↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Many existing GUI assistants rely on language-based approaches and closed-source APIs, limiting their ability to perceive and interact with UI visuals like humans. This paper addresses these limitations by introducing ShowUI, a vision-language-action model for GUI visual agents. The main challenges the paper tackles are the high computational cost of processing high-resolution screenshots and the difficulty in effectively managing interleaved vision-language-action sequences within GUI tasks. There’s also the issue of a lack of high-quality training datasets, which hinders the development of robust models.

ShowUI overcomes these challenges with three key innovations: UI-Guided Visual Token Selection to reduce redundancy, Interleaved Vision-Language-Action Streaming to efficiently manage diverse tasks, and a carefully curated, high-quality dataset. The results demonstrate ShowUI’s superior performance in zero-shot screenshot grounding and navigation across various GUI environments. Its lightweight design (2B parameters, 256K training data) makes it computationally efficient and demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed techniques. The paper contributes a valuable benchmark dataset and opens new avenues for research in building more effective and efficient GUI visual agents.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the challenges of building efficient and effective GUI visual agents. It introduces novel techniques for visual token selection and interleaved vision-language-action streaming, significantly improving model efficiency and performance. The high-quality dataset and benchmark it provides are also valuable resources for future research in this area, potentially leading to advancements in human-computer interaction and workflow automation.

Visual Insights#

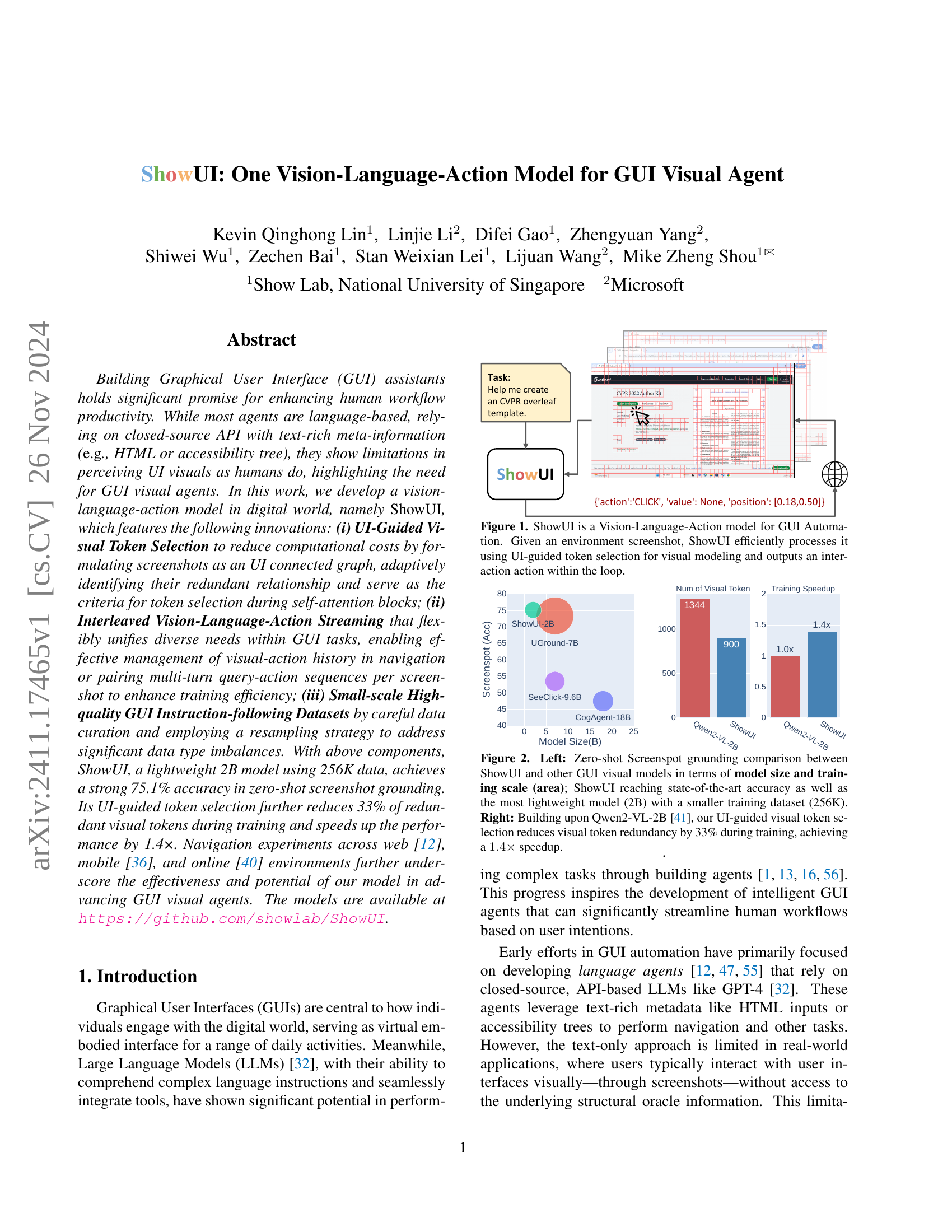

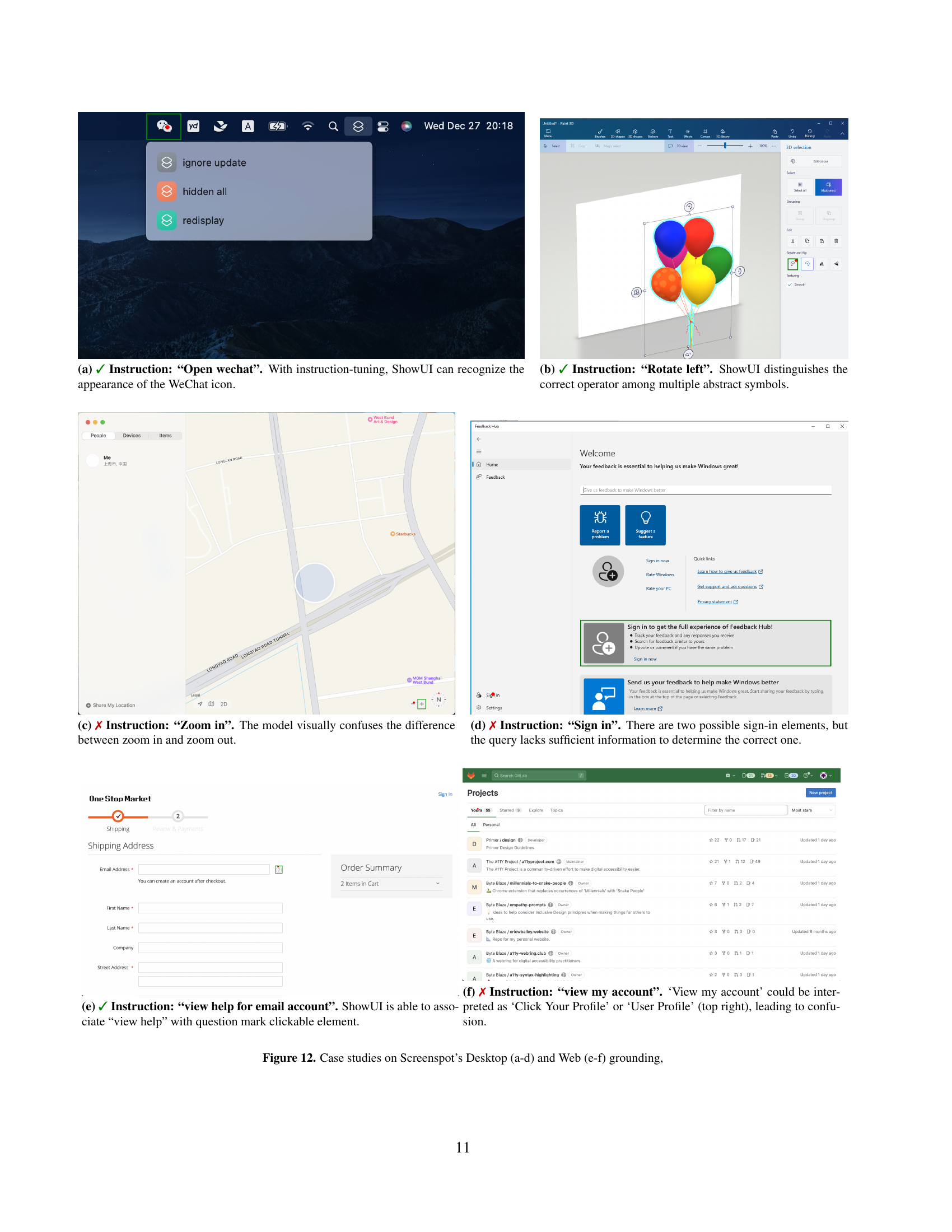

🔼 ShowUI is a vision-language-action model designed for automating interactions with graphical user interfaces (GUIs). The figure illustrates the model’s workflow: it takes an environment screenshot as input. Then, through a process of UI-guided token selection (a technique that optimizes processing by focusing on relevant visual elements), it analyzes the screenshot and generates an appropriate interaction action (like a click or text input). This action is then fed back into the system to continue the automation loop.

read the caption

Figure 1: ShowUI is a Vision-Language-Action model for GUI Automation. Given an environment screenshot, ShowUI efficiently processes it using UI-guided token selection for visual modeling and outputs an interaction action within the loop.

| Usage | Device | Source | #Sample | #Ele. | #Cls. (len.) | Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grounding | Web | Self-collected | 22K | 576K | N/A | Visual-based |

| Mobile | AMEX [8] | 97K | 926K | N/A | Functionality | |

| Desktop | OmniAct [22] | 100 | 8K | N/A | Diverse query | |

| Navigation | Web | GUIAct [10] | 72K | 569K | 9 (7.9) | One / Multi-step |

| Mobile | GUIAct [10] | 65K | 585K | 5 (9.0) | Multi-step | |

| Total | Diverse | 256K | 2.7M |

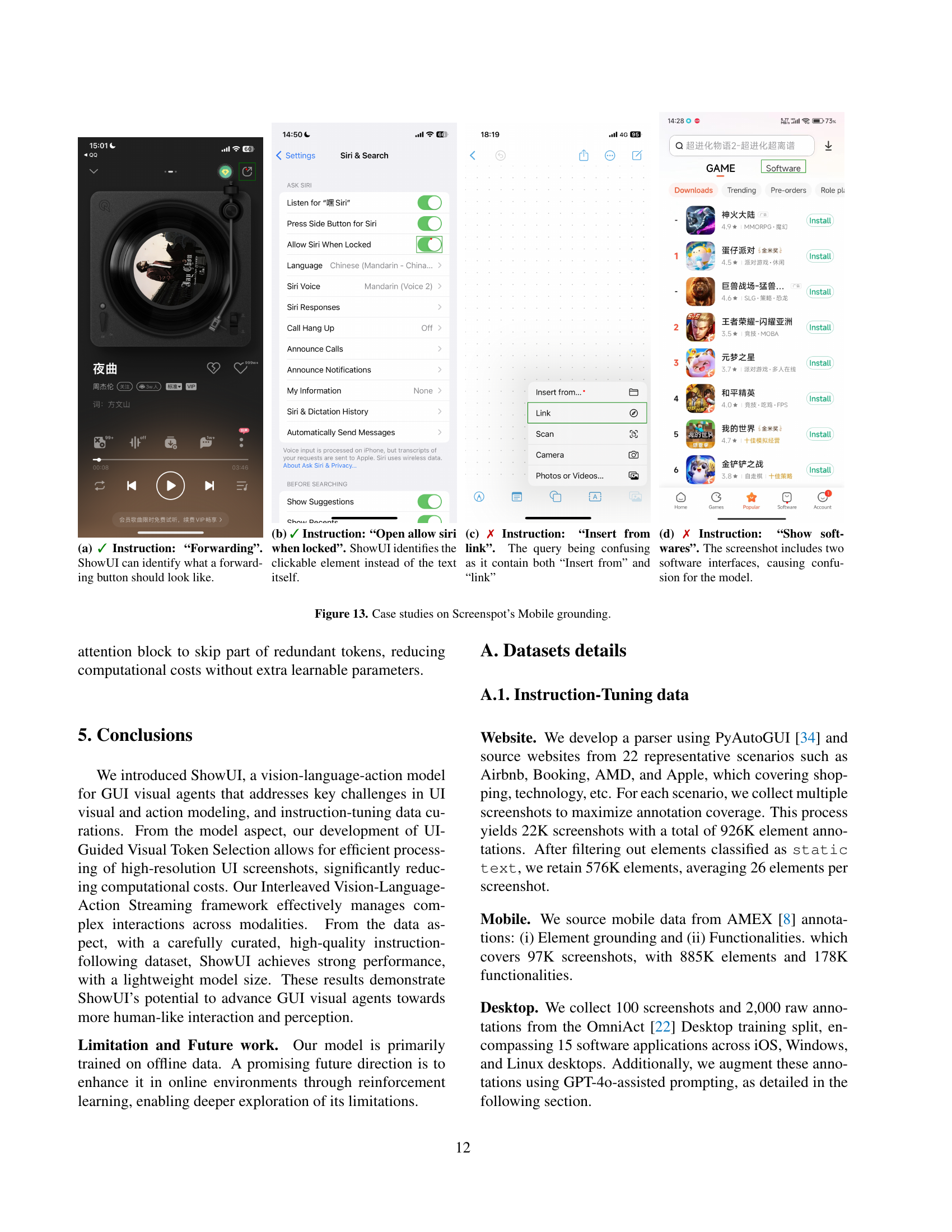

🔼 This table summarizes the datasets used for instruction tuning in the ShowUI model. It details the source of each dataset (Web, Mobile, Desktop), the number of samples (task instances; screenshots for grounding, tasks for navigation), the number of elements (bounding boxes for grounding), the number of action classes, and the average length of action trajectories per task. The dataset is split into grounding and navigation tasks, with different metrics relevant to each.

read the caption

Table 1: Overview of our instruction-tuning data. #Sample indicates the number of the task instance (screenshot in grounding, task in navigation); #Ele. indicates the number of the element (i.e., bbox in grounding); #Cls. represents the number of action classes, and len. indicates the average trajectory length per task.

In-depth insights#

UI-Guided Vision#

A hypothetical ‘UI-Guided Vision’ section in a research paper would likely explore how visual information is processed within the context of graphical user interfaces (GUIs). This would go beyond general image processing, focusing on the unique characteristics of UI elements: their structure, layout, and consistent design patterns. The core idea would likely involve developing algorithms to selectively focus on relevant visual elements while filtering out irrelevant background noise. Techniques like connected component analysis could be applied to group similar visual patches into meaningful units, thus reducing computational costs and improving efficiency. The system would likely need to learn to discriminate between essential interactive elements (buttons, text fields) and visually redundant parts of the screenshot. Furthermore, the integration of structural UI information from the accessibility tree or other metadata could enhance the vision model’s performance, establishing a synergy between image processing and structured data. This interplay would be crucial for tasks like UI element localization, visual grounding, or action prediction, ultimately allowing a visual agent to understand and interact with GUIs in a more human-like manner.

Interleaved VLA#

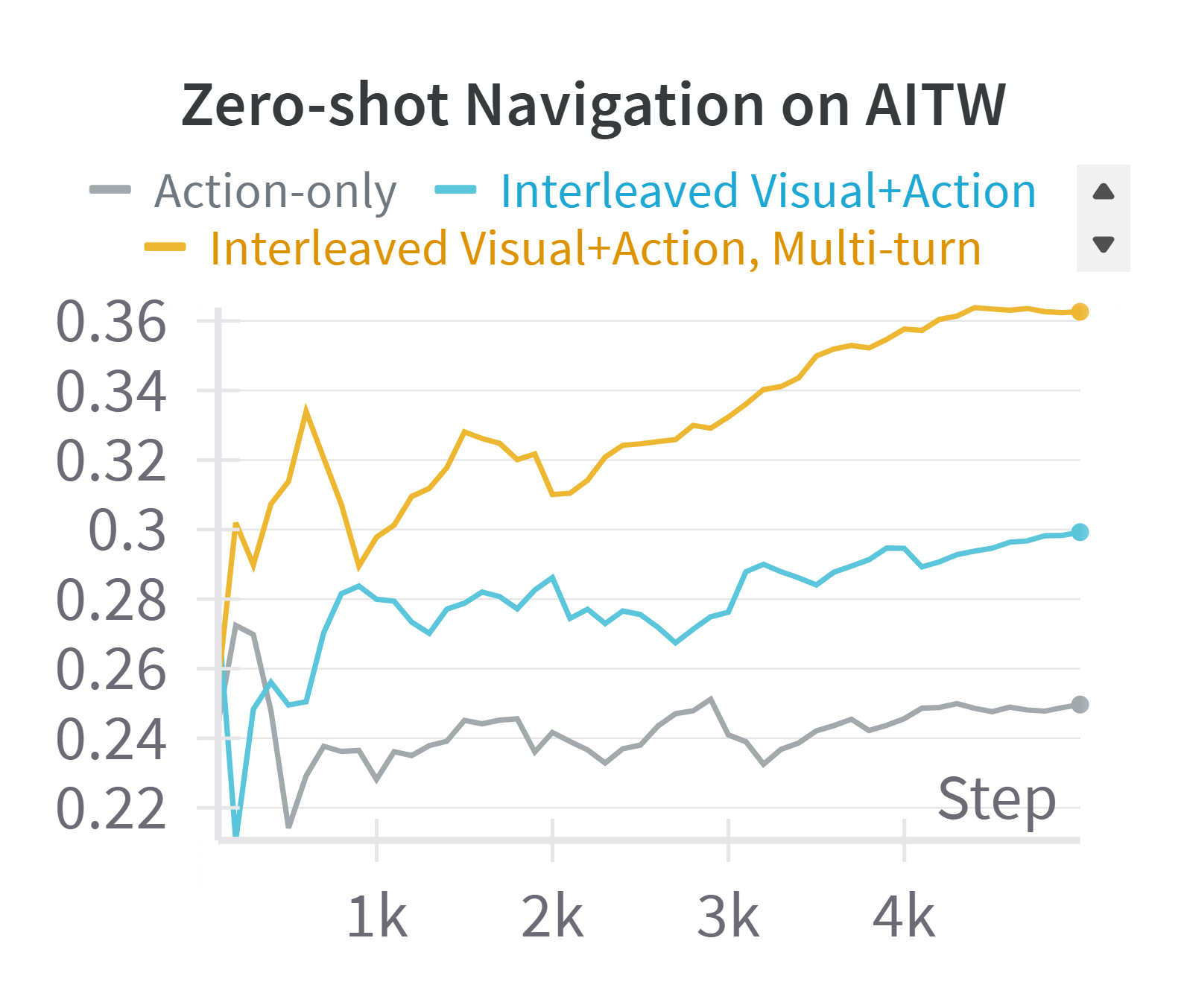

The concept of “Interleaved Vision-Language-Action (VLA)” streaming in the context of GUI agents is crucial for effective model training and performance. It directly addresses the challenge of integrating diverse modalities—visual information from screenshots, textual queries from users, and actions the agent performs—into a unified model. The key insight is that these modalities aren’t independent but intricately linked across time steps. A multi-step interaction involves multiple screenshots, each accompanied by user queries and agent actions. Instead of treating these as separate instances, interleaved VLA streaming processes them sequentially as a unified stream. This allows the model to learn the complex relationships and dependencies between visual observations and actions across the entire task, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to understand and respond appropriately in dynamic GUI environments. The effectiveness of interleaved VLA streaming is further demonstrated by its flexible adaptation to different GUI scenarios. For tasks requiring multiple parallel actions or detailed user interaction, it can be adapted to enhance training efficiency, avoiding the need to force each interaction into a single image.

GUI Datasets#

The effectiveness of any GUI visual agent hinges critically on the quality and diversity of its training data. GUI datasets must capture the multifaceted nature of graphical user interfaces across various platforms (web, mobile, desktop), each with unique visual styles and interaction paradigms. A comprehensive dataset should encompass a broad range of applications and tasks, including navigation, form filling, and element interactions, to ensure the robustness and generalizability of the model. Data imbalances across different GUI types or task complexities are a significant concern; strategies like data augmentation or resampling techniques are needed to address this. High-resolution images are typical of GUI screenshots, posing challenges for visual modeling; solutions such as efficient token selection methods become crucial. Furthermore, annotation quality plays a vital role; inconsistencies in annotation can severely limit model performance. Therefore, a well-curated GUI dataset is not just about scale but also accuracy, diversity, and representational efficiency, crucial factors determining the success of GUI visual agent development.

ShowUI: Model#

The ShowUI model is a novel vision-language-action model designed for GUI visual agent applications. It leverages a lightweight architecture (2B parameters) trained on a comparatively small dataset (256K), yet achieves state-of-the-art performance in zero-shot screenshot grounding (75.1% accuracy). Key to its success are three innovations: UI-Guided Visual Token Selection reduces computational costs by identifying and discarding redundant visual information in screenshots; Interleaved Vision-Language-Action Streaming efficiently manages diverse GUI task needs and unifies visual, textual, and action information; and a carefully curated, high-quality dataset mitigates data imbalance issues common in GUI datasets. ShowUI’s effectiveness extends beyond zero-shot grounding to tasks such as navigation across diverse UI environments (web, mobile, online). The model’s efficiency and strong performance showcase its potential for building robust and scalable GUI visual agents.

Future of GUIs#

The future of GUIs hinges on seamless integration of AI and vision. Current language-based agents, while powerful, are limited by their reliance on textual metadata and lack the visual understanding of humans. Future GUIs will likely incorporate multimodal interfaces that blend natural language processing, computer vision, and direct manipulation of visual elements. UI-guided token selection, as presented in ShowUI, offers one potential path toward efficient visual processing, minimizing redundant data and computation. However, the challenge lies in developing systems that can adapt to varied visual styles and UI designs across different devices and platforms. This necessitates large, high-quality datasets representing the diversity of real-world GUIs, along with novel training techniques for efficient, robust learning. Furthermore, future research must address the inherent complexities of modeling diverse user interactions, and creating agents capable of handling unexpected scenarios not included in their training data. The ultimate goal is a truly intuitive and intelligent GUI assistant that can anticipate user needs, seamlessly adapt to diverse tasks, and enhance human productivity in the digital world.

More visual insights#

More on figures

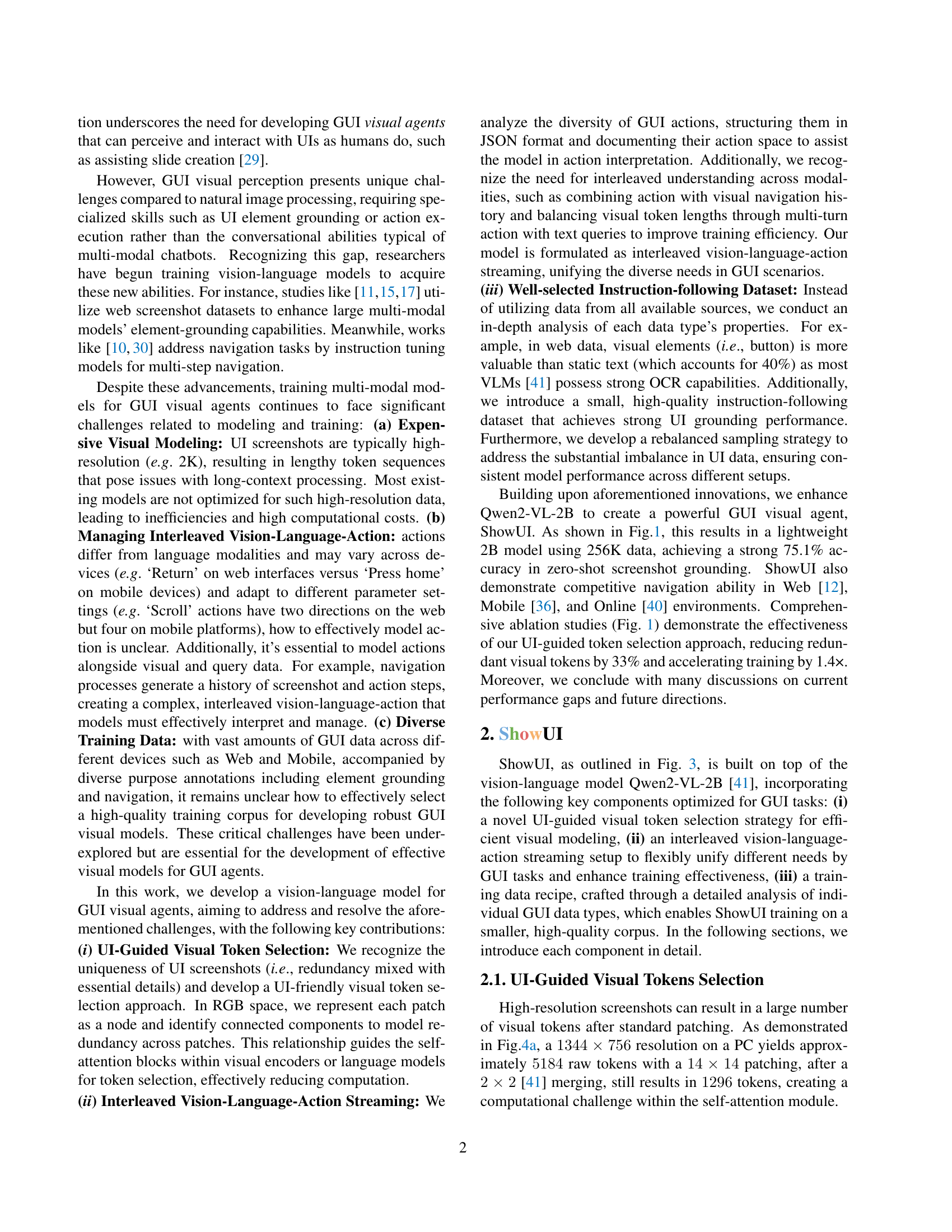

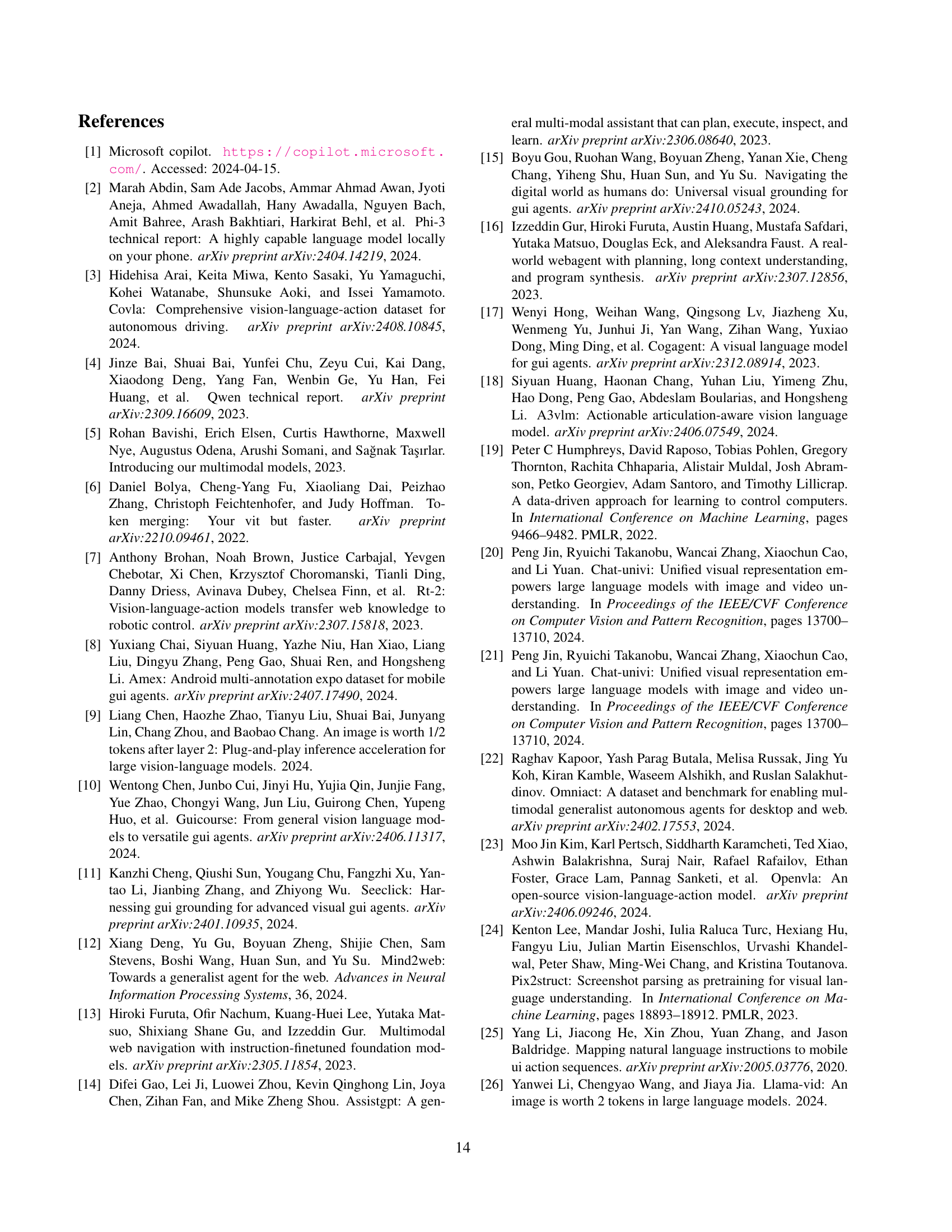

🔼 Figure 2 presents a comparison of ShowUI with other GUI visual models. The left panel shows a scatter plot illustrating the relationship between model size, training dataset size, and zero-shot Screenspot grounding accuracy. ShowUI achieves state-of-the-art accuracy while being significantly more lightweight (2B parameters) and using a smaller training dataset (256K) compared to other models. The right panel demonstrates the impact of ShowUI’s UI-guided token selection. Compared to its base model (Qwen2-VL-2B), ShowUI reduces visual token redundancy by 33% during training, resulting in a 1.4x speedup.

read the caption

Figure 2: Left: Zero-shot Screenspot grounding comparison between ShowUI and other GUI visual models in terms of model size and training scale (area); ShowUI reaching state-of-the-art accuracy as well as the most lightweight model (2B) with a smaller training dataset (256K). Right: Building upon Qwen2-VL-2B [41], our UI-guided visual token selection reduces visual token redundancy by 33% during training, achieving a 1.4×1.4\times1.4 × speedup.

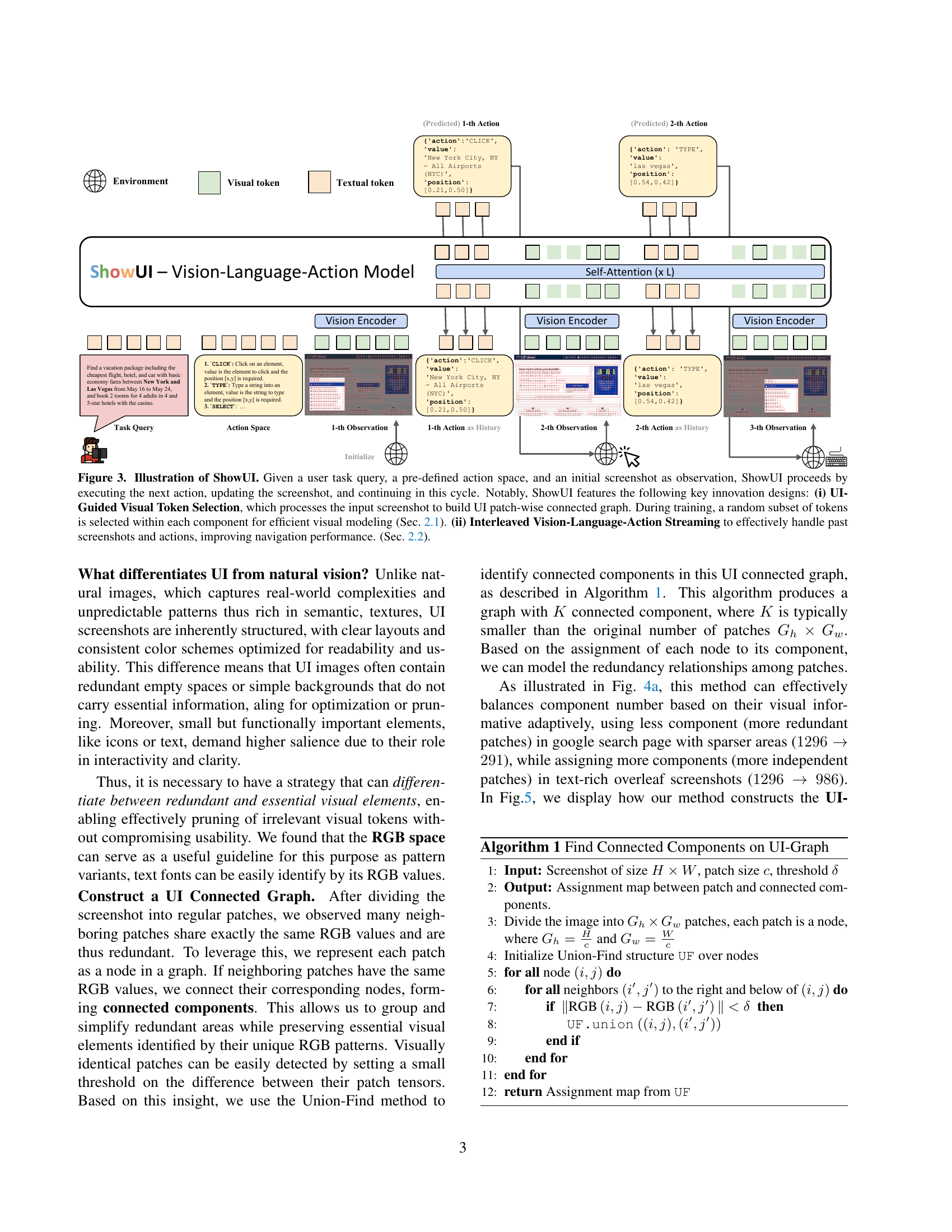

🔼 ShowUI is a vision-language-action model for GUI automation. It takes a user’s task query and an initial screenshot as input. ShowUI then iteratively executes actions, updating the screenshot after each action. This cycle continues until the task is complete. Key innovations include UI-Guided Visual Token Selection (efficiently processing screenshots by creating a UI-connected graph and randomly selecting tokens during training) and Interleaved Vision-Language-Action Streaming (handling past screenshots and actions to improve navigation).

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of ShowUI. Given a user task query, a pre-defined action space, and an initial screenshot as observation, ShowUI proceeds by executing the next action, updating the screenshot, and continuing in this cycle. Notably, ShowUI features the following key innovation designs: (i) UI-Guided Visual Token Selection, which processes the input screenshot to build UI patch-wise connected graph. During training, a random subset of tokens is selected within each component for efficient visual modeling (Sec. 2.1). (ii) Interleaved Vision-Language-Action Streaming to effectively handle past screenshots and actions, improving navigation performance. (Sec. 2.2).

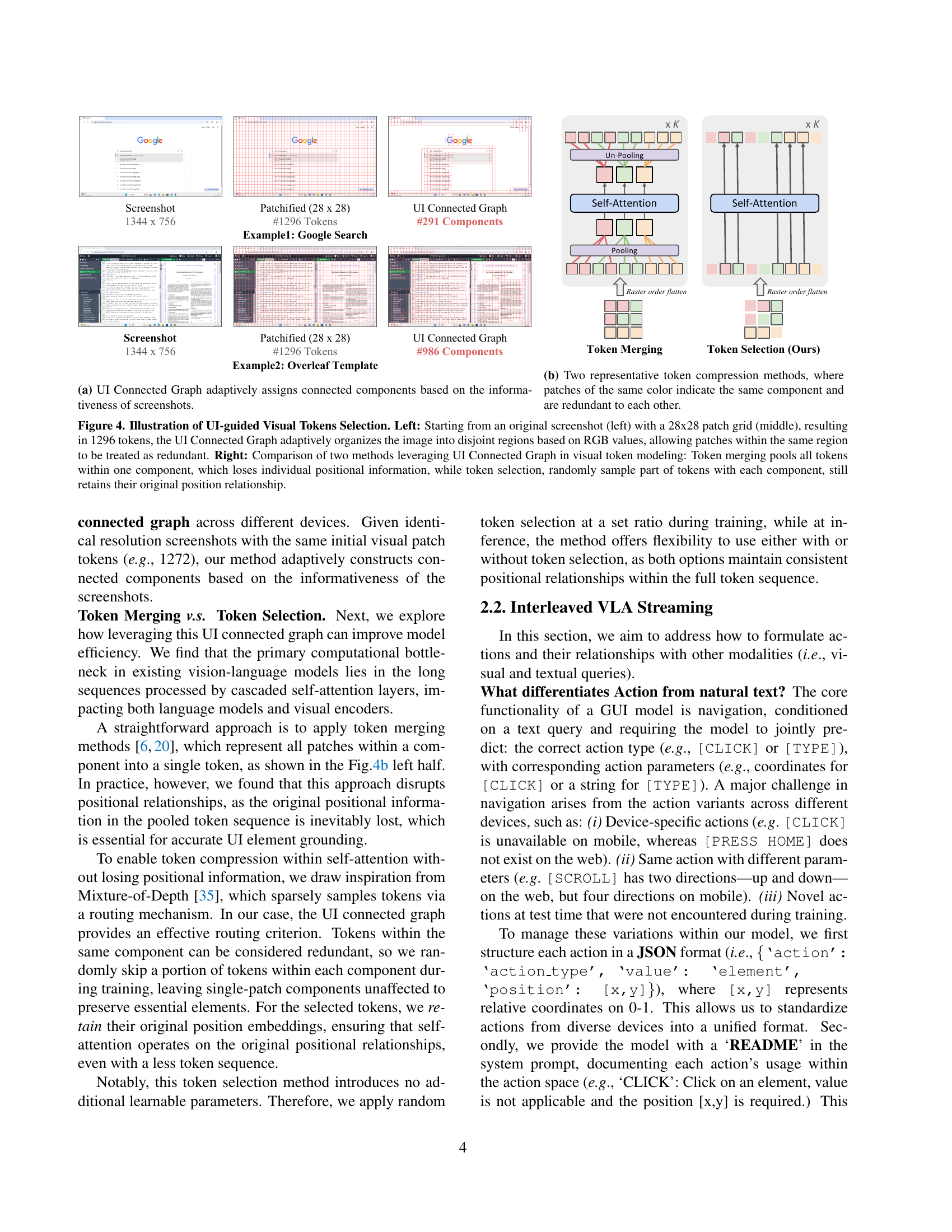

🔼 The figure illustrates how UI-Guided Visual Token Selection works. It shows that the algorithm processes an input screenshot and groups similar pixels together, forming connected components. These components represent regions of the screenshot with similar visual features. This grouping is adaptive and depends on the screenshot’s content; areas with many similar pixels (e.g., background) are collapsed into fewer components, while areas with diverse pixels (e.g., interactive elements) are divided into more components. This method reduces the number of visual tokens needed for processing, improving the model’s efficiency without losing crucial information.

read the caption

(a) UI Connected Graph adaptively assigns connected components based on the informativeness of screenshots.

🔼 This figure compares two methods for visual token compression using a UI-connected graph. The UI-connected graph groups similar image patches together based on their RGB values. Patches of the same color belong to the same component and represent redundant information. The first method, token merging, combines all tokens within a component into a single token, potentially losing spatial information. The second method, token selection, randomly selects a subset of tokens from each component, preserving positional information. This illustration helps explain how the UI-connected graph addresses redundancy in high-resolution screenshots, and how the token selection method is superior to token merging for preserving positional information during the self-attention process.

read the caption

(b) Two representative token compression methods, where patches of the same color indicate the same component and are redundant to each other.

🔼 This figure illustrates the UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method. The left side shows how a screenshot is divided into a 28x28 patch grid, resulting in 1296 tokens. These tokens are then grouped into connected components based on their RGB values using a UI Connected Graph. Patches within the same component are considered redundant. The right side compares two approaches for using the UI Connected Graph: token merging (combining all tokens in a component, losing positional information) and token selection (randomly sampling tokens from each component, preserving positional information).

read the caption

Figure 4: Illustration of UI-guided Visual Tokens Selection. Left: Starting from an original screenshot (left) with a 28x28 patch grid (middle), resulting in 1296 tokens, the UI Connected Graph adaptively organizes the image into disjoint regions based on RGB values, allowing patches within the same region to be treated as redundant. Right: Comparison of two methods leveraging UI Connected Graph in visual token modeling: Token merging pools all tokens within one component, which loses individual positional information, while token selection, randomly sample part of tokens with each component, still retains their original position relationship.

🔼 The figure illustrates the UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method. It starts with a screenshot containing 1272 tokens (after a standard patching process). Using this method, these tokens are grouped into 781 components based on their visual similarity in RGB space. This grouping aims to identify and reduce redundant visual information in the screenshot, which is critical for improving model efficiency. Patches with the same RGB values are grouped into the same components, effectively reducing the computational cost of the self-attention blocks in the visual encoder.

read the caption

(a) 1272 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 781 components

🔼 This figure shows the result of applying UI-Guided Visual Token Selection to a screenshot. The screenshot initially contains 1272 tokens after standard patching. The UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method, described in section 2.1 of the paper, processes the screenshot and groups redundant image patches into connected components. After this process, the number of components is reduced to 359, illustrating the effectiveness of the method in reducing the number of visual tokens that the model needs to process.

read the caption

(b) 1272 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 359 components

🔼 This figure shows the result of applying UI-Guided Visual Token Selection to a screenshot from a mobile device. The original screenshot was initially divided into 1272 visual tokens. After processing with the UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method, these tokens were grouped into 265 connected components. This reduction in the number of tokens is a key aspect of the proposed method, significantly improving the efficiency of the model by reducing redundancy.

read the caption

(c) 1272 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 265 components

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot from a mobile device, specifically illustrating how the UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method reduces the number of tokens required to represent the image. The original screenshot, after patching, results in 1272 tokens. However, by utilizing the UI-connected graph, redundant patches are identified and grouped together, effectively reducing the total number of components (and thus tokens) to 175. This demonstrates the efficiency of the method in reducing computational cost by focusing on only essential visual information.

read the caption

(d) 1272 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 175 components

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot from a PC environment that was initially divided into 646 visual tokens using a 28x28 patch grid. The UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method then grouped these tokens into connected components based on their RGB values. The resulting UI Connected Graph reduced the number of components to 281, thus significantly reducing redundancy in the visual representation.

read the caption

(e) 646 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 281 components

🔼 This figure shows an example of how the UI-connected graph is constructed for a screenshot. The screenshot from a PC application was divided into patches, resulting in 646 tokens. Then, the UI-connected graph method grouped similar patches together into 230 components.

read the caption

(f) 646 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 230 components

🔼 This figure shows an example of how the UI-Connected Graph method constructs a visual representation from a screenshot. Specifically, it demonstrates the process for a web screenshot. Initially, the screenshot is divided into 1296 patches (tokens). The UI-Connected Graph algorithm then groups these patches into 740 connected components based on their RGB values. Patches with similar RGB values are grouped together, representing redundant information. This reduction in the number of components, from 1296 to 740, showcases the effectiveness of the UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method in reducing computational complexity by focusing on visually distinct regions of the screenshot.

read the caption

(g) 1296 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 740 components

🔼 This figure shows the result of applying UI-Guided Visual Token Selection to a web screenshot. Initially, the screenshot is divided into 1296 image patches (tokens). The algorithm then groups similar patches based on their RGB values into connected components. After this process, the screenshot is represented by 369 components, significantly reducing redundancy and computation.

read the caption

(h) 1296 tokens →→\rightarrow→ 369 components

🔼 Figure 5 demonstrates the UI-connected graph construction method used in the ShowUI model. The method leverages the inherent structure of UI screenshots to reduce computational cost by identifying and grouping redundant visual information. Each screenshot is divided into patches, represented as nodes in a graph. Nodes representing patches with similar RGB values are connected, forming connected components. This approach effectively models redundancy in screenshots. The figure shows examples from different device types: (a-d) Mobile, (e-f) PC, and (g-h) Web, highlighting how the connected component representation varies based on the visual structure of different interfaces.

read the caption

Figure 5: Illustration of our method constructs the UI-connected graph based on the informativeness of screenshots. (a–d) Mobile; (e–f) PC; (g–h) Web.

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed Interleaved Vision-Language-Action (VLA) Streaming method. It highlights the significant length disparity between visual tokens from screenshots (around 1300) and textual tokens from queries or actions (less than 10). To address this imbalance and improve training efficiency, the method introduces two modes: Action-Visual Streaming, which handles the sequential nature of UI navigation tasks by incorporating visual history, and Action-Query Streaming, which is designed for UI grounding tasks and efficiently utilizes data through multi-turn interactions, similar to multi-turn dialogues.

read the caption

Figure 6: Illustration of Interleaved Vision-Text-Action Streaming. The visual tokens in screenshots are significantly longer (e.g., 1.3K) compared to queries or actions (e.g., fewer than 10). Thus, we introduce two modes: (a) Action-Visual Streaming for UI navigation and (b) Action-Query Streaming for UI grounding. These modes extend the concept of multi-turn dialogue and enable more efficient utilization of training data.

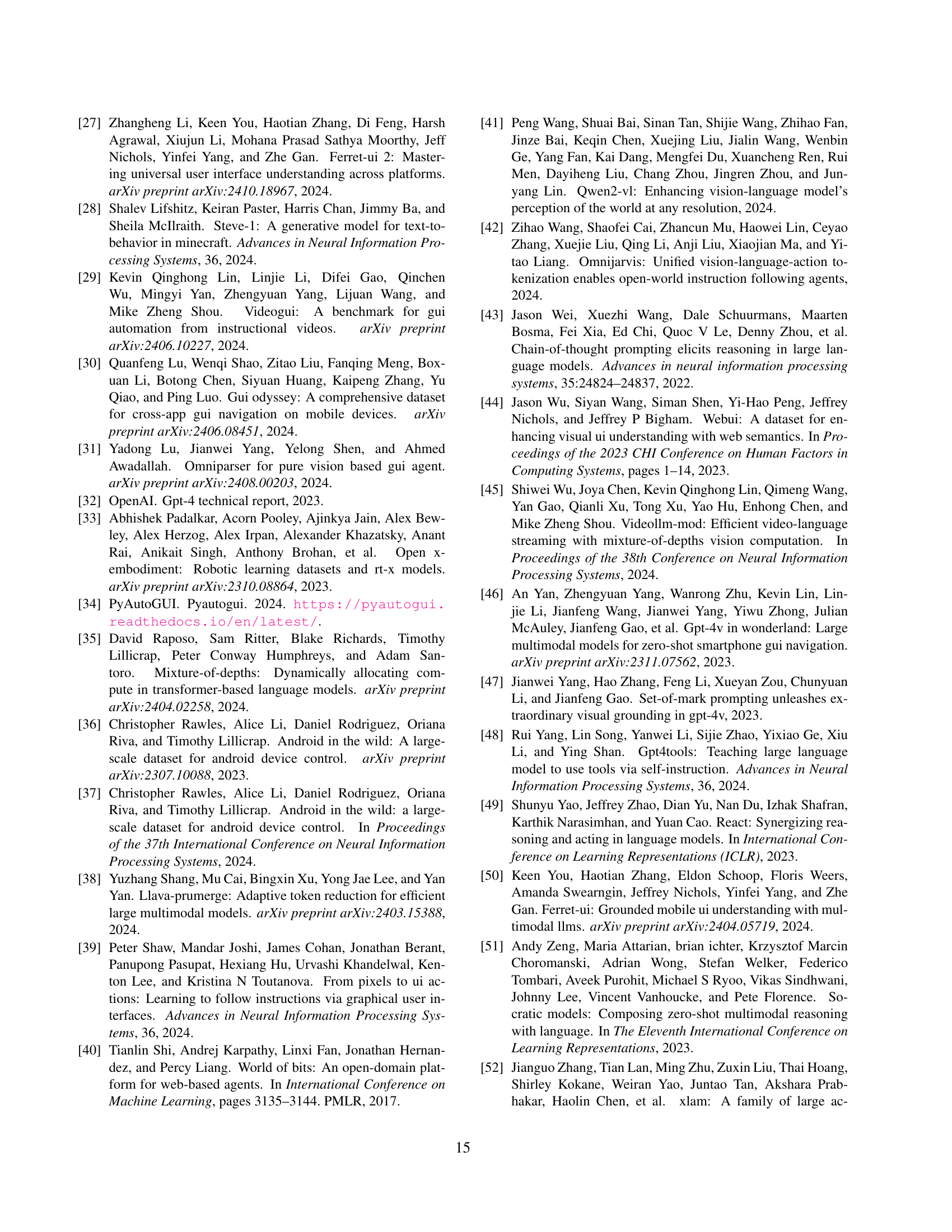

🔼 Figure 7 shows how the authors utilize GPT-4 to generate diverse queries for UI elements. Starting with the original, often simplistic, annotation (e.g., ‘message_ash’), GPT-4 is prompted with the visual context (screenshot and highlighted element) to produce three richer query types: Appearance (describing visual features), Spatial Relationship (locating the element relative to other UI elements), and Intention (describing the user’s likely goal for interacting with the element). This process significantly enriches the training data by adding more nuanced and descriptive labels beyond basic element names.

read the caption

Figure 7: We derive three types of query (appearance, spatial relationship, and intention) from raw annotation, assisted by GPT-4o.

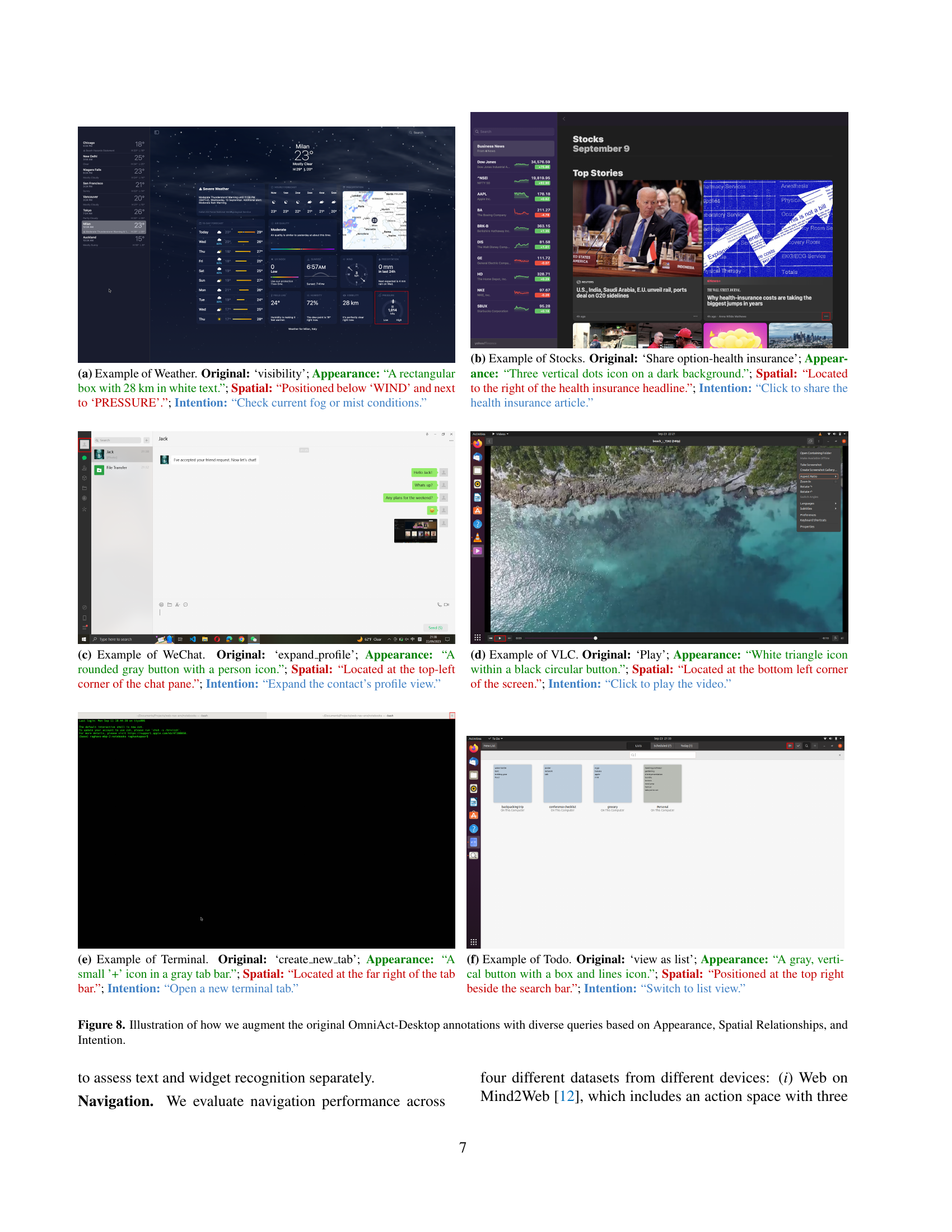

🔼 This figure shows an example of how the UI-Guided Visual Token Selection method is applied to a weather application screenshot. The original annotation for this element is ‘visibility’. The caption breaks down the element’s visual characteristics (appearance: a rectangular box with 28 km in white text), its location within the UI (spatial: positioned below ‘WIND’ and next to ‘PRESSURE’), and the user’s likely intent when interacting with it (intention: check current fog or mist conditions). This detailed caption highlights the different ways the model can perceive and understand UI elements.

read the caption

(a) Example of Weather. Original: ‘visibility’; Appearance: “A rectangular box with 28 km in white text.”; Spatial: “Positioned below ‘WIND’ and next to ‘PRESSURE’.”; Intention: “Check current fog or mist conditions.”

🔼 This figure shows an example from the Stocks dataset used in the paper. The original annotation describes the UI element as ‘Share option-health insurance.’ The image itself shows three vertical dots in a dark background. Spatially, this icon is located to the right of the health insurance headline. The intended user action for this element is to click it to share the health insurance article. This example highlights the dataset’s focus on detailed visual, spatial, and functional descriptions of UI elements.

read the caption

(b) Example of Stocks. Original: ‘Share option-health insurance’; Appearance: “Three vertical dots icon on a dark background.”; Spatial: “Located to the right of the health insurance headline.”; Intention: “Click to share the health insurance article.”

🔼 This figure shows an example from the WeChat app. The original annotation for this UI element is ’expand_profile’. A more detailed description of the element’s visual appearance is provided: it’s a rounded gray button with a person icon. The spatial location is described as being in the top-left corner of the chat pane. Finally, the intended action or purpose of this button is to expand the contact’s profile view. This detailed caption highlights how visual and contextual information is annotated in the dataset used for training.

read the caption

(c) Example of WeChat. Original: ‘expand_profile’; Appearance: “A rounded gray button with a person icon.”; Spatial: “Located at the top-left corner of the chat pane.”; Intention: “Expand the contact’s profile view.”

🔼 This figure shows an example from the OmniAct dataset illustrating how diverse queries can be generated for a single UI element using GPT-4. The original annotation only states the UI element is a ‘Play’ button. Using GPT-4, the researchers extracted several types of descriptions that go beyond a simple name: (1) Appearance: describing the visual properties of the button such as color and shape (a white triangle within a black circle). (2) Spatial: explaining where the button is located on the screen (bottom left corner). (3) Intention: stating the purpose of the button (to play the video). These three descriptions offer different ways to interact with and understand the UI element, which are helpful for training a robust visual agent.

read the caption

(d) Example of VLC. Original: ‘Play’; Appearance: “White triangle icon within a black circular button.”; Spatial: “Located at the bottom left corner of the screen.”; Intention: “Click to play the video.”

🔼 This figure shows an example of how the UI-connected graph is constructed for a terminal screenshot. The image is broken down into patches, and patches with similar RGB values are grouped into connected components. The original annotation is ‘create_new_tab’, but the model also considers appearance (‘A small ‘+’ icon in a gray tab bar’), spatial location (‘Located at the far right of the tab bar’), and intended function (‘Open a new terminal tab’) to better understand the screenshot.

read the caption

(e) Example of Terminal. Original: ‘create_new_tab’; Appearance: “A small ’+’ icon in a gray tab bar.”; Spatial: “Located at the far right of the tab bar.”; Intention: “Open a new terminal tab.”

🔼 This figure shows an example from the OmniAct dataset, specifically a screenshot from a ‘Todo’ application. The caption details four aspects of the image to help illustrate how the model is trained to understand visual elements within GUI interfaces. The ‘Original’ label refers to the original annotation of this specific item, ‘view as list.’ The ‘Appearance’ description is a summary of the visual properties: a gray, vertical button with a box and lines icon. ‘Spatial’ gives the location relative to the rest of the UI, positioned at the top right beside the search bar. Finally, ‘Intention’ describes what action the button is associated with: switching to a list view of the task items.

read the caption

(f) Example of Todo. Original: ‘view as list’; Appearance: “A gray, vertical button with a box and lines icon.”; Spatial: “Positioned at the top right beside the search bar.”; Intention: “Switch to list view.”

🔼 Figure 8 shows examples of how the authors enhanced the OmniAct-Desktop dataset. The original dataset only provided basic labels for UI elements. To enrich this, the authors used GPT-4 to generate more descriptive queries for each UI element. These queries are categorized into three types: Appearance (describing visual characteristics), Spatial Relationships (describing the element’s location relative to other elements), and Intention (describing the user’s likely goal when interacting with the element). This augmentation resulted in a more comprehensive and diverse dataset for training their GUI visual agent.

read the caption

Figure 8: Illustration of how we augment the original OmniAct-Desktop annotations with diverse queries based on Appearance, Spatial Relationships, and Intention.

🔼 Table 4 presents a comparison of different models’ performance on the Mind2Web web navigation benchmark. The table shows the performance in terms of Element Accuracy (Ele.Acc), Operation F1-score (Op.F1), and Average Steps to Success (Step.SR). Models marked in gray require either HTML text inputs or access to the closed-source GPT-4V language model. ShowUI† denotes a variant of the ShowUI model that uses only action history, not visual history. Importantly, the table highlights that ShowUI achieves zero-shot performance comparable to SeeClick, which is a model that uses both pre-training and fine-tuning. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the ShowUI model.

read the caption

Table 4: Web Navigation on Mind2Web. The gray correspond to methods that required HTML text inputsor rely on close-source GPT-4V (marked with *). ShowUI ††\dagger† denotes our variant utilizing only action history. ShowUI’s zero-shot performance yield comparable score with SeeClick with pretrained and fine-tuning.

🔼 This table presents the results of online navigation experiments conducted using the MiniWob benchmark. Specifically, it shows the performance of the ShowUI model and its variant (ShowUI†), which uses only action history, on 35 tasks. The results are compared against the SeeClick model [11], a relevant benchmark for this task, showcasing the effectiveness of ShowUI in a dynamic online environment. The table likely includes metrics such as accuracy, success rate, or other relevant performance indicators.

read the caption

Table 5: Results on online navigation MiniWob on 35-tasks split following SeeClick [11]. ShowUI ††\dagger† denotes our variant utilizing only action history.

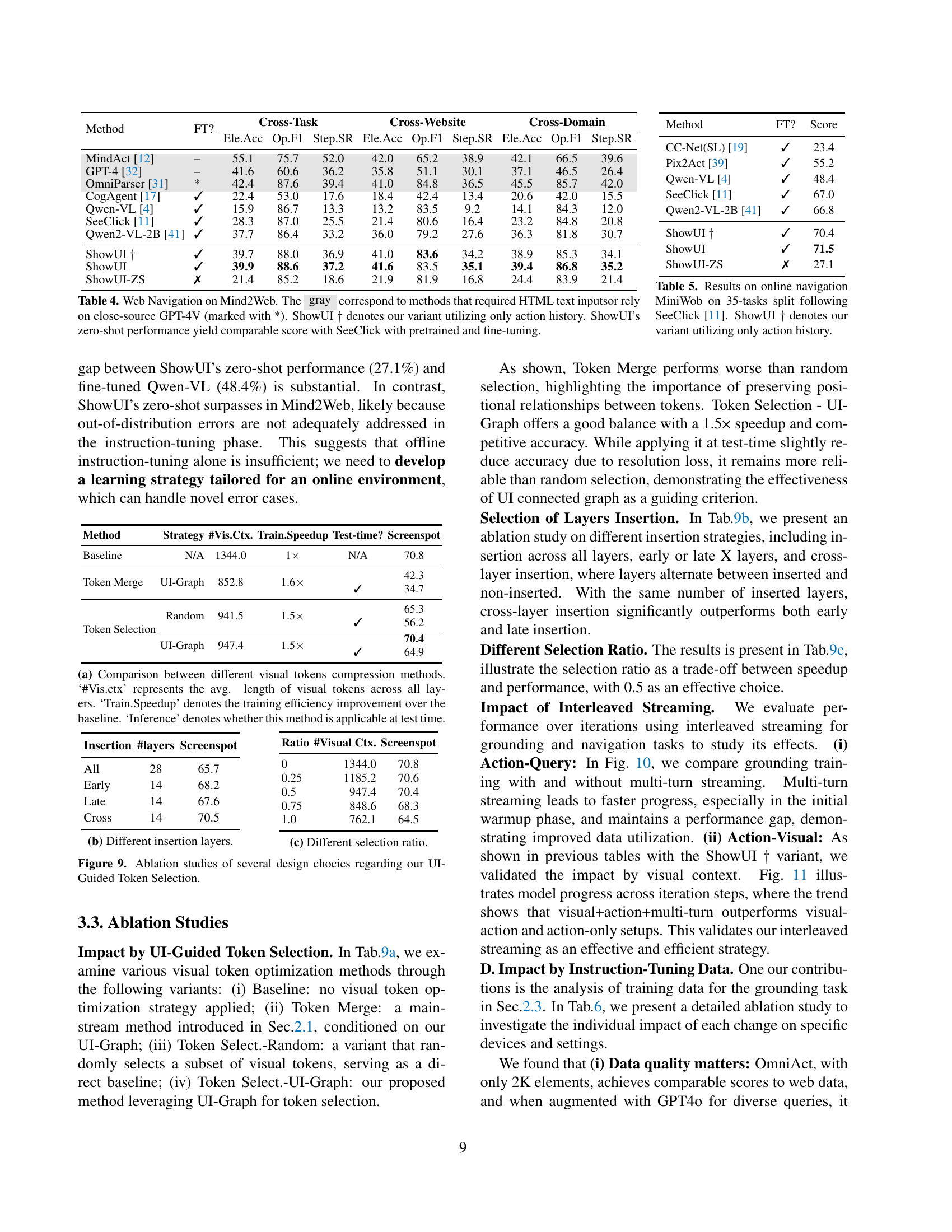

🔼 This figure compares three different methods for compressing visual tokens in a vision-language model: a baseline method with no compression, a token merging approach, and a token selection approach guided by a UI-connected graph. The comparison is based on three key metrics: the average length of visual tokens across all layers (#Vis.ctx), the training speedup achieved compared to the baseline method (Train.Speedup), and whether each method can be used during inference (Inference). The UI-connected graph method is shown to be superior, providing a substantial reduction in token length and training time without sacrificing inference capability.

read the caption

(g) Comparison between different visual tokens compression methods. ‘#Vis.ctx’ represents the avg. length of visual tokens across all layers. ‘Train.Speedup’ denotes the training efficiency improvement over the baseline. ‘Inference’ denotes whether this method is applicable at test time.

🔼 This ablation study explores the impact of inserting UI-guided token selection at different layers of the model. It compares the performance of inserting the method across all layers, early layers, late layers, and cross layers (alternating between inserted and non-inserted layers). The goal is to determine the optimal layer(s) for incorporating this technique to maximize performance.

read the caption

(h) Different insertion layers.

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of different token selection ratios on the model’s performance. The token selection ratio controls how many tokens are randomly selected within each UI-connected component during training. The figure likely shows the trade-off between reducing computational cost (by selecting fewer tokens) and maintaining sufficient model accuracy (by retaining enough tokens for the self-attention mechanism). Different ratios are tested, and their resulting accuracy on the Screenspot benchmark are compared.

read the caption

(i) Different selection ratio.

🔼 This figure presents ablation studies that analyze the impact of different design choices related to the UI-Guided Token Selection method. It explores the effects of various token compression methods (Token Merge, Random Token Selection, and UI-Graph guided Token Selection), the optimal layer for inserting the selection mechanism (early, late, cross-layer, or all layers), and the impact of different selection ratios on model performance and training speed. The results show the effectiveness of the proposed UI-guided token selection method compared to alternative techniques.

read the caption

Figure 9: Ablation studies of several design chocies regarding our UI-Guided Token Selection.

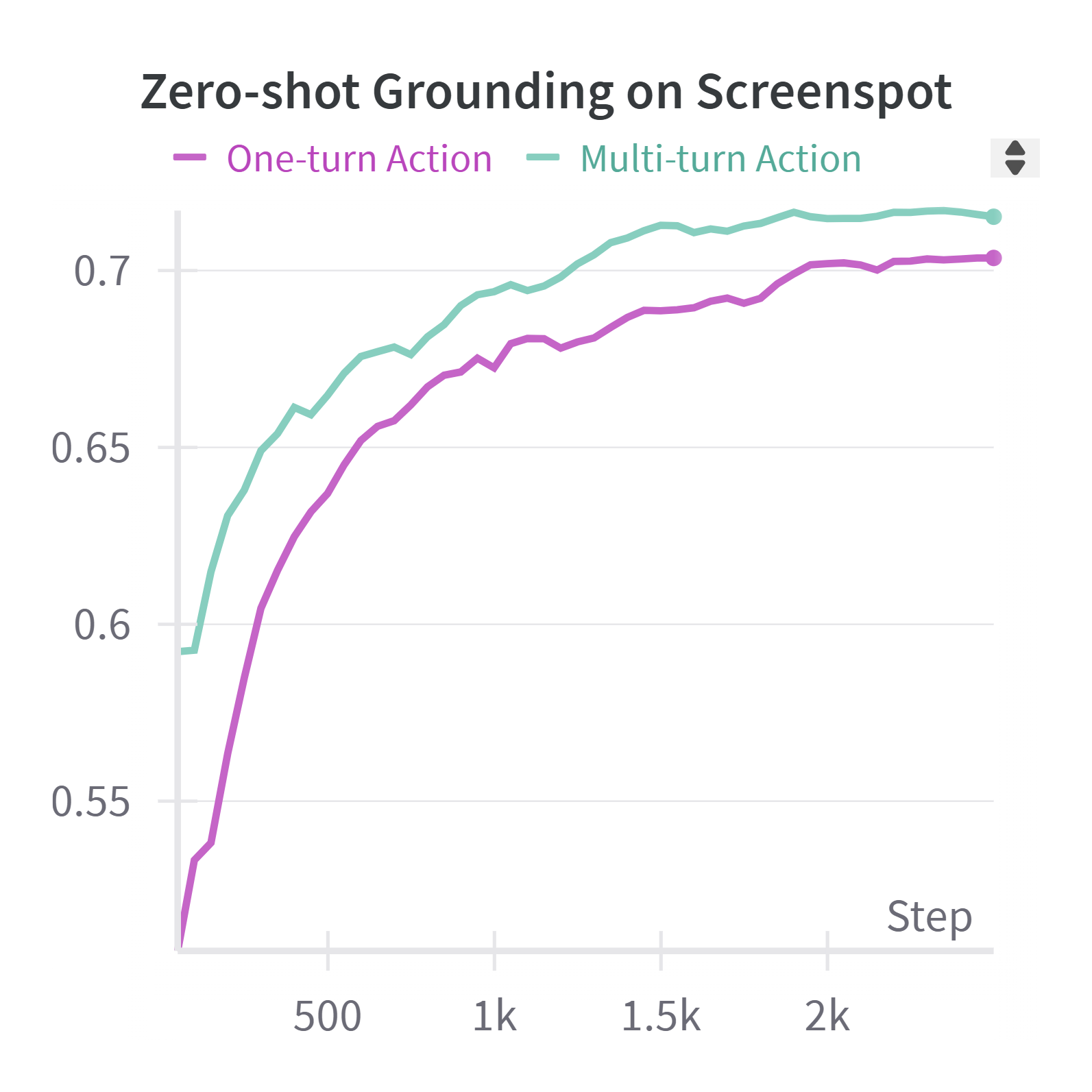

🔼 This figure displays the impact of using interleaved action-query streaming on the performance of a grounding task. The model was trained using 119,000 data points focused on grounding, and then evaluated on the Screenspot benchmark. The graph shows how the model’s performance changes over the course of training, comparing a one-turn action approach to a multi-turn approach. The multi-turn approach allows the model to process multiple queries and actions within a single training step, potentially improving efficiency and accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 10: Impact by Interleaved action-query streaming on Grounding task: trained with 119K grounding data, Eval with Screenspot.

More on tables

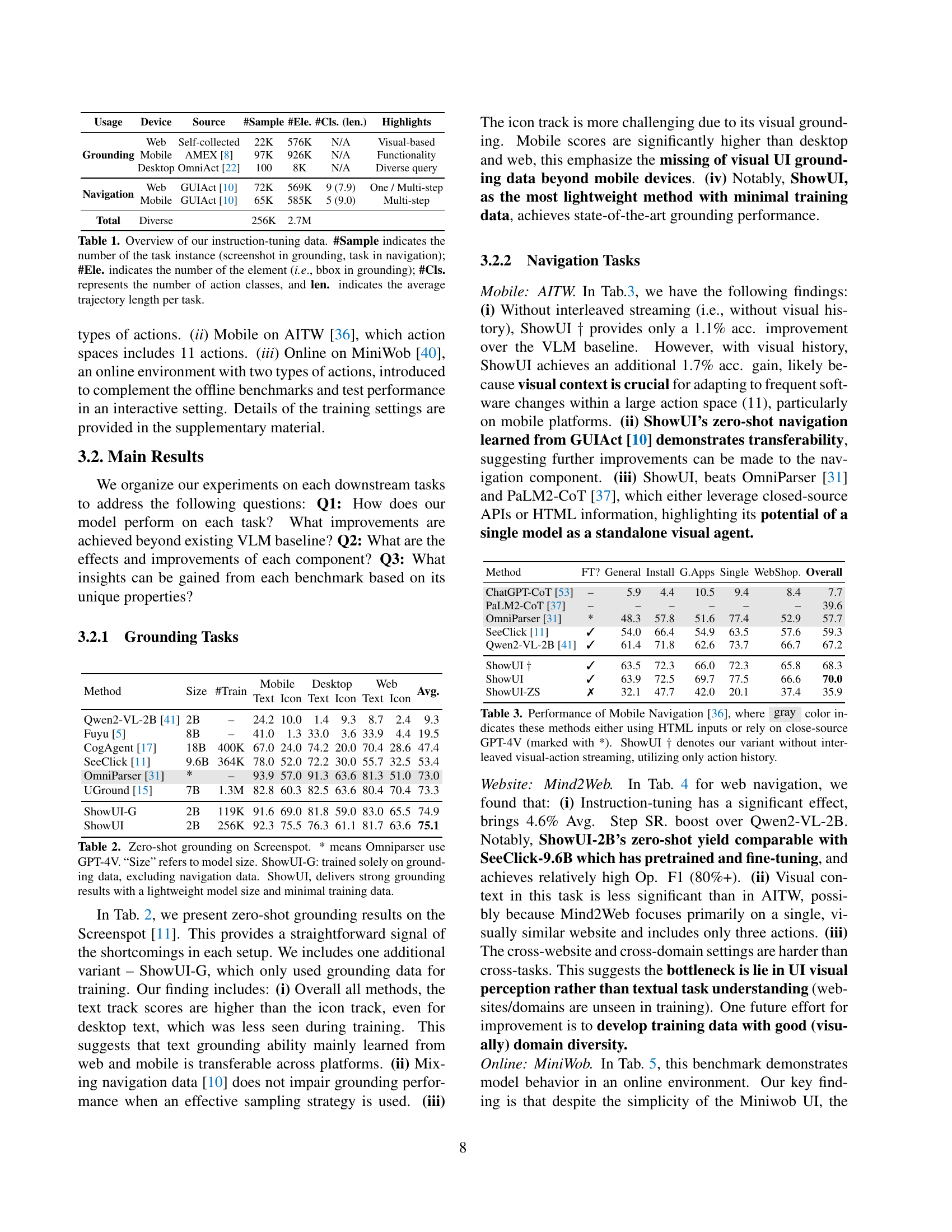

| Method | Size | #Train | Mobile Text | Mobile Icon | Desktop Text | Desktop Icon | Web Text | Web Icon | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen2-VL-2B [41] | 2B | – | 24.2 | 10.0 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 2.4 | 9.3 |

| Fuyu [5] | 8B | – | 41.0 | 1.3 | 33.0 | 3.6 | 33.9 | 4.4 | 19.5 |

| CogAgent [17] | 18B | 400K | 67.0 | 24.0 | 74.2 | 20.0 | 70.4 | 28.6 | 47.4 |

| SeeClick [11] | 9.6B | 364K | 78.0 | 52.0 | 72.2 | 30.0 | 55.7 | 32.5 | 53.4 |

| OmniParser [31] | * | – | 93.9 | 57.0 | 91.3 | 63.6 | 81.3 | 51.0 | 73.0 |

| UGround [15] | 7B | 1.3M | 82.8 | 60.3 | 82.5 | 63.6 | 80.4 | 70.4 | 73.3 |

| ShowUI-G | 2B | 119K | 91.6 | 69.0 | 81.8 | 59.0 | 83.0 | 65.5 | 74.9 |

| ShowUI | 2B | 256K | 92.3 | 75.5 | 76.3 | 61.1 | 81.7 | 63.6 | 75.1 |

🔼 This table presents the results of a zero-shot grounding experiment using the Screenspot benchmark dataset. It compares the performance of ShowUI, a lightweight vision-language-action model, against other state-of-the-art models. The comparison considers model size, training data size, and grounding accuracy across different device types (Web, Mobile, Desktop). The asterisk (*) indicates that the Omniparser model utilized GPT-4V. ShowUI-G represents a variant of ShowUI trained exclusively on grounding data, without using navigation data. The results show that ShowUI achieves strong performance with a small model size and relatively little training data.

read the caption

Table 2: Zero-shot grounding on Screenspot. * means Omniparser use GPT-4V. “Size” refers to model size. ShowUI-G: trained solely on grounding data, excluding navigation data. ShowUI, delivers strong grounding results with a lightweight model size and minimal training data.

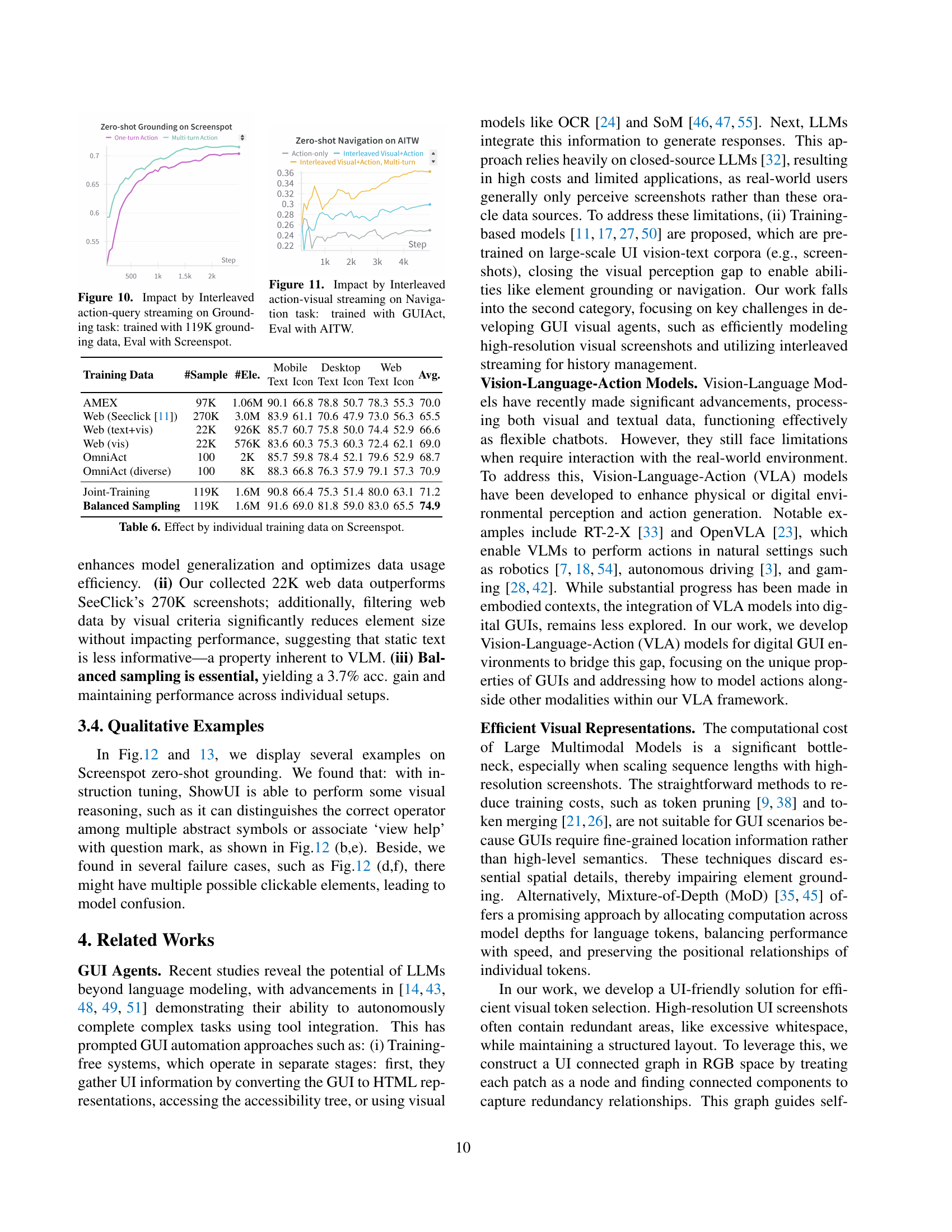

| Method | FT? | General | Install | G.Apps | Single | WebShop. | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT-CoT [53] | – | 5.9 | 4.4 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 8.4 | 7.7 |

| PaLM2-CoT [37] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 39.6 |

| OmniParser [31] | * | 48.3 | 57.8 | 51.6 | 77.4 | 52.9 | 57.7 |

| SeeClick [11] | ✓ | 54.0 | 66.4 | 54.9 | 63.5 | 57.6 | 59.3 |

| Qwen2-VL-2B [41] | ✓ | 61.4 | 71.8 | 62.6 | 73.7 | 66.7 | 67.2 |

| ShowUI † | ✓ | 63.5 | 72.3 | 66.0 | 72.3 | 65.8 | 68.3 |

| ShowUI | ✓ | 63.9 | 72.5 | 69.7 | 77.5 | 66.6 | 70.0 |

| ShowUI-ZS | ✗ | 32.1 | 47.7 | 42.0 | 20.1 | 37.4 | 35.9 |

🔼 Table 3 presents a comparison of different models’ performance on mobile navigation tasks from the AITW benchmark [36]. The table shows the accuracy of each model in terms of element accuracy and operational F1-score, as well as average steps to reach the goal in navigation tasks. Models marked with an asterisk (*) use either HTML inputs or rely on the closed-source GPT-4V language model. The entry for ShowUI† indicates the performance of a variant of the ShowUI model that does not use interleaved vision-action streaming, relying solely on action history.

read the caption

Table 3: Performance of Mobile Navigation [36], where gray color indicates these methods either using HTML inputs or rely on close-source GPT-4V (marked with *). ShowUI ††\dagger† denotes our variant without interleaved visual-action streaming, utilizing only action history.

| Method | FT? | Cross-Task Ele.Acc | Cross-Task Op.F1 | Cross-Task Step.SR | Cross-Website Ele.Acc | Cross-Website Op.F1 | Cross-Website Step.SR | Cross-Domain Ele.Acc | Cross-Domain Op.F1 | Cross-Domain Step.SR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MindAct [12] | – | 55.1 | 75.7 | 52.0 | 42.0 | 65.2 | 38.9 | 42.1 | 66.5 | 39.6 |

| GPT-4 [32] | – | 41.6 | 60.6 | 36.2 | 35.8 | 51.1 | 30.1 | 37.1 | 46.5 | 26.4 |

| OmniParser [31] | * | 42.4 | 87.6 | 39.4 | 41.0 | 84.8 | 36.5 | 45.5 | 85.7 | 42.0 |

| CogAgent [17] | ✓ | 22.4 | 53.0 | 17.6 | 18.4 | 42.4 | 13.4 | 20.6 | 42.0 | 15.5 |

| Qwen-VL [4] | ✓ | 15.9 | 86.7 | 13.3 | 13.2 | 83.5 | 9.2 | 14.1 | 84.3 | 12.0 |

| SeeClick [11] | ✓ | 28.3 | 87.0 | 25.5 | 21.4 | 80.6 | 16.4 | 23.2 | 84.8 | 20.8 |

| Qwen2-VL-2B [41] | ✓ | 37.7 | 86.4 | 33.2 | 36.0 | 79.2 | 27.6 | 36.3 | 81.8 | 30.7 |

| ShowUI † | ✓ | 39.7 | 88.0 | 36.9 | 41.0 | 83.6 | 34.2 | 38.9 | 85.3 | 34.1 |

| ShowUI | ✓ | 39.9 | 88.6 | 37.2 | 41.6 | 83.5 | 35.1 | 39.4 | 86.8 | 35.2 |

| ShowUI-ZS | ✗ | 21.4 | 85.2 | 18.6 | 21.9 | 81.9 | 16.8 | 24.4 | 83.9 | 21.4 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study, evaluating the impact of individual training datasets on the Screenspot benchmark’s zero-shot grounding performance. It shows the performance gains achieved by using different combinations of training datasets (AMEX, Web, OmniAct, and GUIAct) with various data augmentation methods. The data demonstrates the effects of each data source and the benefit of balanced data sampling strategies for improved model generalization.

read the caption

Table 6: Effect by individual training data on Screenspot.

Full paper#