↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Many businesses now outsource LLM inference due to high hardware costs, creating concerns about transparency. Buyers have no way to verify claims about the hardware used, and providers may substitute cheaper hardware or models, defrauding clients. This issue is especially pertinent given concerns about malicious actors deploying models with weaker security or violating geographical location agreements.

This paper introduces Hardware and Software Platform Inference (HSPI), a method to identify the underlying GPU architecture and software stack of an LLM solely based on its input-output behavior. HSPI leverages subtle differences in how various GPU architectures and compilers perform calculations. The authors propose a classification framework that analyzes numerical patterns in model outputs to accurately identify the GPU and software configuration. Their results demonstrate the feasibility of inferring GPU type from black-box models, achieving high accuracy in both white-box and black-box tests. The paper also discusses limitations and possible future applications of HSPI.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical issue of transparency and accountability in the rapidly growing LLM market. By introducing a novel method for verifying the hardware and software used by LLM providers, it enhances trust and potentially improves the governance of this vital technology. Its findings open new avenues for research into model security, provenance, and performance benchmarking. The techniques used could also be valuable in related AI domains.

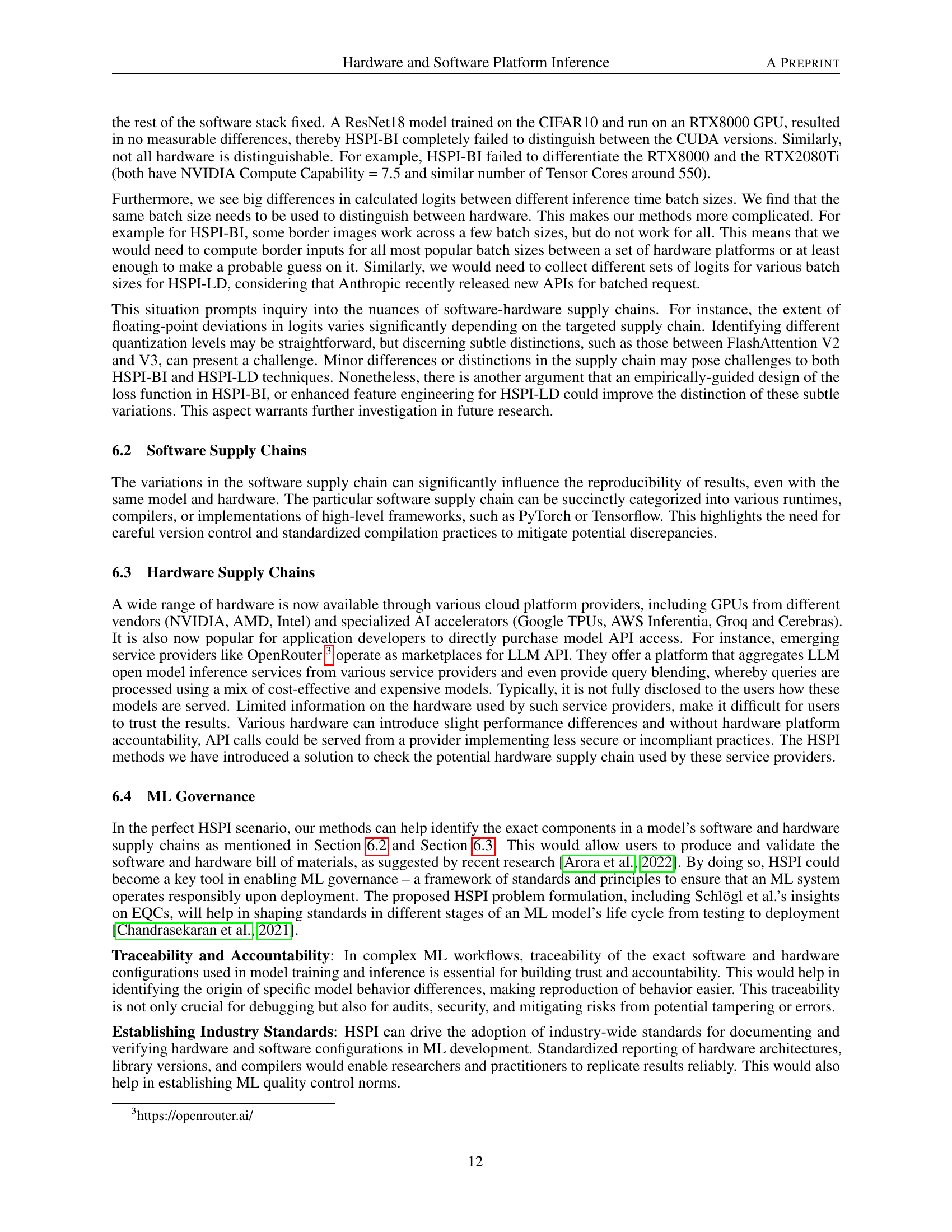

Visual Insights#

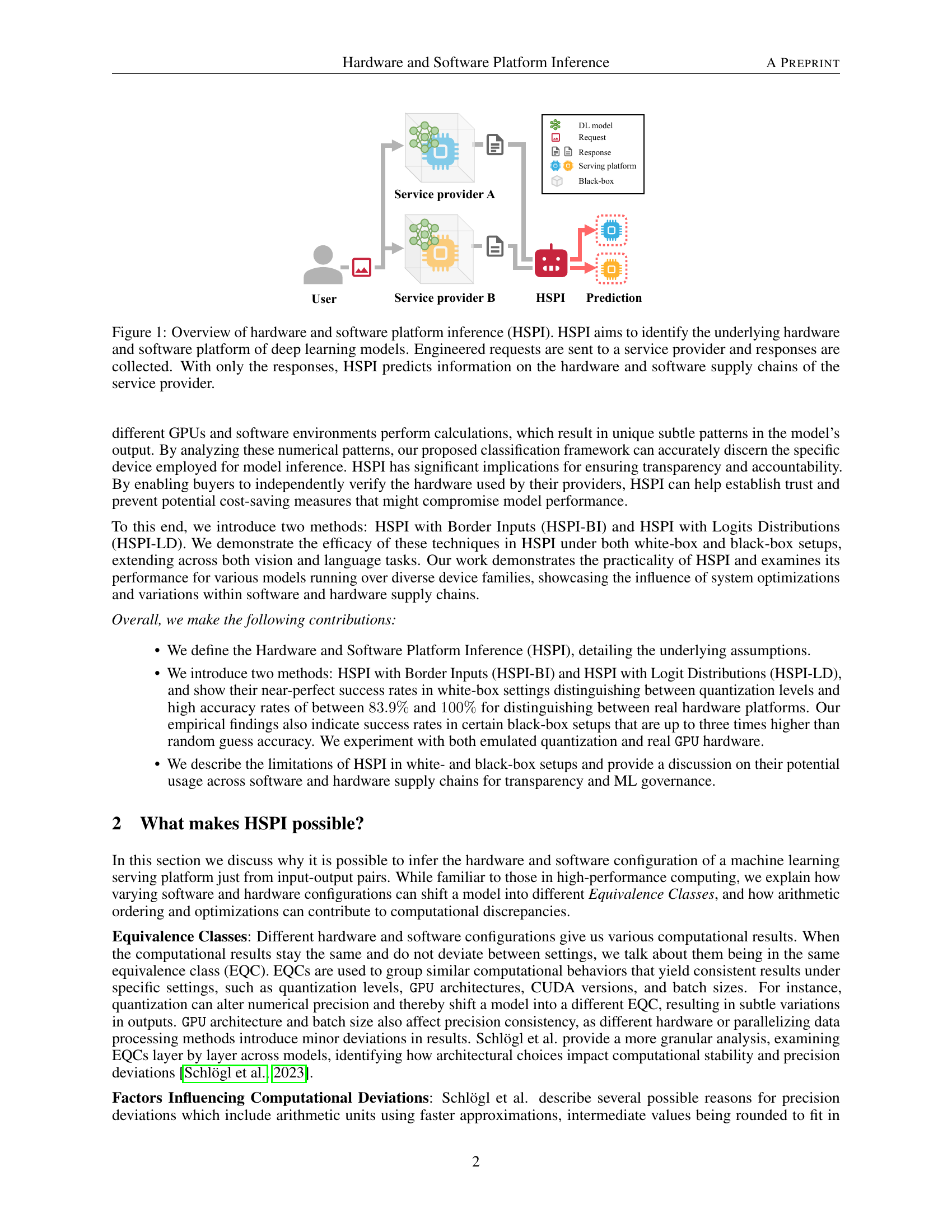

🔼 The figure illustrates the process of Hardware and Software Platform Inference (HSPI). A user sends engineered requests to a service provider (A or B), which utilizes a deep learning model hosted on a specific hardware and software platform. The service provider returns responses to the user. HSPI analyzes these responses alone, without access to the model or the underlying hardware/software details, to infer the platform used by the provider, revealing the hardware and software supply chain involved.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of hardware and software platform inference (HSPI). HSPI aims to identify the underlying hardware and software platform of deep learning models. Engineered requests are sent to a service provider and responses are collected. With only the responses, HSPI predicts information on the hardware and software supply chains of the service provider.

| Method | Training Model | Test Model | FP32 | BF16 | FP16 | MXINT8 | FP8-E3 | FP8-E4 | INT8 | Avg. F1. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSPI-BI | VGG16 | Other models | 0 | 0 | 0.167 | 0.234 | 0.159 | 0.253 | 0.218 | 0.147 |

| ResNet18 | Other models | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.293 | 0.286 | 0.167 | 0.286 | 0.206 | |

| MobileNet-v2 | Other models | 0.235 | 0.345 | 0.218 | 0.167 | 0.286 | 0.444 | 0.444 | 0.345 | |

| HSPI-LD | VGG16 | Other models | 0.394 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.95 | 0.65 | 0.2 | 0.599 |

| ResNet18 | Other models | 0.332 | 1 | 0.986 | 0.318 | 0.972 | 0.682 | 0.446 | 0.677 | |

| ResNet50 | Other models | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.056 | 0.602 | 0.634 | 0.642 | 0.562 | |

| MobileNet-v2 | Other models | 0.026 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.342 | 0.768 | 0.69 | 0.498 | 0.561 | |

| EfficientNet | Other models | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.612 | 0.592 | 0.486 | |

| DenseNet-121 | Other models | 0.102 | 1 | 0.996 | 0.34 | 0.926 | 0.514 | 0.638 | 0.645 |

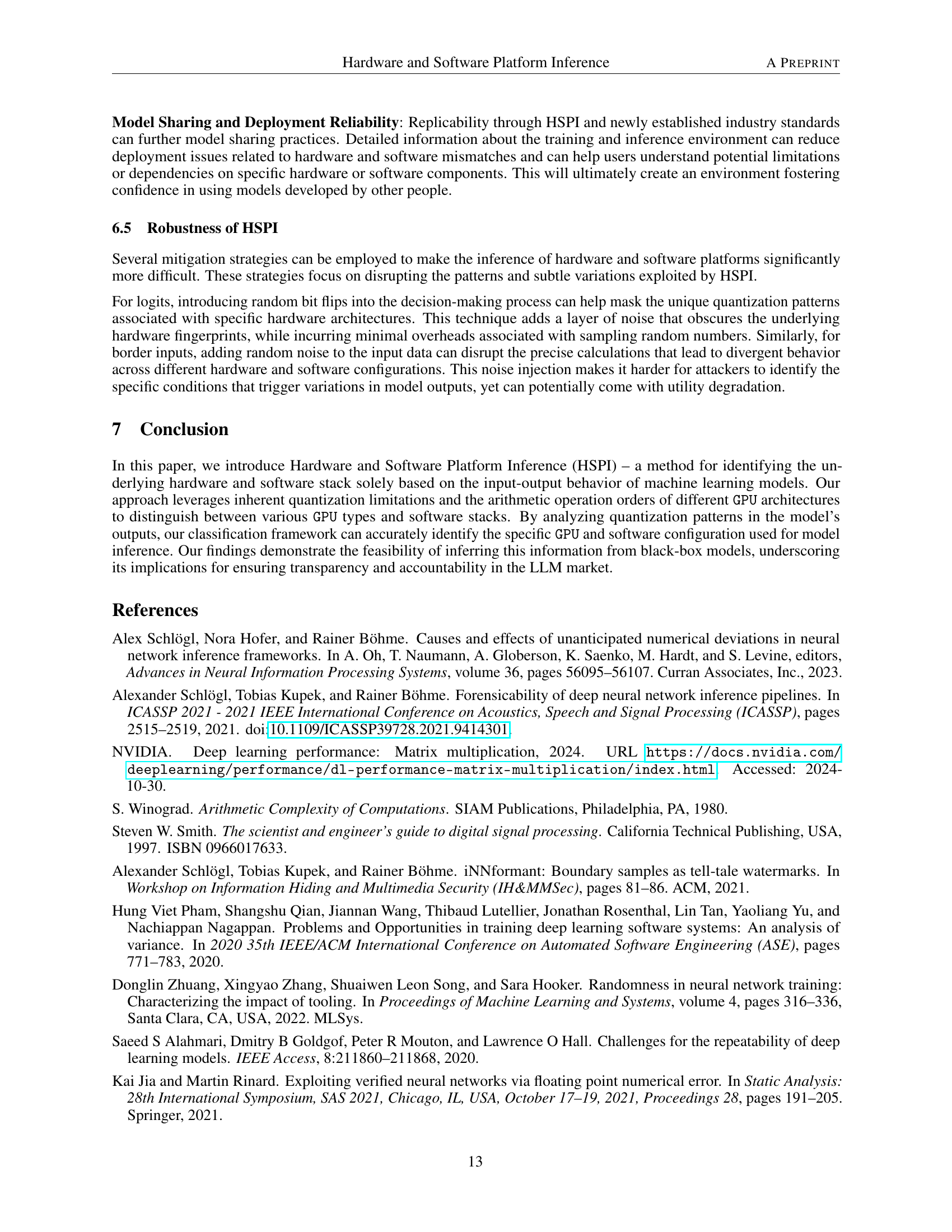

🔼 This table presents the results of a white-box experiment aimed at creating border images for different GPUs. The experiment tested the ability to generate input images that would produce different classification labels depending on the GPU used for inference. The success of this process is indicated by an ‘X’ in the table. The experiment was conducted using a batch size of 1, meaning that only one image was processed at a time for each inference.

read the caption

Table 1: Table showing success in creating border images for different GPUs in white-box with an inference time batch size of 1.

In-depth insights#

Hardware Inference#

Hardware inference, in the context of machine learning models, presents a novel approach to verifying the authenticity of cloud-based services. It addresses the lack of transparency in the hardware used by LLM providers, a critical concern as businesses increasingly rely on third-party services. By analyzing the subtle numerical patterns in a model’s output, this technique aims to identify the underlying GPU architecture and software stack, even without direct access to the model’s internal workings. This is accomplished by exploiting the inherent variations in how calculations are executed across different hardware and software environments. The implications are significant, as it could deter providers from substituting less expensive hardware and ensure clients receive the promised computational resources and performance. Future research should focus on improving accuracy and addressing limitations in black-box scenarios, which are critical for practical applications within the rapidly evolving landscape of large language models.

HSPI Methodology#

A hypothetical “HSPI Methodology” section would delve into the specifics of how Hardware and Software Platform Inference is performed. It would likely detail the two proposed methods: HSPI with Border Inputs (HSPI-BI) and HSPI with Logits Distributions (HSPI-LD). HSPI-BI would be explained as a technique that uses specifically crafted inputs, or border inputs, to highlight subtle differences in output between various hardware/software configurations. The process of generating these border inputs, possibly involving iterative methods like Projected Gradient Descent (PGD), would be described. HSPI-LD, conversely, would focus on analyzing the statistical distributions of model output logits (pre-softmax probabilities), looking for characteristic patterns linked to specific hardware and software setups. The methodology would also address the challenges in obtaining necessary data, specifically noting the differences between white-box (full model access) and black-box (only input/output access) scenarios, explaining how the approach adapts to these limitations. Finally, it would discuss the use of machine learning classifiers, such as SVMs, to analyze the collected data and classify the underlying hardware and software platform.

Black-Box Limits#

The hypothetical section “Black-Box Limits” in a research paper on hardware and software platform inference (HSPI) would explore the inherent challenges in applying HSPI to completely black-box machine learning models. The primary limitation is the lack of access to internal model states or parameters. This contrasts with the white-box setting where complete model architecture and internal workings are known, enabling precise analysis of numerical patterns to identify hardware/software characteristics. In a black-box scenario, inference is solely based on input-output pairs, significantly limiting the ability to identify subtle computational variations caused by underlying hardware. The section would likely discuss the reduced accuracy of HSPI in black-box settings and potential mitigation strategies such as increased input sampling, or the use of advanced statistical techniques to extract meaningful patterns from limited observations. It might also examine how model obfuscation techniques employed by providers could further hinder HSPI’s effectiveness, presenting a significant challenge to transparent and accountable AI service delivery. Furthermore, the generalizability of findings across diverse models and hardware architectures would likely be discussed. The practical implications regarding the trade-off between transparency and the black-box nature of many commercial models would also be a key focus of the discussion.

Software Effects#

Software significantly influences the reproducibility and reliability of machine learning model outputs. Variations in compilers, runtimes, and framework implementations create subtle but measurable differences in numerical results, even when using identical hardware and models. This highlights the critical need for standardized software environments to ensure consistency and comparability across different deployments. The software stack’s impact is often intertwined with hardware factors, making it challenging to isolate the influence of each. This highlights the importance of considering both hardware and software when assessing the performance and reliability of AI models. Lack of software transparency further hinders reproducibility, as differing software configurations may lead to different equivalence classes for computational results. To enhance the trustworthiness of AI systems and improve the governance of ML supply chains, establishing clear standards for documenting and reporting software components is crucial. Such documentation will also facilitate the identification and debugging of reproducibility issues, contributing towards greater transparency and accountability in the broader ML ecosystem.

Future of HSPI#

The future of Hardware and Software Platform Inference (HSPI) is bright, driven by the increasing demand for transparency and accountability in the machine learning (ML) market. Further research should focus on improving the robustness of HSPI against adversarial attacks and improving the accuracy of inference in black-box settings. This will involve exploring advanced techniques like analyzing more subtle computational patterns and incorporating diverse datasets. The development of standardized benchmarks and datasets for evaluating HSPI is crucial. Collaboration between researchers, service providers, and hardware manufacturers will accelerate progress, fostering the creation of industry-wide standards for supply chain transparency. As the adoption of HSPI grows, we can anticipate its integration into ML governance frameworks, promoting fairness, security, and trust. HSPI’s applications are not limited to LLMs; its potential extends to other ML models and hardware platforms. The ultimate goal is to develop a mature and reliable HSPI that effectively ensures the integrity and ethical deployment of ML models globally. This would help mitigate issues around unfair pricing, security breaches, and unexpected performance differences and boost trust and adoption.

More visual insights#

More on figures

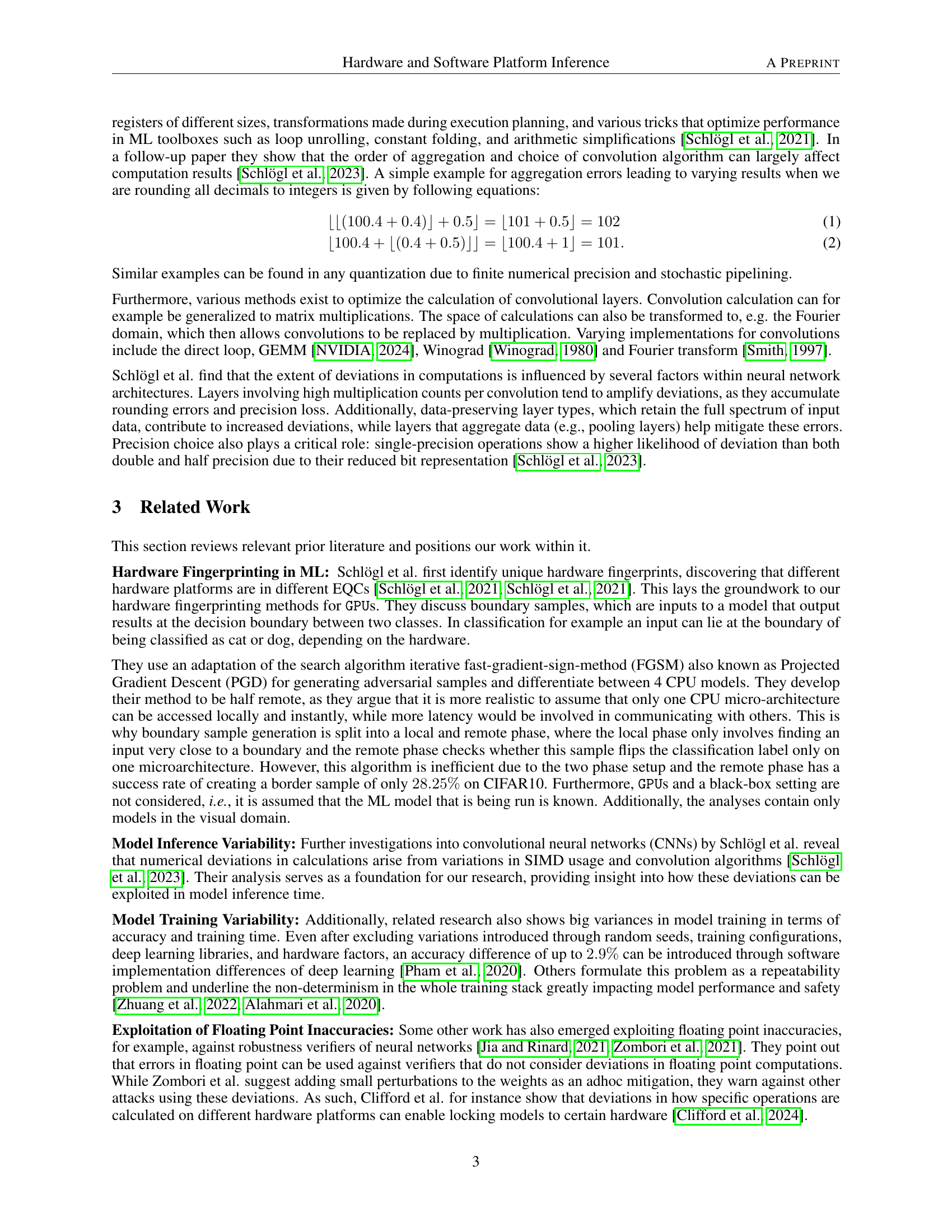

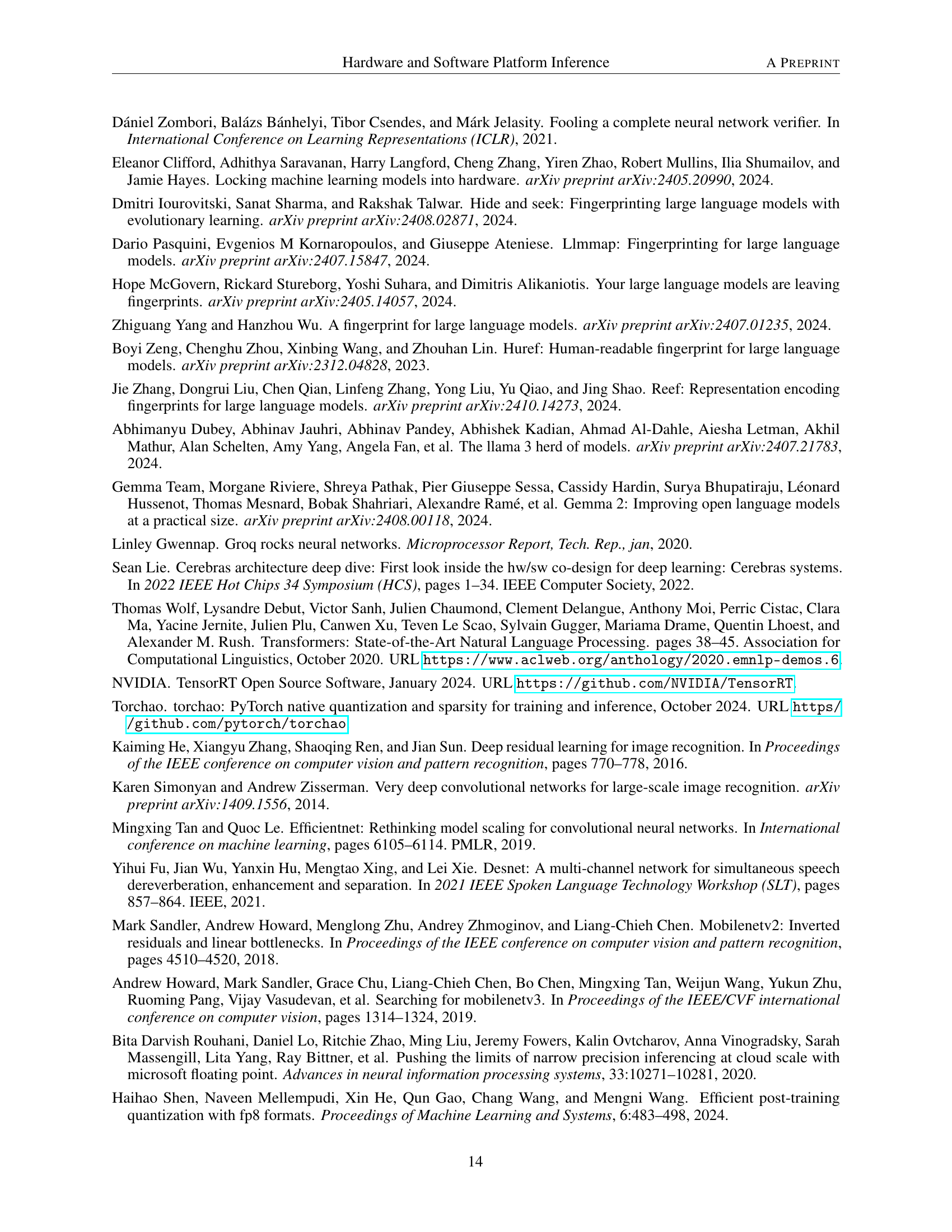

🔼 This figure illustrates how a single-precision 32-bit floating-point number (FP32), representing a logit from a neural network, is converted into three 32-bit integer numbers (INT32). The process involves separating the logit’s sign, exponent, and fractional parts. Each part is then zero-padded to ensure it’s a full 32 bits, and each is treated as a separate integer. This is done to address the issue of rounding noise that may be present in FP32 numbers. By separating the components, the impact of this rounding noise on the overall bit distribution is reduced. This pre-processing step is performed before training Support Vector Machines (SVMs), likely to improve the accuracy of the classification task.

read the caption

Figure 2: Splitting an FP32 logit into three INT32 numbers. In case that rounding noise pollutes the bit distribution in FP32 logits, before training SVMs, for each logit, we extract the sign, exponent, and fraction, zero pad each component and view each as an integer.

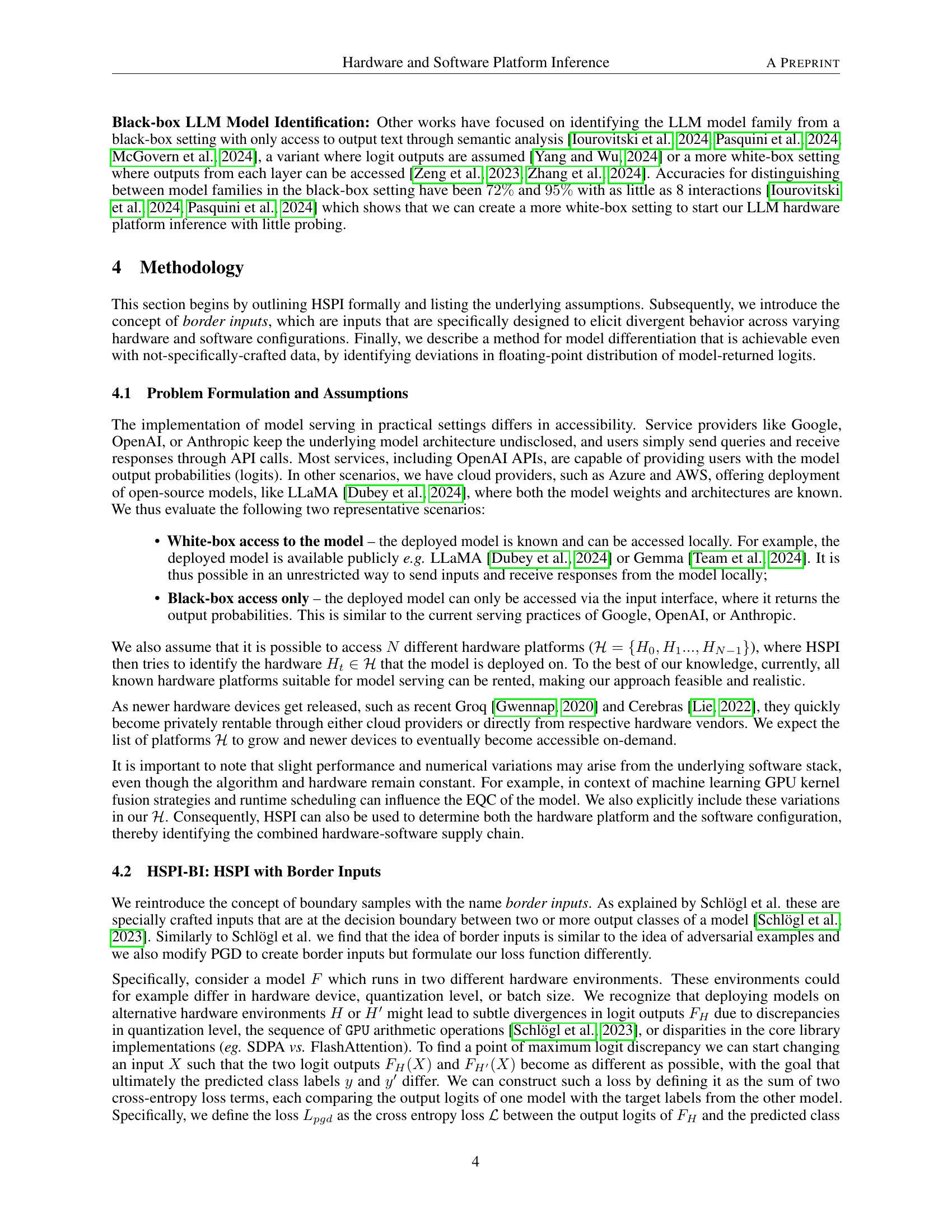

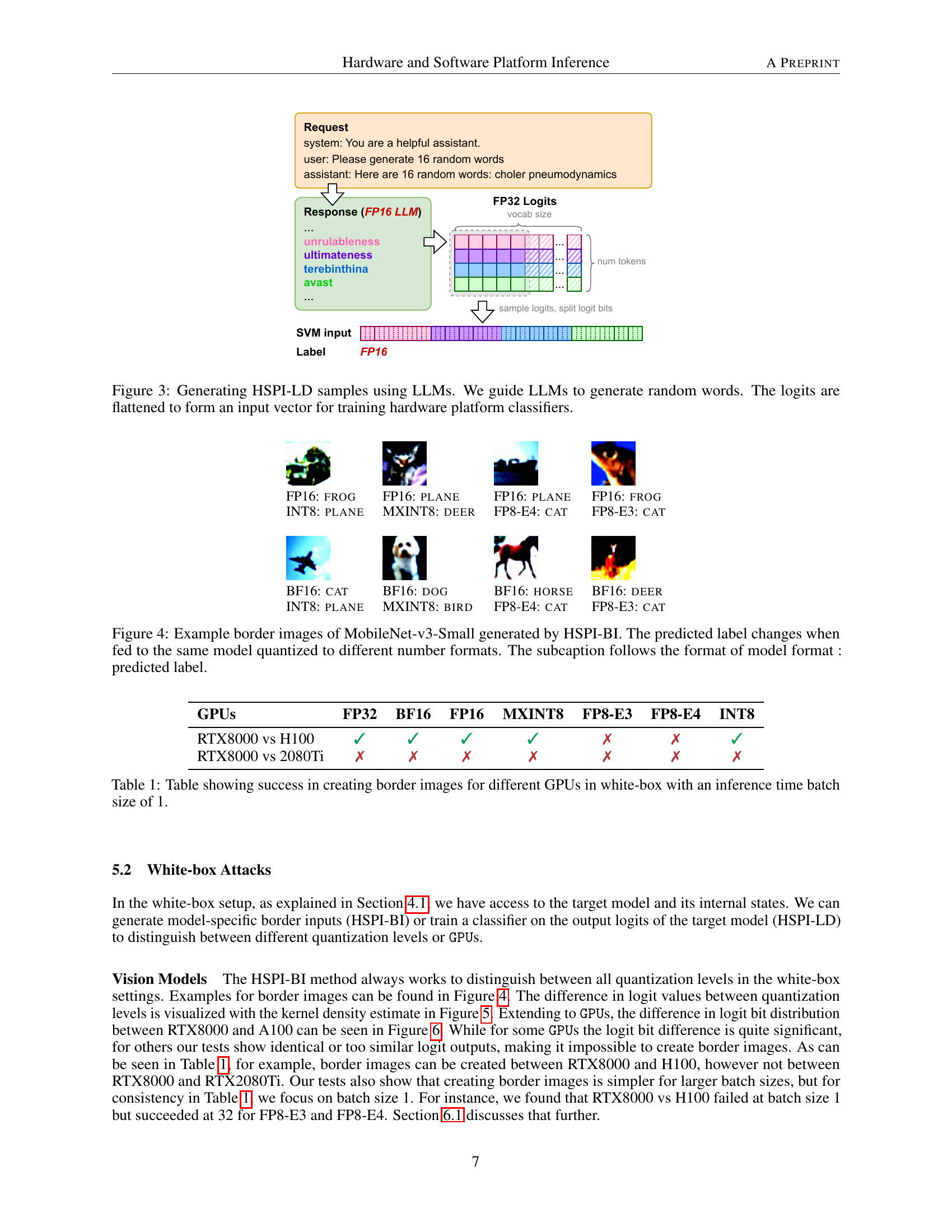

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of generating samples for Hardware and Software Platform Inference using Logits Distributions (HSPI-LD) with Large Language Models (LLMs). The process involves prompting an LLM to produce a sequence of random words. The model’s output includes the generated words and their associated logits (the pre-softmax probabilities of each word). These logits are then flattened into a single vector, which serves as the input data for training a classifier. This classifier is designed to distinguish between different hardware and software configurations based on the unique patterns in the logit distributions.

read the caption

Figure 3: Generating HSPI-LD samples using LLMs. We guide LLMs to generate random words. The logits are flattened to form an input vector for training hardware platform classifiers.

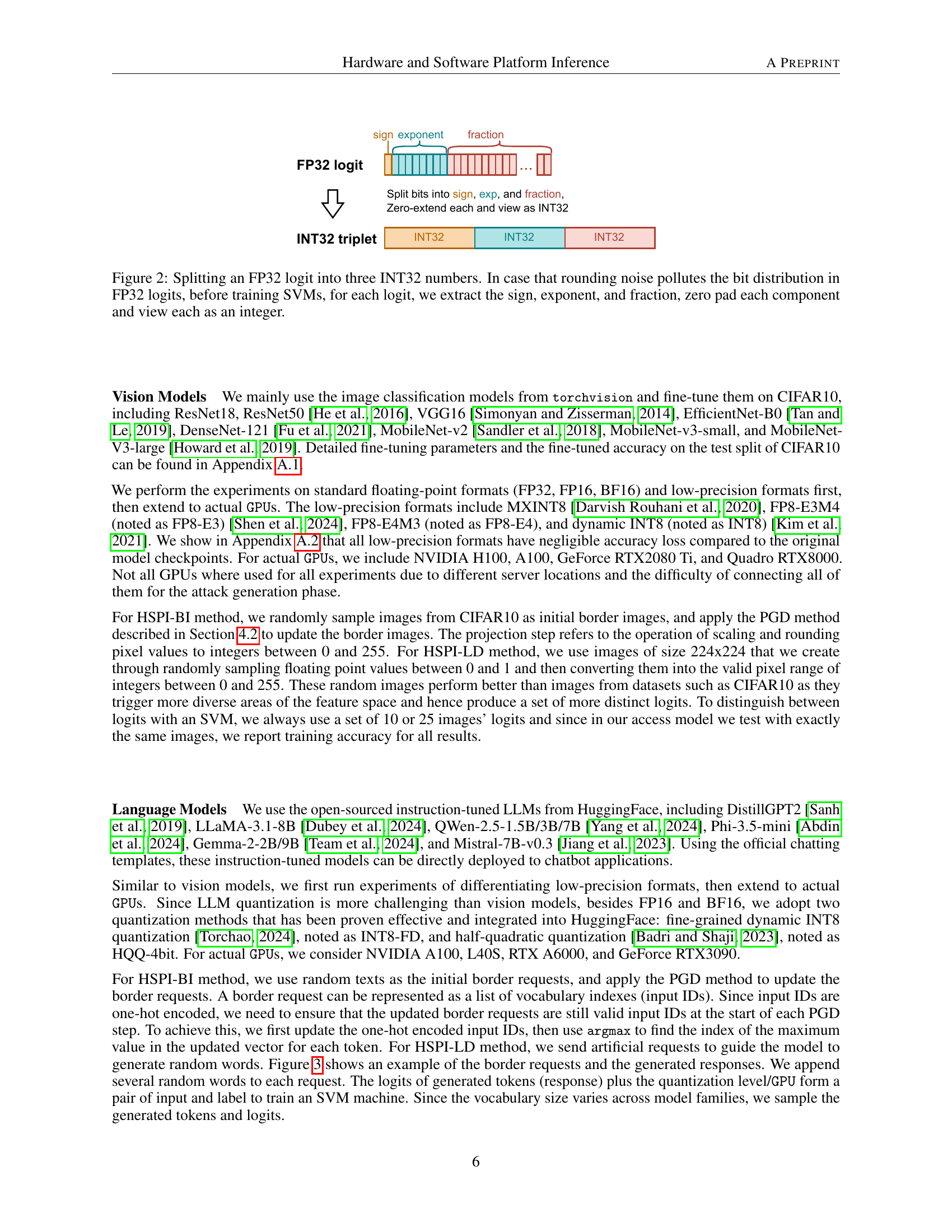

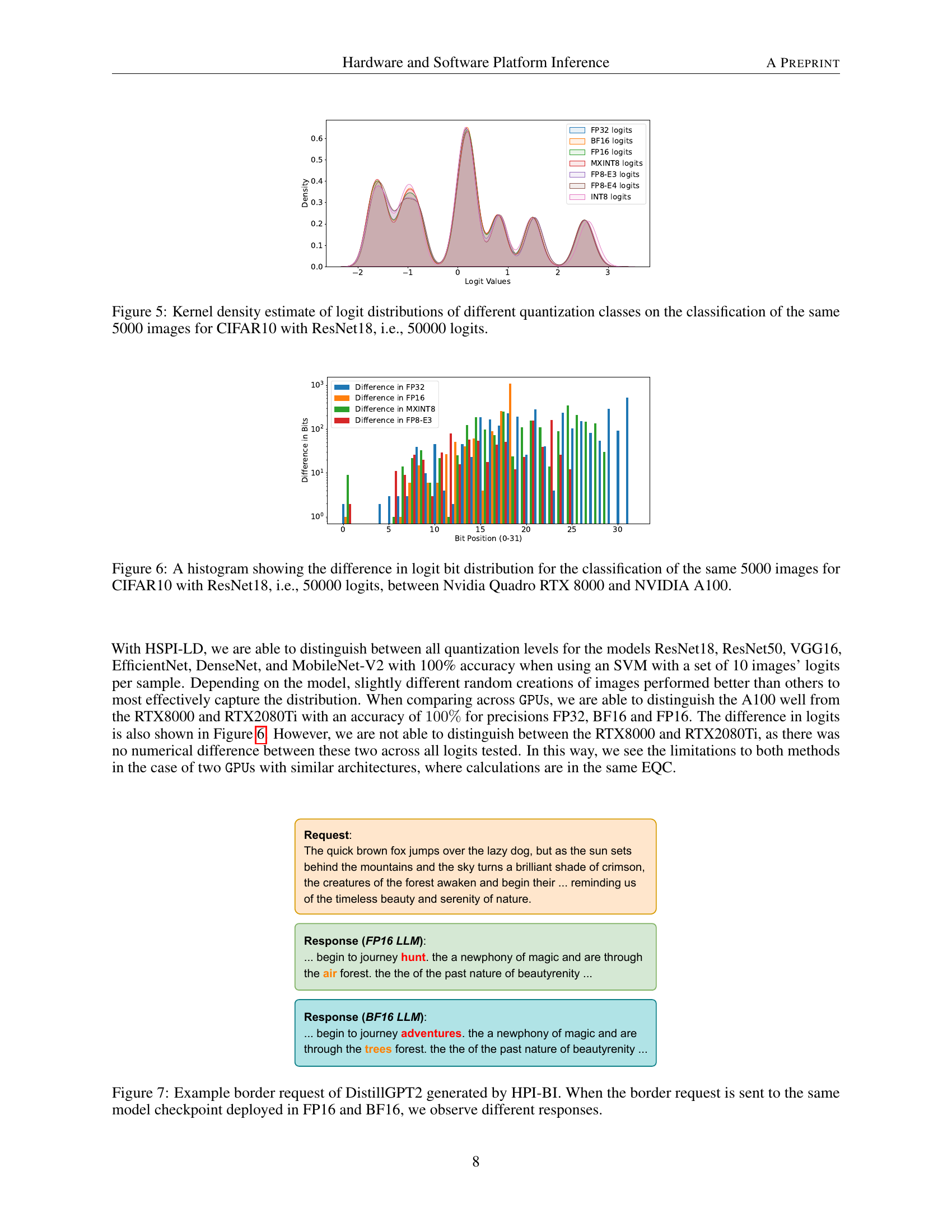

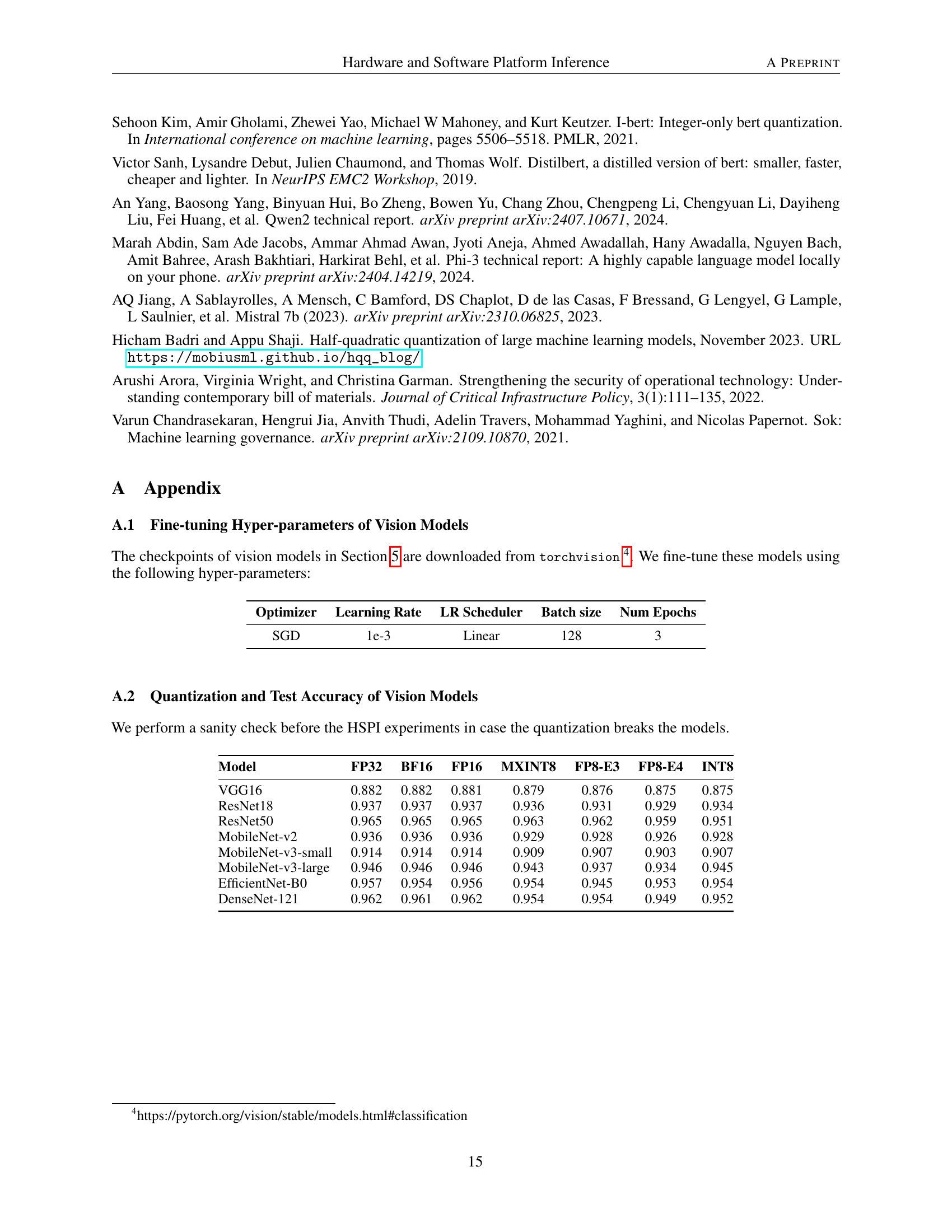

🔼 This figure shows example border images generated using the HSPI-BI method for MobileNet-v3-Small model. Each image is an input that causes the model to predict different classes when the model is quantized to different numerical precision formats (FP16, INT8, MXINT8, BF16, FP8-E3, FP8-E4). The format of each image’s subcaption indicates the quantization format used and the resulting prediction (e.g., ‘FP16: FROG’ denotes that when using FP16 quantization, the model predicts ‘FROG’). This demonstrates how subtle differences in numerical precision due to quantization can lead to different model outputs, making it possible to infer hardware and software platform information based on the model’s input-output behavior.

read the caption

Figure 4: Example border images of MobileNet-v3-Small generated by HSPI-BI. The predicted label changes when fed to the same model quantized to different number formats. The subcaption follows the format of model format : predicted label.

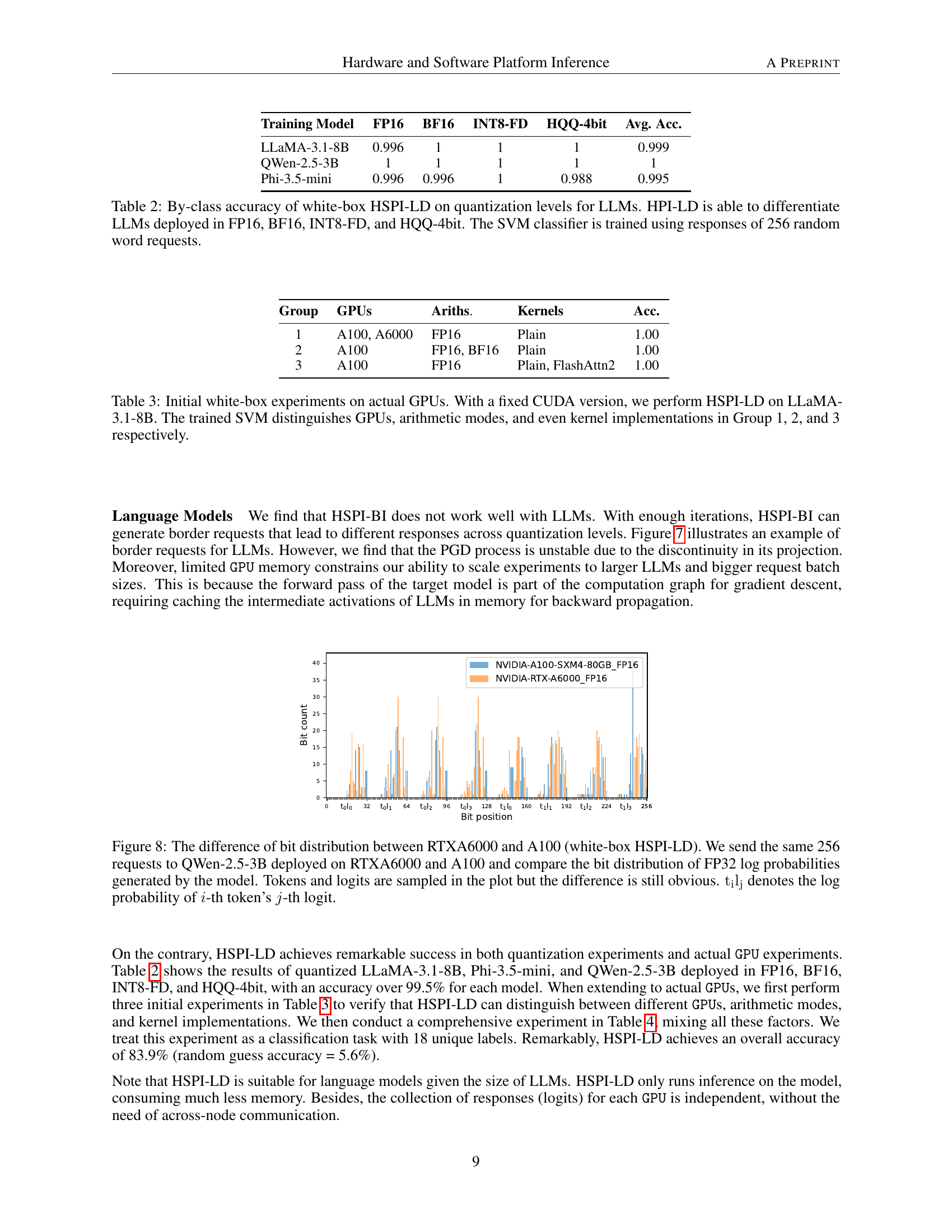

🔼 This figure displays kernel density estimates of the logit distributions for seven different quantization methods (FP32, BF16, FP16, MXINT8, FP8-E3, FP8-E4, INT8). Each distribution represents the logits obtained when classifying the same 5000 images from the CIFAR-10 dataset using a ResNet18 model. This results in a total of 50000 logits across all the quantization methods. The purpose of the figure is to visually illustrate the subtle but distinct differences in logit distributions introduced by various quantization techniques, which forms the basis for Hardware and Software Platform Inference (HSPI) in the paper. The visual comparison shows how these differing distributions can be used to differentiate between various hardware and software configurations.

read the caption

Figure 5: Kernel density estimate of logit distributions of different quantization classes on the classification of the same 5000 images for CIFAR10 with ResNet18, i.e., 50000 logits.

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comparative analysis of logit bit distribution between two NVIDIA GPUs: the Quadro RTX 8000 and the A100. The analysis is based on the classification of 5000 images from the CIFAR-10 dataset using the ResNet18 model, resulting in a total of 50,000 logits. The histogram visualizes the differences in the distribution of bits across the logit values, highlighting how the two GPUs process and represent numerical data differently. This difference in bit distribution is a key aspect of the paper’s method for inferring hardware and software platform information solely from a model’s input-output behavior.

read the caption

Figure 6: A histogram showing the difference in logit bit distribution for the classification of the same 5000 images for CIFAR10 with ResNet18, i.e., 50000 logits, between Nvidia Quadro RTX 8000 and NVIDIA A100.

🔼 Figure 7 shows an example of a ‘border request’ generated using the HSPI-BI method. Border requests are specifically designed inputs that cause a model to produce different outputs based on subtle differences in its hardware or software environment (different quantization formats in this case). The figure demonstrates that when the same border request is sent to a DistillGPT2 model running with FP16 (half-precision floating point) and BF16 (brain floating point 16) quantization, the model’s responses (the generated text) differ. This difference highlights the sensitivity of model outputs to even small variations in underlying hardware and software configurations, demonstrating the feasibility of using these differences to infer details about the platform on which the model is running.

read the caption

Figure 7: Example border request of DistillGPT2 generated by HPI-BI. When the border request is sent to the same model checkpoint deployed in FP16 and BF16, we observe different responses.

🔼 Figure 8 illustrates the differences in bit distribution between the log probabilities generated by the QWen-2.5-3B language model running on two different GPUs, the RTX A6000 and the A100. The experiment uses the HSPI-LD (Hardware and Software Platform Inference with Logits Distributions) method. Identical input requests (256 in total) were sent to the model on both GPUs. The resulting FP32 log probabilities are analyzed for bit-level differences. Although only a sample of tokens and logits are shown in the plot, the figure clearly shows distinct differences in bit distribution across the two GPU platforms, demonstrating that even subtle hardware differences can manifest in the model’s output.

read the caption

Figure 8: The difference of bit distribution between RTXA6000 and A100 (white-box HSPI-LD). We send the same 256 requests to QWen-2.5-3B deployed on RTXA6000 and A100 and compare the bit distribution of FP32 log probabilities generated by the model. Tokens and logits are sampled in the plot but the difference is still obvious. tiljsubscripttisubscriptlj\mathrm{t_{i}l_{j}}roman_t start_POSTSUBSCRIPT roman_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT roman_l start_POSTSUBSCRIPT roman_j end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denotes the log probability of i𝑖iitalic_i-th token’s j𝑗jitalic_j-th logit.

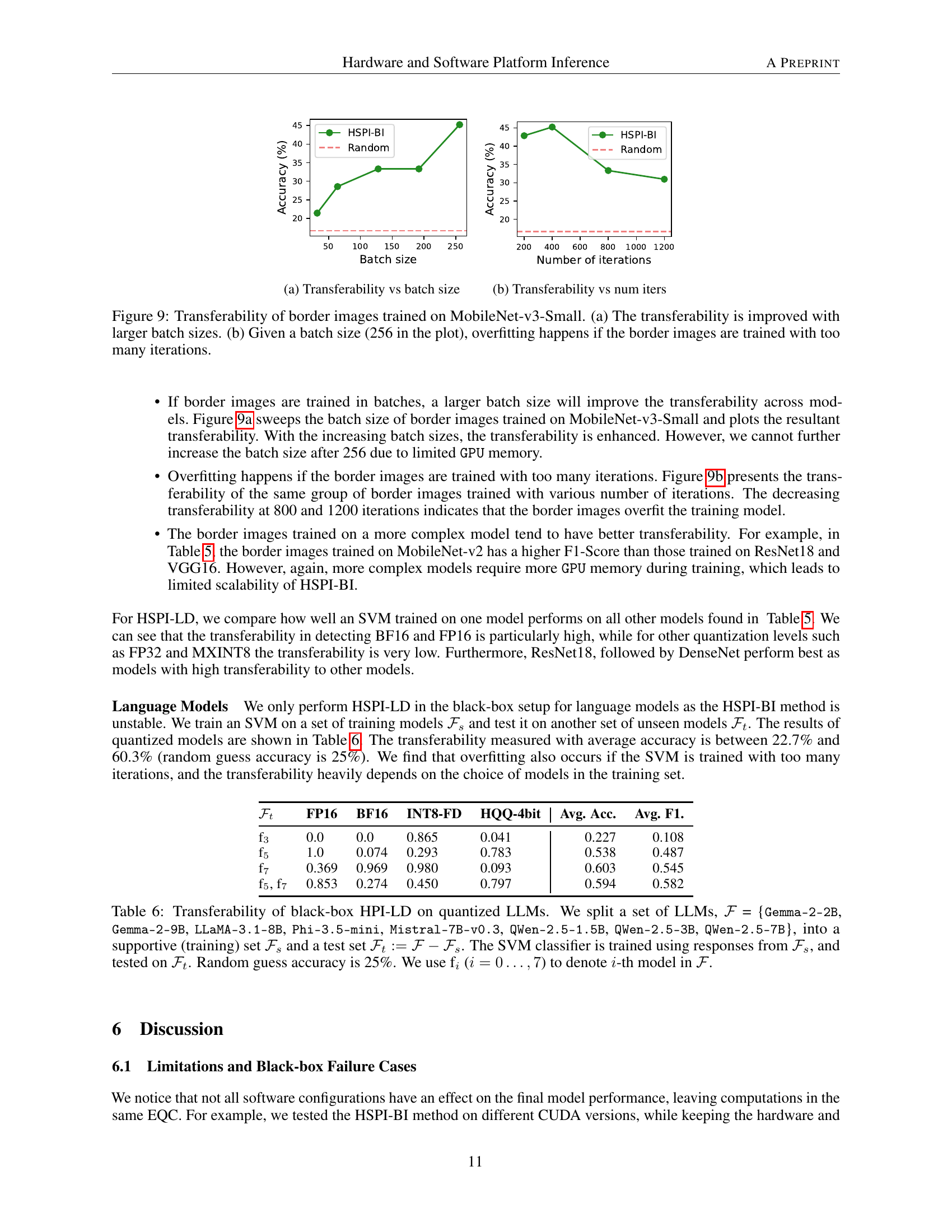

🔼 This figure shows how the transferability of border images is affected by the batch size used during their training. Transferability refers to the ability of border images, trained on one model, to successfully distinguish between different hardware/software configurations when applied to other models. The x-axis represents the batch size, and the y-axis represents the transferability accuracy (presumably F1-score). The plot shows an improvement in transferability with increasing batch sizes, up to a certain point after which the improvement plateaus or diminishes. This suggests that larger batch sizes may help generalize the features of the border images, improving their ability to discriminate across different model setups. However, increasing the batch size beyond a certain point may not yield additional benefits or could even lead to reduced performance.

read the caption

(a) Transferability vs batch size

Full paper#