↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Deploying large language models (LLMs) on robots is challenging due to limited onboard computational resources. Current LLMs are resource-intensive, making real-time control difficult. This hinders progress in building generalist robots capable of understanding complex instructions and executing various tasks.

DeeR-VLA tackles this challenge by using a dynamic early-exit framework. It cleverly adjusts the size of the active LLM based on the complexity of each task. This approach avoids redundant computation and significantly reduces both computational cost and GPU memory usage. The authors demonstrate DeeR-VLA’s effectiveness on a benchmark, confirming its ability to deliver competitive performance with far less resource usage.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on resource-constrained robotic systems and efficient large language model inference. It directly addresses the challenges of deploying powerful LLMs on robots with limited computational resources and offers a practical solution. The proposed method’s potential for improving real-world robotic applications and its use of multi-exit architectures make it highly relevant to current research trends in AI and robotics, opening new paths for future studies on dynamic model adaptation and efficient LLM deployment.

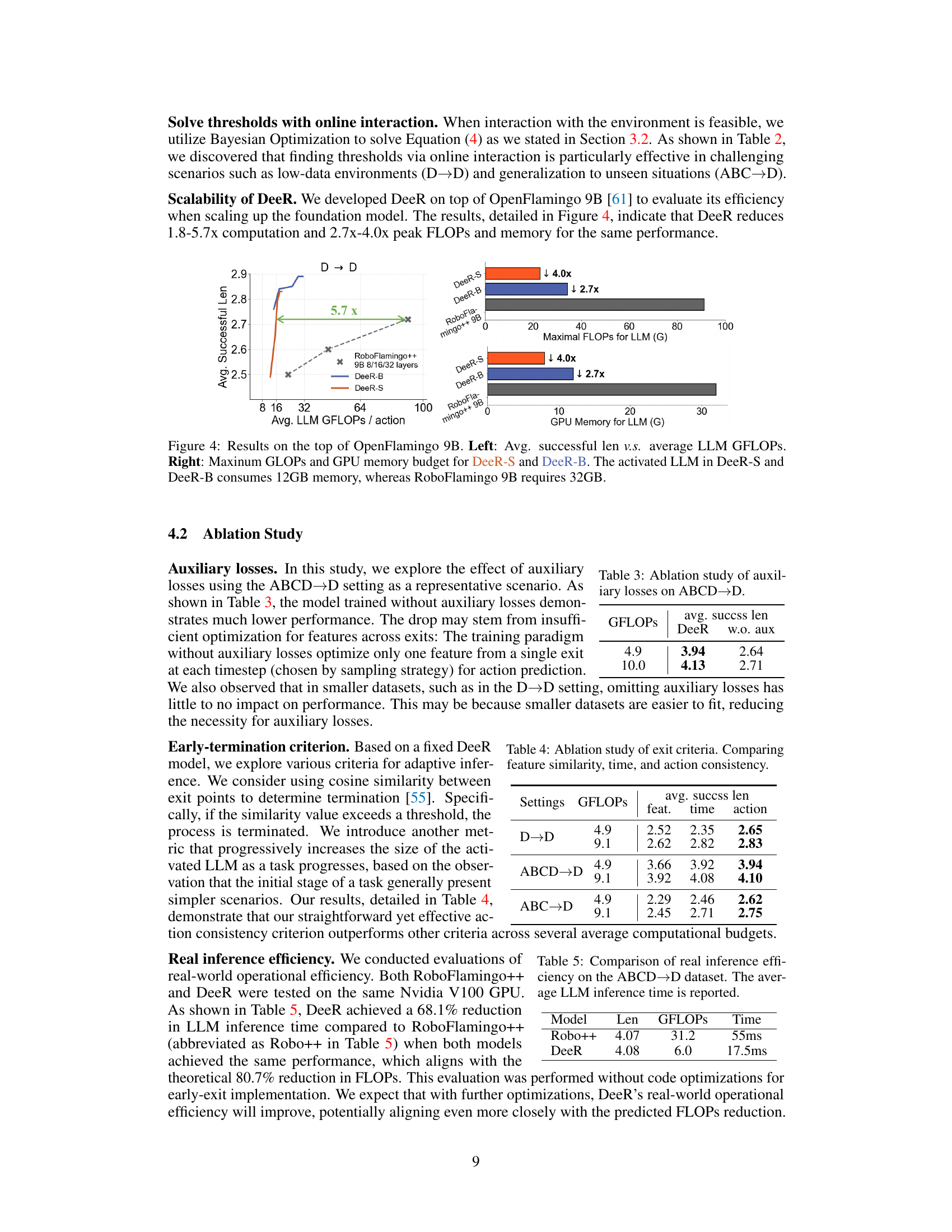

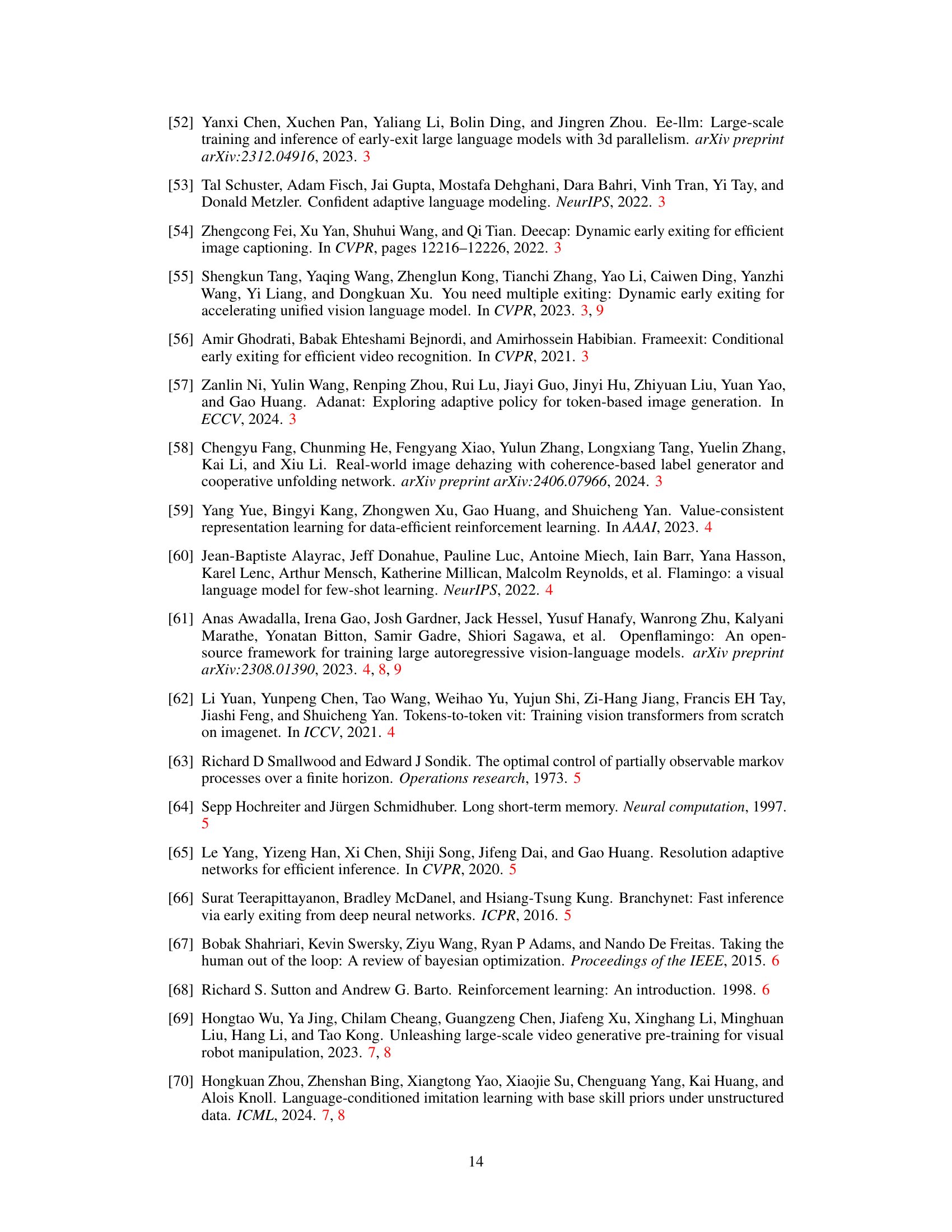

Visual Insights#

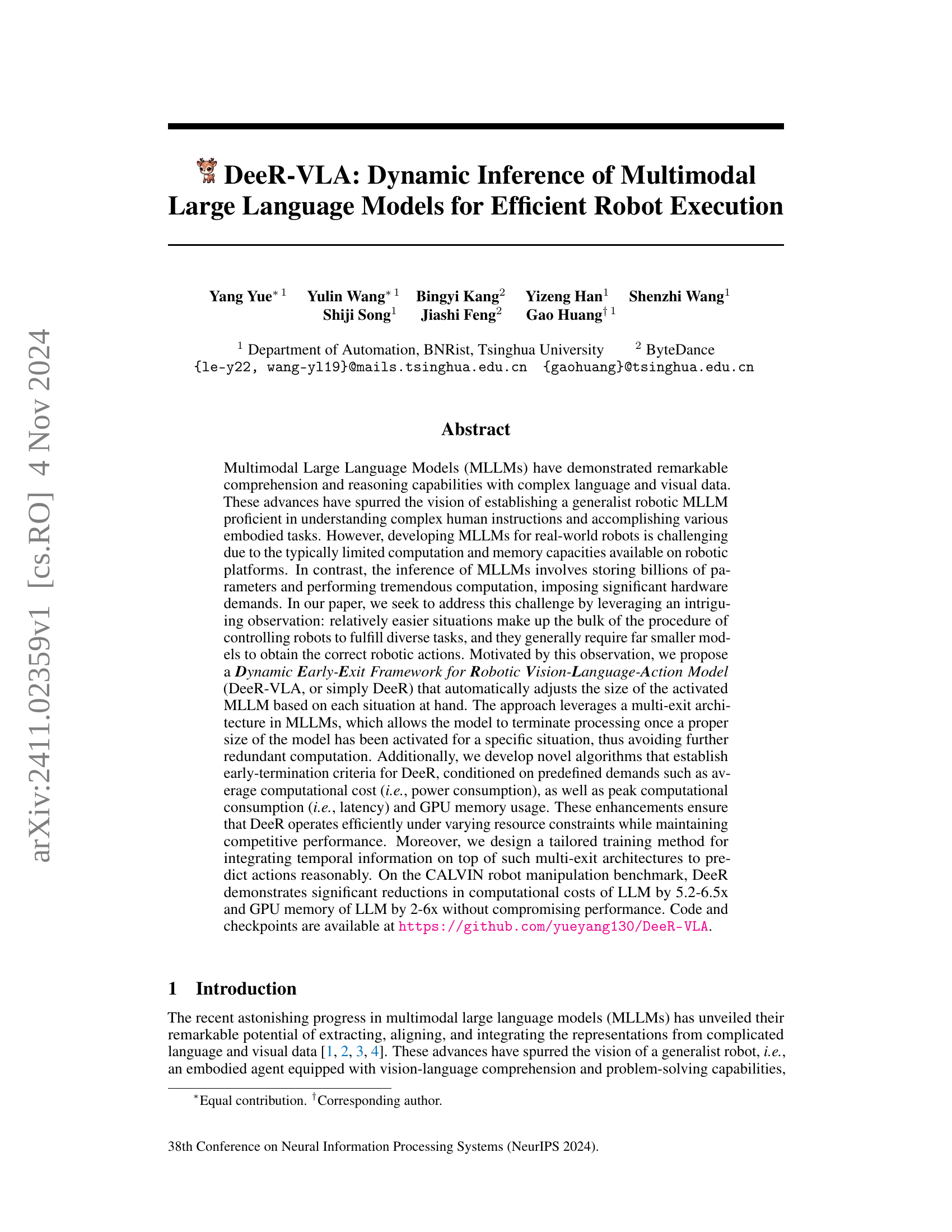

🔼 This figure illustrates the dynamic inference and training process of the DeeR model. The left panel shows how DeeR dynamically adjusts the size of the activated MLLM based on the current situation (task instruction and observation) and resource constraints. The right panel details the training process, which employs a random sampling strategy to minimize the discrepancy between training and inference and uses multiple auxiliary action heads to optimize the MLLM.

read the caption

Figure 1: Left: Dynamic inference of DeeR. For inference, we adaptively activate an appropriate size of MLLM based on an exit criterion c𝑐citalic_c, which accounts for the current situation (including task instruction l𝑙litalic_l and observation otsubscript𝑜𝑡o_{t}italic_o start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) and predefined computational and GPU memory budgets. The language instruction and gripper camera image, not shown in this figure, are also inputs to the MLLM. An action is then obtained using the intermediate feature x~tc(t)subscriptsuperscript~𝑥𝑐𝑡𝑡\tilde{x}^{c(t)}_{t}over~ start_ARG italic_x end_ARG start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_c ( italic_t ) end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and historical information. Right: Training of DeeR.We randomly sample features from all exits during training. This strategy helps minimize the discrepancy between training and dynamic inference. Moreover, we employ several auxiliary action heads (AuxH) to better optimize the MLLM.

| # LLM layers | 24 | 12 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFLOPs/action (LLM) | 31.2 | 15.6 | 7.8 |

| Task success rate % | 78.9 | 78.0 | 75.7 |

🔼 This table shows the trade-off between computational cost and task success rate when using different sizes of the language model (LLM) within the RoboFlamingo model on the CALVIN LH-MTLC D→D benchmark. It demonstrates that while larger LLMs (more layers, higher FLOPs) achieve slightly better performance, the increase in computation is not proportional to the gain in accuracy. The focus is on the LLM component within the larger multimodal language model (MLLM) because it consumes most of the resources. FLOPs (floating point operations) and GPU memory usage are reported for the LLM, illustrating the efficiency implications of choosing a model size.

read the caption

Table 1: Computation cost v.s. task successful rate222Average successful rate over all subtasks in the long-horizon chains.(RoboFlamingo++) on CALVIN LH-MTLC chanllenge D→→\rightarrow→D. Notably, we mainly focus on the core component, LLM, of the MLLM, which comprises the majority of parameters. We vary the size of the LLM to examine its impact. For a focused comparison, we report the FLOPs (and GPU memory usage) of the LLM in our paper, unless otherwise specified.

In-depth insights#

Efficient MLLM Inference#

Efficient Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) inference is crucial for real-world robotic applications due to the typically limited computational resources of robotic platforms. The inherent complexity of MLLMs, involving billions of parameters and extensive computations, poses a significant challenge. Strategies to address this include efficient model architectures, model compression techniques (like quantization and pruning), and dynamic computation allocation. Dynamic inference methods, such as early exiting, adaptively adjust the model’s size based on the complexity of the task at hand, avoiding unnecessary computations for simpler scenarios. This approach offers a compelling balance between performance and efficiency, enabling the deployment of powerful MLLMs on resource-constrained robots while maintaining competitive accuracy. Furthermore, integrating temporal information into the inference process, considering historical data for more informed predictions, enhances performance and reduces redundancy. Future research will likely focus on further optimizing existing techniques and exploring novel methods for achieving even greater efficiency in MLLM inference for robotics and other resource-limited applications.

Multi-exit Architecture#

The proposed multi-exit architecture is a key innovation for efficient multimodal large language model (MLLM) inference in resource-constrained robotic applications. Instead of always processing the full MLLM, this approach allows the model to dynamically exit at various intermediate layers depending on the complexity of the current robotic task. Early exits are triggered when the model determines that sufficient information has been processed to accurately predict the necessary robotic action. This dynamic approach is particularly valuable because simpler tasks require less processing, avoiding the computational overhead of fully activating the larger model. The effectiveness of the multi-exit architecture is further enhanced by novel algorithms that determine appropriate exit points based on predefined resource constraints, such as latency and power consumption. This ensures that the MLLM operates efficiently under varying resource conditions. The system’s adaptive nature is critical for deploying LLMs on real-world robots with limited computational power and memory.

Adaptive Inference#

The section on Adaptive Inference is crucial to DeeR’s efficiency. It details how the model dynamically adjusts the size of the MLLM activated, based on a termination criterion that balances computational cost against task complexity. Early termination criteria, conditioned on average and peak computational costs or GPU memory usage, are a key innovation. The model cleverly leverages the observation that simpler tasks require smaller models, avoiding redundant computation. The algorithms for establishing these criteria are carefully designed to balance resource constraints with desired performance. Furthermore, the adaptive inference mechanisms showcase a flexible and dynamic approach, allowing the system to adjust its computational demands online, demonstrating the model’s adaptability to different resource environments. The core of the method is determining an appropriate model size to activate based on the context, enhancing efficiency without sacrificing accuracy.

Training Methodology#

The paper introduces a novel training methodology for a dynamic multi-exit architecture designed for efficient robotic control. A key challenge addressed is the discrepancy between the dynamic inference process at runtime and the static training process. To mitigate this, the authors propose a random sampling strategy during training, where features from all possible exit points are sampled and fed to the action head. This helps the model learn effective representations across all exit points, preparing it for the dynamic selection of optimal LLM sizes at inference. This random sampling strategy is further enhanced with two variations, allowing for both uniform and temporally-segmented sampling, adding to the richness and robustness of the approach. Furthermore, auxiliary action heads are used at each exit point to improve the quality of the intermediate feature representations and guide the learning process for appropriate action prediction. The integration of auxiliary heads with a tailored loss function appears crucial in ensuring the effectiveness of early exiting without sacrificing accuracy. This innovative training method directly tackles the complexities of dynamic neural networks for robotic tasks, resulting in a model that operates more efficiently in real-world conditions.

Future Work & Limits#

Future research directions for DeeR-VLA should prioritize enhancing the efficiency and robustness of the visual encoder, currently a significant computational bottleneck. Exploring alternative early-exit criteria beyond action consistency, and perhaps incorporating uncertainty estimation, could lead to more adaptive and reliable performance. Investigating the generalizability of DeeR-VLA to more diverse robotic platforms and tasks is crucial, especially in real-world, unstructured environments with greater variability. Addressing the challenges of deploying DeeR-VLA on resource-constrained embedded systems through model compression and optimization techniques remains a key limitation. Finally, developing more rigorous evaluation methodologies tailored to the unique characteristics of dynamic MLLM architectures is vital for assessing the overall effectiveness of DeeR-VLA in real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

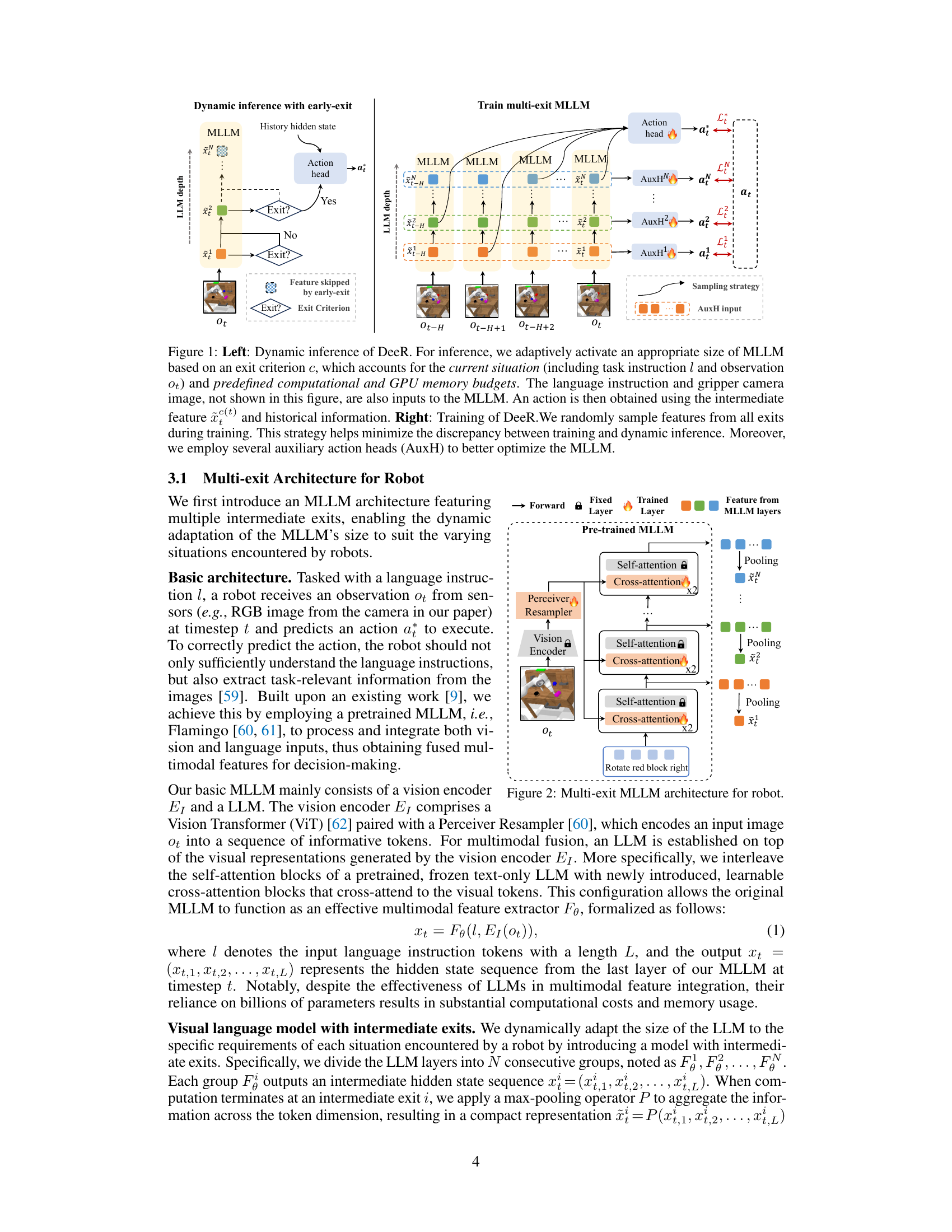

🔼 This figure illustrates the multi-exit architecture of the Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) used in DeeR for robot control. It shows how the model is designed with multiple intermediate exits, allowing the model to terminate processing once a proper size of the model has been activated for a specific situation, thus avoiding further redundant computation. The diagram details the components including a vision encoder (processing visual observations), a language input module, multiple layers of the MLLM with intermediate outputs at multiple exits, and an action prediction head that takes the output from an appropriate exit point to generate robotic actions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Multi-exit MLLM architecture for robot.

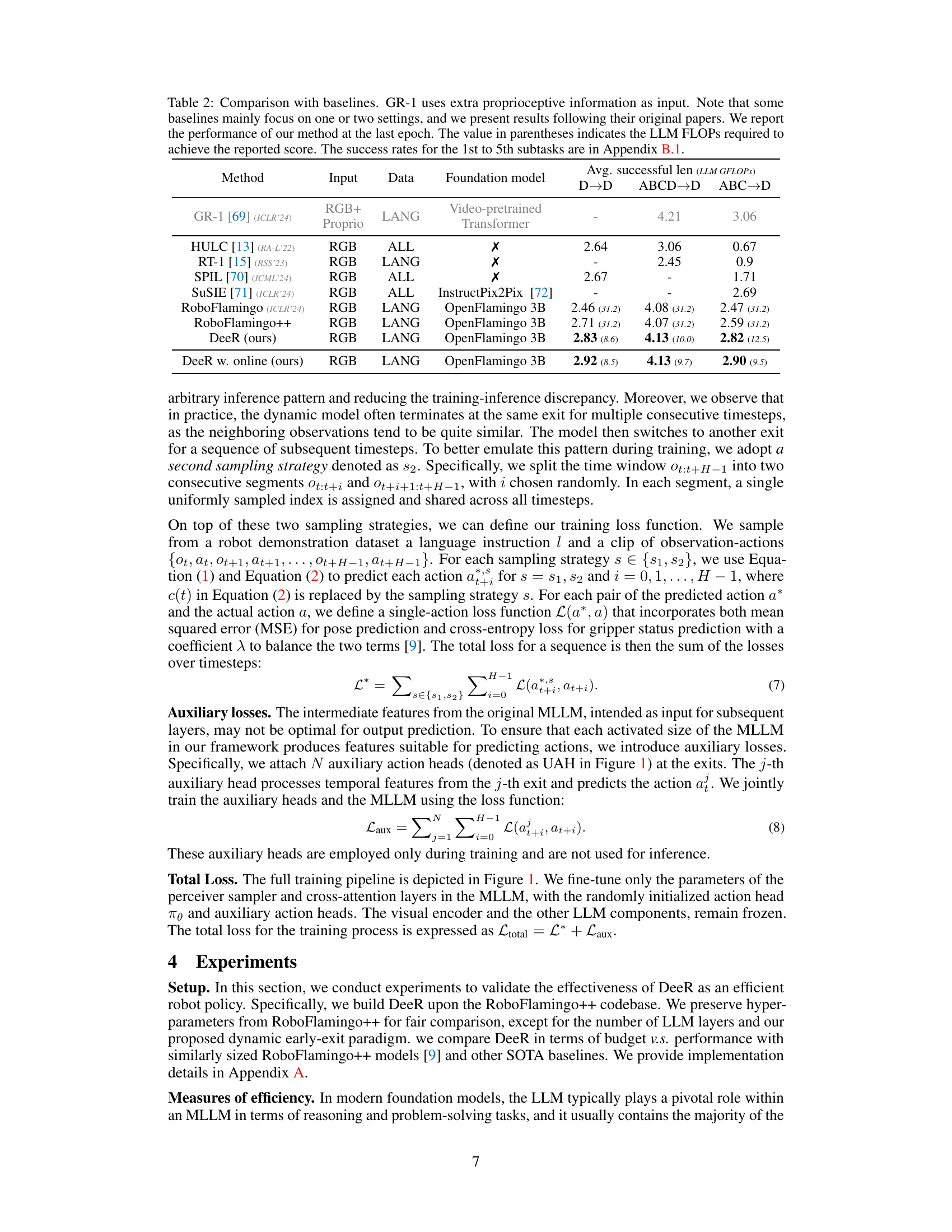

🔼 Figure 3 presents the results of experiments using the OpenFlamingo 3B model. The upper part shows a comparison of the average successful task completion length against the average LLM GFLOPs (floating point operations per second) consumed. The lower part shows the peak GFLOPs and GPU memory usage during inference. Two versions of the DeeR model (DeeR-S and DeeR-B) are compared, which differ in their resource constraints; however, they both use the same underlying model architecture. For fair comparison, DeeR retains the architecture and hyperparameters of RoboFlamingo++, except for the dynamic early-exit mechanism.

read the caption

Figure 3: Results atop OpenFlamingo 3B. Upper: Avg. successful len v.s. avg. LLM GFLOPs. Bottom: Peak GLOPs and GPU memory for LLM. Different colors indicate different peak FLOPs and GPU memory budgets, denoted as DeeR-S and DeeR-B (they share a fixed model). DeeR preserve all the architecture and hyperparameters from RoboFlamingo++ for fair comparisons, except for our dynamic early-exit paradigm.

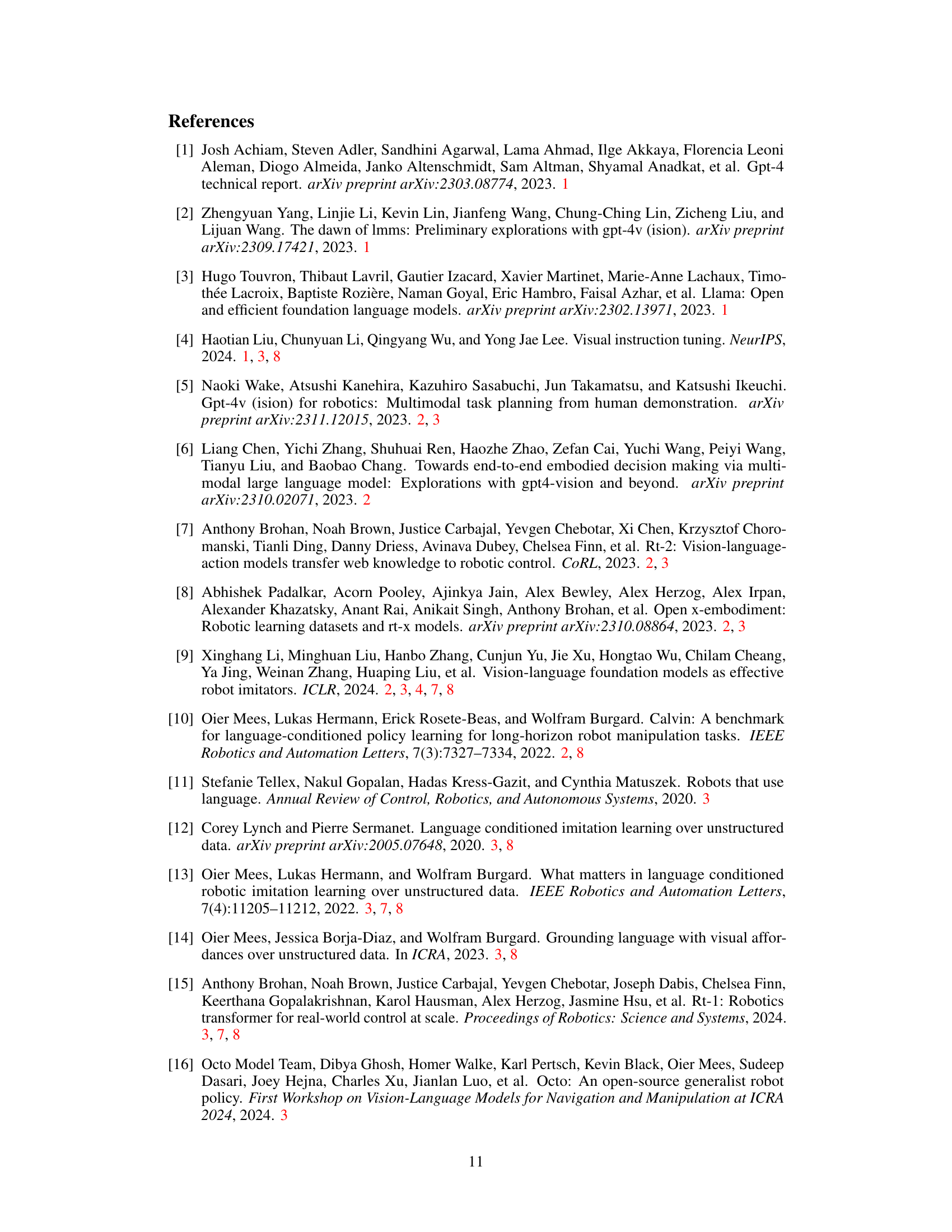

🔼 Figure 4 presents a comparison of the performance and resource usage of DeeR and RoboFlamingo++ using the OpenFlamingo 9B model. The left panel shows that DeeR achieves a similar average task success length as RoboFlamingo++ while using significantly fewer average LLM GFLOPs. The right panel highlights the memory efficiency of DeeR. Both DeeR-S and DeeR-B configurations operate with a maximum of 12 GB of GPU memory for the activated LLM, a substantial reduction compared to the 32 GB required by RoboFlamingo++ 9B.

read the caption

Figure 4: Results on the top of OpenFlamingo 9B. Left: Avg. successful len v.s. average LLM GFLOPs. Right: Maxinum GLOPs and GPU memory budget for DeeR-S and DeeR-B. The activated LLM in DeeR-S and DeeR-B consumes 12GB memory, whereas RoboFlamingo 9B requires 32GB.

🔼 This figure visualizes the dynamic inference process of DeeR across various tasks in the CALVIN environment. Each row represents a distinct task, showing a sequence of images from the robot’s camera. The numbers overlaid on the images indicate the termination exit index chosen by DeeR, signifying the model size dynamically selected based on task complexity. A lower exit index signifies a simpler situation requiring a smaller model, while a higher index denotes a more challenging situation demanding a larger model. This illustrates DeeR’s adaptive inference capability, adapting computational resources according to the situation’s complexity.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualization of DeeR rollouts in the CALVIN environment. Please zoom in to view details. The numbers indicate the termination exit index. Situations with a lower exit index are recognized as ‘easier’ ones.

More on tables

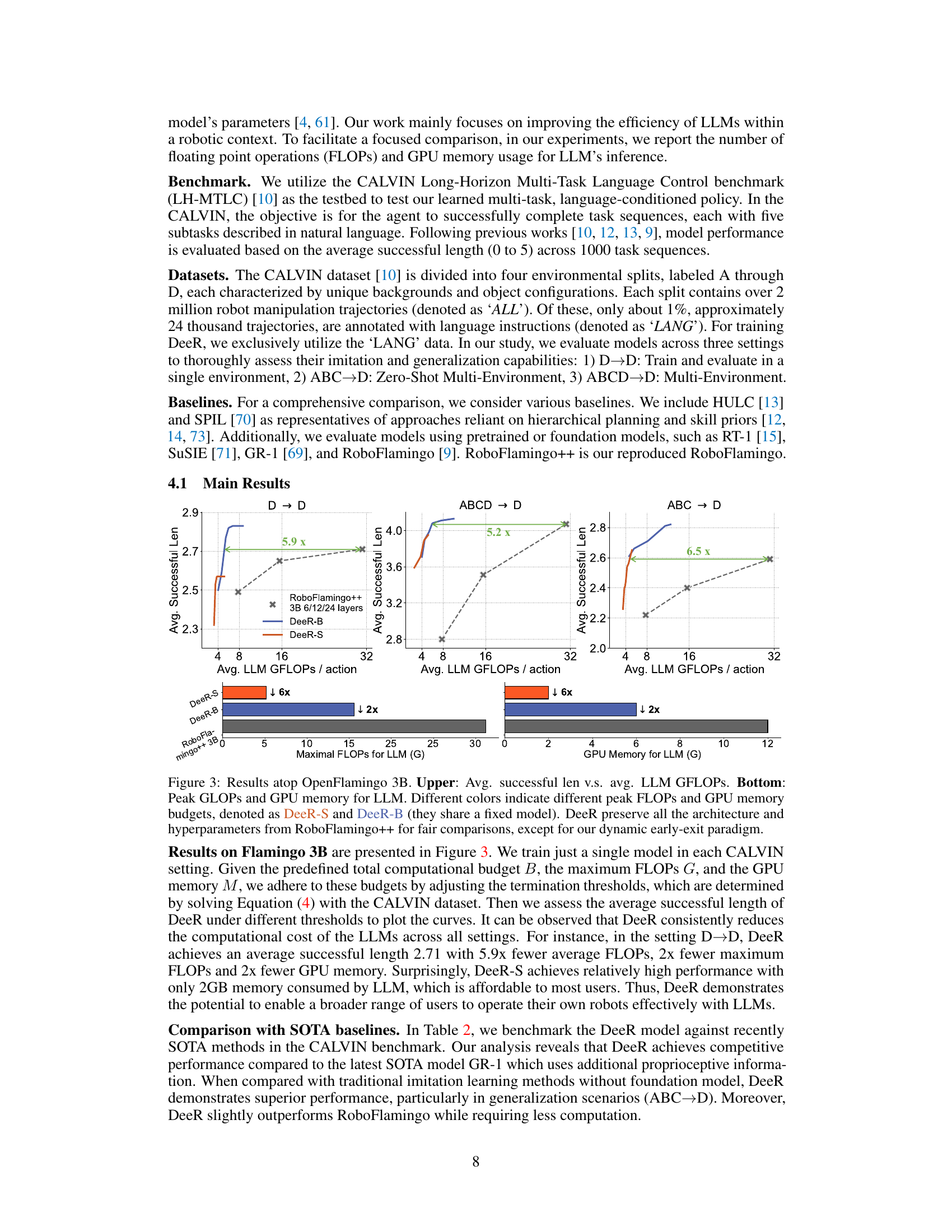

| Method | Input | Data | Foundation model | D→D | ABCD→D | ABC→D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GR-1 [69] (ICLR’24) | RGB+ Proprio | LANG | Video-pretrained Transformer | - | 4.21 | 3.06 |

| HULC [13] (RA-L’22) | RGB | ALL | ✗ | 2.64 | 3.06 | 0.67 |

| RT-1 [15] (RSS’23) | RGB | LANG | ✗ | - | 2.45 | 0.9 |

| SPIL [70] (ICML’24) | RGB | ALL | ✗ | 2.67 | - | 1.71 |

| SuSIE [71] (ICLR’24) | RGB | ALL | InstructPix2Pix [72] | - | - | 2.69 |

| RoboFlamingo (ICLR’24) | RGB | LANG | OpenFlamingo 3B | 2.46 (31.2) | 4.08 (31.2) | 2.47 (31.2) |

| RoboFlamingo++ | RGB | LANG | OpenFlamingo 3B | 2.71 (31.2) | 4.07 (31.2) | 2.59 (31.2) |

| DeeR (ours) | RGB | LANG | OpenFlamingo 3B | 2.83 (8.6) | 4.13 (10.0) | 2.82 (12.5) |

| DeeR w. online (ours) | RGB | LANG | OpenFlamingo 3B | 2.92 (8.5) | 4.13 (9.7) | 2.90 (9.5) |

🔼 Table 2 compares the performance of DeeR with several state-of-the-art baselines on the CALVIN benchmark. It highlights DeeR’s efficiency gains by showing average successful lengths achieved across various settings (D→D, ABCD→D, ABC→D) while comparing computational costs (LLM GFLOPs) . The table notes that GR-1 uses additional proprioceptive information and that some baselines reported results for only a subset of the settings; DeeR’s results presented are from its final training epoch. Detailed success rates for individual subtasks are available in the supplementary materials (Section B.1).

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison with baselines. GR-1 uses extra proprioceptive information as input. Note that some baselines mainly focus on one or two settings, and we present results following their original papers. We report the performance of our method at the last epoch. The value in parentheses indicates the LLM FLOPs required to achieve the reported score. The success rates for the 1st to 5th subtasks are in Section B.1.

| RGB+ | Proprio |

|---|

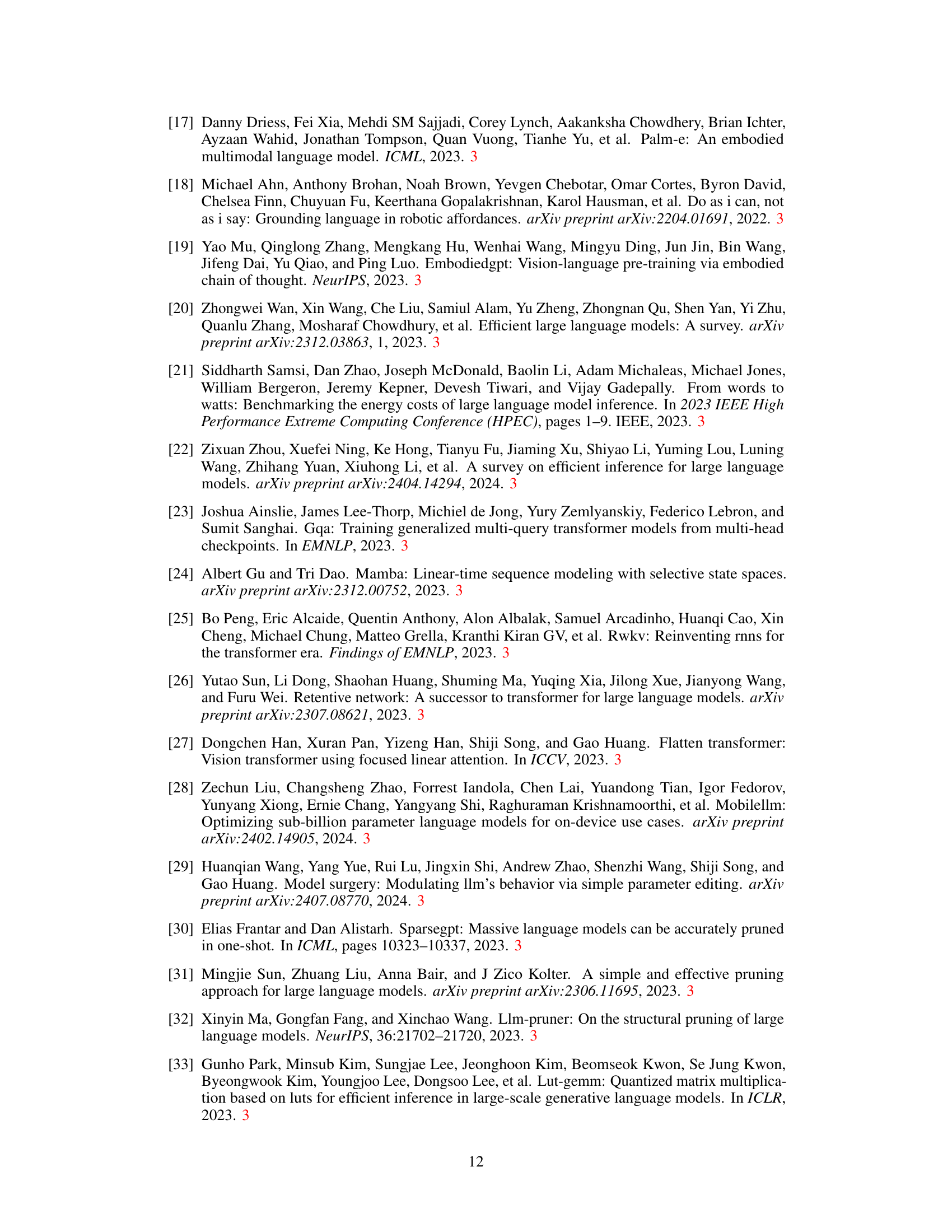

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of auxiliary losses on the ABCD→D experimental setting within the DeeR model. It compares the performance of the model with and without auxiliary losses, showing their contribution to the overall accuracy and the effect on the successful length of task completion.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study of auxiliary losses on ABCD→→\rightarrow→D.

| Video-pretrained | Transformer |

|---|

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of different early-exit criteria on the performance of the DeeR model. Three criteria are compared: feature similarity (measuring the similarity between action predictions from adjacent intermediate features), time (progressively increasing the model size as a task progresses), and action consistency (using the consistency of action predictions from differently sized MLLMs as a criterion). The table shows the average successful length and average GFLOPs per action for each criterion across different experimental settings (D→D, ABC→D, ABCD→D) to analyze their effectiveness and efficiency.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study of exit criteria. Comparing feature similarity, time, and action consistency.

| GFLOPs | DeeR | w.o. aux |

|---|---|---|

| 4.9 | 3.94 | 2.64 |

| 10.0 | 4.13 | 2.71 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the real-world inference efficiency between DeeR and RoboFlamingo++, focusing on the ABCD→D setting of the CALVIN benchmark. The comparison specifically highlights the average time taken for Large Language Model (LLM) inference. This demonstrates the computational speedup achieved by DeeR in real-world robotic applications compared to the baseline model.

read the caption

Table 5: Comparison of real inference efficiency on the ABCD→→\rightarrow→D dataset. The average LLM inference time is reported.

| Settings | GFLOPs | avg. succss len | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D→D | 4.9 | 2.52 | 2.35 | 2.65 | |

| 9.1 | 2.62 | 2.82 | 2.83 | ||

| ABCD→D | 4.9 | 3.66 | 3.92 | 3.94 | |

| 9.1 | 3.92 | 4.08 | 4.10 | ||

| ABC→D | 4.9 | 2.29 | 2.46 | 2.62 | |

| 9.1 | 2.45 | 2.71 | 2.75 |

🔼 This table presents the results of applying quantization techniques to the DeeR model. It shows how different levels of quantization (float32, float16, int4) affect both the model size (memory) and the average successful length of tasks completed. This demonstrates the trade-off between model compression and performance.

read the caption

Table 6: DeeR with quantization on the ABCD→→\rightarrow→D setting.

| Model | Len | GFLOPs | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robo++ | 4.07 | 31.2 | 55ms |

| DeeR | 4.08 | 6.0 | 17.5ms |

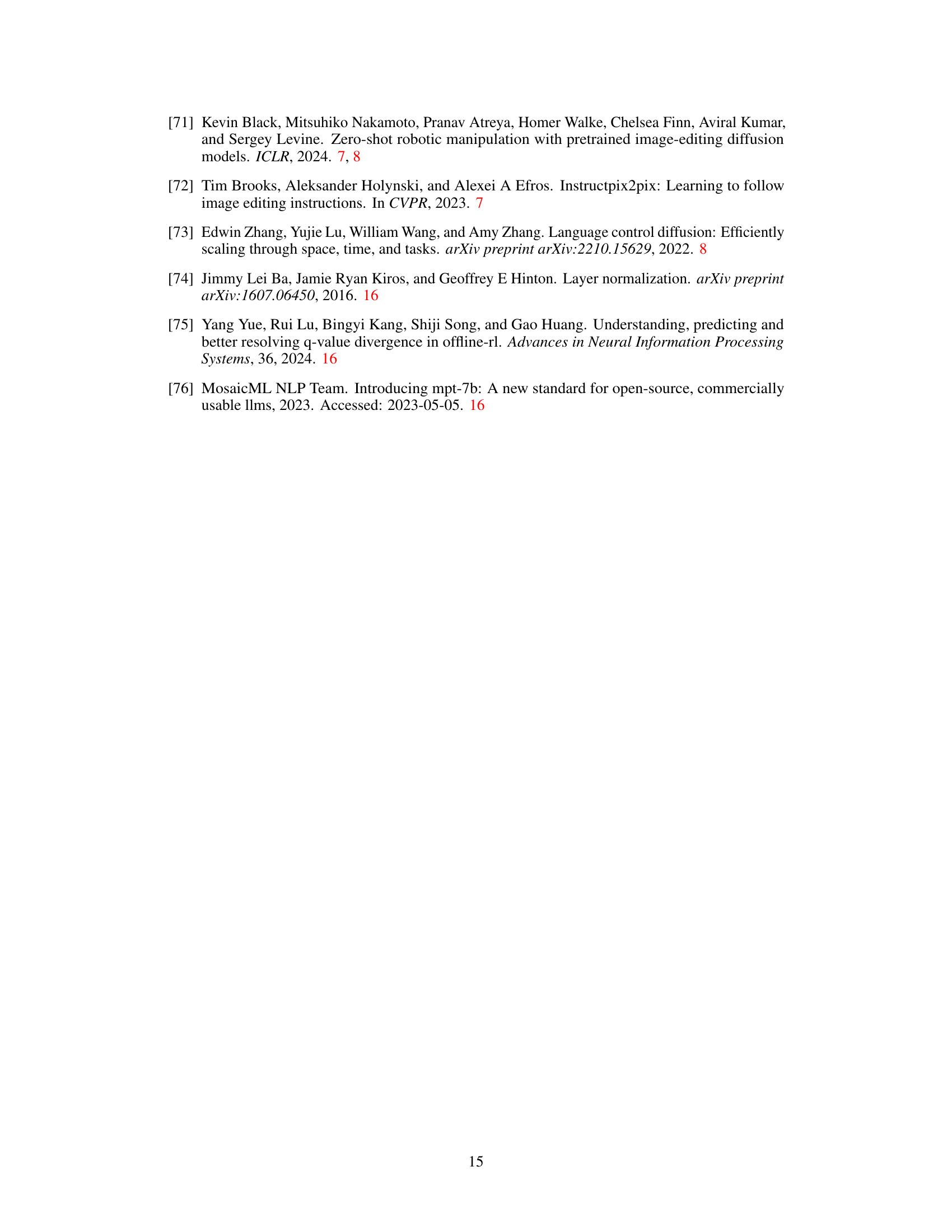

🔼 This table presents the architecture details for the OpenFlamingo models used in the paper. It shows the language model, vision encoder, number of layers in the Large Language Model (LLM), and the cross-attention interval used in the model architecture. The cross-attention interval indicates how frequently cross-attention layers are interspersed within the self-attention layers of the LLM, facilitating effective multimodal fusion.

read the caption

Table 7: Architecture details of the OpenFlamingo models. ‘xattn interval’ means cross-attention interval.

| DeeR | Memory | Avg Len |

|---|---|---|

| float32 | 6G | 4.13 |

| float16 | 3G | 4.12 |

| int4 | 1.7G | 3.91 |

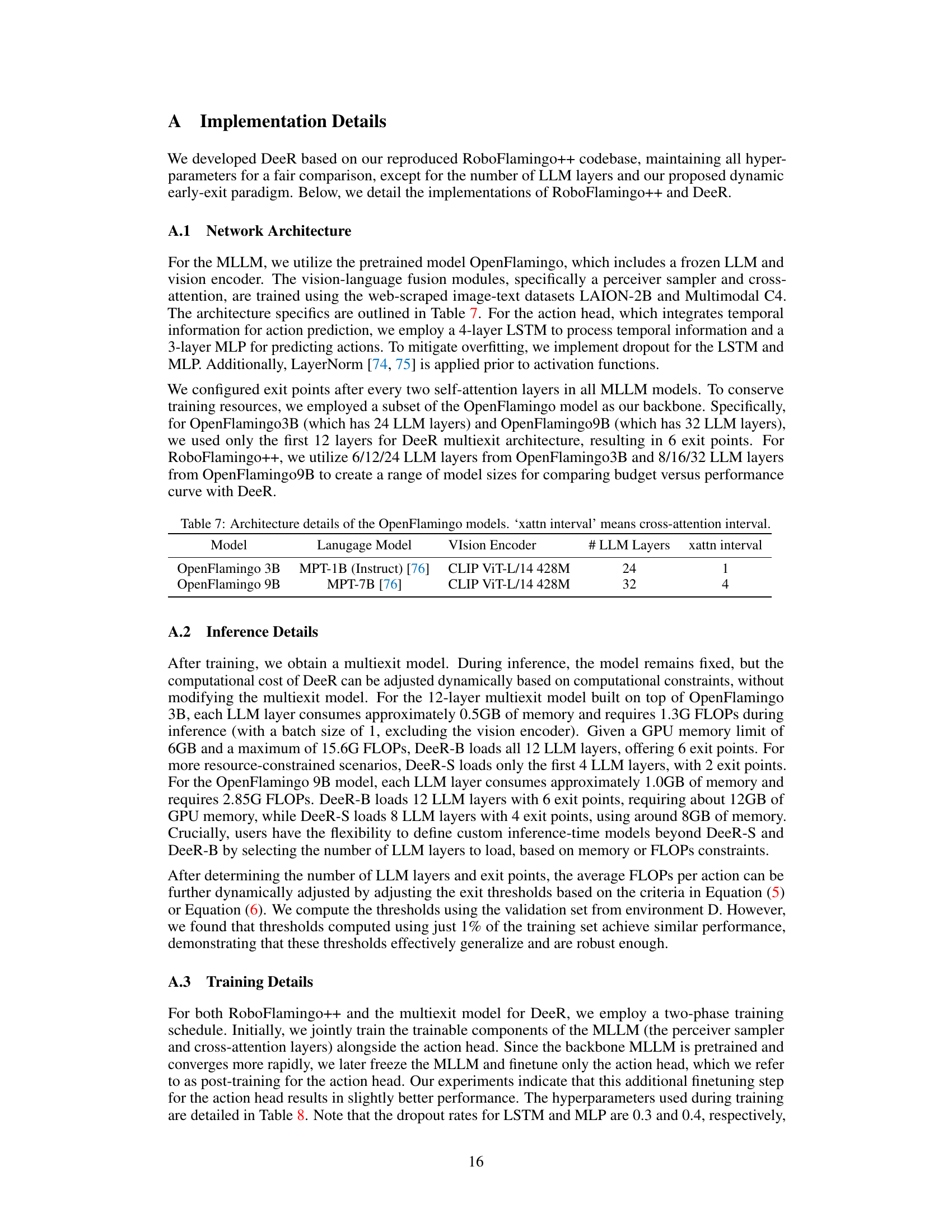

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used during the training process for the DeeR model on three different settings: D→D, ABC→D, and ABCD→D. The settings represent different experimental conditions to evaluate the model’s performance and generalization ability. The hyperparameters include details about the batch size, optimizer, learning rates for the MLLM and the action head, learning rate schedule, warm-up steps, dropout rates for LSTM and MLP layers, the number of training epochs (both joint training and post-training for the action head), and the coefficient λ, and LSTM window size.

read the caption

Table 8: Training hyper-parameters for setting D→→\rightarrow→D/ABC→→\rightarrow→D/ABCD→→\rightarrow→D.

| Model | Lanugage Model | VIsion Encoder | # LLM Layers | xattn interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenFlamingo 3B | MPT-1B (Instruct) [76] | CLIP ViT-L/14 428M | 24 | 1 |

| OpenFlamingo 9B | MPT-7B [76] | CLIP ViT-L/14 428M | 32 | 4 |

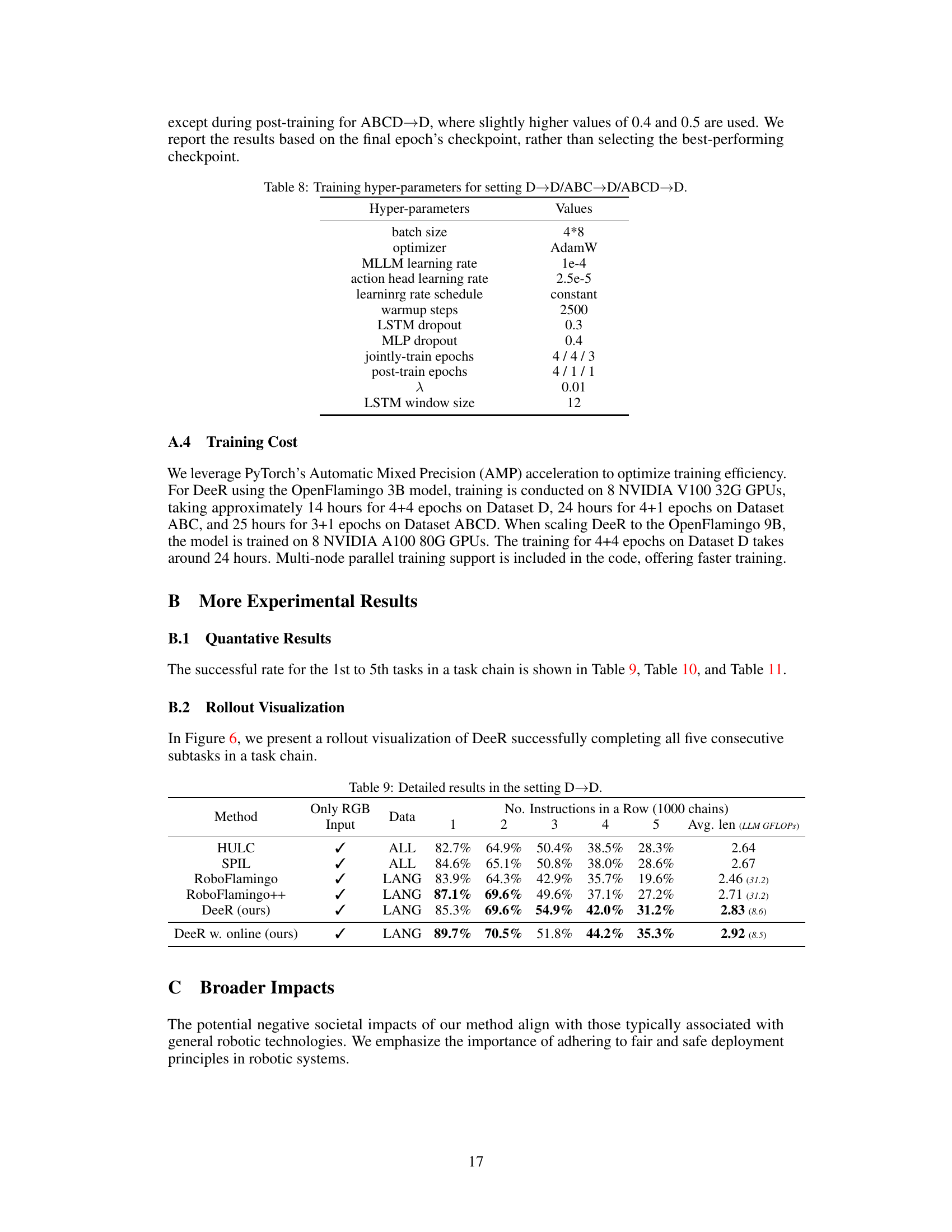

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the experimental results obtained for the D→D setting in the CALVIN benchmark. It shows the average task completion length and the percentage of successful task completions for each of the five subtasks in the task chains. Different methods are compared and contrasted, demonstrating the performance of each approach for various input modalities and data sources.

read the caption

Table 9: Detailed results in the setting D→→\rightarrow→D.

| Hyper-parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| batch size | 4*8 |

| optimizer | AdamW |

| MLLM learning rate | 1e-4 |

| action head learning rate | 2.5e-5 |

| learninrg rate schedule | constant |

| warmup steps | 2500 |

| LSTM dropout | 0.3 |

| MLP dropout | 0.4 |

| jointly-train epochs | 4 / 4 / 3 |

| post-train epochs | 4 / 1 / 1 |

| λ | 0.01 |

| LSTM window size | 12 |

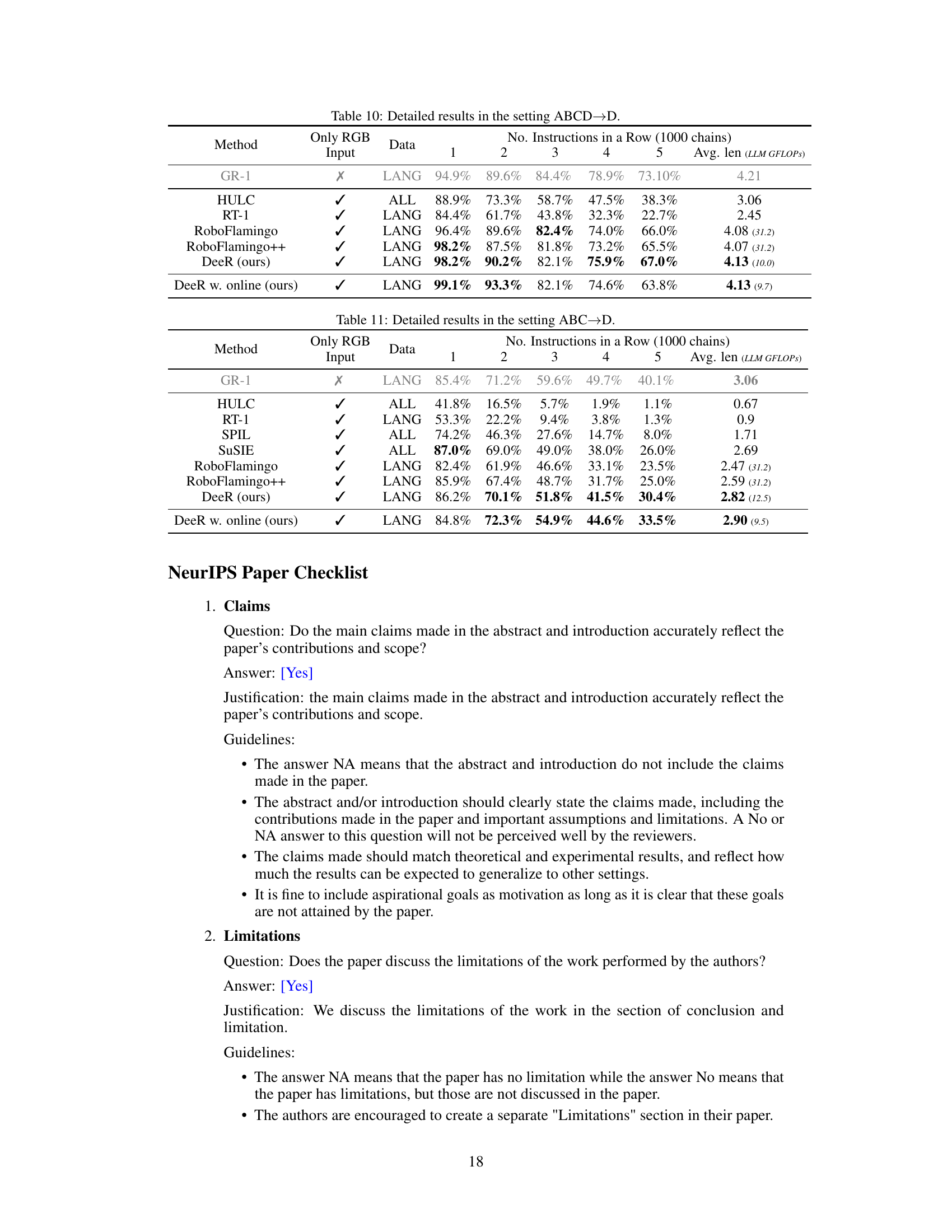

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the experimental results obtained for the ABCD→D setting in the CALVIN benchmark. It shows the average successful task length achieved by various methods, including the proposed DeeR model and several baselines, and the associated LLM GFLOPs. Each method’s performance is evaluated across five consecutive subtasks, and the results are reported as percentages representing the success rate for each subtask.

read the caption

Table 10: Detailed results in the setting ABCD→→\rightarrow→D.

| Method | Only RGB Input | Data | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Avg. len (LLM GFLOPs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HULC | ✓ | ALL | 82.7% | 64.9% | 50.4% | 38.5% | 28.3% | 2.64 | |

| SPIL | ✓ | ALL | 84.6% | 65.1% | 50.8% | 38.0% | 28.6% | 2.67 | |

| RoboFlamingo | ✓ | LANG | 83.9% | 64.3% | 42.9% | 35.7% | 19.6% | 2.46 (31.2) | |

| RoboFlamingo++ | ✓ | LANG | 87.1% | 69.6% | 49.6% | 37.1% | 27.2% | 2.71 (31.2) | |

| DeeR (ours) | ✓ | LANG | 85.3% | 69.6% | 54.9% | 42.0% | 31.2% | 2.83 (8.6) | |

| DeeR w. online (ours) | ✓ | LANG | 89.7% | 70.5% | 51.8% | 44.2% | 35.3% | 2.92 (8.5) |

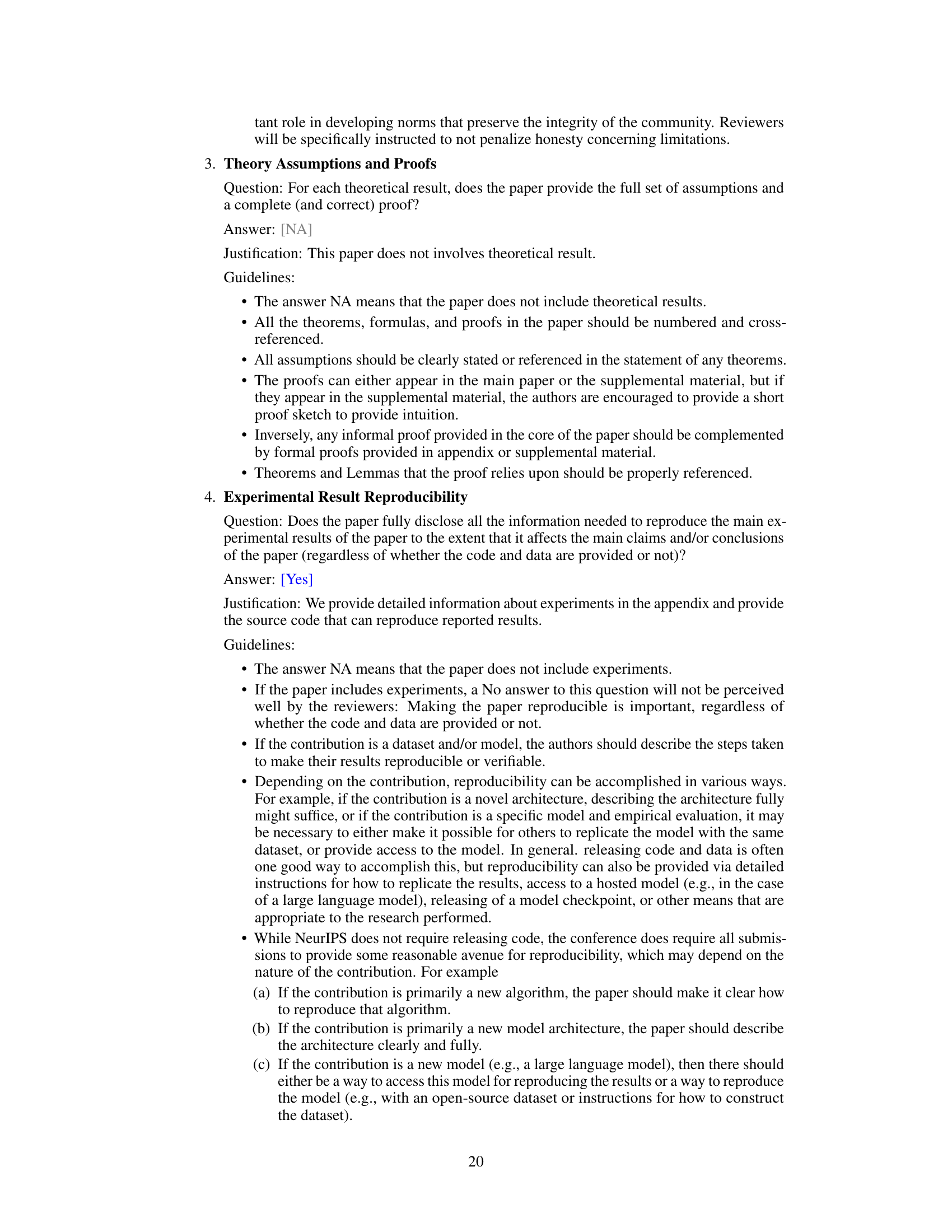

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the experimental results obtained using the ABC→D setting in the CALVIN benchmark. It compares different methods (HULC, SPIL, SuSIE, RoboFlamingo, RoboFlamingo++, DeeR, and DeeR w. online) across various metrics, including the average successful length of task chains and the number of consecutive successful instructions in each task chain (1 to 5). The input data used (RGB, LANG, ALL) are also specified for each method.

read the caption

Table 11: Detailed results in the setting ABC→→\rightarrow→D.

Full paper#