↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current AI systems excel at everyday tasks, but their capabilities in assisting research remain largely unexplored. This research addresses this gap by introducing challenges related to research workflow including equation inference, experimental design, paper weakness identification, and review critique.

The study introduces AAAR-1.0, a benchmark dataset designed to evaluate Large Language Models (LLMs) in these four tasks. The results show that while closed-source LLMs demonstrate higher accuracy, both open and closed source models exhibit significant limitations in handling nuanced, expertise-intensive research processes, underscoring the need for further development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers as it introduces AAAR-1.0, a novel benchmark dataset for evaluating LLMs’ performance in expertise-intensive research tasks. This benchmark fills a significant gap in evaluating LLMs’ capabilities in real-world research scenarios, thereby enabling more accurate assessments of their potential and limitations.

Visual Insights#

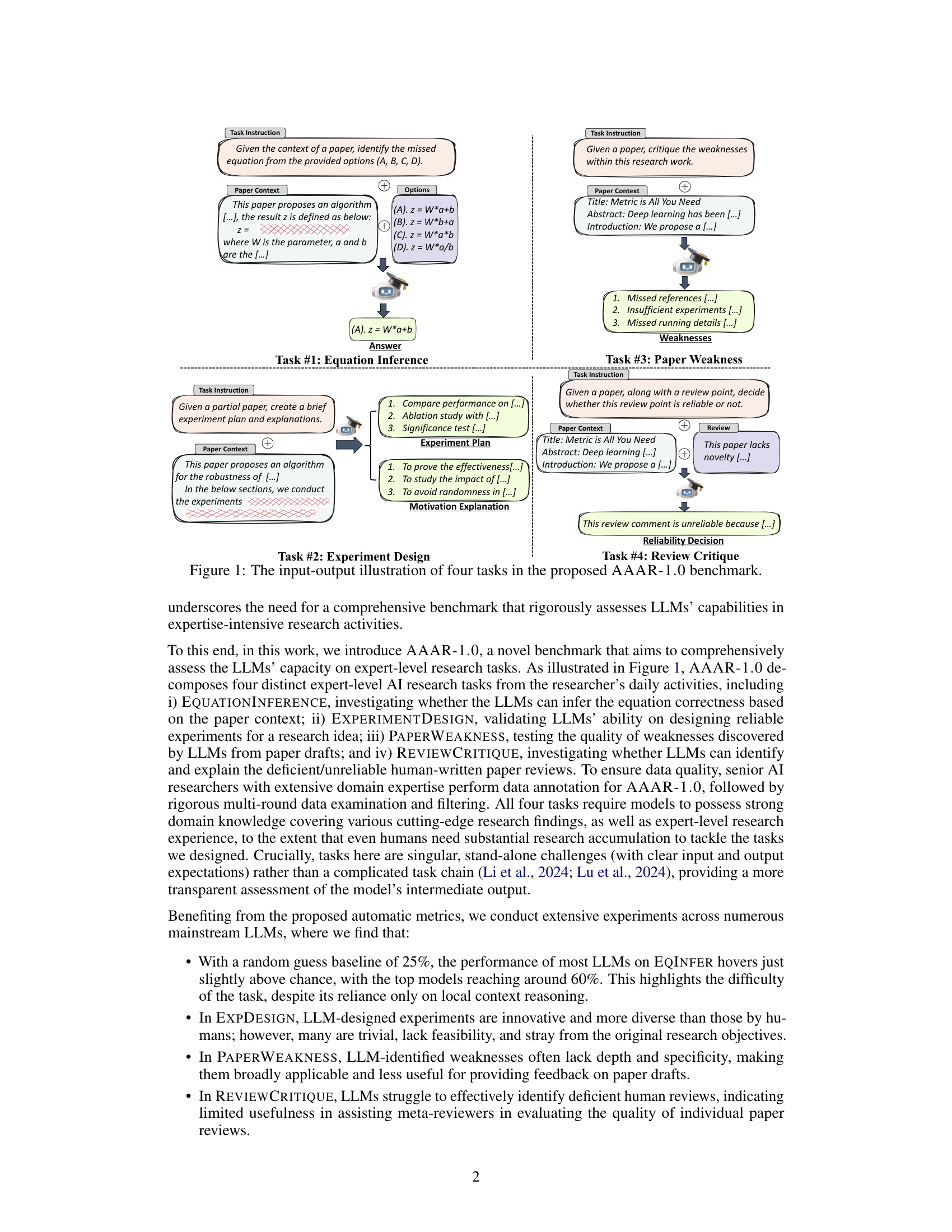

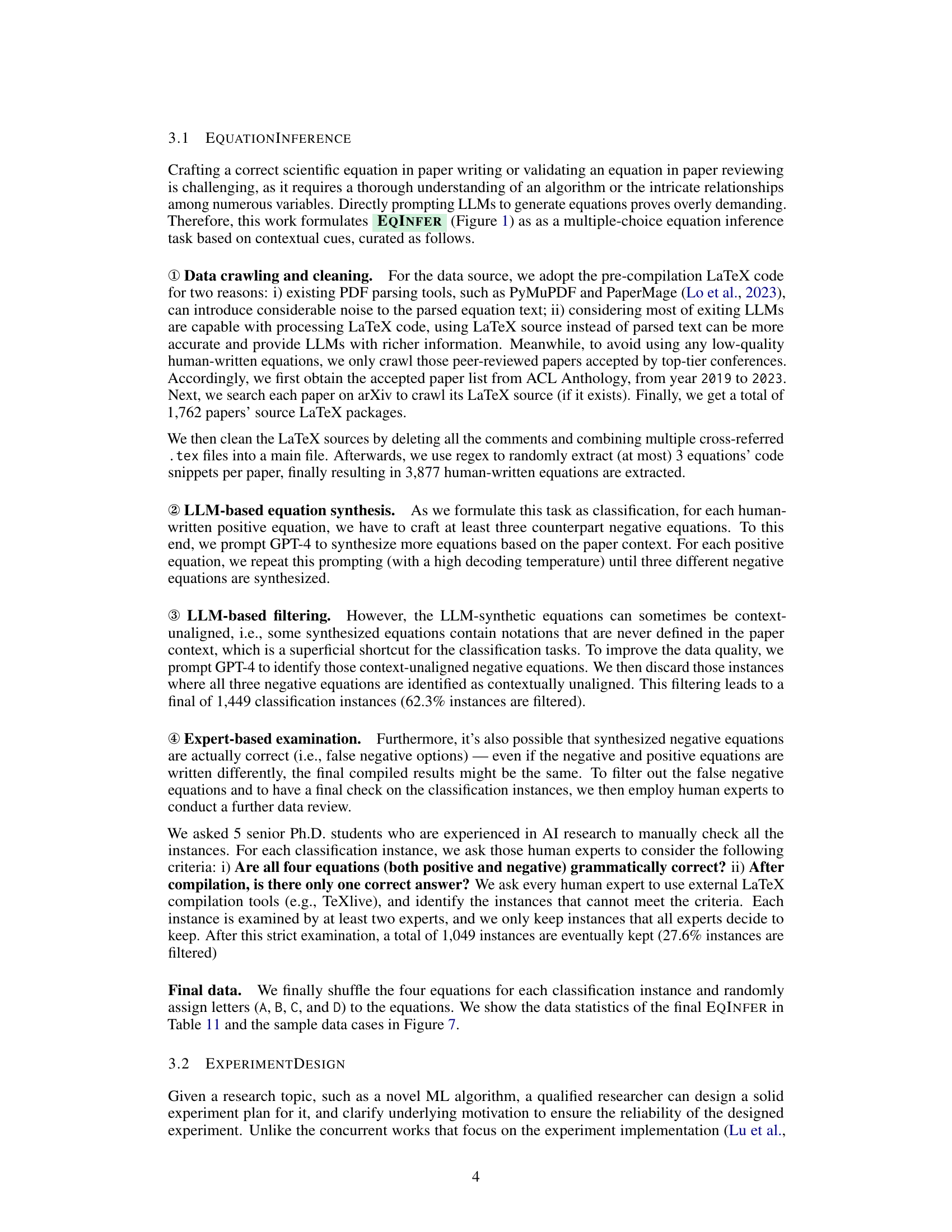

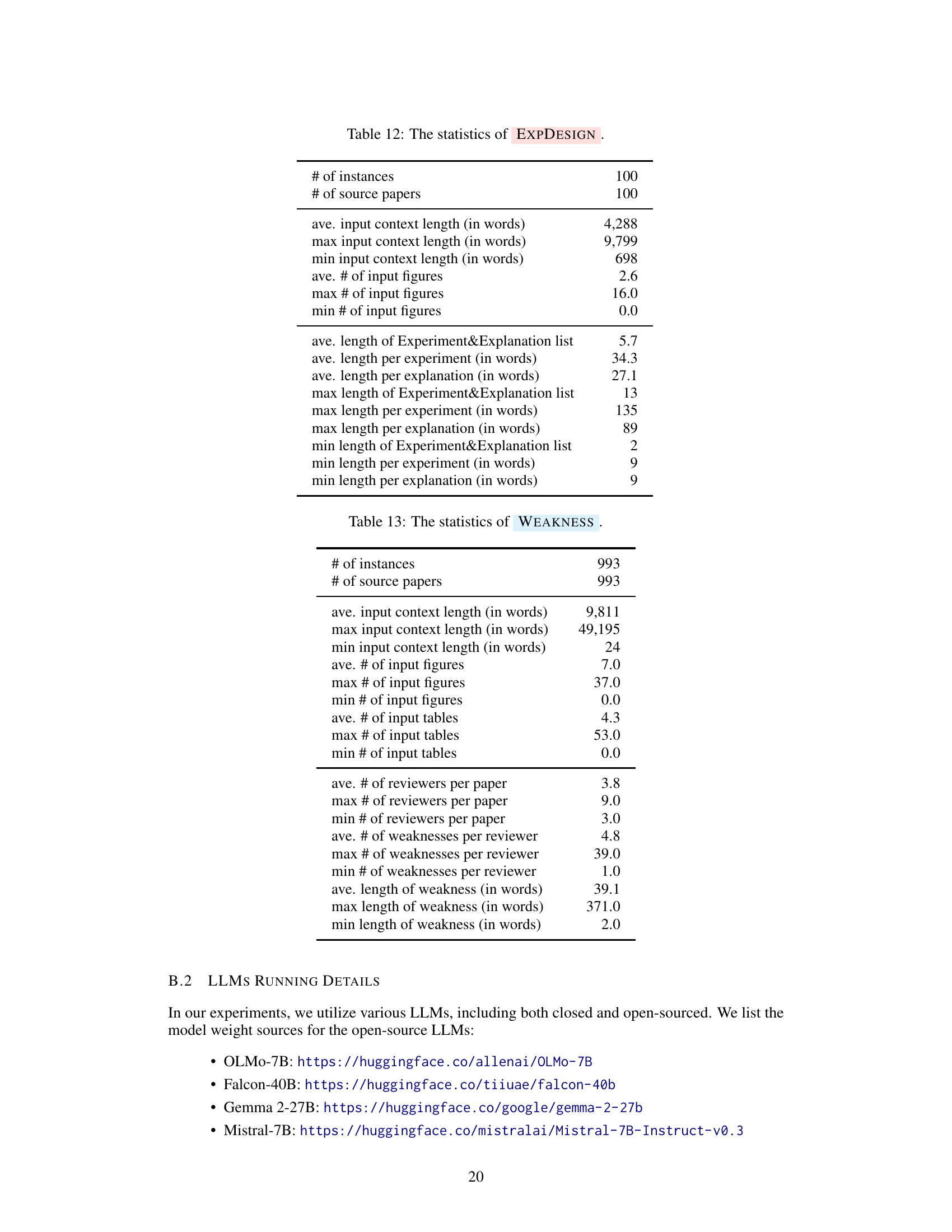

🔼 This figure illustrates the input and output formats for each of the four tasks in the AAAR-1.0 benchmark dataset. Each task involves a different aspect of research: Equation Inference (inferring equations from context), Experiment Design (creating experiment plans), Paper Weakness Identification (finding flaws in papers), and Review Critique (evaluating review quality). For each task, the figure shows the type of input provided to the model (e.g., paper text, incomplete equations, a research idea) and the expected output (e.g., a correct equation, an experiment plan, a list of identified weaknesses, a judgment of the review’s reliability).

read the caption

Figure 1: The input-output illustration of four tasks in the proposed AAAR-1.0 benchmark.

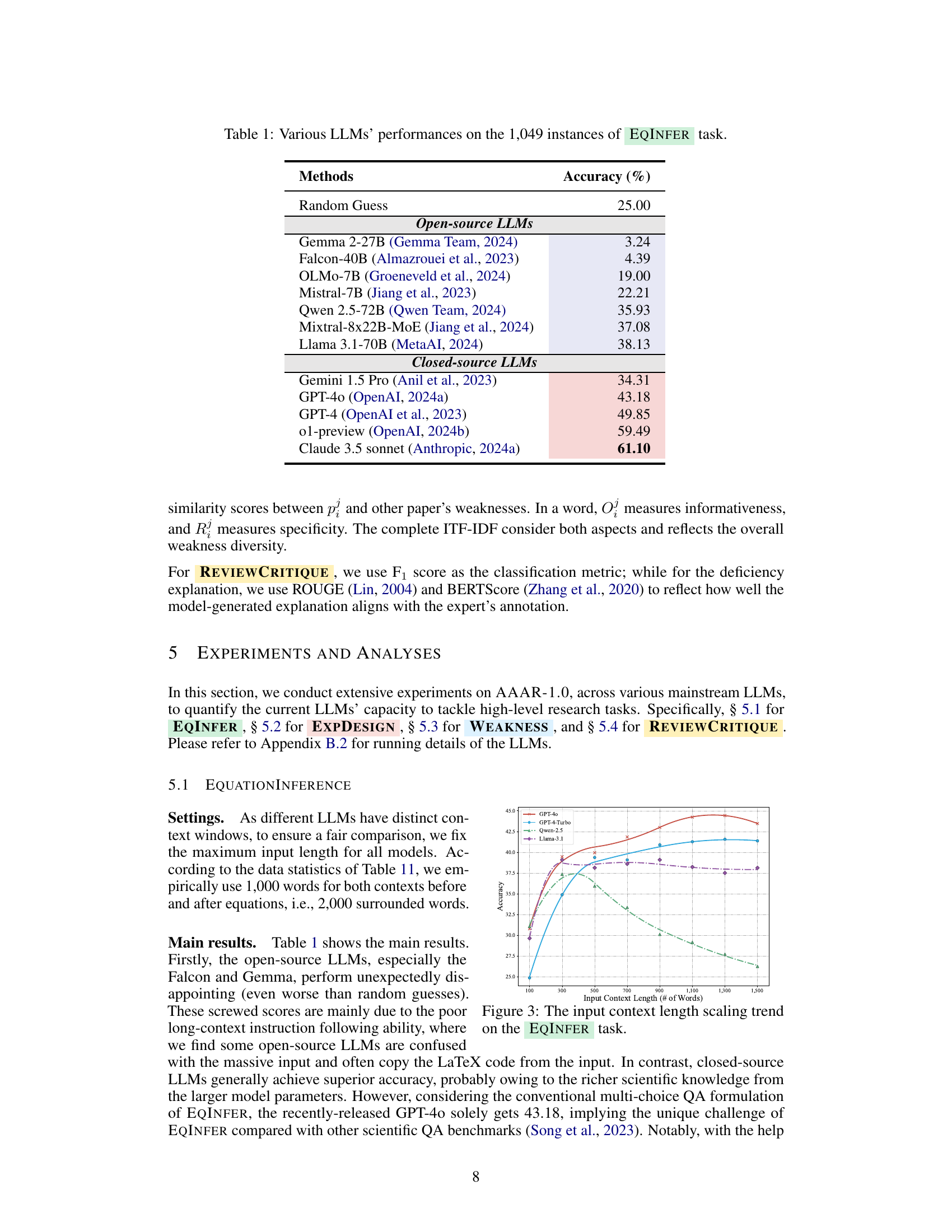

| Methods | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| Random Guess | 25.00 |

| Open-source LLMs | |

| Gemma 2-27B [^(Gemma Team, 2024)] | 3.24 |

| Falcon-40B [^(Almazrouei et al., 2023)] | 4.39 |

| OLMo-7B [^(Groeneveld et al., 2024)] | 19.00 |

| Mistral-7B [^(Jiang et al., 2023)] | 22.21 |

| Qwen 2.5-72B [^(Qwen Team, 2024)] | 35.93 |

| Mixtral-8x22B-MoE [^(Jiang et al., 2024)] | 37.08 |

| Llama 3.1-70B [^(MetaAI, 2024)] | 38.13 |

| Closed-source LLMs | |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro [^(Anil et al., 2023)] | 34.31 |

| GPT-4o [^(OpenAI, 2024a)] | 43.18 |

| GPT-4 [^(OpenAI et al., 2023)] | 49.85 |

| o1-preview [^(OpenAI, 2024b)] | 59.49 |

| Claude 3.5 sonnet [^(Anthropic, 2024a)] | 61.10 |

🔼 This table presents the accuracy scores achieved by various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the Equation Inference (EqInfer) task. The EqInfer task involves assessing the correctness of equations within the context of a research paper. The table compares the performance of both open-source and closed-source LLMs, providing insights into the strengths and limitations of different models in solving this research-oriented task. The accuracy is calculated as the percentage of correctly identified equations.

read the caption

Table 1: Various LLMs’ performances on the 1,049 instances of EqInfer task.

In-depth insights#

Novel Method Unveiled#

The heading ‘Novel Method Unveiled’ likely introduces a new approach or technique. Without the actual PDF content, a specific summary is impossible. However, a thoughtful analysis would explore the method’s underlying principles, its innovation compared to existing methods, and its potential applications and impact. A detailed summary would cover the method’s algorithm, methodology, data requirements, and limitations. Crucially, it would analyze its performance metrics, experimental results, and validation. Finally, the summary would discuss the broader implications of this novel method for the research field, including its advantages and potential future developments.

Groundbreaking Results#

The heading ‘Groundbreaking Results’ in a research paper signifies a section detailing significant and novel findings. A thoughtful summary requires access to the PDF’s content. However, a general approach would involve identifying the key metrics, methodologies, and comparisons presented. The core claim of the ‘Groundbreaking Results’ section often revolves around exceeding the state-of-the-art in performance, accuracy, efficiency, or other relevant benchmarks. A robust summary would analyze not just the quantitative results but also the qualitative interpretations, and limitations. It is crucial to note whether the groundbreaking nature is in terms of a complete paradigm shift or incremental improvement. A strong summary would highlight the broader implications of these results for the research field and future research directions, while acknowledging any potential limitations or areas requiring further investigation. In short, a good summary contextualizes the results and places them within the larger context of the research area to give a complete picture.

Methodological Depth#

The provided context lacks the actual research paper content, preventing a summary of the ‘Methodological Depth’ section. To generate a summary, please provide the text of the research paper’s ‘Methodological Depth’ section. A thoughtful analysis would then be conducted to identify key methodological choices, assess their strengths and limitations, and explore their implications. The summary would focus on the rigor and appropriateness of the methods used, highlighting any innovative techniques or limitations in their application, and ultimately evaluating the overall contribution of the methodological choices to the study’s validity and reliability. This might include a discussion of data collection strategies, analytic approaches, or validation techniques. The resulting summary would be concise yet informative, providing a valuable overview of the study’s methodological underpinnings.

Future Research#

The ‘Future Research’ section of this paper highlights several promising avenues for future investigation. Extending the model to handle more complex research tasks, such as those involving multiple steps or requiring external knowledge sources, is a key area. Improving the model’s ability to handle noisy or ambiguous data is also crucial. Additionally, exploring different model architectures and training methods is suggested to further enhance performance. Finally, the authors propose developing more robust evaluation metrics to accurately assess the model’s performance and facilitate meaningful comparisons across various tasks.

Study Limitations#

The study acknowledges several limitations. Data limitations are noted, particularly the relatively small dataset size for some tasks, potentially impacting the robustness of the LLM performance evaluation. The use of open-source platforms for data collection might introduce bias due to potential training overlap with evaluated LLMs, thus affecting the fairness of comparisons. Methodological limitations include focusing primarily on single-step tasks rather than complex research workflows. Future work will address these limitations by expanding the dataset and exploring more comprehensive research processes.

More visual insights#

More on figures

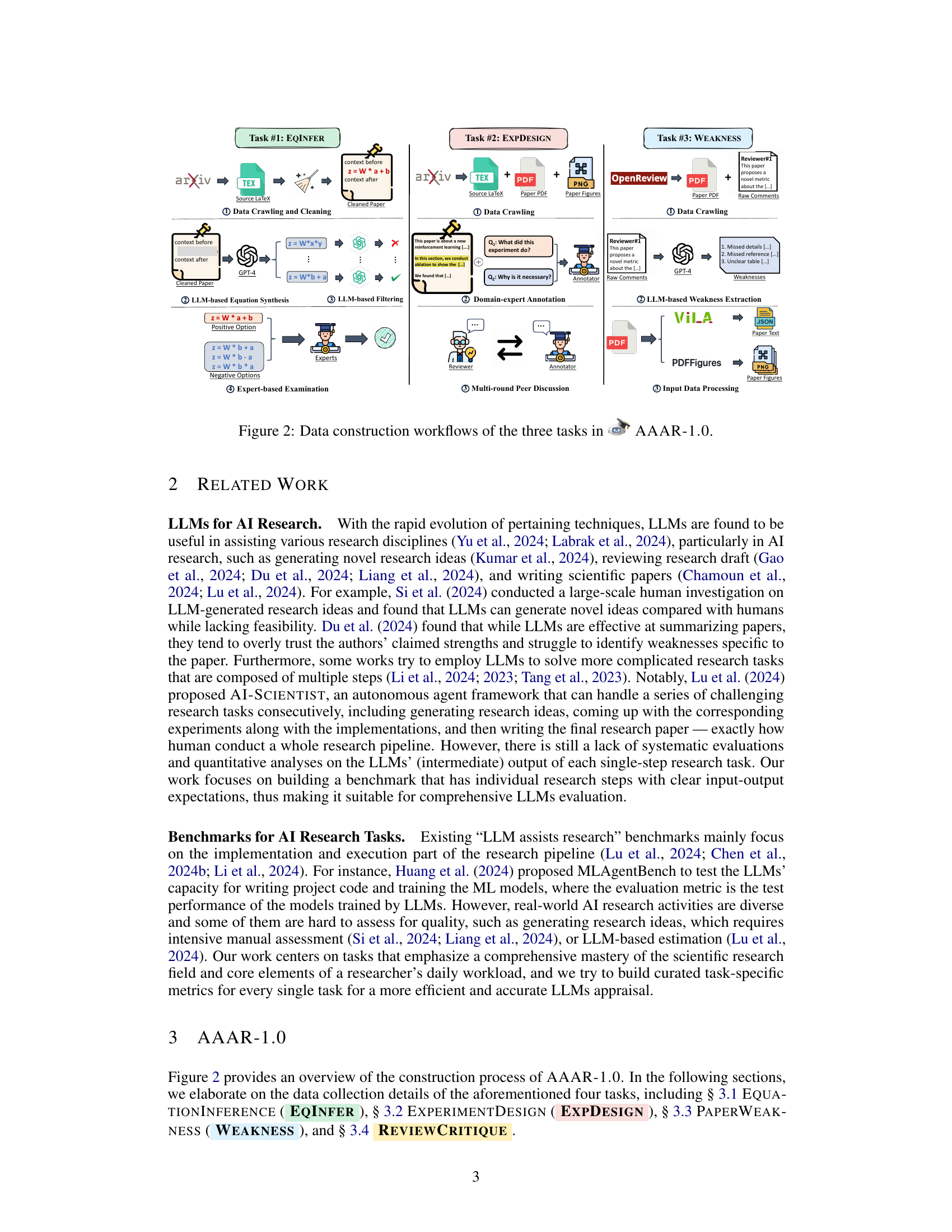

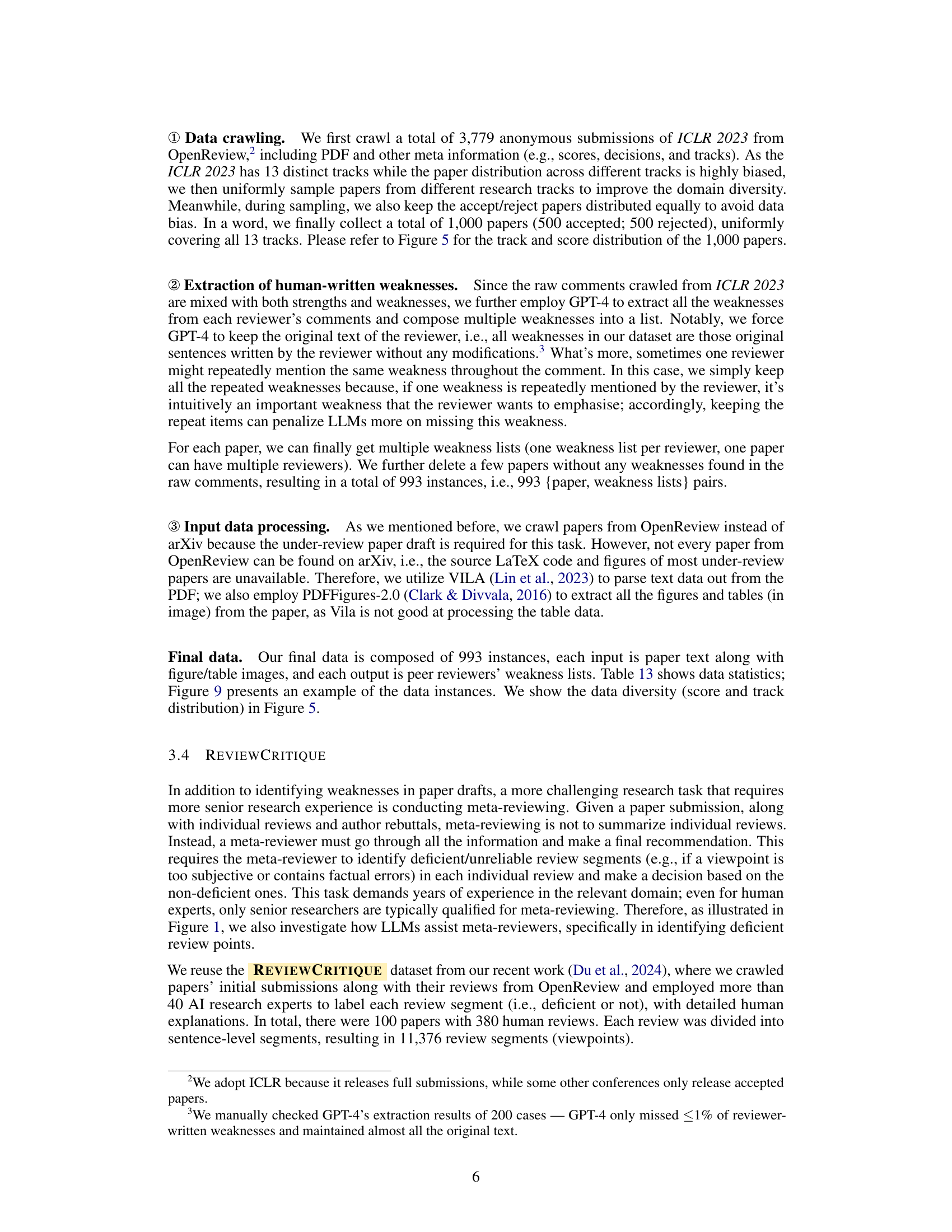

🔼 This figure illustrates the data construction pipelines for three of the four tasks in the AAAR-1.0 benchmark dataset. For each task (Equation Inference, Experiment Design, and Paper Weakness), it shows the steps involved in gathering data, cleaning and preprocessing that data, and using LLMs for synthesis and filtering. The figure details the role of human experts in ensuring data quality and consistency for each task. The different data sources used (arXiv, OpenReview, etc.) and the various LLMs employed (GPT-4, etc.) in the creation of the dataset are also showcased. The figure visually represents the complex process of creating a high-quality benchmark dataset suitable for evaluating LLMs on AI research-related tasks.

read the caption

Figure 2: Data construction workflows of the three tasks in AAAR-1.0.

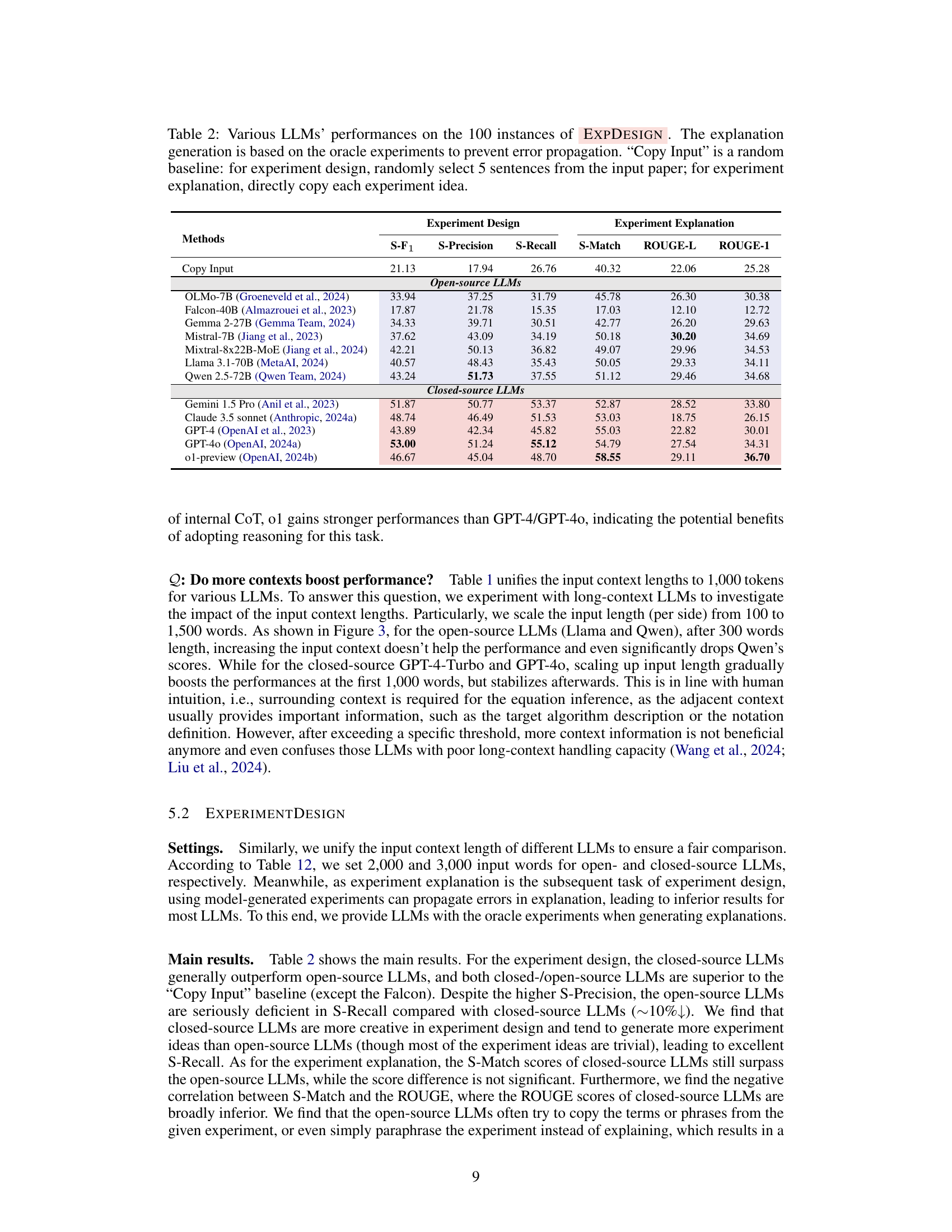

🔼 This figure displays the relationship between the length of the input context and the accuracy of various LLMs on the equation inference task (EqInfer). The x-axis represents the length of the input context in words, while the y-axis represents the accuracy achieved by different language models. The graph shows how the accuracy changes as the input context length increases. It helps to understand the impact of context window size on the LLM’s performance on this specific task.

read the caption

Figure 3: The input context length scaling trend on the EqInfer task.

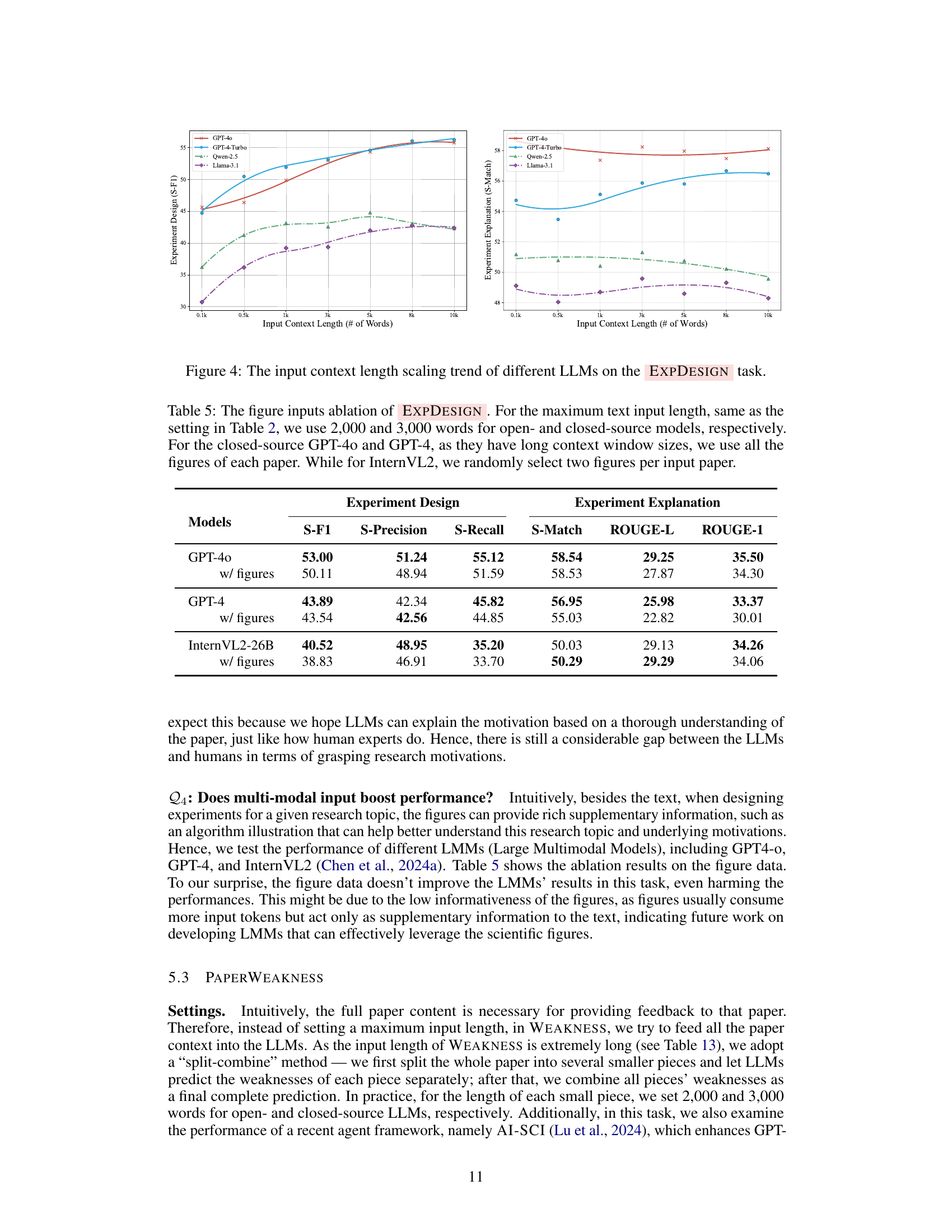

🔼 Figure 4 illustrates how the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the Experiment Design task changes with varying lengths of input context. The x-axis represents the length of the input context (in words), while the y-axis shows the performance metric (likely S-F1 score or a similar metric assessing the quality of the generated experiment design). The plot allows for a comparison of different LLMs’ abilities to generate effective experiment plans given different amounts of contextual information. The figure helps to determine if longer contexts are always beneficial, or if there’s an optimal length for LLMs to achieve the best performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: The input context length scaling trend of different LLMs on the ExpDesign task.

🔼 This figure shows a pie chart illustrating the distribution of review scores for the papers included in the WEAKNESS dataset. The scores range from 1 to 10, representing a scale of review quality. Each slice of the pie chart corresponds to a specific score range, with its size proportional to the number of papers that received that score. This visualization helps to understand the overall quality and diversity of the papers used in the benchmark dataset.

read the caption

(a) The review score distribution of the papers used in Weakness.

🔼 The bar chart visualizes the distribution of the 1000 papers used in the WEAKNESS dataset across 13 different research tracks within the ICLR 2023 conference. Each bar represents a track, and its height corresponds to the number of papers belonging to that track. The purpose is to show the diversity of research areas represented in the dataset and ensure the sample is not skewed towards any particular area.

read the caption

(b) The track distribution of the papers used in Weakness.

🔼 This figure visualizes the diversity of the WEAKNESS dataset used in the paper. The left panel (a) shows a pie chart illustrating the distribution of overall scores assigned to papers in the dataset, categorizing papers based on score ranges. The right panel (b) presents a bar chart showing the distribution of papers across different research tracks within the dataset. This dual representation provides a comprehensive view of the dataset’s composition, highlighting the balance between score ranges and representation of diverse research topics. The aim is to demonstrate the breadth and quality of the dataset used to evaluate the performance of Large Language Models.

read the caption

Figure 5: The data diversity illustration of Weakness, including the score distribution and track distribution of the papers used in our dataset.

🔼 Figure 6 shows the annotation platform used for the Experiment Design task in the AAAR-1.0 benchmark. The process involves annotators first reviewing a research paper’s PDF on Google Drive and adding comments directly to the document. These comments, which detail suggested experiments and their motivations, are then transcribed into a structured online Google Doc. This two-step process allows for both initial annotations within the context of the paper itself, followed by a structured recording and a later opportunity for review and discussion to improve data quality and consistency.

read the caption

Figure 6: The annotation platform for collecting the annotation of ExpDesign. We ask annotators to first make comments on the Google Drive PDF, then move all the annotations to the online Google Doc (for further verification and discussion).

🔼 This figure illustrates an example from the Equation Inference task in the AAAR-1.0 benchmark dataset. The task requires the model to select the correct mathematical equation from four options (A-D), given the surrounding textual context from a research paper. The context consists of ‘Context Before’ and ‘Context After’ snippets providing surrounding information, while the actual equation is removed and replaced with the four options. The model’s task is to identify the most appropriate equation from the options based on the context, which requires a deep understanding of the algorithm and mathematical concepts in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 7: A sample case of EqInfer.

🔼 This figure shows a sample from the dataset used to evaluate large language models’ ability to design experiments. It illustrates the input and output components of the EXPDESIGN task. The input is a segment of text from a research paper, providing context about a given topic. The expected output consists of two parts: 1) a list of experiment designs that a researcher would conduct to investigate the topic covered in the input text and 2) a list of explanations justifying the reasons for each proposed experiment. The goal is to assess the model’s ability to both conceive of appropriate experiments and articulate their underlying rationales, mirroring a core aspect of research methodology.

read the caption

Figure 8: A sample case of ExpDesign.

🔼 This figure showcases an example from the PAPERWEAKNESS section of the AAAR-1.0 benchmark dataset. It illustrates the task of identifying weaknesses in a research paper. The input shows a segment of a research paper describing a Neural Process (NP) model. The output displays a list of weaknesses identified by human reviewers, demonstrating diverse issues in the paper, such as unclear writing, insufficient experimentation, and lack of comparison with state-of-the-art models. This exemplifies the complexity and nuances involved in evaluating the quality and depth of a research paper.

read the caption

Figure 9: A sample case of Weakness.

🔼 This figure displays the prompts used in the Equation Inference task of the AAAR-1.0 benchmark. It shows three stages: 1) LLM-based Equation Synthesis, where an LLM generates equations based on given context; 2) LLM-based Equation Filtering, where another LLM assesses the correctness of the generated equations; and 3) Model Prediction, where the final task requires an LLM to select the correct equation from provided choices. The prompts are designed to evaluate the LLM’s ability to infer equations based on context.

read the caption

Figure 10: The prompts used in EqInfer, including both data collection and model prediction.

🔼 Figure 11 shows the process of data collection and model prediction in the Experiment Design task. The data collection prompt involves providing a sentence (or a short paragraph) from a paper and a list of its experiments to identify whether the sentence reveals experiment details. The model prediction prompt involves providing part of a paper with the experiment sections removed. The model must reconstruct the experiment list, based on understanding the paper’s research motivation, and then provide an explanation list corresponding one-to-one with the experiment list to clarify why each experiment is necessary.

read the caption

Figure 11: The prompts used in ExpDesign, including both data collection and model prediction.

🔼 Figure 12 shows the prompts used for the WEAKNESS task in the AAAR-1.0 benchmark. The prompts guide the large language model (LLM) to identify weaknesses in a research paper, given its text and figures. The prompt instructs the LLM to act as an expert reviewer, carefully reviewing the paper and providing a list of weaknesses, one per line. If the provided text is not research-related (e.g., an acknowledgement section), the LLM should output ‘No research content’.

read the caption

Figure 12: The prompts used in Weakness.

More on tables

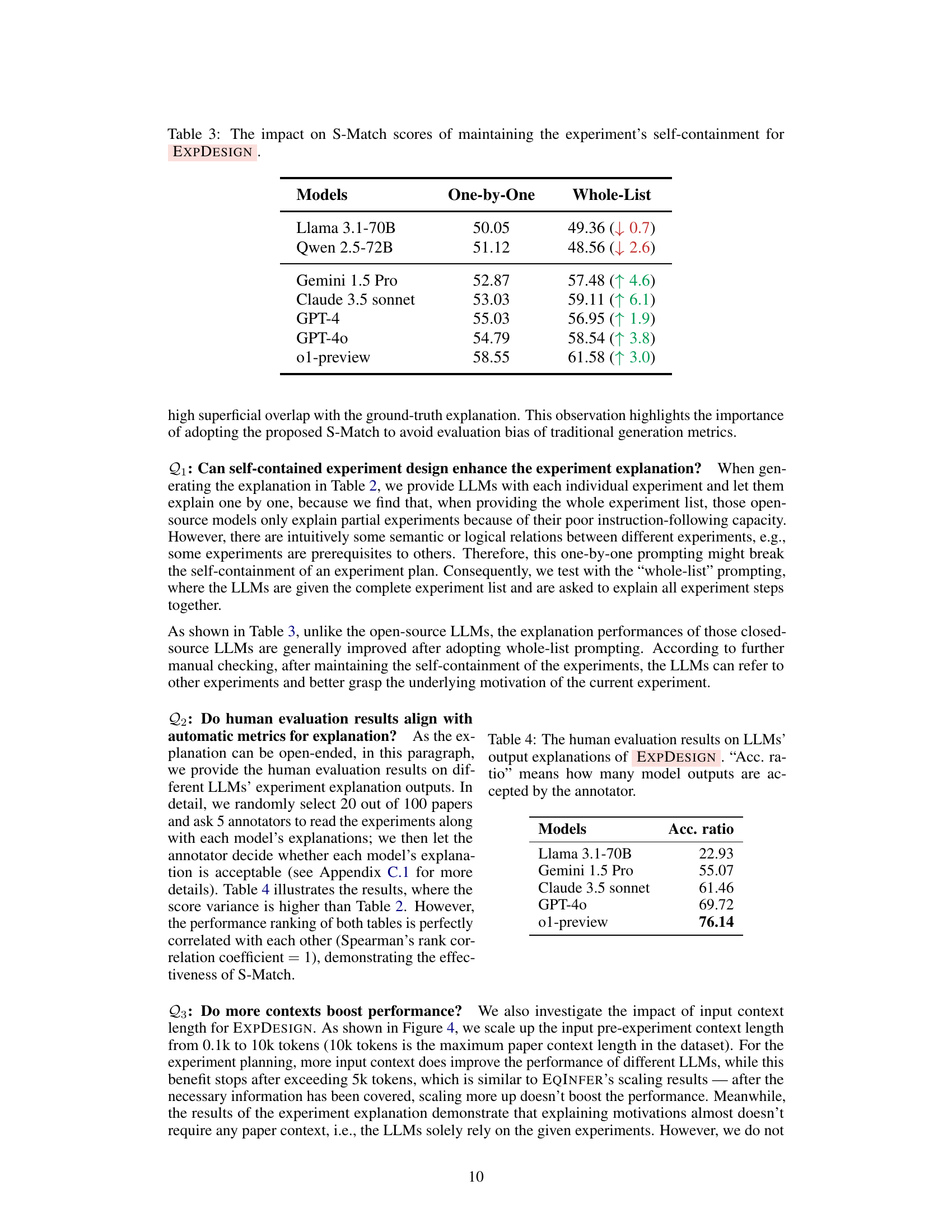

| Methods | S-F1 | S-Precision | S-Recall | S-Match | ROUGE-L | ROUGE-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment Design | ||||||

| Experiment Explanation | ||||||

| Methods | ||||||

| Copy Input | 21.13 | 17.94 | 26.76 | 40.32 | 22.06 | 25.28 |

| Open-source LLMs | ||||||

| OLMo-7B (Groeneveld et al., 2024) | 33.94 | 37.25 | 31.79 | 45.78 | 26.30 | 30.38 |

| Falcon-40B (Almazrouei et al., 2023) | 17.87 | 21.78 | 15.35 | 17.03 | 12.10 | 12.72 |

| Gemma 2-27B (Gemma Team, 2024) | 34.33 | 39.71 | 30.51 | 42.77 | 26.20 | 29.63 |

| Mistral-7B (Jiang et al., 2023) | 37.62 | 43.09 | 34.19 | 50.18 | 30.20 | 34.69 |

| Mixtral-8x22B-MoE (Jiang et al., 2024) | 42.21 | 50.13 | 36.82 | 49.07 | 29.96 | 34.53 |

| Llama 3.1-70B (MetaAI, 2024) | 40.57 | 48.43 | 35.43 | 50.05 | 29.33 | 34.11 |

| Qwen 2.5-72B (Qwen Team, 2024) | 43.24 | 51.73 | 37.55 | 51.12 | 29.46 | 34.68 |

| Closed-source LLMs | ||||||

| Gemini 1.5 Pro (Anil et al., 2023) | 51.87 | 50.77 | 53.37 | 52.87 | 28.52 | 33.80 |

| Claude 3.5 sonnet (Anthropic, 2024a) | 48.74 | 46.49 | 51.53 | 53.03 | 18.75 | 26.15 |

| GPT-4 (OpenAI et al., 2023) | 43.89 | 42.34 | 45.82 | 55.03 | 22.82 | 30.01 |

| GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024a) | 53.00 | 51.24 | 55.12 | 54.79 | 27.54 | 34.31 |

| o1-preview (OpenAI, 2024b) | 46.67 | 45.04 | 48.70 | 58.55 | 29.11 | 36.70 |

🔼 Table 2 presents the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the task of designing and explaining experiments. The dataset consists of 100 instances where each instance provides an excerpt of a research paper as input. The LLMs were evaluated on two sub-tasks: (1) generating an experiment design based on the input paper, and (2) generating an explanation for the proposed experiment design. The results are reported using several metrics, including S-F1, S-Precision, S-Recall, S-Match, and ROUGE-L/ROUGE-1. A ‘Copy Input’ baseline is included where the experiment design consists of 5 randomly selected sentences from the input paper, and the explanation is a direct copy of the experiment idea. This allows comparison against LLMs’ ability to synthesize more original and insightful experimental designs and explanations.

read the caption

Table 2: Various LLMs’ performances on the 100 instances of ExpDesign. The explanation generation is based on the oracle experiments to prevent error propagation. “Copy Input” is a random baseline: for experiment design, randomly select 5 sentences from the input paper; for experiment explanation, directly copy each experiment idea.

| Models | One-by-One | Whole-List |

|---|---|---|

| Llama 3.1-70B | 50.05 | 49.36 (↓ 0.7) |

| Qwen 2.5-72B | 51.12 | 48.56 (↓ 2.6) |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro | 52.87 | 57.48 (↑ 4.6) |

| Claude 3.5 sonnet | 53.03 | 59.11 (↑ 6.1) |

| GPT-4 | 55.03 | 56.95 (↑ 1.9) |

| GPT-4o | 54.79 | 58.54 (↑ 3.8) |

| o1-preview | 58.55 | 61.58 (↑ 3.0) |

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of maintaining the experiment’s self-containment on the S-Match scores in the EXPDESIGN task. Self-containment refers to the approach of presenting each experiment individually to the LLM for explanation, as opposed to providing the entire experiment list at once. The table compares the performance of various LLMs under both self-contained and non-self-contained scenarios, highlighting the effect of this approach on the quality of the generated explanations.

read the caption

Table 3: The impact on S-Match scores of maintaining the experiment’s self-containment for ExpDesign.

| Models | Acc. ratio |

|---|---|

| Llama 3.1-70B | 22.93 |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro | 55.07 |

| Claude 3.5 sonnet | 61.46 |

| GPT-4o | 69.72 |

| o1-preview | 76.14 |

🔼 This table presents the results of human evaluation on the quality of explanations generated by various Large Language Models (LLMs) for experiment designs. Human annotators assessed the acceptability of the LLM-generated explanations, and the ‘Acc. ratio’ column indicates the percentage of LLM explanations deemed acceptable by the annotators. This provides a qualitative measure of the LLM’s ability to not only generate experiment designs but also to provide understandable and justifiable rationales for those designs.

read the caption

Table 4: The human evaluation results on LLMs’ output explanations of ExpDesign. “Acc. ratio” means how many model outputs are accepted by the annotator.

| Models | S-F1 | S-Precision | S-Recall | S-Match | ROUGE-L | ROUGE-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | 53.00 | 51.24 | 55.12 | 58.54 | 29.25 | 35.50 |

| GPT-4o w/ figures | 50.11 | 48.94 | 51.59 | 58.53 | 27.87 | 34.30 |

| GPT-4 | 43.89 | 42.34 | 45.82 | 56.95 | 25.98 | 33.37 |

| GPT-4 w/ figures | 43.54 | 42.56 | 44.85 | 55.03 | 22.82 | 30.01 |

| InternVL2-26B | 40.52 | 48.95 | 35.20 | 50.03 | 29.13 | 34.26 |

| InternVL2-26B w/ figures | 38.83 | 46.91 | 33.70 | 50.29 | 29.29 | 34.06 |

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the impact of using figures as input in the experiment design task. It compares the performance of different large language models (LLMs) in generating experiment plans and their corresponding explanations with and without figure inputs. The experiment was conducted on 100 instances. The text input length was held consistent across LLMs (2000 and 3000 words for open- and closed-source models respectively). Closed-source models GPT-4 and GPT-40 used all available figures; InternVL2 used two randomly selected figures per paper. The metrics used to evaluate the performance are S-F1, S-Precision, S-Recall, S-Match, ROUGE-L, and ROUGE-1.

read the caption

Table 5: The figure inputs ablation of ExpDesign. For the maximum text input length, same as the setting in Table 2, we use 2,000 and 3,000 words for open- and closed-source models, respectively. For the closed-source GPT-4o and GPT-4, as they have long context window sizes, we use all the figures of each paper. While for InternVL2, we randomly select two figures per input paper.

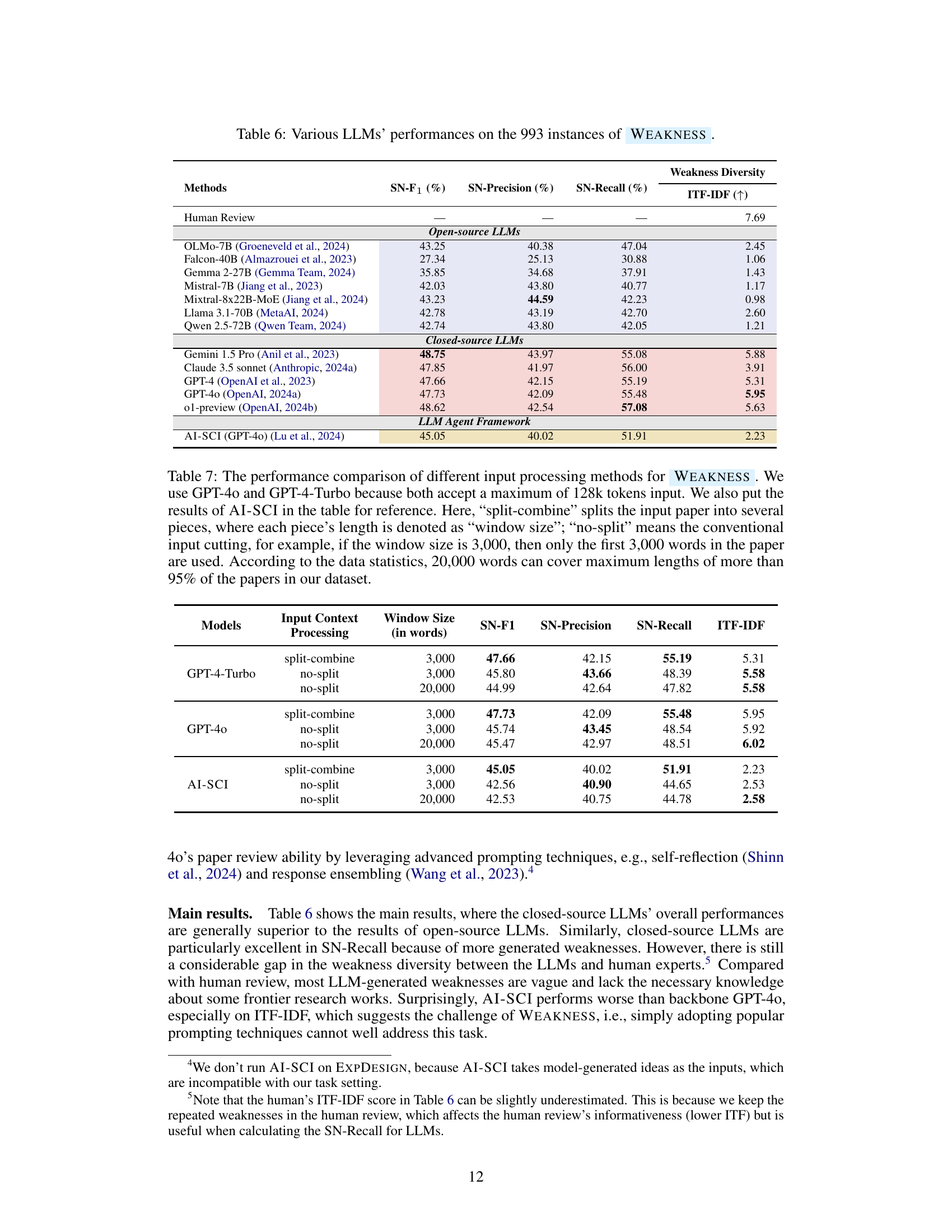

| Methods | SN-F1 (%) | SN-Precision (%) | SN-Recall (%) | ITF-IDF (↑) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Review | — | — | — | 7.69 |

| Open-source LLMs | ||||

| OLMo-7B (Groeneveld et al., 2024) | 43.25 | 40.38 | 47.04 | 2.45 |

| Falcon-40B (Almazrouei et al., 2023) | 27.34 | 25.13 | 30.88 | 1.06 |

| Gemma 2-27B (Gemma Team, 2024) | 35.85 | 34.68 | 37.91 | 1.43 |

| Mistral-7B (Jiang et al., 2023) | 42.03 | 43.80 | 40.77 | 1.17 |

| Mixtral-8x22B-MoE (Jiang et al., 2024) | 43.23 | 44.59 | 42.23 | 0.98 |

| Llama 3.1-70B (MetaAI, 2024) | 42.78 | 43.19 | 42.70 | 2.60 |

| Qwen 2.5-72B (Qwen Team, 2024) | 42.74 | 43.80 | 42.05 | 1.21 |

| Closed-source LLMs | ||||

| Gemini 1.5 Pro (Anil et al., 2023) | 48.75 | 43.97 | 55.08 | 5.88 |

| Claude 3.5 sonnet (Anthropic, 2024a) | 47.85 | 41.97 | 56.00 | 3.91 |

| GPT-4 (OpenAI et al., 2023) | 47.66 | 42.15 | 55.19 | 5.31 |

| GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024a) | 47.73 | 42.09 | 55.48 | 5.95 |

| o1-preview (OpenAI, 2024b) | 48.62 | 42.54 | 57.08 | 5.63 |

| LLM Agent Framework | ||||

| AI-SCI (GPT-4o) (Lu et al., 2024) | 45.05 | 40.02 | 51.91 | 2.23 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the PAPERWEAKNESS task, a subtask within the AAAR-1.0 benchmark dataset. The task involves identifying weaknesses in research papers. The table shows the performance metrics for several open-source and closed-source LLMs, including SN-F1 score (a harmonic mean of SN-Precision and SN-Recall), SN-Precision, SN-Recall and ITF-IDF (Inverse Text Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency), a metric measuring weakness diversity. The results indicate the ability of different LLMs to identify and characterize weaknesses effectively, with closed-source models generally outperforming open-source models.

read the caption

Table 6: Various LLMs’ performances on the 993 instances of Weakness.

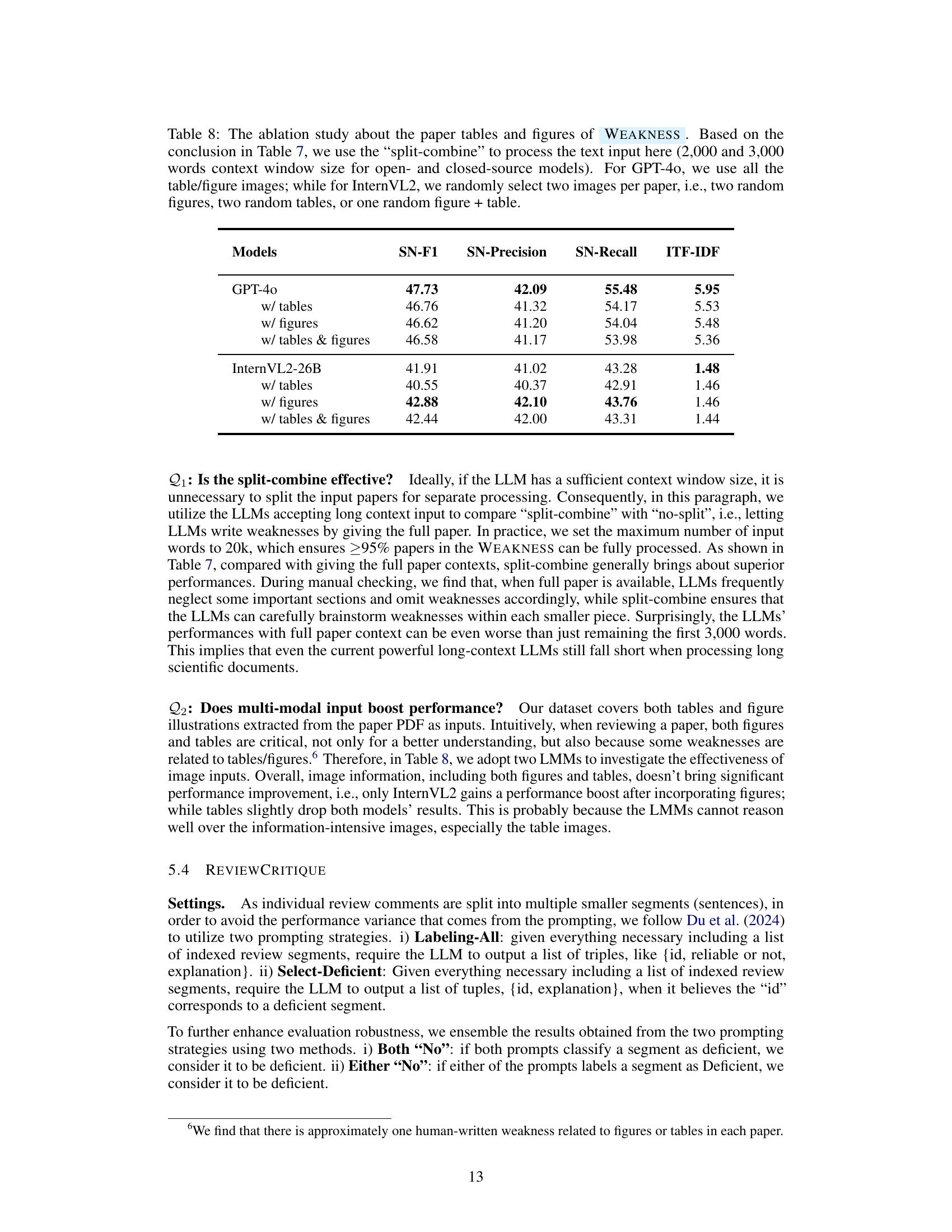

| Models | Input Context | Processing | Window Size (in words) | SN-F1 | SN-Precision | SN-Recall | ITF-IDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4-Turbo | split-combine | 3,000 | 47.66 | 42.15 | 55.19 | 5.31 | |

| no-split | 3,000 | 45.80 | 43.66 | 48.39 | 5.58 | ||

| no-split | 20,000 | 44.99 | 42.64 | 47.82 | 5.58 | ||

| GPT-4o | split-combine | 3,000 | 47.73 | 42.09 | 55.48 | 5.95 | |

| no-split | 3,000 | 45.74 | 43.45 | 48.54 | 5.92 | ||

| no-split | 20,000 | 45.47 | 42.97 | 48.51 | 6.02 | ||

| AI-SCI | split-combine | 3,000 | 45.05 | 40.02 | 51.91 | 2.23 | |

| no-split | 3,000 | 42.56 | 40.90 | 44.65 | 2.53 | ||

| no-split | 20,000 | 42.53 | 40.75 | 44.78 | 2.58 |

🔼 Table 7 compares the performance of different input processing methods for the WEAKNESS task using GPT-40, GPT-4-Turbo, and AI-SCI. It contrasts two methods: ‘split-combine’, which divides the input paper into smaller chunks (specified by a ‘window size’), and ’no-split’, which uses the entire paper (up to 20,000 words, covering 95% of papers). The table shows how each method’s performance varies with different window sizes. This allows analysis of whether splitting the paper into smaller parts for processing improves model performance on this task.

read the caption

Table 7: The performance comparison of different input processing methods for Weakness. We use GPT-4o and GPT-4-Turbo because both accept a maximum of 128k tokens input. We also put the results of AI-SCI in the table for reference. Here, “split-combine” splits the input paper into several pieces, where each piece’s length is denoted as “window size”; “no-split” means the conventional input cutting, for example, if the window size is 3,000, then only the first 3,000 words in the paper are used. According to the data statistics, 20,000 words can cover maximum lengths of more than 95% of the papers in our dataset.

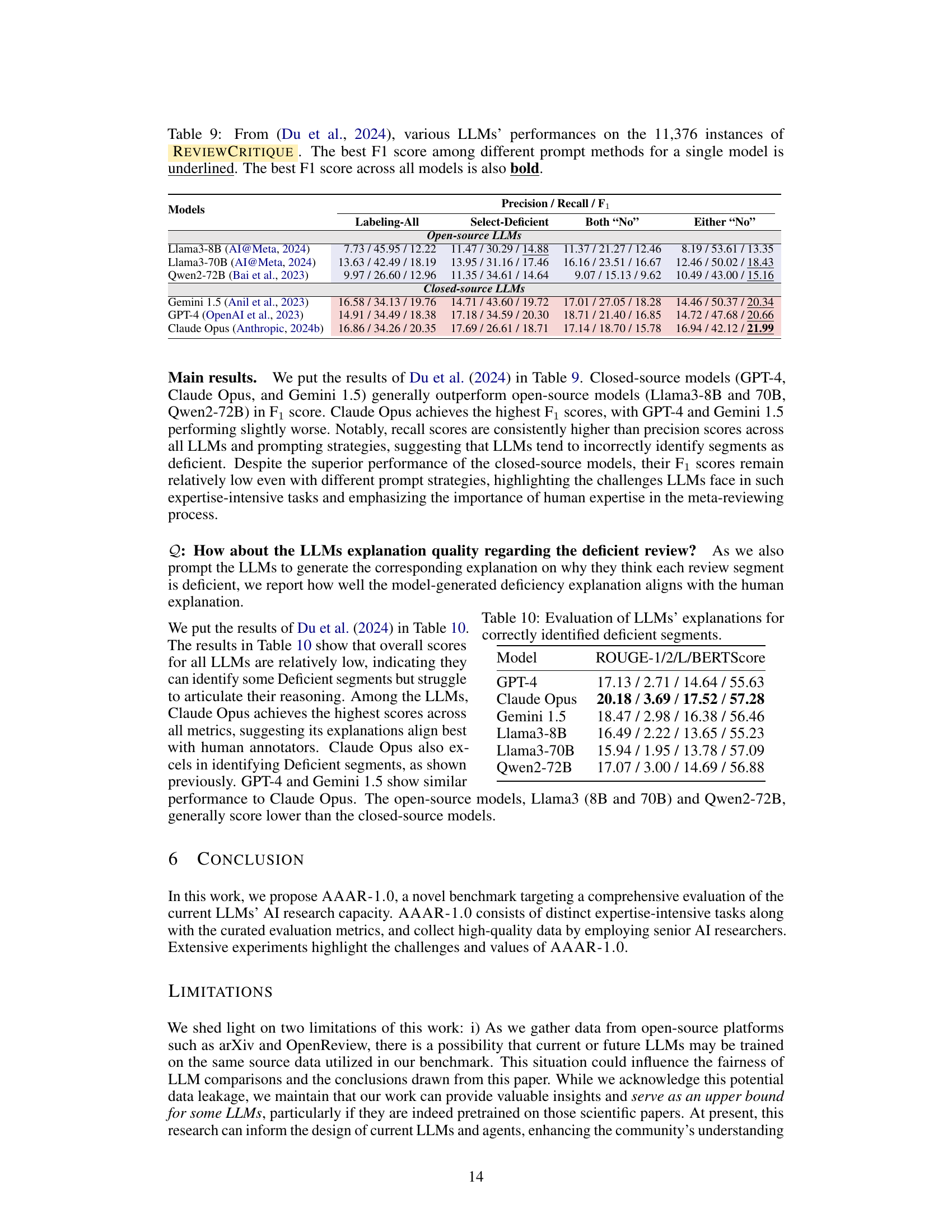

| Models | SN-F1 | SN-Precision | SN-Recall | ITF-IDF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | 47.73 | 42.09 | 55.48 | 5.95 | |

| w/ tables | 46.76 | 41.32 | 54.17 | 5.53 | |

| w/ figures | 46.62 | 41.20 | 54.04 | 5.48 | |

| w/ tables & figures | 46.58 | 41.17 | 53.98 | 5.36 | |

| InternVL2-26B | 41.91 | 41.02 | 43.28 | 1.48 | |

| w/ tables | 40.55 | 40.37 | 42.91 | 1.46 | |

| w/ figures | 42.88 | 42.10 | 43.76 | 1.46 | |

| w/ tables & figures | 42.44 | 42.00 | 43.31 | 1.44 |

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the impact of using tables and figures as input to the WEAKNESS task. Building upon the findings from Table 7, which examined different input processing methods, this experiment uses the ‘split-combine’ method for text processing, with context windows of 2000 and 3000 words for open and closed-source language models, respectively. For GPT-40, all available table and figure images are used, while InternVL2 uses two randomly selected images per paper (either two figures, two tables, or one of each). The results show the impact of including visual information on the model’s performance in identifying weaknesses in research papers.

read the caption

Table 8: The ablation study about the paper tables and figures of Weakness. Based on the conclusion in Table 7, we use the “split-combine” to process the text input here (2,000 and 3,000 words context window size for open- and closed-source models). For GPT-4o, we use all the table/figure images; while for InternVL2, we randomly select two images per paper, i.e., two random figures, two random tables, or one random figure + table.

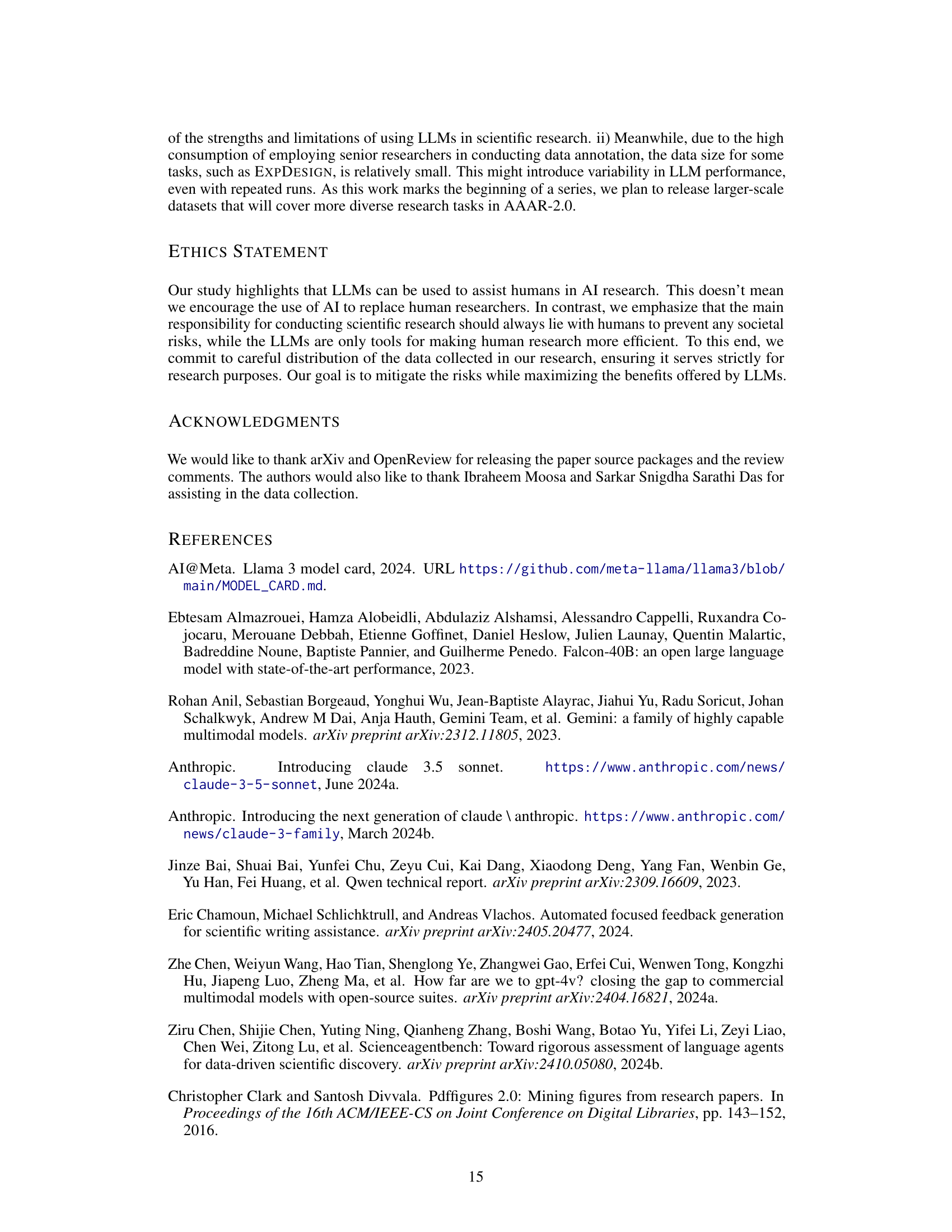

| Models | Labeling-All | Select-Deficient | Both “No” | Either “No” |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-source LLMs | ||||

| Llama3-8B (AI@Meta, 2024) | 7.73 / 45.95 / 12.22 | 11.47 / 30.29 / 14.88 | 11.37 / 21.27 / 12.46 | 8.19 / 53.61 / 13.35 |

| Llama3-70B (AI@Meta, 2024) | 13.63 / 42.49 / 18.19 | 13.95 / 31.16 / 17.46 | 16.16 / 23.51 / 16.67 | 12.46 / 50.02 / 18.43 |

| Qwen2-72B (Bai et al., 2023) | 9.97 / 26.60 / 12.96 | 11.35 / 34.61 / 14.64 | 9.07 / 15.13 / 9.62 | 10.49 / 43.00 / 15.16 |

| Closed-source LLMs | ||||

| Gemini 1.5 (Anil et al., 2023) | 16.58 / 34.13 / 19.76 | 14.71 / 43.60 / 19.72 | 17.01 / 27.05 / 18.28 | 14.46 / 50.37 / 20.34 |

| GPT-4 (OpenAI et al., 2023) | 14.91 / 34.49 / 18.38 | 17.18 / 34.59 / 20.30 | 18.71 / 21.40 / 16.85 | 14.72 / 47.68 / 20.66 |

| Claude Opus (Anthropic, 2024b) | 16.86 / 34.26 / 20.35 | 17.69 / 26.61 / 18.71 | 17.14 / 18.70 / 15.78 | 16.94 / 42.12 / 21.99 |

🔼 Table 9 presents the performance evaluation results of various Large Language Models (LLMs) on the ReviewCritique dataset, which comprises 11,376 instances. The table showcases the F1 scores achieved by different LLMs using two distinct prompting strategies: Labeling-All and Select-Deficient, along with the results of combining these strategies using ‘Both No’ and ‘Either No’ methods. The best F1-score for each LLM across different prompt methods is underlined, with the overall best F1-score highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 9: From (Du et al., 2024), various LLMs’ performances on the 11,376 instances of ReviewCritique. The best F1 score among different prompt methods for a single model is underlined. The best F1 score across all models is also bold.

| Model | ROUGE-1/2/L/BERTScore |

|---|---|

| GPT-4 | 17.13 / 2.71 / 14.64 / 55.63 |

| Claude Opus | 20.18 / 3.69 / 17.52 / 57.28 |

| Gemini 1.5 | 18.47 / 2.98 / 16.38 / 56.46 |

| Llama3-8B | 16.49 / 2.22 / 13.65 / 55.23 |

| Llama3-70B | 15.94 / 1.95 / 13.78 / 57.09 |

| Qwen2-72B | 17.07 / 3.00 / 14.69 / 56.88 |

🔼 This table presents the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, ROUGE-L, and BERTScore scores for the Large Language Models’ (LLMs) explanations of correctly identified deficient review segments. It evaluates the quality of the LLMs’ explanations, comparing them to human-generated explanations. The higher the score, the better the LLM’s explanation aligns with human judgments.

read the caption

Table 10: Evaluation of LLMs’ explanations for correctly identified deficient segments.

| # of classification instances | 1,049 | |

|---|---|---|

| # of source papers | 869 | |

ave. “left” input context length (in words) | 4,377 | |

ave. “right” input context length (in words) | 6,362 | |

max “left” input context length (in words) | 24,849 | |

max “right” input context length (in words) | 32,948 | |

min “left” input context length (in words) | 711 | |

min “right” input context length (in words) | 8 | |

ave. “pos.” output equation length (in character) | 55 | |

ave. “neg.” output equation length (in character) | 48 | |

max “pos.” output equation length (in character) | 1,039 | |

max “neg.” output equation length (in character) | 306 | |

min “pos.” output equation length (in character) | 6 | |

min “neg.” output equation length (in character) | 4 |

🔼 Table 11 presents a statistical overview of the Equation Inference (EQINFER) dataset used in the AAAR-1.0 benchmark. It details the average and maximum lengths of the text before and after the equation in the original papers (the input ‘context’), as well as the lengths of the correct equations (the ‘ground truth’ or ‘pos.’) and the incorrect, synthetically generated equations used as negative examples (’neg.’). This data is crucial in understanding the scale and complexity of the task that the LLMs are expected to complete.

read the caption

Table 11: The statistics of EqInfer. Here, the “left” and “right” input context indicates the paper contexts \ulbefore and \ulafter the missed equation; “pos.” means the ground-truth equations (written by the source paper authors), while “neg.” is the GPT4-synthetic wrong equations.

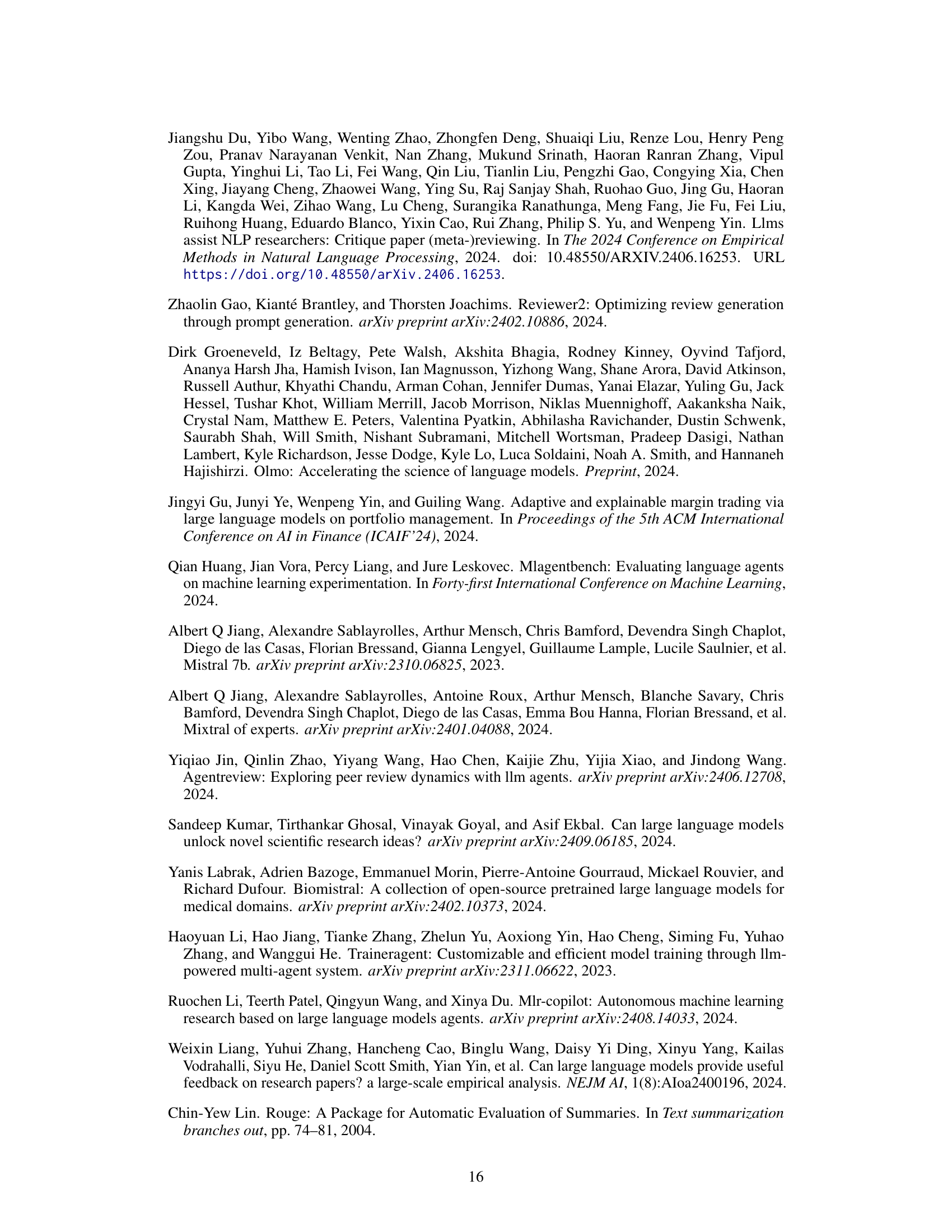

🔼 Table 12 presents a statistical overview of the dataset used for the Experiment Design task within the AAAR-1.0 benchmark. It details the number of instances and source papers, along with the average, maximum, and minimum lengths of the input context (in words), the number of input figures, the average and range of lengths for experiment explanations and descriptions, and the overall lengths of the combined experiment and explanation lists.

read the caption

Table 12: The statistics of ExpDesign.

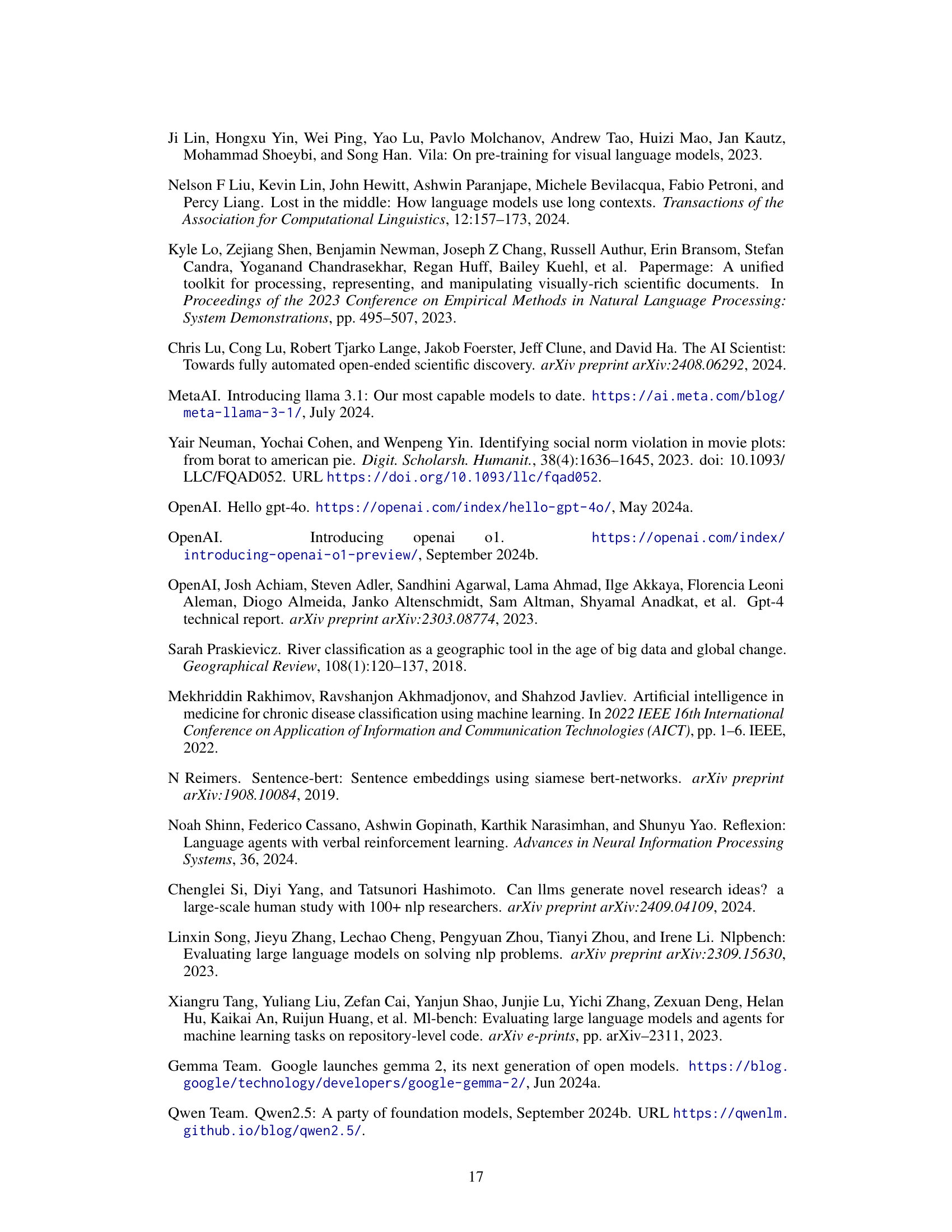

🔼 Table 13 presents a detailed statistical overview of the WEAKNESS dataset used in the AAAR-1.0 benchmark. It includes counts of instances, source papers, and associated data points such as input context length (in words), the number of figures and tables, the number of reviewers per paper, the number of weaknesses identified per reviewer, and the average and maximum length of these weaknesses (in words). These statistics provide insights into the scale and characteristics of the dataset, which is crucial for understanding the complexity and scope of the LLM evaluation task.

read the caption

Table 13: The statistics of Weakness.

Full paper#