↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Training and evaluating large-scale Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models for LLMs is expensive and challenging, hindering research progress. Existing toolkits are either outdated or lack comprehensive evaluation capabilities. This paper introduces LibMoE, a new open-source library designed to overcome these limitations.

LibMoE offers a modular and efficient framework for training and evaluating various MoE algorithms. It standardizes training and evaluation pipelines, supports distributed training, and includes a comprehensive benchmark suite. The results show that despite unique characteristics, MoE algorithms have similar performance on average. LibMoE empowers researchers to easily explore different configurations and conduct meaningful comparisons, fostering progress in MoE research for LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models due to its release of LibMoE, a comprehensive and user-friendly benchmarking library. LibMoE lowers the barrier to entry for MoE research by providing standardized training and evaluation pipelines, making large-scale MoE studies more accessible. The results challenge existing assumptions about MoE algorithm performance and provide insights into expert selection dynamics, opening up new research avenues.

Visual Insights#

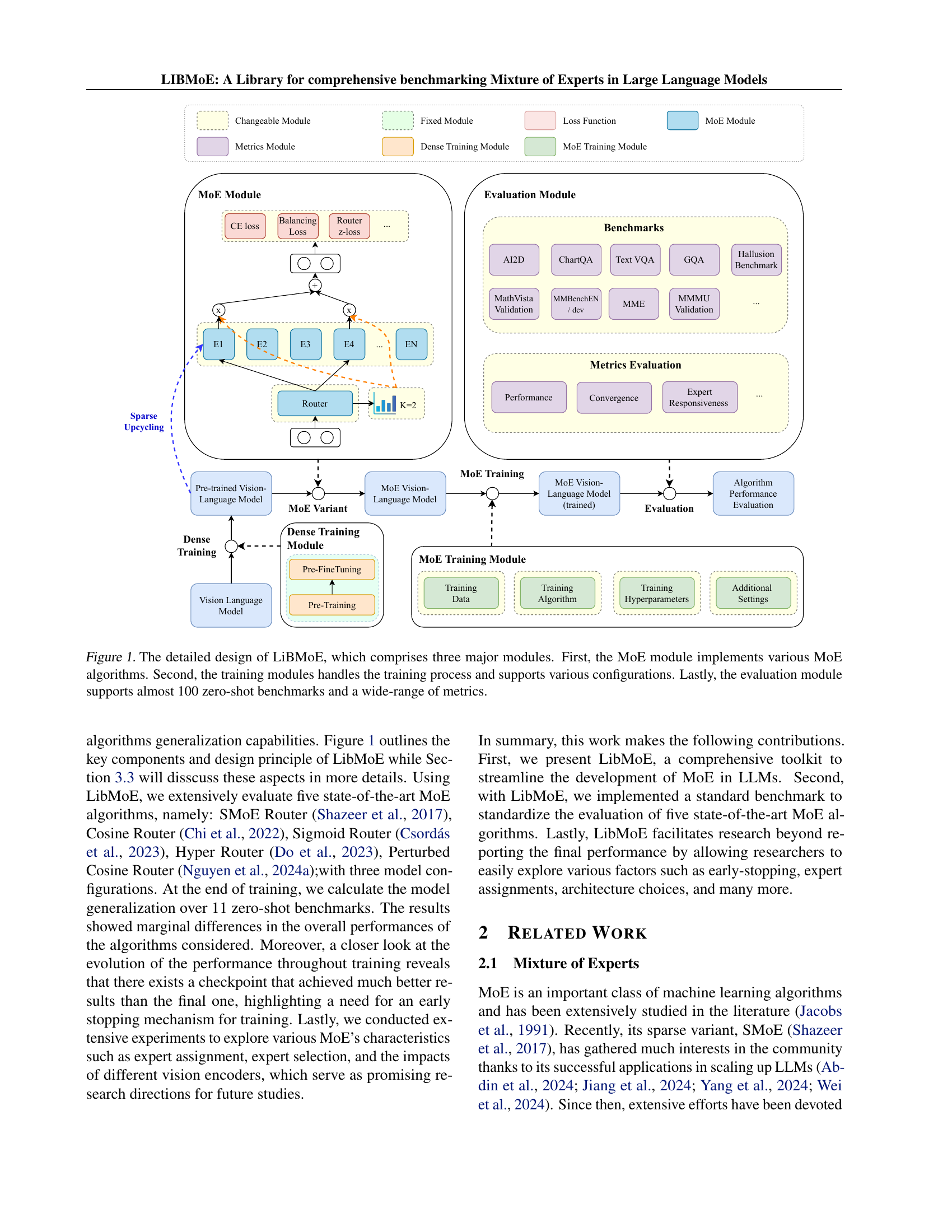

🔼 LibMoE’s architecture is composed of three core modules: the MoE module, responsible for implementing diverse MoE algorithms; the training module, which manages the training process and allows for various configurations; and the evaluation module, which supports a comprehensive set of nearly 100 zero-shot benchmarks and a wide array of metrics for thorough evaluation.

read the caption

Figure 1: The detailed design of LiBMoE, which comprises three major modules. First, the MoE module implements various MoE algorithms. Second, the training modules handles the training process and supports various configurations. Lastly, the evaluation module supports almost 100 zero-shot benchmarks and a wide-range of metrics.

| Stage | Image Tokens | Text Tokens | Total Tokens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Training | 3.21e8 | 1.52e7 | 3.37e8 |

| Pre-FineTuning | 4.08e8 | 1.59e8 | 5.67e8 |

| VIT (332K) | 1.80e8 | 7.71e7 | 2.57e8 |

| VIT (665K) | 3.60e8 | 1.54e8 | 5.14e8 |

🔼 This table shows the number of tokens (units of text data) used in each stage of the model training process. The stages are: pre-training, pre-fine-tuning, and visual instruction tuning (VIT). For the VIT stage, two different sizes of datasets are used, one with 332,000 images and another with 665,000 images. The total number of tokens in each stage represents the overall amount of training data utilized. The table is useful for understanding the scale of the dataset and how it changed throughout different training phases.

read the caption

Table 1: Token distribution across different stages. VIT denotes Visual Instruction Tuning, with 332K and 665K indicating the number of images used.

In-depth insights#

MoE Benchmarking#

The paper introduces LibMoE, a library for comprehensive benchmarking of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) in large language models (LLMs). LibMoE’s modular design facilitates efficient training and evaluation, addressing the resource constraints often hindering MoE research. The benchmarking process involves five state-of-the-art MoE algorithms across three different LLMs and eleven datasets, all under zero-shot conditions. Results reveal that despite algorithm differences, performance is roughly similar across a wide range of tasks when averaged, highlighting the need for further investigation into individual algorithm strengths and weaknesses across specific tasks. LibMoE standardizes evaluation pipelines, enabling researchers to focus on algorithmic innovation rather than infrastructure challenges, and promotes a deeper understanding of MoE behavior through extensive experimental evaluations and analysis of expert selection patterns and performance across multiple layers.

LibMoE Framework#

The LibMoE framework is a modular and comprehensive library designed to streamline research on Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models within Large Language Models (LLMs). Its core principles are modular design, enabling easy customization and extension; efficient training, leveraging sparse upcycling to reduce computational costs; and thorough evaluation, utilizing a standard benchmark across numerous zero-shot tasks. LibMoE addresses the accessibility challenges inherent in MoE research by providing a user-friendly toolkit that supports distributed training, various MoE algorithms, and extensive evaluation metrics. This allows researchers, regardless of computational resources, to perform meaningful experiments and contribute to the advancement of MoE techniques in LLMs. The framework’s flexibility facilitates explorations of numerous aspects such as sparsity, expert-router interactions, and loss functions, fostering broader investigation and a deeper understanding of MoE behavior.

MoE Algorithm Study#

The MoE Algorithm Study section delves into a comprehensive evaluation of five state-of-the-art MoE algorithms across three LLMs and eleven datasets. Modular design and standardized evaluation pipelines are key features. Results reveal that despite unique characteristics, algorithms exhibit similar average performance across various tasks. The study highlights the importance of early stopping mechanisms for improved results and identifies promising research directions by exploring expert assignment, selection, and the impact of various vision encoders. LibMoE’s modular design allows researchers to easily customize algorithms and facilitates deeper investigation into various factors beyond final performance metrics.

Expert Selection#

The research explores expert selection within Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models, examining its dynamics across various algorithms and datasets. Early training stages show significant fluctuations in expert allocation, gradually stabilizing as more data is processed. The Perturbed Cosine Router demonstrates faster convergence, achieving stable expert assignments earlier than others. Interestingly, the final training checkpoints don’t always yield the best performance, suggesting the potential benefits of early stopping. Analyzing expert selection across different subtasks reveals varied specialization patterns: simpler tasks show higher confidence in expert selection (lower entropy), while complex tasks exhibit broader distributions (higher entropy). The Cosine Router and Perturbed Cosine Router maintain consistent, low entropy values across subtasks, indicating strong specialization. Conversely, the SMOE and Hyper Routers display more variability, potentially impacting overall performance due to over-reliance on specific experts. The study underscores the importance of understanding expert selection mechanisms to enhance MoE model effectiveness. Furthermore, architecture choices, specifically the vision encoder, also influence expert selection patterns, highlighting the need to consider diverse factors for optimal performance.

Future Directions#

The provided text does not contain a section or heading specifically titled ‘Future Directions’. Therefore, it’s impossible to provide a summary of such a section. To generate the desired summary, please provide the relevant text from the research paper’s ‘Future Directions’ section.

More visual insights#

More on figures

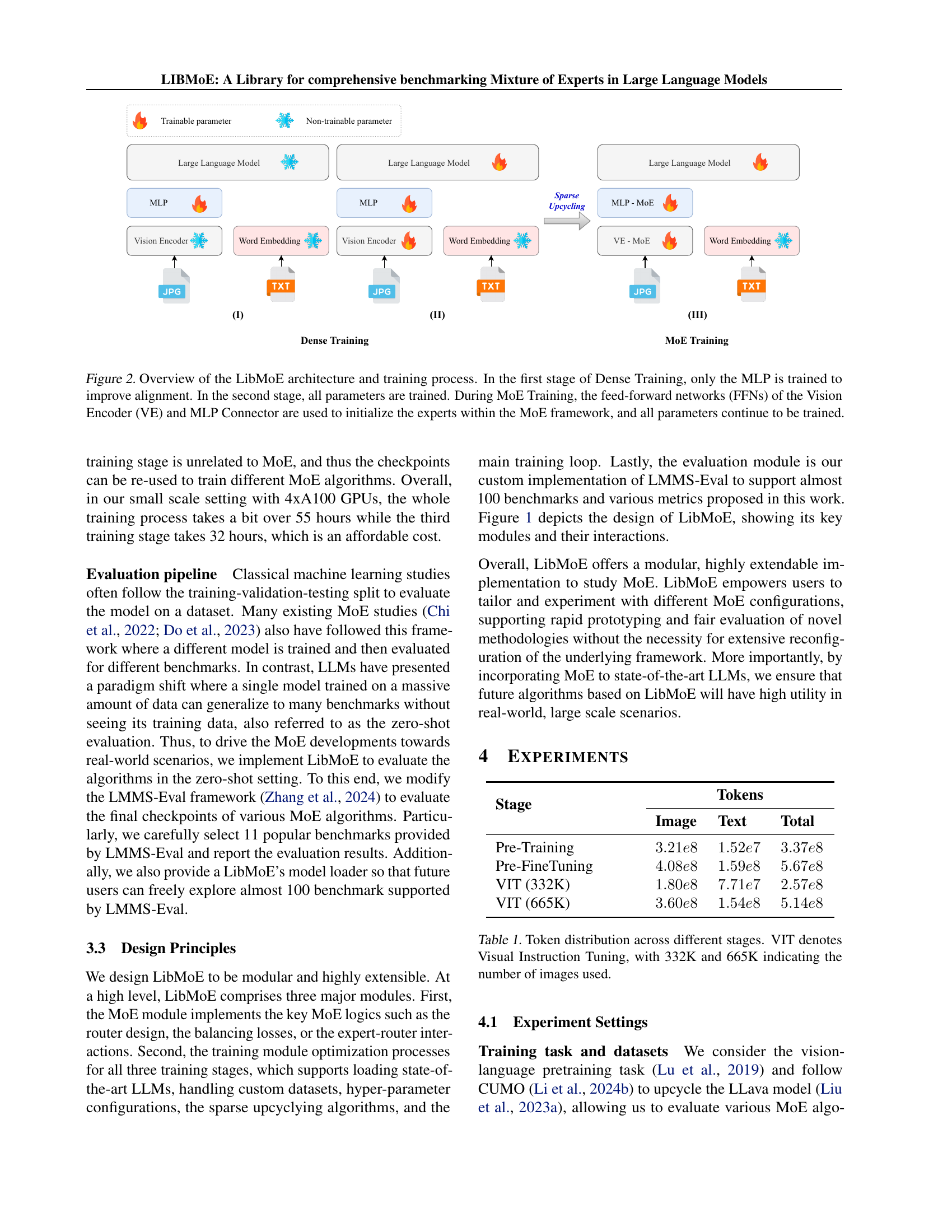

🔼 This figure details LibMoE’s training pipeline which consists of three stages: Dense Training, Pre-Fine Tuning, and MoE Training. In the first stage (Dense Training), only the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is trained to align the vision encoder and language model. The second stage (Pre-Fine Tuning) trains all model parameters. Finally, the third stage (MoE Training) uses the pre-trained weights from the previous stages to initialize the experts within the Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) framework, followed by training all parameters of the MoE model.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of the LibMoE architecture and training process. In the first stage of Dense Training, only the MLP is trained to improve alignment. In the second stage, all parameters are trained. During MoE Training, the feed-forward networks (FFNs) of the Vision Encoder (VE) and MLP Connector are used to initialize the experts within the MoE framework, and all parameters continue to be trained.

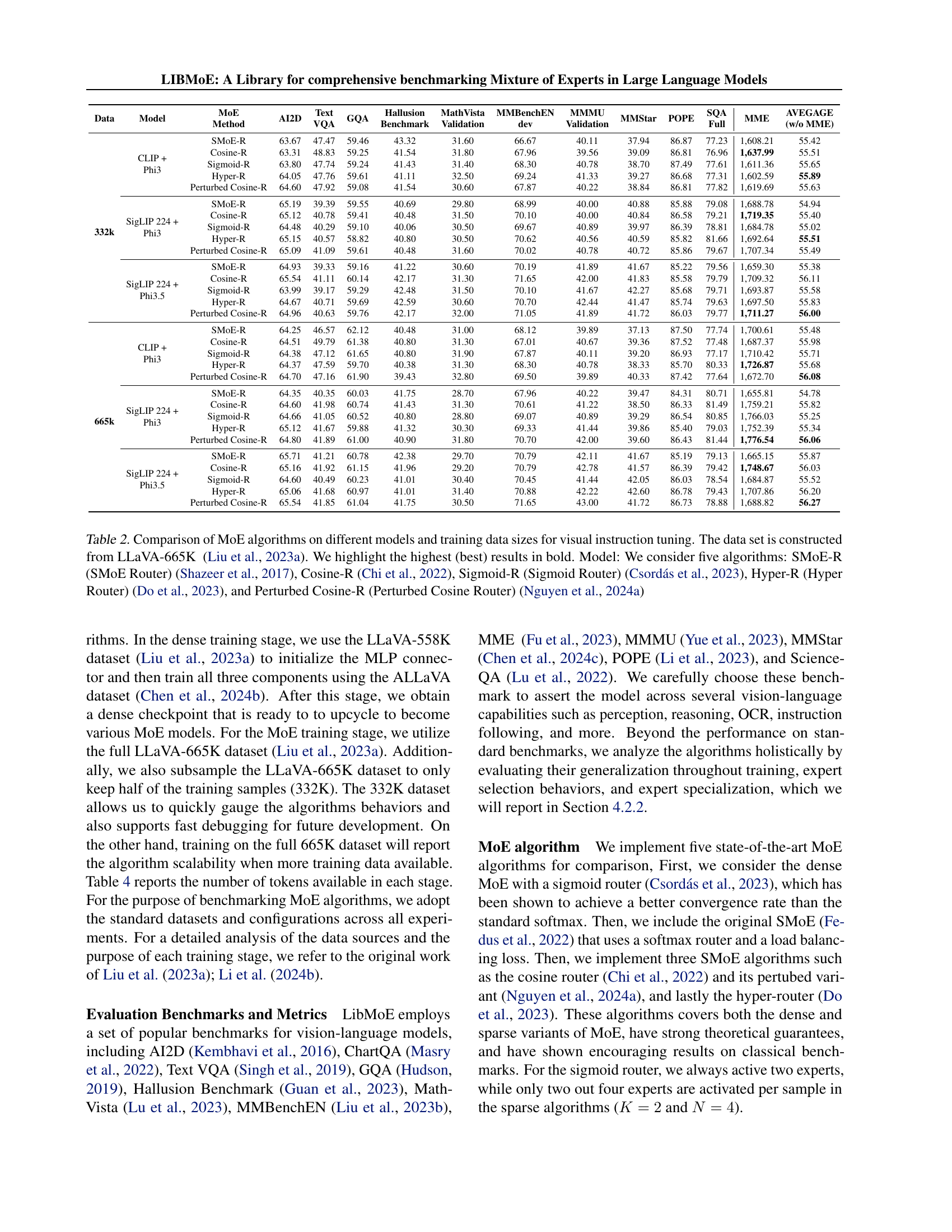

🔼 This figure shows the performance of five different Mixture of Experts (MoE) algorithms over the course of training. The training was done on the LLaVa-332K dataset, using a model that combines CLIP and Phi3. The graph displays the performance metrics for each algorithm at different training times, allowing for a comparison of their convergence rates and overall effectiveness. The x-axis represents the training time (or number of tokens), and the y-axis represents the performance. This allows readers to see how the performance of different MoE algorithms changes during training, giving insight into their strengths and weaknesses.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of the performance of different MoE algorithms over time. The experiments are conducted on the LLaVa-332K dataset and the CLIP + Phi3 model.

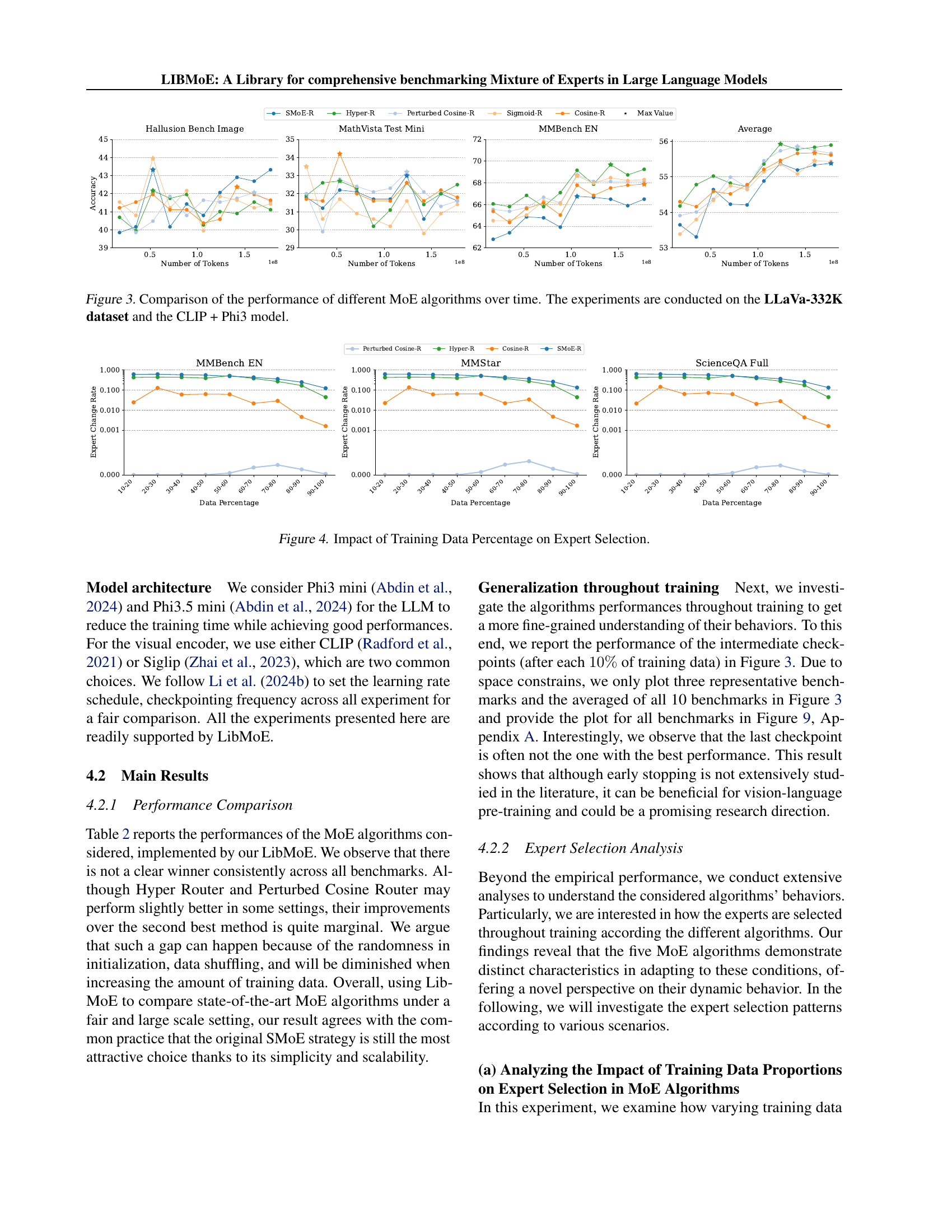

🔼 This figure analyzes how the percentage of training data used affects expert selection in Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models. It shows the rate of change in expert selection across different training data sizes for three specific benchmarks (MMBench EN, MMStar, and ScienceQA Full). The x-axis represents the data percentage used for training (10-20%, 20-30%, etc.), and the y-axis shows the rate of change in expert selection. The plot illustrates how the fluctuation in expert allocation decreases as more data is used, indicating that MoE algorithms stabilize expert assignment more effectively with larger datasets.

read the caption

Figure 4: Impact of Training Data Percentage on Expert Selection.

🔼 Figure 5 presents an analysis of how frequently different experts are selected for various subtasks within different Mixture of Experts (MoE) algorithms. The entropy values, displayed for each algorithm and subtask, quantify the diversity of expert selection. Lower entropy indicates that a smaller subset of experts are repeatedly chosen for a given subtask, suggesting specialization; while higher entropy means a more even distribution of expert usage, suggesting a more generalized approach. This visualization helps understand the extent to which each algorithm exhibits expert specialization for various subtasks.

read the caption

Figure 5: Entropy analysis of expert selection frequency across subtasks in MoE algorithms. The entropy values indicate the tendency of different routers to consistently select specific experts for given subtasks.

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comparison of the confidence levels exhibited by five different Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) routing algorithms across various tasks. Confidence is measured using entropy, calculated for each individual sample within each task and then averaged across all samples in that task. This provides a measure of how decisively the algorithms select experts. Because the entropy values for the Cosine Router and Perturbed Cosine Router algorithms were very close, the x-axis values for these two algorithms have been scaled by a factor of 10000 for better visualization of subtle differences. This scaling is done using the formula (entropy -1.999) * 10000. The figure allows for easy comparison of algorithm confidence across different task types (OCR, Coarse-grained, Fine-grained, and Reasoning).

read the caption

Figure 6: Measured confidence levels of various MoE algorithms across tasks. Entropy was computed for each sample and then averaged within each task to illustrate differences in confidence across MoE algorithms. For the Cosine-R and Perturbed Cosine-R algorithms, values on the x-axis (denoted by ∗) were scaled to enhance visualization of subtle entropy variations. The scaled entropy values are calculated using the transformation (entropy−1.999)×10000entropy1.99910000(\text{entropy}-1.999)\times 10000( entropy - 1.999 ) × 10000.

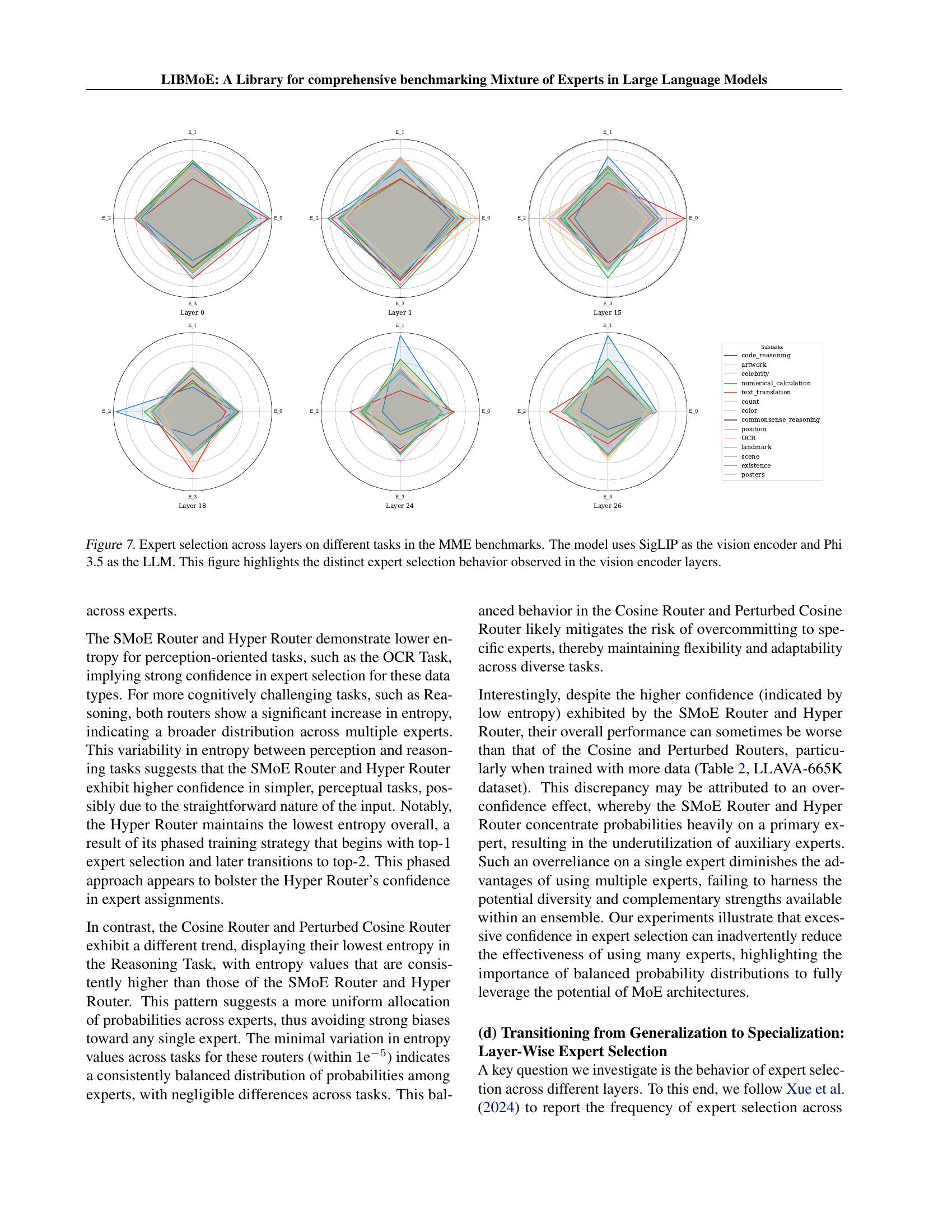

🔼 This figure visualizes expert selection patterns across various layers of a vision encoder within a Mixture of Experts (MoE) model, focusing on distinct tasks within the MME benchmark. The model uses SigLIP as its vision encoder and Phi 3.5 as its language model. The plot reveals how the frequency of each expert being chosen varies across different layers and tasks, showcasing the dynamic specialization of experts during the processing of visual information. Early layers exhibit less specialization while deeper layers show a stronger tendency towards task-specific expert utilization.

read the caption

Figure 7: Expert selection across layers on different tasks in the MME benchmarks. The model uses SigLIP as the vision encoder and Phi 3.5 as the LLM. This figure highlights the distinct expert selection behavior observed in the vision encoder layers.

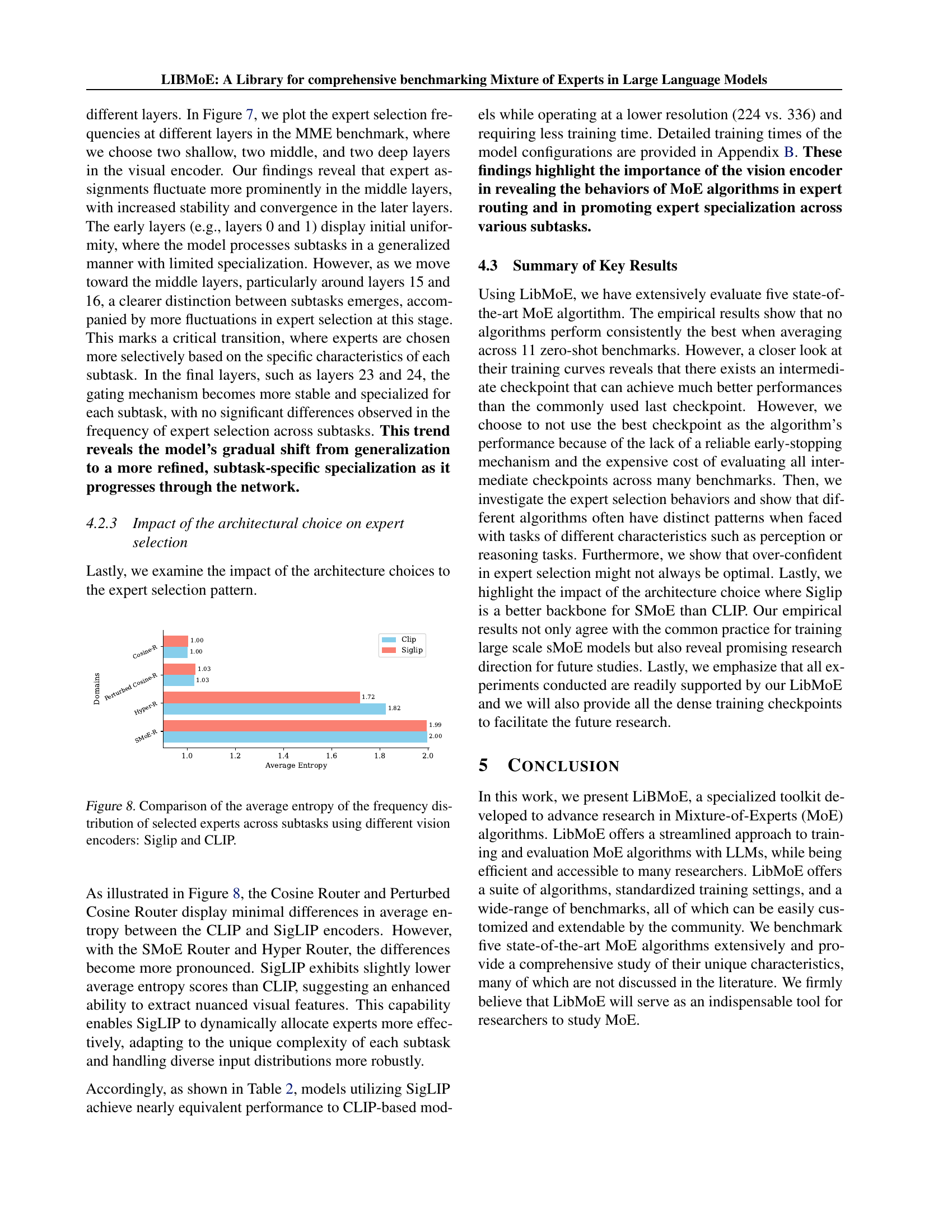

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of the average entropy calculated from the frequency distribution of selected experts across various subtasks. Two different vision encoders, SigLIP and CLIP, were used in the models. The chart allows for a comparison of expert selection behavior between the two encoders, showing whether they demonstrate consistent or varying selections of experts across multiple subtasks. Differences in entropy values might suggest that one encoder leads to greater expert specialization or more balanced utilization across subtasks. This visualization helps in understanding the impact of the choice of vision encoder on the MoE algorithm’s performance and expert selection patterns.

read the caption

Figure 8: Comparison of the average entropy of the frequency distribution of selected experts across subtasks using different vision encoders: Siglip and CLIP.

🔼 This figure displays the performance of five different Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) algorithms across eleven benchmarks over the course of training. The training data used was the LLaVa-332K dataset, and the model employed was CLIP + Phi3. The graph allows for a visual comparison of how the performance of each algorithm changes over time on various tasks, highlighting the relative strengths and weaknesses of different routing strategies within the MoE framework.

read the caption

Figure 9: Comparison of the performance of different MoE algorithms across 11 benchmarks over time. The experiments were conducted using the LLaVa-332K dataset and the CLIP + Phi3 model.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive comparison of five different Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) algorithms across three different large language models (LLMs) and various training data sizes. The algorithms compared include SMoE Router, Cosine Router, Sigmoid Router, Hyper Router, and Perturbed Cosine Router. Each algorithm’s performance is evaluated on 11 different zero-shot benchmarks for visual instruction tuning using the LLaVA-665K dataset. The best performance for each benchmark and LLM is highlighted in bold, allowing for easy identification of top-performing algorithms under different conditions.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of MoE algorithms on different models and training data sizes for visual instruction tuning. The data set is constructed from LLaVA-665K Liu et al. (2023a). We highlight the highest (best) results in bold. Model: We consider five algorithms: SMoE-R (SMoE Router) Shazeer et al. (2017), Cosine-R Chi et al. (2022), Sigmoid-R (Sigmoid Router) Csordás et al. (2023), Hyper-R (Hyper Router) Do et al. (2023), and Perturbed Cosine-R (Perturbed Cosine Router) Nguyen et al. (2024a)

| MoE | |

|---|---|

| Method |

🔼 This table details the computational resources and time required to train various Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) algorithms using LibMoE. It breaks down the training time into three stages: pre-training, pre-fine-tuning, and visual instruction tuning. Different model configurations (CLIP + Phi3, SigLip 224 + Phi3, SigLip 224 + Phi3.5) and dataset sizes (332K and 665K samples) are considered, along with five distinct MoE algorithms (SMOE-R, Cosine-R, Sigmoid-R, Hyper-R, and Perturbed Cosine-R). The number of GPUs used is also specified for each training scenario.

read the caption

Table 3: Detailed Training Duration and Resource Utilization for MoE Algorithms Across Models and Datasets

Full paper#