↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current methods for generating videos for autonomous driving struggle with producing high-resolution and long videos while maintaining control over various parameters. This limits the ability to train and test autonomous driving models effectively using realistic and detailed synthetic data. Furthermore, incorporating control conditions into video generation models is challenging, affecting the quality and fidelity of synthetic data.

MagicDriveDiT tackles these challenges by leveraging a DiT-based architecture, enabling efficient handling of high-resolution and long videos. It uses flow matching for scalability and incorporates a progressive training strategy, starting with low-resolution short videos before gradually increasing resolution and length. The model employs a novel spatial-temporal conditional encoding mechanism, achieving precise control over the generated videos’ spatial-temporal latents. The results demonstrate significant improvements in generating high-quality, controllable street-view videos, exceeding the performance of existing methods. This innovative approach has significant potential for autonomous driving applications, enhancing model training, evaluation, and testing.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances high-resolution long video generation for autonomous driving, a crucial area for improving autonomous system safety and reliability. The novel approach using the DiT architecture and adaptive control mechanisms addresses key challenges in scalability and controllability, providing a valuable contribution to the field. The findings open up new avenues for research in video synthesis and autonomous driving perception, potentially leading to more realistic and efficient simulations and improved model training.

Visual Insights#

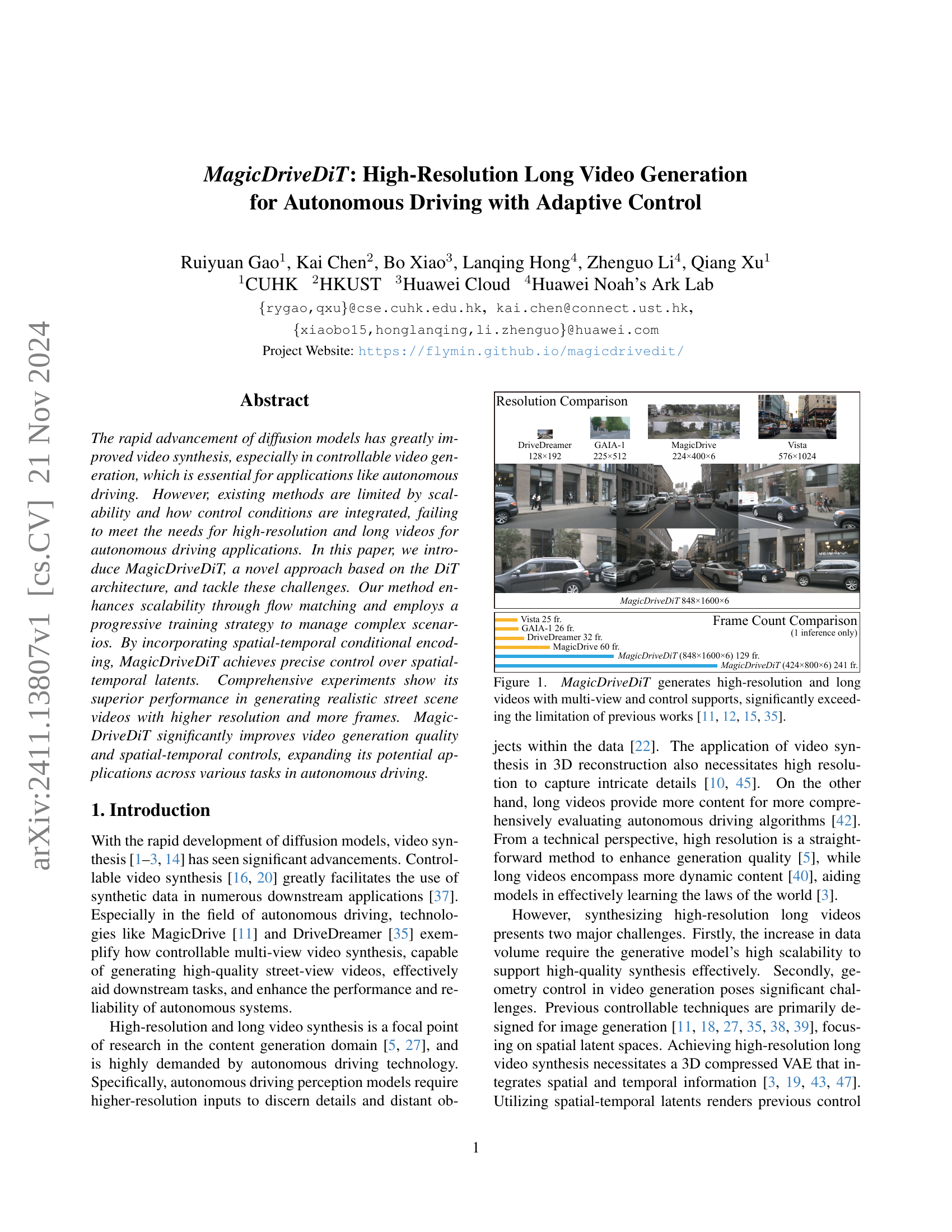

🔼 Figure 1 showcases the superior capabilities of MagicDriveDiT in generating high-resolution, extended-length videos compared to existing methods. It highlights MagicDriveDiT’s ability to produce videos with multiple viewpoints and offers precise control over the generated content. The resolution and frame count significantly surpass those achieved by previous techniques such as DriveDreamer, GAIA-1, Vista, and MagicDrive, demonstrating a substantial improvement in video synthesis for autonomous driving applications.

read the caption

Figure 1: MagicDriveDiT generates high-resolution and long videos with multi-view and control supports, significantly exceeding the limitation of previous works [35, 15, 11, 12].

| Type | Method | Total Res. | Frame |

|---|---|---|---|

| Front View | GAIA-1∗[15] | 288×512×1 | 26 |

| DriveDreamer [35] | 128×192×1 | 32 | |

| Vista∗[12] | 576×1024×1 | 25 | |

| Multi-view | MagicDrive [11] | 224×400×6 | 60 |

| Drive-WM [38] | 192×384×6 | 8 | |

| Panacea [39] | 256×512×6 | 8 | |

| DriveDreamer2 [46] | 256×448×6 | 8 | |

| Delphi [27] | 512×512×6 | 10 | |

| DiVE [18] | 480p×6 | 16 | |

| MagicDriveDiT | 848×1600×6 | †129 | |

| 424×800×6 | 241 |

🔼 This table compares the resolution and frame count of various methods for video generation in autonomous driving. It highlights the limitations of existing approaches in achieving both high resolution and long video sequences, demonstrating the superior capabilities of MagicDriveDiT. The asterisk (*) indicates methods that only support text and image condition inputs, and the dagger (†) refers to additional notes within the Appendix of the paper. Rollout inference is not considered because it significantly reduces the quality of the generated videos.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Resolution and Frame Count. We only consider a single inference, since rollout notably degrades quality. ∗Only support text & image(s) conditions. †See note in Appendix.

In-depth insights#

DiT for Video#

The application of Diffusion Transformer (DiT) architectures to video generation presents a compelling avenue for high-resolution and long-form video synthesis. DiT’s inherent scalability is crucial for handling the vast computational demands associated with high-resolution videos, outperforming traditional U-Net based architectures. The use of DiT in the MagicDriveDiT model allows for the generation of realistic street scenes, exceeding the capabilities of existing methods. Spatial-temporal conditional encoding, integrated with DiT, enables precise control over the generated video content by incorporating information from various sources such as camera trajectories, road maps, and 3D bounding boxes. However, challenges remain in effectively managing spatiotemporal latents for high-fidelity control, which is addressed in MagicDriveDiT through a progressive bootstrapping training strategy. This approach mitigates the computational complexities and improves model convergence, highlighting the effectiveness of iterative training for achieving high quality in video generation. Ultimately, the combination of DiT’s scalability and advanced control techniques offers a significant advancement in controllable video generation, particularly beneficial for applications such as autonomous driving simulations.

Adaptive Control#

The concept of ‘adaptive control’ within the context of high-resolution long video generation for autonomous driving suggests a system that can dynamically adjust its behavior based on the changing conditions of the environment. This is crucial because autonomous driving scenarios are highly variable, involving unpredictable elements like weather, traffic, and pedestrian movement. An adaptive control mechanism would allow the video generation model to automatically modify its parameters or strategy in response to these variations. This could involve adjusting the resolution, frame rate, or level of detail based on the complexity of the scene. For example, in simpler scenarios, lower resolution and frame rates might suffice, whereas higher fidelity might be needed during complex situations. The system may also adapt its focus and attention based on the presence of critical objects or events. Ultimately, adaptive control aims to improve efficiency and output quality by dynamically optimizing the video generation process to match the specific requirements of each driving scenario. This makes the generated data more useful for training downstream autonomous driving systems, ensuring robustness in diverse driving conditions.

Progressive Training#

Progressive training is a crucial technique in the paper for effectively generating high-resolution, long videos. The approach involves a three-stage training process, beginning with low-resolution images, advancing to short low-resolution videos, and finally culminating in high-resolution long videos. This gradual increase in complexity allows the model to master fundamental aspects of video generation before tackling the intricate challenges of high resolution and long durations. This stepwise approach avoids overwhelming the model with excessively complex data early in the training process, leading to improved convergence. The methodology demonstrates a systematic learning process, building upon the previously acquired knowledge at each stage. This method is particularly effective when training complex generative models, as it helps to prevent early overfitting and guides the model toward a more robust and generalizable representation of the data. By incorporating varied resolutions and durations of training data in the final stage, the model is further strengthened to handle a wider range of inputs, facilitating successful extrapolation beyond the training data set for longer video generation, a critical aspect for autonomous driving applications.

High-Res, Long Vid#

The concept of “High-Res, Long Vid” generation in the context of autonomous driving presents significant challenges and opportunities. High resolution is crucial for accurate perception, enabling autonomous systems to discern fine details and distant objects. Long videos, on the other hand, provide essential temporal context, vital for understanding complex driving scenarios and improving model robustness. The combination of both—High-Res, Long Vid generation—is particularly demanding, requiring significant advancements in model scalability and controllability. While generating high-resolution images is computationally expensive, extending this to long video sequences drastically increases the computational load. Therefore, efficient model architectures and training strategies are vital. Furthermore, precise control over spatial and temporal details within the generated videos is also critical. The generated content must realistically reflect road conditions, vehicle positions, and other environmental factors to be useful for simulation or training. Successfully addressing these challenges will lead to substantial advancements in autonomous driving technology, enabling the creation of more realistic and effective training datasets and simulation environments. This research is at the forefront of autonomous driving innovation, potentially revolutionizing how we train and test self-driving systems.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for high-resolution long video generation in autonomous driving could focus on enhancing scalability to handle even more complex and extensive real-world scenarios. Improving the efficiency of the models is crucial, reducing computational costs for real-time applications. Exploration of novel control mechanisms that allow more nuanced and fine-grained manipulation of video content will unlock further potential. A critical area is also improving generalization: current models struggle when facing unseen or unusual situations. Therefore, developing more robust models capable of adapting to unexpected events is vital. Finally, integrating diverse data sources could significantly improve performance and realism. Combining data from various sensors (LiDAR, radar, GPS) with high-quality video data, and possibly incorporating semantic data, would allow models to generate more detailed and accurate depictions of the driving environment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

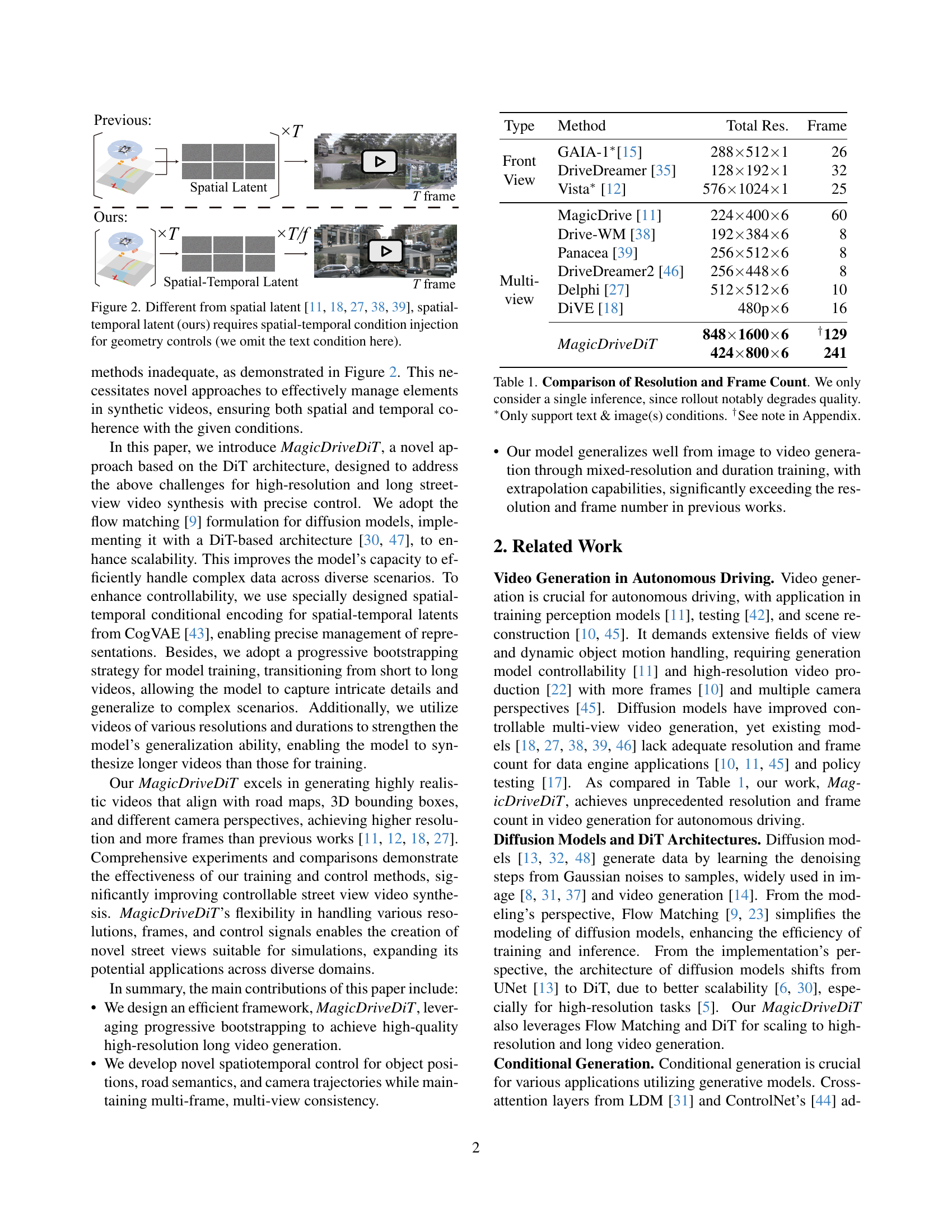

🔼 Figure 2 illustrates the core difference between existing video generation methods and the proposed MagicDriveDiT approach. Existing methods typically utilize spatial latents to control video generation, meaning that control signals are only associated with spatial locations within each frame. This limits their ability to precisely manipulate the temporal aspects of video synthesis. In contrast, MagicDriveDiT employs spatial-temporal latents. This requires injecting spatial and temporal condition signals, not just spatial ones. This allows for more precise and nuanced control over the video’s spatiotemporal dynamics, enabling more realistic and coherent video generation, especially crucial for long video generation where temporal consistency is paramount.

read the caption

Figure 2: Different from spatial latent [11, 39, 38, 27, 18], spatial-temporal latent (ours) requires spatial-temporal condition injection for geometry controls (we omit the text condition here).

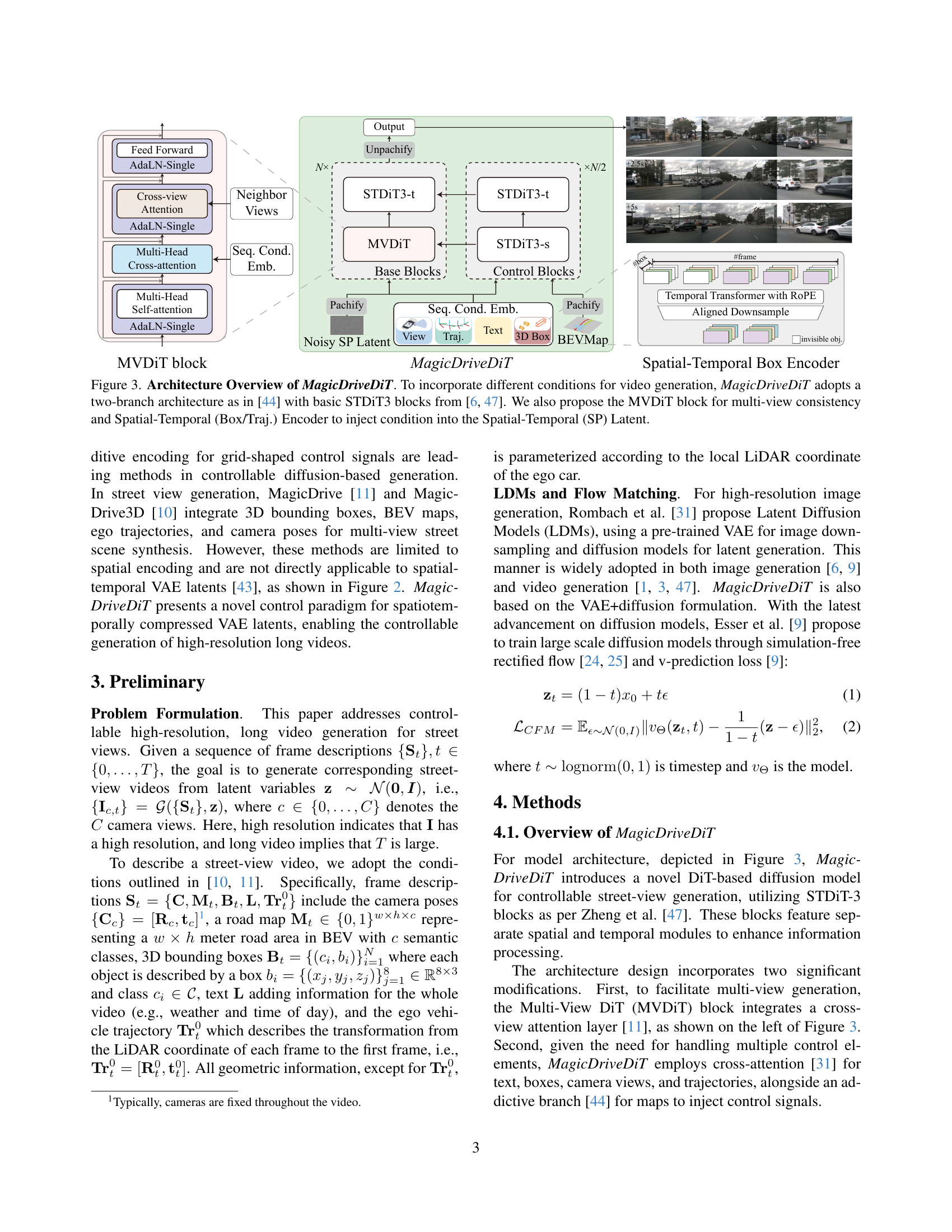

🔼 Figure 3 provides a detailed architecture overview of the MagicDriveDiT model, focusing on how it handles various conditions for video generation. It uses a two-branch architecture (similar to [44]) with STDiT3 blocks ([6, 47]) as the foundation. A key innovation is the introduction of a Multi-View DiT (MVDiT) block for maintaining consistency across multiple views. The model also features a Spatial-Temporal (Box/Traj.) Encoder to effectively integrate control signals (like bounding boxes and trajectories) directly into the spatial-temporal latents, thus enabling precise control over the generated video content.

read the caption

Figure 3: Architecture Overview of MagicDriveDiT. To incorporate different conditions for video generation, MagicDriveDiT adopts a two-branch architecture as in [44] with basic STDiT3 blocks from [6, 47]. We also propose the MVDiT block for multi-view consistency and Spatial-Temporal (Box/Traj.) Encoder to inject condition into the Spatial-Temporal (SP) Latent.

🔼 Figure 4 illustrates the architecture of the spatial-temporal encoders for maps and 3D bounding boxes used in MagicDriveDiT. The spatial encoding module, based on the design in reference [11], processes spatial information from these control signals. The temporal encoding component leverages the downsampling strategy employed by the 3D Variational Autoencoder (VAE) from reference [43]. This integration ensures temporal alignment between the control signals and the video latents, enhancing the model’s ability to control the generation of high-resolution, long videos.

read the caption

Figure 4: Spatial-Temporal Encoder for Maps (a) and Boxes (b). Our spatial encoding module follows [11], and temporal encoding integrates the downsampling strategy in our 3D VAE [43], resulting in temporally aligned embedding between the control signals and video latents.

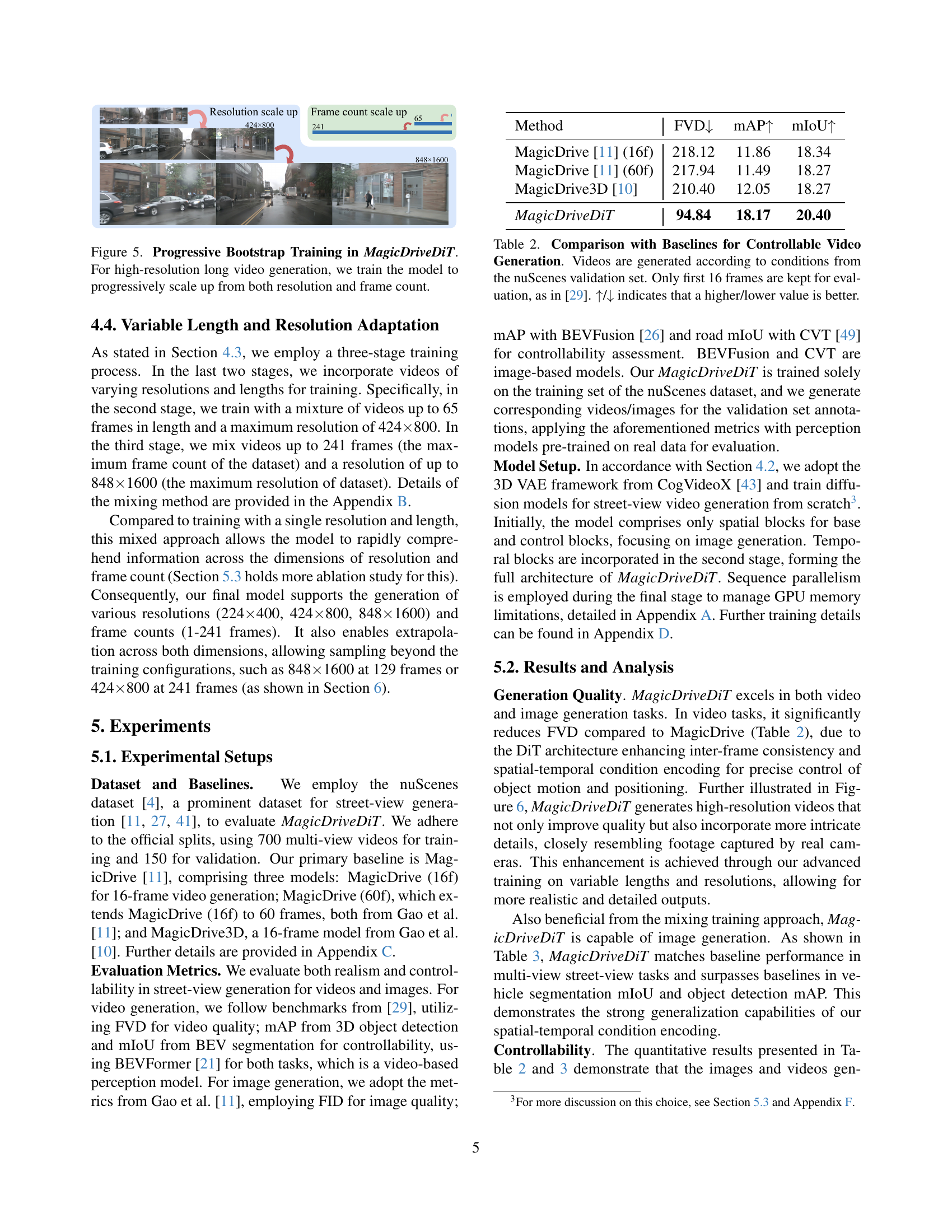

🔼 This figure illustrates the progressive training strategy used in MagicDriveDiT to generate high-resolution and long videos. The model is initially trained on low-resolution images, then progressively trained on low-resolution videos of increasing length, and finally on high-resolution videos of increasing length. This stepwise approach allows the model to gradually learn to generate more complex and realistic videos. The training process starts with low-resolution images (224x400) and a few frames and progresses through increasing video lengths (9,17,33,65 frames) and higher resolutions (424x800 and 848x1600).

read the caption

Figure 5: Progressive Bootstrap Training in MagicDriveDiT. For high-resolution long video generation, we train the model to progressively scale up from both resolution and frame count.

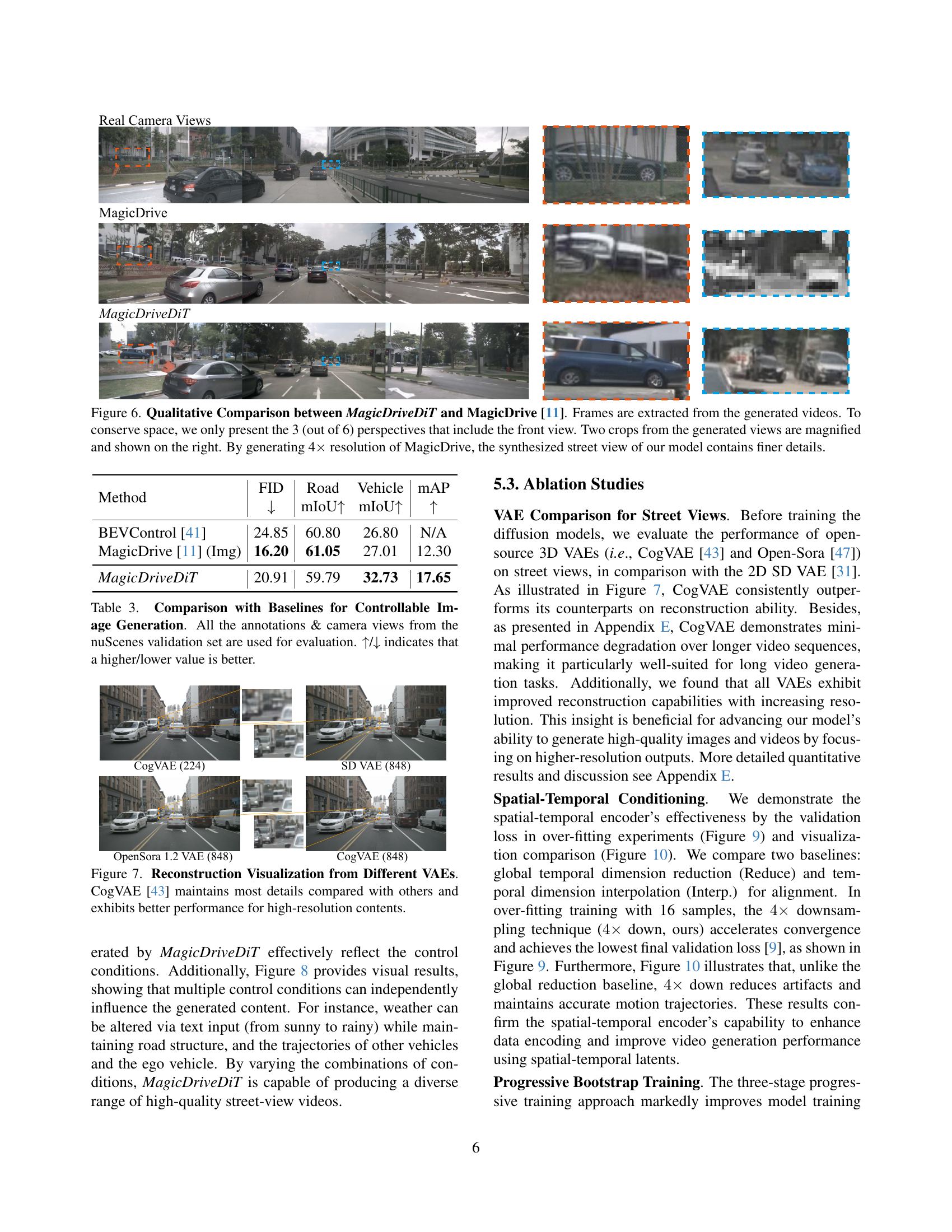

🔼 Figure 6 presents a qualitative comparison of street scene videos generated by MagicDriveDiT and MagicDrive [11]. It showcases the improved visual quality and resolution achieved by MagicDriveDiT. The figure displays frames extracted from generated videos, focusing on three out of six perspectives that include the front view for brevity. To highlight the increased detail, two crops from the generated views are magnified and presented alongside the original frames. MagicDriveDiT demonstrates its superior performance by generating videos with 4 times the resolution of MagicDrive, resulting in significantly finer details and a more realistic street scene representation.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative Comparison between MagicDriveDiT and MagicDrive [11]. Frames are extracted from the generated videos. To conserve space, we only present the 3 (out of 6) perspectives that include the front view. Two crops from the generated views are magnified and shown on the right. By generating 4×\times× resolution of MagicDrive, the synthesized street view of our model contains finer details.

🔼 Figure 7 presents a comparison of reconstruction quality from three different variational autoencoders (VAEs): CogVAE [43], SD-VAE, and OpenSora VAE. Each VAE was used to reconstruct high-resolution images from the nuScenes dataset. The figure visually demonstrates that CogVAE [43] achieves superior reconstruction quality, preserving significantly more detail than the other VAEs tested, particularly in high-resolution scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 7: Reconstruction Visualization from Different VAEs. CogVAE [43] maintains most details compared with others and exhibits better performance for high-resolution contents.

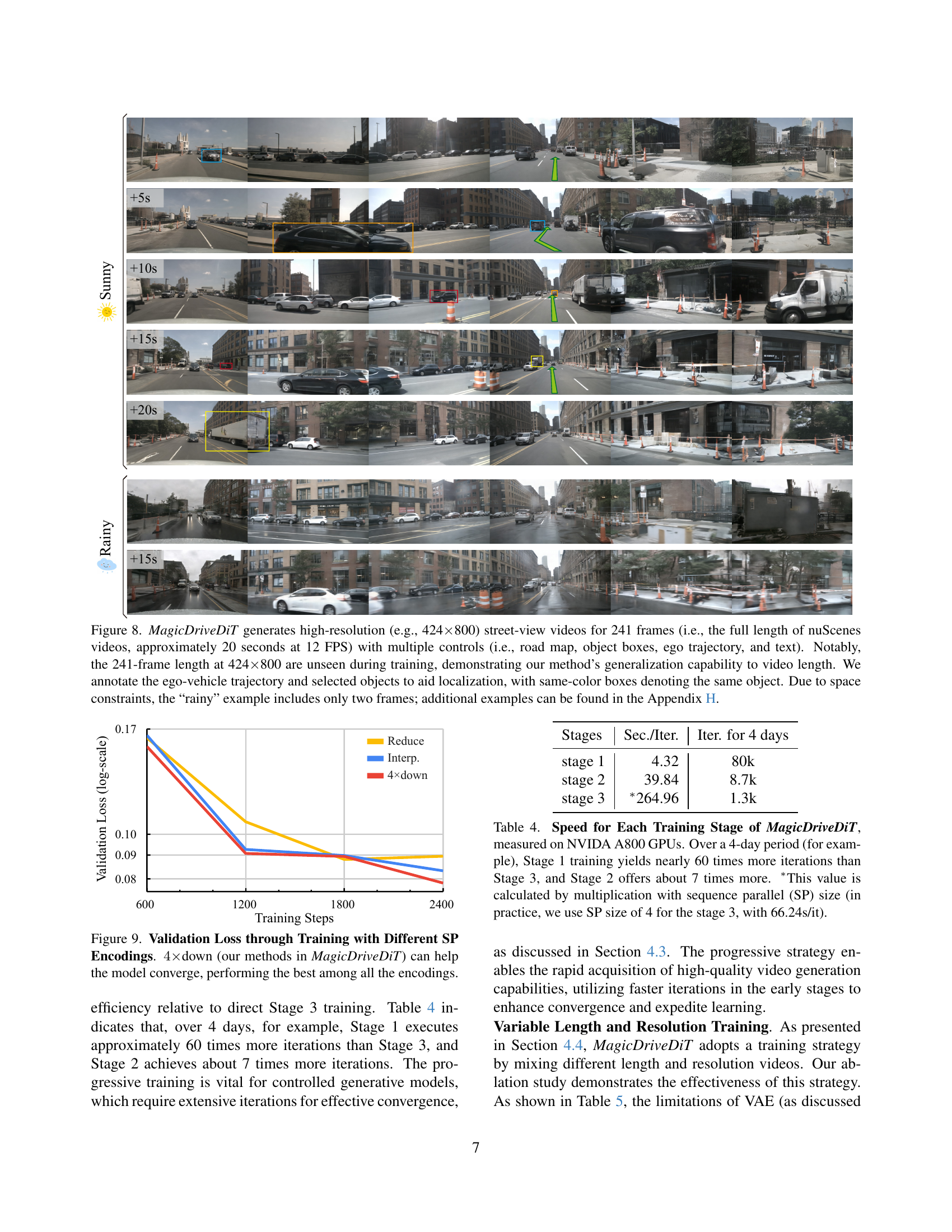

🔼 Figure 8 showcases MagicDriveDiT’s ability to generate high-resolution (424x800) and long (241 frames, ~20 seconds at 12 FPS) street-view videos. The impressive aspect is that the model generalizes to this video length, despite not seeing such long sequences during training. The figure demonstrates this by displaying videos under both sunny and rainy conditions. The video includes multiple controls (road map, object boxes, ego trajectory, text), which are used by the model to generate the realistic street scenes. For better visualization, the ego-vehicle trajectory and selected objects are annotated with same-colored boxes representing the same object across frames. Due to space limitations, only two frames are shown for the rainy condition. More examples are provided in Appendix H.

read the caption

Figure 8: MagicDriveDiT generates high-resolution (e.g., 424×\times×800) street-view videos for 241 frames (i.e., the full length of nuScenes videos, approximately 20 seconds at 12 FPS) with multiple controls (i.e., road map, object boxes, ego trajectory, and text). Notably, the 241-frame length at 424×\times×800 are unseen during training, demonstrating our method’s generalization capability to video length. We annotate the ego-vehicle trajectory and selected objects to aid localization, with same-color boxes denoting the same object. Due to space constraints, the “rainy” example includes only two frames; additional examples can be found in the Appendix H.

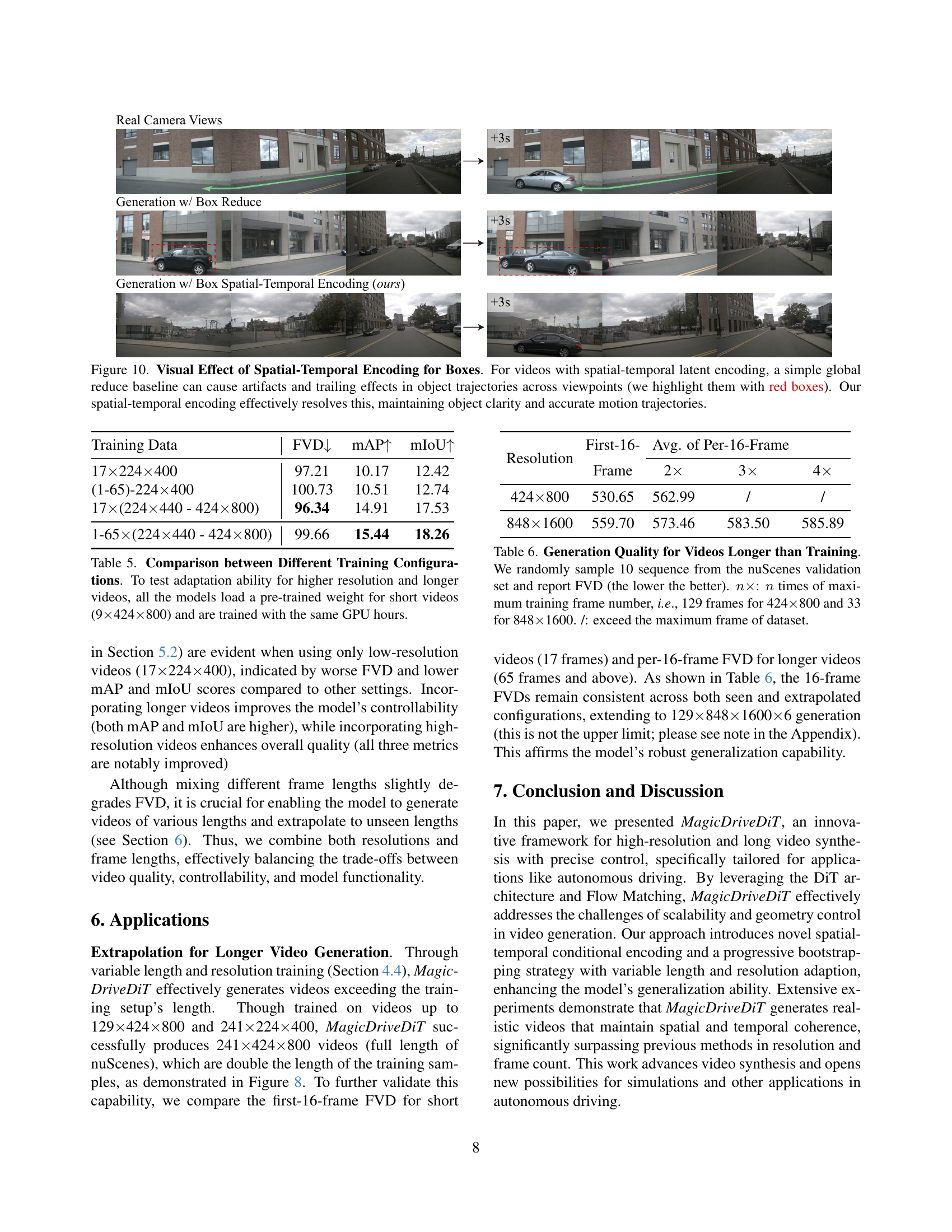

🔼 This figure displays the validation loss curves during training for different spatial-temporal encoding methods used in MagicDriveDiT. The x-axis represents training steps and the y-axis shows the validation loss (log scale). Three lines represent different encoding methods: one is a baseline method using a global reduction of the temporal dimension, another is a baseline method using interpolation for temporal alignment, and the final line represents the authors’ proposed method using 4x downsampling with a spatial-temporal encoder. The results demonstrate that the proposed 4x downsampling method significantly improves model convergence, resulting in lower validation loss compared to the two baseline methods.

read the caption

Figure 9: Validation Loss through Training with Different SP Encodings. 4×4\times4 ×down (our methods in MagicDriveDiT) can help the model converge, performing the best among all the encodings.

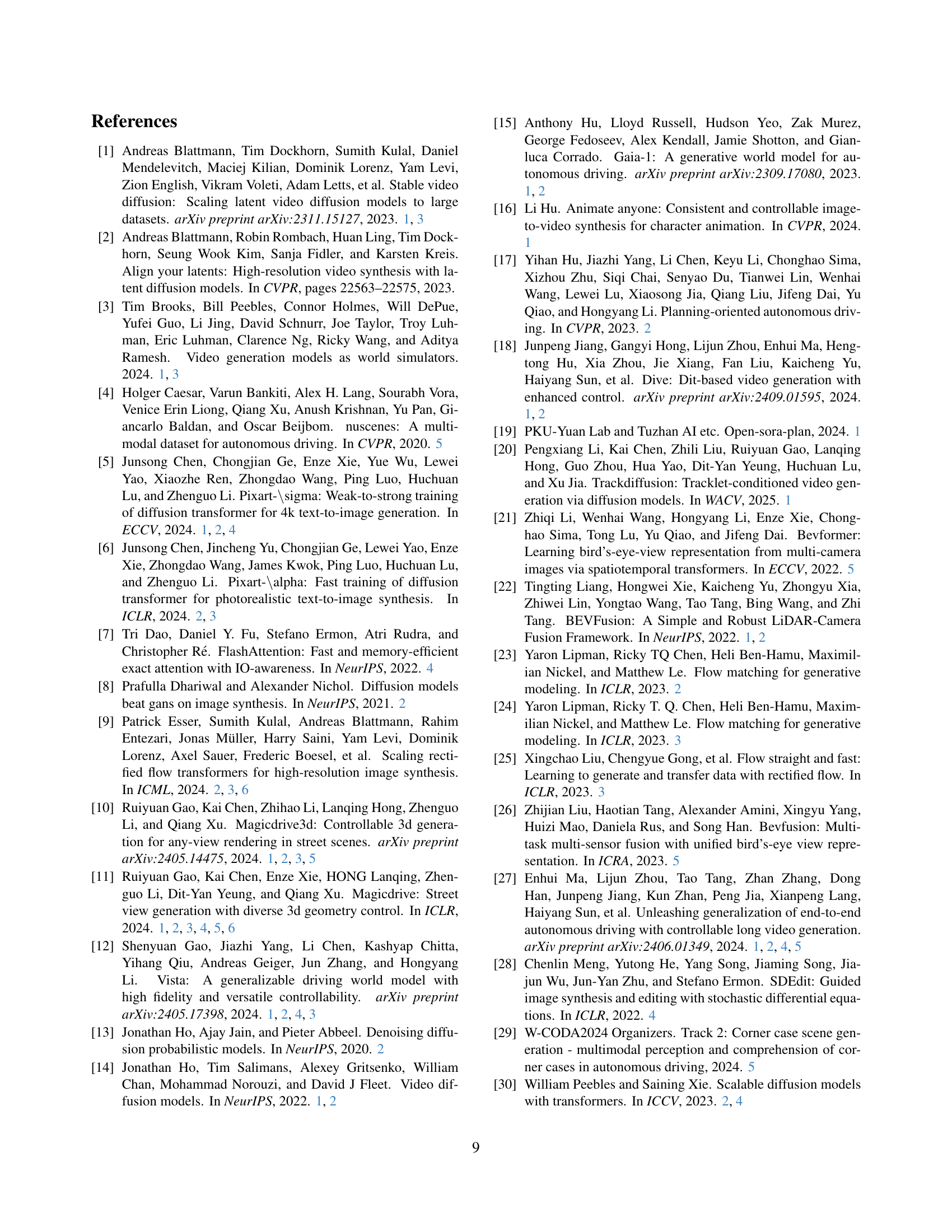

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of spatial-temporal encoding on handling object trajectories in multi-view videos. The top row shows video frames generated without proper spatial-temporal alignment. A simple ‘global reduce’ method is used, leading to artifacts and trailing effects in object trajectories across different viewpoints (highlighted in red). The bottom row shows frames from a video generated using the authors’ spatial-temporal encoding technique. This approach effectively resolves the issues observed in the top row, maintaining the clarity and accuracy of object trajectories across viewpoints.

read the caption

Figure 10: Visual Effect of Spatial-Temporal Encoding for Boxes. For videos with spatial-temporal latent encoding, a simple global reduce baseline can cause artifacts and trailing effects in object trajectories across viewpoints (we highlight them with red boxes). Our spatial-temporal encoding effectively resolves this, maintaining object clarity and accurate motion trajectories.

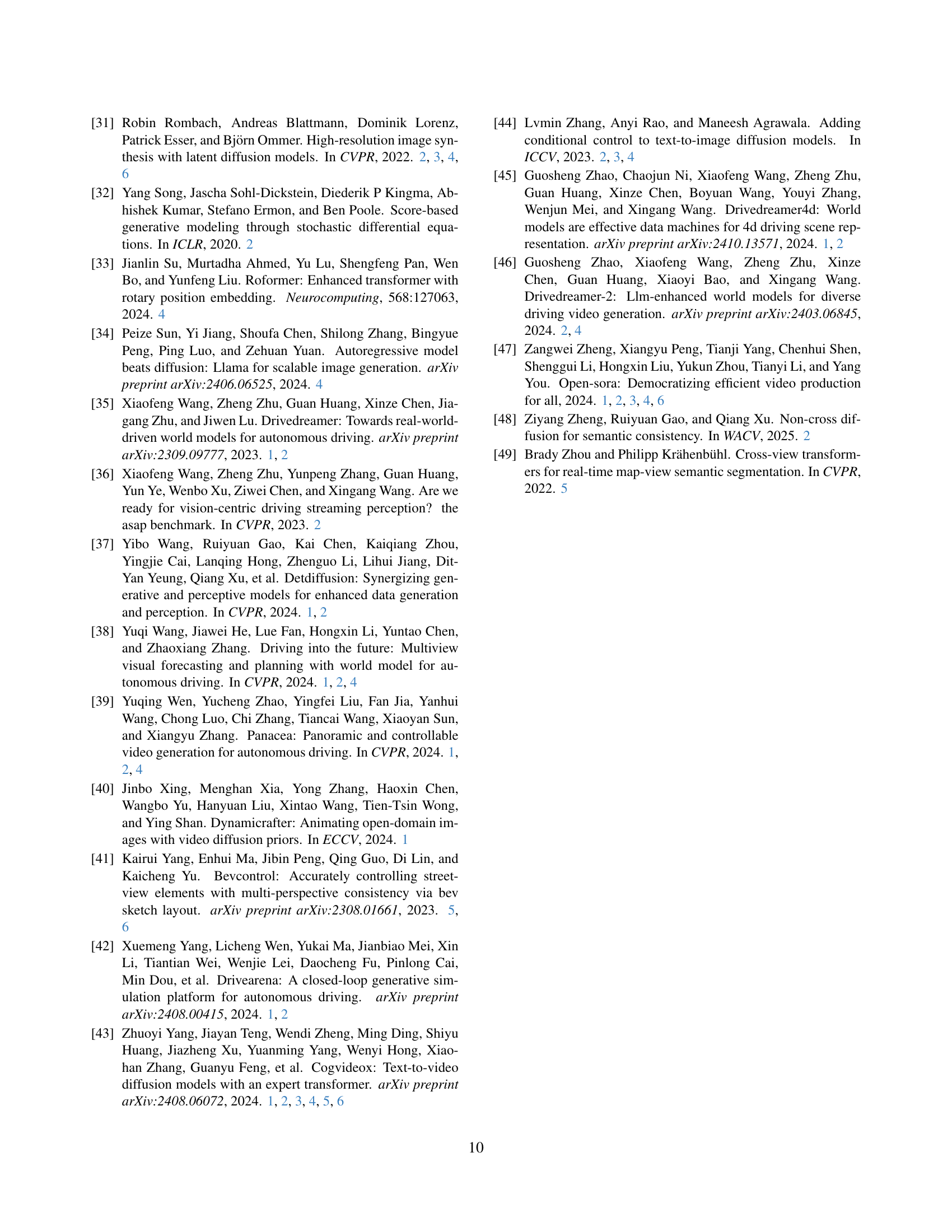

🔼 This figure illustrates the sequence parallel training strategy used to handle long video sequences. The left panel shows how the spatial dimension of the input is split across multiple GPUs before the first block of the network and gathered back together after the last block. The right panel details the all-to-all communication used within each attention module to efficiently manage the data across the GPUs. The annotations define the variables: B (batch size), T (temporal dimension), S (spatial dimension), D (latent dimension), HD (number of heads), CH (per-head dimension), and SP (sequence parallel size).

read the caption

Figure I: Diagram for Sequence Parallel. Left: We split the spatial dimension before the first block and gather them after the last block. Right: For each attention module, we use all-to-all communication, changing the splitting dimension to attention heads. B: batch; T: temporal dimension; S: spatial dimension; D: latent dimension; HD: number of heads; CH: per-head dimension; SP: sequence parallel size.

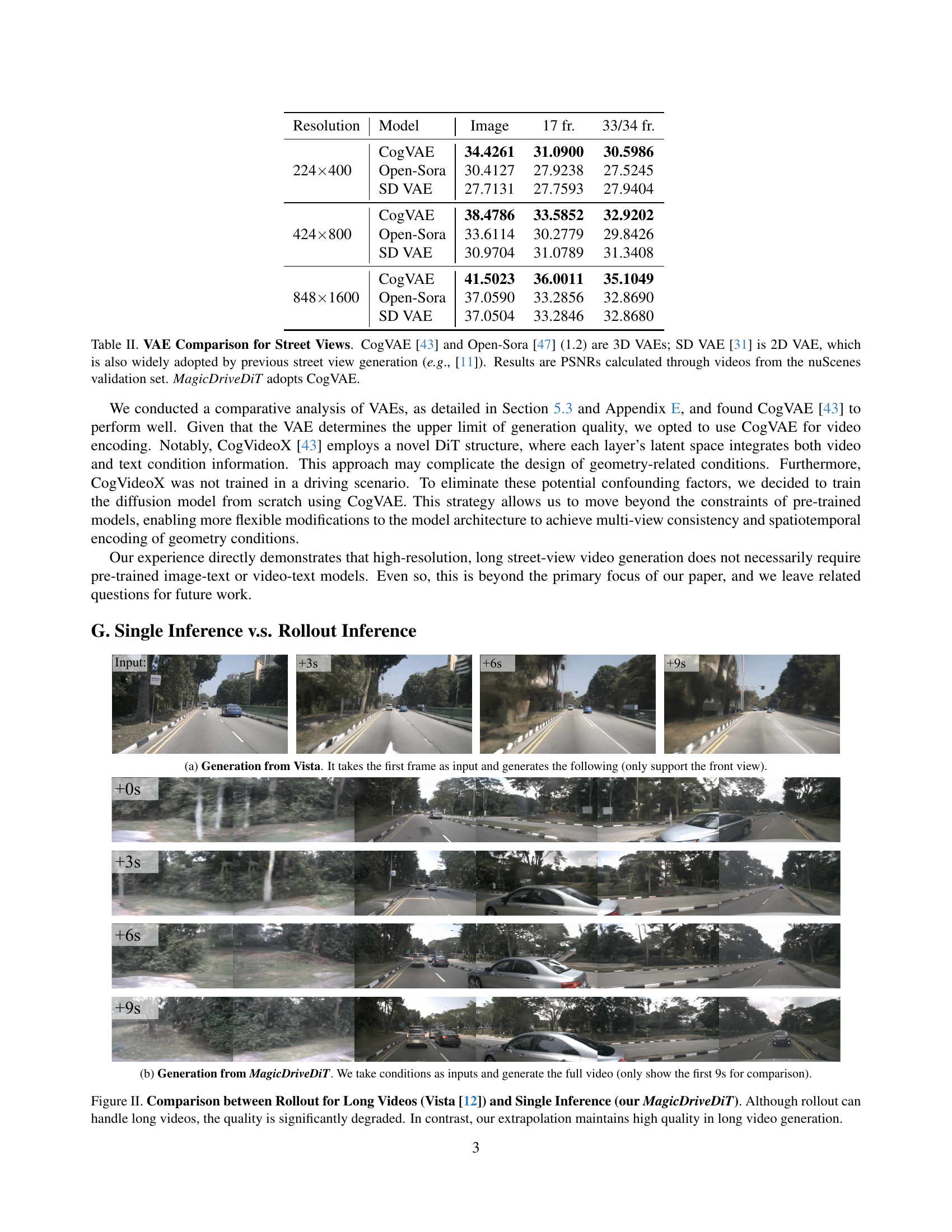

🔼 This figure compares the video generation quality between Vista and MagicDriveDiT. Vista uses a rollout method, taking the last frame of each inference as the input for the next inference. This method is limited in the length of generated videos and the quality decreases as the length increases. In contrast, MagicDriveDiT generates high-quality long videos without the rollout method, showing its ability to maintain quality in longer sequences.

read the caption

(a) Generation from Vista. It takes the first frame as input and generates the following (only support the front view).

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of video generation between the Vista method and the MagicDriveDiT method. The Vista method uses a rollout approach, where the last frames from one prediction are used as input to the next, creating a sequence. This is shown in subfigure (a) only shows the first 9 seconds of the video for brevity. In contrast, subfigure (b) shows the first 9 seconds of a video created by the MagicDriveDiT method, which generates the full video directly from the input conditions.

read the caption

(b) Generation from MagicDriveDiT. We take conditions as inputs and generate the full video (only show the first 9s for comparison).

🔼 Figure II demonstrates a comparison of long video generation methods. Vista [12], employing a rollout approach (where predictions from previous frames are used as input for the next), produces videos of considerable length. However, the image quality degrades significantly due to accumulated prediction errors. In contrast, MagicDriveDiT, using a single inference, generates high-quality videos that maintain quality even at longer durations by extrapolating from shorter video sequences learned during training. This showcases the superior performance of MagicDriveDiT in producing long videos while preserving the quality of the generated content.

read the caption

Figure II: Comparison between Rollout for Long Videos (Vista [12]) and Single Inference (our MagicDriveDiT). Although rollout can handle long videos, the quality is significantly degraded. In contrast, our extrapolation maintains high quality in long video generation.

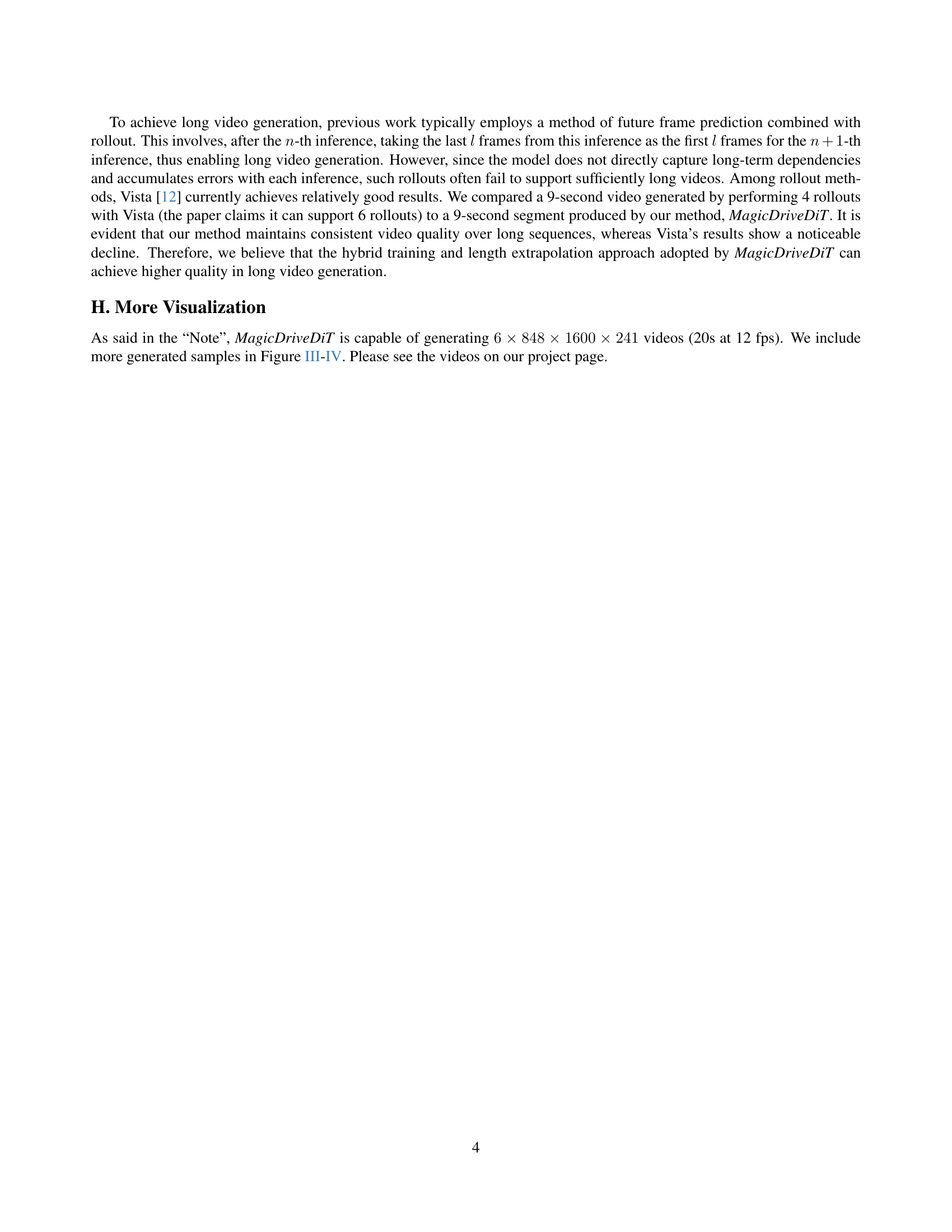

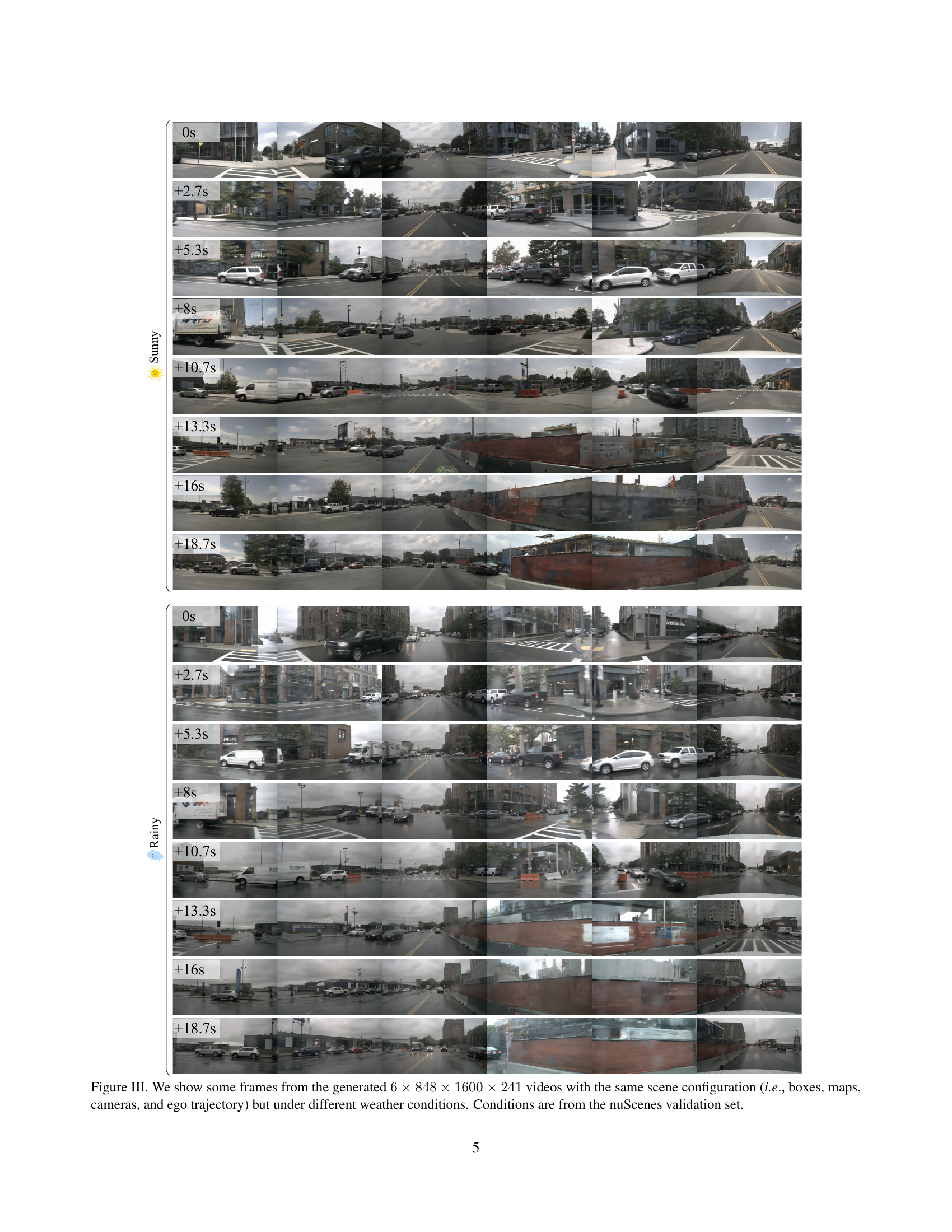

🔼 Figure III presents a visual comparison of video frames generated using the MagicDriveDiT model under varying weather conditions. The model is given the same scene configuration (3D bounding boxes, bird’s-eye view map, camera positions and ego-vehicle trajectory). However, the weather condition (sunny or rainy) is changed as a control input. Each row shows frames from a 241-frame long video at 848x1600 resolution, captured at different time points (+0s, +2.7s, +5.3s, and so on). This demonstrates the model’s capacity to generate realistic videos with consistent scene elements while modifying specified attributes (weather) in a controlled manner.

read the caption

Figure III: We show some frames from the generated 6×848×1600×241684816002416\times 848\times 1600\times 2416 × 848 × 1600 × 241 videos with the same scene configuration (i.e., boxes, maps, cameras, and ego trajectory) but under different weather conditions. Conditions are from the nuScenes validation set.

More on tables

| Method | FVD↓ | mAP↑ | mIoU↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| MagicDrive [11] (16f) | 218.12 | 11.86 | 18.34 |

| MagicDrive [11] (60f) | 217.94 | 11.49 | 18.27 |

| MagicDrive3D [10] | 210.40 | 12.05 | 18.27 |

| MagicDriveDiT | 94.84 | 18.17 | 20.40 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of MagicDriveDiT with several baseline methods on controllable video generation. The videos were generated using conditions from the nuScenes validation set, and only the first 16 frames of each generated video were used for evaluation, consistent with the methodology in paper [29]. The metrics used for comparison include FVD (lower is better), indicating video quality, mAP (higher is better), measuring the accuracy of object detection, and mIoU (higher is better), representing the accuracy of road map segmentation. The arrows indicate whether a higher or lower value is preferred for each metric.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison with Baselines for Controllable Video Generation. Videos are generated according to conditions from the nuScenes validation set. Only first 16 frames are kept for evaluation, as in [29]. ↑↑\uparrow↑/↓↓\downarrow↓ indicates that a higher/lower value is better.

| Method | FID ↓ | Road mIoU ↑ | Vehicle mIoU ↑ | mAP ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEVControl [41] | 24.85 | 60.80 | 26.80 | N/A |

| MagicDrive [11] (Img) | 16.20 | 61.05 | 27.01 | 12.30 |

| MagicDriveDiT | 20.91 | 59.79 | 32.73 | 17.65 |

🔼 Table 3 presents a comparison of the performance of MagicDriveDiT against several baselines on controllable image generation. The evaluation uses all annotations and camera views from the nuScenes validation set. Metrics used include FID (lower is better, indicating higher image quality), Road mIoU, Vehicle mIoU (both higher is better, representing better segmentation accuracy), and mAP (higher is better, demonstrating superior object detection performance). This table highlights MagicDriveDiT’s performance relative to established methods in generating realistic and controllable street-view images.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison with Baselines for Controllable Image Generation. All the annotations & camera views from the nuScenes validation set are used for evaluation. ↑↑\uparrow↑/↓↓\downarrow↓ indicates that a higher/lower value is better.

| FID | |

|---|---|

| ↓ |

🔼 This table presents the training speed for each stage of the MagicDriveDiT model, using NVIDIA A800 GPUs. The training process is divided into three stages with varying resolutions and video lengths. The table shows the seconds per iteration and the total number of iterations achieved over a four-day period for each stage. Stage 1, which uses low-resolution images, completes significantly more iterations than Stages 2 and 3, which use higher-resolution videos of increasing length. The asterisk (*) indicates that the time per iteration for Stage 3 is calculated using a sequence parallel (SP) size of 4, resulting in a longer time per iteration compared to Stages 1 and 2. The data highlights the efficiency of the progressive training strategy.

read the caption

Table 4: Speed for Each Training Stage of MagicDriveDiT, measured on NVIDA A800 GPUs. Over a 4-day period (for example), Stage 1 training yields nearly 60 times more iterations than Stage 3, and Stage 2 offers about 7 times more. ∗This value is calculated by multiplication with sequence parallel (SP) size (in practice, we use SP size of 4 for the stage 3, with 66.24s/it).

| Road | mIoU↑ |

|---|

🔼 This table compares the performance of models trained with different configurations to assess their ability to adapt to higher resolutions and longer video sequences. All models began with pre-trained weights from a short video dataset (9 frames of 424x800 resolution). The training time (GPU hours) was kept constant across all configurations. The table shows how varying the training data (resolution and length of videos) affects the final model’s performance as measured by FVD (lower is better), mAP, and mIoU (higher is better). This helps to determine which training approach leads to the best generalization for generating high-resolution, long videos.

read the caption

Table 5: Comparison between Different Training Configurations. To test adaptation ability for higher resolution and longer videos, all the models load a pre-trained weight for short videos (9×\times×424×\times×800) and are trained with the same GPU hours.

| Vehicle | mIoU↑ |

|---|

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the quality of videos generated by the model, specifically focusing on videos that are longer than those used during the model’s training phase. The quality is measured using the FVD metric (lower is better). Ten video sequences were randomly selected from the nuScenes validation set for this evaluation. The table indicates how many times the number of frames in the generated videos exceed the maximum number of frames seen during training (indicated by ’n’). The symbol ‘/’ denotes cases where the generated videos’ frame counts surpassed those in the training data.

read the caption

Table 6: Generation Quality for Videos Longer than Training. We randomly sample 10 sequence from the nuScenes validation set and report FVD (the lower the better). n×n\timesitalic_n ×: n𝑛nitalic_n times of maximum training frame number, i.e., 129 frames for 424×\times×800 and 33 for 848×\times×1600. /: exceed the maximum frame of dataset.

| mAP | |

|---|---|

| ↑ |

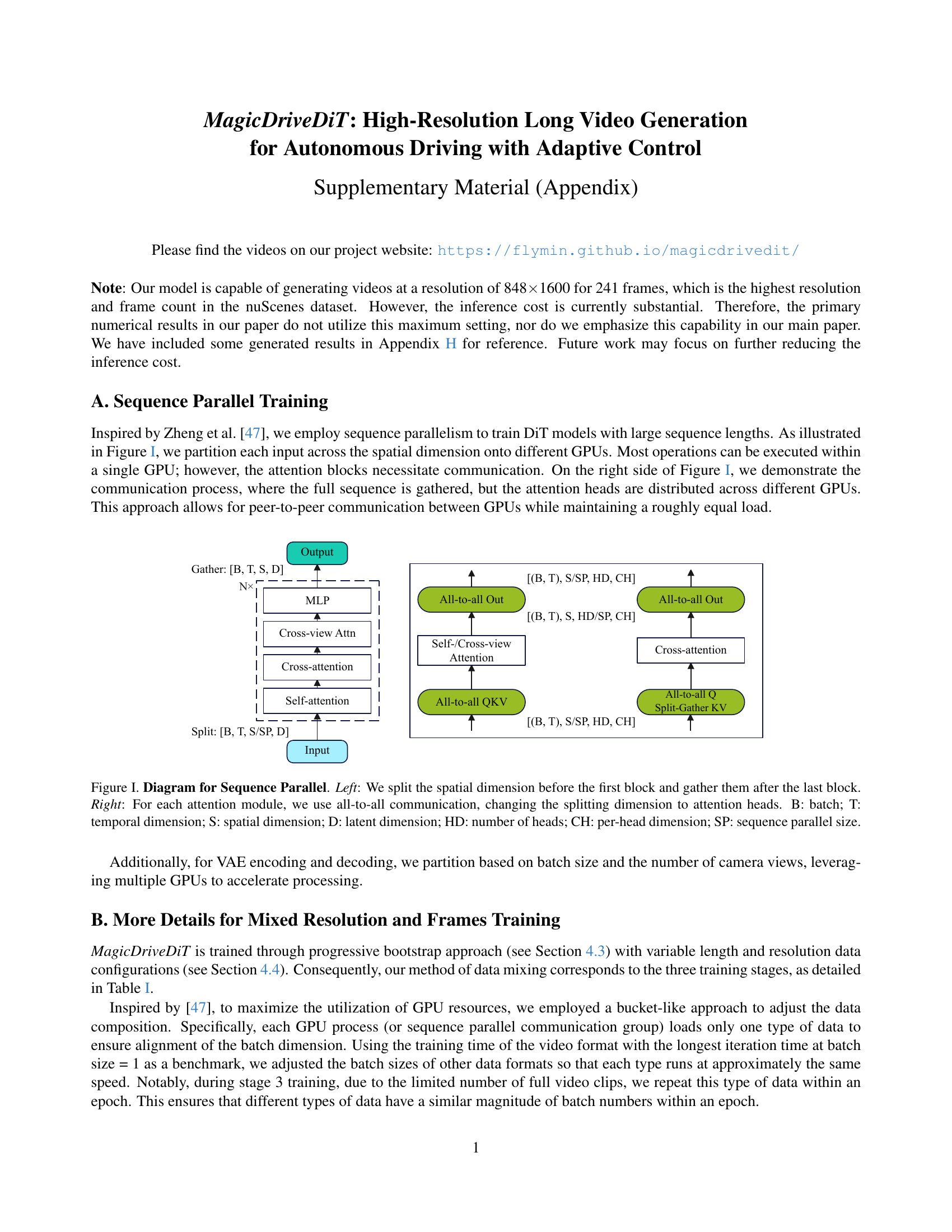

🔼 This table details the training configurations for MagicDriveDiT across three stages. The progressive bootstrap training approach starts with low-resolution images, then moves to low-resolution short videos, and finally high-resolution long videos. Each stage uses a mix of video lengths and resolutions to improve model generalization and performance. The table shows the resolution, number of frames, sequence parallelism setting, and number of training steps for each stage.

read the caption

Table I: Configuration for Variable Length and Resolution Training. The mixing configuration aligns with our progressive bootstrap training with 3 stages, from low-resolution images to high-resolution long videos.

| Stages | Sec./Iter. | Iter. for 4 days |

|---|---|---|

| stage 1 | 4.32 | 80k |

| stage 2 | 39.84 | 8.7k |

| stage 3 | *264.96 | 1.3k |

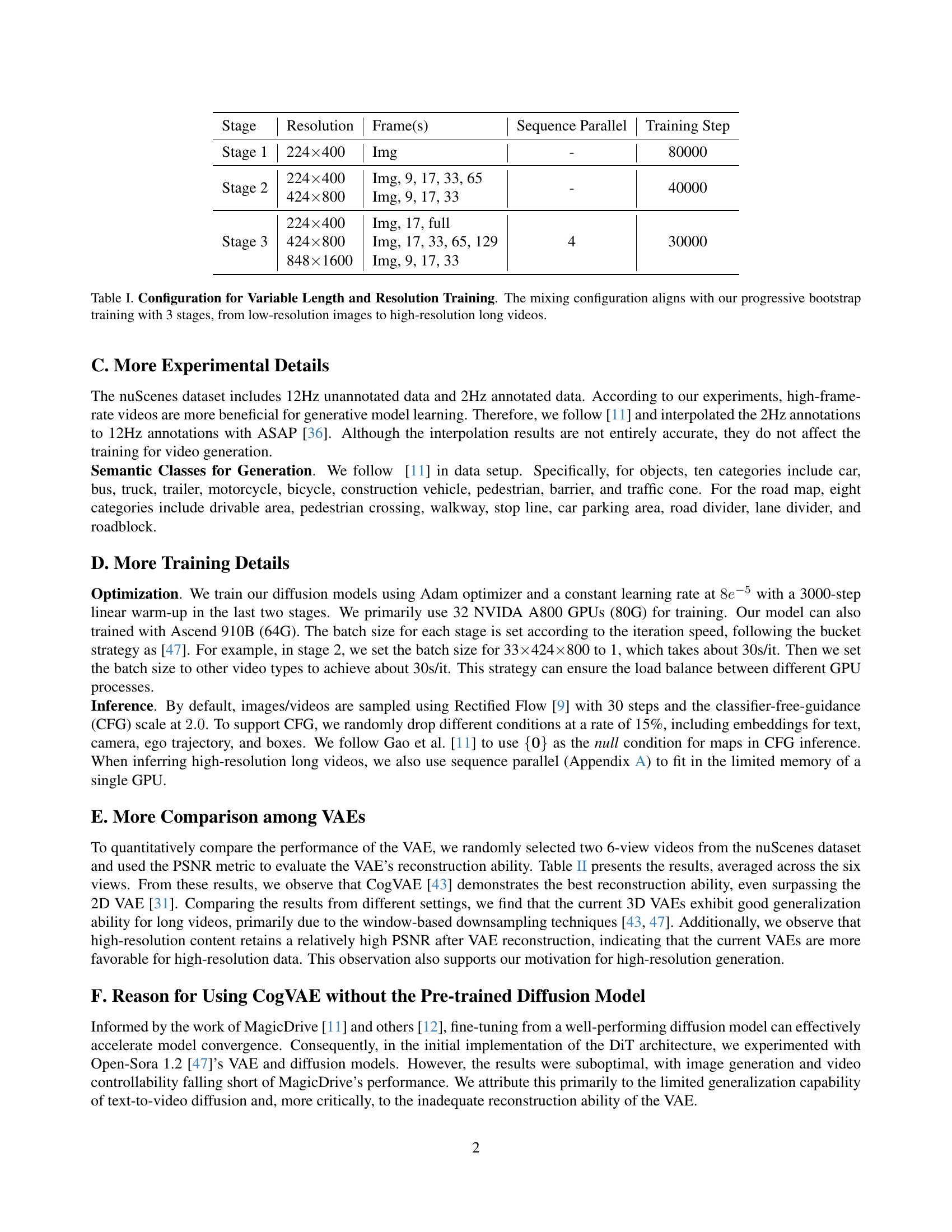

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for reconstructing street view videos from the nuScenes dataset. CogVAE and Open-Sora are 3D VAEs, while SD VAE is a 2D VAE commonly used in previous street view generation methods. The comparison is based on the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) calculated from the reconstructed videos. The results show the PSNR values for different resolutions (224x400, 424x800, 848x1600) and video lengths (17 frames, 33/34 frames). The MagicDriveDiT model utilizes the CogVAE.

read the caption

Table II: VAE Comparison for Street Views. CogVAE [43] and Open-Sora [47] (1.2) are 3D VAEs; SD VAE [31] is 2D VAE, which is also widely adopted by previous street view generation (e.g., [11]). Results are PSNRs calculated through videos from the nuScenes validation set. MagicDriveDiT adopts CogVAE.

Full paper#