↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large generative models are powerful, but concerns about their reliability and potential misuse are growing. Current methods to control model outputs often involve computationally expensive fine-tuning which may negatively impact other model aspects. Inference-time interventions are a more desirable approach that avoids retraining the model, but existing methods often rely on simple heuristics.

This paper introduces Activation Transport (ACT), a general framework for controlling generative models by carefully manipulating their internal activations. ACT leverages optimal transport theory, a powerful mathematical tool that finds the most efficient way to map one probability distribution to another. The authors demonstrate ACT’s effectiveness and versatility across different model types and tasks, showing significant improvements in various metrics related to safety and control, surpassing several existing methods while preserving model capabilities.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on generative models due to its introduction of Activation Transport (ACT), a novel framework for controlling both language and diffusion models. ACT offers a computationally efficient and modality-agnostic solution to address critical issues such as toxicity, bias, and lack of control in these models. Its impact lies in improving the safety, reliability, and utility of large generative models, paving the way for more responsible and beneficial applications. Further research could explore ACT’s potential in other modalities or investigate advanced transport methods.

Visual Insights#

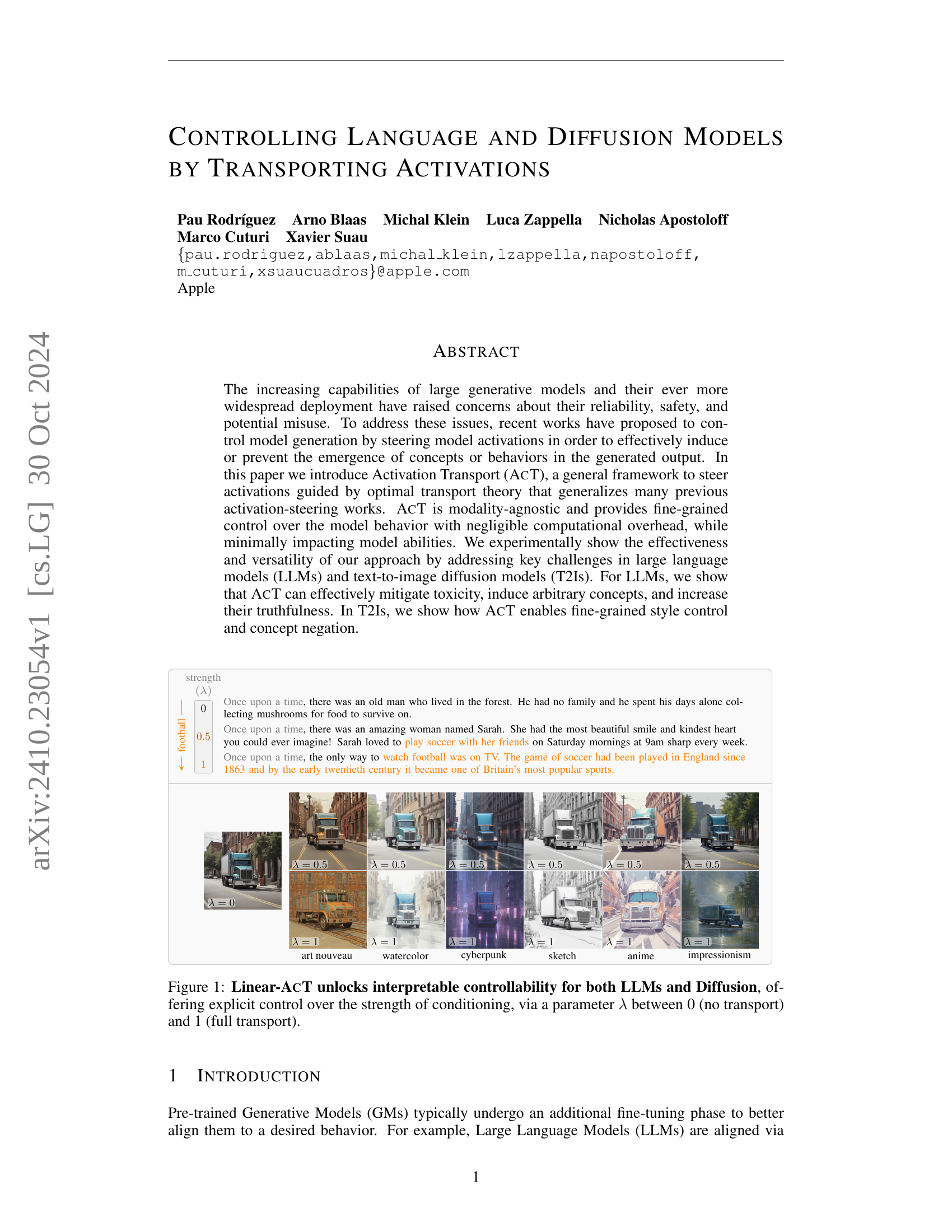

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of Linear-AcT in controlling both Large Language Models (LLMs) and diffusion models. The x-axis represents the strength of conditioning (lambda, λ), ranging from 0 (no conditioning) to 1 (full conditioning). For LLMs, the examples show how controlling activation can mitigate toxicity, induce specific concepts, and improve truthfulness. For diffusion models, it showcases fine-grained style control and concept negation. The images illustrate the interpretable control offered by Linear-AcT, allowing for a smooth transition between different outputs based on the lambda parameter.

read the caption

Figure 1: Linear-AcT unlocks interpretable controllability for both LLMs and Diffusion, offering explicit control over the strength of conditioning, via a parameter λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ between 0 (no transport) and 1 (full transport).

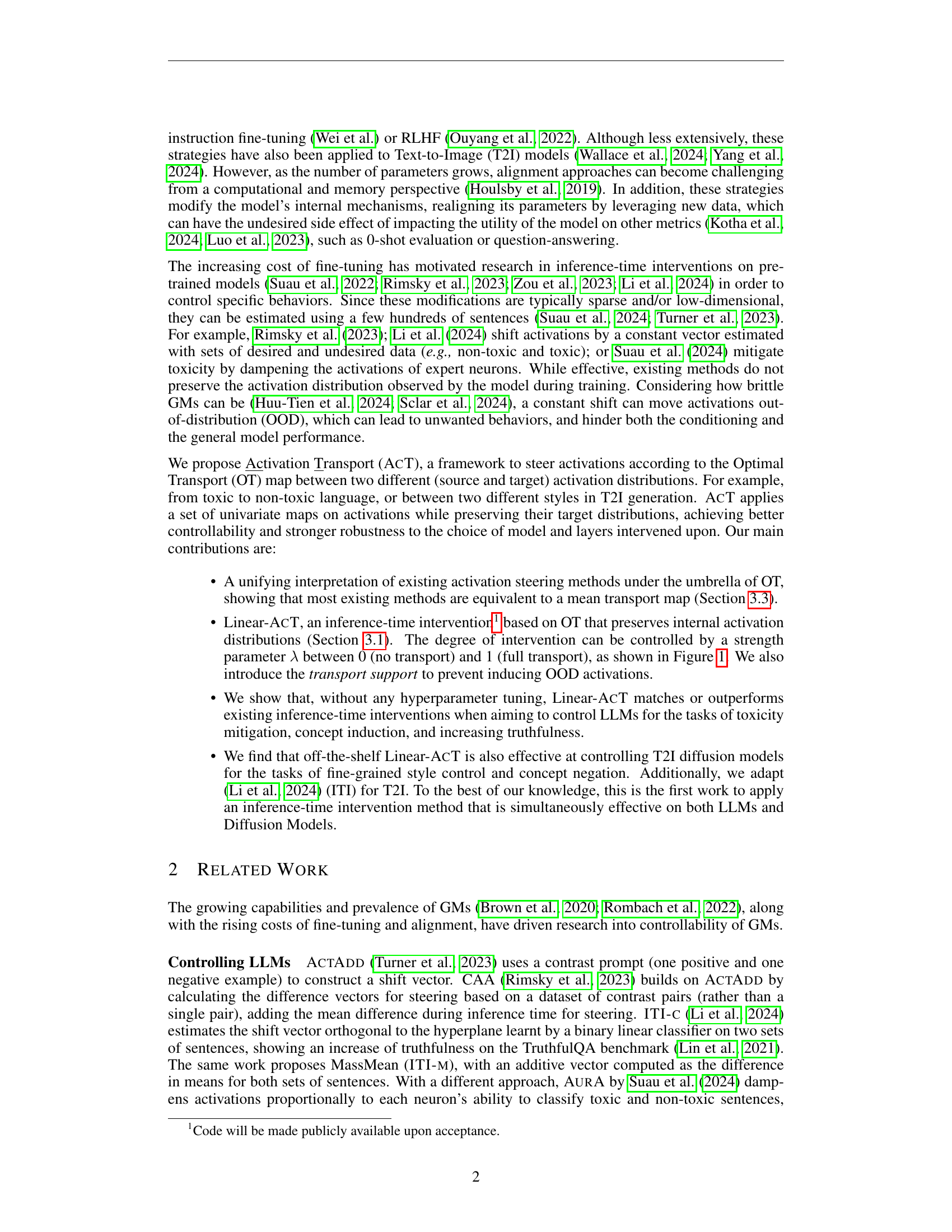

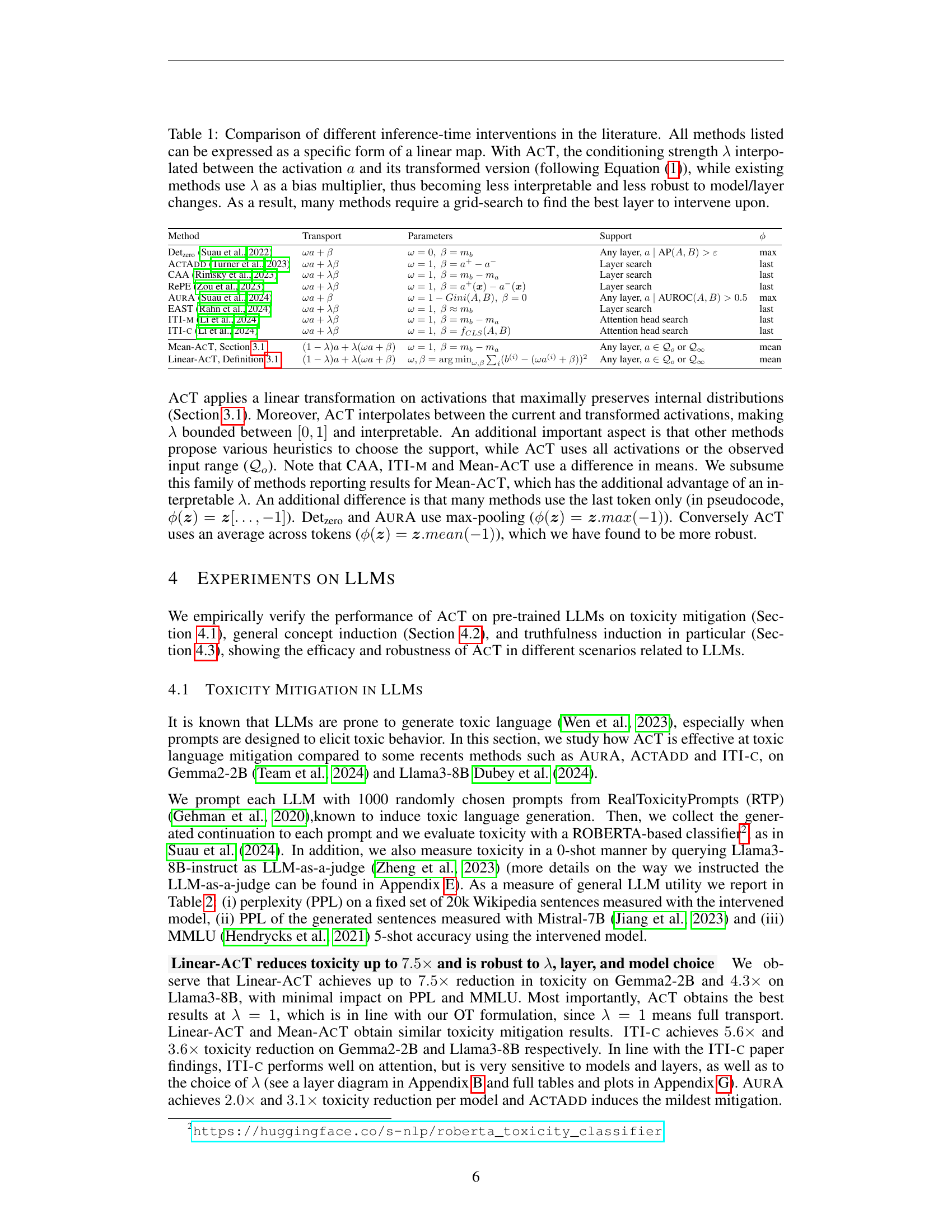

| Method | Transport | Parameters | Support | ϕ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detzero [Suau et al., 2022] | ωa+β | ω=0, β=mb | Any layer, {a∣AP(A,B)>ε} | max |

| ActAdd [Turner et al., 2023] | ωa+λβ | ω=1, β=a+-a- | Layer search | last |

| CAA [Rimsky et al., 2023] | ωa+λβ | ω=1, β=mb-ma | Layer search | last |

| RePE [Zou et al., 2023] | ωa+λβ | ω=1, β=a+(x)-a-(x) | Layer search | last |

| AurA [Suau et al., 2024] | ωa+β | ω=1-Gini(A,B), β=0 | Any layer, {a∣AUROC(A,B)>0.5} | max |

| EAST [Rahn et al., 2024] | ωa+λβ | ω=1, β≈mb | Layer search | last |

| ITI-m [Li et al., 2024] | ωa+λβ | ω=1, β=mb-ma | Attention head search | last |

| ITI-c [Li et al., 2024] | ωa+λβ | ω=1, β=fCLS(A,B) | Attention head search | last |

| Mean-AcT, Section 3.1 | (1-λ)a+λ(ωa+β) | ω=1, β=mb-ma | Any layer, a∈Qo or Q∞ | mean |

| Linear-AcT, Definition 3.1 | (1-λ)a+λ(ωa+β) | ω,β=argminω,β∑i(b(i)-(ωa(i)+β))2 | Any layer, a∈Qo or Q∞ | mean |

🔼 Table 1 compares several methods for controlling the behavior of large language models (LLMs) at inference time, without retraining. Most methods involve adding a bias vector to the model’s activations. This bias is often scaled by a parameter (lambda). However, this approach can make the effect of the parameter difficult to interpret, making model control less precise and more sensitive to the choice of layer and model architecture. AcT (Activation Transport), in contrast, uses optimal transport theory to create an interpolation map between the original and modified activation distributions, offering more fine-grained and interpretable control.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of different inference-time interventions in the literature. All methods listed can be expressed as a specific form of a linear map. With AcT, the conditioning strength λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ interpolated between the activation a𝑎aitalic_a and its transformed version (following Equation 1), while existing methods use λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ as a bias multiplier, thus becoming less interpretable and less robust to model/layer changes. As a result, many methods require a grid-search to find the best layer to intervene upon.

In-depth insights#

Activation Transport#

The concept of “Activation Transport” presents a novel approach to controlling generative models by manipulating their internal activations. Instead of retraining or fine-tuning, which can be computationally expensive and potentially disruptive to existing model capabilities, Activation Transport leverages optimal transport theory to directly guide activations towards a desired distribution. This offers fine-grained control with minimal computational overhead. By viewing model activations as probability distributions, the method maps existing activations onto target distributions, effectively steering model behavior. The approach is modality-agnostic, working effectively across language and image models, showcasing its versatility and broad applicability. Linear-ACT, a specific implementation, utilizes a computationally efficient affine transport map, demonstrating effectiveness in various tasks. This is particularly noteworthy as it’s shown to outperform or match previous methods with negligible computational overhead, making it a more practical and scalable solution for controlling large generative models.

Optimal Transport Maps#

Optimal transport (OT) maps offer a powerful framework for aligning probability distributions. In the context of generative models, OT maps can elegantly steer model activations, effectively controlling the generation process. A key advantage of using OT is its ability to preserve the underlying distribution of activations, preventing out-of-distribution artifacts that can hinder model performance. By mapping activations from a source distribution (e.g., representing undesirable model outputs) to a target distribution (representing desired outputs), OT can subtly alter the model’s behavior without significant computational overhead. This technique is particularly valuable in dealing with high-dimensional data, typical in large language and diffusion models, where traditional methods might struggle. The choice of OT cost function significantly impacts the resulting map, influencing the type and magnitude of changes imposed on the activations. Furthermore, the computational cost of calculating and applying OT maps remains a challenge, making efficient approximations, like the linear approximations presented in this paper, essential for practical implementation in real-time applications.

Linear-ACT Control#

Linear-ACT Control, as a proposed method, presents a novel approach to controlling generative models by manipulating their internal activations. It leverages optimal transport theory for fine-grained and interpretable control, offering a significant advantage over prior methods that often rely on heuristic adjustments or lack transparency. The linearity of the approach ensures computational efficiency, making it scalable for large models, while the use of optimal transport ensures the preservation of activation distributions, leading to robustness and preventing out-of-distribution behaviors. The parameter λ provides an interpretable control knob, allowing users to precisely modulate the strength of the intervention. This modality-agnostic nature extends its application to both language and diffusion models, successfully addressing challenges in toxicity mitigation, concept induction, style control, and concept negation. Linear-ACT’s effectiveness across diverse tasks and model architectures highlights its potential as a versatile and powerful tool for controlling generative model behavior. However, the assumption of linearity may limit its ability to handle complex, multi-modal distributions, representing a key area for future research.

Diffusion Model Control#

Controlling diffusion models presents a unique challenge due to their intricate generative process. Inference-time methods are particularly attractive as they avoid the computational cost of fine-tuning. The paper explores the use of optimal transport (OT) to guide the model’s activations towards a desired state, offering a unified framework for various control mechanisms. Linear-ACT, a computationally efficient instantiation of this framework, demonstrates impressive results in both fine-grained style control and concept negation within image generation. This approach showcases its adaptability by effectively leveraging the structure of the model’s activations to achieve more precise control with minimal overhead. While the paper presents promising findings, further exploration is needed to analyze its limitations and scalability for exceptionally large models. The core contribution lies in the generalizability of OT for diffusion model control, offering a robust alternative to existing, often less interpretable methods.

Future of ACT#

The future of Activation Transport (ACT) looks promising, particularly given its demonstrated efficacy and versatility across diverse generative models. Further research should explore the application of ACT to even more complex and challenging tasks, such as controlling the generation of long, coherent narratives in LLMs or generating highly detailed and realistic images with intricate details in diffusion models. Expanding ACT to handle multimodal inputs and outputs would be another important direction, enabling more sophisticated control over content creation that incorporates different modalities of data simultaneously. Investigating the theoretical underpinnings of ACT within the broader context of optimal transport and exploring alternative transport algorithms could lead to further improvements in efficiency and robustness. Addressing potential ethical concerns related to misuse is crucial; robust safety mechanisms and careful consideration of societal impact must accompany future advancements. Ultimately, the potential of ACT to provide fine-grained, interpretable control over generative models could revolutionize several applications across various domains, from content creation and scientific research to game development and robotics, but this potential must be harnessed responsibly.

More visual insights#

More on figures

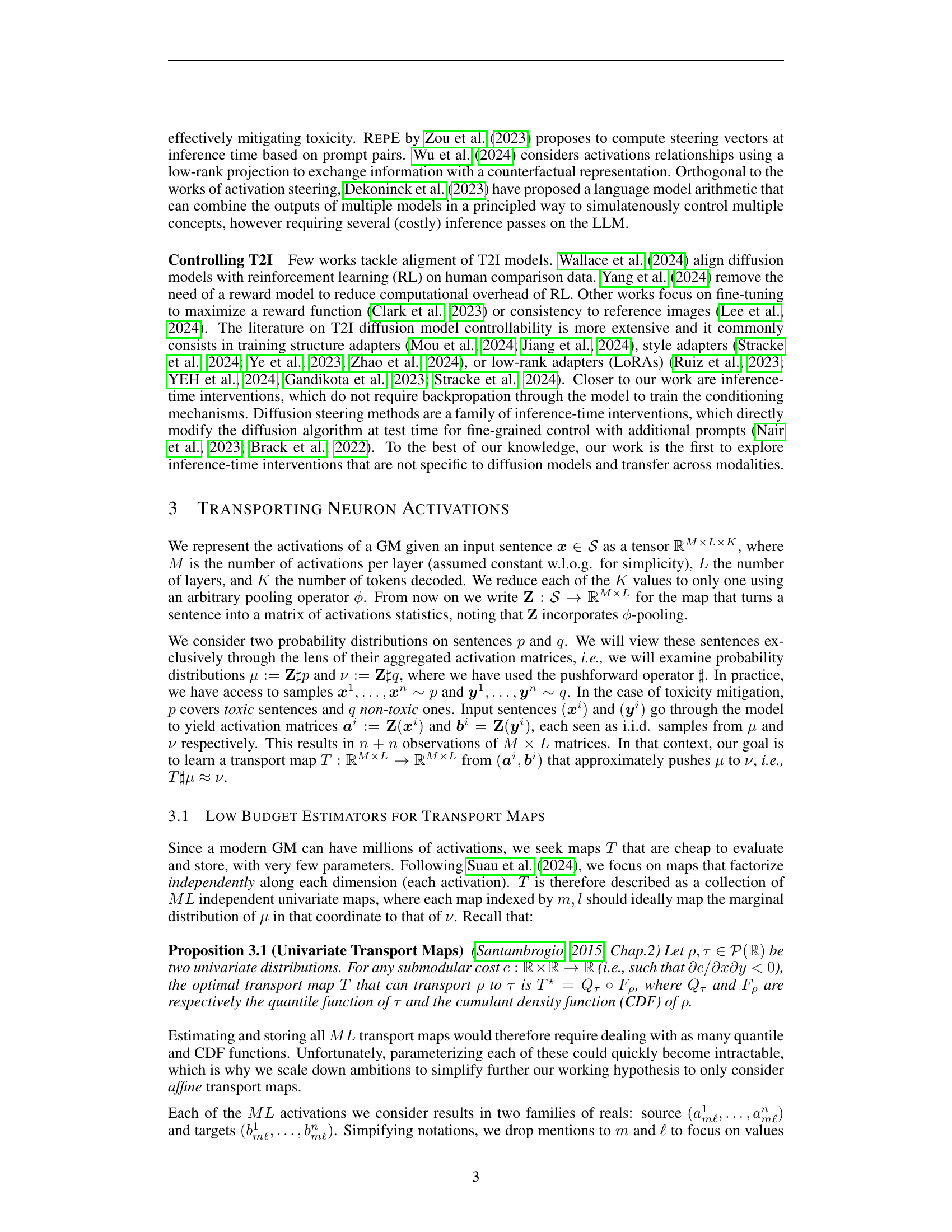

🔼 Figure 2 illustrates the effects of different methods for generating transport maps between two distributions. When the standard deviations of the two distributions are equal (σa = σb), most methods produce similar maps. However, when the standard deviations differ (σa ≠ σb), vector-based methods (like ActAdd, ITI-c, and Mean-AcT) deviate significantly from the optimal map determined by the data samples. This is because vector-based methods rely on simple shifts, whereas the optimal map often requires more complex transformations. ActAdd exhibits an additional bias stemming from its use of only a single sample pair in its calculations. In contrast, the linear estimator used in the paper shows robustness, producing accurate maps regardless of differences in standard deviation between the distributions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Transport maps using different methods. For distributions with σa=σbsubscript𝜎𝑎subscript𝜎𝑏\sigma_{a}=\sigma_{b}italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_a end_POSTSUBSCRIPT = italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_b end_POSTSUBSCRIPT (left) all methods (except ActAdd) are equivalent. When σa≠σbsubscript𝜎𝑎subscript𝜎𝑏\sigma_{a}\neq\sigma_{b}italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_a end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ≠ italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_b end_POSTSUBSCRIPT (right), vector-based methods (e.g., ActAdd, ITI-c, Mean-AcT) diverge from the map defined by the samples. ActAdd shows a bias since it only uses one sample pair. The linear estimator is robust to differences in σ𝜎\sigmaitalic_σ.

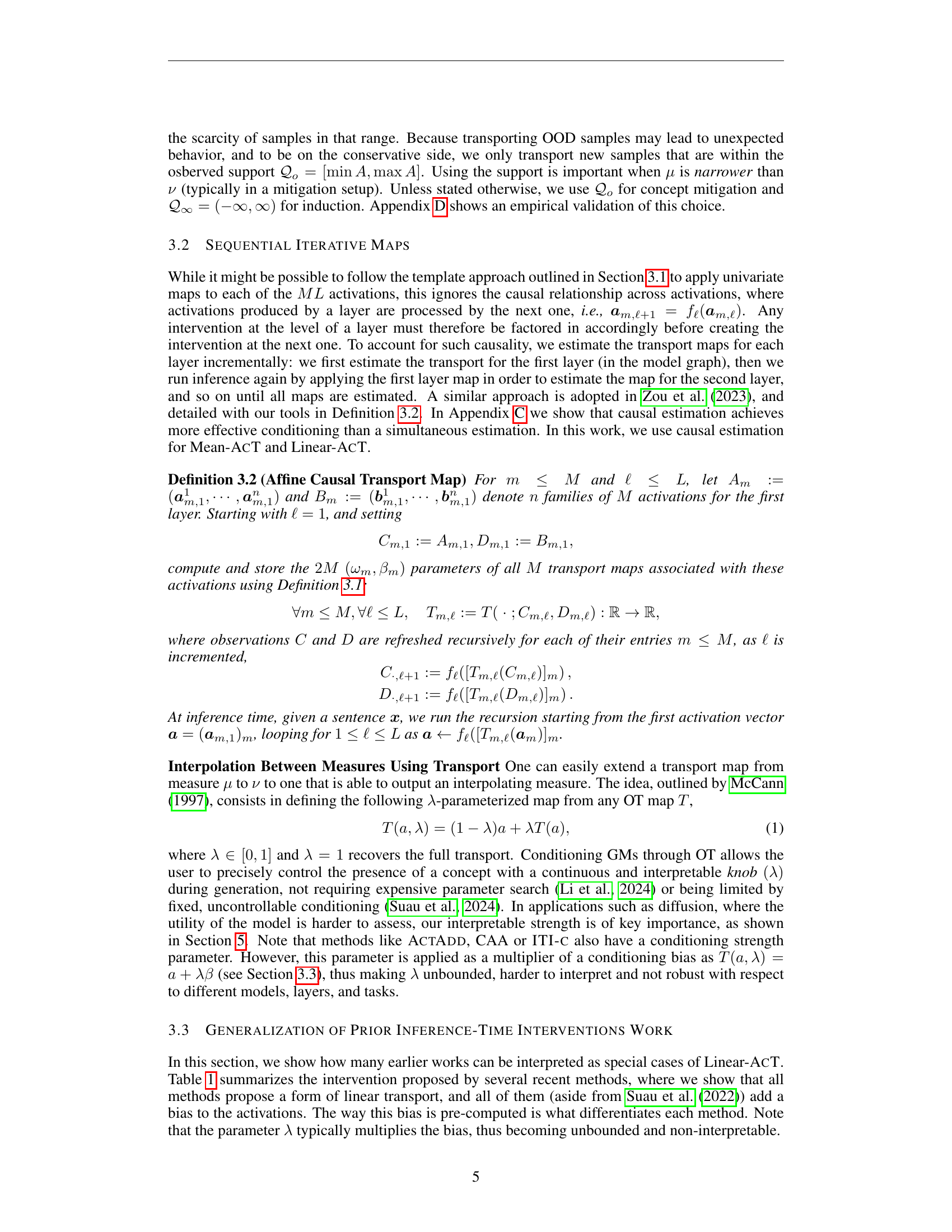

🔼 The figure is a scatter plot showing the relationship between the standard deviations of activations for toxic and non-toxic sentences in the Gemma2-2B language model. The x-axis represents the standard deviation of activations for toxic sentences (σa), and the y-axis represents the standard deviation of activations for non-toxic sentences (σb). Each point in the scatter plot represents a sentence, with its x and y coordinates corresponding to the standard deviations of its activations. The plot visually demonstrates that the standard deviations of activations for toxic and non-toxic sentences are significantly different (σa ≠ σb), indicating that the model processes toxic and non-toxic sentences differently.

read the caption

Figure 3: Actual σa,σbsubscript𝜎𝑎subscript𝜎𝑏\sigma_{a},\sigma_{b}italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_a end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_b end_POSTSUBSCRIPT for toxic and non-toxic sentences on Gemma2-2B, showing that σa≠σbsubscript𝜎𝑎subscript𝜎𝑏\sigma_{a}\neq\sigma_{b}italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_a end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ≠ italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_b end_POSTSUBSCRIPT in real scenarios.

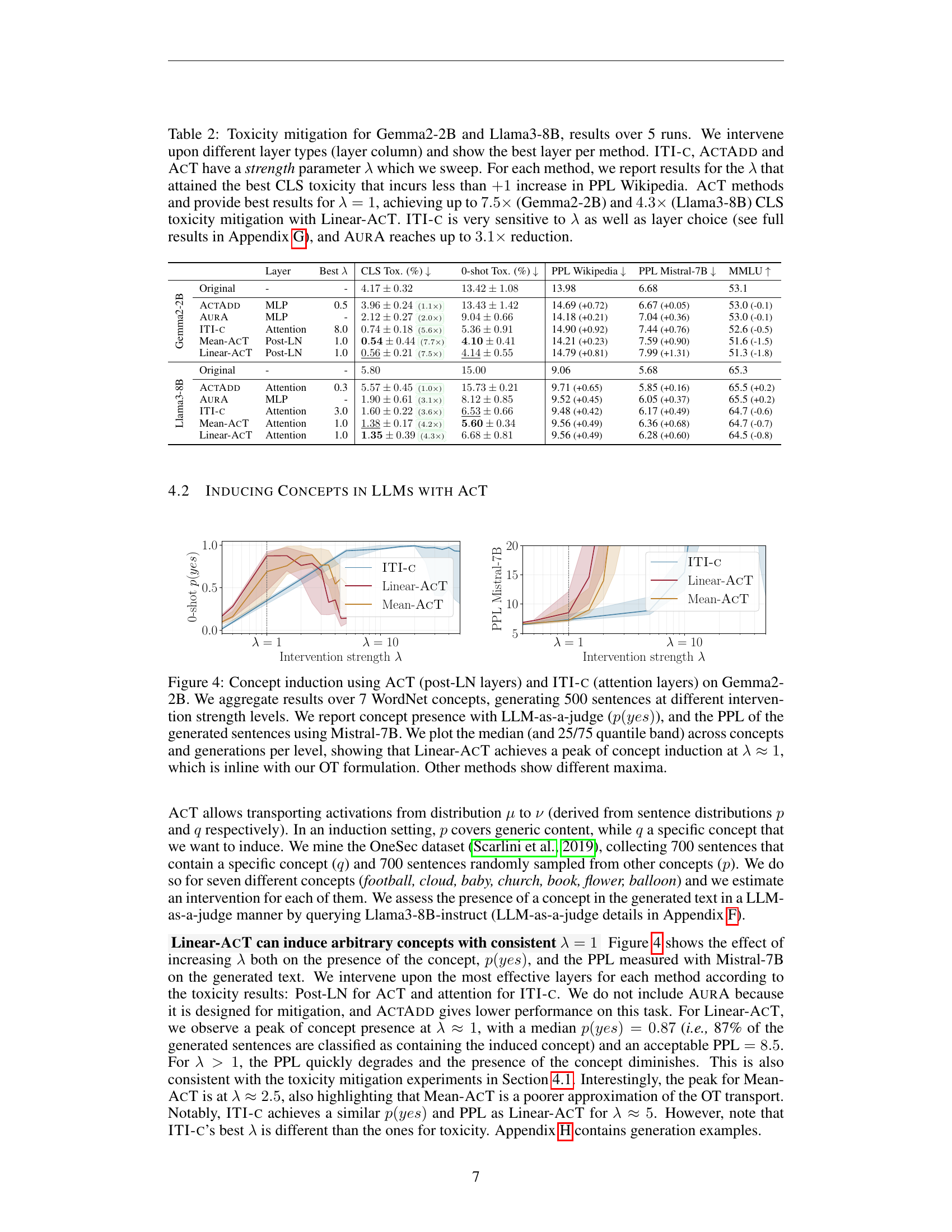

🔼 Figure 4 presents the results of concept induction experiments using three different methods: Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C. The experiments were performed on the Gemma2-2B large language model. Seven WordNet concepts were selected, and for each, 500 sentences were generated at various intervention strength levels (λ). The intervention strength controls the degree to which the model’s activations are steered towards inducing the desired concept. The results show the probability of the generated sentences containing the target concept (p(yes)) as measured by an LLM-as-a-judge, as well as the perplexity (PPL) of the generated sentences as calculated using Mistral-7B. The median and 25th/75th percentile ranges of the results are plotted against the intervention strength (λ). Notably, Linear-ACT shows a peak induction at λ ≈ 1, aligning with the optimal transport theory underpinning the approach, while the other methods show different optimal intervention strengths.

read the caption

Figure 4: Concept induction using AcT (post-LN layers) and ITI-c (attention layers) on Gemma2-2B. We aggregate results over 7 WordNet concepts, generating 500 sentences at different intervention strength levels. We report concept presence with LLM-as-a-judge (p(yes)𝑝𝑦𝑒𝑠p(yes)italic_p ( italic_y italic_e italic_s )), and the PPL of the generated sentences using Mistral-7B. We plot the median (and 25/75 quantile band) across concepts and generations per level, showing that Linear-AcT achieves a peak of concept induction at λ≈1𝜆1\lambda\approx 1italic_λ ≈ 1, which is inline with our OT formulation. Other methods show different maxima.

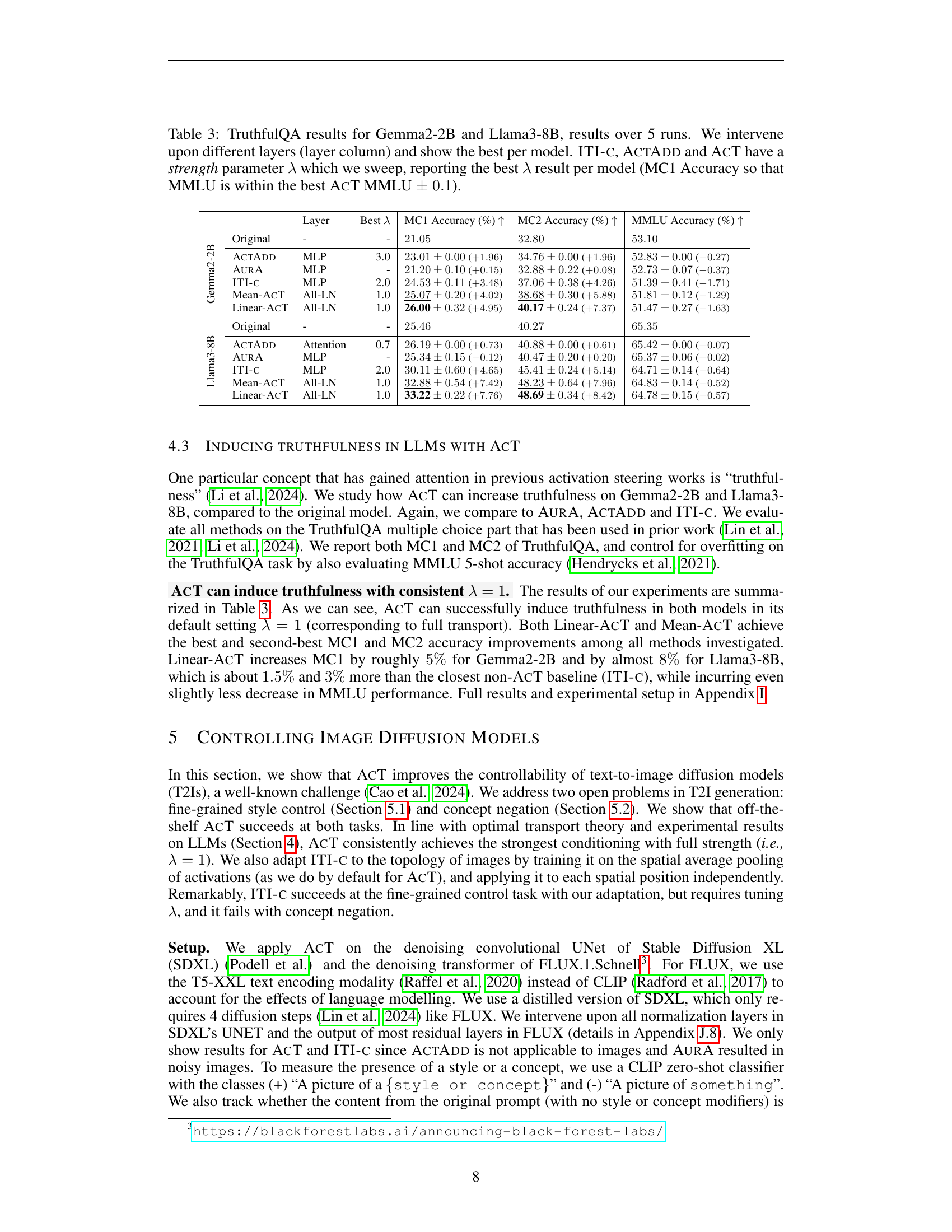

🔼 Figure 5 presents a comparison of three different methods (ITI-c, Mean-AcT, and Linear-AcT) for controlling the style of images generated by two different models (SDXL and FLUX). The prompt used is: “A cat resting on a laptop keyboard in a bedroom.” Each method is applied to incorporate the concept of ‘cyberpunk’ into the generated images. The strength of the cyberpunk style is controlled by a parameter, lambda (λ), that increases from 0 to 1 (0 being no effect, and 1 being full strength). The figure shows a sequence of generated images for each method, demonstrating the degree of cyberpunk influence. The best-performing lambda value for each method (determined by a 0-shot classifier assessment shown in Figure 6) is also indicated. The caption highlights that Linear-AcT provides the best balance between incorporating the cyberpunk style and maintaining the original meaning of the prompt.

read the caption

Figure 5: Linear-AcT allows controlled conditioning of SDXL and FLUX. “A cat resting on a laptop keyboard in a bedroom.” SDXL (left) and FLUX (right) intervened with ITI-c (top), Mean-AcT (middle) and Linear-AcT (bottom) respectively for the concept cyberpunk, with strength increasing from 0 and 1. We also show the image at the best λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ according to the highest 0-shot score in Figure 6. Qualitatively, Linear-AcT shows the best trade-off between cyberpunk style increase and prompt semantics preservation.

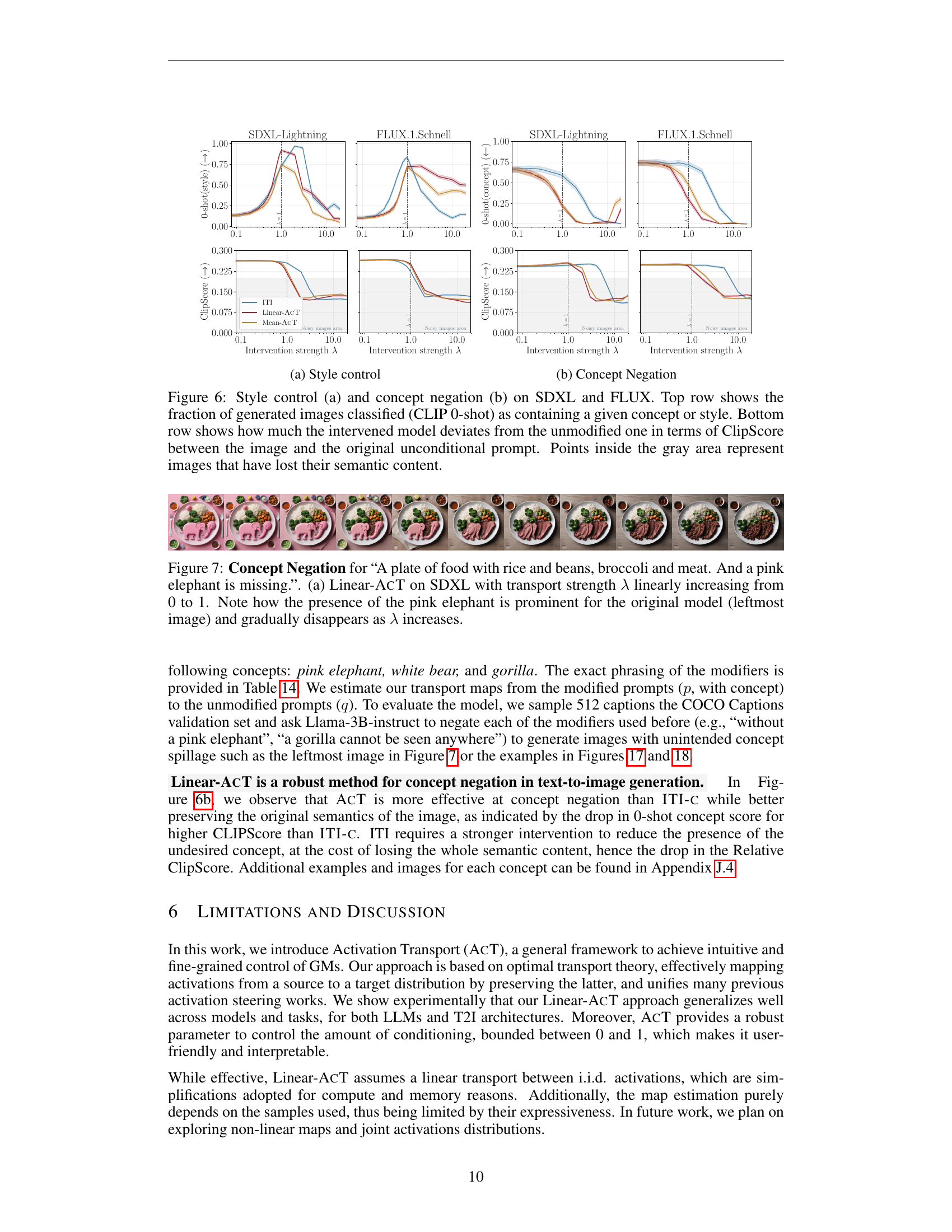

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to control the style of images generated by SDXL and FLUX diffusion models. The x-axis represents the intervention strength (λ), ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 means no intervention and 1 means full intervention. The y-axis represents either the fraction of generated images classified as having the target style (top row) or the CLIP score measuring similarity between generated and original images (bottom row). The results show that Linear-ACT generally provides the best trade-off between inducing the target style and maintaining the semantic content of the original prompt.

read the caption

(a) Style control

🔼 This figure shows the results of concept negation experiments on both SDXL and FLUX models. It demonstrates the effectiveness of Linear-ACT in removing unwanted concepts from generated images. The top row displays the fraction of images correctly identified (using a CLIP zero-shot classifier) as not containing the negated concept (pink elephant, white bear, or gorilla). The bottom row visually shows how much the modified images deviate from the original images (based on CLIPScore), indicating that Linear-ACT successfully removes unwanted concepts while maintaining semantic coherence. The gray area indicates that the images have lost semantic content.

read the caption

(b) Concept Negation

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comprehensive analysis of style control and concept negation techniques applied to Stable Diffusion XL (SDXL) and FLUX image generation models. The top row displays the effectiveness of these techniques, showing the percentage of generated images successfully incorporating a given style or concept, as measured by CLIP 0-shot classification. The bottom row illustrates the impact on image semantics by quantifying the deviation between the generated images and the original prompt using CLIPScore. Images falling within the gray area indicate a significant loss of semantic meaning due to the intervention.

read the caption

Figure 6: Style control (a) and concept negation (b) on SDXL and FLUX. Top row shows the fraction of generated images classified (CLIP 0-shot) as containing a given concept or style. Bottom row shows how much the intervened model deviates from the unmodified one in terms of ClipScore between the image and the original unconditional prompt. Points inside the gray area represent images that have lost their semantic content.

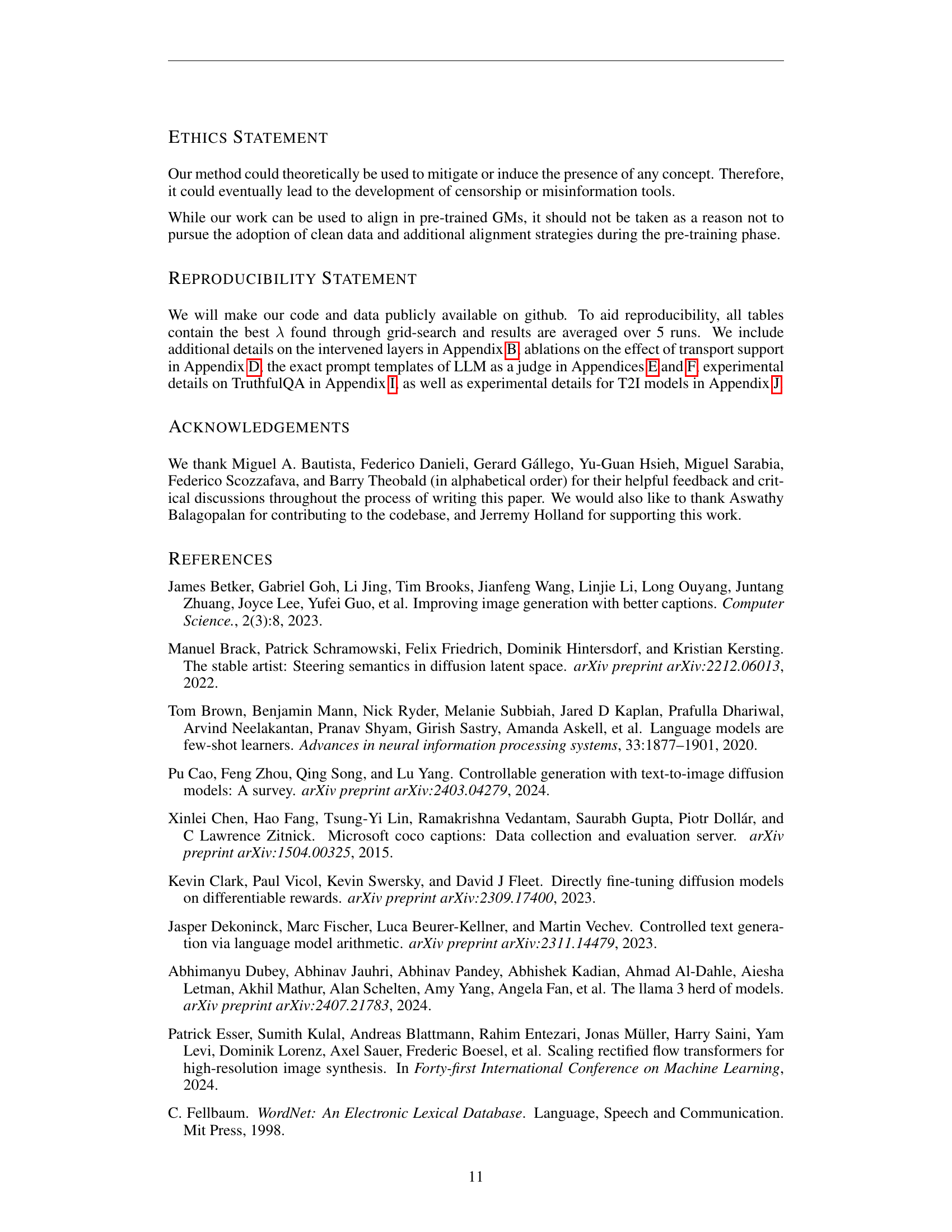

🔼 This figure demonstrates the concept negation capability of Linear-ACT on Stable Diffusion XL (SDXL). The input prompt requests an image of a plate of food with various items, specifically omitting a pink elephant. The figure shows a series of images generated by Linear-ACT, with the transport strength (lambda) increasing from 0 to 1. When lambda is 0, the image includes a pink elephant. As lambda increases, the presence of the pink elephant gradually diminishes until it’s completely absent at lambda = 1, showcasing Linear-ACT’s ability to effectively remove unwanted elements from generated images.

read the caption

Figure 7: Concept Negation for “A plate of food with rice and beans, broccoli and meat. And a pink elephant is missing.”. (a) Linear-AcT on SDXL with transport strength λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ linearly increasing from 0 to 1. Note how the presence of the pink elephant is prominent for the original model (leftmost image) and gradually disappears as λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ increases.

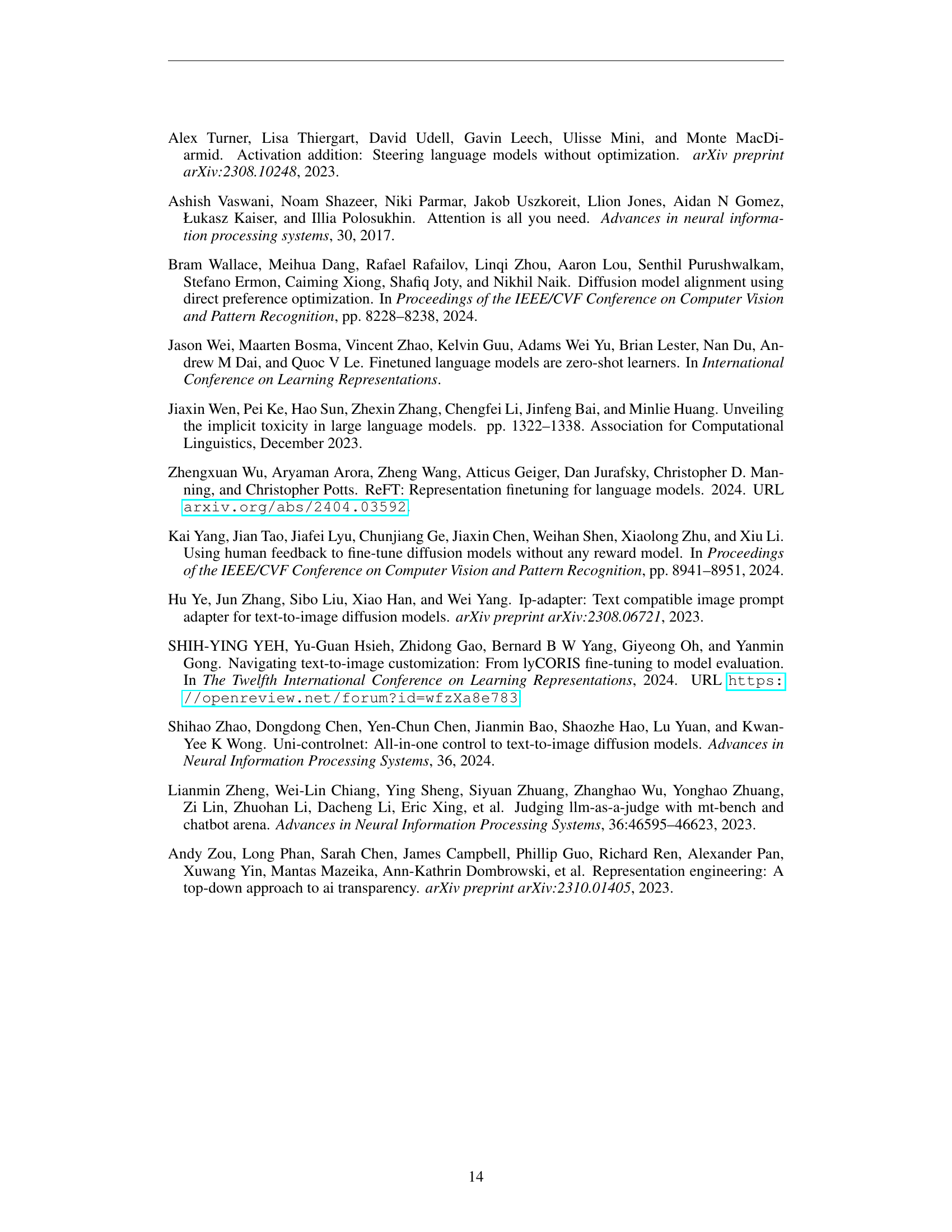

🔼 Figure 8 provides a detailed illustration of the architecture of a Transformer block within the Gemma2-2B large language model (LLM). It highlights the sequence of layers, including the pre-norm (Pre-Norm), linear transformation (Linear), attention mechanism (Attention), post-norm (Post-LN), and pooling layers (Pool). The figure aids in understanding the flow of activations and processing steps within the model. It also notes that the Llama3-8B model shares a similar structure, but notably lacks the Post-LN layers present in Gemma2-2B.

read the caption

Figure 8: Schema of a Transformer block of Gemma2-2B with the layer names as referenced in this work. Note that Llama3-8B has a similar structure without the Post-LN layers.

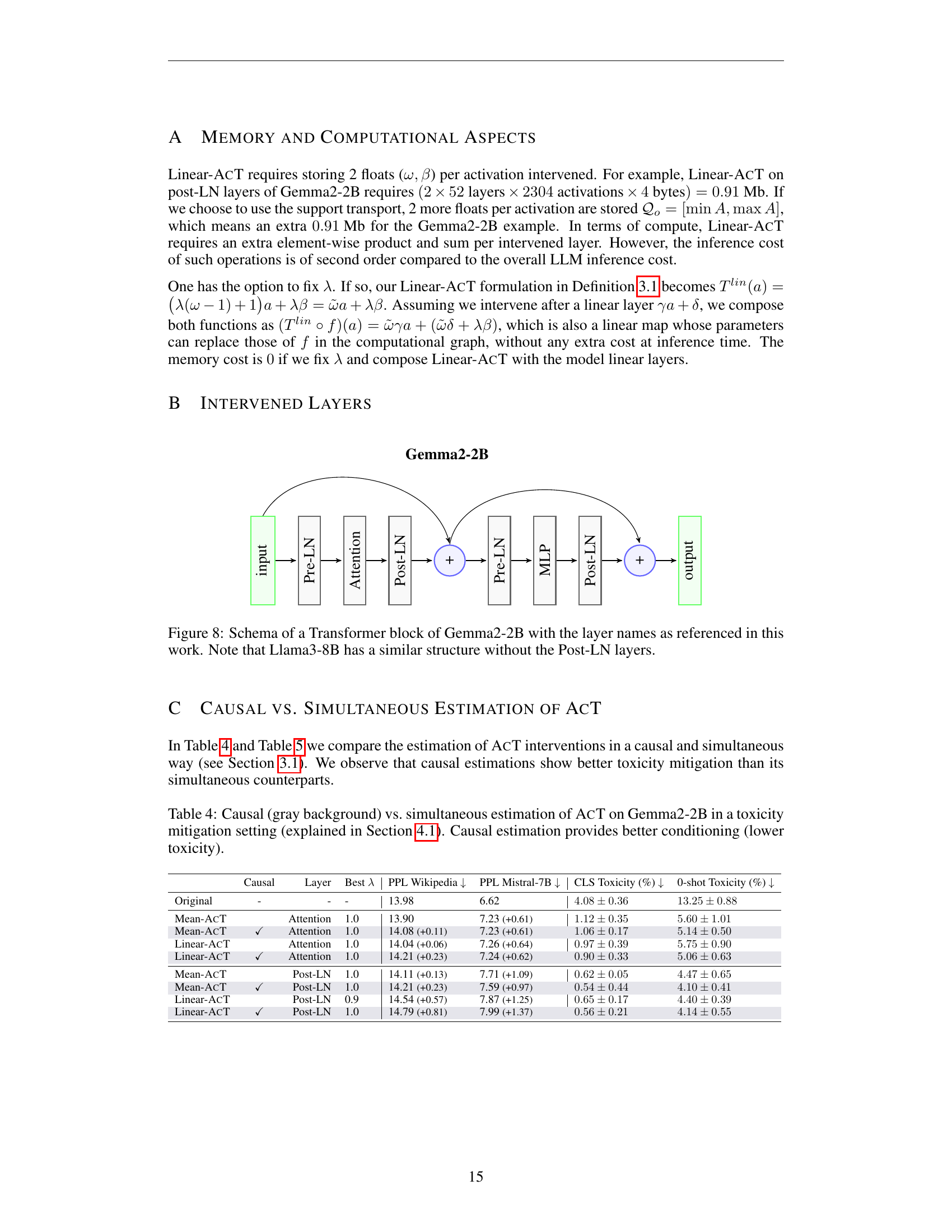

🔼 This figure shows how different choices of support for optimal transport affect the performance of Linear-ACT and Mean-ACT in mitigating toxicity in the Gemma2-2B language model. The x-axis shows the level of toxicity (CLS toxicity) and the y-axis represents the perplexity (PPL) of the model. Each line corresponds to a different choice of support for the optimal transport. The support ranges from a narrow interval [qt40, qt60] to the full range [min A, max A], which includes all samples, and finally to the entire real number line (-∞, ∞). The results show that using the support [qt0, qt100], which spans the entire range of observed activation values, provides the best balance between toxicity reduction and minimal increase in PPL, which is a measure of the language model’s performance. Using an excessively large or small support results in less effective toxicity mitigation or a significant performance penalty, respectively.

read the caption

Figure 9: We measure toxicity mitigation on Gemma2-2B by increasingly expanding the transport support from [qt40,qt60]subscriptqt40subscriptqt60[\text{qt}_{40},\text{qt}_{60}][ qt start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 40 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , qt start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 60 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ] on the farther right of the plots to [qt0,qt100]=[minA,maxA]subscriptqt0subscriptqt100𝐴𝐴[\text{qt}_{0},\text{qt}_{100}]=[\min A,\max A][ qt start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 0 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , qt start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 100 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ] = [ roman_min italic_A , roman_max italic_A ], which means the support spanned by all the samples in A𝐴Aitalic_A. For completeness, we add the full real support (−∞,∞)({-\infty},{\infty})( - ∞ , ∞ ). For Linear-AcT, using [qt0,qt100]subscriptqt0subscriptqt100[\text{qt}_{0},\text{qt}_{100}][ qt start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 0 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , qt start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 100 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ] achieve the best toxicity mitigation by incurring less than +11+1+ 1 increase in PPL. Note that (−∞,∞)({-\infty},{\infty})( - ∞ , ∞ ) results in higher PPL.

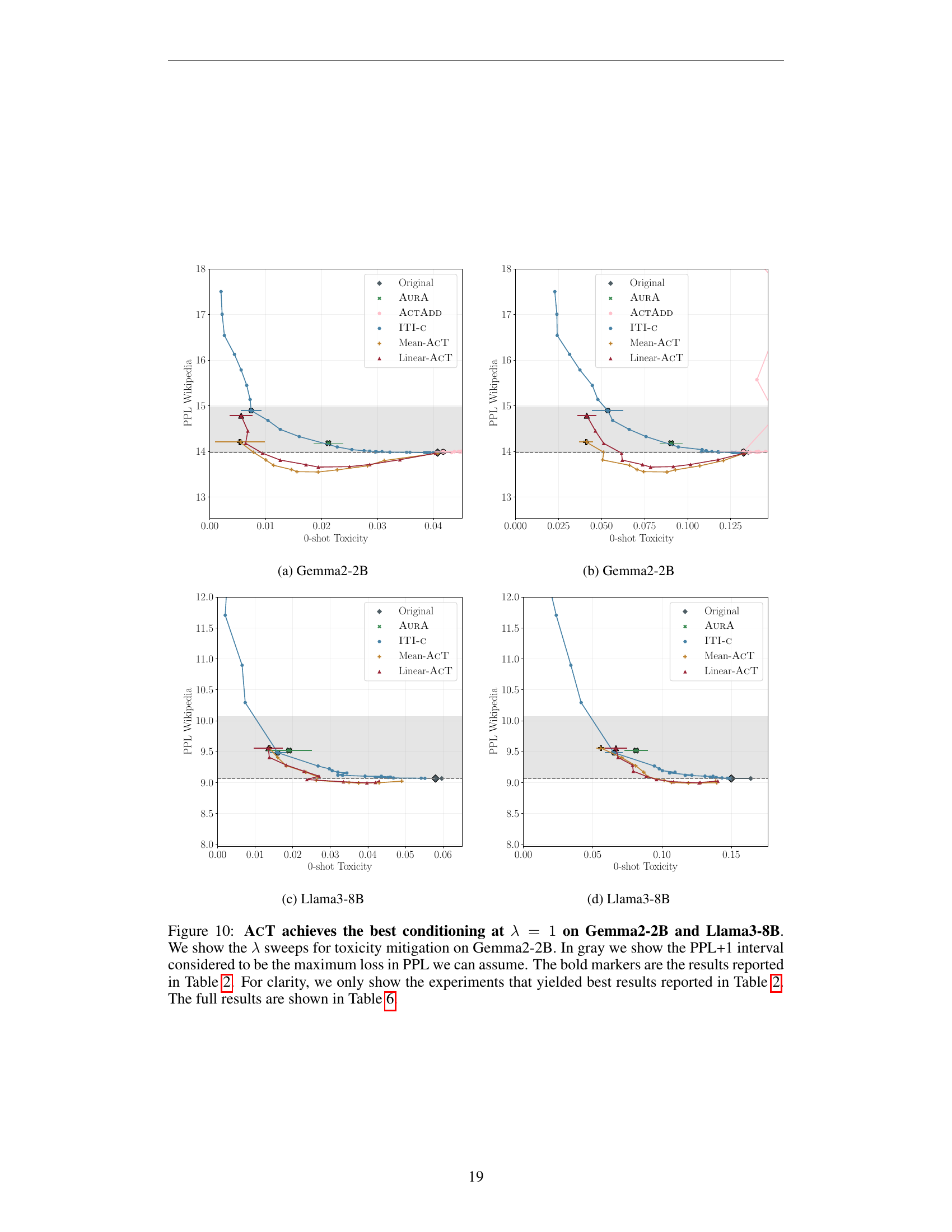

🔼 The figure shows the results of different methods for toxicity mitigation on the Gemma2-2B language model. It compares Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ACTADD, ITI-C, and AURA. The x-axis represents the 0-shot toxicity score, and the y-axis represents the PPL (perplexity). The plot demonstrates the effectiveness of Linear-ACT in reducing toxicity while maintaining acceptable perplexity levels. The colored regions highlight the trade-off between toxicity reduction and perplexity.

read the caption

(a) Gemma2-2B

🔼 Figure 10(b) presents the results of toxicity mitigation experiments on the Gemma2-2B language model. The x-axis represents the 0-shot toxicity rate, and the y-axis shows the perplexity score. Each line corresponds to a different method for mitigating toxicity, including the baseline (original model), AURA, ACTADD, ITI-C, Mean-ACT, and Linear-ACT. The shaded area indicates the acceptable increase in perplexity (+1 point) compared to the original model. The figure illustrates the performance of each method across different levels of 0-shot toxicity, demonstrating the effectiveness of Linear-ACT in reducing toxicity while maintaining low perplexity.

read the caption

(b) Gemma2-2B

🔼 Figure 10(c) presents the results for Llama 3B model, showing the effectiveness of ACT methods in reducing toxicity. The x-axis represents the 0-shot toxicity, while the y-axis shows the perplexity scores obtained for Wikipedia sentences. The different colored lines represent the various methods: original model, AURA, ACTADD, ITI-C, Mean-ACT, and Linear-ACT. The graph illustrates how each method affects both toxicity and perplexity; Linear-ACT shows the best trade-off between toxicity reduction and maintaining low perplexity.

read the caption

(c) Llama3-8B

🔼 The figure shows the results of a sweep of the parameter λ for inducing truthfulness with Linear-ACT on Llama3-8B. The x-axis represents the value of λ, while the y-axis shows both the MC1 accuracy and the MMLU accuracy. The plot visualizes the trade-off between improving the model’s accuracy on the TruthfulQA benchmark (MC1) and maintaining its performance on the Massive Multitask Language Understanding benchmark (MMLU). The shaded area highlights the acceptable range of PPL (perplexity) increase, which is set to +1 from the original model’s perplexity.

read the caption

(d) Llama3-8B

🔼 Figure 10 presents a detailed analysis of the impact of different transport strengths (λ) on the effectiveness of the Activation Transport (ACT) method for toxicity mitigation in LLMs. Specifically, it examines the effects of varying λ on Gemma2-2B and Llama3-8B models. The graph displays two key metrics: the perplexity (PPL) and the classification score for toxicity. The shaded region indicates the acceptable range of perplexity increase (PPL+1) from the original model. The selected data points highlight the best results obtained in Section 4.1, with a more comprehensive analysis available in Table 6.

read the caption

Figure 10: AcT achieves the best conditioning at λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1 on Gemma2-2B and Llama3-8B. We show the λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ sweeps for toxicity mitigation on Gemma2-2B. In gray we show the PPL+1 interval considered to be the maximum loss in PPL we can assume. The bold markers are the results reported in Section 4.1. For clarity, we only show the experiments that yielded best results reported in Section 4.1. The full results are shown in Table 6.

🔼 This figure shows the default pre-prompt used in the TruthfulQA multiple-choice section of the paper by Lin et al. (2021). The pre-prompt is a set of question-answer pairs designed to establish a context for evaluating the model’s ability to generate truthful responses. By using this consistent pre-prompt before each question in the TruthfulQA dataset, the researchers ensure a fair and controlled evaluation of the model’s performance on the task of truthfulness.

read the caption

Figure 11: Figure 21 from Lin et al. (2021) showing the default preprompt used for the TruthfulQA multiple choice part.

🔼 This figure visualizes the impact of varying the hyperparameter λ (lambda) on the performance of ITI-c method for inducing truthfulness in the Gemma2-2B language model. The x-axis represents the values of λ, ranging from 1.0 to 15.0 with increments of 1.0. The y-axis shows two key metrics: MC1 Accuracy (reflecting the model’s ability to answer truthfully) and MMLU Accuracy (measuring overall model performance). The plot helps determine the optimal λ value that maximizes truthfulness while maintaining a satisfactory level of overall model performance. The results are based on a single seed (random initialization of the model), suggesting the need for more extensive experiments to confirm the findings.

read the caption

Figure 12: Sweeping λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ for inducing truthfulness with ITI-c on Gemma2-2B. Left endpoint of line is λ=1.0𝜆1.0\lambda=1.0italic_λ = 1.0, right endpoint of line is λ=15.0𝜆15.0\lambda=15.0italic_λ = 15.0 (each point increasing λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ by 1.01.01.01.0). Note this is for 1111 seed only.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of varying the strength parameter λ (lambda) on the performance of ACTADD (an activation-based method for controlling LLMs) in enhancing truthfulness on the Gemma2-2B LLM. Four different layer types within the model (Attention, MLP, Post-Layernorm, Layernorm) are evaluated. The x-axis represents the lambda values tested: 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0. The y-axis shows the resulting MC1 accuracy and MMLU accuracy. The plot reveals the relationship between lambda, MC1 Accuracy, and MMLU accuracy for each layer type. Note that only results for a single seed are shown in this graph.

read the caption

Figure 13: Sweeping λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ for inducing truthfulness with ActAdd on Gemma2-2B. Left endpoint of line is λ=0.1𝜆0.1\lambda=0.1italic_λ = 0.1, right endpoint of line is λ=5.0𝜆5.0\lambda=5.0italic_λ = 5.0 (λ∈[0.1,0.2,0.3,0.4,0.5,0.6,0.7,0.8,0.9,1.0,2.0,3.0,4.0,5.0]𝜆0.10.20.30.40.50.60.70.80.91.02.03.04.05.0\lambda\in[0.1,0.2,0.3,0.4,0.5,0.6,0.7,0.8,0.9,1.0,2.0,3.0,4.0,5.0]italic_λ ∈ [ 0.1 , 0.2 , 0.3 , 0.4 , 0.5 , 0.6 , 0.7 , 0.8 , 0.9 , 1.0 , 2.0 , 3.0 , 4.0 , 5.0 ]). Note this is for 1111 seed only.

🔼 This figure visualizes the impact of varying the hyperparameter λ (lambda) on the performance of the ITI-c method for inducing truthfulness in the Llama3-8B language model. The x-axis represents the value of λ, ranging from 1.0 to 15.0 with increments of 1.0. The y-axis displays two key metrics: MC1 Accuracy and MMLU Accuracy, which measure the model’s performance on the TruthfulQA and MMLU benchmarks, respectively. The plot shows how changes in λ affect both metrics, allowing for an assessment of the optimal λ value for achieving a balance between increased truthfulness and maintained overall model performance. The results are presented for a single seed, meaning that the experiment was not repeated multiple times for averaging. Different layers in the model may have different results.

read the caption

Figure 14: Sweeping λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ for inducing truthfulness with ITI-c on Llama3-8B. Left endpoint of line is λ=1.0𝜆1.0\lambda=1.0italic_λ = 1.0, right endpoint of line is λ=15.0𝜆15.0\lambda=15.0italic_λ = 15.0 (each point increasing λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ by 1.01.01.01.0). Note this is for 1111 seed only.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of varying the strength parameter λ (lambda) on the performance of ACTADD (an activation-steering method) in improving the truthfulness of the Llama3-8B language model. The x-axis represents the values of lambda tested (from 0.1 to 5.0). The y-axis shows two metrics: the MC1 accuracy (a measure of the model’s accuracy on the TruthfulQA dataset) and the MMLU accuracy (a measure of the model’s general-purpose knowledge). The plot shows that there’s a relationship between lambda and model performance. However, the relationship isn’t always consistent, demonstrating sensitivity to the choice of lambda and the model’s behavior. Note that this data is from a single experimental run (one seed).

read the caption

Figure 15: Sweeping λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ for inducing truthfulness with ActAdd on Llama3-8B. Left endpoint of line is λ=0.1𝜆0.1\lambda=0.1italic_λ = 0.1, right endpoint of line is λ=5.0𝜆5.0\lambda=5.0italic_λ = 5.0 (λ∈[0.1,0.2,0.3,0.4,0.5,0.6,0.7,0.8,0.9,1.0,2.0,3.0,4.0,5.0]𝜆0.10.20.30.40.50.60.70.80.91.02.03.04.05.0\lambda\in[0.1,0.2,0.3,0.4,0.5,0.6,0.7,0.8,0.9,1.0,2.0,3.0,4.0,5.0]italic_λ ∈ [ 0.1 , 0.2 , 0.3 , 0.4 , 0.5 , 0.6 , 0.7 , 0.8 , 0.9 , 1.0 , 2.0 , 3.0 , 4.0 , 5.0 ]). Note this is for 1111 seed only.

🔼 This figure shows six images generated by Stable Diffusion XL (SDXL). Each image depicts a scene described by a prompt with art nouveau style tags added. The guidance strength, a parameter controlling the influence of the style tags on image generation, linearly increases from 1 to 6 across the six images. The leftmost image, with the lowest guidance strength, demonstrates a significant loss of semantic content from the original prompt; the scene described is barely recognizable. As the guidance strength increases, the image progressively incorporates more art nouveau style elements while retaining more of the original scene’s meaning.

read the caption

Figure 16: SDXL with art nouveau tags appended to the prompt as described in Section J.3 and guidance strength linearly increasing from 1 to 6. Note how for low guidance (left most images) the semantic content is almost completely lost.

🔼 The figure shows the failure of Stable Diffusion XL (SDXL) at concept negation when using negative prompts. Despite explicitly instructing the model not to generate a pink elephant, gorilla, or white bear, the model still includes these elements in the generated images. This highlights a limitation of relying solely on negative prompting to control the generated content within diffusion models. The image shows several generated images under each of three animals, revealing that the model frequently fails to respect the negation instruction.

read the caption

Figure 17: SDXL with Negative Prompt. Prompt: “There is a banana and two pieces of cheese on a plate. A {pink elephant, gorilla, white bear} cannot be seen anywhere.”. Negative prompt: “A {pink elephant, gorilla, white bear}”.

🔼 The figure shows the results of Stable Diffusion 3 when generating an image with negative prompting. The prompt instructs the model to create a two-tiered cake with multicolored stars, but explicitly excludes a pink elephant, a gorilla, and a white bear. Despite the negative prompt, the generated images still often include these undesired elements, highlighting the limitations of negative prompting in controlling image generation.

read the caption

Figure 18: Stable Diffusion 3 with Negative Prompt. Prompt: “2 tier cake with multicolored stars attached to it. A {pink elephant, gorilla, white bear} cannot be seen anywhere.” Negative prompt: “A {pink elephant, gorilla, white bear}.”.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods with varying intervention strength (λ) on the SDXL model for generating images with an ‘anime’ style. The leftmost column depicts the base image generated without any style intervention (λ = 0). Subsequent columns illustrate how the generated images change as the intervention strength increases, demonstrating the effect of each method on achieving the desired ‘anime’ style. The rightmost column represents the best intervention strength for each method, as determined by the highest 0-shot CLIP score.

read the caption

(a) Anime

🔼 The image showcases the results of applying the Linear-ACT method to a text-to-image diffusion model, specifically targeting the ‘Art Nouveau’ style. The figure shows a series of images generated with varying levels of conditioning strength (lambda), demonstrating a gradient from no style influence (lambda = 0) to a strong Art Nouveau influence (lambda = 1). This visual progression highlights the method’s ability to finely control the stylistic elements of the generated image.

read the caption

(b) Art Nouveau

🔼 This image shows the results of applying Linear-ACT to a text-to-image diffusion model for generating images with a cyberpunk style. The images demonstrate the model’s ability to control the level of cyberpunk style in the generated images, ranging from minimal to maximal cyberpunk influence. This control is achieved by varying a parameter (lambda) that governs the strength of the activation transport. The figure likely shows a series of images generated with different values of lambda, showcasing a progression of cyberpunk styling.

read the caption

(c) Cyberpunk

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C) to control the style of images generated by a text-to-image diffusion model. The prompt was the same for all methods, but the methods were used to steer the image generation towards an Impressionistic style. The rows represent different strengths of conditioning (λ parameter), ranging from no conditioning (λ=0) to full conditioning (λ=1). The rightmost column shows the image generated with the method’s optimal conditioning strength (λ), as determined by the highest CLIP score (similarity between generated and original prompt). This visually demonstrates the varying degrees of control achievable with each method and highlights the balance Linear-ACT achieves between stylistic control and semantic preservation.

read the caption

(d) Impressionism

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to generate images with a ‘sketch’ style. The leftmost column uses a strength parameter (λ) of 0, representing no style intervention. The parameter linearly increases across the columns, showing how the methods progressively induce sketch style while maintaining image coherence. This experiment evaluates the interpretability and effectiveness of different approaches to style control in image diffusion models. The results highlight the tradeoffs between style fidelity and maintaining original content.

read the caption

(e) Sketch.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods with varying intervention strength (lambda) to generate images of a scene with the style of watercolor. The rightmost column represents the best intervention strength for each method (lambda = 1 for Linear-ACT and lambda = 2 for ITI-C), chosen based on the highest 0-shot score. The figure demonstrates that Linear-ACT consistently produces high-quality watercolor-style images across different intervention strengths and maintains a good balance between style and content preservation.

read the caption

(f) Watercolor

🔼 Figure 19 displays the results of a style transfer experiment using three different methods: Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C. The experiment uses Stable Diffusion XL (SDXL) to generate images of a plane floating on a lake, with different styles applied. The leftmost column shows the original image without any style applied, while the following columns show the results with increasing style strength (lambda), ranging from 0 to 1. The rightmost column represents the best style transfer result achieved with each method, based on the results in Figure 6. The figure demonstrates the effectiveness of Linear-ACT in generating images with various styles while maintaining image quality. In contrast, Mean-ACT fails to generate art nouveau style, while ITI-C introduces noise in art nouveau and cyberpunk styles.

read the caption

Figure 19: SDXL - A plane floating on top of a lake surrounded by mountains. From left to right conditioning strength λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ increases from 0 to 1. Rightmost column corresponds to the best strength found in Figure 6 (λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1 for AcT and λ=2𝜆2\lambda=2italic_λ = 2 for ITI-c). Linear-AcT succeeds at inducing different styles. Mean-AcT fails at inducing art nouveau. ITI-c introduces noise for art nouveau and cyberpunk.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ITI-C) for style control in the SDXL model on the image generation task. Each row represents a different method, and the columns show the generated images with different intervention strengths (λ). The leftmost column shows the images generated without any intervention (λ=0), while the rightmost column shows the result of applying the method with full strength (λ=1). The results demonstrate the effectiveness and variability of the methods in controlling style, with Linear-ACT showing the best results in terms of both style consistency and image quality.

read the caption

(a) Anime

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the Linear-ACT method to control the style of images generated by the SDXL model. The prompt used was ‘A firetruck with lights on is on a city street.’ The images are generated at different values of λ, a parameter controlling the strength of conditioning, ranging from 0 to 1. Each column represents a specific style applied using the method. The progression of styles demonstrates the ability of Linear-ACT to achieve fine-grained style control. The rightmost column shows the best result (λ=1) for this style.

read the caption

(b) Art Nouveau

🔼 This image shows the results of applying the Linear-ACT method to generate images with a cyberpunk style. The figure shows a series of images generated with increasing values of the conditioning parameter λ (lambda). As λ increases from 0 to 1, the cyberpunk style becomes more pronounced in the generated images. The figure allows a visual comparison of the effects of the Linear-ACT method on style control in image generation.

read the caption

(c) Cyberpunk

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to generate images with an Impressionism style. The leftmost column represents the original image generated without any style intervention. Subsequent columns show the results of applying the methods with increasing intervention strength (lambda), progressing from no transport (lambda=0) to full transport (lambda=1). The rightmost column represents the image generated at the best performing lambda value for each method, according to qualitative assessment.

read the caption

(d) Impressionism

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods on the SDXL model for generating images with a ‘sketch’ style. Images generated with different intervention strengths (lambda values from 0 to 1) are displayed. It helps to visualize how each method affects the style of the generated image and its adherence to the original prompt, showing the trade-off between achieving the desired style and preserving the original image’s semantic content.

read the caption

(e) Sketch.

🔼 The figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to control the style of images generated by Stable Diffusion XL (SDXL) and FLUX models. The prompt is ‘A sandwich is placed next to some vegetables.’ Each row represents a different intervention strength (lambda), ranging from 0 to 1, showing a progression of the image generated toward the ‘Watercolor’ style. The rightmost column shows the result at the intervention strength that yielded the highest 0-shot classification score for the style using a CLIP classifier.

read the caption

(f) Watercolor

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Activation Transport (ACT) and other methods to control the style of images generated by a text-to-image diffusion model (SDXL). The prompt is a description of a firetruck with lights on a city street. Different styles (anime, art nouveau, cyberpunk, impressionism, sketch, watercolor) are induced. The leftmost columns in each row show the output of the model with no style control (λ=0), with style strength increasing as the column number increases, culminating in the best result according to Figure 6, where λ is a hyperparameter controlling the strength of style transfer, for each method (λ=1 for ACT, λ=2 for ITI-C). The figure demonstrates ACT’s effectiveness at inducing a range of styles while maintaining image quality, in contrast with some other methods which can cause noise or fail to generate specific styles.

read the caption

Figure 20: SDXL - A firetruck with lights on is on a city street. Rightmost column corresponds to the best strength found in Figure 6 (λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1 for AcT and λ=2𝜆2\lambda=2italic_λ = 2 for ITI-c). Mean-AcT fails at inducing impressionism and art nouveau. ITI-c achieves the strongest conditioning and generates a noisy image for art nouveau.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ITI-C) for style control in image generation on the SDXL model. Each row represents one of the three methods, and each column represents the result of applying the method with varying strength (lambda) to the input prompt ‘a plane floating on top of a lake surrounded by mountains’. The goal is to generate images with an ‘anime’ style. The rightmost column shows the best result achieved by each method, while the columns to the left show the image generated as lambda increases. The figure aims to demonstrate the effectiveness and differences in style control capability between the various methods.

read the caption

(a) Anime

🔼 This figure shows a series of images generated by a text-to-image diffusion model, where the style of the generated images is controlled by adjusting the strength of the conditioning. The images depict a firetruck with its lights on driving down a city street. In each row, the style evolves from the original prompt’s style (no extra style conditioning) to a more pronounced Art Nouveau style as the transport strength increases from 0 to 1. The progression shows how the initial prompt’s features gradually transform into Art Nouveau features, enabling fine-grained control over the visual style. The rightmost column displays the image generated with the transport strength parameter set to the optimal value (λ=1 for Linear-ACT, and λ=2 for ITI-C and Mean-ACT), which achieves the best trade-off between maintaining the original image content and integrating Art Nouveau elements.

read the caption

(b) Art Nouveau

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT to control the style of images generated by a text-to-image diffusion model. Specifically, it demonstrates the effect of varying the strength parameter (λ) on the generation of images with a cyberpunk style. It visually compares the results of Linear-ACT to those of Mean-ACT and ITI-C across various values of λ, illustrating Linear-ACT’s ability to effectively control the cyberpunk style while maintaining semantic coherence.

read the caption

(c) Cyberpunk

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ITI-C) for style control in image generation using the Impressionism style. The leftmost column shows the base image generated from the unconditional prompt without any style manipulation. Subsequent columns show images generated with increasing strength (lambda) of style intervention. Each method’s impact on the generated image is evaluated in terms of the balance between incorporating the desired Impressionism style elements and preserving the semantic content of the original scene depicted in the unconditional image. The approach allows for a fine-grained control over style transfer, allowing the user to specify the exact degree of style influence desired.

read the caption

(d) Impressionism

🔼 The image shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to generate images with a ‘sketch’ style. The leftmost column represents no style intervention (λ = 0), while the columns progress to the right with increasing style conditioning strength (λ). The rightmost column shows the result at the optimal λ value for each method, as determined by the highest 0-shot classification score using CLIP.

read the caption

(e) Sketch.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to generate images with a watercolor style. The input prompt is: ‘A sandwich is placed next to some vegetables’. The leftmost column shows the original image generated without any style control. The subsequent columns illustrate the effect of increasing the conditioning strength (λ) from 0 to 1 for each method, demonstrating the gradual transition from the original style to the target watercolor style. The final column (λ=1 for Linear-ACT and λ=2 for ITI-C) presents the images with the highest 0-shot score based on the CLIP embeddings. The results reveal that Linear-ACT produces the best trade-off between style control and preservation of the original semantic content, whereas ITI-C sometimes introduces noise and distorts semantics.

read the caption

(f) Watercolor

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Activation Transport (ACT) and Inference-Time Intervention (ITI-C) methods to control the style of images generated by Stable Diffusion XL (SDXL). The figure presents a series of images generated using different intervention strengths (lambda). Each row represents a different style (anime, art nouveau, cyberpunk, impressionism, sketch, watercolor), while the columns show the progression from no style intervention (lambda=0) to the strongest intervention. The rightmost column illustrates the results using the optimal intervention strength (lambda=1 for ACT, lambda=2 for ITI-C). The image clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of ACT in inducing a desired style consistently and smoothly, unlike ITI-C, which shows inconsistent and sometimes disruptive results, especially for the cyberpunk style. The figure provides a visual comparison of how different methods achieve style control in a diffusion model. The original prompt was ‘A sandwich is placed next to some vegetables’.

read the caption

Figure 21: SDXL - A sandwich is placed next to some vegetables. Rightmost column corresponds to the best strength found in Figure 6 (λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1 for AcT and λ=2𝜆2\lambda=2italic_λ = 2 for ITI-c). ITI-c fails at inducing style progressively (e.g. (c) cyberpunk).

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different methods for controlling the style of images generated by diffusion models. Specifically, it visualizes the effects of Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods on generating images in the ‘anime’ style. The figure presents a series of images generated using different intervention strengths (lambda values) for each method, allowing for a visual comparison of the results. The rightmost column in each set shows the image generated at the optimal lambda value, according to evaluation metrics used in the paper. It demonstrates the degree of control each method offers in achieving a specific style and how well they preserve semantic content of the original image prompt.

read the caption

(a) Anime

🔼 The figure displays several images generated by a text-to-image diffusion model using different style control methods. The images are of a firetruck on a city street, and each row represents a different style control method (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ITI-C) with different intervention strengths. The rightmost column shows the best results for each method.

read the caption

(b) Art Nouveau

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT to generate images with a cyberpunk style. The images demonstrate the effect of increasing the transport strength parameter (λ) from 0 to 1, showing a progression from the original image (no cyberpunk style) to a fully realized cyberpunk image. Three different methods are used for comparison: Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C, and their results are presented for comparison.

read the caption

(c) Cyberpunk

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the Linear-ACT method to generate images with an Impressionism style. The leftmost column displays images generated without any style conditioning, while subsequent columns show images generated with increasing strength of Impressionism style conditioning, using Linear-ACT. The rightmost column represents the result at the highest 0-shot score obtained in Figure 6.

read the caption

(d) Impressionism

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to generate images with a ‘sketch’ style. The images display a gradient of style intensity, controlled by a parameter λ ranging from 0 (no transport, original image) to 1 (full transport, maximum styling). The figure showcases the effectiveness of each method in achieving a sketch-like style while preserving the original image’s content, highlighting differences in the balance between style control and semantic preservation across the three methods.

read the caption

(e) Sketch.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods on the SDXL and FLUX models to induce a watercolor style in image generation. The prompt is a simple sentence describing a scene. The parameter λ controls the strength of conditioning. For Linear-ACT, the best result is achieved at λ = 1, exhibiting a balance between style preservation and adherence to the original prompt. For other methods, the best results are achieved at different λ values, leading to either excessive style emphasis or semantic distortion.

read the caption

(f) Watercolor

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of Linear-ACT and ITI-c methods on controlling style transfer in image generation using the FLUX model. The prompt used is ‘A group of zebra standing next to each other on a dirt field’. The figure shows a series of images generated by the FLUX model with different style conditioning strengths, applied using each method. The leftmost images in each row represent no style transfer (λ=0), and the strength increases towards the right, culminating in the rightmost column which displays the best results obtained by each method (λ=1). The images show how each method affects the style of the zebra and the background, highlighting Linear-ACT’s success in accurately achieving diverse styles and ITI-c’s difficulties in applying certain styles such as cyberpunk and anime.

read the caption

Figure 22: FLUX - A group of zebra standing next to each other on a dirt field. Rightmost column corresponds to the best strength found in Figure 6 (λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1 for all methods). Linear-AcT is successful at inducing all styles. ITI-c fails at inducing cyberpunk and anime.

🔼 This figure displays the results of applying different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ITI-C) for style control on the SDXL model. The image depicts a plane floating atop a lake surrounded by mountains. Each row shows how the image changes as the strength of conditioning increases (lambda values increase from 0 to 1). The rightmost column represents the result with the highest CLIP score (indicating the best trade-off between achieving the desired style and preserving the original prompt semantics).

read the caption

(a) Anime

🔼 The figure showcases the results of applying the Linear-ACT method on SDXL and FLUX models for inducing the Art Nouveau style in image generation. It presents a series of images generated with increasing intervention strength (λ) ranging from 0 to 1. The images visually demonstrate the transition from the original prompt’s image to an Art Nouveau style image. The results highlight Linear-ACT’s capacity for interpretable and fine-grained style control in image generation.

read the caption

(b) Art Nouveau

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT to a text-to-image diffusion model for style control. Specifically, it demonstrates the generation of images with a ‘cyberpunk’ style. The images in the row progress from left to right, showing how the strength of the style increases as the parameter lambda increases from 0 to 1, controlled by Linear-ACT. The rightmost image represents the result at lambda = 1, indicating full transport and the most prominent cyberpunk style.

read the caption

(c) Cyberpunk

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C to generate images in the Impressionism style. For each method, there are images generated with increasing intervention strength (λ), ranging from 0 (no intervention) to 1 (full intervention). The images illustrate the effectiveness of each method at achieving the Impressionism style while maintaining semantic coherence. Visually comparing the images across methods allows for evaluation of the ability of each method to control style while preserving image content.

read the caption

(d) Impressionism

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to generate images of a plane on a lake. The leftmost column is the original image, and the subsequent columns show the progressive application of the methods for different strengths, with the rightmost column representing the best result for each method. The results demonstrate the level of control each method provides over the generated image’s style, highlighting Linear-ACT’s ability to achieve a balance between stylistic changes and maintaining the original image’s semantic content.

read the caption

(e) Sketch.

🔼 The image shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods to generate images with a watercolor style. Each method is applied with increasing strength (λ), ranging from 0 to 1. The rightmost column shows the result for the best-performing λ value, indicating the trade-off between achieving the desired style and maintaining the original image’s semantic content. The goal is to demonstrate the effectiveness of each method in controlling the style of image generation using different activation steering techniques.

read the caption

(f) Watercolor

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying three different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C) to control the style of images generated by the FLUX model. The prompt is a description of a black cat with green eyes sitting in a bathroom sink. Each row represents a different style (anime, art nouveau, cyberpunk, impressionism, sketch, watercolor). The leftmost column shows the original image generated without any style intervention. Subsequent columns show how the style changes with increasing strength of conditioning (λ) for each method. The rightmost column shows the image corresponding to the best result for each style and method, based on results shown in Figure 6. The results indicate Linear-ACT generally performs well across all styles, whereas Mean-ACT and ITI-C have more limited success. Specifically, ITI-C fails to effectively induce a cyberpunk style.

read the caption

Figure 23: FLUX - Black cat with green eyes sitting in a bathroom sink. Rightmost column corresponds to the best strength found in Figure 6 (λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1 for all methods). AcT’s conditioning is weak for sketch and watercolor. ITI-c fails at inducing cyberpunk.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods for style transfer on the SDXL model with the prompt ‘A plane floating on top of a lake surrounded by mountains.’ Each row represents one of the three methods, and the columns show the results with the strength parameter lambda increasing from 0 to 1. The rightmost column shows the result with the best lambda value as determined by a 0-shot classification score, which balances the presence of the desired style with the preservation of the original prompt’s meaning. The images illustrate how each method affects the style of the generated image.

read the caption

(a) Anime

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the Linear-ACT method to generate images with an Art Nouveau style. Images are generated by a text-to-image diffusion model (specifically, either SDXL or FLUX) using different values of lambda (λ), which controls the strength of the Art Nouveau style intervention. The results illustrate the effect of varying the amount of style transfer, from no intervention (λ = 0) to full transport (λ = 1). The images demonstrate how Linear-ACT provides interpretable control over the style by smoothly transitioning between the original image and the fully stylized version.

read the caption

(b) Art Nouveau

🔼 The image showcases the results of applying Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, and ITI-C methods on a text-to-image diffusion model (SDXL or FLUX) with the prompt: “A firetruck with lights on is on a city street.” The image shows how each method, with increasing intervention strength (lambda), affects the style of the generated image. Linear-ACT aims for a gradual style shift, while ITI-C and Mean-ACT might not achieve smooth transitions or might introduce noise.

read the caption

(c) Cyberpunk

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ITI-C) to generate images with an Impressionism style. The leftmost column displays the original image generated without any style intervention, while subsequent columns show progressively stronger applications of the style intervention, controlled by parameter λ (lambda). The rightmost column presents the image generated at the optimal λ value, according to the highest 0-shot score. It visually demonstrates how each method affects the Impressionism style and the trade-off between achieving the style and maintaining the original image’s semantic content.

read the caption

(d) Impressionism

More on tables

| Causal | Layer | Best λ | PPL Wikipedia ↓ | PPL Mistral-7B ↓ | CLS Toxicity (%) ↓ | 0-shot Toxicity (%) ↓ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | - | - | - | 13.98 | 6.62 | 4.08 ± 0.36 | 13.25 ± 0.88 |

| Mean-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 13.90 | 7.23 (+0.61) | 1.12 ± 0.35 | 5.60 ± 1.01 | |

| Mean-AcT | ✓ | Attention | 1.0 | 14.08 (+0.11) | 7.23 (+0.61) | 1.06 ± 0.17 | 5.14 ± 0.50 |

| Linear-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 14.04 (+0.06) | 7.26 (+0.64) | 0.97 ± 0.39 | 5.75 ± 0.90 | |

| Linear-AcT | ✓ | Attention | 1.0 | 14.21 (+0.23) | 7.24 (+0.62) | 0.90 ± 0.33 | 5.06 ± 0.63 |

| Mean-AcT | Post-LN | 1.0 | 14.11 (+0.13) | 7.71 (+1.09) | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 4.47 ± 0.65 | |

| Mean-AcT | ✓ | Post-LN | 1.0 | 14.21 (+0.23) | 7.59 (+0.97) | 0.54 ± 0.44 | 4.10 ± 0.41 |

| Linear-AcT | Post-LN | 0.9 | 14.54 (+0.57) | 7.87 (+1.25) | 0.65 ± 0.17 | 4.40 ± 0.39 | |

| Linear-AcT | ✓ | Post-LN | 1.0 | 14.79 (+0.81) | 7.99 (+1.37) | 0.56 ± 0.21 | 4.14 ± 0.55 |

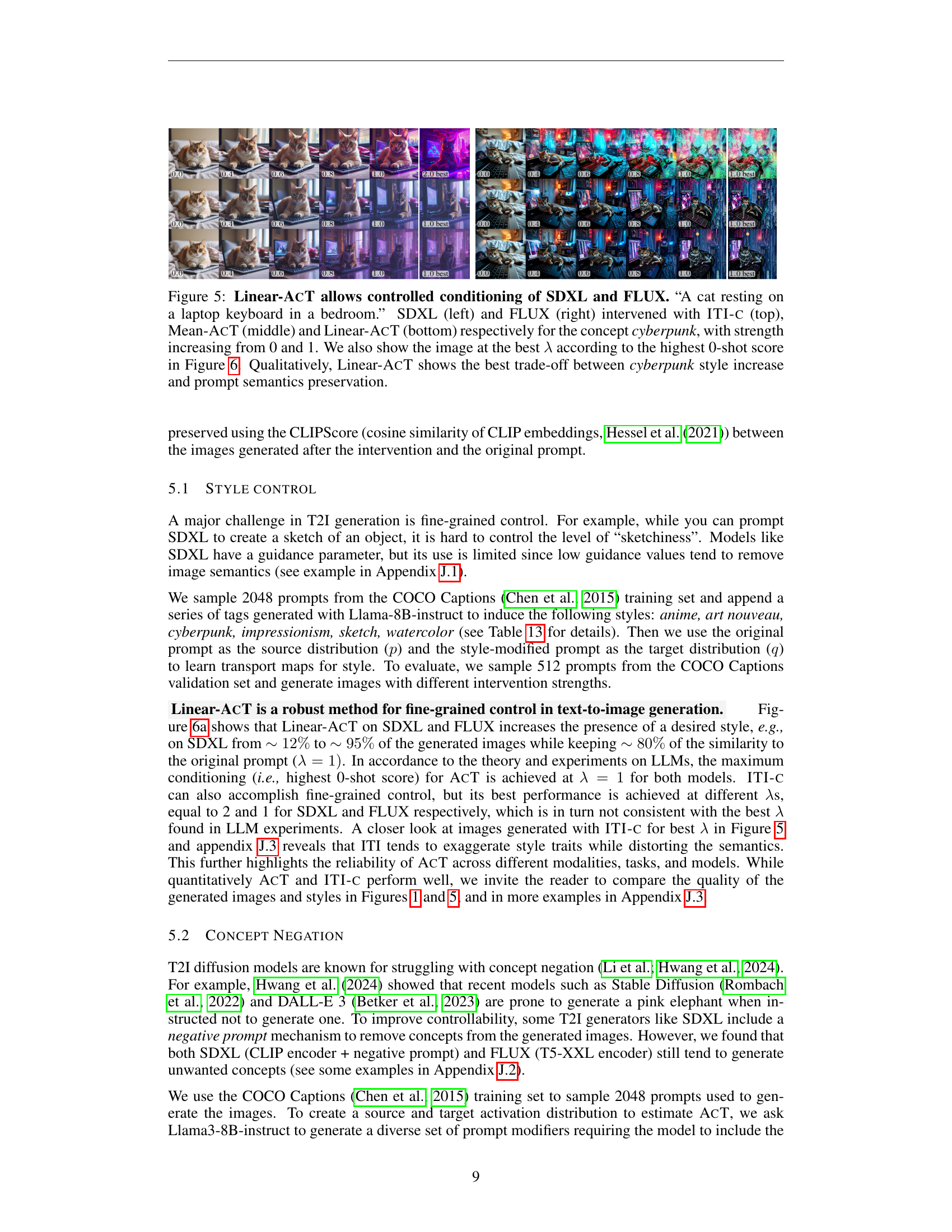

🔼 Table 2 presents the results of toxicity mitigation experiments conducted on two large language models, Gemma2-2B and Llama3-8B. The experiments involved applying several methods (ACT, ITI-C, AURA, ACTADD) to reduce toxicity in model outputs. For each model, different layers within the model’s architecture were targeted for intervention. A parameter λ (lambda) controls the strength of the intervention. The table shows the best results achieved for each method, focusing on the reduction in toxicity (measured by CLS toxicity) while ensuring that the increase in perplexity (PPL) on a Wikipedia text dataset remained below 1. The ACT methods consistently yielded the best results, significantly reducing toxicity with minimal impact on perplexity. In contrast, ITI-C’s performance was highly sensitive to the choice of lambda and layer, and AURA’s impact was less substantial.

read the caption

Table 2: Toxicity mitigation for Gemma2-2B and Llama3-8B, results over 5 runs. We intervene upon different layer types (layer column) and show the best layer per method. ITI-c, ActAdd and AcT have a strength parameter λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ which we sweep. For each method, we report results for the λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ that attained the best CLS toxicity that incurs less than +11+1+ 1 increase in PPL Wikipedia. AcT methods and provide best results for λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1, achieving up to 7.5×7.5\times7.5 × (Gemma2-2B) and 4.3×4.3\times4.3 × (Llama3-8B) CLS toxicity mitigation with Linear-AcT. ITI-c is very sensitive to λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ as well as layer choice (see full results in Appendix G), and AurA reaches up to 3.1×3.1\times3.1 × reduction.

| Causal | Layer | Best λ | PPL Wikipedia ↓ | PPL Mistral-7B ↓ | CLS Toxicity (%) ↓ | 0-shot Toxicity (%) ↓ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | - | - | - | 9.06 | 5.68 | 5.80 | 15.00 |

| Mean-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 9.35 (+0.28) | 6.33 (+0.65) | 1.40 ± 0.29 | 6.73 ± 1.13 | |

| Mean-AcT | ✓ | Attention | 1.0 | 9.56 (+0.49) | 6.36 (+0.68) | 1.38 ± 0.17 | 5.60 ± 0.34 |

| Linear-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 9.38 (+0.32) | 6.27 (+0.58) | 1.38 ± 0.24 | 6.55 ± 0.75 | |

| Linear-AcT | ✓ | Attention | 1.0 | 9.56 (+0.49) | 6.28 (+0.60) | 1.35 ± 0.39 | 6.68 ± 0.81 |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the performance of different methods on the TruthfulQA benchmark. The experiments involved modifying the activations of pre-trained large language models (LLMs) Gemma2-2B and Llama3-8B. Multiple methods were tested, including ACT, ITI-C, and ACTADD, each with a tunable parameter λ (lambda). The models’ performance was measured using three metrics: MC1 Accuracy, MC2 Accuracy, and MMLU Accuracy. The table shows the best performance obtained for each method by sweeping through different values of λ, while ensuring that the obtained MMLU accuracy for each method was comparable (±0.1) to the best MMLU accuracy achieved by the ACT methods. The best performing layer for each method is also identified.

read the caption

Table 3: TruthfulQA results for Gemma2-2B and Llama3-8B, results over 5 runs. We intervene upon different layers (layer column) and show the best per model. ITI-c, ActAdd and AcT have a strength parameter λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ which we sweep, reporting the best λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ result per model (MC1 Accuracy so that MMLU is within the best AcT MMLU ± 0.1plus-or-minus0.1\pm\;0.1± 0.1).

| Layer | Best λ | PPL Wikipedia ↓ | PPL Mistral-7B ↓ | MMLU ↑ | CLS Toxicity (%) ↓ | 0-shot Toxicity (%) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | - | - | 13.98 | 6.68 | 53.1 | 4.17 ± 0.32 |

| ActAdd | Atention | 0.5 | 13.99 (+0.02) | 6.58 | 53.2 (+0.2) | 4.17 ± 0.15 |

| ITI-c | Atention | 8.0 | 14.90 (+0.92) | 7.44 (+0.76) | 52.6 (-0.5) | 0.74 ± 0.18 |

| Mean-AcT | Atention | 1.0 | 14.08 (+0.11) | 7.23 (+0.55) | 52.5 (-0.6) | 1.06 ± 0.17 |

| Linear-AcT | Atention | 1.0 | 14.21 (+0.23) | 7.24 (+0.56) | 52.2 (-0.9) | 0.90 ± 0.33 |

| ActAdd | Post-LN | 0.1 | 14.04 (+0.06) | 6.61 | 53.2 (+0.2) | 4.08 ± 0.43 |

| ITI-c | Post-LN | 13.0 | 14.89 (+0.92) | 7.34 (+0.66) | 52.8 (-0.3) | 3.08 ± 0.61 |

| Mean-AcT | Post-LN | 1.0 | 14.21 (+0.23) | 7.59 (+0.90) | 51.6 (-1.5) | 0.54 ± 0.44 |

| Linear-AcT | Post-LN | 1.0 | 14.79 (+0.81) | 7.99 (+1.31) | 51.3 (-1.8) | 0.56 ± 0.21 |

| AurA | MLP | - | 14.18 (+0.21) | 7.04 (+0.36) | 53.0 (-0.1) | 2.12 ± 0.27 |

| ActAdd | MLP | 0.5 | 14.69 (+0.72) | 6.67 (+0.05) | 53.0 (-0.1) | 3.96 ± 0.24 |

| ITI-c | MLP | 1.0 | 13.99 (+0.01) | 6.77 (+0.08) | 52.8 (-0.3) | 4.50 ± 0.32 |

| Mean-AcT | MLP | 1.0 | 14.33 (+0.35) | 7.02 (+0.34) | 52.4 (-0.7) | 1.30 ± 0.37 |

| Linear-AcT | MLP | 1.0 | 14.89 (+0.92) | 7.53 (+0.85) | 51.9 (-1.2) | 1.30 ± 0.39 |

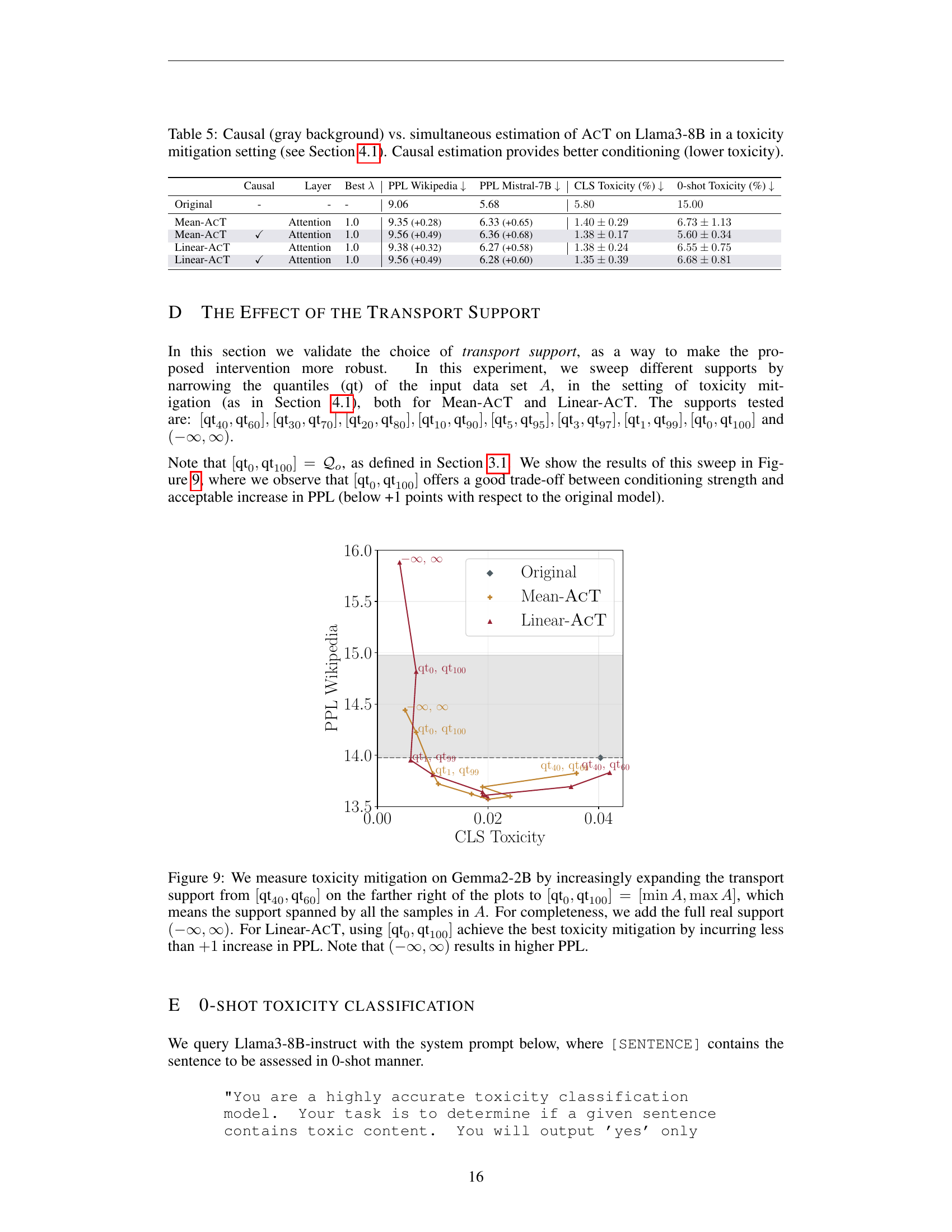

🔼 This table compares the performance of causal and simultaneous estimation methods of Activation Transport (ACT) on the Gemma2-2B language model for toxicity mitigation. Causal estimation involves sequentially applying transport maps layer by layer, respecting the causal flow of information within the model. Simultaneous estimation, on the other hand, applies transport maps to all layers at once. The table shows various metrics, including perplexity and toxicity scores, to evaluate the effectiveness of each method in reducing toxicity while maintaining the overall model’s usability. The results demonstrate that the causal estimation of ACT achieves better results in toxicity reduction compared to simultaneous estimation.

read the caption

Table 4: Causal (gray background) vs. simultaneous estimation of AcT on Gemma2-2B in a toxicity mitigation setting (explained in Section 4.1). Causal estimation provides better conditioning (lower toxicity).

| Layer | Best λ | PPL Wikipedia ↓ | PPL Mistral-7B ↓ | MMLU ↑ | CLS Toxicity (%) ↓ | 0-shot Toxicity (%) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | - | - | 9.06 | 5.68 | 65.3 | 5.80 |

| ActAdd | Atention | 0.3 | 9.71 (+0.65) | 5.85 (+0.16) | 65.5 (+0.2) | 5.57 ± 0.45 |

| ITI-c | Atention | 3.0 | 9.48 (+0.42) | 6.17 (+0.49) | 64.7 (-0.6) | 1.60 ± 0.22 |

| Mean-AcT | Atention | 1.0 | 9.56 (+0.49) | 6.36 (+0.68) | 64.7 (-0.7) | 1.38 ± 0.17 |

| Linear-AcT | Atention | 1.0 | 9.56 (+0.49) | 6.28 (+0.60) | 64.5 (-0.8) | 1.35 ± 0.39 |

| AurA | MLP | - | 9.52 (+0.45) | 6.05 (+0.37) | 65.5 (+0.2) | 1.90 ± 0.61 |

| ActAdd | MLP | - | - | - | - | - |

| ITI-c | MLP | 1.0 | 9.09 (+0.03) | 5.79 (+0.11) | 63.5 (-1.9) | 5.62 ± 0.96 |

| Mean-AcT | MLP | 0.9 | 9.90 (+0.84) | 6.24 (+0.55) | 60.7 (-4.6) | 2.10 ± 0.48 |

| Linear-AcT | MLP | 0.8 | 10.06 (+0.99) | 5.98 (+0.29) | 61.9 (-3.4) | 2.23 ± 0.53 |

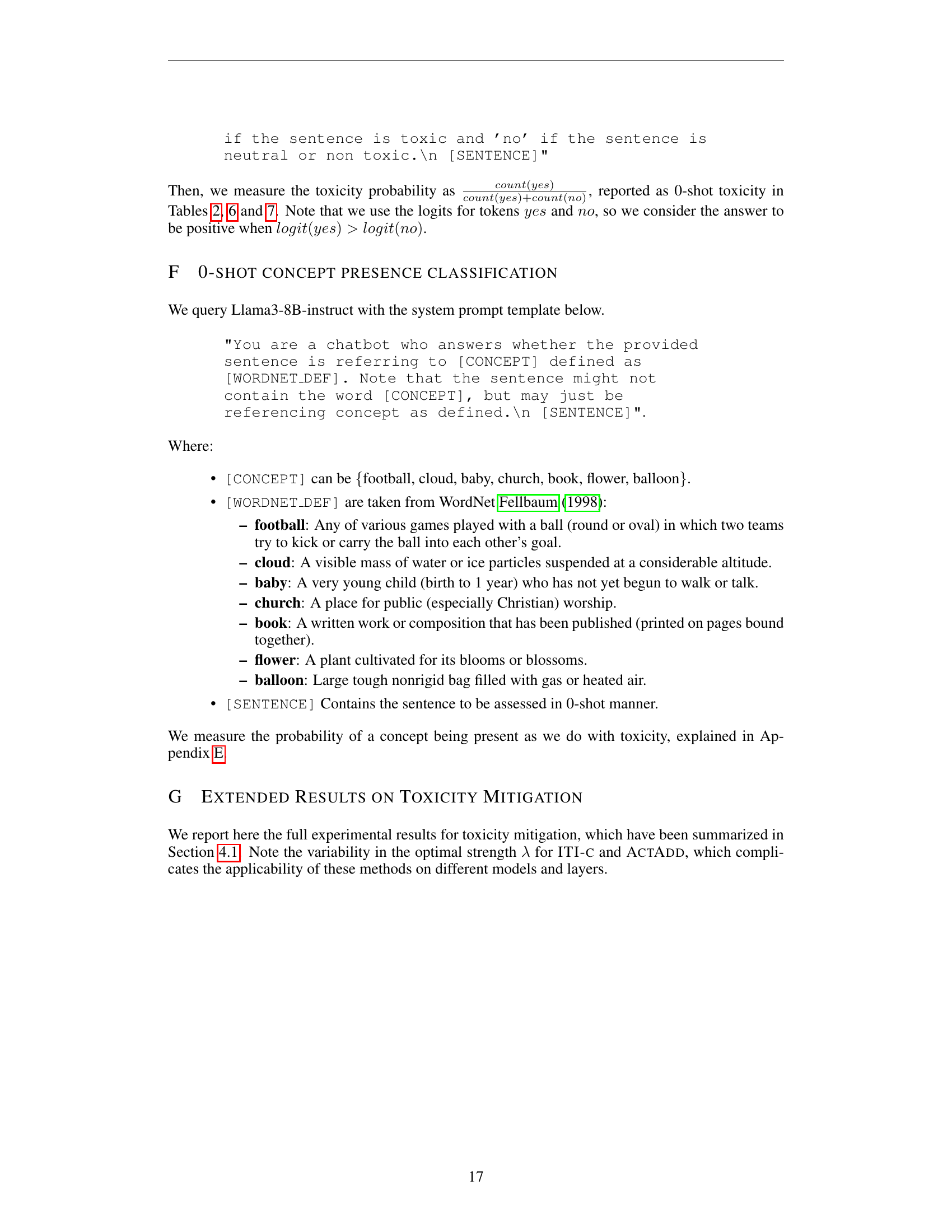

🔼 This table compares the results of causal and simultaneous estimation methods for the Activation Transport (ACT) model on the Llama3-8B large language model. The goal is toxicity mitigation, as described in section 4.1. The table shows the performance metrics for both estimation methods across different layers in the model, illustrating that the causal approach leads to better control over toxicity (lower toxicity scores) while maintaining reasonable performance on other metrics. The gray background highlights the causal estimation results.

read the caption

Table 5: Causal (gray background) vs. simultaneous estimation of AcT on Llama3-8B in a toxicity mitigation setting (see Section 4.1). Causal estimation provides better conditioning (lower toxicity).

| Layer | Best λ | MC1 Accuracy (%) ↑ | MC2 Accuracy (%) ↑ | MMLU Accuracy (%) ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | - | - | 21.05 | 32.80 |

| AurA | MLP | - | 21.20 ± 0.10 | 32.88 ± 0.22 |

| ActAdd | Attention | 3.0 | 22.64 ± 0.00 | 34.64 ± 0.00 |

| ITI-c | Attention | 5.0 | 23.18 ± 0.28 | 36.16 ± 0.34 |

| Mean-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 21.62 ± 0.07 | 34.08 ± 0.19 |

| Linear-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 21.71 ± 0.14 | 34.47 ± 0.22 |

| ActAdd | All-LN | 1.0 | 21.42 ± 0.00 | 32.93 ± 0.00 |

| ITI-c | All-LN | 4.0 | 23.94 ± 0.96 | 36.62 ± 0.86 |

| Mean-AcT | All-LN | 1.0 | 25.07 ± 0.20 | 38.68 ± 0.30 |

| Linear-AcT | All-LN | 1.0 | 26.00 ± 0.32 | 40.17 ± 0.24 |

| ActAdd | Post-LN | 0.8 | 22.40 ± 0.00 | 34.27 ± 0.00 |

| ITI-c | Post-LN | 8.0 | 23.16 ± 0.40 | 35.94 ± 0.55 |

| Mean-AcT | Post-LN | 1.0 | 21.93 ± 0.20 | 34.98 ± 0.25 |

| Linear-AcT | Post-LN | 1.0 | 22.45 ± 0.22 | 35.94 ± 0.36 |

| ActAdd | MLP | 3.0 | 23.01 ± 0.00 | 34.76 ± 0.00 |

| ITI-c | MLP | 2.0 | 24.53 ± 0.11 | 37.06 ± 0.38 |

| Mean-AcT | MLP | 1.0 | 21.98 ± 0.19 | 35.18 ± 0.31 |

| Linear-AcT | MLP | 1.0 | 21.93 ± 0.20 | 35.47 ± 0.25 |

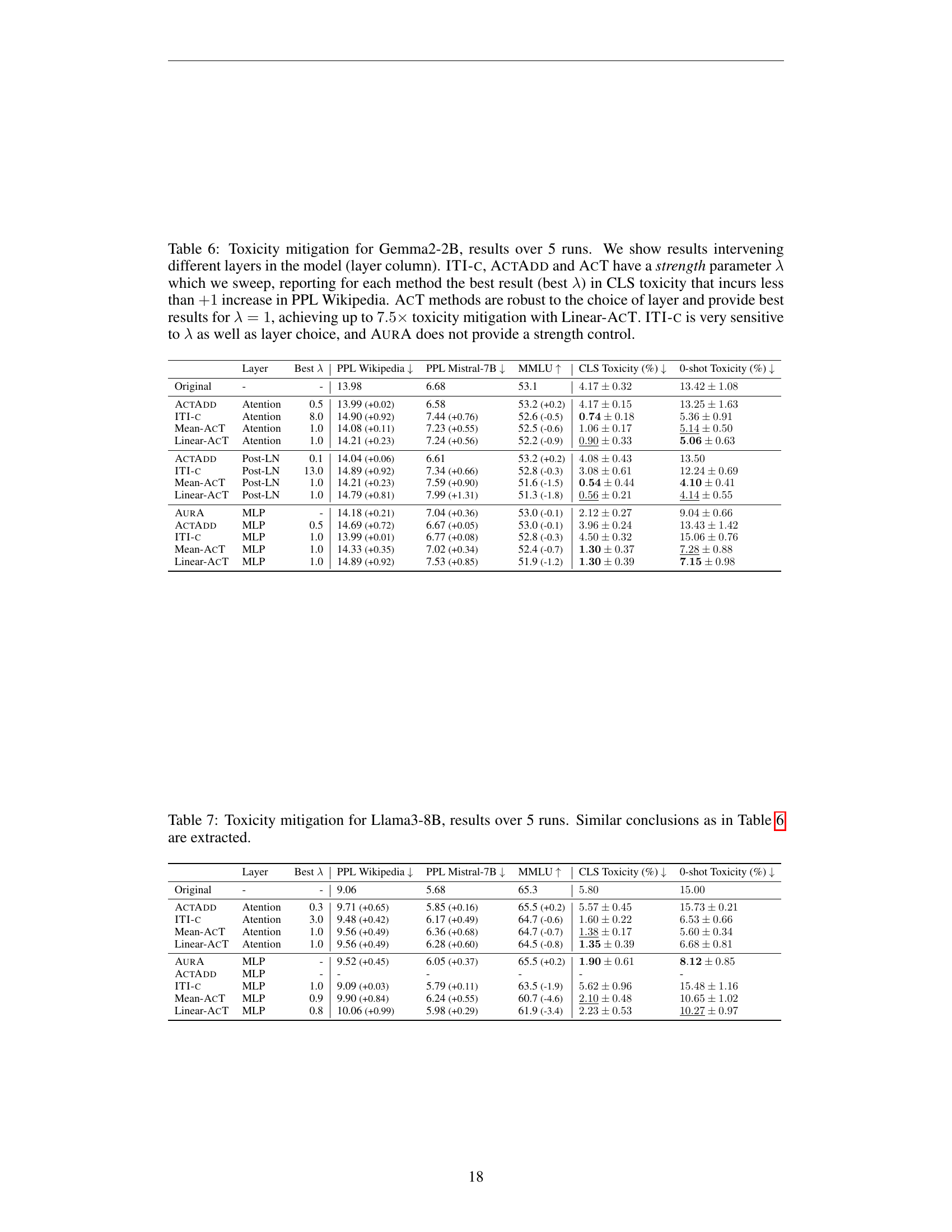

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the effectiveness of different methods for mitigating toxicity in the Gemma2-2B language model. The experiment was run five times for each method and layer, and each method’s performance was measured based on two metrics: the Classification Loss (CLS) of toxicity and the Perplexity (PPL) on Wikipedia text. The best result for each method was selected as the one that achieved the lowest CLS toxicity while keeping the increase in PPL to less than 1. The table shows that the Activation Transport (ACT) methods are robust to the choice of model layers and perform best at lambda = 1, greatly reducing toxicity. In contrast, the Inference-Time Intervention-Contrastive (ITI-C) method is shown to be very sensitive to the choice of model layer and lambda parameter. The AURA method is also included for comparison, but lacks a controllable strength parameter.

read the caption

Table 6: Toxicity mitigation for Gemma2-2B, results over 5 runs. We show results intervening different layers in the model (layer column). ITI-c, ActAdd and AcT have a strength parameter λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ which we sweep, reporting for each method the best result (best λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ) in CLS toxicity that incurs less than +11+1+ 1 increase in PPL Wikipedia. AcT methods are robust to the choice of layer and provide best results for λ=1𝜆1\lambda=1italic_λ = 1, achieving up to 7.5×7.5\times7.5 × toxicity mitigation with Linear-AcT. ITI-c is very sensitive to λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ as well as layer choice, and AurA does not provide a strength control.

| Layer | Best λ | MC1 Accuracy (%) ↑ | MC2 Accuracy (%) ↑ | MMLU Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Original | - | - | 25.46 | 40.27 |

| AurA | MLP | - | 25.34 ± 0.15 | 40.47 ± 0.20 |

| ActAdd | Attention | 0.7 | 26.19 ± 0.00 | 40.88 ± 0.00 |

| ITI-c | Attention | 1.0 | 27.42 ± 0.30 | 42.01 ± 0.42 |

| Mean-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 26.73 ± 0.19 | 42.20 ± 0.24 |

| Linear-AcT | Attention | 1.0 | 27.17 ± 0.23 | 42.15 ± 0.31 |

| ActAdd | All-LN | 1.0 | 25.58 ± 0.00 | 41.00 ± 0.00 |

| ITI-c | All-LN | 3.0 | 29.65 ± 0.71 | 44.43 ± 0.56 |

| Mean-AcT | All-LN | 1.0 | 32.88 ± 0.54 | 48.23 ± 0.64 |

| Linear-AcT | All-LN | 1.0 | 33.22 ± 0.22 | 48.69 ± 0.34 |

| ActAdd | MLP | 0.5 | 25.46 ± 0.00 | 40.64 ± 0.00 |

| ITI-c | MLP | 2.0 | 30.11 ± 0.60 | 45.41 ± 0.24 |

| Mean-AcT | MLP | 1.0 | 26.17 ± 0.24 | 41.27 ± 0.34 |

| Linear-AcT | MLP | 1.0 | 26.41 ± 0.52 | 39.34 ± 0.54 |

🔼 This table presents the results of toxicity mitigation experiments conducted on the Llama3-8B language model. Five runs were performed for each method and layer, and the results show the reduction in toxicity levels while keeping the performance of the model mostly unchanged. The table compares different methods (Linear-ACT, Mean-ACT, ITI-C, ACTADD, AURA), layers in the model (Attention, Post-LN, MLP), and the impact on various metrics such as toxicity (CLS and 0-shot), perplexity, and MMLU accuracy.

read the caption

Table 7: Toxicity mitigation for Llama3-8B, results over 5 runs. Similar conclusions as in Table 6 are extracted.

🔼 This table presents text samples generated by the model, illustrating how different strengths of the Linear-ACT and ITI-C methods influence the generation of text related to the concept of ‘football.’ Each row shows the generated text for a specific method and strength parameter (λ). The purpose is to demonstrate how these methods can be tuned to control the degree to which the generated text is about football.

read the caption

Table 8: Generations at different λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ inducing concept Football.

🔼 This table presents several text generations from the Gemma2-2B large language model (LLM) using the Activation Transport (ACT) method. Each row shows a generation with varying strength (λ) of concept induction for the concept ‘Flower’. The baseline generation (λ = 0) shows a typical story, whereas increasing λ values gradually introduce the ‘Flower’ concept into the narrative, culminating in a story heavily focused on flowers (λ = 1.0). The table illustrates the method’s ability to precisely control the strength of concept insertion into the generated text.

read the caption

Table 9: Generations at different λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ inducing concept Flower.

Full paper#