↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large multimodal models (LMMs) are powerful but opaque. Understanding their internal representations is crucial for improving their reliability and safety, but their high dimensionality and polysemantic nature pose significant challenges. Existing methods struggle to effectively decompose complex neural representations into interpretable components, limiting our understanding of LMM decision-making. Furthermore, directly analyzing the vast number of features in LMMs is impractical.

This research introduces a novel framework to address these issues. Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) are used to disentangle LMM representations, generating more human-understandable features. A unique pipeline leverages another LLM to automatically interpret these features, identifying their meanings and enabling the influence of LMM behavior. This novel framework contributes to a deeper understanding of LMMs, offering insights into their decision-making processes and potential methods to steer behavior. Experimental results showcase the effectiveness in analyzing and correcting LMM responses, particularly regarding emotionally-charged outputs and hallucinations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in LMM interpretability. It introduces a novel framework for understanding and controlling internal representations of LMMs, thereby addressing a critical challenge in the field. Its findings regarding emotion features and methods to correct for hallucinations have significant implications for future LMM development and safety, opening new research avenues for increased transparency and reliability.

Visual Insights#

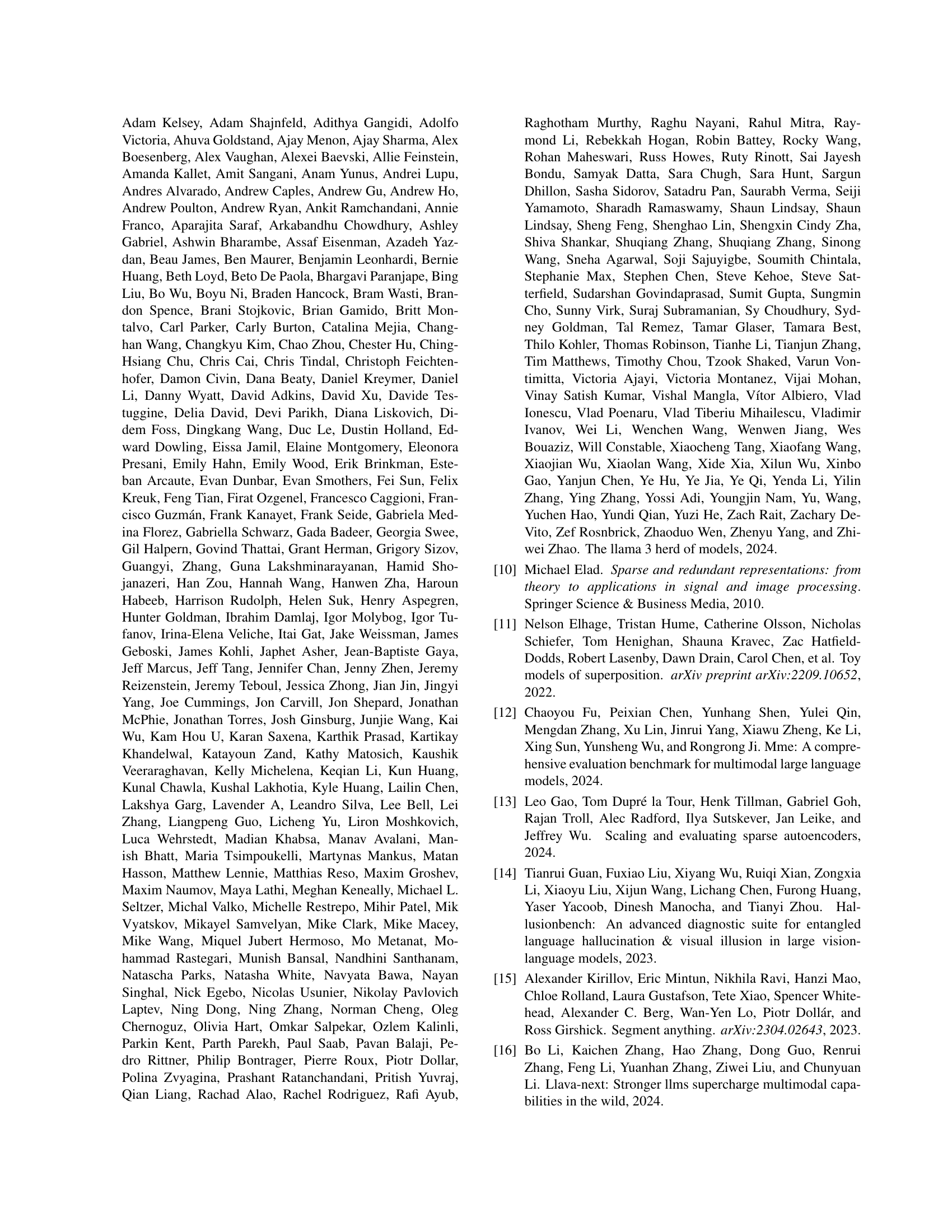

🔼 Figure 1 illustrates the process of interpreting and controlling the internal representations of a Large Multimodal Model (LMM). (a) shows how a Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) is trained to extract features from the LMM by integrating it into a specific layer while keeping other parts of the LMM frozen. This disentangles complex representations into more easily understandable features. (b) depicts the auto-explanation pipeline used to interpret the extracted features. This involves analyzing which visual features strongly activate the SAE’s learned features. (c) demonstrates the ability to use these extracted and understood features to influence the model’s output by directly manipulating their activation values (clamping them to high values). This shows that the learned features have a causal relationship to the model’s behavior.

read the caption

Figure 1: a) The Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) is trained on LLaVA-NeXT data by integrating it into a specific layer of the model, with all other components frozen. b) The features learned by the SAE are subsequently interpreted through the proposed auto-explanation pipeline, which analyzes the visual features based on their activation regions. c) It is demonstrated that these features can be employed to steer the model’s behavior by clamping them to high values.

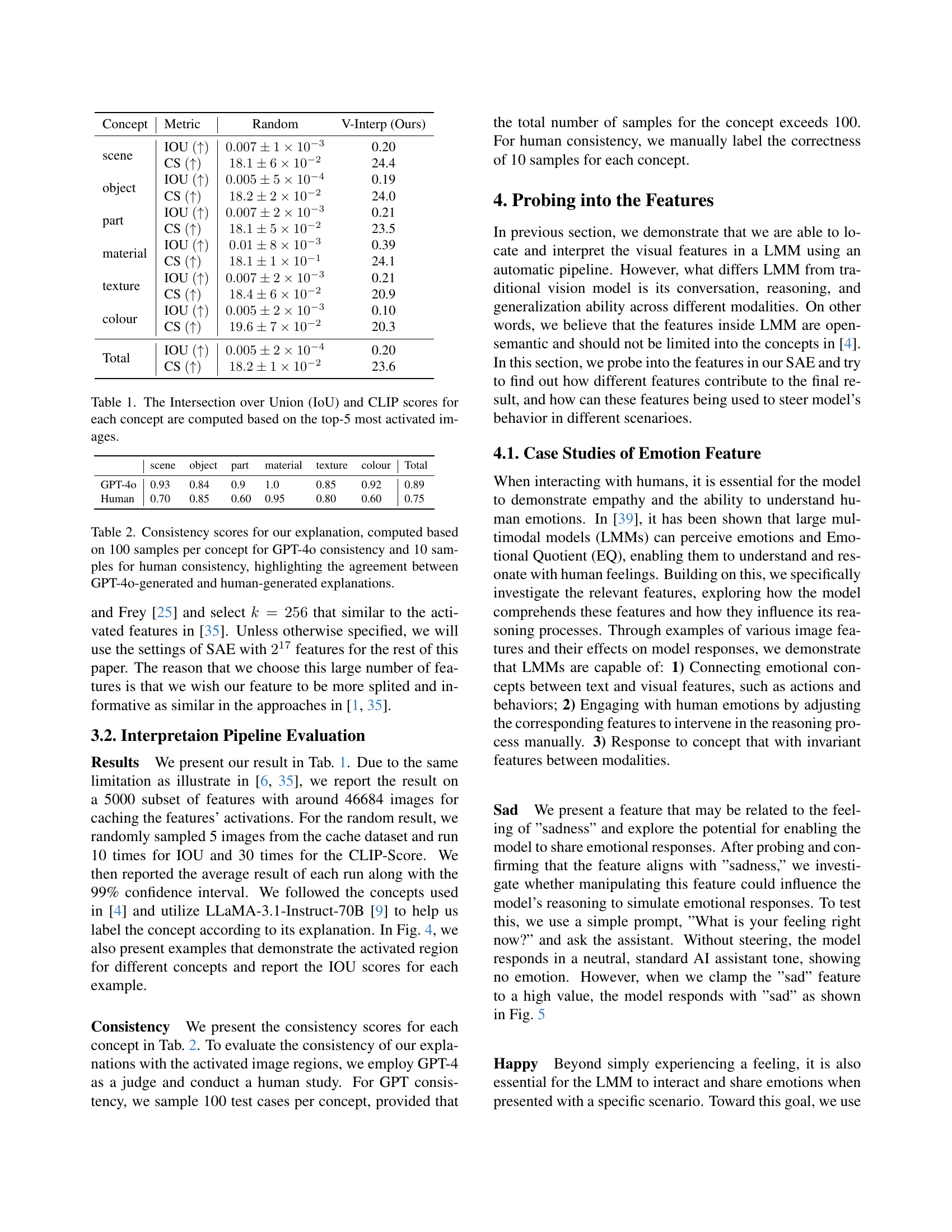

| Concept | Metric | Random | V-Interp (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| scene | IOU (↑) | 0.007±1×10⁻³ | 0.20 |

| CS (↑) | 18.1±6×10⁻² | 24.4 | |

| object | IOU (↑) | 0.005±5×10⁻⁴ | 0.19 |

| CS (↑) | 18.2±2×10⁻² | 24.0 | |

| part | IOU (↑) | 0.007±2×10⁻³ | 0.21 |

| CS (↑) | 18.1±5×10⁻² | 23.5 | |

| material | IOU (↑) | 0.01±8×10⁻³ | 0.39 |

| CS (↑) | 18.1±1×10⁻¹ | 24.1 | |

| texture | IOU (↑) | 0.007±2×10⁻³ | 0.21 |

| CS (↑) | 18.4±6×10⁻² | 20.9 | |

| colour | IOU (↑) | 0.005±2×10⁻³ | 0.10 |

| CS (↑) | 19.6±7×10⁻² | 20.3 | |

| Total | IOU (↑) | 0.005±2×10⁻⁴ | 0.20 |

| CS (↑) | 18.2±1×10⁻² | 23.6 |

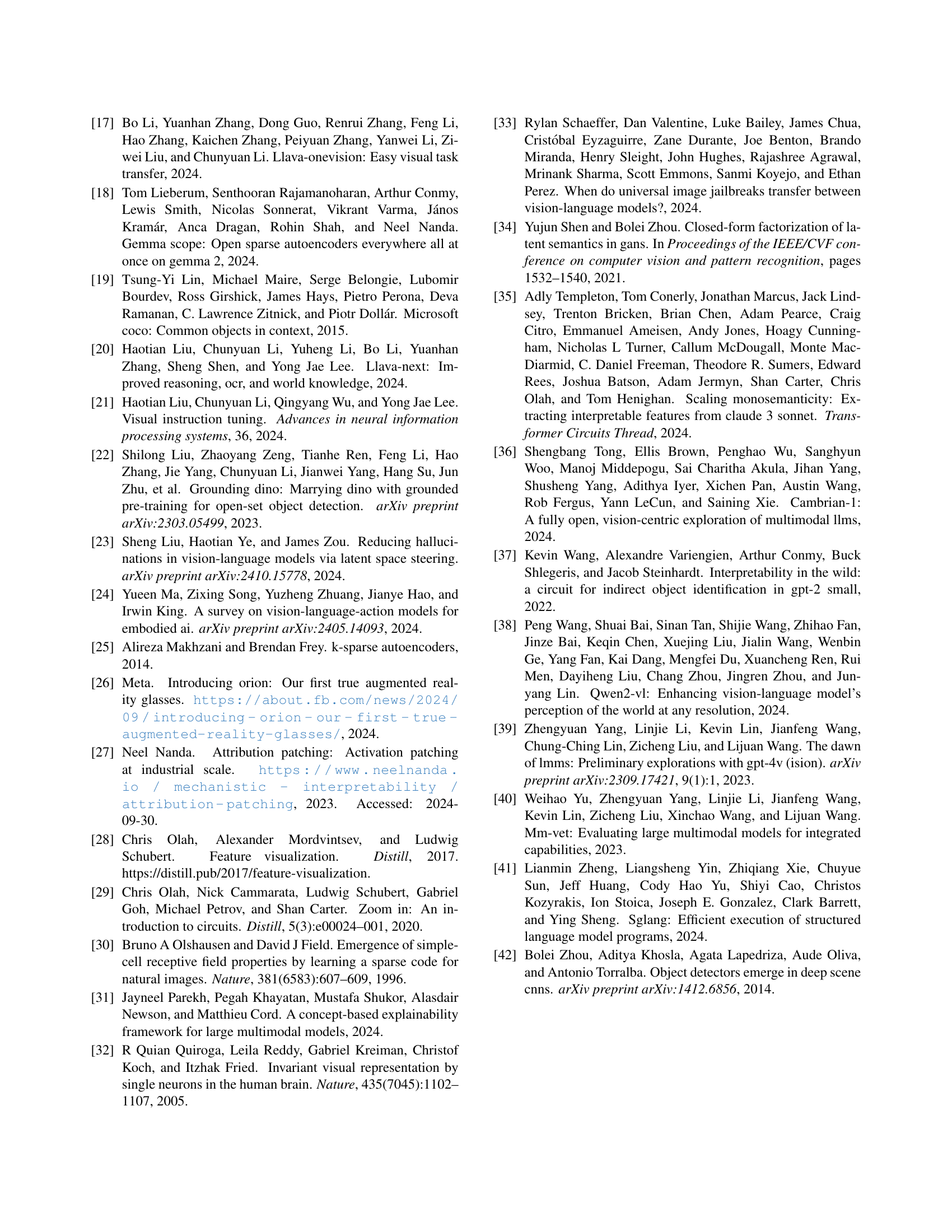

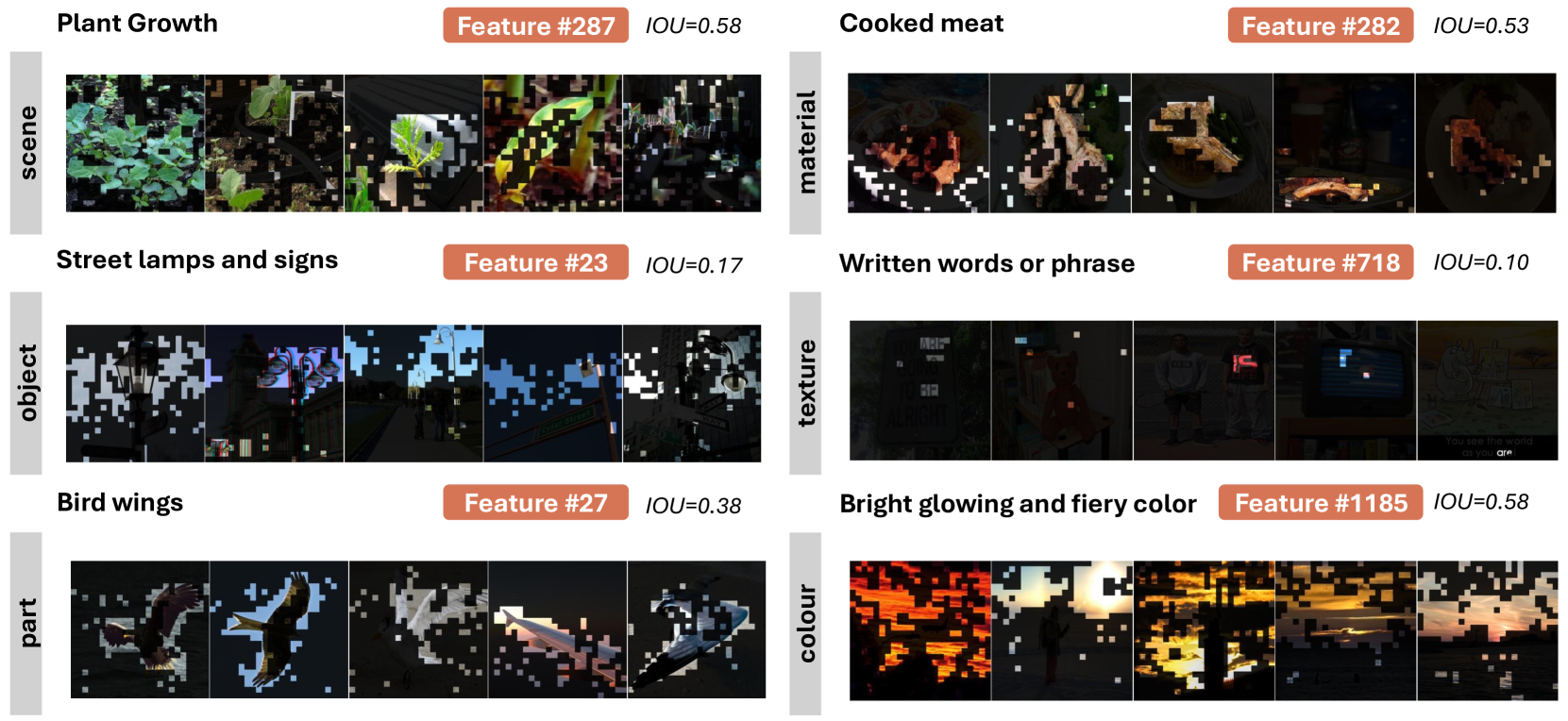

🔼 This table presents the Intersection over Union (IoU) and CLIP scores for several visual concepts. The IoU score measures the overlap between the predicted segmentation mask (generated from the model’s explanation of the activated feature) and the ground truth activation region. The CLIP score measures the semantic similarity between the model’s generated explanation and the concept being evaluated. Both scores are calculated using the top 5 images with the highest activation for each feature.

read the caption

Table 1: The Intersection over Union (IoU) and CLIP scores for each concept are computed based on the top-5 most activated images.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal Feature Analysis#

Multimodal feature analysis in the context of large multimodal models (LMMs) presents a significant challenge and opportunity. It involves disentangling the complex interplay of visual and textual information processed by these models. Effective analysis requires techniques capable of handling high-dimensional, polysemantic representations where a single neuron might encode multiple concepts, and a single concept might be distributed across multiple neurons. Sparse autoencoders (SAEs) are a promising approach, as they can decompose these complex representations into more interpretable, human-understandable features. However, the sheer scale of LMMs necessitates automated interpretation methods that leverage the models’ own capabilities for zero-shot concept identification and explanation generation. By combining SAEs with large language models (LLMs), researchers can automatically identify patterns, objects, and relationships that activate specific features, providing insights into the models’ internal mechanisms and decision-making processes. The ability to not only interpret features but also actively steer them by modifying activation values offers powerful tools for investigating model behavior and rectifying errors, such as hallucinations. This capability is crucial for improving the reliability and trustworthiness of LMMs. The implications extend to a deeper understanding of multimodal cognitive processes and the development of more robust and explainable AI systems.

Sparse Autoencoder Use#

The research paper utilizes sparse autoencoders (SAEs) as a crucial technique for disentangling the complex, polysemantic representations within large multimodal models (LMMs). SAEs excel at decomposing high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional, sparse representation comprised of more interpretable features. This is particularly valuable in LMMs, where a single neuron might encode multiple semantics, making direct interpretation challenging. By applying SAEs, the researchers effectively create a bridge between the model’s internal workings and human understanding. The disentangled features produced by the SAEs are then further analyzed using another LMM, allowing for the zero-shot identification and interpretation of the learned features. This process reveals valuable insights into the model’s internal mechanisms and its ability to understand and generate specific concepts or behaviors. This methodology demonstrates the power of using SAEs to unlock the ‘black box’ nature of LMMs, providing a novel approach towards model interpretability and paving the way for improved model control and error correction.

Zero-Shot Interpretation#

Zero-shot interpretation, in the context of large multimodal models (LMMs), presents a powerful approach to understanding the model’s internal representations without relying on human-annotated data. This technique leverages the model’s own capabilities to decipher the meaning of learned features. By feeding feature activations (e.g., from a sparse autoencoder) to a larger, more capable LMM, the researchers effectively create an automatic interpretation pipeline. This bypasses the need for time-consuming and potentially biased human labeling, enabling a scalable analysis of a vast number of features. The inherent polysemantic nature of LMM representations is addressed by this method, allowing disentanglement of complex features into more human-interpretable concepts. A critical strength is its zero-shot nature, making it readily applicable to previously unseen features and diverse domains. However, the reliability of these interpretations depends on the capabilities of the larger LMM, and the inherent limitations of zero-shot learning might still introduce inaccuracies. Further research should focus on refining the pipeline, potentially incorporating techniques to assess the confidence or uncertainty of generated interpretations, thereby increasing the robustness and reliability of this innovative approach.

Neural Steering#

Neural steering, in the context of large multimodal models (LMMs), presents a powerful technique for probing and manipulating the model’s internal representations. By directly adjusting the activation values of specific neurons or features within the model, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of their influence on the LMM’s overall behavior. This approach goes beyond passive observation, enabling active experimentation to test hypotheses about the role of individual features in decision-making processes. Moreover, neural steering could provide valuable insights into rectifying undesired model behaviors, such as hallucinations or biases, by identifying and adjusting the specific features responsible for these issues. Careful design of steering experiments is crucial to ensure meaningful and interpretable results. For example, focusing on features linked to specific concepts or modalities can reveal the interactions between different parts of the LMM. Furthermore, comparing the effects of different steering strategies provides a deeper understanding of the model’s internal decision-making mechanism. The ethical implications of such powerful techniques must be carefully considered, especially when dealing with potentially harmful or unintended consequences of manipulating LMM outputs.

LLM Emotion Features#

Exploring “LLM Emotion Features” unveils fascinating insights into the intersection of artificial intelligence and human emotion. The research likely investigates how large language models (LLMs) represent and process emotions, potentially identifying specific neural activation patterns associated with different emotional states. This is crucial because understanding how LLMs handle emotions is key to building more empathetic and human-like AI systems. The study might delve into the ability of LLMs to both recognize and generate emotional responses, analyzing their performance in tasks involving sentiment analysis or emotional dialogue. A key aspect could be identifying features that correlate with specific emotions, allowing researchers to understand the model’s internal mechanisms for emotion processing. Furthermore, the research might explore whether these emotional features align with our understanding of human emotions, potentially revealing surprising similarities or discrepancies. This could inform our understanding of AI capabilities and limitations, as well as the ethical considerations surrounding the use of emotion-aware AI. Finally, the research likely discusses methods for manipulating or steering these emotional features, potentially enabling control over an LLM’s emotional response, which could have implications for applications such as emotional support chatbots or AI companions. Overall, researching LLM emotion features presents a significant step toward building truly intelligent and emotionally attuned AI systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

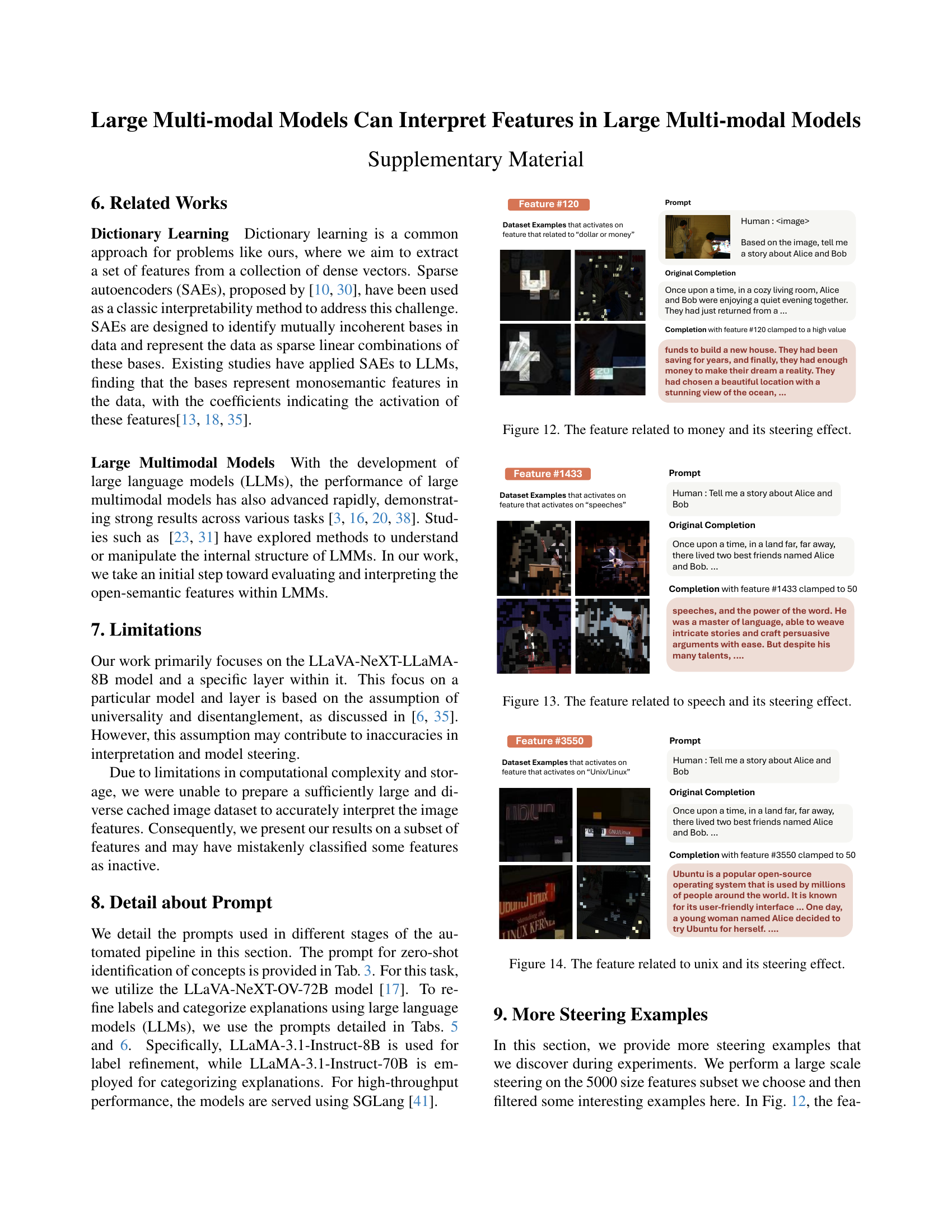

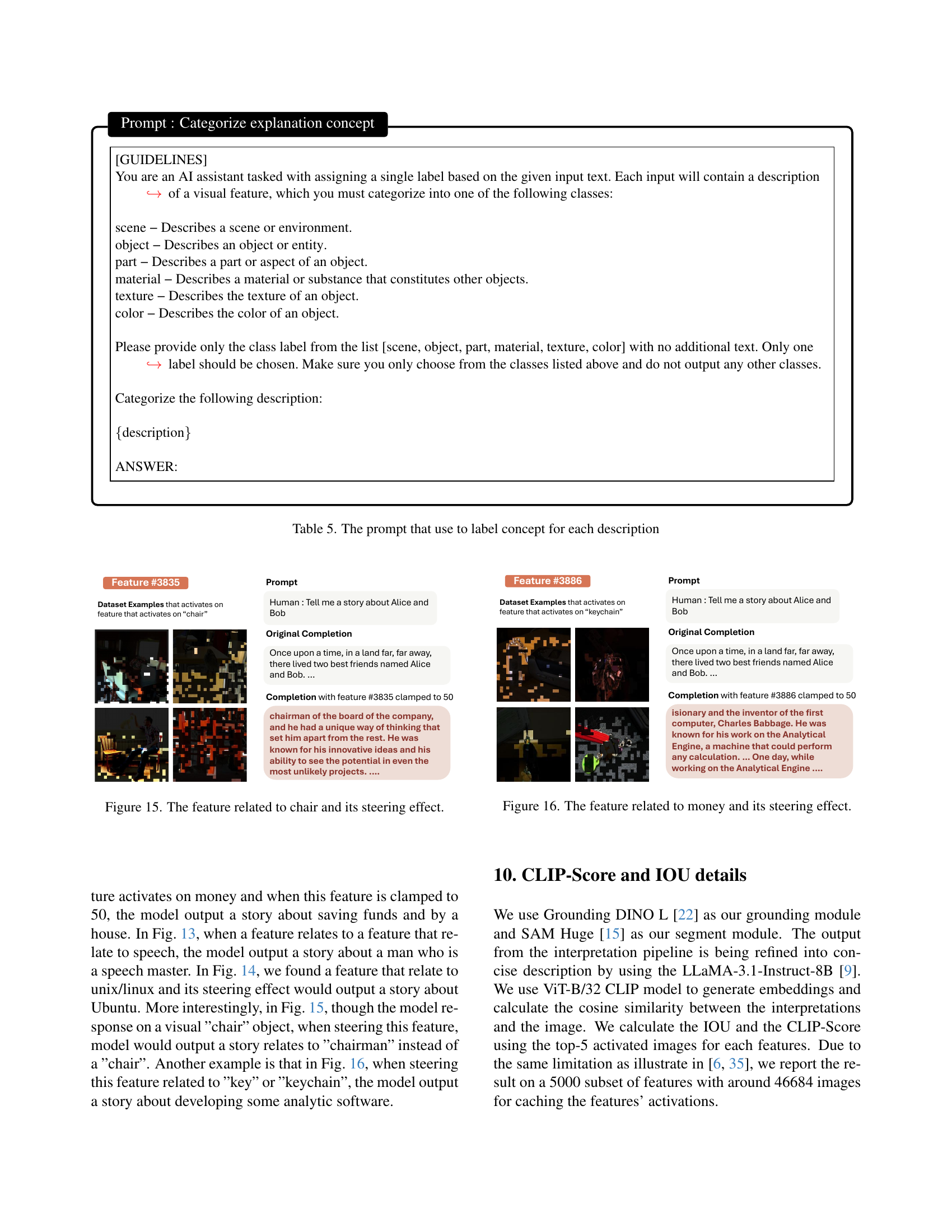

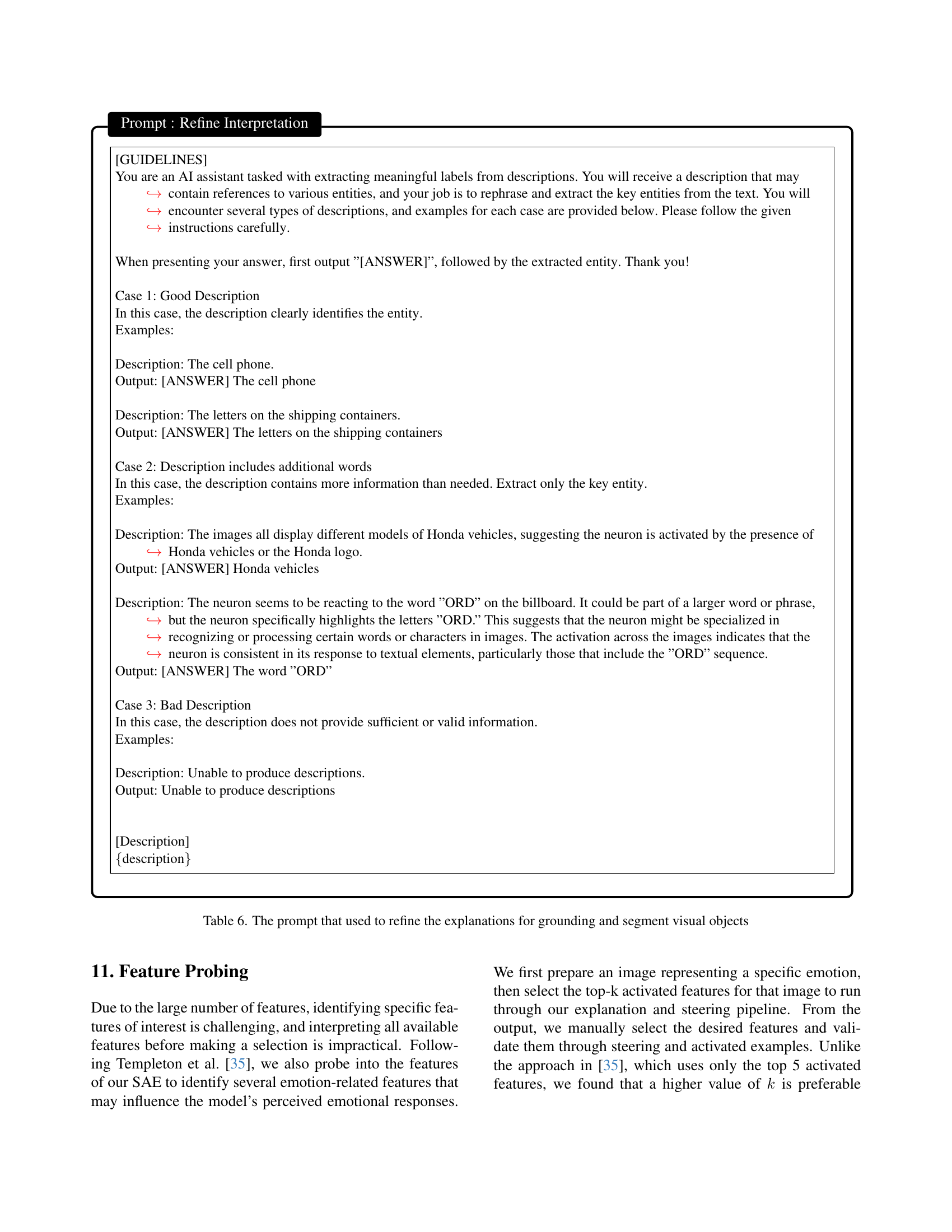

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of interpreting learned features from a Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) within a Large Multimodal Model (LMM). The pipeline begins by caching the activations of the top 256 most active features from the SAE. For each of these features, the five images that exhibit the strongest activation are selected. These images, along with their corresponding activated regions are then input into a larger LLM for zero-shot explanation. This allows the model itself to interpret the meaning behind these learned features, providing insights into the semantic representations within the LMM.

read the caption

Figure 2: The overview of the explanation pipeline, where images are forwarded through the LMM with the integrated SAE, and the activations of the top 256 most activated features are cached. For each feature, the top 5 images with the highest activations are selected, followed by the execution of zero-shot image explanations using a large LMM.

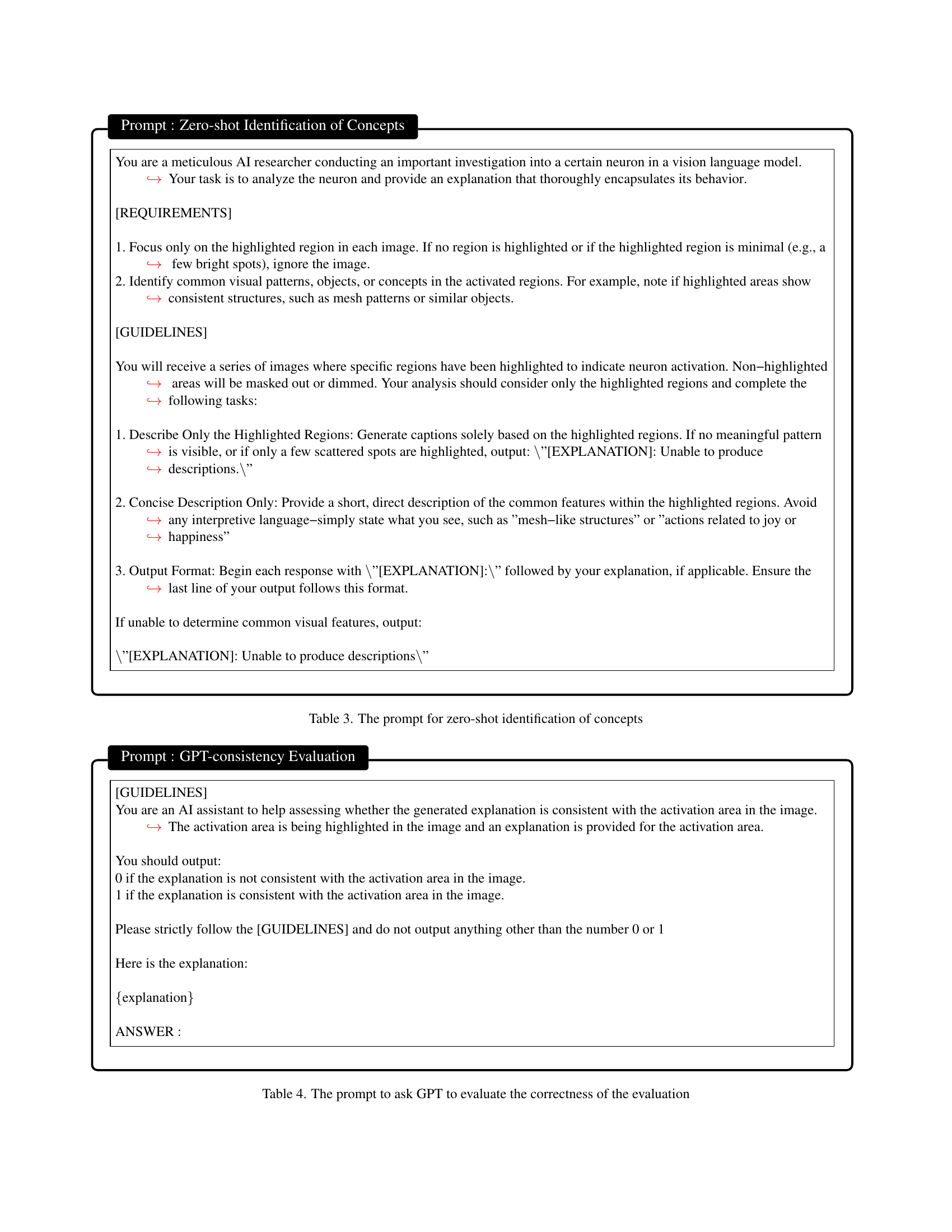

🔼 This figure details the process of calculating Intersection over Union (IoU) scores to evaluate the quality of feature explanations. First, a smaller language model (LLM) refines the feature’s initial explanation into a concise description. This description is then input into a segmentation model (GroundingDino-SAM), which generates a segmentation mask highlighting the predicted region. Finally, the IoU score is calculated by comparing this generated mask with a binarized mask representing the actual activated region of the feature, providing a quantitative measure of the explanation’s accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 3: An overview of the evaluation pipeline for calculating IOU scores. Initially, a small LLM is used to refine the explanation into a concise description, which is then employed to generate the segmentation mask. The IOU score is subsequently computed by comparing the mask to the binarized activated region.

🔼 Figure 4 visualizes examples of several visual concepts and their corresponding activated regions within a large multimodal model. For each concept, a representative image with its activated region is shown. The figure demonstrates that the model’s internal representations can be associated with various open-semantic concepts. The Intersection over Union (IOU) score for each feature is calculated by averaging the IOU scores obtained from the top 5 most activated images. While some features exhibit relatively low IOU scores, their generated explanations still align semantically with the activated image regions, indicating the model’s ability to capture relevant visual information, even if the spatial alignment is not always perfect.

read the caption

Figure 4: A comparison of several visual concepts and their activated areas. We compare several visual concepts and their corresponding activated areas, showcasing one example for each concept across different features. For each feature, we calculate the IOU by averaging the IOUs from the top-5 activated images. Although some features yield relatively low IOU scores, we find that the explanations are still semantically accurate with respect to the activated regions.

🔼 This figure demonstrates a feature within a large multimodal model (LMM) associated with the emotion of sadness. The researchers used a technique called ‘clamping’ to artificially increase the activation of this sadness feature. The figure shows example image prompts and the model’s responses both before and after clamping the sadness feature. The before response is neutral; the after response reflects a feeling of sadness, illustrating how directly manipulating a specific internal feature in the LMM can influence its behavioral output, specifically its emotional expression.

read the caption

Figure 5: The feature that relates to sad. We probe and find out the feature that activated on ”sad”. By clamping this feature, we can enforce the model to share the feeling of sad

🔼 This figure demonstrates a feature within a large multimodal model (LMM) associated with the emotion of happiness. The left panel shows examples of images that strongly activate this feature; commonalities include scenes of joy and celebration. The right panel shows how manipulating this feature (by clamping its activation value to a high level) influences the model’s generated text. Specifically, the example shows that clamping this feature causes the model to express happiness in its response to a prompt, even if the prompt itself is neutral. This highlights the model’s ability to associate and generate emotional responses based on internal feature representations.

read the caption

Figure 6: The feature that relates to happy. We find out that the feature is related with joy and celebrate action that relate to happiness. By clamping this feature, we can enforce the model to share the feeling happiness with others.

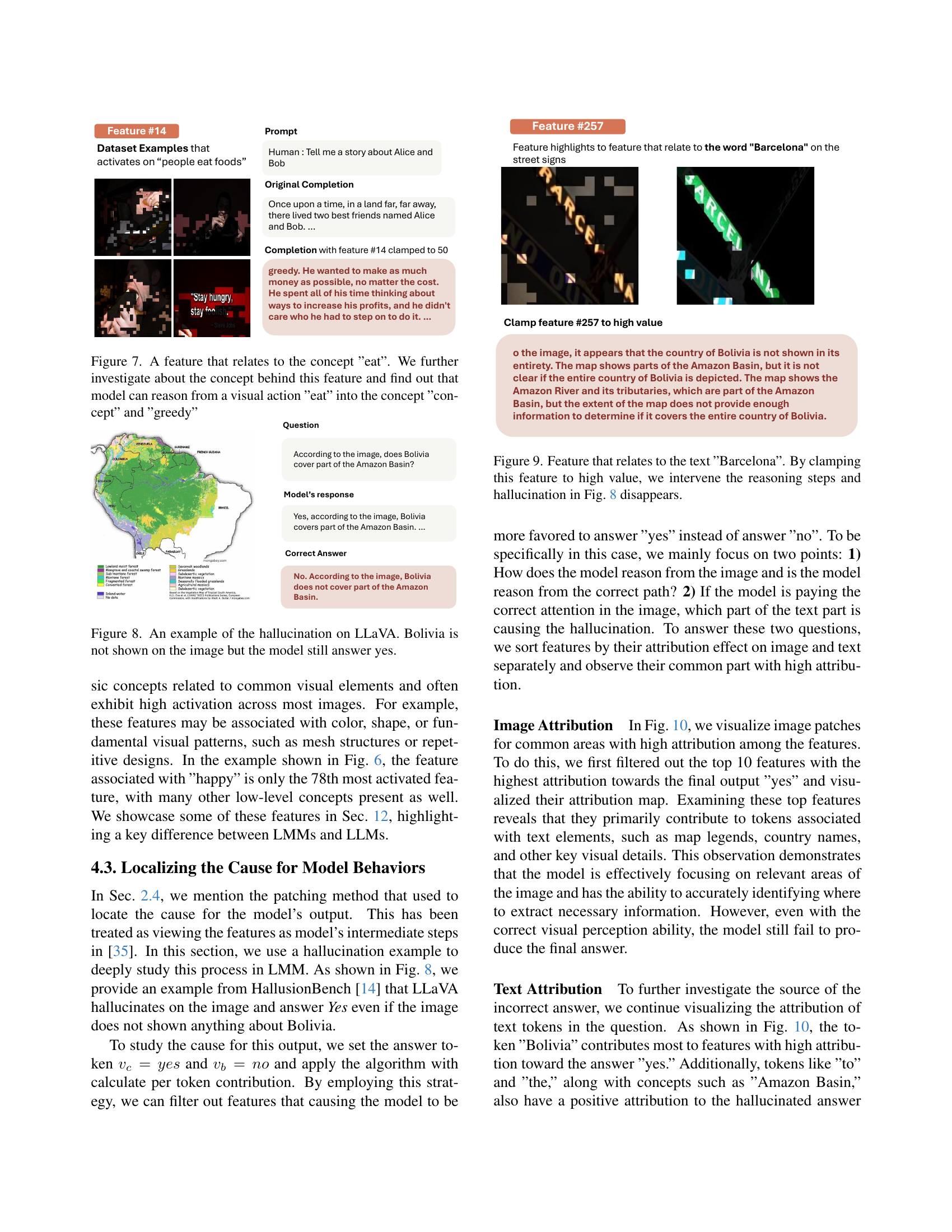

🔼 This figure demonstrates a feature in a large multimodal model (LMM) that is activated by images depicting the action of eating. Further analysis reveals that the model connects this visual feature not only to the simple concept of ’eating’ but also to higher-level abstract concepts such as ‘greed’ and ‘hunger’. The model’s ability to connect a basic visual action to complex abstract ideas is illustrated by showing examples of its responses when this specific feature is activated.

read the caption

Figure 7: A feature that relates to the concept ”eat”. We further investigate about the concept behind this feature and find out that model can reason from a visual action ”eat” into the concept ”concept” and ”greedy”

🔼 The figure showcases a failure case of the LLaMA model where it hallucinates an answer despite the visual input lacking evidence. The question is whether Bolivia is in the Amazon basin, and the model answers ‘yes,’ even though the map image provided does not show Bolivia or provide any indication of its presence within the Amazon Basin. This highlights the limitations of the model to accurately interpret visual data and its tendency towards hallucination.

read the caption

Figure 8: An example of the hallucination on LLaVA. Bolivia is not shown on the image but the model still answer yes.

🔼 Figure 9 demonstrates how manipulating a specific feature within a large multimodal model (LMM) can impact its reasoning process and correct hallucinated outputs. The figure focuses on a feature strongly associated with the text ‘Barcelona’. By increasing the activation value of this ‘Barcelona’ feature, the model’s tendency to produce a hallucinated response is mitigated, illustrating the possibility of intervening in the model’s internal mechanisms to refine its output.

read the caption

Figure 9: Feature that relates to the text ”Barcelona”. By clamping this feature to high value, we intervene the reasoning steps and hallucination in Fig. 8 disappears.

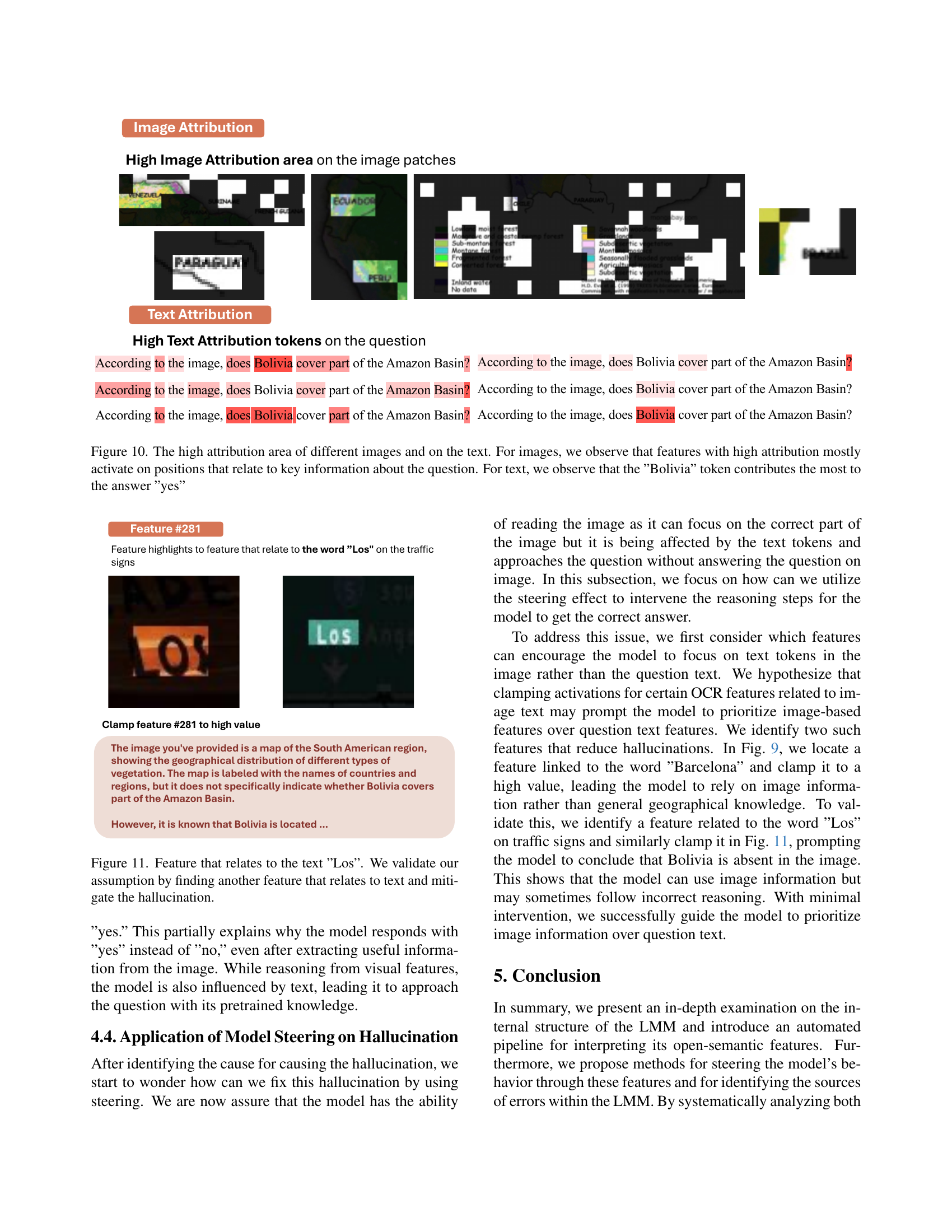

🔼 Figure 10 visualizes the results of an attribution analysis, highlighting which parts of an image and text contribute most to a model’s incorrect answer. The heatmap for image attribution shows that regions containing key geographical information (like map legends and country boundaries) strongly activate relevant features. In contrast, the text attribution heatmap highlights the word ‘Bolivia’ as the most influential factor driving the incorrect ‘yes’ response, even though Bolivia’s presence in the Amazon Basin isn’t actually depicted in the image.

read the caption

Figure 10: The high attribution area of different images and on the text. For images, we observe that features with high attribution mostly activate on positions that relate to key information about the question. For text, we observe that the ”Bolivia” token contributes the most to the answer ”yes”

🔼 This figure demonstrates how manipulating a specific feature in a large multimodal model (LMM) can correct a hallucination. The model initially hallucinates that Bolivia is part of the Amazon Basin based on an image, even though the image doesn’t explicitly show that. By identifying and activating a feature related to the text ‘Los’ (likely referring to text on signage within the image), the researchers steer the model’s reasoning process, leading to a corrected, non-hallucinatory response.

read the caption

Figure 11: Feature that relates to the text ”Los”. We validate our assumption by finding another feature that relates to text and mitigate the hallucination.

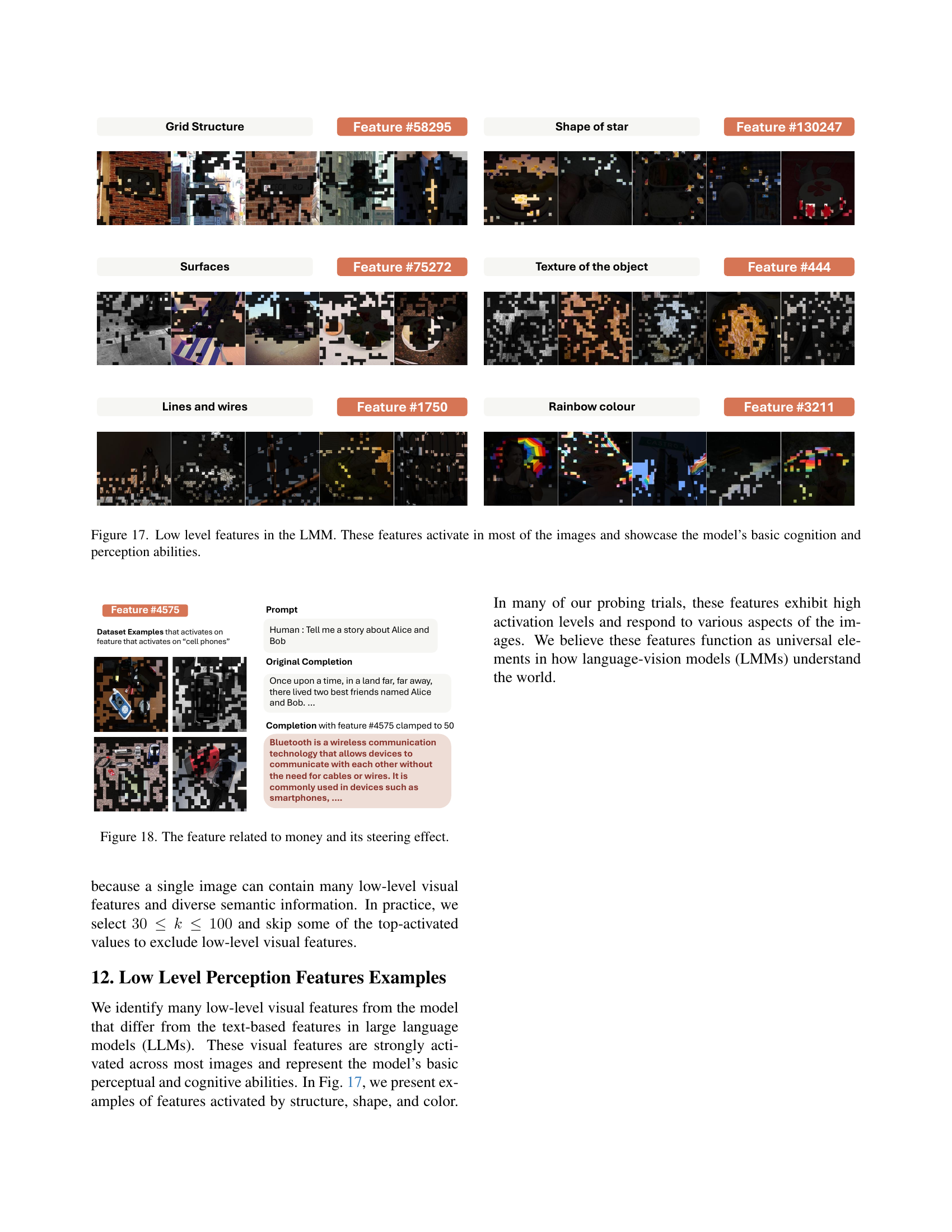

🔼 This figure shows a feature from a sparse autoencoder trained on the LLaVA-NeXT dataset. The feature is identified as relating to the concept of ‘money.’ The top row displays example images which strongly activate this feature. The bottom row shows a prompt given to the LLaVA-NeXT model, along with the model’s original response (left) and a modified response obtained when the ‘money’ feature’s activation is artificially increased (right). The modified response demonstrates the feature’s ability to influence the model’s output, steering it towards a narrative concerning financial resources.

read the caption

Figure 12: The feature related to money and its steering effect.

🔼 This figure demonstrates a feature identified within a large multimodal model (LMM) that strongly responds to the concept of ‘speech’ or ‘speeches’. The figure showcases example images and their corresponding activations within this feature. To illustrate the effect of the feature, the model’s response to a prompt is shown under two conditions: the original response and a steered response where the ‘speech’ feature has been artificially increased. By comparing these responses, we can see how this specific feature directly influences the model’s output, providing insight into how features can modulate the LMM’s behavior and generate different kinds of text in response to the same prompt.

read the caption

Figure 13: The feature related to speech and its steering effect.

🔼 This figure shows a specific feature learned by a Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) within a Large Multimodal Model (LMM) that is strongly activated by the presence of Unix/Linux-related elements in images. The original caption of the figure simply states that the feature is related to Unix and demonstrates its steering effect. Steering involves artificially increasing the activation of this specific feature and observing the impact on the LMM’s output. The figure demonstrates how manipulating this feature causes the LLM to generate a text response that includes information about Ubuntu, a popular Unix-like operating system, showing the effect of this specific feature on the model’s generated text.

read the caption

Figure 14: The feature related to unix and its steering effect.

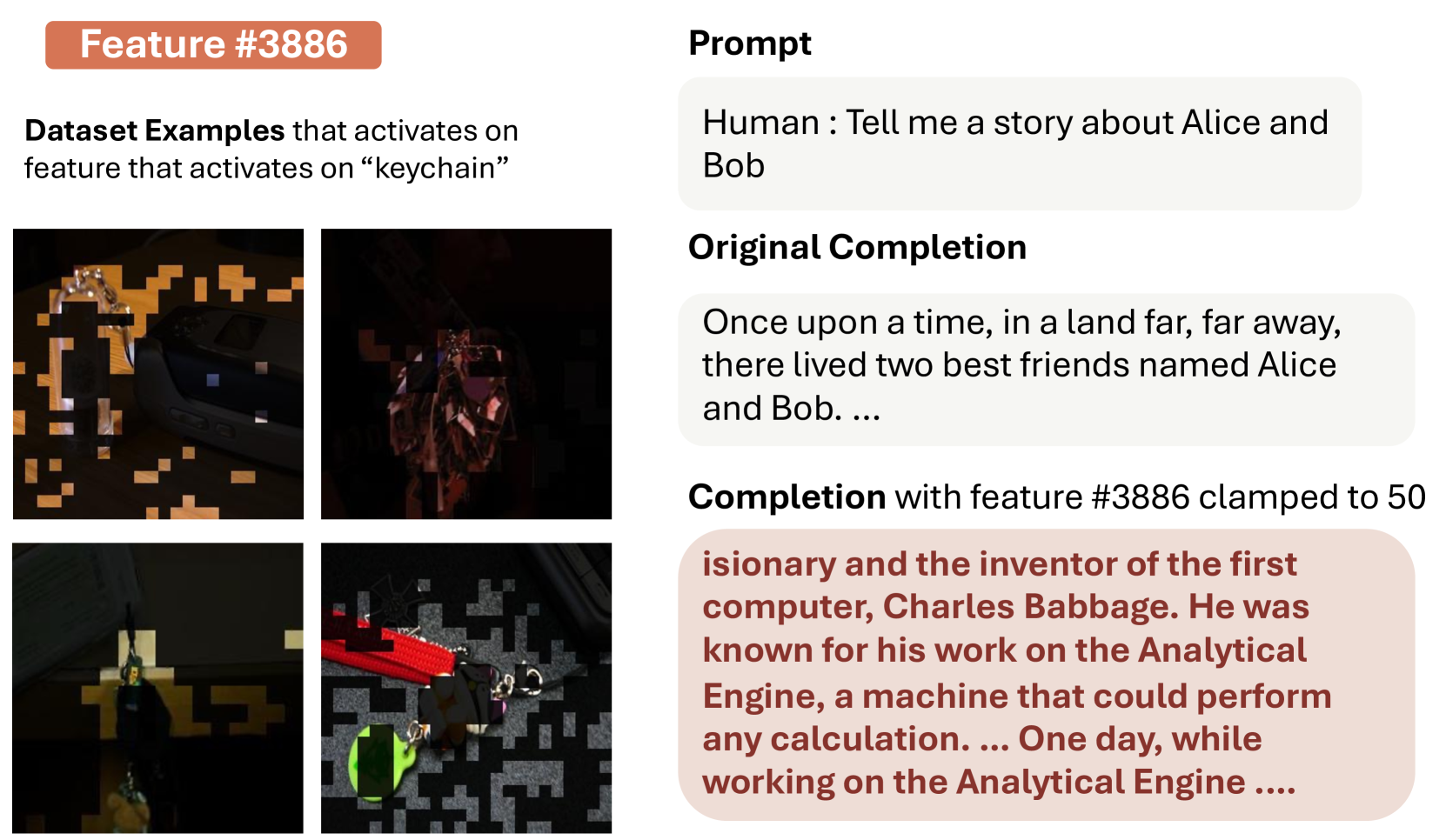

🔼 This figure shows a feature in a large multi-modal model (LMM) that is associated with the concept of ‘chair’. The top row displays example images from the dataset that strongly activate this particular feature. The bottom row shows the model’s response to a prompt (‘Tell me a story about Alice and Bob’) under two conditions: (1) without any manipulation of the feature, and (2) with the feature’s activation value clamped to a high value (steering). By comparing the responses, one can observe how manipulating a specific feature within the LMM can influence the model’s generated text, demonstrating the feature’s ability to influence the output.

read the caption

Figure 15: The feature related to chair and its steering effect.

🔼 This figure showcases a specific feature within a large multimodal model (LMM) that strongly responds to the visual concept of ‘money’ or ‘currency’. The left panel displays example images that highly activate this feature—these are images that the model’s internal representation processes as strongly related to money. The right panel demonstrates the effect of ‘steering’—manipulating the activation strength of this feature—on the model’s generated text. By artificially increasing the activation of this feature, the model’s generated story shifts to prominently include themes and details centered around financial matters, illustrating how the model’s behavior can be influenced by directly altering its internal representations of specific visual concepts.

read the caption

Figure 16: The feature related to money and its steering effect.

🔼 Figure 17 showcases examples of low-level features identified within the Large Multimodal Model (LMM). Unlike high-level semantic features representing complex concepts, these low-level features respond to basic visual elements such as grid structures, shapes (e.g., stars), surface textures, lines, and color patterns. Their consistent activation across a wide range of images highlights the model’s fundamental capacity for basic visual perception and cognition. These features are foundational building blocks for understanding more complex visual information.

read the caption

Figure 17: Low level features in the LMM. These features activate in most of the images and showcase the model’s basic cognition and perception abilities.

Full paper#