TL;DR#

Estimating human & camera movement in the world coordinate system from a single camera is hard due to the lack of depth information. Existing methods fall short in dynamic scenes. This paper tackles the challenge by leveraging the relationship between the world, humans, and camera. It builds on two observations: camera-frame human pose estimation can recover depth, and human motions inherently provide spatial cues.

The paper introduces WHAC, a novel framework for estimating human pose, shape, and camera pose from monocular video. It also presents WHAC-A-Mole, a new dataset with accurate human and camera annotations & diverse motions. Experiments on benchmarks show WHAC’s effectiveness, outperforming existing methods and handling challenging scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This research introduces a novel method for accurate human and camera motion capture from monocular video, using a new dataset to facilitate future work. It addresses the challenge of scaleless estimation, offering a robust solution applicable in areas like AR/VR, sports analysis, and robotics.

Visual Insights#

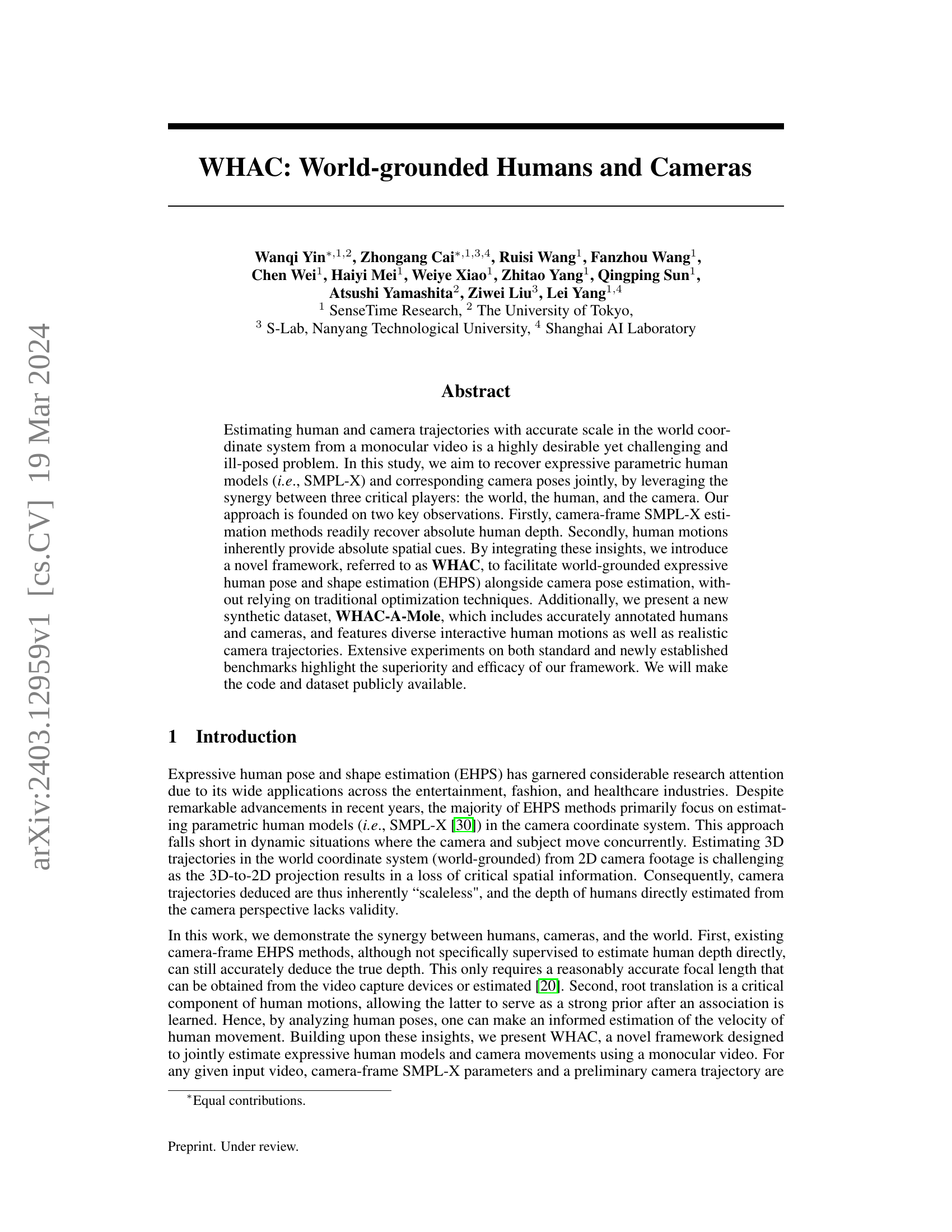

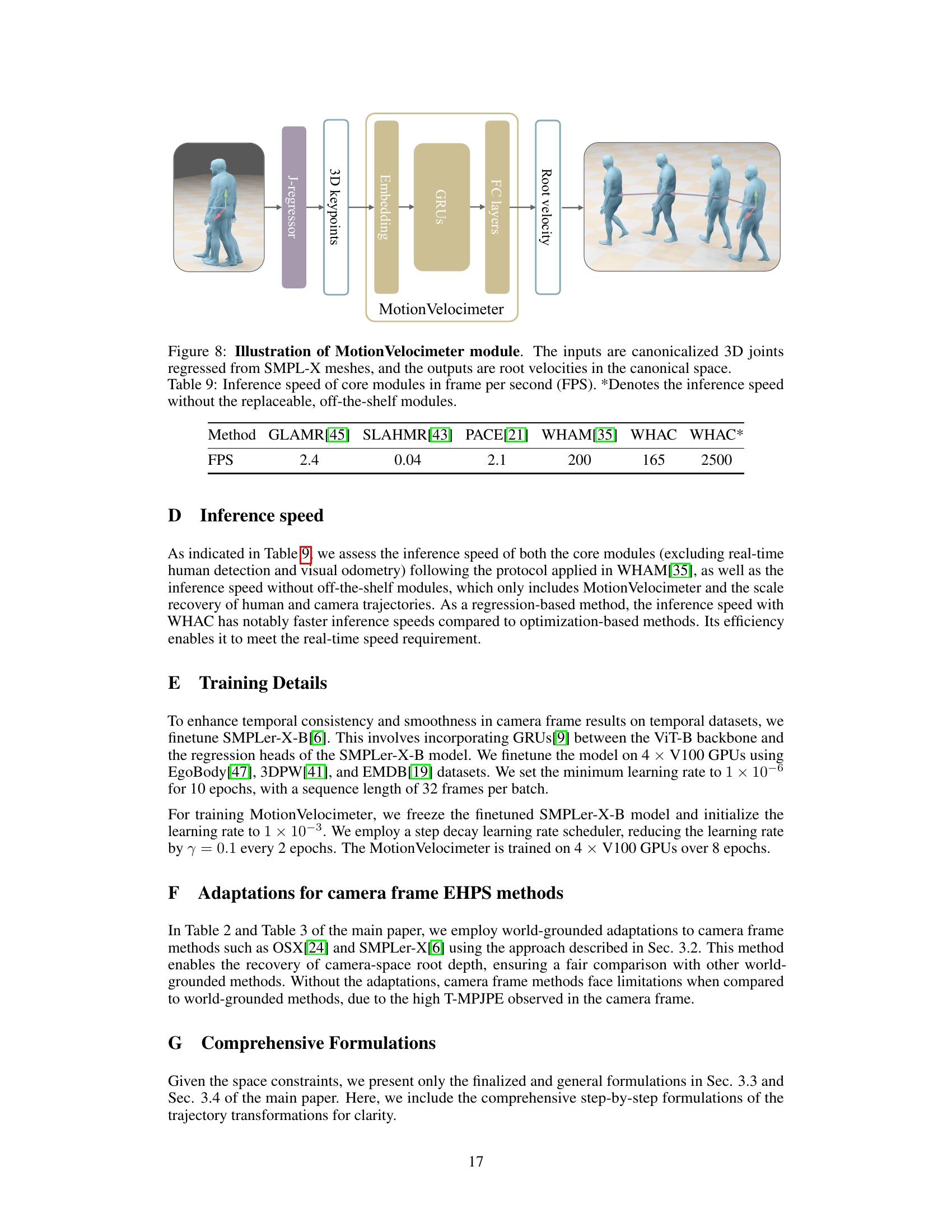

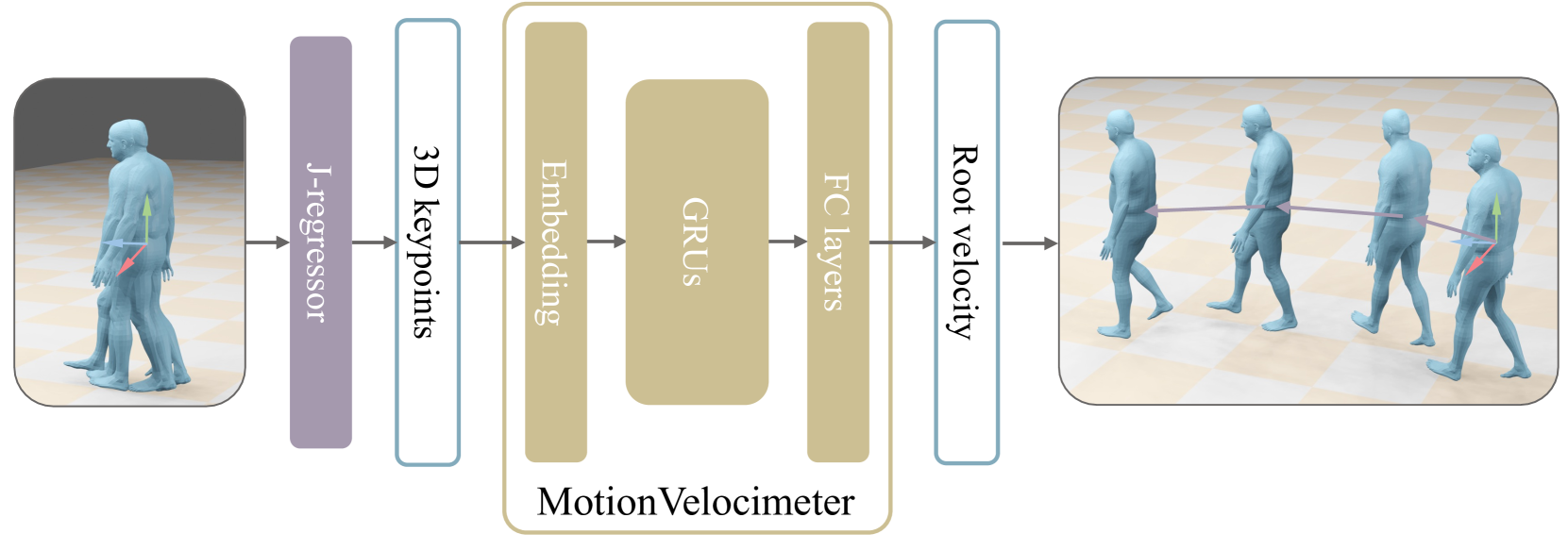

🔼 This figure illustrates the WHAC framework, which integrates three key components to estimate world-grounded human and camera trajectories. The first component is camera-frame SMPL-X estimation, which provides initial estimates of human pose and shape in the camera’s coordinate system. This is combined with visual odometry (VO), which estimates the camera’s trajectory in the world coordinate system, providing information about camera movement. Finally, the human-world component, the MotionVelocimeter, analyzes human movements to infer velocity and thus scale information, refining both camera and human trajectory estimates. The synergy of these three components allows WHAC to accurately estimate both camera and human trajectories with correct scale in the world.

read the caption

Figure 1: WHAC synergizes human-camera (camera-frame SMPL-X estimation), camera-world (visual odometry), and human-world (our proposed MotionVelocimeter) modeling for constructing world-grounded human and camera trajectories.

| Dataset | #Inst. | #Seq. | R/S | Multi. | Track. | Contact | HHI | Camera | Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DPW [41] | 74.6K | 60 | R | ✓ | ✓ | Moving | SMPL | ||

| RICH [16] | 476K | 141 | R | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Static* | SMPL |

| HCM [21] | 25 | S | ✓ | Moving | SMPL | ||||

| EMDB [19] | 109K | 81 | R | N.A. | N.A. | Moving | SMPL | ||

| EgoBody [47] | 175K | 125 | R | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Moving | SMPL-X | |

| BEDLAM [3] | 951K | 10.4K | S | ✓ | ✓ | Static | SMPL-X | ||

| SynBody [42] | 2.7M | 27K | S | ✓ | ✓ | Static | SMPL-X | ||

| WHAC-A-Mole | 1.46M | 2434 | S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Moving | SMPL-X |

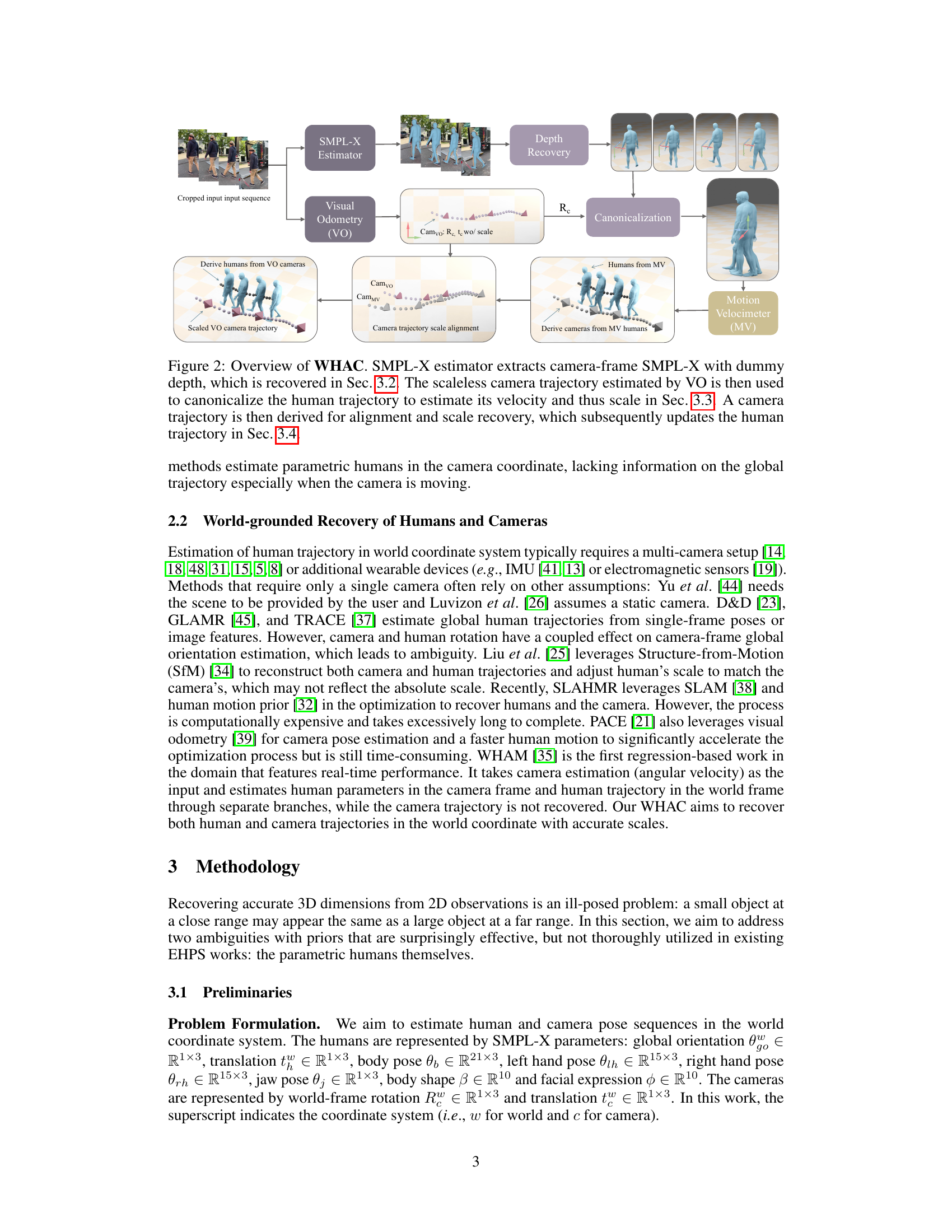

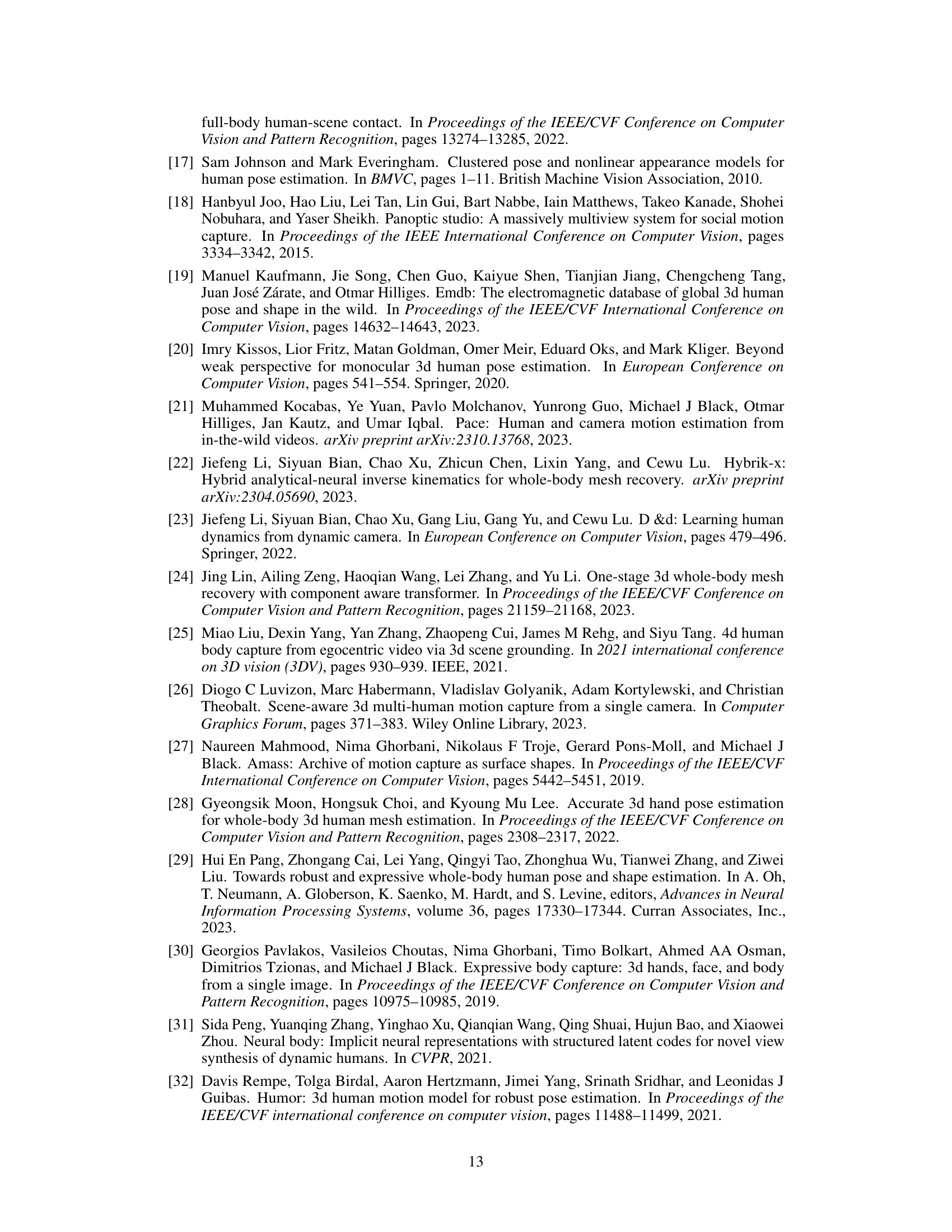

🔼 This table compares various existing human pose and shape estimation datasets. The columns describe the number of human instances, the number of video sequences, whether the data is real or synthetic, whether multiple people are present in each scene, the availability of track IDs to follow individual people across the video, the presence of human-human interactions, and whether the camera was static or moving during capture. It also indicates whether SMPL or SMPL-X human models are available for the data, and notes any specific characteristics of certain datasets such as the EgoSet dataset or datasets with very short video clips.

read the caption

Table 1: Dataset Comparison. #Inst.: number of human instances (crops). #Seq.: number of video sequences. R/S: Real or Synthetic. Multi.: multiperson scenes. Track.: track ID labels. HHI: human-human interaction motions. ††\dagger†: EgoSet. ‡‡\ddagger‡: unknown as the data is not released when this paper is written. ⋄⋄\diamond⋄: typically short (<100 frames) clips.

In-depth insights#

EHPS: Scaled VO#

While “EHPS: Scaled VO” isn’t explicitly in the paper, we can infer its meaning. EHPS (Expressive Human Pose and Shape estimation) combined with Scaled VO (Visual Odometry) suggests a system leveraging both human-centric understanding and scene geometry for enhanced 3D reconstruction. The core idea is to resolve the scale ambiguity inherent in monocular VO by incorporating constraints from EHPS. Traditional VO often struggles to determine the true scale of the environment. However, if we can accurately estimate the size and pose of humans within the scene (using EHPS), this information provides valuable metric scale cues. The system could work by first establishing camera motion with VO then refining this trajectory using EHPS outputs for the human in the scene to fix the scale. It should provide more accurate and robust 3D scene understanding, especially in dynamic environments where both the camera and humans are moving. This synergy between human-centric understanding and scene geometry promises to overcome the limitations of each individual method

WHAC Architecture#

While the paper doesn’t explicitly detail a ‘WHAC Architecture’ section, the core idea revolves around a synergistic framework. It leverages camera-frame human pose estimation (e.g., SMPL-X), visual odometry (VO) for camera motion, and a novel MotionVelocimeter (MV) module to estimate human motion velocities and recover absolute scale. The architecture likely involves a pipeline where initial camera-relative human poses are estimated, VO provides scaleless camera trajectory, MV infers human velocity, and a scale-alignment process refines both human and camera trajectories into a world-grounded coordinate system. This iterative refinement is central to the ‘architecture’, correcting scale and orientation ambiguities by blending visual and motion cues. The integration is not a mere concatenation of modules, but a carefully orchestrated feedback loop to improve estimation accuracy. The core is to refine the motion and trajectory using MV and VO.

WHAC-A-Mole Data#

While the actual heading may vary, the ‘WHAC-A-Mole’ data likely refers to a novel, synthetically generated dataset introduced in the paper. Given the context, it would be designed to address limitations in existing datasets for world-grounded human and camera pose estimation. This suggests it contains accurately annotated 3D human poses (possibly SMPL-X parameters), camera trajectories, and scene information within a global coordinate system. The dataset likely features diverse human motions, including interactions, and realistic camera movements, perhaps mimicking cinematic techniques. The aim is to facilitate training and evaluation of models that can jointly estimate human and camera trajectories with accurate scale in real-world coordinates, overcoming the scaleless nature of monocular video. WHAC-A-Mole probably involves a comprehensive set of animated subjects and moving viewpoints for robust training. This synthetic nature allows for controlled variation and precise annotation, which is often lacking in real-world datasets. The dataset is probably split into training and testing sets for robust evaluation.

Accurate Recovery#

Accurate recovery in the context of human pose estimation and camera trajectory estimation is a multifaceted challenge. Achieving high accuracy requires addressing ambiguities inherent in monocular vision, such as depth perception and scale determination. The synergy of combining camera-frame estimations, motion cues, and robust optimization techniques holds promise for recovering both human poses and camera trajectories with minimized error. Precise camera calibration is vital for accurate recovery for pose and camera parameters, and using external information can assist this process. Furthermore, developing novel metrics that adequately capture the nuanced aspects of accuracy becomes essential for evaluating improvements of the results. It needs to incorporate a balance of both human and camera recovery to ensure the estimation is good, and it is important to also take into account motion.

Societal Impact#

This work, while advancing human pose and camera trajectory estimation, carries potential societal impacts that warrant careful consideration. On the positive side, the technology could revolutionize fields like motion capture for film and gaming, enabling more realistic and accessible character animation. It could also contribute to advancements in healthcare, allowing for remote monitoring of patients’ movements and rehabilitation progress. Furthermore, its potential applications in human-robot interaction could lead to more intuitive and seamless collaborations. However, there is a risk of misuse for surveillance purposes. The ability to accurately track human movements in the world, even from monocular video, could be exploited for unwarranted monitoring and tracking of individuals, raising serious privacy concerns. It will also be used for unwanted surveillance as it recovers human trajectories in the world frame. To mitigate these risks, responsible development practices, including robust privacy safeguards, ethical guidelines, and transparent communication about the technology’s capabilities and limitations, are crucial. Open discussions involving researchers, policymakers, and the public are necessary to ensure that this technology is used in a way that benefits society while respecting individual rights and freedoms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure illustrates the WHAC framework’s workflow. It starts with an SMPL-X estimator that outputs camera-frame SMPL-X data with initially unknown depth. The depth is then recovered (Section 3.2). Simultaneously, visual odometry (VO) provides a scaleless camera trajectory. This trajectory is used to canonicalize (standardize) the human motion data, allowing for the estimation of human velocity and subsequently, scale (Section 3.3). A more refined camera trajectory is then derived, incorporating the scale information (Section 3.4). This refined camera trajectory is then used to further improve the accuracy of the human trajectory.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of WHAC. SMPL-X estimator extracts camera-frame SMPL-X with dummy depth, which is recovered in Sec. 3.2. The scaleless camera trajectory estimated by VO is then used to canonicalize the human trajectory to estimate its velocity and thus scale in Sec. 3.3. A camera trajectory is then derived for alignment and scale recovery, which subsequently updates the human trajectory in Sec. 3.4.

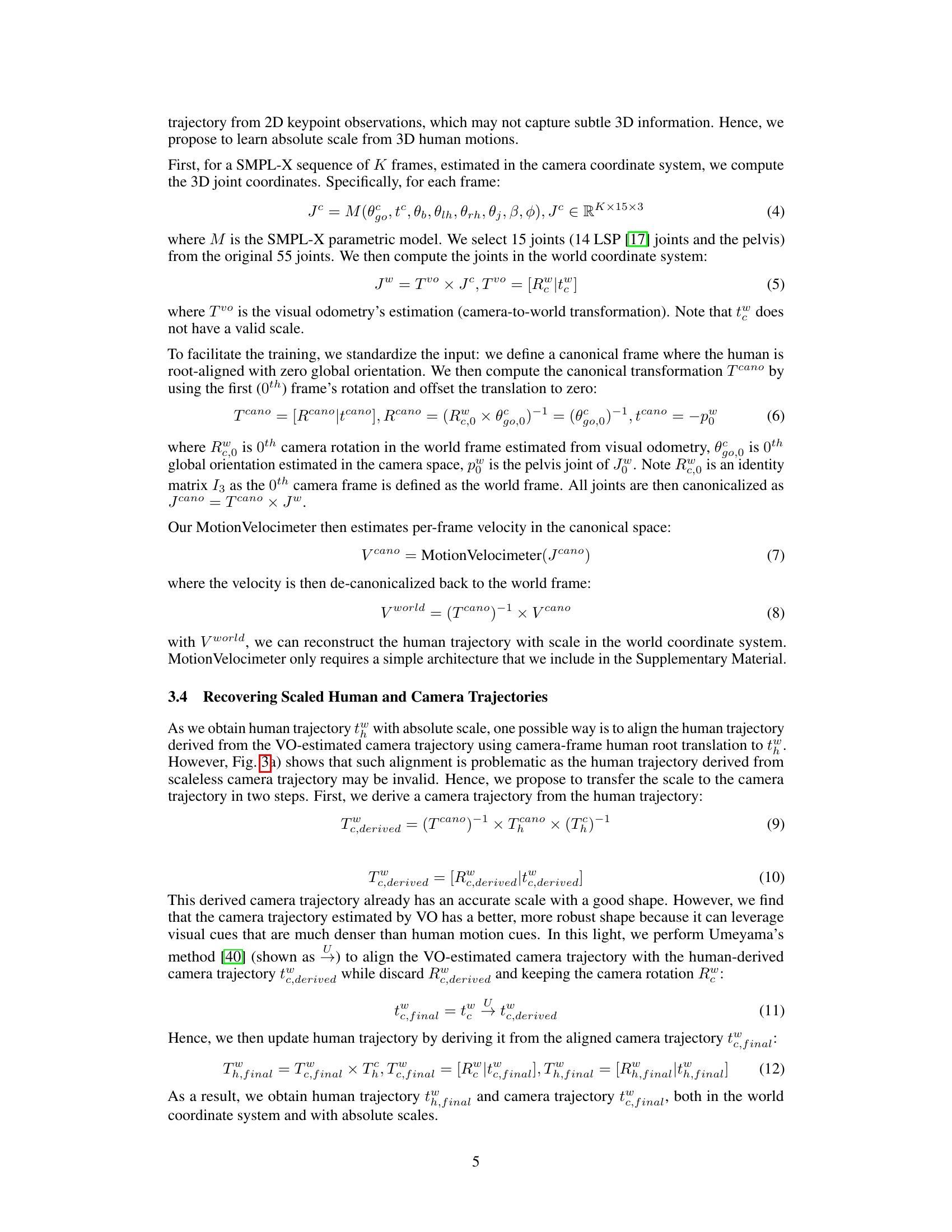

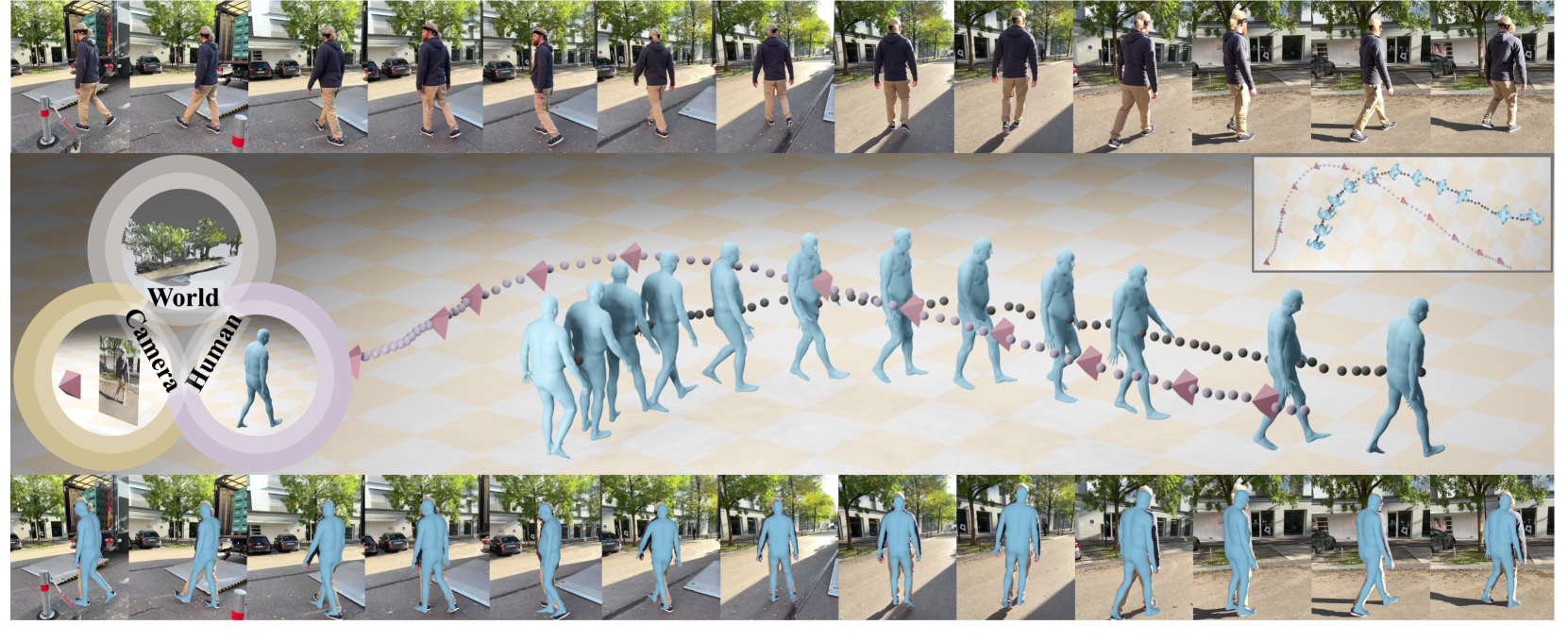

🔼 Figure 3 demonstrates the ambiguity in estimating 3D human trajectories from monocular video. Panel (a) shows that different camera trajectories (at different scales) will produce vastly different human trajectories, even if the camera-frame human root depth and translation are kept consistent. This highlights the challenge of scale estimation. Panel (b) illustrates that the same image could result from different combinations of focal length and human root depth, further emphasizing the ill-posed nature of the problem.

read the caption

Figure 3: a) Human trajectories H𝐻Hitalic_H derived from camera trajectories C𝐶Citalic_C of different scales can be vastly different in both shape and direction, despite that the same camera-frame human root depth dtsubscript𝑑𝑡d_{t}italic_d start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and translations thcsubscriptsuperscript𝑡𝑐ℎt^{c}_{h}italic_t start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_c end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_h end_POSTSUBSCRIPT are used. b) Different pairs of focal length f𝑓fitalic_f and tzsubscript𝑡𝑧t_{z}italic_t start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_z end_POSTSUBSCRIPT can correspond to the same image.

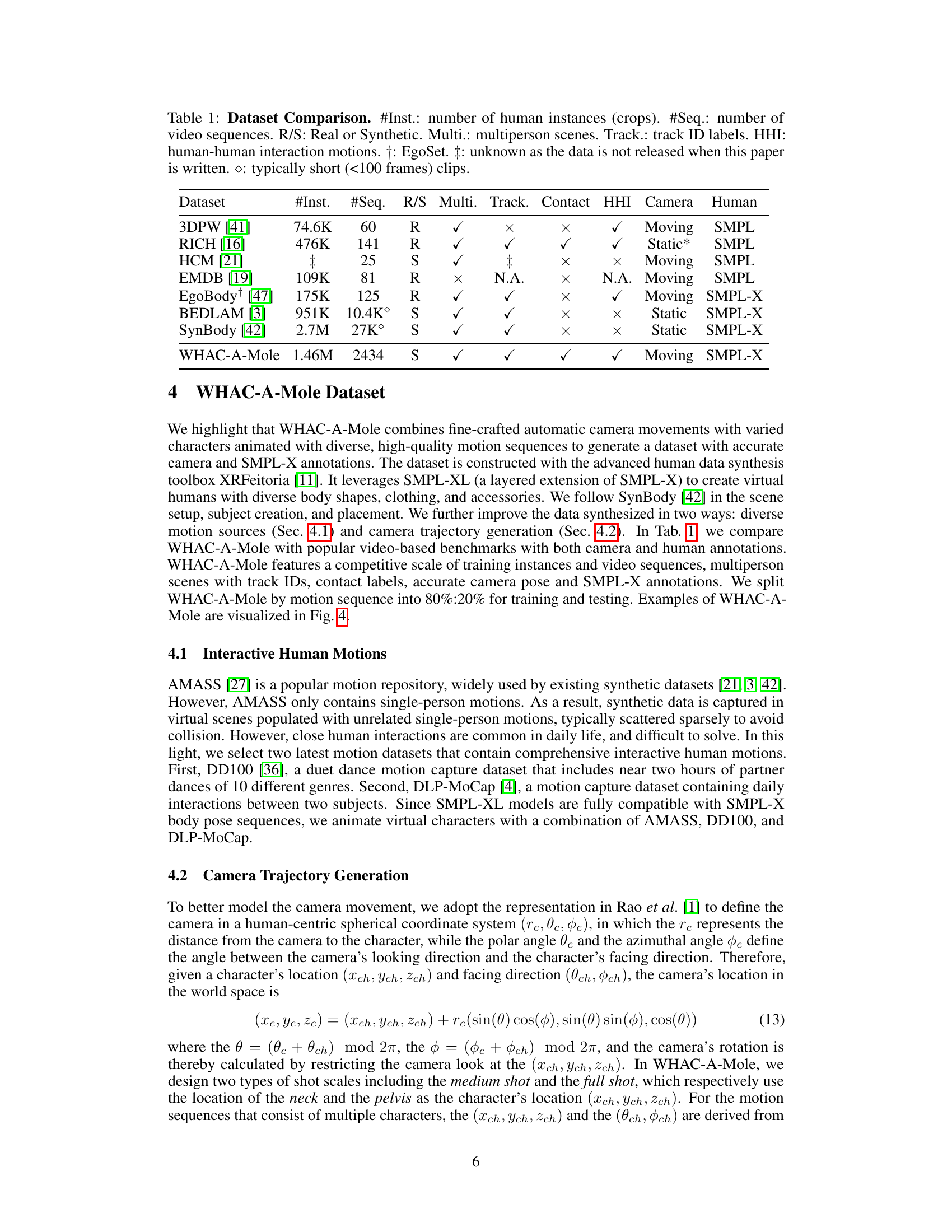

🔼 Figure 4 visualizes examples from the WHAC-A-Mole dataset. Each example shows three rows: the top row displays an overview of the scene with the camera trajectory highlighted, the second row shows a camera view from that trajectory, and the bottom row presents the same camera view with SMPL-X body annotations overlaid. The dataset’s motion sequences are from three sources: AMASS (a), DLP-MoCap (b-c), and DD100 (d-e).

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of WHAC-A-Mole sample sequences, animated with a) AMASS, b-c) DLP-MoCap, and d-e) DD100. In each sample, the first row depicts the overview (note the camera trajectory shown in bright rays), and the second and the third rows show the camera view and overlaid SMPL-X annotations.

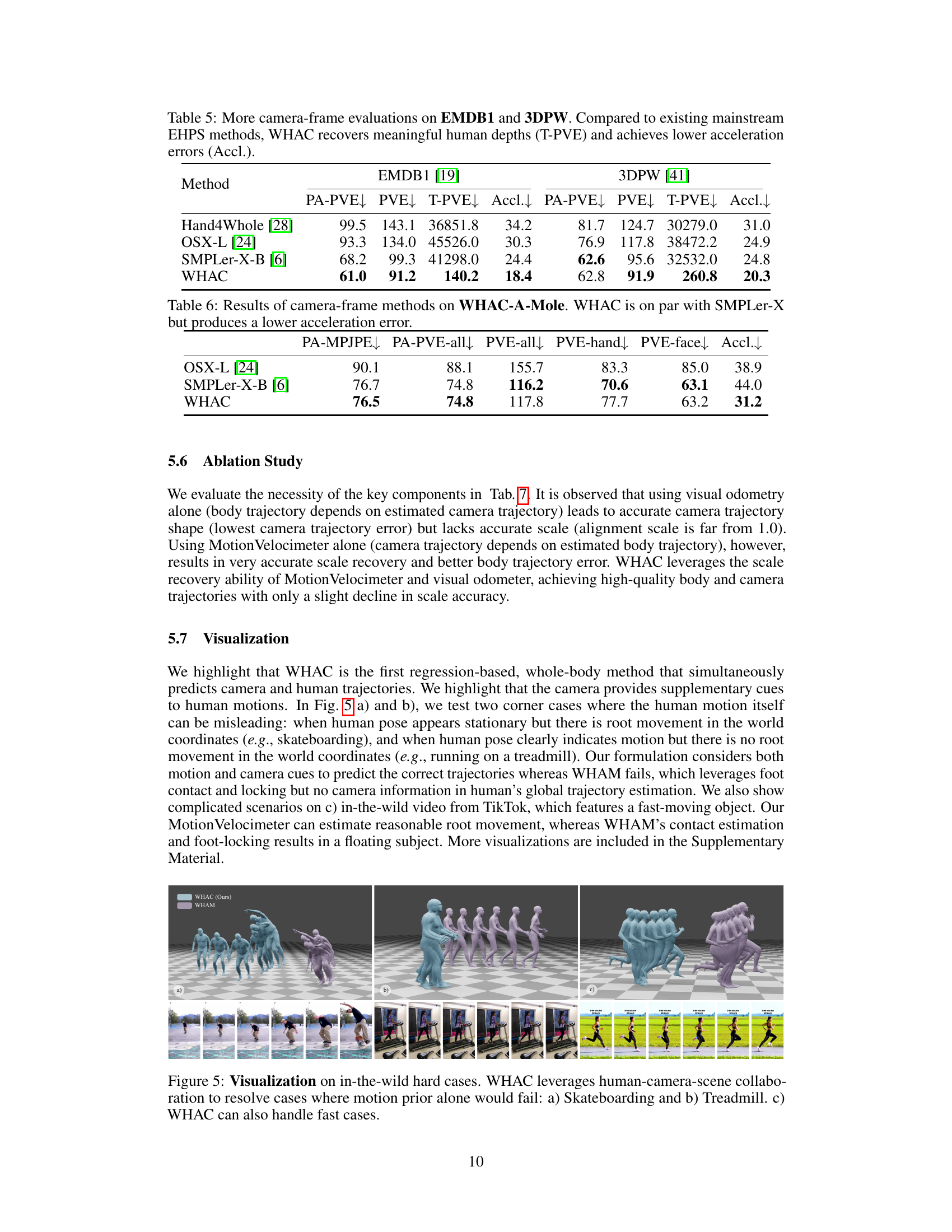

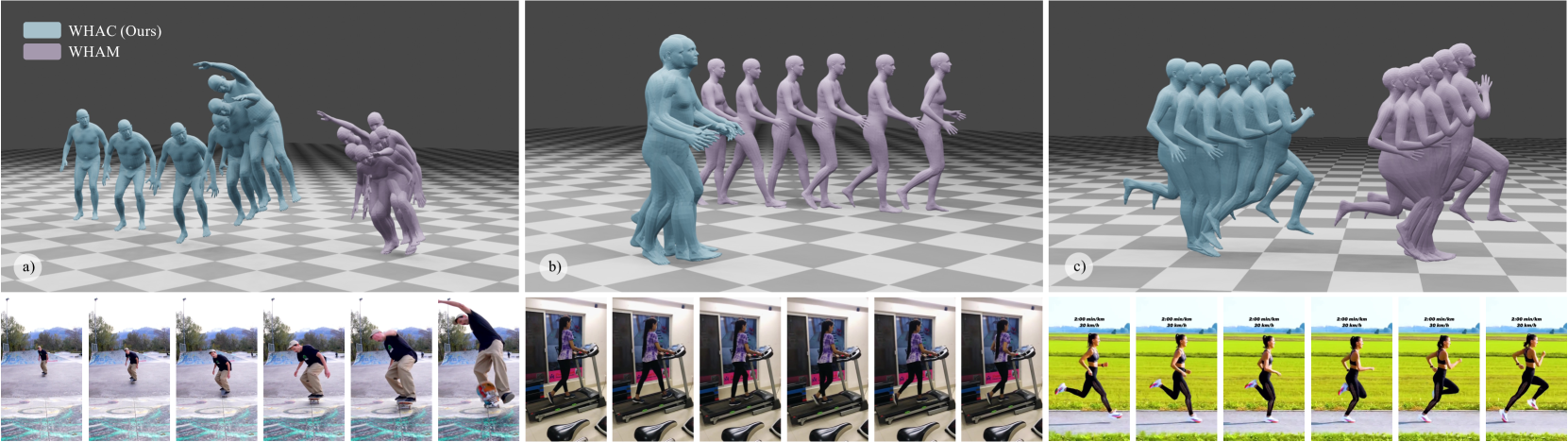

🔼 Figure 5 presents challenging scenarios where motion estimation alone might fail. It showcases WHAC’s ability to leverage information from human motion, camera movement, and scene context for improved accuracy. Specifically: (a) shows a skateboarding example, where the human may appear stationary in the camera frame, but is actually moving in the world; (b) shows a treadmill example where the human is moving, but the root translation in the world frame is minimal; and (c) demonstrates WHAC handling a fast-moving scene from a real-world video, again highlighting its ability to combine multiple sources of information.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualization on in-the-wild hard cases. WHAC leverages human-camera-scene collaboration to resolve cases where motion prior alone would fail: a) Skateboarding and b) Treadmill. c) WHAC can also handle fast cases.

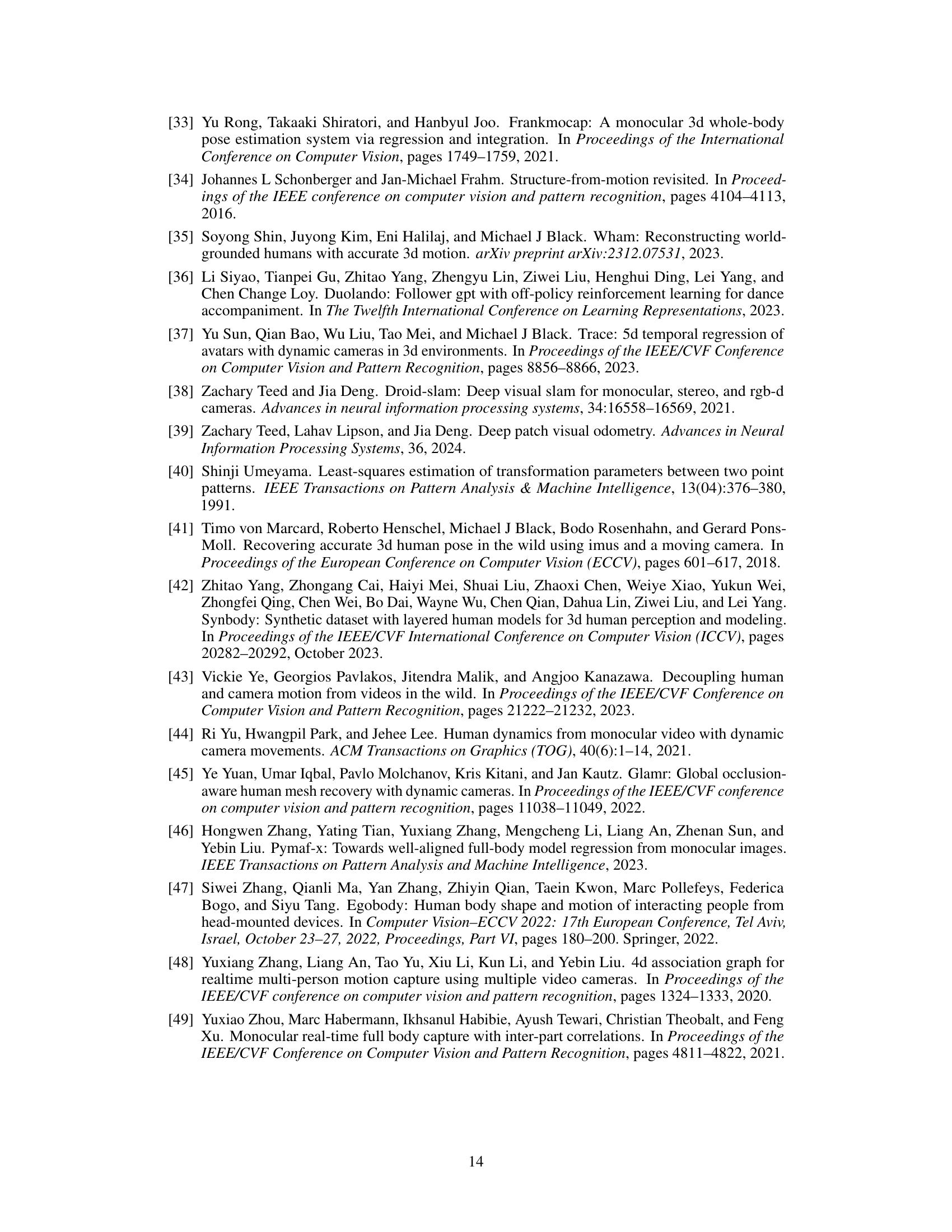

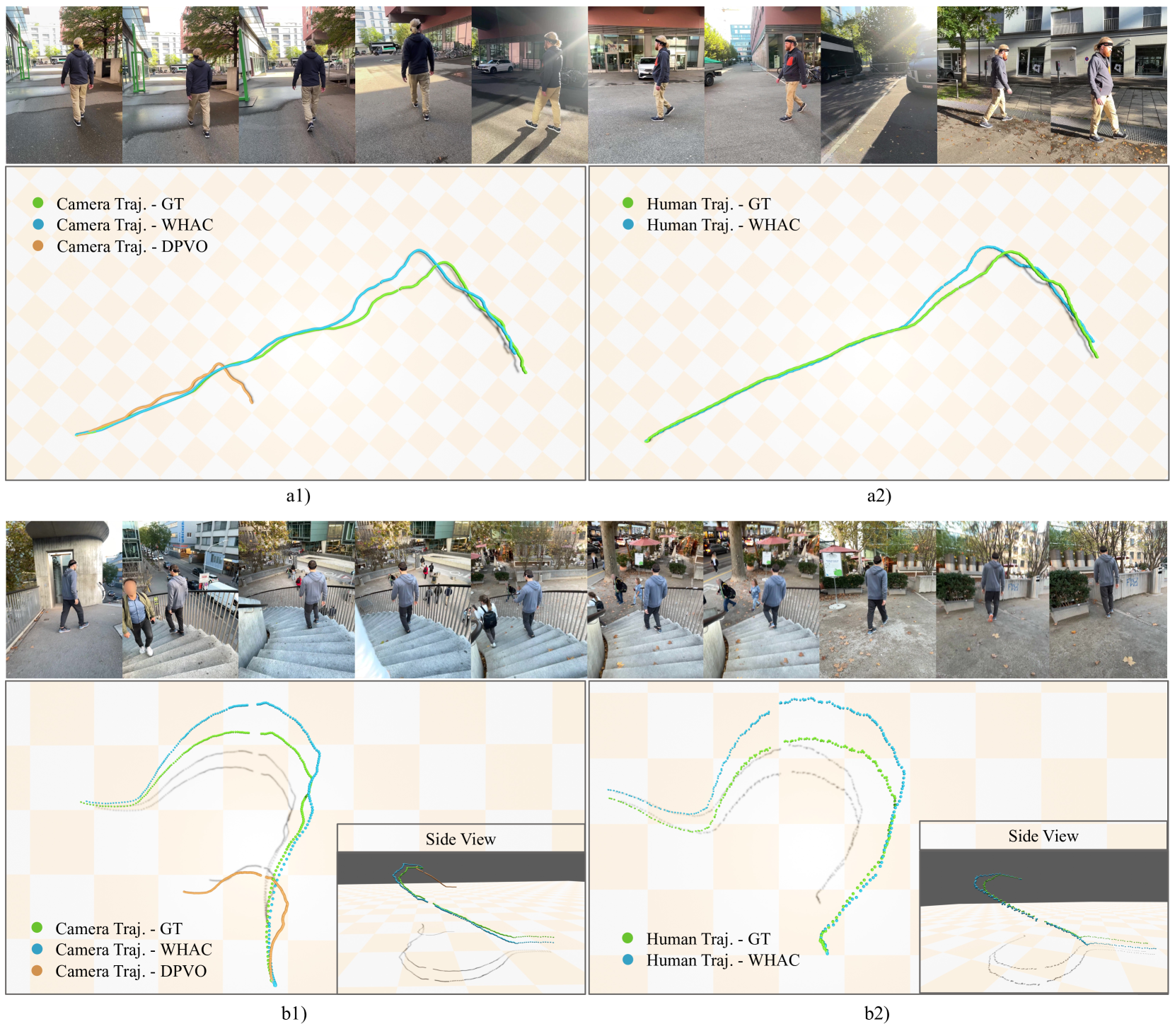

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of the proposed WHAC method on the EMDB dataset, focusing on world-space trajectory estimation. The top row (a1 and b1) shows camera trajectories, while the bottom row (a2 and b2) shows corresponding human trajectories. The plots clearly demonstrate WHAC’s ability to accurately recover both camera and human movements, including scale, in the 3D world coordinate system. The example in sequence ‘b’ highlights this capability, accurately capturing the downward motion of a human descending stairs. The grid lines in the plots represent a 2-meter spacing.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visualization of world space results on the EMDB dataset. a1) and b1) depict camera trajectories, while a2) and b2) illustrate human trajectories. Notably, in sequence b, the human is descending stairs, and WHAC effectively captures the global trajectory, indicating a downward direction besides recovering the absolute trajectory scale in the world space. The grid size in the plots is 2m.

🔼 Figure 7 visualizes the results of WHAC (World-grounded Humans and Cameras) on the WHAC-A-Mole dataset, demonstrating its ability to estimate human poses and shapes accurately in challenging scenarios. Each sample in the figure shows two rows: the top row displays the original video frames, while the bottom row overlays the estimated SMPL-X model on top of the video frames. The figure showcases several challenging cases: scenes with severe occlusions, intricate human interactions, and dynamic poses such as dancing, illustrating the robustness and accuracy of the WHAC method.

read the caption

Figure 7: Visualization of camera space results on WHAC-A-Mole dataset. Each sample comprises two rows: the first row displays the original input frames from the sequence, while the second row overlays the SMPL-X results. This visualization showcases WHAC’s performance on challenging scenes, including sequences with severe occlusions, intricate human interactions, and dynamic dancing poses.

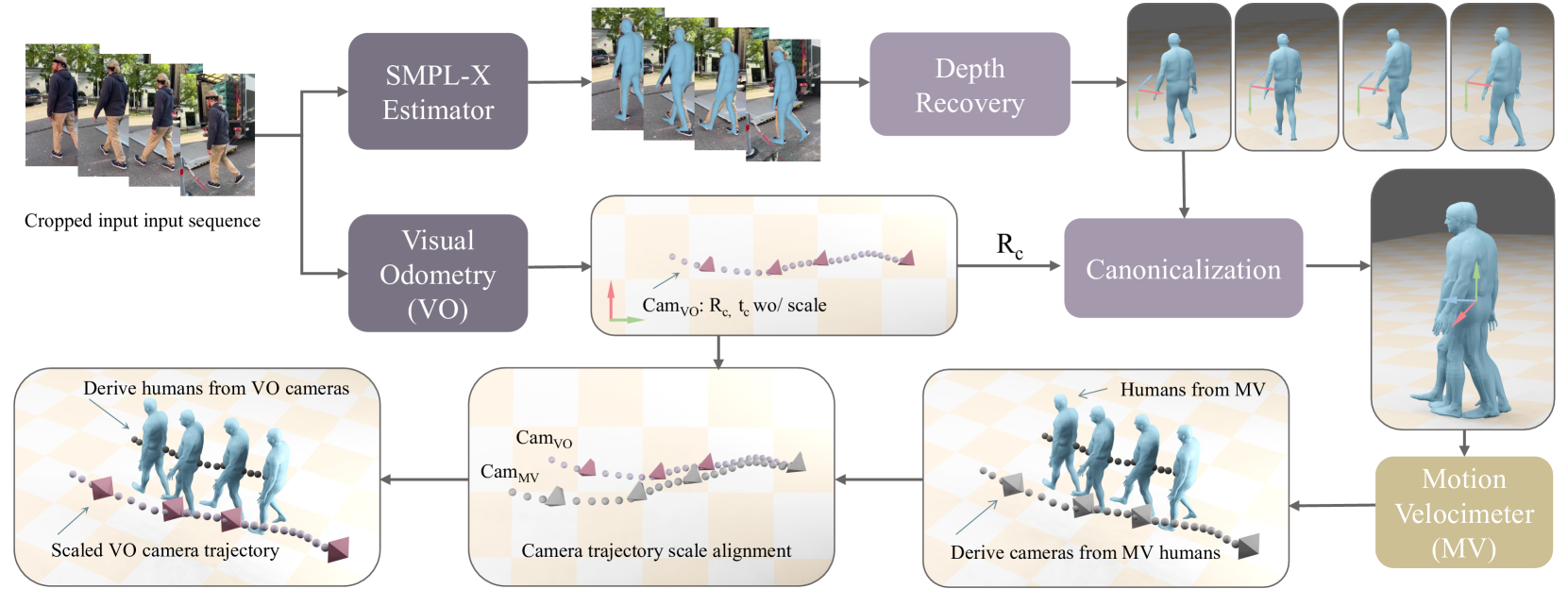

🔼 The MotionVelocimeter module takes as input 3D joints from SMPL-X meshes that have been canonicalized (aligned to a standard pose). It processes these joints to output root velocities, also in the canonical space. This means the module focuses on the speed and direction of the human’s root movement, relative to the starting point of the sequence. The use of canonicalized data simplifies the task and makes the velocity estimation more robust.

read the caption

Figure 8: Illustration of MotionVelocimeter module. The inputs are canonicalized 3D joints regressed from SMPL-X meshes, and the outputs are root velocities in the canonical space.

More on tables

| PA-MPJPE | W-MPJPE | WA-MPJPE | H-ATE | H-AS | C-ATE | C-AS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSX* [24] + DPVO [39] | 90.1 | 1036.1 | 390.7 | 180.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 7.3 |

| SMPLer-X-B* [6] + DPVO [39] | 76.7 | 842.3 | 335.4 | 138.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 7.3 |

| WHAC (GT Gyro) | 76.5 | 343.8 | 182.0 | 103.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| WHAC | 76.5 | 343.3 | 182.0 | 103.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

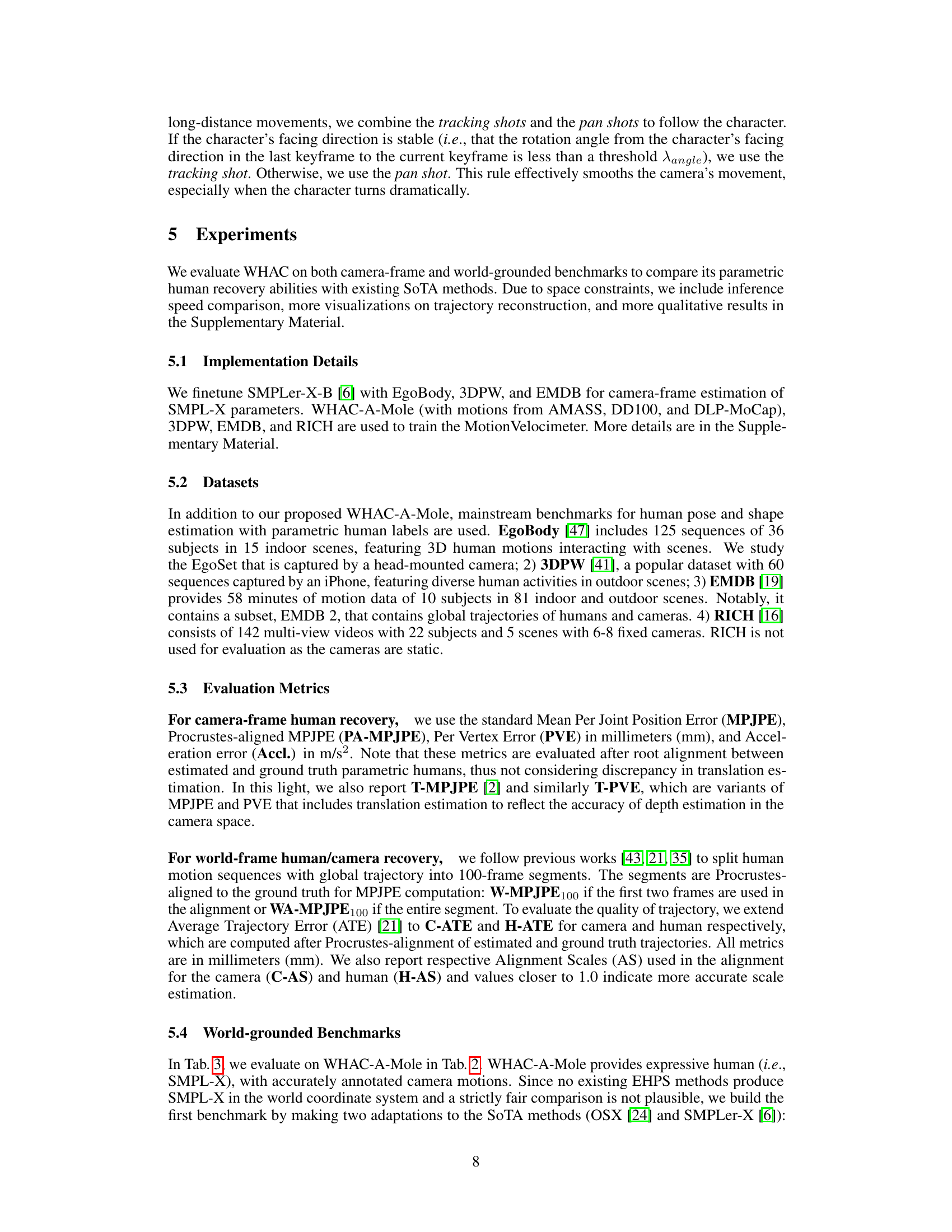

🔼 Table 2 presents a comparison of different methods’ performance on the WHAC-A-Mole dataset, focusing on world-frame evaluation metrics. The asterisk (*) indicates methods adapted for world-grounded evaluation. The metrics include PA-MPJPE (Procrustes-aligned mean per joint position error), W-MPJPE (world-frame MPJPE using the first two frames for alignment), WA-MPJPE (world-frame MPJPE using the entire sequence for alignment), H-ATE (human average trajectory error), H-AS (human alignment scale), C-ATE (camera average trajectory error), and C-AS (camera alignment scale). H-AS and C-AS values close to 1.0 represent better scale estimation accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: World-frame evaluation on WHAC-A-Mole. *: adapted to world-grounded evaluation. H-AS and C-AS: the closer to 1.0, the better.

| PA-MPJPE | W-MPJPE | WA-MPJPE | H-ATE | H-AS | C-ATE | C-AS | |

| GLAMR [45] | 56.0 | 756.1 | 286.2 | - | - | - | - |

| SLAHMR [43] | 61.5 | 807.4 | 336.9 | 207.8 | 1.9 | - | - |

| WHAM [35] (GT Gyro) | 41.9 | 436.4 | 165.9 | 83.2 | 1.5 | - | - |

| OSX-L* [24] + DPVO [39] | 99.9 | 1186.2 | 458.8 | 235.4 | 2.3 | 14.8 | 5.1 |

| SMPLer-X-B* [6] + DPVO [39] | 42.5 | 930.1 | 375.8 | 200.6 | 2.0 | 14.8 | 5.1 |

| WHAC (GT Gyro) | 39.4 | 392.5 | 143.1 | 75.8 | 1.1 | 14.8 | 1.5 |

| WHAC | 39.4 | 389.4 | 142.2 | 76.7 | 1.1 | 14.8 | 1.4 |

🔼 Table 3 presents a comparison of different methods for estimating human and camera trajectories in a world coordinate system, specifically using the EMDB2 dataset. The metrics used are PA-MPJPE (Procrustes-aligned Mean Per Joint Position Error), W-MPJPE (world-frame MPJPE), WA-MPJPE (world-aligned MPJPE), H-ATE (Human Average Trajectory Error), H-AS (Human Alignment Scale), C-ATE (Camera Average Trajectory Error), and C-AS (Camera Alignment Scale). The lower the values for MPJPE and ATE, the better the accuracy of the trajectory estimation. The closer H-AS and C-AS are to 1.0, the better the scale estimation. The asterisk (*) indicates that methods were adapted for world-grounded evaluation. This adaptation is crucial because these methods were originally designed for camera-centric estimations; adapting them ensures fair comparison with world-grounded methods.

read the caption

Table 3: World-frame evaluation on EMDB2. *: adapted to world-grounded evaluation. H-AS and C-AS: the closer to 1.0, the better.

| PA-MPJPE | PA-PVE-all | PVE-all | PVE-hand | PVE-face | Accl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLAMR [45] | 114.3 | - | - | - | - | 173.5 |

| SLAHMR [43] | 79.1 | - | - | - | - | 25.8 |

| Hand4Whole [28] | 71.0 | 59.8 | 127.6 | 48.0 | 41.2 | 27.2 |

| OSX-L [24] | 66.5 | 54.6 | 115.7 | 50.5 | 41.0 | 24.7 |

| SMPLer-X-B [6] | 47.1 | 40.7 | 72.7 | 43.7 | 32.4 | 18.9 |

| WHAC | 46.9 | 39.0 | 64.7 | 41.0 | 26.3 | 11.6 |

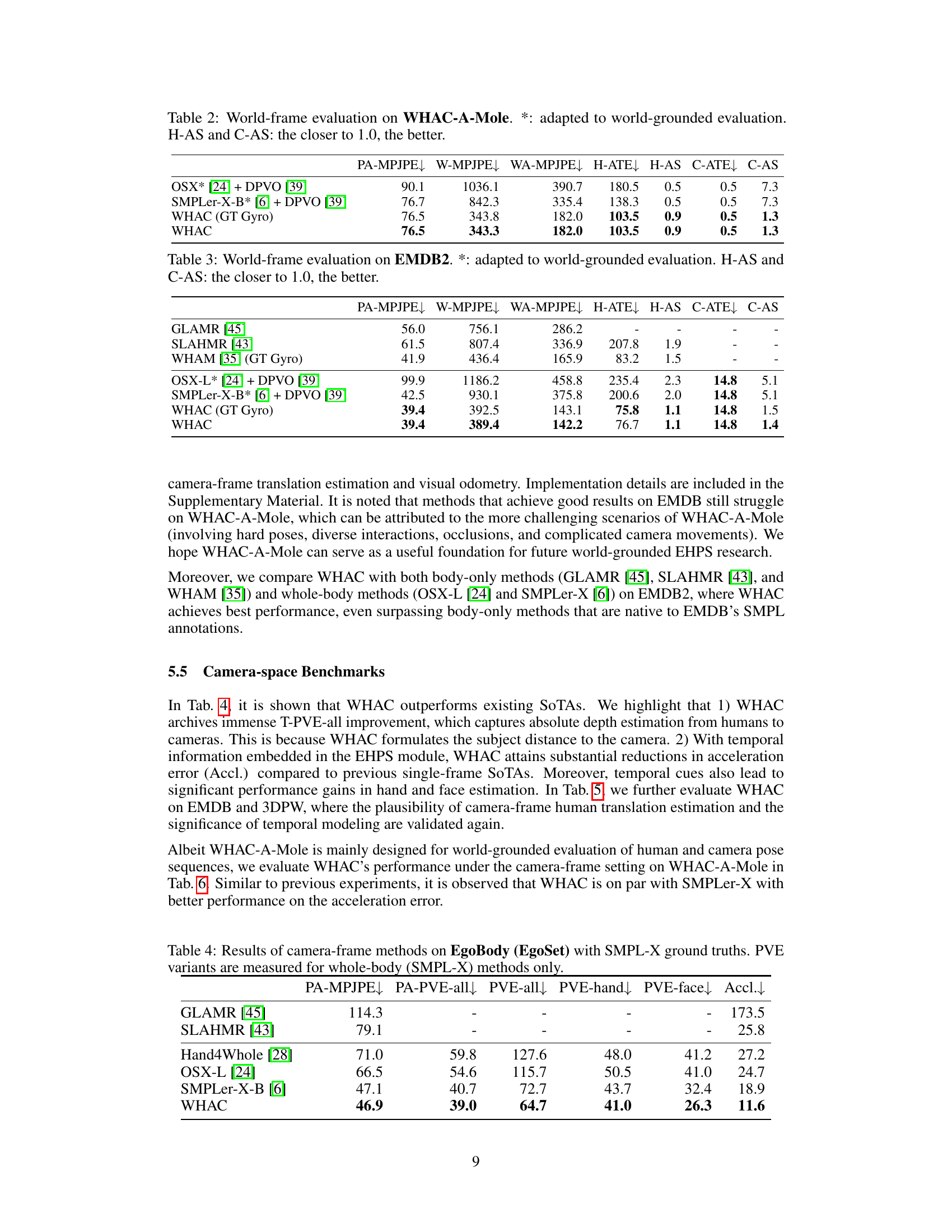

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various camera-frame methods for expressive human pose and shape estimation using the EgoBody (EgoSet) dataset. The evaluation metrics include PA-MPJPE, PA-PVE-all, PVE-all, PVE-hand, PVE-face, and Accl. PA-MPJPE measures the error in pose estimation after aligning the root joint, while PVE measures per-vertex error across different parts of the body (whole body, hands, and face). Accl. represents the acceleration error, reflecting the smoothness of the estimated motion. Only whole-body methods (those using SMPL-X models) are included in the PVE variants.

read the caption

Table 4: Results of camera-frame methods on EgoBody (EgoSet) with SMPL-X ground truths. PVE variants are measured for whole-body (SMPL-X) methods only.

| Method | EMDB1 [19] | 3DPW [41] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA-PVE | PVE | T-PVE | Accl. | PA-PVE | PVE | T-PVE | Accl. | |

| Hand4Whole [28] | 99.5 | 143.1 | 36851.8 | 34.2 | 81.7 | 124.7 | 30279.0 | 31.0 |

| OSX-L [24] | 93.3 | 134.0 | 45526.0 | 30.3 | 76.9 | 117.8 | 38472.2 | 24.9 |

| SMPLer-X-B [6] | 68.2 | 99.3 | 41298.0 | 24.4 | 62.6 | 95.6 | 32532.0 | 24.8 |

| WHAC | 61.0 | 91.2 | 140.2 | 18.4 | 62.8 | 91.9 | 260.8 | 20.3 |

🔼 Table 5 presents a comparison of camera-frame evaluation metrics for different expressive human pose and shape estimation (EHPS) methods on the EMDB1 and 3DPW datasets. The metrics evaluated include Procrustes-aligned Per Vertex Error (PA-PVE), Per Vertex Error (PVE), Translation-aware PVE (T-PVE), and Acceleration Error (Accl.). The results show that WHAC outperforms existing mainstream EHPS methods in terms of recovering meaningful human depth (indicated by T-PVE) and achieving lower acceleration errors (Accl).

read the caption

Table 5: More camera-frame evaluations on EMDB1 and 3DPW. Compared to existing mainstream EHPS methods, WHAC recovers meaningful human depths (T-PVE) and achieves lower acceleration errors (Accl.).

| PA-MPJPE | PA-PVE-all | PVE-all | PVE-hand | PVE-face | Accl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSX-L [24] | 90.1 | 88.1 | 155.7 | 83.3 | 85.0 | 38.9 |

| SMPLer-X-B [6] | 76.7 | 74.8 | 116.2 | 70.6 | 63.1 | 44.0 |

| WHAC | 76.5 | 74.8 | 117.8 | 77.7 | 63.2 | 31.2 |

🔼 Table 6 presents a comparison of the performance of several camera-frame methods, including WHAC and SMPLer-X, on the WHAC-A-Mole dataset. The evaluation metrics used are PA-MPJPE, PA-PVE-all, PVE-all, PVE-hand, PVE-face, and Accl. The results show that WHAC achieves comparable performance to SMPLer-X across all metrics, but demonstrates a notably lower acceleration error, indicating better accuracy in capturing the smoothness and realism of human motion.

read the caption

Table 6: Results of camera-frame methods on WHAC-A-Mole. WHAC is on par with SMPLer-X but produces a lower acceleration error.

| Method | WA-MPJPE | H-ATE | C-ATE | C-AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPVO | 376.0 | 177.8 | 14.8 | 5.10 |

| MV | 233.2 | 129.9 | 134.1 | 1.10 |

| MV + DPVO | 142.2 | 76.7 | 14.8 | 1.40 |

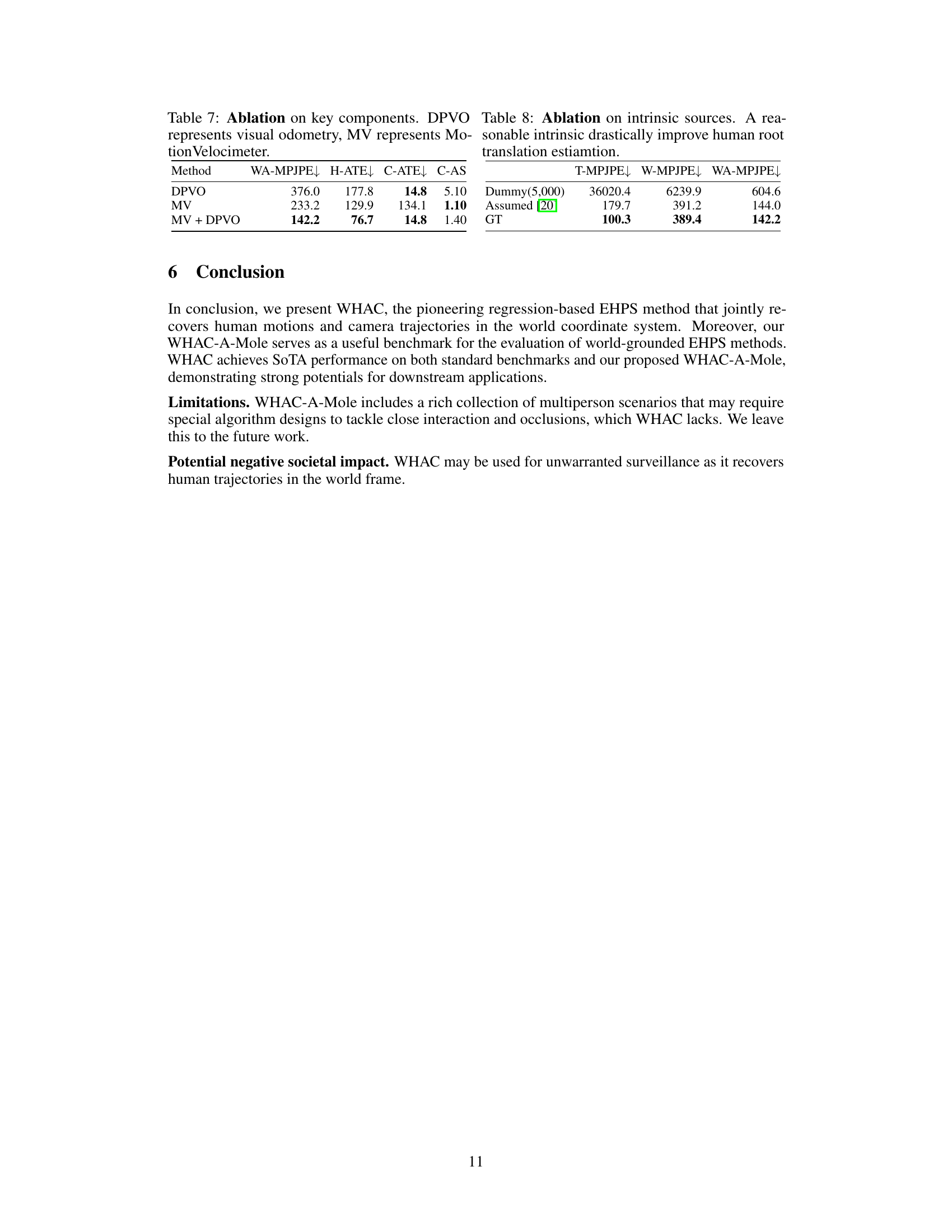

🔼 This ablation study analyzes the impact of key components (visual odometry and MotionVelocimeter) on the overall performance of the WHAC model. It assesses the effect of using visual odometry alone (DPVO), MotionVelocimeter alone (MV), and both components combined (MV + DPVO) on metrics such as weighted mean per joint position error (WA-MPJPE), human trajectory error (H-ATE), camera trajectory error (C-ATE), and camera scale accuracy (C-AS). The results demonstrate how the integration of both components enhances model performance, achieving improved accuracy in both human and camera trajectory estimation.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation on key components. DPVO represents visual odometry, MV represents MotionVelocimeter.

| T-MPJPE | W-MPJPE | WA-MPJPE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dummy(5,000) | 36020.4 | 6239.9 | 604.6 |

| Assumed [20] | 179.7 | 391.2 | 144.0 |

| GT | 100.3 | 389.4 | 142.2 |

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of using different focal length values on the accuracy of human root translation estimation. The table compares results using a dummy focal length (5000), a focal length estimated from image resolution, and ground truth focal length. The results demonstrate that using a reasonable estimate for the intrinsic parameter (focal length) significantly improves the accuracy of human root translation estimation.

read the caption

Table 8: Ablation on intrinsic sources. A reasonable intrinsic drastically improve human root translation estiamtion.

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of different intrinsic parameters (focal length) on the accuracy of human root translation estimation. The study compares the performance using a dummy focal length (5000), a focal length estimated from the image diagonal, and ground truth focal length. The results demonstrate that using a reasonable estimate of the focal length significantly improves the accuracy of the model.

read the caption

Table 8: Ablation on intrinsic sources. A reasonable intrinsic drastically improve human root translation estiamtion.

Full paper#