↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current latent video diffusion models (LVDMs) face limitations in handling high-resolution videos due to inefficient Video Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) which are crucial for compressing videos into a latent space. The block-wise inference methods typically used also lead to discontinuities in the latent space when processing long videos, causing artifacts. These challenges increase the training cost and reduce the quality of video generated.

To address these issues, this paper proposes WF-VAE. This novel VAE uses wavelet transformation to decompose videos into various frequency bands and focuses mainly on the low-frequency information. This results in significantly improved encoding efficiency. Additionally, a new method called Causal Cache is introduced to maintain the integrity of latent space during block-wise inference, resolving discontinuities. The results demonstrated that WF-VAE outperforms existing VAEs in terms of quality and efficiency, showing a 2x improvement in throughput and 4x reduction in memory consumption.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on video generation and compression. It introduces a novel Wavelet Flow VAE (WF-VAE) that significantly improves the efficiency and quality of video encoding for latent video diffusion models. This addresses a major bottleneck in training high-resolution, long-duration video generation models, opening exciting avenues for future research and development in this rapidly growing field. The proposed Causal Cache mechanism tackles issues of latent space discontinuities effectively.

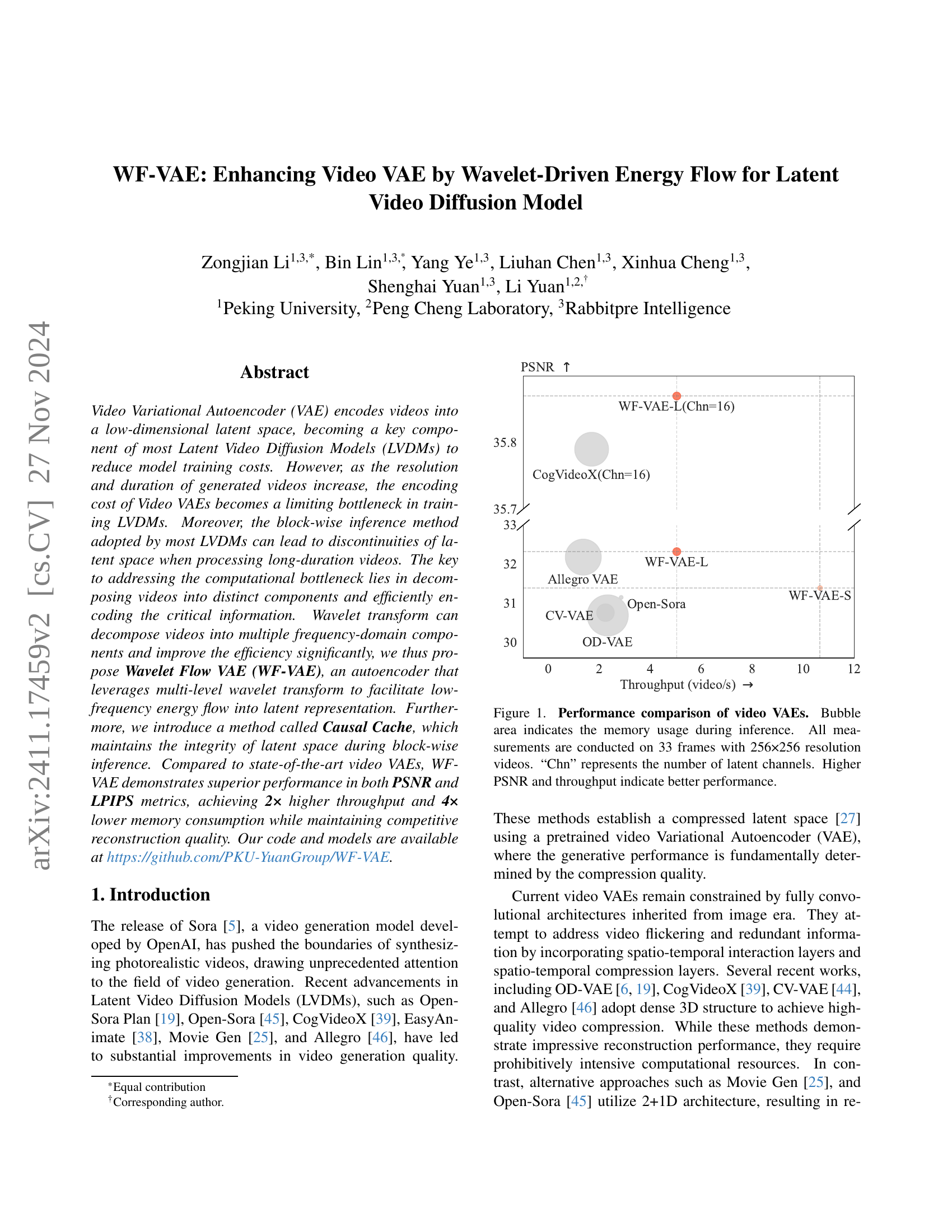

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 compares the performance of several video Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). The PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), a measure of reconstruction quality, is plotted against the throughput (videos processed per second). The size of each bubble in the chart visually represents the amount of memory used during the inference process. All VAEs were evaluated on videos consisting of 33 frames at a resolution of 256x256 pixels. The number of latent channels (‘Chn’) is shown for each VAE. Higher PSNR values and throughput rates indicate superior performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Performance comparison of video VAEs. Bubble area indicates the memory usage during inference. All measurements are conducted on 33 frames with 256×256 resolution videos. “Chn” represents the number of latent channels. Higher PSNR and throughput indicate better performance.

| Method | TCPR | Chn | WebVid-10M PSNR (↑) | WebVid-10M SSIM (↑) | WebVid-10M LPIPS (↓) | WebVid-10M FVD (↓) | Panda-70M PSNR (↑) | Panda-70M SSIM (↑) | Panda-70M LPIPS (↓) | Panda-70M FVD (↓) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD-VAE[27] | 64(1×8×8) | 4 | 30.19 | 0.8377 | 0.0568 | 284.90 | 30.46 | 0.8896 | 0.0395 | 182.99 |

| SVD-VAE[4] | 64(1×8×8) | 4 | 31.18 | 0.8689 | 0.0546 | 188.74 | 31.04 | 0.9059 | 0.0379 | 137.67 |

| CV-VAE[44] | 256(4×8×8) | 4 | 30.76 | 0.8566 | 0.0803 | 369.23 | 30.18 | 0.8796 | 0.0672 | 296.28 |

| OD-VAE[6] | 256(4×8×8) | 4 | 30.69 | 0.8635 | 0.0553 | 255.92 | 30.31 | 0.8935 | 0.0439 | 191.23 |

| Open-Sora VAE[45] | 256(4×8×8) | 4 | 31.14 | 0.8572 | 0.1001 | 475.23 | 31.37 | 0.8973 | 0.0662 | 298.47 |

| Allegro[46] | 256(4×8×8) | 4 | 32.18 | 0.8963 | 0.0524 | 209.68 | 31.70 | 0.9158 | 0.0421 | 172.72 |

| WF-VAE-S (Ours) | 256(4×8×8) | 4 | 31.39 | 0.8737 | 0.0517 | 188.04 | 31.27 | 0.9025 | 0.0420 | 146.91 |

| WF-VAE-L (Ours) | 256(4×8×8) | 4 | 32.32 | 0.8920 | 0.0513 | 186.00 | 32.10 | 0.9142 | 0.0411 | 146.24 |

| CogVideoX-VAE[39] | 256(4×8×8) | 16 | 35.72 | 0.9434 | 0.0277 | 59.83 | 35.79 | 0.9527 | 0.0198 | 43.23 |

| WF-VAE-L (Ours) | 256(4×8×8) | 16 | 35.76 | 0.9430 | 0.0230 | 54.36 | 35.87 | 0.9538 | 0.0175 | 39.40 |

🔼 Table 1 presents a quantitative comparison of video reconstruction performance between WF-VAE and other state-of-the-art VAEs on the WebVid-10M and Panda70M datasets. The metrics used for comparison are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS), and Fréchet Video Distance (FVD). Higher PSNR and SSIM values indicate better reconstruction quality, while lower LPIPS and FVD values are preferred. The table also shows the token compression rate (TCPR) and number of latent channels (Chn) for each model. The best performing model in each metric is shown in bold, and the second-best is underlined, highlighting WF-VAE’s superior reconstruction quality and efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative metrics of reconstruction performance. Results demostrate that WF-VAE achieves state-of-the-art on reconstrcution performance comparing with other VAEs on WebVid-10M[2] and Panda70M[7] datasets. TCPR represents the token compression rate and Chn indicates the number of latent channels. The highest result is highlighted in bold, and the second highest result is underlined.

In-depth insights#

Wavelet VAE Design#

A Wavelet VAE design leverages the multi-resolution capabilities of wavelet transforms to efficiently encode video data. Instead of processing the entire video frame directly, this approach decomposes the video into multiple frequency subbands, capturing both high-frequency details and low-frequency components. This decomposition allows the model to prioritize the encoding of essential information, reducing redundancy and computational costs. The design likely incorporates a multi-level wavelet transform to further refine the subband representation, potentially using a pyramidal structure to create a hierarchical representation. The choice of wavelet family is crucial, impacting the efficiency of the decomposition and the type of information preserved in each subband. This design could also incorporate a mechanism for managing the flow of information between subbands and the latent space, potentially prioritizing the low-frequency energy flow. This could be achieved via specially designed pathways or attention mechanisms. By decomposing and prioritizing the encoded information, a Wavelet VAE offers significant advantages in terms of computational efficiency and improved representation of video data. The effectiveness of the model hinges on the optimal selection of wavelets and the architecture of the encoder/decoder network. The overall design should aim for a balance between compression efficiency and reconstruction quality.

Causal Cache#

The concept of “Causal Cache” in the context of video processing addresses the challenge of maintaining latent space integrity during block-wise inference. Block-wise inference, while improving efficiency for long videos, often introduces discontinuities or artifacts at block boundaries. Causal Cache cleverly mitigates this by employing causal convolution, which inherently prevents information leakage from future frames into past frames during processing. This approach, combined with a caching mechanism that retains the trailing frames of each processed chunk, ensures seamless transitions between blocks. The result is that block-wise inference effectively mimics the outcome of processing the entire video at once. The implementation leverages the properties of causal convolution to guarantee the numerical identity between block-wise and direct inference results, thus preserving the integrity of the latent representation and eliminating artifacts such as flickering or discontinuities. The use of causal padding further enhances the performance and robustness of this method.

Efficiency Gains#

The concept of ‘Efficiency Gains’ in the context of a research paper likely centers on improvements in computational performance or resource utilization. Reduced computational complexity is a major target, often achieved through algorithmic refinements or architectural changes. This could involve optimizing existing methods, adopting more efficient data structures, or implementing novel techniques that drastically reduce processing time and memory consumption. A successful demonstration of efficiency gains would involve quantifiable metrics, such as speedup factors, memory savings, or improvements in throughput. Furthermore, analyzing the trade-offs between efficiency and accuracy is crucial; gains in speed should not come at the expense of significant performance degradation. The discussion might also include comparisons against state-of-the-art methods to highlight the relative advancement. Scalability is another important aspect: demonstrating that the efficiency improvements hold up as the size or complexity of the input data increases is essential. Finally, analyzing the energy efficiency of the improved methods is becoming increasingly relevant, thus a reduction in power consumption can also be considered as efficiency gains.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to understand their individual contributions. In this context, the ablation study likely investigates the impact of the wavelet transform, the Causal Cache mechanism, and the energy flow pathway. By removing each component individually and measuring the performance changes, the researchers could quantify the effectiveness of each design choice. Removing the wavelet transform would assess its role in enhancing low-frequency information encoding. Removing Causal Cache would show its impact on maintaining latency space integrity during block-wise inference. Finally, removing the energy flow pathway could demonstrate its contribution to efficient energy flow towards latent representation. The results would pinpoint which architectural components are crucial for the overall performance and highlight potential areas for future improvement. The study is crucial for establishing the model’s robustness and understanding the interplay between the design choices and the final model’s capabilities.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this Wavelet Flow VAE (WF-VAE) could explore several promising avenues. Firstly, enhancing the model’s scalability to handle even higher-resolution videos and longer durations is crucial. This may involve investigating more efficient wavelet transform implementations or exploring alternative compression techniques to further reduce computational costs. Secondly, the impact of different wavelet bases beyond Haar could be explored. Different wavelet bases offer diverse properties in terms of frequency decomposition and may lead to improved performance. Thirdly, integrating WF-VAE into more advanced video generation architectures warrants investigation. For example, combining it with state-of-the-art diffusion models could improve the quality and efficiency of video generation. Finally, the application of the Causal Cache mechanism to other tasks involving temporal data, beyond video processing, should be studied to assess its generalizability and potential benefits in various domains.

More visual insights#

More on figures

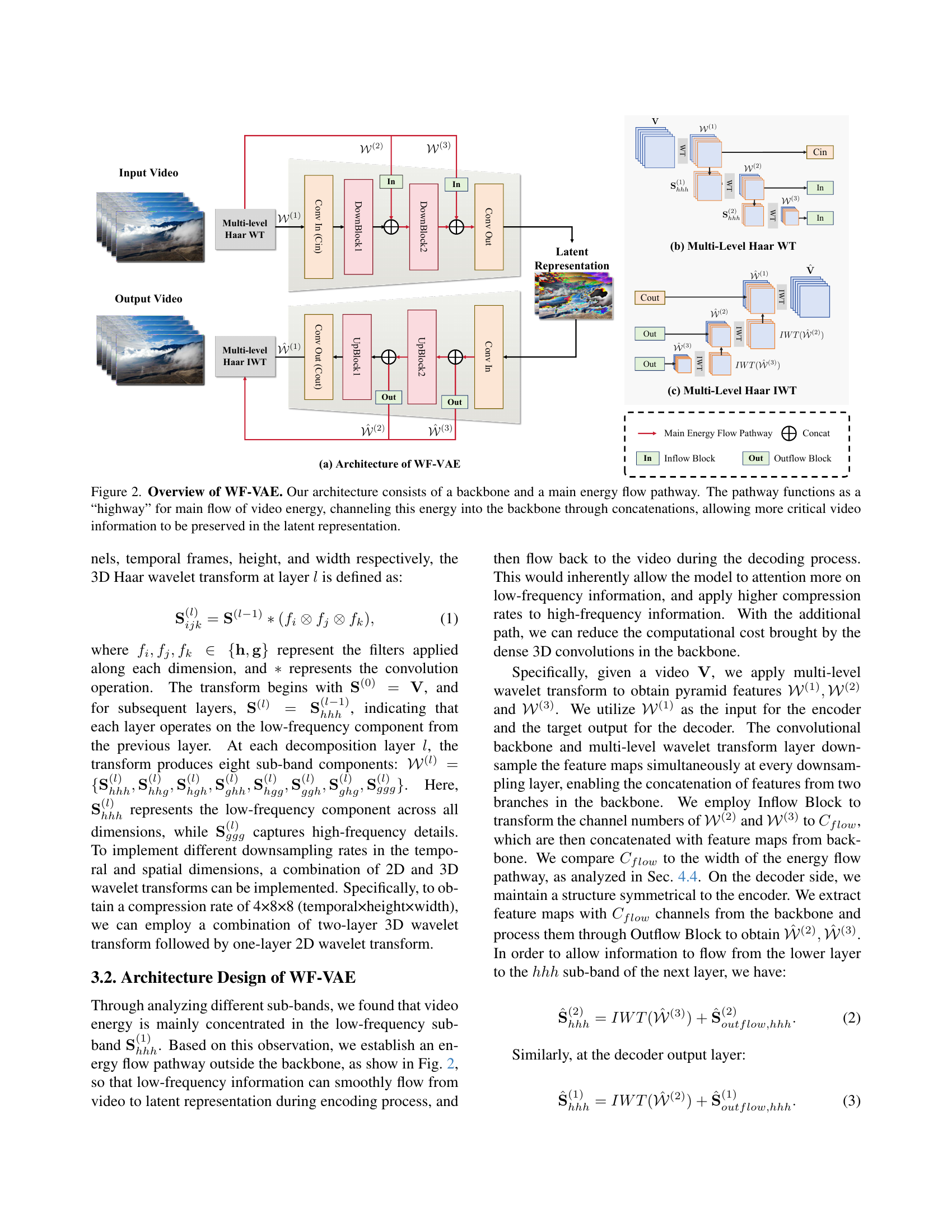

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Wavelet Flow VAE (WF-VAE). The WF-VAE consists of two main parts: a conventional backbone network and a dedicated energy flow pathway. The pathway is designed to prioritize the transmission of low-frequency information directly to the latent representation, bypassing some of the processing steps in the main backbone. This efficient transfer of crucial video data is achieved through wavelet transforms that decompose the input video into multiple frequency components. The low-frequency components are channeled through the pathway, while higher frequency components are handled by the backbone. This design helps to reduce computational costs and preserve crucial video information in the latent space, leading to improved efficiency and reconstruction quality.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of WF-VAE. Our architecture consists of a backbone and a main energy flow pathway. The pathway functions as a “highway” for main flow of video energy, channeling this energy into the backbone through concatenations, allowing more critical video information to be preserved in the latent representation.

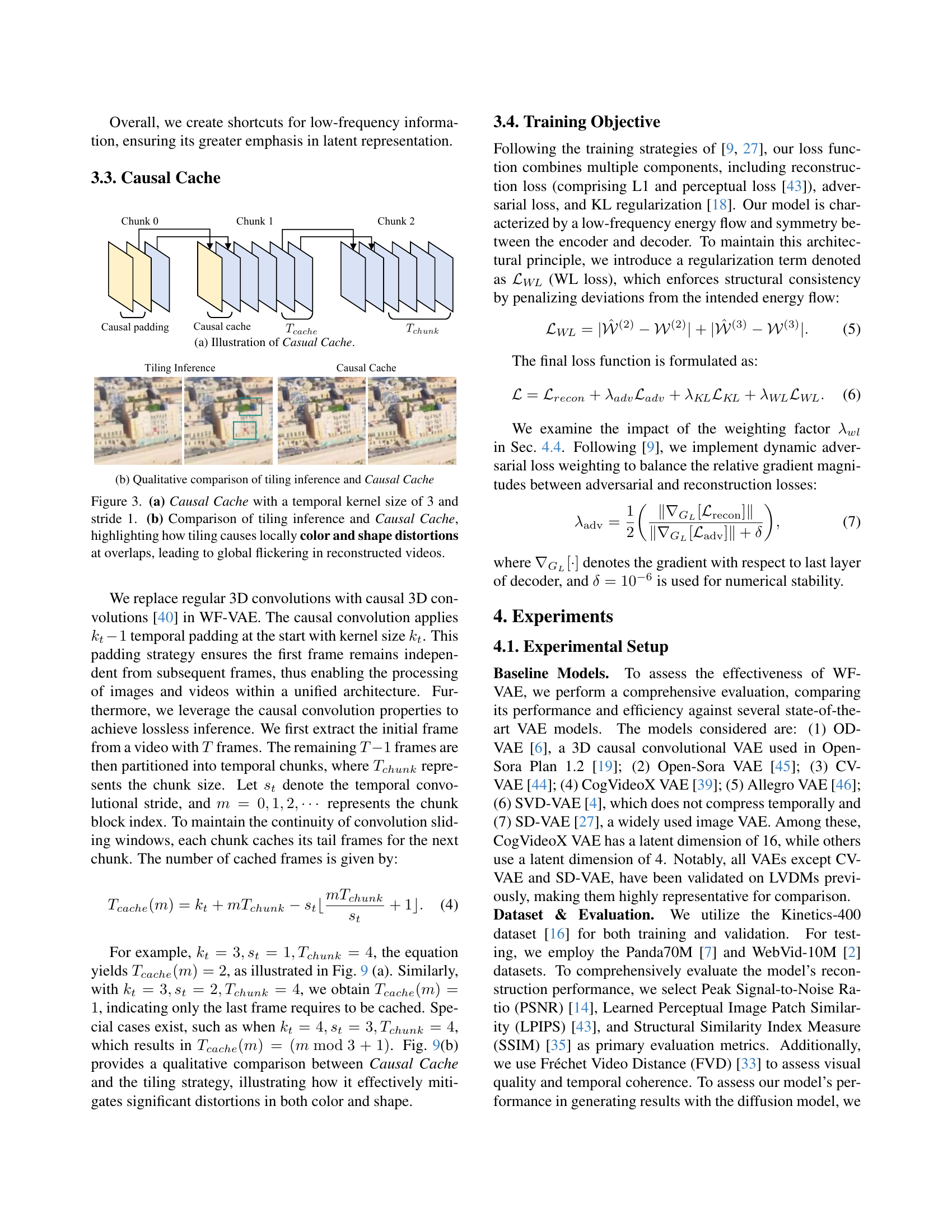

🔼 This figure illustrates the Causal Cache mechanism, which is a novel approach to maintaining the integrity of the latent space during block-wise inference in video VAEs. It shows how the Causal Cache, with a temporal kernel size of 3 and stride 1, handles the overlap between chunks of video frames by caching the tail frames of the current chunk for processing in the next chunk. This ensures that the convolution sliding window maintains continuity, preventing discontinuities and artifacts in the reconstructed videos.

read the caption

(a) Illustration of Casual Cache.

🔼 This figure compares the tiling inference method and the Causal Cache method proposed in the paper. It visually demonstrates the differences in the reconstruction results, showing how tiling inference leads to distortions and artifacts at the overlaps of video chunks due to discontinuity issues, while the Causal Cache method successfully maintains the integrity of the reconstructed video by utilizing a caching strategy that preserves continuity of the convolution sliding window across chunks.

read the caption

(b) Qualitative comparison of tiling inference and Causal Cache

🔼 Figure 3 illustrates the Causal Cache mechanism proposed for handling the temporal dimension of video data. (a) shows a diagram of Causal Cache with a temporal kernel size of 3 and a stride of 1. This demonstrates how the mechanism maintains temporal continuity by using causal convolution and caching the tail frames of previous chunks. (b) presents a qualitative comparison between tiling inference (standard method) and Causal Cache. The comparison highlights how tiling inference introduces local color and shape distortions at the overlap between consecutive blocks, causing global flickering in the reconstructed videos. Causal Cache overcomes these issues by maintaining the integrity of the latent video representation.

read the caption

Figure 3: (a) Causal Cache with a temporal kernel size of 3 and stride 1. (b) Comparison of tiling inference and Causal Cache, highlighting how tiling causes locally color and shape distortions at overlaps, leading to global flickering in reconstructed videos.

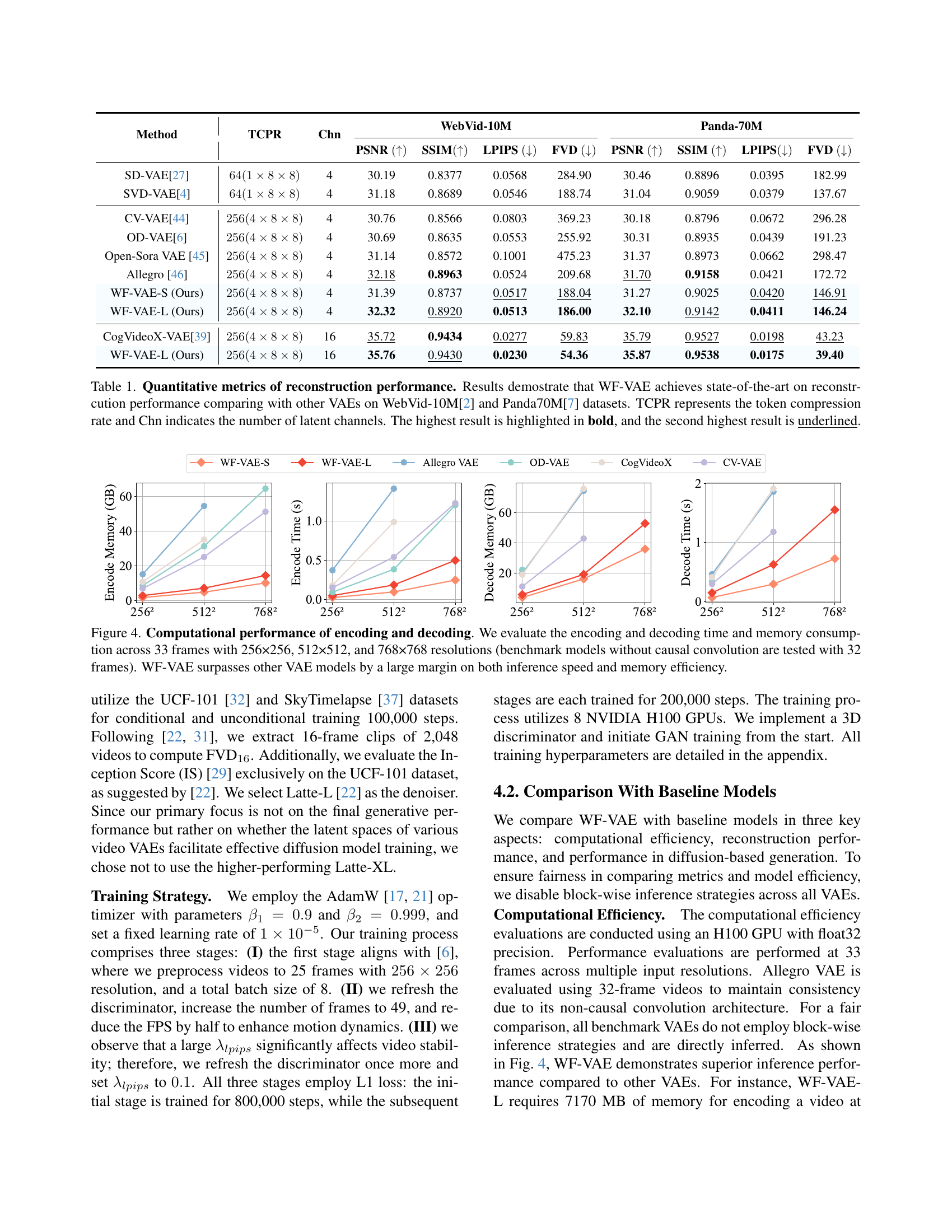

🔼 This figure compares the computational performance (encoding and decoding time, memory usage) of different video Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for videos of varying resolutions (256x256, 512x512, and 768x768 pixels) and lengths (33 frames for most models; 32 frames for models without causal convolution). The results show that WF-VAE significantly outperforms other VAEs in terms of both speed and memory efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 4: Computational performance of encoding and decoding. We evaluate the encoding and decoding time and memory consumption across 33 frames with 256×256, 512×512, and 768×768 resolutions (benchmark models without causal convolution are tested with 32 frames). WF-VAE surpasses other VAE models by a large margin on both inference speed and memory efficiency.

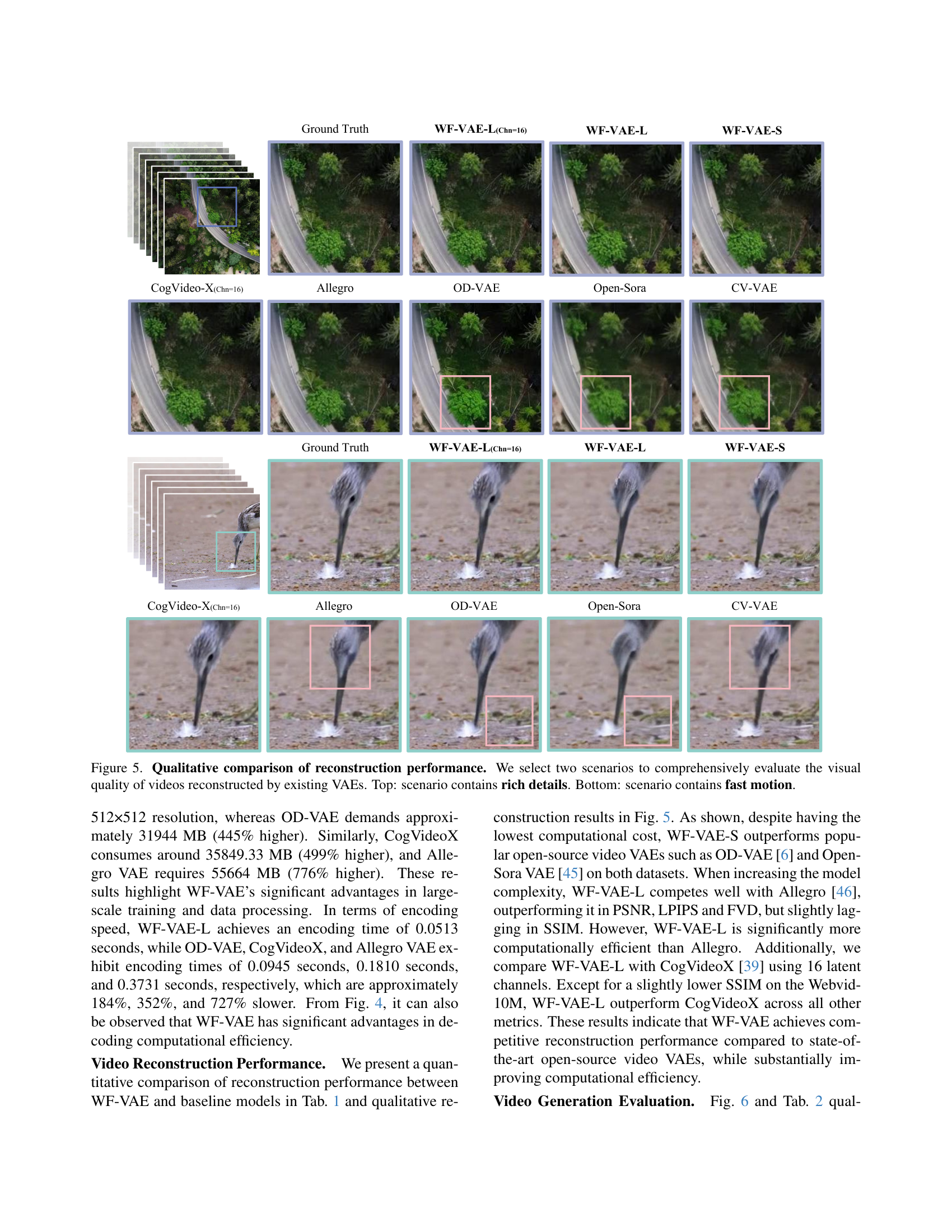

🔼 This figure showcases a qualitative comparison of video reconstruction quality between WF-VAE and other state-of-the-art video VAEs. Two distinct video scenarios are presented: one rich in detail and the other featuring fast motion. The results visually demonstrate WF-VAE’s superior performance in reconstructing both types of video content, highlighting its ability to preserve fine details and handle temporal changes effectively.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative comparison of reconstruction performance. We select two scenarios to comprehensively evaluate the visual quality of videos reconstructed by existing VAEs. Top: scenario contains rich details. Bottom: scenario contains fast motion.

🔼 This figure displays generated video results from the WF-VAE model, utilized with the Latte-L diffusion model. The top row showcases videos generated using WF-VAE trained on the SkyTimelapse dataset, while the bottom row shows videos generated using WF-VAE trained on the UCF-101 dataset. This comparison demonstrates the impact of different training data on the quality and style of the generated videos. The figure highlights the model’s ability to generate diverse video content based on the training data.

read the caption

Figure 6: Generated videos using WF-VAE with Latte-L. Top: results trained with the SkyTimelapse dataset. Bottom: results trained with the UCF-101 dataset.

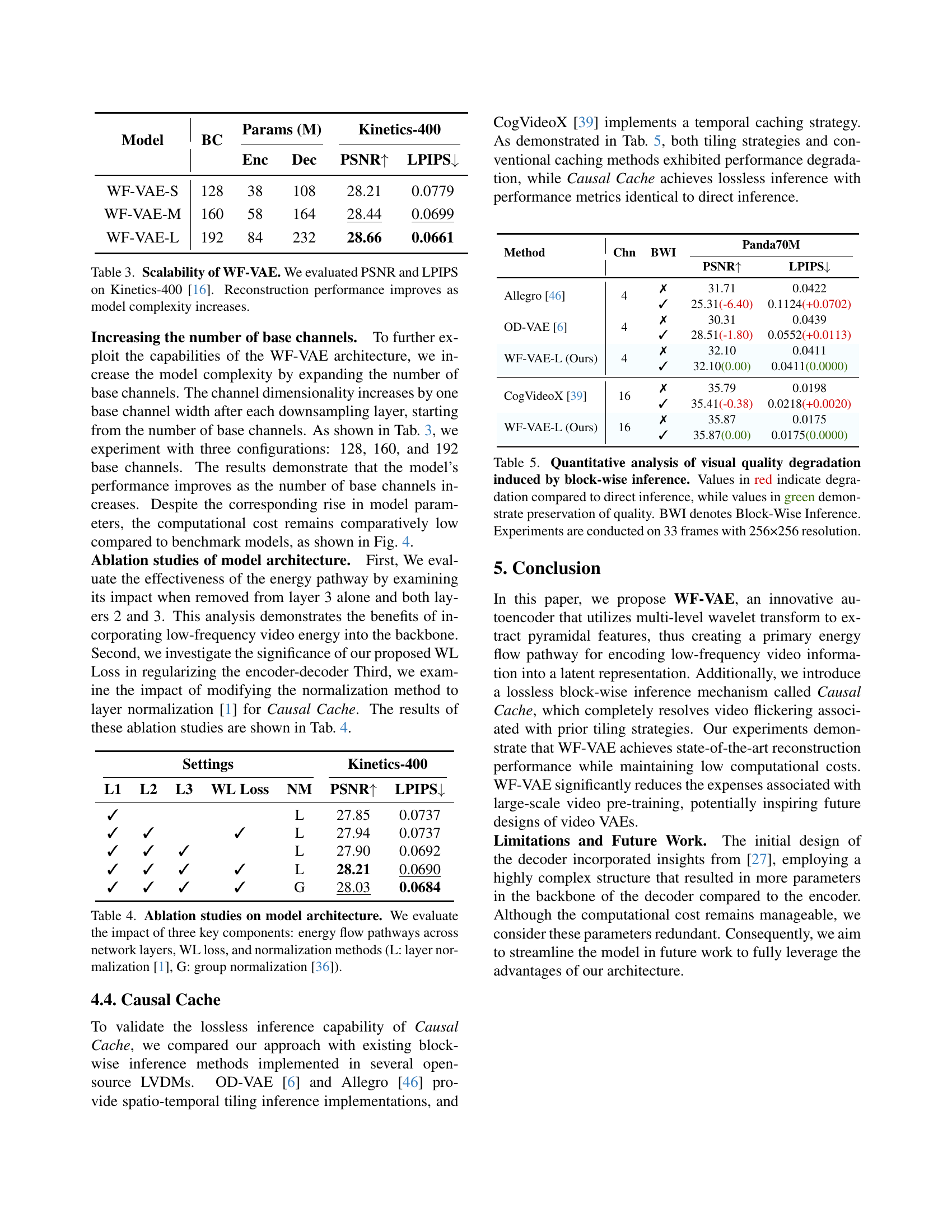

🔼 This figure shows the impact of varying the number of latent channels on the model’s performance. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis displays the validation PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity) metrics. Multiple lines are plotted, each corresponding to a different number of latent channels (4, 8, 16, and 32). This visualization helps to understand how the model’s reconstruction quality and perceptual similarity improve as the number of latent channels increases.

read the caption

(a) Number of latent channels.

🔼 The figure shows the impact of different weighting factors (λWLsubscript𝜆𝑊𝐿 λ_{W L}) for the WL loss on the model’s performance. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis shows the validation performance metrics (PSNR and LPIPS). Each line represents a different weight assigned to the WL loss. The plot helps in understanding the effect of this regularization term in balancing the reconstruction quality and structural consistency of the energy flow in the model.

read the caption

(b) WL Loss weights λWLsubscript𝜆𝑊𝐿\lambda_{W\!L}italic_λ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_W italic_L end_POSTSUBSCRIPT.

🔼 This ablation study shows how the number of channels in the energy flow pathway, denoted as Cflow, affects the model’s performance. The energy flow pathway is a key component of the WF-VAE architecture, designed to efficiently transfer low-frequency information to the latent representation. By varying Cflow (64, 128, 256), the experiment investigates the optimal balance between preserving low-frequency detail and maintaining computational efficiency. The results indicate an optimal value for Cflow that balances reconstruction quality and computational cost.

read the caption

(c) Number of energy flow path channels Cflowsubscript𝐶𝑓𝑙𝑜𝑤C_{flow}italic_C start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_f italic_l italic_o italic_w end_POSTSUBSCRIPT.

🔼 This figure visualizes the training dynamics of the WF-VAE model under various experimental conditions. It shows how key performance metrics (PSNR and LPIPS) evolve during training as hyperparameters are changed. Specifically, it analyzes the effects of varying the number of latent channels, the weight of the WL loss (a regularization term that enforces structural consistency in the model), and the number of channels in the main energy flow pathway. Each subfigure illustrates the change of PSNR and LPIPS with respect to training steps.

read the caption

Figure 7: Training dynamics under different settings.

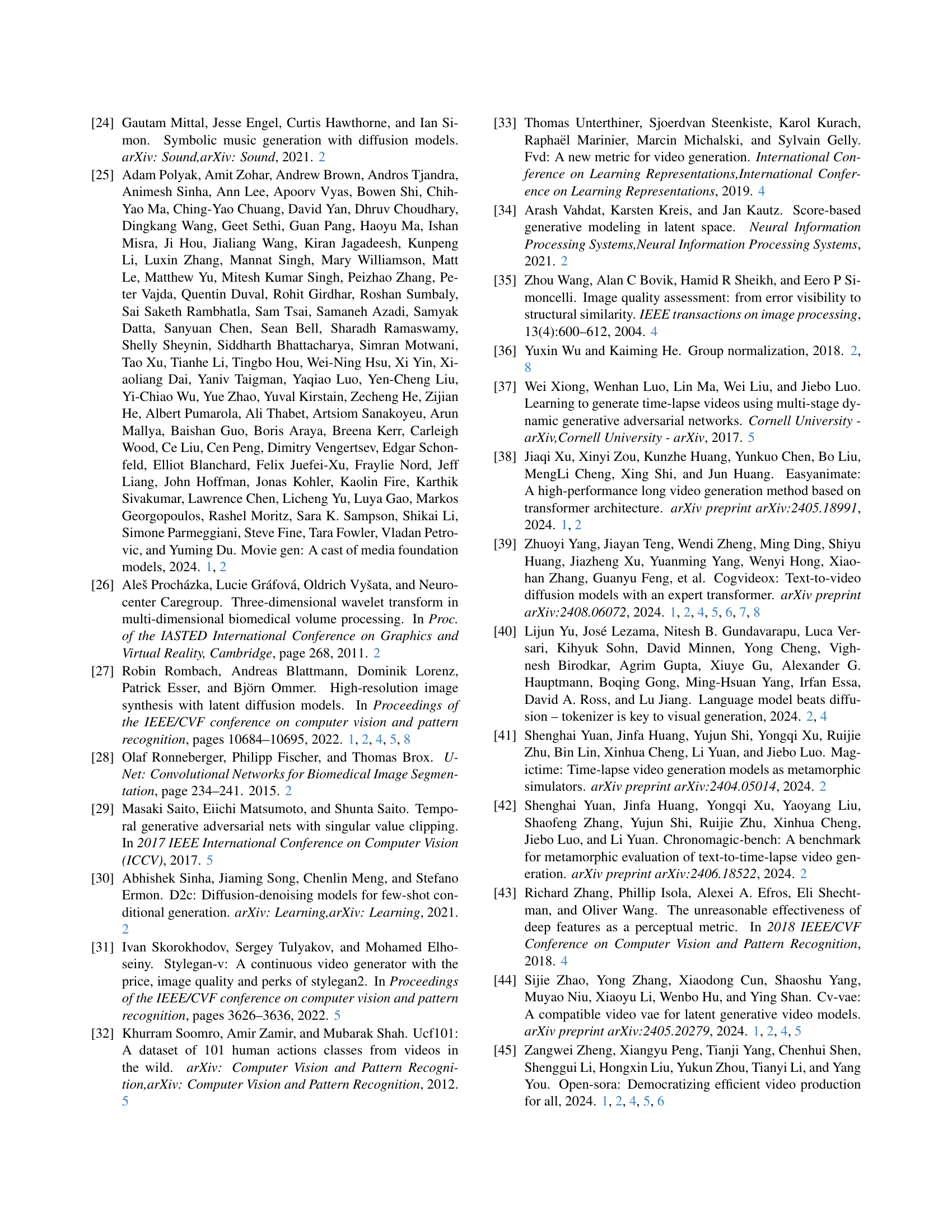

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of a multi-level Haar wavelet transform applied to a video frame. The wavelet transform decomposes the video frame into eight frequency subbands, each representing different aspects of the video’s frequency content. These subbands are shown in a 2x4 grid, allowing for a visual comparison of their respective energy and entropy levels. The subbands reveal a hierarchical decomposition of the video frame, with the top-left subband containing the low-frequency components (approximation coefficients) and the other subbands containing progressively higher-frequency components (detail coefficients).

read the caption

(a) Visualization of the eight subbands obtained after wavelet transform of the video.

🔼 This figure shows a bar chart visualizing the energy and entropy distribution across different subbands obtained after applying a wavelet transform to video data. The subbands represent different frequency components of the video signal. The chart highlights the concentration of energy and entropy within specific subbands, particularly the low-frequency components, providing visual evidence for the paper’s focus on efficient encoding of crucial video information.

read the caption

(b) Energy and entropy of each subband.

🔼 Figure 8 displays two subplots that illustrate the energy and entropy distribution across the various subbands obtained from a wavelet transform of a video. The top subplot presents a visualization of the eight subbands resulting from the decomposition, while the bottom subplot shows the logarithmic scale of the energy and the entropy of each subband. This visualization helps demonstrate that most of the video’s energy and information is concentrated within the low-frequency subband (hhh), which is crucial for understanding the rationale behind the WF-VAE model’s architecture and its decision to prioritize this subband during video encoding.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visualization of the subbands and their respective energy and entropy.

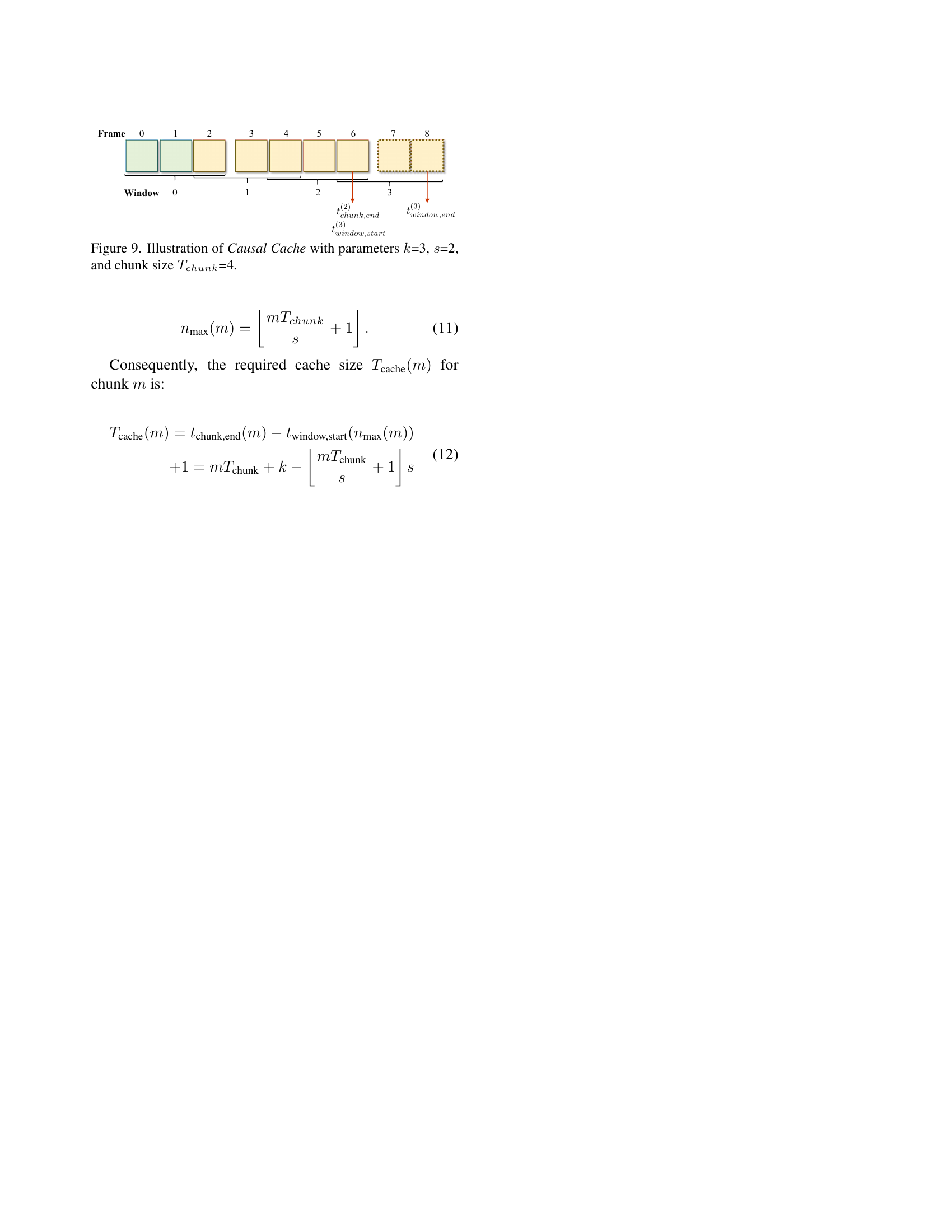

🔼 Figure 9 illustrates the Causal Cache mechanism used for efficient and continuous video processing. It shows how, with a kernel size (k) of 3 and a stride (s) of 2, the system processes video frames in chunks of size 4 (Tchunk). Each chunk overlaps with the preceding chunk by caching a specific number of frames (Tcache) to ensure smooth transitions and prevent discontinuities. This method is crucial for maintaining the integrity of latent space during block-wise inference, which is vital for high-quality video reconstruction. The diagram visually depicts how the cached frames bridge the gap between successive chunks, demonstrating the mechanism’s ability to provide continuous video processing despite the block-wise strategy.

read the caption

Figure 9: Illustration of Causal Cache with parameters k𝑘kitalic_k=3, s𝑠sitalic_s=2, and chunk size Tchunksubscript𝑇𝑐ℎ𝑢𝑛𝑘T_{chunk}italic_T start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_c italic_h italic_u italic_n italic_k end_POSTSUBSCRIPT=4.

More on tables

| Method | Chn | SkyTimelapse | UCF101 FVD↓ | UCF101 IS↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegro [46] | 4 | 117.28 | 1045.66 | 67.16 |

| OD-VAE [6] | 4 | 130.79 | 1109.87 | 58.48 |

| WF-VAE-S (Ours) | 4 | 103.44 | 1005.10 | 65.89 |

| WF-VAE-L (Ours) | 4 | 113.67 | 929.55 | 70.53 |

| CogVideoX [39] | 16 | 109.20 | 1117.57 | 57.47 |

| WF-VAE-L (Ours) | 16 | 108.69 | 947.18 | 71.86 |

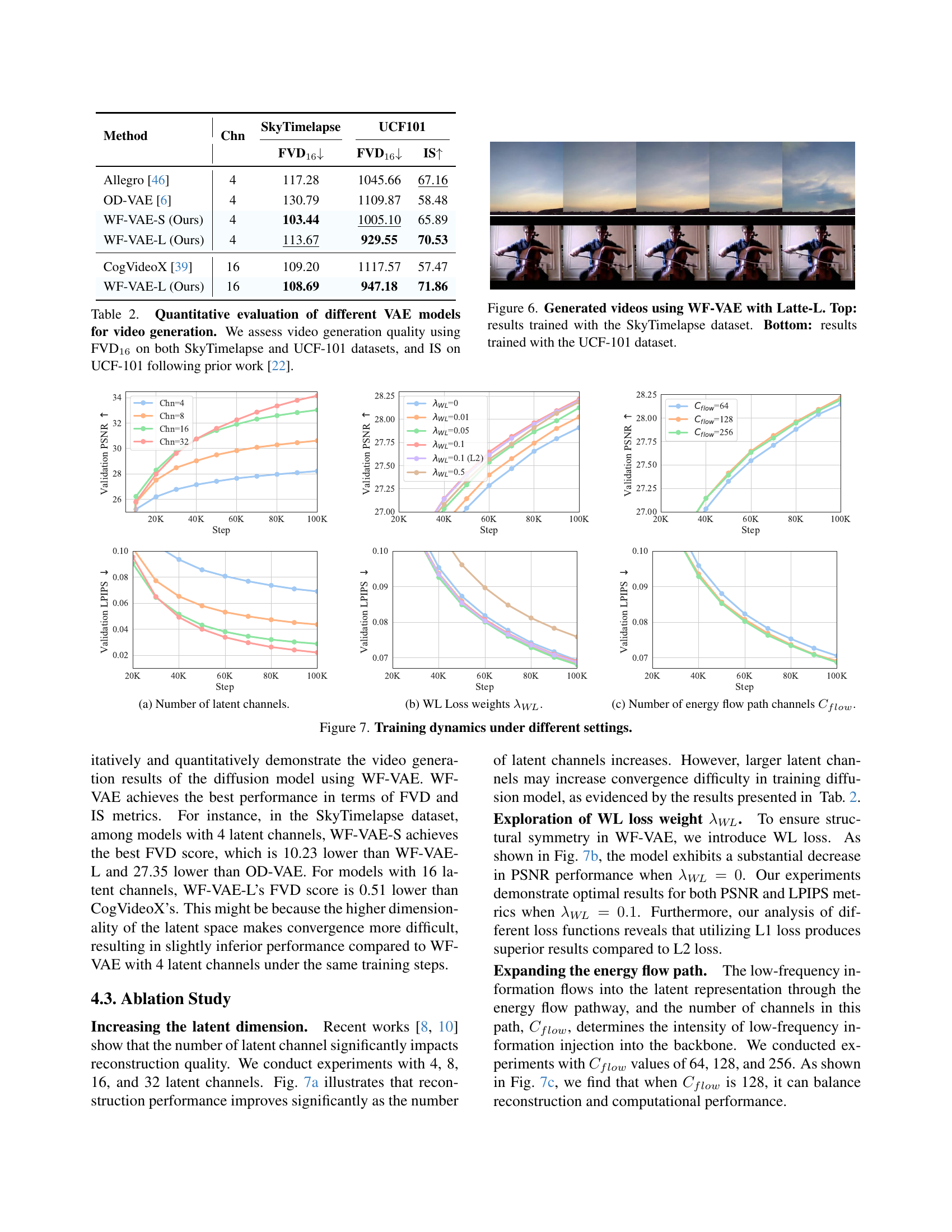

🔼 Table 2 presents a quantitative comparison of various Video Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) in terms of their video generation capabilities. The evaluation focuses on two metrics: Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) at 16 frames (FVD16) and Inception Score (IS). FVD16 measures the visual quality and temporal coherence of generated videos, while IS assesses the diversity and quality of the generated samples. The results are shown for two benchmark datasets: SkyTimelapse and UCF-101. For the UCF-101 dataset, both FVD16 and IS scores are reported. The table helps to understand how well different VAEs generate videos and their performance relative to each other.

read the caption

Table 2: Quantitative evaluation of different VAE models for video generation. We assess video generation quality using FVD16 on both SkyTimelapse and UCF-101 datasets, and IS on UCF-101 following prior work [22].

| Model | BC | Params (M) Enc | Params (M) Dec | Kinetics-400 PSNR↑ | Kinetics-400 LPIPS↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF-VAE-S | 128 | 38 | 108 | 28.21 | 0.0779 |

| WF-VAE-M | 160 | 58 | 164 | 28.44 | 0.0699 |

| WF-VAE-L | 192 | 84 | 232 | 28.66 | 0.0661 |

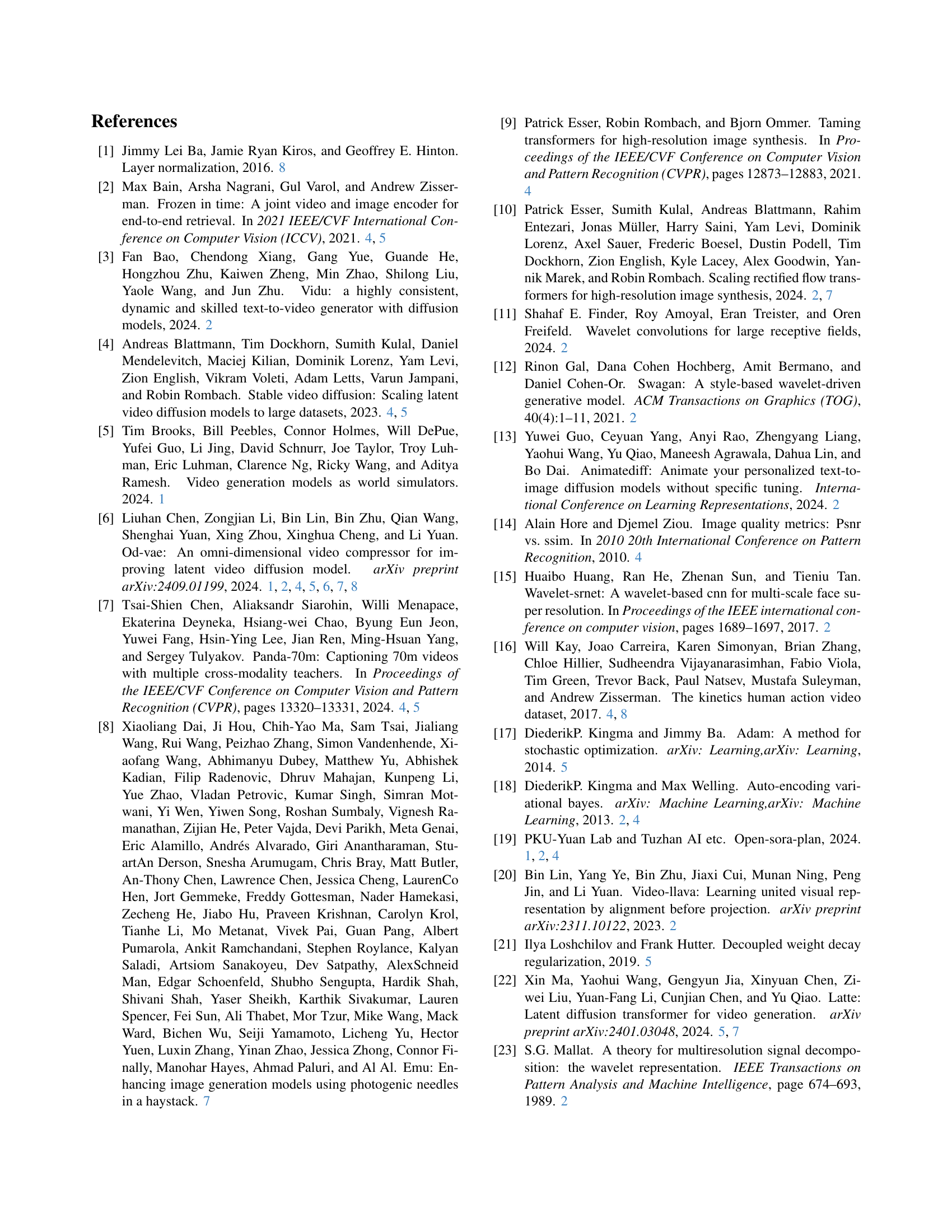

🔼 This table presents the scalability results of the WF-VAE model. The experiment evaluates the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and the Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) metrics on the Kinetics-400 dataset. Three different configurations of the WF-VAE model were tested, each differing in the number of base channels (128, 160, and 192). The results demonstrate that the model’s reconstruction performance improves as model complexity, measured by the number of base channels, increases. The table helps to illustrate the trade-offs between model size and performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Scalability of WF-VAE. We evaluated PSNR and LPIPS on Kinetics-400 [16]. Reconstruction performance improves as model complexity increases.

| Settings | Kinetics-400 | |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 |

| ✓ | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

🔼 This table presents an ablation study analyzing the impact of three key architectural components of the WF-VAE model on its performance. The components are: 1) the energy flow pathways connecting low-frequency information to the latent representation, 2) the weight of the WL loss (which regularizes the model’s energy flow), and 3) the type of normalization used (layer normalization [1] vs. group normalization [36]). The results are shown in terms of PSNR and LPIPS metrics on the Kinetics-400 dataset, demonstrating the contribution of each component to overall reconstruction quality.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation studies on model architecture. We evaluate the impact of three key components: energy flow pathways across network layers, WL loss, and normalization methods (L: layer normalization [1], G: group normalization [36]).

| Method | Chn | BWI | Panda70M PSNR↑ | Panda70M LPIPS↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✗ | 31.71 | 0.0422 | ||

| Allegro [46] | 4 | ✓ | 25.31 (-6.40) | 0.1124 (+0.0702) |

| ✗ | 30.31 | 0.0439 | ||

| OD-VAE [6] | 4 | ✓ | 28.51 (-1.80) | 0.0552 (+0.0113) |

| ✗ | 32.10 | 0.0411 | ||

| WF-VAE-L (Ours) | 4 | ✓ | 32.10 (0.00) | 0.0411 (0.0000) |

| CogVideoX [39] | 16 | ✗ | 35.79 | 0.0198 |

| ✓ | 35.41 (-0.38) | 0.0218 (+0.0020) | ||

| ✗ | 35.87 | 0.0175 | ||

| WF-VAE-L (Ours) | 16 | ✓ | 35.87 (0.00) | 0.0175 (0.0000) |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of visual quality when using block-wise inference versus direct inference in video variational autoencoders (VAEs). The metrics evaluated are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS). Positive differences from direct inference results (shown in green) indicate that block-wise inference preserves quality, while negative differences (shown in red) highlight quality degradation introduced by block-wise inference. The experiments are conducted on videos with 33 frames and 256x256 resolution.

read the caption

Table 5: Quantitative analysis of visual quality degradation induced by block-wise inference. Values in red indicate degradation compared to direct inference, while values in green demonstrate preservation of quality. BWI denotes Block-Wise Inference. Experiments are conducted on 33 frames with 256×256 resolution.

| Notations | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Wavelet transform | |

| Inverse wavelet transform | |

| Wavelet subband within layer , where specifies the type of filtering (high or low pass) applied in three dimensions. | |

| The set of all subbands within layer |

🔼 This table lists notations used in the paper along with their corresponding descriptions. It serves as a quick reference for readers to understand the meaning of symbols and abbreviations used throughout the paper.

read the caption

Table 6: Notations symbols and their descriptions.

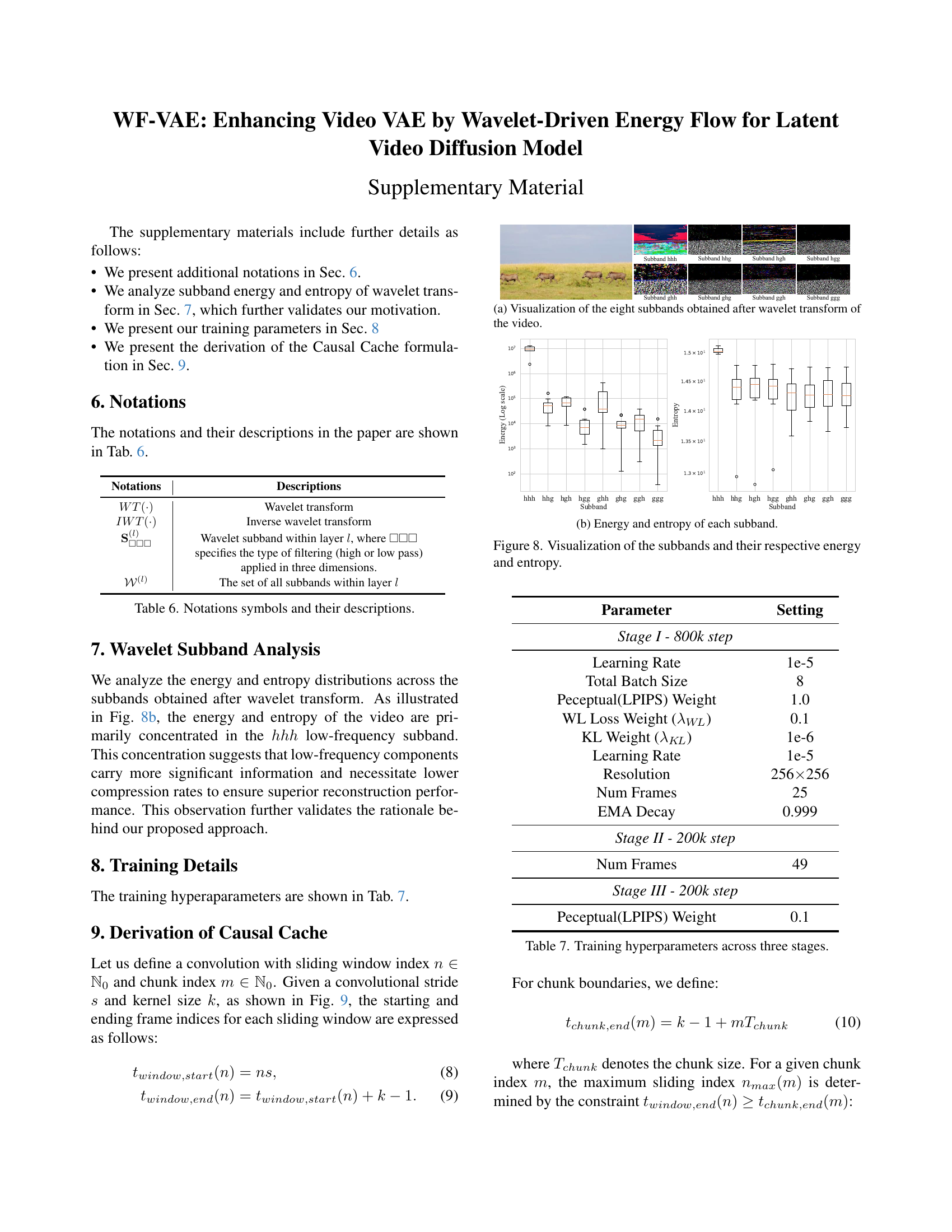

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Stage I - 800k step | |

| Learning Rate | 1e-5 |

| Total Batch Size | 8 |

| Peceptual(LPIPS) Weight | 1.0 |

| WL Loss Weight (λWL) | 0.1 |

| KL Weight (λKL) | 1e-6 |

| Learning Rate | 1e-5 |

| Resolution | 256 × 256 |

| Num Frames | 25 |

| EMA Decay | 0.999 |

| Stage II - 200k step | |

| Num Frames | 49 |

| Stage III - 200k step | |

| Peceptual(LPIPS) Weight | 0.1 |

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used during the training process of the WF-VAE model. The training is divided into three stages, each with its own set of hyperparameters. The parameters include the learning rate, batch size, weights for different loss functions (perceptual loss, KL divergence, and the custom WL loss), resolution of the input videos, number of frames, and EMA decay rate. Understanding these settings is key to replicating the training process and analyzing the model’s performance across the different stages.

read the caption

Table 7: Training hyperparameters across three stages.

Full paper#