↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Vision Language Models (VLMs) are powerful but computationally expensive due to processing many visual tokens from images. Current research mostly focuses on modestly reducing token numbers, while the trade-off with model size is unclear. This impacts deployment in real-world applications.

This paper investigates the optimal trade-off between model size and the number of visual tokens. It establishes scaling laws showing that for visual reasoning tasks, surprisingly, using the largest model with a minimal number of visual tokens (often one) leads to the best performance for a given computational budget. The authors introduce a new query-based token compression algorithm designed for this extreme compression regime. The results demonstrate the need to reconsider token compression strategies and suggest focusing on more significant compression.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges common assumptions in VLM optimization, revealing a surprising finding that using fewer visual tokens with larger models is computationally optimal for visual reasoning tasks. This shifts the focus of research towards extreme token compression, potentially leading to more efficient and cost-effective VLMs for real-world applications. It also opens new avenues for developing token compression algorithms optimized for high compression ratios, improving VLM deployment.

Visual Insights#

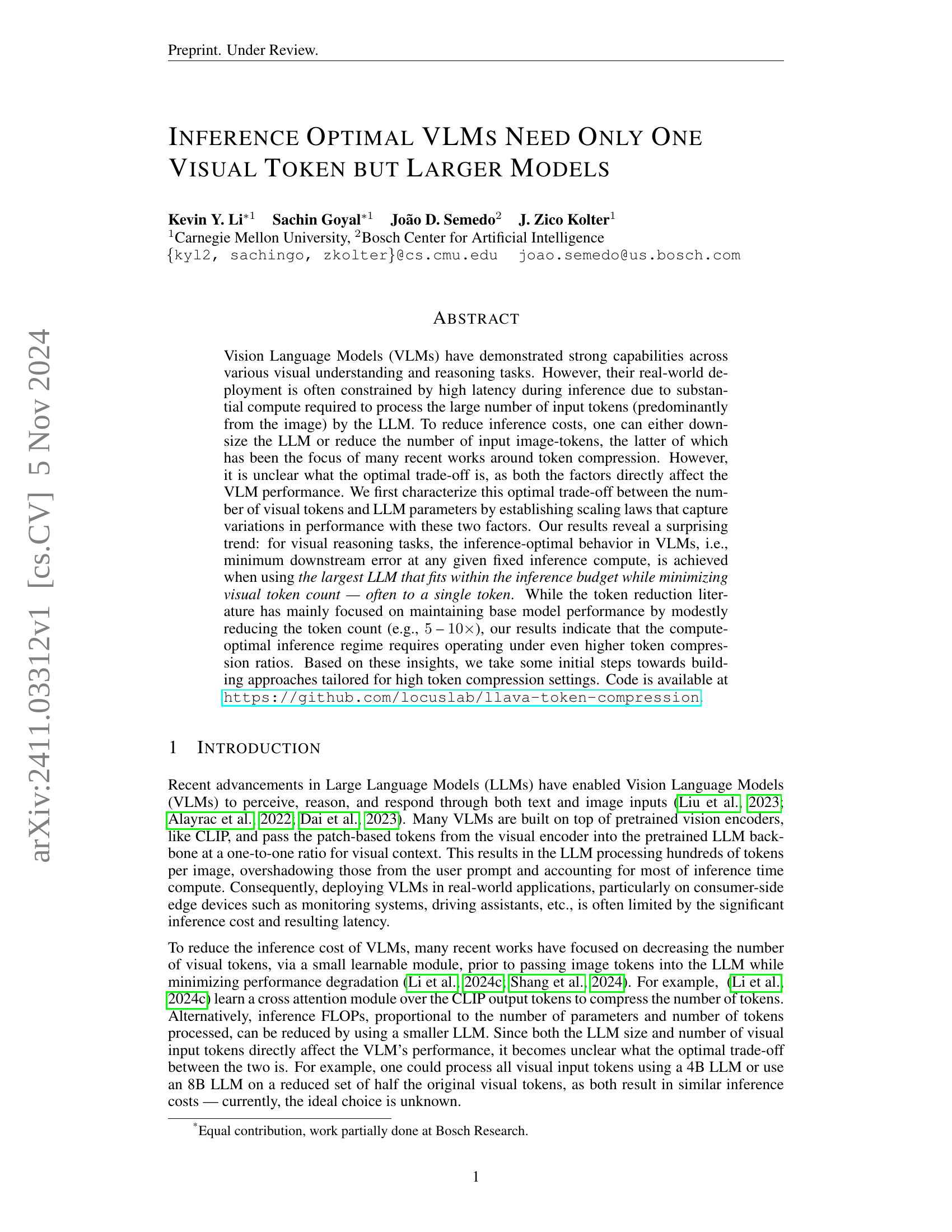

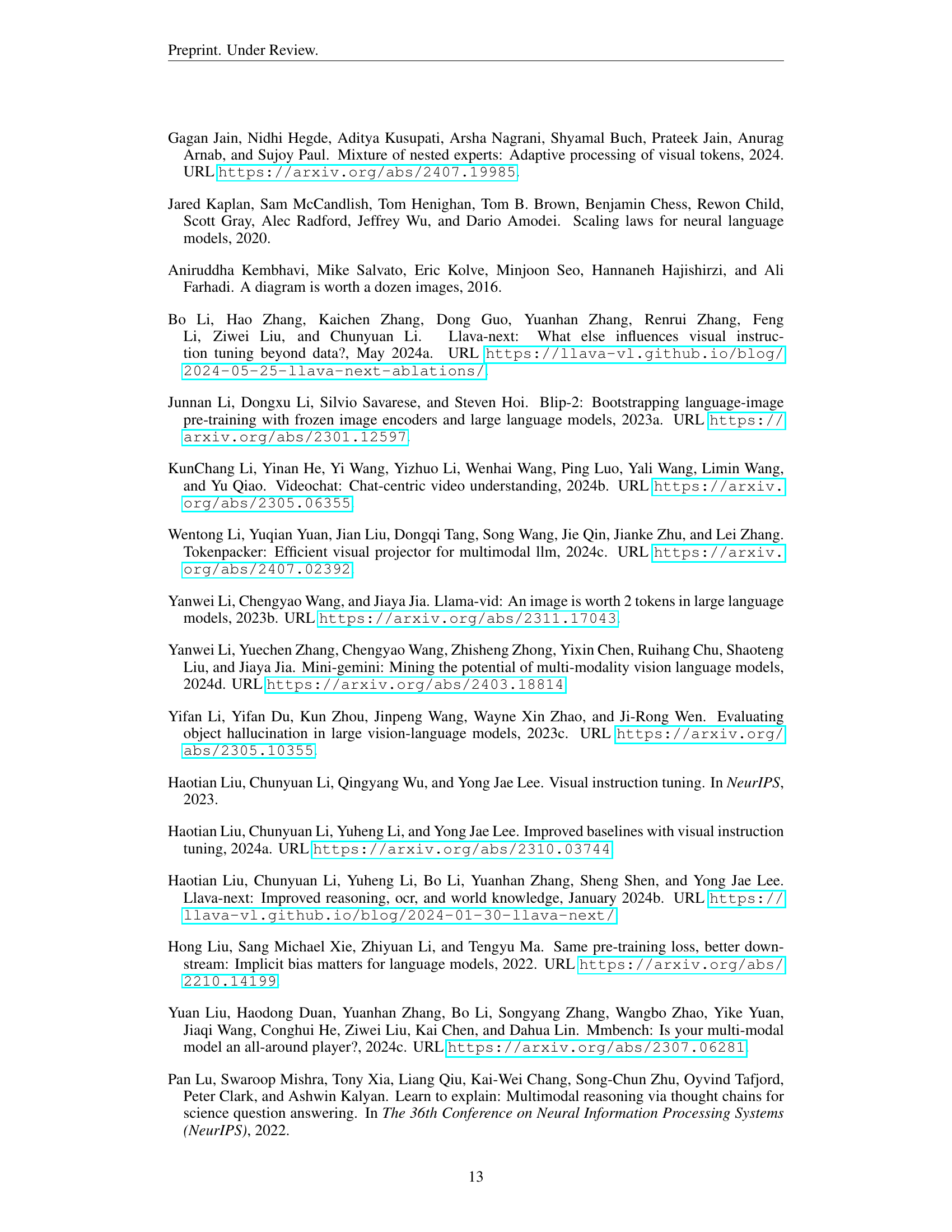

🔼 This figure displays the scaling laws for Vision Language Models (VLMs) when the input text query is cached (Q=0). The x-axis represents the inference FLOPs, a measure of computational cost, which is varied by adjusting the number of visual input tokens processed by the model. The y-axis shows the average downstream error, representing the model’s performance on downstream tasks. Different colored lines represent VLMs with different numbers of parameters (LLM sizes), demonstrating how the optimal trade-off between visual tokens and LLM size changes with computational cost.

read the caption

(a) Scaling laws for VLMs at Q=0𝑄0Q=0italic_Q = 0 (cached text).

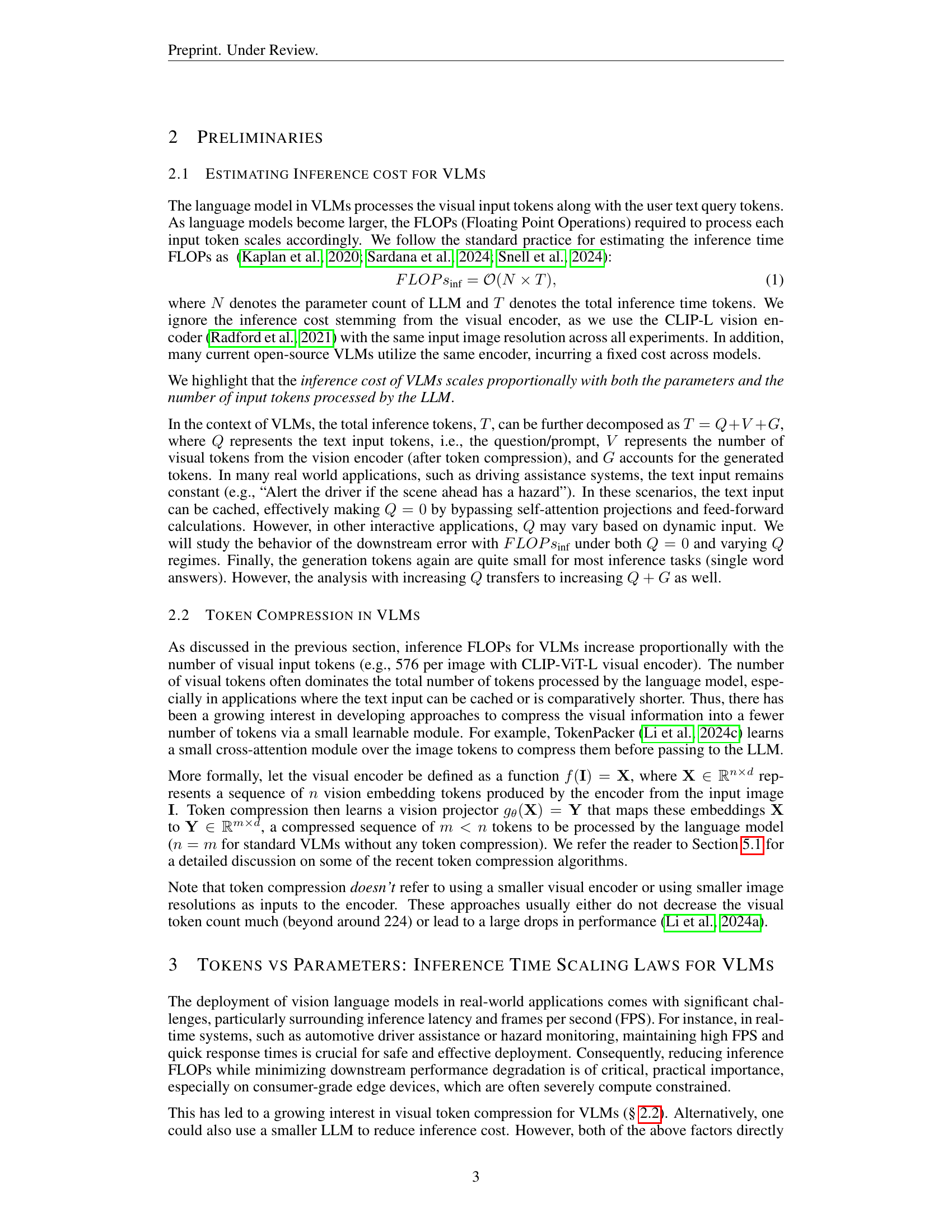

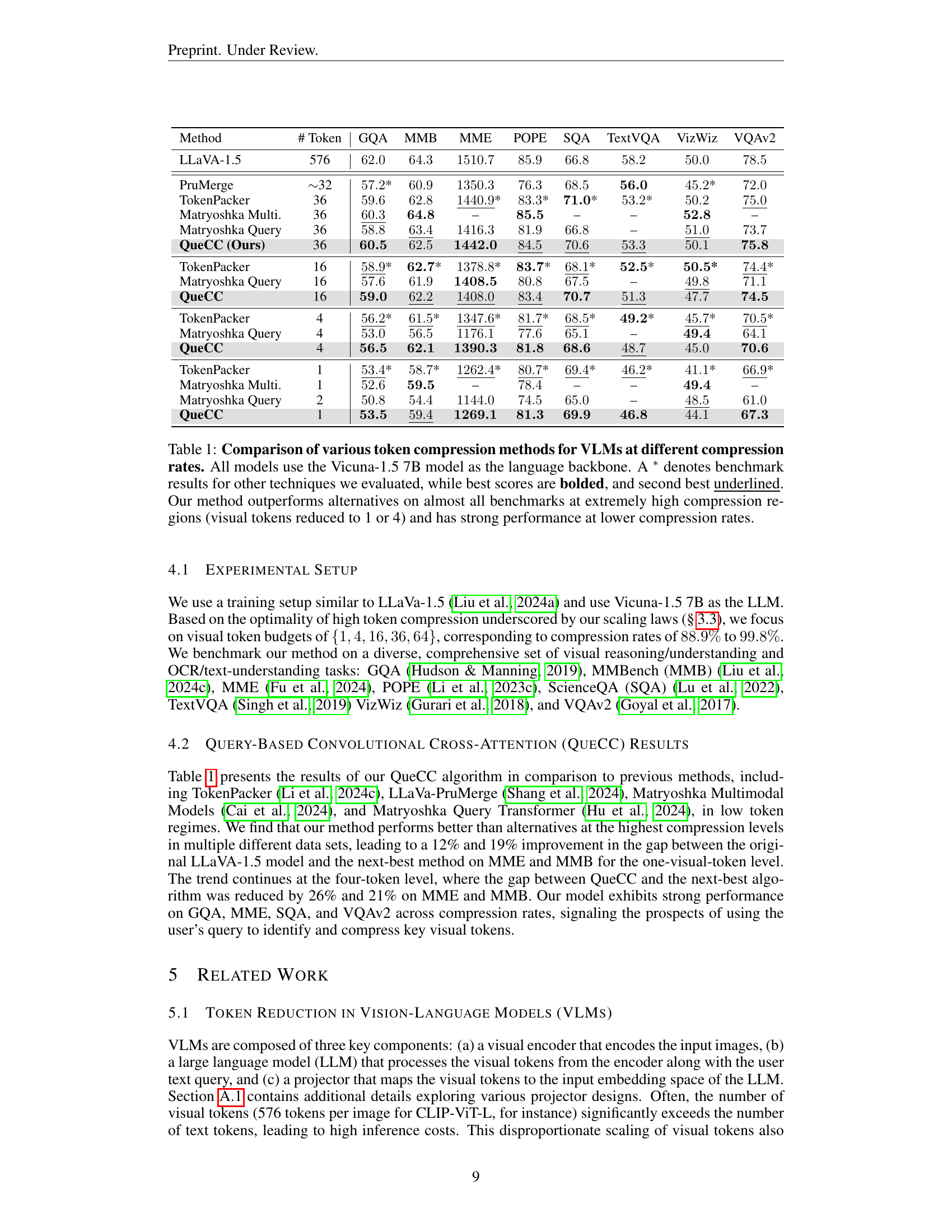

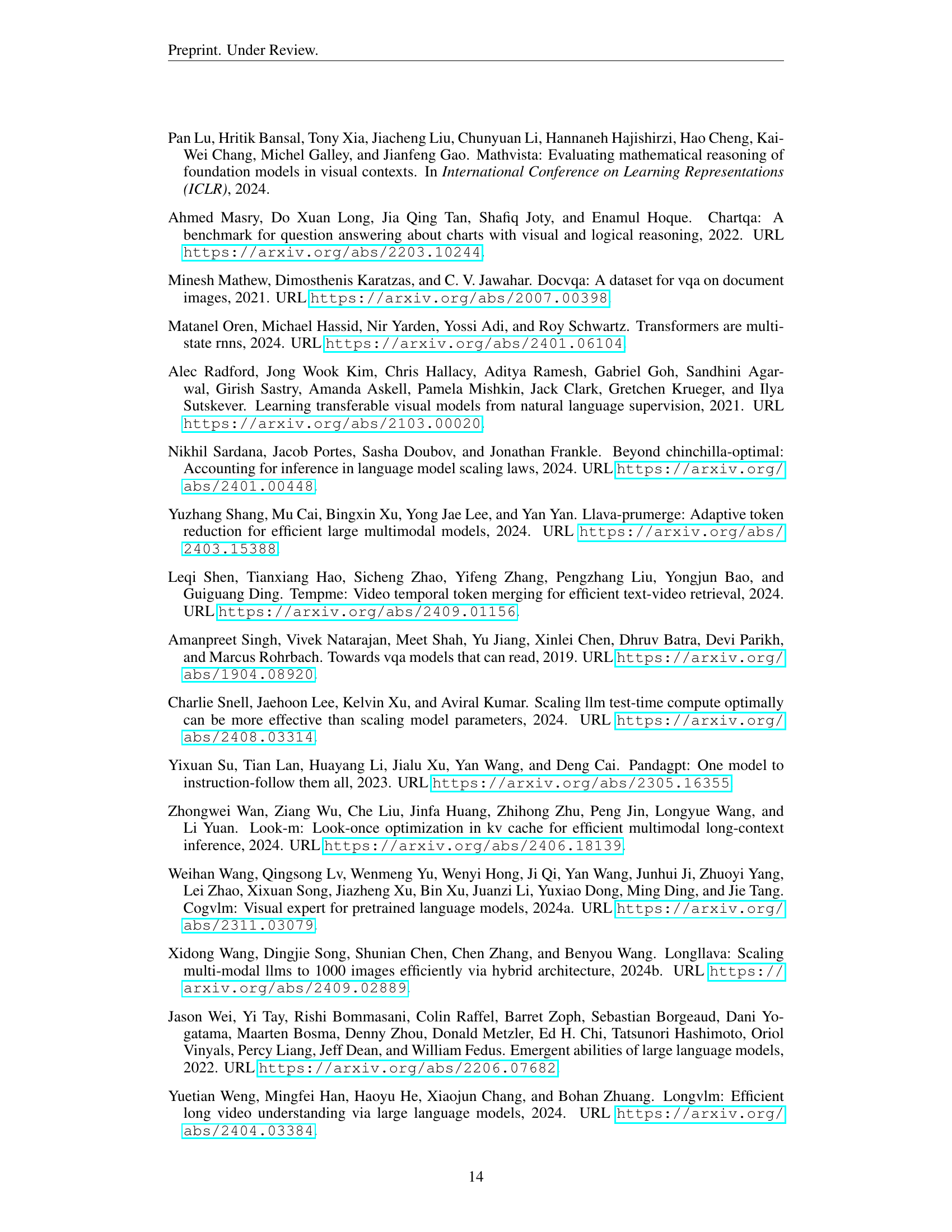

| Method | # Token | GQA | MMB | MME | POPE | SQA | TextVQA | VizWiz | VQAv2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLaVA-1.5 | 576 | 62.0 | 64.3 | 1510.7 | 85.9 | 66.8 | 58.2 | 50.0 | 78.5 |

| PruMerge | ~32 | 57.2* | 60.9 | 1350.3 | 76.3 | 68.5 | 56.0 | 45.2* | 72.0 |

| TokenPacker | 36 | 59.6 | 62.8 | 1440.9* | 83.3* | 71.0* | 53.2* | 50.2 | 75.0* |

| Matryoshka Multi. | 36 | 60.3* | 64.8 | – | 85.5 | – | – | 52.8 | – |

| Matryoshka Query | 36 | 58.8 | 63.4* | 1416.3 | 81.9 | 66.8 | – | 51.0* | 73.7 |

| QueCC (Ours) | 36 | 60.5 | 62.5 | 1442.0 | 84.5* | 70.6* | 53.3* | 50.1 | 75.8 |

| TokenPacker | 16 | 58.9* | 62.7* | 1378.8* | 83.7* | 68.1* | 52.5* | 50.5* | 74.4* |

| Matryoshka Query | 16 | 57.6 | 61.9 | 1408.5 | 80.8 | 67.5 | – | 49.8* | 71.1 |

| QueCC | 16 | 59.0 | 62.2* | 1408.0* | 83.4* | 70.7* | 51.3* | 47.7 | 74.5 |

| TokenPacker | 4 | 56.2* | 61.5* | 1347.6* | 81.7* | 68.5* | 49.2* | 45.7* | 70.5* |

| Matryoshka Query | 4 | 53.0 | 56.5 | 1176.1 | 77.6 | 65.1 | – | 49.4 | 64.1 |

| QueCC | 4 | 56.5 | 62.1* | 1390.3* | 81.8* | 68.6* | 48.7* | 45.0 | 70.6 |

| TokenPacker | 1 | 53.4* | 58.7* | 1262.4* | 80.7* | 69.4* | 46.2* | 41.1* | 66.9* |

| Matryoshka Multi. | 1 | 52.6 | 59.5 | – | 78.4 | – | – | 49.4 | – |

| Matryoshka Query | 2 | 50.8 | 54.4 | 1144.0 | 74.5 | 65.0 | – | 48.5* | 61.0 |

| QueCC | 1 | 53.5 | 59.4* | 1269.1* | 81.3* | 69.9* | 46.8* | 44.1 | 67.3 |

🔼 Table 1 compares different visual token compression methods for Vision Language Models (VLMs) across various compression ratios. All models utilize the Vicuna-1.5 7B model as their language backbone. The table shows performance on several benchmark tasks, indicating the accuracy of each method. Results marked with an asterisk (*) represent benchmarks from other studies. The best scores are in bold, and the second-best scores are underlined. The authors’ method (QueCC) shows superior performance compared to other techniques, particularly at extremely high compression rates (reducing visual tokens to 1 or 4), while still maintaining competitive performance at lower compression levels.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of various token compression methods for VLMs at different compression rates. All models use the Vicuna-1.5 7B model as the language backbone. A ∗ denotes benchmark results for other techniques we evaluated, while best scores are bolded, and second best underlined. Our method outperforms alternatives on almost all benchmarks at extremely high compression regions (visual tokens reduced to 1 or 4) and has strong performance at lower compression rates.

In-depth insights#

Optimal VLM Inference#

Optimal VLM inference focuses on minimizing the computational cost of VLMs without sacrificing performance. The core idea revolves around finding the best balance between the size of the Language Model (LLM) and the number of visual tokens processed. Contrary to existing methods that modestly reduce the visual token count, the research reveals that compute-optimal inference often involves using the largest possible LLM with a drastically reduced number of visual tokens, often just one. This counterintuitive finding suggests that investing computational resources in a larger LLM yields greater accuracy improvements than attempting more sophisticated visual token compression. However, this optimal behavior is context-dependent; it holds true particularly for visual reasoning tasks with cached text queries. When the text input is variable, a small increase in visual tokens may become necessary to balance costs. Furthermore, this optimal balance shifts with the nature of the task; for OCR tasks, for instance, the optimum shifts towards utilizing more visual tokens and potentially smaller LLMs, highlighting the task-specific nature of optimal VLM inference. Therefore, future research should focus on achieving high token compression to optimize VLM inference for various tasks.

Scaling Laws for VLMs#

The concept of “Scaling Laws for VLMs” investigates how the performance of Vision Language Models (VLMs) changes in relation to key architectural parameters, particularly model size (number of parameters) and the number of visual tokens processed. The research likely explores empirical relationships, establishing mathematical formulas or curves that predict performance based on these parameters. This would involve training VLMs with varying parameter counts and visual token resolutions, then measuring their performance on benchmark tasks. A key insight might be whether increasing model size is more beneficial than reducing the number of visual tokens (perhaps via compression techniques) for a fixed compute budget. The study might reveal optimal scaling strategies, indicating the best balance between model size and visual token count for maximum efficiency. This could potentially lead to design guidelines for creating more cost-effective VLMs, especially for resource-constrained applications. Furthermore, understanding these scaling laws might highlight the trade-offs between computational cost and performance, informing researchers in the development of novel architectures and training methodologies. The findings may reveal surprising trends, like a point of diminishing returns in increasing the number of visual tokens, thus advocating for more focused compression techniques.

Token Compression#

The concept of token compression in the context of Vision Language Models (VLMs) is crucial for optimizing inference speed and efficiency. The core idea is to reduce the number of visual tokens representing images before feeding them into the language model, thereby decreasing computational cost and latency. Many existing methods achieve modest compression, typically reducing the token count by a factor of 5-10x. However, the research highlights that this approach may not be optimal. The paper argues that for visual reasoning tasks, the best performance is achieved by using the largest possible language model and minimizing the visual token count, often to just one. This finding suggests that the field should shift towards developing techniques for significantly higher compression ratios, rather than focusing on moderately preserving the performance of the base model. The paper’s proposed query-based approach, which leverages the user’s query to compress image information, represents a crucial step in this direction. This method specifically prioritizes keeping the tokens relevant to the query, ensuring minimal performance loss despite the high compression. This work underscores the need for future research in developing effective algorithms tailored for high-compression scenarios, achieving significantly improved efficiency in VLMs without sacrificing accuracy.

Query-Based Approach#

A query-based approach to visual token compression for Vision Language Models (VLMs) offers a compelling solution to the computational cost of processing numerous visual tokens. By incorporating the user’s textual query into the compression process, the algorithm intelligently selects and prioritizes the most relevant visual information, thereby achieving significant compression ratios while minimizing performance degradation. This approach moves beyond the limitations of generic compression methods that treat all visual tokens equally, acknowledging that not all visual information is equally important for a given query. The core innovation lies in the integration of textual context to guide the token selection. This contextual awareness allows the system to focus on the aspects of the image that are most relevant to the user’s request, leading to higher compression rates and better overall efficiency. However, successful implementation requires careful consideration of the interaction between query representation, visual feature extraction, and the compression algorithm itself. The effectiveness of the method hinges on accurately capturing the essence of the query and its relevance to the visual data. This implies a need for sophisticated query embedding techniques and robust cross-modal alignment strategies. Future work might explore improvements in query embedding to better represent complex or nuanced requests, as well as enhanced cross-modal interaction mechanisms to improve the fidelity of the compressed visual representation. A key advantage is that this approach can adapt to varying query types and complexities, making it suitable for a broader range of real-world VLM applications.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize extending the scaling laws to encompass a wider array of visual tasks and modalities, moving beyond the visual reasoning benchmarks used in this study. Investigating how optimal token counts and LLM sizes shift with diverse visual data types (e.g., medical imaging, satellite imagery) is crucial. Furthermore, exploring the interaction between different token compression techniques and LLM architectures is needed to identify synergistic combinations that maximize performance while minimizing compute. Developing more sophisticated query-based compression methods that dynamically adapt to the complexity of the input query and the relevance of visual information could significantly improve efficiency. Finally, research should focus on developing novel evaluation metrics that better capture the nuances of visual-language understanding at high compression ratios. The current metrics may not fully reflect the capabilities of VLMs in these extreme regimes, hindering the assessment of true performance gains. This integrated approach will ultimately pave the way for more robust, efficient, and widely applicable VLMs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

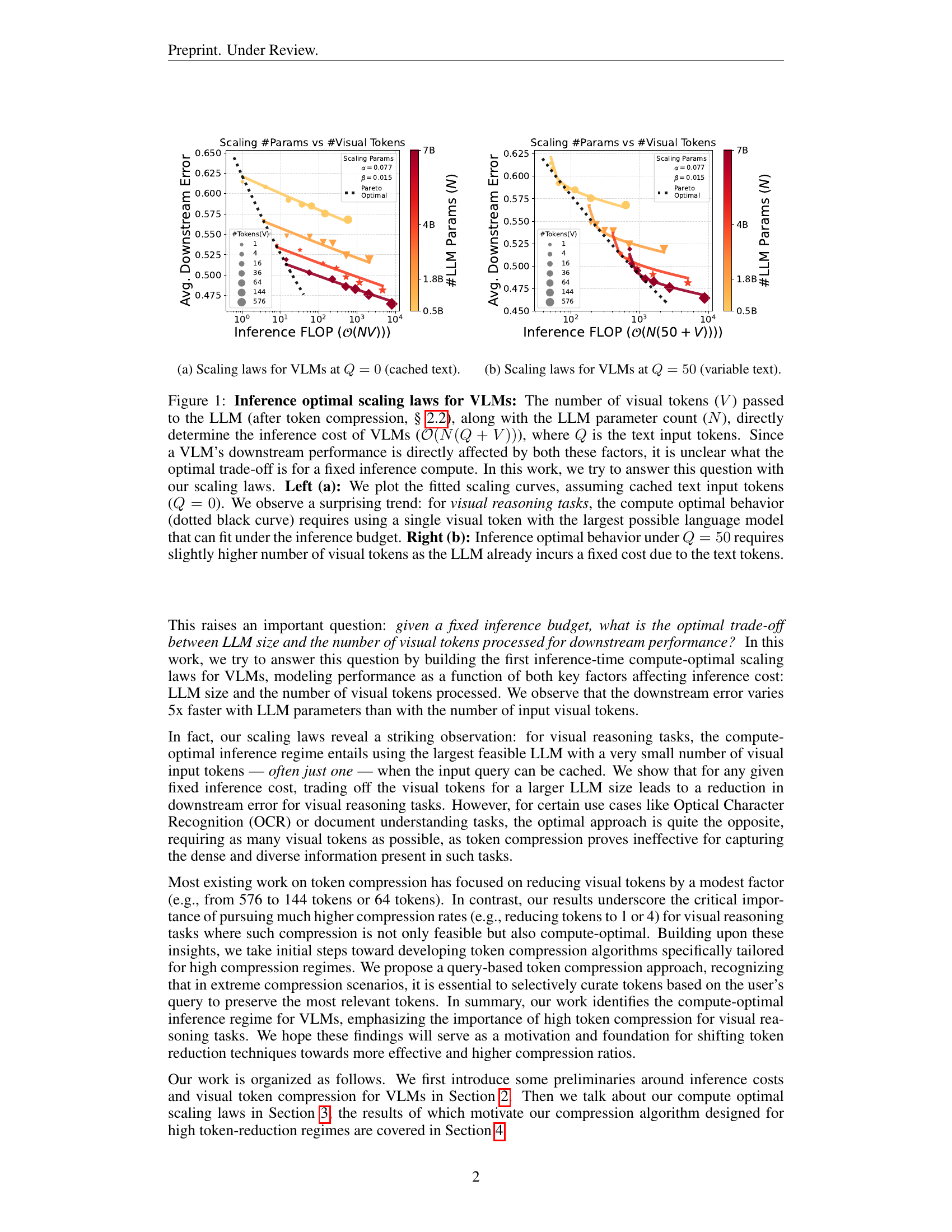

🔼 This figure shows the scaling laws for Vision Language Models (VLMs) when the number of text input tokens (Q) is variable and set to 50. The plot illustrates the relationship between average downstream error (y-axis), inference FLOPs (x-axis), the number of visual tokens (V) processed by the LLM, and the number of LLM parameters (N). Different colors represent different LLM sizes, and the size of the data points reflects the number of visual tokens used. The plot helps to visualize the optimal trade-off between LLM size and the number of visual tokens, which helps to understand the compute optimal behavior in VLMs. A dotted black line shows the Pareto optimal curve indicating the best performance for a given inference FLOP.

read the caption

(b) Scaling laws for VLMs at Q=50𝑄50Q=50italic_Q = 50 (variable text).

🔼 This figure displays scaling laws for Vision Language Models (VLMs) that illustrate the optimal trade-off between the number of visual tokens and the LLM’s parameter count under a fixed inference compute budget. The left panel (a) shows the scaling laws when text input is cached (Q=0), revealing that for visual reasoning tasks, the optimal performance is achieved with the largest LLM and only one visual token. The right panel (b) demonstrates the scenario with uncached text input (Q=50), where a slightly higher number of visual tokens becomes optimal due to the inherent computational cost of processing the text tokens.

read the caption

Figure 1: Inference optimal scaling laws for VLMs: The number of visual tokens (V𝑉Vitalic_V) passed to the LLM (after token compression, § 2.2), along with the LLM parameter count (N𝑁Nitalic_N), directly determine the inference cost of VLMs (𝒪(N(Q+V))𝒪𝑁𝑄𝑉\mathcal{O}(N(Q+V))caligraphic_O ( italic_N ( italic_Q + italic_V ) )), where Q𝑄Qitalic_Q is the text input tokens. Since a VLM’s downstream performance is directly affected by both these factors, it is unclear what the optimal trade-off is for a fixed inference compute. In this work, we try to answer this question with our scaling laws. Left (a): We plot the fitted scaling curves, assuming cached text input tokens (Q=0𝑄0Q=0italic_Q = 0). We observe a surprising trend: for visual reasoning tasks, the compute optimal behavior (dotted black curve) requires using a single visual token with the largest possible language model that can fit under the inference budget. Right (b): Inference optimal behavior under Q=50𝑄50Q=50italic_Q = 50 requires slightly higher number of visual tokens as the LLM already incurs a fixed cost due to the text tokens.

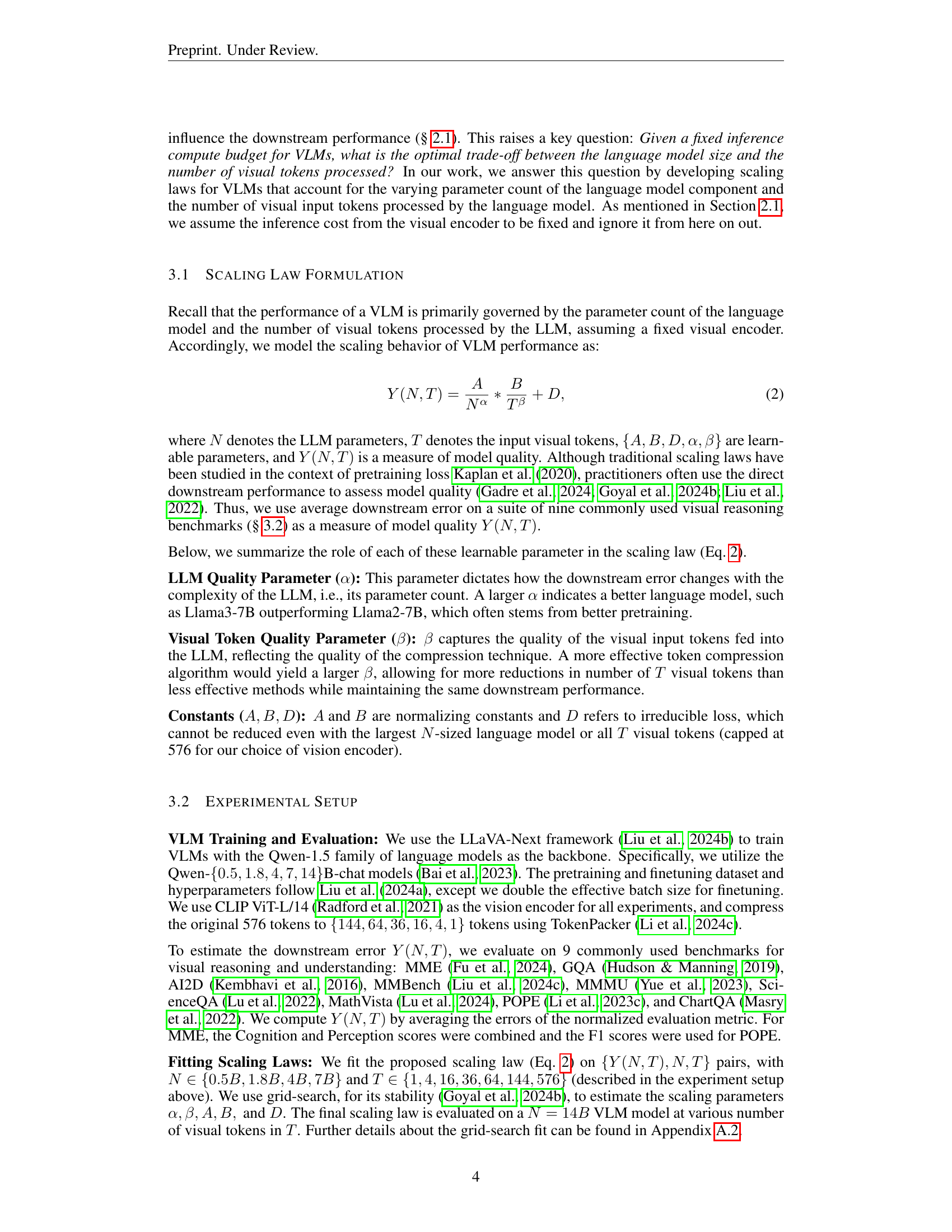

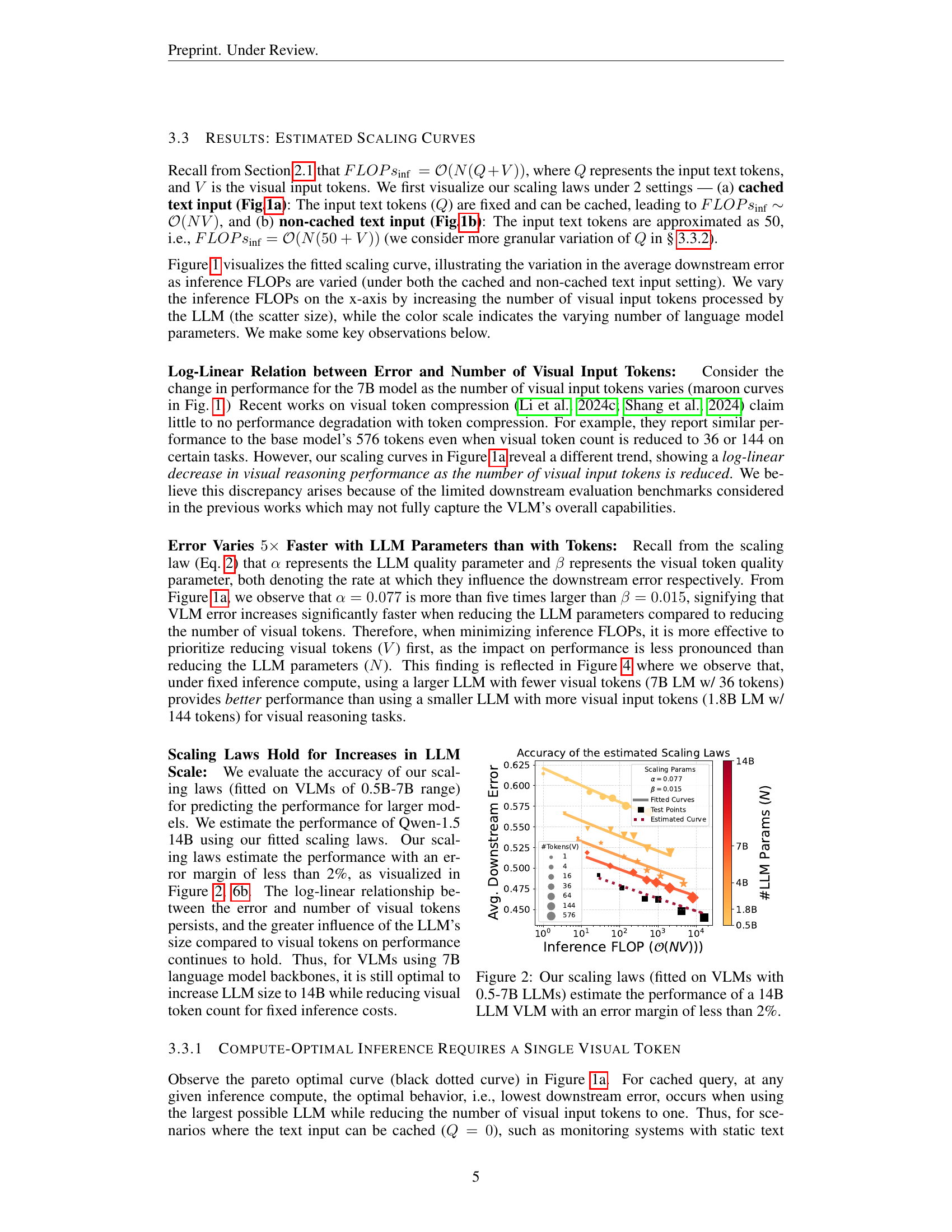

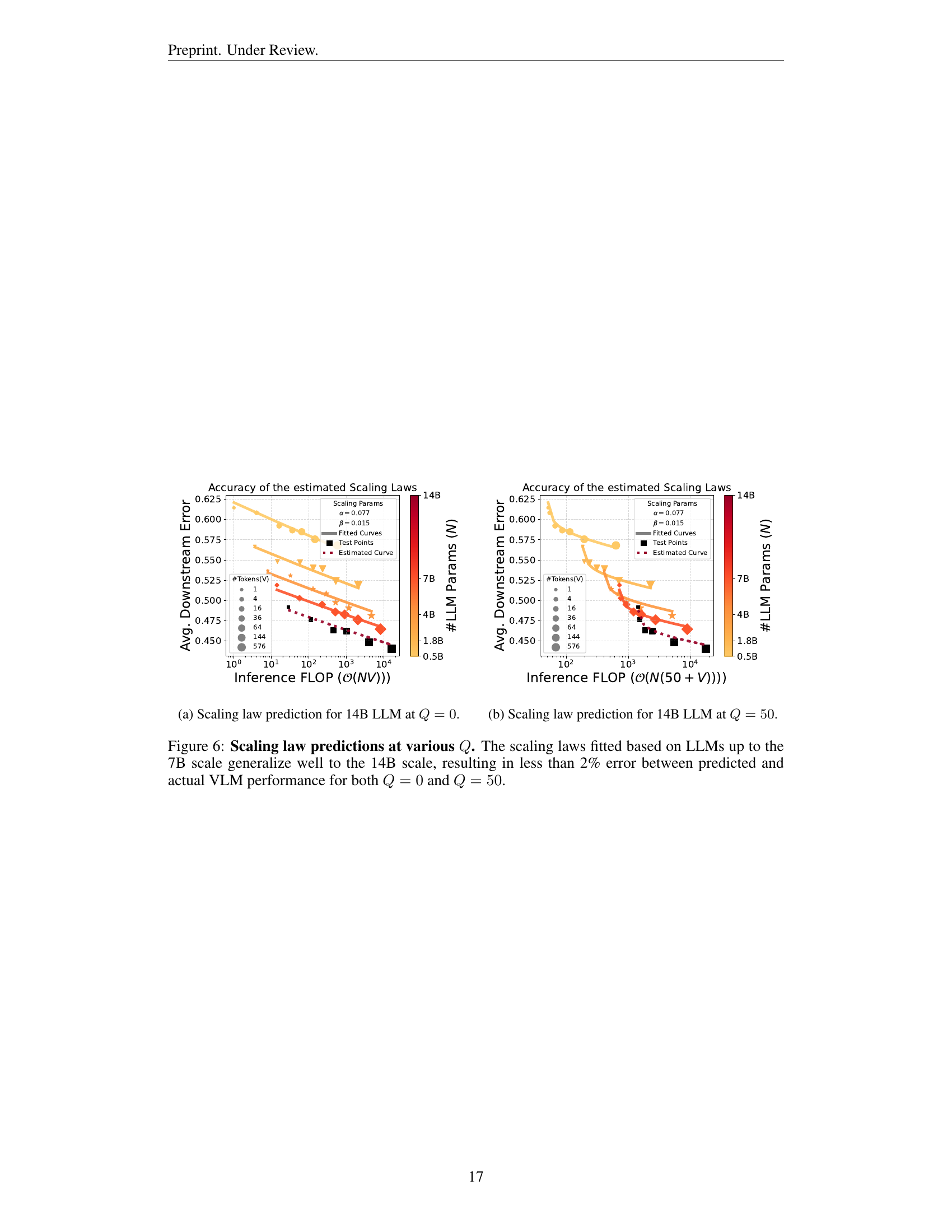

🔼 Figure 2 shows that the scaling laws derived from experiments using 0.5B to 7B parameter LLMs accurately predict the performance of a significantly larger 14B parameter LLM. The figure demonstrates the generalizability of the scaling laws across a wide range of model sizes. The prediction error is less than 2%, indicating a high degree of accuracy and reliability in the established scaling relationship between LLM parameters, number of visual tokens, and downstream performance. This validates the use of the scaling laws for evaluating the performance of larger models without the need for extensive and costly retraining.

read the caption

Figure 2: Our scaling laws (fitted on VLMs with 0.5-7B LLMs) estimate the performance of a 14B LLM VLM with an error margin of less than 2%.

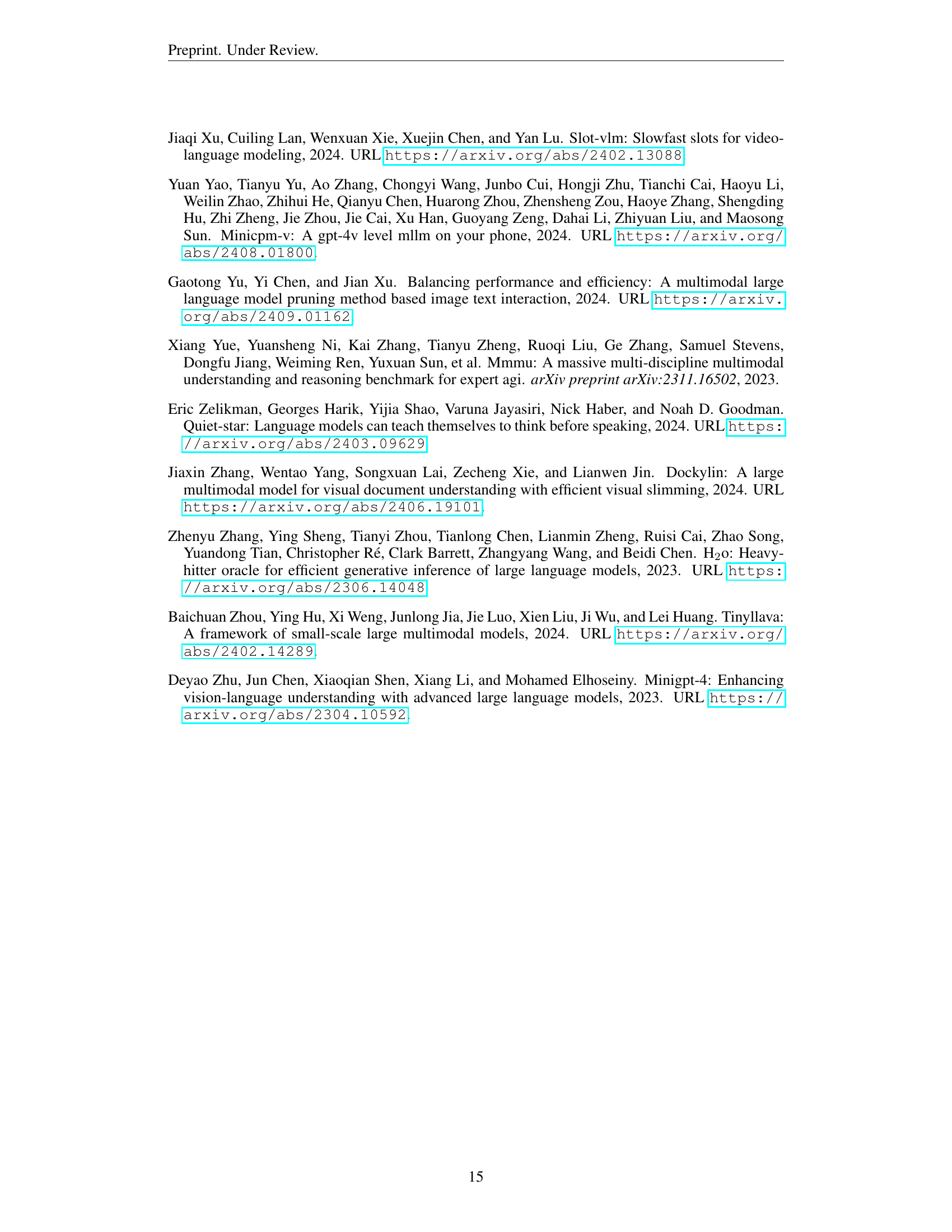

🔼 This figure demonstrates how the optimal balance between the number of visual tokens and LLM size for VLMs varies depending on the length of the input text query (Q). As Q increases, the cost of processing text tokens in the VLM increases. Therefore, the impact of adding more visual tokens becomes less significant relative to the impact of increasing LLM size. Initially, with short queries, using a larger LLM with fewer visual tokens is better. But with longer queries, using a smaller LLM with more visual tokens can become more optimal, as the added cost from extra visual tokens is outweighed by the benefits of a larger LLM. This demonstrates the importance of considering the interaction between text and visual tokens when optimizing VLM performance.

read the caption

(a) Performance trends and trade-offs of VLMs change when varying the number of input text token Q𝑄Qitalic_Q.

🔼 The figure demonstrates that for Optical Character Recognition (OCR) tasks, unlike visual reasoning tasks, increasing the number of visual tokens improves performance more significantly than increasing the LLM size. This contrasts with the findings for visual reasoning tasks, where larger LLMs with fewer visual tokens were optimal. The plot shows downstream error as a function of inference FLOPs, with different colored lines representing different LLM parameter sizes and point sizes indicating the number of visual tokens. The results suggest that for OCR-like tasks, preserving more visual detail is paramount, even at the cost of using smaller LLMs.

read the caption

(b) Scaling laws on OCR-like tasks favor visual token count over LLM size; the opposite of visual reasoning.

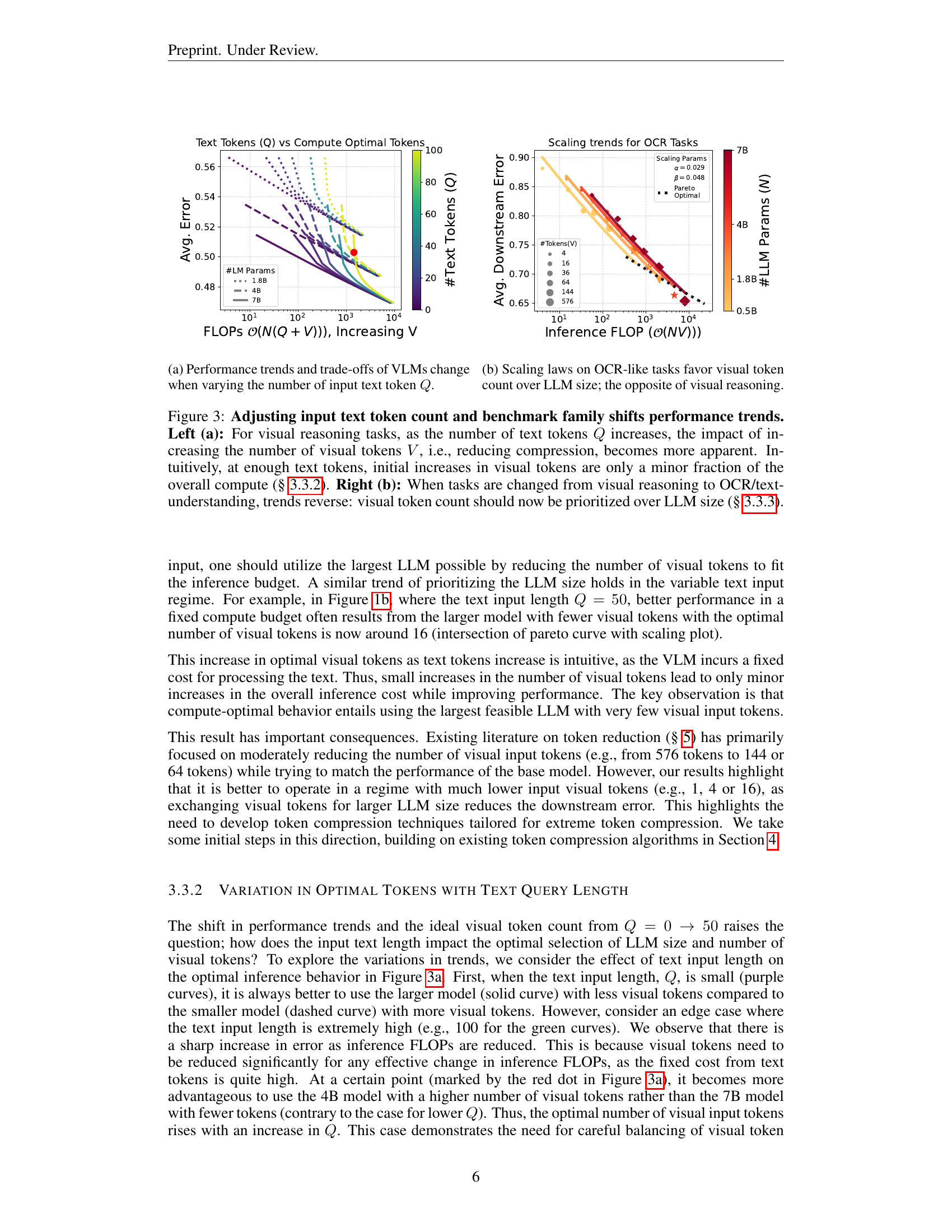

🔼 Figure 3 explores how the optimal balance between the number of visual tokens and LLM size changes depending on the task and the length of the text input. The left panel (a) shows that for visual reasoning tasks, increasing the number of text tokens makes the effect of adding more visual tokens less significant, because the text token processing dominates the computational cost. Conversely, for OCR and text understanding tasks (right panel, b), the performance is more strongly affected by the number of visual tokens than the LLM size, reversing the trend observed for visual reasoning.

read the caption

Figure 3: Adjusting input text token count and benchmark family shifts performance trends. Left (a): For visual reasoning tasks, as the number of text tokens Q𝑄Qitalic_Q increases, the impact of increasing the number of visual tokens V𝑉Vitalic_V, i.e., reducing compression, becomes more apparent. Intuitively, at enough text tokens, initial increases in visual tokens are only a minor fraction of the overall compute (§ 3.3.2). Right (b): When tasks are changed from visual reasoning to OCR/text-understanding, trends reverse: visual token count should now be prioritized over LLM size (§ 3.3.3).

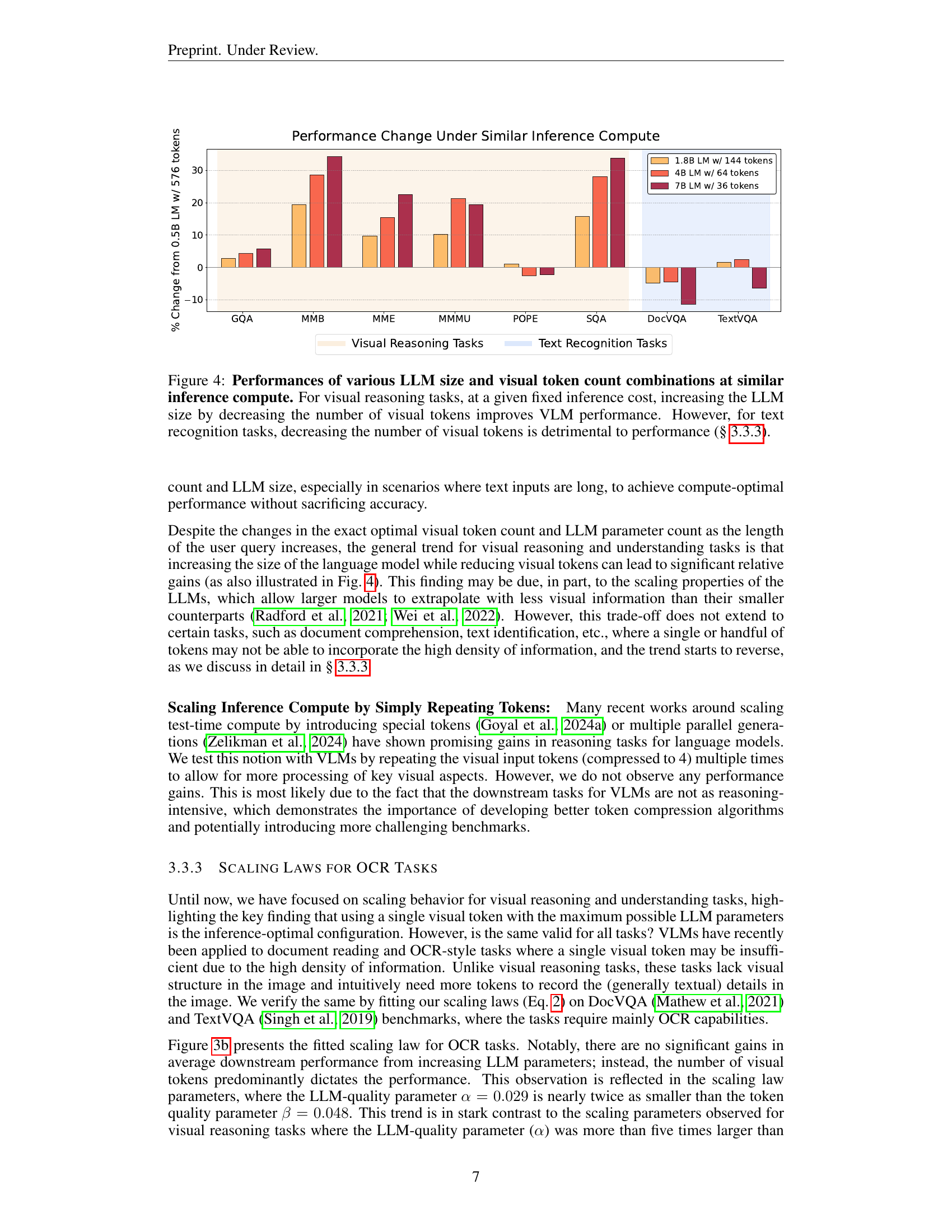

🔼 Figure 4 presents a bar chart comparing the performance of different Vision Language Models (VLMs) across various visual reasoning and text recognition tasks. The models vary in their size (LLM parameter count) and the number of visual tokens processed. Importantly, all models are evaluated at approximately the same inference compute cost. The chart shows that for visual reasoning tasks, increasing model size while simultaneously decreasing the number of visual tokens leads to better performance. This supports the finding that for these types of tasks, larger models can leverage smaller sets of well-chosen visual information more effectively. In contrast, for text recognition tasks, reducing the number of visual tokens negatively impacts the model’s performance, regardless of model size. This indicates that text recognition relies more heavily on the detail contained within a large number of visual tokens.

read the caption

Figure 4: Performances of various LLM size and visual token count combinations at similar inference compute. For visual reasoning tasks, at a given fixed inference cost, increasing the LLM size by decreasing the number of visual tokens improves VLM performance. However, for text recognition tasks, decreasing the number of visual tokens is detrimental to performance (§ 3.3.3).

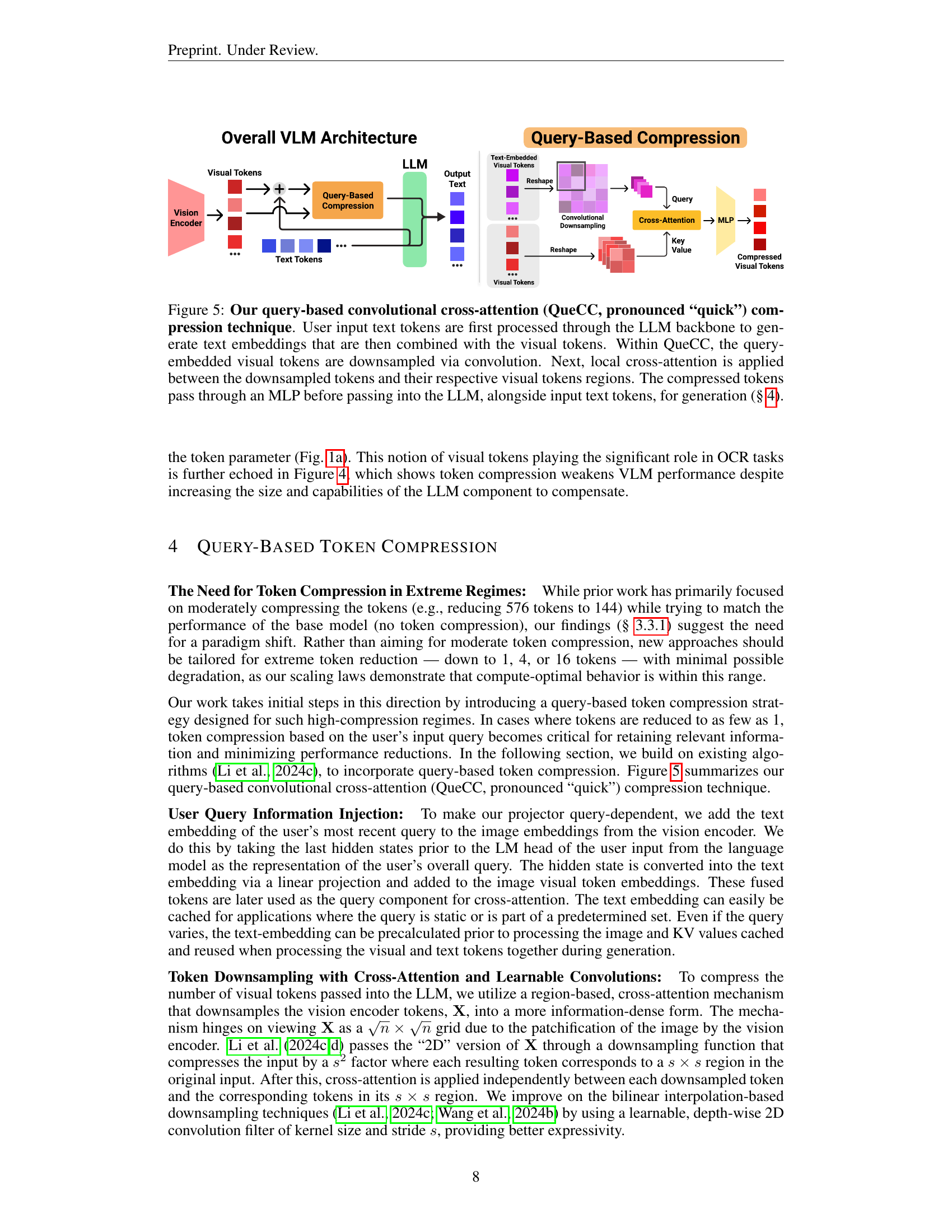

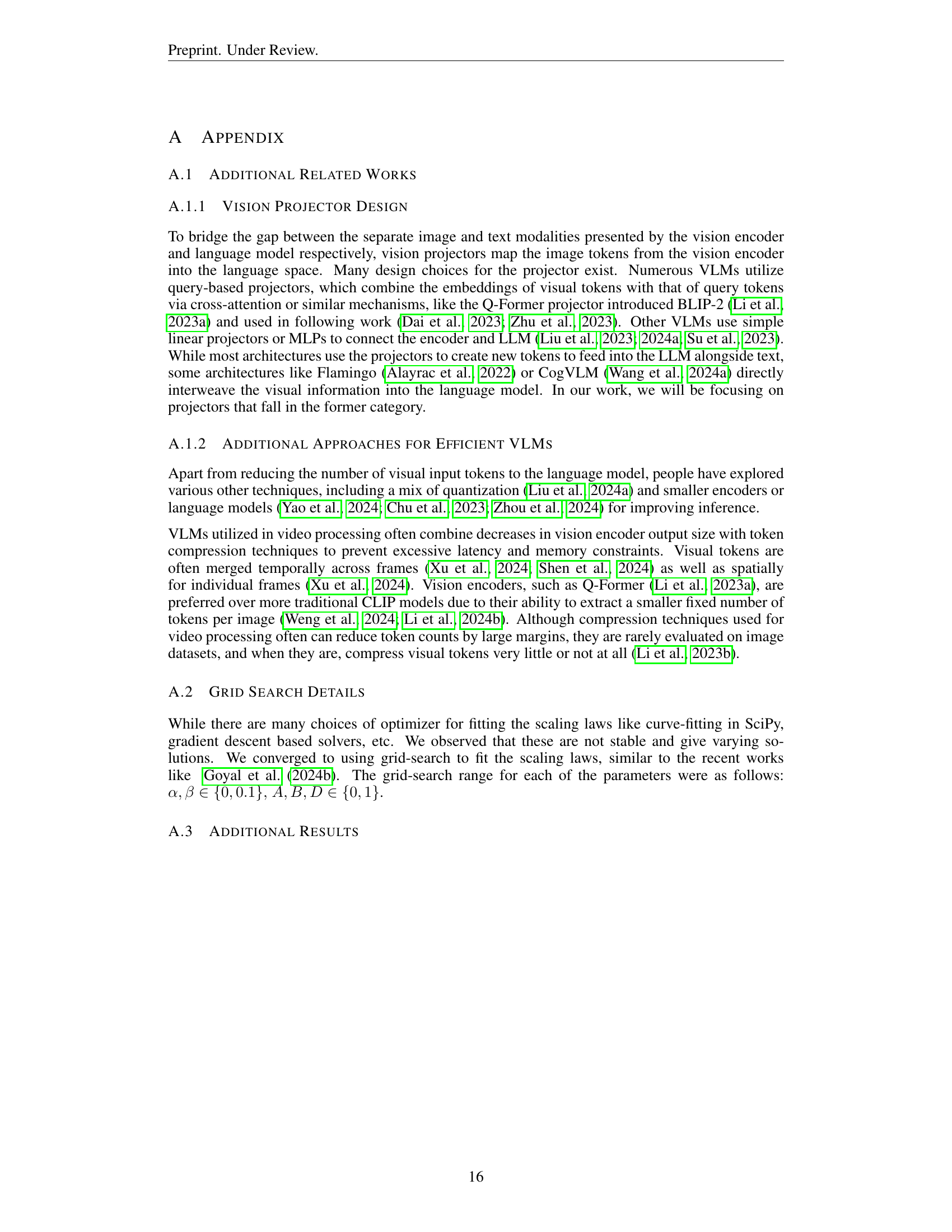

🔼 Figure 5 illustrates the architecture of QueCC (Query-based convolutional cross-attention), a novel token compression technique designed for high compression ratios. The process begins with user input text tokens, processed by the LLM backbone to produce text embeddings. These embeddings are combined with the original visual tokens. The core of QueCC then downsamples these query-embedded visual tokens using a convolutional layer, followed by applying local cross-attention between the downsampled tokens and their corresponding visual token regions. Finally, the compressed visual tokens are passed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) before being fed into the LLM, alongside the original text tokens, for final generation.

read the caption

Figure 5: Our query-based convolutional cross-attention (QueCC, pronounced “quick”) compression technique. User input text tokens are first processed through the LLM backbone to generate text embeddings that are then combined with the visual tokens. Within QueCC, the query-embedded visual tokens are downsampled via convolution. Next, local cross-attention is applied between the downsampled tokens and their respective visual tokens regions. The compressed tokens pass through an MLP before passing into the LLM, alongside input text tokens, for generation (§ 4).

Full paper#