↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Lossy compression usually assumes the reconstruction distribution matches the source. This paper tackles the challenge when this assumption fails, a common issue in scenarios like joint compression and retrieval where processing might alter the distribution. Existing methods struggle in these situations, and simply constraining the code length isn’t enough to prevent decoder collapse.

The proposed Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B) integrates a bottleneck to control stochasticity and ensures the output follows a specific distribution. It’s broken down into two solvable problems: Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) for the encoder and MEC for the decoder. Experiments on Markov Coding Games showcase its effectiveness compared to standard compression, demonstrating a flexible balance between reward and reconstruction accuracy under various compression rates.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel lossy compression framework that is particularly relevant for applications with distributional shifts, such as joint compression and retrieval. It offers theoretical insights and a practical algorithm, advancing the field of minimum entropy coupling and opening avenues for research in Markov decision processes and rate-limited communication scenarios.

Visual Insights#

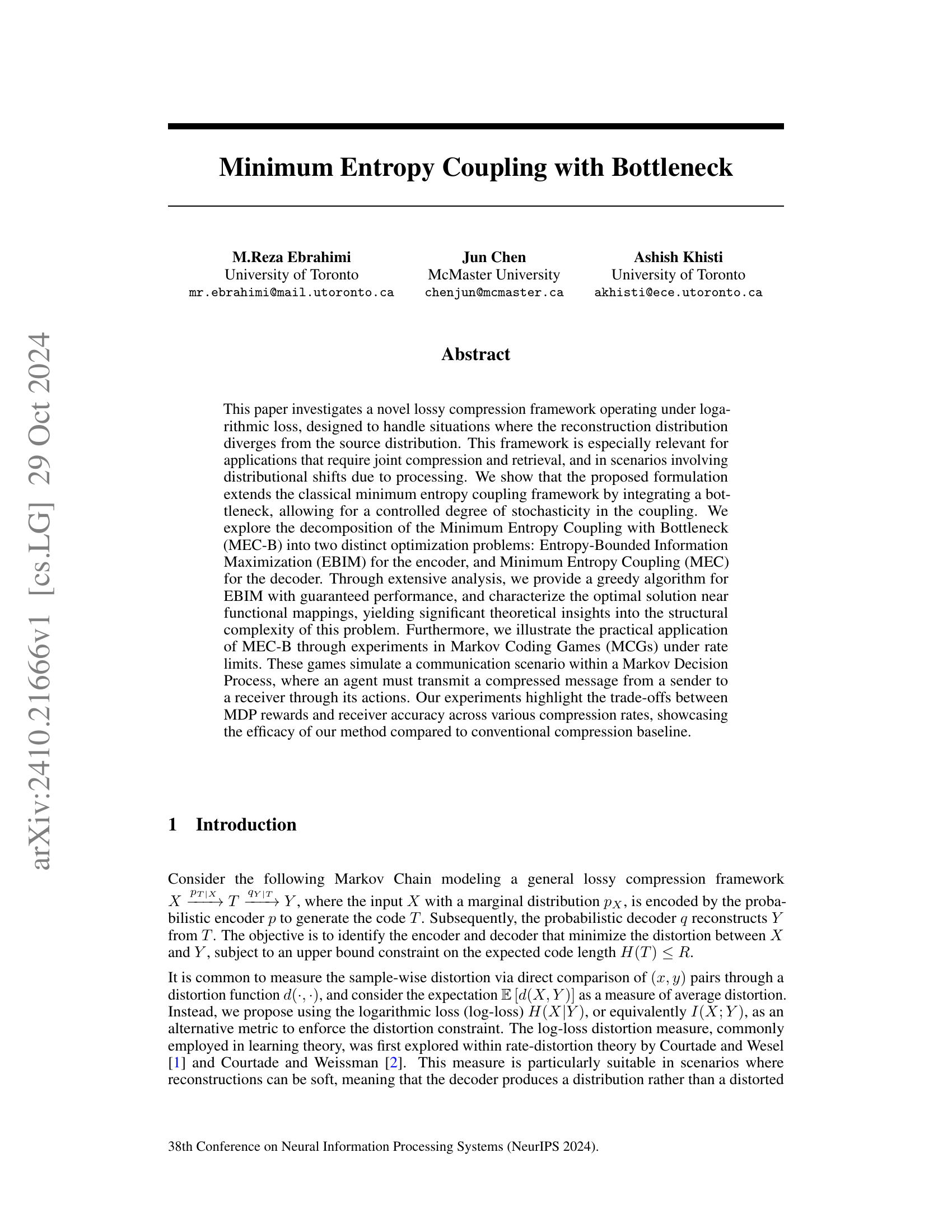

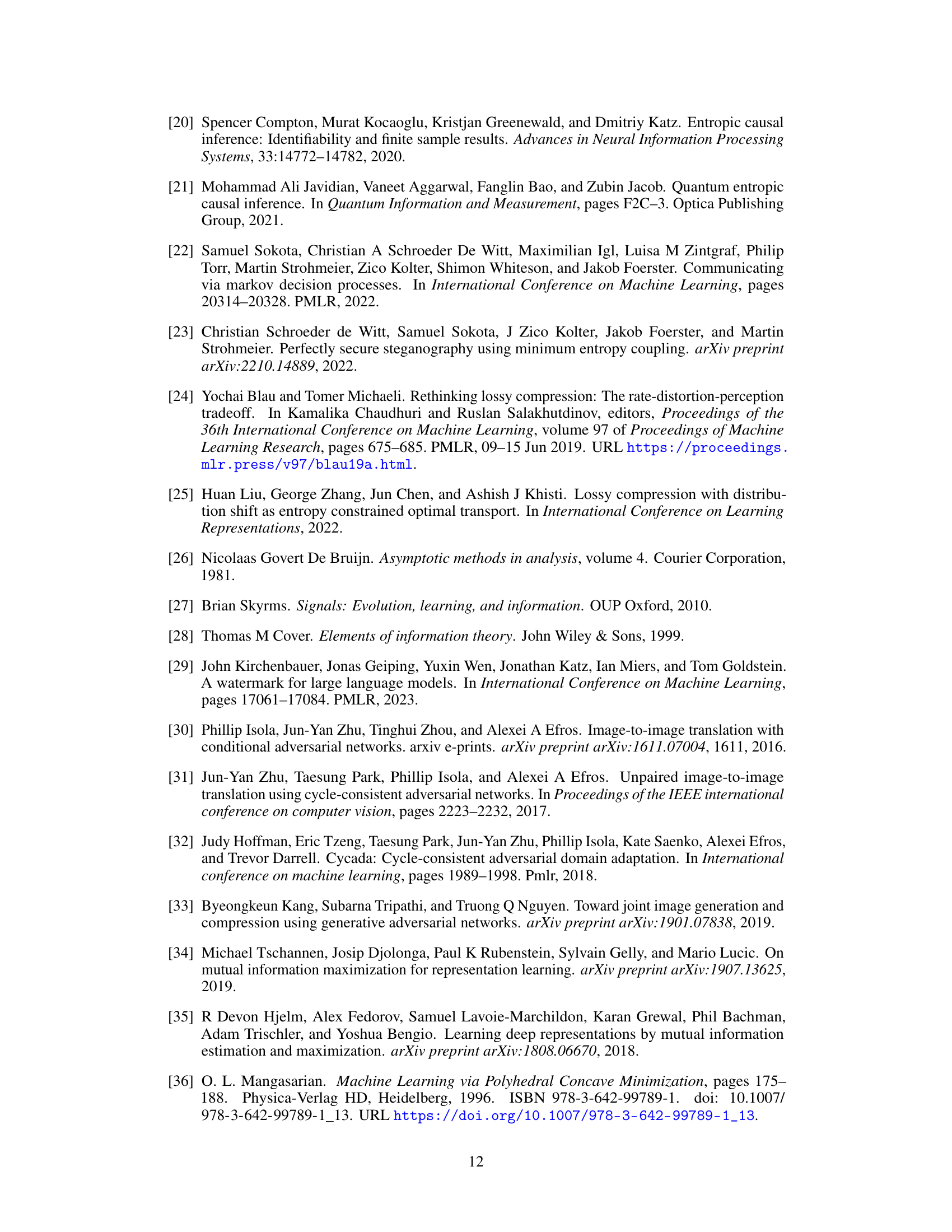

🔼 This figure illustrates Theorem 3, which describes how to find optimal couplings in the neighborhood of a deterministic mapping. It shows how, starting from a deterministic mapping represented by the matrix

p<sub>XT</sub>, one can obtain optimal solutions for slightly higher (R<sub>g</sub> + ε) and lower (R<sub>g</sub> - ε) entropy rates by carefully adjusting the probabilities in the matrix. Specifically, it demonstrates the two probability mass transformations described in Theorem 3 for increasing and decreasing the rate. The transformations involve shifting a small amount of probability mass to a column that either has zero probability (R<sub>g</sub> + ε) or to a column with the highest sum (R<sub>g</sub> - ε). The resulting changes in mutual information (I(X;T)) are also depicted.read the caption

Figure 1: An example for Theorem 3.

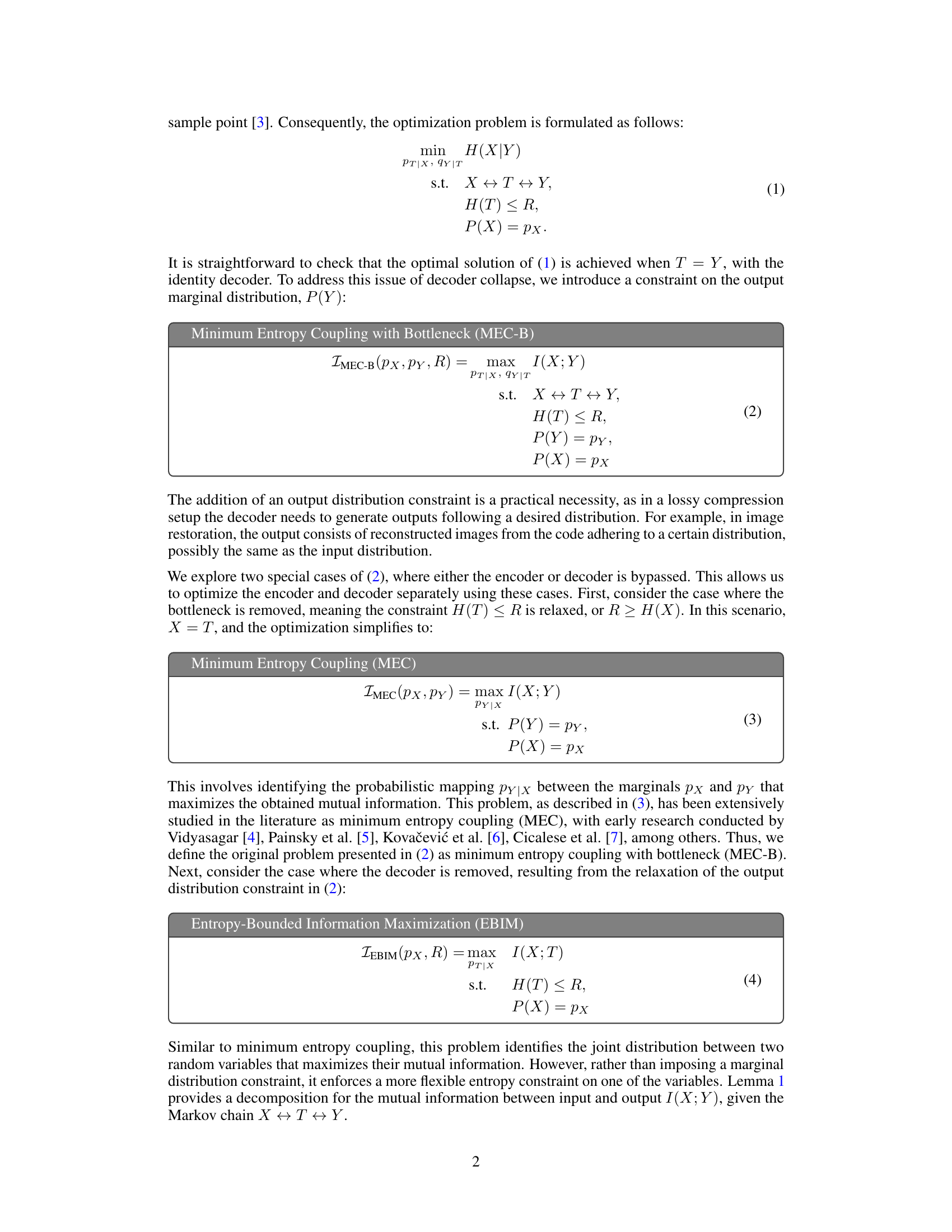

| Name | Entropy |

|---|---|

| Independent Joint | 5.443 ± 0.101 |

| SLA | 3.225 ± 0.141 |

| Max-Seeking Greedy | 2.946 ± 0.064 |

| Zero-Seeking Greedy | 2.937 ± 0.058 |

🔼 This table presents the results of a computational experiment comparing three different algorithms for calculating the minimum entropy coupling of 100 pairs of randomly generated marginal distributions. The algorithms compared are: Independent Joint (where the joint distribution is generated independently from the marginals), Successive Linearization Algorithm (SLA), Max-Seeking Greedy, and Zero-Seeking Greedy. For each algorithm, the average achieved joint entropy across the 100 simulation runs is reported along with its standard deviation.

read the caption

Table 1: Minimum Entropy Coupling: average achieved joint entropy of 100 simulations of marginal distributions.

In-depth insights#

MEC-B Framework#

The Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B) framework tackles lossy compression where the reconstruction distribution may diverge from the source. It extends the classical minimum entropy coupling by introducing a bottleneck, controlling stochasticity in the coupling process. MEC-B decomposes into two problems: Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) for the encoder, and Minimum Entropy Coupling (MEC) for the decoder. This decomposition allows for separate optimization, leading to theoretical insights into structural complexity and practical applications, such as rate-limited Markov Coding Games. The framework’s strength lies in handling distributional shifts often encountered in applications requiring joint compression and retrieval, thereby offering a more robust and flexible approach to lossy compression compared to traditional methods.

EBIM Algorithm#

The Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) algorithm tackles the challenge of finding the optimal joint distribution between two random variables, X and T, while constraining the entropy of T. The algorithm’s core innovation lies in its greedy approach, efficiently navigating a vast search space of deterministic mappings. It strategically merges columns of the joint probability matrix, guided by mutual information maximization and the imposed entropy constraint, guaranteeing a performance gap from the optimal solution, bounded by the binary entropy of the second largest element in X’s marginal distribution. This provides a computationally efficient solution, particularly significant when dealing with large alphabet sizes where brute-force methods are infeasible. Further refinements leverage this greedy solution as a starting point, subsequently exploring optimal mappings in its close vicinity, effectively bridging the gap between deterministic mappings and optimal, non-deterministic solutions. This two-pronged strategy combines computational efficiency with theoretical insights into the solution’s structure, making EBIM a powerful tool for scenarios demanding controlled stochasticity in information coupling.

Markov Game Tests#

The research paper investigates a novel lossy compression framework, Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B), particularly effective when reconstruction and source distributions diverge. Markov Coding Games (MCGs) are employed to showcase MEC-B’s practical application under rate constraints, simulating communication scenarios within a Markov Decision Process. The experiments highlight the trade-offs between MDP rewards and receiver accuracy at various compression rates. Results demonstrate the effectiveness of MEC-B in balancing these competing objectives, outperforming traditional compression baselines. The efficacy is shown by the trade-off between MDP rewards and receiver accuracy across different compression rates. The MEC-B framework’s adaptability to handle distributional shifts makes it valuable for applications such as joint compression and retrieval, where data processing induces such shifts.

Image Restoration#

The research explores unsupervised image restoration using a novel lossy compression framework, Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B). This framework leverages the Variational Information Maximization approach to maximize a lower bound on mutual information between low-resolution input and high-resolution output images. The approach cleverly incorporates an adversarial loss to enforce the desired output distribution, effectively handling unpaired datasets. The encoder is deterministic, producing a quantized code, while a stochastic generator accounts for noise, enabling the decoder to reconstruct the upscaled image. Experimental results on MNIST and SVHN datasets demonstrate successful upscaling, although color inconsistencies highlight the inherent limitations of relying solely on mutual information, which is invariant under certain transformations such as color rotations.

Future Extensions#

The paper’s ‘Future Extensions’ section suggests several promising research directions. Quantifying the gap between separate encoder/decoder optimization and a joint optimal solution is crucial for understanding MEC-B’s full potential. Fine-grained control over entropy spread in coupling would improve the method’s flexibility and applicability to diverse applications. Extending the framework to continuous cases is important to design neural network architectures based on MEC-B, potentially impacting areas like image translation, joint compression/upscaling, and InfoMax methods. Finally, exploring the intersection of EBIM with state-of-the-art AI applications, like watermarking language models, is highlighted as a key opportunity for future work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

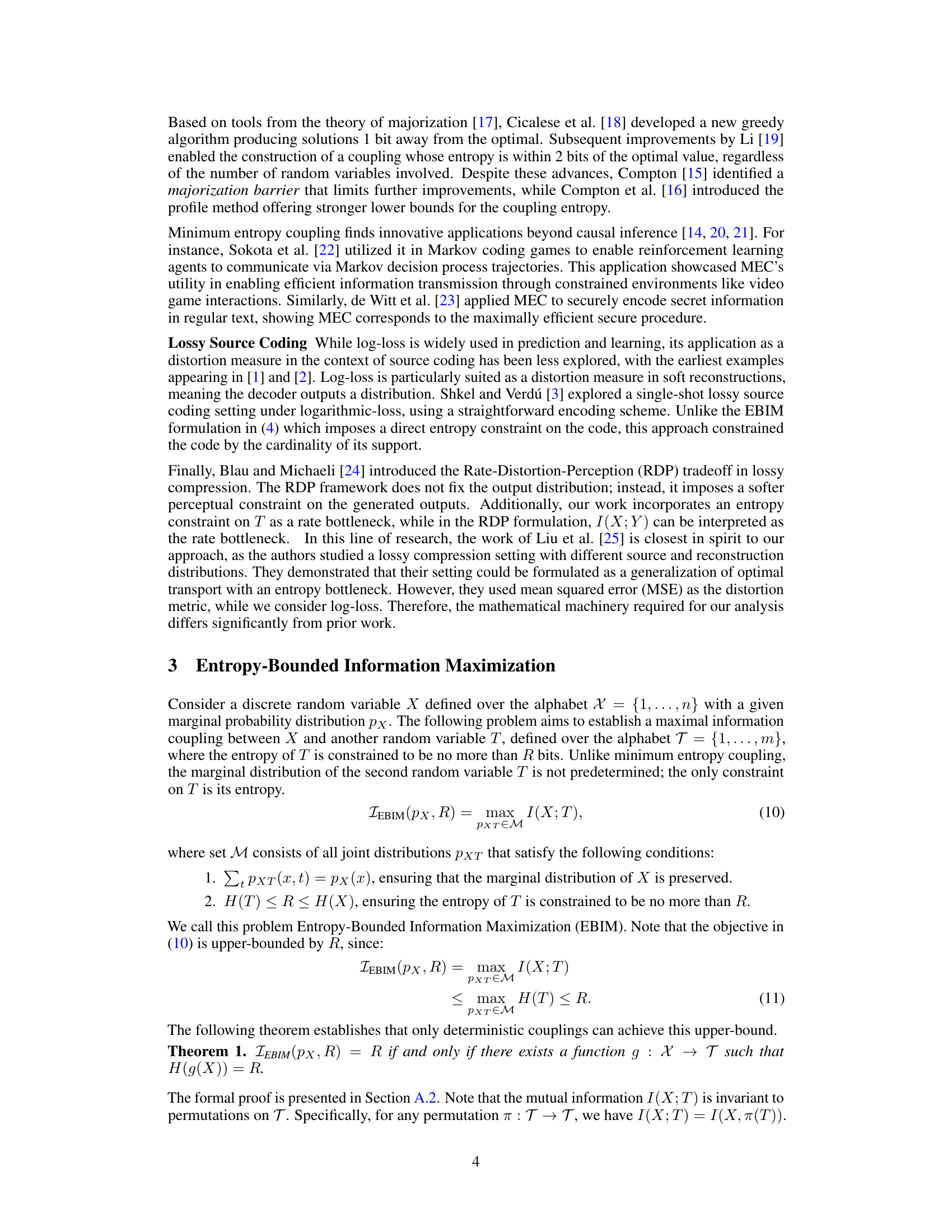

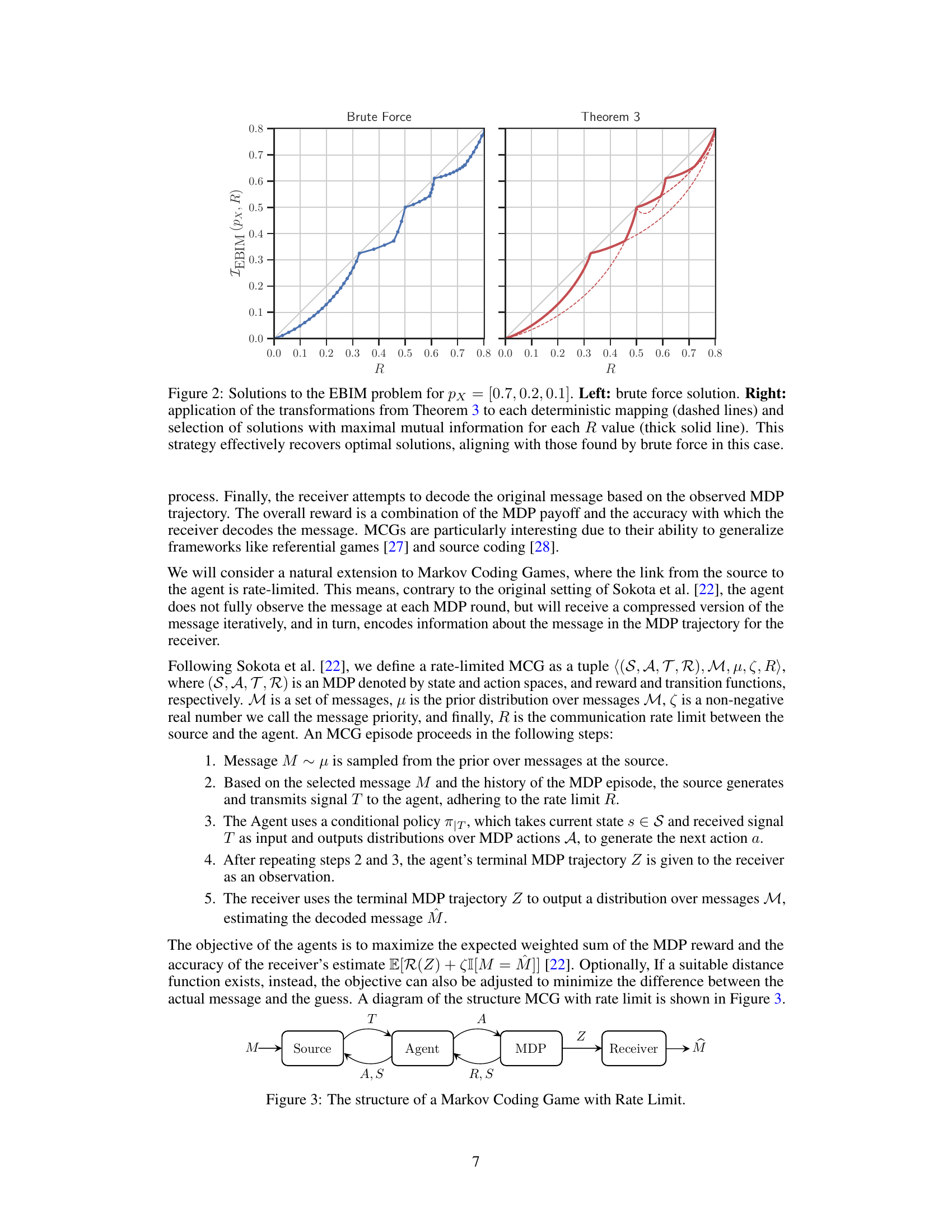

🔼 Figure 2 illustrates the effectiveness of the proposed method for solving the Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) problem. The left panel shows the optimal solutions obtained via brute-force search for the input distribution pX = [0.7, 0.2, 0.1]. The right panel demonstrates the proposed two-step approach, where deterministic mappings are first identified using Algorithm 1, and then the optimal couplings near these mappings are found using Theorem 3. The dashed lines represent the couplings obtained from applying Theorem 3 to each deterministic mapping, while the thick solid line highlights the optimal couplings selected from among those solutions. This figure highlights the efficacy of the proposed algorithm in closely approximating the optimal solutions obtained by exhaustive search.

read the caption

Figure 2: Solutions to the EBIM problem for pX=[0.7,0.2,0.1]subscript𝑝𝑋0.70.20.1p_{X}=[0.7,0.2,0.1]italic_p start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_X end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = [ 0.7 , 0.2 , 0.1 ]. Left: brute force solution. Right: application of the transformations from Theorem 3 to each deterministic mapping (dashed lines) and selection of solutions with maximal mutual information for each R𝑅Ritalic_R value (thick solid line). This strategy effectively recovers optimal solutions, aligning with those found by brute force in this case.

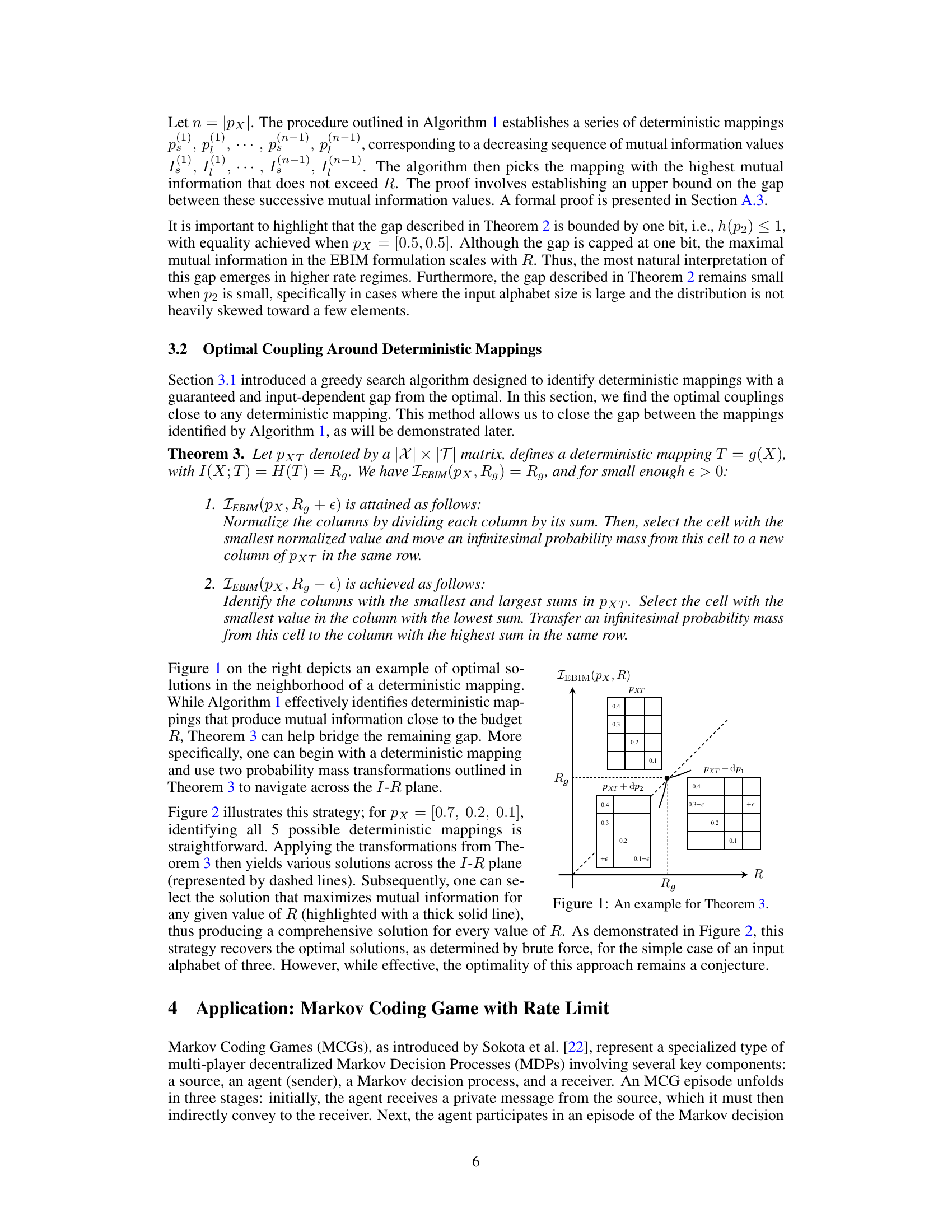

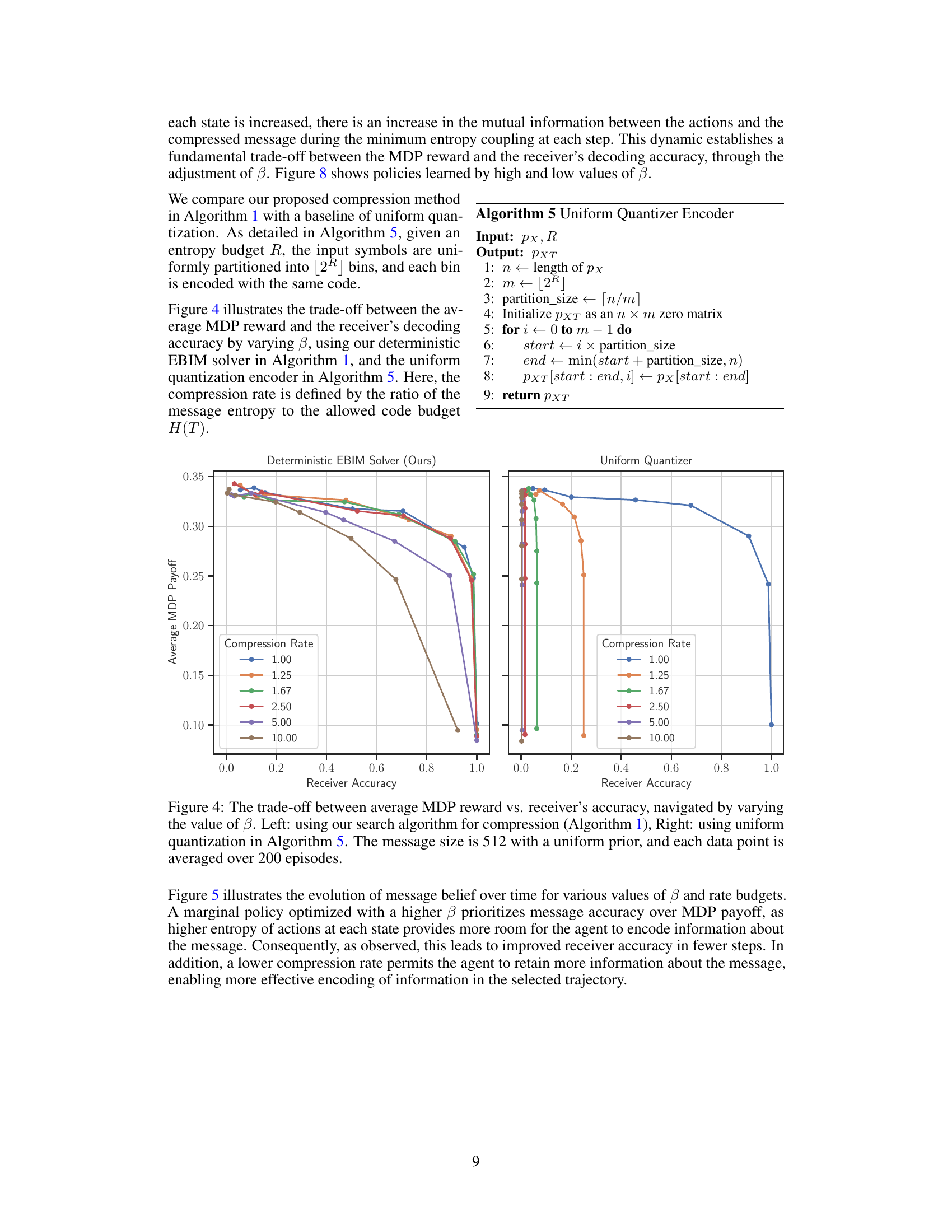

🔼 In a rate-limited Markov Coding Game, a source transmits a message to a receiver via an agent. The agent participates in a Markov Decision Process (MDP) where actions indirectly convey information about the message. The source compresses the message (signal T) before transmission to the agent, who then uses this information to guide its actions in the MDP. Finally, the receiver attempts to decode the original message from the agent’s observed MDP trajectory. The communication channel between the source and the agent has a rate constraint, limiting the amount of information that can be transmitted.

read the caption

Figure 3: The structure of a Markov Coding Game with Rate Limit.

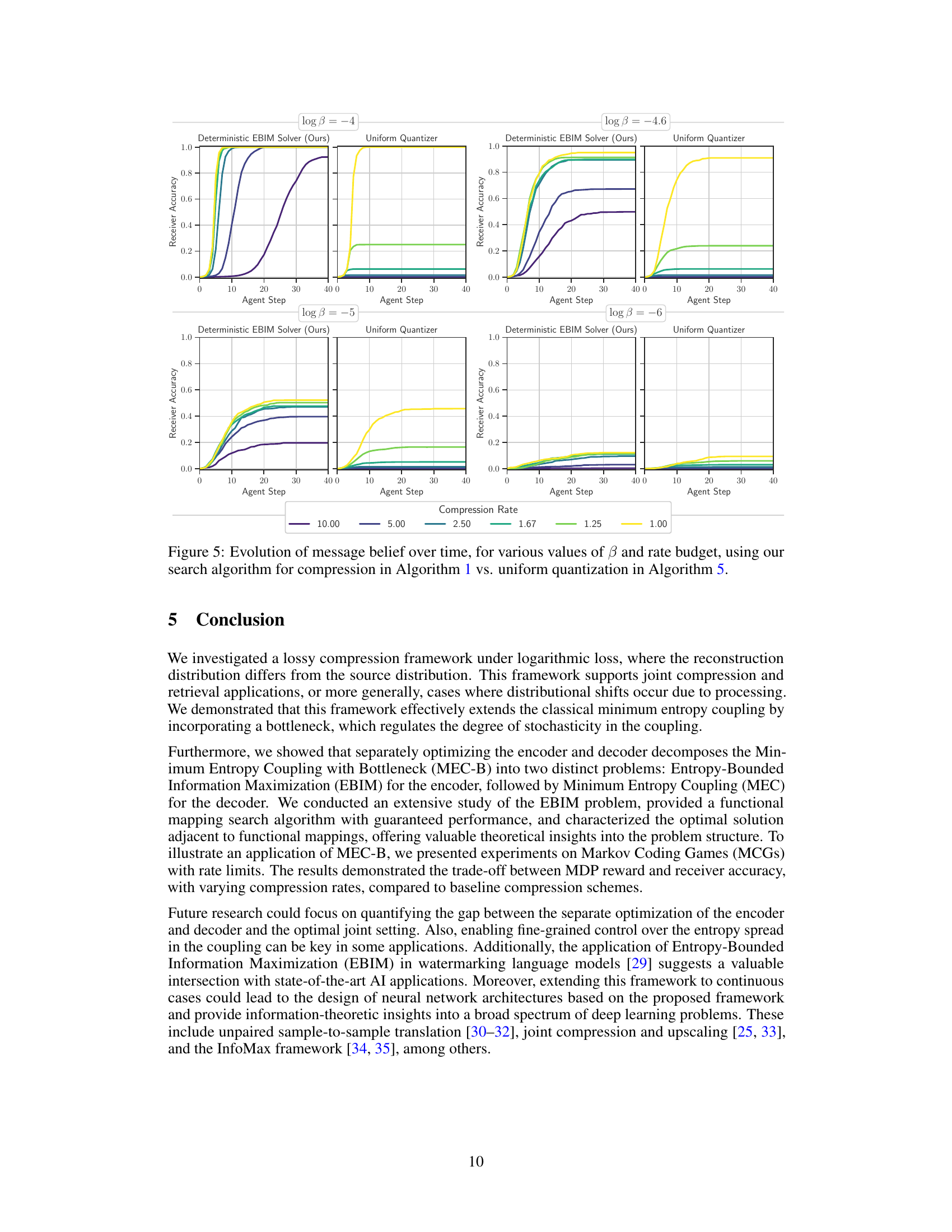

🔼 This figure illustrates the trade-off between the average reward obtained in a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and the accuracy with which a receiver decodes a message, controlled by a parameter β (beta). The left panel shows results using a novel deterministic search algorithm for message compression (Algorithm 1), while the right panel presents a baseline approach using uniform quantization (Algorithm 5). Both approaches are tested with messages of size 512, uniformly distributed a priori. Each data point plotted represents the average outcome over 200 MDP episodes.

read the caption

Figure 4: The trade-off between average MDP reward vs. receiver’s accuracy, navigated by varying the value of β𝛽\betaitalic_β. Left: using our search algorithm for compression (Algorithm 1), Right: using uniform quantization in Algorithm 5. The message size is 512 with a uniform prior, and each data point is averaged over 200 episodes.

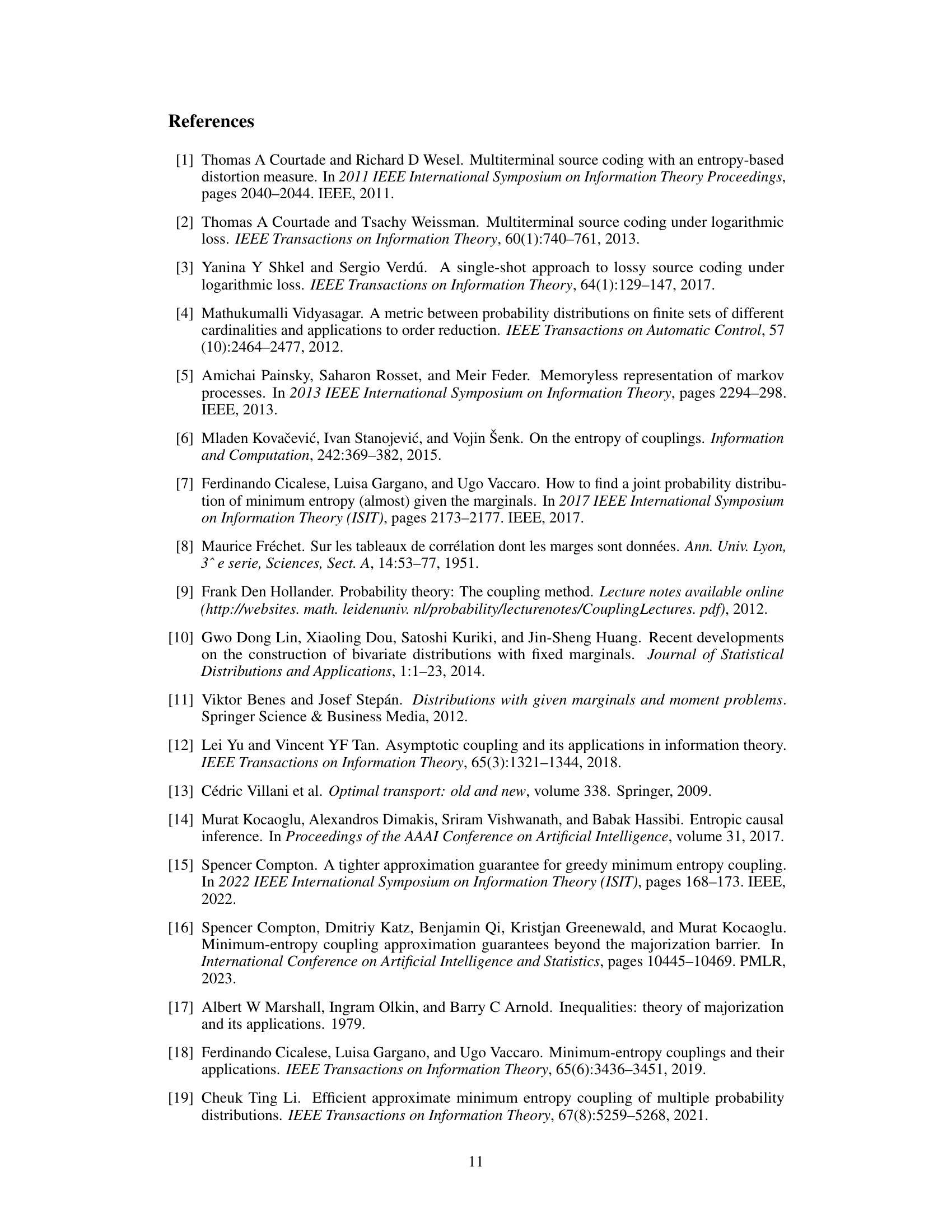

🔼 This figure visualizes the evolution of message belief (probability distribution over messages) across different time steps (agent actions) in a Markov Coding Game. It compares two compression methods: the authors’ proposed deterministic EBIM solver (Algorithm 1) and a uniform quantization method (Algorithm 5). Different lines represent different values of the temperature parameter (β) which controls the stochasticity of the agent’s policy. Each plot shows a different compression rate (the ratio of message entropy to code budget). The figure demonstrates how the message belief converges toward the true message over time, illustrating the impact of both the compression method and the temperature parameter on decoding accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 5: Evolution of message belief over time, for various values of β𝛽\betaitalic_β and rate budget, using our search algorithm for compression in Algorithm 1 vs. uniform quantization in Algorithm 5.

🔼 This figure illustrates the optimal solutions for the Entropy-Bounded Information Maximization (EBIM) problem in the vicinity of a deterministic mapping. It shows how the optimal solution changes as the entropy constraint (R) varies slightly above and below the entropy of the deterministic mapping (Rg). The figure helps to visualize the impact of small changes to the entropy constraint on the optimal coupling between the input and output variables (X and T). Specifically, it demonstrates the methods described in Theorem 3 for finding optimal couplings near a deterministic mapping by transferring infinitesimal probability mass between cells of the joint distribution matrix.

read the caption

Figure 6: Optimal solutions in the neighborhood of a deterministic mapping.

🔼 The figure shows a grid world environment used in Markov Coding Game experiments. The agent starts in a red circle and must navigate to a green goal circle, avoiding a red trap and grey obstacles. Crucially, the agent’s policy is non-deterministic, with probabilities for moving in each direction shown in each cell. The black path illustrates one possible trajectory of the agent, demonstrating how the noisy environment can cause deviations from the intended actions.

read the caption

Figure 7: The Grid World Setup used in the experiments. The starting cell is depicted by a red circle, while the goal, trap, and obstacle cells are colored green, red, and grey, respectively. Additionally, a non-deterministic policy is demonstrated through the probabilities of actions in each direction within each cell. The path taken by the agent is traced in black. Note that due to the noisy environment, the agent may move in directions not explicitly suggested by the policy.

🔼 This figure visualizes the Maximum Entropy policies obtained through Soft Q-value iteration (Algorithm 8) for two different values of the beta parameter (β). The left panel displays the policy when log(β) = -6, indicating a preference for high randomness in actions. Conversely, the right panel shows the policy when log(β) = -3, demonstrating a lower level of randomness in actions. The policies are represented as matrices, mapping states to action probabilities, and are learned within the Markov Coding Game environment described in the paper. These policies highlight the trade-off between the level of randomness in actions and their contribution to the overall reward within the game.

read the caption

Figure 8: The Maximum Entropy policy learned through Soft Q-Value iteration of Algorithm 8, for logβ=−6𝛽6\log\beta=-6roman_log italic_β = - 6 (left) and logβ=−3𝛽3\log\beta=-3roman_log italic_β = - 3 (right).

🔼 This figure compares the mutual information achieved by our proposed deterministic EBIM solver against the encoder proposed by Shkel et al. [3], for different maximum allowed code entropies. The left panel shows results for a Binomial distribution, while the right panel presents results for a Truncated Geometric distribution. The comparison highlights the superior performance of our proposed approach, especially in lower rate regimes.

read the caption

Figure 9: Obtained I(X;T)𝐼𝑋𝑇I(X;T)italic_I ( italic_X ; italic_T ) vs. maximum allowed H(T)𝐻𝑇H(T)italic_H ( italic_T ) for Binomial (left) and Truncated Geometric (right) input distributions.

🔼 Figure 10 illustrates the impact of compression rate on the resulting coupling between the input (X) and output (Y) distributions in the Minimum Entropy Coupling with Bottleneck (MEC-B) framework. The input and output distributions are uniform. The compression rate is calculated as the ratio of the input entropy H(X) to the allowed code rate R. The figure shows that at lower compression rates (H(X)/R closer to 1), couplings tend to be deterministic, with little stochasticity. As the compression rate increases (H(X)/R becomes larger), the couplings become increasingly stochastic, characterized by higher entropy and less predictability in mapping from X to Y.

read the caption

Figure 10: Generated couplings in MEC-B formulation (2), for uniform input and output distributions. The compression rate is defined as H(X)/R𝐻𝑋𝑅H(X)/Ritalic_H ( italic_X ) / italic_R. Higher compression rates lead to more stochastic couplings with increased entropy.

🔼 This block diagram illustrates the architecture of the unsupervised image restoration framework. It shows the data flow from a low-resolution input image (X) through an encoder (f_θ) that produces a compressed representation (T). This compressed representation is then passed to a generator (g_φ), which adds noise (z) to produce an upscaled, potentially noisy image (Ŷ). A discriminator (d_ψ) is used to enforce the desired output distribution (p_Y) by comparing the generated upscaled image to high-resolution images in the target domain (Y). Finally, a reconstructor network (α_γ) refines the image based on Ŷ and the compressed representation T.

read the caption

Figure 11: Block diagram of the unsupervised image restoration framework.

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of unsupervised image restoration on the MNIST dataset. It showcases the reconstructed images from compressed representations, varying the number of code dimensions and bits per dimension. Each image grid represents a set of reconstructed images, demonstrating the impact of compression parameters on the quality of the restored images.

read the caption

Figure 12: Output samples from the MNIST dataset, for different number of code dimensions and the number of bits per dimension of the code.

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of input and output images from the Street View House Numbers (SVHN) dataset after applying an unsupervised image restoration technique. The input images are low-resolution, and the outputs show the corresponding upscaled versions. This illustrates the model’s ability to reconstruct higher-resolution images from lower-resolution input without direct paired training data, which is a key characteristic of unsupervised learning.

read the caption

Figure 13: Input and output samples from the SVHN dataset.

Full paper#