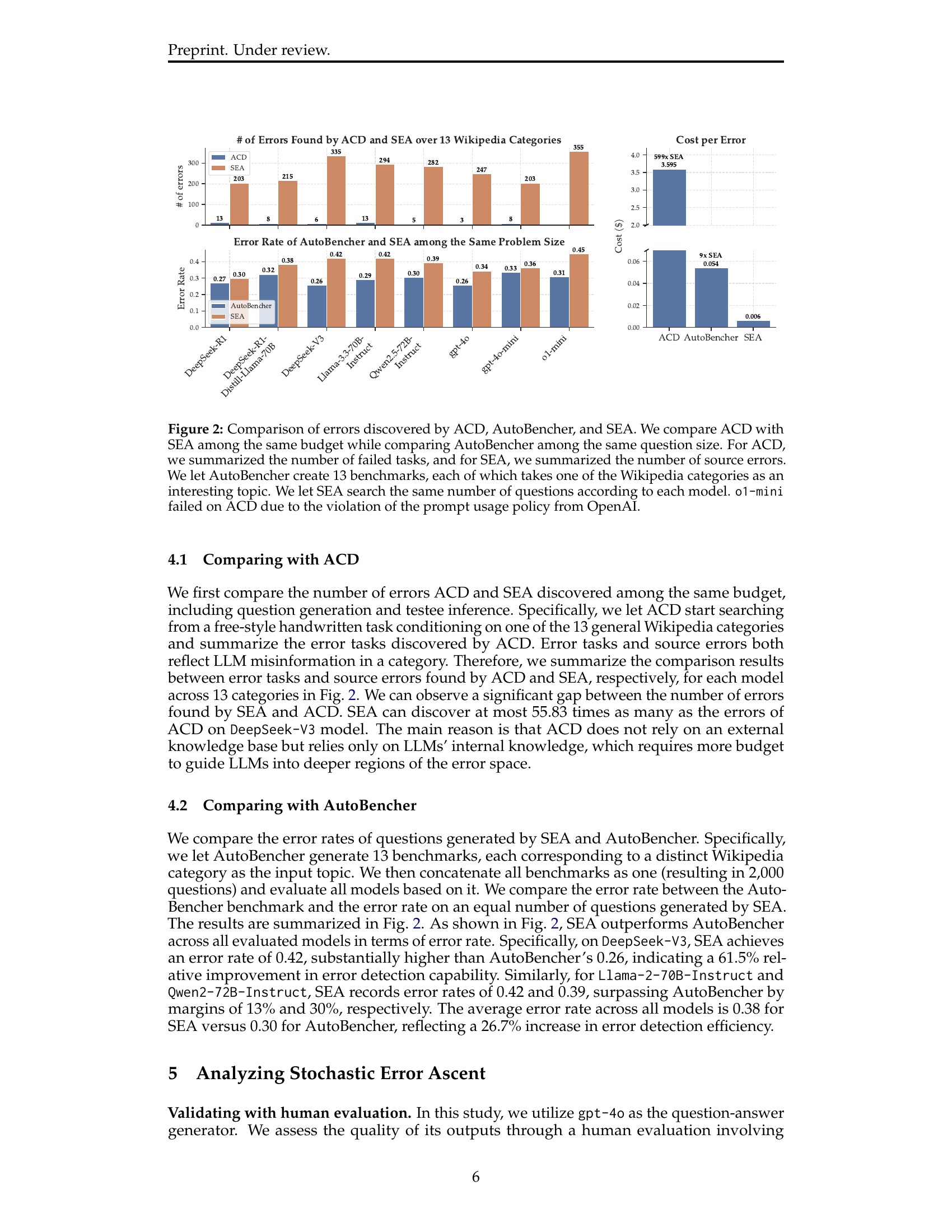

🔼 Figure 2 presents a comparison of the effectiveness of three different methods – Automated Capability Discovery (ACD), AutoBencher, and Stochastic Error Ascent (SEA) – in identifying knowledge deficiencies in Language Models (LLMs). ACD and SEA are compared using the same budget, meaning the same computational resources were allocated to each. The number of errors found is represented by the number of ‘failed tasks’ for ACD and ‘source errors’ for SEA. AutoBencher is compared by keeping the number of questions generated the same as SEA, while it creates 13 benchmarks, each based on a different Wikipedia category. The figure highlights the significant advantage of SEA in terms of both the quantity of errors detected and the cost-per-error, compared to the baseline methods. Notably, o1-mini failed in ACD due to OpenAI’s prompt usage policy restrictions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of errors discovered by ACD, AutoBencher, and SEA. We compare ACD with SEA among the same budget while comparing AutoBencher among the same question size. For ACD, we summarized the number of failed tasks, and for SEA, we summarized the number of source errors. We let AutoBencher create 13 benchmarks, each of which takes one of the Wikipedia categories as an interesting topic. We let SEA search the same number of questions according to each model. o1-mini failed on ACD due to the violation of the prompt usage policy from OpenAI.

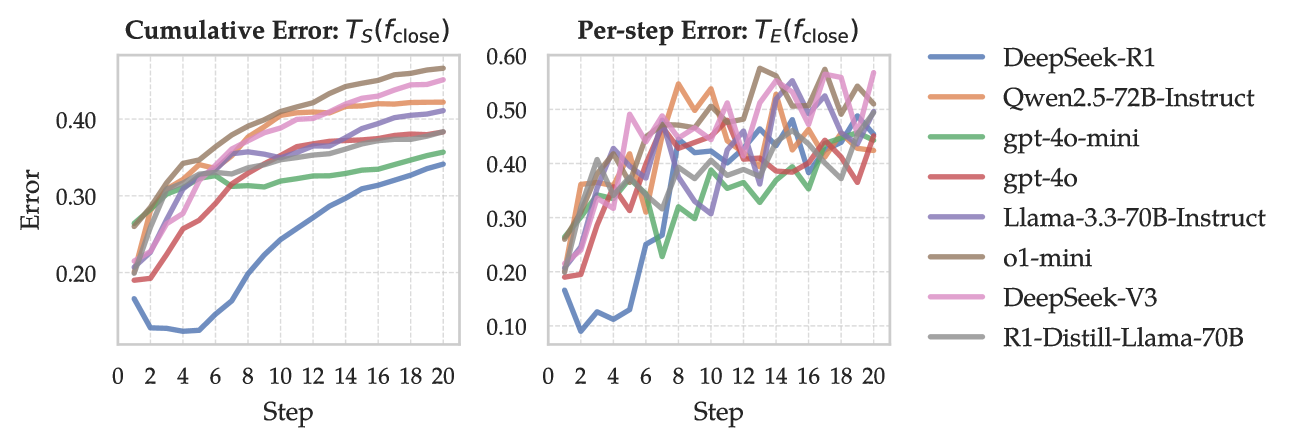

🔼 This figure displays the per-step error and cumulative error of different large language models (LLMs) throughout the iterative error discovery process of the SEA framework. The per-step error (TE(fclose)) represents the average error rate at each step, while the cumulative error (TS(fclose)) shows the total accumulated error up to that step. The x-axis represents the step number in the SEA process, and the y-axis indicates the error rate. Each line in the plot represents a different LLM, illustrating how their error rates change as SEA progresses. The positive correlation between error and step number demonstrates SEA’s effectiveness in uncovering LLM knowledge deficiencies. The figure visually shows that SEA gradually identifies increasingly challenging errors.

read the caption

Figure 3: Per-step error TE(fclose)subscript𝑇𝐸subscript𝑓closeT_{E}(f_{\text{close}})italic_T start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_E end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( italic_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT close end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ) and cumulative error T𝒮(fclose)subscript𝑇𝒮subscript𝑓closeT_{{\mathcal{S}}}(f_{\text{close}})italic_T start_POSTSUBSCRIPT caligraphic_S end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( italic_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT close end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ) for each model. We observe that the errors of all models are positively related to step, indicating SEA can gradually and continually find the model’s knowledge deficiencies from the knowledge base.

🔼 This figure presents an ablation study analyzing the contribution of different components within the SEA (Stochastic Error Ascent) framework. Three versions of SEA are compared: the complete SEA model, a version without source pruning (removing low-impact error sources), and a version employing random paragraph selection instead of the error-driven selection process. The results show that all three components (error-driven selection, source pruning, and hierarchical retrieval) contribute equally to the overall effectiveness of SEA in discovering knowledge errors in LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 4: Ablation studies on the component contribution of SEA. We compare SEA with its two variants: without source pruning (i.e., pass the lines 10 and 11 in Alg. 1) and random selection (i.e., pass the lines 9, 10, and 11 in Alg. 1). We observe that each component contributes equally to SEA.

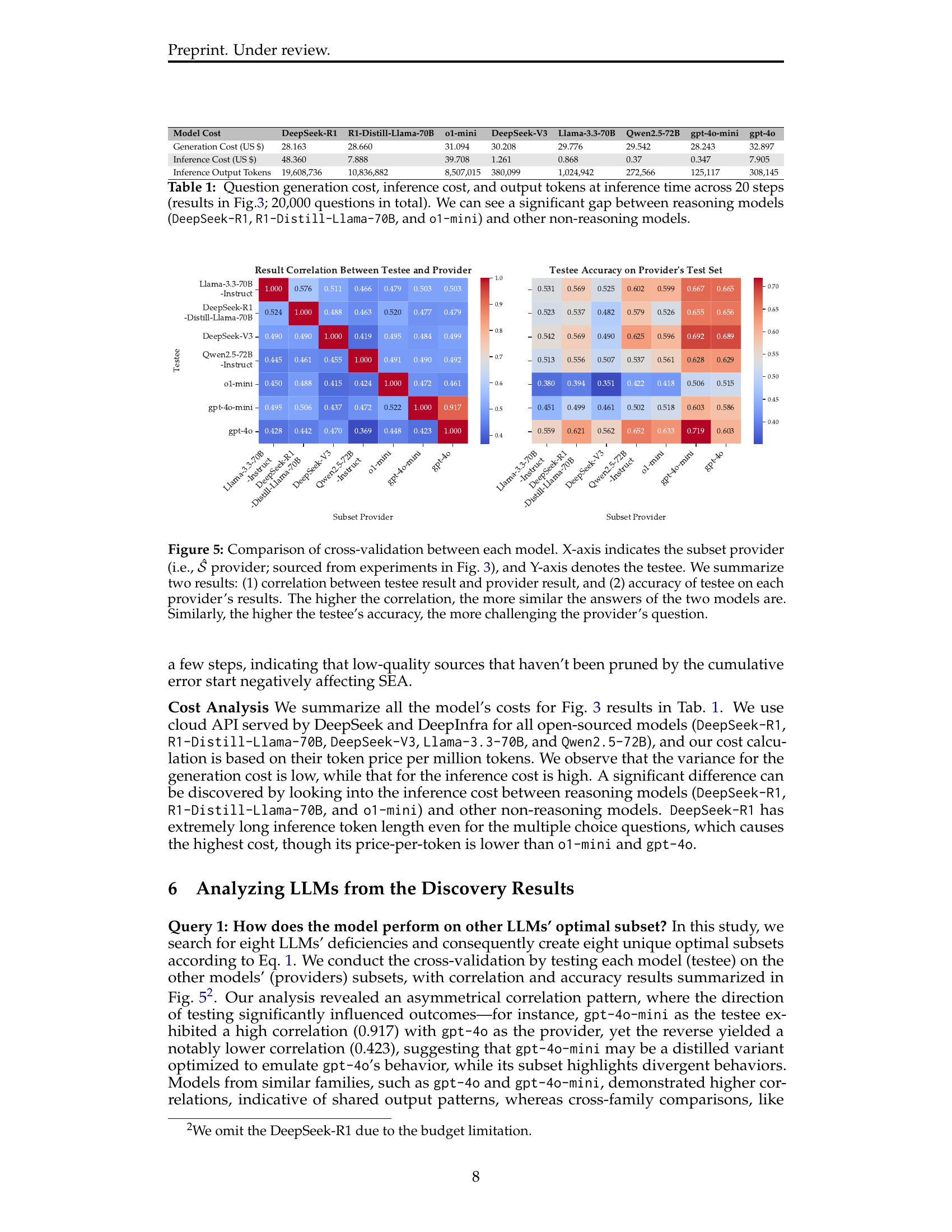

🔼 This figure displays a heatmap visualizing the cross-validation results between different large language models (LLMs). The X-axis represents the LLM that generated the question subset (the ‘provider’), and the Y-axis shows the LLM answering those questions (the ’testee’). Two key metrics are presented: (1) The correlation coefficient between the provider’s and the testee’s answers for each question, indicating the similarity of their responses; higher correlation signifies greater agreement. (2) The testee’s accuracy on the question subset provided by each provider. This represents the difficulty of the questions posed by different LLMs; higher accuracy indicates easier questions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparison of cross-validation between each model. X-axis indicates the subset provider (i.e., 𝒮^^𝒮\hat{{\mathcal{S}}}over^ start_ARG caligraphic_S end_ARG provider; sourced from experiments in Fig. 3), and Y-axis denotes the testee. We summarize two results: (1) correlation between testee result and provider result, and (2) accuracy of testee on each provider’s results. The higher the correlation, the more similar the answers of the two models are. Similarly, the higher the testee’s accuracy, the more challenging the provider’s question.

🔼 This figure visualizes the distribution of errors discovered by the SEA method for different language models across various categories from Wikipedia’s knowledge base. Each point represents a specific error, with color indicating the language model and shape representing the Wikipedia category the error belongs to. The visualization uses t-SNE to reduce the dimensionality of the data for better visual representation. The plot reveals distinct clusters of errors for each model, highlighting the types of knowledge each model struggles with and providing insights into their specific knowledge deficiencies.

read the caption

Figure 6: Error distribution of each testee model. We search with the same initial set from thirteen categories of Wikipedia. We visualize the results by t-SNE without a clustering algorithm. Each point in the figure denotes the corresponding model’s source error p∈𝒫source𝑝subscript𝒫sourcep\in{\mathcal{P}}_{\text{source}}italic_p ∈ caligraphic_P start_POSTSUBSCRIPT source end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. Different colors denote different models, and different markers denote different categories. We can observe natural clusters of each model discovered by SEA according to their knowledge omission areas.

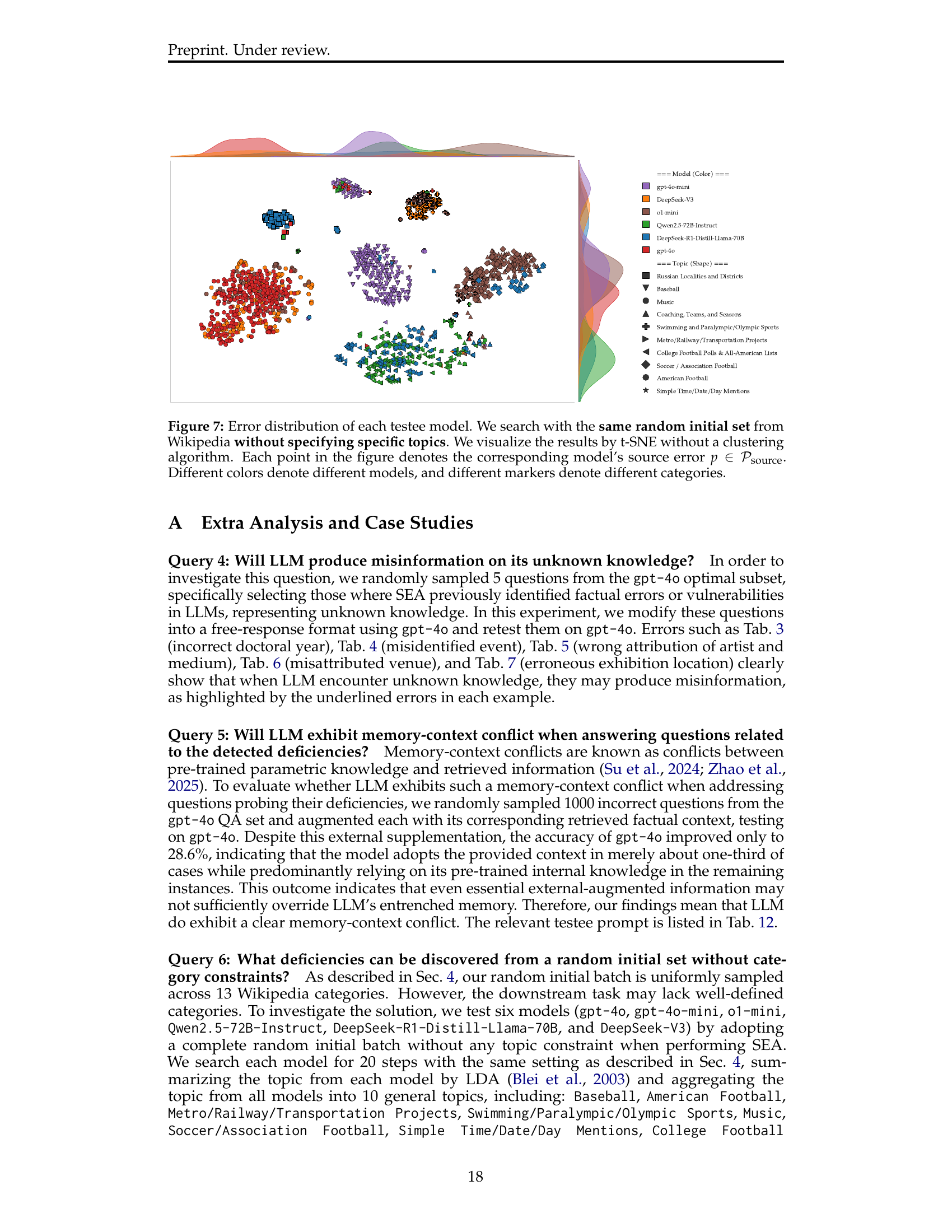

🔼 Figure 7 visualizes the distribution of errors identified by the SEA algorithm across different LLMs, without pre-selecting specific topics from the Wikipedia knowledge base. The t-SNE algorithm is employed to reduce the high-dimensional error data into a 2D representation for visualization. Each point in the graph represents a single error identified by SEA (denoted as p∈𝒫sourcep in ewlinemathcal{P}_{source} ), with the color indicating the LLM model that made the error and the shape representing the Wikipedia category where the error occurred. This visualization allows for a direct comparison of the error patterns of various LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 7: Error distribution of each testee model. We search with the same random initial set from Wikipedia without specifying specific topics. We visualize the results by t-SNE without a clustering algorithm. Each point in the figure denotes the corresponding model’s source error p∈𝒫source𝑝subscript𝒫sourcep\in{\mathcal{P}}_{\text{source}}italic_p ∈ caligraphic_P start_POSTSUBSCRIPT source end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. Different colors denote different models, and different markers denote different categories.

More on tables

| gpt-4o |

| DeepSeek-V3 |

| o1-mini |

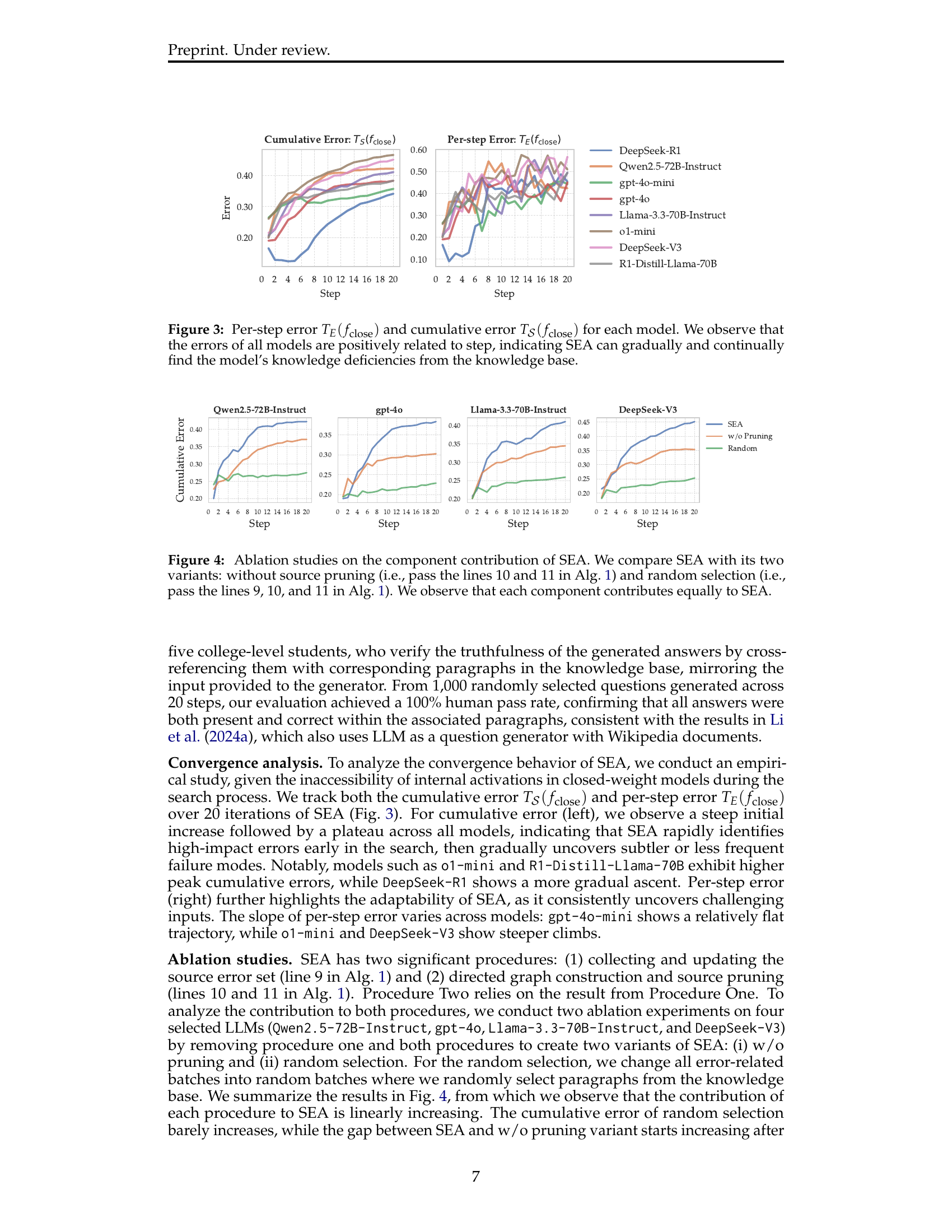

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the computational costs associated with running eight different large language models (LLMs) over 20,000 questions. The costs are categorized into question generation costs, inference costs (the cost of the model processing the questions), and the number of output tokens generated by each model. A key observation is the significant difference in cost between LLMs with reasoning capabilities (DeepSeek-R1, R1-Distill-Llama-70B, and o1-mini) and those without. Reasoning models show substantially higher costs, particularly in inference, highlighting the increased computational demands of their enhanced reasoning abilities.

read the caption

Table 2: Question generation cost, inference cost, and output tokens at inference time across 20 steps (results in Fig.3; 20,000 questions in total). We can see a significant gap between reasoning models (DeepSeek-R1, R1-Distill-Llama-70B, and o1-mini) and other non-reasoning models.

| (1) Challenging in Chronological Analysis |

| (2) Unfamiliar with Locational Details |

| (3) Issues in Pattern Recognition |

| (4) Inaccurate Data Synthesis |

| (5) Collaborative and Relational Patterns |

🔼 This table presents an example from the study that illustrates a case where a large language model (LLM) provides misinformation. The example focuses on a question about James B. Stump’s doctoral degree year. The correct year is 2000, but the LLM incorrectly states 1998. The table highlights the incorrect information using underlines for emphasis. This case demonstrates the types of knowledge deficiencies the research method aims to uncover and analyze.

read the caption

Table 3: Example 1 for query 4. The correct doctoral year is '2000', but the misinformation incorrectly states '1998'. The incorrect information has been highlighted using underlines.

| Qwen2.5-72B-Instruct |

| Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct |

| R1-Distill-Llama-70B |

🔼 This table presents an example of a question from the SEA method’s evaluation, demonstrating a case where the LLM (Large Language Model) produced misinformation. The question asked in which event a specific photographic series was included. The correct answer is ‘African Photography Encounters’, but the LLM incorrectly identified the event as the ‘2019 Whitney Biennial’. The table highlights the LLM’s incorrect response by underlining the erroneous information. This example illustrates the type of knowledge deficiencies SEA is designed to uncover.

read the caption

Table 4: Example 2 for query 4. The proper event is 'African Photography Encounters,' yet the misinformation erroneously identifies it as the '2019 Whitney Biennial'. The incorrect information has been highlighted using underlines.

| Health and fitness |

| Natural and physics science |

🔼 Table 5 presents an example from Query 4 of the paper’s experimental setup. It showcases a question about the artist and medium of the painting ‘Portrait of Tristan Tzara.’ The table contrasts the correct answer (Robert Delaunay, oil on cardboard) with an incorrect response generated by a language model (Marcel Janco, oil on canvas). The incorrect parts of the language model’s answer are underlined in the table to highlight the misinformation.

read the caption

Table 5: Example 3 for query 4. It shows that the true artist and medium are 'Robert Delaunay, oil on cardboard', while the misinformation wrongly lists 'Marcel Janco' and 'oil on canvas'. The incorrect information has been highlighted using underlines.

| (1) Challenges with Chronological and Historical Data |

| (2) Issues with Contextual and Performance-Related Information |

| (3) Inaccurate Interpretation of Patterns and Trends |

| (4) Over-reliance on Assumptions and Generalizations |

| (5) Difficulty with Contextual Associations and Identifications |

🔼 This table presents an example (Example 4) of a question about the venue that hosted the exhibition ‘Six Feet Under’ during 2007 and 2008. The correct answer is Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden. However, the language model incorrectly identified Kunstmuseum Bern as the venue. The table shows the original question, the correct answer, the modified question for improved clarity, and the incorrect answer given by the language model, highlighting the misinformation with underlines.

read the caption

Table 6: Example 4 for query 4. In Example 4, the accurate venue is 'Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden', but the misinformation mistakenly mentions 'Kunstmuseum Bern'. The incorrect information has been highlighted using underlines.

| \rowcolorgray!50 Model Cost | DeepSeek-R1 | R1-Distill-Llama-70B | o1-mini | DeepSeek-V3 | Llama-3.3-70B | Qwen2.5-72B | gpt-4o-mini | gpt-4o |

| Generation Cost (US $) | 28.163 | 28.660 | 31.094 | 30.208 | 29.776 | 29.542 | 28.243 | 32.897 |

| Inference Cost (US $) | 48.360 | 7.888 | 39.708 | 1.261 | 0.868 | 0.37 | 0.347 | 7.905 |

| Inference Output Tokens | 19,608,736 | 10,836,882 | 8,507,015 | 380,099 | 1,024,942 | 272,566 | 125,117 | 308,145 |

🔼 Table 7 presents an example related to Query 4 of the study, which investigates whether LLMs produce misinformation when encountering unknown knowledge. The table focuses on an instance where an LLM incorrectly identifies the venue of an art exhibition. Specifically, the original question asks for the venue of Clare Kenny’s ‘If I Was a Rich Girl’ exhibition in 2019. The correct answer is ‘Kunst Raum Riehen.’ However, the LLM incorrectly states that the exhibition was held at ‘VITRINE.’ The table highlights the LLM’s incorrect response in underlines for clarity.

read the caption

Table 7: Example 5 for query 4. Original testing process correctly names the venue as 'Kunst Raum Riehen', in contrast to the misinformation’s incorrect attribution to 'VITRINE'.The incorrect information has been highlighted using underlines.

Full paper#