↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current AI sketch generation methods struggle to capture the dynamic and abstract nature of human sketching, often producing artificial-looking results. They typically optimize all strokes at once, ignoring the sequential process inherent in human drawing. This limits their ability to generate truly natural-looking sketches and hampers collaborative sketching experiences.

SketchAgent overcomes these issues by utilizing a multimodal large language model (LLM). It introduces an intuitive sketching language that allows the LLM to “draw” stroke by stroke, making the process more natural and dynamic. This approach enables interactive human-agent collaboration and allows users to refine sketches through chat-based editing. The results demonstrate SketchAgent’s ability to generate diverse and meaningful sketches that closely resemble human drawings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI, computer graphics, and HCI because it presents a novel approach to sketch generation that leverages the power of large language models. It opens new avenues for research into human-computer interaction, collaborative creativity, and the development of more intuitive and natural interfaces for creative tasks.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates SketchAgent’s capabilities. It shows how the system uses a pre-trained multimodal large language model (LLM) and a custom sketching language to generate sketches sequentially based on textual descriptions. The top row demonstrates the text-conditioned sequential generation, depicting how the system generates a sketch based on various textual prompts (such as ‘butterfly’, ‘Taj Mahal’). The middle section highlights the human-agent collaborative sketching aspect, where the user and agent take turns sketching on a canvas, creating a sketch together. Finally, the rightmost section shows the system’s chat-based sketch editing functionality, where the user can provide instructions for editing the sketch via natural language interactions.

read the caption

Figure 1: SketchAgent leverages an off-the-shelf multimodal LLM to facilitate language-driven, sequential sketch generation through an intuitive sketching language. It can sketch diverse concepts, engage in interactive sketching with humans, and edit content via chat.

| Image | Description |

|---|---|

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/DALLE.png | (A) DALLE3 [5] |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/eye-illustration_claude_svg.png | (B) LLMs [3] (SVG) |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/eye_ours.png | (C) SketchAgent |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/eye_human.png | (D) Human [54] |

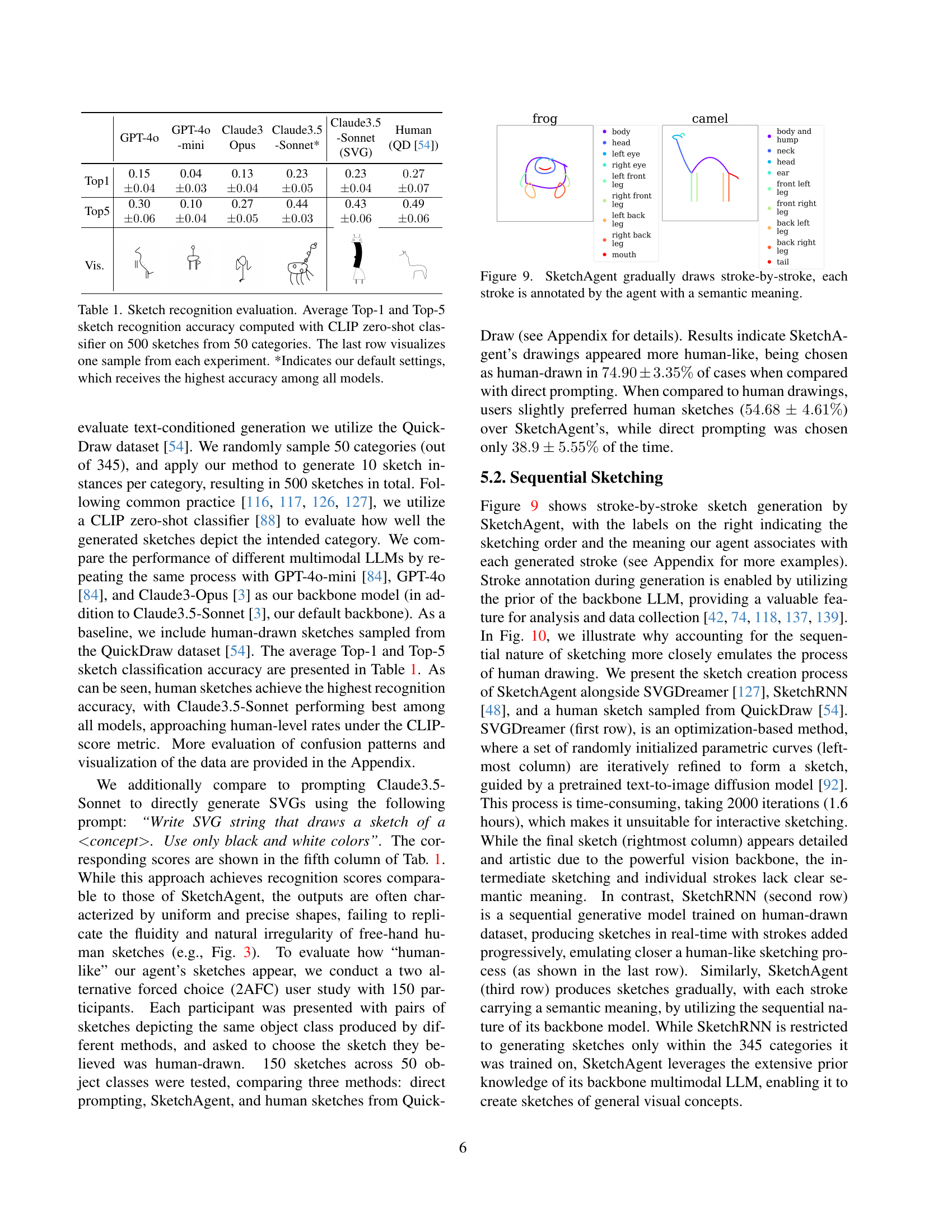

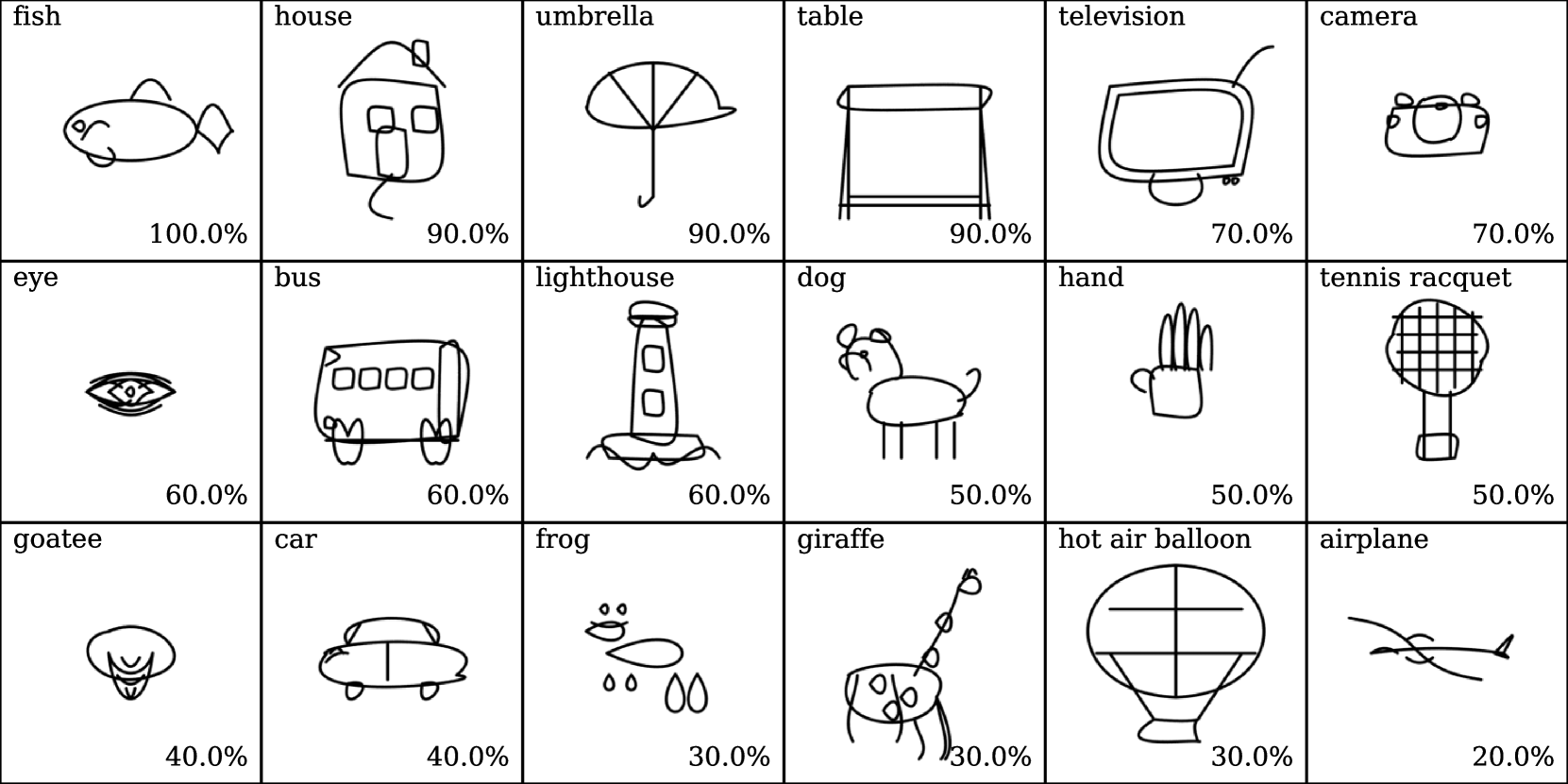

🔼 This table presents the results of a zero-shot sketch recognition evaluation using the CLIP model. 500 sketches were generated across 50 categories, with 10 sketches generated per category using different methods (human drawing and various LLMs). The table shows the average top-1 and top-5 accuracies of the recognition task. The ‘Top-1’ accuracy represents the percentage of sketches correctly classified as belonging to the intended category. ‘Top-5’ represents the percentage of sketches classified correctly among the top five most probable categories suggested by the model. The last row visually displays one example sketch generated by each method (human and LLMs). The asterisk (*) indicates the model and settings which provided the highest overall accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Sketch recognition evaluation. Average Top-1 and Top-5 sketch recognition accuracy computed with CLIP zero-shot classifier on 500 sketches from 50 categories. The last row visualizes one sample from each experiment. *Indicates our default settings, which receives the highest accuracy among all models.

In-depth insights#

Sketch Synthesis#

Sketch synthesis, at its core, seeks to bridge the gap between abstract ideas and their visual representation. This involves generating sketches from various inputs, such as text descriptions, image examples, or even user interactions. The challenges lie in replicating the fluidity, expressiveness, and nuanced details of human sketching. Successful sketch synthesis requires robust models capable of understanding semantic meaning, handling spatial relationships effectively, and generating aesthetically pleasing outputs. Sequential approaches are particularly promising, mirroring the iterative nature of human sketching where strokes are added progressively, allowing for dynamic feedback and refinement. These methods must address the issue of sparsity in training data and computational complexity which often hinder the creation of truly versatile and high-quality systems. Ultimately, the aim is to empower users by enabling fast, intuitive, and collaborative design and idea exploration through easily accessible digital sketching tools, whether for professionals or casual users.

LLM for Sketching#

Leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) for sketch generation presents a unique opportunity to bridge the gap between human creativity and artificial systems. The inherent sequential nature of LLMs, coupled with their capacity to understand and generate text, makes them suitable for modeling the dynamic and iterative process of sketching. However, directly applying LLMs to image generation often falls short due to the limitations of existing multimodal models that primarily output text, rather than directly producing visual outputs. Therefore, innovative approaches are required. One strategy is to design an intuitive sketching language, enabling the LLM to “draw” via string-based commands that are then translated into vector graphics. This approach bypasses the limitations of pixel-based methods and allows for more nuanced control over the sketching process. Another important aspect involves addressing the challenge of spatial reasoning, a skill LLMs currently struggle with. This could be mitigated through techniques like defining a numbered grid as a canvas, allowing the LLM to reference coordinates directly. The potential of human-agent collaboration is also significant, allowing real-time interactions where the LLM responds to the user’s input and edits, fostering a more dynamic and creative process.

Sequential Drawing#

Sequential drawing, as explored in the context of AI-driven sketch generation, presents a compelling approach to mimicking the human creative process. Unlike methods that optimize all strokes simultaneously, sequential drawing emphasizes the iterative nature of sketching. This iterative process allows for the incorporation of visual feedback and continuous adaptation, mirroring how humans build upon previous strokes to refine their creations. This iterative process, enabled by the inherent sequential nature of large language models (LLMs), is key to producing sketches with a more natural, dynamic appearance, rather than the rigid, mechanical results often generated by non-sequential techniques. The adoption of a sequential methodology necessitates a shift in representation from pixel-based to vector-based graphics. This transition facilitates a more intuitive sketching language that LLMs can process and interpret. The sequential approach also enables meaningful interactive and collaborative sketching between humans and AI agents, facilitating creative exploration and design processes. Overall, the advantages of this approach include increased realism in sketch generation, enhanced creativity, and more efficient and fluid human-computer interaction. However, challenges remain in successfully translating textual descriptions into precise spatial actions, and there’s still room for improvement in emulating the fine-grained control and subtle irregularities characteristic of human drawings.

Human-Agent Collab#

The concept of human-agent collaborative sketching, explored in the research paper, presents a fascinating avenue for advancing creativity and problem-solving. The core idea centers on the seamless integration of human intuition and artistic skill with the computational capabilities of AI agents. This collaboration moves beyond a simple division of labor, where each entity performs a distinct task; rather, it emphasizes a dynamic interplay, where human actions inform and refine the AI’s output, leading to a synergistic outcome superior to either’s individual effort. The success of this approach relies heavily on the design of an intuitive sketching language, enabling clear communication between human and machine. The use of a shared canvas, where both entities can directly interact with and modify the evolving sketch, further fosters this collaboration. This study highlights the iterative nature of the process, mimicking human sketching where refinements are made incrementally. The analysis of the results showcases that the human-AI sketches achieve a level of recognizability comparable to human-only sketches. However, challenges remain in ensuring effective real-time communication and understanding between the human and the AI, especially when complex concepts and fine-grained spatial reasoning are involved. Future work can focus on improving this communication and developing more robust error correction techniques to allow for a truly seamless and productive human-AI design process.

Future of Sketching#

The future of sketching hinges on the seamless integration of AI and human creativity. AI-powered tools will likely move beyond simple sketch generation, enabling real-time collaborative sketching where AI acts as an intelligent partner, offering suggestions and refinements. This collaboration could transform design processes, allowing for rapid prototyping and exploration of ideas. Beyond the visual aspect, the integration of AI could facilitate enhanced semantic understanding of sketches, enabling better communication and bridging the gap between visual and textual representations. Intuitive interfaces and natural language processing will be essential for intuitive interactions with AI-powered sketching tools. However, it’s crucial to ensure that these advancements prioritize human agency, empowering users to maintain control and personal expression, thereby preventing AI from replacing human creativity, but instead augmenting and enhancing it. The ethical implications of AI in sketching, particularly regarding intellectual property and bias, also require careful consideration.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure showcases diverse examples of sketches across various disciplines and purposes, highlighting the versatility of sketching as a communication tool. Panel (A) illustrates architectural sketches by Frank Gehry, demonstrating the use of sketching in the ideation and design process. Panel (B) shows an engineering drawing by Alexander Graham Bell, highlighting sketching’s role in technical communication. Panel (C) presents children’s drawings, emphasizing the expressive and emotional nature of sketching. Finally, Panel (D) depicts a basketball game strategy sketch, illustrating the use of sketches for visual communication and planning.

read the caption

Figure 2: Examples of sketches used across disciplines and goals. (A) Ideation and design: Process Elevation Sketches by the architect Frank Gehry, Guggenheim Museum. (B) Engineering: Alexander Bell’s telephone drawing. (C) Expressing emotions: Children’s sketches. (D) Visual communication: Planning and communicating game strategy in basketball.

🔼 Figure 3 demonstrates the differences in sketch generation methods. (A) shows that text-to-image diffusion models generate images in pixel space, which is a single-step process unlike the sequential, iterative process of human sketching. (B) illustrates that while LLMs can generate vector graphics (SVG) from text prompts, the results often appear uniform and machine-like. (C) shows the output of SketchAgent, our proposed method which, while using an LLM, generates sketches that are more natural and less mechanical. Finally, (D) displays examples of human sketches for comparison, highlighting the spontaneous and irregular nature of human-generated artwork.

read the caption

Figure 3: Sketch appearance. (A) Text-to-image diffusion models operate in pixel space, lacking thesequential nature of sketches. (B) Prompting LLMs to produce visuals with SVG results in a uniform, mechanical appearance. (C) Sketches produced by our agent appear less mechanical, more closely resembling the nature of (D) Human sketches, which are often spontaneous and irregular.

🔼 A cubic Bézier curve is a parametric curve defined by four control points: a starting point (P0), an ending point (P3), and two control points (P1 and P2) that influence the curve’s shape. The curve is smooth and can be described mathematically using a polynomial equation, where a parameter ’t’ (ranging from 0 to 1) determines the position along the curve. When t=0, the point is at P0, and when t=1, the point is at P3. The image illustrates a cubic Bézier curve and its control points, showing how the control points affect the curve’s curvature.

read the caption

Figure 4: Cubic Bézier curve.

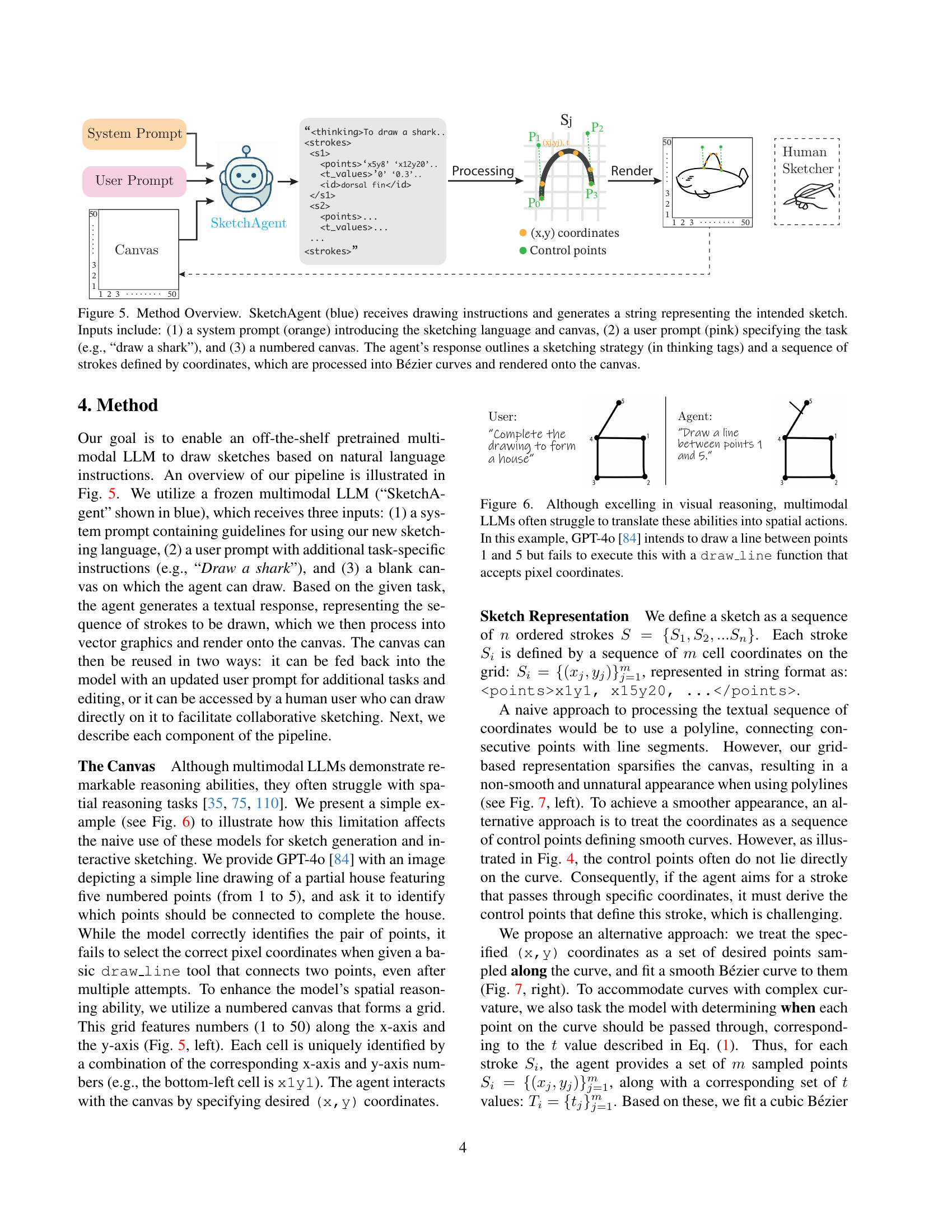

🔼 SketchAgent, the core component of the system, receives three inputs: (1) a system prompt defining the sketching language and canvas; (2) a user prompt specifying the drawing task (e.g., ‘draw a shark’); and (3) a numbered canvas. SketchAgent processes these inputs and outputs a textual representation of the intended sketch, including a ’thinking’ section outlining the drawing strategy and a sequence of strokes described by coordinates. These coordinates are then converted into Bézier curves and rendered on the canvas.

read the caption

Figure 5: Method Overview. SketchAgent (blue) receives drawing instructions and generates a string representing the intended sketch. Inputs include: (1) a system prompt (orange) introducing the sketching language and canvas, (2) a user prompt (pink) specifying the task (e.g., “draw a shark”), and (3) a numbered canvas. The agent’s response outlines a sketching strategy (in thinking tags) and a sequence of strokes defined by coordinates, which are processed into Bézier curves and rendered onto the canvas.

🔼 The figure demonstrates the limitations of multimodal LLMs in performing spatial reasoning tasks. Despite excelling at visual reasoning, the model struggles to translate this understanding into specific actions within a coordinate system. The example shows a simple drawing with numbered points. The model correctly identifies the points needing to be connected to complete the drawing. However, when instructed to draw a line using a

draw_linefunction that requires pixel coordinates, the model fails to execute the command correctly, illustrating the disconnect between high-level visual understanding and precise low-level spatial control.read the caption

Figure 6: Although excelling in visual reasoning, multimodal LLMs often struggle to translate these abilities into spatial actions. In this example, GPT-4o [84] intends to draw a line between points 1 and 5 but fails to execute this with a draw_line function that accepts pixel coordinates.

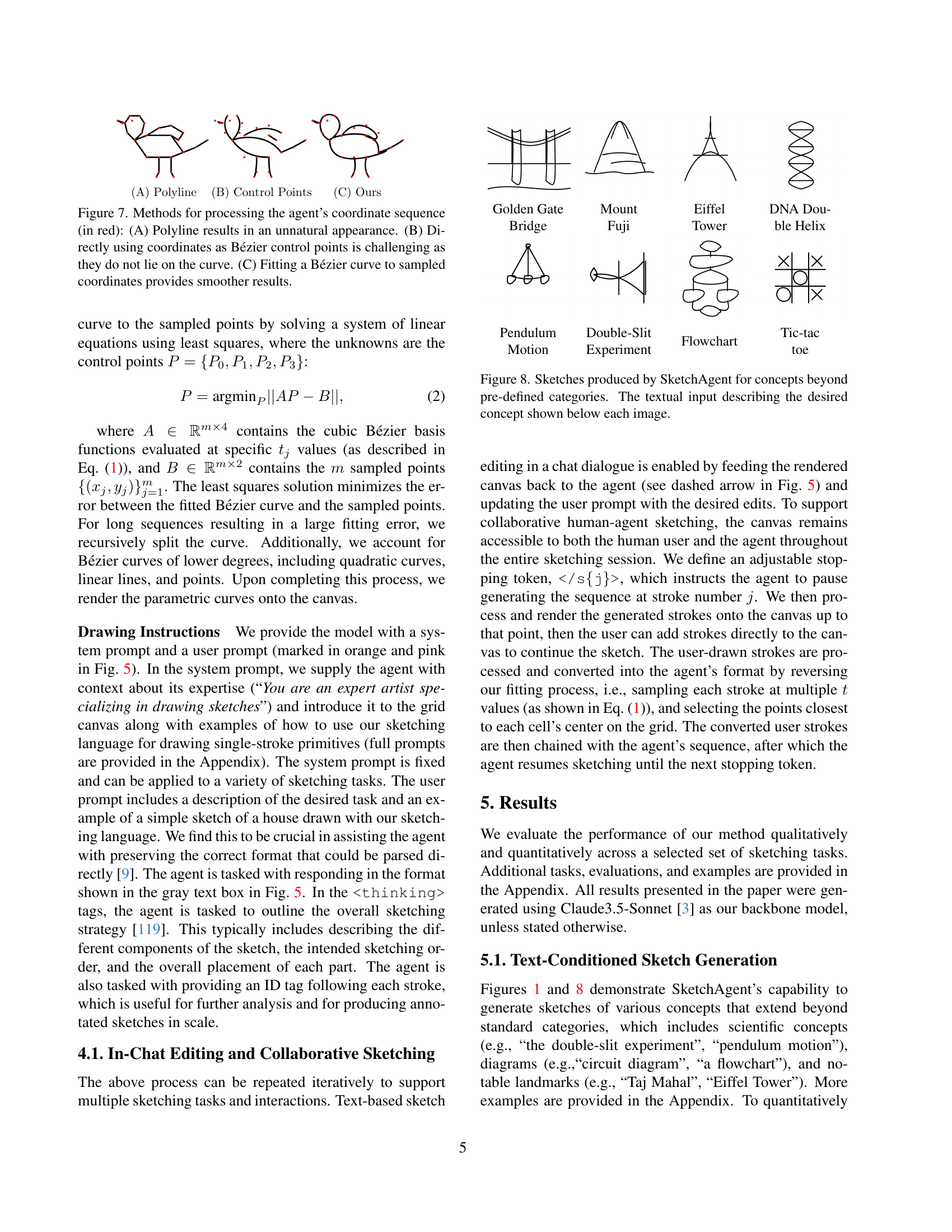

🔼 This figure compares three different approaches to rendering a sequence of coordinates generated by the SketchAgent model into a smooth curve. Method (A) uses polylines, resulting in a jagged, unnatural-looking sketch. Method (B) attempts to use the coordinates directly as control points for a Bézier curve; however, this approach is flawed as Bézier control points do not typically lie on the curve itself, leading to inaccurate rendering. Method (C), the preferred method, samples points along a curve and then fits a Bézier curve to these points, achieving a much smoother and more natural-looking result.

read the caption

Figure 7: Methods for processing the agent’s coordinate sequence (in red): (A) Polyline results in an unnatural appearance. (B) Directly using coordinates as Bézier control points is challenging as they do not lie on the curve. (C) Fitting a Bézier curve to sampled coordinates provides smoother results.

🔼 This figure showcases SketchAgent’s ability to generate sketches of various concepts that go beyond pre-defined categories. It displays examples of sketches generated for concepts such as landmarks (Golden Gate Bridge, Mount Fuji, Eiffel Tower), natural objects (DNA Double Helix), and physics concepts (Pendulum Motion, Double Slit Experiment), among others. Each sketch is accompanied by the text prompt used to generate it, highlighting the model’s capability to interpret and visually represent diverse and abstract ideas.

read the caption

Figure 8: Sketches produced by SketchAgent for concepts beyond pre-defined categories. The textual input describing the desired concept shown below each image.

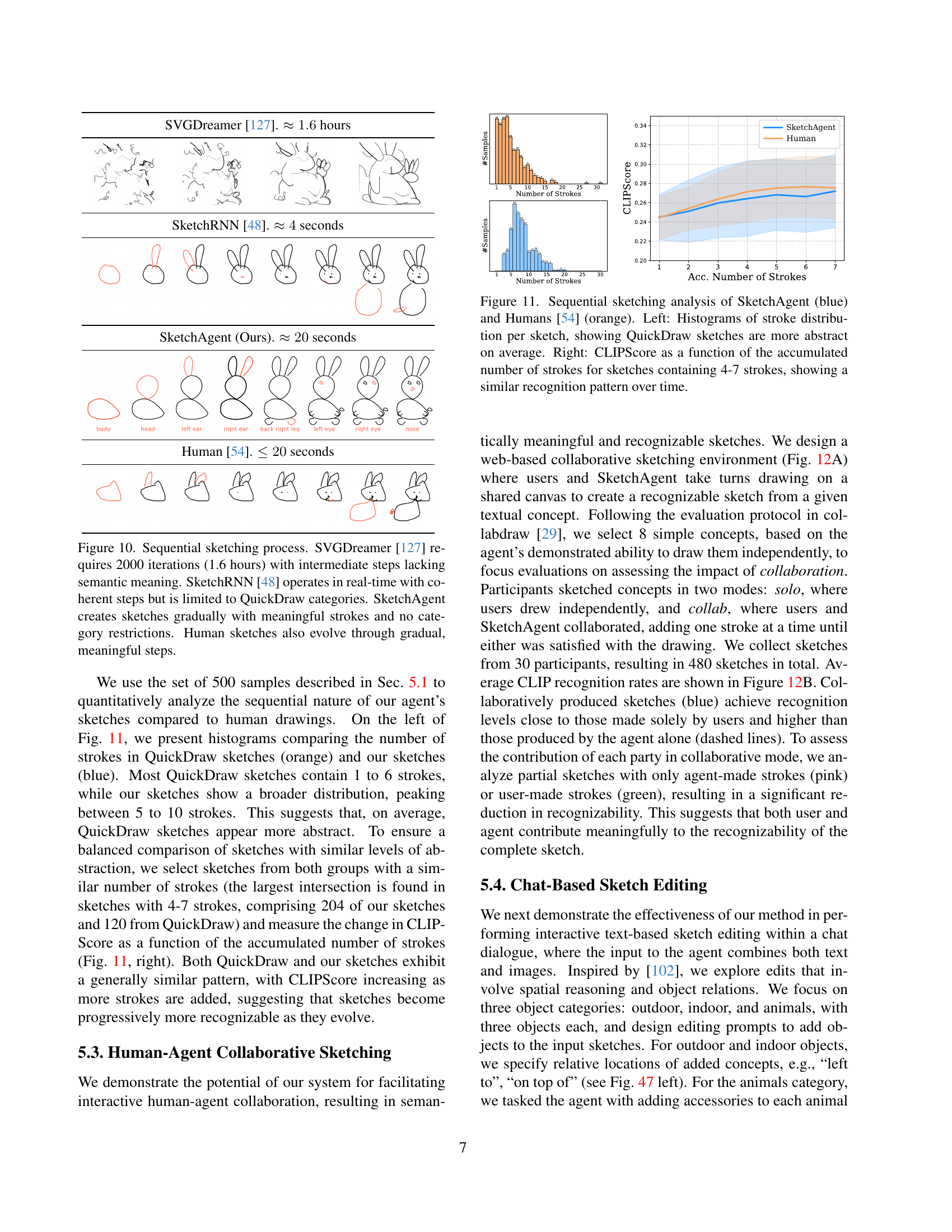

🔼 This figure showcases SketchAgent’s sequential sketching process. The image shows multiple stages of a camel being drawn, with each stroke labeled by SketchAgent to indicate the specific part of the camel (e.g., head, body, leg) that each stroke represents. This highlights the model’s ability to not only generate sketches stroke-by-stroke but also to provide meaningful semantic annotations for each stroke, demonstrating the model’s understanding of the drawing process and the object being drawn.

read the caption

Figure 9: SketchAgent gradually draws stroke-by-stroke, each stroke is annotated by the agent with a semantic meaning.

🔼 Figure 10 compares the sketching processes of four different methods: SVGDreamer, SketchRNN, SketchAgent, and human sketching. SVGDreamer, a purely optimization-based approach, is extremely slow (1.6 hours) and produces intermediate results that lack semantic meaning. SketchRNN, a recurrent neural network trained on the QuickDraw dataset, operates in real time, but is limited to the categories present in that dataset. SketchAgent, in contrast, generates sketches stroke by stroke in real time and demonstrates semantic meaning in each step, without being limited to predefined categories. Finally, human sketches are also shown as an example of gradual, meaningful stroke generation.

read the caption

Figure 10: Sequential sketching process. SVGDreamer [127] requires 2000 iterations (1.6 hours) with intermediate steps lacking semantic meaning. SketchRNN [48] operates in real-time with coherent steps but is limited to QuickDraw categories. SketchAgent creates sketches gradually with meaningful strokes and no category restrictions. Human sketches also evolve through gradual, meaningful steps.

🔼 This figure compares SketchAgent’s performance to human sketching in terms of sequential stroke generation. The left panel displays histograms showing the distribution of stroke counts in SketchAgent-generated sketches versus those from the QuickDraw dataset. The QuickDraw sketches tend to have fewer strokes, suggesting a more abstract style. The right panel shows how the CLIP image recognition score (a measure of how well the sketch represents its intended subject) changes as more strokes are added to sketches containing between 4 and 7 strokes. This analysis reveals that SketchAgent’s sketches show a similar increase in recognition score as more strokes are added, comparable to human drawings.

read the caption

Figure 11: Sequential sketching analysis of SketchAgent (blue) and Humans [54] (orange). Left: Histograms of stroke distribution per sketch, showing QuickDraw sketches are more abstract on average. Right: CLIPScore as a function of the accumulated number of strokes for sketches containing 4-7 strokes, showing a similar recognition pattern over time.

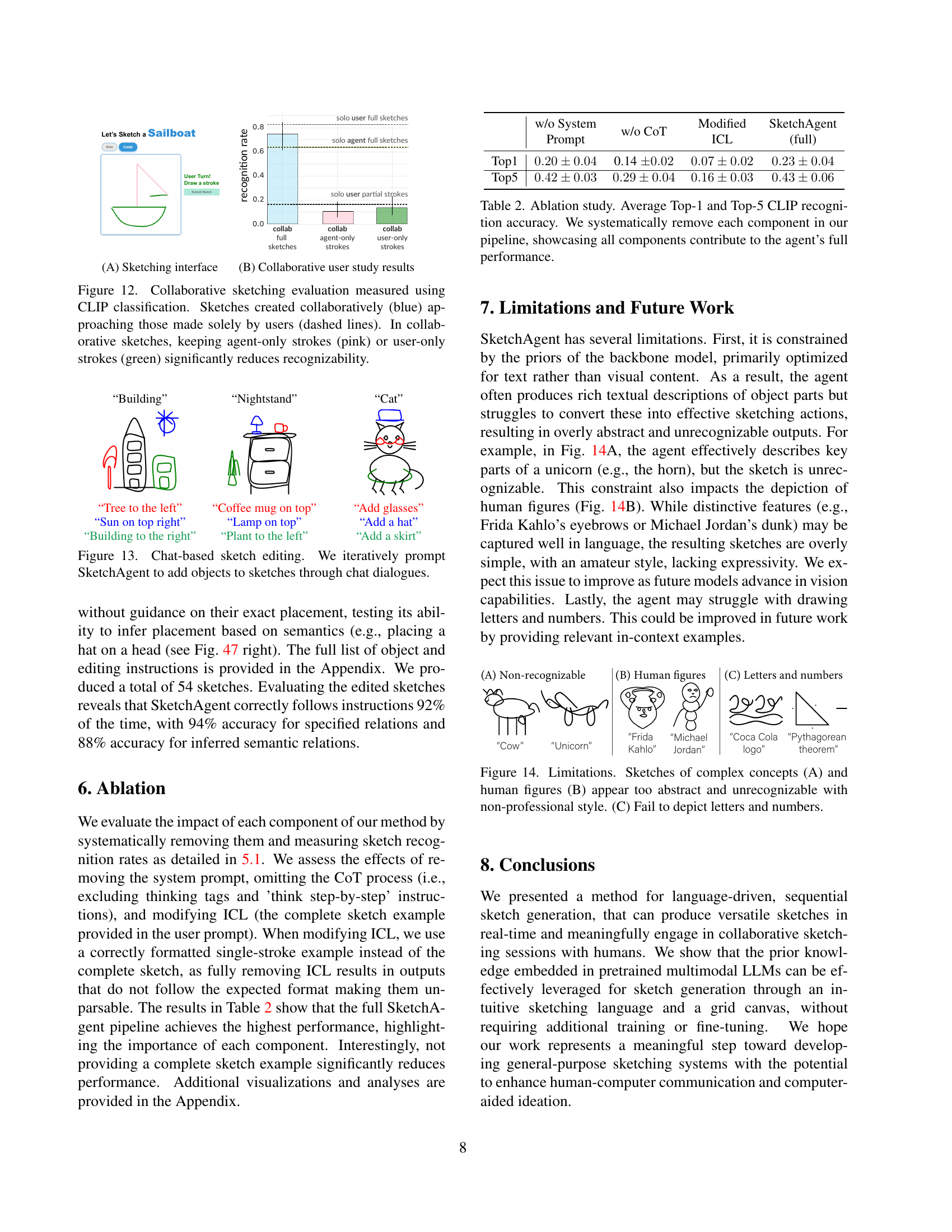

🔼 This figure displays the results of a collaborative sketching experiment comparing the performance of human-only sketching with human-agent collaborative sketching. The x-axis represents different categories of sketches, and the y-axis shows the CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) classification accuracy. The blue bars represent the accuracy of sketches produced collaboratively by humans and an AI agent. The dashed lines show the accuracy of sketches made solely by human participants. The pink and green bars highlight a key finding: when only the AI agent’s strokes (pink) or only the human’s strokes (green) are considered from the collaborative sketches, the overall accuracy drops significantly, indicating that the combined contributions of both human and AI are necessary for high recognition accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 12: Collaborative sketching evaluation measured using CLIP classification. Sketches created collaboratively (blue) approaching those made solely by users (dashed lines). In collaborative sketches, keeping agent-only strokes (pink) or user-only strokes (green) significantly reduces recognizability.

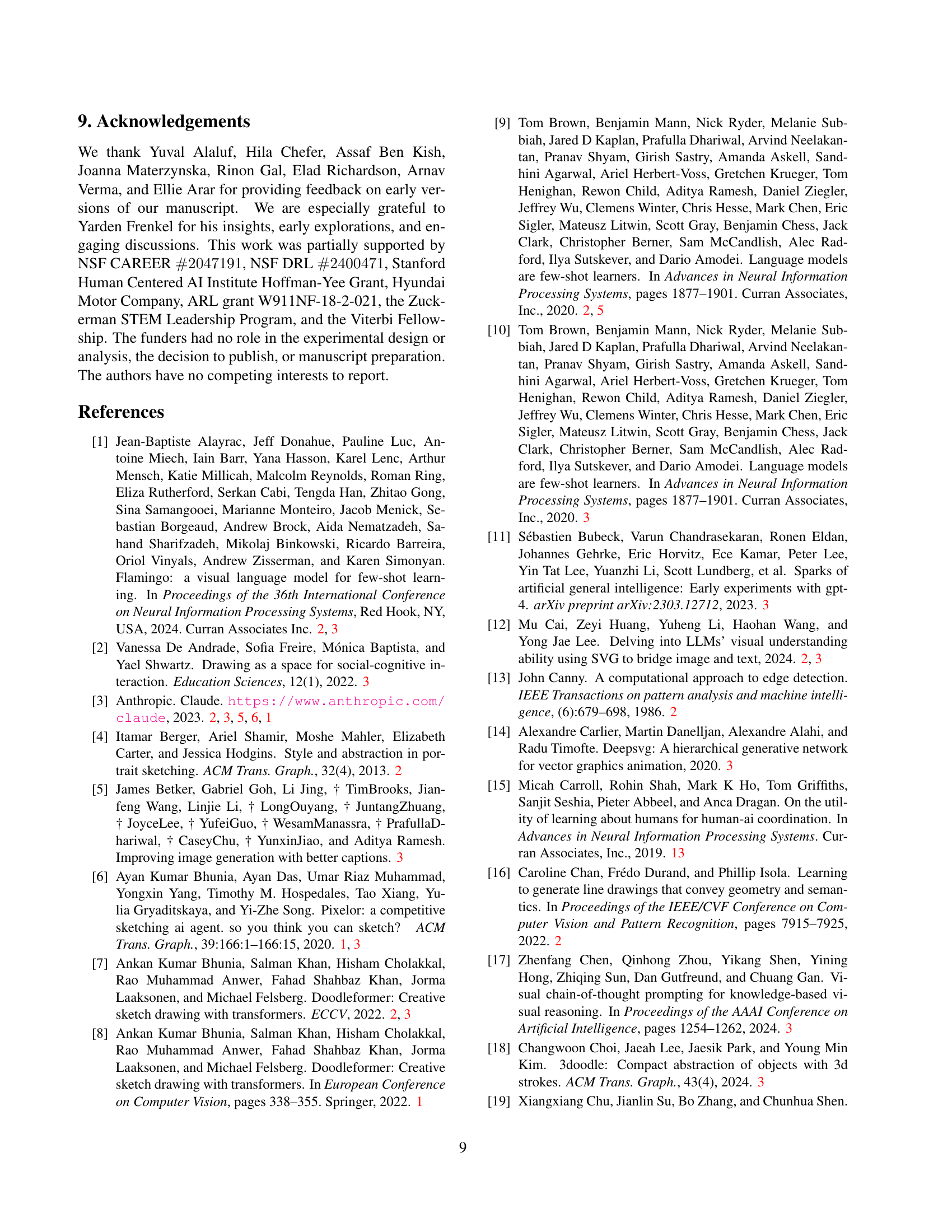

🔼 This figure demonstrates the iterative chat-based sketch editing capabilities of SketchAgent. The user starts with an initial sketch. Through a chat interface, the user provides textual instructions to the SketchAgent, such as adding specific objects (e.g., ‘Add glasses’, ‘Add a hat’) or specifying spatial relationships (‘Tree to the left’, ‘Sun on top right’). The agent then updates the sketch accordingly by adding the requested elements, resulting in a refined and progressively more complex drawing. This showcases the model’s ability to understand language-based instructions and use them to modify an existing drawing, adding another layer to the overall process of sketch creation.

read the caption

Figure 13: Chat-based sketch editing. We iteratively prompt SketchAgent to add objects to sketches through chat dialogues.

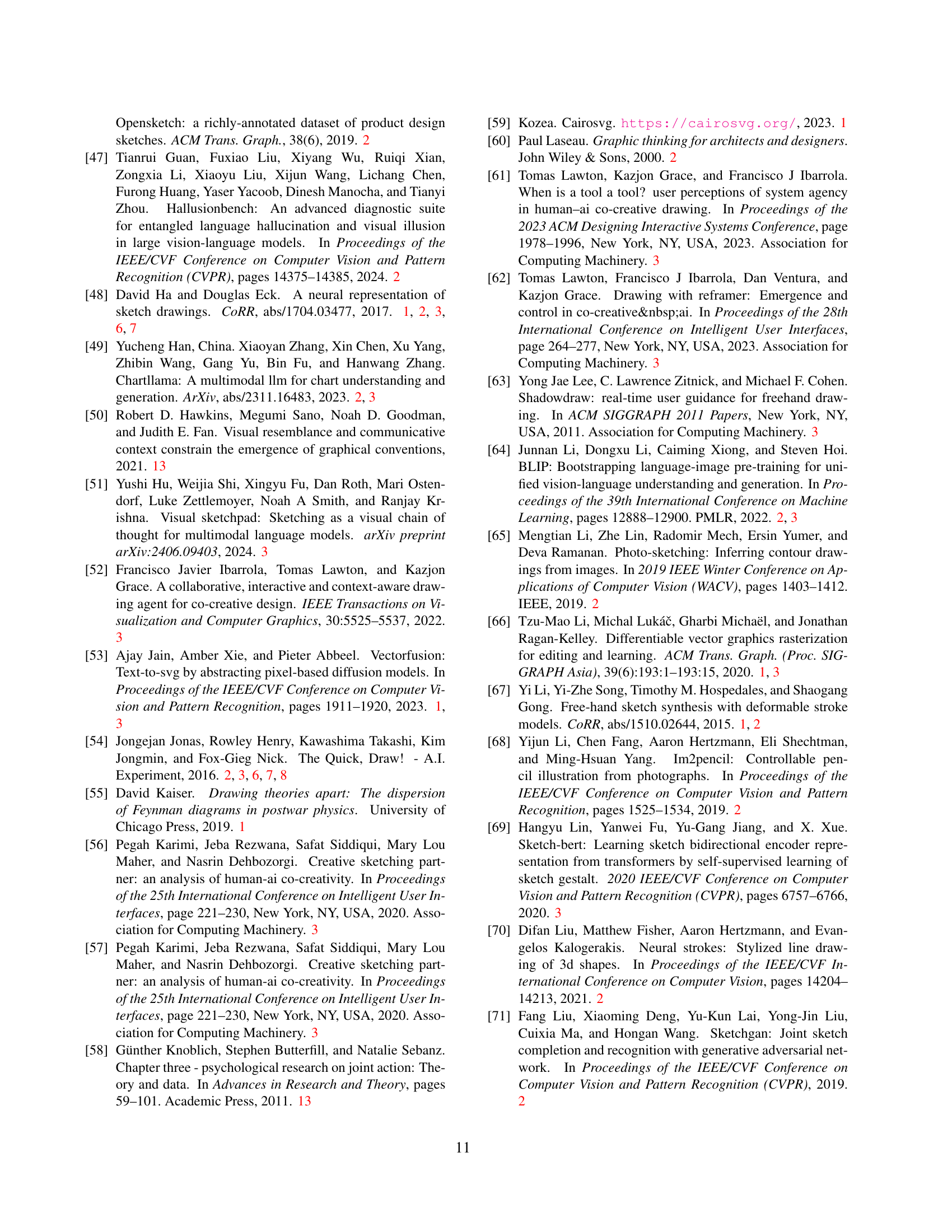

🔼 Figure 14 demonstrates limitations of SketchAgent in handling complex concepts and human figures. Panel A shows an example where the description of a unicorn is accurate, but the resulting sketch is unrecognizable due to its abstract and amateurish style. Panel B shows a similar issue with human figures, where distinctive features are captured in the text, but the sketch lacks detail and expressiveness. Panel C shows that the model struggles to represent letters and numbers.

read the caption

Figure 14: Limitations. Sketches of complex concepts (A) and human figures (B) appear too abstract and unrecognizable with non-professional style. (C) Fail to depict letters and numbers.

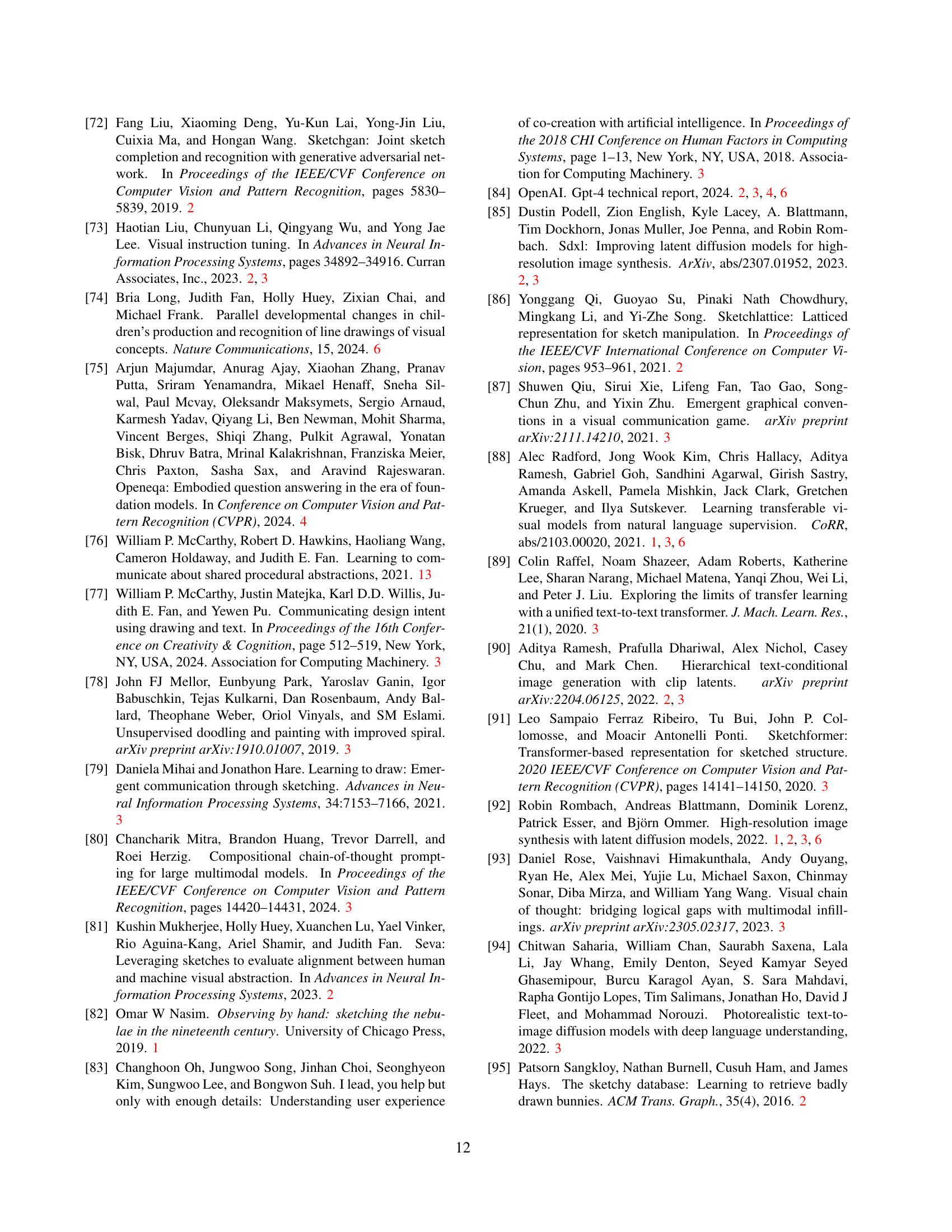

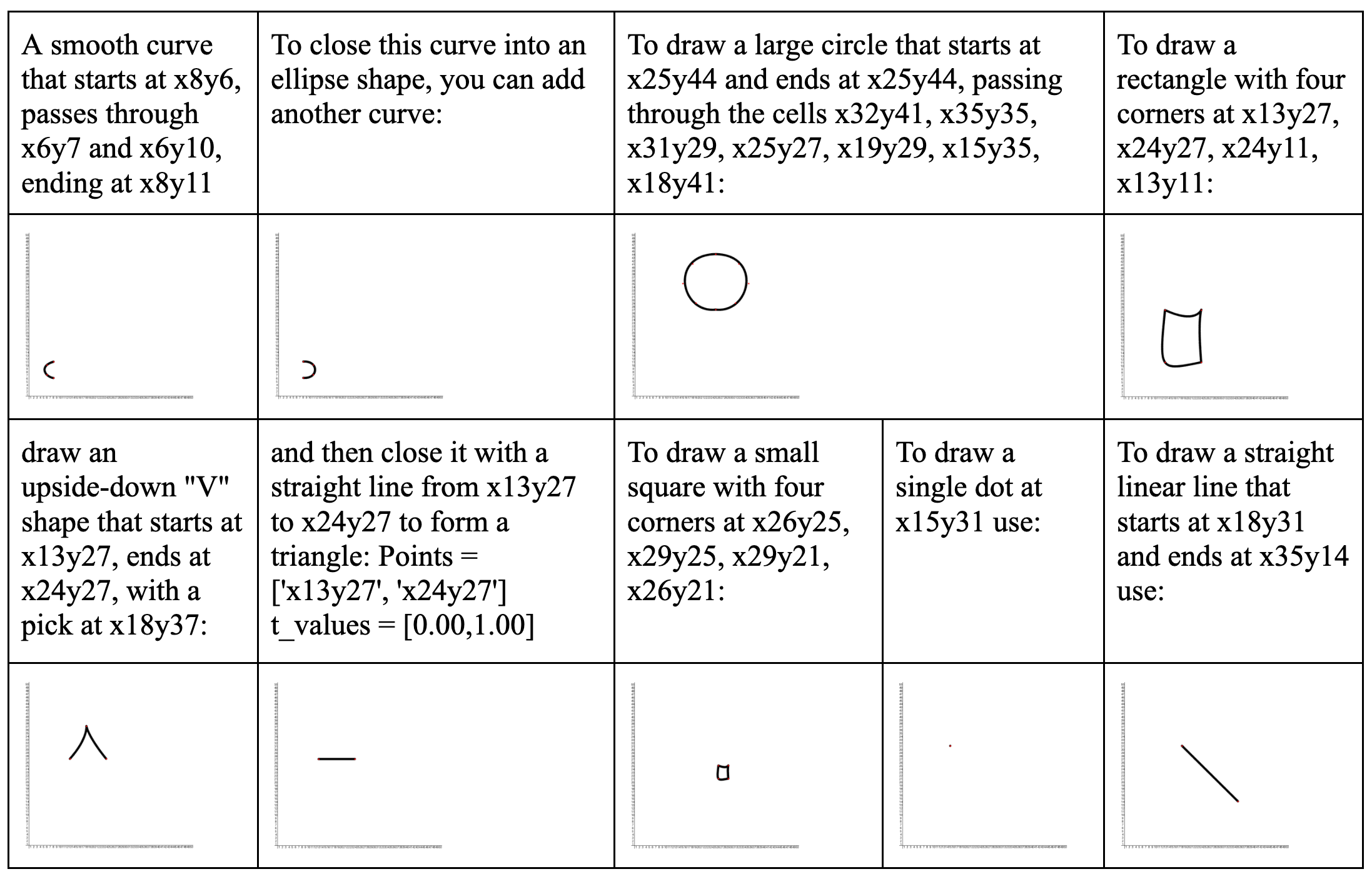

🔼 This figure shows examples of single-stroke primitives used to introduce the sketching language and grid-based canvas to the SketchAgent model. The primitives include simple shapes like lines, ellipses, and rectangles, defined using coordinate pairs and Bézier curve parameters. This introduction allows the model to understand the sketching language which enables it to generate sketches sequentially. The visual examples are meant to teach the model how to utilize this language for creating sketches in a grid-based system.

read the caption

Figure 15: Visualization of single-stroke primitives used in the system prompt to introduce the grid and sketching language to the agent.

🔼 This figure shows a simple sketch of a house, used as an in-context example within the SketchAgent model. The sketch is represented using the model’s intuitive sketching language, which consists of a numbered grid for spatial referencing and string-based actions that define strokes. The example is designed to illustrate how the model interprets this novel language for sequential sketch generation.

read the caption

Figure 16: Visualization of the simple sketch of a house provided as an in-context example, represented with our sketching language through the user prompt.

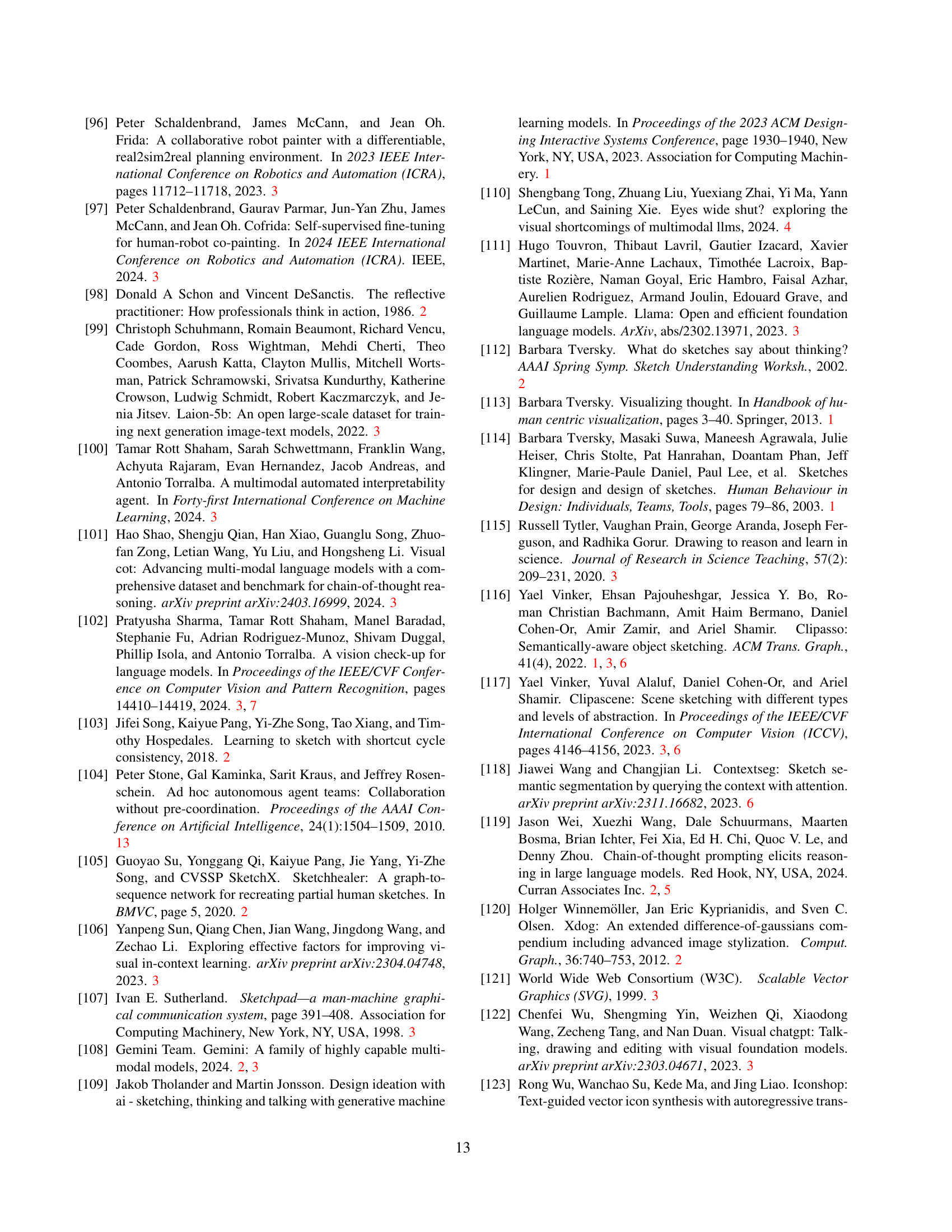

🔼 This figure demonstrates the variability of SketchAgent’s output when generating sketches for the same concept. Twelve different sketches of a rabbit were produced using the same model settings. This illustrates the creativity and flexibility of the model, as it produces diverse variations rather than repetitive or identical drawings. The differences in the sketches highlight variations in style, pose, detail, and the overall level of abstraction.

read the caption

Figure 17: Sketch variability. Example of twelve different sketches produced for the concept “rabbit” by SketchAgent, with the same settings.

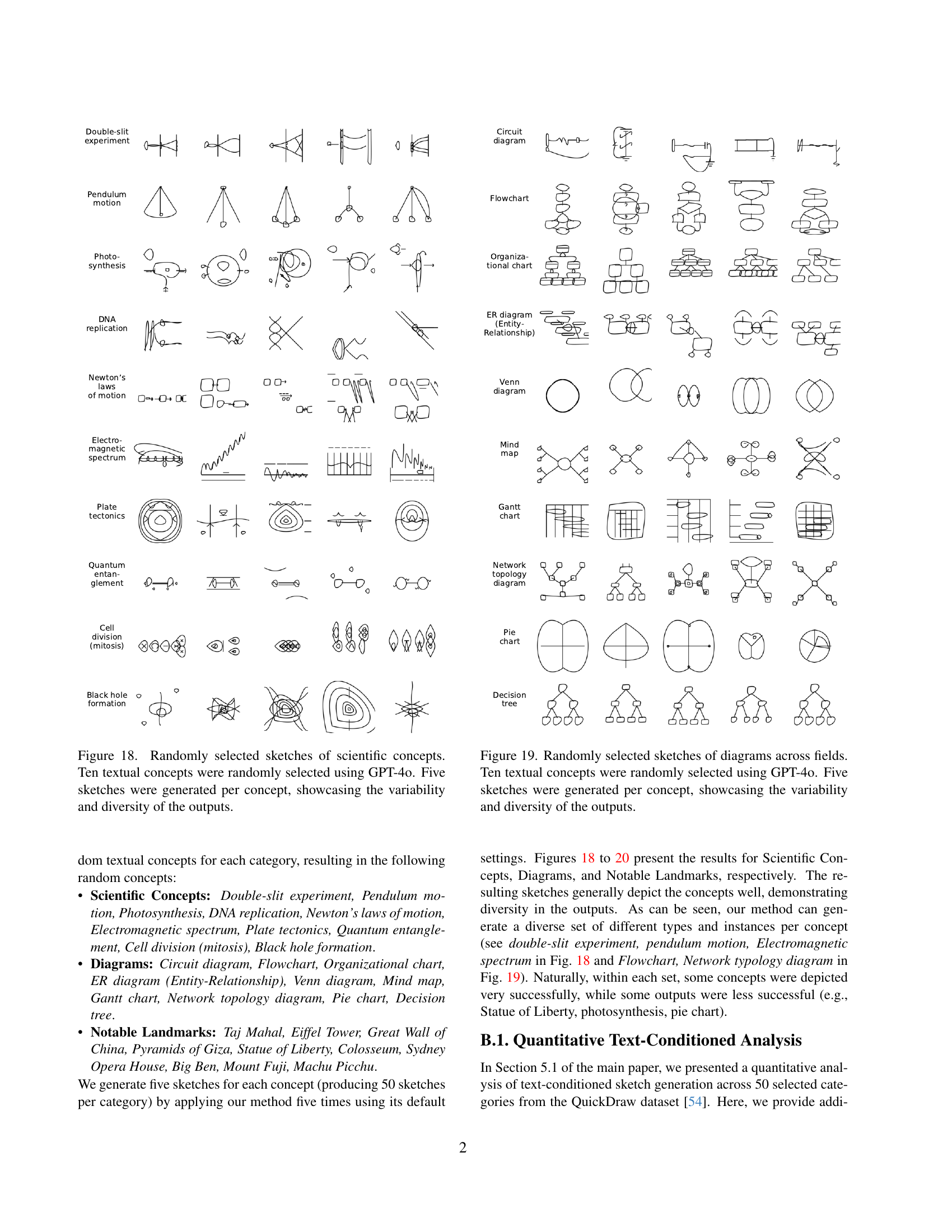

🔼 This figure displays ten scientific concepts, each represented by five different sketches generated using GPT-40. The sketches illustrate the variability and diversity achievable by the model when prompted with the same textual description.

read the caption

Figure 18: Randomly selected sketches of scientific concepts. Ten textual concepts were randomly selected using GPT-4o. Five sketches were generated per concept, showcasing the variability and diversity of the outputs.

🔼 This figure displays a collection of sketches generated by the SketchAgent model in response to prompts describing various types of diagrams. Ten different diagram types were randomly chosen, and five sketches of each were created to illustrate the variability and diversity in the model’s output. The range of diagram types demonstrates the model’s ability to generate sketches across many different fields and styles.

read the caption

Figure 19: Randomly selected sketches of diagrams across fields. Ten textual concepts were randomly selected using GPT-4o. Five sketches were generated per concept, showcasing the variability and diversity of the outputs.

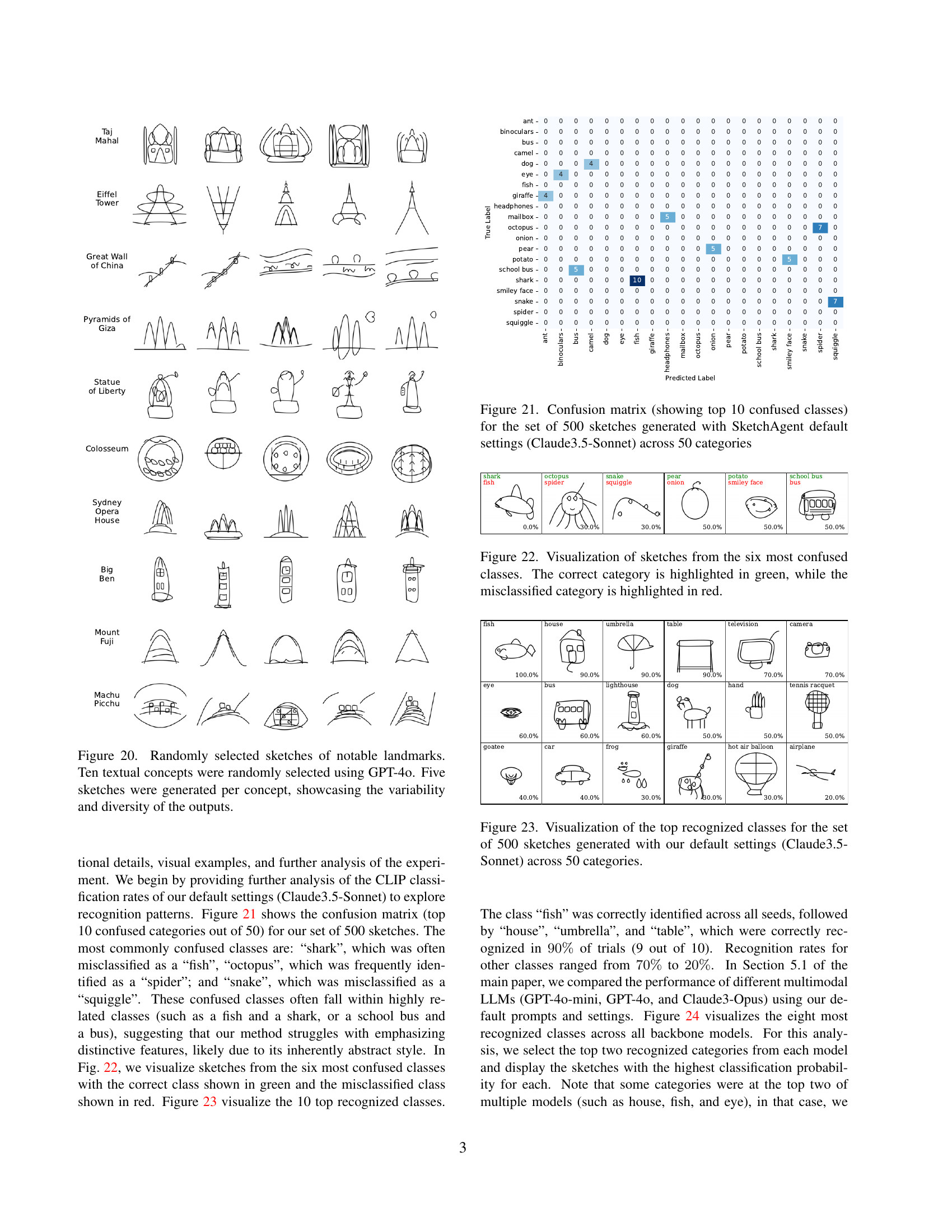

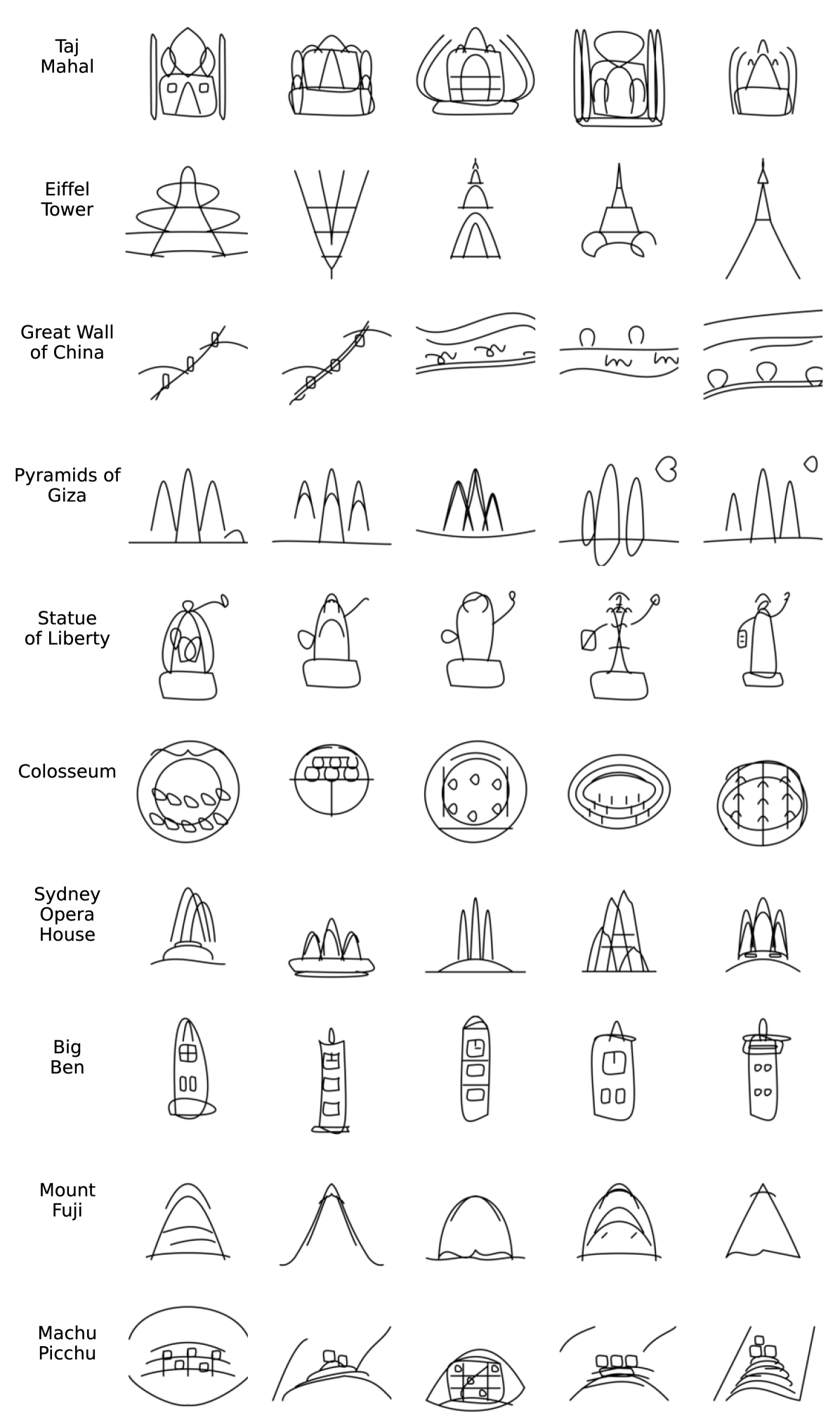

🔼 This figure displays ten randomly generated sketches of famous landmarks. Each landmark is represented by five different sketches, created using a text-to-image model (GPT-40). The variation in style and detail across the sketches highlights the model’s ability to generate diverse outputs from a single textual prompt.

read the caption

Figure 20: Randomly selected sketches of notable landmarks. Ten textual concepts were randomly selected using GPT-4o. Five sketches were generated per concept, showcasing the variability and diversity of the outputs.

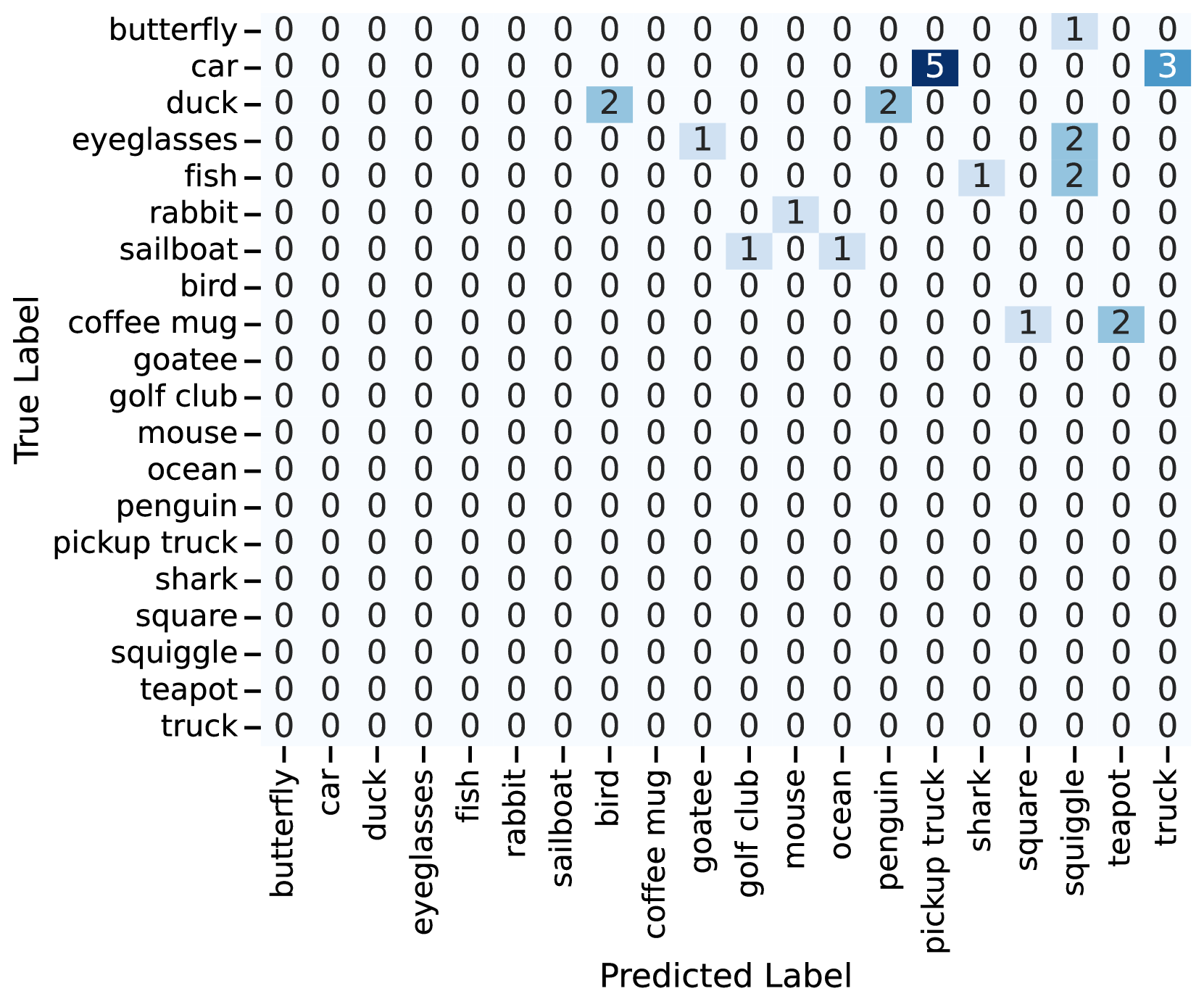

🔼 This confusion matrix visualizes the top 10 classes most frequently misclassified by SketchAgent when generating 500 sketches across 50 different categories. The model used was Claude3.5-Sonnet with default settings. The matrix shows the frequency of misclassifications between each pair of classes, highlighting which categories are most commonly confused with one another. This helps to understand the model’s limitations and potential areas for improvement.

read the caption

Figure 21: Confusion matrix (showing top 10 confused classes) for the set of 500 sketches generated with SketchAgent default settings (Claude3.5-Sonnet) across 50 categories

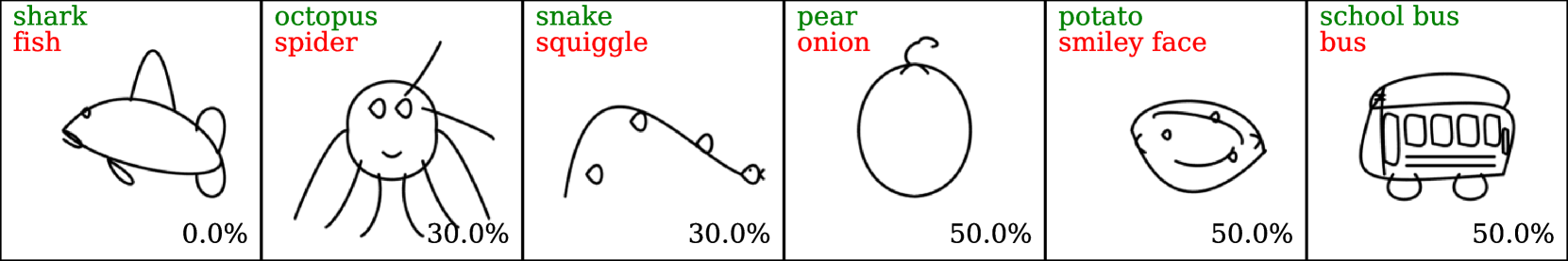

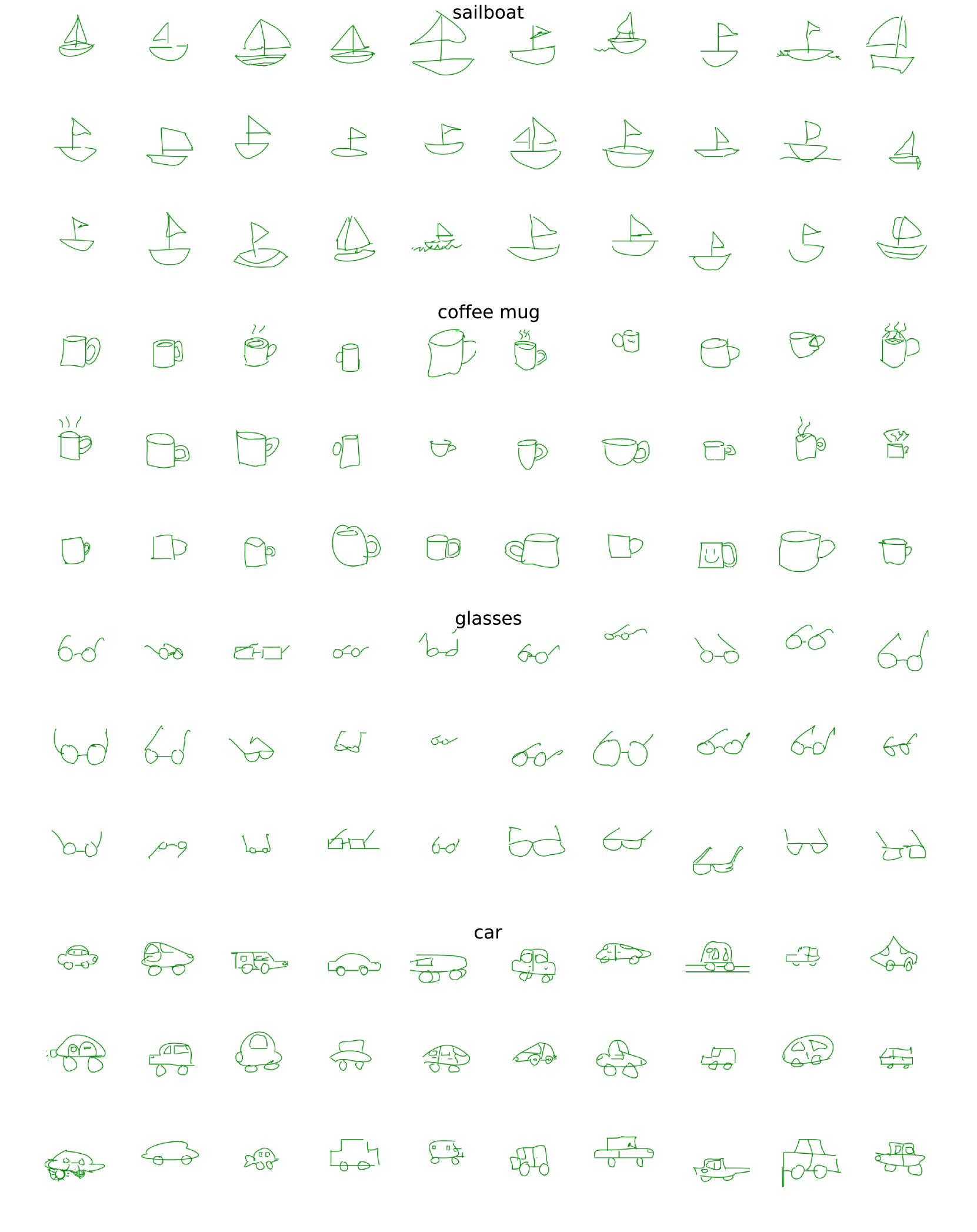

🔼 This figure visualizes examples from the six QuickDraw classes most frequently misclassified by the SketchAgent model. Each row displays ten sketches from a single class. The correct class label is shown in green at the left, while the class to which the sketches were misclassified is in red. This helps illustrate the types of visual similarities that may cause the SketchAgent model to confuse these categories.

read the caption

Figure 22: Visualization of sketches from the six most confused classes. The correct category is highlighted in green, while the misclassified category is highlighted in red.

🔼 This figure visualizes the top ten most accurately recognized QuickDraw categories from a set of 500 sketches generated using the SketchAgent model with the Claude3.5-Sonnet LLM. Each category is represented by a series of sketches, demonstrating the model’s ability to generate diverse yet recognizable representations. The visualization highlights the model’s success in producing sketches that are readily classifiable within the defined categories.

read the caption

Figure 23: Visualization of the top recognized classes for the set of 500 sketches generated with our default settings (Claude3.5-Sonnet) across 50 categories.

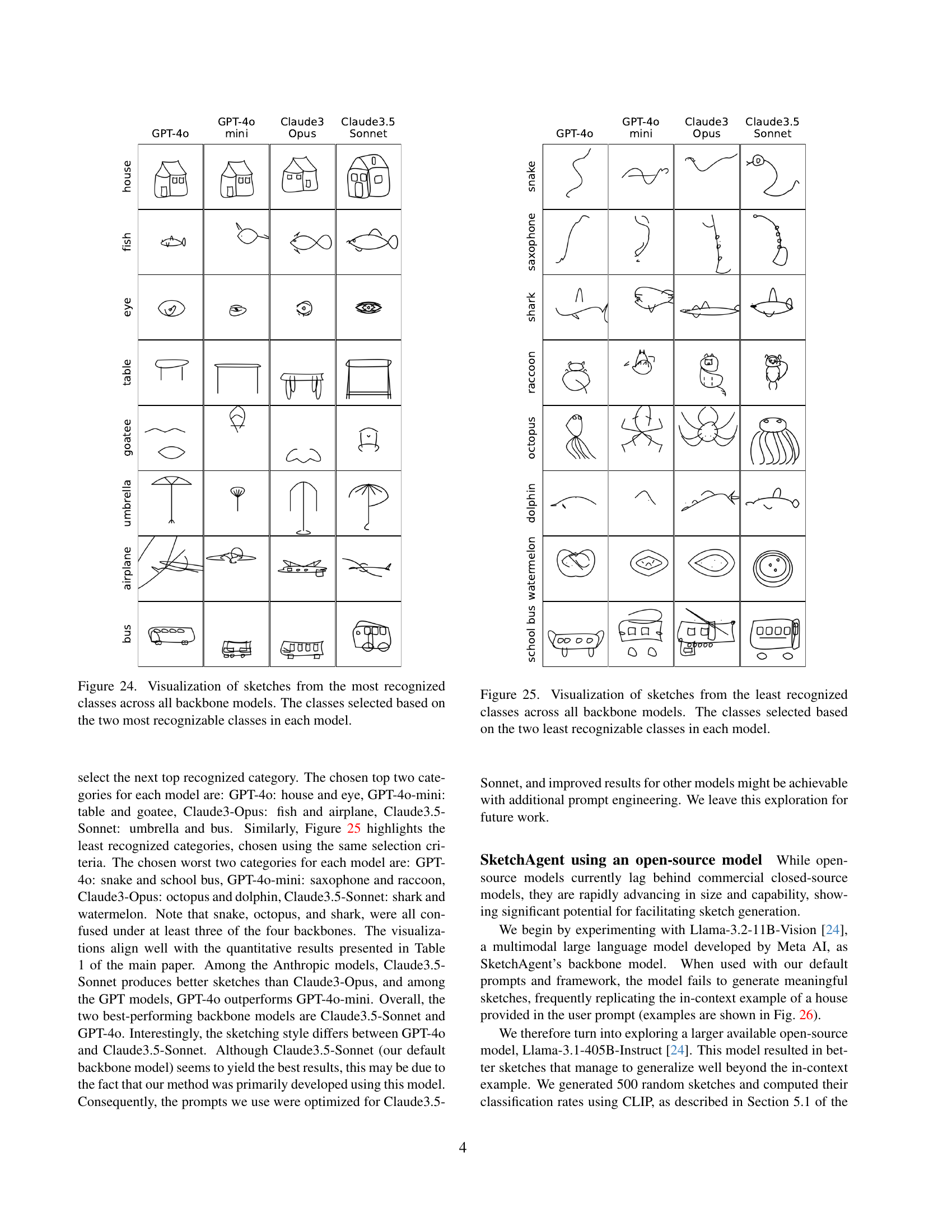

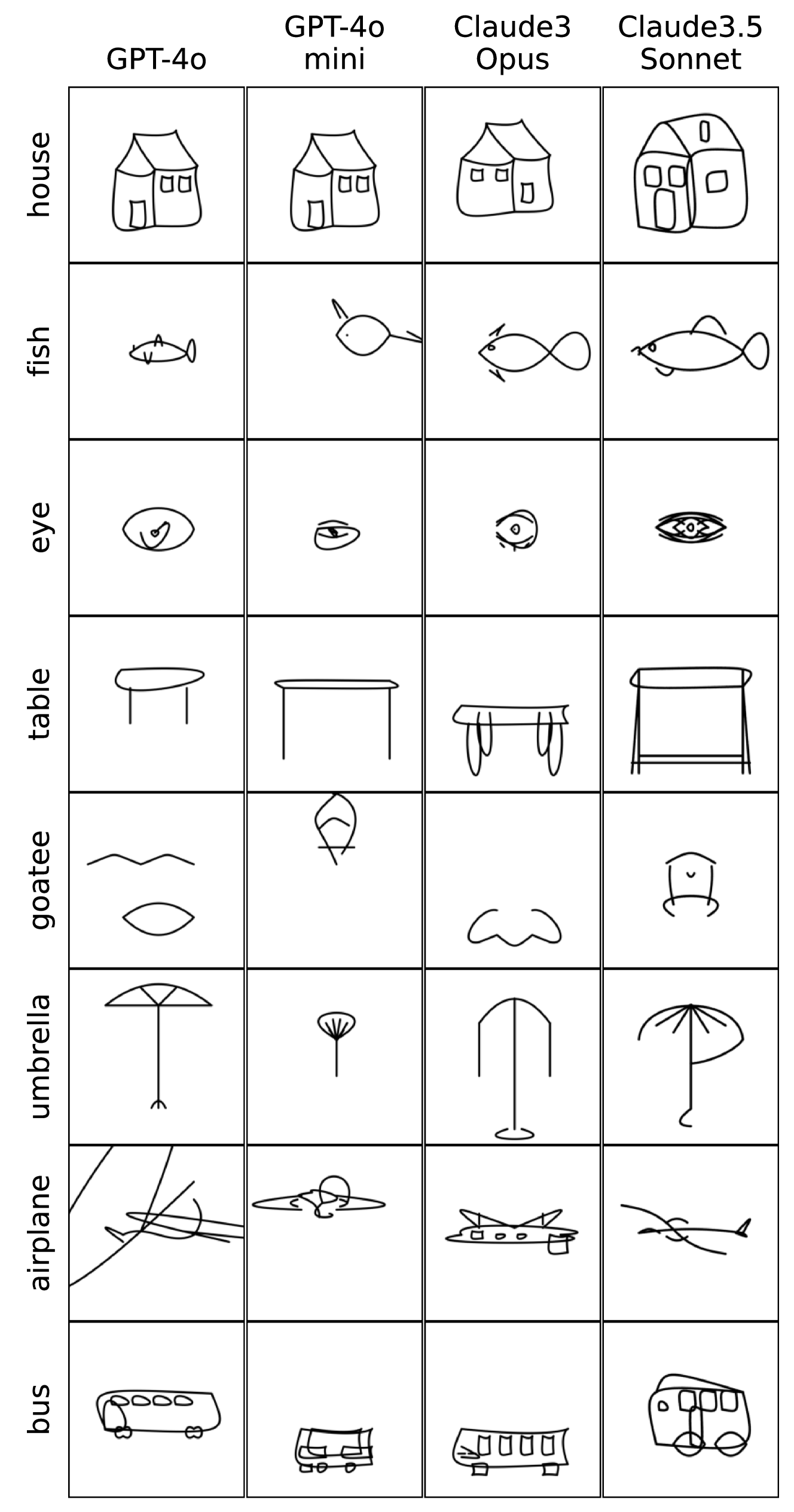

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of sketches generated by different large language models (LLMs) for the most easily recognized object categories. Each model produced ten sketches per category; the two most accurately identified categories are shown. This visualization highlights the visual differences in sketch style and accuracy across various LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 24: Visualization of sketches from the most recognized classes across all backbone models. The classes selected based on the two most recognizable classes in each model.

🔼 This figure displays sketches generated by four different large language models (LLMs) for the two least accurately recognized object categories by a CLIP zero-shot classifier. The LLMs used were GPT-40, GPT-40-mini, Claude3-Opus, and Claude3.5-Sonnet. The purpose is to visually compare the generated sketches across different models, highlighting the variations in style, detail, and accuracy in representing the intended object. The selected categories are those consistently showing low recognition accuracy across models, demonstrating the challenges in generating visually accurate and recognizable sketches with these models.

read the caption

Figure 25: Visualization of sketches from the least recognized classes across all backbone models. The classes selected based on the two least recognizable classes in each model.

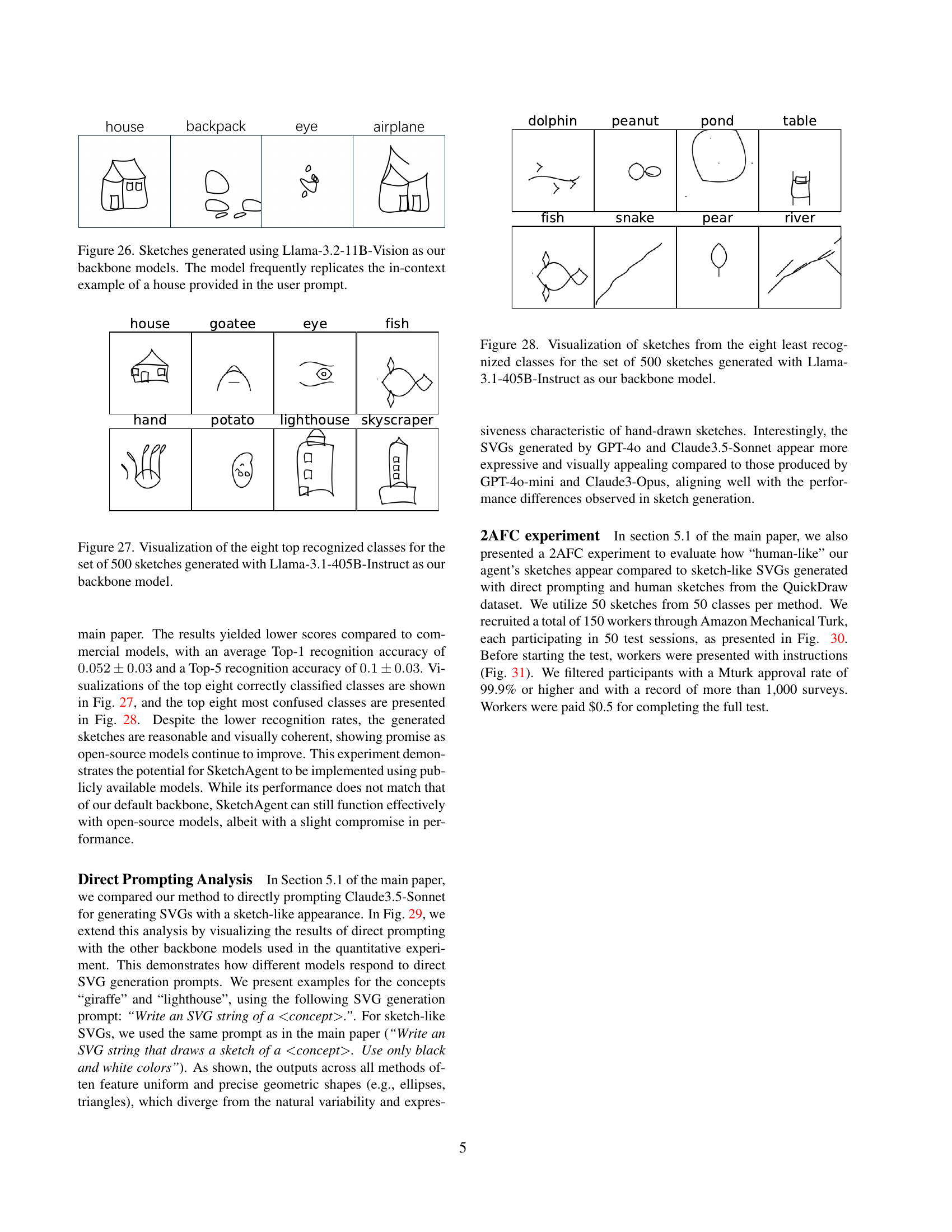

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of using Llama-3.2-11B-Vision, an open-source large language model, within the SketchAgent framework. It highlights a key limitation of using open-source models: a tendency to over-rely on the in-context examples provided during prompting. The sketches generated frequently replicate the house example provided earlier, demonstrating that the model hasn’t fully grasped the concept of general sketch generation. This is in contrast to the results obtained with more advanced, closed-source models where greater diversity in sketch generation is observed.

read the caption

Figure 26: Sketches generated using Llama-3.2-11B-Vision as our backbone models. The model frequently replicates the in-context example of a house provided in the user prompt.

🔼 This figure visualizes the eight QuickDraw classes most accurately recognized by SketchAgent when using the Llama-3.1-405B-Instruct model. It showcases ten example sketches per class, illustrating the model’s ability to generate diverse and recognizable images for those specific categories. The model’s performance is particularly strong for these eight classes.

read the caption

Figure 27: Visualization of the eight top recognized classes for the set of 500 sketches generated with Llama-3.1-405B-Instruct as our backbone model.

🔼 This figure visualizes sketches generated by the SketchAgent model using the Llama-3.1-405B-Instruct large language model. Specifically, it shows examples from the eight categories that were least accurately recognized by a CLIP classifier. This highlights the model’s struggles with certain object categories, indicating areas where the model’s visual understanding could be improved. The visualization helps understand the types of sketches the model produces for difficult object classes, providing insight into model limitations.

read the caption

Figure 28: Visualization of sketches from the eight least recognized classes for the set of 500 sketches generated with Llama-3.1-405B-Instruct as our backbone model.

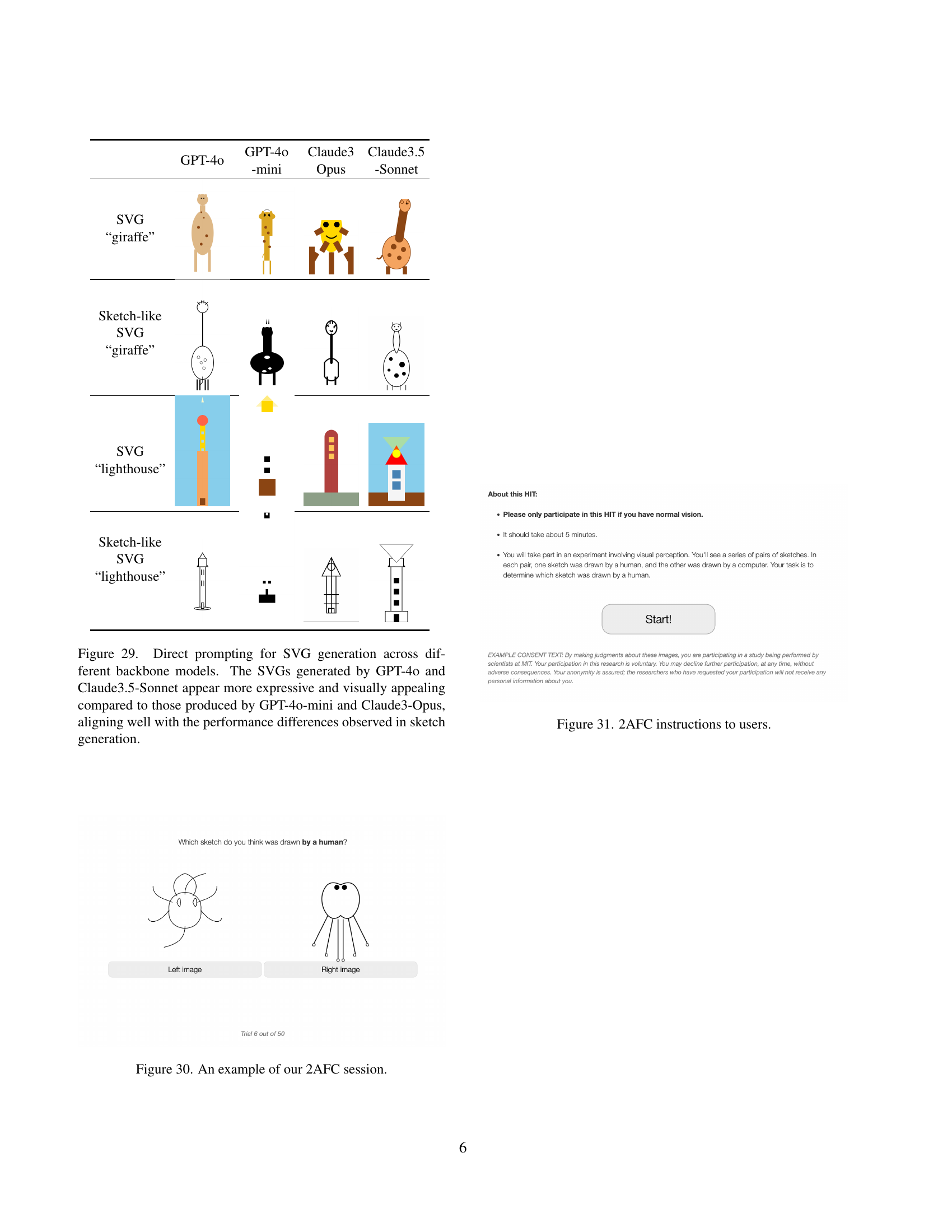

🔼 This figure compares the results of directly prompting four different large language models (LLMs) to generate Scalable Vector Graphics (SVGs) that resemble sketches. The LLMs used were GPT-4, GPT-4 mini, Claude 3.5-Sonnet, and Claude Opus. The comparison highlights that GPT-4 and Claude 3.5-Sonnet produce SVGs with a more expressive and visually appealing style than the other two models. This difference in visual quality correlates with the overall performance differences observed in the sketch generation experiments reported in the paper, where Claude 3.5-Sonnet showed superior results.

read the caption

Figure 29: Direct prompting for SVG generation across different backbone models. The SVGs generated by GPT-4o and Claude3.5-Sonnet appear more expressive and visually appealing compared to those produced by GPT-4o-mini and Claude3-Opus, aligning well with the performance differences observed in sketch generation.

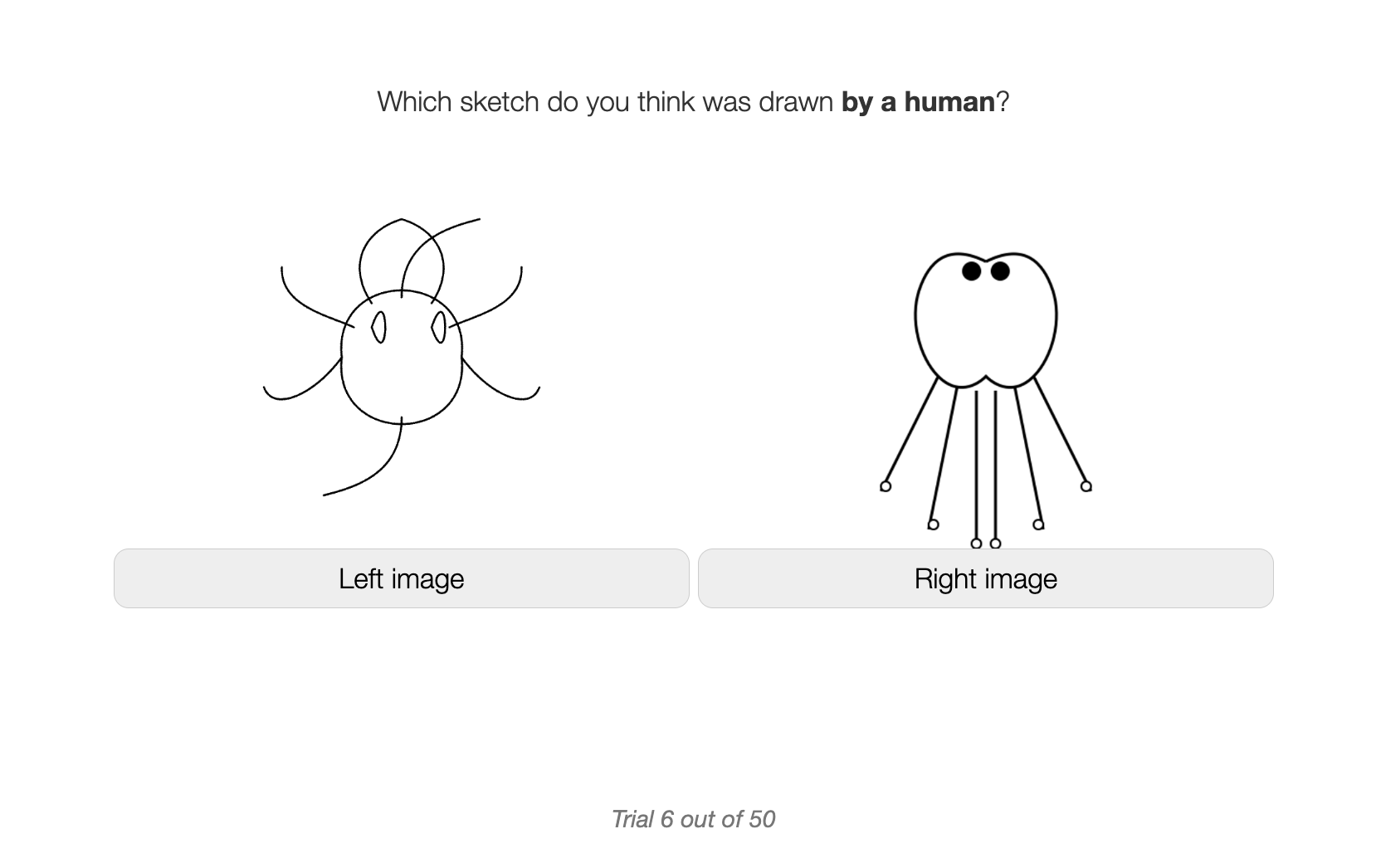

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of a two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) user study session. In this type of study, participants are presented with pairs of images and asked to choose which image belongs to a certain category. This particular screenshot shows one trial, where one image was created by a human and the other by a computer model. The participant must select which of the two images is the human drawing. This type of experiment helps to assess the human-likeness of computer-generated images and how well they can mimic human-created content.

read the caption

Figure 30: An example of our 2AFC session.

🔼 The figure shows the instructions given to participants in a two-alternative forced choice (2AFC) user study. Participants were shown pairs of sketches, one created by a human and the other by a computer, and asked to identify the human-drawn sketch. The instructions emphasized the voluntary nature of participation and assured anonymity.

read the caption

Figure 31: 2AFC instructions to users.

🔼 Figure 32 presents a comparative analysis of stroke distributions in human-drawn sketches from the QuickDraw dataset and those generated by SketchAgent. The top half shows the distribution of strokes in human sketches, while the bottom half displays the distribution for SketchAgent-generated sketches. Histograms illustrate the frequency of sketch complexity, measured by the number of strokes used. Representative examples for sketches with 1, 4, 7, and 15 strokes are shown for both human and SketchAgent outputs. A key observation is that human sketches, particularly those with only a single stroke, often consist of a single, continuous line.

read the caption

Figure 32: Distribution of human sketches [54] (top) and SketchAgent’s sketches (bottom) based on the number of strokes per sketch. Representative examples are shown for sketches drawn with 1, 4, 7, and 15 strokes. Notably, in the QuickDraw dataset, single-stroke sketches often consist of a single long continuous line.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of how humans and the SketchAgent AI system create drawings. It focuses on the sequential nature of sketching, showing the steps involved in drawing three different objects: a pear, a purse, and a screwdriver. Four strokes are shown for each object for both human and AI-generated drawings, allowing a visual comparison of the process and the style of each. The human drawings are taken from the QuickDraw dataset.

read the caption

Figure 33: Sequential four-stroke sketches of a pear, purse, and screwdriver, created by humans [54] and by SketchAgent.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of sequential sketching. It displays five-stroke sketches of a pear, purse, and screwdriver drawn by humans (from the QuickDraw dataset) alongside sketches generated by the SketchAgent model. This comparison highlights the model’s ability to mimic the sequential and iterative nature of human sketching. The evolution of the sketches from simple initial strokes to more complex shapes is visible for both human and model-generated examples.

read the caption

Figure 34: Sequential five-stroke sketches of a pear, purse, and screwdriver, created by humans [54] and by SketchAgent.

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of six-stroke sketches of a television, bed, and peanut. The sketches on the left were created by humans, taken from the QuickDraw dataset [54]. The sketches on the right were generated by the SketchAgent model. This visualization highlights the differences between human sketching and the model’s sequential stroke-by-stroke generation process.

read the caption

Figure 35: Sequential six-stroke sketches of a television, bed, and peanut, created by humans [54] and by SketchAgent.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of seven-stroke sketches of a backpack, fish, and house, drawn by humans and SketchAgent. It illustrates the sequential nature of SketchAgent’s drawing process, showing how the model builds the sketch stroke-by-stroke, as opposed to generating the entire image at once. The human sketches, sourced from the QuickDraw dataset, offer a baseline for natural, human-like sketching style. The comparison highlights the similarities and differences in the approaches to generating sketches.

read the caption

Figure 36: Sequential seven-stroke sketches of a backpack, fish, and house, created by humans [54] and by SketchAgent.

More on tables

| (B) LLMs [3] | |

|---|---|

| (SVG) |

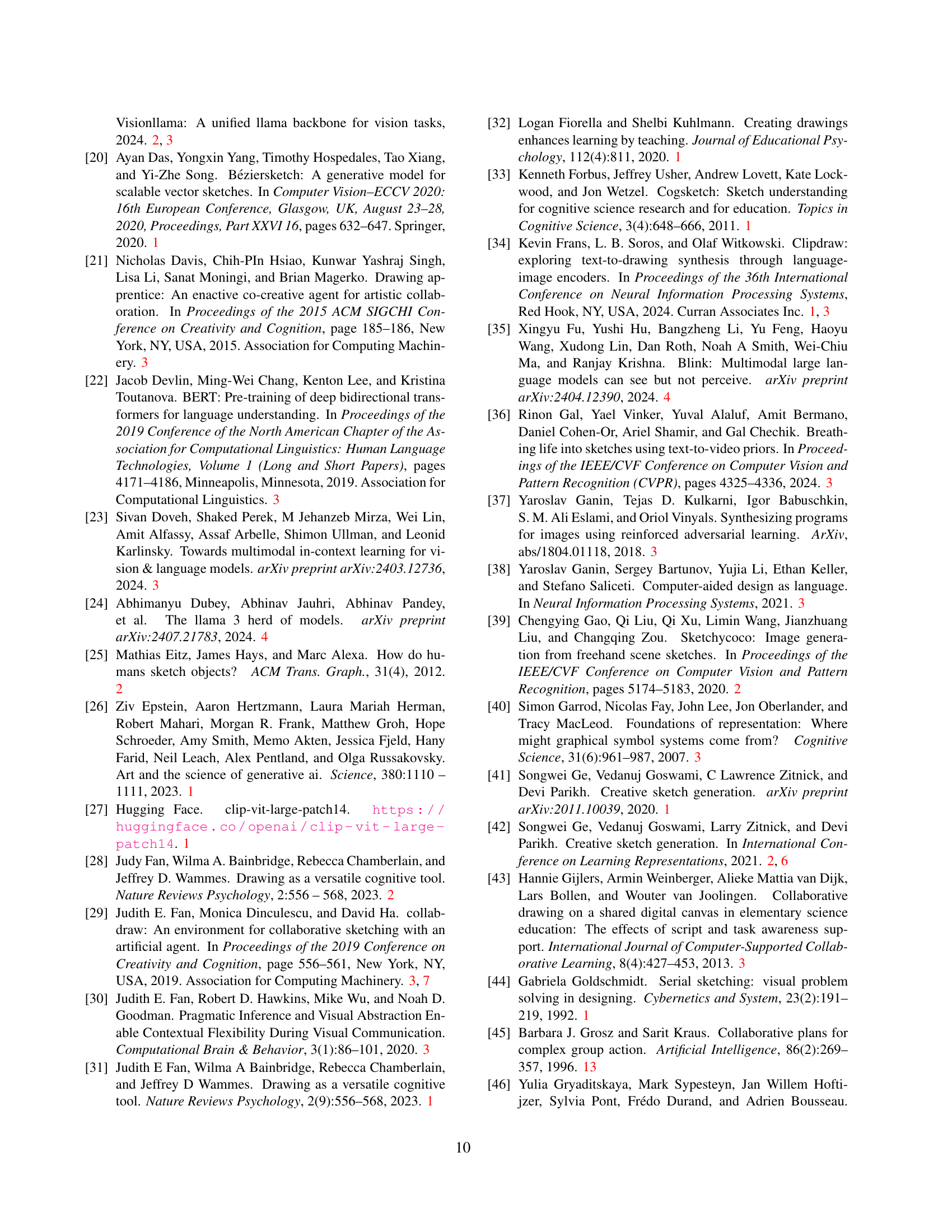

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to evaluate the impact of each component within the SketchAgent pipeline on its overall performance. The study systematically removed each component (system prompt, chain-of-thought prompting, and the in-context learning example) one at a time, measuring the resulting Top-1 and Top-5 CLIP recognition accuracy. The results demonstrate the contribution of each component to the model’s ability to generate high-quality sketches.

read the caption

Table 2: Ablation study. Average Top-1 and Top-5 CLIP recognition accuracy. We systematically remove each component in our pipeline, showcasing all components contribute to the agent’s full performance.

| Image | Caption |

|---|---|

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/output_Golden_Gate_Bridge.png | Golden Gate Bridge |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/output_Mount_Fuji.png | Mount Fuji |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/output_Eiffel_Tower.png | Eiffel Tower |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/output_DNA_Double_Helix.png | DNA Double Helix |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/Pendulum_Motion_plain_0.png | Pendulum Motion |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/The_Double-Slit_Experiment_plain_0.png | Double-Slit Experiment |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/output_Flowchart.png | Flowchart |

| https://arxiv.org/html/2411.17673/x_wins.png | Tic-tac-toe |

🔼 This table presents the results of a quantitative analysis evaluating the effectiveness of collaborative sketching between humans and the SketchAgent model. It shows the recognition accuracy (with 95% confidence intervals) for three conditions: complete collaborative sketches, sketches with only the agent’s strokes, and sketches with only the user’s strokes. The results demonstrate the synergistic nature of the collaboration, showing that complete collaborative sketches achieve significantly higher recognition rates compared to sketches generated by either humans or the agent alone. This highlights the importance of both human and agent contributions for achieving meaningful results in collaborative sketching.

read the caption

Table 3: Recognition rate and 95% CI across collaborative full and partial sketches. In collaborative sketches, keeping agent-only strokes or user-only strokes significantly reduces recognizability.

Full paper#