TL;DR#

Soft robots excel in safe, compliant interactions but struggle with high-speed dynamic tasks like in-hand manipulation. Existing methods often rely on precise object models and simulations, limiting real-world applicability. The challenge is amplified with soft robots because of their compliance and the inherent difficulty in precisely modeling their behavior. Many prior works focused on slow, quasi-static tasks.

This paper introduces SWIFT, a system that learns to dynamically spin a pen using a soft robotic hand. Instead of relying on simulations or precise object models, SWIFT uses real-world trial-and-error learning. The system identifies optimal grasping and spinning parameters enabling the soft hand to successfully spin the pen robustly and reliably. This success was demonstrated across three pens with varied properties, proving the method’s adaptability. Furthermore, the approach generalized well to spinning other objects, showing versatility.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it demonstrates a novel approach to dynamic in-hand manipulation using soft robotics, a field currently facing challenges in achieving high-speed, precise control. The findings open new avenues for research in soft robotic dexterity, particularly in applications requiring safe and compliant interaction with dynamic environments.

Visual Insights#

🔼 The figure demonstrates the SWIFT system performing dynamic in-hand pen spinning. A soft robotic hand, specifically a soft multi-finger gripper, initially grasps a pen. A learned action sequence then causes the robot to rapidly rotate the pen around one of its fingers before skillfully catching it. This showcases the system’s ability to handle high-speed, partially non-prehensile manipulation tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: SWIFT tackles the problem of high-speed dynamic in-hand partially non-prehensile manipulation with soft robotic hands. Using a soft multi-finger gripper, the robot grasps a pen. Then, using a learned action sequence, rapidly rotates the pen around a finger and catches it.

| Action Parameterization | Parameters | Object | Successes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization | ∅ | pen 1 | 0 / 10 |

| pen 2 | 0 / 10 | ||

| pen 3 | 0 / 10 | ||

| No grasp optimization | (s,d) | pen 1 | 0 / 10 |

| pen 2 | 7 / 10 | ||

| pen 3 | 0 / 10 | ||

| Optimal action from Pen 1 | (s,d,g) | pen 1 | 10 / 10 |

| pen 2 | 0 / 10 | ||

| pen 3 | 7 / 10 | ||

| Full optimization (proposed) | (s,d,g) | pen 1 | 10 / 10 |

| pen 2 | 10 / 10 | ||

| pen 3 | 10 / 10 | ||

| brush | 10 / 10 | ||

| screwdriver | 5 / 10 |

🔼 This table presents the success rates of pen spinning achieved by the SWIFT system using different action parameterizations. It compares the performance when only spinning parameters are optimized, when both spinning and grasping parameters are optimized, and when the optimal parameters found for one pen are applied to others. The results show that optimizing both grasping and spinning parameters leads to the best performance and generalizes well to pens with varying weight distributions and even to non-pen-shaped objects like brushes and screwdrivers.

read the caption

TABLE I: Action parameterization success rate We optimized various action parameterizations using 10 generations of SWIFT. The results suggest that optimizing both grasp location and spinning parameters yields the best performance, with generalization demonstrated on non-pen objects with varying geometries and mass distributions.

In-depth insights#

Soft Robotics Dexterity#

Soft robotics, with its inherent compliance and adaptability, presents a unique opportunity to advance dexterity in robotic manipulation. While traditional rigid robots excel in precise, repeatable movements, soft robots offer advantages in safe interaction with unpredictable environments and delicate objects. The inherent softness allows for robust grasping and manipulation even with imperfect object models or uncertain positioning. However, achieving high-speed dynamic tasks remains a challenge due to the complex mechanical properties and the difficulty in precise control of soft actuators. Research in this area focuses on developing effective control strategies, leveraging the dynamics of soft materials, and employing learning-based approaches to overcome the limitations. The integration of advanced sensors and sophisticated control algorithms is crucial for enabling dexterous manipulation. Ultimately, the promise of soft robotics lies in its potential to create robots capable of performing complex, human-like tasks in unstructured settings, which will require continued advances in material science, actuation techniques, and control methodologies.

SWIFT: Dynamic Learning#

The concept of “SWIFT: Dynamic Learning” suggests a system that learns dynamic manipulation skills in real-time, rather than relying on pre-programmed actions or extensive simulations. This approach is particularly valuable for soft robots, which are known for their adaptability and safety but often struggle with high-speed dynamic tasks. SWIFT likely utilizes a trial-and-error learning process, allowing the robot to repeatedly attempt a task (like pen spinning) and adjust its actions based on real-world feedback from sensors and cameras. This method requires sophisticated state estimation to track the object’s position and orientation. Successful implementation would likely involve an efficient optimization algorithm, such as CMA-ES, to navigate the high-dimensional space of possible actions, rapidly converging on successful strategies. The system’s robustness would be demonstrated by its ability to generalize across objects with different physical properties, showing a true learning capability rather than mere parameter tuning.

Real-World Trial-Error#

The concept of ‘Real-World Trial-and-Error’ in robotics research signifies a paradigm shift from simulation-heavy approaches. Directly learning in the real world allows robots to adapt to the inherent complexities and uncertainties of unstructured environments, bypassing the limitations of idealized simulations. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with soft robots, whose dynamic interactions with the environment are difficult to accurately model. Trial-and-error, guided by a well-defined reward function and efficient optimization strategies, enables the robot to discover optimal control policies through repeated attempts. The success of this method relies on the robot’s ability to safely interact with its environment, emphasizing the importance of robust design and safety mechanisms in soft robotics. The resulting policies are likely to be more robust and generalizable than those obtained solely through simulation, making this approach crucial for developing truly adaptable and practical soft robotic systems.

Generalization Limits#

The success of SWIFT in learning dynamic in-hand pen spinning raises the question of its generalization limits. While SWIFT demonstrated robustness across pens with varying weights and weight distributions, its performance on non-cylindrical objects like a brush and screwdriver was less consistent. This suggests that the learned policy, while adept at manipulating cylindrical objects, may not readily generalize to objects with significantly different shapes and mass distributions. Further investigation is needed to determine the extent to which the learned primitives are transferable to other dynamic manipulation tasks. For example, objects with complex shapes, textures, and compliance properties will present novel challenges not addressed in this study. The reliance on a relatively simple reward function could also be a limitation. A more nuanced reward function that incorporates factors beyond success/failure might facilitate learning more robust and generalizable policies. Finally, the use of a soft hand, while advantageous in terms of safety and compliance, introduces complexities in modeling and control that could limit generalization. Future work should focus on expanding the dataset to encompass a broader range of objects and situations to more thoroughly evaluate the robustness and adaptability of the learned controller, and to identify clear boundaries for its effective operation.

Future: Soft Dynamics#

The future of soft robotics hinges on addressing the limitations of current soft actuators and control systems to fully exploit dynamic manipulation capabilities. Future research must focus on developing more sophisticated models that accurately capture the complex, highly nonlinear behaviors of soft materials, including hysteresis and creep, enabling more precise and predictable control. Advances in sensing technologies are crucial, providing real-time feedback of the soft robot’s interaction with the environment. This is vital for achieving robust and reliable performance in dynamic tasks. Improving the speed and accuracy of soft actuators is also critical, bridging the gap between the compliant nature of soft robots and the demands of high-speed manipulation. Developing novel control algorithms tailored to the unique properties of soft robots will enhance their adaptability and dexterity. Integrating machine learning techniques for rapid adaptation and skill acquisition is another key area of exploration. Ultimately, a synergistic integration of advanced materials, sensors, actuators, and control systems is necessary to unlock the full potential of soft robots in performing complex dynamic tasks. This holistic approach will pave the way for safe, adaptable, and efficient soft robots for various applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure shows a three-fingered soft robotic hand, a variant of the Multi-finger Omnidirectional End-effector (MOE). Each finger is composed of four tendons, controlled independently by two servo motors. Each motor’s actuation moves the finger in a perpendicular direction relative to the other motor’s actuation, providing flexibility and dexterity. The image displays both the unactuated and actuated states of the hand, highlighting how the tendons move the fingers. This setup is crucial for the pen-spinning experiments because of its compliant nature and ability to safely interact with the pen.

read the caption

Figure 2: Multi-finger Omnidirectional End-effector (MOE). The soft hand we used is a three-finger variant of the MOE. Each finger has four tendons actuated by two servo motors, each motor controlling the finger in perpendicular directions.

🔼 Figure 3 illustrates the pen-spinning process using a soft robotic hand. The process starts with the pen placed in a designated slot. The robot arm then grasps the pen, adjusting its position (parameter ‘g’) before initiating a spinning motion controlled by parameters ’s’. A specific finger (m1) holds the pen during spinning for a defined duration (’d’). Finally, the hand catches the pen, the arm returns to its starting position, releasing the pen, and the cycle begins again.

read the caption

Figure 3: Task progression over time. There are three main stages for each pen-spinning trajectory. We place the pen according to the blue slots fixed on the table, and the robot moves to grasp and move the pen to reach the pre-spin pose with g𝑔gitalic_g or pre-defined constant. The MOE fingers then execute s𝑠sitalic_s to attempt to spin the pen, and finger m1𝑚1m1italic_m 1 waits for d𝑑ditalic_d seconds before closing to catch the pen. Finally, the robot arm moves to the initial joint configuration, dropping the pen and restarting the cycle.

🔼 Figure 4 shows the experimental setup for the pen-spinning task. The top panel depicts a 3-finger MOE soft robotic hand attached to a 6-DOF robotic arm. This setup allows for safe and controlled interaction with the pen during the learning process. An RGB-D camera is integrated to capture visual and depth data, enabling real-time feedback and state estimation to evaluate the success of the actions performed. A box is strategically placed to catch the pen when dropped, which simplifies the reset process and allows for efficient repeated trials. The bottom panel provides detailed information of dimensions and physical properties of each object used in the experiments (pens, brush and screwdriver). This includes their length, radius, weight, and approximate center of mass.

read the caption

Figure 4: Our setup for pen spinning. Top: A 3-finger MOE soft robotic hand is attached to a 6 degree-of-freedom robot arm to develop a system that can safely interact with the pen and learn to spin it. An RGB-D camera is used to evaluate the performance of the sampled action based on the objective function. The box catches the pen when it is dropped to simplify resetting the system for the next trial. Bottom: the length, radius, weight, and approximate center of mass of each object used in the experiment

🔼 Figure 5 illustrates the SWIFT (Soft-hand With In-hand Fast re-orienTation) optimization pipeline. The process involves four main steps, repeated for each iteration (k): 1) The robotic arm positions the MOE (Multi-finger Omnidirectional End-effector) hand to grasp the pen at a specific location (gk), which may be optimized during the process. 2) The MOE hand is moved to a pre-spin position, and the parameterized action is executed by the hand’s fingers. 3) An RGB-D camera captures the action. SAM-v2 (Segment Anything v2) is used to segment the pen from the captured image, creating a point cloud that is then processed to determine the pen’s rotation and displacement. 4) Finally, the objective function is evaluated using the observed pen state, and the action parameters are updated via the CMA-ES (Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy) optimization algorithm.

read the caption

Figure 5: SWIFT optimization pipeline. There are 4 main stages for each iteration k𝑘kitalic_k: 1) During grasping and resetting, the robot arm moves the MOE hand to a target grasp location following a specific grasping location gksubscript𝑔𝑘g_{k}italic_g start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_k end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. 2) The robot arm then moves the MOE hand to the pre-spin configuration, where the MOE fingers execute the parameterized action. 3) An RGB-D camera records the trial, and we apply masks from SAM-v2 to create a segmented point cloud. We then apply other post-processing of the point cloud to get the rotation and displacement state of the pen. 4) Lastly, the pipeline evaluates the objective function with observed states of the pen and updates the action parameters with the optimization algorithm CMA-ES.

🔼 This figure shows a series of images visualizing the successful pen spinning results after the optimization process. Each row represents a different pen (Pen 1, Pen 2, Pen 3), with Pen 1 having a balanced weight distribution while Pens 2 and 3 are unbalanced. The images within each row capture the stages of the pen-spinning action, from initial grasp to successful final pose. A circle is overlaid in the initial frame on each pen to show the location of its center of mass.

read the caption

Figure 6: Spinning visualization after optimization. Top row: pen 1 with balanced weights. Middle row: pen 2 with unbalanced weight. Bottom row: pen 3 with unbalanced weight. The circle in the initial frame indicates the center of mass for the pen.

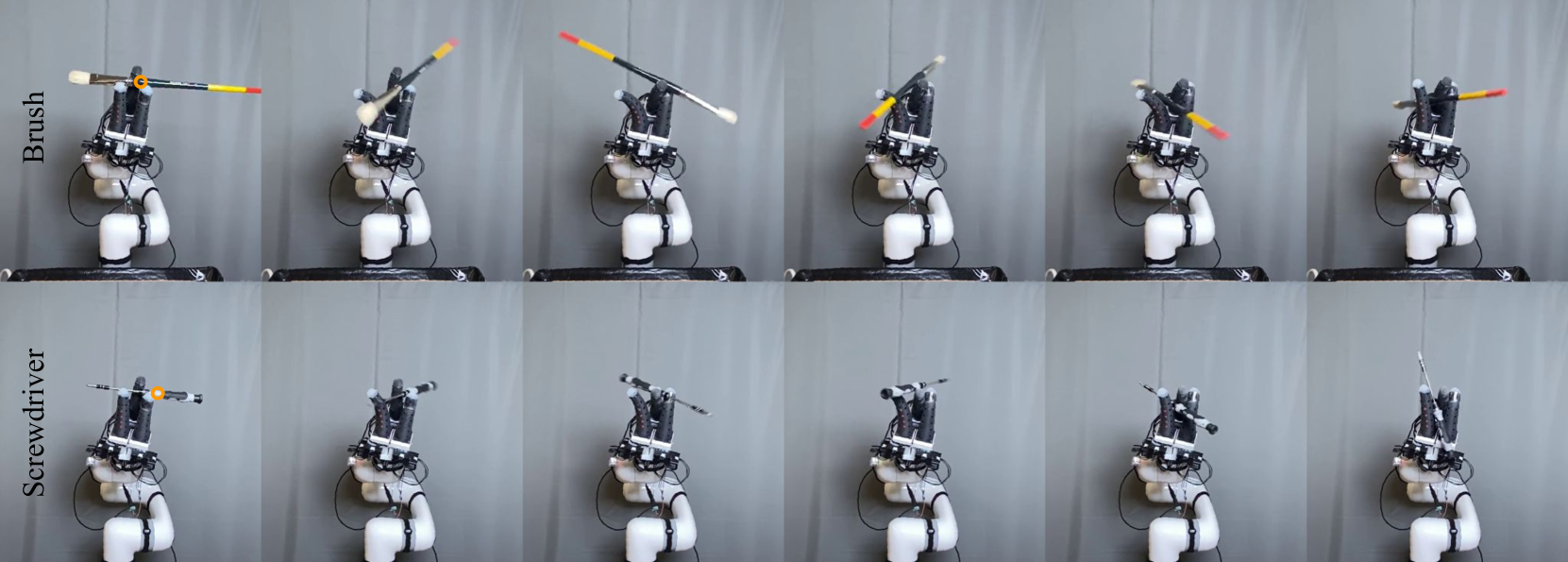

🔼 Figure 7 demonstrates the generalization capability of the SWIFT system. Instead of only spinning pens, the system was tested on objects with more complex shapes and mass distributions: a brush and a screwdriver. The images show the successful spinning of these objects, highlighting SWIFT’s adaptability. The circle in the initial frame of each sequence marks the approximated center of mass for each object.

read the caption

Figure 7: Generalization to other objects. We applied SWIFT to other objects with more irregular shapes, such as a brush or a screwdriver. The circle in the initial frame indicates the approximated center of masses.

Full paper#