↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Creating animatable 3D characters usually involves extensive manual work for rigging and skinning. Existing automated tools often have limitations, such as requiring manual annotations or being restricted to specific character types and poses. This limits their effectiveness and practicality for modern creative industries that require a wide variety of character designs and animation styles.

This paper introduces Make-It-Animatable, a data-driven method that significantly speeds up the process. It generates high-quality rigging, skinning, and pose transformations in less than one second, regardless of the input character’s shape or pose. The framework uses a particle-based shape autoencoder and structure-aware modeling to ensure both accuracy and robustness, even with unconventional character designs. This offers a significant improvement over existing methods in both speed and quality, opening up exciting new possibilities for applications requiring rapid and highly customizable character animations, such as virtual reality, video games, and real-time simulations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents Make-It-Animatable, a novel and efficient framework for creating animation-ready 3D characters. It addresses the long-standing challenge of rigging and skinning, which is a significant bottleneck in 3D animation. The framework’s speed and ability to handle diverse character designs make it highly relevant to various industries, such as gaming and virtual reality. It also opens up new avenues for research in automatic animation and data-driven character modeling, potentially impacting how 3D characters are created and animated in the future.

Visual Insights#

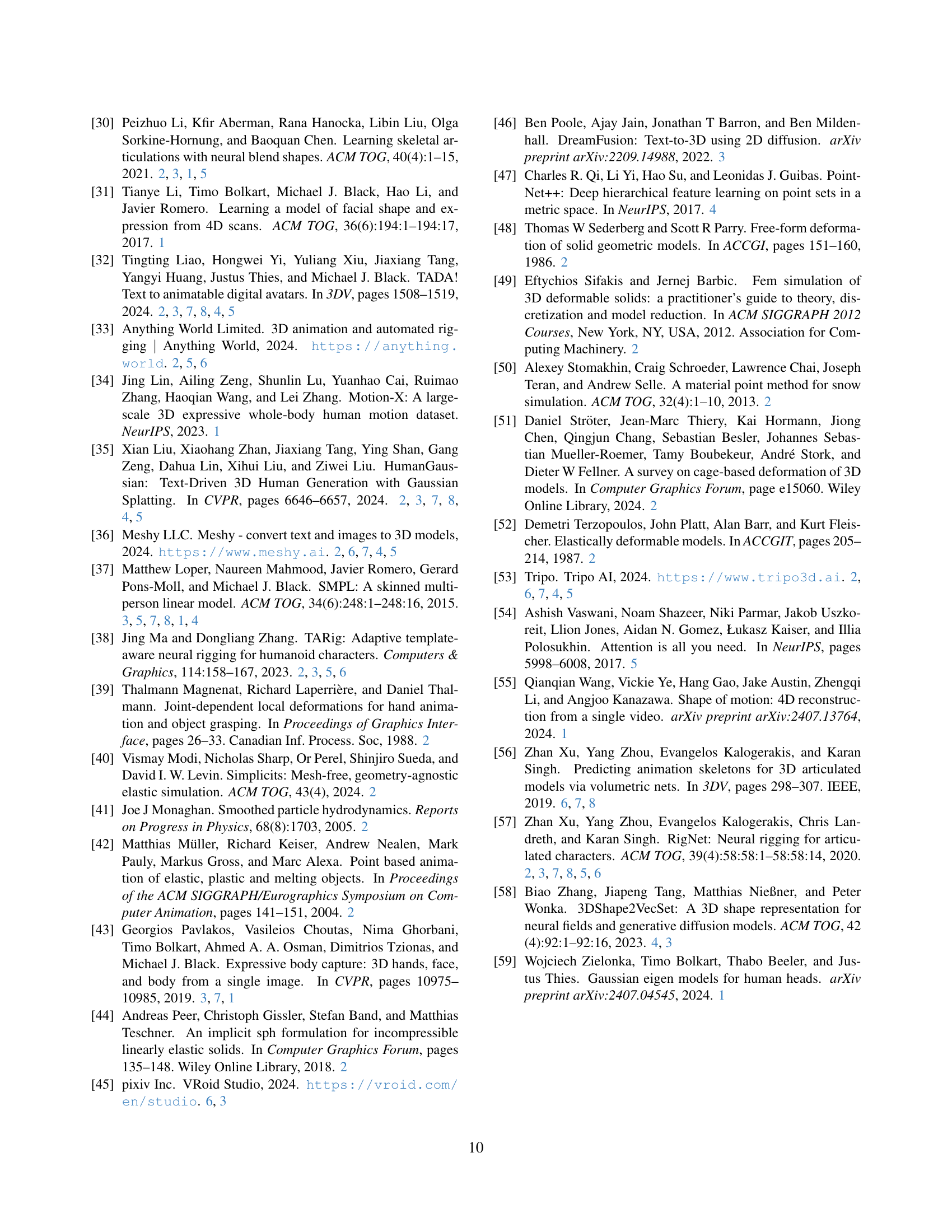

🔼 This figure shows the input and output of the proposed Make-It-Animatable framework. Given a 3D character model (either a mesh or a point cloud represented by 3D Gaussian Splats), regardless of its pose or shape, the system automatically generates a rig, performs skinning, and resets the pose to a neutral position, all within one second. The resulting model has a detailed skeleton and allows for animation. The framework can even handle characters with extra body parts (like ears or tails) not typically found in standard humanoid models.

read the caption

Figure 1: Given a 3D character represented by mesh or 3D Gaussian Splats with arbitrary pose and shape, our framework can produce high-quality results of rigging, skinning, and pose resetting for it within one second. The output 3D model is fully animatable with a fine-grained skeleton and optional bone topology of extra body structures.

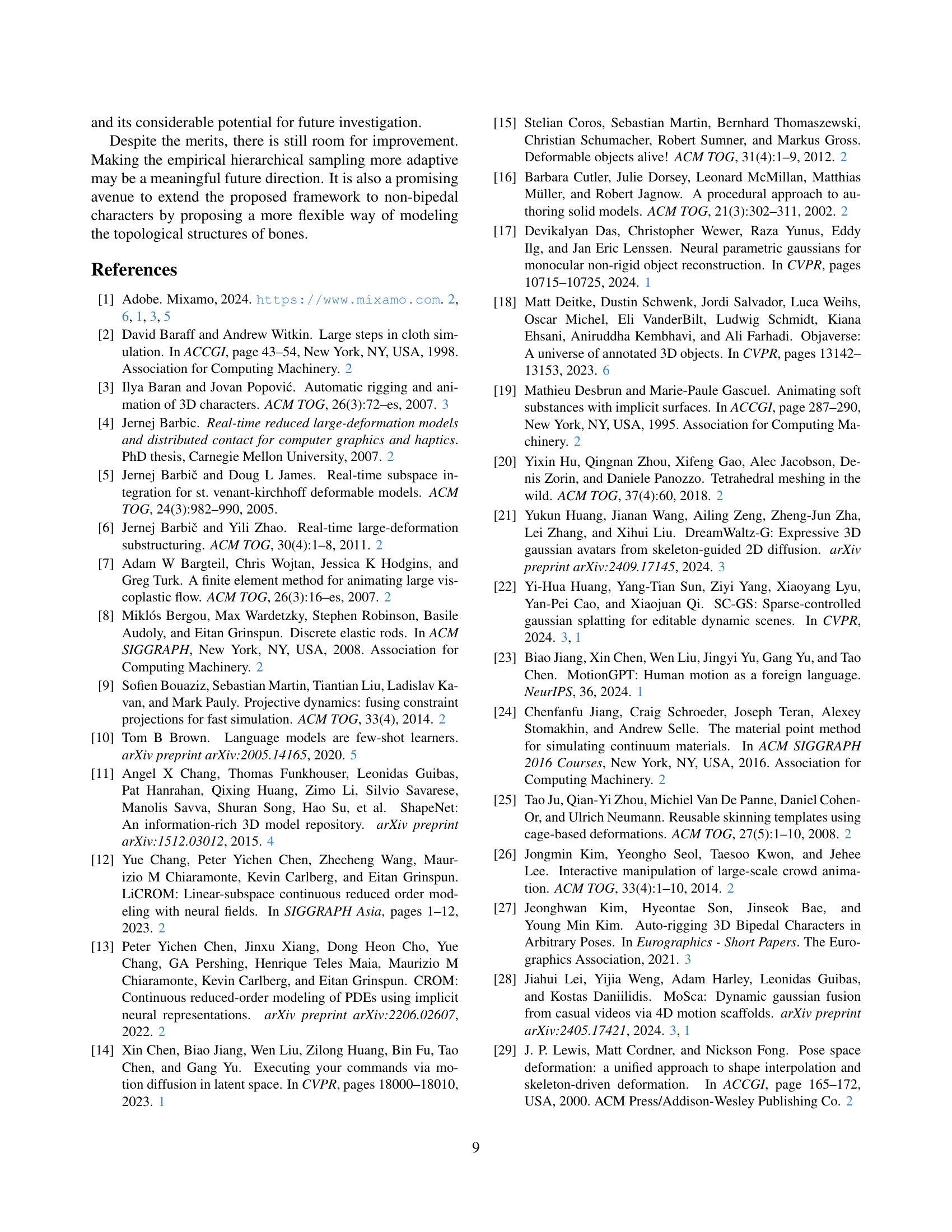

| Categories | Methods | Mesh | 3DGS | TemplateFree | AlterableSkeleton | Pose to Rest | Hand Animation | RiggingTime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text/Image to Animatable | Meshy† [meshy] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ~ 3 min |

| Tripo† [tripo] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ~ 3 min | |

| Auto Rigging | Mixamo† [mixamo] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓¹ | ✓ | ~ 2 min |

| Anything World† | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓¹ | ✓ | ~ 4 min | |

| RigNet [xu2020rignet] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ~ 10 min | |

| TARig [ma2023tarig] | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ~ 0.6 min | |

| Template-based Animatable | TADA [liao2024tada] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | – | ✓ | – |

| HumanGaussian [liu2024humangaussian] | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | – | ✗ | – | |

| Ours | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ~ 0.5 s |

🔼 This table compares the proposed method with several existing approaches for creating animation-ready 3D characters, highlighting key differences in features. The comparison covers support for various 3D model representations (meshes and 3D Gaussian Splats), the ability to handle arbitrary character poses, the availability of a free or constrained skeleton, whether a rest pose is generated, the overall animation time, and the use of manual annotations.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison between our method and existing approaches in terms of key features.

In-depth insights#

Animatable 3D Char#

The concept of ‘Animatable 3D Characters’ represents a significant advancement in computer graphics and animation. Creating realistic and expressive 3D characters that can convincingly move and interact within a virtual environment requires solving several complex technical challenges. Rigging and skinning are crucial processes: rigging establishes the underlying skeletal structure, while skinning defines how the character’s surface deforms in response to skeletal movements. Traditional methods rely heavily on manual artistry, which is time-consuming and expensive. The research paper explores efficient data-driven approaches to automate these processes. The innovation lies in techniques that allow for rapid and accurate rigging and skinning, handling diverse character designs and poses, including those with non-standard anatomies or extreme proportions. Particle-based shape encoding, coupled with structure-aware modelling, may address limitations of traditional mesh-based methods, resulting in greater flexibility and efficiency. The speed with which this automation can be performed is highlighted as a key achievement, enabling applications requiring real-time or interactive character animation. The overall impact is to lower the barrier to entry for character animation, accelerating development workflows in fields such as gaming and virtual reality.

Particle-Based AE#

The heading ‘Particle-Based AE,’ likely referring to a Particle-Based Autoencoder, suggests a novel approach to representing 3D character geometry. This method likely leverages the power of autoencoders, neural networks trained to learn compressed representations of data, but adapts them to handle particle-based representations of 3D shapes. This is significant because particle systems offer flexibility in representing complex shapes and deformations, unlike mesh-based methods which can struggle with highly detailed or irregular surfaces. The autoencoder likely compresses the high-dimensional particle data into a lower-dimensional latent space, capturing the essential features of the character’s shape. This compressed representation can then be decoded to reconstruct the original particle data, potentially allowing for manipulations and animations. The advantage of this approach is that it can handle various input formats, not just meshes. The use of a particle-based system likely makes the method robust to noise, variations, and non-uniform sampling of points, ensuring greater generalization. Further, this approach could facilitate efficient processing compared to other methods, particularly useful for real-time applications requiring fast rigging and animation. The focus on particles offers advantages in terms of flexibility and scalability, especially when dealing with high-resolution models or complex animations. The effectiveness of this approach would depend on the architecture of the autoencoder, the choice of loss function, and the training data used.

Coarse-to-Fine Rig#

The concept of a “Coarse-to-Fine Rig” in 3D character animation suggests a hierarchical approach to rigging, improving both accuracy and efficiency. A coarse stage initially identifies major skeletal features, providing a foundational structure. This initial, approximate rigging is computationally inexpensive and focuses on the overall pose and proportions. Subsequently, a fine-tuning phase refines the details, particularly in areas such as hands and fingers, which are challenging due to their intricate geometry and high degrees of freedom. This two-stage approach leverages the strengths of both speed (coarse) and precision (fine). The coarse stage offers a robust initial guess, minimizing the computational burden on the refinement process. The fine stage builds upon this foundation to handle complex, fine-grained structures accurately, rather than starting from scratch. This strategy is particularly valuable for handling various poses and character morphologies, making it versatile and efficient. Overall, a Coarse-to-Fine Rig offers a powerful and practical solution for building animatable 3D characters quickly and accurately.

Structure-Aware Model#

The concept of a ‘Structure-Aware Model’ in the context of 3D character animation is crucial for achieving natural and realistic movements. A standard approach, like Linear Blend Skinning (LBS), often falls short when dealing with characters possessing unconventional morphologies or poses. Structure awareness addresses this limitation by explicitly incorporating skeletal topology and relationships into the animation process. This is achieved by integrating the hierarchical relationships between bones (parent-child connections) directly into the model’s architecture. This approach is in contrast to methods that treat bone transformations independently, thereby potentially leading to unnatural or disconnected movements. By encoding skeletal structure, the model can predict bone transformations that are contextually appropriate, resulting in more lifelike deformations. Causal attention mechanisms are particularly useful in this context, allowing the model to leverage information from ancestral bones to accurately predict the pose of descendant bones, mirroring the natural biomechanical constraints of a skeleton. The effectiveness of this strategy is demonstrated through enhanced accuracy and naturalness in character animations, particularly in challenging areas such as finger articulation and complex poses.

Future Works#

Future work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework’s adaptability to non-bipedal characters is crucial, requiring modifications to the skeleton representation and potentially incorporating alternative rigging techniques. Improving the handling of highly detailed or complex geometries would enhance the system’s versatility, addressing potential challenges in accurately capturing fine details during rigging and skinning. This might involve exploring advanced mesh processing methods or incorporating higher-resolution input representations. The current method employs a fixed skeleton topology, which limits flexibility. Investigating methods for learning or automatically generating appropriate skeleton structures would enhance the framework’s capacity for diverse character types. Incorporating physics simulation into the animation process would create a more realistic and dynamic outcome. This would add complexity, but could significantly improve the quality of character animation. Finally, the efficiency of the framework could be further optimized, potentially through exploring more efficient deep learning architectures or algorithmic improvements. These refinements could make the tool even more practical for real-time applications and large-scale productions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

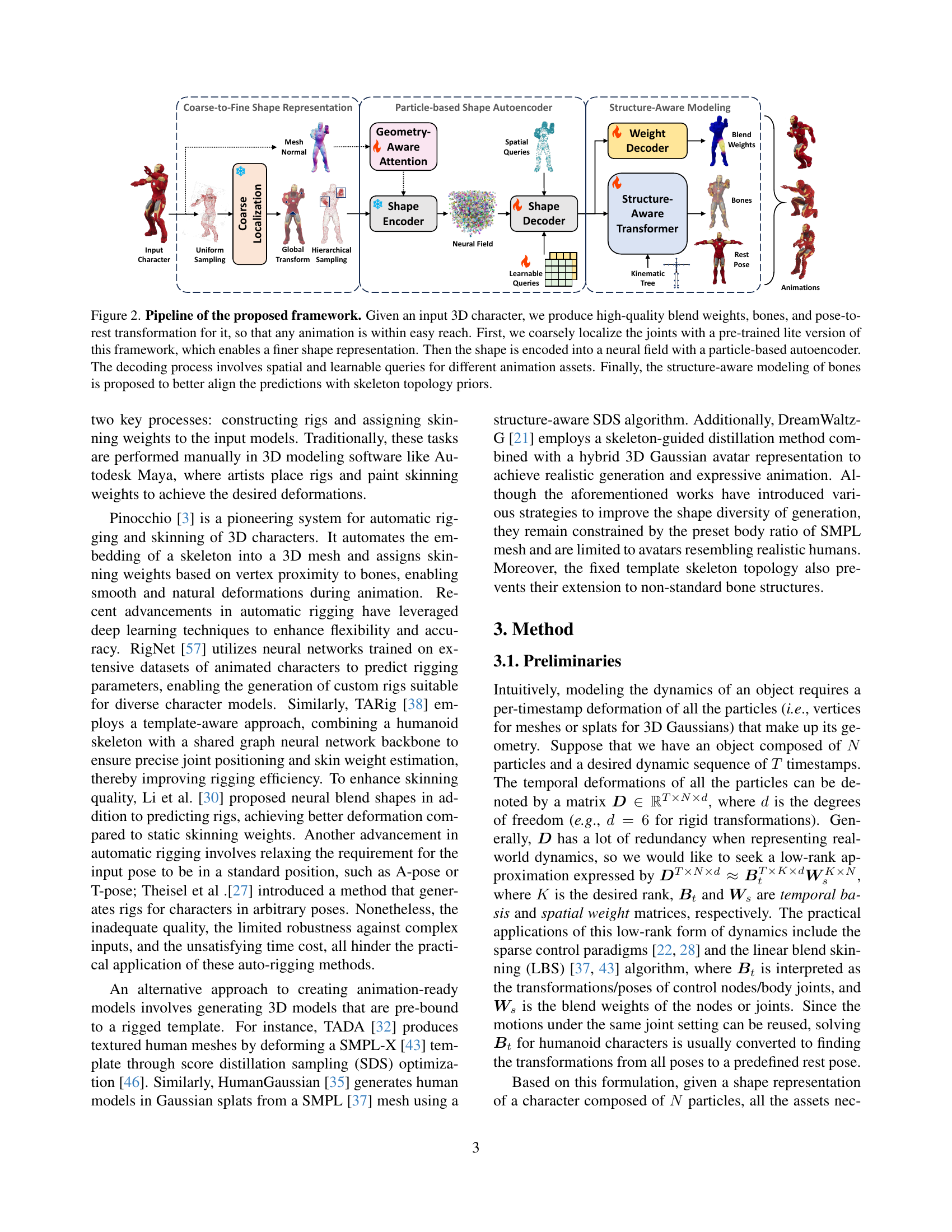

🔼 This figure illustrates the pipeline of the Make-It-Animatable framework, which efficiently generates animation-ready 3D characters from various input formats. The process begins with coarse joint localization using a pre-trained model, refining the shape representation. A particle-based autoencoder then encodes the shape into a neural field. Spatial and learnable queries decode this field to generate blend weights and bone structures. Finally, a structure-aware model refines bone predictions to better match skeletal topology, resulting in a fully animatable 3D character.

read the caption

Figure 2: Pipeline of the proposed framework. Given an input 3D character, we produce high-quality blend weights, bones, and pose-to-rest transformation for it, so that any animation is within easy reach. First, we coarsely localize the joints with a pre-trained lite version of this framework, which enables a finer shape representation. Then the shape is encoded into a neural field with a particle-based autoencoder. The decoding process involves spatial and learnable queries for different animation assets. Finally, the structure-aware modeling of bones is proposed to better align the predictions with skeleton topology priors.

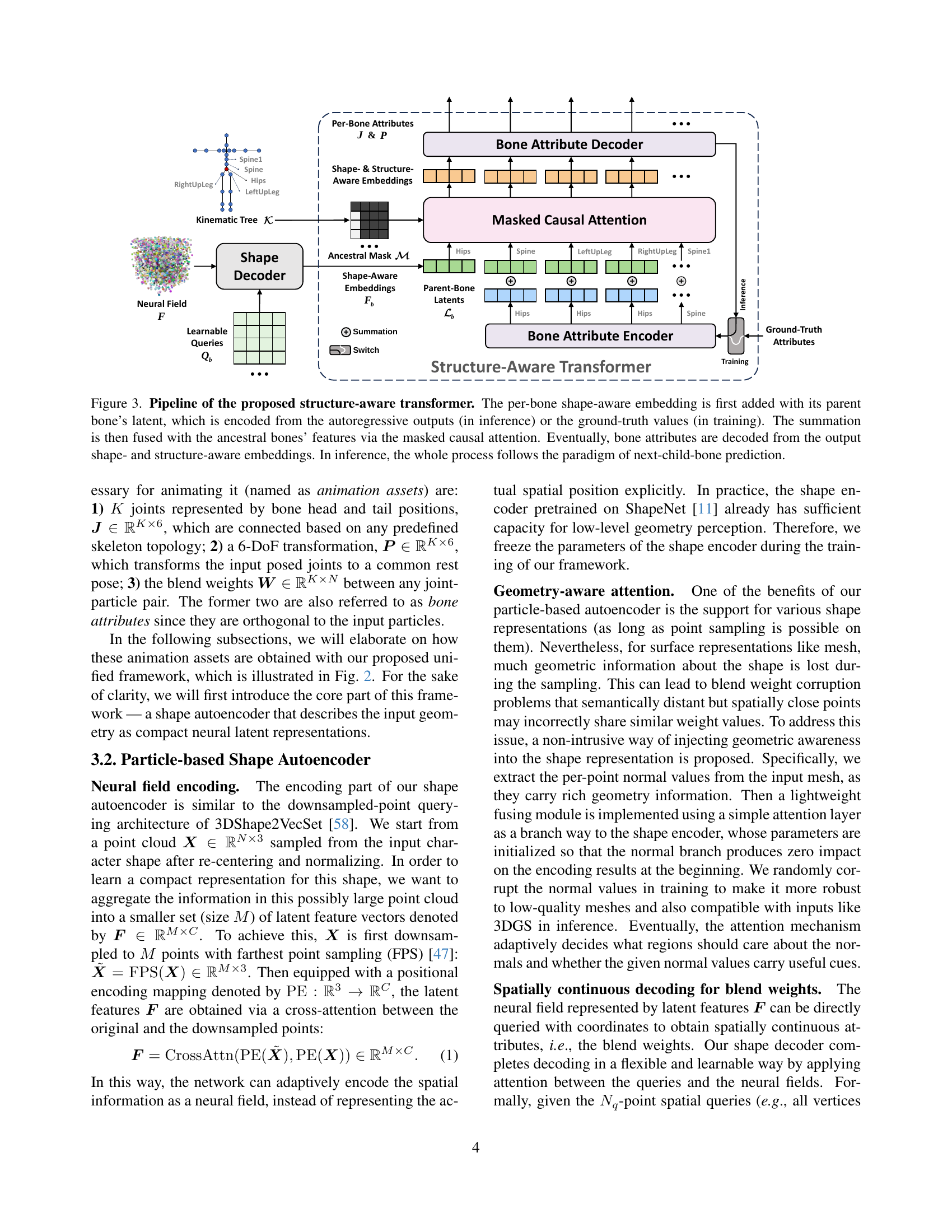

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the structure-aware transformer, a key component of the Make-It-Animatable framework. The transformer processes per-bone shape embeddings, combining them with latent information from parent bones (using autoregressive outputs during inference or ground truth values during training). This combined information, along with features from ancestral bones, is refined through masked causal attention. Finally, the transformer decodes the enriched shape and structure embeddings to generate bone attributes (joint positions and pose transformations). The inference process is sequential, predicting the attributes of child bones based on the already-predicted attributes of their parent bones.

read the caption

Figure 3: Pipeline of the proposed structure-aware transformer. The per-bone shape-aware embedding is first added with its parent bone’s latent, which is encoded from the autoregressive outputs (in inference) or the ground-truth values (in training). The summation is then fused with the ancestral bones’ features via the masked causal attention. Eventually, bone attributes are decoded from the output shape- and structure-aware embeddings. In inference, the whole process follows the paradigm of next-child-bone prediction.

🔼 This figure compares the results of the proposed method with two existing methods (Meshy and Tripo) for generating and rigging 3D character models from a reference image. The comparison focuses on the quality of blend weights (visualized for the left shoulder and right leg joints), the ability to handle arbitrary poses (a ‘running’ animation sequence was applied to all models for consistent comparison), and the ability to export rest-pose models (Meshy and Tripo lack this functionality). The figure includes the results from the proposed method, showing both the ‘running’ sequence results and also the model in a T-pose (rest pose) for better visualization of the generated model.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison with Meshy [meshy] and Tripo [tripo]. We feed them the same image as reference and compare the performance based on their generated 3D models respectively. The blend weights of two joints, i.e., Left Shoulder and Right Leg, are visualized. Given that these baselines can only apply preset motions and their rest-pose models cannot be exported, we apply a similar “running” sequence to all the methods for fair comparison. The T-pose models predicted by our method are also included as the front-view animating results.

🔼 This figure compares the results of the proposed method with RigNet, a data-driven automatic rigging method. It visualizes the blend weights of selected joints for several characters. By manually deforming these characters, the impact of rigging quality (accuracy of bone placement and assignment of weights) on the resulting skinning (deformation of the mesh) is assessed. The comparison helps demonstrate the superior quality and accuracy of the proposed method’s rigging compared to RigNet.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparison with RigNet [xu2020rignet]. We visualize the blend weights of selected joints and manually deform them to assess the impact of rigging quality on skinning results.

🔼 Figure 6 compares the proposed method with two template-based baselines: TADA, which generates mesh-based human models, and HumanGaussian, which uses Gaussian splats. It highlights that while both baselines use SMPL templates (without bone tails) and interpolate weights from these templates, the proposed method achieves comparable or superior results without relying on a pre-defined template. The figure shows examples of 3D characters, their skeletons, blend weights, and animation results from each method to visually demonstrate the quality difference. Zooming in is recommended to appreciate the detail.

read the caption

Figure 6: Comparison with TADA [liao2024tada] and HumanGaussian [liu2024humangaussian] (HG). We use the generated meshes from TADA and 3D Gaussians from HG for comparison. Note that the skeletons of these two baselines are identical to the shape-specific SMPL [loper2015smpl] templates (without bone tail), with their weights interpolated from the template meshes. Zoom in to better view the details.

🔼 Figure 7 showcases various examples illustrating the effectiveness of the proposed method in handling diverse 3D character models. These examples highlight the method’s ability to produce high-quality rigging and skinning results across different body shapes, poses, and skeletal structures. Specific examples include fine-grained finger control, handling of unconventional shapes, management of complex poses, efficient processing of high-polygon models, successful handling of asymmetric shapes, adaptation to models missing bones, and inclusion of extra bones such as ears and tails. Detailed analysis of each example is available in the supplementary material.

read the caption

Figure 7: Results of more cases to demonstrate the advantage of our method. The detailed explanations can be found in the supplementary material.

🔼 Figure 8 presents an ablation study to demonstrate the impact of different modules and design choices within the proposed framework. By visualizing the predicted bones, blend weights, and pose transformations for several variations, the study highlights how each component contributes to the overall accuracy and effectiveness of the animation-ready 3D character generation.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visualizations of some ablative experiments. We show the effectiveness of the proposed modules and design choices by visualizing the predicted bones, blend weights, and pose transformations.

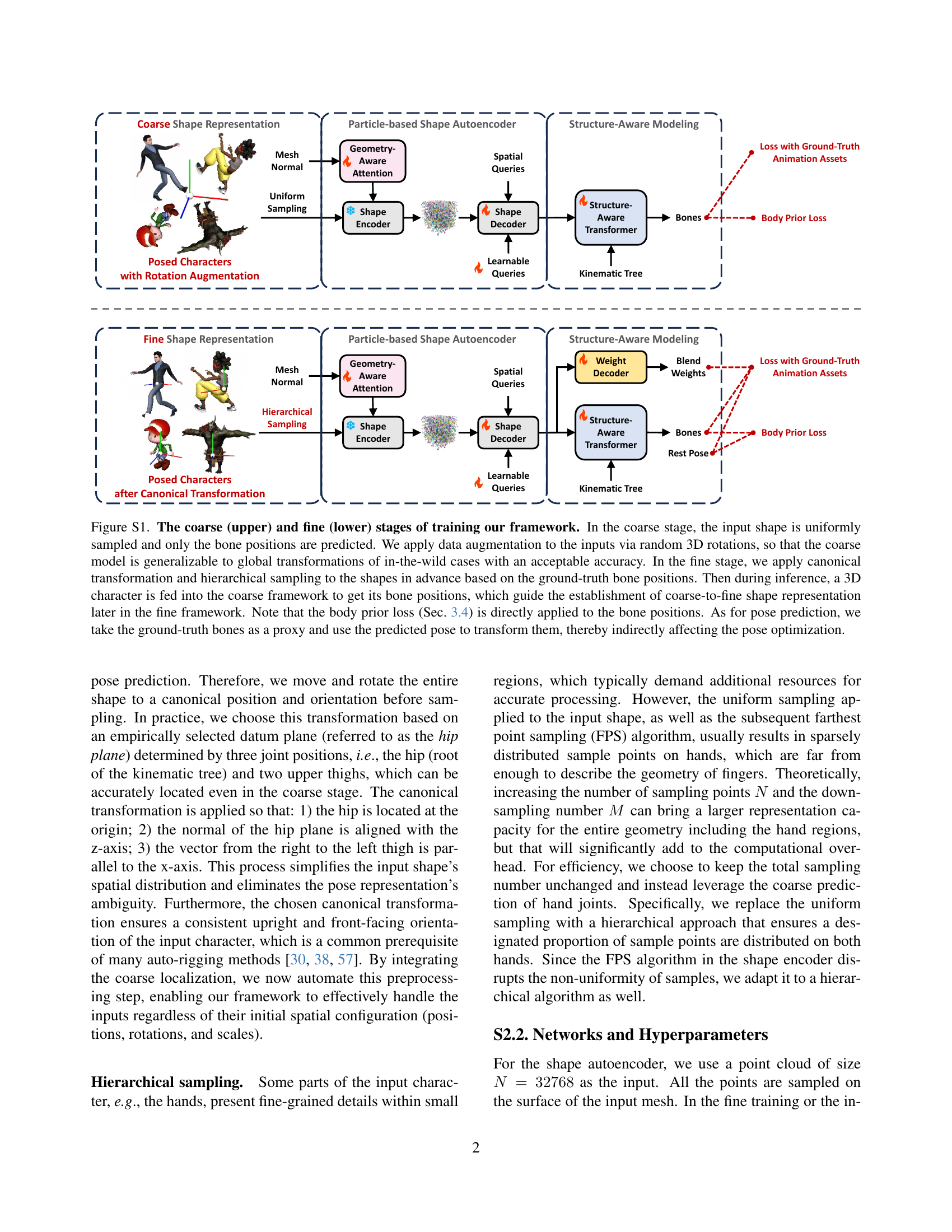

🔼 This figure illustrates the two-stage training process of the proposed framework. The upper part shows the coarse stage, where the input 3D shape is uniformly sampled, and only bone positions are predicted using data augmentation (random 3D rotations). This aims to make the coarse model robust to various global transformations. The lower part illustrates the fine stage. Here, canonical transformation and hierarchical sampling are applied to refine the shape representation based on the ground-truth bone positions obtained in the coarse stage. During inference, a 3D character is first processed by the coarse framework to predict bone positions; these positions then guide the creation of the refined shape representation in the fine framework. The body prior loss is directly applied to bone positions in both stages, and the ground-truth bones are used as a proxy for pose prediction to indirectly optimize the pose.

read the caption

Figure S1: The coarse (upper) and fine (lower) stages of training our framework. In the coarse stage, the input shape is uniformly sampled and only the bone positions are predicted. We apply data augmentation to the inputs via random 3D rotations, so that the coarse model is generalizable to global transformations of in-the-wild cases with an acceptable accuracy. In the fine stage, we apply canonical transformation and hierarchical sampling to the shapes in advance based on the ground-truth bone positions. Then during inference, a 3D character is fed into the coarse framework to get its bone positions, which guide the establishment of coarse-to-fine shape representation later in the fine framework. Note that the body prior loss (Sec. 3.4) is directly applied to the bone positions. As for pose prediction, we take the ground-truth bones as a proxy and use the predicted pose to transform them, thereby indirectly affecting the pose optimization.

🔼 This figure displays a subset of the 3D character models used to train the Make-It-Animatable framework. The Mixamo dataset contains a variety of bipedal humanoid characters, demonstrating diverse body shapes and styles, ranging from realistic human figures to stylized cartoon and fantasy characters. Each model in the dataset has been pre-processed to ensure compatibility with the animation sequences used for training. This preprocessing step makes each character readily animatable.

read the caption

Figure S2: Some samples from the collected Mixamo [mixamo] dataset. The dataset contains bipedal humanoids with different shapes, ranging from realistic humans to cartoon or fantasy creatures. Each character is preprocessed to be animatable by any of the motion sequences. The proposed framework is trained on this dataset.

🔼 Figure S3 shows examples of anime-style 3D characters created using Vroid Studio and modified to be compatible with the Mixamo standard skeleton. These models include additional accessories such as ears and tails, allowing for the training and evaluation of the proposed method’s ability to handle characters with non-standard bone structures (extra bones). The modifications to fit the Mixamo skeleton demonstrate a practical application of the framework’s adaptability and robustness.

read the caption

Figure S3: Some samples of the anime characters with additional accessories for the extra-bone fine-tuning. These characters are all manually created using Vroid Studio [vroid] and then preprocessed to be compatible with the standard skeleton definition of Mixamo [mixamo].

🔼 This figure compares the proposed method with two other generative 3D modeling methods, Meshy and Tripo. All three methods were given the same reference image as input. The resulting 3D models from each method are shown, with a focus on the blend weights assigned to the left shoulder and right leg joints. This helps illustrate the differences in the quality of the rigging and skinning generated by each method. The figure also includes a visualization of the T-pose (a standard pose used for animation) generated by the proposed method for a front-view comparison.

read the caption

Figure S4: Additional Comparison with generative 3D methods, i.e., Meshy [meshy] and Tripo [tripo]. We feed them the same image as reference and compare the performance based on their generated 3D models respectively. The blend weights of two joints, i.e., Left Shoulder and Right Leg, are visualized. The T-pose models predicted by our method are included as the front-view animating results. Zoom in to better view the details.

🔼 Figure S5 presents a comparison of the proposed method with two template-based avatar generation methods: TADA and HumanGaussian. The comparison uses 3D models generated by TADA (meshes) and HumanGaussian (3D Gaussian splats). Importantly, both TADA and HumanGaussian rely on the SMPL template for their skeletons (excluding the bone tails), and their weights are interpolated from the template meshes. The figure visually compares the results of the three methods, highlighting differences in the generated skeletons, blend weights, and animation results. Zooming in is recommended to see the details clearly.

read the caption

Figure S5: Additional comparison with template-based avatar generation methods, i.e., TADA [liao2024tada] and HumanGaussian [liu2024humangaussian] (HG). We use the generated meshes from TADA and 3D Gaussians from HG for comparison. Note that the skeletons of these two baselines are identical to the shape-specific SMPL [loper2015smpl] templates (without bone tail), with their weights interpolated from the template meshes. Zoom in to better view the details.

🔼 Figure S6 presents a comparison of the proposed method’s rigging and skinning capabilities against three existing auto-rigging techniques: RigNet, TARig, and Neural Blend Shapes. The figure visually demonstrates the quality of blend weights generated by each method for selected joints. To assess the impact of rigging quality on the resulting skinning, the authors manually deformed the meshes. Importantly, Neural Blend Shapes only accepts T-pose (a standardized pose) input. To incorporate non-T-pose examples fairly, T-pose versions of the non-T-pose models were created using the authors’ pose-to-rest transformations prior to input into Neural Blend Shapes for a consistent evaluation.

read the caption

Figure S6: Additional comparison with auto-rigging methods, i.e., RigNet [xu2020rignet], TARig [ma2023tarig], and Neural Blend Shapes [li2021learning] (Neural BS). We visualize the blend weights of selected joints and manually deform them to assess the impact of rigging quality on skinning results. *: Neural Blend Shapes only support T-pose inputs, so for the non-rest cases (lower two), we feed it the T-pose meshes transformed by our pose-to-rest predictions.

🔼 This figure compares the results of using the proposed method against two commercial auto-rigging software packages, Mixamo and Anything World. The comparison highlights the limitations of Mixamo and Anything World, which perform optimally only with simple input poses like the T-pose or A-pose. When presented with more complex poses, these software packages frequently produce errors. The figure demonstrates the superior performance and robustness of the proposed method in handling diverse and complex poses.

read the caption

Figure S7: Comparison with commercial auto-rigging software, i.e., Mixamo [mixamo] and Anything World [anythingworld]. Note that these two tools can only deal with simple input poses (T- or A-pose is recommended) and often raise errors when faced with complex ones.

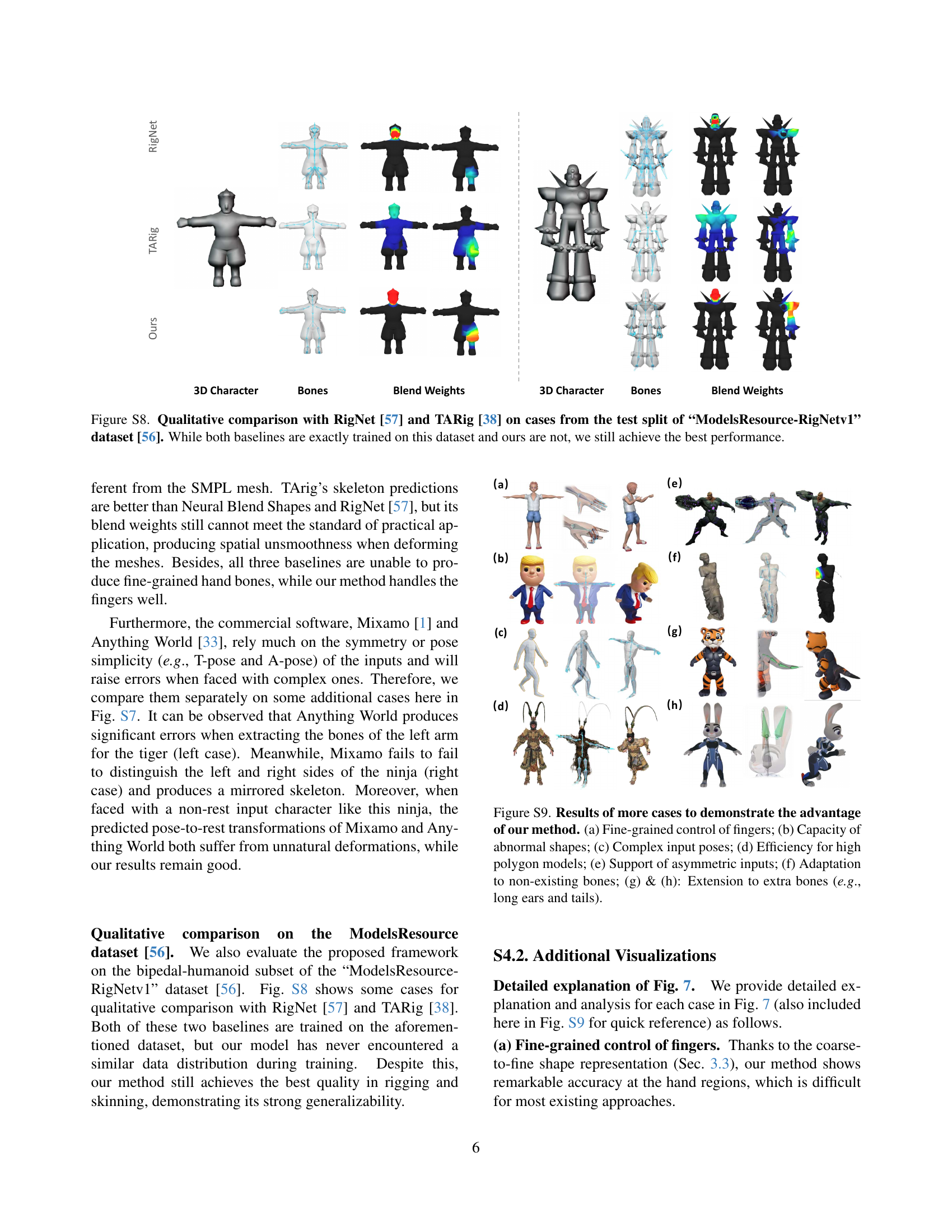

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed method against two state-of-the-art auto-rigging methods, RigNet and TARig, on a subset of the ModelsResource-RigNetv1 dataset. The key takeaway is that despite RigNet and TARig being trained specifically on this dataset, while the proposed method was not, it still achieves superior performance in terms of rigging and skinning quality.

read the caption

Figure S8: Qualitative comparison with RigNet [xu2020rignet] and TARig [ma2023tarig] on cases from the test split of “ModelsResource-RigNetv1” dataset [xu2019predicting]. While both baselines are exactly trained on this dataset and ours are not, we still achieve the best performance.

🔼 This figure showcases additional examples to highlight the strengths of the proposed method. Panel (a) demonstrates the fine-grained control achieved over finger articulation. Panel (b) shows the method’s ability to handle characters with unusual proportions or shapes (abnormal shapes). Panel (c) illustrates successful rigging and skinning of characters in complex or challenging poses. Panel (d) exhibits the efficiency of the method even when processing high-polygon models. Panel (e) presents successful results for characters with asymmetrical features. Panel (f) shows how the method adapts when dealing with missing body parts (non-existing bones). Finally, panels (g) and (h) demonstrate the extensibility of the method to incorporate extra bones, such as long ears or tails, illustrating the capacity for creating diverse and detailed character models.

read the caption

Figure S9: Results of more cases to demonstrate the advantage of our method. (a) Fine-grained control of fingers; (b) Capacity of abnormal shapes; (c) Complex input poses; (d) Efficiency for high polygon models; (e) Support of asymmetric inputs; (f) Adaptation to non-existing bones; (g) & (h): Extension to extra bones (e.g., long ears and tails).

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness and lack of side effects of the geometry-aware attention module, a key part of the proposed framework. The module incorporates normal information to improve the quality of shape representations and blend weight predictions. The results show that using attention-based injection of normal information leads to improved results without any negative consequences.

read the caption

Figure S10: Qualitative analysis of our geometry-aware attention module and its injecting method. The proposed attention-based injection can benefit from normal information without any side effects.

🔼 This figure visualizes the attention weights learned by the geometry-aware attention module within the shape autoencoder. The visualization shows the attention scores for each sampled point, with brighter colors (yellow) representing higher attention to surface normals. Areas where high attention scores are clustered are highlighted with green bounding boxes. The visualization demonstrates that the model learns to prioritize surface normal information over coordinate information in ambiguous regions such as the inner thighs where coordinate-based information is less discriminative.

read the caption

Figure S11: Visualization of the attention score of our geometry-aware attention module. These per-sampled-point values are extracted from the first attention head (out of 8 heads in total). The brighter color (yellower) indicates more attention to normals rather than coordinates. We also use green bounding boxes to label some clusters where high-attention-score points are densely distributed. It can be observed that the module adaptively learns to rely more on normals in regions like the inner thigh since coordinates become less discriminative there.

More on tables

| IoU ↑ | Precision ↑ | Recall ↑ | CD-J2J ↓ | CD-J2B ↓ | CD-B2B ↓ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RigNet [xu2020rignet] | 53.50% | 47.27% | 89.30% | 6.63% | 4.97% | 2.88% |

| Ours | 82.50% | 81.07% | 90.31% | 4.49% | 3.32% | 1.58% |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the skeleton prediction results obtained from the proposed method and the RigNet method. The comparison focuses on a subset of the test dataset containing bipedal humanoid characters from the paper [xu2019predicting]. The metrics used for comparison include Intersection over Union (IoU), precision, recall, and Chamfer distances (CD-J2J, CD-J2B, CD-B2B). These metrics evaluate the accuracy and quality of the skeleton predictions, providing a detailed assessment of the performance of both methods on this specific type of character.

read the caption

Table 2: Quantitative comparison of skeleton prediction on the bipedal humanoid subset of the test dataset [xu2019predicting].

| Method | Weights Error ↓ | Joints Error ↓ | Poses Error ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| w/o canonical transformation | 6.27% | 9.80% | 41.8% |

| w/o hierarchical sampling | 5.55% | 2.42% | 18.0% |

| w/o geometry-aware attention | 5.16% | 2.20% | 14.2% |

| w/o structure-aware transformer | - | 2.13% | 14.9% |

| w/o body prior loss | - | 2.13% | 14.0% |

| w/o global pose representation | - | - | 35.3% |

| Ours | 4.70% | 2.11% | 13.6% |

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of various components and strategies within the proposed framework on the accuracy of generated animation assets. The study uses the test split of the Mixamo dataset. The results are presented as percentage errors for blend weights, bone positions, and pose-to-rest transformations.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation studies on the test split of the Mixamo dataset. We report the percentage error of animation assets.

Full paper#