↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current methods for 3D garment reconstruction from images struggle with complex cloth deformations and limited dataset quality, hindering generalization. The lack of high-quality datasets with diverse garment styles, poses, and deformations poses significant challenges. This paper tackles these issues by introducing GarVerseLOD, a hierarchical dataset with levels of details that addresses the limitation of previous methods.

GarVerseLOD contains 6,000 high-quality garment models crafted by professionals and a novel data labeling paradigm is used for image generation. The proposed framework uses a coarse-to-fine reconstruction strategy and leverages the hierarchical structure of the dataset. The results demonstrate significant improvements in reconstruction quality and robustness compared to state-of-the-art methods, showcasing the effectiveness of the approach. This offers a powerful tool for various applications relying on accurate 3D garment models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical need for high-quality 3D garment datasets and robust reconstruction methods. The GarVerseLOD dataset, with its hierarchical structure and extensive paired image-3D model data, provides a significant advancement for researchers in computer vision and graphics. Its novel labeling paradigm and coarse-to-fine reconstruction framework offer new avenues of research, and its impressive results pave the way for improved applications in virtual fashion, e-commerce, and virtual reality.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 showcases the GarVerseLOD dataset and the hierarchical framework for 3D garment reconstruction. The framework leverages garment shape and deformation priors learned from the dataset to reconstruct high-fidelity 3D garment meshes from a single image. The figure demonstrates the system’s ability to handle various garment types and poses, producing realistic results that align well with the input images. Some images were sourced from licensed photos, while others were generated using Stable Diffusion. The gray background indicates synthetically generated images.

read the caption

Figure 1. We propose a hierarchical framework to recover different levels of garment details by leveraging the garment shape and deformation priors from the GarVerseLOD dataset. Given a single clothed human image, our approach is capable of generating high-fidelity 3D standalone garment meshes that exhibit realistic deformation and are well-aligned with the input image. Original images courtesy of licensed photos and Stable Diffusion (Rombach et al., 2022). The images with a gray background are synthesized, while the rest are licensed photos.

| Method | BCNet | ClothWild | Deep Fashion3D | ReEF | Ours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamfer Distance ↓ | 18.742 | 16.136 | 17.159 | 11.357 | 7.825 |

| Normal Consistency ↑ | 0.781 | 0.812 | 0.793 | 0.838 | 0.913 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against existing state-of-the-art techniques for 3D garment reconstruction. The metrics used for comparison include Chamfer Distance (measuring the geometric difference between the reconstructed and ground truth meshes), Normal Consistency (assessing the similarity of surface normals), and Intersection over Union (IoU, measuring the overlap of the predicted and ground truth garment regions). Lower Chamfer Distance and higher Normal Consistency values indicate better reconstruction accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1. Quantitive comparison between our method with others.

In-depth insights#

Garment 3D Modeling#

Garment 3D modeling presents significant challenges due to the complexity of fabric draping and deformation, influenced by both body pose and environmental factors. Traditional methods often struggle with realism and generalization. This research highlights the critical role of high-quality datasets, such as GarVerseLOD, in advancing the field. GarVerseLOD’s hierarchical structure, incorporating multiple levels of detail from coarse shapes to fine-grained geometry, allows for a staged approach to reconstruction. This is crucial for overcoming the inherent ill-posed nature of the problem, significantly improving accuracy and generalization. The study shows that incorporating both explicit and implicit representations offers a powerful approach, enhancing the model’s ability to capture both global garment shape and intricate local details simultaneously. The integration of a geometry-aware boundary prediction further boosts accuracy by addressing the challenges of boundary estimation from single images. The success of this approach demonstrates the potential of leveraging data with levels of detail and combining explicit and implicit methods for accurate and robust 3D garment modeling.

LOD Dataset#

A Levels of Detail (LOD) dataset for 3D garment reconstruction is a significant contribution because it addresses the limitations of existing datasets. The hierarchical nature of the LOD dataset, ranging from stylized shapes to highly detailed models, allows for a more tractable approach to the complex problem of 3D garment reconstruction. This staged approach facilitates training and inference, making the overall task less computationally intensive and easier to manage. The dataset’s inclusion of various levels of detail is key for training robust and generalizable models that can perform well across a range of clothing types, poses, and conditions. The inclusion of both synthetic and real-world images further enhances the robustness and applicability of the approach. The creation of a large-scale dataset with high-quality, hand-crafted garment meshes enhances the potential for significant improvements in the accuracy and realism of 3D garment reconstruction. This is a crucial step towards achieving more realistic virtual fashion and virtual try-on experiences.

Coarse-to-Fine#

A coarse-to-fine approach in 3D garment reconstruction is a powerful strategy that leverages a hierarchical representation of garment details. It starts with a simplified, coarse model, capturing the overall shape and pose, before progressively refining it by incorporating finer details and intricate deformations. This approach offers several advantages. Firstly, it simplifies a complex problem into manageable sub-problems. The coarse stage provides a robust initial estimate, reducing the search space for subsequent refinement steps. Secondly, it improves the efficiency of the reconstruction process by focusing computational resources on the most essential aspects initially. Finally, it enhances the generalization ability of the model to unseen data as the initial stage focuses on learning underlying garment properties that are less sensitive to variations in appearance, texture, and pose.

Boundary Prediction#

Accurate boundary prediction is crucial for high-fidelity 3D garment reconstruction, as it defines the garment’s shape and enables realistic rendering. The challenge lies in handling complex garment deformations and occlusions present in real-world images. Existing methods often rely solely on 2D image cues, which can lead to inaccurate predictions due to depth ambiguity. A promising approach involves integrating both 2D and 3D information; leveraging 2D image features for local detail and 3D geometry-aligned features to resolve depth inconsistencies and ensure global shape consistency. This fusion of cues is key to robust boundary prediction, especially for intricate garment shapes and poses. The use of implicit functions, such as neural implicit representations, could further enhance the accuracy by capturing the complex topology of garment boundaries. Investigating different architectural designs for combining 2D and 3D features, and exploring various loss functions for optimization will be critical to improving the accuracy of the prediction. Developing a robust and efficient algorithm for boundary prediction is a significant step toward achieving high-fidelity 3D garment modeling from single images.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this GarVerseLOD work could explore several promising avenues. Expanding the dataset’s scope to encompass a wider array of garment styles, materials, and body morphologies is crucial for improving generalization. Addressing the limitations in handling complex topologies, like multi-layered garments or those with slits, requires investigating advanced representation methods beyond implicit functions. Improving the efficiency of the reconstruction pipeline, particularly the boundary prediction, is also essential for real-time applications. Exploring the integration of physical simulation with the learned models could enhance realism and accuracy of garment deformations. Finally, investigating novel applications of the high-fidelity 3D garment models, such as virtual try-ons, personalized garment design, or advanced animation techniques, would showcase the dataset’s true potential.

More visual insights#

More on figures

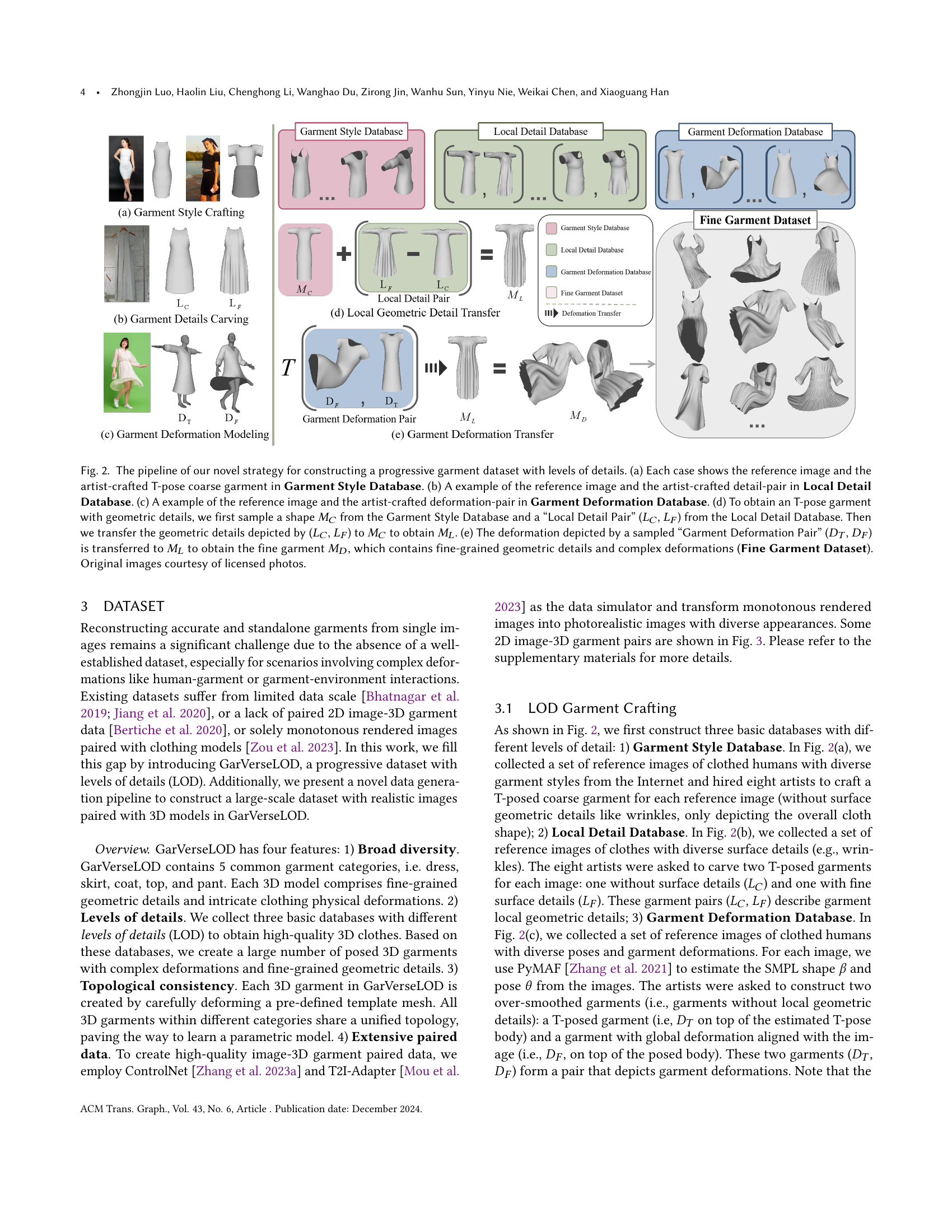

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of creating a hierarchical garment dataset with levels of detail. It starts with three basic databases: Garment Style Database (containing T-pose coarse garments), Local Detail Database (pairs of T-pose garments with and without fine details), and Garment Deformation Database (pairs of T-pose and deformed garments). These databases are combined to create the Fine Garment Dataset, which contains garments with both fine details and complex deformations. The process involves sampling shapes and deformations from the basic databases and transferring them to generate progressively more detailed garment models.

read the caption

Figure 2. The pipeline of our novel strategy for constructing a progressive garment dataset with levels of details. (a) Each case shows the reference image and the artist-crafted T-pose coarse garment in Garment Style Database. (b) A example of the reference image and the artist-crafted detail-pair in Local Detail Database. (c) A example of the reference image and the artist-crafted deformation-pair in Garment Deformation Database. (d) To obtain an T-pose garment with geometric details, we first sample a shape MCsubscript𝑀𝐶M_{C}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_C end_POSTSUBSCRIPT from the Garment Style Database and a “Local Detail Pair” (LCsubscript𝐿𝐶L_{C}italic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_C end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, LFsubscript𝐿𝐹L_{F}italic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_F end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) from the Local Detail Database. Then we transfer the geometric details depicted by (LCsubscript𝐿𝐶L_{C}italic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_C end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, LFsubscript𝐿𝐹L_{F}italic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_F end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) to MCsubscript𝑀𝐶M_{C}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_C end_POSTSUBSCRIPT to obtain MLsubscript𝑀𝐿M_{L}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_L end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. (e) The deformation depicted by a sampled “Garment Deformation Pair” (DTsubscript𝐷𝑇D_{T}italic_D start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_T end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, DFsubscript𝐷𝐹D_{F}italic_D start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_F end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) is transferred to MLsubscript𝑀𝐿M_{L}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_L end_POSTSUBSCRIPT to obtain the fine garment MDsubscript𝑀𝐷M_{D}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_D end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, which contains fine-grained geometric details and complex deformations (Fine Garment Dataset). Original images courtesy of licensed photos.

🔼 Figure 3 illustrates the process of generating photorealistic images of garments for training the model. The left side shows the pipeline: starting with textureless 3D garment renderings from various viewpoints, these are fed into Canny-Conditional Stable Diffusion to create photorealistic images with diverse appearances. The right side displays example results. (a) shows a garment from the Fine Garment Dataset, (b) is the generated photorealistic image, (c) its corresponding pixel-aligned mask, (d) the normal map rendered from the 3D garment, (e) the garment mask from the 3D model, and (f) the corresponding T-pose coarse garment. Section 4 of the paper details how these images are used for training different parts of the model: (b, f) trains the coarse garment estimator; (b, c, d) trains the normal estimator; and (d, e, a) trains the fine garment estimator and geometry-aware boundary predictor. All synthesized images were produced using Stable Diffusion.

read the caption

Figure 3. Left: Our novel strategy for generating extensive photorealistic paired images. We acquire rendered images of 3D garments with random camera views. These rendered images are processed through Canny-Conditional Stable Diffusion (Rombach et al., 2022; Mou et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023a) to produce photorealistic images. Right: (a) The garment sampled from Fine Garment Dataset; (b) The synthesized image; (c) The pixel-aligned mask; (d) The normal map rendered using (a); (e) The garment mask rendered by (a); (f) The counterpart T-pose coarse garment of (a). In Sec. 4, (b, f) is used to train the coarse garment estimator, while (b,c,d) is adopted to train the normal estimator. (d, e, a) is utilized to train the fine garment estimator and the geometry-aware boundary predictor. Synthesized images courtesy of Stable Diffusion.

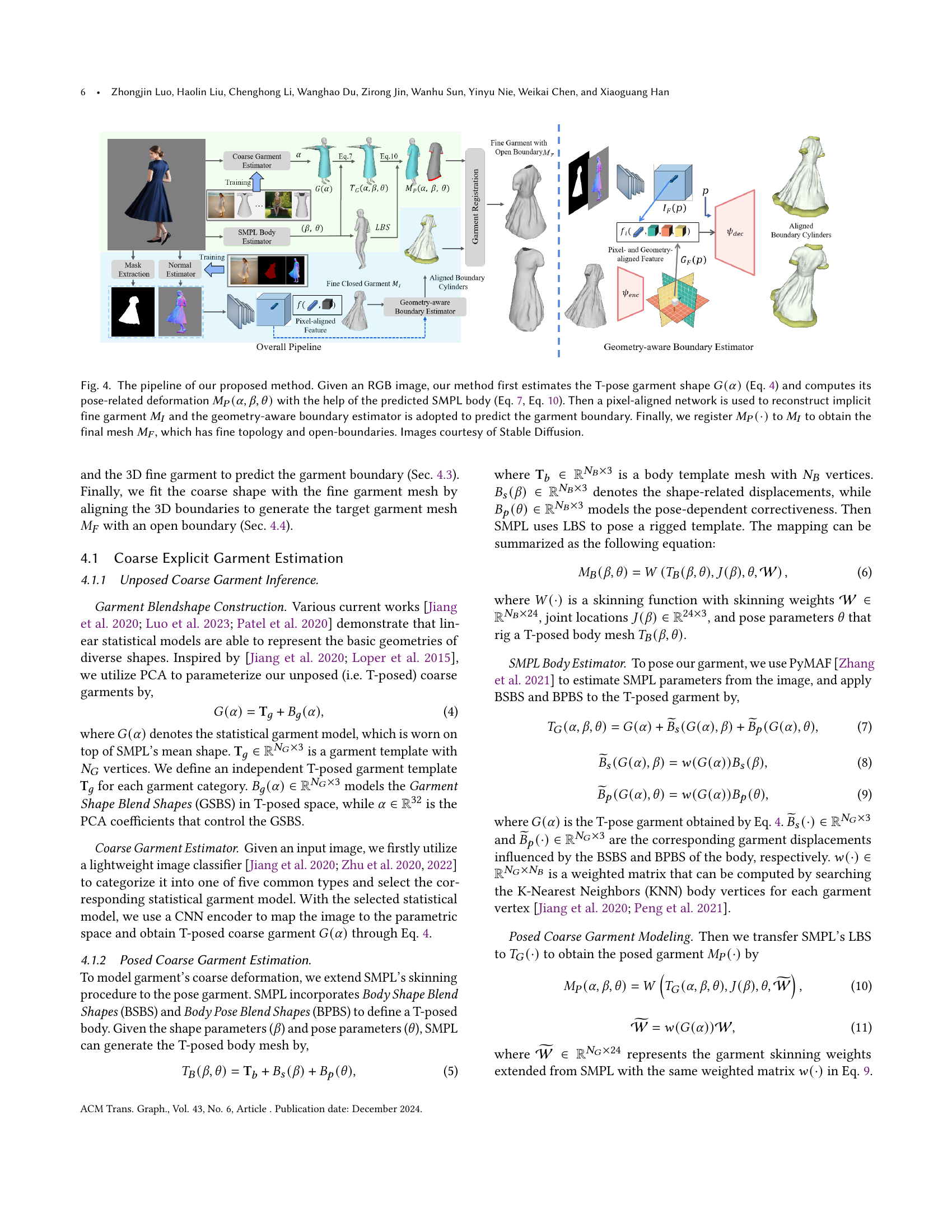

🔼 This figure illustrates the pipeline of the proposed 3D garment reconstruction method. Starting with an RGB image as input, the method first estimates the coarse T-pose garment shape using equation 4. This shape is then refined by incorporating pose-related deformations calculated using equations 7 and 10, which leverage a predicted SMPL body model. Next, a pixel-aligned network reconstructs an implicit fine garment representation, and a geometry-aware boundary estimator predicts the garment’s boundary. Finally, the coarse and fine garment representations are registered to produce a final garment mesh with accurate topology and open boundaries. The images shown in the figure were generated using Stable Diffusion.

read the caption

Figure 4. The pipeline of our proposed method. Given an RGB image, our method first estimates the T-pose garment shape G(α)𝐺𝛼G({{\alpha}})italic_G ( italic_α ) (Eq. 4) and computes its pose-related deformation MP(α,β,θ)subscript𝑀𝑃𝛼𝛽𝜃M_{P}(\alpha,\beta,\theta)italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_P end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( italic_α , italic_β , italic_θ ) with the help of the predicted SMPL body (Eq. 7, Eq. 10). Then a pixel-aligned network is used to reconstruct implicit fine garment MIsubscript𝑀𝐼M_{I}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_I end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and the geometry-aware boundary estimator is adopted to predict the garment boundary. Finally, we register MP(⋅)subscript𝑀𝑃⋅M_{P}(\cdot)italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_P end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ( ⋅ ) to MIsubscript𝑀𝐼M_{I}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_I end_POSTSUBSCRIPT to obtain the final mesh MFsubscript𝑀𝐹M_{F}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_F end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, which has fine topology and open-boundaries. Images courtesy of Stable Diffusion.

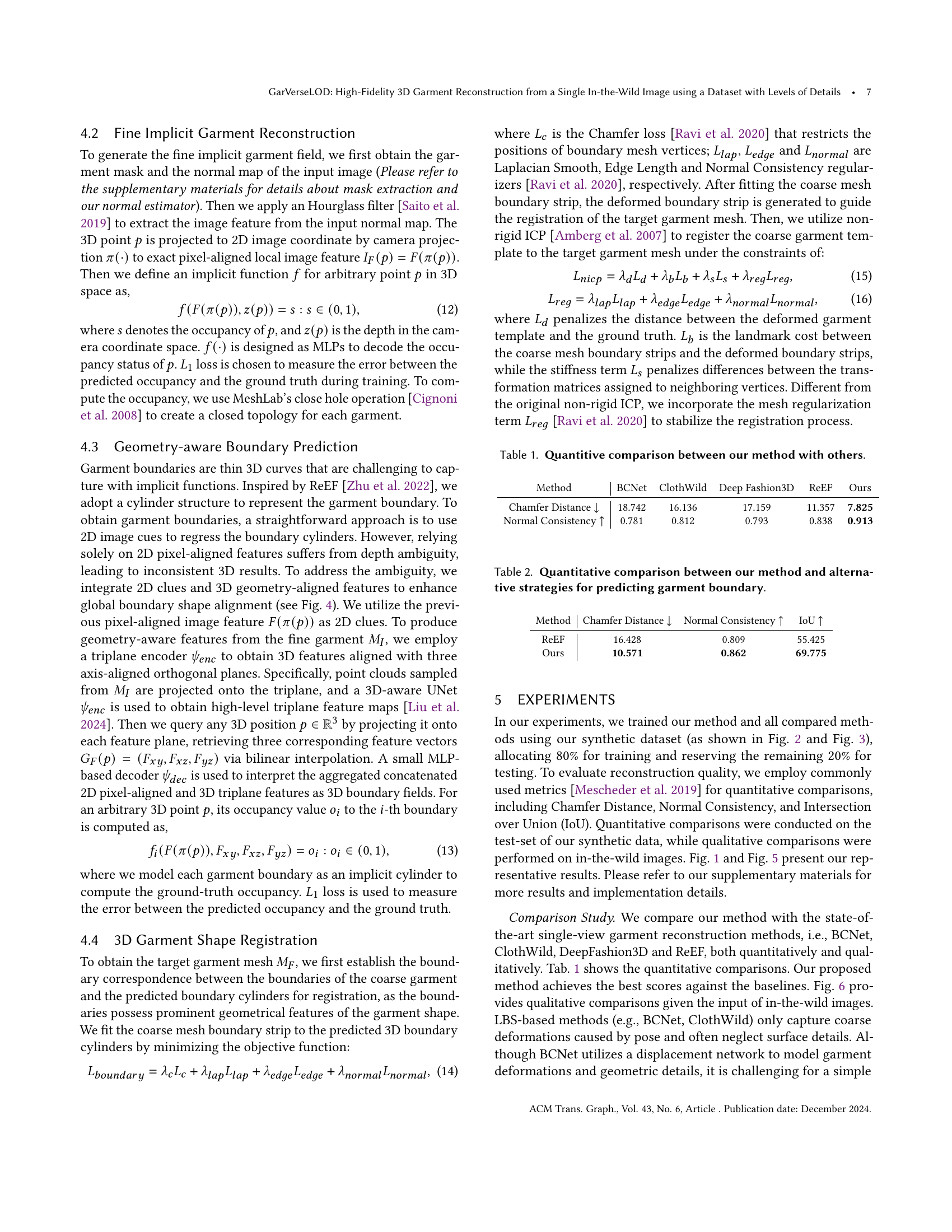

🔼 This figure showcases the results of the proposed 3D garment reconstruction method. It presents pairs of input images and their corresponding reconstructed 3D garment meshes. The examples demonstrate the method’s capability to accurately reconstruct garments with complex shapes and detailed features, even in the presence of significant deformations. A key improvement is the inclusion of realistic collars, achieved by creating a separate database of various collar types and training a classification network to select the most appropriate collar for each garment based on the input image. This addresses a significant challenge in realistic garment reconstruction by incorporating nuanced details often missing in previous methods. The source of the input images is specified; those with gray backgrounds are synthetically generated, while the rest are from licensed photo sources.

read the caption

Figure 5. Result gallery of our method. Each image is followed by the reconstructed garment mesh. As illustrated, our method can effectively reconstruct garments with intricate deformations and fine-grained surface details. To support the modeling of folded structures, such as collars, we assembled a repository of diverse real-world collars that were crafted based on our topologically-consistent garments. A lightweight classification network was trained to select the collar that best matches the given image in terms of appearance (Zhu et al., 2022). Original images courtesy of licensed photos and Stable Diffusion. The images with a gray background are synthesized, while the rest are licensed photos.

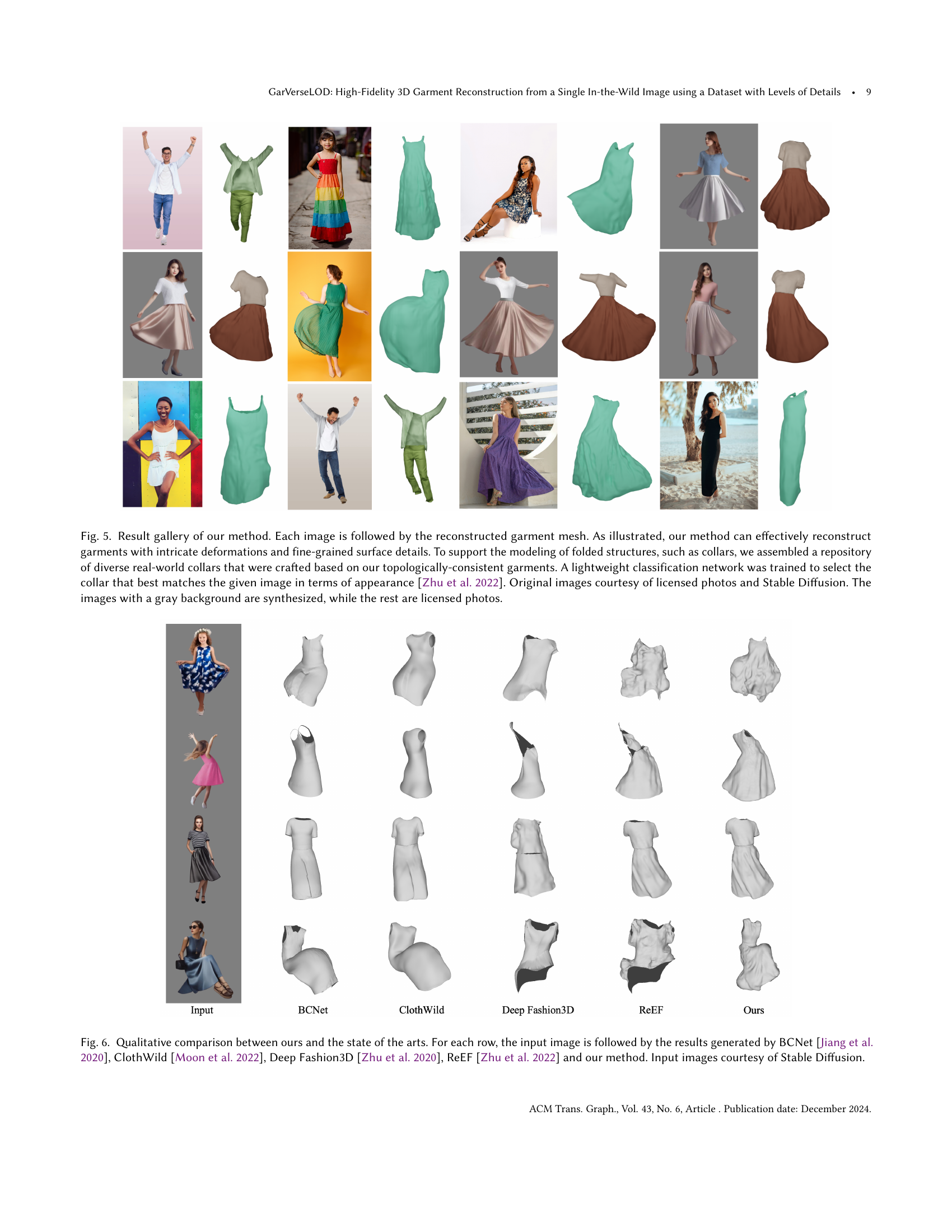

🔼 Figure 6 presents a qualitative comparison of five different methods for 3D garment reconstruction from a single image: BCNet, ClothWild, DeepFashion3D, ReEF, and the authors’ proposed method. Each row shows an input image followed by the results generated by each of the five methods. This allows for a visual comparison of the accuracy, detail, and overall quality of the garment reconstructions produced by each approach. The input images were all generated using Stable Diffusion.

read the caption

Figure 6. Qualitative comparison between ours and the state of the arts. For each row, the input image is followed by the results generated by BCNet (Jiang et al., 2020), ClothWild (Moon et al., 2022), Deep Fashion3D (Zhu et al., 2020), ReEF (Zhu et al., 2022) and our method. Input images courtesy of Stable Diffusion.

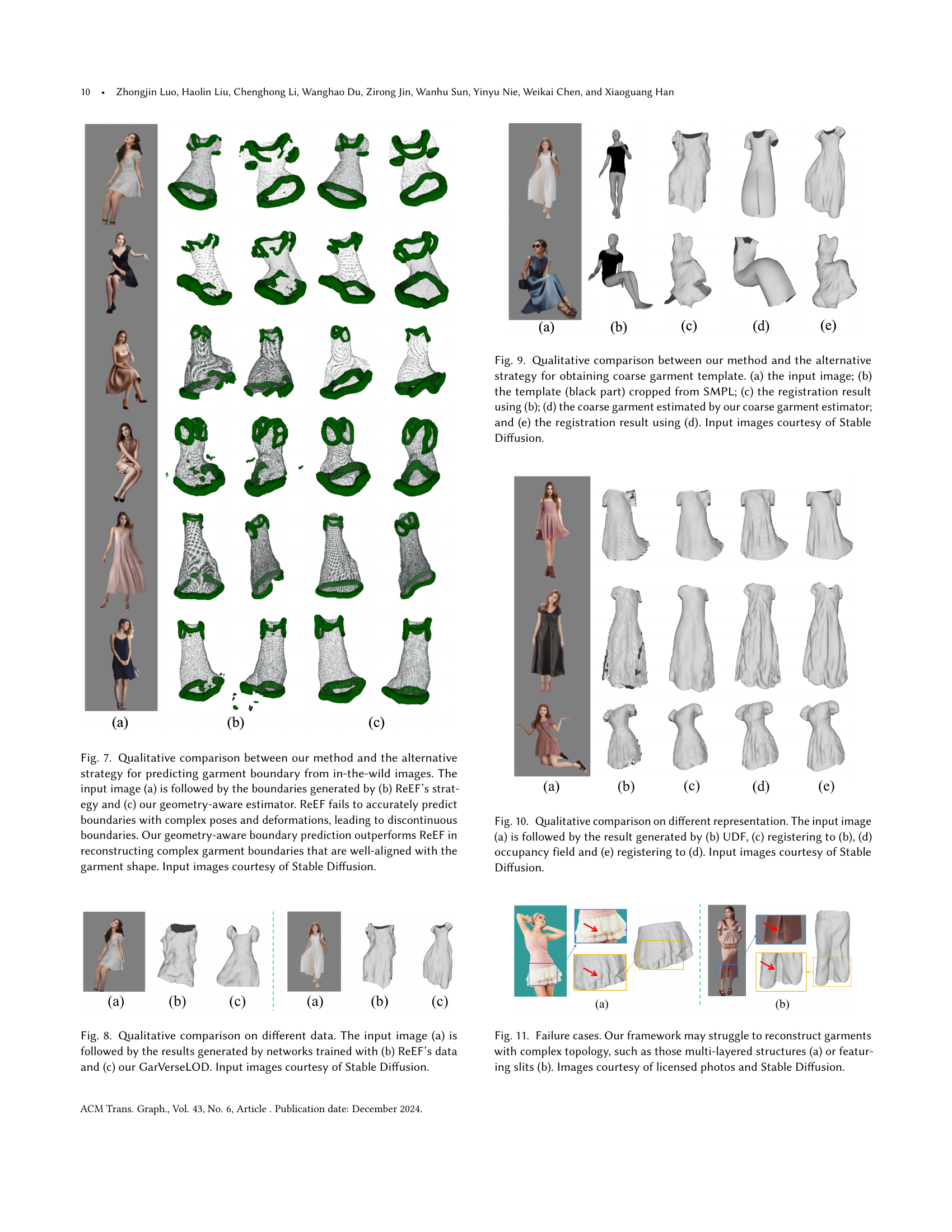

🔼 Figure 7 presents a qualitative comparison of garment boundary prediction methods using real-world images. The figure showcases three columns: (a) the input image, (b) the boundary prediction from the ReEF method, and (c) the boundary prediction from the proposed geometry-aware method. The comparison highlights the superior performance of the proposed method, which accurately reconstructs complex and deformed garment boundaries that closely align with the garment’s shape, unlike ReEF’s prediction which suffers from inaccuracies and discontinuities, especially in complex poses.

read the caption

Figure 7. Qualitative comparison between our method and the alternative strategy for predicting garment boundary from in-the-wild images. The input image (a) is followed by the boundaries generated by (b) ReEF’s strategy and (c) our geometry-aware estimator. ReEF fails to accurately predict boundaries with complex poses and deformations, leading to discontinuous boundaries. Our geometry-aware boundary prediction outperforms ReEF in reconstructing complex garment boundaries that are well-aligned with the garment shape. Input images courtesy of Stable Diffusion.

🔼 This figure compares the results of 3D garment reconstruction using two different datasets: ReEF and GarVerseLOD. The same input image is used for both models. Column (a) shows the input image. Column (b) presents the reconstruction result obtained by training a model on the ReEF dataset. Column (c) displays the reconstruction result obtained by training a model on the GarVerseLOD dataset. The comparison highlights the impact of different datasets on the accuracy and quality of the garment reconstruction, demonstrating the superior performance of GarVerseLOD. The images are generated using Stable Diffusion.

read the caption

Figure 8. Qualitative comparison on different data. The input image (a) is followed by the results generated by networks trained with (b) ReEF’s data and (c) our GarVerseLOD. Input images courtesy of Stable Diffusion.

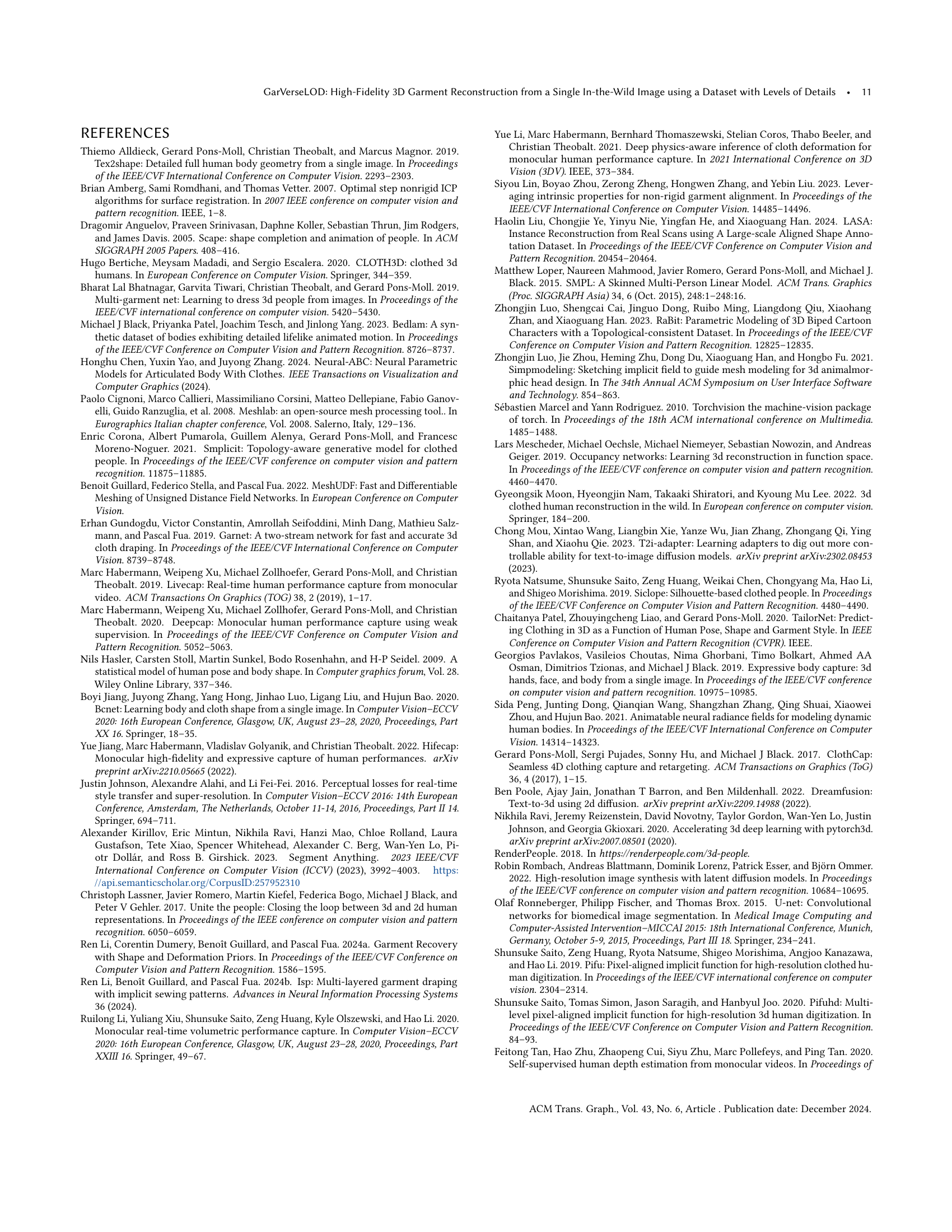

🔼 Figure 9 compares different approaches for obtaining a coarse garment template, a crucial step in 3D garment reconstruction. It shows the results of two methods: (a) Input image: The image serves as the input to the garment reconstruction process. (b) SMPL-cropped template: A template (the black part) is created by directly cropping a section from an SMPL (Skinned Multi-Person Linear Model) body mesh. This method represents a simplified approach where garment information is borrowed from a general human body model. (c) Registration result using (b): The template from (b) is registered (or aligned) to the input image, producing a coarse garment estimate. (d) Coarse garment estimated by our method: The proposed method estimates a coarse garment template. This method learns garment characteristics directly from data rather than relying on a human body model. (e) Registration result using (d): The template produced by our method is registered to the input image, yielding a coarse garment estimate. The figure demonstrates that using a learned garment estimator (our method) leads to superior registration results compared to simply cropping from a human body model.

read the caption

Figure 9. Qualitative comparison between our method and the alternative strategy for obtaining coarse garment template. (a) the input image; (b) the template (black part) cropped from SMPL; (c) the registration result using (b); (d) the coarse garment estimated by our coarse garment estimator; and (e) the registration result using (d). Input images courtesy of Stable Diffusion.

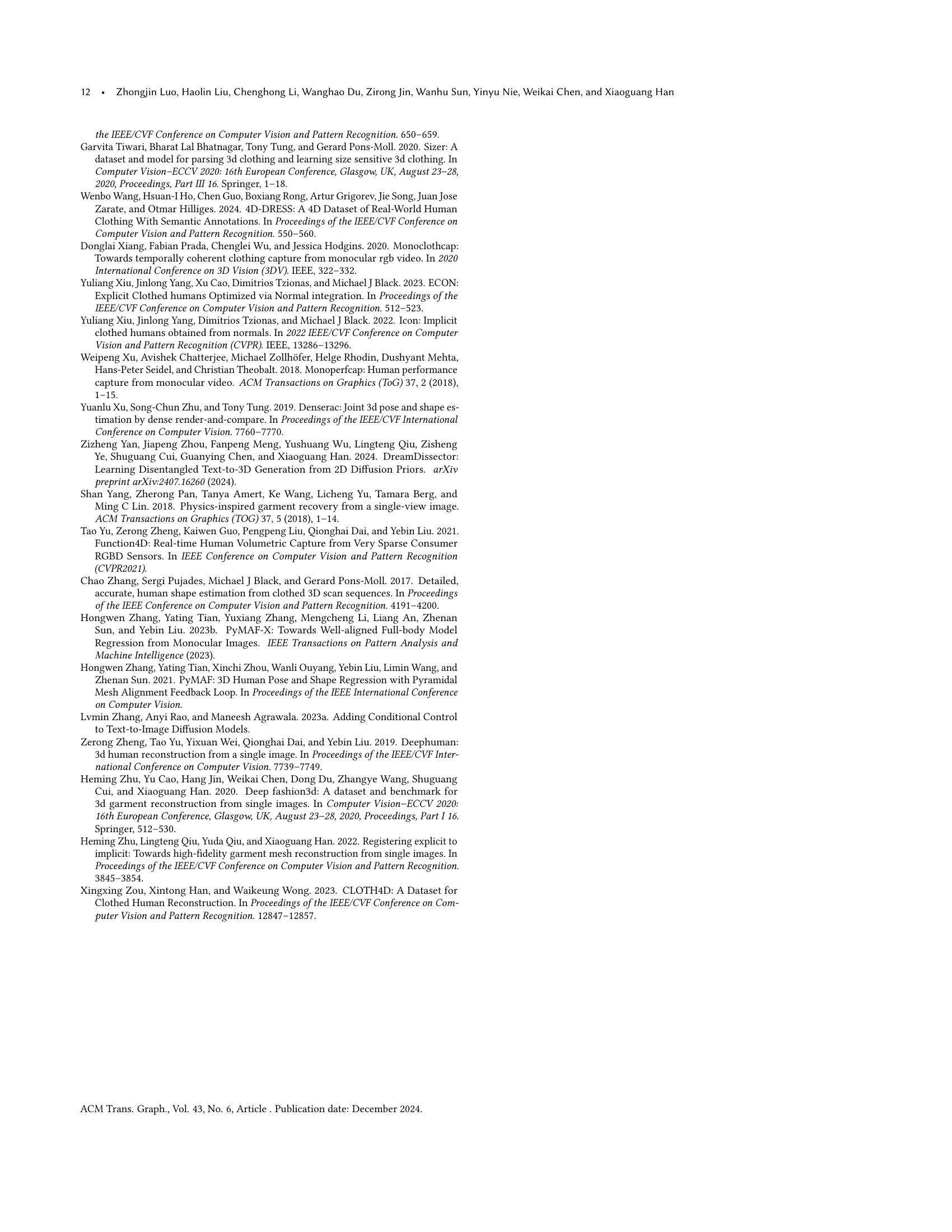

🔼 This figure compares the results of using different 3D representations for garment reconstruction: Unsigned Distance Fields (UDF) and occupancy fields. The input image (a) is shown alongside reconstruction attempts using (b) UDF alone, (c) UDF followed by registration to refine the result, (d) an occupancy field, and (e) the occupancy field with subsequent registration. The comparison highlights the effectiveness of the occupancy field approach, especially when combined with registration for accurate garment reconstruction. Images were synthesized using Stable Diffusion.

read the caption

Figure 10. Qualitative comparison on different representation. The input image (a) is followed by the result generated by (b) UDF, (c) registering to (b), (d) occupancy field and (e) registering to (d). Input images courtesy of Stable Diffusion.

🔼 Figure 11 showcases instances where the proposed garment reconstruction method encounters difficulties. Panel (a) illustrates a limitation in handling garments with complex, multi-layered structures, such as layered skirts or dresses. The model struggles to accurately capture the individual layers and their interactions. Panel (b) demonstrates challenges in reconstructing garments with slits or openings. These features present significant topological complexities that the current approach has difficulty resolving. Both examples highlight scenarios where the model’s capacity to handle complex garment geometry and topology is limited.

read the caption

Figure 11. Failure cases. Our framework may struggle to reconstruct garments with complex topology, such as those multi-layered structures (a) or featuring slits (b). Images courtesy of licensed photos and Stable Diffusion.

🔼 This figure shows the five predefined garment templates used as the base for creating the 3D garment models in the GarVerseLOD dataset. Each template represents a basic, T-pose garment shape for a different clothing category: (a) dress, (b) skirt, (c) top, (d) pants, and (e) coat. These templates serve as a starting point for the artists who then manually add detailed geometry and realistic deformations to create the diverse garment models in the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 12. Predefined templates for each garment category, including (a) dress, (b) skirt, (c) top, (d) pant, and (e) coat.

🔼 The figure illustrates the process of creating high-fidelity 3D garment models. It starts with a real image of a person wearing clothes. PyMAF is used to estimate the underlying 3D human body pose (SMPL). Eight artists then manually adjust a template garment mesh to match the T-pose of this estimated body, creating the ‘T-pose Garment’. Next, SMPL’s Linear Blend Skinning (LBS) is applied to this ‘T-pose Garment’ to generate a ‘Posed Garment’ which reflects the basic pose-related deformations. Finally, the artists further refine the ‘Posed Garment’, resulting in the ‘Crafted Garment’, which incorporates more complex deformations that would not be solely caused by pose, such as those resulting from environmental influences or other factors affecting the fabric. This multi-step process ensures that the final ‘Crafted Garment’ models accurately reflect the realistic drape and texture of the clothing.

read the caption

Figure 13. Given a “Collected Image”, we utilize PyMAF (Zhang et al., 2021, 2023b) to estimate SMPL body. Eight artists are then tasked with creating “T-pose Garment” shapes by deforming a predefined “Template” to match the T-pose body predicted by PyMAF. Then the SMPL’s Linear Blend Skinning (LBS) is extended to the T-pose garment to obtain the “Posed Garment”. Finally, the artists are further instructed to refine the posed garment to get the “Crafted Garment” while ensuring that garment deformations closely match the collected images. “Posed Garment” represent the shape of clothing influenced by human pose, while “Crafted Garment” capture the state of garments affected by various complex factors—not only pose but also other environmental influences, such as garment-environment interactions and external forces like wind.

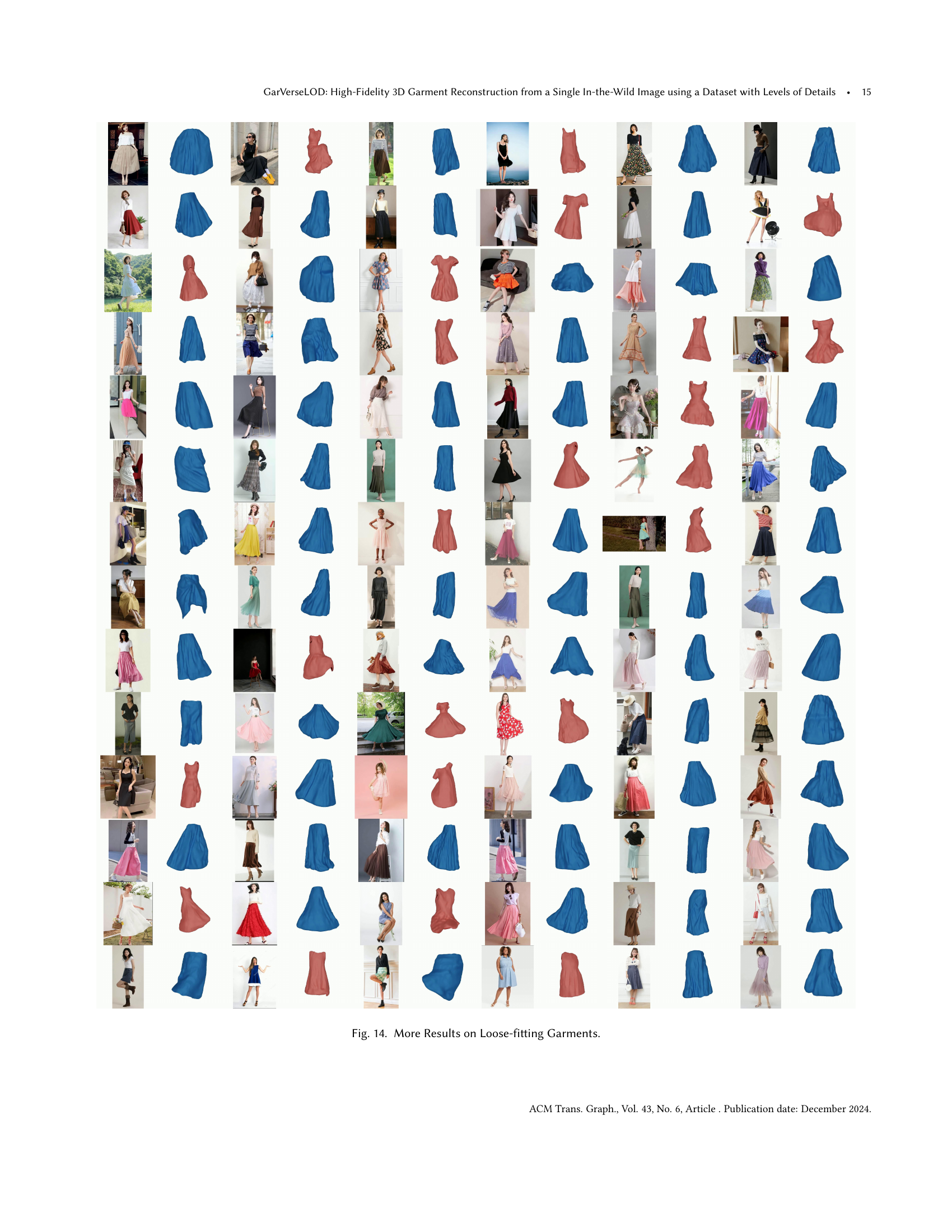

🔼 This figure showcases the results of the proposed method on various loose-fitting garments. It visually demonstrates the ability of the model to handle complex cloth deformations and generate high-fidelity 3D garment reconstructions from single, in-the-wild images. Each image is paired with its corresponding generated 3D model, highlighting the accuracy and detail of the reconstructions.

read the caption

Figure 14. More Results on Loose-fitting Garments.

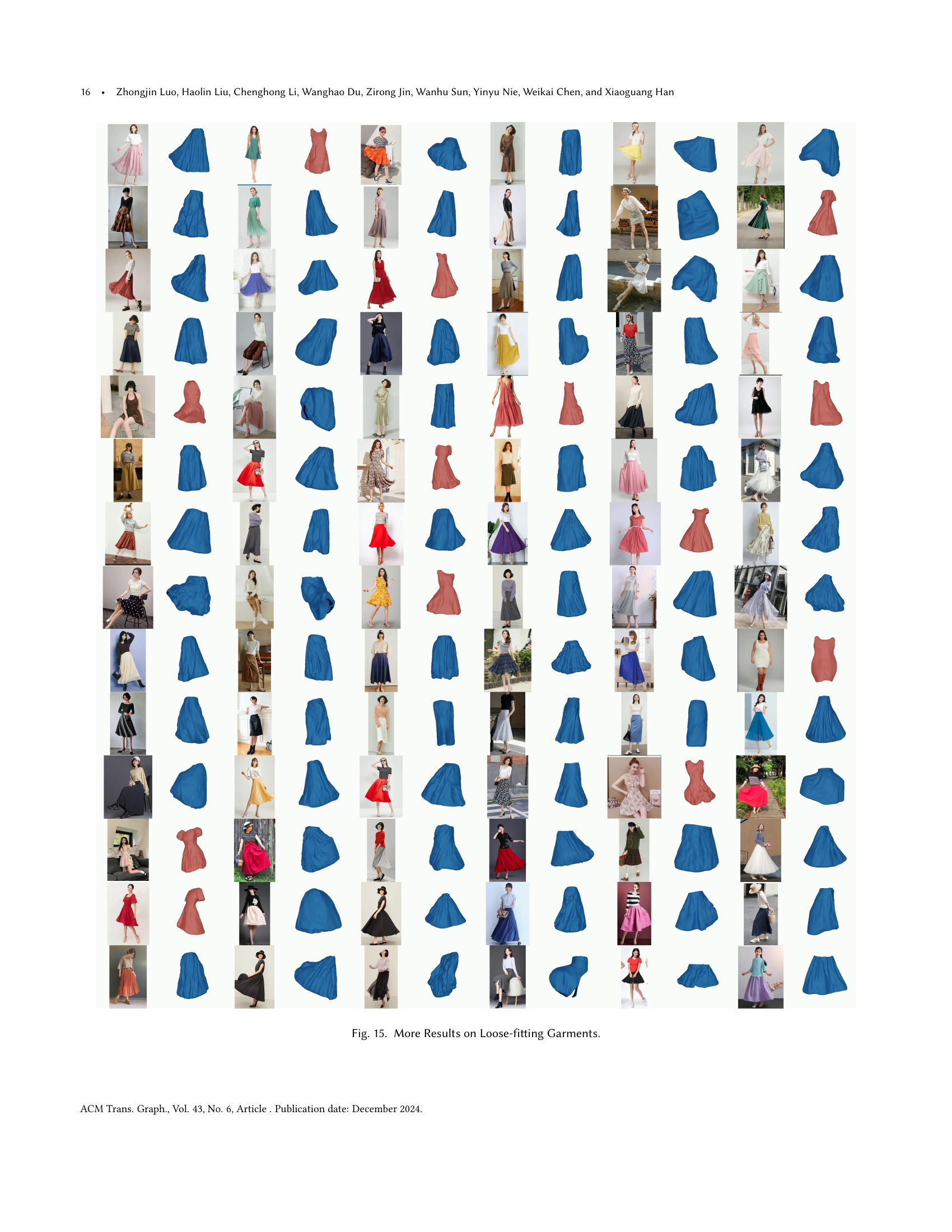

🔼 This figure shows additional results of the proposed method applied to loose-fitting garments. It showcases the model’s ability to reconstruct a variety of loose garments with different styles and poses, highlighting its generalization capabilities and robustness to various levels of garment deformation.

read the caption

Figure 15. More Results on Loose-fitting Garments.

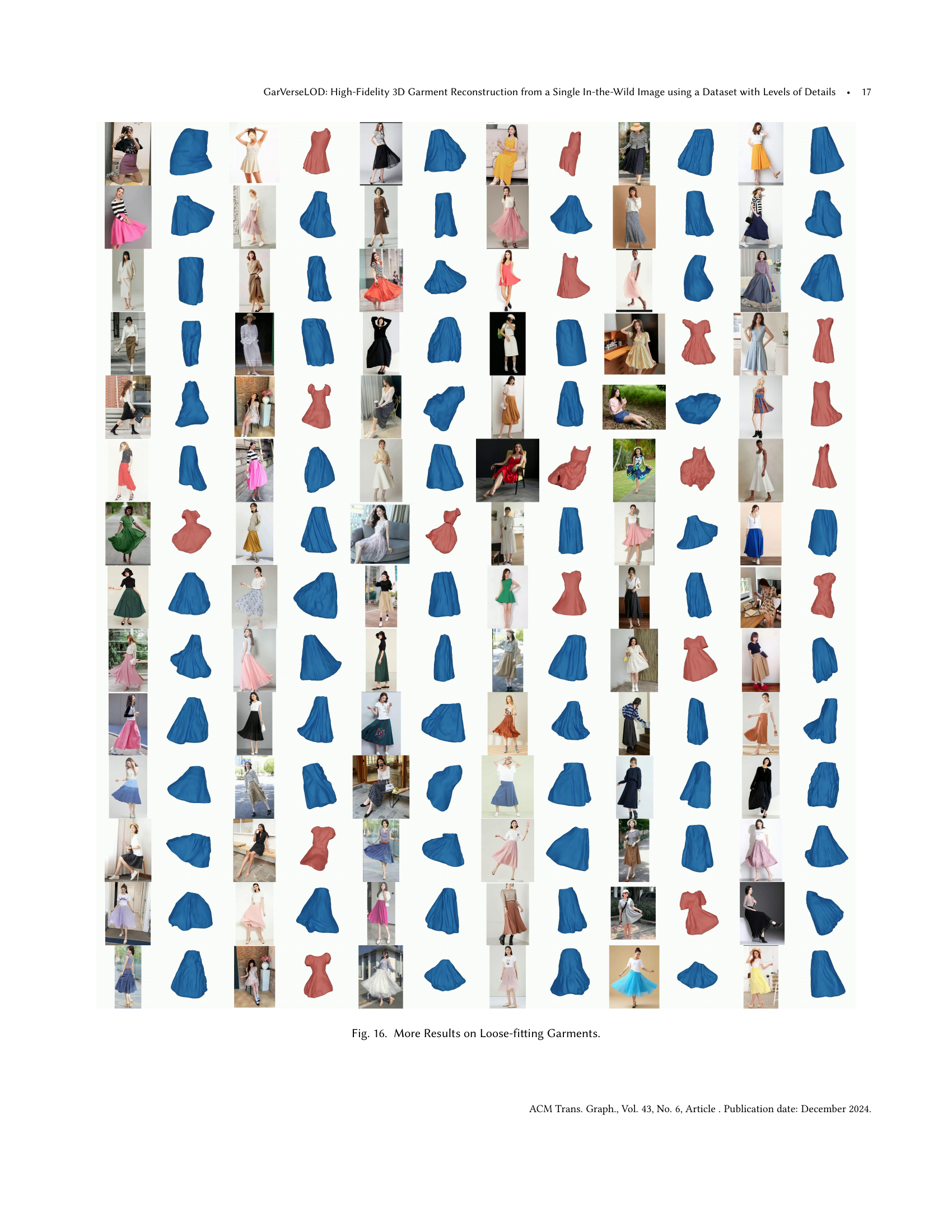

🔼 This figure showcases additional results of 3D garment reconstruction from single images. It demonstrates the method’s ability to handle loose-fitting garments, a challenging scenario due to the increased complexity of garment deformations and the lack of strong visual cues. The images show a variety of loose-fitting garments (dresses, skirts, etc.) and their corresponding reconstructed 3D models. The success in reconstructing the shapes and textures of these loose garments highlights the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed method.

read the caption

Figure 16. More Results on Loose-fitting Garments.

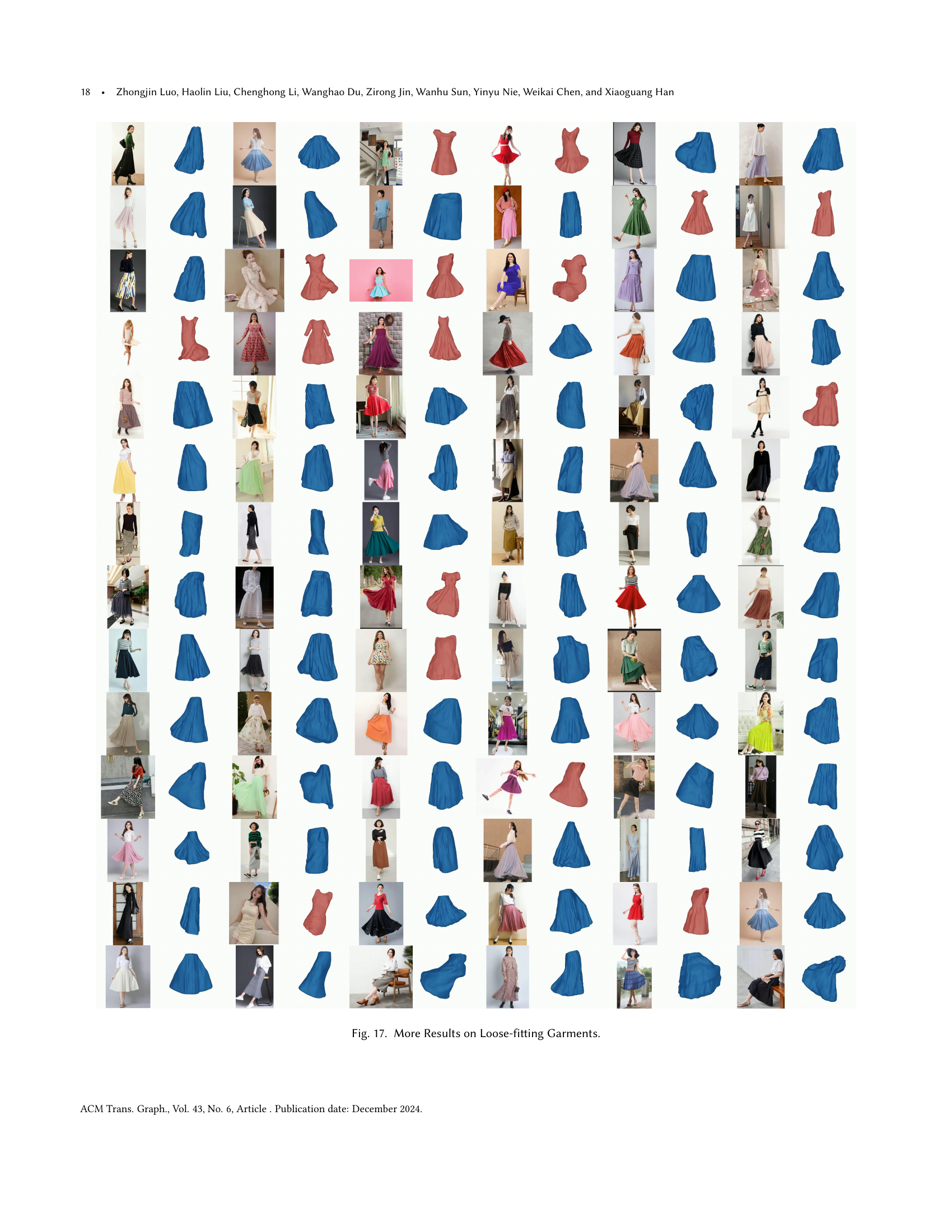

🔼 This figure showcases additional results of the proposed method on loose-fitting garments. It demonstrates the method’s ability to reconstruct various loose-fitting garments with different shapes, poses, and textures, highlighting its generalization capability and robustness in handling various complex garment deformations. Each image shows an input image followed by its corresponding 3D reconstruction.

read the caption

Figure 17. More Results on Loose-fitting Garments.

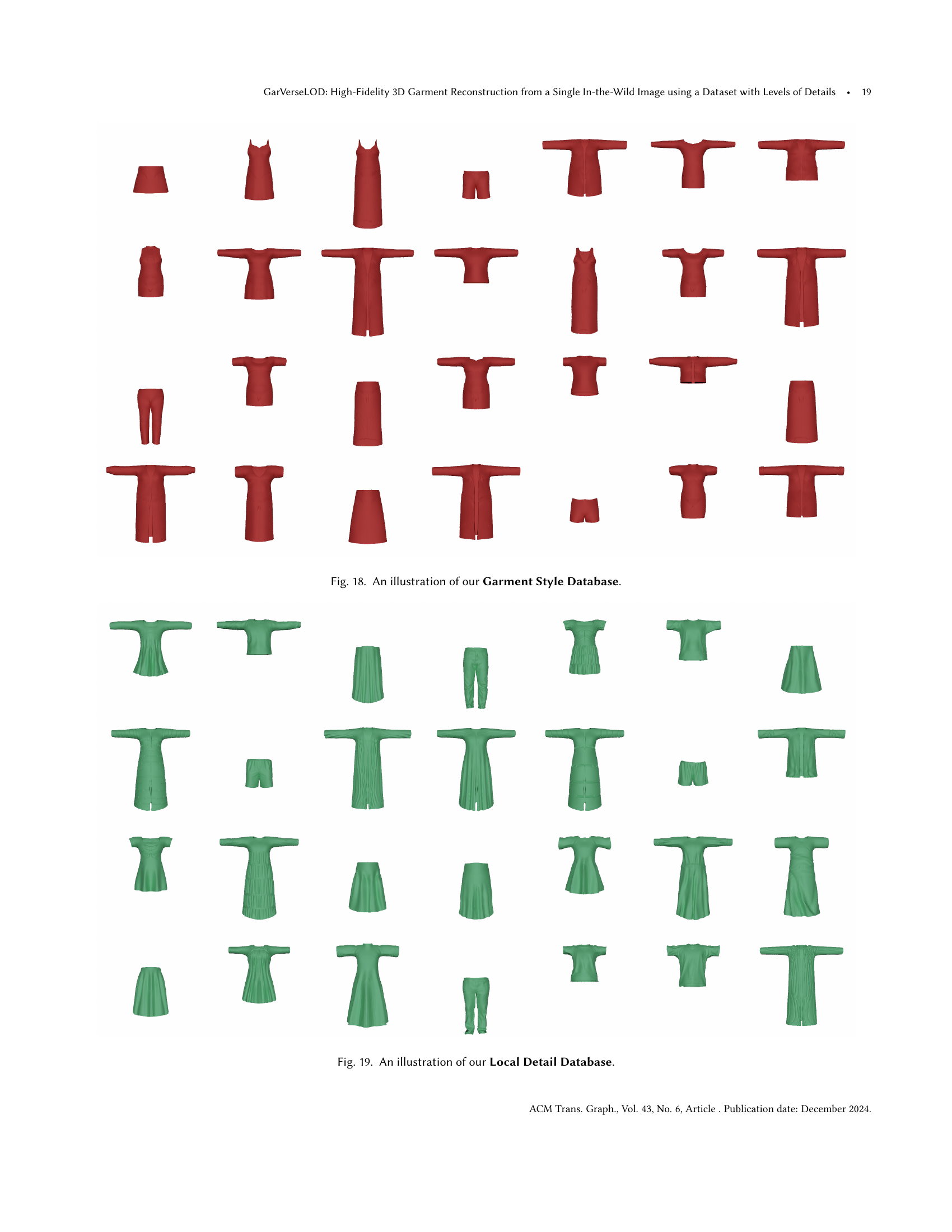

🔼 This figure shows a collection of simplified garment models from the Garment Style Database. Each model represents a basic garment shape (dress, skirt, coat, top, or pants) in a T-pose, lacking detailed textures or intricate folds. These simplified models serve as foundational templates for generating more complex garments by adding local details and deformations in later stages of the dataset creation process.

read the caption

Figure 18. An illustration of our Garment Style Database.

🔼 Figure 19 shows a subset of the Local Detail Database from the GarVerseLOD dataset. This database contains pairs of T-posed garment models, one with and one without fine-grained geometric details such as wrinkles. These pairs are used to learn how to transfer realistic local detail from a detailed model onto a simpler, more basic model. The images illustrate the variety of clothing items and detail levels captured in this part of the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 19. An illustration of our Local Detail Database.

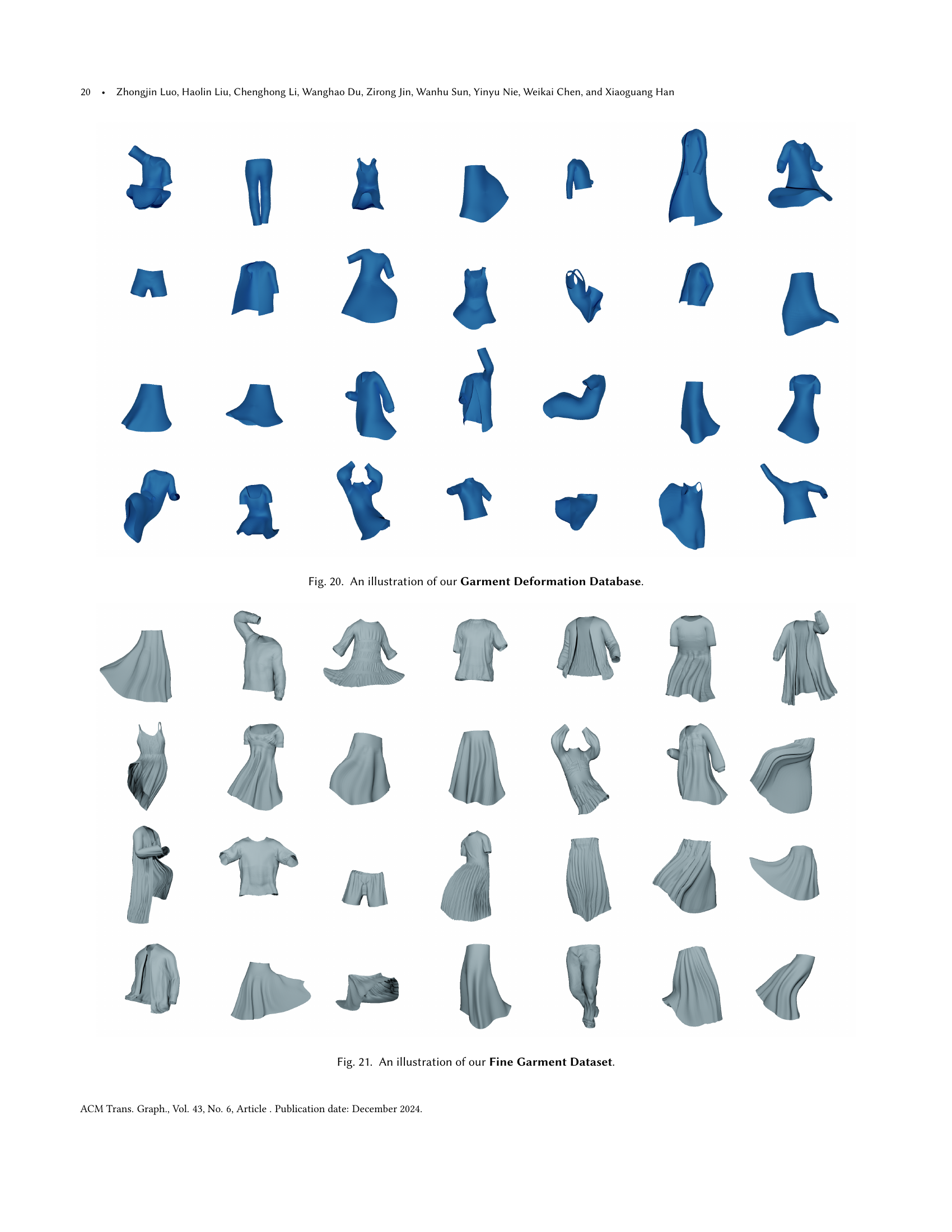

🔼 Figure 20 visually showcases the Garment Deformation Database, a key component of the GarVerseLOD dataset. This database contains pairs of T-posed and deformed garment meshes. The T-posed mesh represents the garment in a neutral pose, while the deformed mesh showcases the garment’s appearance after undergoing various deformations. These deformations result from a combination of factors like body pose, interactions with the environment, and self-collisions. The paired data within this database are crucial for training the model to learn how different factors influence the garment’s shape and overall appearance.

read the caption

Figure 20. An illustration of our Garment Deformation Database.

🔼 Figure 21 visually showcases the ‘Fine Garment Dataset,’ a crucial component of the GarVerseLOD dataset. Unlike the other datasets (Garment Style, Local Detail, and Garment Deformation), this dataset integrates the details from all three, resulting in high-fidelity 3D garment models that capture both global deformations (like those caused by pose) and fine-grained local details (like wrinkles and creases). Each garment model in the dataset presents a complex, realistic representation of clothing.

read the caption

Figure 21. An illustration of our Fine Garment Dataset.

More on tables

| Method | Chamfer Distance ↓ | Normal Consistency ↑ | IoU ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReEF | 16.428 | 0.809 | 55.425 |

| Ours | 10.571 | 0.862 | 69.775 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the garment boundary prediction performance between the proposed method and alternative methods. The comparison uses the Chamfer Distance (lower is better), Normal Consistency (higher is better), and Intersection over Union (IoU) (higher is better) metrics to evaluate the accuracy and quality of the predicted garment boundaries. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in accurately predicting garment boundaries compared to existing approaches.

read the caption

Table 2. Quantitative comparison between our method and alternative strategies for predicting garment boundary.

| Method | Ablation Study on | Ours | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Coarse Garment Estimation | Implicit Representation | |||||

| UDF w/o Registering | UDF w/ Registering | Occupancy w/o Registering | |||||

| ReEF’s dataset | Crop from SMPL | ||||||

| Chamfer Distance ↓ | 16.363 | 14.635 | 9.616 | 9.375 | 8.658 | 7.825 | |

| Normal Consistency ↑ | 0.805 | 0.823 | 0.841 | 0.848 | 0.851 | 0.913 |

🔼 Table 3 presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against alternative approaches for 3D garment reconstruction. Specifically, it compares the performance using metrics such as Chamfer Distance, Normal Consistency, and Intersection over Union (IoU). The comparison is done using different datasets and strategies to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

read the caption

Table 3. Quantitative comparison between our method and alternative strategies.

| Category | Dress | Coat | Skirt | Top | Pant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garment Style Database | 863 | 760 | 538 | 350 | 358 |

| Local Detail Database | 86 | 62 | 55 | 38 | 36 |

| Garment Deformation Database | 622 | 605 | 456 | 582 | 589 |

| Total | 1,571 | 1,427 | 1,049 | 970 | 983 |

🔼 Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of the GarVerseLOD dataset, categorized into three basic databases: Garment Style Database, Local Detail Database, and Garment Deformation Database. For each database, it shows the number of garments created by artists for each of the five garment categories (dress, skirt, coat, top, and pant). The ‘Total’ row gives the combined count for each database across all categories. The caption clarifies that the ‘Total’ numbers represent the total number of garments manually created by artists, not the total number of garments that can be generated using the dataset’s synthesis capabilities.

read the caption

Table 4. Data statistics for each basic database. The total size refers to the number of garments crafted by artists.

🔼 This table lists all the notations used in the paper and their corresponding descriptions, providing a comprehensive glossary of symbols and terms for better understanding of the methodologies and results presented.

read the caption

Table 5. Explanation of notations used in the Main Paper.

Full paper#