TL;DR#

Molecular machine learning often struggles with multi-modal tasks involving both text and molecules. Existing graph-based methods lack interpretability and compatibility. Cross-modal contrastive learning approaches show promise but fall short in open-ended molecule-to-text generation. This paper introduces LLaMo, a novel large molecular graph-language model designed to overcome these limitations.

LLaMo uses a multi-level graph projector to transform graph representations into tokens, which are then processed by a large language model. The model is instruction-tuned using machine-generated molecular graph instruction data, enhancing its instruction-following capabilities and general-purpose molecule understanding. Experiments demonstrate LLaMo’s superior performance on tasks such as molecular description generation, property prediction, and IUPAC name prediction, outperforming existing LLM-based methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in molecular machine learning and large language models. It bridges the gap between language and graph modalities, opening avenues for multi-modal molecular tasks. The novel multi-level graph projector and the GPT-4 generated instruction data significantly improve model performance. This work inspires new research directions in molecular representation and instruction tuning, advancing the field toward more sophisticated molecular graph-language models.

Visual Insights#

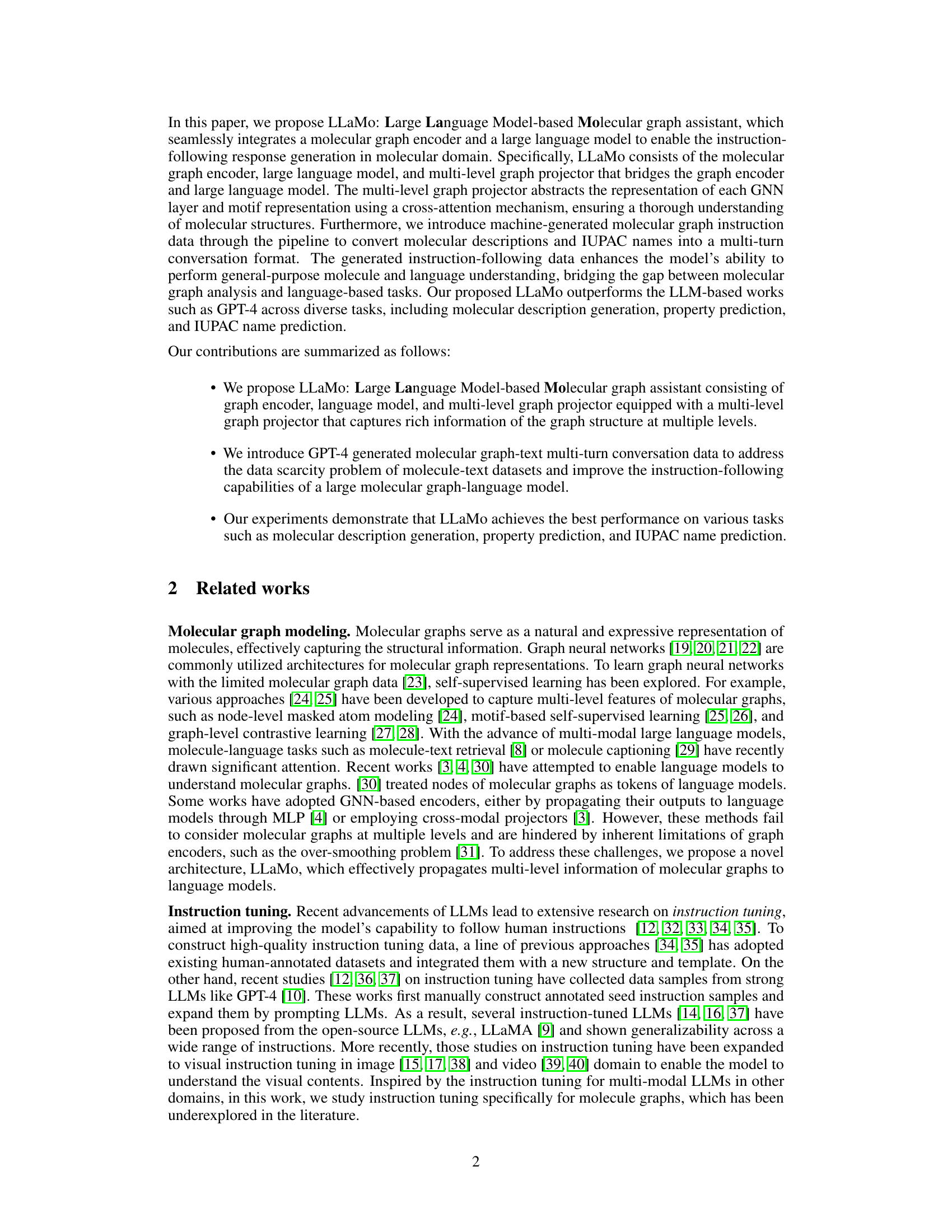

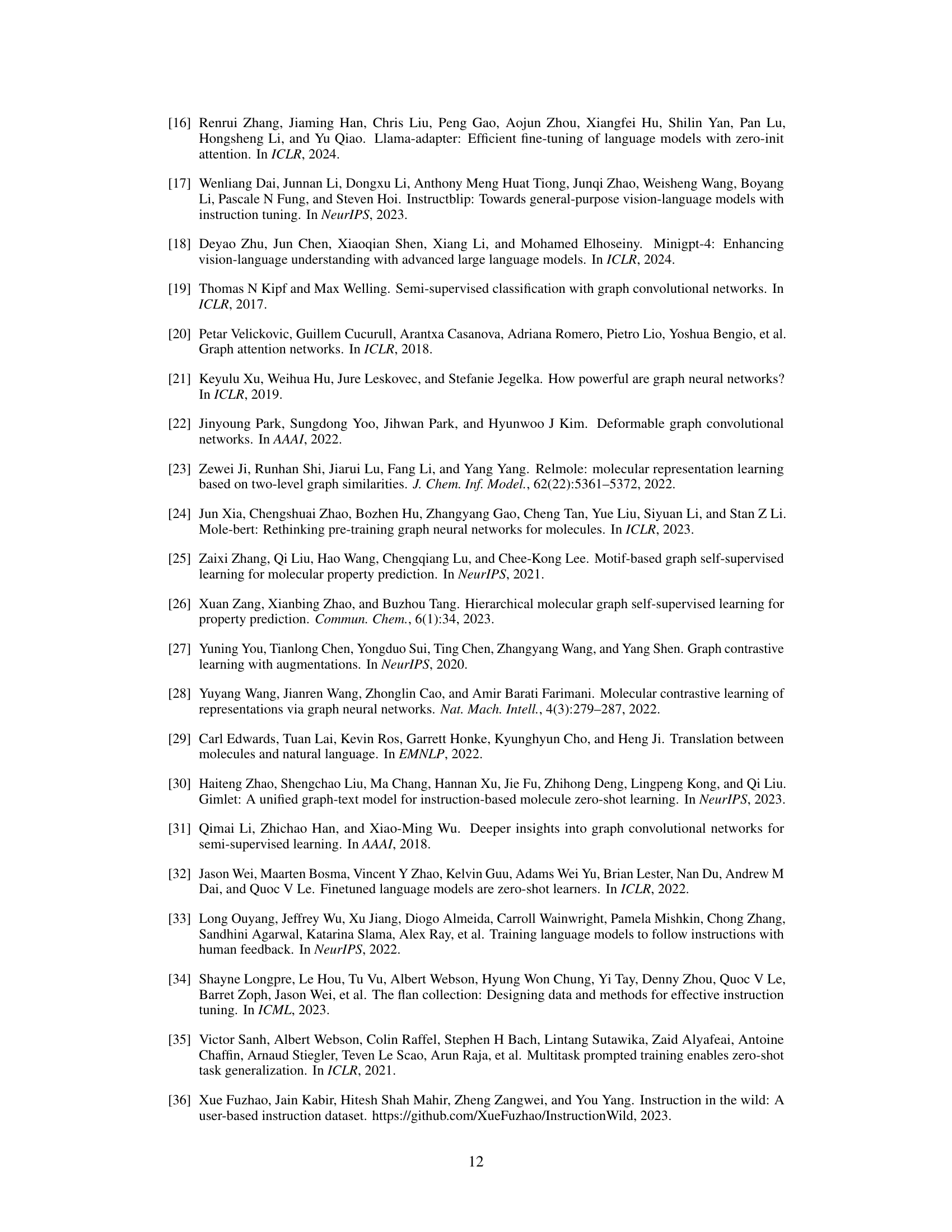

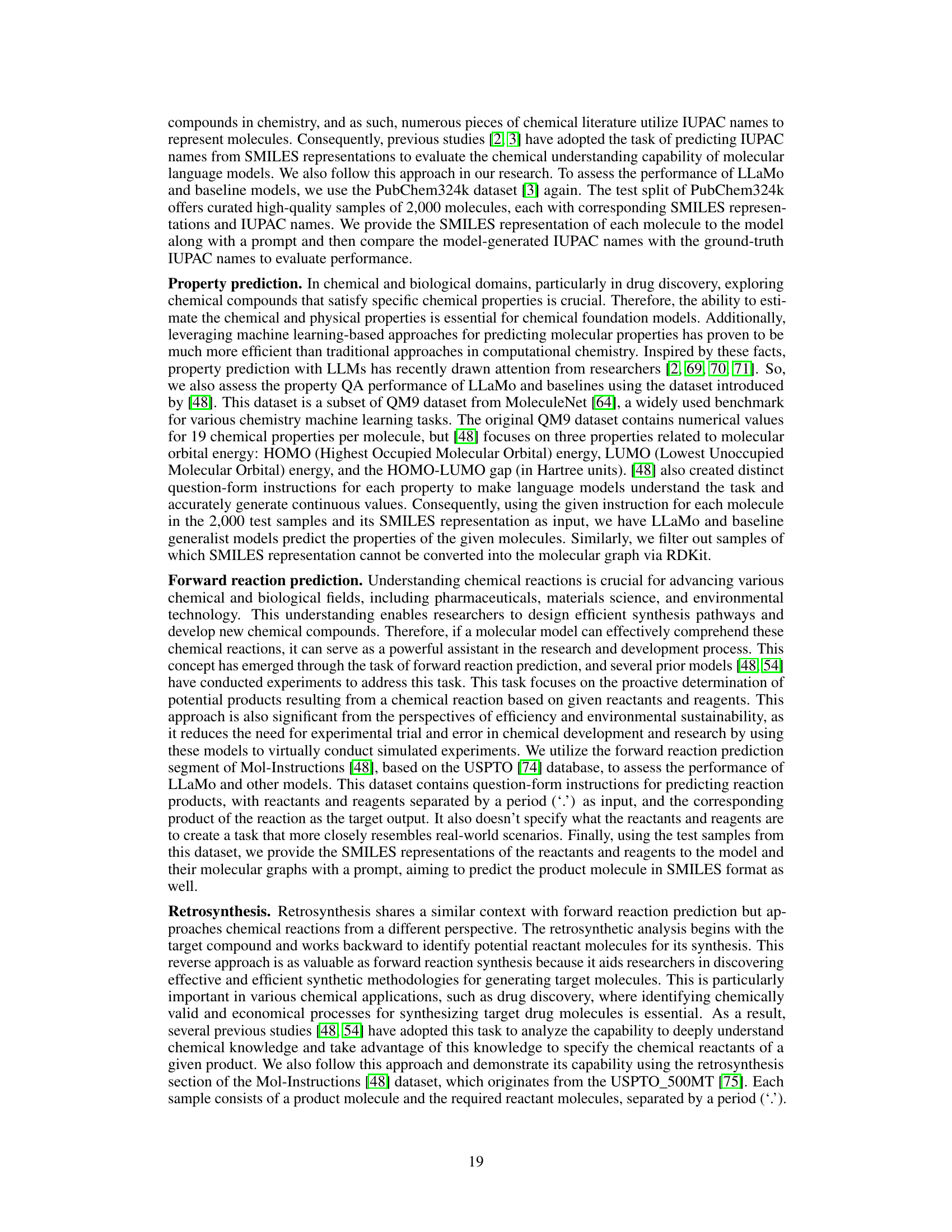

🔼 LLaMo is composed of three main parts: a graph neural network (GNN) to encode a 2D molecular graph, a multi-level graph projector to transform the encoded graph into tokens usable by the language model, and a large language model (LLM) to generate the final response. The process begins with inputting a 2D molecular graph and its SMILES representation. The GNN processes the graph. The multi-level graph projector converts the GNN’s output into a format the LLM understands, combining information from multiple layers of the GNN. Finally, the LLM generates a response based on the processed graph tokens, SMILES, and instructions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overall framework of LLaMo. LLaMo consists of a graph neural network, a multi-level graph projector, and a large language model. It first encodes an input 2D molecular graph with the graph neural network and then converts the encoded graph into molecular graph tokens with the multi-level graph projector. Finally, the large language model generates the instruction-following response given the input SMILES, graph tokens, and the instruction.

| Context type 1: SMILES representation | |

|---|---|

| CCCCC(C)/C=C(\C)/C=C/C(=O)NC1=CC@(/C=C/C=C/C=C/C(=O)NC2 | |

| =C(CCC2=O)O)O | |

| Context type 2: Description | |

| — | — |

| The molecule is a polyene antibiotic that is TMC-1A in which the 2,4-dimethyloct-2-enoyl group has been replaced by an (E,E)-4,6-dimethyldeca-2,4-dienoyl group. TMC-1C is an antitumour antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces sp. A-230… | |

| Context type 3: IUPAC name | |

| — | — |

| (2E,4E)-N-[(3S,4R)-3,4-dihydroxy-3-[(1E,3E,5E)-7-[(2-hydroxy-5-oxocyclopenten-1-yl)amino]-7-oxohepta-1,3,5-trienyl]-6-oxocyclohexen-1-yl]-4,6-dimethyldeca-2,4-dienamide | |

| Response: Multi-turn conversation | |

| — | — |

| Question: | |

| What is the IUPAC name of the molecule you are analyzing? | |

| === | |

| Answer: | |

| The IUPAC name of the molecule is (2E,4E)-N-[(3S,4R)-3,4-dihydroxy-3-[(1E,3E,5E)-7-[(2-hydroxy-5-oxocyclopenten-1-yl)amino]-7-oxohepta-1,3,5-trienyl]-6-oxocyclohexen-1-yl]-4,6-dimethyldeca-2,4-dienamide. | |

| === | |

| Question: | |

| Can you identify the type of acid or base this molecule can act as in a reaction? | |

| === | |

| Answer: | |

| This molecule can act as a weak acid due to the presence of the carboxylic acid group. |

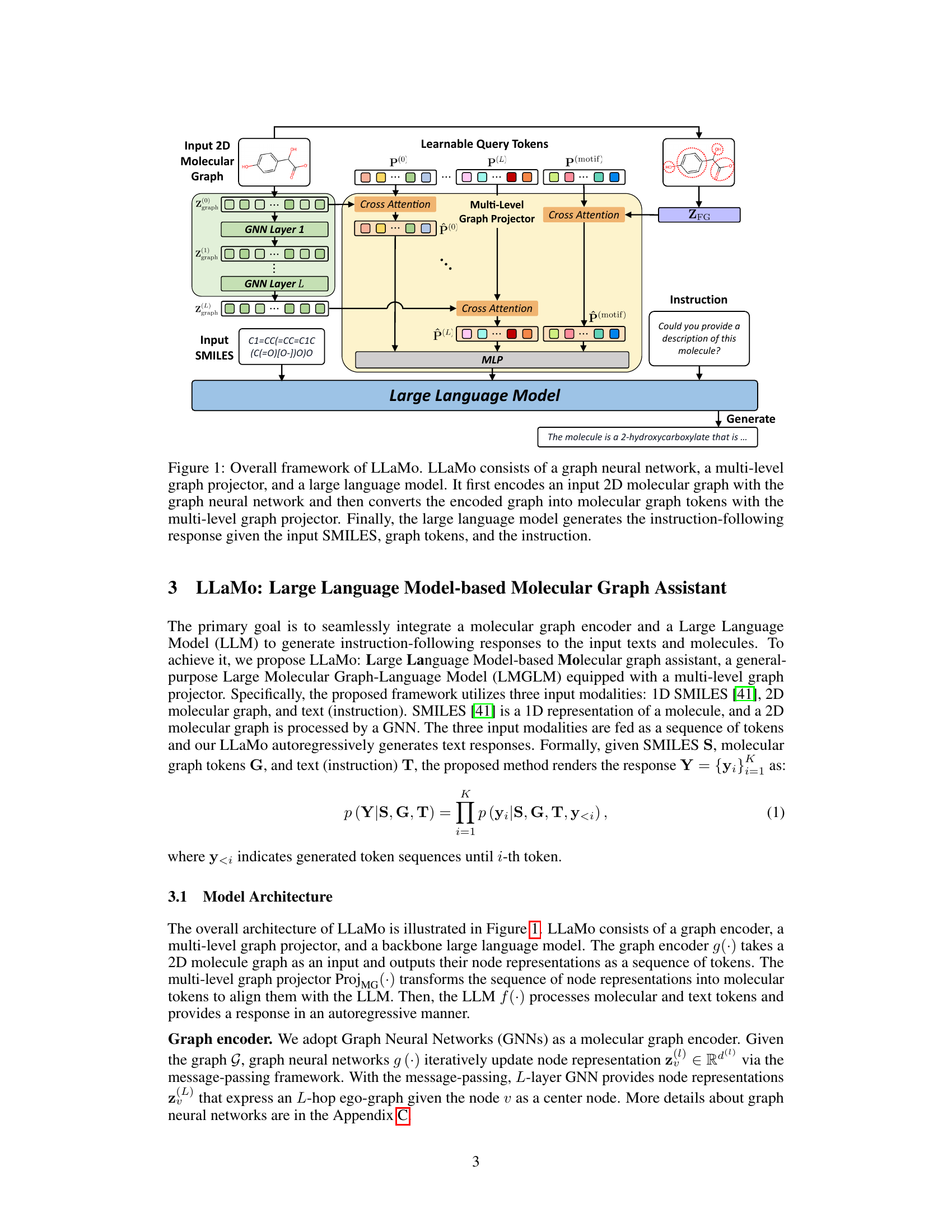

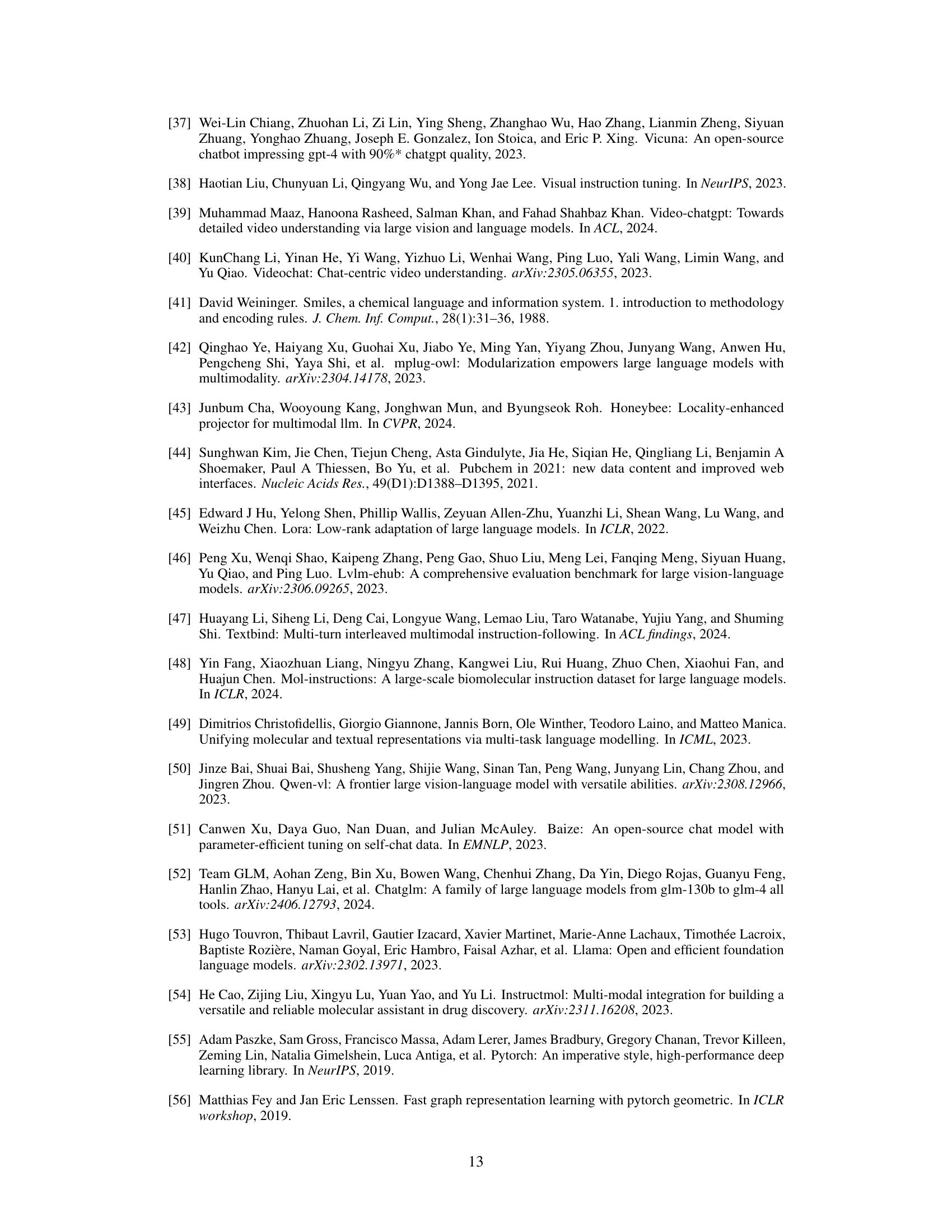

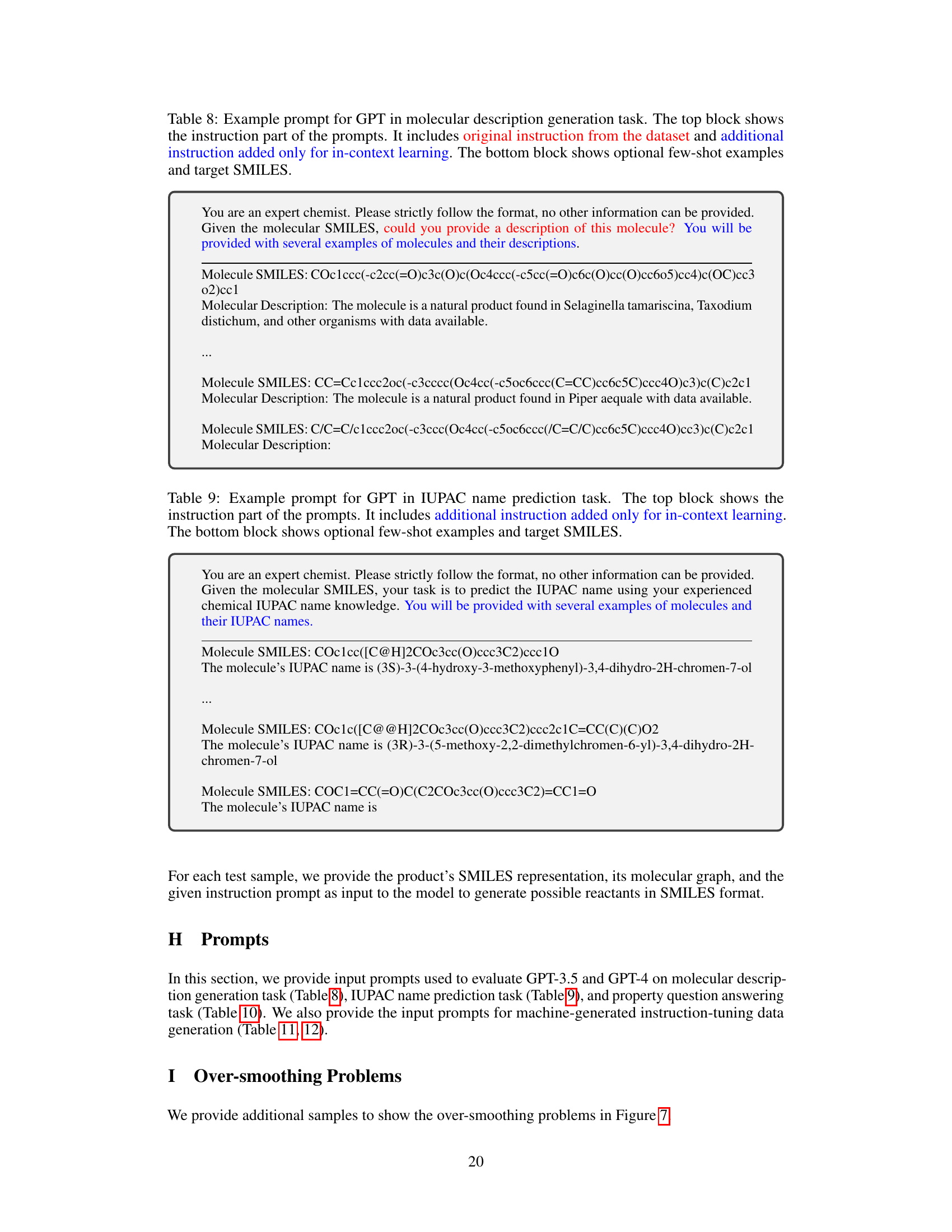

🔼 This table showcases an example of the instruction-following data used to train the LLaMo model. The top section presents the input context provided to GPT-4, including the SMILES notation for a molecule, its description, and its IUPAC name. The bottom section displays the GPT-4’s response, illustrating the model’s ability to engage in a multi-turn conversation and answer questions related to the provided molecule information.

read the caption

Table 1: One example to illustrate the instruction-following data. The top block shows the contexts such as SMILES, description, and IUPAC name used to prompt GPT, and the bottom block shows the response of GPT-4.

In-depth insights#

LLaMo’s Architecture#

LLaMo’s architecture is a multi-modal model designed to bridge the gap between molecular graphs and natural language. It cleverly integrates a graph neural network (GNN) for encoding the 2D molecular graph structure, a large language model (LLM) for generating natural language responses, and a crucial component: the multi-level graph projector. This projector is key, transforming the GNN’s hierarchical representations into graph tokens that the LLM can effectively process. The incorporation of both node-level and motif-level information into these graph tokens is a significant advancement, enabling a more nuanced understanding of molecular structures than previous single-level approaches. The use of instruction tuning, combined with the innovative GPT-4 generated data, further enhances the model’s capability in generating coherent and accurate molecular descriptions and addressing various language-based tasks. This end-to-end architecture allows LLaMo to seamlessly integrate different data types, leading to improved overall performance.

Multi-level Graph#

The concept of a “Multi-level Graph” in the context of molecular machine learning suggests a representation that captures molecular structure at multiple granularities. Instead of a single graph, multiple graph layers or representations are used to incorporate information from different scales, such as individual atoms, functional groups, or the entire molecule. This approach addresses the limitations of traditional graph-based methods, which often struggle to capture both local and global structural details. A multi-level graph representation would allow for the integration of multiple levels of information within a large language model (LLM), allowing the model to capture and relate various features more effectively. The key benefit is enhanced model interpretability and performance on various tasks, including property prediction, description generation, and reaction prediction.

Instruction Tuning#

Instruction tuning, a crucial technique in the advancement of large language models (LLMs), focuses on aligning the model’s behavior with user instructions. This involves training LLMs on a dataset of instructions paired with desired outputs, effectively teaching the model to follow instructions of varying complexity and nuance. Unlike traditional fine-tuning, which often focuses on specific tasks, instruction tuning aims for general-purpose instruction-following capabilities, enabling the model to adapt to novel instructions with minimal further training. The success of instruction tuning hinges on the quality and diversity of the instruction dataset; high-quality data, including multi-turn conversations, significantly enhances the model’s ability to understand and respond to complex, open-ended requests. Furthermore, techniques like prompt engineering are often employed to enhance instruction clarity and specificity, allowing the model to produce more coherent and accurate responses. Addressing limitations associated with instruction tuning data scarcity and potential biases is crucial for continued development of reliable and robust LLMs.

Experimental Setup#

A well-defined Experimental Setup section is crucial for reproducibility and understanding. It should detail the datasets used, specifying their size, preprocessing steps (if any), and any relevant characteristics. The choice of evaluation metrics must be justified, highlighting their suitability for the specific task. Hardware and software specifications, including the computing platform (e.g., cloud, local), type of processors, memory, and any specialized libraries used, should be included for reproducibility. Hyperparameter settings and their optimization strategy (e.g., grid search, random search, Bayesian optimization) must be meticulously documented. If specific model architectures were employed, their configurations should be clearly described. Finally, the random seed used for any stochastic processes (e.g., data shuffling, model initialization) is critical for ensuring consistent experimental results across replications.

LLaMo Limitations#

LLaMo, while innovative, faces limitations stemming from its reliance on pre-trained LLMs. Data leakage is a concern, as the pre-training data of LLMs may overlap with benchmark datasets, affecting the model’s performance. The inherent limitations of LLMs, such as high computational costs and the tendency towards hallucination, are also inherited by LLaMo. Over-smoothing in the graph neural network may also impact the model’s ability to capture fine-grained details, which needs further investigation. Addressing these limitations could enhance LLaMo’s reliability and extend its capabilities in molecular understanding. Future work should focus on mitigating data leakage and improving the robustness of the underlying GNN architecture for more accurate molecular representations. Furthermore, exploration of alternative training methods to lessen the reliance on large LLMs is warranted.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure visualizes the node representations learned by a graph neural network (GNN) at different layers (1, 2, 4, and 5). Each subfigure represents the node embeddings for a specific layer. As the number of layers in the GNN increases, the node representations tend to converge towards similar values, which is known as the ‘over-smoothing’ problem. This phenomenon reduces the GNN’s capability to distinguish between different nodes and limits its ability to capture the nuanced characteristics within the molecular graph.

read the caption

Figure 2: Node representations of graph encoder with 1,2,4,5 layers. As the number of layers increases, node representations collapse.

🔼 This figure illustrates the first stage of a two-stage training pipeline for the LLaMo model. Stage 1 focuses on aligning the molecular graph encoder and the large language model. The graph encoder processes a 2D molecular graph, and a multi-level graph projector transforms the resulting node representations into molecular graph tokens, enabling alignment with the large language model. The language model is frozen during this stage; only the graph encoder and projector are trained. The training objective is to learn effective graph-to-text mappings, improving the model’s overall understanding of molecular structures and their language descriptions.

read the caption

(a) Stage 1: graph-language alignment

🔼 In the second stage of the two-stage training pipeline, the large language model (LLM) is fine-tuned using LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation). The multi-level graph projector continues to be trained concurrently. This stage focuses on improving the model’s instruction-following capabilities and enhancing its understanding of molecular graphs. The instruction-following response generation is used as the training objective.

read the caption

(b) Stage 2: instruction-tuning

🔼 LLaMo’s training is divided into two stages. Stage 1 pre-trains the graph encoder and multi-level graph projector to align graph and language representations. Stage 2 fine-tunes the large language model (LLM) using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA), while continuing to train the projector. Both stages use instruction-following response generation for training.

read the caption

Figure 3: Two-stage training pipeline. Stage 1 involves training the graph encoder, and stage 2 entails fine-tuning the LLM using LoRA. In both stages, the multi-level graph projector is continuously trained. All training processes are performed by generating the instruction-following response.

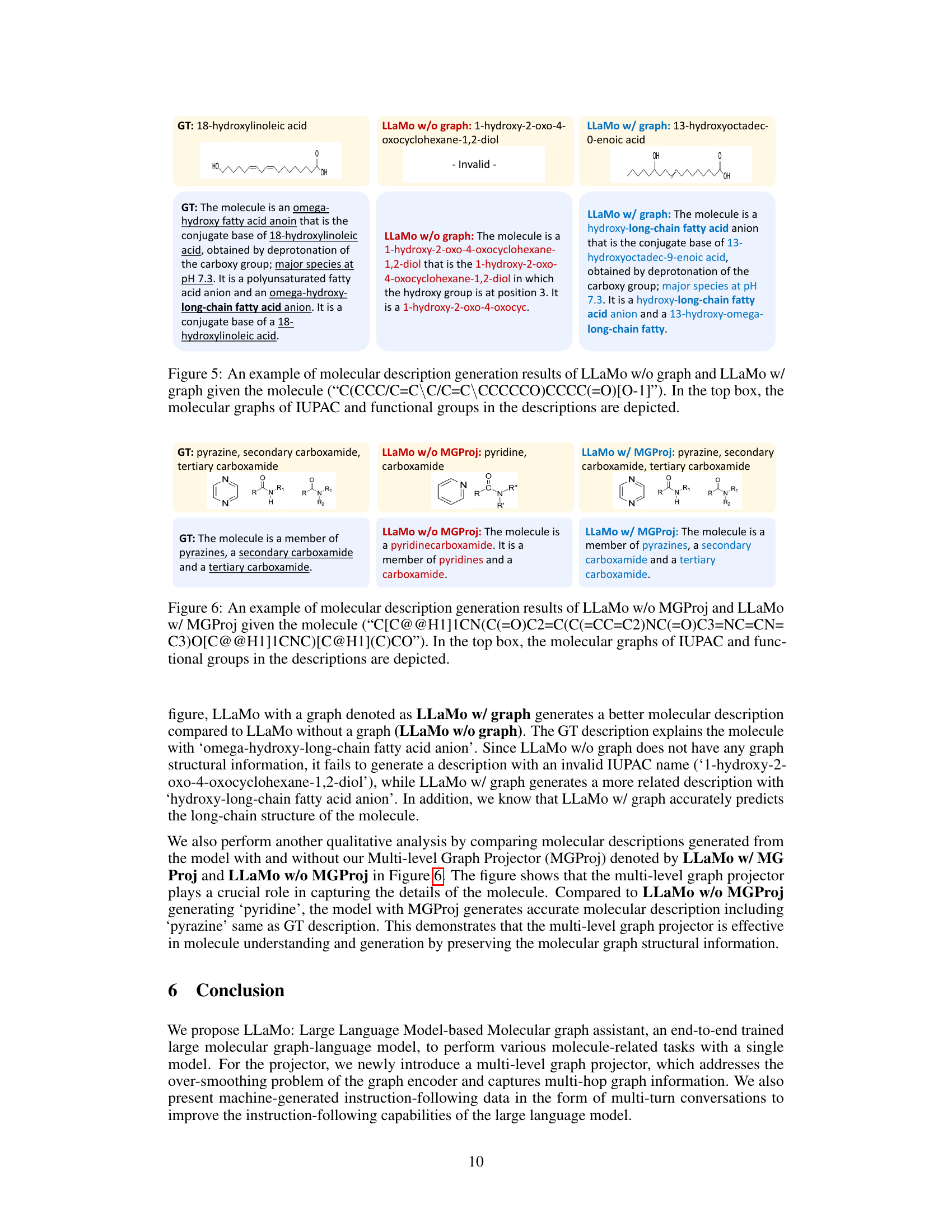

🔼 Figure 4 visualizes attention mechanisms within the LLaMo model for generating captions of varying detail levels. The left panel shows attention weights when producing a coarse-grained caption (high-level overview), and the right panel shows attention weights when generating a fine-grained caption (detailed description). The visualization demonstrates that the model focuses more on high-level features (e.g., overall molecular structure) for coarse captions, and shifts to low-level features (e.g., specific atom and bond details) when generating fine-grained descriptions.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of attention maps for samples with coarse-grained caption (left) and fine-grained caption (right). The attention scores of high-level features are relatively high when generating coarse-grained captions, whereas those of low-level features are high for fine-grained captions.

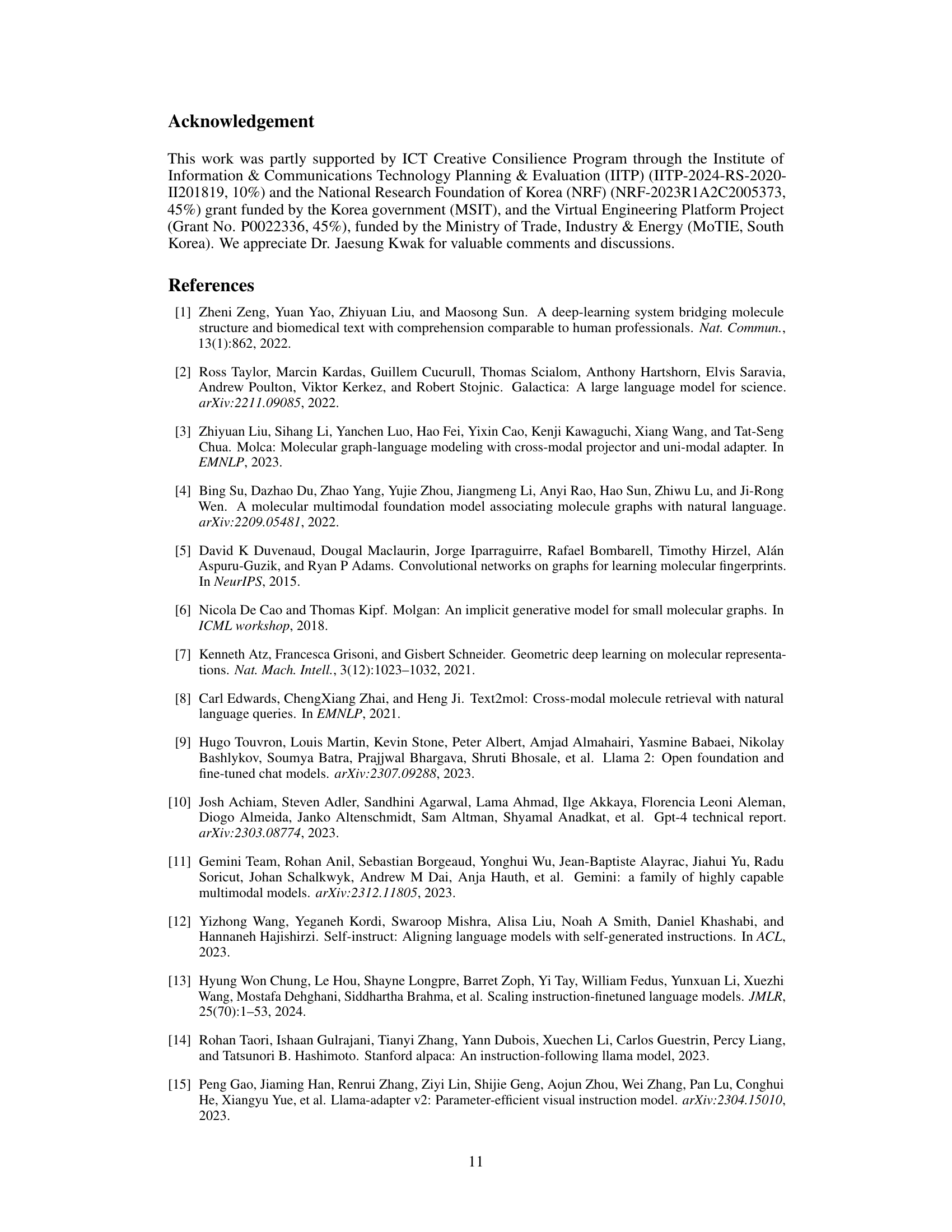

🔼 Figure 5 presents a comparison of molecular description generation results between two versions of the LLaMo model: one trained without molecular graph data (LLaMo w/o graph) and another trained with it (LLaMo w/ graph). The input molecule is represented using the SMILES string “C(CCC/C=C\C/C=C\CCCCCO)CCCC(=O)[O-1]”. The figure highlights the difference in the generated descriptions. The top section of the figure visually depicts the molecular graph, the IUPAC name, and the key functional groups used in the generated descriptions for both model versions, aiding in understanding how the presence of molecular graph information impacts the LLaMo model’s descriptive capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 5: An example of molecular description generation results of LLaMo w/o graph and LLaMo w/ graph given the molecule (“C(CCC/C=C\\\backslash\C/C=C\\\backslash\CCCCCO)CCCC(=O)[O-1]”). In the top box, the molecular graphs of IUPAC and functional groups in the descriptions are depicted.

🔼 This figure compares the molecular description generation results between two versions of the LLaMo model: one without the multi-level graph projector (LLaMo w/o MGProj) and one with it (LLaMo w/ MGProj). The input molecule, represented by its SMILES string ‘C[C@@H1]1CN(C(=O)C2=C(C(=CC=C2)NC(=O)C3=NC=CN=C3)O[C@@H1]1CNC)C@H1CO’, is processed by both models. The top section of the figure shows the input molecule’s structure visualized as a graph, along with highlighted functional groups relevant to the descriptions generated by the models. This visualization helps to understand how the models interpret and represent the molecule. The generated descriptions from both models are then presented, illustrating the influence of the multi-level graph projector on the quality and detail of the generated descriptions. The comparison showcases how integrating a multi-level graph projector allows the model to provide richer, more accurate, and chemically meaningful descriptions.

read the caption

Figure 6: An example of molecular description generation results of LLaMo w/o MGProj and LLaMo w/ MGProj given the molecule (“C[C@@H1]1CN(C(=O)C2=C(C(=CC=C2)NC(=O)C3=NC=CN= C3)O[C@@H1]1CNC)[C@H1](C)CO”). In the top box, the molecular graphs of IUPAC and functional groups in the descriptions are depicted.

🔼 This figure visualizes the node representations learned by a graph neural network (GNN) at different layers (1, 2, 4, and 5). Each sub-figure shows the node representations as points in a multi-dimensional space. The main observation is that as the number of layers in the GNN increases, the node representations tend to converge or ‘collapse’ towards a central point, losing their individual distinctiveness and potentially hindering the network’s ability to discriminate between different nodes or structural features within the graph.

read the caption

Figure 7: Node representations of graph encoder with 1,2,4,5 layers. As the number of layers increases, node representations collapse.

🔼 Figure 8 presents a comparison of molecular description generation results between two models: LLaMo with graph and LLaMo without graph. The input molecule, represented by its SMILES string ‘CCCCCC@@H1O)’, is identical for both models. The figure showcases how the inclusion of the molecular graph in LLaMo significantly improves the accuracy and detail of the generated description. The descriptions generated by both models are presented alongside the input molecule’s structure, allowing for visual inspection and comparison. The results highlight the importance of incorporating molecular graph information into large language models for more effective and accurate understanding and generation of molecule descriptions.

read the caption

Figure 8: An example of molecular description generation results of LLaMo w/o graph and LLaMo w/ graph given the molecule “CCCCC[C@@H1](CC[C@H1]1[C@@H1](C[C@@H1]([C@@H1] 1C/C=C\\\backslash\CCCC(=O)[O-1])O)O)O)”.

More on tables

| Projector | Molecule description BLEU ( ) ) | Molecule description METEOR ( ) ) | IUPAC prediction BLEU ( ) ) | IUPAC prediction METEOR ( ) ) | Property QA MAE ( ) ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o Graph | 26.1 | 56.6 | 36.3 | 62.2 | 0.013 |

| MLP (w/ low-level) | 32.4 | 62.1 | 42.2 | 68.4 | 0.009 |

| MLP (w/ high-level) | 33.8 | 63.4 | 45.5 | 67.4 | 0.008 |

| MLP (w/ concat) | 34.8 | 64.1 | 47.1 | 70.2 | 0.007 |

| Resampler | 34.4 | 62.8 | 43.4 | 65.2 | 0.009 |

| MGProj (w/o motif) | 36.1 | 65.3 | 48.8 | 69.8 | 0.008 |

| MGProj (Ours) | 37.8 | 66.1 | 49.6 | 70.9 | 0.007 |

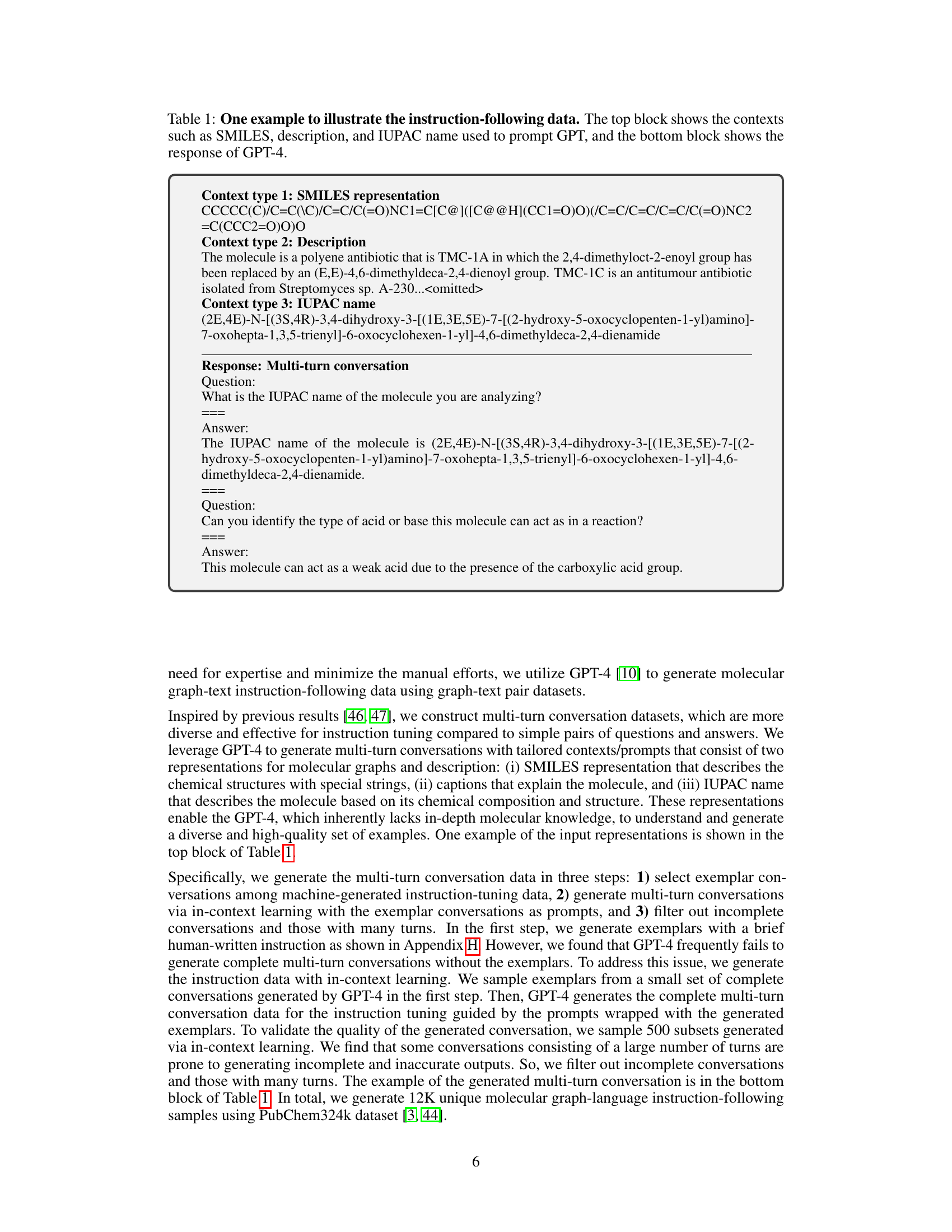

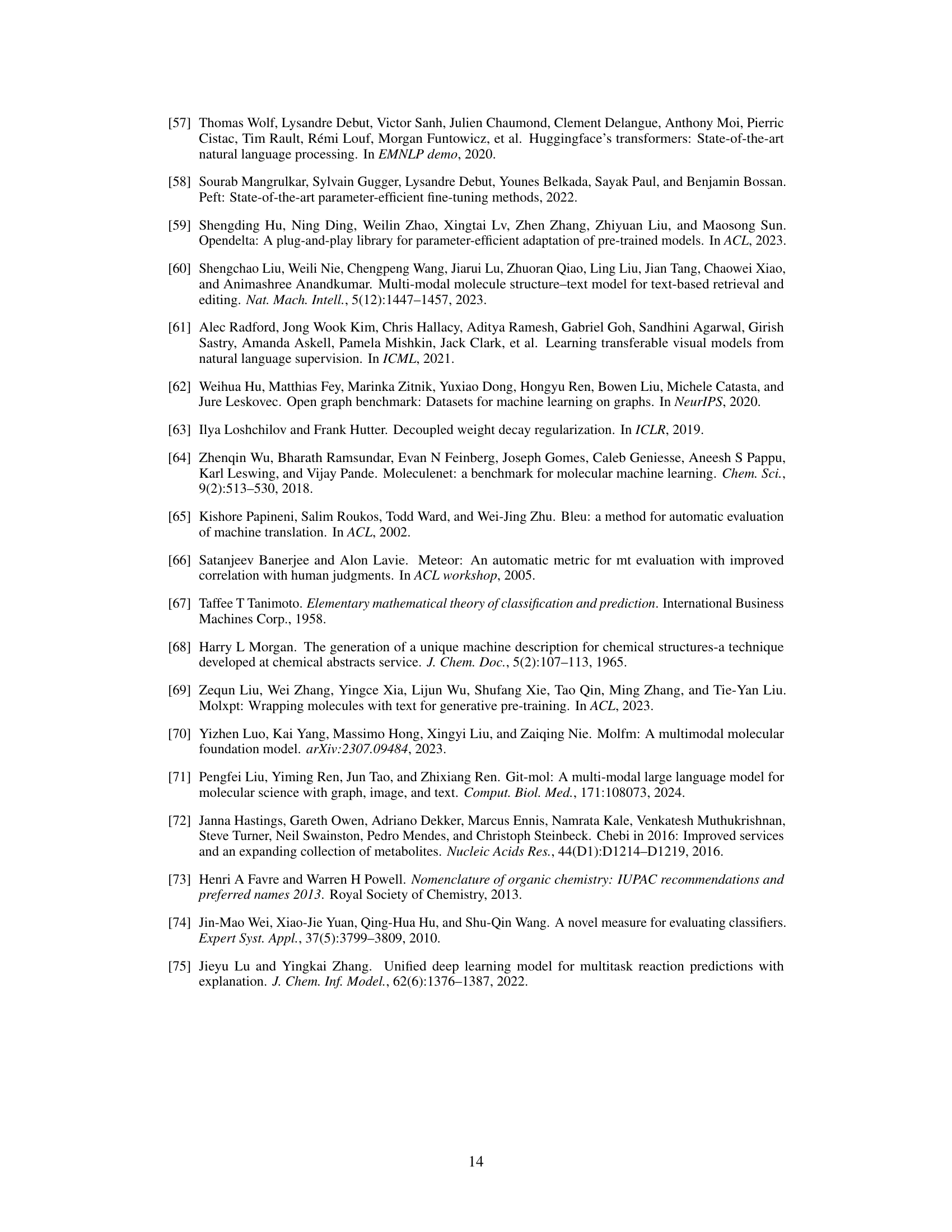

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of various generalist models on three molecular tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC name prediction, and property prediction. The performance is measured using metrics appropriate for each task (BLEU, METEOR, MAE). The models are categorized and compared, showing the impact of instruction tuning, and highlighting a model’s ability to handle all three tasks simultaneously versus specializing in one. Specific model variations are noted, along with sources for experimental results where applicable.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance (%) of generalist models on three tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC prediction, and property prediction. Mol. Inst. tuned denotes the molecular instruction-tuned model. ∗*∗ The result is not available since LLaMA2 fails generating numerical outputs. ††\dagger† denotes the experimental results drawn from Mol-Instruction [48].

| Model | Exact↑ | BLEU↑ | Levenshtein↓ | RDK FTS↑ | MACCS FTS↑ | Morgan FTS↑ | Validity↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpaca† [14] | 0.000 | 0.065 | 41.989 | 0.004 | 0.024 | 0.008 | 0.138 |

| Baize† [51] | 0.000 | 0.044 | 41.500 | 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.097 |

| ChatGLM† [52] | 0.000 | 0.183 | 40.008 | 0.050 | 0.100 | 0.044 | 0.108 |

| LLaMA† [53] | 0.000 | 0.020 | 42.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.039 |

| Vicuna† [37] | 0.000 | 0.057 | 41.690 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.059 |

| LLaMA∗ [53] | 0.012 | 0.804 | 29.947 | 0.499 | 0.649 | 0.407 | 1.000 |

| Mol-Instruction [48] | 0.045 | 0.654 | 27.262 | 0.313 | 0.509 | 0.262 | 1.000 |

| InstructMol-G [54] | 0.153 | 0.906 | 20.155 | 0.519 | 0.717 | 0.457 | 1.000 |

| InstructMol-GS [54] | 0.536 | 0.967 | 10.851 | 0.776 | 0.878 | 0.741 | 1.000 |

| LLaMo (Ours) | 0.584 | 0.894 | 6.162 | 0.857 | 0.918 | 0.841 | 0.938 |

| Alpaca† [14] | 0.000 | 0.063 | 46.915 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.007 | 0.160 |

| Baize† [51] | 0.000 | 0.095 | 44.714 | 0.025 | 0.050 | 0.023 | 0.112 |

| ChatGLM† [52] | 0.000 | 0.117 | 48.365 | 0.056 | 0.075 | 0.043 | 0.046 |

| LLaMA† [53] | 0.000 | 0.036 | 46.844 | 0.018 | 0.029 | 0.017 | 0.010 |

| Vicuna† [37] | 0.000 | 0.057 | 46.877 | 0.025 | 0.030 | 0.021 | 0.017 |

| LLaMA∗ [53] | 0.000 | 0.283 | 53.510 | 0.136 | 0.294 | 0.106 | 1.000 |

| Mol-Instruction [48] | 0.009 | 0.705 | 31.227 | 0.283 | 0.487 | 0.230 | 1.000 |

| InstructMol-G [54] | 0.114 | 0.586 | 21.271 | 0.422 | 0.523 | 0.285 | 1.000 |

| InstructMol-GS [54] | 0.407 | 0.941 | 13.967 | 0.753 | 0.852 | 0.714 | 1.000 |

| LLaMo (Ours) | 0.341 | 0.830 | 12.263 | 0.793 | 0.868 | 0.750 | 0.954 |

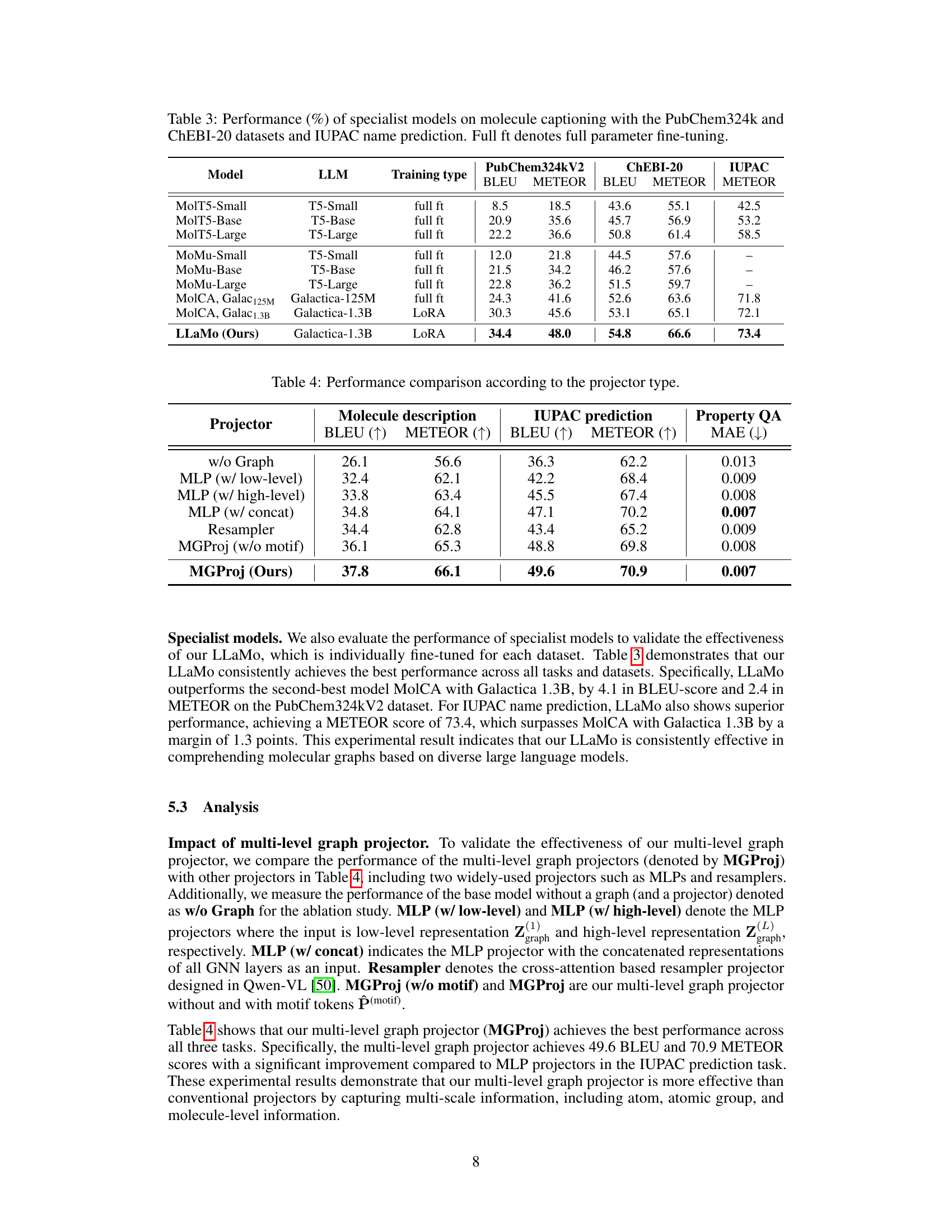

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of various specialist models on two tasks: molecule captioning and IUPAC name prediction. The models are evaluated using the PubChem324k and ChEBI-20 datasets for molecule captioning, and a separate dataset for IUPAC name prediction. Performance is measured using BLEU and METEOR scores. The ‘Full ft’ column indicates whether the model used full parameter fine-tuning or a more efficient method.

read the caption

Table 3: Performance (%) of specialist models on molecule captioning with the PubChem324k and ChEBI-20 datasets and IUPAC name prediction. Full ft denotes full parameter fine-tuning.

| Molecule SMILES | The molecule’s IUPAC name |

|---|---|

| COc1cc([C@H]2COc3cc(O)ccc3C2)ccc1O | (3S)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-chromen-7-ol |

| COc1c([C@@H]2COc3cc(O)ccc3C2)ccc2c1C=CC(C)(C)O2 | (3R)-3-(5-methoxy-2,2-dimethylchromen-6-yl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-chromen-7-ol |

| COC1=CC(=O)C(C2COc3cc(O)ccc3C2)=CC1=O |

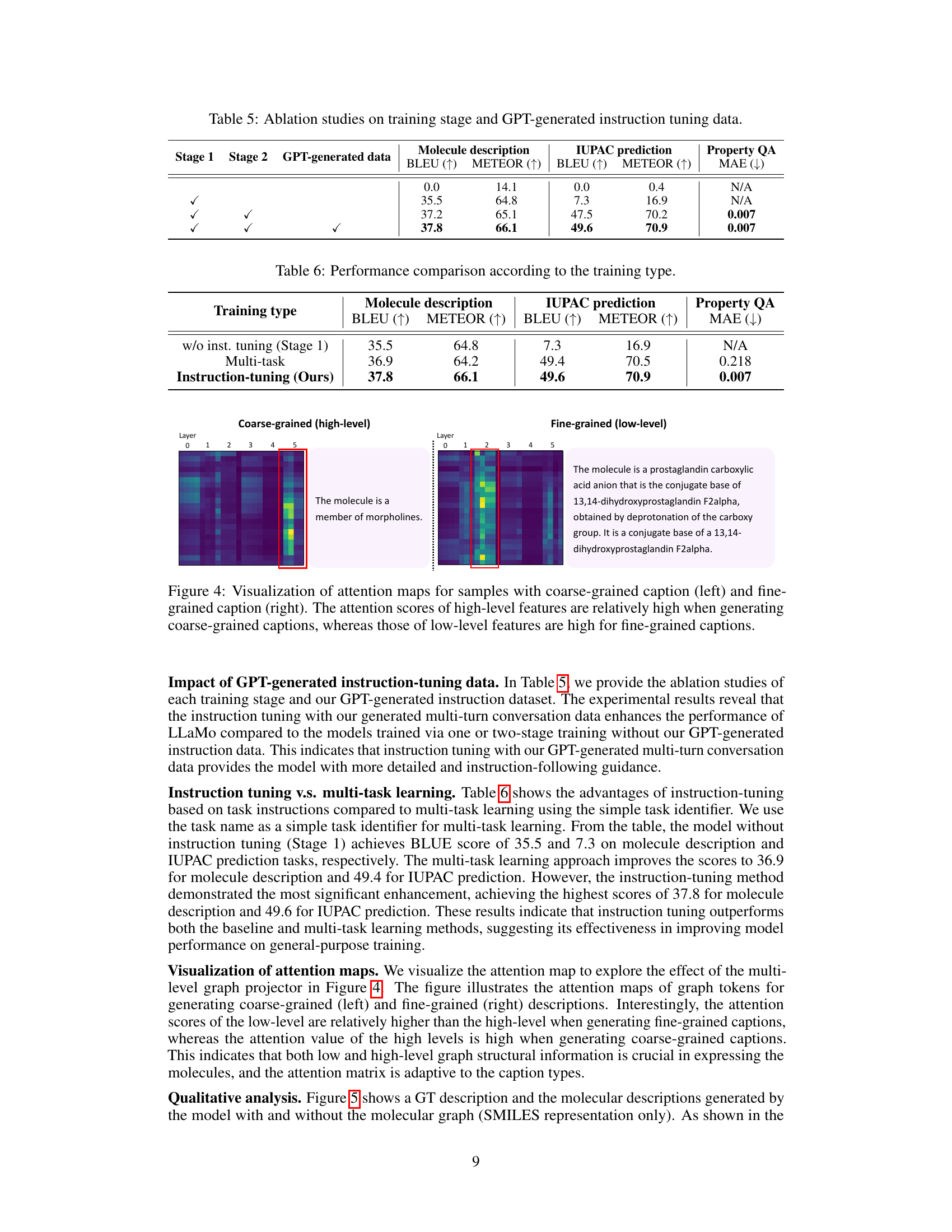

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different types of graph projectors used in the LLaMo model. It shows the results for three tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC prediction, and property prediction (using MAE). The table compares the performance of models with no graph projector, MLP-based projectors (with low-level, high-level, and concatenated inputs), a resampler projector, and the proposed multi-level graph projector (MGProj) with and without motif information.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance comparison according to the projector type.

| Molecule SMILES | Output Value |

|---|---|

| COCC12OC3CC1C32 | 0.2967 |

| OCCC12CC3C(O1)C32 | 0.305 |

| CCC1C2OC3C1C23C |

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of different training stages and the use of GPT-generated instruction tuning data on the performance of the LLaMo model. It shows how each training stage (Stage 1 and Stage 2) and the inclusion or exclusion of GPT-generated data affects the model’s performance on three tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC prediction, and property prediction (measured using BLEU, METEOR, and MAE, respectively). This allows researchers to understand the contribution of each component to the model’s overall effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation studies on training stage and GPT-generated instruction tuning data.

| Instructions | Details |

|---|---|

| You are an AI chemical assistant, and you are seeing a single molecule. What you see is provided with SMILES representation of the molecule and sentences describing the same molecule you are analyzing. Answer all questions as you are seeing the molecule. | |

| Ask diverse questions and give corresponding answers. | |

| Include questions asking about the detailed information of the molecule, including the class, conjugate acid/base, functional groups, chemical role, etc. | |

| Do not ask any question that cannot be answered confidently. | |

| Molecule SMILES: {SMILES} | |

| Caption: {CAPTION} | |

| Conversation: |

🔼 This table compares the performance of models trained using different methods: without instruction tuning (only Stage 1 pre-training), multi-task learning, and the proposed instruction tuning approach (ours). The performance is evaluated across three tasks: molecule description generation, IUPAC prediction, and property prediction (using Mean Absolute Error). This allows for a direct comparison of the effectiveness of different training strategies on various downstream tasks.

read the caption

Table 6: Performance comparison according to the training type.

| Instruction | Detail |

|---|---|

| You are an AI chemical assistant, and you are seeing a single molecule. What you see is provided with SMILES representation of the molecule and sentences describing the same molecule you are analyzing. In addition, the IUPAC name of the molecule is given. Answer all questions as you are seeing the molecule. | |

| Ask diverse questions and give corresponding answers. | |

| Include questions asking about the detailed information of the molecule, including the class, conjugate acid/base, functional groups, chemical role, etc. | |

| Do not ask any questions that cannot be answered confidently. | |

| Molecule SMILES: {SMILES} | |

| Caption: {CAPTION} | |

| IUPAC: {IUPAC} | |

| Conversation: |

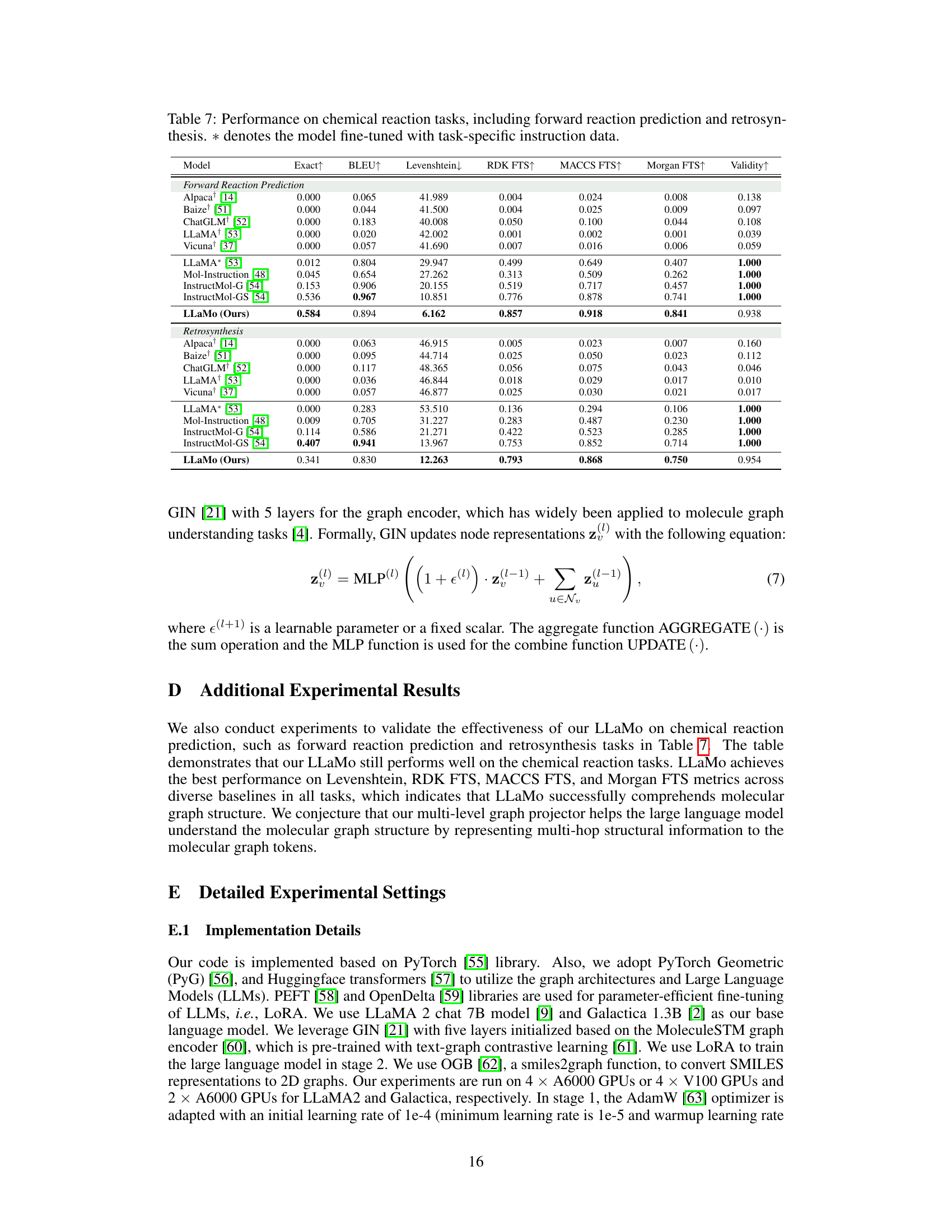

🔼 Table 7 presents the performance comparison of various models on two chemical reaction prediction tasks: forward reaction prediction and retrosynthesis. The table shows the performance metrics (Exact, BLEU, Levenshtein, RDK FTS, MACCS FTS, Morgan FTS, and Validity) for different models on these tasks. The models include various baselines (Alpaca, Baize, ChatGLM+, LLaMA+, Vicuna) and instruction-tuned models (LLaMA*, Mol-Instruction, InstructMol-G, InstructMol-GS). The asterisk (*) indicates that the model was fine-tuned using task-specific instruction data. This allows for a direct comparison of models trained with and without task-specific instruction tuning, showcasing the effects of this training method on performance.

read the caption

Table 7: Performance on chemical reaction tasks, including forward reaction prediction and retrosynthesis. ∗*∗ denotes the model fine-tuned with task-specific instruction data.

Full paper#