↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Many large language models (LLMs) struggle with accurate and efficient tokenization of Indian languages, impacting their overall performance. This is particularly true for less-resourced languages where existing tokenization methods may not be optimal. The lack of a comprehensive evaluation of tokenizers across all Indian languages creates a knowledge gap, limiting improvements in model development.

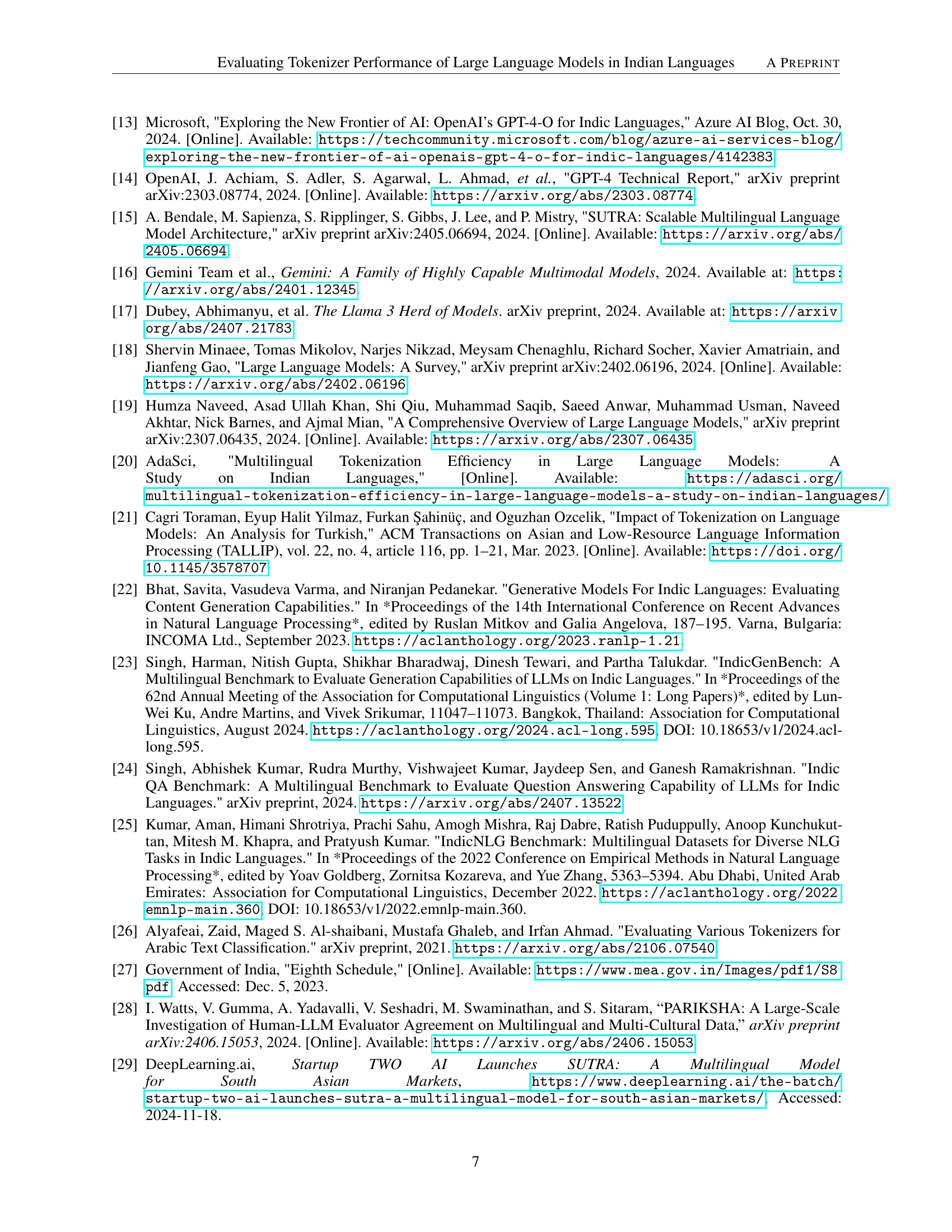

This research paper presents a comprehensive evaluation of 12 different LLMs’ tokenizers across all 22 official Indian languages. The researchers used Normalized Sequence Length (NSL) to measure the efficiency of each tokenizer. Their findings revealed that the SUTRA tokenizer significantly outperformed all other models, especially for Indic languages. This research highlights the importance of developing better tokenization strategies for Indic languages and offers valuable insights for future LLM development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on multilingual and low-resource language models, especially those focusing on Indian languages. It addresses the critical need for effective tokenization in LLMs, highlighting the performance gap of existing models and proposing solutions. The findings will directly influence the design and optimization of future tokenization strategies, leading to improved model efficiency and performance. It also opens new avenues for research in cross-lingual transfer learning and developing more robust tokenization techniques tailored for diverse linguistic structures.

Visual Insights#

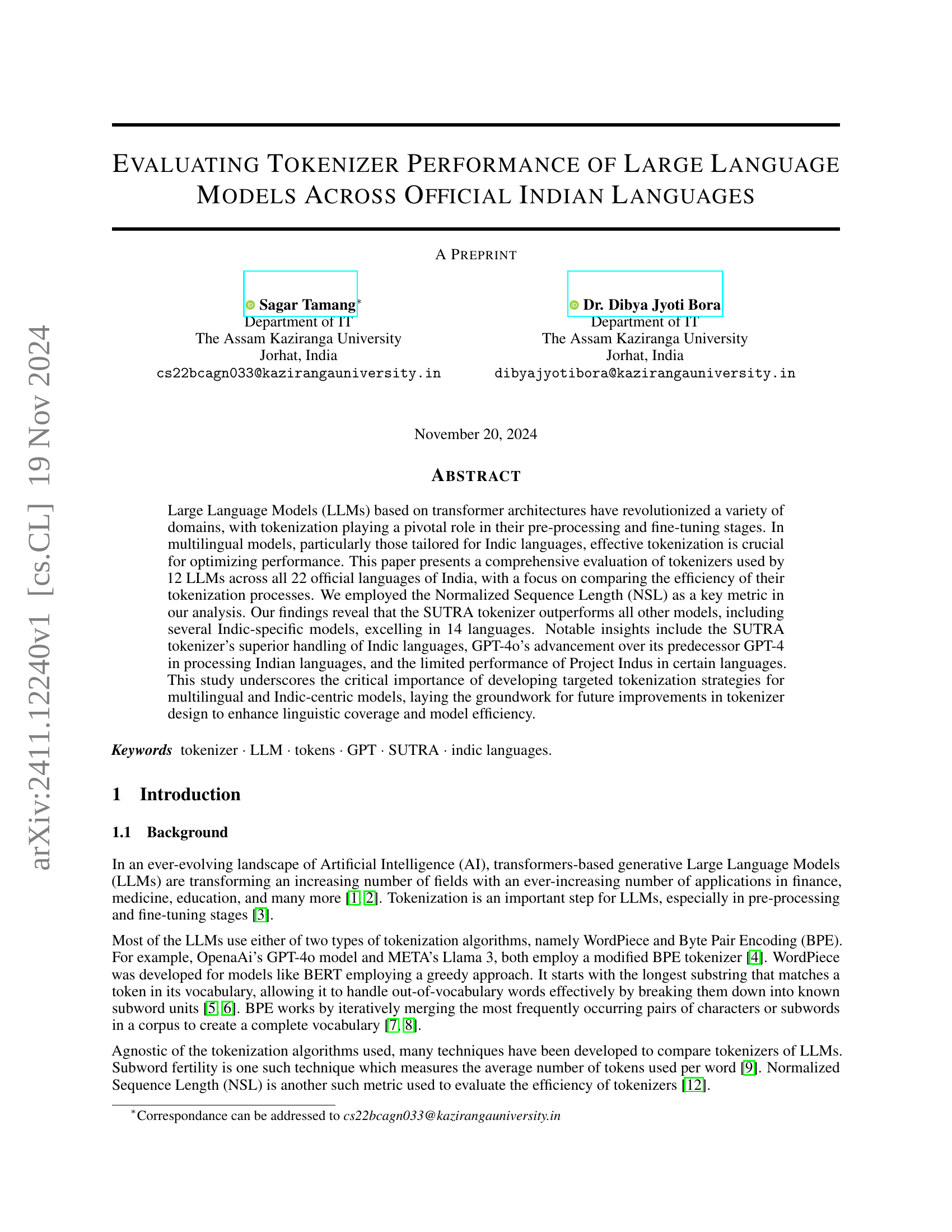

🔼 This figure illustrates the evaluation pipeline used in the study. The process begins with collecting example texts in all 22 official Indian languages. These texts are then fed into the tokenizers of 12 different large language models (LLMs). The resulting tokenized outputs are evaluated using a chosen metric (likely Normalized Sequence Length, as described in the paper). Finally, the results are compiled into leaderboards to compare the performance of each LLM’s tokenizer across the different languages.

read the caption

Figure 1: Evaluation pipeline: (1) We collect example texts for all 22 languages. (2) We send the example texts to the LLMs’ tokenizer. (3) Evaluate the tokenized outputs. (4) We construct leaderboards using our evaluation.

| Models | Languages | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | All | Proprietary |

| GPT-4 | All | Proprietary |

| TWO/sutra-mlt256-v2 | All | Proprietary |

| microsoft/Phi-3.5-MoE-instruct | All | Open-weights |

| meta-llama/Llama-3.1-405B-FP8 | All | Open-weights |

| ai4bharat/Airavata | All | Open-weights |

| CohereForAI/aya-23-35B | All | Open-weights |

| MBZUAI/Llama-3-Nanda-10B-Chat | All | Open-weights |

| nickmalhotra/ProjectIndus | All | Open-weights |

| sarvamai/OpenHathi-7B-Hi-v0.1-Base | All | Open-weights |

| Telugu-LLM-Labs/Indic-gemma-7b-finetuned-sft-Navarasa-2.0 | All | Open-weights |

| marathi-llm/MahaMarathi-7B-v24.01-Base | All | Open-weights |

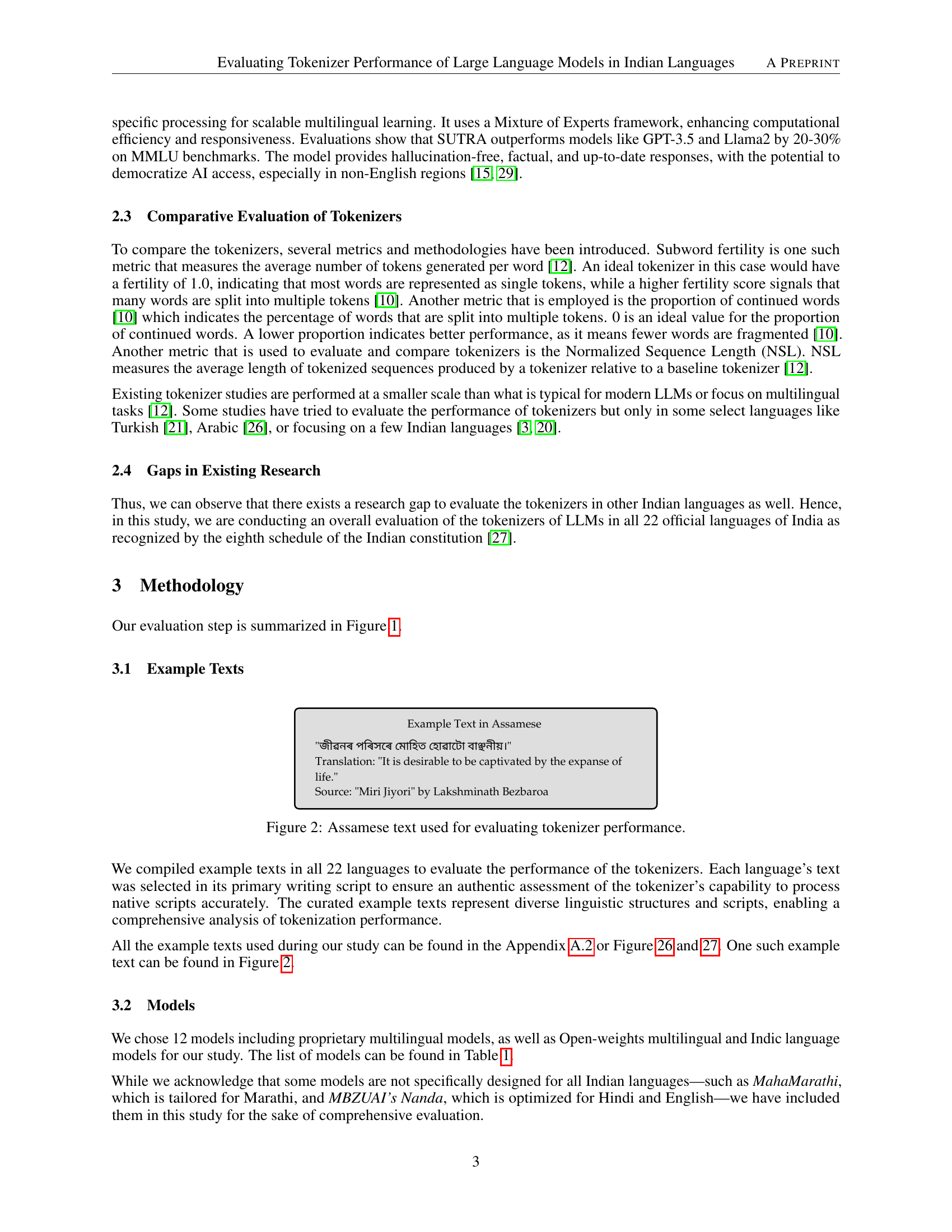

🔼 This table lists the twelve large language models (LLMs) whose tokenizers were evaluated in the study. For each LLM, it indicates whether the tokenizer was tested on all 22 official Indian languages (as per the Indian Constitution’s Eighth Schedule) and specifies the availability of the model (proprietary or open-source). The 22 languages are: Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu.

read the caption

Table 1: List of tokenizers tested. “All' refers to all 22 official languages of India as recognized by the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. The official languages include Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu.

In-depth insights#

Indic LLM Tokenizers#

The effectiveness of Indic language processing hinges significantly on the quality of tokenization employed by Large Language Models (LLMs). A dedicated exploration of ‘Indic LLM Tokenizers’ would reveal crucial insights into how these models handle the complexities of Indic scripts and morphology. Key areas of investigation would include a comparison of different tokenization algorithms (WordPiece, BPE, etc.) and their performance across various Indic languages. This would encompass an analysis of subword tokenization strategies, handling of rare words, and the impact of different vocabulary sizes. Furthermore, the research should address the issue of cross-lingual transferability: how well tokenizers trained on one Indic language generalize to others. Another critical aspect would be the evaluation metrics used to assess tokenizer performance (e.g., normalized sequence length, subword fertility, and perplexity). Finally, a discussion on the practical implications for LLM development and deployment, including computational efficiency and resource requirements, would be essential. The findings would guide future improvements in tokenizer design for better performance and more effective multilingual LLM development.

NSL Evaluation Metric#

The Normalized Sequence Length (NSL) evaluation metric offers a robust method for comparing the efficiency of various tokenizers across different languages, particularly valuable in the context of multilingual models. NSL directly addresses the core issue of tokenization efficiency by comparing the average length of tokenized sequences produced by different tokenizers against a baseline. This relative comparison mitigates the inherent variability in text length and complexity across languages, allowing for a more nuanced and fair assessment of tokenizer performance. The choice of a baseline tokenizer is crucial for establishing a meaningful comparison, as the NSL is relative to this baseline. A carefully chosen baseline should reflect a generally accepted standard in the field or a commonly used tokenizer for a particular language group. The utility of the NSL metric is especially apparent when assessing multilingual models, such as those handling the diverse range of Indian languages, because it allows for a clear understanding of how well different tokenizers handle different languages’ linguistic nuances. By quantifying the efficiency of tokenization, the NSL provides direct insight into computational resource requirements, speed of processing, and ultimately, the overall performance of the LLM. Further research could investigate optimal baseline selection methodologies for various language families to ensure robustness and consistency across a wide range of linguistic contexts.

SUTRA’s Superiority#

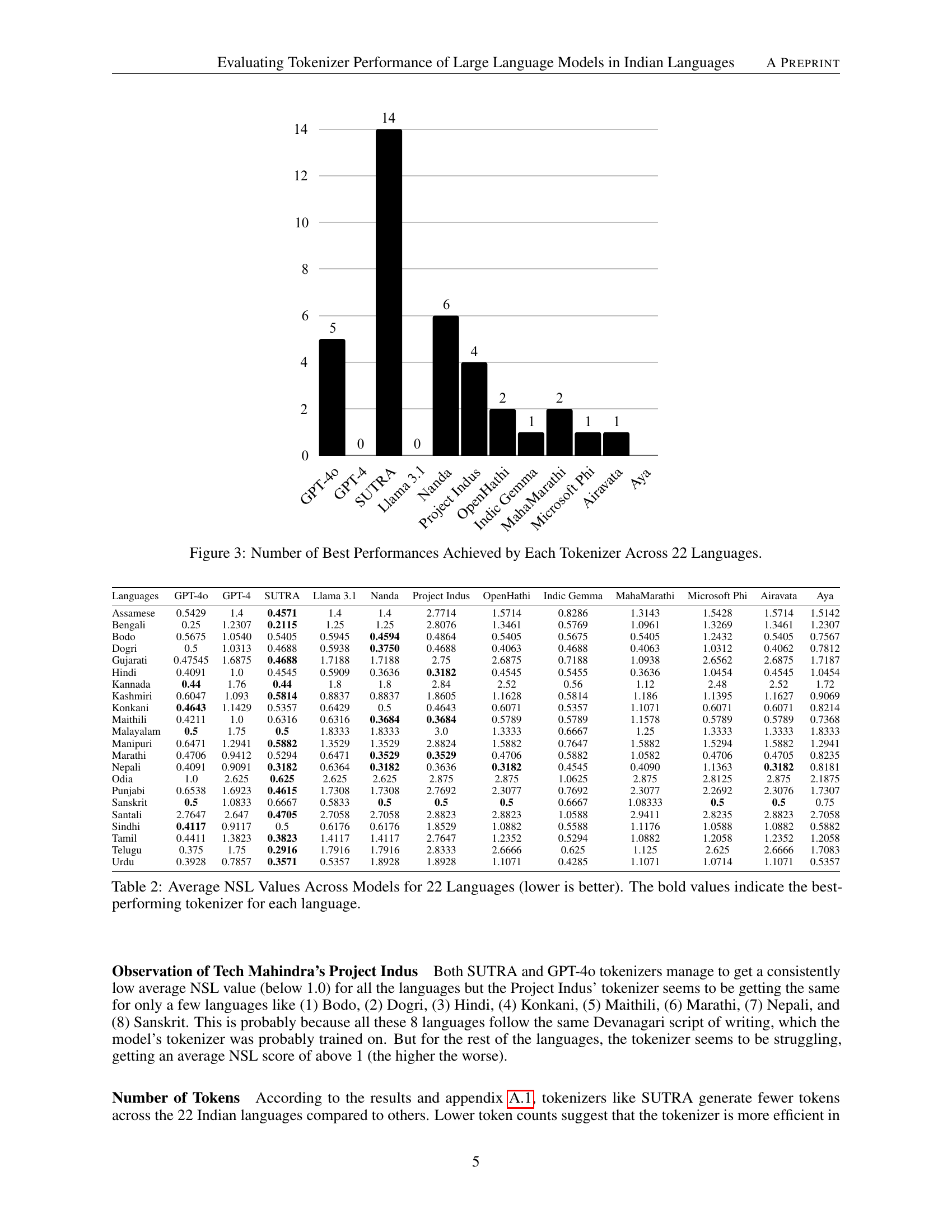

The research highlights SUTRA’s remarkable performance in tokenizing Indic languages, surpassing other LLMs, including those specifically designed for Indic languages or those with extensive multilingual capabilities. This superiority is evidenced by SUTRA achieving the lowest Normalized Sequence Length (NSL) scores across 14 out of 22 official Indian languages tested. This suggests SUTRA’s tokenizer is more efficient, generating fewer tokens on average and thus potentially leading to faster processing times and reduced computational costs. The study indicates that SUTRA’s success may be attributed to its advanced architecture and targeted strategies for handling the complexities of Indic scripts. However, further investigation is needed to pinpoint the precise reasons behind this superior performance and to explore the potential transferability of its methodologies to other language families.

GPT-4 vs GPT-40#

The comparison between GPT-4 and GPT-40 reveals a significant leap in performance, particularly concerning the handling of Indic languages. While GPT-4 showed limited success, GPT-40 demonstrates a clear advantage, achieving the best NSL scores in several languages. This suggests substantial improvements in the model’s multilingual capabilities, likely due to refinements in training data and/or architectural changes within the model. The superior performance of GPT-40 highlights the rapid evolution in large language models and the importance of ongoing development to address linguistic diversity. Further research focusing on the specific enhancements within GPT-40’s architecture would provide valuable insights into optimizing multilingual language models and effective tokenizer design. The stark contrast between the two versions underscores the need for continuous evaluation and improvement of LLMs to handle the complexities of diverse language families and the varying characteristics within them.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize expanding the scope of languages evaluated beyond the 22 official Indian languages, encompassing a wider range of dialects and low-resource languages. Investigating alternative tokenization methods, including those specifically designed for morphologically rich languages like many Indian languages, could significantly improve the efficiency and accuracy of tokenization. A key area needing attention is developing benchmark datasets that are more representative of the linguistic diversity within India. This will allow for a more nuanced evaluation of the tokenizer performance, and more importantly the impact of tokenization choices on downstream LLM tasks. Finally, exploring cross-lingual transfer learning techniques to leverage resources from high-resource languages to improve tokenization for low-resource languages would greatly enhance multilingual LLM development. This could potentially involve innovative approaches for leveraging shared linguistic features across language families.

More visual insights#

More on figures

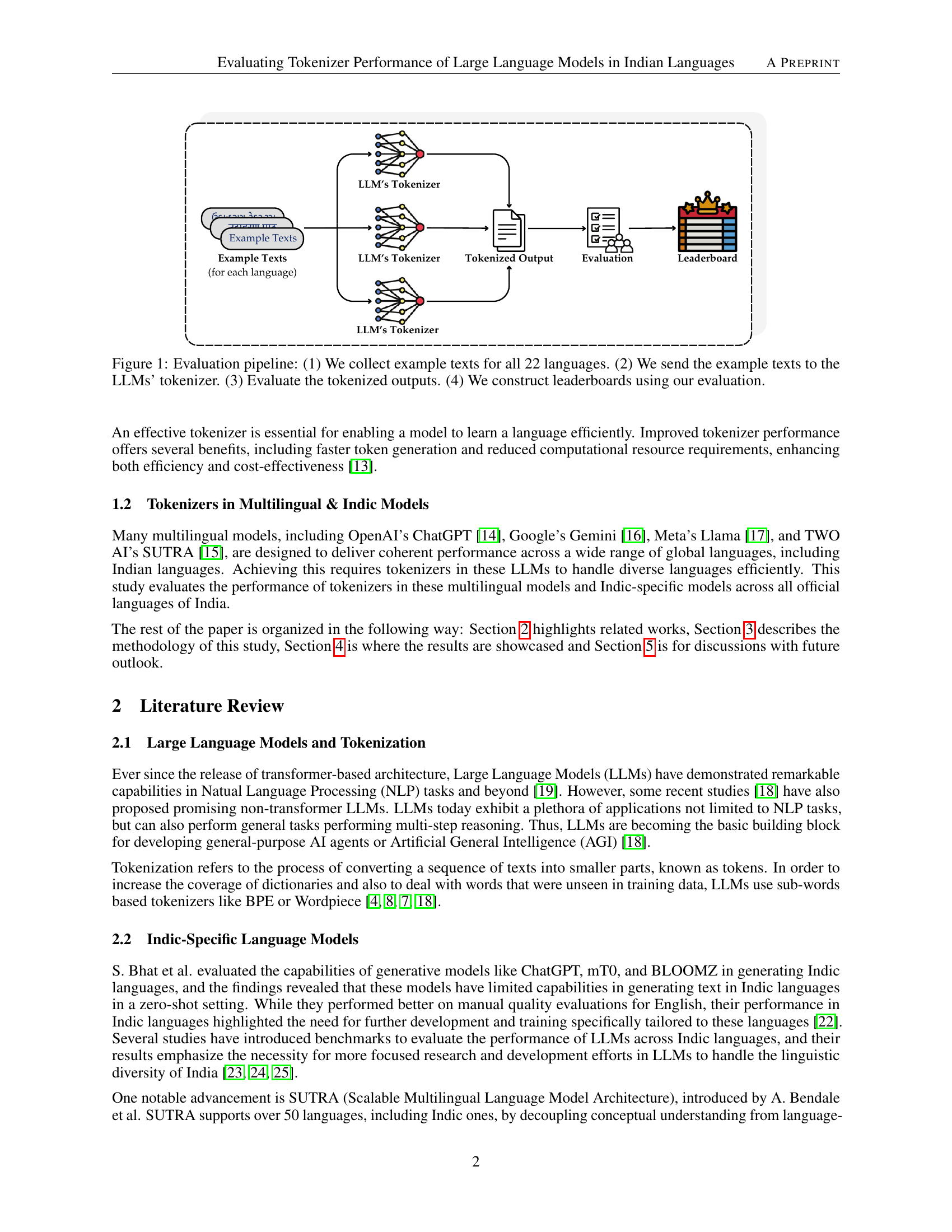

🔼 This figure shows an example of Assamese text used in the study to evaluate the performance of different tokenizers. The text is shown in the Assamese script and its English translation is provided for context. This example, along with similar examples in other Indian languages, is used to assess how effectively various language models’ tokenizers handle the complexities of different Indic scripts and linguistic structures.

read the caption

Figure 2: Assamese text used for evaluating tokenizer performance.

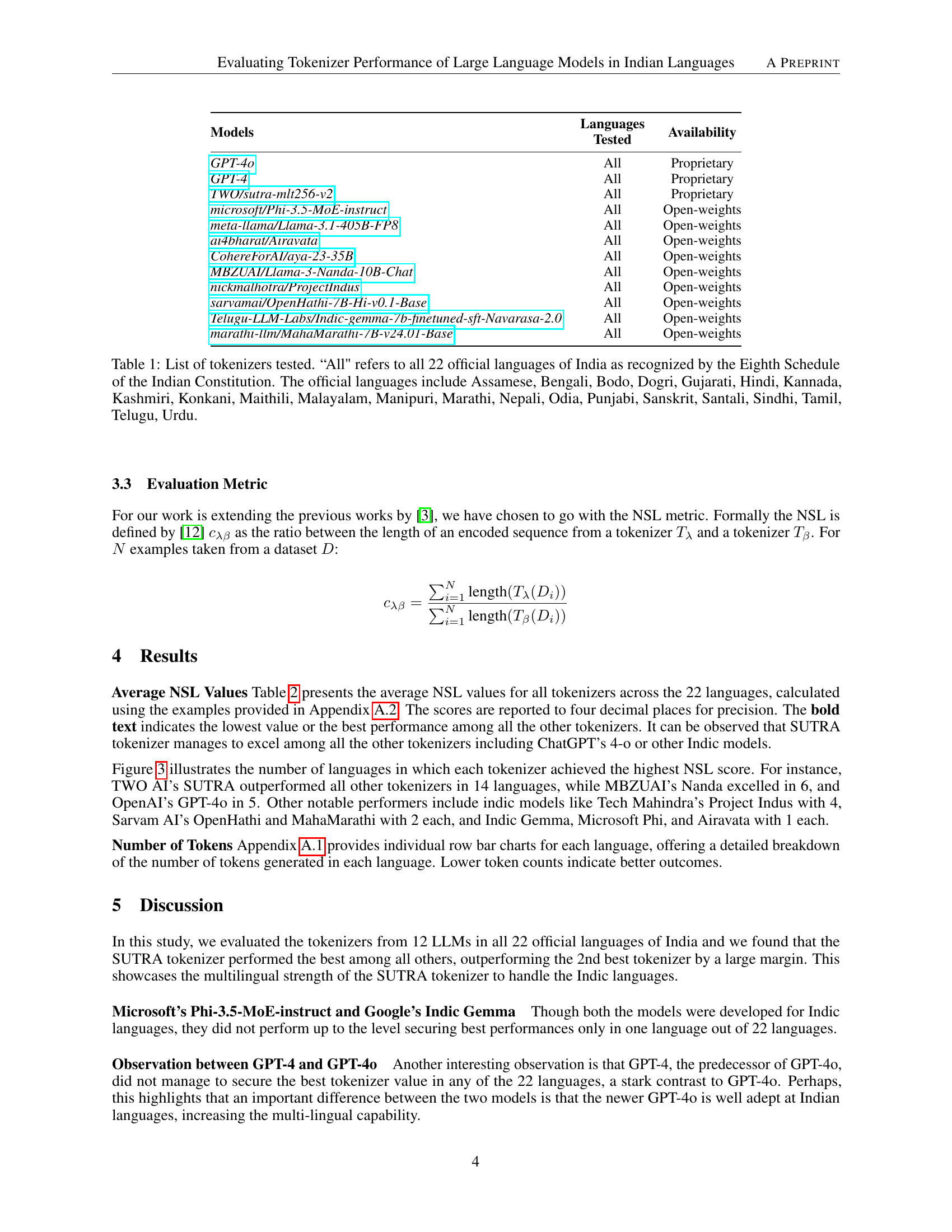

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the count of languages for which each tokenizer achieved the best performance, as measured by the Normalized Sequence Length (NSL) metric. The chart displays the superiority of the SUTRA tokenizer, which exhibits the best NSL score in 14 out of 22 Indian languages. It also highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of other tokenizers across the tested languages, illustrating the varying performance levels of different models in processing Indic language text.

read the caption

Figure 3: Number of Best Performances Achieved by Each Tokenizer Across 22 Languages.

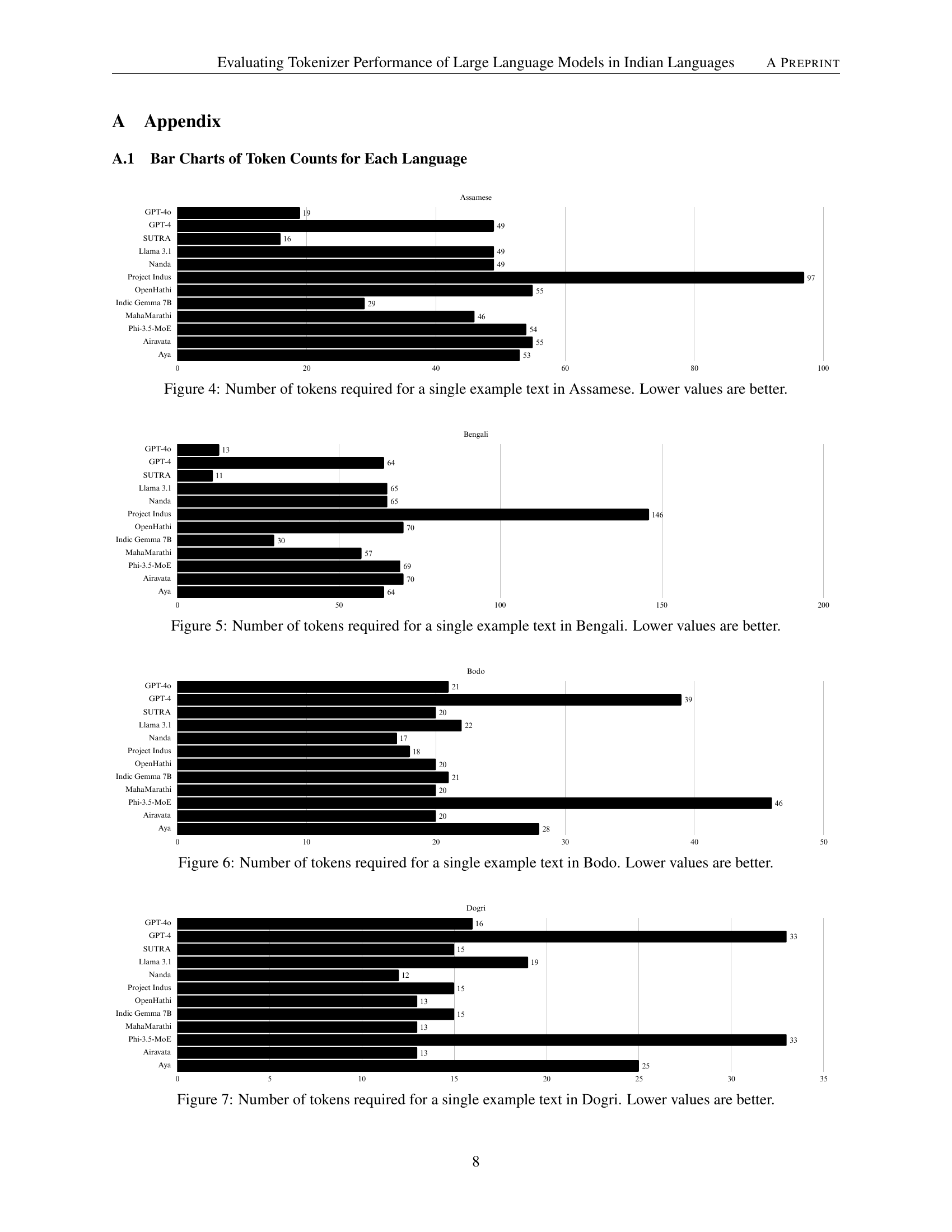

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by 12 different large language models (LLMs) for a single example sentence in the Assamese language. Each bar represents a different LLM’s tokenizer, showing the total token count produced. A lower number of tokens is generally preferable as it indicates greater efficiency in processing the text. The chart helps visualize and compare the performance of various LLMs’ tokenizers in handling Assamese text.

read the caption

Figure 4: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Assamese. Lower values are better.

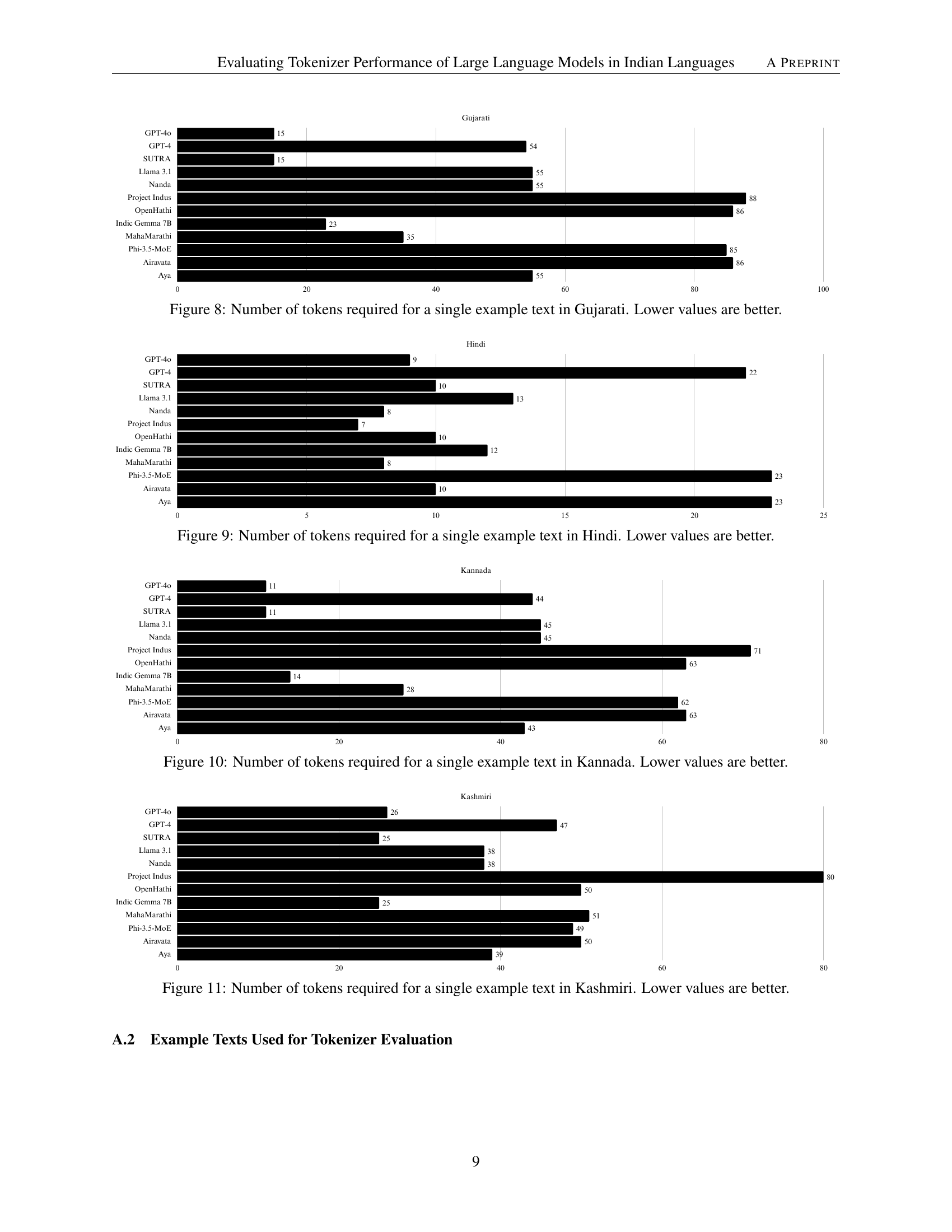

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by 12 different large language models (LLMs) when tokenizing a single example sentence in Bengali. Each bar represents a specific LLM’s tokenizer, showing the token count for that model. The chart helps compare the efficiency of different tokenizers, where lower token counts indicate better performance because more concise tokenization is generally more efficient.

read the caption

Figure 5: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Bengali. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language models (LLMs) for a single example sentence in the Bodo language. Each bar represents an LLM, and the height of the bar indicates the number of tokens produced. Lower values are preferable because fewer tokens generally signify more efficient processing and a better understanding of the language by the model’s tokenizer. The chart allows for a comparison of tokenization efficiency among the different LLMs for the Bodo language.

read the caption

Figure 6: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Bodo. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language models (LLMs) for a single example sentence in the Dogri language. Each bar represents an LLM, and the bar’s height corresponds to the token count. The models are: GPT-40, GPT-4, SUTRA, Llama 3.1, Nanda, Project Indus, OpenHathi, Indic Gemma 7B, MahaMarathi, Phi-3.5-MoE, Airavata, and Aya. Lower values are generally preferred as they indicate a more efficient use of tokens and computational resources.

read the caption

Figure 7: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Dogri. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by 12 different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single Gujarati text example. Each bar represents a tokenizer, and its height corresponds to the token count. Lower values are generally preferred, indicating more efficient tokenization (fewer tokens needed to represent the same text). The chart helps compare the efficiency of various tokenizers in handling Gujarati text.

read the caption

Figure 8: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Gujarati. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by 12 different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in Hindi. Each bar represents a tokenizer, and the bar’s height corresponds to the token count. Lower values indicate that the tokenizer is more efficient, as it breaks the sentence into fewer parts to process. The goal is to identify which tokenizer is most efficient for Hindi text.

read the caption

Figure 9: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Hindi. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language models (LLMs) for a single example sentence in the Kannada language. Each bar represents an LLM’s tokenizer, showing the token count. Lower values indicate better performance, as a more efficient tokenizer produces fewer tokens while maintaining meaning. The comparison allows for analysis of tokenization efficiency across various models.

read the caption

Figure 10: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Kannada. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by 12 different language models (LLMs) for a single example sentence in the Kashmiri language. Each bar represents an LLM’s tokenizer, showing the quantity of tokens produced. The chart allows for a comparison of the tokenization efficiency across various models. Shorter bars indicate superior performance, reflecting a more concise and effective tokenization process, which is generally desirable.

read the caption

Figure 11: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Kashmiri. Lower values are better.

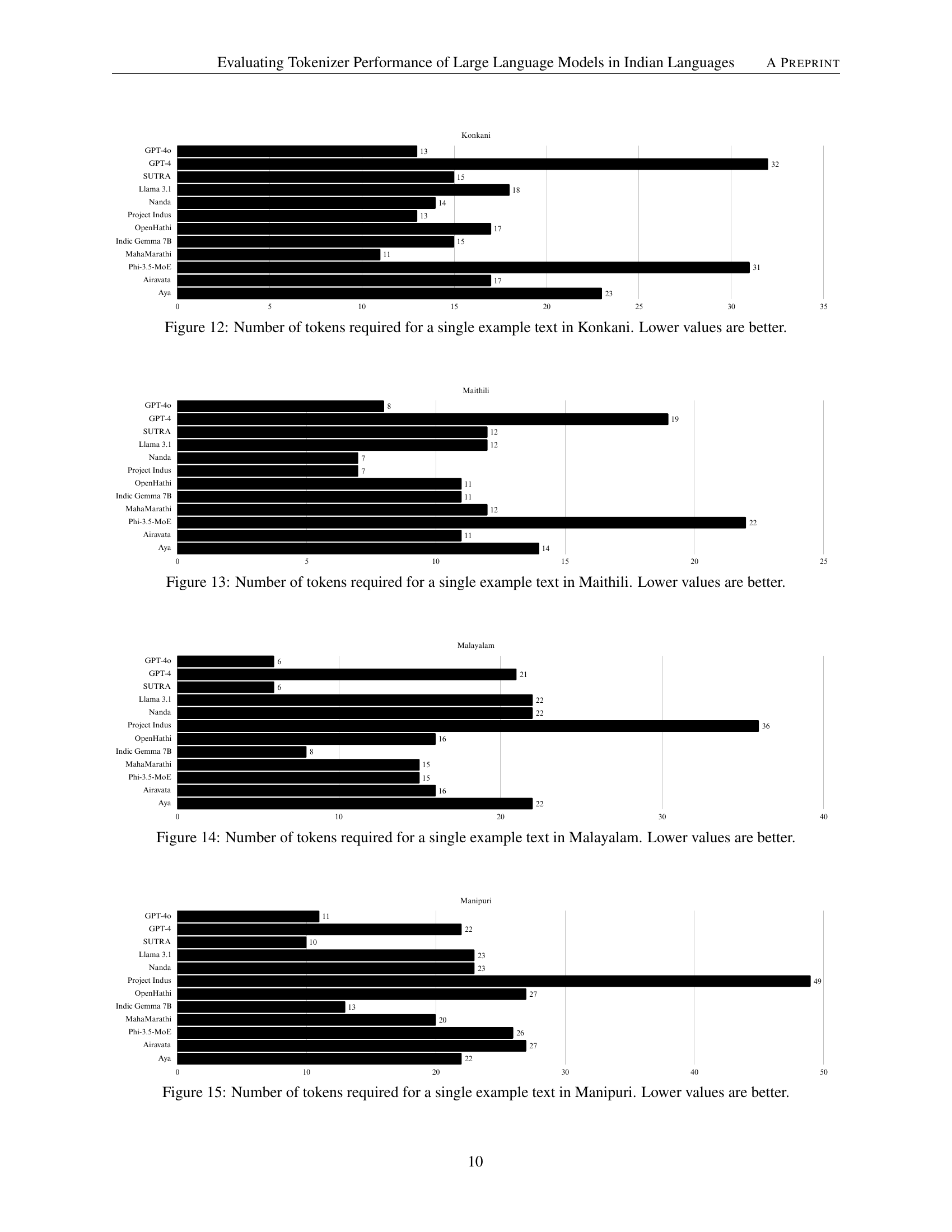

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language model (LLM) tokenizers for a single Konkani text example. Each bar represents a specific LLM tokenizer, showing the token count it produced. Shorter bars indicate more efficient tokenization, as fewer tokens mean less computational overhead for the LLM during processing. The chart allows for a comparison of tokenizer efficiency across different LLMs, highlighting which models produce the most concise token representations for Konkani text.

read the caption

Figure 12: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Konkani. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by 12 different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in the Maithili language. Each bar represents a tokenizer, and its height corresponds to the token count produced. A lower bar indicates that the tokenizer produced fewer tokens, which is generally preferred as it often implies better efficiency and potentially better model performance. The chart aids in comparing the efficiency of various LLMs’ tokenizers in processing Maithili text.

read the caption

Figure 13: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Maithili. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by 12 different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in the Malayalam language. Each bar represents a tokenizer, showing the token count produced. The chart facilitates a comparison of the efficiency of various tokenizers in handling Malayalam text. Lower values indicate more efficient tokenization, requiring fewer computational resources.

read the caption

Figure 14: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Malayalam. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by twelve different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in the Manipuri language. Each bar represents a tokenizer, and its height corresponds to the token count. The chart highlights the efficiency of different tokenizers, with shorter bars indicating better performance (fewer tokens needed to represent the same text). Lower token counts are generally preferable because they result in faster processing and lower computational resource consumption.

read the caption

Figure 15: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Manipuri. Lower values are better.

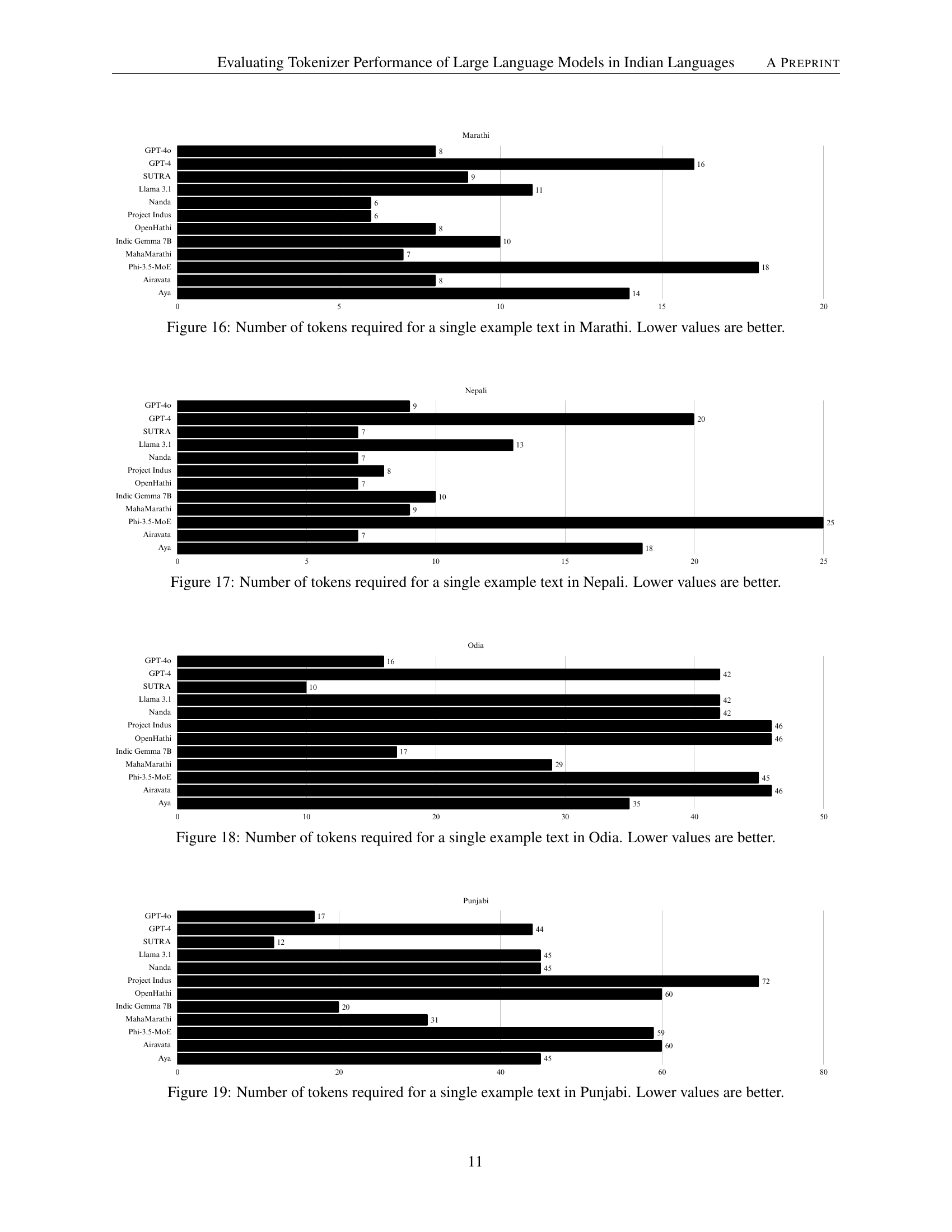

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by 12 different language models’ tokenizers for a single sample sentence in Marathi. Each bar represents a model (GPT-40, GPT-4, SUTRA, Llama 3.1, Nanda, Project Indus, OpenHathi, Indic Gemma, MahaMarathi, Phi-3.5-MoE, Airavata, and Aya), showing the token count produced by each model’s tokenizer. The length of the bar corresponds to the number of tokens; shorter bars indicate more efficient tokenization (fewer tokens generated for the same input). The chart helps compare the efficiency of different tokenizers for Marathi.

read the caption

Figure 16: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Marathi. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by twelve different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in Nepali. Each bar represents a specific tokenizer, and its height corresponds to the token count. Lower values indicate more efficient tokenization, as fewer tokens generally imply less computational cost and improved model performance. The chart allows for a comparison of the efficiency of various tokenizers across different LLMs when processing Nepali text.

read the caption

Figure 17: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Nepali. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by 12 different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in the Odia language. Each bar represents a specific tokenizer, and the height of the bar corresponds to the token count. Lower values indicate that the tokenizer is more efficient, breaking the sentence into fewer tokens. This efficiency is important for model processing speed and resource usage. The chart allows for a comparison of the tokenization efficiency of various LLMs across different algorithms and architectures.

read the caption

Figure 18: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Odia. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by 12 different large language model (LLM) tokenizers for a single Punjabi sentence. Each bar represents a different LLM tokenizer, and the height of the bar indicates the number of tokens produced. Lower values are preferable, as they suggest a more efficient tokenizer that requires fewer computational resources for processing. The chart allows for a comparison of the tokenization efficiency across various LLMs in the context of the Punjabi language.

read the caption

Figure 19: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Punjabi. Lower values are better.

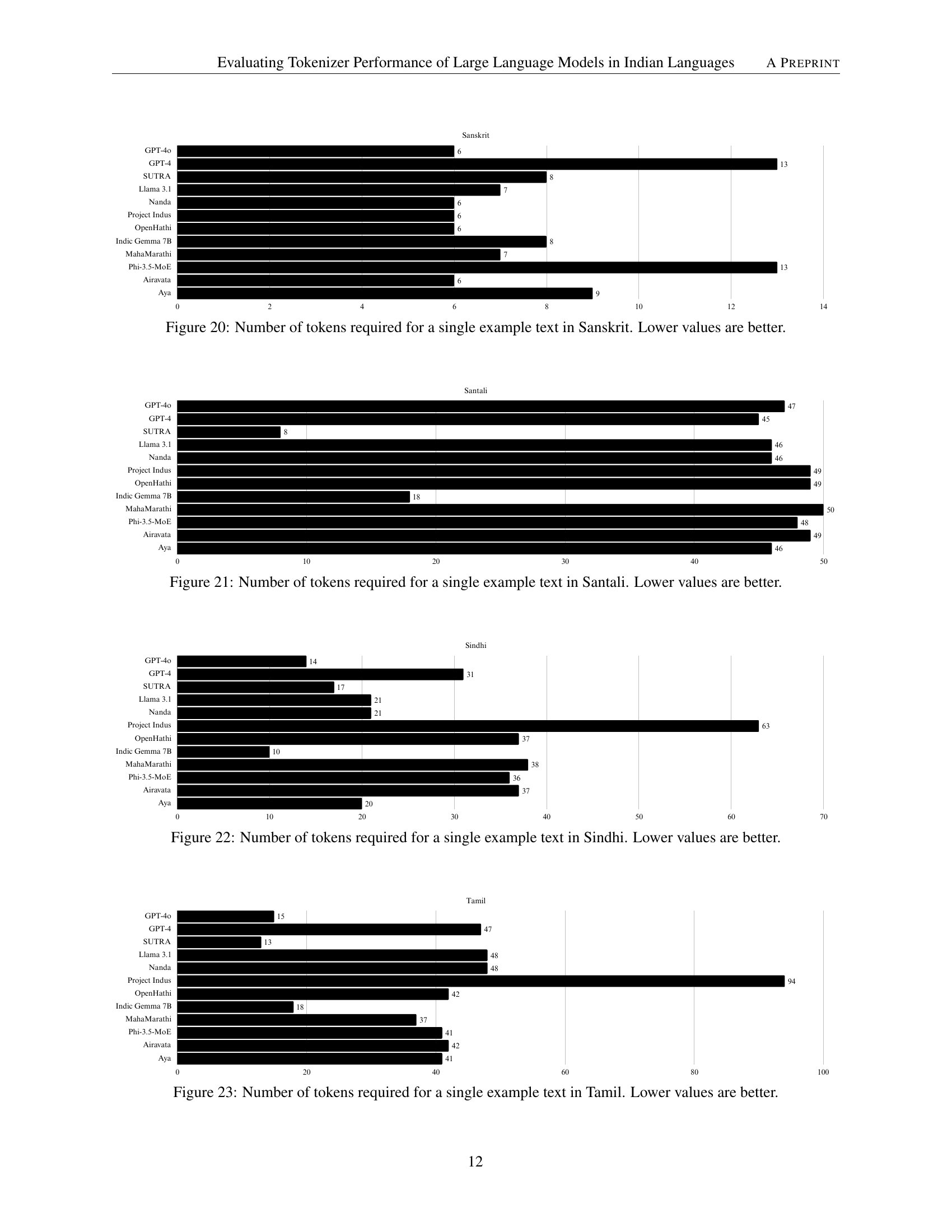

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in Sanskrit. Each bar represents a tokenizer, and the height of the bar corresponds to the token count. Lower values indicate better tokenizer performance, signifying greater efficiency and potentially reduced computational cost in processing the text.

read the caption

Figure 20: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Sanskrit. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by twelve different Large Language Model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in the Santali language. Each bar represents a different tokenizer, showing the token count. Lower values indicate more efficient tokenization, as fewer tokens generally mean less computational cost and faster processing. The comparison allows for an assessment of the relative performance of various tokenizers in handling Santali.

read the caption

Figure 21: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Santali. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language models (LLMs) for a single example sentence in Sindhi. Each bar represents a different LLM’s tokenizer, showing the token count produced. The chart helps to compare the efficiency of the tokenizers across different LLMs; lower values are preferable, indicating a more efficient and concise tokenization.

read the caption

Figure 22: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Sindhi. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart visualizes the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in the Tamil language. Each bar represents a specific LLM tokenizer, showing the token count. Shorter bars indicate more efficient tokenization, as fewer tokens generally mean better performance and reduced computational costs. The chart allows for a comparison of the tokenization efficiency of various LLMs when processing Tamil text. The goal is to identify which tokenizers are most efficient for the Tamil language.

read the caption

Figure 23: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Tamil. Lower values are better.

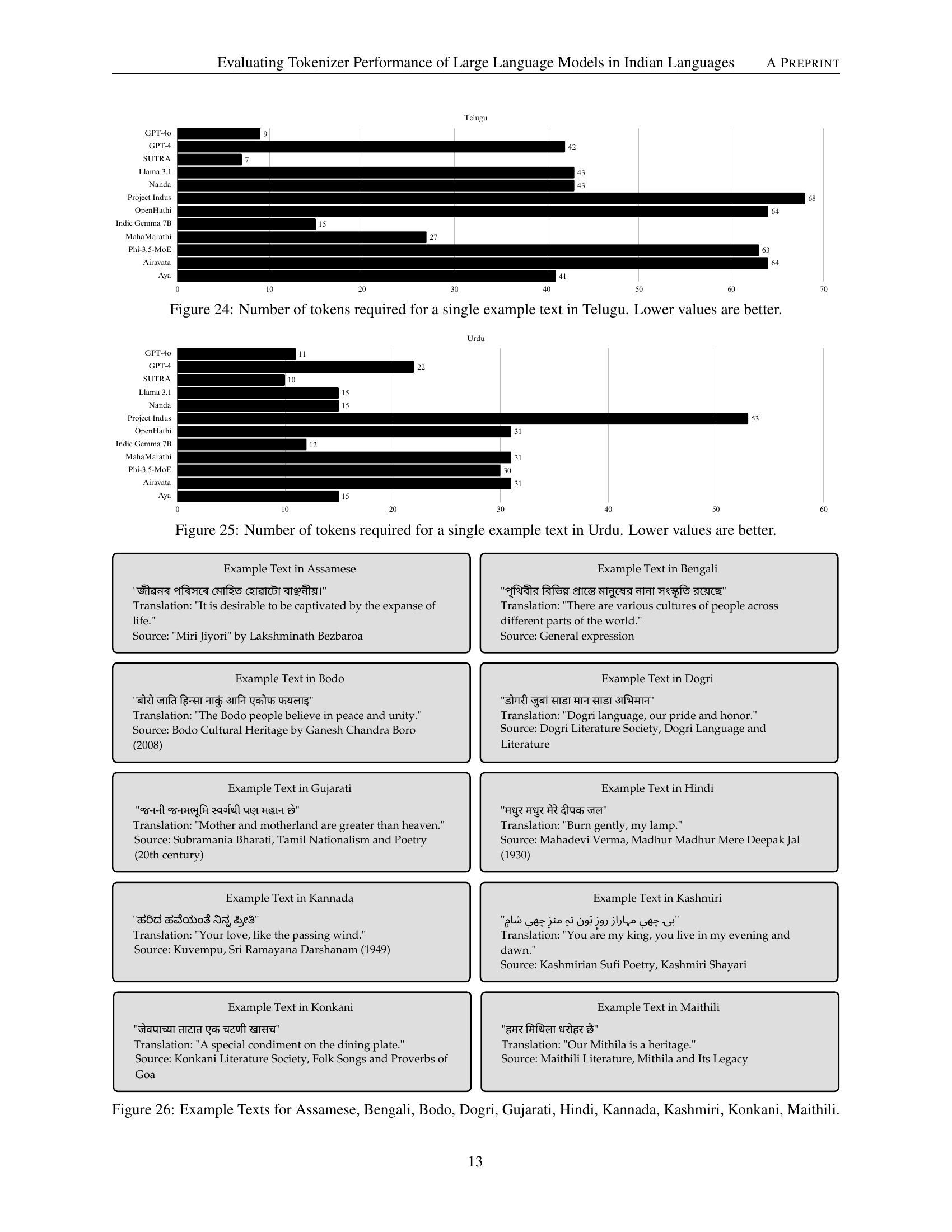

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by twelve different large language model (LLM) tokenizers for a single example sentence in Telugu. Each bar represents a tokenizer, and its height corresponds to the token count. Lower token counts are preferred, as they indicate more efficient tokenization and potentially better LLM performance. The chart allows for a comparison of the efficiency of various tokenizers, highlighting which models produce the fewest tokens for the same input, suggesting better performance.

read the caption

Figure 24: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Telugu. Lower values are better.

🔼 This bar chart displays the number of tokens generated by 12 different large language model (LLM) tokenizers for a single Urdu sentence. Each bar represents a tokenizer, and the bar’s height corresponds to the token count. A shorter bar indicates that the tokenizer produced fewer tokens, which is generally more efficient and desirable. The chart allows for a comparison of tokenizer efficiency across various LLMs in processing Urdu text.

read the caption

Figure 25: Number of tokens required for a single example text in Urdu. Lower values are better.

🔼 Figure 26 shows example texts used in the study for evaluating tokenizer performance. It provides sample sentences in ten of the twenty-two official Indian languages evaluated: Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, and Maithili. Each example is presented with its translation in English, along with the source of the text, such as a literary work or a well-known saying.

read the caption

Figure 26: Example Texts for Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithili.

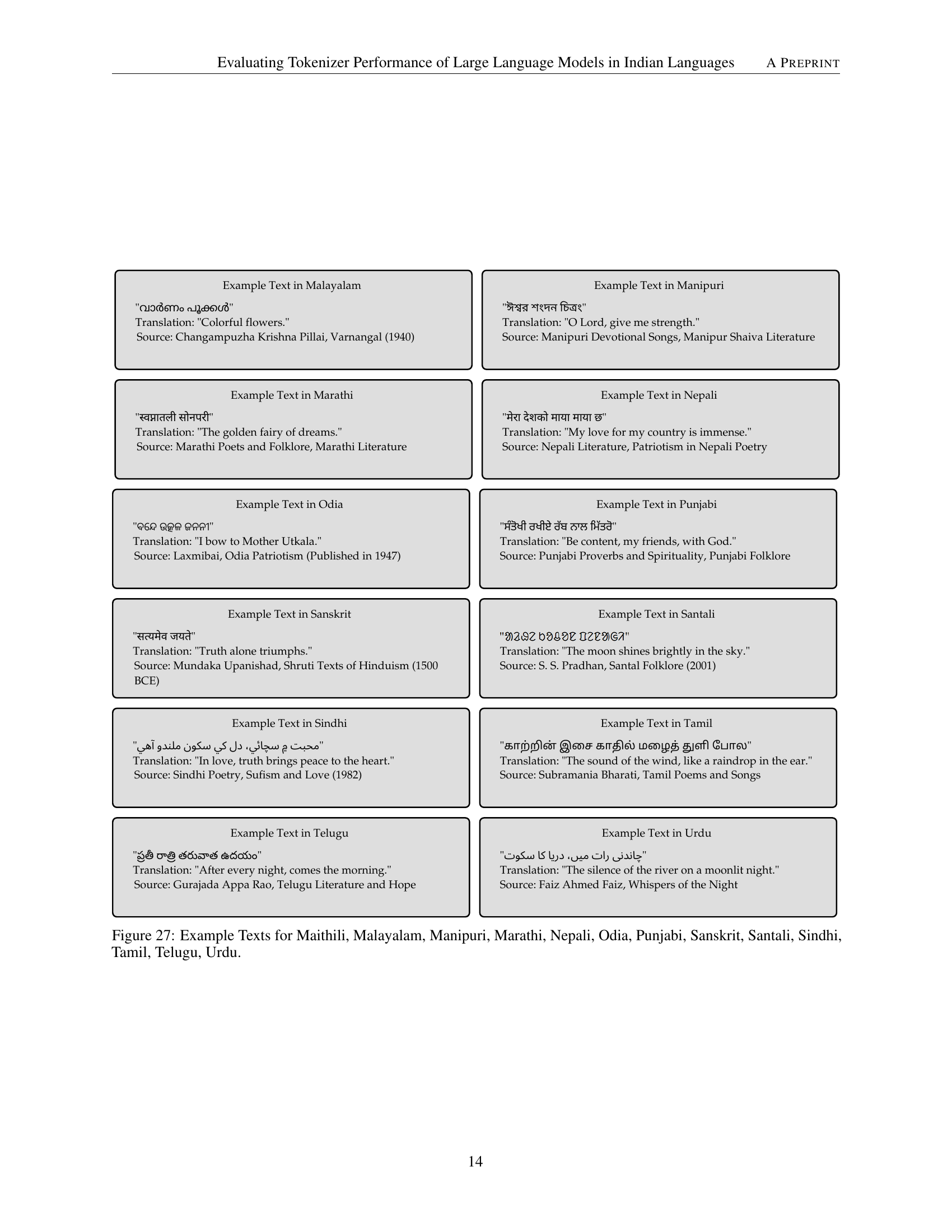

🔼 Figure 27 shows example texts used for evaluating the tokenizers’ performance in 13 Indian languages: Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu. Each example sentence is provided with its translation in English to aid comprehension and to illustrate the diversity of scripts and sentence structures among these languages.

read the caption

Figure 27: Example Texts for Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu.

Full paper#