TL;DR#

The shift towards ARM architecture presents a significant challenge due to the extensive legacy x86 software ecosystem and the lack of efficient, accurate translation methods between different instruction set architectures (ISAs). Existing virtualization methods introduce performance overhead, and direct recompilation is not always feasible. This paper introduces a novel solution to this problem: a lightweight language model (LLM)-based transpiler called CRT.

CRT utilizes the power of LLMs to learn the mapping between x86 and ARM/RISC-V assembly instructions. The model is trained on a large dataset of paired assembly codes and then used to automatically translate x86 code to ARM/RISC-V equivalents. CRT achieves high translation accuracy (79.25% for ARMv5 and 88.68% for RISC-V) and demonstrates significant performance improvements (1.73x speedup, 1.47x energy efficiency, and 2.41x memory efficiency) compared to existing methods. The study also evaluates the impact of various model parameters and quantization techniques on the transpiler’s efficiency and performance. The research successfully navigates the CISC/RISC divide, generating correct and efficient RISC code and demonstrating potential for significant improvements in software migration and compatibility.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to solving a significant challenge in the field of computer architecture: the efficient and accurate translation of assembly code between different instruction set architectures (ISAs). This is especially relevant given the increasing industry adoption of ARM-based systems and the need to migrate legacy x86 software. The method developed, a language-model based approach, presents a unique solution that overcomes limitations of current virtualization approaches while providing valuable insights for researchers in machine learning and compiler optimization.

Visual Insights#

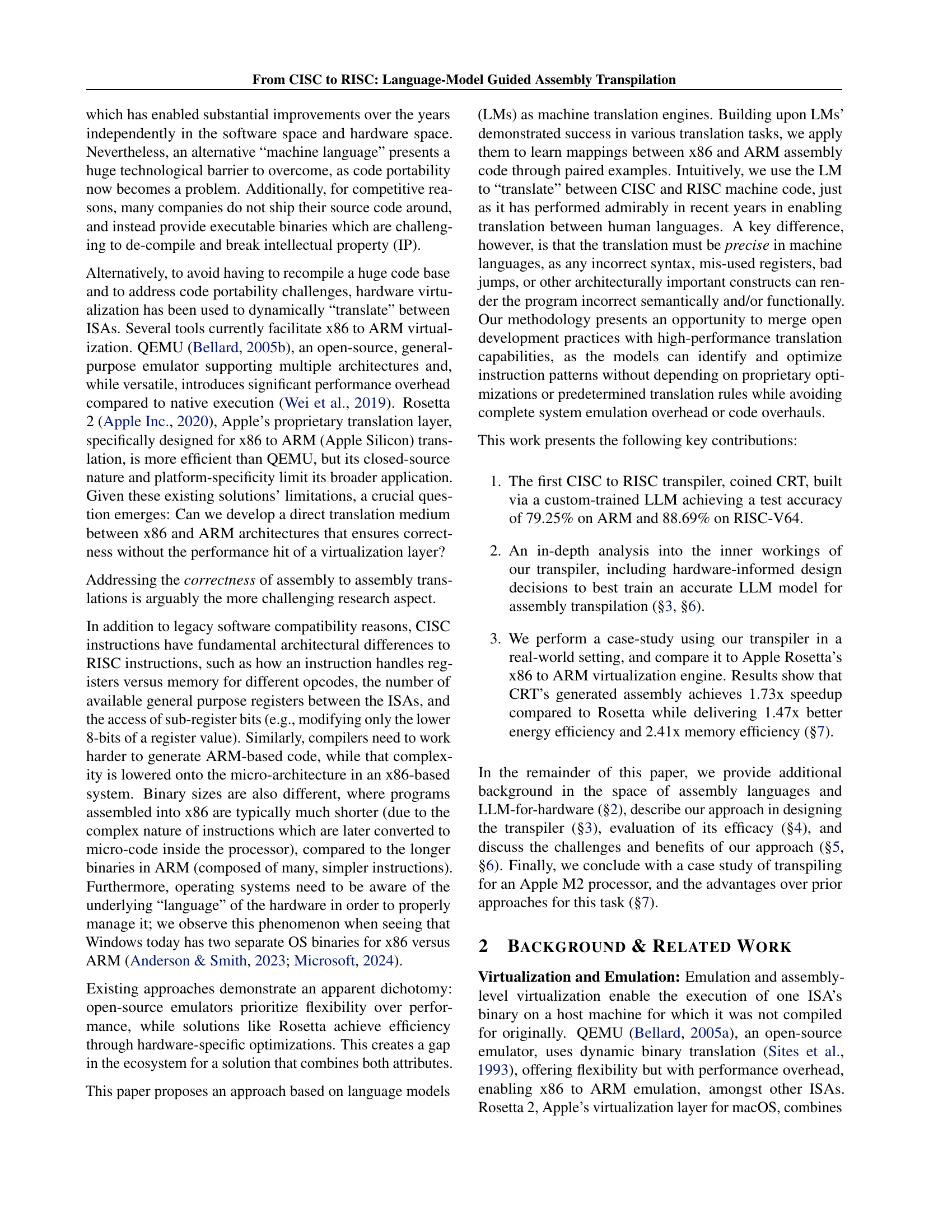

🔼 Figure 1 illustrates the central concept of a direct assembly-to-assembly transpiler. Unlike traditional compilation methods that rely on high-level source code, this transpiler performs a direct translation between two different machine instruction sets (ISAs), such as x86 and ARM. The process bypasses the typical software stack (compiler, linker, etc.), taking assembly code as input and producing equivalent assembly code in the target ISA as output. This offers a potential solution for translating legacy x86 code to ARM without requiring access to the original source code, resolving portability challenges in software.

read the caption

Figure 1: Conceptual representation of an asm-to-asm transpiler, which would enable direct “translation” from one machine language to another without needing the source code and by-passing the software stack.

| Input | Tokenizer | DeepSeek/Yi-Coder | Our Extended Tokenizer |

|---|---|---|---|

ldr r1, r2 | Tokens | ld<font color="#FFD9D9">r</font><font color="#FFFFD9">1</font><font color="#D9FFD9">␣</font><font color="#D9D9FF">r</font><font color="#FFFFD9">2</font><font color="#FFECD9">,</font><font color="#F5D9E2">␣</font> | ldr<font color="#D9FFD9">␣</font><font color="#D9D9FF">r1</font><font color="#FFECD9">,</font><font color="#F5D9E2">␣</font><font color="#D9FFFF">r2</font> |

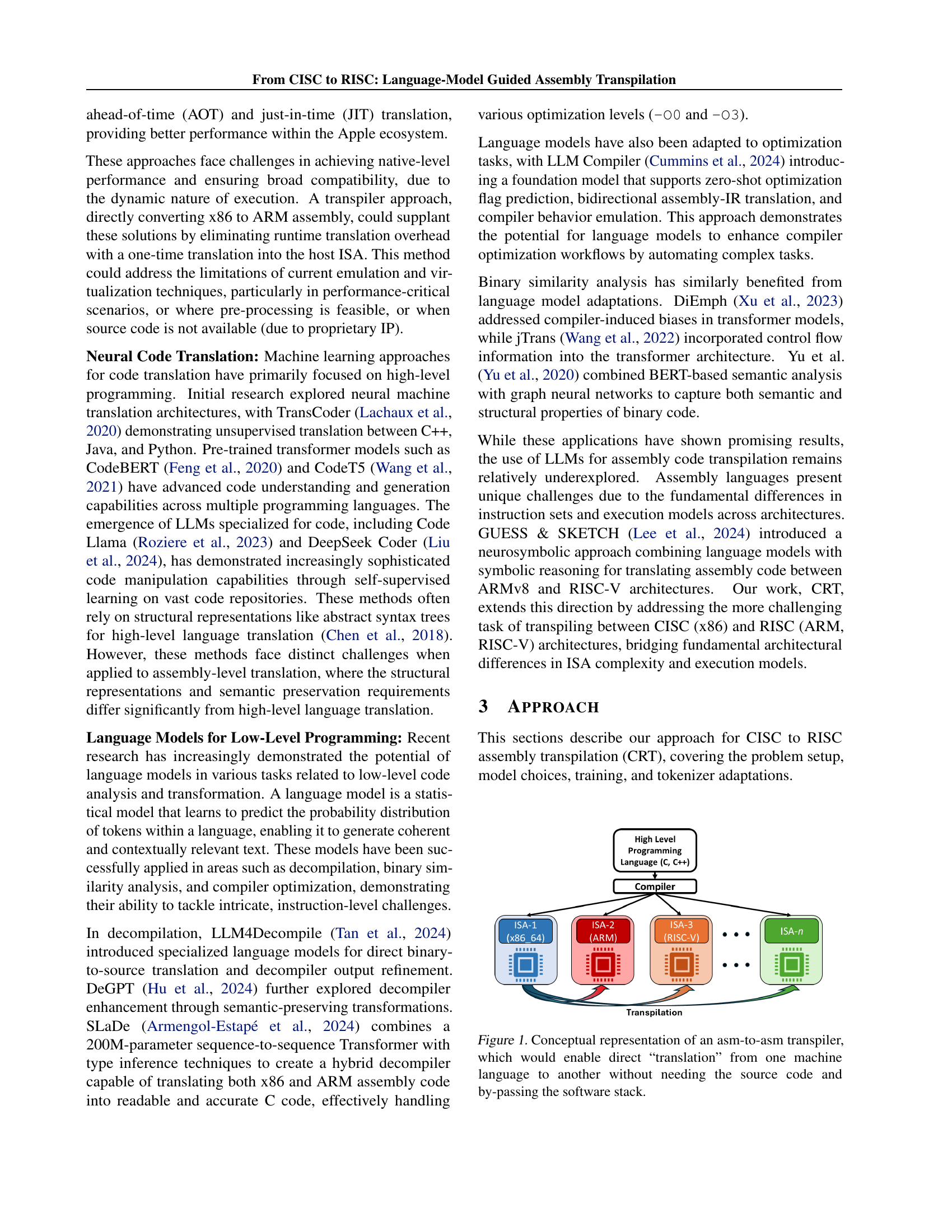

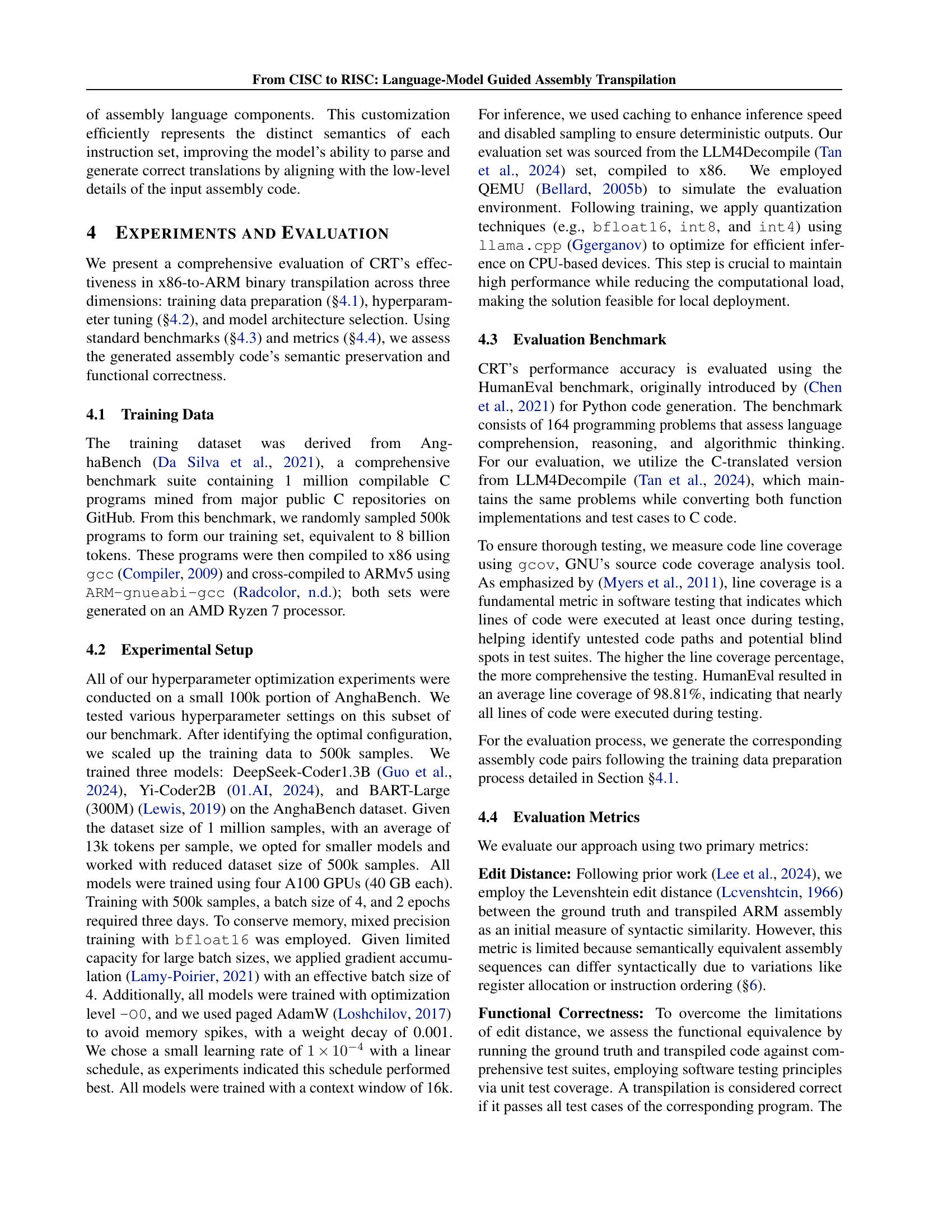

🔼 This table compares the tokenization methods used by the pre-trained language models DeepSeek and Yi-Coder with the extended tokenizer developed by the authors. The extended tokenizer is designed to improve the accuracy of assembly language translation by treating related tokens (such as instruction mnemonics and registers) as single units rather than splitting them, thus enhancing the model’s understanding of the low-level semantics of assembly language instructions. The table uses visual cues, such as colored backgrounds and the symbol ␣ to represent spaces, to highlight the differences in how each tokenizer processes and breaks down a simple assembly instruction into constituent tokens.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of tokenization approaches between DeepSeek/Yi-Coder and our extended tokenizer. Spaces are represented as ␣ and shown with colored backgrounds to highlight token boundaries. Note how our tokenizer groups related tokens (e.g., ldr and r1) as singular units.

In-depth insights#

CISC-RISC Transpilation#

The research paper explores CISC-to-RISC transpilation using large language models (LLMs). This is a significant undertaking because of fundamental architectural differences between Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC) and Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) architectures. The paper highlights the challenges of direct translation, particularly the need to maintain semantic correctness while navigating variations in instruction encoding, register usage, and memory addressing. The use of LLMs offers a potential solution, leveraging their ability to learn complex mappings between different instruction sets. The approach presented promises efficient translation, potentially surpassing the performance of traditional virtualization techniques like QEMU or Rosetta. However, achieving high accuracy and efficiency remains a challenge, requiring careful consideration of model selection, training data, and optimization techniques. The impact of tokenization and quantization on performance is also analyzed. The results demonstrate the feasibility of LLM-based transpilation, achieving significant speedups and improvements in energy efficiency and memory usage compared to virtualization. Future research should focus on addressing remaining limitations, particularly in handling complex instructions and ensuring robustness across different RISC architectures.

LLM-based Approach#

The core of this research lies in its novel LLM-based approach to assembly code translation. Instead of relying on traditional rule-based methods or complex emulation techniques, the authors leverage the power of large language models (LLMs) to learn the intricate mappings between CISC (x86) and RISC (ARM, RISC-V) instruction sets. This approach is particularly innovative because it directly addresses the significant architectural differences between these instruction sets, bypassing the need for intermediate representations or complex code transformations. The use of LLMs allows the system to learn complex relationships and patterns from data, potentially leading to higher accuracy and efficiency than rule-based methods. Furthermore, the ability of LLMs to generalize from training data suggests that the system could be adapted to support other ISA pairs without needing extensive modifications. The success of this approach hinges on the creation of a high-quality training dataset and careful model selection and tuning, as demonstrated by the experimental results which highlight significant performance gains over existing virtualization methods. This data-driven approach offers a promising pathway towards improved portability and performance in cross-ISA code translation.

CRT Model Analysis#

A CRT model analysis would delve into the architecture and performance characteristics of the proposed cross-compiler. Key aspects would include evaluating its accuracy in translating CISC (x86) assembly to RISC (ARM/RISC-V) assembly, assessing the efficiency of the generated code in terms of execution speed, energy consumption, and memory usage compared to native code and existing virtualization solutions. The analysis should also examine the limitations of the model, such as error types and rates, and discuss the reasons behind them. A crucial element would be comparing the model’s performance across different RISC architectures (ARMv5 vs. ARMv8) to understand the impact of architectural complexity. The analysis might also investigate the model’s ability to handle various code constructs, its robustness to different compilation settings, and its scalability with the size of the input code. Finally, a robust analysis would explore the trade-offs between model size, performance, and accuracy to determine the model’s overall suitability for practical applications.

Architectural Effects#

Analyzing the architectural effects of translating CISC (x86) to RISC (ARM, RISC-V) assembly reveals significant challenges stemming from fundamental differences in instruction sets and memory management. Direct translation is hindered by varying register sizes, different instruction lengths and complexities, and contrasting memory addressing modes. The impact is visible in the study’s results: While achieving high functional correctness (79.25% accuracy for ARM, 88.68% for RISC-V), the transpiler frequently generates syntactically different but semantically equivalent code. This indicates that the language model successfully captures the underlying logic despite architectural variations, but that a direct one-to-one mapping isn’t always possible. Furthermore, the transition to ARMv8 from ARMv5 showcases how increasing architectural complexity affects translation accuracy, highlighting the sensitivity of the approach to even minor ISA changes. Future improvements should focus on addressing these architectural nuances through more sophisticated tokenization and model training techniques.

Future Improvements#

Future improvements for this CISC-to-RISC assembly transpiler could focus on several key areas. Expanding the training dataset with more diverse and complex code examples would likely enhance accuracy and robustness. Addressing the limitations of current tokenization techniques, particularly for numerical values, would improve the model’s ability to handle complex instructions. Investigating advanced model architectures, like larger language models or hybrid approaches that combine LLMs with symbolic reasoning, may provide substantial performance gains. Improving the handling of specific ISA features, such as memory addressing and register management, could address common error patterns. Lastly, exploring techniques to better preserve functional correctness, beyond simple line-by-line comparison, might leverage intermediate representations or semantic analysis to improve the overall quality of the generated ARM code.

More visual insights#

More on figures

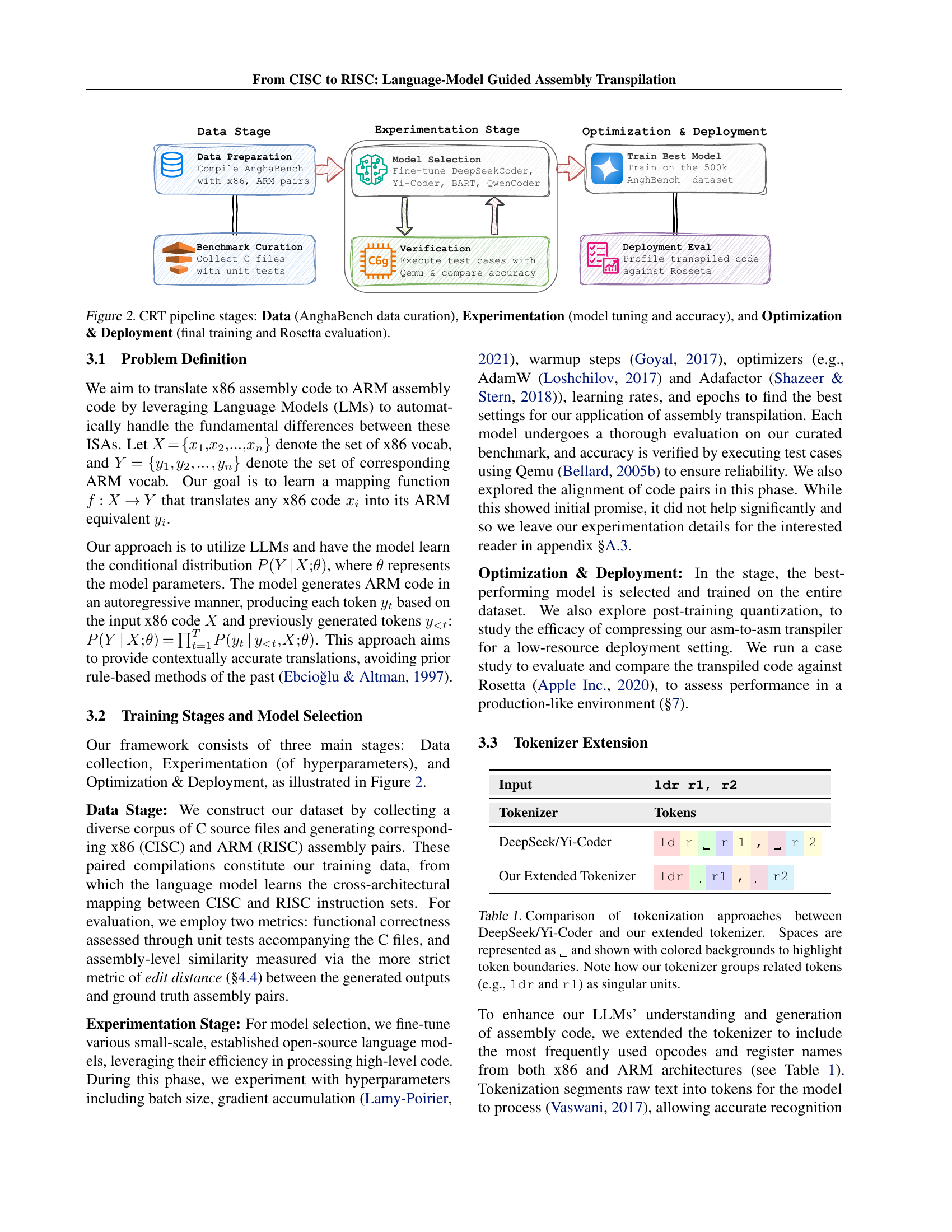

🔼 The figure illustrates the three main stages of the CRT (CISC to RISC transpiler) pipeline. The Data stage involves the curation of the AnghaBench dataset, which consists of paired x86 and ARM assembly code generated from a large corpus of C programs. The Experimentation stage focuses on model selection and hyperparameter tuning using a subset of the data. Various models are evaluated based on accuracy and other metrics to identify the optimal configuration. The Optimization & Deployment stage includes training the best-performing model on the complete dataset, followed by evaluation against Apple’s Rosetta 2 transpiler to assess efficiency and performance of the transpiled code.

read the caption

Figure 2: CRT pipeline stages: Data (AnghaBench data curation), Experimentation (model tuning and accuracy), and Optimization & Deployment (final training and Rosetta evaluation).

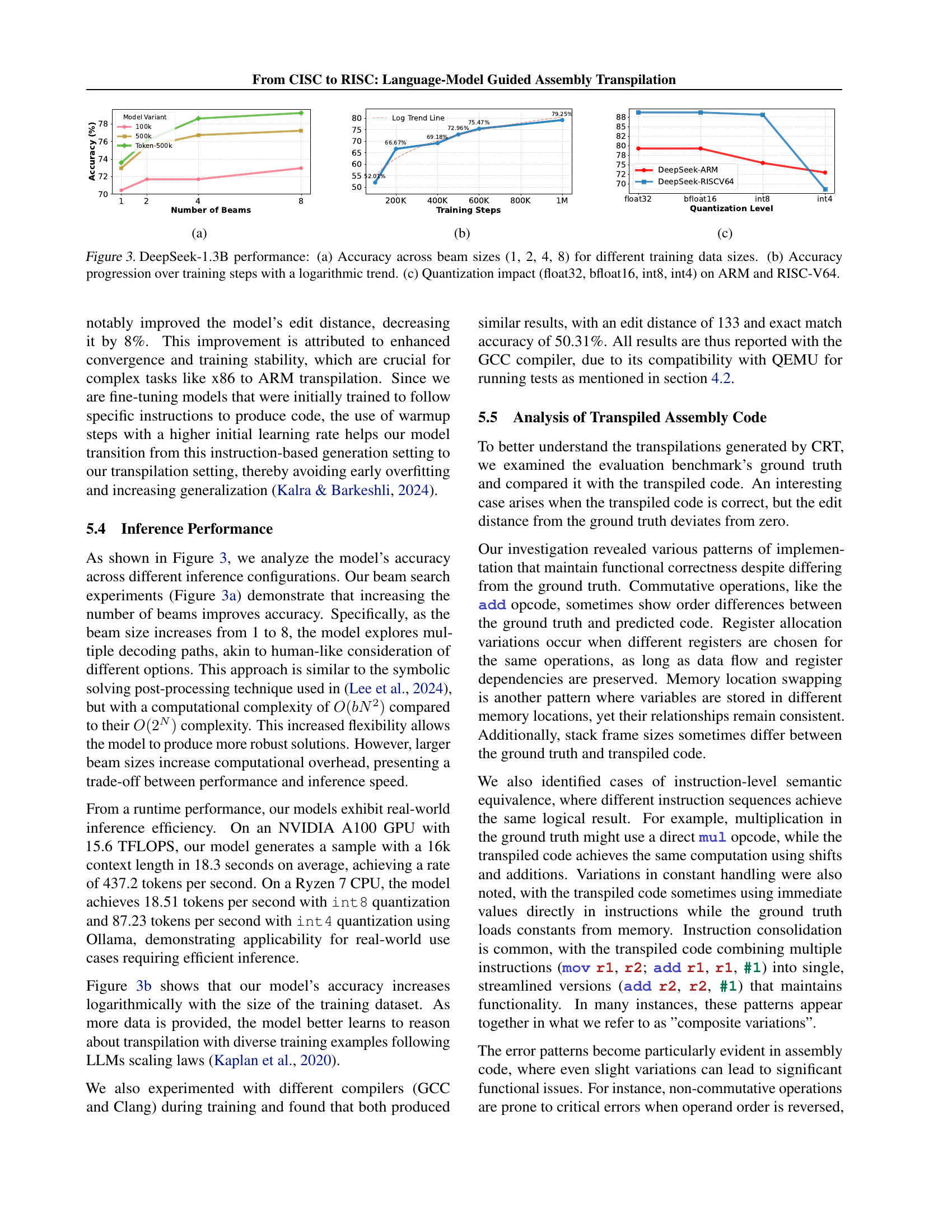

🔼 The figure shows the relationship between the number of beams used during inference and the accuracy of the model for different training data sizes. Increasing the number of beams allows the model to explore multiple decoding paths, improving accuracy at the cost of increased computational overhead. The accuracy plateaus at around 76% regardless of training data size when using only one beam. Using multiple beams shows improved accuracy, particularly with larger training datasets, but the gains diminish as the number of beams is increased.

read the caption

(a)

🔼 The figure shows the accuracy of the DeepSeek-1.3B model over training steps, illustrating the model’s performance improvement during the training process. The graph plots accuracy against the number of training steps, revealing an overall upward trend indicating improvement in the model’s ability to translate x86 assembly to ARM assembly.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 The figure shows the impact of quantization on the accuracy of the DeepSeek-1.3B model for both ARM and RISC-V64 architectures. It compares the accuracy achieved using different quantization levels: float32 (full precision), bfloat16 (reduced precision), int8 (integer with 8 bits), and int4 (integer with 4 bits). The graph illustrates the trade-off between model size/inference speed and accuracy resulting from quantization. Lower bit depths generally lead to lower accuracy but also smaller model sizes and faster inference speeds.

read the caption

(c)

🔼 Figure 3 displays the performance of the DeepSeek-1.3B model in three subfigures. (a) shows how the model’s accuracy on the task changes with different beam sizes (1, 2, 4, and 8) when trained on varying amounts of data. The plot demonstrates the impact of exploring multiple translation possibilities during inference. (b) illustrates the model’s accuracy improvement as training progresses, showing a logarithmic trend indicating diminishing returns from additional training. (c) examines the influence of quantization (reducing the precision of the model’s numerical representations) using float32, bfloat16, int8, and int4 on the model’s performance for both ARM and RISC-V64 architectures. This subfigure shows the tradeoff between accuracy and computational efficiency when using lower-precision representations.

read the caption

Figure 3: DeepSeek-1.3B performance: (a) Accuracy across beam sizes (1, 2, 4, 8) for different training data sizes. (b) Accuracy progression over training steps with a logarithmic trend. (c) Quantization impact (float32, bfloat16, int8, int4) on ARM and RISC-V64.

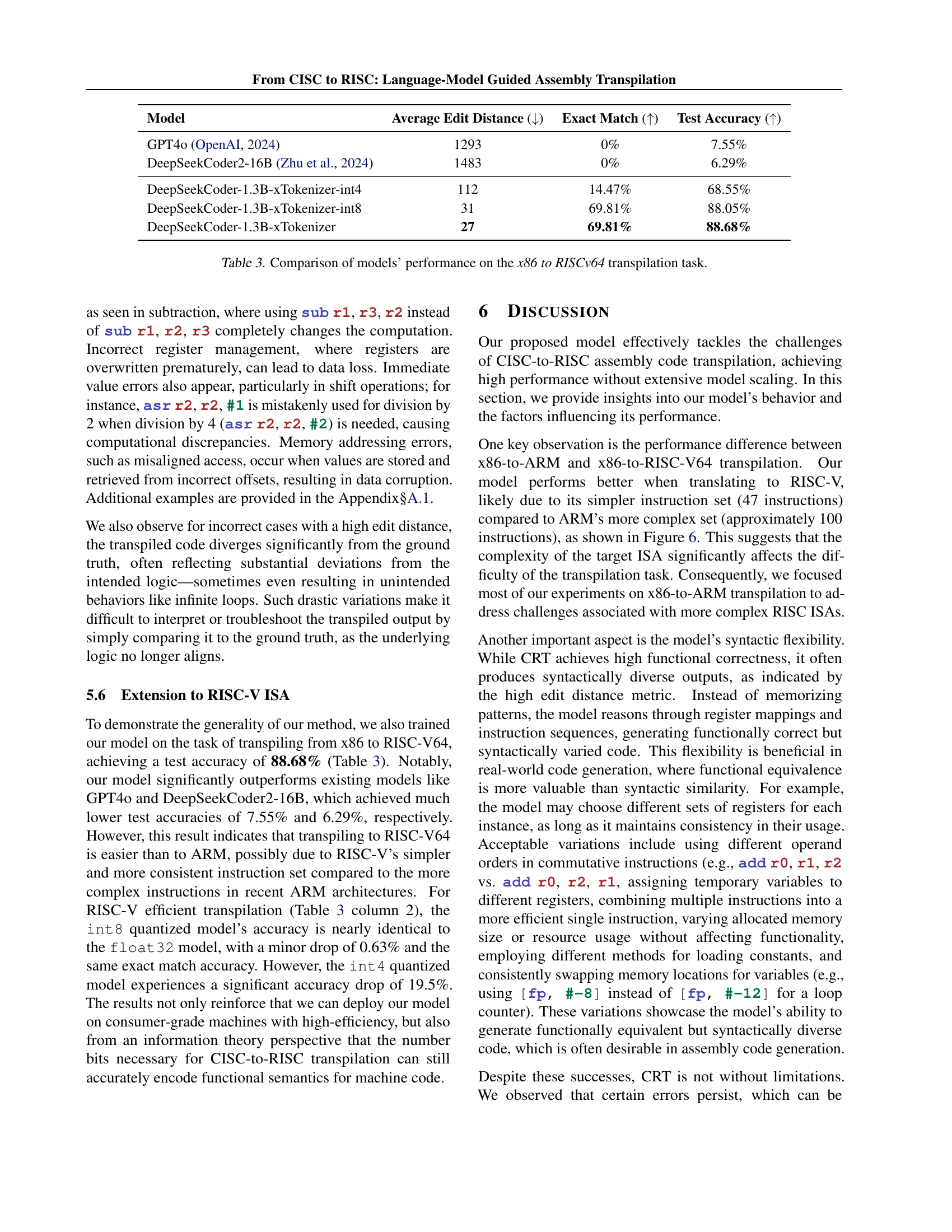

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of execution time, CPU energy consumption, and RAM usage for three different scenarios on an Apple M2 MacBook: native ARM64 code execution, execution using Apple’s Rosetta 2 translation layer (for x86 code), and execution of code transpiled from x86 to ARM64 using the proposed CRT method. The results show significant performance improvements with CRT compared to Rosetta, demonstrating CRT’s efficiency in executing transpiled code.

read the caption

Figure 4: Measured execution time, energy utilization, and RAM usage across different settings on Apple M2 Macbook.

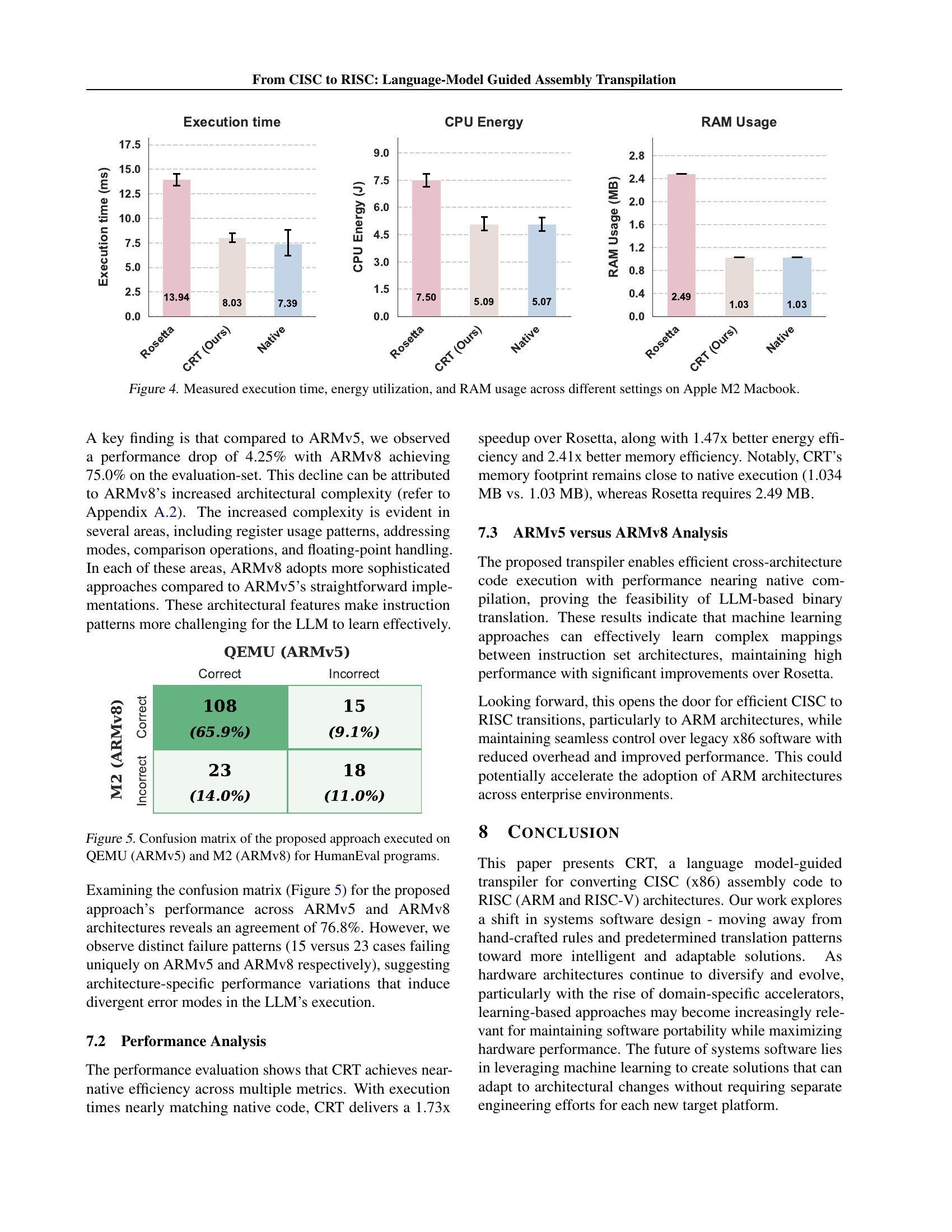

🔼 This figure shows a confusion matrix that evaluates the performance of the proposed CRT (CISC-to-RISC transpiler) model on two different ARM architectures: ARMv5 (simulated using QEMU) and ARMv8 (Apple M2). The matrix displays the counts of correct and incorrect translations for each architecture. The results are broken down by whether the translated assembly code successfully passes the HumanEval benchmark tests (indicating functional correctness). The matrix helps to assess the accuracy and reliability of the CRT model across different hardware platforms, highlighting potential architectural-specific issues in the translation process.

read the caption

Figure 5: Confusion matrix of the proposed approach executed on QEMU (ARMv5) and M2 (ARMv8) for HumanEval programs.

🔼 This figure compares assembly code generated from the same source code for three different architectures: x86 (CISC), ARMv5 (RISC), and ARMv8 (RISC). It highlights how the same high-level operations translate into vastly different low-level instructions across these architectures, showcasing the complexities of translating assembly language between different instruction sets. The alignment of code segments emphasizes the corresponding functionalities across the different ISAs, visually demonstrating the challenges inherent in assembly-to-assembly translation.

read the caption

Figure 6: Example Assembly Code Generated from Identical Source Program for x86, ARMv5, and ARMv8, with aligned assembly segments highlighted by functionality.

More on tables

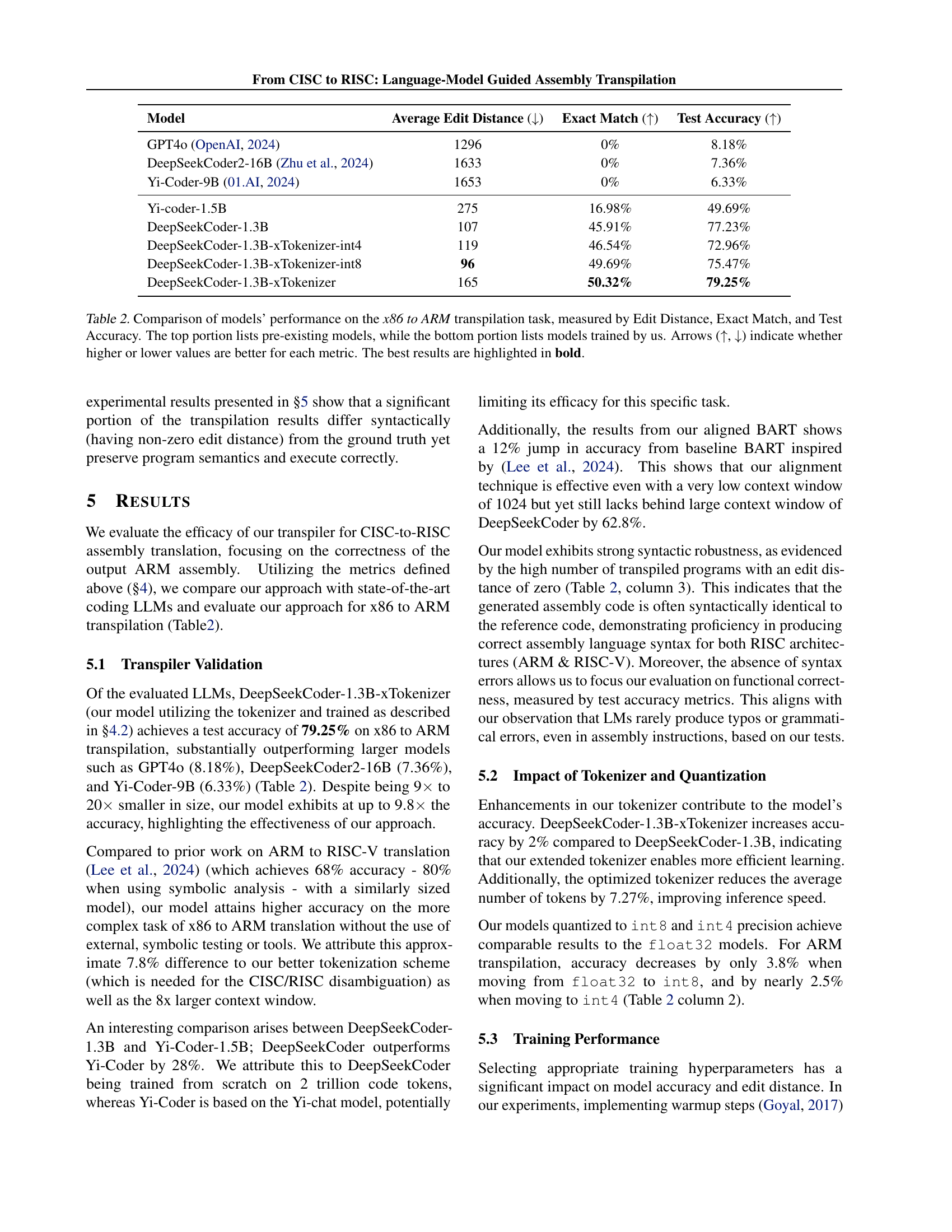

🔼 This table compares the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on the task of translating x86 assembly code to ARM assembly code. The models are evaluated using three metrics: Edit Distance (lower is better, measuring the difference between the generated ARM code and the ground truth), Exact Match (higher is better, indicating whether the generated code perfectly matches the ground truth), and Test Accuracy (higher is better, reflecting the percentage of test cases passed by the generated code). The top half of the table shows results for pre-trained, publicly available LLMs, while the bottom half displays results for models fine-tuned by the authors of the paper. The arrows in the caption indicate whether a higher or lower value is preferable for each metric. The best performing model for each metric is shown in bold.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of models’ performance on the x86 to ARM transpilation task, measured by Edit Distance, Exact Match, and Test Accuracy. The top portion lists pre-existing models, while the bottom portion lists models trained by us. Arrows (↑↑\uparrow↑, ↓↓\downarrow↓) indicate whether higher or lower values are better for each metric. The best results are highlighted in bold.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different large language models (LLMs) on their performance in translating x86 assembly code to RISC-V64 assembly code. The metrics used for comparison include average edit distance (a measure of the syntactic similarity between the generated and ground truth assembly code), exact match (the percentage of translations that are exactly identical to the ground truth), and test accuracy (the percentage of translations that pass all the associated test cases, indicating functional correctness). Lower edit distance and higher exact match and test accuracy scores indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of models’ performance on the x86 to RISCv64 transpilation task.

| Model | Average Edit Distance (↓) | Exact Match (↑) | Test Accuracy (↑) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT4o OpenAI (2024) | 1296 | 0% | 8.18% |

| DeepSeekCoder2-16B Zhu et al. (2024) | 1633 | 0% | 7.36% |

| Yi-Coder-9B 01.AI (2024) | 1653 | 0% | 6.33% |

| Yi-coder-1.5B | 275 | 16.98% | 49.69% |

| DeepSeekCoder-1.3B | 107 | 45.91% | 77.23% |

| DeepSeekCoder-1.3B-xTokenizer-int4 | 119 | 46.54% | 72.96% |

| DeepSeekCoder-1.3B-xTokenizer-int8 | 96 | 49.69% | 75.47% |

| DeepSeekCoder-1.3B-xTokenizer | 165 | 50.32% | 79.25% |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of the CRT (CISC to RISC transpiler) model on two different ARM architectures: ARMv5 and ARMv8. The comparison is made using three key metrics: Average Edit Distance (AED), Exact Match (EM), and Test Accuracy (Acc.). AED quantifies the difference between the generated ARM assembly code and the ground truth, with a lower score indicating better similarity. EM indicates the percentage of test cases where the generated code produced the exact same output as the ground truth. Test Accuracy shows the overall functional correctness, representing the fraction of test cases where the generated code successfully passed all tests. This comparison reveals the model’s performance consistency and its behavior when handling varying levels of architectural complexity within the ARM ISA.

read the caption

Table 4: Correctness comparison between CRT implementations on ARMv5 and ARMv8 architectures. Metrics include Average Edit Distance (AED), Exact Match (EM), and Test Accuracy (Acc.).

| Model | Average Edit Distance (↓) | Exact Match (↑) | Test Accuracy (↑) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT4o [2024] | 1293 | 0% | 7.55% |

| DeepSeekCoder2-16B [2024] | 1483 | 0% | 6.29% |

| DeepSeekCoder-1.3B-xTokenizer-int4 | 112 | 14.47% | 68.55% |

| DeepSeekCoder-1.3B-xTokenizer-int8 | 31 | 69.81% | 88.05% |

| DeepSeekCoder-1.3B-xTokenizer | 27 | 69.81% | 88.68% |

🔼 This table presents examples of functionally equivalent assembly code snippets that exhibit syntactic variations, despite having the same logical outcome. It showcases instances where seemingly minor differences in register allocation, operand ordering (for commutative operations), and stack variable locations do not affect the program’s functionality. The goal is to illustrate that superficial dissimilarities between the ground-truth assembly code and the model’s generated code do not always indicate errors, as semantically equivalent implementations can vary.

read the caption

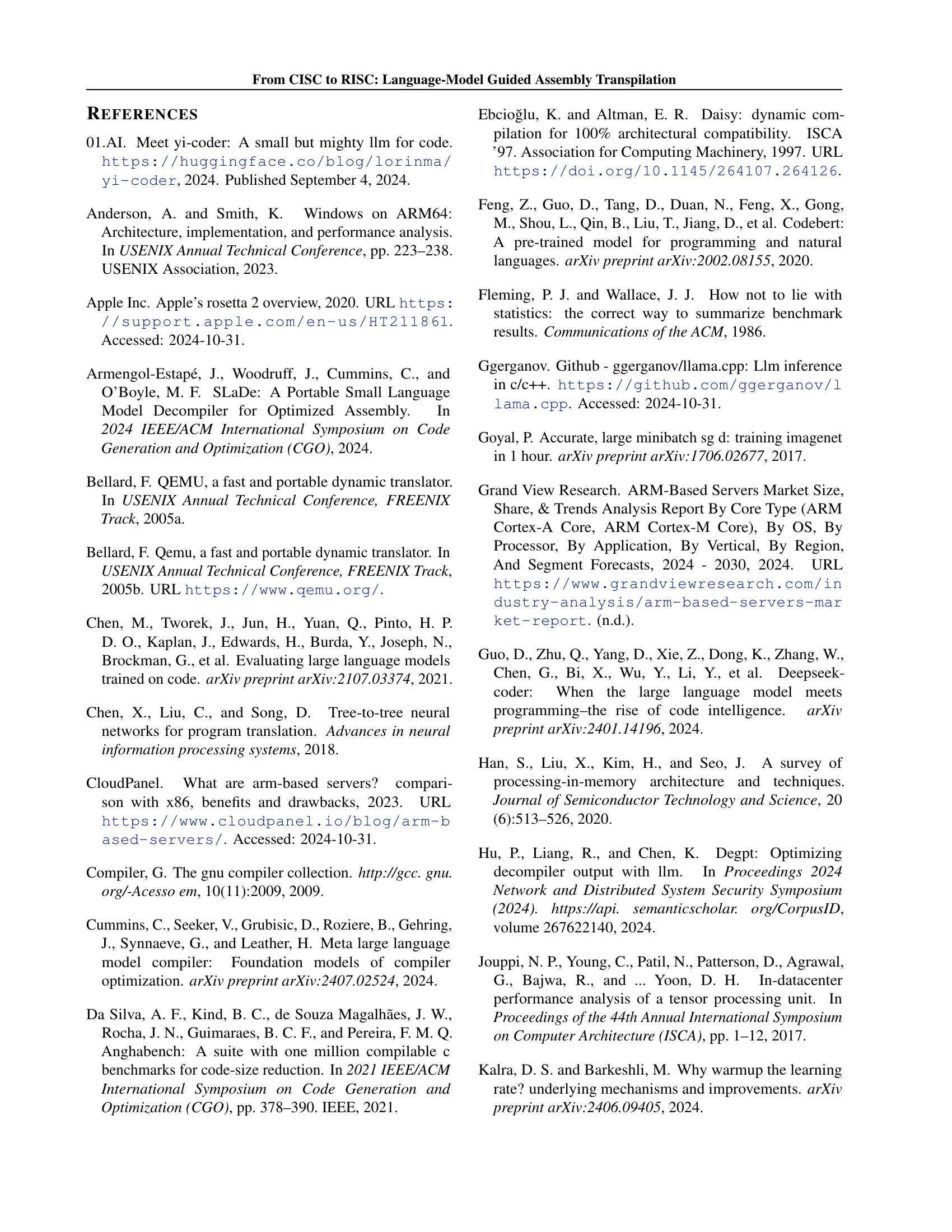

Table 5: Simple Variation Patterns in Functionally Equivalent Code

| Model | AED ( ) ) | EM ( ) ) | Acc. ( ) ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRT ARMv5 | 165 | 50.32% | 79.25% |

| CRT ARMv8 | 105 | 50.61% | 75.0% |

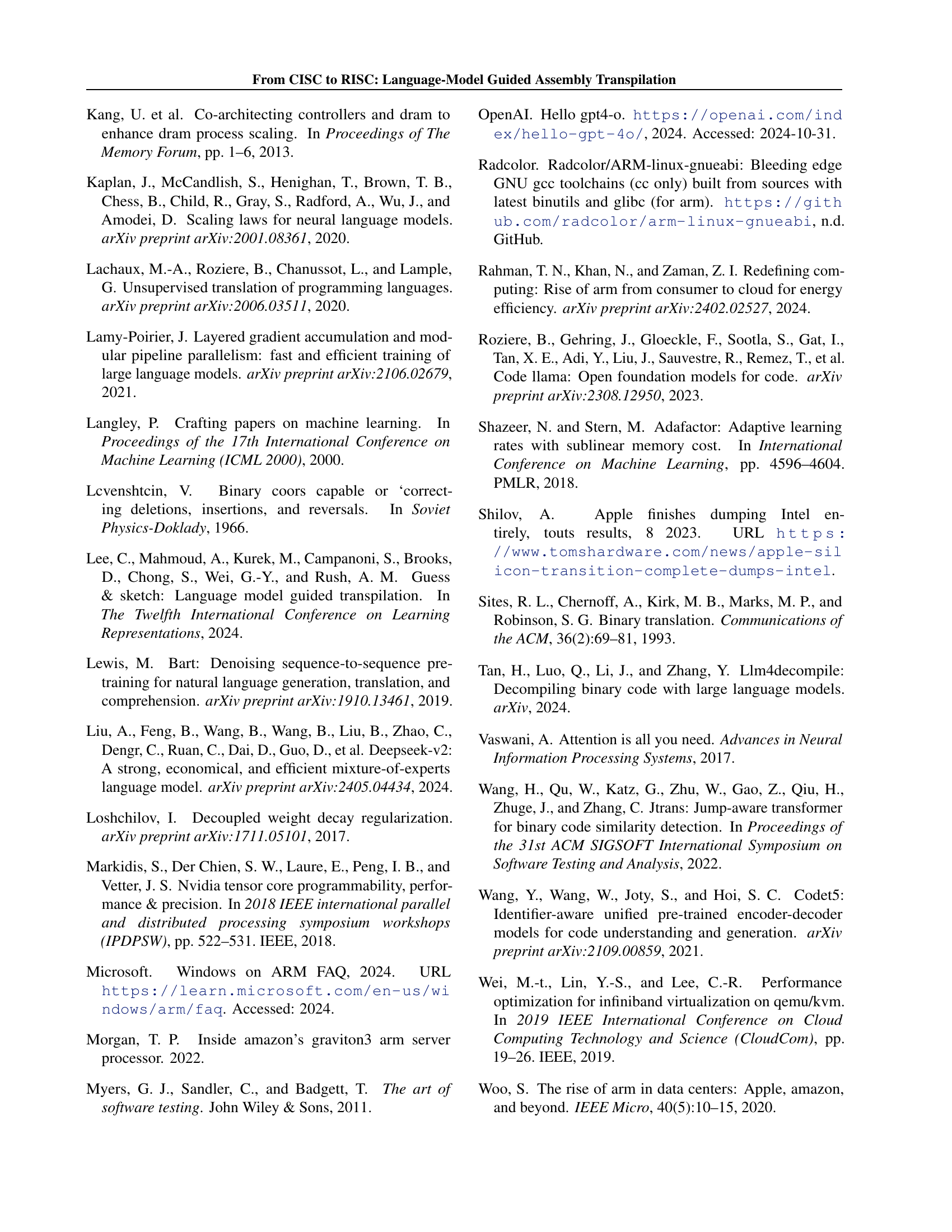

🔼 This table details instances where functionally equivalent assembly code exhibits multiple types of differences between the ground truth and the model’s output. These differences include variations in operand order for commutative operations, register selection, memory locations, instruction combinations, and constant handling. The table shows how these variations can appear in combination to produce functionally correct but syntactically different assembly code.

read the caption

Table 6: Complex Variation Patterns with Multiple Differences

| Prog ID | Edit Dist | Example |

|---|---|---|

| P75 | 8 | Operands in arithmetic operations can be reordered if operation is commutative |

Ground truth: add r1, r2, r3 | ||

Predicted: add r1, r3, r2 | ||

| P108 | 16 | Different registers can be chosen for temporary values while maintaining same data flow |

Ground truth: mov r2, r0; add r2, r2, #1 | ||

Predicted: mov r3, r0; add r3, r3, #1 | ||

| P8 | 12 | Local variables can be stored at different stack locations while maintaining correct access patterns |

Ground truth: str r1, [fp, #-8]; str r2, [fp, #-12] | ||

Predicted: str r1, [fp, #-12]; str r2, [fp, #-8] | ||

| P119 | 6 | Compiler-generated symbol names can differ while referring to same data |

Ground truth: .word out.4781 | ||

Predicted: .word out.4280 | ||

| P135 | 12 | Multiple instructions can be combined into single equivalent instruction |

Ground truth: mov r3, r0; | ||

str r3, [fp, #-8] | ||

Predicted: str r0, [fp, #-8] | ||

| P162 | 4 | Stack frame offsets can vary while maintaining correct variable access |

Ground truth: strb r3, [fp, #-21] | ||

Predicted: strb r3, [fp, #-17] | ||

| P88 | 23 | Memory allocation sizes can vary if sufficient for program needs |

Ground truth: mov r0, #400 | ||

Predicted: mov r0, #800 | ||

| P103 | 52 | Different instruction sequences can achieve same logical result |

Ground truth: cmp r3, #0; and r3, r3, #1; rsblt r3, r3, #0 | ||

Predicted: rsbs r2, r3, #0; and r3, r3, #1; and r2, r2, #1; rsbpl r3, r2, #0 | ||

| P69 | 50 | Constants can be loaded directly or from literal pool |

Ground truth: mvn r3, #-2147483648 | ||

Predicted: ldr r3, .L8; .L8: .word 2147483647 |

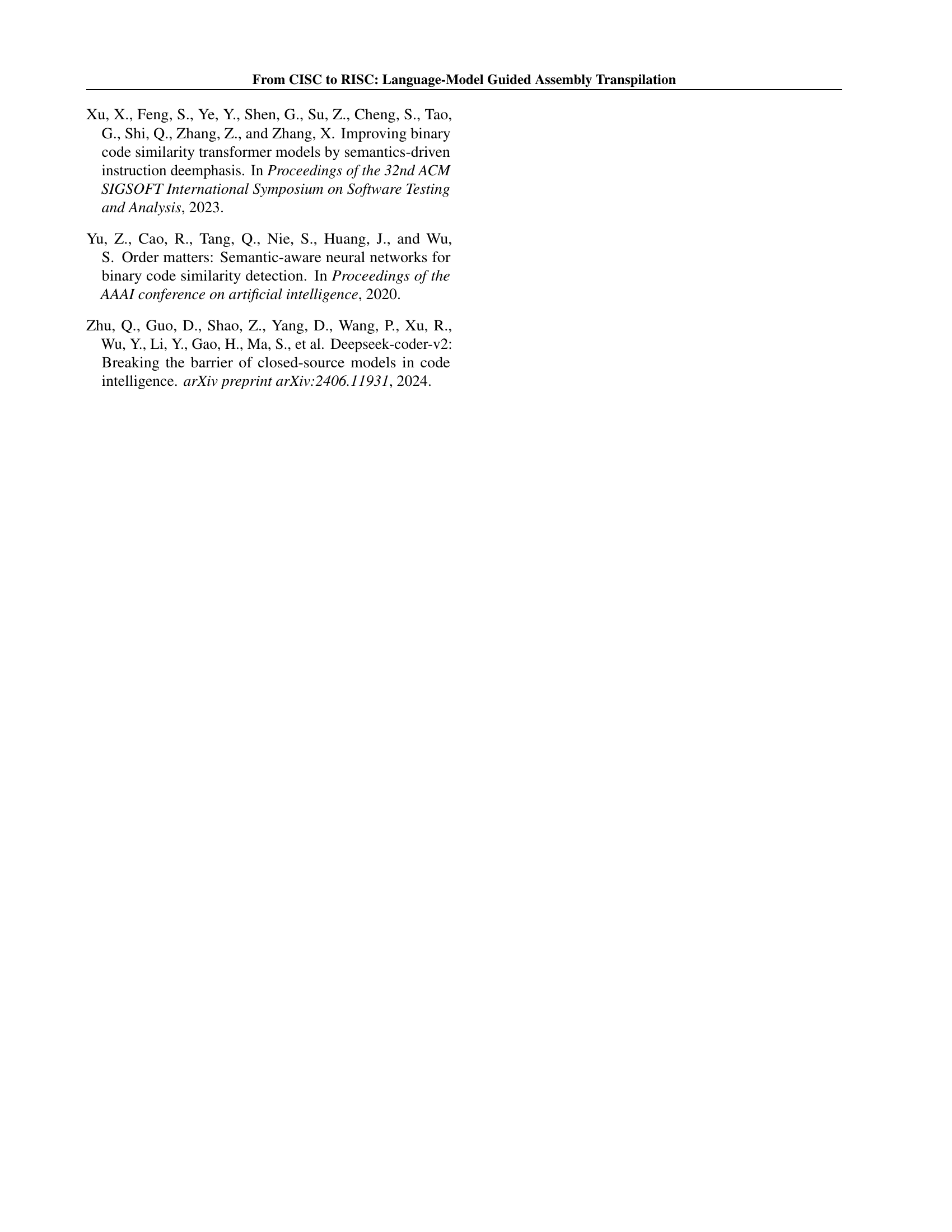

🔼 This table presents a detailed analysis of critical errors in assembly code transpilation where the differences between the ground truth and the predicted assembly code are minimal (small edit distances). It focuses on cases where the errors cause the transpiled code to fail functional tests, providing insights into how subtle differences can lead to significant problems. For each example, the table shows the program ID (Prog ID), the edit distance (Edit Dist), and the specific error type observed with illustrative code snippets from both the ground truth and the incorrectly transpiled assembly.

read the caption

Table 7: Analysis of Critical Errors with Small Edit Distances

Full paper#