↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are powerful but struggle with long-context reasoning, especially tasks requiring complex multi-step reasoning. Existing solutions often rely on human annotations or advanced models for data synthesis, limiting scalability and progress. This is a significant bottleneck in advancing LLM capabilities.

This research introduces SEALONG, a self-improvement method that addresses these limitations. SEALONG samples multiple model outputs for each question, scores them using Minimum Bayes Risk (prioritizing consistent outputs), and then applies supervised fine-tuning or preference optimization. Experiments show SEALONG significantly boosts performance across several leading LLMs on various long-context reasoning benchmarks, exceeding the performance of prior methods that rely on expert-generated data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces SEALONG, a novel self-improvement method for LLMs in long-context reasoning. This addresses a significant limitation of current LLMs and opens new avenues for research in self-improving AI, potentially leading to more capable and robust large language models. The findings are particularly relevant given the increasing demand for LLMs capable of handling complex reasoning tasks across extended contexts.

Visual Insights#

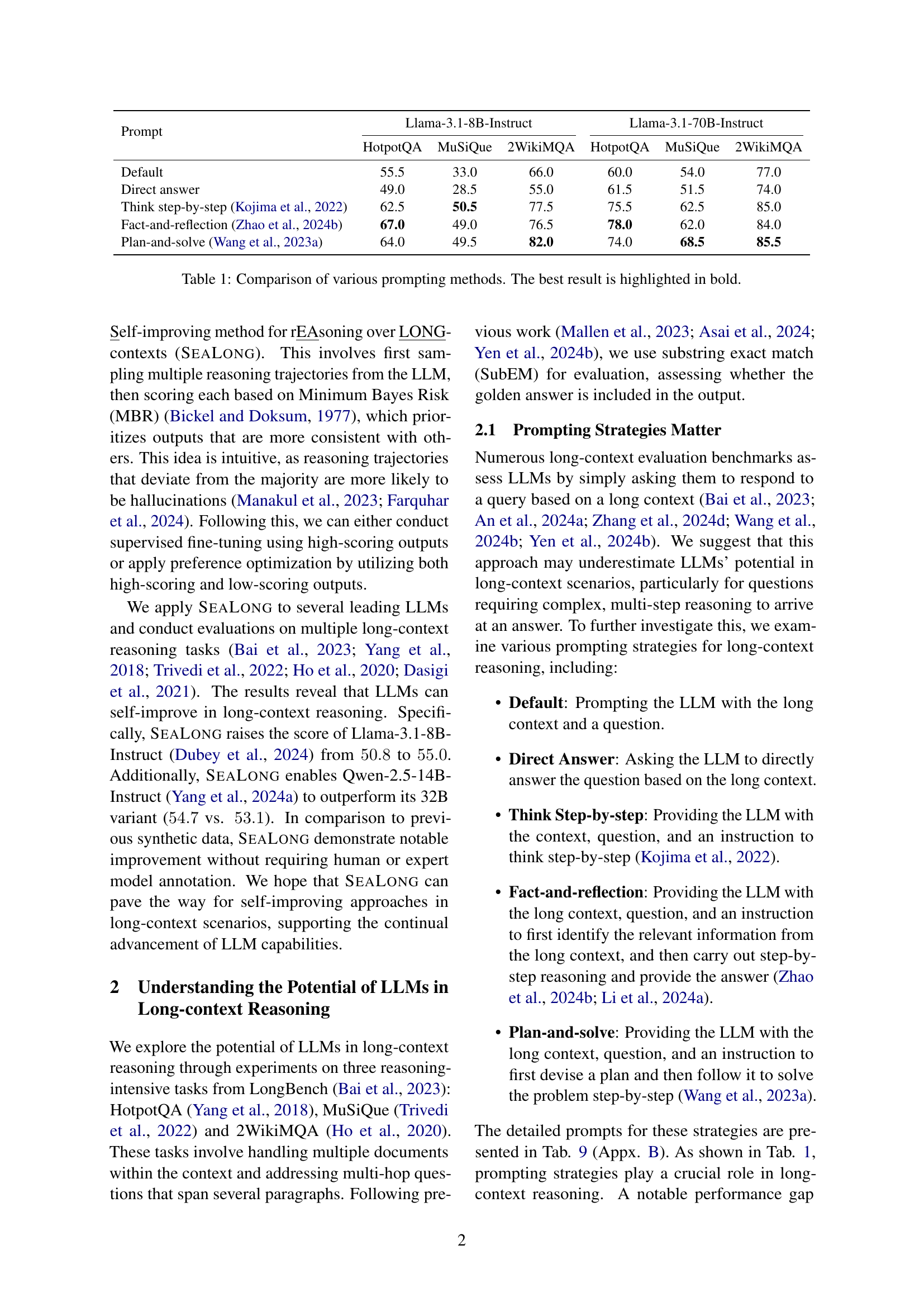

🔼 This figure shows how increasing the number of sampled model outputs affects the accuracy of both an oracle (the best possible output) and the MBR decoding method. The x-axis represents the number of samples, and the y-axis shows the accuracy (SubEM score) on three different long-context reasoning tasks: HotpotQA, MuSiQue, and 2WikiMQA. The results demonstrate that as the number of samples increases, the accuracy of both the oracle and MBR decoding improve significantly. This improvement suggests that selecting the best model response from a set of candidates is more effective than relying on a single prediction. The model used for this experiment is Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct.

read the caption

Figure 1: Scaling up the number of sampled outputs improves the performance of both the oracle sample and MBR decoding (§3.1). The results are based on Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct.

| Prompt | Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HotpotQA | MuSiQue | 2WikiMQA | HotpotQA | MuSiQue | 2WikiMQA | |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Default | 55.5 | 33.0 | 66.0 | 60.0 | 54.0 | 77.0 |

| Direct answer | 49.0 | 28.5 | 55.0 | 61.5 | 51.5 | 74.0 |

| Think step-by-step [Kojima et al., 2022] | 62.5 | 50.5 | 77.5 | 75.5 | 62.5 | 85.0 |

| Fact-and-reflection [Zhao et al., 2024b] | 67.0 | 49.0 | 76.5 | 78.0 | 62.0 | 84.0 |

| Plan-and-solve [Wang et al., 2023a] | 64.0 | 49.5 | 82.0 | 74.0 | 68.5 | 85.5 |

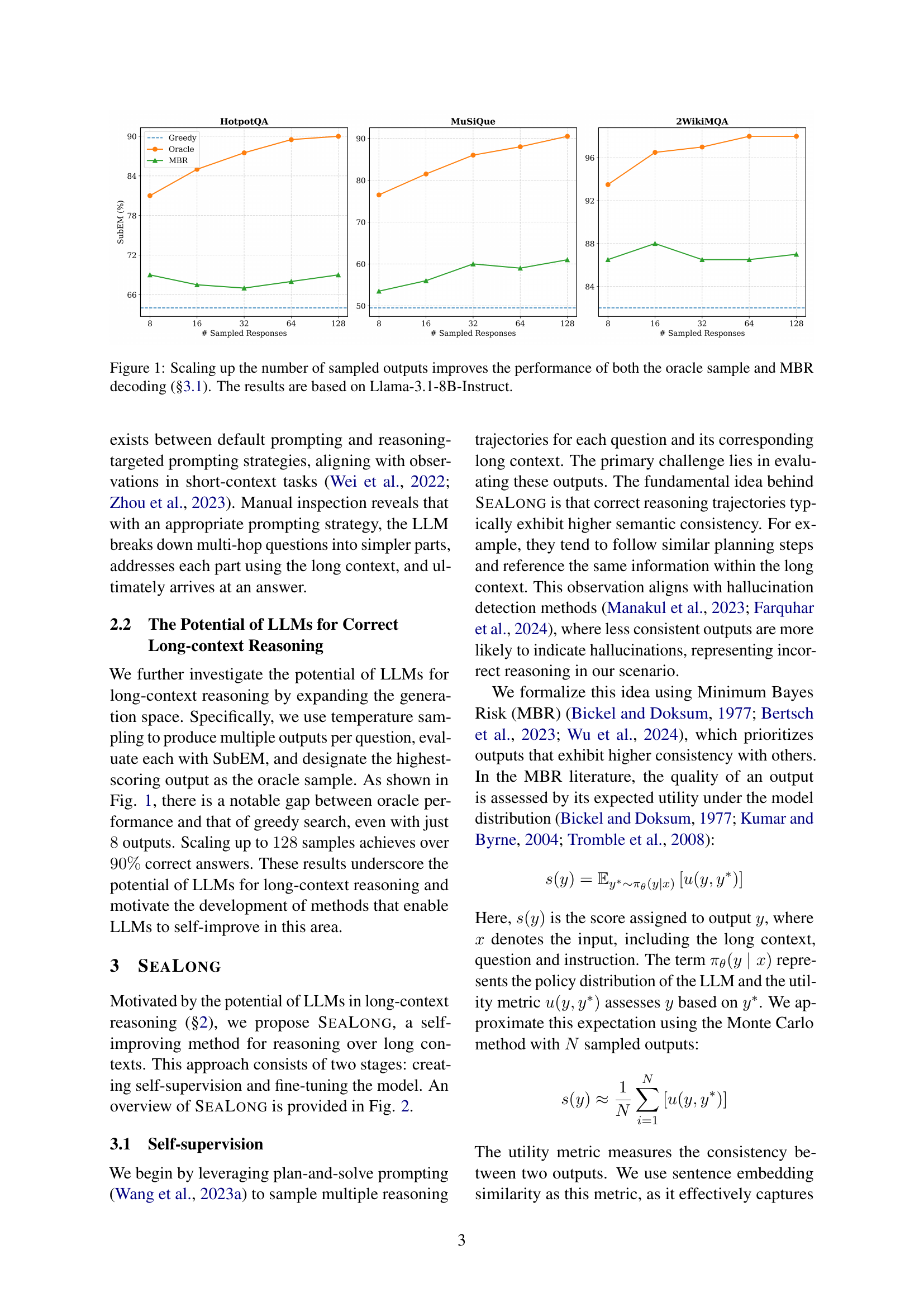

🔼 This table compares the performance of several prompting methods on two LLMs, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct, across three long-context reasoning tasks: HotpotQA, MuSiQue, and 2WikiMQA. The performance is measured using the substring exact match (SubEM) metric. The table helps illustrate how different prompting techniques can significantly impact the effectiveness of LLMs in long-context reasoning. The best performing prompting method for each task and LLM is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of various prompting methods. The best result is highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

LLM Self-Improvement#

The concept of “LLM Self-Improvement” is a significant advancement in the field of large language models. It explores the potential for LLMs to improve their capabilities without relying on external human annotation or advanced model assistance. This is crucial because the creation of high-quality training data is expensive and time-consuming. The core idea is to leverage LLMs’ inherent strengths in reasoning and retrieval to generate self-training data. By sampling multiple outputs, scoring them using metrics like Minimum Bayes Risk, and fine-tuning the model based on these scores, LLMs can iteratively refine their performance. This self-supervised learning approach is especially promising for long-context reasoning tasks, where LLMs currently struggle. While the method shows potential, challenges remain, including finding optimal scoring methods and the reliance on specific datasets for initial training. Future research should focus on improving the self-evaluation mechanisms and creating more comprehensive benchmark datasets to fully unlock the potential of LLM self-improvement.

SEALONG Framework#

The SEALONG framework, as described in the research paper, is a novel self-improvement method designed to enhance the long-context reasoning capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs). Its core innovation lies in leveraging the LLM’s inherent ability for self-evaluation and self-correction. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on human annotations or advanced models for training data, SEALONG uses a straight-forward process: multiple LLM outputs are generated for each query, then scored using Minimum Bayes Risk (MBR), which emphasizes consistency among responses. High-scoring outputs are used for supervised fine-tuning, or high and low-scoring outputs are paired for preference optimization. This self-supervised learning mechanism allows the LLM to iteratively refine its reasoning abilities without external intervention. The results demonstrate a significant performance improvement on various long-context reasoning benchmarks, highlighting the potential of SEALONG as a robust and scalable self-improvement technique, particularly relevant in scenarios with limited human or expert resources. The framework’s data efficiency and generalizability to diverse LLMs represent a significant step towards building more adaptable and effective long-context reasoning AI systems.

Long-Context Reasoning#

Long-context reasoning, the ability of large language models (LLMs) to effectively process and reason over extensive textual information, is a significant area of research. Current LLMs often struggle with this task, demonstrating a performance drop compared to their abilities on shorter contexts. This is largely due to the challenges in data synthesis for training such models; existing methods rely on either expensive and time-consuming human annotation or the use of advanced LLMs like GPT-4, creating a bottleneck for further progress. The paper explores the potential for self-improvement techniques within LLMs, directly tackling the limitations of existing data generation methods. A key idea is leveraging the inherent reasoning capabilities of LLMs to generate and evaluate their own responses. This involves sampling multiple outputs, scoring them based on consistency and utilizing a supervised fine-tuning or preference optimization strategy. The approach is particularly intriguing given the demonstrated success of LLMs in other tasks involving long contexts. This self-supervised learning framework is crucial to the advancement of LLMs, allowing them to improve reasoning abilities within longer contexts without reliance on human expertise or powerful, pre-existing models.

MBR Decoding#

Minimum Bayes Risk (MBR) decoding is a crucial component of the SEALONG approach for self-improving LLMs in long-context reasoning. MBR prioritizes outputs that demonstrate higher consistency with other generated outputs, thus reducing the likelihood of selecting outputs exhibiting hallucinations or incorrect reasoning. This is based on the intuitive notion that correct reasoning trajectories will show more similarity and coherence than incorrect ones. The method leverages sentence embedding similarity to measure this consistency. While effective in improving performance over greedy search, MBR’s reliance on consistency as a measure of correctness has limitations, potentially overlooking other factors contributing to accurate reasoning. Future research could explore using more sophisticated evaluation methods, considering diverse aspects beyond semantic similarity to further refine the selection of high-quality outputs and enhance the LLM’s self-improvement capabilities. The choice of MBR highlights the importance of effective evaluation techniques in self-supervised learning for LLMs.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on self-improving LLMs for long-context reasoning could explore several key areas. Improving the scoring mechanism used for self-supervision is crucial; current methods, while showing promise, still have a notable gap in performance compared to an oracle. Investigating more sophisticated evaluation approaches such as LLMs as critics or enhanced semantic similarity measures could bridge this gap. Expanding the scope of synthetic data generation beyond the current reliance on a single dataset is needed to fully understand the generalizability of self-improvement methods across diverse reasoning tasks and question types. Research should also focus on handling even longer contexts, pushing beyond the current 32k token limit, and investigating the scaling properties of self-improvement techniques for extremely long sequences. Finally, investigating the impact of different prompting strategies on the effectiveness of self-improvement and exploring the integration of self-improvement techniques with other advanced LLM architectures and methods, like chain-of-thought prompting, warrants further investigation. Addressing these points will enhance our understanding of how to create robust and generalizable self-improving LLMs capable of exceeding current performance limitations in long-context reasoning tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

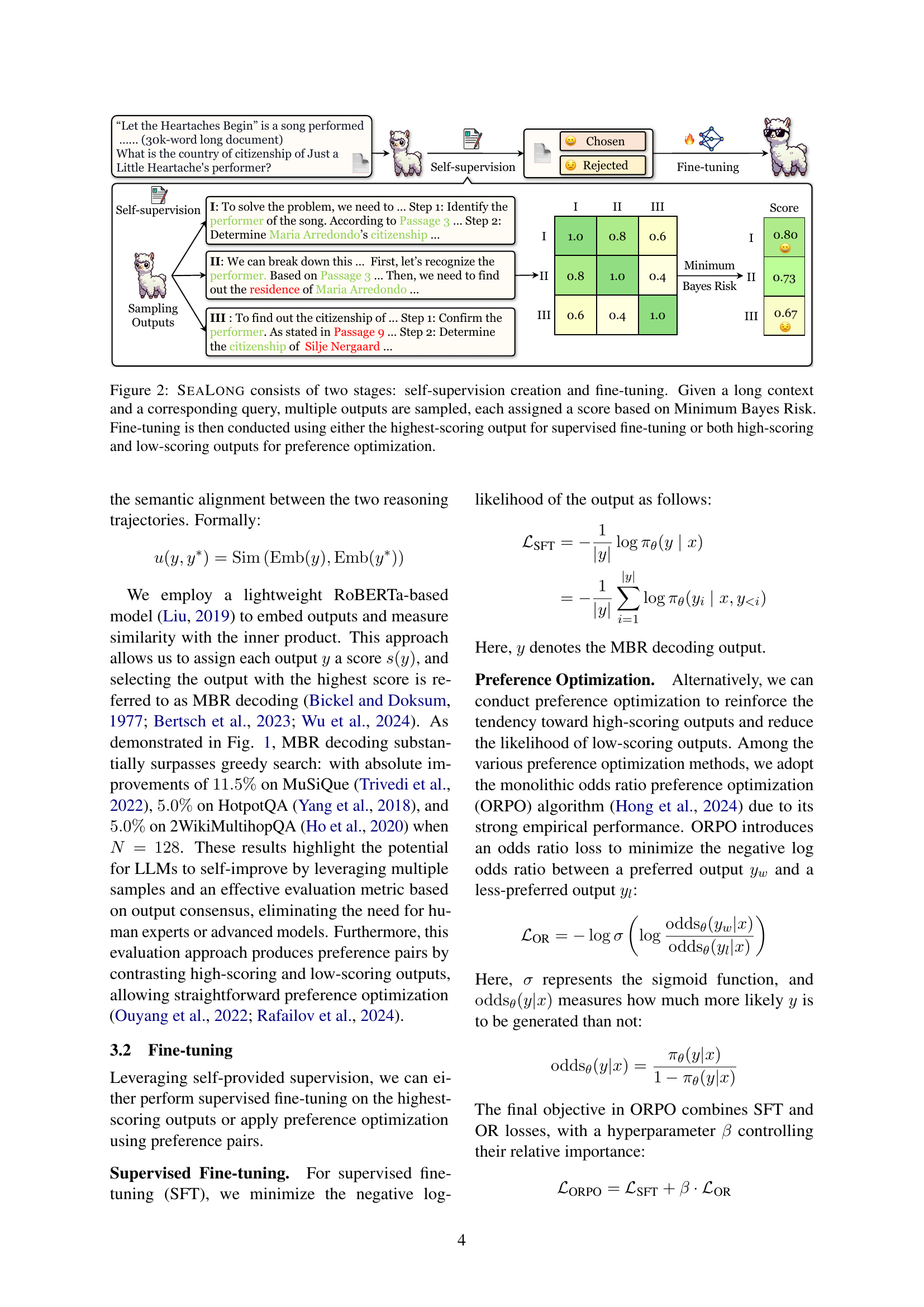

🔼 SEALONG is a two-stage process. First, it generates multiple responses to a given long context and question using a plan-and-solve prompting strategy. These responses are scored using Minimum Bayes Risk (MBR), which favors responses with higher consistency. Second, these scores inform the fine-tuning method. The highest-scoring response can be used for supervised fine-tuning, or high and low scoring responses can be used for preference optimization.

read the caption

Figure 2: SeaLong consists of two stages: self-supervision creation and fine-tuning. Given a long context and a corresponding query, multiple outputs are sampled, each assigned a score based on Minimum Bayes Risk. Fine-tuning is then conducted using either the highest-scoring output for supervised fine-tuning or both high-scoring and low-scoring outputs for preference optimization.

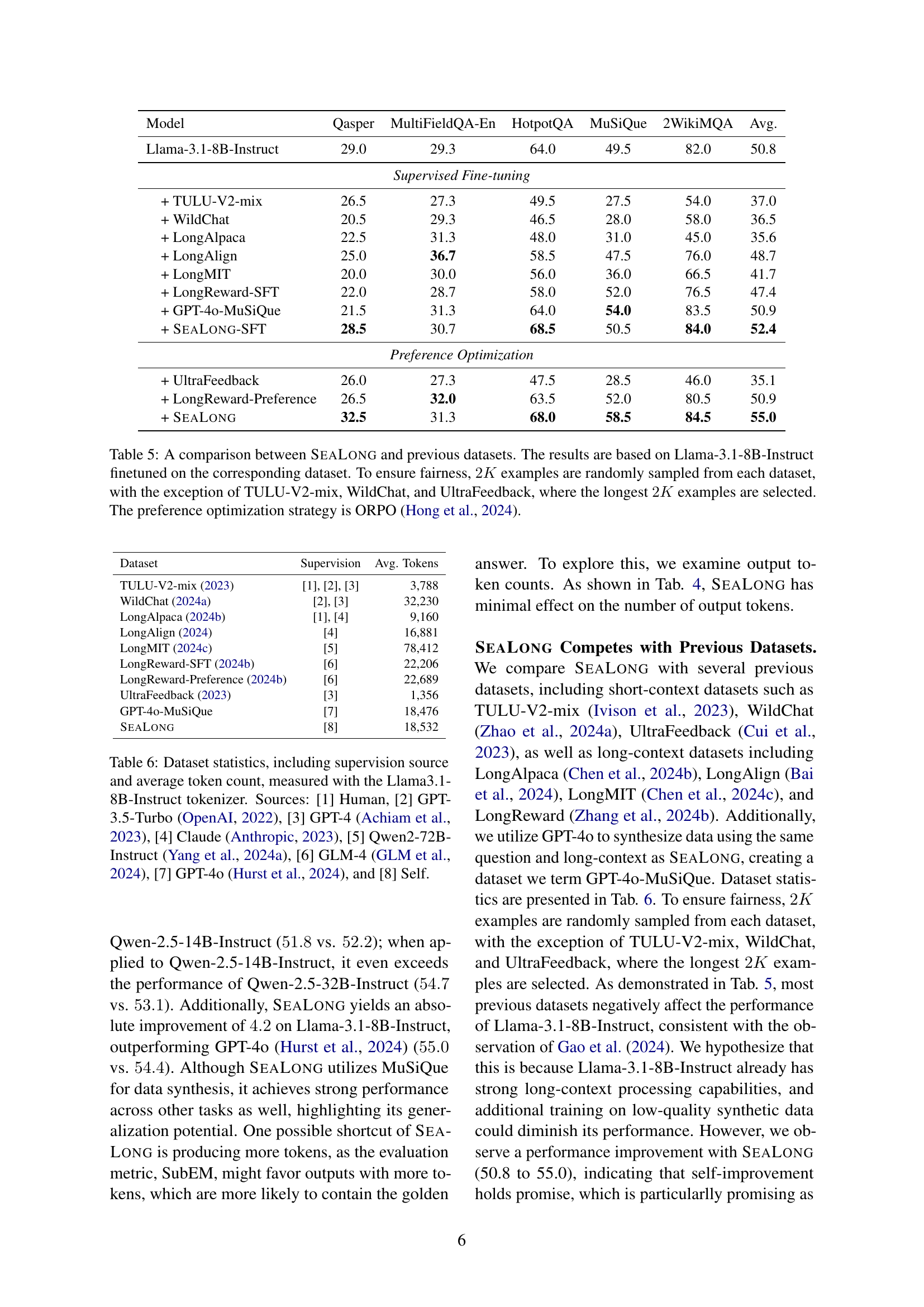

🔼 This figure displays the relationship between the number of synthetic training examples used in SeaLong and the resulting performance on long-context tasks. The performance is measured using Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, which was fine-tuned on datasets created with different numbers of synthetic examples. The graph shows that SeaLong’s performance improves with increasing numbers of synthetic training examples, but the improvement plateaus after a certain point, demonstrating the efficiency of the method.

read the caption

Figure 3: Long-context performance of SeaLong with varying numbers of synthetic training examples, evaluated based on Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct fine-tuned on the corresponding dataset.

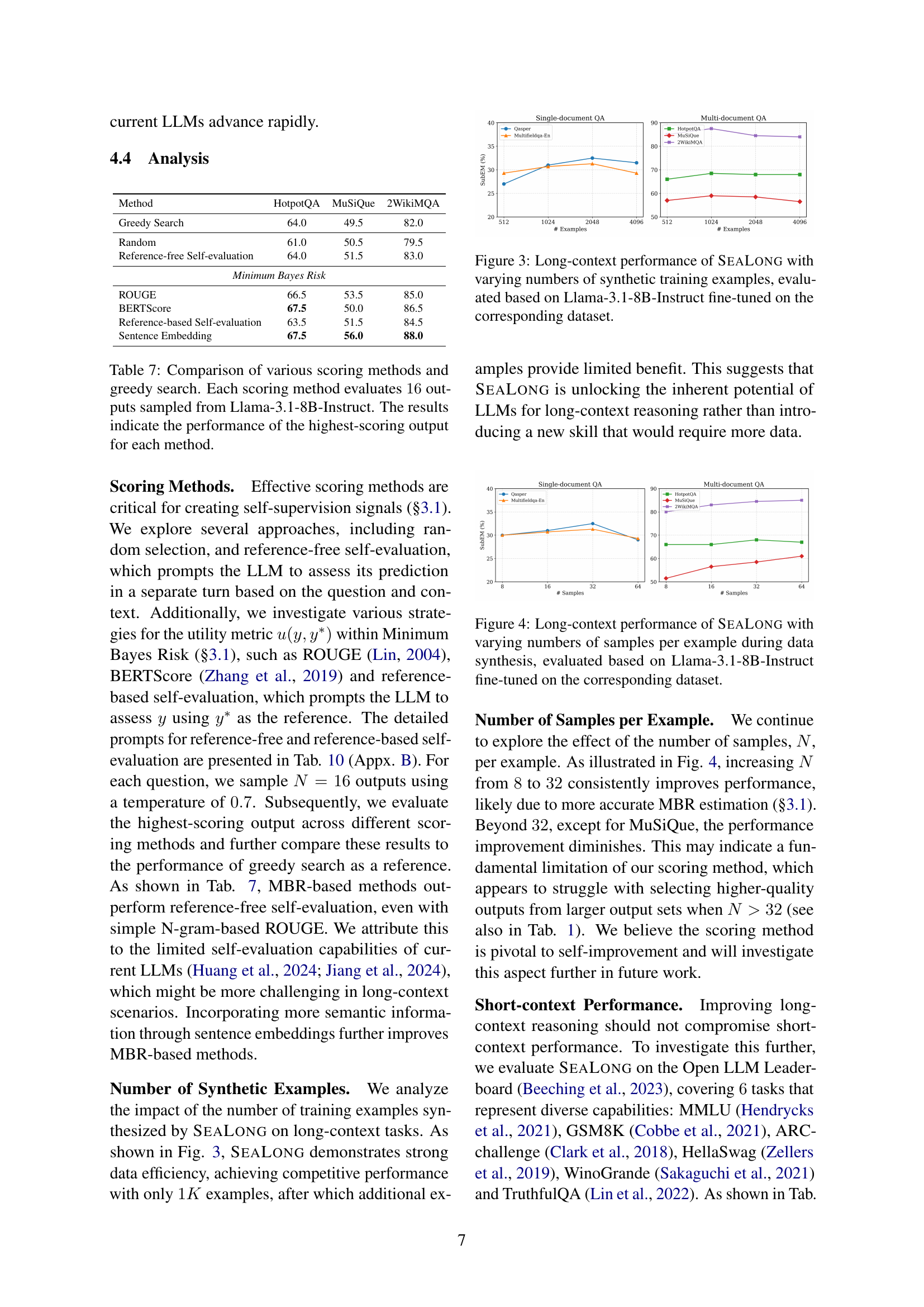

🔼 This figure shows how the performance of the SeaLong model changes depending on the number of samples used per example during the data synthesis phase. The evaluation was done using the Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct model, fine-tuned on the data created with varying numbers of samples. The performance is measured across several long-context reasoning tasks (as shown in the different colored lines), illustrating how increasing the number of samples improves performance up to a certain point, after which improvements become marginal. This demonstrates SeaLong’s efficiency and effectiveness in leveraging multiple LLM outputs for improved performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: Long-context performance of SeaLong with varying numbers of samples per example during data synthesis, evaluated based on Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct fine-tuned on the corresponding dataset.

More on tables

| Model | Qasper | MultiFieldQA-En | HotpotQA | MuSiQue | 2WikiMQA | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct (Yang et al., 2024a) | 21.0 | 28.0 | 70.5 | 48.0 | 77.5 | 49.0 |

| + SeaLong | 26.0 | 29.3 | 72.5 | 51.5 | 79.5 | 51.8 |

| Qwen-2.5-14B-Instruct (Yang et al., 2024a) | 21.0 | 32.0 | 73.0 | 52.0 | 83.0 | 52.2 |

| + SeaLong | 24.0 | 30.0 | 75.0 | 57.0 | 87.5 | 54.7 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (Dubey et al., 2024) | 29.0 | 29.3 | 64.0 | 49.5 | 82.0 | 50.8 |

| + SeaLong | 32.5 | 31.3 | 68.0 | 58.5 | 84.5 | 55.0 |

| Qwen-2.5-32B-Instruct (Yang et al., 2024a) | 24.5 | 26.0 | 72.0 | 55.0 | 88.0 | 53.1 |

| Qwen-2.5-72B-Instruct (Yang et al., 2024a) | 27.0 | 28.7 | 74.5 | 58.5 | 89.0 | 55.5 |

| Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct (Dubey et al., 2024) | 30.0 | 33.3 | 74.0 | 68.5 | 85.5 | 58.3 |

| GPT-4o (Hurst et al., 2024) | 21.5 | 28.0 | 74.5 | 64.0 | 84.0 | 54.4 |

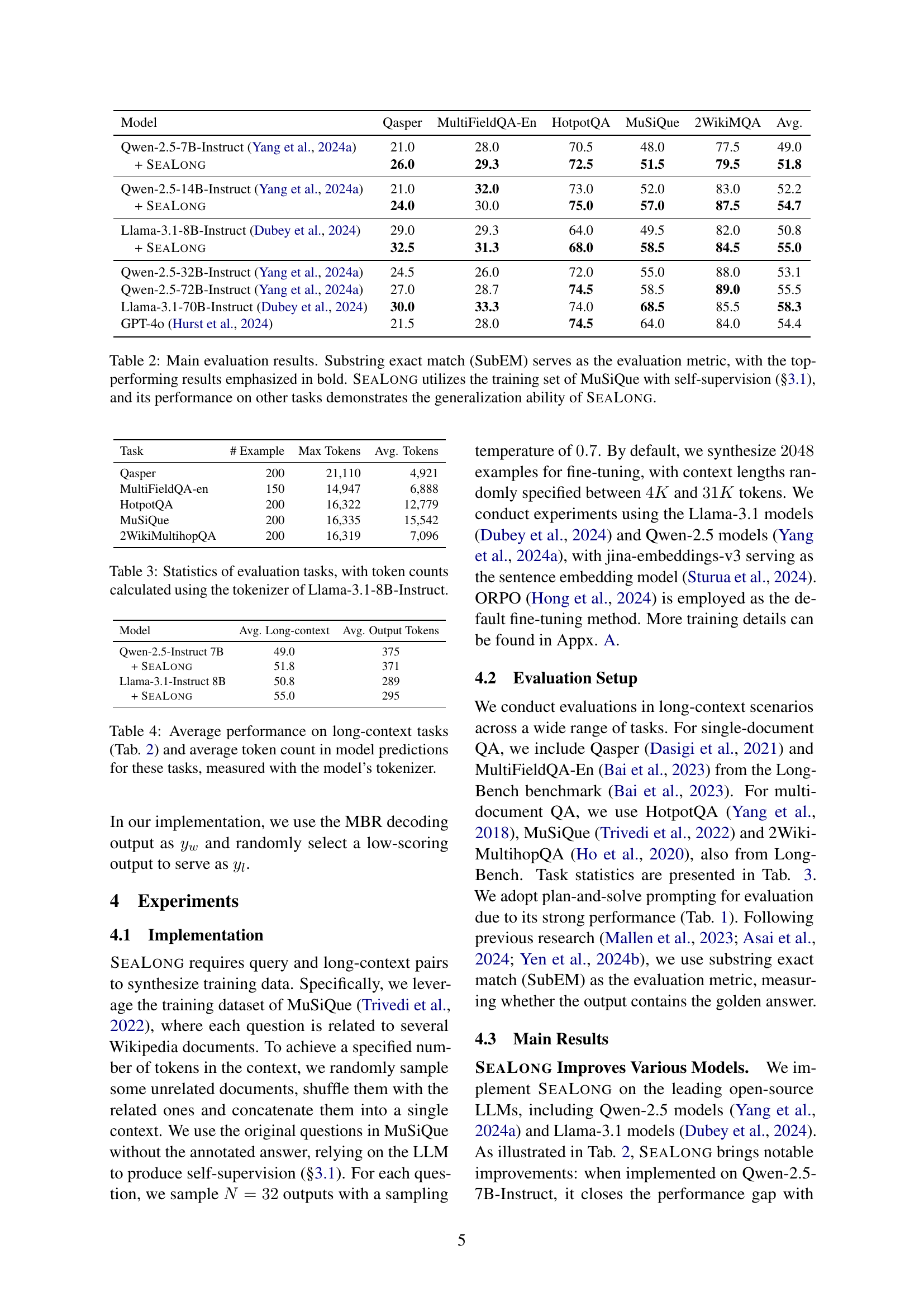

🔼 Table 2 presents the main experimental results of the SEALONG model, compared against various baselines. The evaluation metric used is Substring Exact Match (SubEM), which measures if the correct answer is a substring of the model’s output. The table highlights the best-performing model for each task in bold. Importantly, SEALONG only used the MuSiQue training set with a self-supervision approach for training, showcasing its ability to generalize well to other datasets.

read the caption

Table 2: Main evaluation results. Substring exact match (SubEM) serves as the evaluation metric, with the top-performing results emphasized in bold. SeaLong utilizes the training set of MuSiQue with self-supervision (§3.1), and its performance on other tasks demonstrates the generalization ability of SeaLong.

| Task | # Example | Max Tokens | Avg. Tokens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qasper | 200 | 21,110 | 4,921 |

| MultiFieldQA-en | 150 | 14,947 | 6,888 |

| HotpotQA | 200 | 16,322 | 12,779 |

| MuSiQue | 200 | 16,335 | 15,542 |

| 2WikiMultihopQA | 200 | 16,319 | 7,096 |

🔼 This table presents a statistical overview of the datasets used for evaluating long-context reasoning models. It shows the number of examples, the maximum number of tokens, and the average number of tokens per example for five different tasks: Qasper, MultiFieldQA-en, HotpotQA, MuSiQue, and 2WikiMultihopQA. Token counts are calculated using the Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct tokenizer, ensuring consistency in the tokenization process across different datasets.

read the caption

Table 3: Statistics of evaluation tasks, with token counts calculated using the tokenizer of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct.

| Model | Avg. Long-context | Avg. Output Tokens |

|---|---|---|

| Qwen-2.5-Instruct 7B | 49.0 | 375 |

| Qwen-2.5-Instruct 7B + SeaLong | 51.8 | 371 |

| Llama-3.1-Instruct 8B | 50.8 | 289 |

| Llama-3.1-Instruct 8B + SeaLong | 55.0 | 295 |

🔼 This table presents the average performance of different large language models (LLMs) on various long-context reasoning tasks, as reported in Table 2 of the paper. It also shows the average number of tokens generated by each model in its responses. The token count is a measure of the length of the model’s answer and is calculated using the model’s internal tokenizer.

read the caption

Table 4: Average performance on long-context tasks (Tab. 2) and average token count in model predictions for these tasks, measured with the model’s tokenizer.

| Model | Qasper | MultiFieldQA-En | HotpotQA | MuSiQue | 2WikiMQA | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | 29.0 | 29.3 | 64.0 | 49.5 | 82.0 | 50.8 |

| Supervised Fine-tuning | ||||||

| + TULU-V2-mix | 26.5 | 27.3 | 49.5 | 27.5 | 54.0 | 37.0 |

| + WildChat | 20.5 | 29.3 | 46.5 | 28.0 | 58.0 | 36.5 |

| + LongAlpaca | 22.5 | 31.3 | 48.0 | 31.0 | 45.0 | 35.6 |

| + LongAlign | 25.0 | 36.7 | 58.5 | 47.5 | 76.0 | 48.7 |

| + LongMIT | 20.0 | 30.0 | 56.0 | 36.0 | 66.5 | 41.7 |

| + LongReward-SFT | 22.0 | 28.7 | 58.0 | 52.0 | 76.5 | 47.4 |

| + GPT-4o-MuSiQue | 21.5 | 31.3 | 64.0 | 54.0 | 83.5 | 50.9 |

| + SEAlong-SFT | 28.5 | 30.7 | 68.5 | 50.5 | 84.0 | 52.4 |

| Preference Optimization | ||||||

| + UltraFeedback | 26.0 | 27.3 | 47.5 | 28.5 | 46.0 | 35.1 |

| + LongReward-Preference | 26.5 | 32.0 | 63.5 | 52.0 | 80.5 | 50.9 |

| + SEAlong | 32.5 | 31.3 | 68.0 | 58.5 | 84.5 | 55.0 |

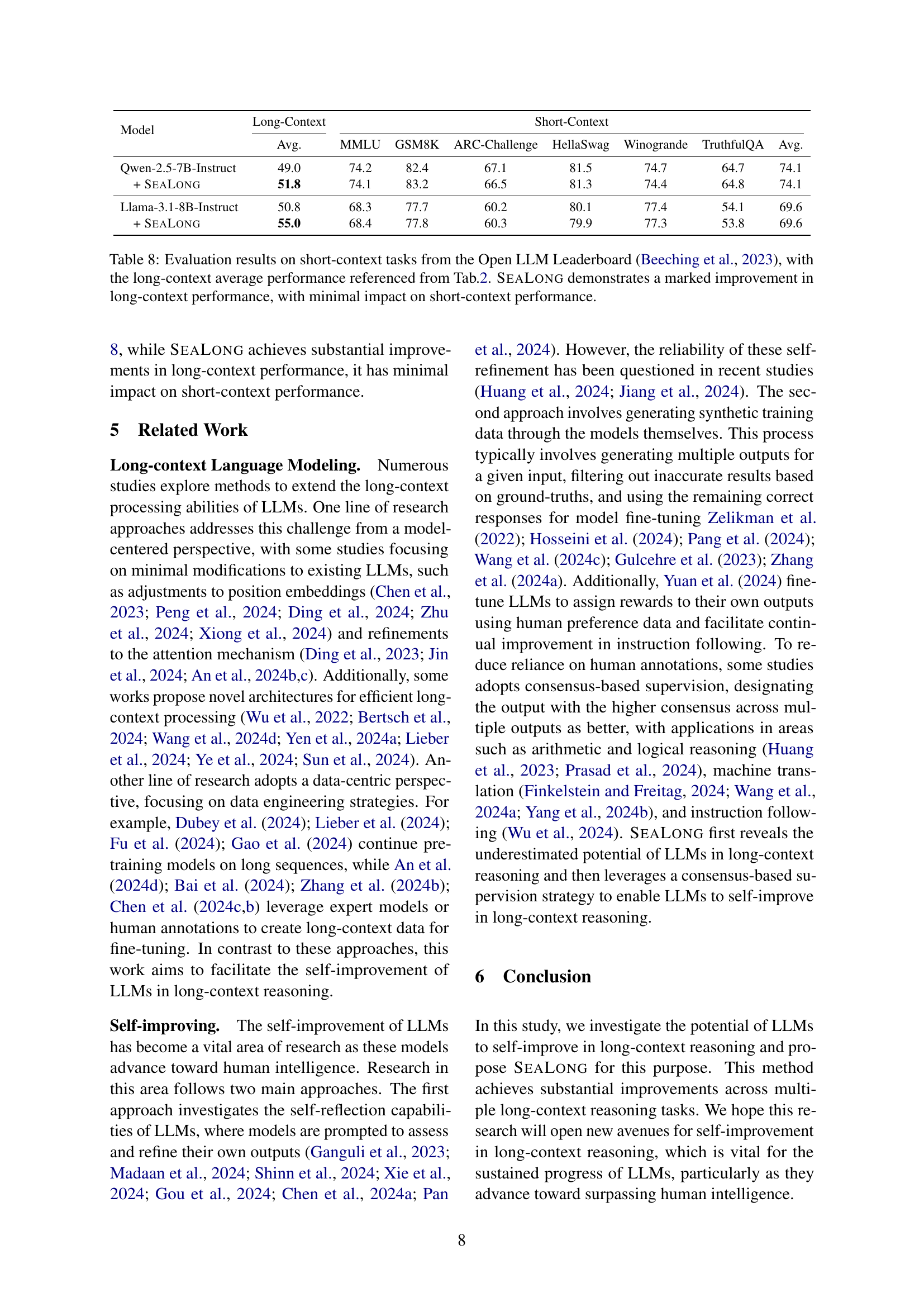

🔼 This table compares the performance of the SEALONG method with several other methods for long-context reasoning, all fine-tuned on Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. The results for each method are presented as average SubEM scores across five different long-context reasoning tasks. To ensure a fair comparison, 2000 examples were sampled from each dataset (except for three datasets where the longest 2000 were used). The comparison highlights SEALONG’s effectiveness relative to other approaches that utilize different training data sources. ORPO (a preference optimization strategy) was used for all preference optimization methods.

read the caption

Table 5: A comparison between SeaLong and previous datasets. The results are based on Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct finetuned on the corresponding dataset. To ensure fairness, 2K2𝐾2K2 italic_K examples are randomly sampled from each dataset, with the exception of TULU-V2-mix, WildChat, and UltraFeedback, where the longest 2K2𝐾2K2 italic_K examples are selected. The preference optimization strategy is ORPO (Hong et al., 2024).

| Dataset | Supervision | Avg. Tokens |

|---|---|---|

| TULU-V2-mix (2023) | [1], [2], [3] | 3,788 |

| WildChat (2024a) | [2], [3] | 32,230 |

| LongAlpaca (2024b) | [1], [4] | 9,160 |

| LongAlign (2024) | [4] | 16,881 |

| LongMIT (2024c) | [5] | 78,412 |

| LongReward-SFT (2024b) | [6] | 22,206 |

| LongReward-Preference (2024b) | [6] | 22,689 |

| UltraFeedback (2023) | [3] | 1,356 |

| GPT-4o-MuSiQue | [7] | 18,476 |

| SeaLong | [8] | 18,532 |

🔼 Table 6 presents a detailed breakdown of various datasets used in the paper’s experiments, focusing on their characteristics relevant to long-context reasoning. It lists each dataset’s name, the type of supervision used to create it (e.g., human annotation, GPT-3.5-Turbo, GPT-4, etc.), and the average number of tokens per data point, all calculated using Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct tokenizer. This information is crucial for understanding the different resources and data characteristics that the models were trained on and how this might have impacted the results.

read the caption

Table 6: Dataset statistics, including supervision source and average token count, measured with the Llama3.1-8B-Instruct tokenizer. Sources: [1] Human, [2] GPT-3.5-Turbo (OpenAI, 2022), [3] GPT-4 (Achiam et al., 2023), [4] Claude (Anthropic, 2023), [5] Qwen2-72B-Instruct (Yang et al., 2024a), [6] GLM-4 (GLM et al., 2024), [7] GPT-4o (Hurst et al., 2024), and [8] Self.

| Method | HotpotQA | MuSiQue | 2WikiMQA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greedy Search | 64.0 | 49.5 | 82.0 |

| Random | 61.0 | 50.5 | 79.5 |

| Reference-free Self-evaluation | 64.0 | 51.5 | 83.0 |

| Minimum Bayes Risk | |||

| ROUGE | 66.5 | 53.5 | 85.0 |

| BERTScore | 67.5 | 50.0 | 86.5 |

| Reference-based Self-evaluation | 63.5 | 51.5 | 84.5 |

| Sentence Embedding | 67.5 | 56.0 | 88.0 |

🔼 This table compares different methods for scoring multiple outputs generated by Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, a large language model. The goal is to determine which scoring approach best identifies the highest-quality output among multiple options. Each scoring method is applied to 16 different outputs, and the table reports the performance of only the highest-scoring output from each method. The performance is presumably measured on a downstream task, and comparing performance across various methods helps determine the best strategy for selecting high-quality responses from an LLM.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison of various scoring methods and greedy search. Each scoring method evaluates 16161616 outputs sampled from Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. The results indicate the performance of the highest-scoring output for each method.

| Model | Long-Context | MMLU | GSM8K | ARC-Challenge | HellaSwag | Winogrande | TruthfulQA | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct | 49.0 | 74.2 | 82.4 | 67.1 | 81.5 | 74.7 | 64.7 | 74.1 |

| Qwen-2.5-7B-Instruct + SeaLong | 51.8 | 74.1 | 83.2 | 66.5 | 81.3 | 74.4 | 64.8 | 74.1 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct | 50.8 | 68.3 | 77.7 | 60.2 | 80.1 | 77.4 | 54.1 | 69.6 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct + SeaLong | 55.0 | 68.4 | 77.8 | 60.3 | 79.9 | 77.3 | 53.8 | 69.6 |

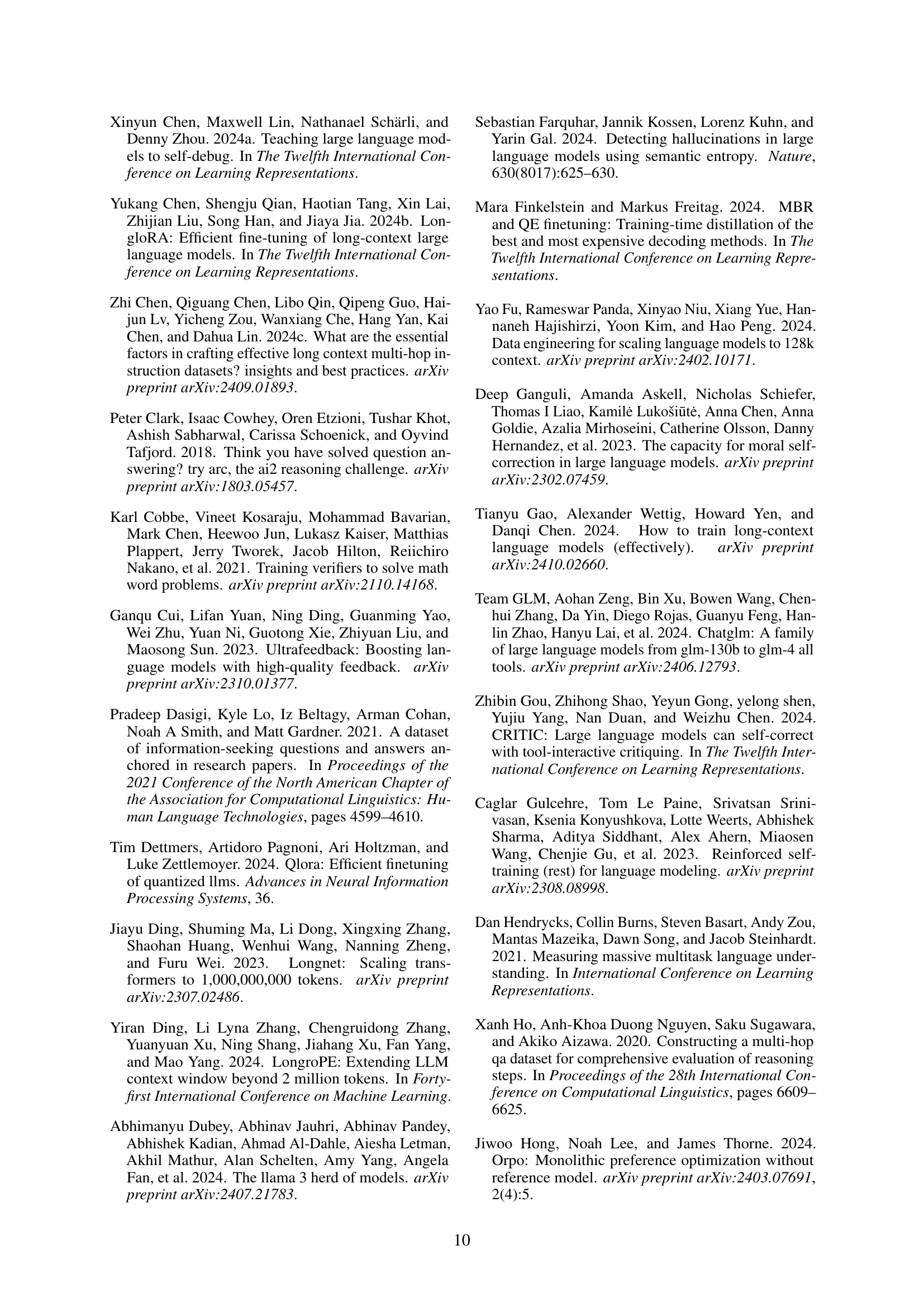

🔼 Table 8 presents the evaluation results of SeaLong and baseline models on several short-context tasks from the Open LLM Leaderboard. It compares the average performance on these short-context tasks with the average performance on long-context tasks (reported in Table 2). This comparison demonstrates SeaLong’s significant improvement in long-context reasoning abilities while maintaining comparable performance on short-context tasks.

read the caption

Table 8: Evaluation results on short-context tasks from the Open LLM Leaderboard (Beeching et al., 2023), with the long-context average performance referenced from Tab.2. SeaLong demonstrates a marked improvement in long-context performance, with minimal impact on short-context performance.

| Strategy | Prompt |

|---|---|

| Default | {context} {input} |

| Direct Answer | {context} {input} Let’s answer the question directly. |

| Think step-by-step (Kojima et al., 2022) | {context} {input} Let’s think step by step. |

| Fact-and-reflection (Zhao et al., 2024b) | {context} {input} Let’s first identify the relevant information from the long context and list it. Then, carry out step-by-step reasoning based on that information, and finally, provide the answer. |

| Plan-and-solve (Wang et al., 2023a) | {context} {input} Let’s first understand the problem and devise a plan to solve it. Then, let’s carry out the plan and solve the problem step-by-step. |

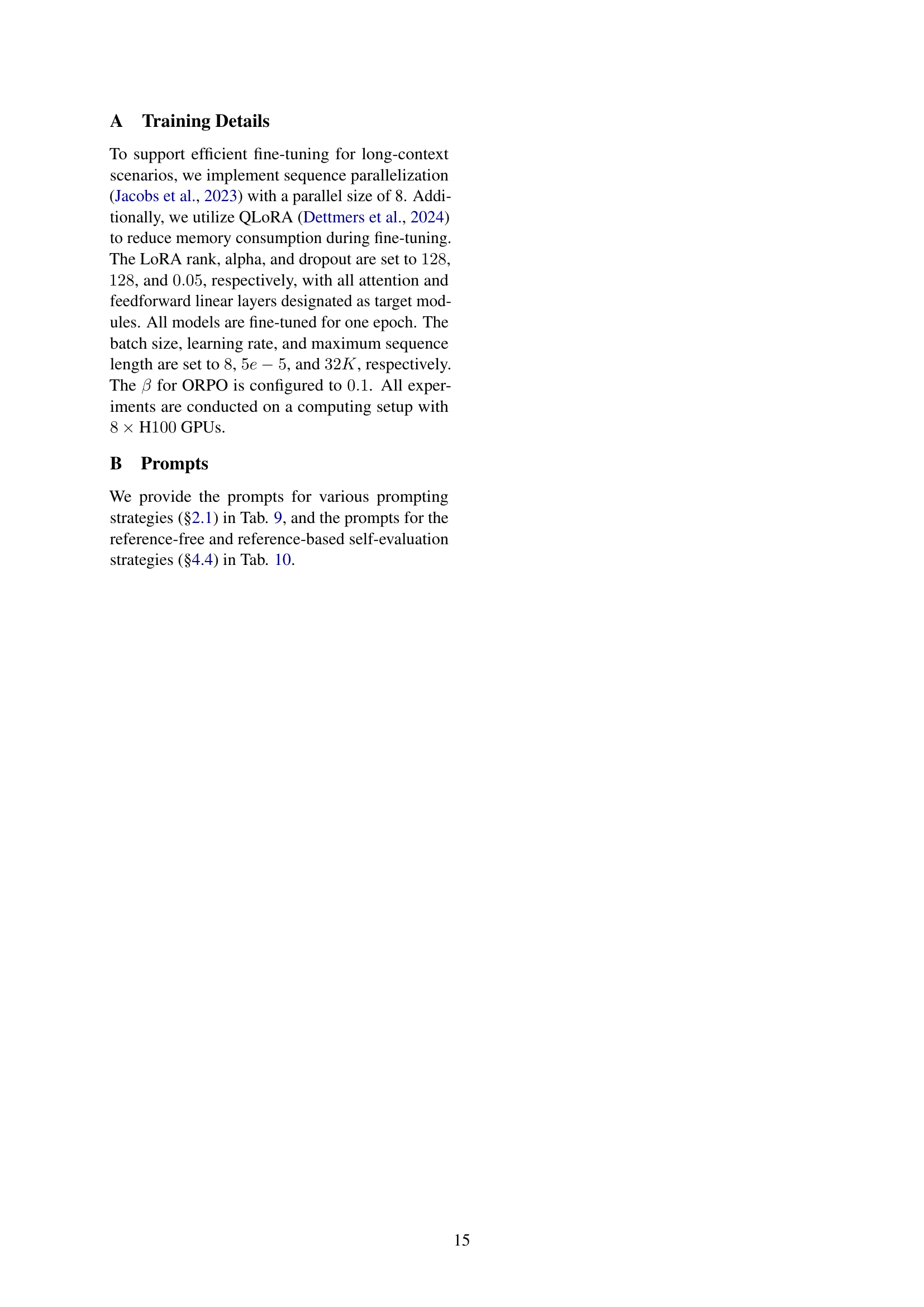

🔼 This table lists various prompting strategies used in the paper’s experiments and shows the prompts used for each strategy. The prompts are templates; ‘{context}’ is replaced with the actual long text provided to the LLM, and ‘{input}’ is replaced with the question. Different strategies include a simple default prompt, a direct answer prompt, step-by-step reasoning, fact-and-reflection prompting, and plan-and-solve prompting. Each prompt is designed to elicit different reasoning behaviors from the language model.

read the caption

Table 9: The prompts for various prompting strategies (§2.1), where {context} and {input} serve as placeholders for the long context and input query, respectively.

| Strategy | Prompt |

|---|---|

| Reference-free Self-Evaluation | [Context] {context} [Question] {question} [Predicted Response] {prediction} Please evaluate the correctness of the predicted response based on the context and the question. Begin your evaluation by providing a brief explanation. Be as objective as possible. After giving your explanation, you must rate the response on a scale from 1 to 5, following this format exactly: “[[rating]]”. For example, “Rating: [[3]]”. |

| Reference-based Self-Evaluation | Here is a question along with two responses: one is the reference response, and the other is the predicted response. Please determine whether the two responses provide the same answer to the question. Respond with “True” or “False” directly. [Question] {question} [Reference Response] {reference} [Predicted Response] {prediction} |

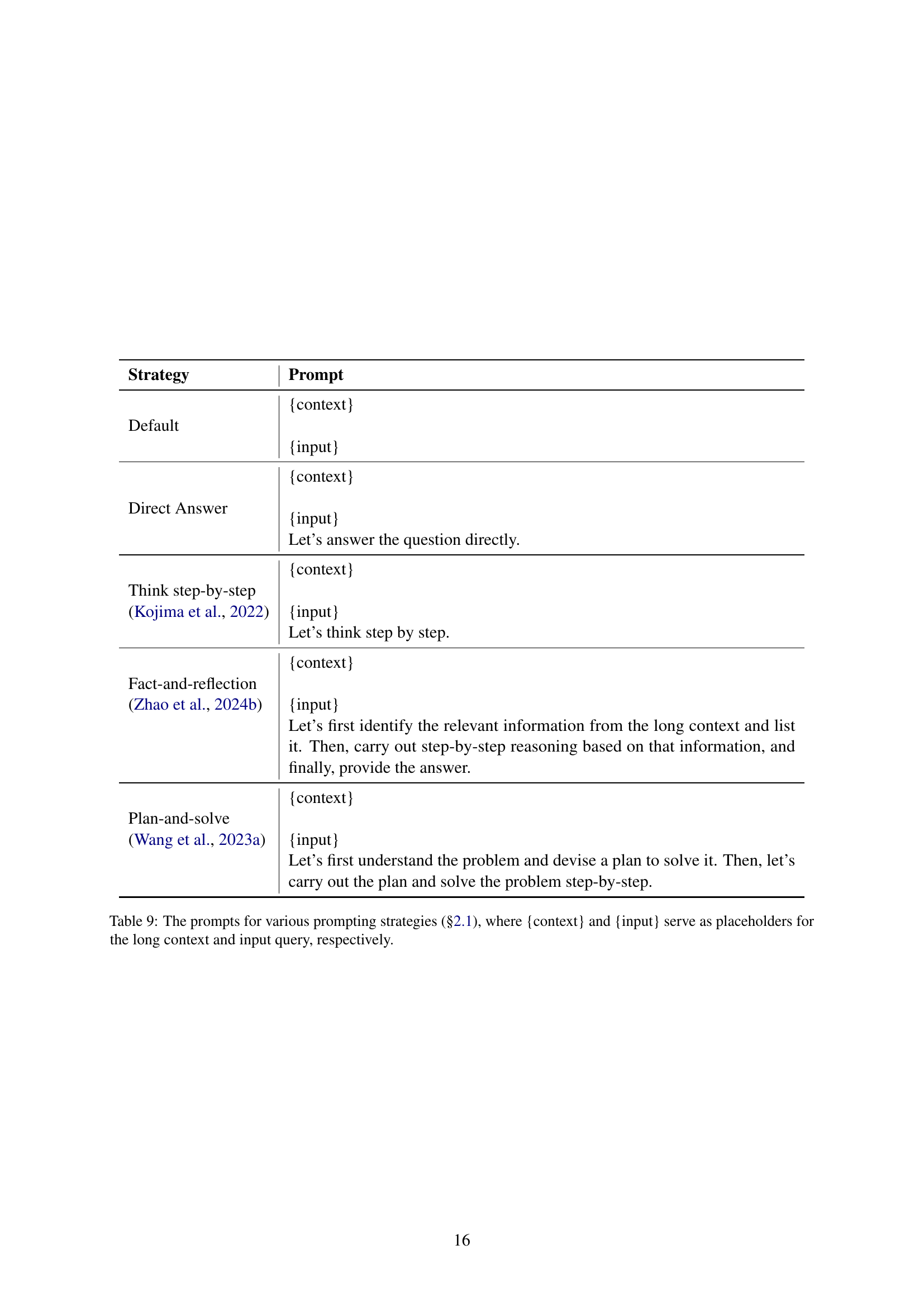

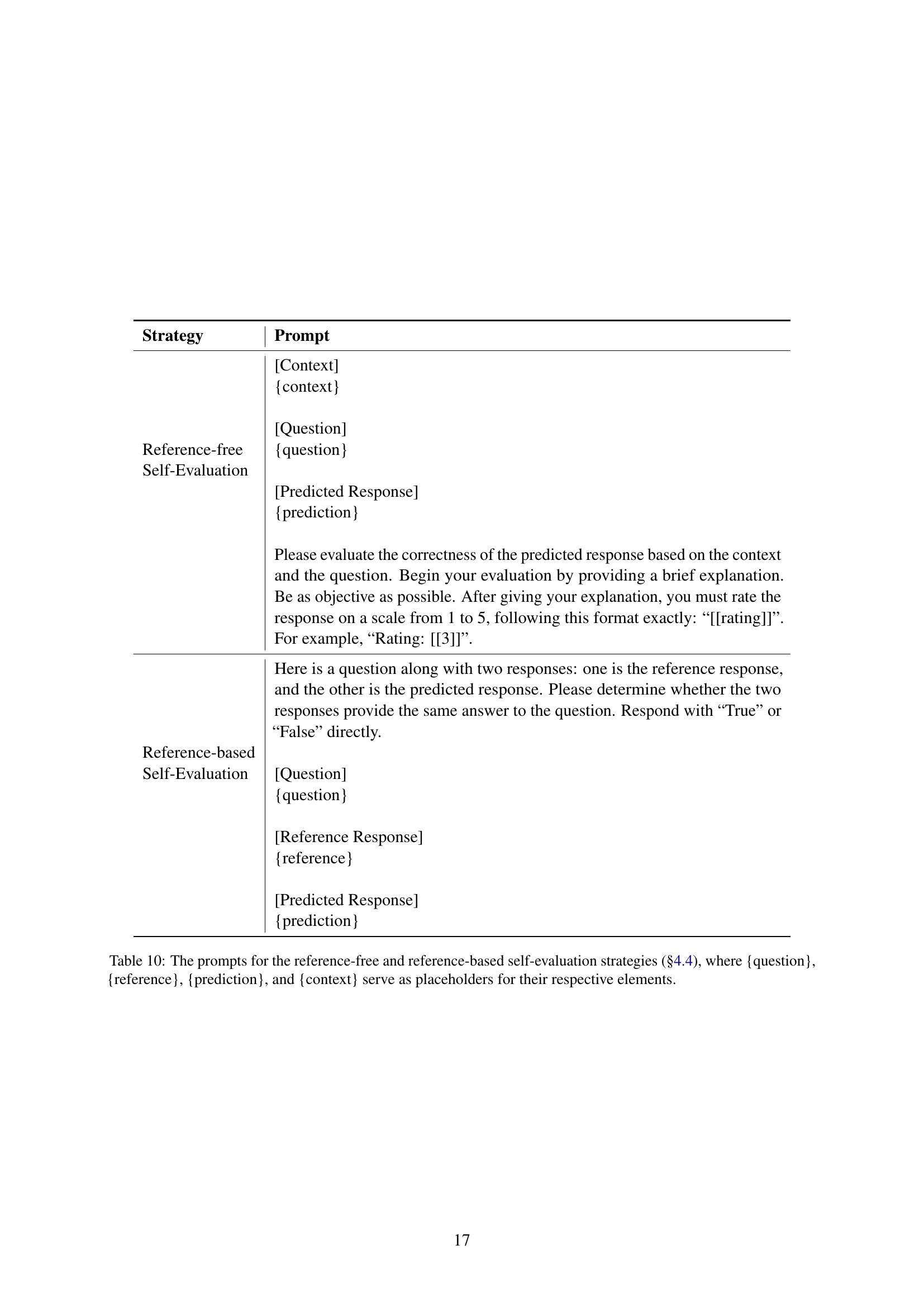

🔼 Table 10 shows the different prompts used in the reference-free and reference-based self-evaluation strategies. The reference-free strategy asks the LLM to evaluate the correctness of a given response based on the context and question, providing a rating from 1-5. The reference-based strategy presents the LLM with a question, a reference response and a predicted response, asking it to determine if both responses provide the same answer. The table uses placeholders {context}, {question}, {reference}, and {prediction} to indicate where the actual context, question, reference response, and prediction would be inserted.

read the caption

Table 10: The prompts for the reference-free and reference-based self-evaluation strategies (§4.4), where {question}, {reference}, {prediction}, and {context} serve as placeholders for their respective elements.

Full paper#