↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current methods for aligning Large Language Models (LLMs) with human preferences are often sample-inefficient, requiring vast amounts of human feedback, a significant bottleneck. This paper addresses this issue by framing LLM alignment as a contextual dueling bandit problem.

The authors introduce SEA (Sample-Efficient Alignment), a unified algorithm based on Thompson sampling designed for online LLM alignment. SEA incorporates active exploration strategies that strategically select the data to collect, leading to improved sample efficiency. Experiments show that SEA significantly outperforms existing active exploration methods, demonstrating its high sample-efficiency and effectiveness across different model scales and preference learning algorithms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on LLM alignment because it introduces SEA, a sample-efficient algorithm that significantly improves upon existing methods. This offers a practical and scalable solution to the challenge of aligning LLMs with human preferences using limited feedback, which is a major bottleneck in the field. Its open-source codebase also makes it easy for others to build upon this work and accelerate future research.

Visual Insights#

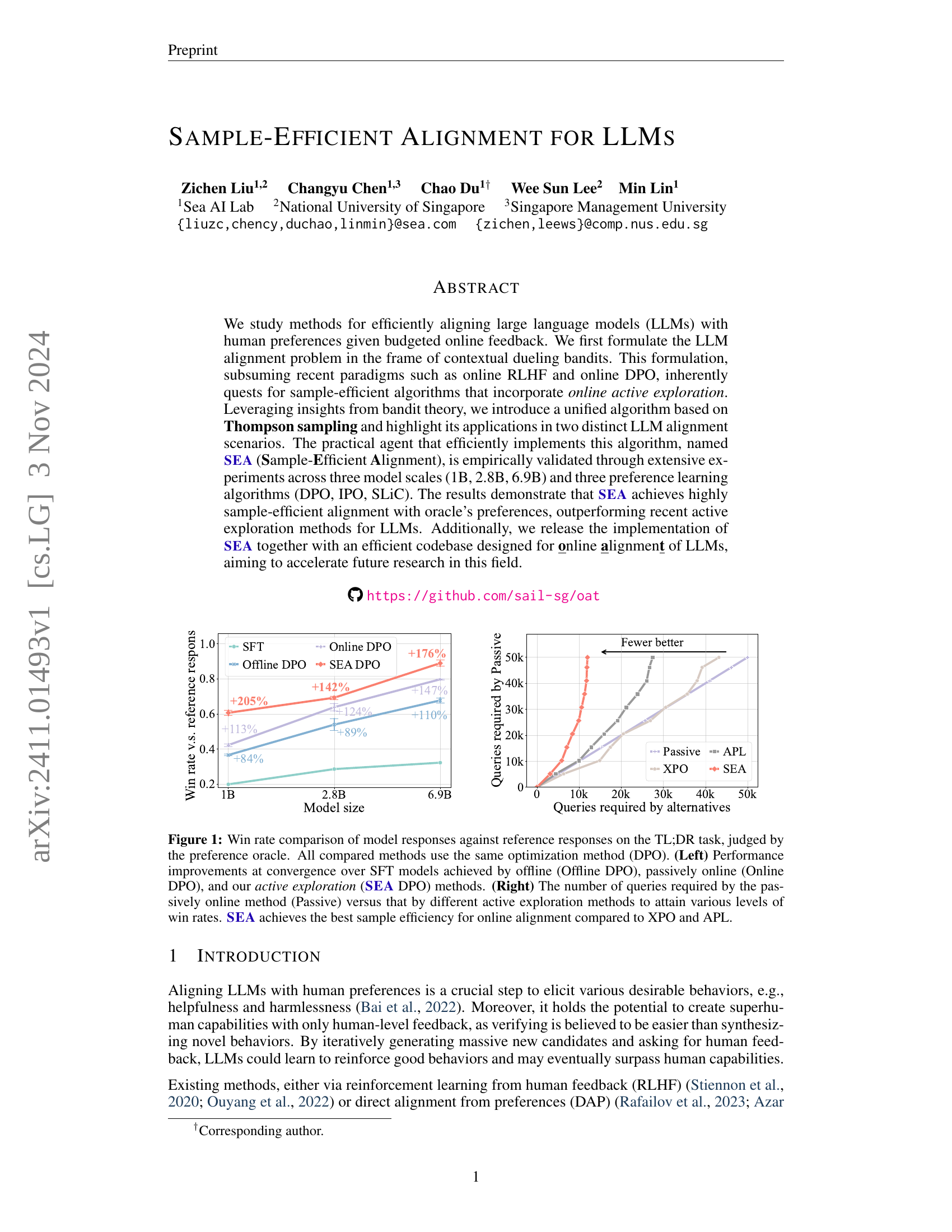

🔼 Figure 1 presents a comparison of Large Language Model (LLM) response quality using different training methods. The task is TL;DR summarization, and success is judged by comparing the model’s output to a reference summary. The left panel shows the performance improvement achieved by three methods compared to a baseline (Supervised Fine-Tuning, or SFT). ‘Offline DPO’ represents a method that trains entirely on a fixed dataset, while ‘Online DPO’ updates continuously but passively incorporates new data. ‘SEA DPO’ incorporates active exploration, strategically selecting data that improves performance the most efficiently. The results demonstrate that SEA DPO significantly outperforms both Offline and Online DPO. The right panel shows the sample efficiency of the different methods. Sample efficiency refers to the number of queries required to achieve a given level of performance. This panel demonstrates SEA’s superior sample efficiency, requiring fewer queries to achieve the same performance as other active methods, such as XPO and APL.

read the caption

Figure 1: Win rate comparison of model responses against reference responses on the TL;DR task, judged by the preference oracle. All compared methods use the same optimization method (DPO). (Left) Performance improvements at convergence over SFT models achieved by offline (Offline DPO), passively online (Online DPO), and our active exploration (SEA DPO) methods. (Right) The number of queries required by the passively online method (Passive) versus that by different active exploration methods to attain various levels of win rates. SEA achieves the best sample efficiency for online alignment compared to XPO and APL.

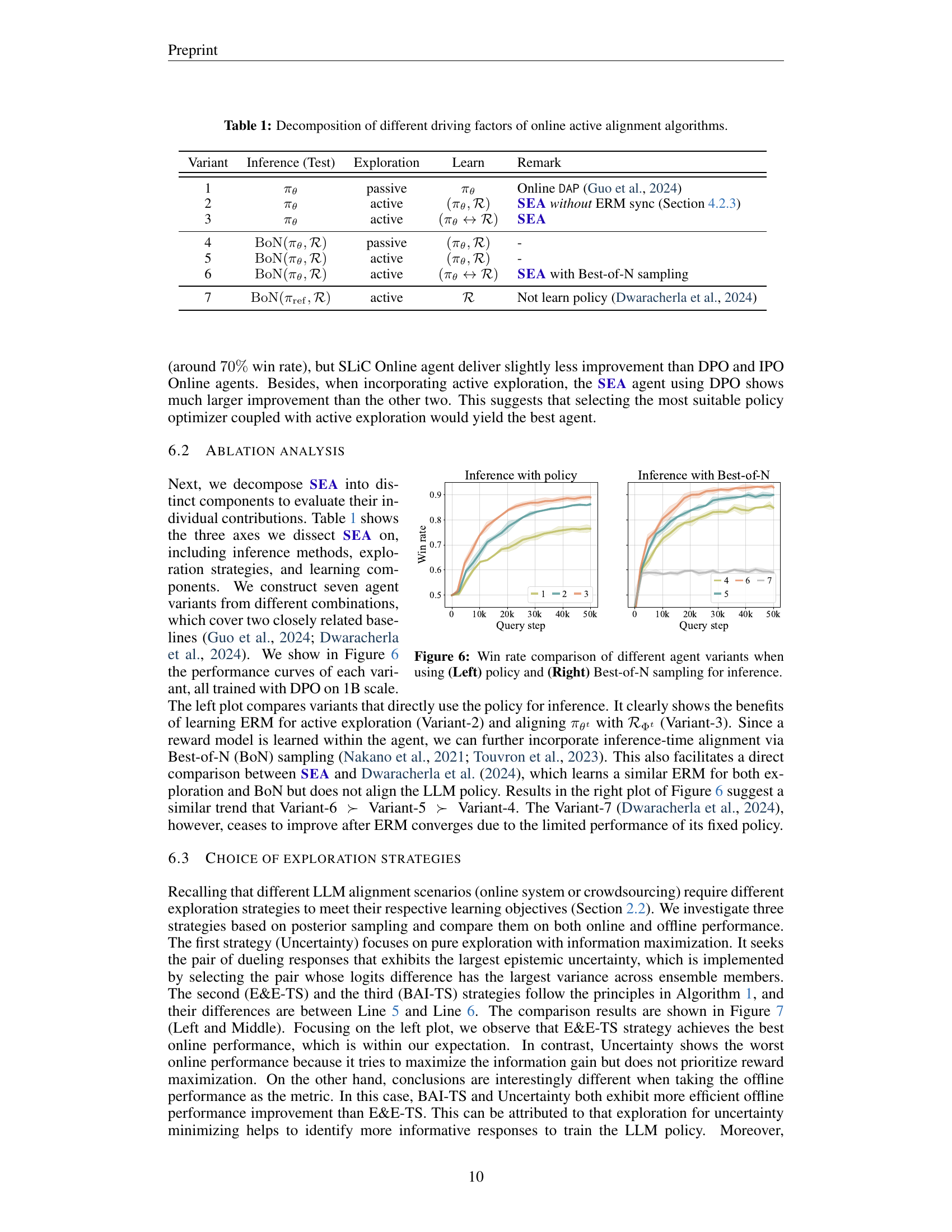

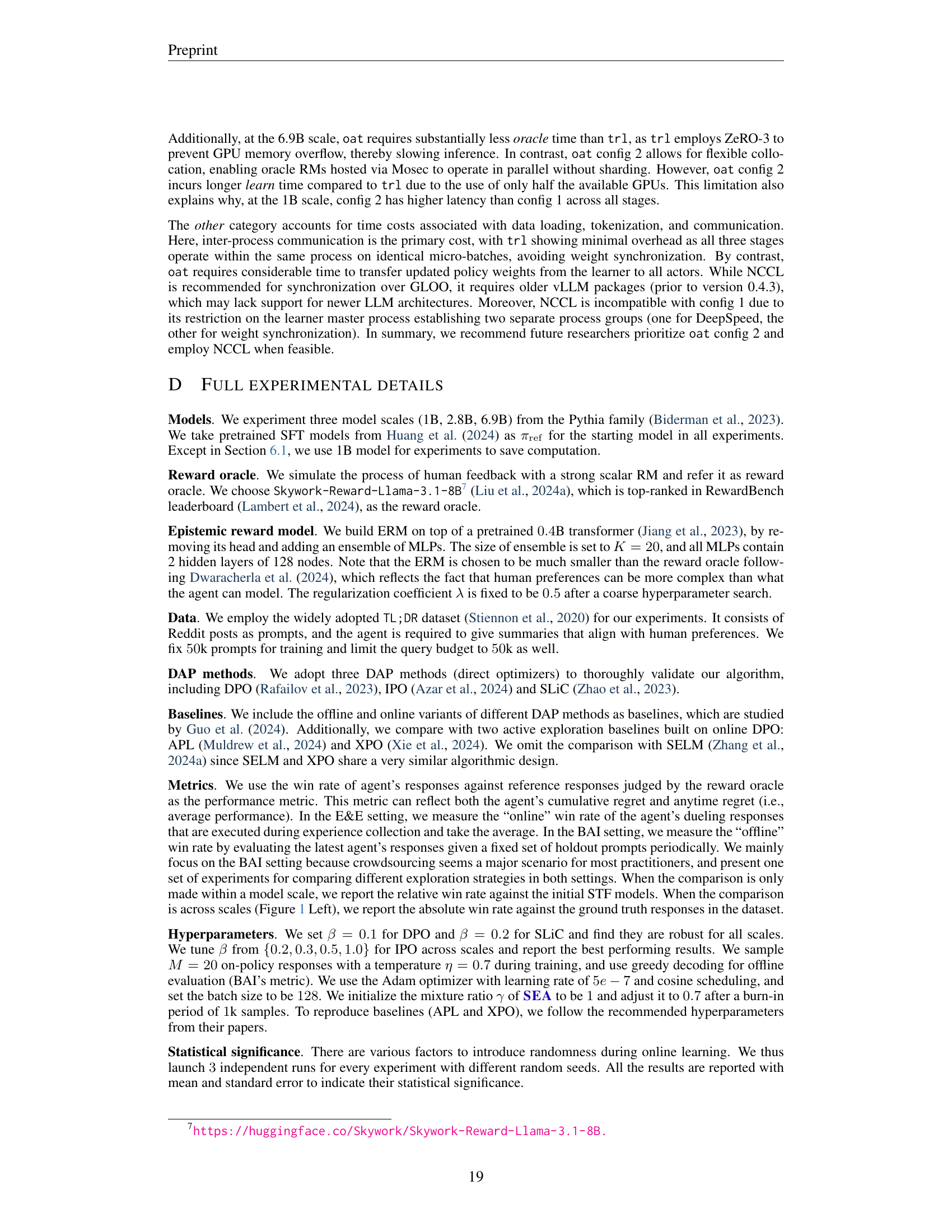

| Variant | Inference (Test) | Exploration | Learn | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | πθ | passive | πθ | Online DAP (Guo et al., 2024) |

| 2 | πθ | active | (πθ,ℛ) | SEA without ERM sync (Section 4.2.3) |

| 3 | πθ | active | (πθ↔ℛ) | SEA |

| 4 | BoN(πθ,ℛ) | passive | (πθ,ℛ) | - |

| 5 | BoN(πθ,ℛ) | active | (πθ,ℛ) | - |

| 6 | BoN(πθ,ℛ) | active | (πθ↔ℛ) | SEA with Best-of-N sampling |

| 7 | BoN(πref,ℛ) | active | ℛ | Not learn policy (Dwaracherla et al., 2024) |

🔼 This table breaks down the key components contributing to the effectiveness of different online active alignment algorithms. It analyzes three main factors: the method used for inference (testing), the type of exploration strategy employed, and the learning mechanism used. By varying these factors, the table demonstrates the individual and combined impact of each component on the overall performance of the algorithm. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of how different design choices affect the sample efficiency and alignment quality.

read the caption

Table 1: Decomposition of different driving factors of online active alignment algorithms.

In-depth insights#

Sample-Efficient Alignment#

Sample-efficient alignment in LLMs focuses on minimizing the human feedback required for effective model alignment. This is crucial because acquiring human feedback is often costly and time-consuming. The core idea revolves around designing algorithms that actively select the most informative data points to learn from, rather than passively using all available data. This involves strategies such as active exploration, where the model strategically chooses inputs that maximally reduce uncertainty about its alignment with human preferences. By intelligently focusing feedback efforts, sample-efficient alignment aims to achieve comparable performance with significantly less data compared to traditional methods, accelerating LLM development and deployment. Key techniques often involve advanced bandit algorithms, particularly Thompson Sampling, and carefully designed reward model formulations that balance exploration and exploitation. Ultimately, sample-efficient alignment addresses a critical bottleneck in current LLM development, paving the way for creating more aligned and capable models with improved resource efficiency.

Contextual Dueling Bandits#

The concept of “Contextual Dueling Bandits” offers a powerful framework for understanding and addressing the challenges of aligning large language models (LLMs) with human preferences. It elegantly frames the problem as a learning process where an agent (the LLM) iteratively interacts with an environment (human evaluators) to refine its policy. This interaction involves presenting pairs of LLM-generated responses for comparison, thus providing relative feedback rather than absolute scores. This relative feedback is crucial because it mirrors how humans often express preferences (e.g., choosing between options rather than quantifying their desirability on a scale). The framework’s strength lies in explicitly considering the context of each comparison, thereby allowing the agent to learn more nuanced and context-aware preferences. Context is vital as it helps to generalize the learned preferences beyond specific examples to a broader range of situations. The concept naturally lends itself to the incorporation of active exploration strategies, where the agent strategically selects the pairs to compare to maximize learning efficiency. This is in contrast to passive methods that might simply compare randomly selected pairs. By actively choosing the comparisons, the algorithm can focus on areas of high uncertainty or where more information is needed. Active exploration is vital because it significantly accelerates learning, reducing the number of human evaluations needed to achieve a satisfactory level of alignment. This makes the framework ideal for sample-efficient LLM alignment, a crucial goal considering the cost and limitations of human annotation.

Thompson Sampling#

Thompson Sampling is a powerful algorithm for online decision-making, particularly well-suited for problems with uncertain rewards. Its core strength lies in its ability to balance exploration and exploitation effectively. By maintaining a probability distribution over possible reward values, Thompson Sampling elegantly addresses the exploration-exploitation dilemma. The algorithm samples from this distribution to select actions, favoring options with higher expected reward but also incorporating uncertainty to guide exploration. This probabilistic approach naturally adapts to changing environments and often outperforms deterministic methods. In the context of LLM alignment, Thompson Sampling allows the algorithm to efficiently explore the space of possible LLM responses and learn user preferences with fewer interactions. This is particularly crucial given the high cost of human feedback. However, a key challenge lies in the scalability of Thompson Sampling, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional action spaces, such as those encountered when generating LLM responses. The paper successfully addresses this by incorporating techniques such as deep ensembles to efficiently estimate and sample from the reward distribution and policy-guided search to handle the large action space. The resulting Sample-Efficient Alignment (SEA) method combines the theoretical advantages of Thompson Sampling with efficient practical implementations, showing promising results in aligning LLMs with human preferences.

Online Exploration#

Online exploration in reinforcement learning (RL) and, more specifically, in the context of aligning large language models (LLMs), presents a crucial challenge. The core idea revolves around actively gathering information during the learning process to efficiently improve the agent’s (LLM’s) performance. This contrasts with passive exploration, where data is collected without strategic selection. Effective online exploration is critical for sample efficiency, minimizing the amount of human feedback required for LLM alignment. Methods such as Thompson Sampling, which balances exploration and exploitation by sampling from a posterior distribution of model parameters, prove useful. However, straightforward Thompson Sampling faces challenges in the high-dimensional space of LLMs. Therefore, practical techniques like deep ensembles to model uncertainty and efficient exploration strategies like policy-guided search are crucial for efficient online exploration. The choice of exploration strategy must also align with the learning objective, whether it’s continual improvement (explore-exploit setting) or finding the optimal solution efficiently (best-arm identification).

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize improving the sample efficiency of LLM alignment. More sophisticated exploration strategies, beyond those currently used, are needed to accelerate learning with limited human feedback. Developing robust and efficient methods for handling uncertainty in reward models is crucial, especially when dealing with the inherent stochasticity of human preferences. Addressing the computational cost of online alignment, particularly for large language models, is essential to make these techniques practical for real-world applications. Furthermore, investigations into alternative feedback mechanisms, beyond simple pairwise comparisons, could improve the quality and efficiency of the alignment process. A focus on creating generalizable alignment techniques that work across different model architectures and downstream tasks is also needed. Finally, exploration of new theoretical frameworks could help address the limitations of current approaches and pave the way for more effective and efficient LLM alignment.

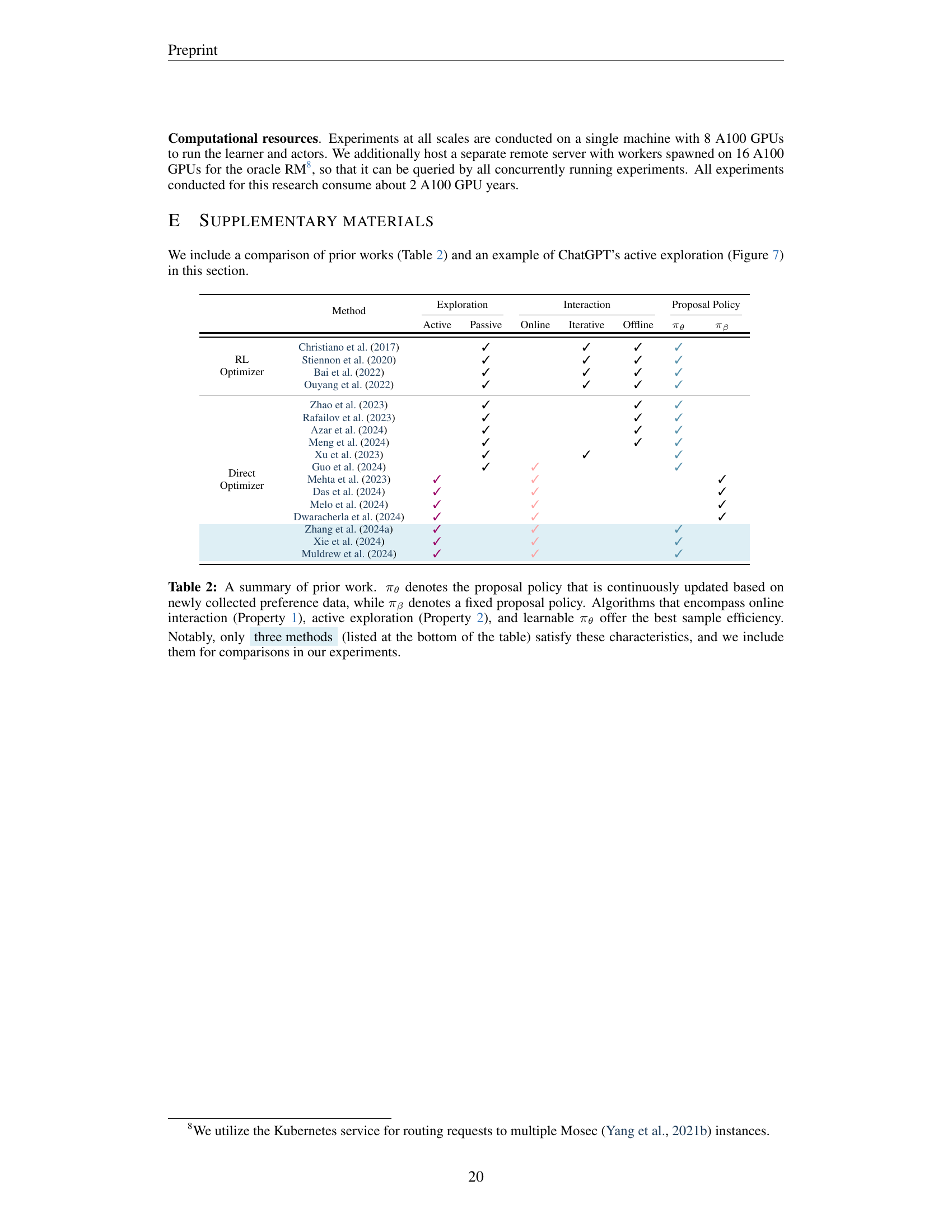

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure illustrates the analogous relationship between contextual dueling bandits (CDB) and LLM alignment. The CDB framework involves an agent interacting with an environment, receiving feedback (in the form of pairwise comparisons), and learning to select optimal actions. The LLM alignment interface mirrors this, with the LLM acting as the agent, humans providing preference feedback on generated text responses, and the LLM’s policy being updated to better align with human preferences. The diagram highlights the parallel structure of both problems, demonstrating how the theoretical framework of CDB can be applied to the practical problem of LLM alignment.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustrative comparison between CDB and LLM alignment.

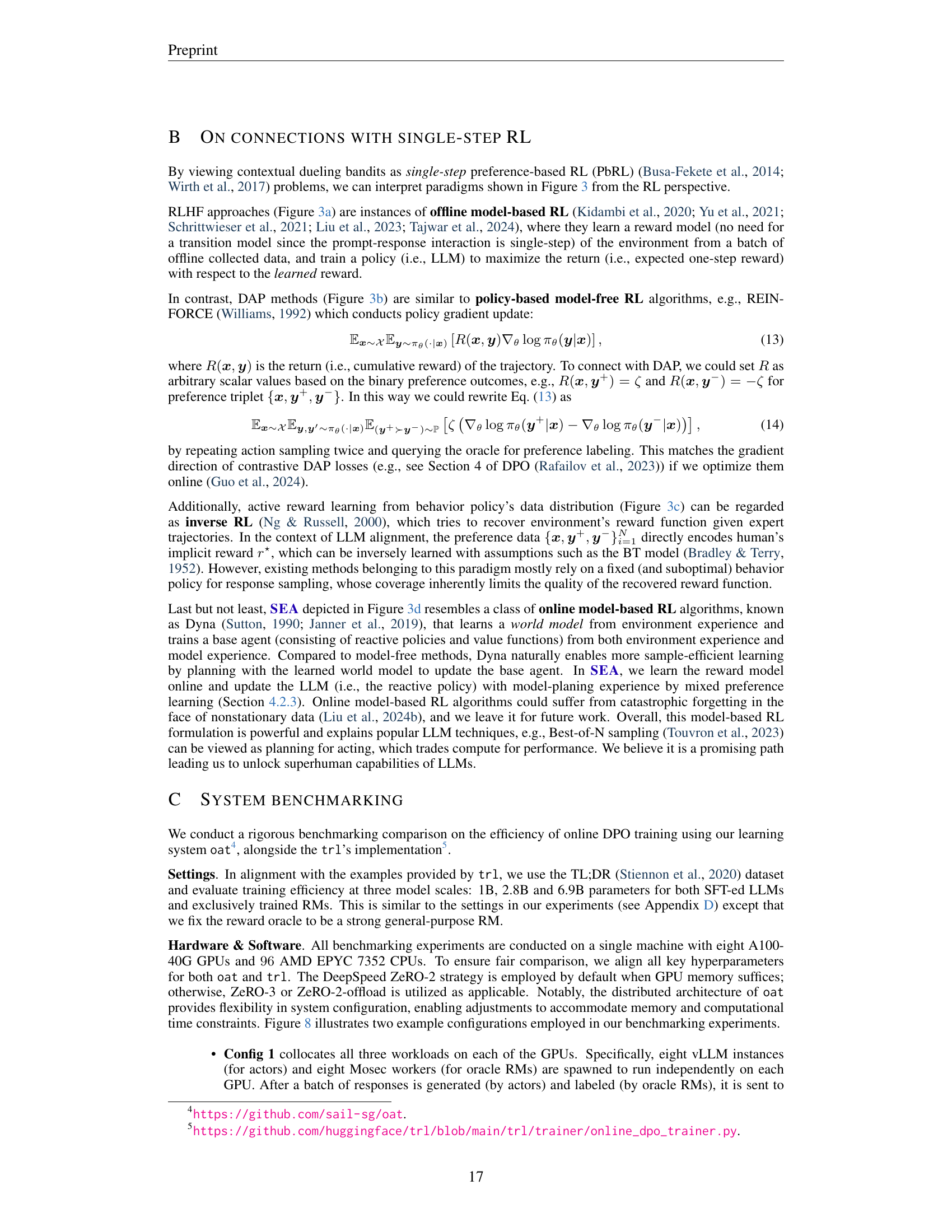

🔼 This figure illustrates four different approaches to aligning large language models (LLMs) with human preferences. The approaches are categorized within the Contextual Dueling Bandit (CDB) framework. Each approach is represented diagrammatically, showing the interaction between the LLM agent, the human, and the data flow. The key differences lie in how they collect and utilize feedback for learning. Some methods are purely offline or iterative (performing the interaction loop only a few times). Others operate fully online, learning continuously from new interactions. The figure highlights the different components of each approach: the learnable parameters (model weights), the optimization method (reinforcement learning or direct optimization), and whether active exploration is used to maximize learning efficiency. The color-coding aids in distinguishing these components. Specifically, $r_\phi$ represents a point estimate of the human’s implicit reward, while $\mathcal{R}_\Phi$ is an uncertainty-aware reward model.

read the caption

Figure 3: Different paradigms for solving the LLM alignment problem in the CDB framework. Note that although all paradigms follow the LLM alignment interface (Figure 2) with the interaction loop, some are actually offline or iteratively online (i.e., loop only once or a few times). Detailed comparisons will be made in Section 3. We use colors to denote learnable components, RL optimizer, direct optimizer, and active exploration. rϕsubscript𝑟italic-ϕr_{\phi}italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_ϕ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denotes a point estimate of human’s implicit reward, while ℛΦsubscriptℛΦ{\mathcal{R}}_{\Phi}caligraphic_R start_POSTSUBSCRIPT roman_Φ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT refers to an uncertainty-aware reward model.

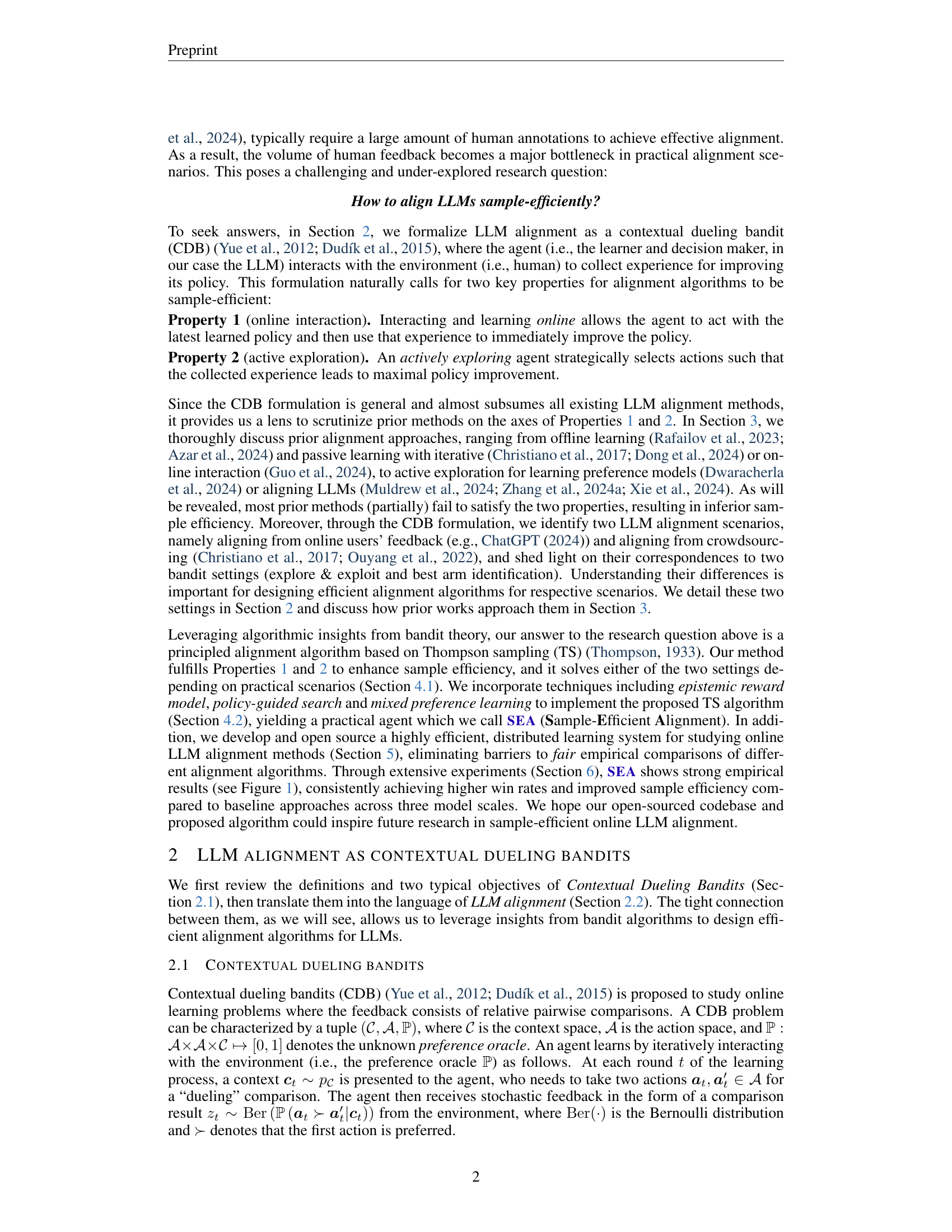

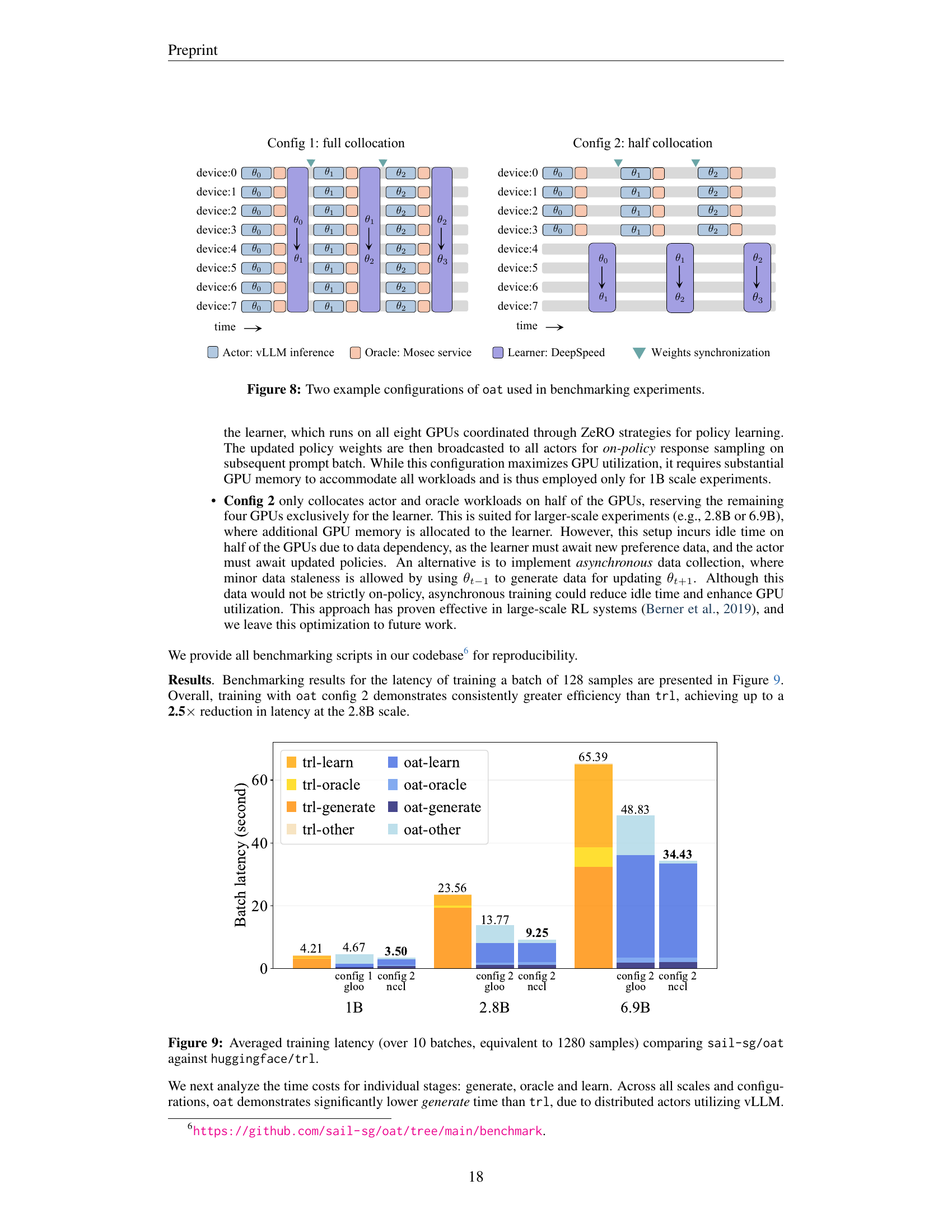

🔼 This figure illustrates the distributed learning system designed for online LLM alignment experiments. The system consists of three main components: Actors, Learner, and Oracle. Actors generate multiple LLM responses concurrently for a given prompt. The Learner updates the LLM parameters using feedback from the Oracle. The Oracle judges the quality of the LLM’s generated responses by comparing them against references and provides feedback to the Learner. This system is designed to accelerate online LLM alignment research by enabling efficient experimentation with various online alignment algorithms.

read the caption

Figure 4: The learning system for experimenting online LLM alignment algorithms.

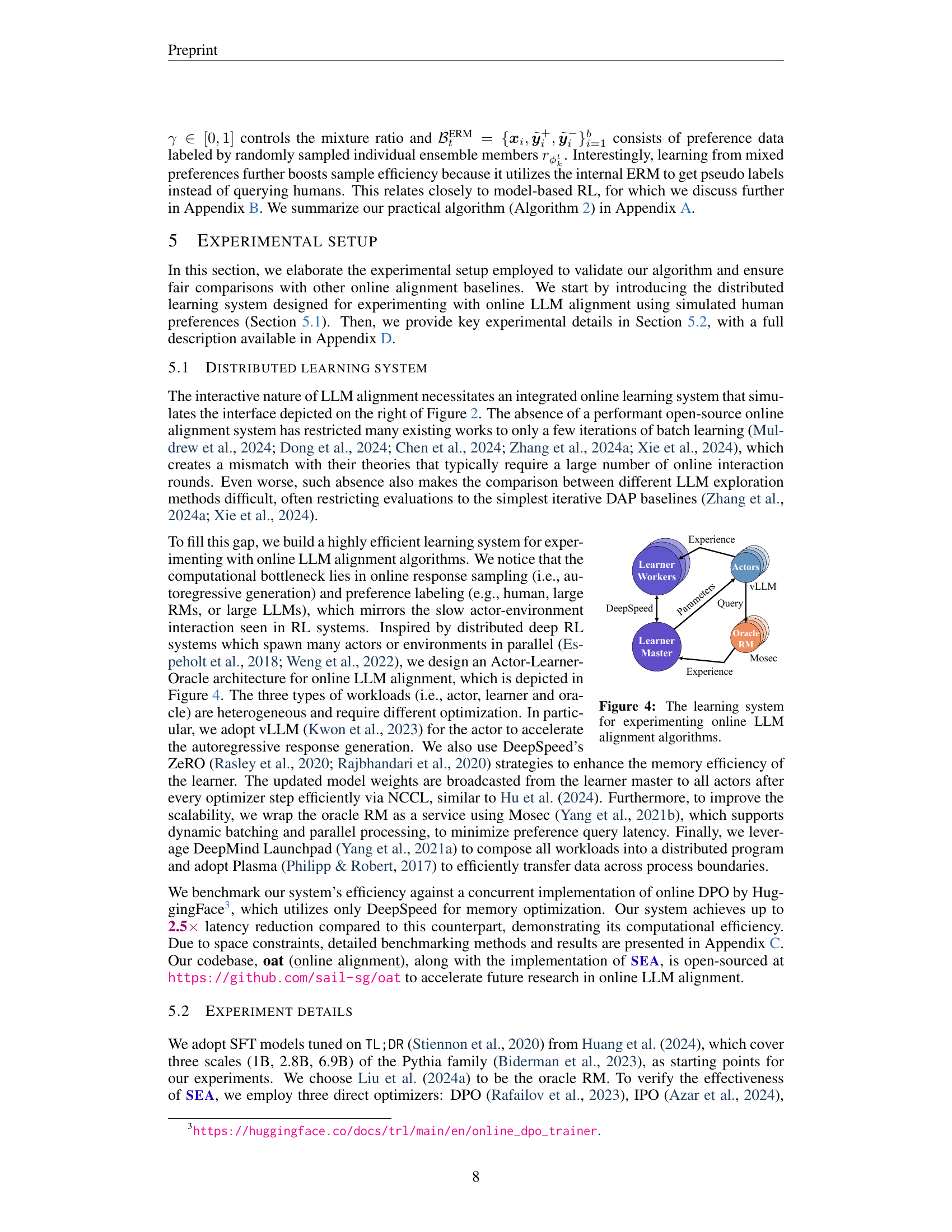

🔼 This figure displays the results of a comparative study evaluating various LLM alignment algorithms across different model sizes (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters) and three optimization methods (DPO, IPO, and SLiC). The win rate, representing the percentage of times the model’s response was preferred over its initial SFT (Supervised Fine-Tuning) version by a human oracle, is plotted against the number of queries made to the oracle. This illustrates the sample efficiency of each algorithm in achieving alignment with human preferences. The figure allows for a comparison of different methods’ performance, showing how quickly and effectively each achieves high win rates across varying model scales and optimization techniques.

read the caption

Figure 5: Win rate comparison of different algorithms against their initial SFT models across three scales and three direct optimizers.

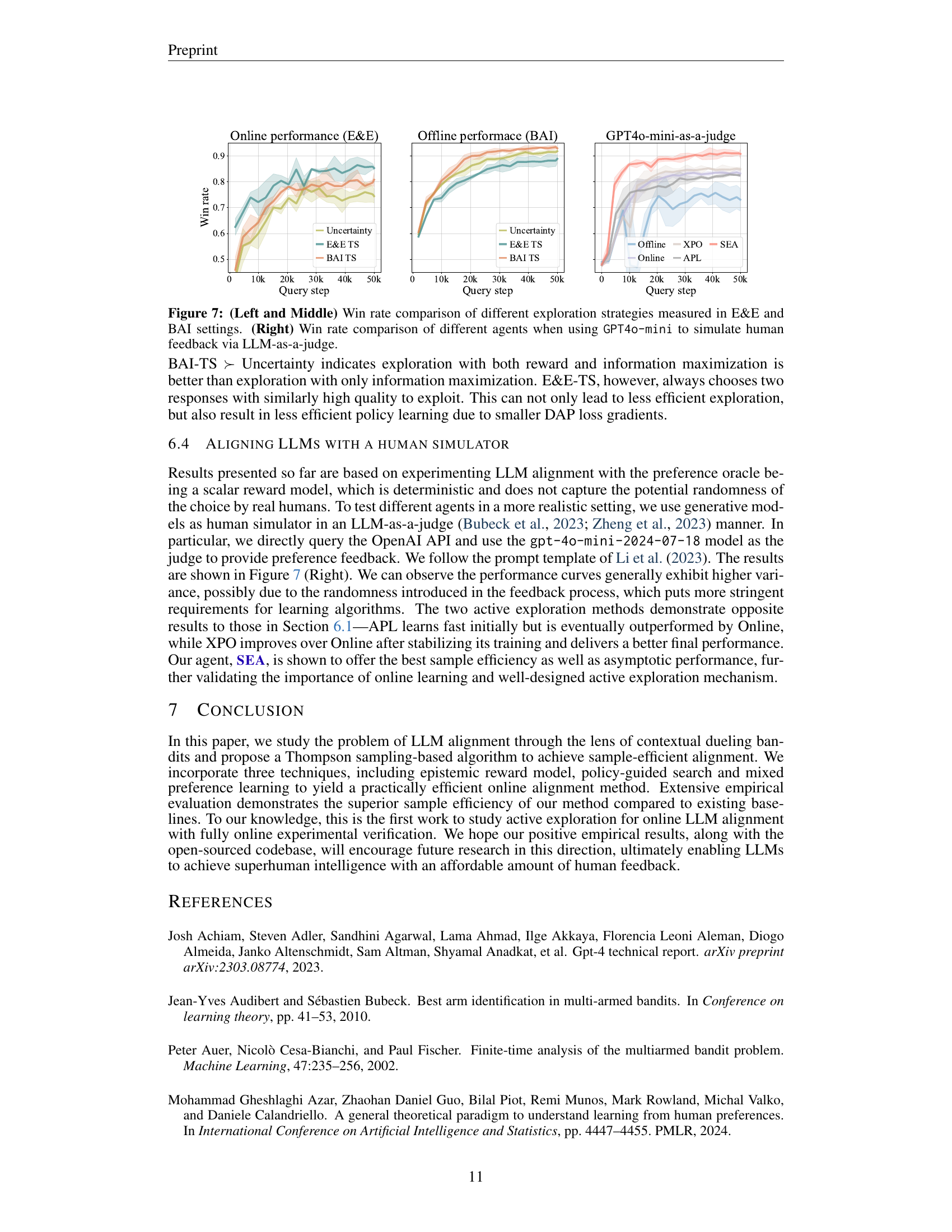

🔼 This figure displays the win rates of different agent variants across various query steps. The left panel showcases results when the agent utilizes its learned policy for inference, directly using the policy output to select responses. The right panel demonstrates the results when using Best-of-N sampling for inference, where the algorithm samples N responses from the policy and selects the best one according to a given criteria. The different agent variants are created by changing components such as inference methods, exploration strategies, and learning components, allowing for analysis of the impact of each on performance.

read the caption

Figure 6: Win rate comparison of different agent variants when using (Left) policy and (Right) Best-of-N sampling for inference.

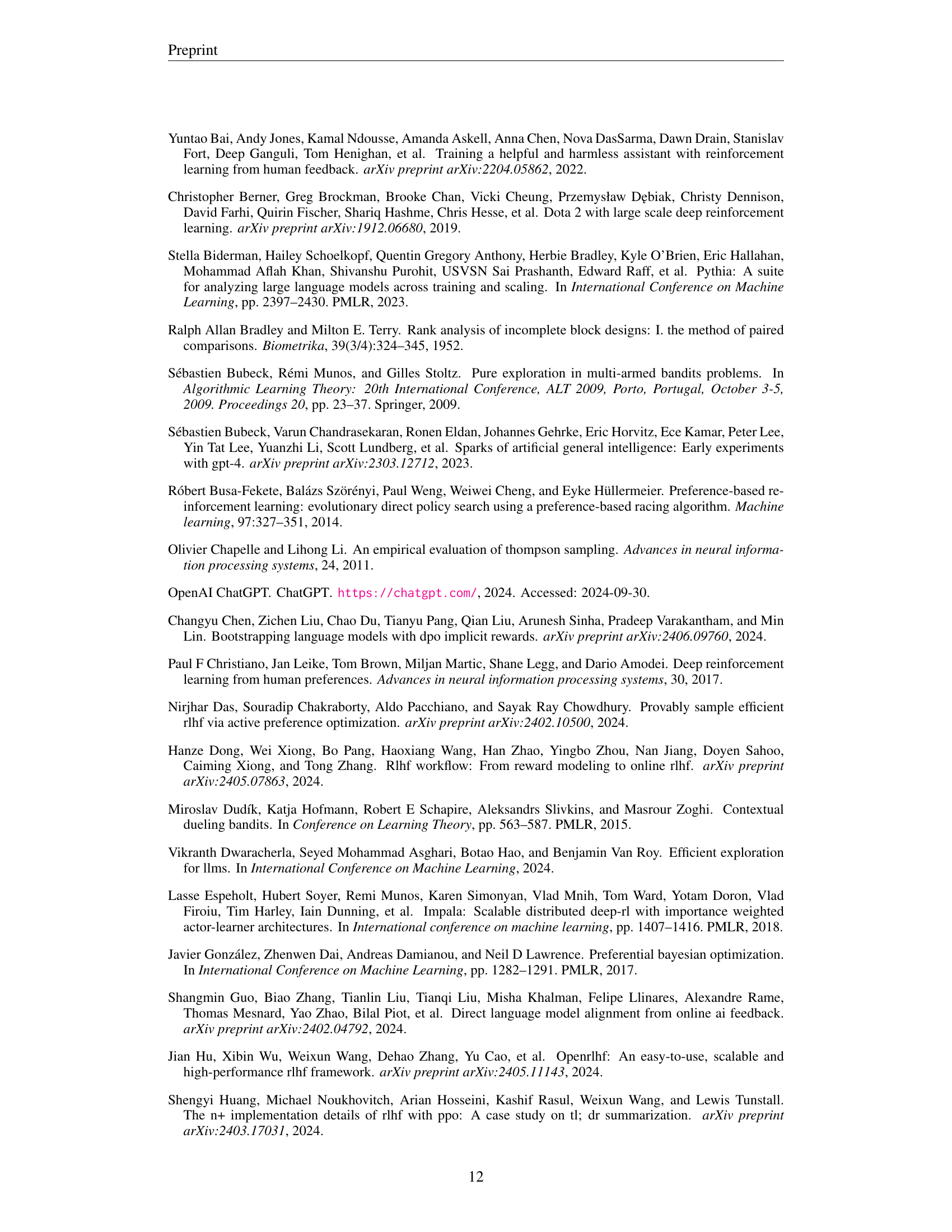

🔼 Figure 7 presents a comparison of different exploration strategies within the context of online LLM alignment. The left and middle panels display the win rates achieved by three exploration strategies (Uncertainty, E&E-TS, BAI-TS) in both explore-exploit (E&E) and best-arm identification (BAI) settings, respectively. The right panel shows a comparison of win rates when a GPT4-mini model is used to simulate human feedback in the alignment process. The results highlight how different exploration approaches perform under various learning objectives and feedback mechanisms.

read the caption

Figure 7: (Left and Middle) Win rate comparison of different exploration strategies measured in E&E and BAI settings. (Right) Win rate comparison of different agents when using GPT4o-mini to simulate human feedback via LLM-as-a-judge.

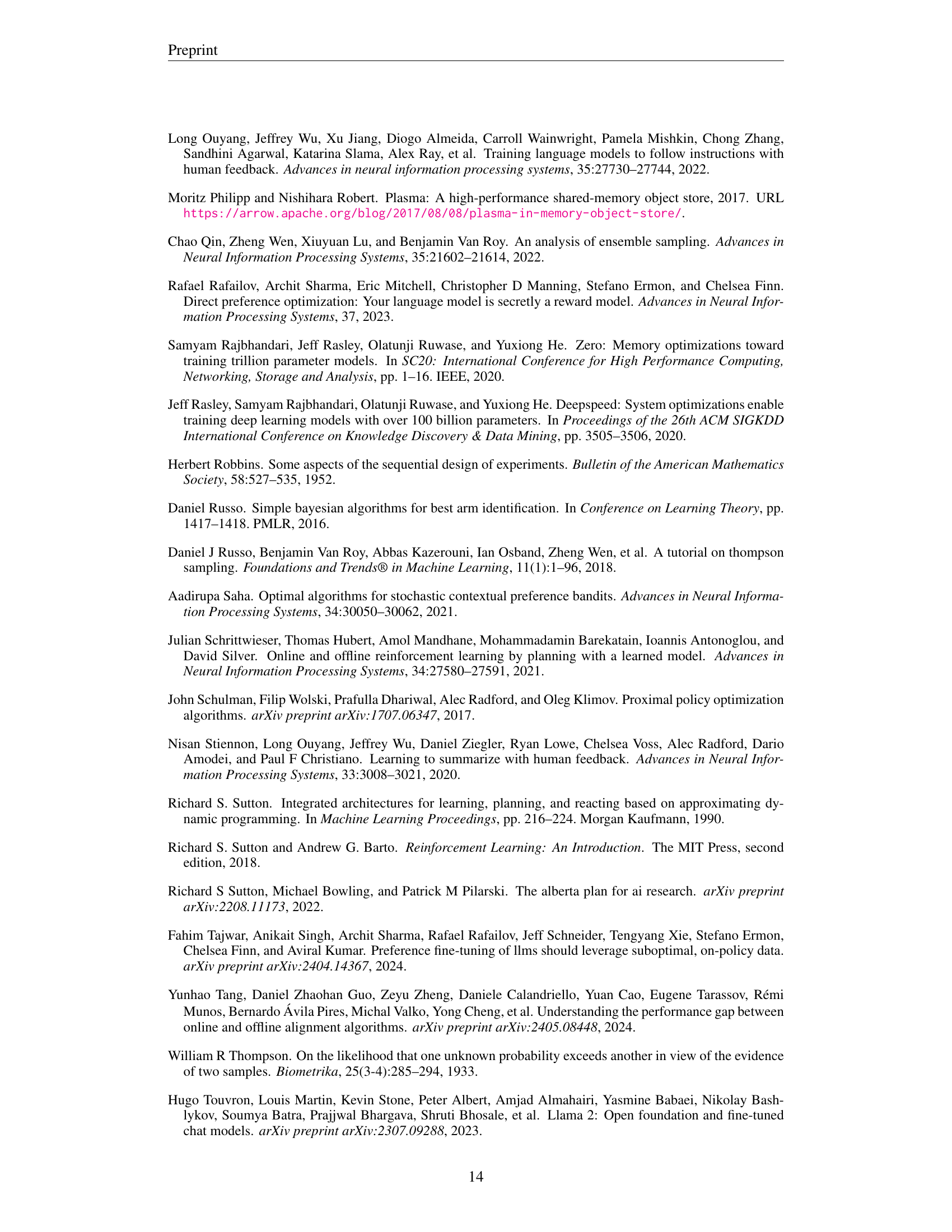

🔼 This figure illustrates two different configurations used in the experimental setup to benchmark the efficiency of the online DPO training. Config 1 shows a full collocation approach where all the workloads (actor, learner, oracle) are fully collocated on all available GPUs. This maximizes GPU utilization but demands high GPU memory. Config 2 demonstrates a half collocation strategy where actors and oracles are collocated on half of the GPUs while the learner utilizes the other half. This approach reduces memory pressure but introduces data dependency and potential idle time due to asynchronous updates.

read the caption

Figure 8: Two example configurations of oat used in benchmarking experiments.

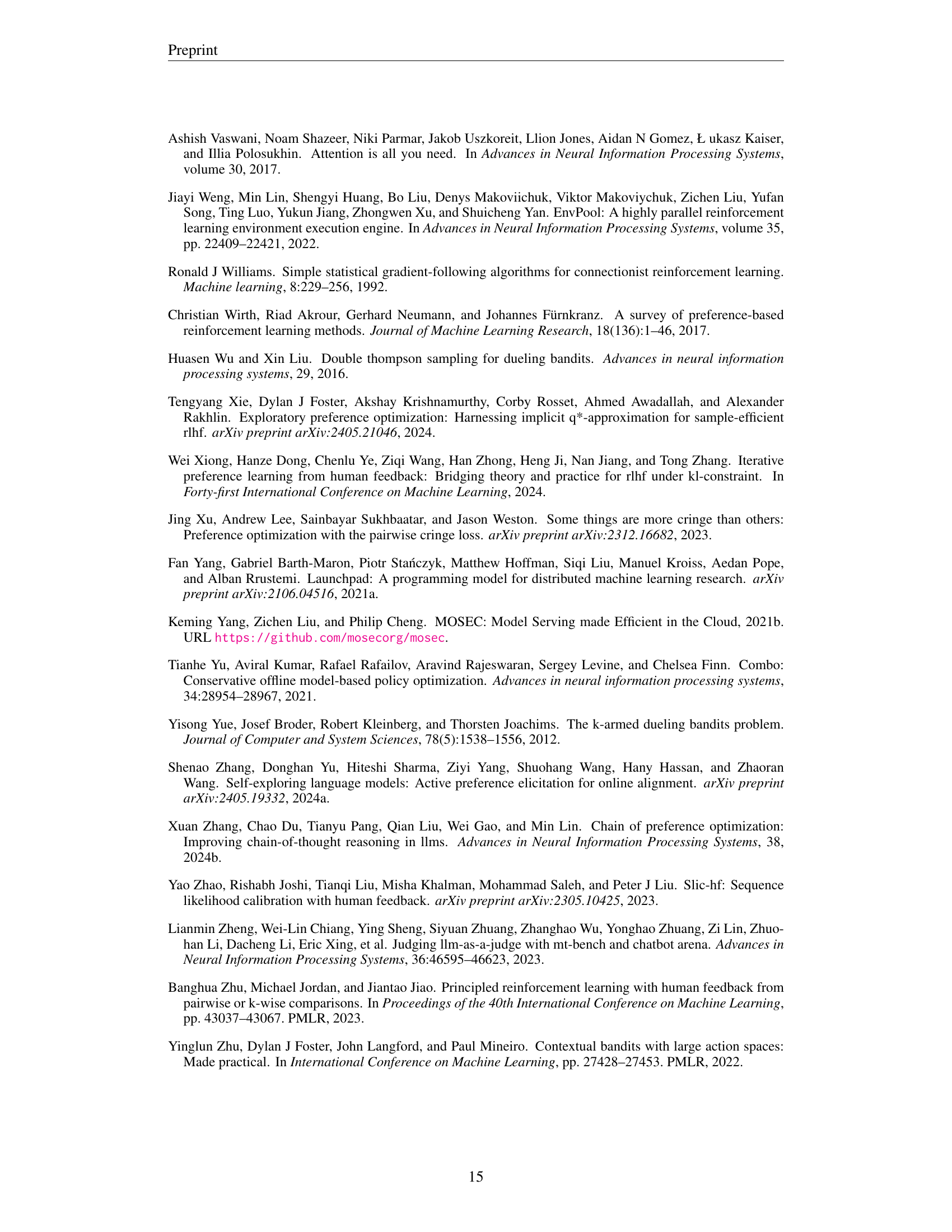

🔼 Figure 9 presents a bar chart comparing the training latency of the online DPO algorithm using two different systems:

sail-sg/oatandhuggingface/trl. The latency is averaged over 10 batches (which equates to 1280 samples in total). The chart breaks down the latency for three different parts of the training process: response generation, oracle calls (reward calculations), and the learner update step. The comparison highlights thatsail-sg/oatachieves significantly lower latency across different model scales (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters) and system configurations.read the caption

Figure 9: Averaged training latency (over 10 batches, equivalent to 1280 samples) comparing sail-sg/oat against huggingface/trl.

Full paper#