↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current open-source multimodal large language models (MLLMs) struggle with complex reasoning tasks, especially when using the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting method. This is primarily due to distribution shifts between training and inference, leading to decreased performance in generating detailed reasoning steps. Many existing multimodal preference datasets focus on addressing hallucination rather than improving reasoning abilities, and lack data representative of scientific images and reasoning tasks. These limitations hinder the development of more capable MLLMs.

To address these issues, the researchers introduced Mixed Preference Optimization (MPO), a novel method that combines supervised fine-tuning with preference optimization losses. MPO effectively enhances the model’s ability to generate high-quality reasoning steps. They also created a large-scale, high-quality multimodal reasoning preference dataset called MMPR, using an automated pipeline to efficiently generate preference pairs. The resulting InternVL2-8B-MPO model significantly outperforms previous open-source models on various multimodal reasoning benchmarks, achieving performance comparable to much larger models. This work demonstrates the effectiveness of preference optimization in improving MLLM reasoning abilities, providing valuable resources for future research in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multimodal large language models (MLLMs) because it directly addresses the limitations of current models in multimodal reasoning, particularly within the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) paradigm. The introduction of Mixed Preference Optimization (MPO) and the MMPR dataset offers significant advancements. MPO provides a novel approach to enhance reasoning capabilities, while the MMPR dataset offers valuable, high-quality data for training and benchmarking. This work opens new avenues for enhancing MLLM reasoning abilities and improving their performance on complex reasoning tasks.

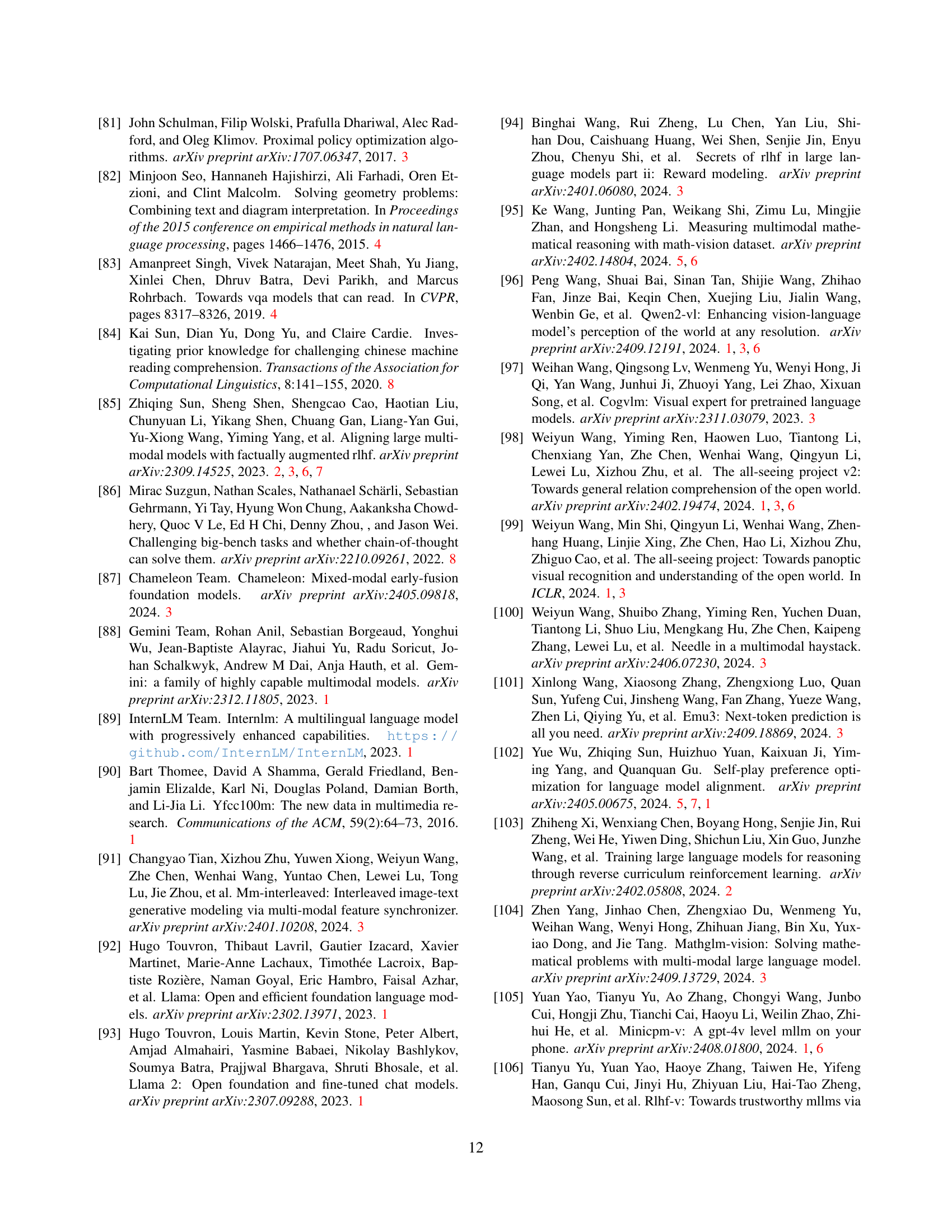

Visual Insights#

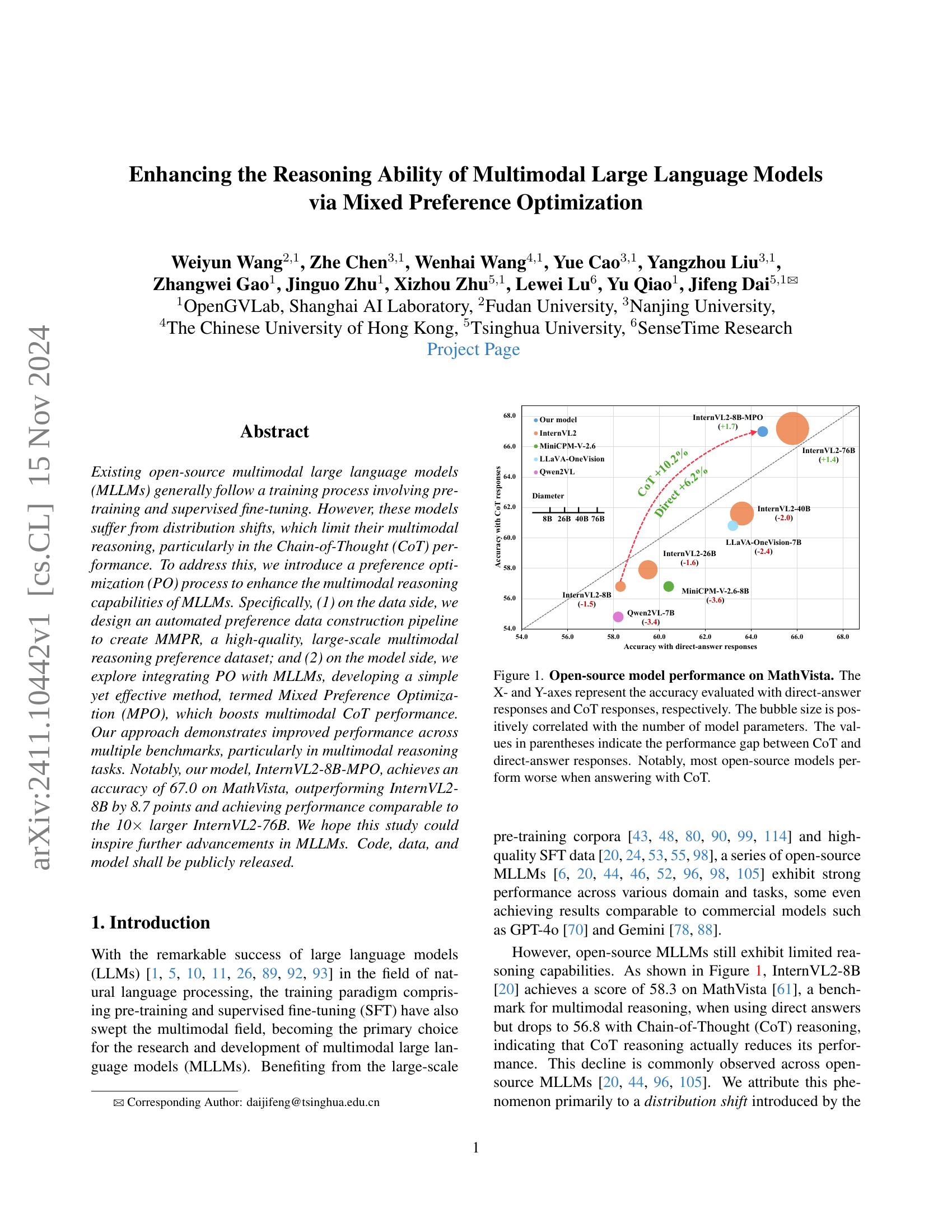

🔼 This figure displays the performance of various open-source multimodal large language models (MLLMs) on the MathVista benchmark, which assesses multimodal reasoning capabilities. The x-axis shows accuracy when models provide direct answers, and the y-axis shows accuracy when they use Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. Each bubble represents a different model, with its size proportional to the number of parameters. The numbers in parentheses next to each model indicate the difference in accuracy between direct answering and CoT reasoning. The plot reveals a concerning trend: most open-source models perform worse with CoT reasoning than with direct answering.

read the caption

Figure 1: Open-source model performance on MathVista. The X- and Y-axes represent the accuracy evaluated with direct-answer responses and CoT responses, respectively. The bubble size is positively correlated with the number of model parameters. The values in parentheses indicate the performance gap between CoT and direct-answer responses. Notably, most open-source models perform worse when answering with CoT.

| Task | Dataset |

|---|---|

| General VQA | VQAv2 [29], GQA [34], OKVQA [63], IconQA [59] |

| Science | AI2D [39], ScienceQA [60], M3CoT [16] |

| Chart | ChartQA [64], DVQA [37], MapQA [13] |

| Mathematics | GeoQA+ [12], CLEVR-Math [51], Geometry3K [58], GEOS [82], GeomVerse [38], Geo170K [27] |

| OCR | OCRVQA [68], InfoVQA [66], TextVQA [83], STVQA [8], SROIE [33] |

| Document | DocVQA [65] |

🔼 This table lists the various datasets used to create the MMPR (MultiModal Preference dataset), a dataset of image-text pairs with associated preference annotations used for training the multimodal language model. The datasets represent diverse tasks, including general visual question answering, science, charts, mathematics, optical character recognition (OCR), and documents. The inclusion of these diverse sources aims to ensure the MMPR dataset’s variety and robustness, facilitating the model’s ability to reason across a range of scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Datasets used to build our preference dataset. We collect images and instructions from various tasks to ensure the diversity of our dataset.

In-depth insights#

MMReasoning Enhancements#

MMReasoning Enhancements in multimodal large language models (MLLMs) represent a crucial area of ongoing research. Improving the reasoning capabilities of these models is vital for their broader applicability and real-world impact. The core challenge lies in bridging the gap between the model’s ability to process and understand multimodal data (text, images, etc.) and its capacity to perform complex reasoning tasks that involve integrating information from multiple modalities. Techniques like Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting have shown promise, yet MLLMs still struggle with distribution shifts and suffer performance drops when employing CoT. Preference Optimization (PO) emerges as a powerful technique to address these shortcomings by aligning model outputs with desired reasoning patterns, using preference signals rather than explicit reward models. Datasets like MMPR become critical for training these models, enabling them to learn from a large corpus of high-quality, multimodal reasoning preferences. The overall goal is to develop methods capable of improving performance not only on benchmark tasks, but also for addressing the problem of hallucinations and generally enhancing the quality of reasoning in real-world applications.

MPO: A Novel Approach#

The proposed Mixed Preference Optimization (MPO) presents a novel approach to enhance multimodal reasoning in large language models (LLMs). MPO cleverly combines supervised fine-tuning (SFT) with preference optimization losses, addressing the limitations of existing methods. This blend allows the model to learn not only the relative preference between different responses but also their absolute quality and the generation process of preferred responses. The use of DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) and BCO (Binary Classifier Optimization) as components within the MPO framework demonstrates a focus on computational efficiency and stability. By incorporating various Chain-of-Thought (CoT) approaches, MPO aims to improve reasoning effectiveness and reduce hallucinations. The comprehensive evaluation of MPO on diverse benchmarks supports its efficacy, particularly in multimodal reasoning tasks. The creation of MMPR, a large-scale, high-quality multimodal reasoning preference dataset, directly supports MPO’s training, providing significant improvements over models trained solely on SFT. This synergistic approach between data construction and a novel optimization technique showcases a thoughtful strategy to advance the capabilities of MLLMs.

MMPR Dataset Creation#

The creation of the MMPR dataset is a crucial aspect of this research, focusing on generating high-quality multimodal reasoning preference data. The process cleverly addresses the scarcity of such data by employing two main pipelines: a correctness-based pipeline for samples with clear ground truth and a DropoutNTP pipeline for samples without. The correctness-based pipeline leverages existing datasets with readily available answers to efficiently create positive and negative samples. DropoutNTP, a more innovative approach, uses a clever truncation and prediction method to generate preference pairs, reducing the reliance on ground truth and thus making the data generation process more scalable. The pipeline is designed to reduce costs while ensuring sufficient quality. MMPR’s data diversity is ensured by incorporating samples from diverse domains, such as general visual question answering, science, charts, mathematics, OCR, and documents. This multifaceted approach helps build a robust dataset that avoids bias and improves the generalizability and reasoning capabilities of MLLMs trained on it. This systematic and efficient approach to dataset creation serves as a significant contribution, facilitating future research on multimodal reasoning and preference optimization within the field of large language models.

Ablation Study Analysis#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model or process to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, an ‘Ablation Study Analysis’ section would dissect the impact of specific design choices. For example, it could explore variations in the preference optimization techniques, such as comparing direct preference optimization (DPO) with other algorithms. It might also analyze different chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting strategies or the impact of data set size and source diversity. A key insight would be the relative importance of each component. The analysis should not only report performance metrics but also offer explanations for observed trends. Strong ablation studies provide crucial evidence for the validity and robustness of the proposed model. They reveal which parts are essential and which are less critical, guiding future research and refinement. Furthermore, a robust analysis would consider the computational costs associated with different approaches and discuss the trade-offs between complexity and performance. In short, a well-executed and thoughtful ablation study clarifies the model’s inner workings and justifies its overall design. The goal is to demonstrate that the improvements are attributable to specific design choices rather than spurious effects.

Future Research Needs#

Future research should prioritize improving the efficiency and scalability of multimodal preference optimization. Developing more sophisticated methods for automatically generating high-quality preference data is crucial, reducing reliance on expensive and time-consuming manual annotation. Further exploration of different preference optimization algorithms and their relative strengths and weaknesses across various multimodal tasks is needed. Investigating the interplay between preference optimization and other training paradigms, such as reinforcement learning from human feedback, is essential. Additionally, research should focus on enhancing the robustness and generalizability of MLLMs trained with preference optimization, making them less susceptible to distribution shifts and more adaptable to diverse downstream applications. Finally, a deeper understanding of the limitations of current approaches and potential biases in preference data is necessary to ensure the development of truly fair and effective multimodal large language models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

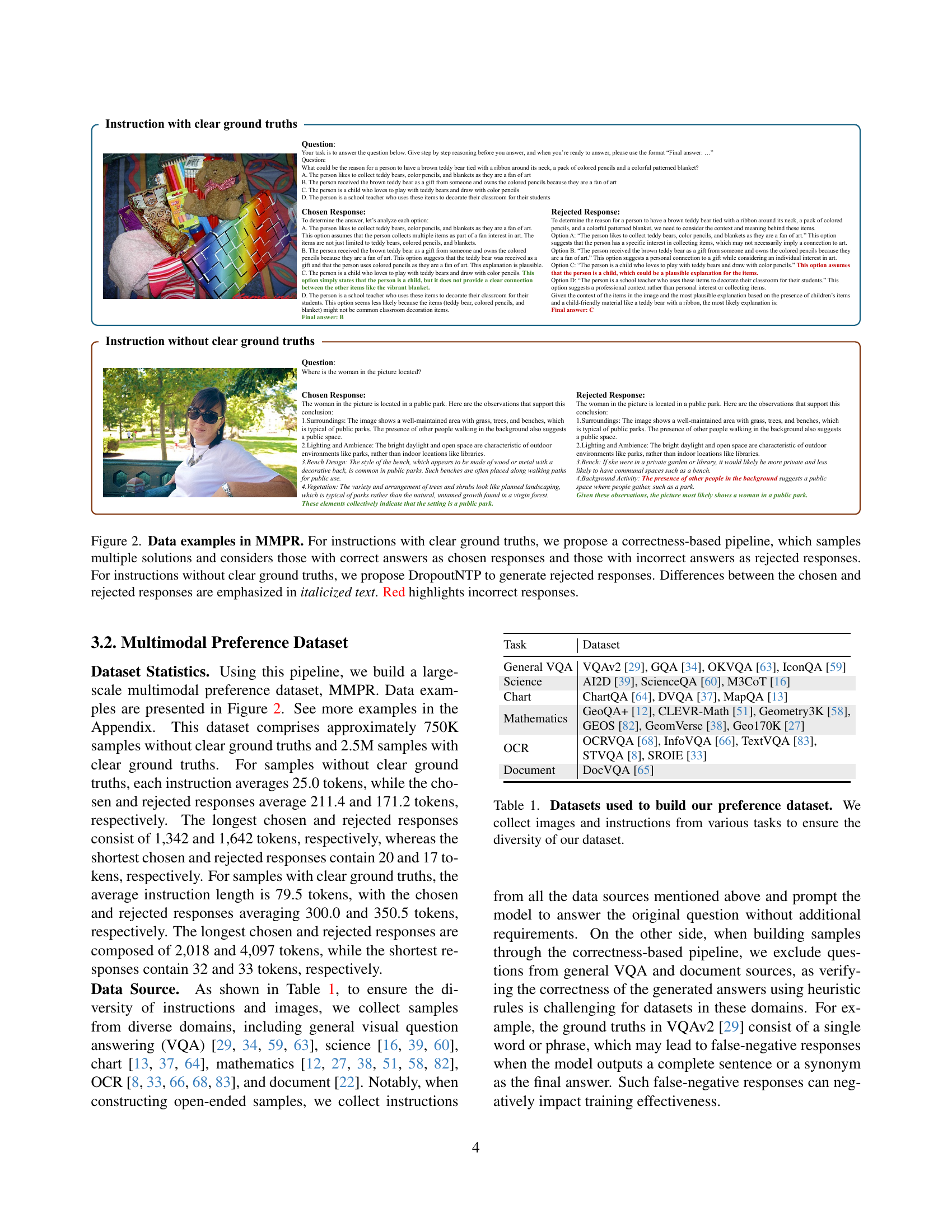

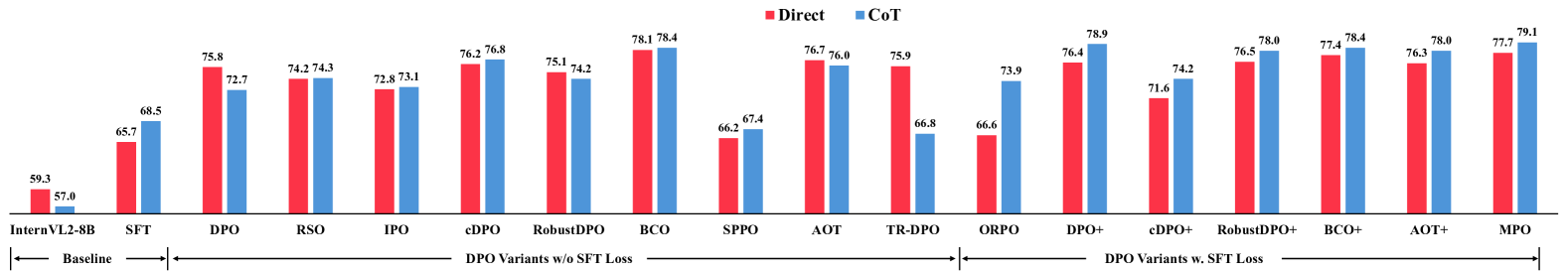

🔼 This figure showcases examples from the MMPR dataset, illustrating the two data generation pipelines used. The top half shows examples with clear ground truth. In these cases, the system generates multiple responses to the same prompt. Responses matching the ground truth are labeled as ‘chosen responses,’ while those that don’t match are ‘rejected responses.’ The bottom half presents examples where ground truth is unclear. Here, the ‘DropoutNTP’ method is used: the model generates a response, truncates it, and then attempts to complete the truncated response without the image context. This generated completion acts as the ‘rejected response’, while the original, complete response is the ‘chosen response’. Differences between chosen and rejected responses are highlighted in italics, and incorrect answers are highlighted in red.

read the caption

Figure 2: Data examples in MMPR. For instructions with clear ground truths, we propose a correctness-based pipeline, which samples multiple solutions and considers those with correct answers as chosen responses and those with incorrect answers as rejected responses. For instructions without clear ground truths, we propose DropoutNTP to generate rejected responses. Differences between the chosen and rejected responses are emphasized in italicized text. Red highlights incorrect responses.

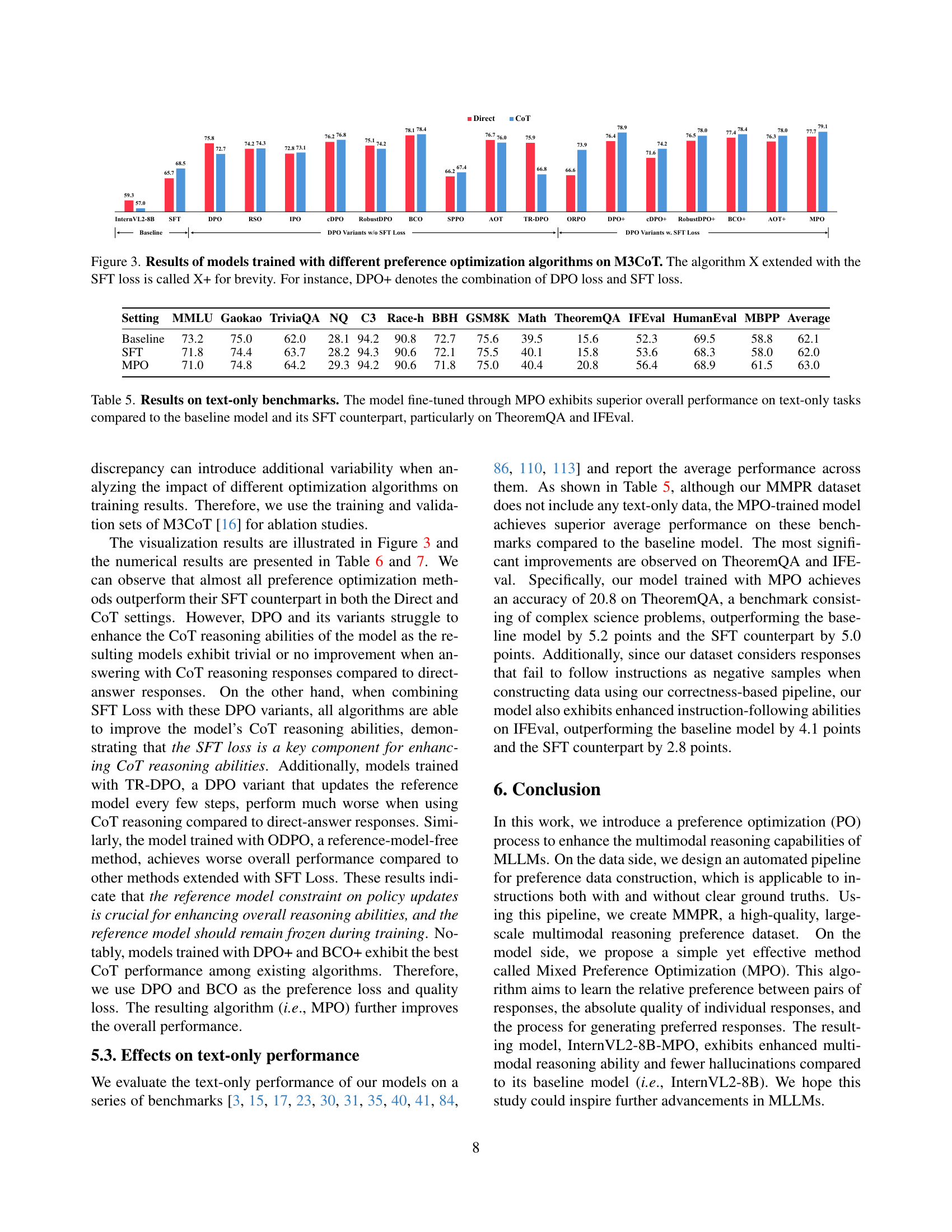

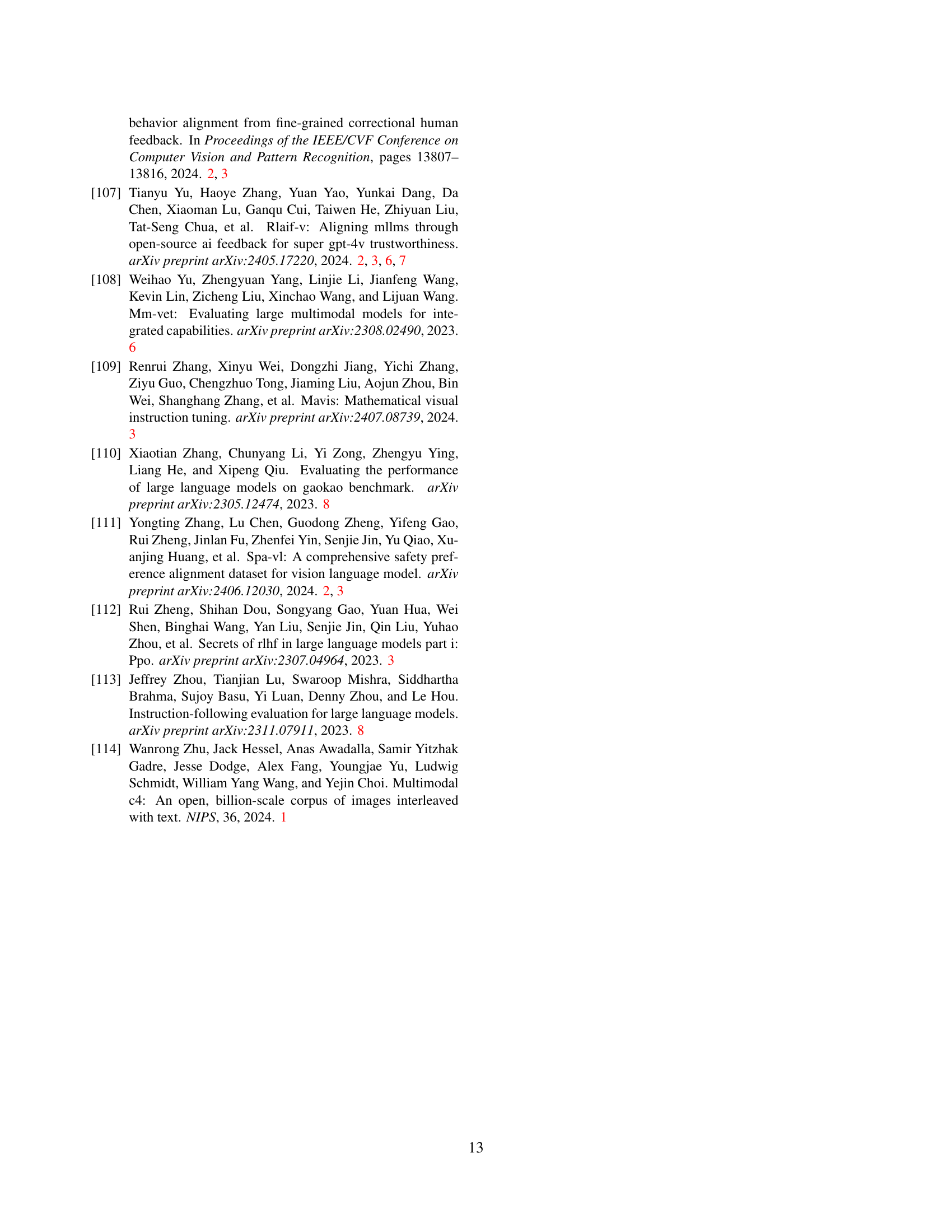

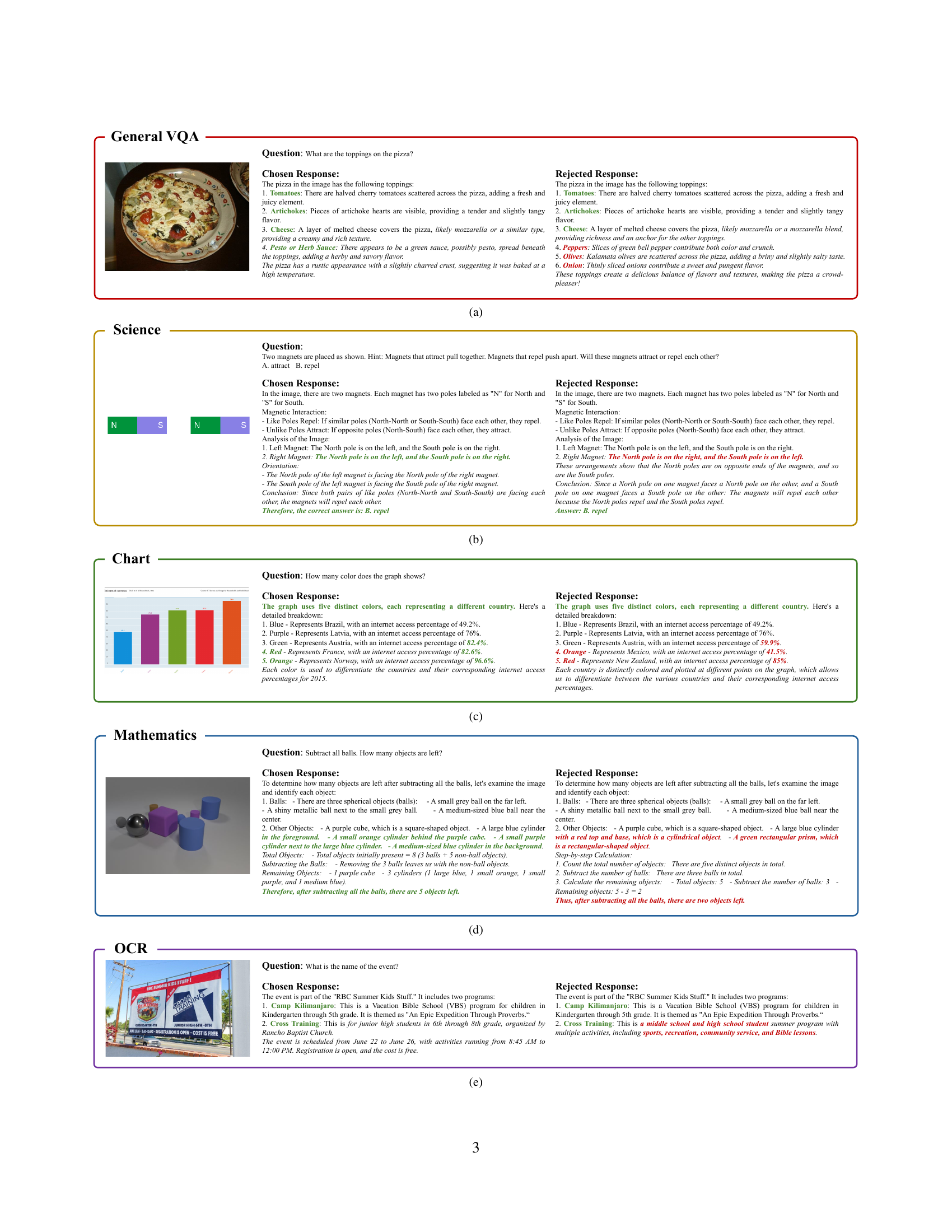

🔼 This figure displays the performance comparison of various preference optimization algorithms applied to the M3CoT benchmark. The algorithms tested include Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), its variants (RSO, IPO, CDPO, RobustDPO, BCO, SPPO, AOT, TR-DPO), and a version of each extended by incorporating the Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) loss (indicated by ‘+’). The graph compares the accuracy results for each method when using direct answers and when using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. This helps visualize how effectively each approach enhances the model’s ability to generate reasoned responses, highlighting the impact of the SFT loss on CoT reasoning performance.

read the caption

Figure 3: Results of models trained with different preference optimization algorithms on M3CoT. The algorithm X extended with the SFT loss is called X+ for brevity. For instance, DPO+ denotes the combination of DPO loss and SFT loss.

🔼 This figure shows examples from the MMPR dataset. Specifically, it presents examples of instructions with and without clear ground truth. For instructions with clear ground truths, a correctness-based pipeline is used which samples multiple solutions, labelling those matching the ground truth as ‘chosen responses’ and those that don’t as ‘rejected responses’. For instructions without clear ground truths, a DropoutNTP pipeline is used. The figure highlights the differences between chosen and rejected responses to illustrate how the dataset was constructed.

read the caption

(a)

🔼 This figure shows two magnets with their north and south poles labeled. The north poles of both magnets face each other, and the south poles of both magnets face each other. The caption indicates that this arrangement will cause the magnets to repel.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 The figure shows a bar chart visualizing the number of occurrences of different colors in the ‘fence’ row of a dataset. Each color represents a category (legs, index, engine, total), and the bar height indicates the value associated with that color in the ‘fence’ row. This illustrates the numerical data distribution within the specified row, revealing the relative frequencies or counts of each category.

read the caption

(c)

🔼 The figure shows examples from the MultiModal PReference (MMPR) dataset. Specifically, it displays examples from the OCR (Optical Character Recognition) category of the dataset. The top shows the question: ‘What is the total amount of this receipt?’, along with the chosen and rejected responses generated by a multimodal language model. The chosen response correctly calculates the total amount based on the invoice image, while the rejected response makes an incorrect calculation and includes extraneous information. This illustrates how the dataset differentiates between high-quality, correct reasoning and lower-quality, incorrect reasoning for multimodal tasks.

read the caption

(d)

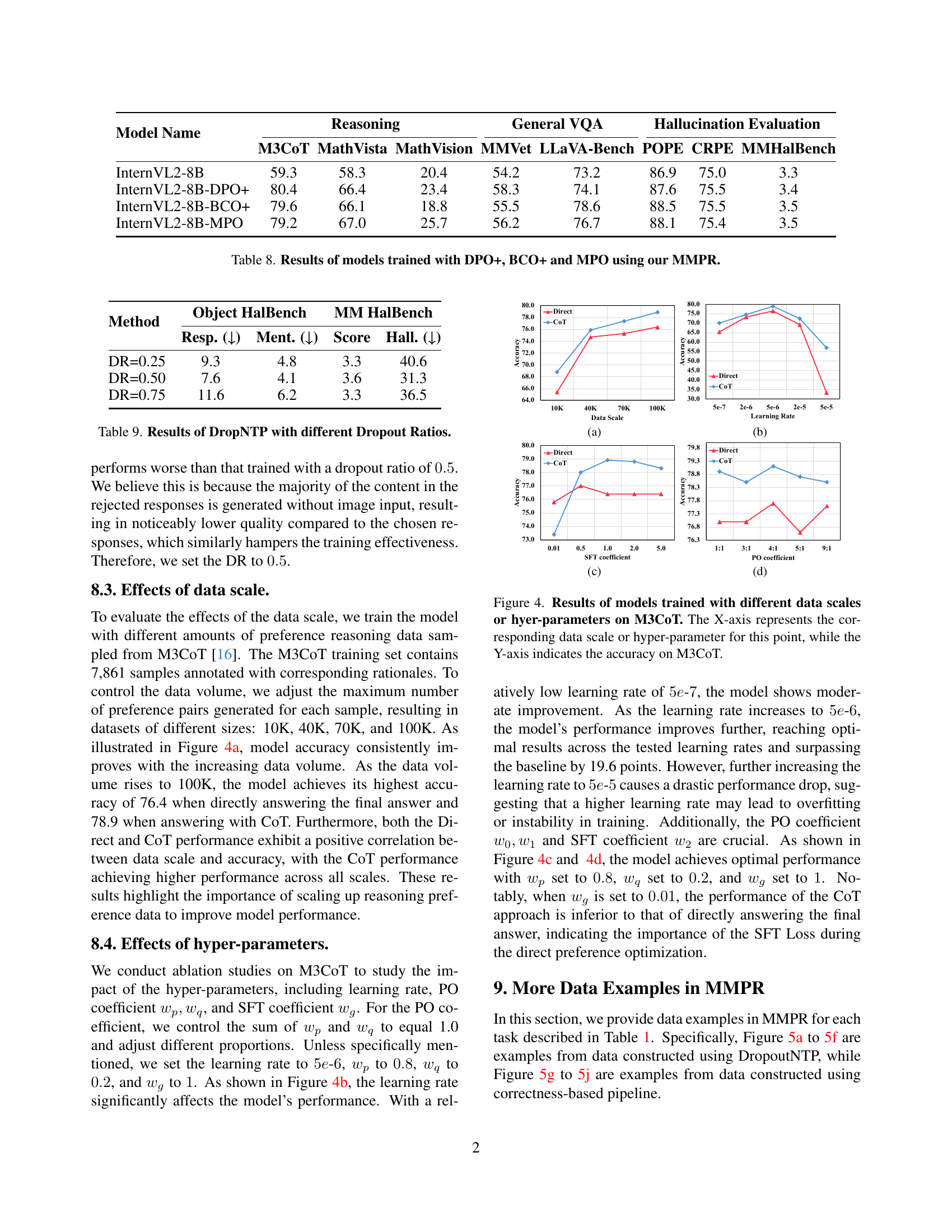

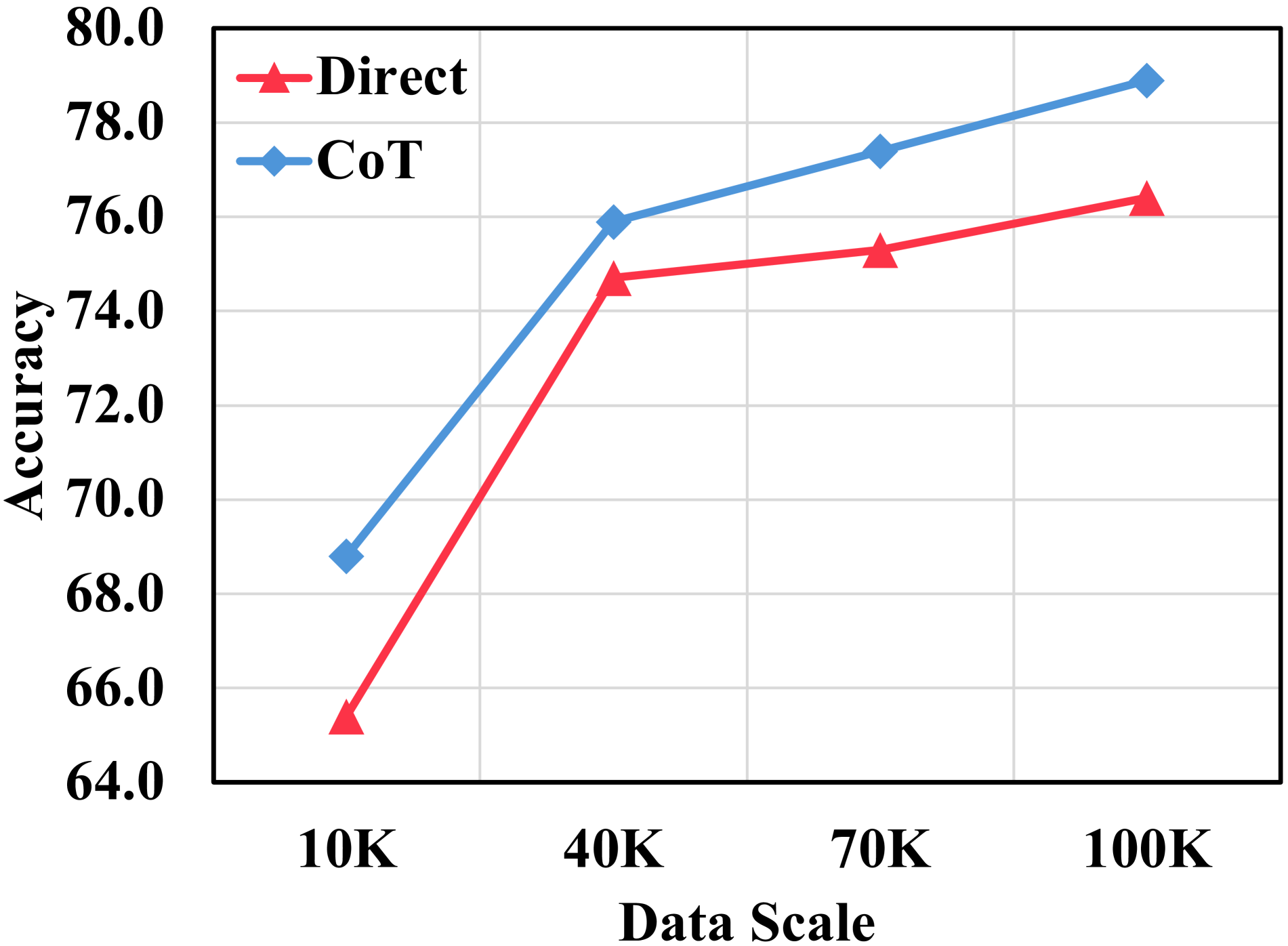

🔼 This figure displays the performance of models trained on varying amounts of data and different hyperparameters, specifically focusing on the M3CoT benchmark. The graphs illustrate how changes in training data volume and hyperparameter settings (learning rate, PO coefficient, and SFT coefficient) affect the accuracy of the model. The x-axis of each graph shows the variable being tested (data scale or hyperparameter), while the y-axis indicates the accuracy achieved on the M3CoT benchmark. Separate lines represent the results for models making direct answers and those using chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning.

read the caption

Figure 4: Results of models trained with different data scales or hyer-parameters on M3CoT. The X-axis represents the corresponding data scale or hyper-parameter for this point, while the Y-axis indicates the accuracy on M3CoT.

🔼 The figure shows examples of data samples from the MMPR dataset. Panel (a) shows an example with clear ground truth, using a correctness-based pipeline. Multiple response options to the same question are provided, where one response matches the ground truth and serves as the ‘chosen response’, while the others are incorrect and are labelled ‘rejected responses’. The differences between the chosen and rejected responses are highlighted in italicized text. Incorrect parts of rejected responses are highlighted in red. Panel (b) shows an example without clear ground truth, instead using a DropoutNTP pipeline. A generated response is truncated, and the model is prompted to complete it without image input. This incomplete response becomes the ‘rejected response’, while the original, complete response is the ‘chosen response’. Again, differences are highlighted in italicized text, and incorrect parts of the rejected response in red.

read the caption

(a)

🔼 This figure shows two bar magnets placed with their north poles facing each other. The caption explains the principles of magnetic attraction and repulsion: like poles repel, and unlike poles attract. The image is used to illustrate that because the north poles of both magnets are facing each other, the magnets will repel each other. This is a visual aid to support the explanation of magnetic forces in a section of the paper that discusses multimodal reasoning.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 The figure shows a bar chart visualizing the internet access percentage for five different countries in 2015. Each country is represented by a unique color, enabling easy differentiation between the countries and their internet access statistics. The chart’s structure makes it simple to compare the internet access levels across the selected nations.

read the caption

(c)

🔼 This figure shows examples from the MultiModal Preference dataset (MMPR). Specifically, it displays samples from the ‘Mathematics’ domain where the task is to determine the perimeter of triangle ABO given information about quadrilateral ABCD with intersecting diagonals. The ‘Chosen Response’ provides a step-by-step solution that leverages geometric properties and equations. The ‘Rejected Response’ demonstrates an alternative approach, highlighting the differences in reasoning processes and correctness in reaching the solution.

read the caption

(d)

🔼 This figure shows examples from the MMPR dataset. Specifically, it displays examples of instructions with and without clear ground truths. For instructions with clear ground truths, a correctness-based pipeline was used, where responses matching the ground truth are considered chosen responses and those that don’t match are rejected responses. For instructions without clear ground truths, the DropoutNTP pipeline was used. The chosen and rejected responses are presented, with differences highlighted to illustrate how the pipeline generates preference pairs for training. Red highlighting indicates incorrect responses.

read the caption

(e)

🔼 This figure shows examples from the MultiModal Preference dataset (MMPR). Specifically, it displays examples of instructions and their corresponding chosen and rejected responses from the OCR (Optical Character Recognition) domain. The chosen responses provide accurate interpretations of the image content, while the rejected responses contain errors or hallucinations. This visual aids in understanding the dataset’s composition and the differences between preferable and less preferable responses used for model training.

read the caption

(f)

🔼 This figure shows examples from the MultiModal Preference dataset (MMPR). Specifically, it displays examples of instructions and responses from the chart domain. The left side shows a ‘chosen response’ which is a correct and well-reasoned answer. The right side shows a ‘rejected response’ which is either incorrect or poorly reasoned. The responses are paired to illustrate the preference data used to train the model. The visual is a chart showing data points with different colors and the instruction asks about the color-coding of the chart and the value related to a specific color.

read the caption

(g)

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of models trained with different data scales on the M3CoT benchmark. The x-axis represents the size of the training dataset (10K, 40K, 70K, and 100K samples). The y-axis shows the accuracy achieved on the M3CoT benchmark. Two lines are plotted: one for the model’s performance using direct answers and the other for its performance using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. The graph shows a clear positive correlation between the amount of training data and the model’s accuracy, indicating that scaling up the reasoning preference data improves the model’s performance.

read the caption

(h)

🔼 The figure displays the performance of various open-source multimodal large language models (MLLMs) on the MathVista benchmark. The x-axis represents accuracy with direct-answer responses, and the y-axis represents accuracy using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning. Each bubble represents a different model; the size of the bubble is correlated with the number of parameters in the model. The plot reveals a common trend among open-source MLLMs: performance decreases when CoT reasoning is used, indicating a distribution shift problem between training and inference. The authors’ model, InternVL2-8B-MPO, is shown to significantly outperform other models, achieving results comparable to much larger models.

read the caption

(i)

More on tables

| Dataset | Citation |

|---|---|

| GeoQA+ | [12] |

| CLEVR-Math | [51] |

| Geometry3K | [58] |

| GEOS | [82] |

| GeomVerse | [38] |

| Geo170K | [27] |

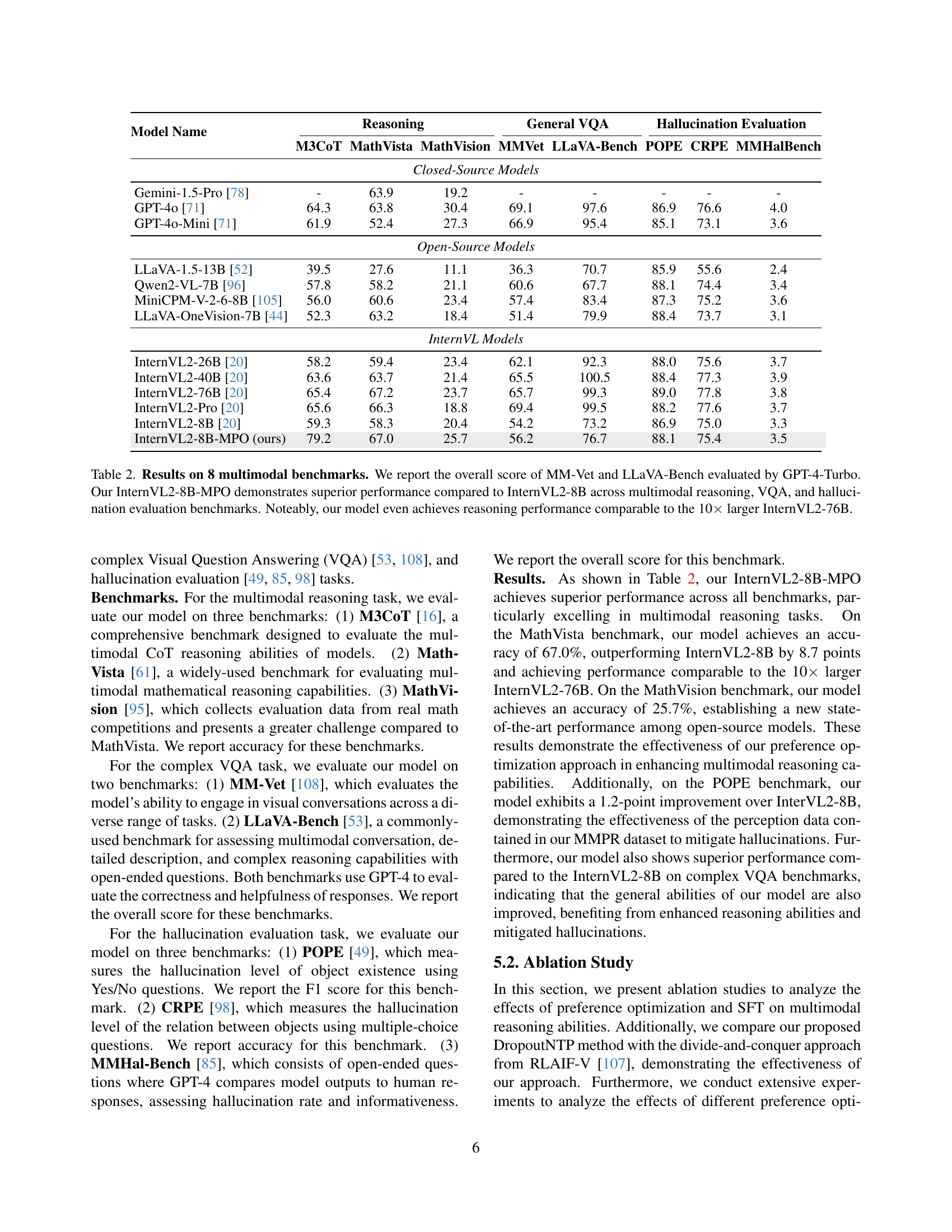

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive comparison of various multimodal large language models (MLLMs) across eight benchmark datasets. The benchmarks assess different aspects of MLLM capabilities, including reasoning, visual question answering (VQA), and hallucination. The table showcases the performance of several open-source MLLMs, including different variants of InternVL2, along with closed-source models like Gemini and GPT-4 for reference. The key finding is that InternVL2-8B-MPO, the model enhanced by the authors’ Mixed Preference Optimization (MPO) technique, significantly outperforms the base InternVL2-8B model, achieving performance on par with much larger models like InternVL2-76B.

read the caption

Table 2: Results on 8 multimodal benchmarks. We report the overall score of MM-Vet and LLaVA-Bench evaluated by GPT-4-Turbo. Our InternVL2-8B-MPO demonstrates superior performance compared to InternVL2-8B across multimodal reasoning, VQA, and hallucination evaluation benchmarks. Noteably, our model even achieves reasoning performance comparable to the 10×\times× larger InternVL2-76B.

| Model | Citation |

|---|---|

| OCRVQA | [68] |

| InfoVQA | [66] |

| TextVQA | [83] |

| STVQA | [8] |

| SROIE | [33] |

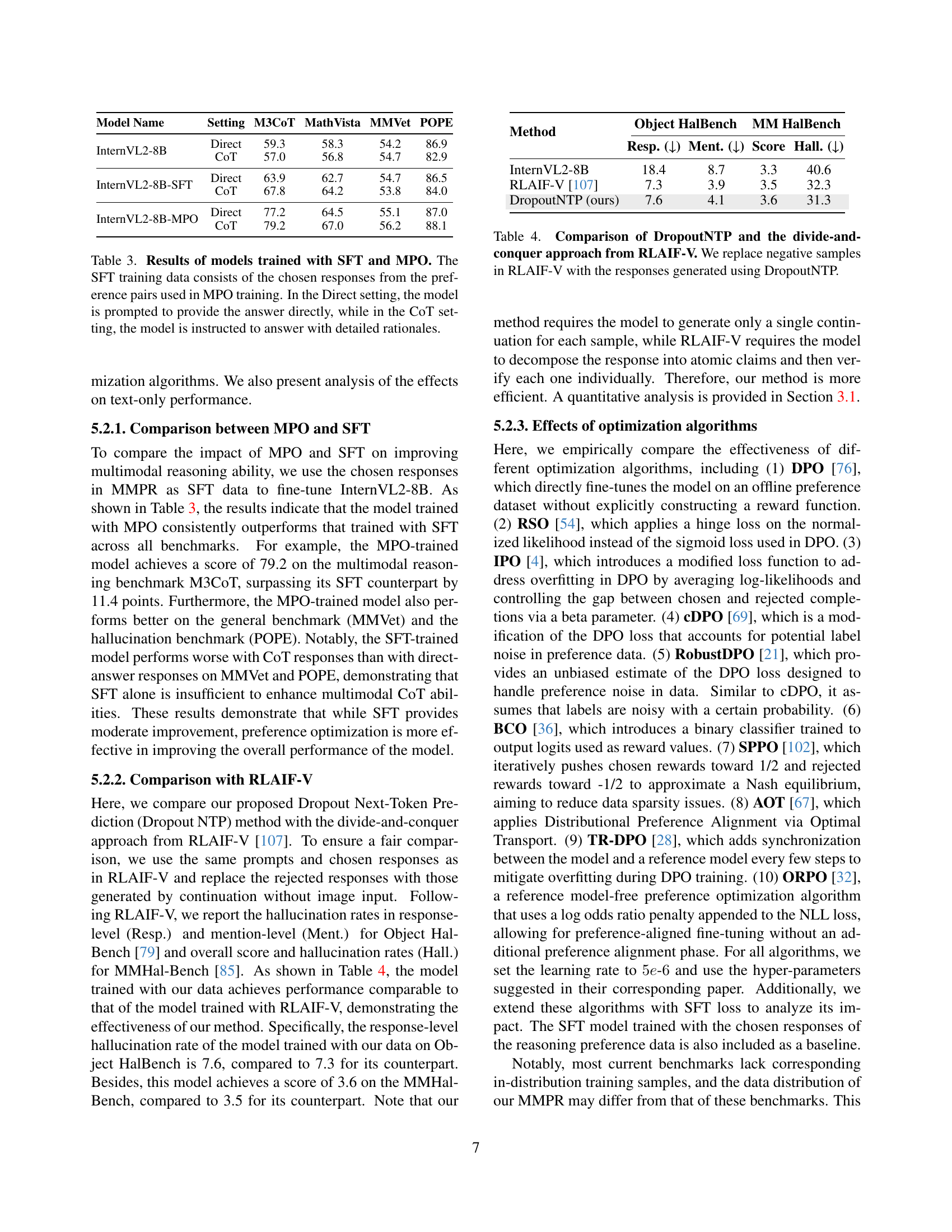

🔼 This table compares the performance of two models: one trained with supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and another trained with the proposed mixed preference optimization (MPO) method. Both models are evaluated on their ability to answer questions directly (Direct) and using chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. The SFT model uses chosen responses from the MPO training data for its training. The table showcases the accuracy of both methods across multiple benchmark datasets, highlighting the difference in performance between Direct and CoT approaches for both training methods.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of models trained with SFT and MPO. The SFT training data consists of the chosen responses from the preference pairs used in MPO training. In the Direct setting, the model is prompted to provide the answer directly, while in the CoT setting, the model is instructed to answer with detailed rationales.

| Model Name | M3CoT | MathVista | MathVision | MMVet | LLaVA-Bench | POPE | CRPE | MMHalBench |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-Source Models | ||||||||

| Gemini-1.5-Pro [78] | - | 63.9 | 19.2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| GPT-4o [71] | 64.3 | 63.8 | 30.4 | 69.1 | 97.6 | 86.9 | 76.6 | 4.0 |

| GPT-4o-Mini [71] | 61.9 | 52.4 | 27.3 | 66.9 | 95.4 | 85.1 | 73.1 | 3.6 |

| Open-Source Models | ||||||||

| LLaVA-1.5-13B [52] | 39.5 | 27.6 | 11.1 | 36.3 | 70.7 | 85.9 | 55.6 | 2.4 |

| Qwen2-VL-7B [96] | 57.8 | 58.2 | 21.1 | 60.6 | 67.7 | 88.1 | 74.4 | 3.4 |

| MiniCPM-V-2-6-8B [105] | 56.0 | 60.6 | 23.4 | 57.4 | 83.4 | 87.3 | 75.2 | 3.6 |

| LLaVA-OneVision-7B [44] | 52.3 | 63.2 | 18.4 | 51.4 | 79.9 | 88.4 | 73.7 | 3.1 |

| InternVL Models | ||||||||

| InternVL2-26B [20] | 58.2 | 59.4 | 23.4 | 62.1 | 92.3 | 88.0 | 75.6 | 3.7 |

| InternVL2-40B [20] | 63.6 | 63.7 | 21.4 | 65.5 | 100.5 | 88.4 | 77.3 | 3.9 |

| InternVL2-76B [20] | 65.4 | 67.2 | 23.7 | 65.7 | 99.3 | 89.0 | 77.8 | 3.8 |

| InternVL2-Pro [20] | 65.6 | 66.3 | 18.8 | 69.4 | 99.5 | 88.2 | 77.6 | 3.7 |

| InternVL2-8B [20] | 59.3 | 58.3 | 20.4 | 54.2 | 73.2 | 86.9 | 75.0 | 3.3 |

| InternVL2-8B-MPO (ours) | 79.2 | 67.0 | 25.7 | 56.2 | 76.7 | 88.1 | 75.4 | 3.5 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of two methods for generating negative samples in a multimodal preference optimization dataset: DropoutNTP (a novel method proposed in this paper) and the divide-and-conquer approach from RLAIF-V (a previous work). Specifically, it shows the hallucination rates (in response-level and mention-level) on the Object HalBench benchmark, as well as the overall score and hallucination rates on the MMHalBench benchmark. The goal is to demonstrate the effectiveness of DropoutNTP, which achieves comparable performance to RLAIF-V’s more complex method, while being simpler and more efficient.

read the caption

Table 4: Comparison of DropoutNTP and the divide-and-conquer approach from RLAIF-V. We replace negative samples in RLAIF-V with the responses generated using DropoutNTP.

| Model Name | Setting | M3CoT | MathVista | MMVet | POPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InternVL2-8B | Direct | 59.3 | 58.3 | 54.2 | 86.9 |

| CoT | 57.0 | 56.8 | 54.7 | 82.9 | |

| InternVL2-8B-SFT | Direct | 63.9 | 62.7 | 54.7 | 86.5 |

| CoT | 67.8 | 64.2 | 53.8 | 84.0 | |

| InternVL2-8B-MPO | Direct | 77.2 | 64.5 | 55.1 | 87.0 |

| CoT | 79.2 | 67.0 | 56.2 | 88.1 |

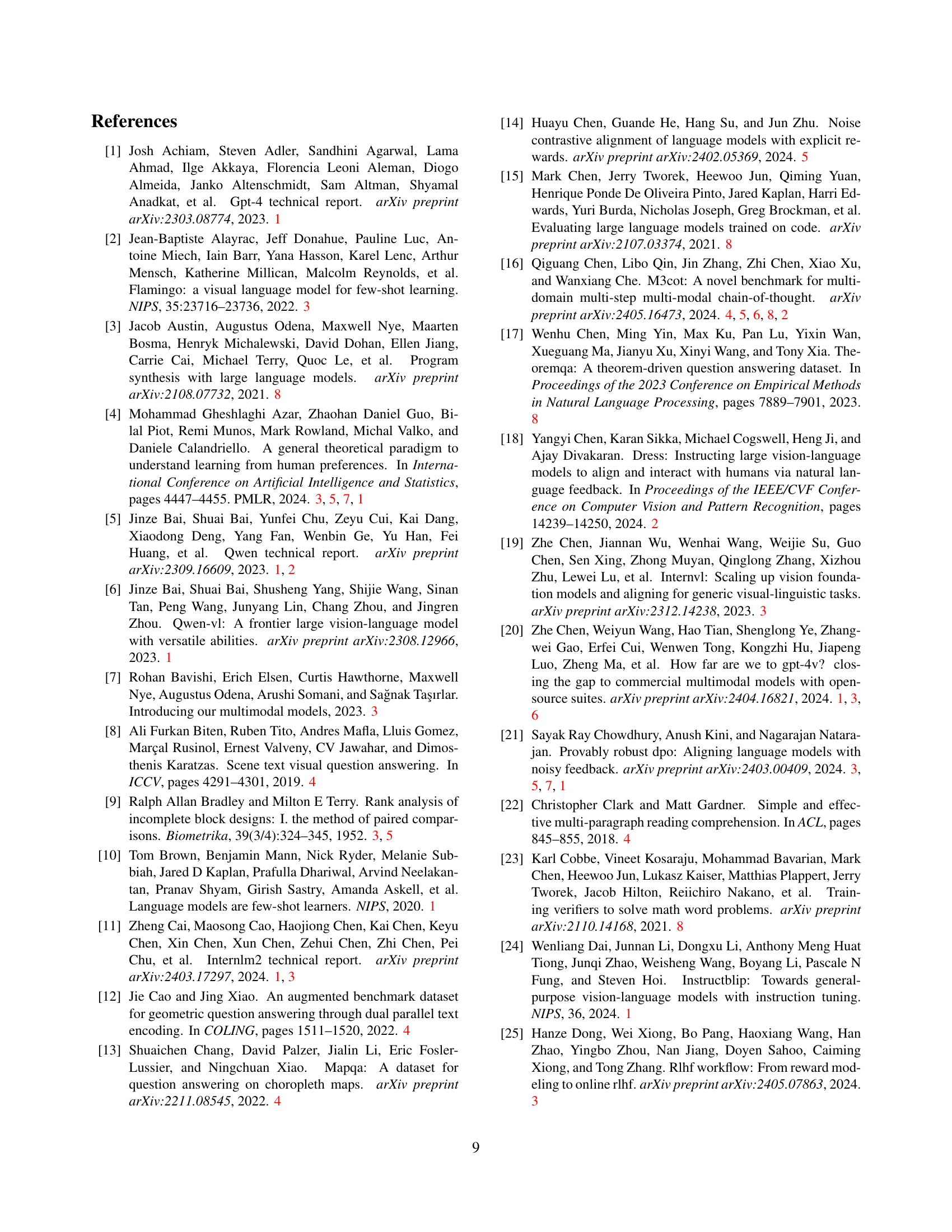

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the performance of language models on various text-only benchmarks. The models evaluated include a baseline model, a model fine-tuned with supervised fine-tuning (SFT), and a model fine-tuned using the proposed mixed preference optimization (MPO) method. The benchmarks cover a range of tasks, and the table shows the performance scores for each model on each benchmark. The MPO model demonstrates significantly improved performance compared to both the baseline model and the SFT model, especially on TheoremQA and IFEval.

read the caption

Table 5: Results on text-only benchmarks. The model fine-tuned through MPO exhibits superior overall performance on text-only tasks compared to the baseline model and its SFT counterpart, particularly on TheoremQA and IFEval.

| Method | Object HalBench | MM HalBench | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resp. (↓) | Ment. (↓) | Score | Hall. (↓) | |||

| InternVL2-8B | 18.4 | 8.7 | 3.3 | 40.6 | ||

| RLAIF-V [107] | 7.3 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 32.3 | ||

| DropoutNTP (ours) | 7.6 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 31.3 |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating various preference optimization algorithms applied to the M3CoT benchmark. For each algorithm (DPO, RSO, IPO, CDPO, RobustDPO, BCO, SPPO, AOT, TR-DPO), the table shows the accuracy scores achieved when the model generates responses directly (Direct) and when it uses chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. The final column, Δ, indicates the performance difference between CoT and direct responses, providing insights into how each optimization method affects the model’s reasoning capabilities. A positive Δ value suggests CoT improves the model while a negative Δ indicates CoT reasoning reduces performance.

read the caption

Table 6: Results of models trained with different preference optimization algorithms on M3CoT. ΔΔ\Deltaroman_Δ represents the performance gap between CoT responses and direct-answer responses.

| Setting | MMLU | Gaokao | TriviaQA | NQ | C3 | Race-h | BBH | GSM8K | Math | TheoremQA | IFEval | HumanEval | MBPP | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 73.2 | 75.0 | 62.0 | 28.1 | 94.2 | 90.8 | 72.7 | 75.6 | 39.5 | 15.6 | 52.3 | 69.5 | 58.8 | 62.1 |

| SFT | 71.8 | 74.4 | 63.7 | 28.2 | 94.3 | 90.6 | 72.1 | 75.5 | 40.1 | 15.8 | 53.6 | 68.3 | 58.0 | 62.0 |

| MPO | 71.0 | 74.8 | 64.2 | 29.3 | 94.2 | 90.6 | 71.8 | 75.0 | 40.4 | 20.8 | 56.4 | 68.9 | 61.5 | 63.0 |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments on the M3CoT benchmark, comparing various preference optimization algorithms enhanced with supervised fine-tuning (SFT) loss. Each algorithm (DPO, RSO, IPO, CDPO, RobustDPO, BCO, SPPO, AOT, TR-DPO, ORPO) was tested in its original form and then with the addition of SFT loss (denoted by ‘+’). The table shows the performance of each model configuration in terms of accuracy on direct-answer and chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning tasks, and calculates the difference (Δ) between the two. The purpose is to evaluate the effectiveness of incorporating SFT loss into different preference optimization approaches for improving the reasoning abilities of multimodal large language models, particularly in CoT scenarios.

read the caption

Table 7: Results of models trained with different preference optimization algorithms extended with SFT Loss on M3CoT. The algorithm X extended with the SFT Loss is called X+ for brevity. For instance, DPO+ is the combination of DPO and SFT loss.

| Method | Direct | CoT | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|

| InternVL2-8B | 59.3 | 57.0 | -2.3 |

| SFT | 65.7 | 68.5 | +2.8 |

| DPO [76] | 75.8 | 72.7 | -3.1 |

| RSO [54] | 74.2 | 74.3 | +0.1 |

| IPO [4] | 72.8 | 73.1 | +0.3 |

| cDPO [69] | 76.2 | 76.8 | +0.6 |

| RobustDPO [21] | 75.1 | 74.2 | -0.9 |

| BCO [36] | 78.1 | 78.4 | +0.3 |

| SPPO [102] | 66.2 | 67.4 | +1.2 |

| AOT [67] | 76.7 | 76.0 | -0.7 |

| TR-DPO [28] | 75.9 | 66.8 | -9.1 |

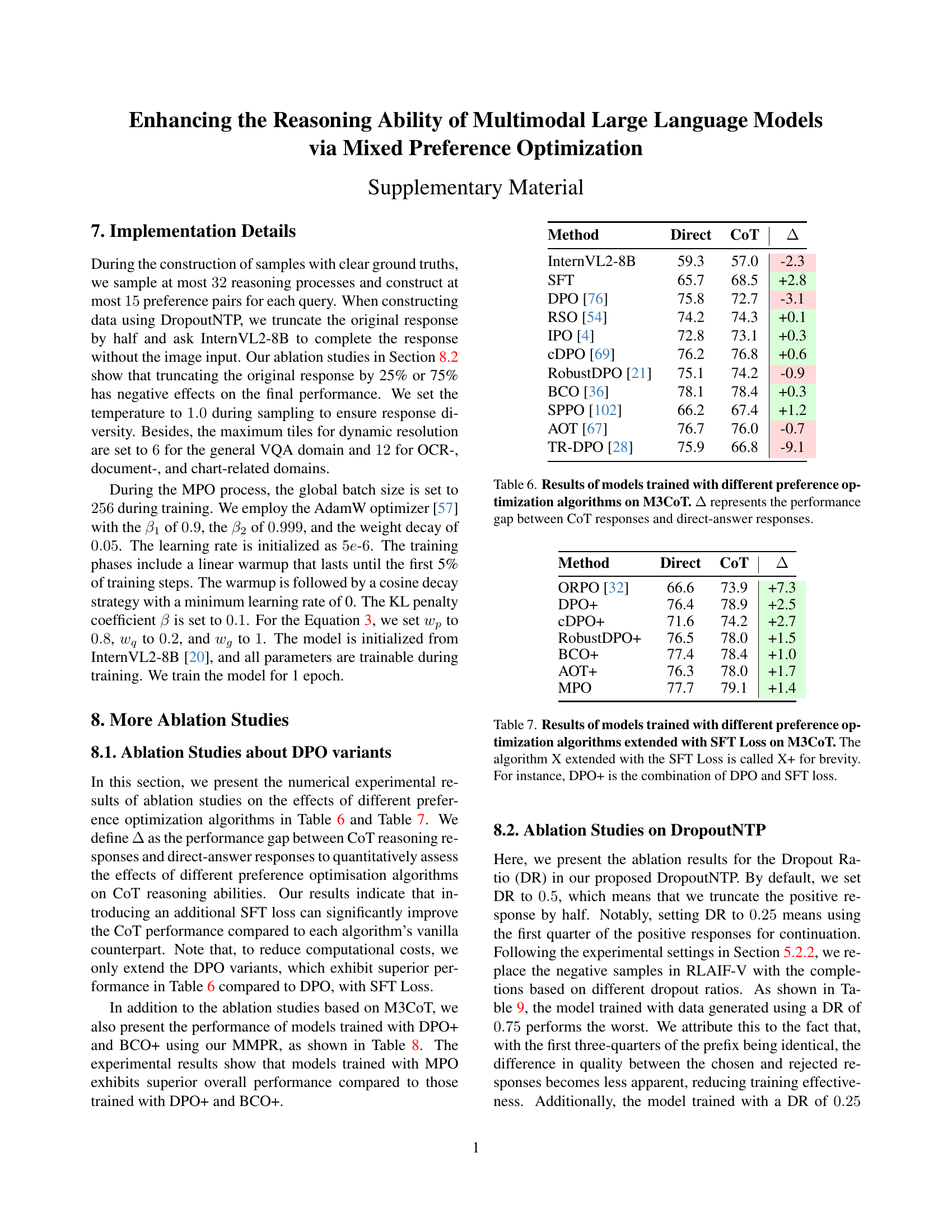

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of three different multimodal large language models (MLLMs) on eight benchmark datasets. The models are InternVL2-8B (baseline), InternVL2-8B-DPO+, InternVL2-8B-BCO+, and InternVL2-8B-MPO. InternVL2-8B-DPO+ and InternVL2-8B-BCO+ are fine-tuned using the Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) and Binary Classifier Optimization (BCO) methods, respectively. InternVL2-8B-MPO uses the Mixed Preference Optimization (MPO) method introduced in the paper. The benchmarks cover various multimodal reasoning tasks and hallucination evaluation. The results show that the MPO model significantly outperforms the baseline and the DPO+ and BCO+ models on most of the benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 8: Results of models trained with DPO+, BCO+ and MPO using our MMPR.

| Method | Direct | CoT | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORPO [32] | 66.6 | 73.9 | +7.3 |

| DPO+ | 76.4 | 78.9 | +2.5 |

| cDPO+ | 71.6 | 74.2 | +2.7 |

| RobustDPO+ | 76.5 | 78.0 | +1.5 |

| BCO+ | 77.4 | 78.4 | +1.0 |

| AOT+ | 76.3 | 78.0 | +1.7 |

| MPO | 77.7 | 79.1 | +1.4 |

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the effect of varying the dropout ratio in the Dropout Next-Token Prediction (DropoutNTP) method used for generating negative samples in the MMPR dataset. The dropout ratio determines the portion of a positive response that’s truncated before the model attempts completion. The table shows the impact of using different dropout ratios (0.25, 0.50, and 0.75) on the hallucination rates measured by two different metrics: response-level and mention-level hallucinations. The results are presented for the Object HalBench and MMHalBench datasets.

read the caption

Table 9: Results of DropNTP with different Dropout Ratios.

Full paper#