↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current large language models (LLMs) often generate inaccurate information, a problem known as ‘hallucination’. Evaluating an LLM’s factuality is challenging because these models often provide lengthy responses. Existing English-language benchmarks are insufficient for assessing LLMs across languages. Thus, there is a need for reliable, language-specific benchmarks to properly evaluate LLMs’ factuality.

This paper introduces Chinese SimpleQA, the first comprehensive benchmark for evaluating the factuality of Chinese LLMs. It includes 3000 high-quality questions across six major topics, with a focus on short questions and answers to make evaluation easier. The study finds that larger models generally perform better and shows that the Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) strategy is highly effective in enhancing the accuracy of LLMs in answering factually-based questions. Chinese SimpleQA addresses the gap in Chinese LLM evaluation and offers a valuable tool for developers and researchers.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) and focusing on factuality. It addresses the critical need for language-specific evaluation benchmarks, particularly in Chinese, a language with a vast and complex linguistic landscape. By providing a robust, high-quality benchmark like Chinese SimpleQA, the paper enables researchers to better understand the limitations of LLMs, facilitates the development of more accurate and reliable models, and opens up new avenues of research in cross-lingual LLM evaluation and factual knowledge representation.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure is a sunburst chart visualizing the distribution of questions across different categories in the Chinese SimpleQA benchmark. The outermost ring displays the six main topics: Chinese Culture, Humanities, Engineering, Technology, and Applied Sciences (ETAS), Life, Art, and Culture, Society, and Natural Science. Each main topic is further broken down into multiple subtopics in the subsequent inner rings, showing the hierarchical structure of the dataset. The size of each segment is proportional to the number of questions within that category, providing a visual representation of the dataset’s composition across various subject areas.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of Chinese SimpleQA. “Chinese Cul.” and “ETAS” represent “Chinese Culture” and “Engineering, Technology, and Applied Sciences”, respectively.

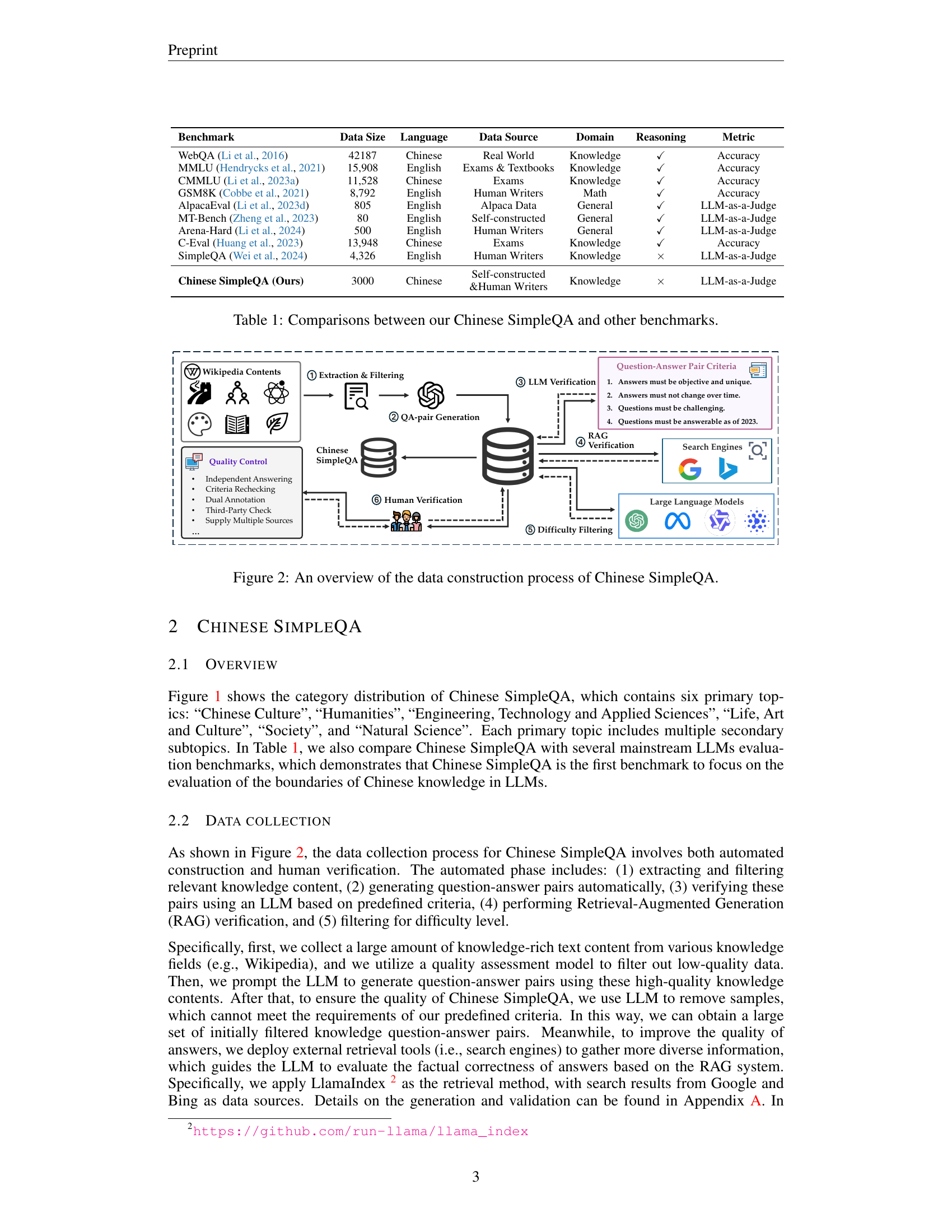

| Benchmark | Data Size | Language | Data Source | Domain | Reasoning | Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WebQA (Li et al., 2016) | 42187 | Chinese | Real World | Knowledge | ✓ | Accuracy |

| MMLU (Hendrycks et al., 2021) | 15,908 | English | Exams & Textbooks | Knowledge | ✓ | Accuracy |

| CMMLU (Li et al., 2023a) | 11,528 | Chinese | Exams | Knowledge | ✓ | Accuracy |

| GSM8K (Cobbe et al., 2021) | 8,792 | English | Human Writers | Math | ✓ | Accuracy |

| AlpacaEval (Li et al., 2023d) | 805 | English | Alpaca Data | General | ✓ | LLM-as-a-Judge |

| MT-Bench (Zheng et al., 2023) | 80 | English | Self-constructed | General | ✓ | LLM-as-a-Judge |

| Arena-Hard (Li et al., 2024) | 500 | English | Human Writers | General | ✓ | LLM-as-a-Judge |

| C-Eval (Huang et al., 2023) | 13,948 | Chinese | Exams | Knowledge | ✓ | Accuracy |

| SimpleQA (Wei et al., 2024) | 4,326 | English | Human Writers | Knowledge | × | LLM-as-a-Judge |

| Chinese SimpleQA (Ours) | 3000 | Chinese | Self-constructed & Human Writers | Knowledge | × | LLM-as-a-Judge |

🔼 This table compares the characteristics of Chinese SimpleQA with those of other prominent large language model (LLM) evaluation benchmarks. The comparison includes data size, language, data sources, domains covered, reasoning types required, and the evaluation metrics used. This allows for a clear understanding of how Chinese SimpleQA differs from and builds upon existing benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparisons between our Chinese SimpleQA and other benchmarks.

In-depth insights#

Chinese Factuality#

The concept of “Chinese Factuality” in the context of large language models (LLMs) is a crucial area of research, highlighting the unique challenges and opportunities presented by the Chinese language. Unlike English, which boasts a vast amount of readily available, high-quality data for training and evaluation, Chinese presents complexities such as diverse dialects, writing systems, and cultural nuances. This necessitates the development of specialized benchmarks, like the one introduced in the paper, to accurately assess the factual accuracy of LLMs. Chinese SimpleQA serves as a vital tool in this endeavor, offering a comprehensive evaluation framework specifically designed for the Chinese language. It’s important to note that factuality assessment isn’t merely about accuracy; it also considers the model’s calibration and confidence levels. A model that consistently produces correct answers yet exhibits a low confidence score needs further development. This further emphasizes the significance of benchmarks such as Chinese SimpleQA in advancing the understanding and improvement of LLMs for Chinese language tasks, ultimately contributing to more reliable and trustworthy AI applications in a culturally sensitive manner. The development of such benchmarks is critical to bridging the gap between technological advancement and the specific needs of diverse linguistic communities.

LLM Evaluation#

LLM evaluation is a critical area of research, as the capabilities and limitations of Large Language Models (LLMs) are constantly evolving. Robust evaluation methods are crucial for ensuring that LLMs are developed responsibly and deployed effectively. Current benchmarks often focus on specific tasks, such as question answering or text generation, which can reveal certain strengths and weaknesses but may not capture the full spectrum of LLM capabilities. A holistic approach is needed that integrates multiple evaluation criteria, including factuality, coherence, bias, and toxicity. Furthermore, the context in which LLMs are used should be considered, as performance may vary significantly depending on the application. The development of new and diverse benchmarks is essential to address these challenges and guide further improvements in LLM technology. Finally, the emphasis should be placed on moving beyond simple metrics towards more nuanced qualitative assessments that better capture the subtle aspects of language understanding and generation.

Benchmark Design#

Effective benchmark design for large language models (LLMs) is crucial for evaluating factuality. A strong benchmark should be comprehensive, covering diverse topics and subtopics to ensure broad evaluation. High-quality data is paramount; this means questions and answers must be carefully curated, unambiguous, and resistant to changes over time. A well-designed benchmark also needs to be easily evaluatable, preferably with automated scoring mechanisms to reduce human bias and increase efficiency. The language of the benchmark is vital; a focus on a specific language allows for a nuanced understanding of LLM abilities within that context. Finally, a good benchmark facilitates detailed analysis. By examining performance across various topics and question types, researchers can gain valuable insights into an LLM’s strengths and weaknesses, guiding future development and improvement of these powerful models. A balanced approach, combining automated processes with human verification, is crucial to minimize errors and maximize reliability.

Model Analysis#

A thorough model analysis section in a research paper would delve into a comprehensive evaluation of the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on a newly proposed benchmark. It would not only present the results but also interpret the findings, discussing the strengths and weaknesses of each model and identifying trends across different model architectures or sizes. Key aspects such as accuracy, calibration, and efficiency would be analyzed, potentially with breakdowns across different subtopics within the benchmark to uncover nuanced performance patterns. Statistical significance would be considered when comparing models, ensuring that observed differences are not simply due to random variation. Furthermore, a strong analysis would correlate performance with model characteristics (e.g., size, training data, architecture), providing insights into the factors that contribute to successful factuality in LLMs and highlighting areas for future model improvement. Finally, the analysis should compare the findings to existing research on factuality in LLMs, positioning the new benchmark results within the broader context of the field and offering valuable insights for the LLM community.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from the Chinese SimpleQA benchmark could significantly advance the field of large language model (LLM) evaluation. Extending the benchmark to encompass a wider array of question types and complexities is crucial, moving beyond simple factual recall to include more nuanced reasoning and inferential tasks. This might involve incorporating multi-hop questions, requiring models to integrate information from multiple sources, or questions demanding common sense reasoning. Improving the diversity of the dataset by increasing its coverage of less-represented topics and dialects would bolster its robustness. Furthermore, investigating the interplay between model architecture and factuality performance on Chinese SimpleQA would be valuable, potentially revealing design choices that improve factual accuracy in LLMs. Exploring the integration of external knowledge sources and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) strategies more thoroughly, and analyzing their impact on both accuracy and calibration is needed. Finally, a key area for future work is to conduct cross-lingual comparisons with existing English-language benchmarks to understand the unique challenges posed by Chinese and potentially identify areas for improvement in multilingual LLMs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

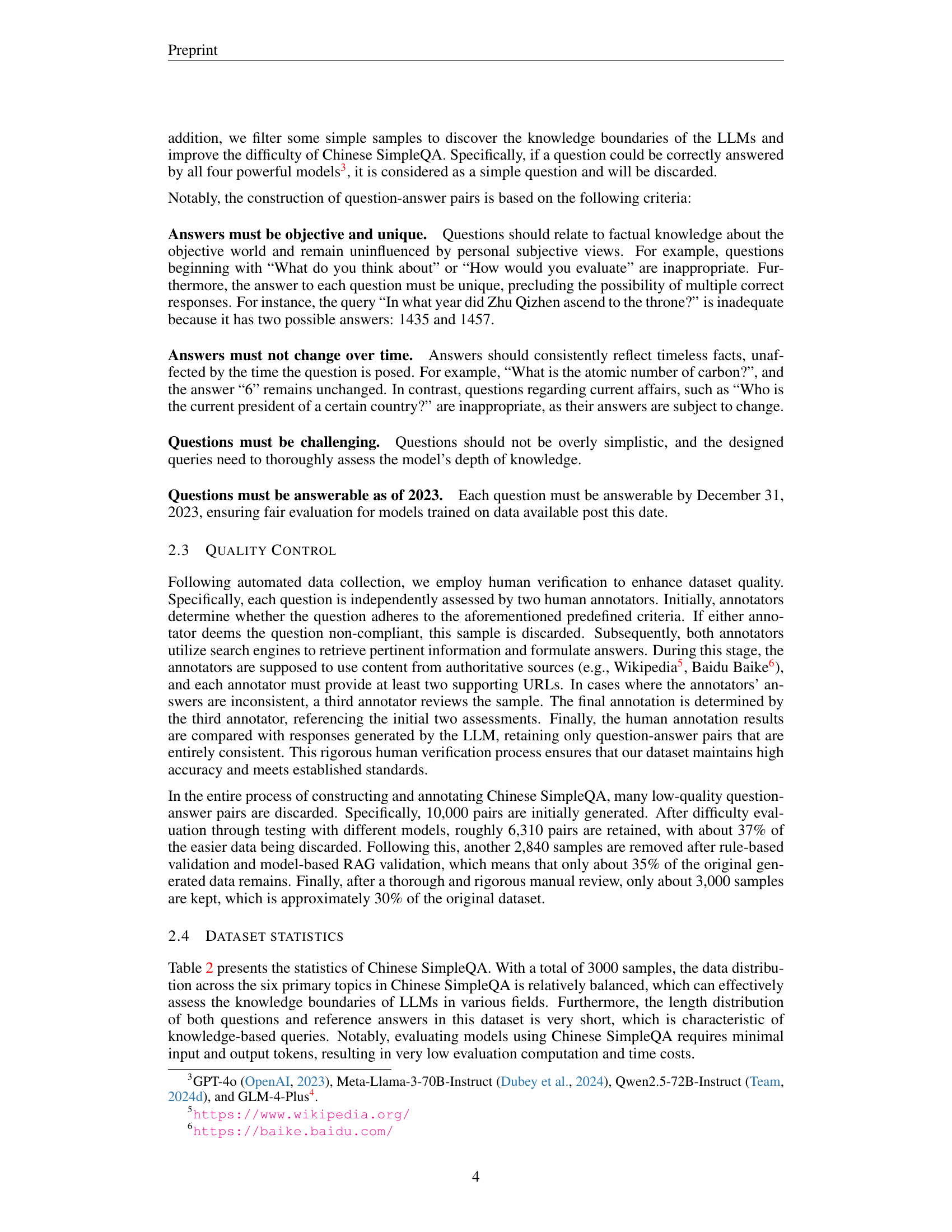

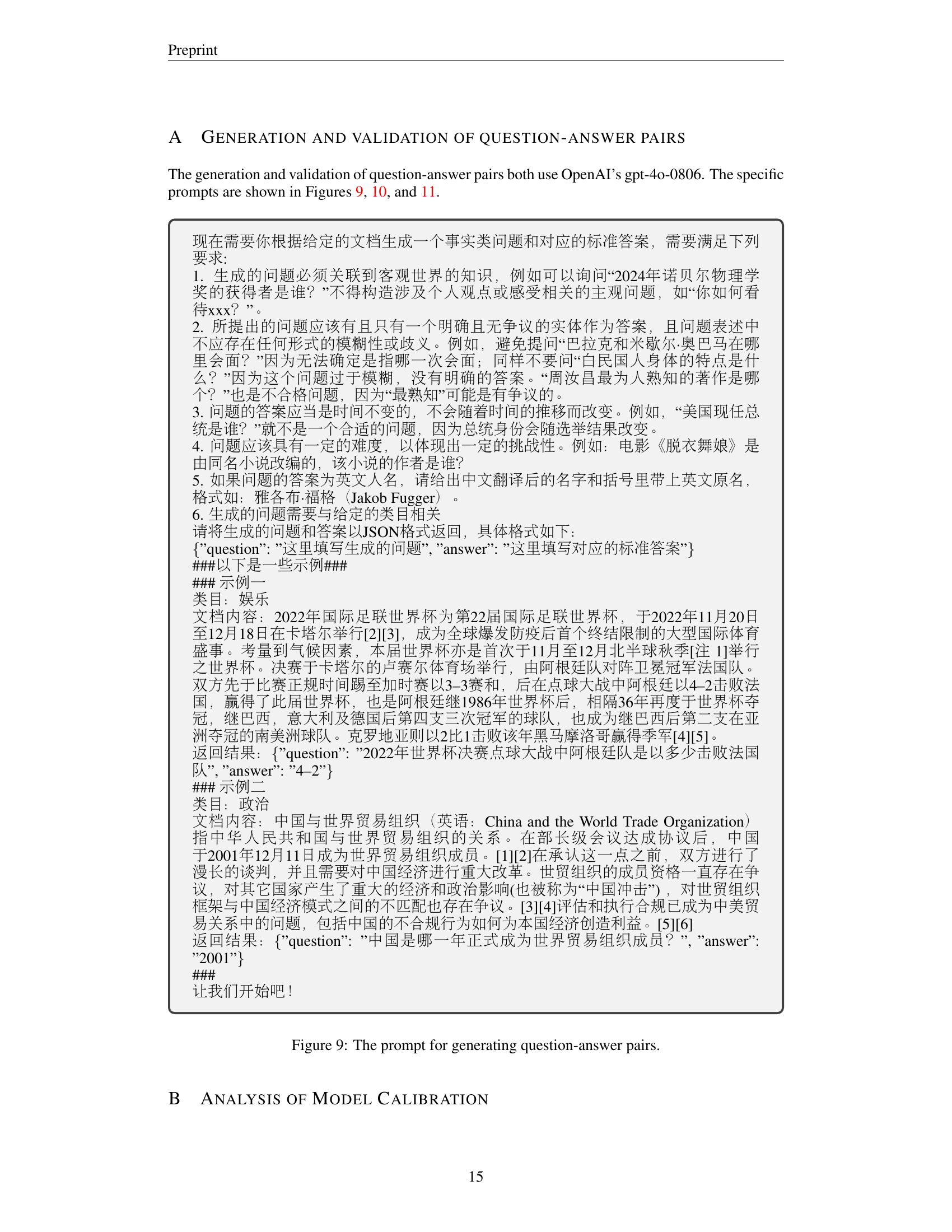

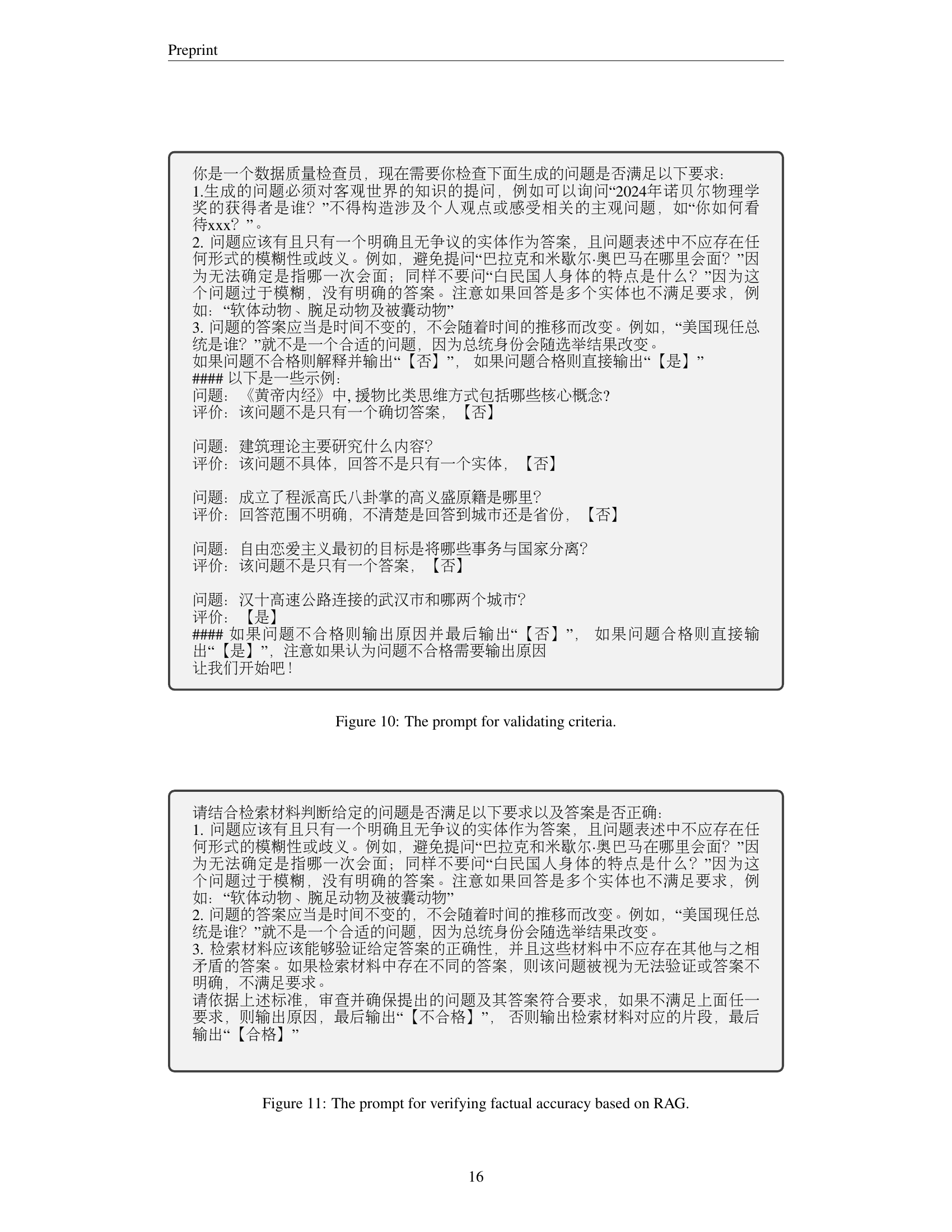

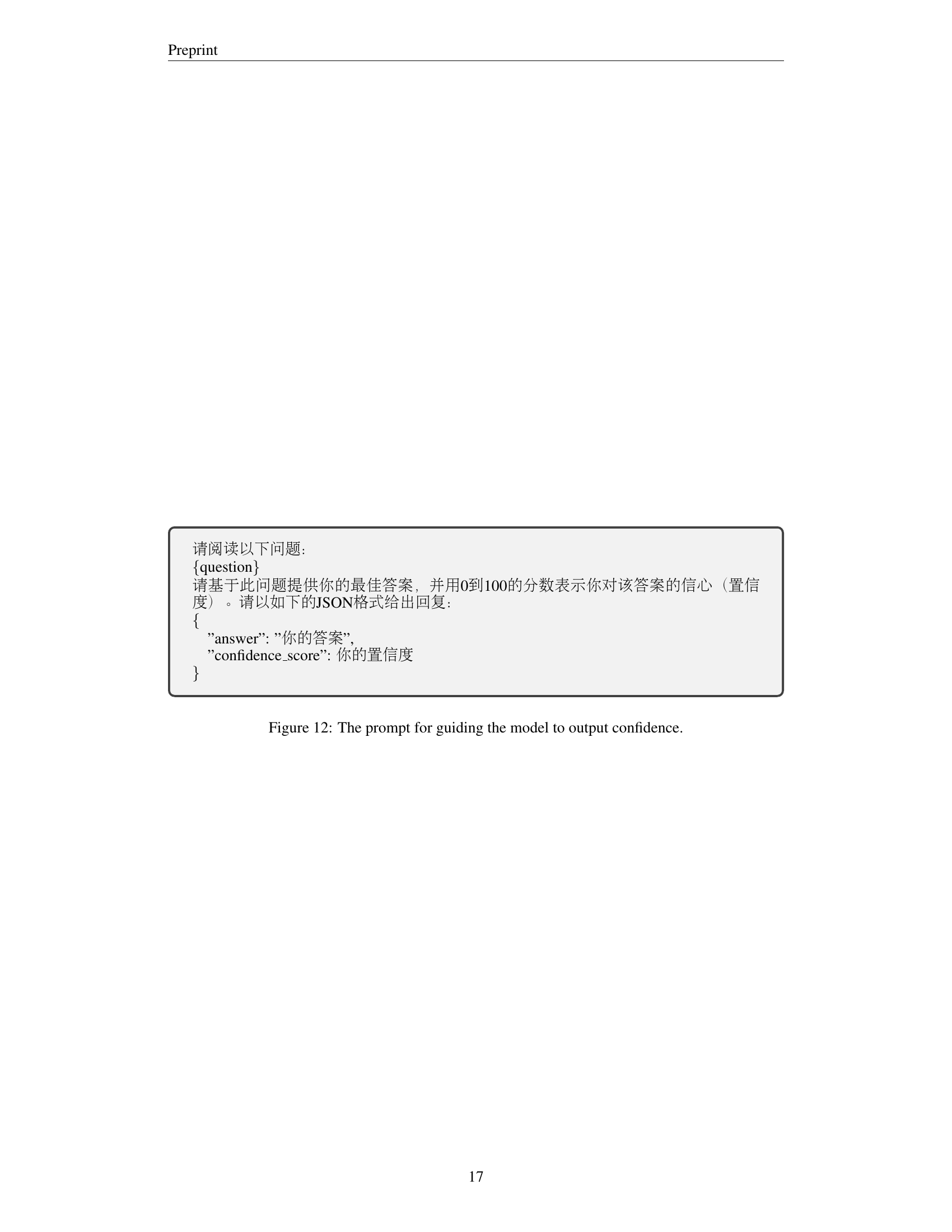

🔼 This figure details the creation of the Chinese SimpleQA dataset. It begins with extracting and filtering relevant content from sources like Wikipedia. Next, question-answer pairs are automatically generated using an LLM and then undergo quality control steps. These include verifying the pairs against predefined criteria, using a retrieval augmented generation (RAG) approach with search engine data to validate answers, and finally, human review and filtering for difficulty. The entire process aims to create high-quality, objective, and time-invariant question-answer pairs that effectively test the factuality of LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 2: An overview of the data construction process of Chinese SimpleQA.

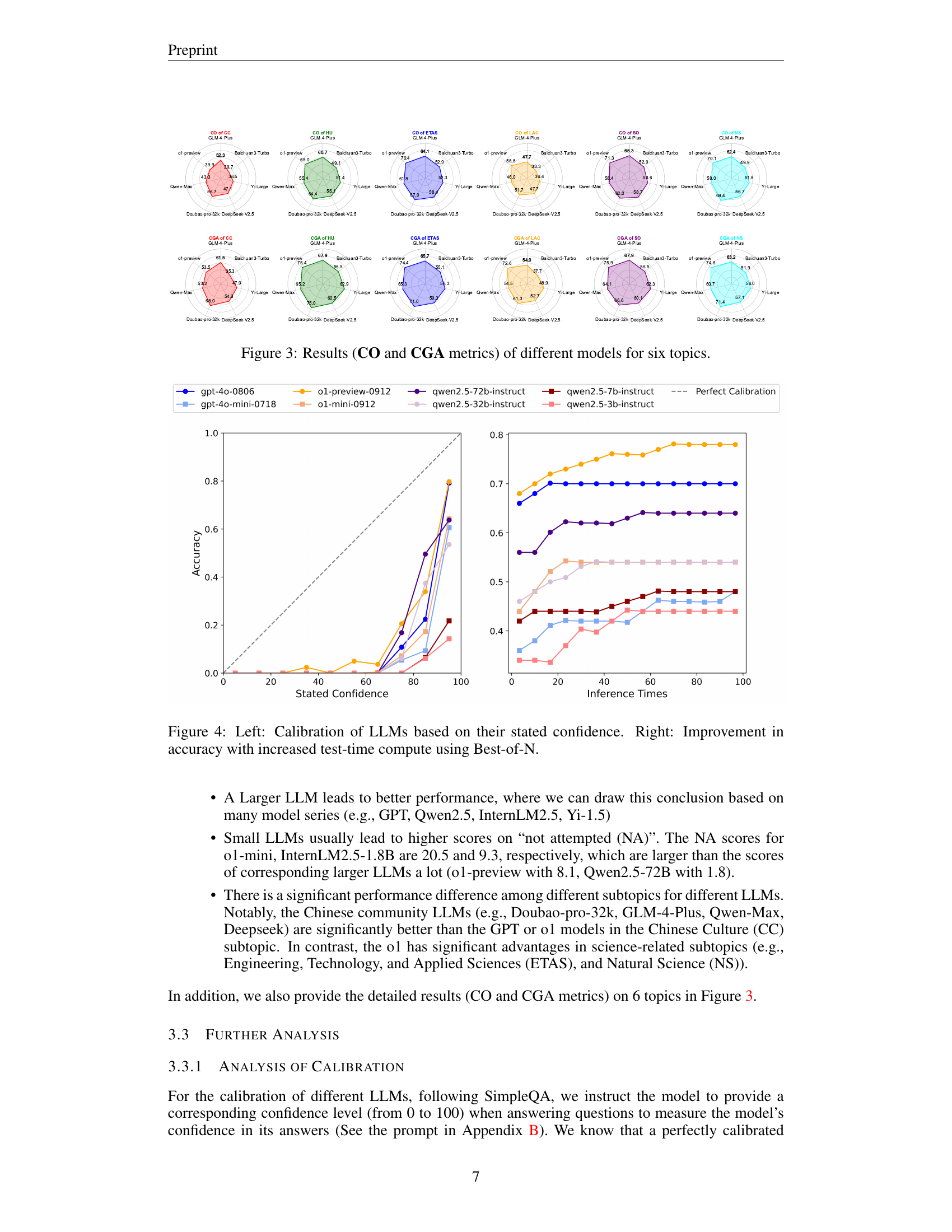

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the performance of various large language models (LLMs) across six primary topics, as measured by two metrics: Correct (CO) and Correct Given Attempted (CGA). The six topics represent broad subject categories from the Chinese SimpleQA benchmark dataset, allowing for an assessment of the models’ factual accuracy and knowledge breadth across different domains. Each model’s performance is visually displayed for each topic, allowing for a direct comparison between the models and across topic areas.

read the caption

Figure 3: Results (CO and CGA metrics) of different models for six topics.

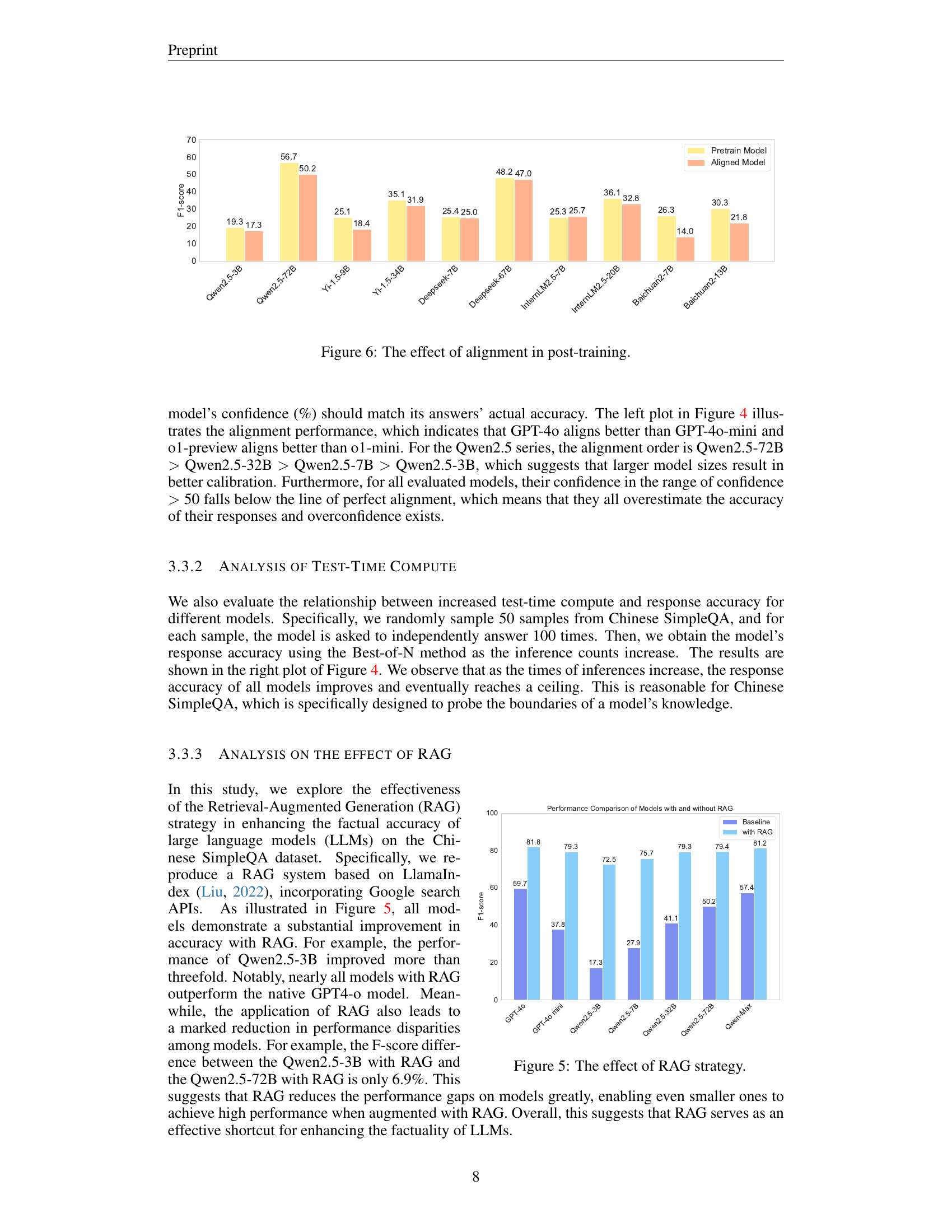

🔼 This figure shows two plots. The left plot displays the calibration of various Large Language Models (LLMs) based on their stated confidence levels. It assesses how well the models’ confidence scores match their actual accuracy in answering questions from the Chinese SimpleQA dataset. A perfectly calibrated model would have confidence scores that precisely reflect its accuracy rate. The right plot illustrates how the accuracy of LLMs improves as the number of inferences (test-time compute) increases using a Best-of-N strategy. Best-of-N involves running the model multiple times for each question and selecting the answer with the highest confidence. The improvement in accuracy demonstrates the effectiveness of this strategy.

read the caption

Figure 4: Left: Calibration of LLMs based on their stated confidence. Right: Improvement in accuracy with increased test-time compute using Best-of-N.

🔼 The figure illustrates the impact of employing a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) strategy on the performance of various large language models (LLMs) when evaluated using the Chinese SimpleQA benchmark. The chart compares the F1-scores achieved by different LLMs with and without RAG. It demonstrates that incorporating RAG substantially enhances the accuracy of most LLMs, especially smaller models, and significantly reduces performance gaps between different LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 5: The effect of RAG strategy.

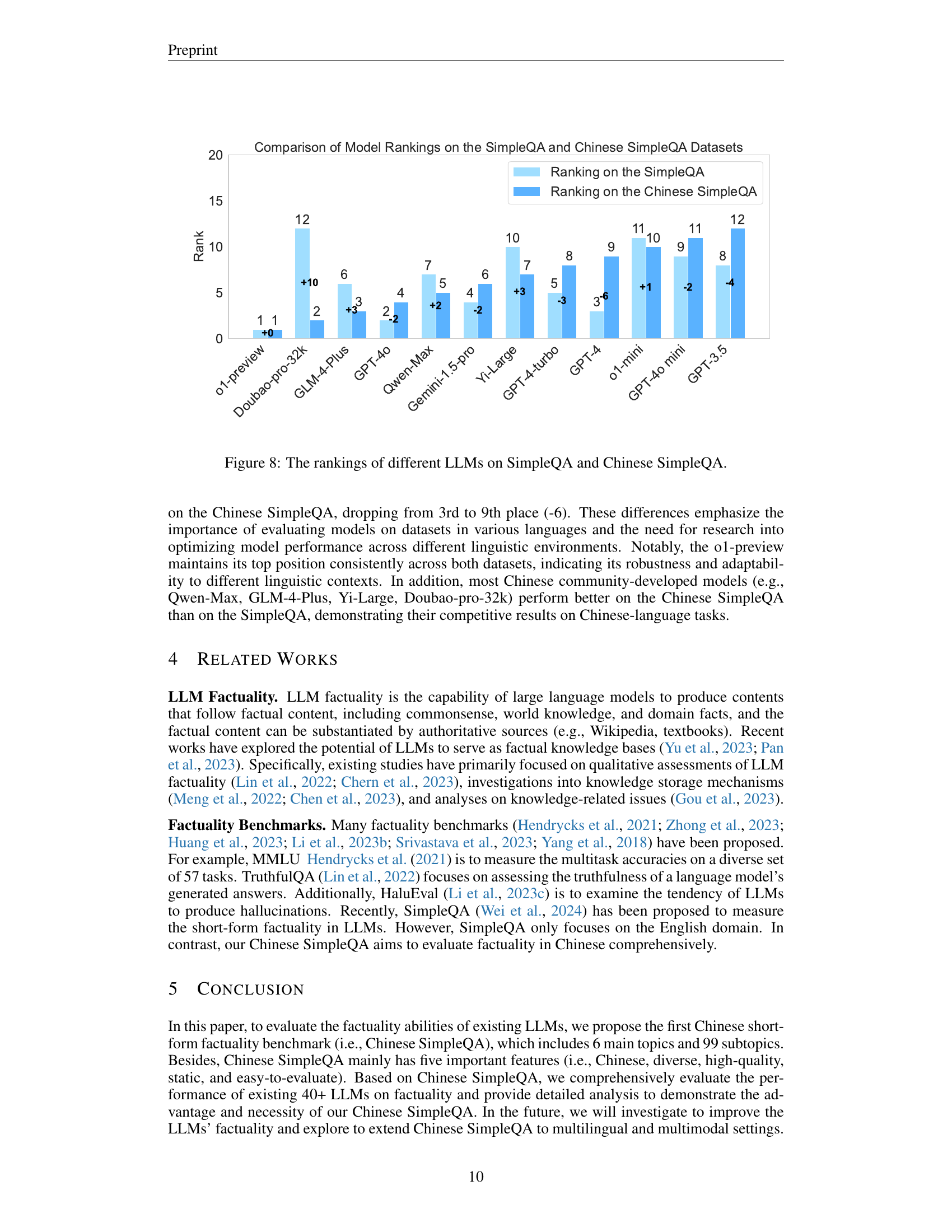

🔼 This figure shows the impact of alignment techniques (post-training) on the factuality of various LLMs. It compares the performance of pre-trained models versus their aligned counterparts across several models (Qwen2.5 series, DeepSeek, GPT-40). The bars represent the F1 score, a metric combining precision and recall, and visually demonstrate whether alignment improved or hurt the model’s factuality. The results indicate that alignment does not always improve factuality, highlighting what is known as the ‘alignment tax.’

read the caption

Figure 6: The effect of alignment in post-training.

🔼 This figure presents a detailed breakdown of the performance of various LLMs across six selected subtopics within the Chinese SimpleQA benchmark. The subtopics shown are Education, Entertainment, Mathematics, Medicine, Law, and Computer Science. Each model’s performance is visualized using a radar chart, comparing their correct answer rates (CO) across these diverse subject areas. This granular level of analysis allows for a deeper understanding of each model’s strengths and weaknesses in specific knowledge domains, moving beyond the overall scores.

read the caption

Figure 7: Detailed results on some selected subtopics.

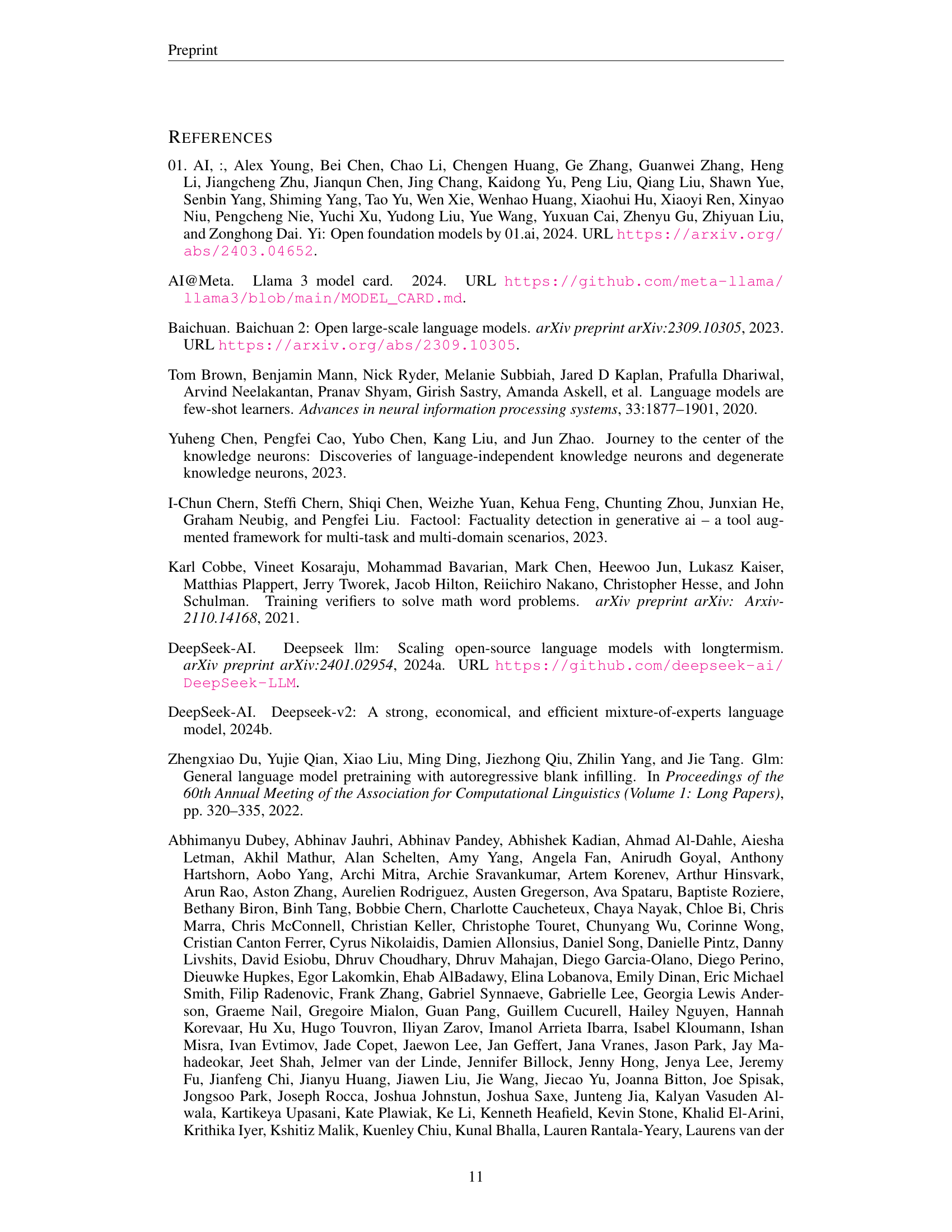

🔼 This figure compares the performance rankings of various large language models (LLMs) on two different question-answering benchmarks: SimpleQA (English) and Chinese SimpleQA (Chinese). It highlights the differences in model rankings between the two benchmarks, showing that the relative strengths of different models can vary significantly depending on the language and dataset used for evaluation. This underscores the importance of evaluating LLMs across diverse datasets to get a more comprehensive understanding of their capabilities and limitations.

read the caption

Figure 8: The rankings of different LLMs on SimpleQA and Chinese SimpleQA.

More on tables

| Self-constructed & Human Writers |

|---|

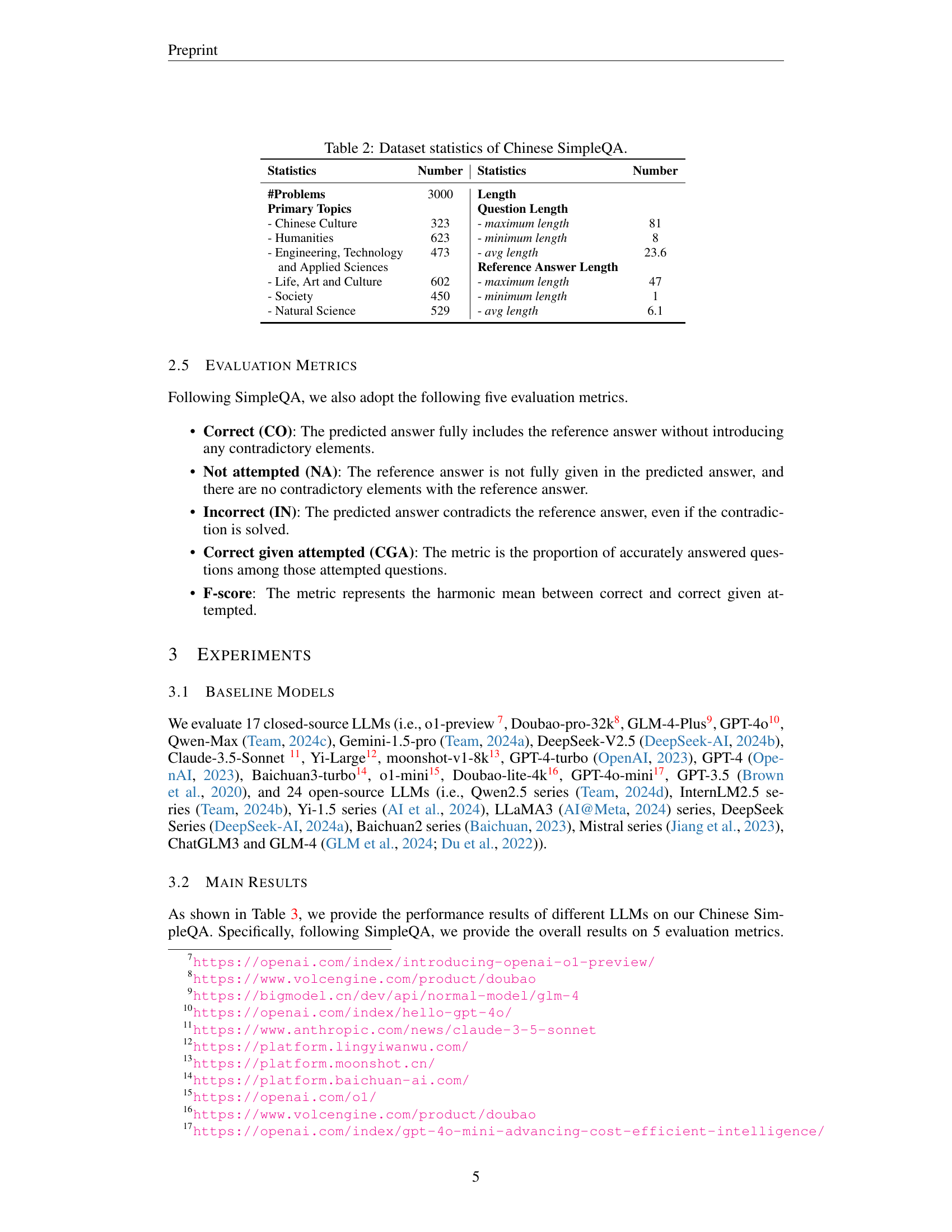

🔼 This table presents a statistical overview of the Chinese SimpleQA dataset, including the total number of problems, their distribution across six primary topics and their respective subtopics, and the length characteristics of both questions and answers.

read the caption

Table 2: Dataset statistics of Chinese SimpleQA.

| Statistics | Number | Statistics | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| #Problems | 3000 | Length | |

| Primary Topics | Question Length | ||

| - Chinese Culture | 323 | - maximum length | 81 |

| - Humanities | 623 | - minimum length | 8 |

| - Engineering, Technology | 473 | - avg length | 23.6 |

| and Applied Sciences | Reference Answer Length | ||

| - Life, Art and Culture | 602 | - maximum length | 47 |

| - Society | 450 | - minimum length | 1 |

| - Natural Science | 529 | - avg length | 6.1 |

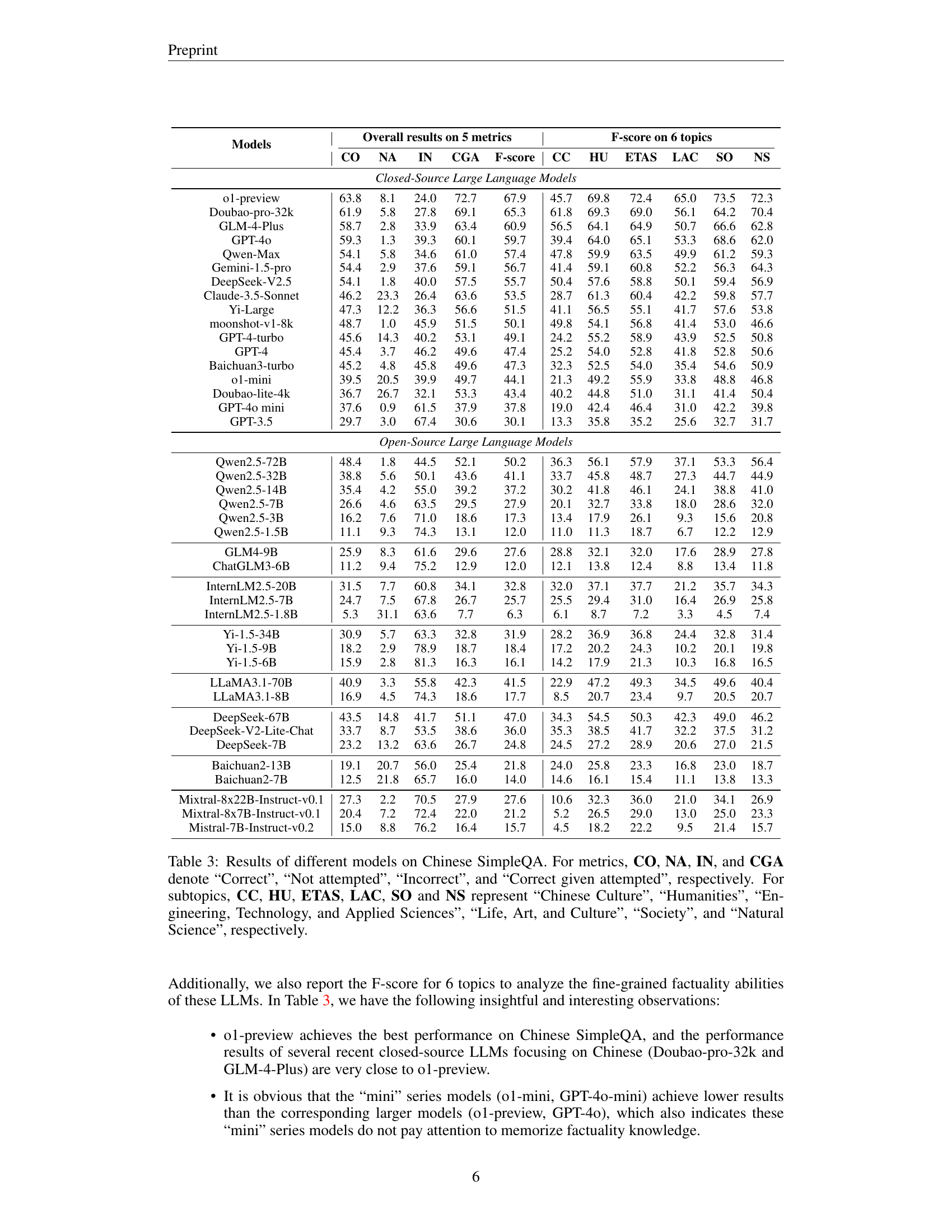

🔼 This table presents the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on the Chinese SimpleQA benchmark. The benchmark evaluates the models’ ability to answer short, factual questions in Chinese across six primary topic areas: Chinese Culture (CC), Humanities (HU), Engineering, Technology, and Applied Sciences (ETAS), Life, Art, and Culture (LAC), Society (SO), and Natural Science (NS). The results are presented using five metrics: Correct (CO), Not Attempted (NA), Incorrect (IN), Correct Given Attempted (CGA), and F-score. Each metric assesses a different aspect of the model’s factuality performance. The table allows for a detailed comparison of LLMs, revealing their strengths and weaknesses within each topic and overall.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of different models on Chinese SimpleQA. For metrics, CO, NA, IN, and CGA denote “Correct”, “Not attempted”, “Incorrect”, and “Correct given attempted”, respectively. For subtopics, CC, HU, ETAS, LAC, SO and NS represent “Chinese Culture”, “Humanities”, “Engineering, Technology, and Applied Sciences”, “Life, Art, and Culture”, “Society”, and “Natural Science”, respectively.

Full paper#