↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current video tokenization methods struggle with long videos due to high computational costs and memory constraints. Training on short clips limits the exploitation of temporal coherence, impacting model performance. This leads to limitations in video understanding and generation tasks involving longer video sequences.

This paper introduces CoordTok, a novel video tokenizer which learns a mapping from coordinate-based representations to video patches. This enables training on long videos without excessive resources, significantly reducing token counts and improving model performance. CoordTok’s efficient tokenization enables memory-efficient training of diffusion transformers for high-quality long video generation, showcasing the benefits of exploiting the temporal coherence in longer sequences.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical challenge of efficiently processing long videos in computer vision, a limitation of many existing models. By introducing a novel video tokenizer, CoordTok, it enables more efficient training of large models on longer video sequences, leading to improved performance on various downstream tasks. This opens up new avenues of research in video understanding and generation, particularly for applications involving long videos.

Visual Insights#

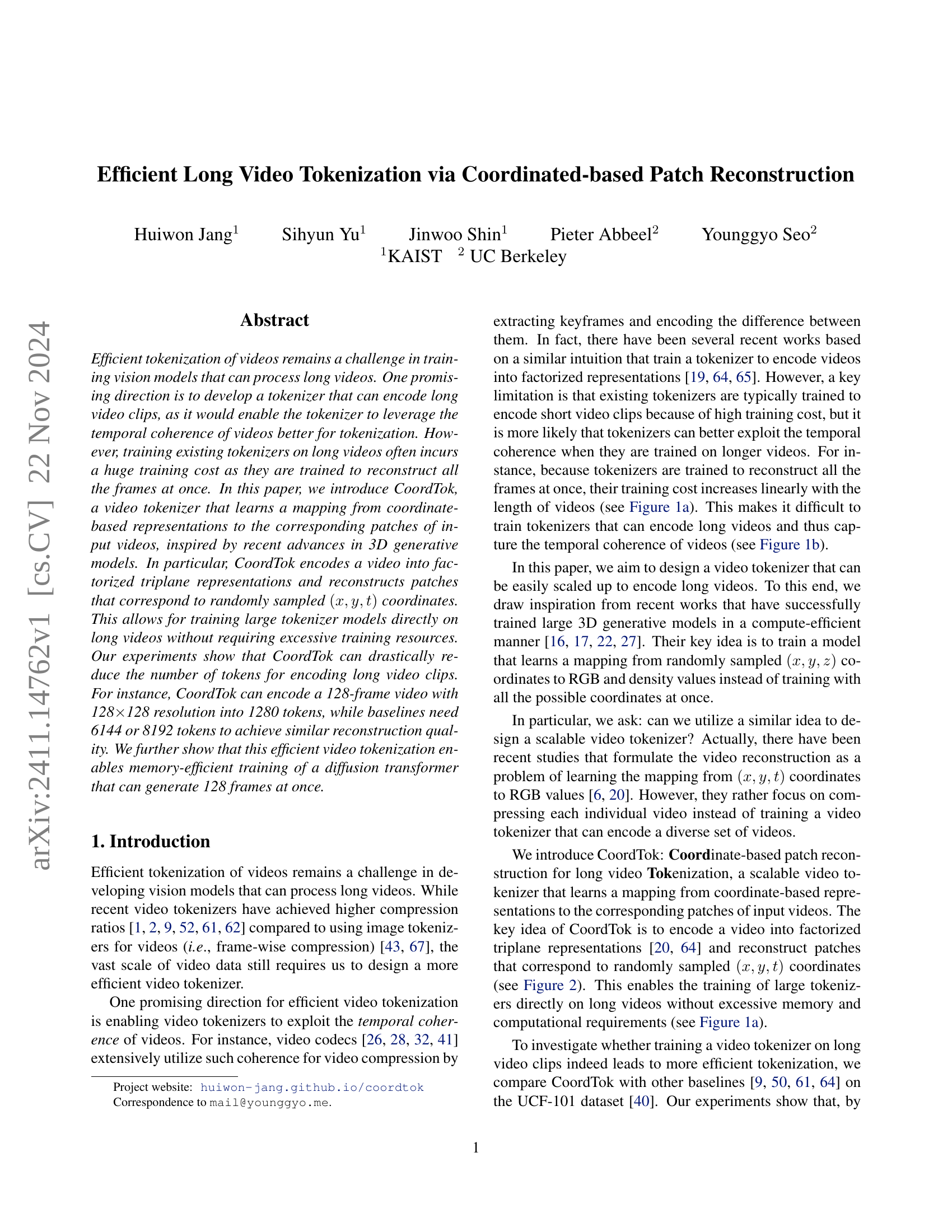

🔼 The figure shows a graph illustrating the maximum batch size achievable when training different video tokenizers on videos of varying lengths. The training was performed on videos with a resolution of 128x128 pixels using a single NVIDIA 4090 24GB GPU. The x-axis represents the video length (number of frames), and the y-axis represents the maximum batch size that could be processed without running out of GPU memory. Different video tokenizers (TATS-AE, LARP, PVDM-AE, and CoordTok) are compared, demonstrating the impact of video length on training capacity.

read the caption

(a) Maximum batch-size when training video tokenizers on 128×128128128128\times 128128 × 128 resolution videos with varying lengths, measured with a single NVIDIA 4090 24GB GPU.

| Sampling | Ratio (%) | rFVD ↓ | Max BS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random frame | 3.125 | 479 | 13 |

| Random patch | 1.563 | 401 | 21 |

| Random patch | 3.125 | 238 | 13 |

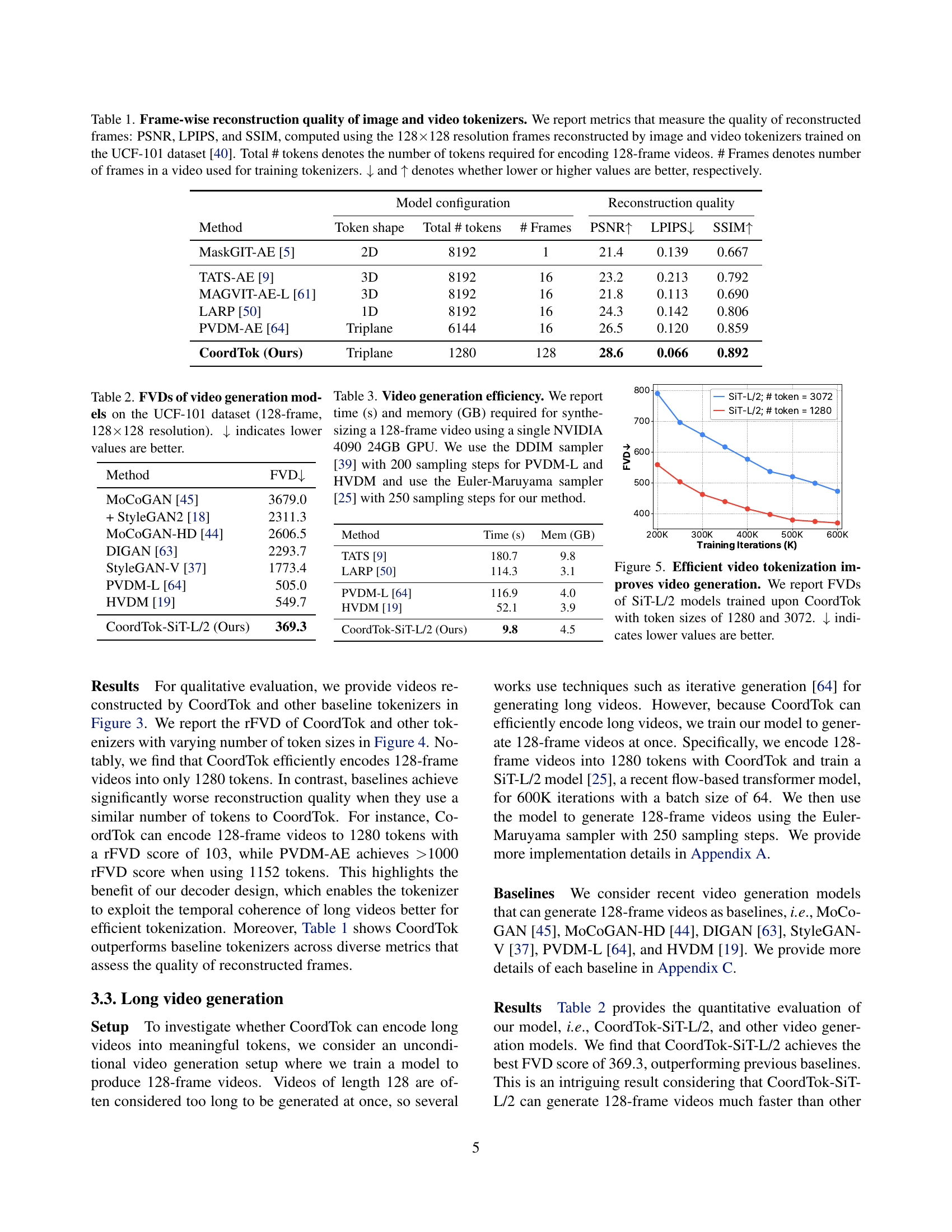

🔼 This table compares the performance of different image and video tokenizers in reconstructing 128x128 resolution video frames. It evaluates models based on the number of tokens needed to encode a 128-frame video, the number of frames used during training, and the reconstruction quality metrics PSNR (higher is better), LPIPS (lower is better), and SSIM (higher is better). The results show the trade-off between compression (number of tokens) and reconstruction accuracy across various models.

read the caption

Table 1: Frame-wise reconstruction quality of image and video tokenizers. We report metrics that measure the quality of reconstructed frames: PSNR, LPIPS, and SSIM, computed using the 128×\times×128 resolution frames reconstructed by image and video tokenizers trained on the UCF-101 dataset [40]. Total # tokens denotes the number of tokens required for encoding 128-frame videos. # Frames denotes number of frames in a video used for training tokenizers. ↓↓\downarrow↓ and ↑↑\uparrow↑ denotes whether lower or higher values are better, respectively.

In-depth insights#

Long Video Tokenization#

The concept of “Long Video Tokenization” addresses the challenge of efficiently processing lengthy video sequences for machine learning. Traditional methods often struggle with the computational cost and memory constraints associated with encoding entire long videos at once. The core idea is to develop more efficient tokenization strategies that leverage the temporal coherence inherent in videos. This involves creating compact representations of video data, drastically reducing the number of tokens needed while preserving crucial information. Efficient tokenization methods enable the training of more powerful models on longer videos, leading to better understanding of temporal dynamics and improved performance in tasks like video generation and action recognition. The key is to exploit temporal correlations within the video, moving beyond frame-by-frame processing to capture the global context and reduce redundancy. This allows for training larger models on longer sequences, leading to significant gains in downstream tasks, despite increased computational demands. However, this approach also presents challenges, requiring careful attention to the trade-offs between compression efficiency and the loss of information, as well as the computational cost associated with handling large volumes of data.

CoordTok: Method#

The proposed CoordTok method introduces a novel approach to video tokenization, focusing on efficiently encoding long videos. It cleverly leverages the idea of coordinate-based patch reconstruction, drawing inspiration from recent advances in 3D generative models. Instead of processing the entire video frame at once, CoordTok cleverly divides it into patches and learns a mapping from randomly sampled spatiotemporal coordinates (x,y,t) to the corresponding patches. This allows the model to encode long video clips without reconstructing all frames, thus drastically reducing the computational burden and enabling the training of much larger models. The model employs factorized triplane representations for compact video encoding, comprising three 2D latent planes to capture content, spatial motion, and temporal motion independently. The decoder then takes these coordinates as input and reconstructs the respective patches through a series of self-attention layers, which aggregate and fuse information across the coordinates. This innovative strategy makes CoordTok significantly more scalable to long videos than existing tokenizers while maintaining a good reconstruction quality.

Efficient Encoding#

Efficient encoding in video processing is crucial for managing the vast amounts of data involved. The core idea revolves around reducing the number of bits required to represent a video while maintaining acceptable quality. This paper explores this concept through innovative tokenization methods. CoordTok’s approach, using coordinate-based patch reconstruction, stands out by directly training on longer video clips, exploiting temporal coherence for better compression than methods trained on shorter clips. This strategy, inspired by advances in 3D generative models, effectively reduces the number of tokens needed for encoding, leading to significant memory and computational savings. The benefits extend to downstream tasks like video generation, where memory-efficient encoding allows for the generation of longer videos. The use of factorized triplane representations also contributes to efficiency by representing videos in a compact, low-dimensional latent space. However, challenges remain. The paper acknowledges that the method’s performance might be affected by the dynamics of the video content. Future improvements could potentially focus on addressing this limitation and scaling the method further for even longer videos and more complex video scenes.

Video Generation#

The research paper explores efficient long video tokenization, a crucial step impacting video generation. CoordTok, the proposed method, significantly reduces the number of tokens needed to represent long videos, which directly addresses the computational limitations of existing video generation models. By leveraging temporal coherence through coordinate-based patch reconstruction, CoordTok enables memory-efficient training of diffusion transformers, leading to the generation of longer, more coherent video sequences. The results demonstrate a substantial improvement in video reconstruction quality and efficiency compared to baselines. The ability to generate 128 frames at once highlights the significant advancement in generating longer videos, overcoming limitations that previously restricted most models to shorter clips. However, the paper also acknowledges limitations, particularly concerning the handling of highly dynamic videos. Future directions include incorporating techniques from video codecs to address this, further improving scalability and efficiency of both tokenization and generation.

Future Directions#

The research paper explores efficient long video tokenization using a novel approach, CoordTok. Looking towards the future, several promising avenues for improvement emerge. Extending CoordTok to handle even longer videos and higher resolutions is crucial, pushing beyond the current 128 frames and 128x128 resolution. This necessitates investigation into more efficient memory management techniques and potentially exploring alternative architectures better suited for extremely large-scale datasets. Addressing the limitations in handling highly dynamic videos is another key area. The current model struggles with videos containing significant motion changes, suggesting the need for improvements in how temporal information is encoded. This could involve incorporating concepts from video codecs or exploring alternative representations that better capture dynamic aspects. Evaluating CoordTok’s performance on diverse video datasets is essential to establish its robustness and generalizability. The study primarily focused on UCF-101, and expanding to other datasets representing different video styles, resolutions, and lengths will help validate the model’s broader applicability. Finally, integrating CoordTok with advanced video generation models beyond diffusion models will unlock new possibilities for creating high-quality long videos. Exploring other generative frameworks and examining the potential for improved video editing or manipulation are exciting possibilities. Overall, further research in these areas is key to unlocking CoordTok’s full potential and advancing the field of long-video processing.

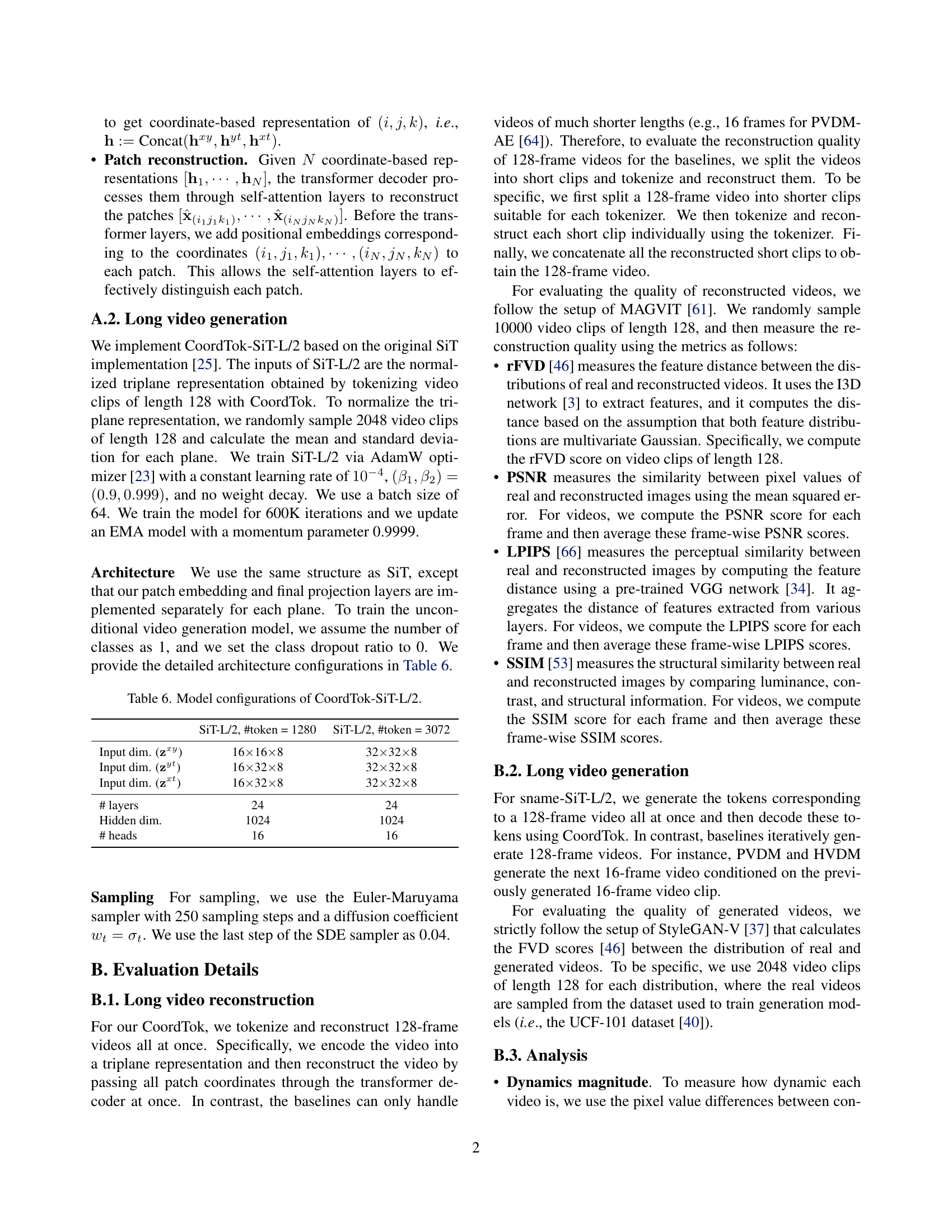

More visual insights#

More on figures

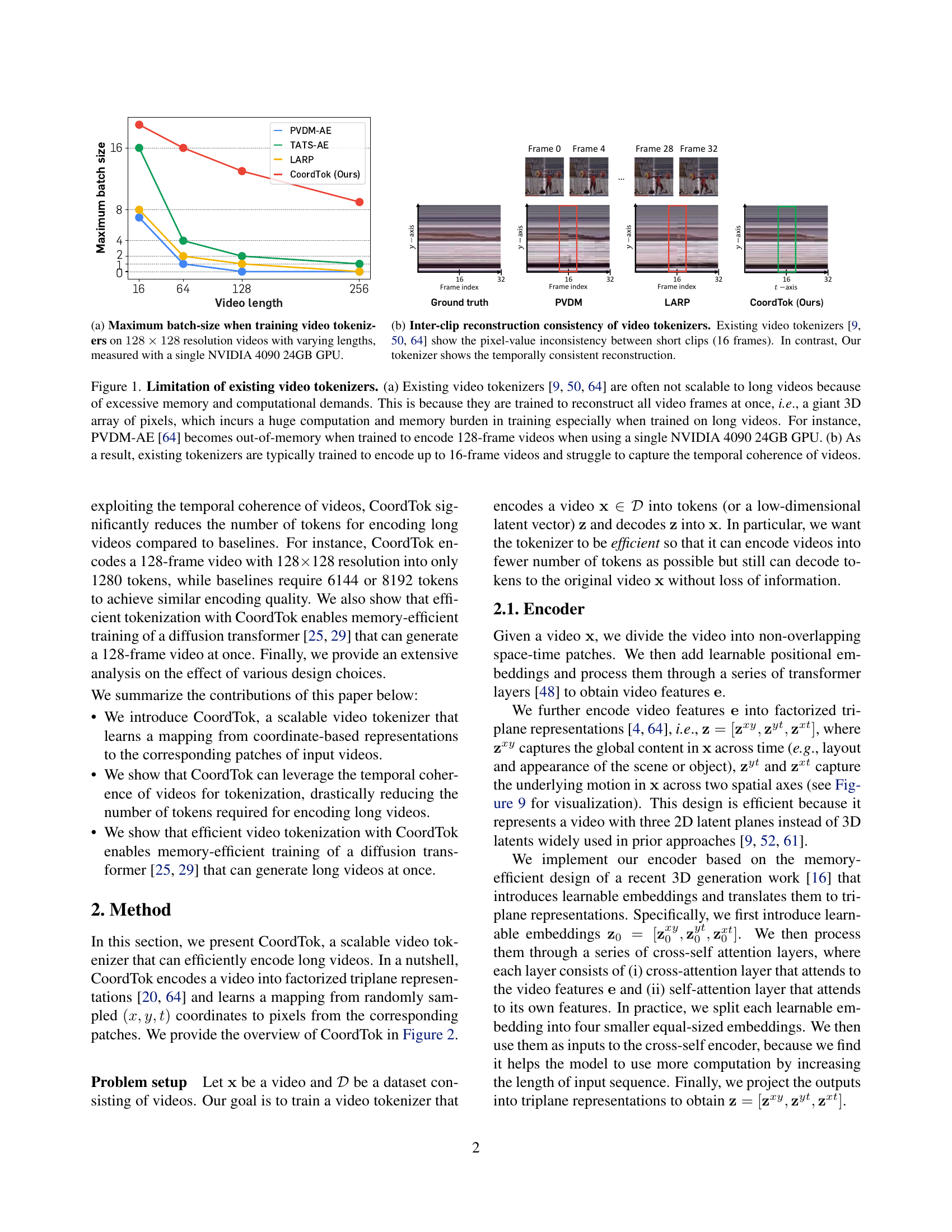

🔼 The figure (1b) demonstrates the temporal consistency of video reconstruction between short clips using CoordTok, in contrast to existing methods (PVDM, LARP) that exhibit pixel-value inconsistencies. This highlights CoordTok’s ability to leverage temporal coherence in videos, even when trained on longer sequences. The visualization shows reconstructed frames for a short video clip, comparing the reconstruction quality of CoordTok against other methods. Each method’s reconstruction is shown for four representative frames from the video sequence, illustrating a smoother and more consistent reconstruction from CoordTok in comparison to the other tokenizers.

read the caption

(b) Inter-clip reconstruction consistency of video tokenizers. Existing video tokenizers [9, 64, 50] show the pixel-value inconsistency between short clips (16 frames). In contrast, Our tokenizer shows the temporally consistent reconstruction.

🔼 Figure 1 illustrates the limitations of existing video tokenizers in handling long videos. Part (a) shows that training these models on long videos is computationally expensive and memory-intensive because they reconstruct all frames simultaneously. This is exemplified by PVDM-AE, which runs out of memory (on a single NVIDIA 4090 24GB GPU) when training on 128-frame videos. Part (b) demonstrates that this limitation restricts the training to shorter videos (up to 16 frames), hindering their ability to leverage the temporal coherence present in longer videos.

read the caption

Figure 1: Limitation of existing video tokenizers. (a) Existing video tokenizers [9, 64, 50] are often not scalable to long videos because of excessive memory and computational demands. This is because they are trained to reconstruct all video frames at once, i.e., a giant 3D array of pixels, which incurs a huge computation and memory burden in training especially when trained on long videos. For instance, PVDM-AE [64] becomes out-of-memory when trained to encode 128-frame videos when using a single NVIDIA 4090 24GB GPU. (b) As a result, existing tokenizers are typically trained to encode up to 16-frame videos and struggle to capture the temporal coherence of videos.

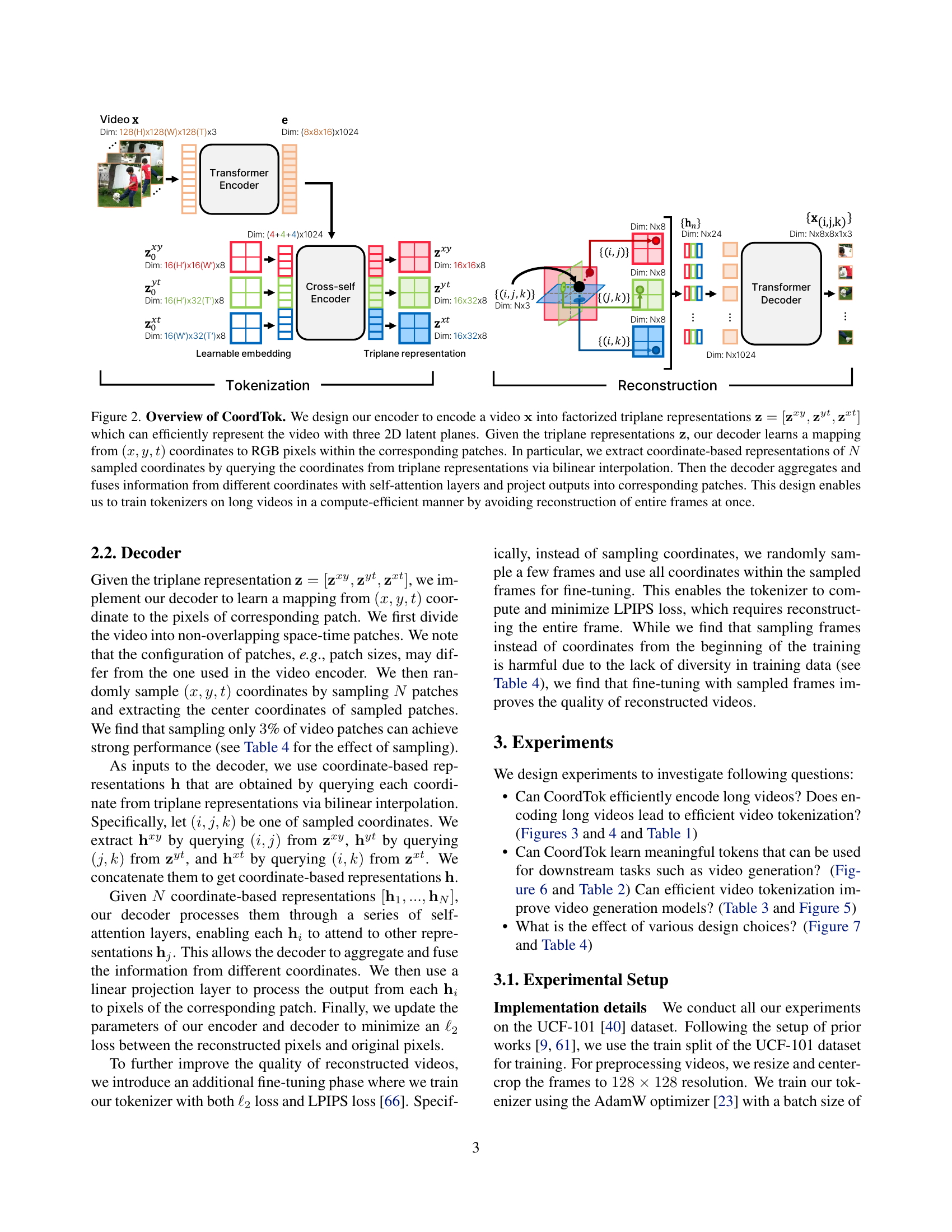

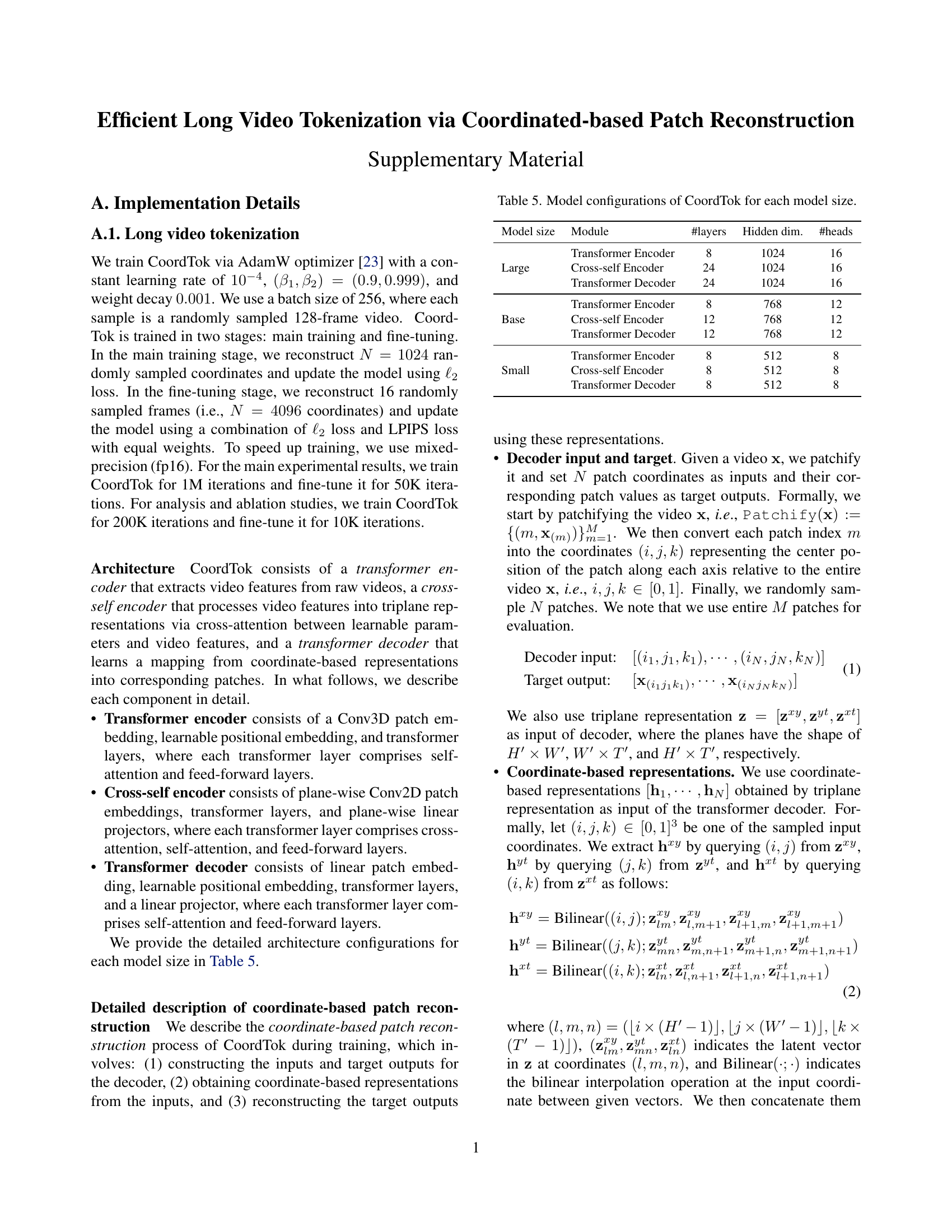

🔼 CoordTok processes videos by first encoding them into a compact triplane representation using a transformer encoder. This representation uses three 2D planes (zxy, zyt, zxt) to capture spatial and temporal information efficiently. The decoder then takes randomly sampled (x, y, t) coordinates as input and uses bilinear interpolation on the triplane representation to get feature vectors for these coordinates. These features are then processed by self-attention layers in the transformer decoder, which aggregate information across different coordinates. Finally, the decoder reconstructs the corresponding image patches. This approach avoids reconstructing full frames at once, enabling efficient training on long videos.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of CoordTok. We design our encoder to encode a video 𝐱𝐱{\mathbf{x}}bold_x into factorized triplane representations 𝐳=[𝐳xy,𝐳yt,𝐳xt]𝐳superscript𝐳𝑥𝑦superscript𝐳𝑦𝑡superscript𝐳𝑥𝑡{\mathbf{z}}=[{\mathbf{z}}^{xy},{\mathbf{z}}^{yt},{\mathbf{z}}^{xt}]bold_z = [ bold_z start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_x italic_y end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT , bold_z start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_y italic_t end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT , bold_z start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_x italic_t end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ] which can efficiently represent the video with three 2D latent planes. Given the triplane representations 𝐳𝐳\mathbf{z}bold_z, our decoder learns a mapping from (x,y,t)𝑥𝑦𝑡(x,y,t)( italic_x , italic_y , italic_t ) coordinates to RGB pixels within the corresponding patches. In particular, we extract coordinate-based representations of N𝑁Nitalic_N sampled coordinates by querying the coordinates from triplane representations via bilinear interpolation. Then the decoder aggregates and fuses information from different coordinates with self-attention layers and project outputs into corresponding patches. This design enables us to train tokenizers on long videos in a compute-efficient manner by avoiding reconstruction of entire frames at once.

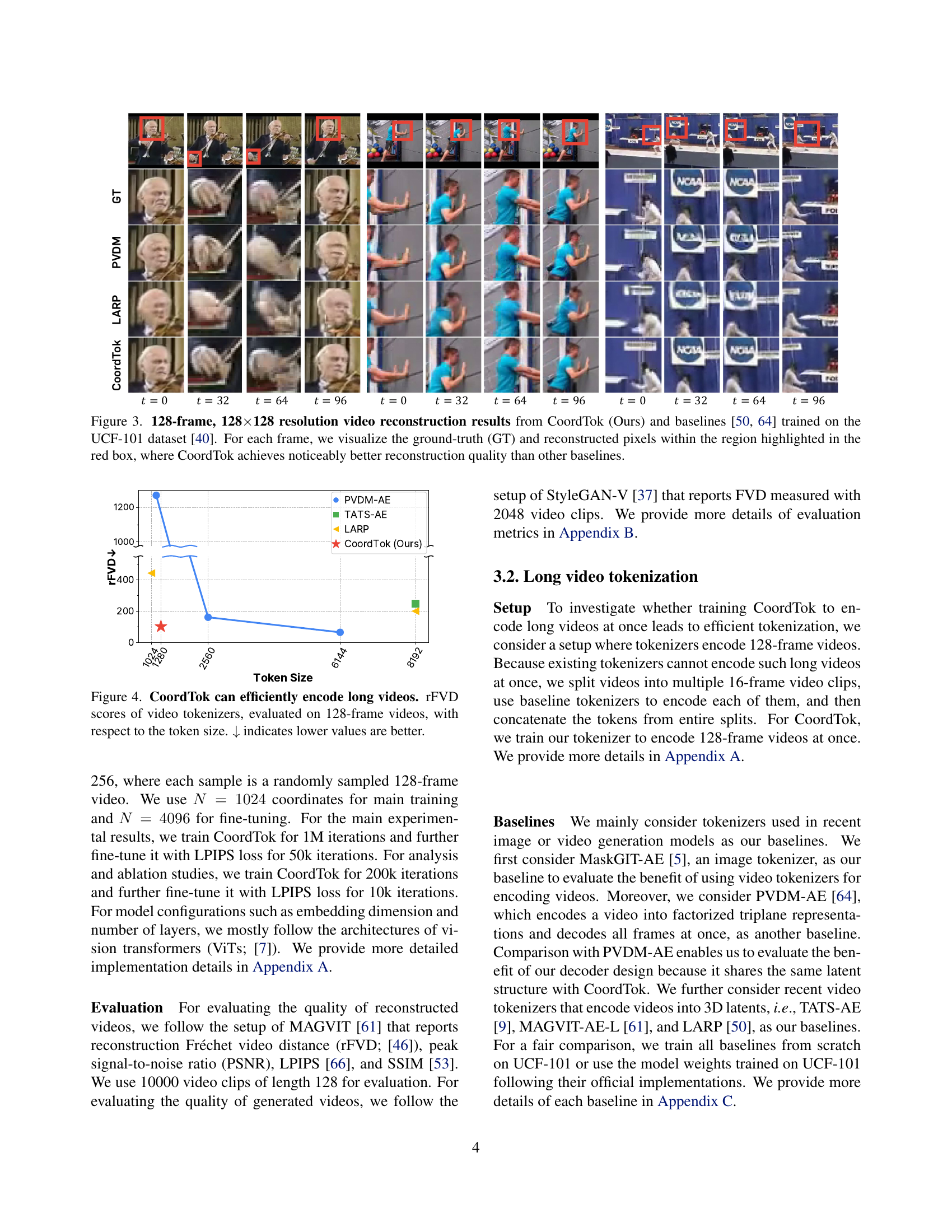

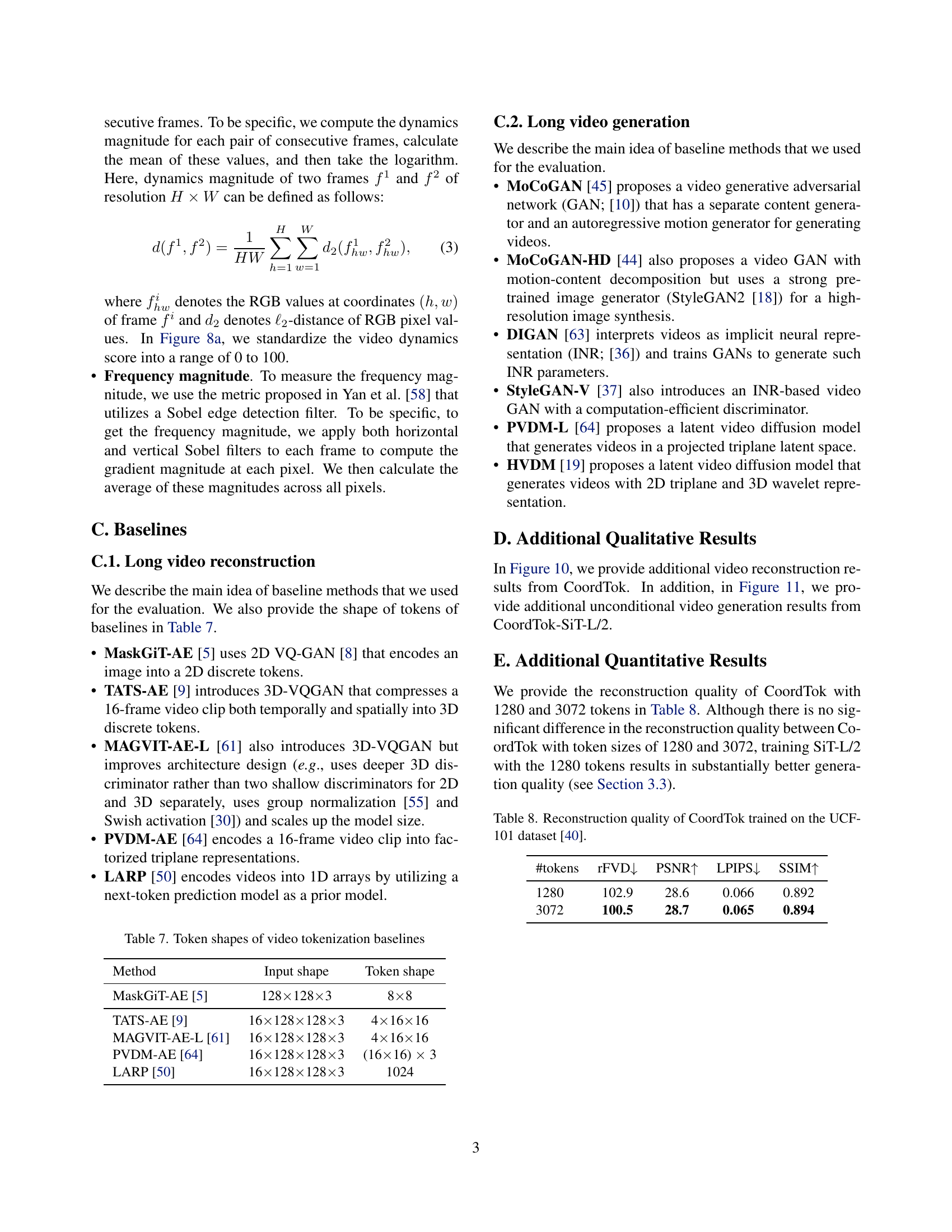

🔼 This figure compares the video reconstruction capabilities of CoordTok with two other state-of-the-art methods (PVDM-AE and LARP) on the UCF-101 dataset. It focuses on a 128-frame, 128x128 resolution video. A close-up of a specific area is shown for each method: the ground truth and each model’s reconstruction. This detailed comparison highlights CoordTok’s superior reconstruction quality in comparison to the baselines.

read the caption

Figure 3: 128-frame, 128×\times×128 resolution video reconstruction results from CoordTok (Ours) and baselines [64, 50] trained on the UCF-101 dataset [40]. For each frame, we visualize the ground-truth (GT) and reconstructed pixels within the region highlighted in the red box, where CoordTok achieves noticeably better reconstruction quality than other baselines.

🔼 Figure 4 illustrates the efficiency of CoordTok in encoding long videos. It compares CoordTok to several baseline video tokenizers by measuring their reconstruction quality (rFVD) in relation to the number of tokens used to encode 128-frame videos. The graph shows that CoordTok requires significantly fewer tokens to achieve a comparable rFVD score, indicating superior compression efficiency for long videos.

read the caption

Figure 4: CoordTok can efficiently encode long videos. rFVD scores of video tokenizers, evaluated on 128-frame videos, with respect to the token size. ↓↓\downarrow↓ indicates lower values are better.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of efficient video tokenization on video generation quality. Two SiT-L/2 models were trained using CoordTok, a novel video tokenizer. One model used 1280 tokens per video, while the other used 3072. The Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) metric, lower values indicating better generation quality, was used to assess the generated videos. The results show that the model trained with fewer tokens (1280) achieved significantly better video generation quality, highlighting CoordTok’s effectiveness in reducing computational requirements without sacrificing performance.

read the caption

Figure 5: Efficient video tokenization improves video generation. We report FVDs of SiT-L/2 models trained upon CoordTok with token sizes of 1280 and 3072. ↓↓\downarrow↓ indicates lower values are better.

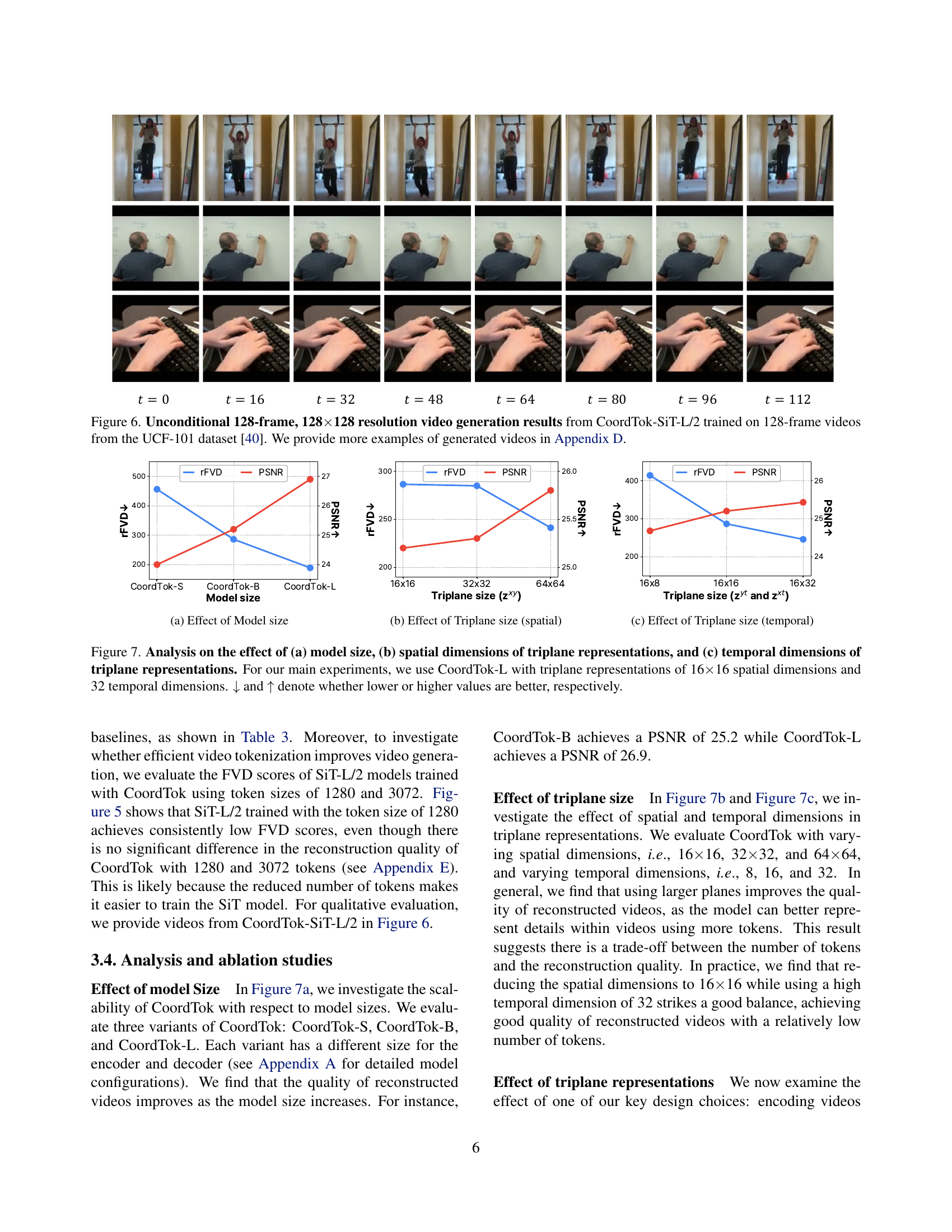

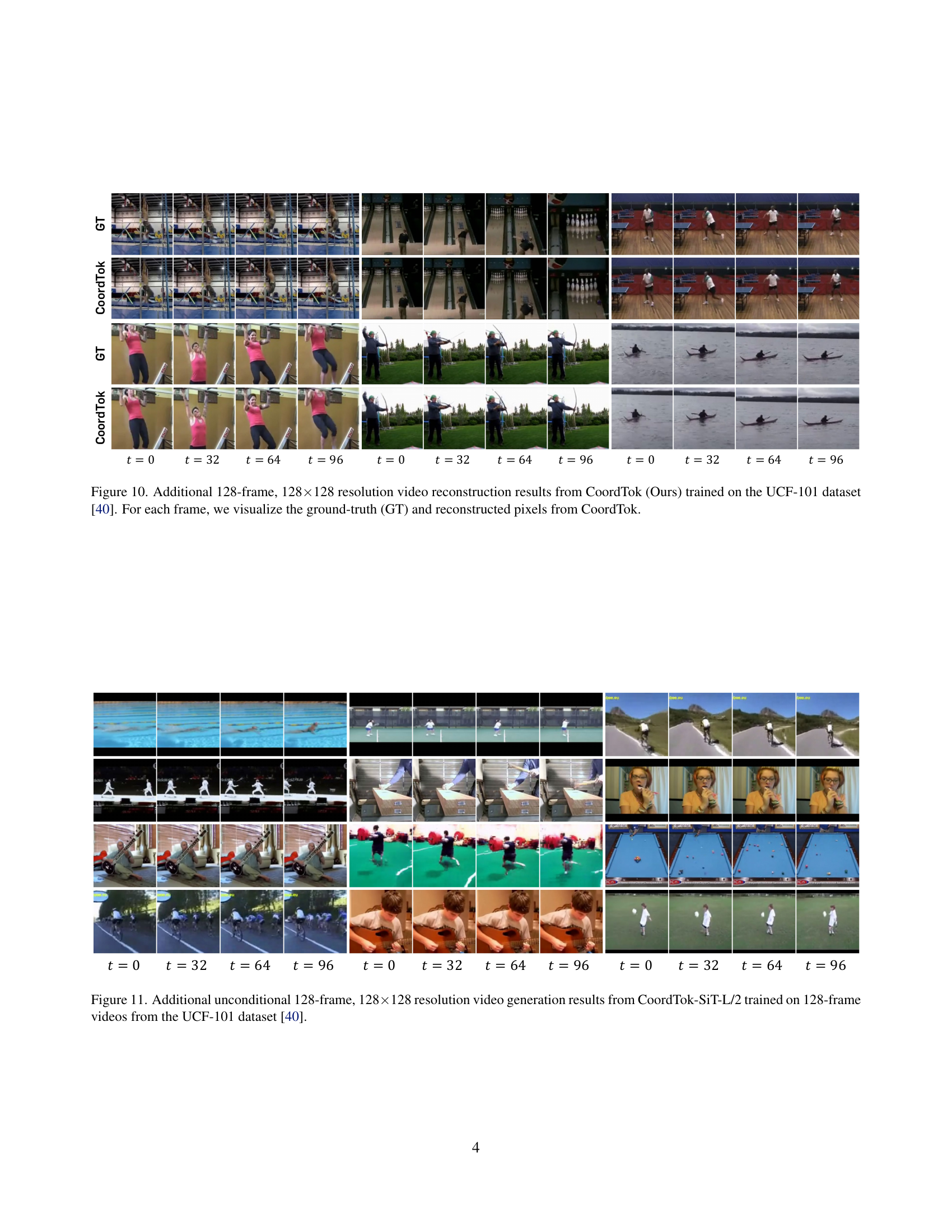

🔼 This figure showcases the results of unconditional video generation using the CoordTok-SiT-L/2 model. The model was trained on 128-frame video clips from the UCF-101 dataset. The figure displays sample frames from a generated video, demonstrating the model’s ability to produce coherent and visually plausible long video sequences. Additional examples are provided in Appendix D.

read the caption

Figure 6: Unconditional 128-frame, 128×\times×128 resolution video generation results from CoordTok-SiT-L/2 trained on 128-frame videos from the UCF-101 dataset [40]. We provide more examples of generated videos in Appendix D.

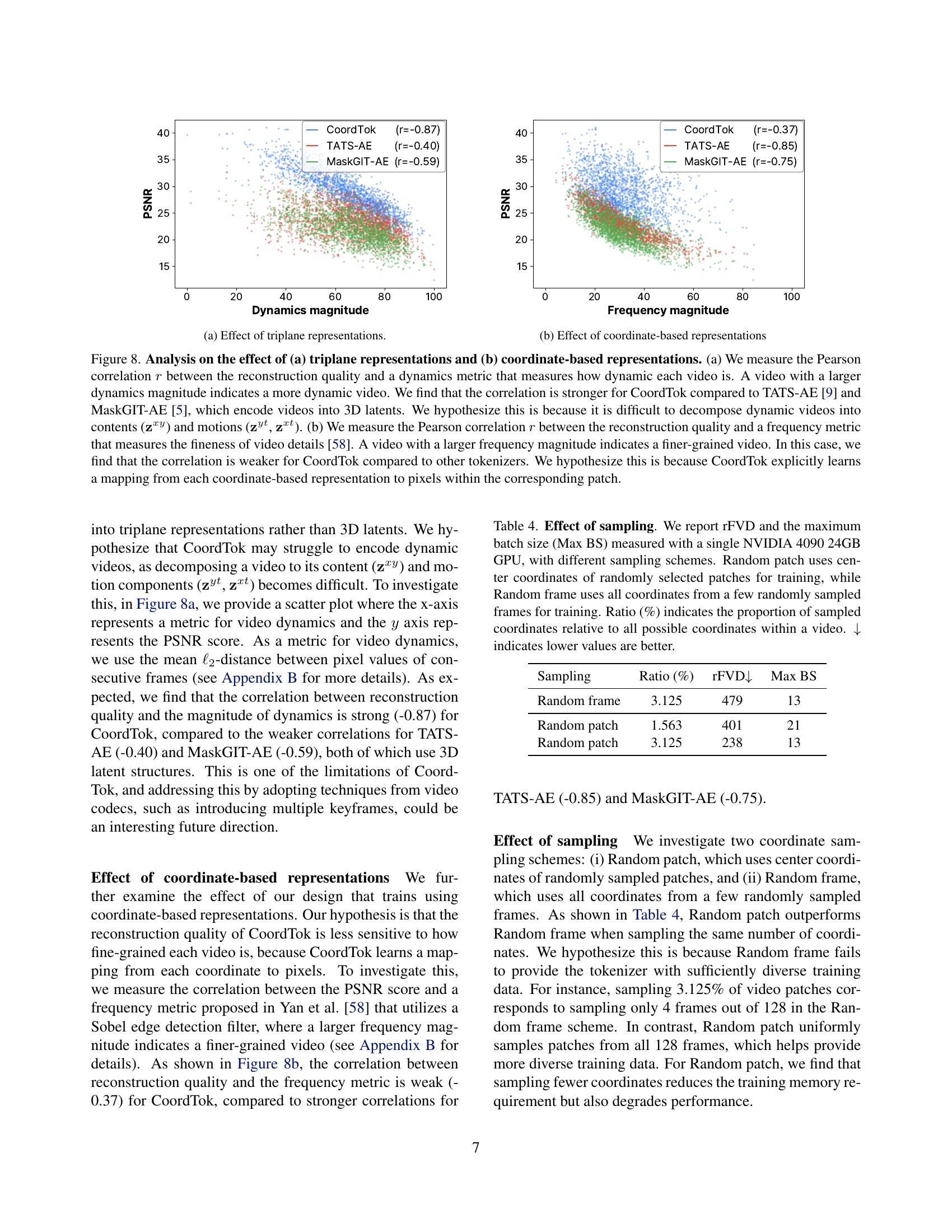

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of varying model sizes on the performance of CoordTok. The x-axis represents different model sizes (small, base, large). The y-axis displays two metrics: rFVD (reconstruction Fréchet video distance, lower is better) and PSNR (peak signal-to-noise ratio, higher is better). By comparing the rFVD and PSNR values across different model sizes, we can see how model capacity influences the quality of video reconstruction.

read the caption

(a) Effect of Model size

🔼 This figure shows the impact of altering the spatial dimensions of the triplane representations within the CoordTok model on the reconstruction quality of videos. It assesses how changing the size of the spatial dimensions (e.g., 16x16, 32x32, 64x64 pixels) within the triplane representations (zxy, zyt, zxt) affects the resulting PSNR and rFVD (Fréchet Video Distance) scores. Larger spatial dimensions generally lead to better reconstruction quality but could potentially increase computational cost.

read the caption

(b) Effect of Triplane size (spatial)

🔼 This figure shows the effect of varying the temporal dimension of the triplane representations in CoordTok on video reconstruction quality. The x-axis represents different temporal sizes (e.g., 16x8, 16x16, 16x32), while the y-axis shows the reconstruction quality measured by rFVD (lower is better) and PSNR (higher is better). It demonstrates how the model’s performance changes with different choices for temporal dimension, highlighting the optimal settings for balancing performance and efficiency.

read the caption

(c) Effect of Triplane size (temporal)

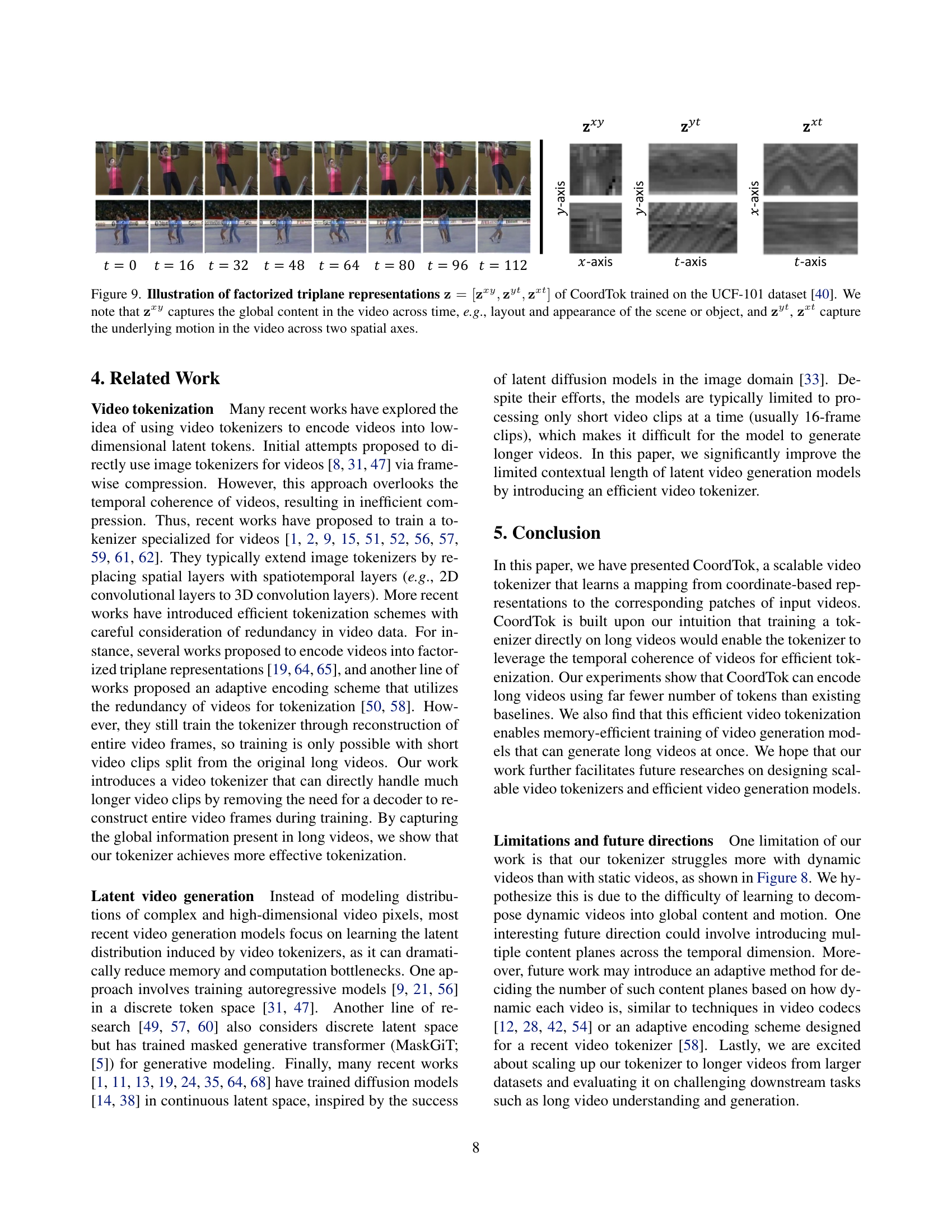

🔼 Figure 7 presents a comprehensive analysis of the impact of different design choices on CoordTok’s performance. Specifically, it explores the effect of (a) varying model size (CoordTok-S, CoordTok-B, CoordTok-L), (b) adjusting the spatial dimensions of the triplane representations (16x16, 32x32, 64x64), and (c) modifying the temporal dimensions of the triplane representations (8, 16, 32). Each subfigure displays the relationship between a performance metric (rFVD and PSNR) and the specific design choice, enabling visualization of how modifications impact reconstruction quality. The main experiments in the paper utilized CoordTok-L with 16x16 spatial and 32 temporal dimensions. Arrows indicate whether lower or higher values on the y-axis are preferable for each metric.

read the caption

Figure 7: Analysis on the effect of (a) model size, (b) spatial dimensions of triplane representations, and (c) temporal dimensions of triplane representations. For our main experiments, we use CoordTok-L with triplane representations of 16×\times×16 spatial dimensions and 32 temporal dimensions. ↓↓\downarrow↓ and ↑↑\uparrow↑ denote whether lower or higher values are better, respectively.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of the triplane representation on the quality of video reconstruction. The x-axis represents a video dynamics metric which measures how much the video changes frame to frame. The y-axis shows the PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) of the video reconstruction. The figure compares the correlation between dynamics and reconstruction quality for CoordTok and two baseline models (TATS-AE and MaskGIT-AE). A strong negative correlation indicates that the model is better at reconstructing less dynamic videos. CoordTok shows a stronger negative correlation than the baselines, suggesting it handles dynamic videos better.

read the caption

(a) Effect of triplane representations.

🔼 This figure shows the correlation between the reconstruction quality (PSNR) and the frequency of video details. The frequency magnitude, calculated using a Sobel edge detection filter, represents the fineness of video details. A higher frequency magnitude indicates finer details. The figure demonstrates that CoordTok’s reconstruction quality is less sensitive to the frequency magnitude compared to baselines. This suggests CoordTok is less affected by the level of detail in the video because it learns a mapping directly from coordinates to pixels, rather than relying on the overall features of the video.

read the caption

(b) Effect of coordinate-based representations

Full paper#