↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current text-to-video models often struggle with precise camera control, leading to lower video quality. Many existing approaches attempt to integrate 3D camera control into pre-trained models; however, this often leads to imprecise control and compromises in video quality. The lack of high-quality datasets with diverse dynamic scenes and static cameras further exacerbates the problem.

The researchers developed AC3D, a novel architecture that addresses these issues. Their approach involves analyzing the spectral properties of camera motion to optimize training and testing schedules, probing the model’s internal representations to strategically inject camera information, and curating a new dataset of dynamic videos with stationary cameras to improve motion realism. Experimental results show that AC3D significantly outperforms existing methods in terms of both visual quality and camera control precision.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on text-to-video generation and 3D scene understanding. It provides a novel approach to precise 3D camera control in video diffusion models, addressing a significant limitation in current methods. The findings offer valuable insights into the nature of camera motion in video data and suggest new avenues for improving model architecture and training strategies, potentially advancing the state-of-the-art in video synthesis and virtual world creation. Furthermore, the introduced dataset of dynamic scenes with stationary cameras tackles a significant data bias, benefitting the wider AI community researching in video understanding and synthesis.

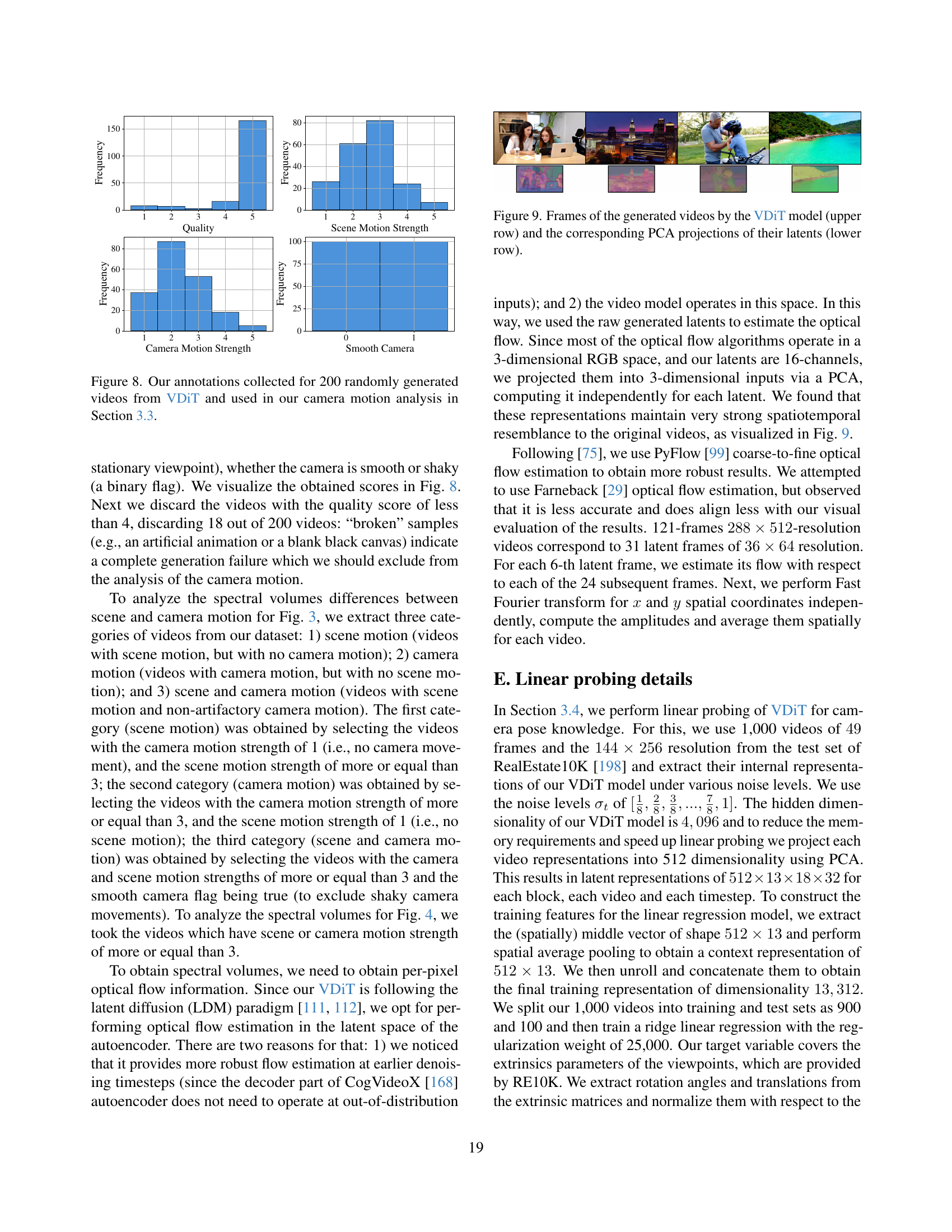

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure demonstrates the capability of the proposed method to precisely control camera movement during video generation using pre-trained video diffusion transformers. Two videos of the same scene are shown, each generated with a different camera trajectory. The left video shows a camera rotating to the right, while the right video shows a camera zooming in, moving upward, and then zooming out. The inset images offer a visual representation of the camera’s trajectory for each video.

read the caption

Figure 1: Camera-controlled video generation. Our method enables precise camera controllability in pre-trained video diffusion transformers, allowing joint conditioning of text and camera sequences. We synthesize the same scene with two different camera trajectories as input. The inset images visualize the cameras for the videos in the corresponding columns. The left camera sequence consists of a rotation to the right, while the right camera visualizes a zoom-in, up, and zoom-out trajectory.

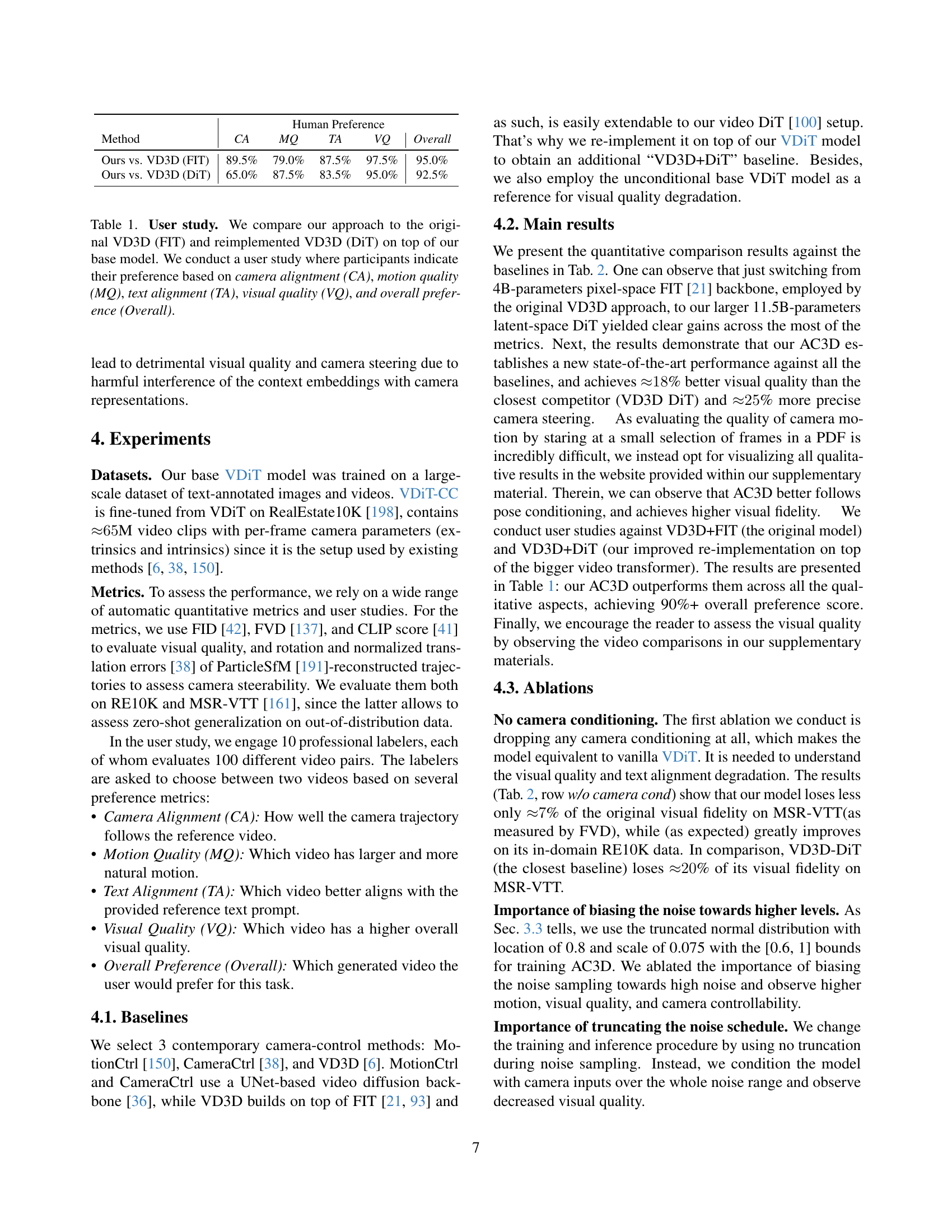

🔼 This user study compares the proposed AC3D model against the original VD3D model (trained using a UNet-based architecture) and a re-implementation of VD3D on top of the AC3D’s base model (a video diffusion transformer). Human participants assessed the generated videos based on five criteria: Camera Alignment (how well the generated camera trajectory matched a reference video), Motion Quality (naturalness and fluidity of movement), Text Alignment (how well the video content reflected the text prompt), Visual Quality (overall image and video quality), and Overall Preference (an overall preference rating). The results show the performance differences across various metrics, highlighting AC3D’s strengths.

read the caption

Table 1: User study. We compare our approach to the original VD3D (FIT) and reimplemented VD3D (DiT) on top of our base model. We conduct a user study where participants indicate their preference based on camera aligntment (CA), motion quality (MQ), text alignment (TA), visual quality (VQ), and overall preference (Overall).

In-depth insights#

Camera Motion Spectra#

Analyzing camera motion spectra in videos offers valuable insights into video generation models. By examining the frequency distribution of motion energy, researchers can better understand how cameras are perceived and how their movements influence the overall visual experience. Low-frequency components generally correspond to smooth camera pans or zooms, which appear natural and less jarring, while high-frequency motions could represent shaky or abrupt movements that may negatively impact video quality. Understanding this relationship enables researchers to improve the precision and smoothness of camera control in video synthesis. It can lead to more realistic and visually appealing results by leveraging the findings to adjust pose conditioning schedules during training and inference, ensuring that generated videos exhibit natural and intuitive camera movements. The insights gained from camera motion spectral analysis can enhance the control over generated camera trajectories and improve the overall quality of synthetic videos. This would prove invaluable for various applications, including cinematic video generation, virtual reality experiences, and autonomous systems development, where precise and predictable camera motion are paramount.

VDiT’s Camera Sense#

The research paper investigates the inherent understanding of 3D camera control within a pre-trained video diffusion transformer, termed VDiT. The core of the “VDiT’s Camera Sense” exploration lies in determining whether the model implicitly learns camera parameters and how this knowledge is encoded in its architecture. The analysis reveals that VDiT doesn’t explicitly model cameras, but rather implicitly learns camera pose estimation, indicating that camera information is encoded within the model’s internal representations. This implicit representation isn’t uniformly distributed throughout the network; instead, its presence is more pronounced in certain layers of the architecture, peaking in the middle layers and gradually fading in earlier and later layers. This observation suggests a hierarchical processing of visual information, where camera pose is initially estimated in the earlier layers and then used to refine visual representations in subsequent layers. This finding has significant implications for effective camera control, particularly emphasizing the importance of strategic injection of camera conditioning. By understanding the model’s implicit camera understanding, researchers can devise methods that leverage VDiT’s existing capabilities, enhancing both training efficiency and overall video generation quality.

Training Data Imbalance#

Training data imbalance is a critical issue in machine learning, particularly when dealing with datasets containing a disproportionate number of samples belonging to different classes. This imbalance can lead to biased models that perform poorly on under-represented classes. In the context of video generation with 3D camera control, this imbalance manifests as datasets containing a vast majority of static scenes with fixed cameras and fewer dynamic scenarios involving complex camera movements. This imbalance is problematic as it creates models that are excessively good at generating static content but struggle with dynamic situations. To mitigate this problem, the paper suggests creating a curated dataset containing dynamic videos captured from static cameras. This simple yet effective approach ensures diverse training data. By doing so, models learn to separate camera motion from scene motion, improving the generation quality of dynamic sequences. This strategy contrasts with other methods, which often use large-scale datasets that inherently favor static videos and result in an overall preference for generating scenes without camera movement, highlighting the significant impact of carefully balanced data on the ability to precisely control camera motions during video generation.

AC3D Architecture#

The hypothetical “AC3D Architecture” section would likely detail the model’s design, emphasizing its improvements over existing camera control methods in video diffusion transformers. It would likely begin by describing the base VDiT (Video Diffusion Transformer) model, highlighting its scale and pre-training. A key aspect would be the integration of a camera control module, potentially using a ControlNet-like approach or a novel design, clarifying how camera pose information is injected and processed within the transformer architecture. The architecture’s innovation would likely focus on efficient camera conditioning, possibly by limiting conditioning to specific layers identified as most receptive to camera information or employing lightweight processing blocks for camera data. Data augmentation strategies employed to mitigate biases present in standard training datasets would also be discussed, particularly highlighting techniques to improve the model’s understanding of dynamic scenes and disambiguate camera versus scene motion. Finally, a detailed explanation of the training process and hyperparameters would be provided, emphasizing any optimizations or techniques specific to the AC3D architecture.

Future Work: OOD#

The heading “Future Work: OOD” suggests a significant direction for future research. The authors acknowledge that their model, while advanced, struggles with out-of-distribution (OOD) camera trajectories, meaning cameras moving in ways unseen during training. This limitation highlights a crucial gap in current generative models’ ability to generalize beyond their training data distribution. Future work should address this by exploring larger and more diverse datasets of camera movements, incorporating techniques for domain adaptation or transfer learning, or developing new model architectures that inherently possess better generalization capabilities. Specifically, researching methods to improve the model’s understanding of 3D scene geometry and physics in relation to camera movement could be beneficial. Investigating techniques to learn more robust representations of camera motion, perhaps using disentangled representations or generative adversarial networks, could also improve OOD generalization. Another critical aspect is designing appropriate evaluation metrics tailored specifically for the assessment of OOD generalization in camera control tasks. Finally, considering alternative training strategies, such as self-supervised or reinforcement learning, could further enhance the model’s capacity to adapt to OOD scenarios. Successfully addressing OOD generalization is essential for making camera control in video generation models more robust and practical.

More visual insights#

More on figures

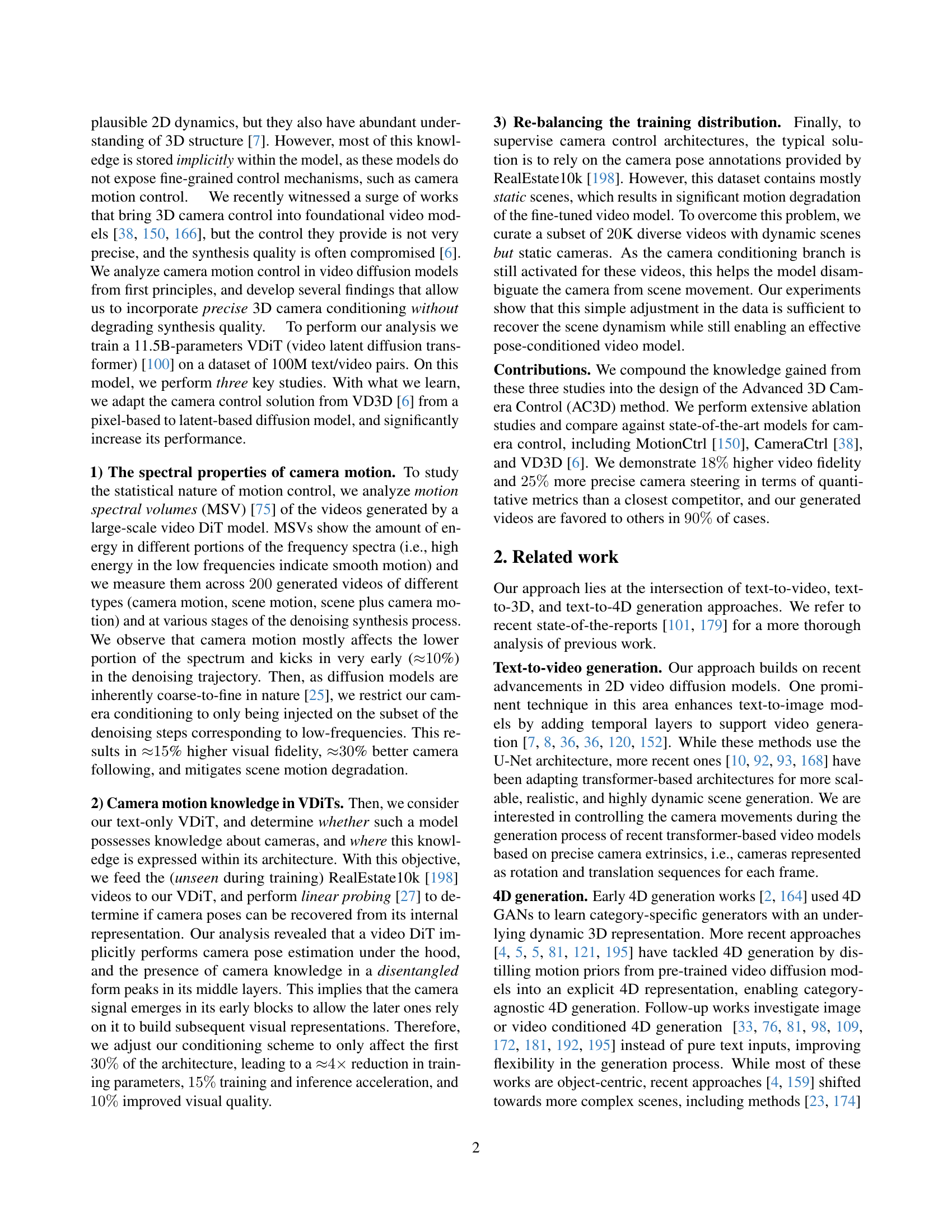

🔼 The figure illustrates the architecture of the VDiT-CC model, which incorporates camera control into a pre-trained video diffusion transformer (VDiT). The VDiT backbone, consisting of large 4,096-dimensional DiT-XL blocks, is responsible for video synthesis and remains frozen during training. A lightweight camera conditioning module, VDiT-CC, is built on top of the VDiT. VDiT-CC uses smaller, 128-dimensional DiT-XS blocks to process and inject camera information into the main VDiT network, thereby controlling camera pose without modifying the VDiT’s primary video generation capabilities. Fully-connected layers (FC) are utilized within these DiT-XS blocks. Details regarding this architecture and training process are further described in Section 3.2 of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 2: VDiT-CCmodel with ControlNet [187, 71] camera conditioning built on top of VDiT. Video synthesis is performed by large 4,096-dimensional DiT-XL blocks of the frozen VDiT backbone, while VDiT-CC only processes and injects the camera information through lightweight 128-dimensional DiT-XS blocks (FC stands for fully-connected layers); see Section 3.2 for details.

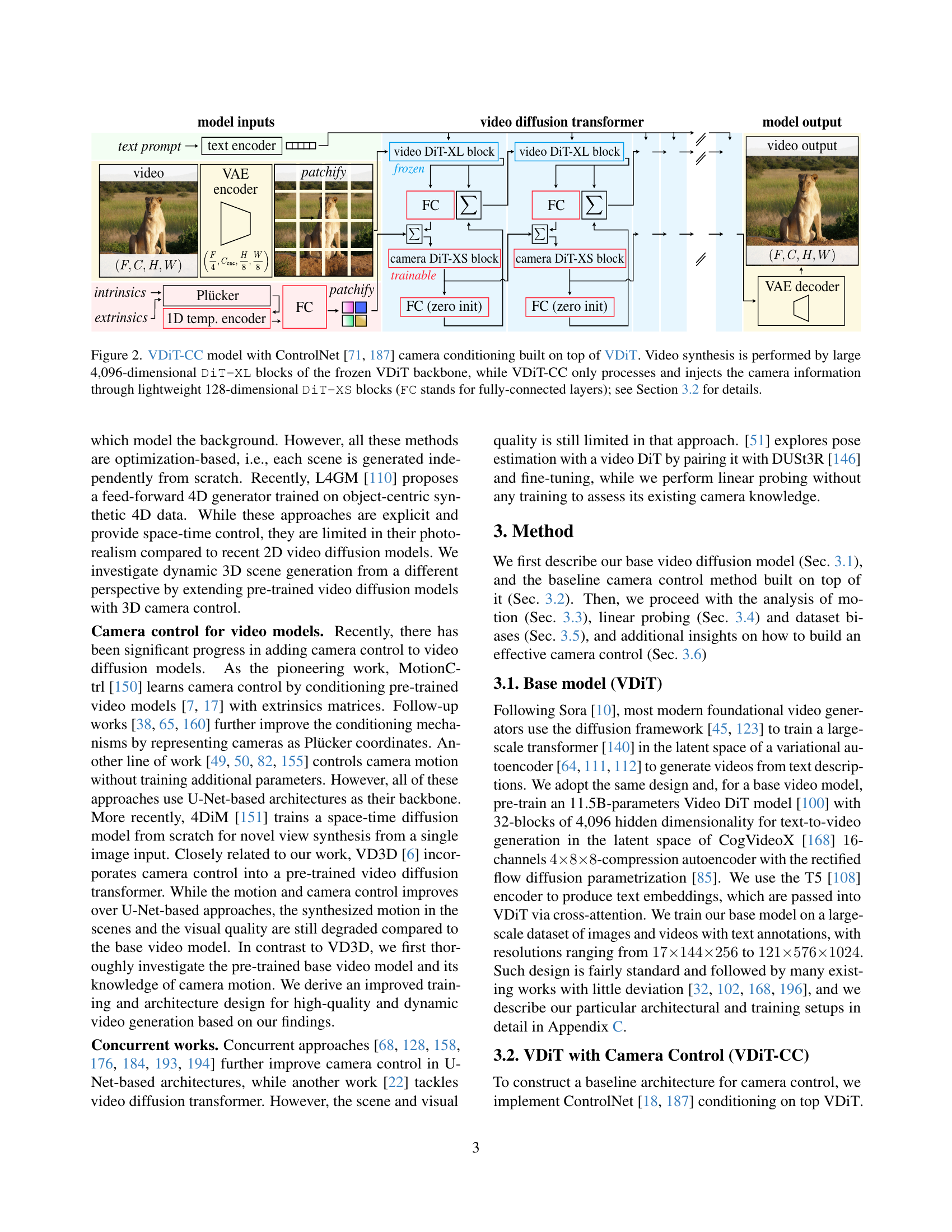

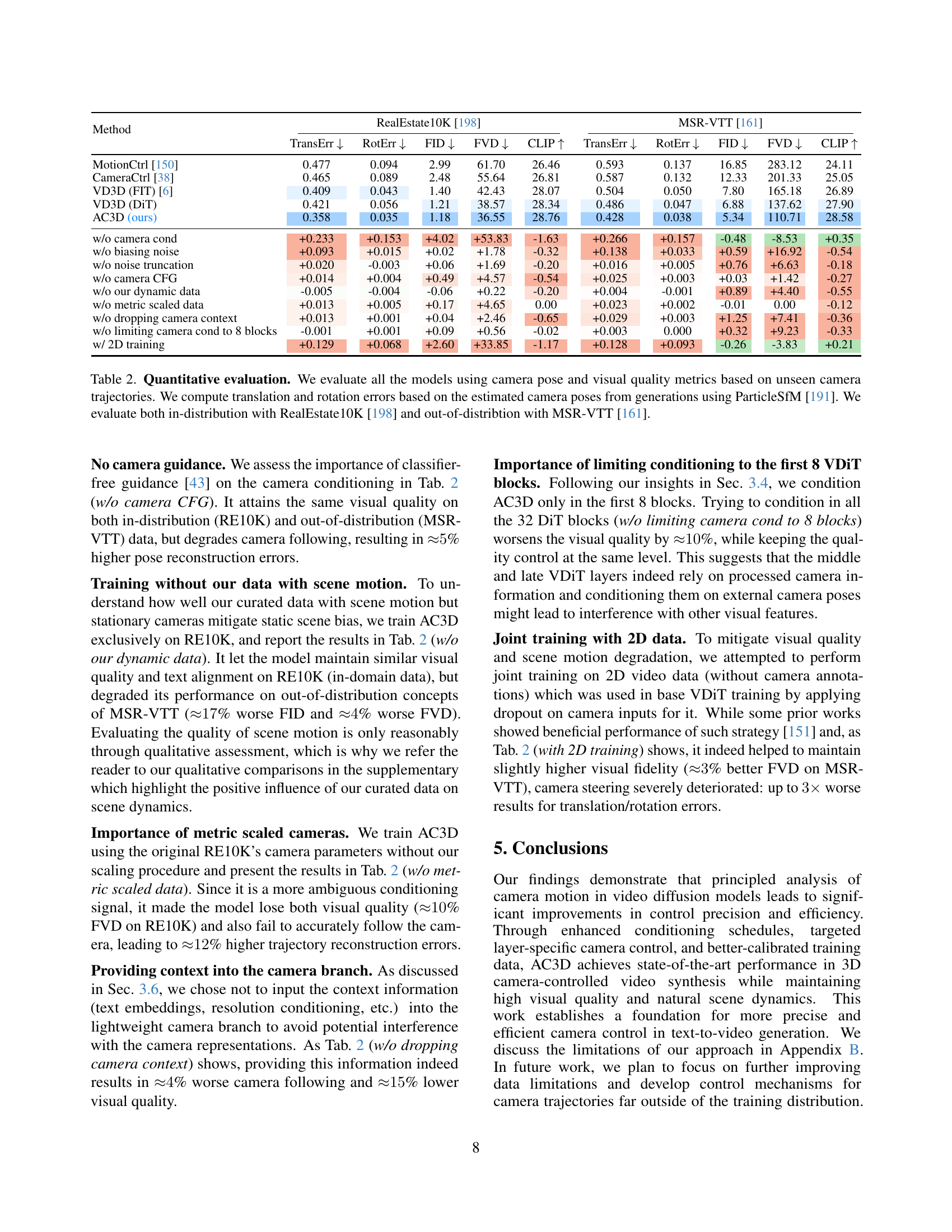

🔼 The figure visualizes the frequency spectrum of motion in videos generated by a video diffusion model. Three types of videos are compared: those with only scene motion, only camera motion, and both scene and camera motion. The results show that camera motion predominantly affects the low-frequency components of the motion spectrum, while scene motion affects both high and low frequencies. This finding suggests that camera movements in videos are characterized by smooth, low-frequency motion, which can inform the design of training and inference strategies for camera control in video generation models.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparing motion spectral volumes for scenes with different motion types. Videos with camera motion (purple) exhibit stronger overall motion than the videos with scene motion (orange), especially for the low-frequency range, suggesting that the motion induced by camera transitions is heavily biased towards low-frequency components.

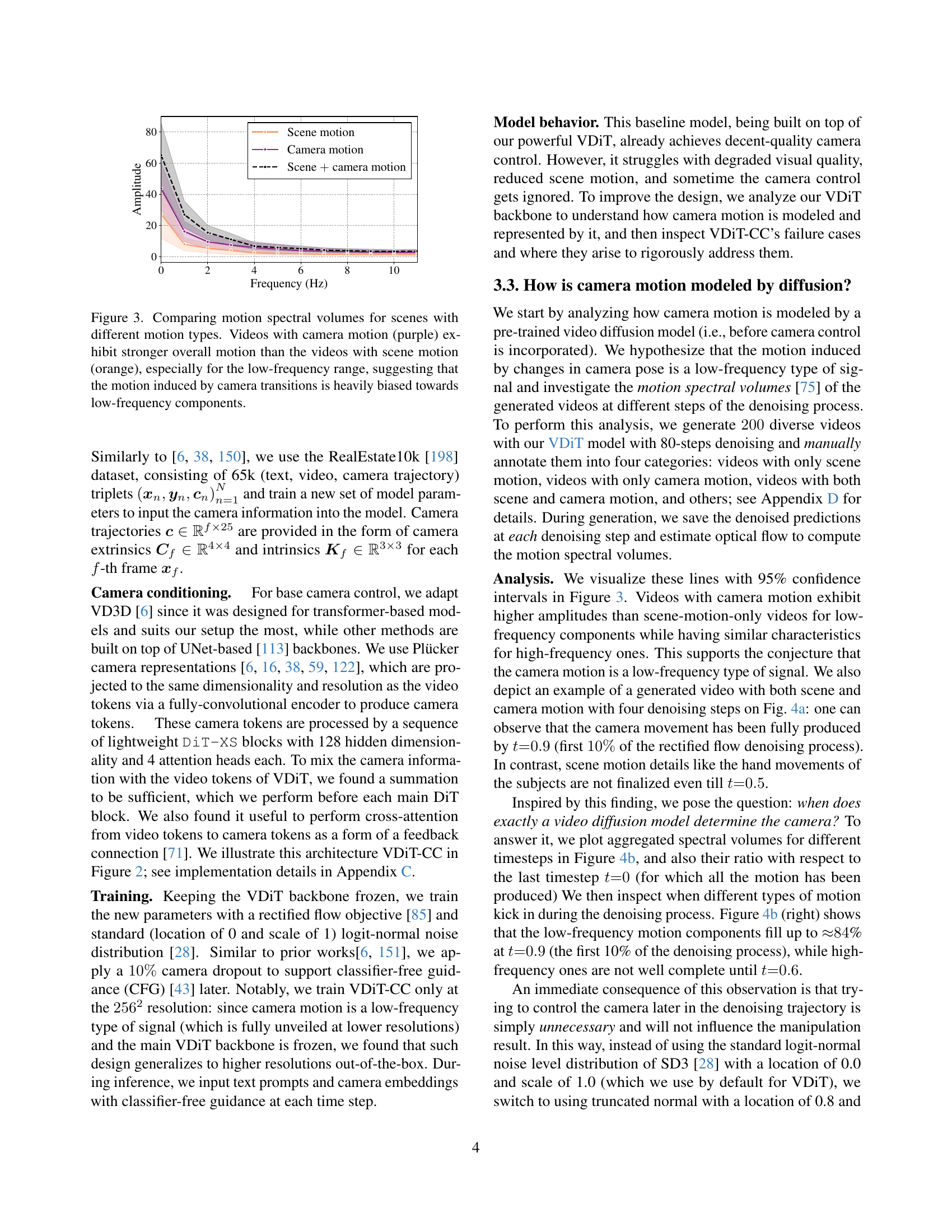

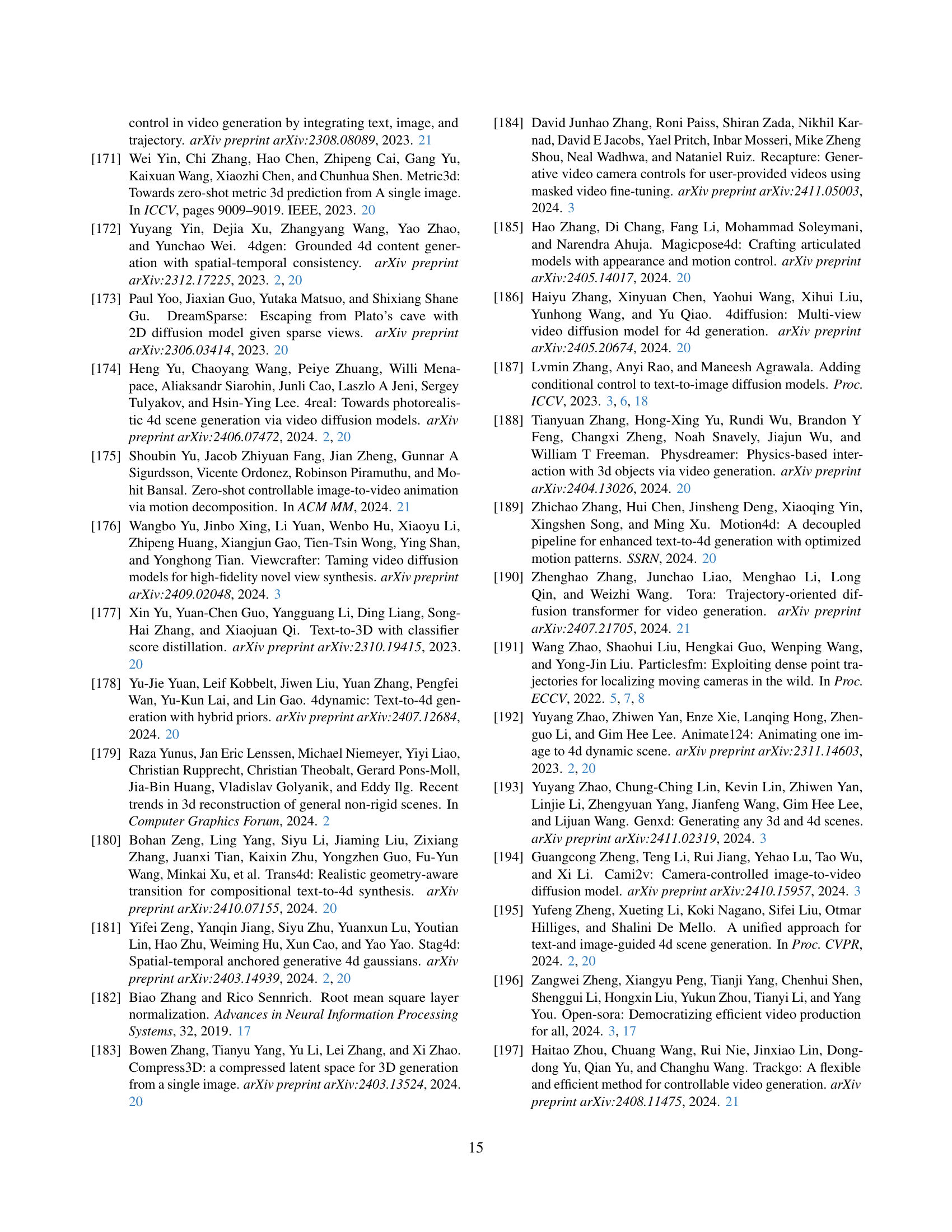

🔼 The figure visualizes a video generated by a diffusion model at different stages of the denoising process. Specifically, it showcases that the camera pose is determined very early in the process (at t=0.9, representing the first 10% of denoising), and remains consistent throughout the rest of the generation. This observation suggests that the model makes crucial camera-related decisions early on, highlighting the influence of low-frequency components in camera motion.

read the caption

(a) A generated video at different diffusion timesteps. The camera has already been decided by the model even at t=0.9𝑡0.9t=0.9italic_t = 0.9 (first 10% of the denoising process) and does not change after that.

🔼 This figure visualizes the spectral properties of camera motion during video generation using a video diffusion transformer (VDIT). The left panel shows motion spectral volumes (MSVs) for different diffusion timesteps, revealing the distribution of motion energy across frequencies. The right panel displays the ratio of MSVs at each timestep to the MSV at the final timestep (t=0), highlighting when different motion components appear during the generation process. This analysis helps determine the optimal timing for injecting camera information during video synthesis, ultimately improving generation quality and camera control accuracy.

read the caption

(b) Motion spectral volumes of VDiT’s generated videos for different diffusion timesteps (left) and their ratio w.r.t. the motion spectral volume at t=0𝑡0t=0italic_t = 0 (i.e., a fully denoised video).

🔼 This figure analyzes how camera motion is represented in a video diffusion model. Figure 4(a) shows a generated video at different diffusion timesteps, demonstrating that camera motion is largely determined very early in the process. Figure 4(b) provides a spectral analysis of motion, showing that camera motion primarily affects low frequencies and is mostly complete by t=0.96, whereas high-frequency details related to scene motion continue to develop later (till t=0.5). The authors conclude that controlling camera pose later in the diffusion process is counterproductive and harms both scene motion and overall image quality.

read the caption

Figure 4: How camera motion is modeled by diffusion? As visualized in Figure 4(a) and Figure 3, the motion induced by camera transitions is a low-frequency type of motion. We observe that a video DiT creates low-frequency motion very early in the denoising trajectory: Figure 4(b) (left) shows that even at t=0.96𝑡0.96t{=}0.96italic_t = 0.96 (first ≈4absent4{\approx}{4}≈ 4% of the steps), the low-frequency motion components have already been created, while high frequency ones do not fully unveil even till t=0.5𝑡0.5t{=}0.5italic_t = 0.5. We found that controlling the camera pose later in the denoising trajectory is not only unnecessary but detrimental to both scene motion and overall visual quality.

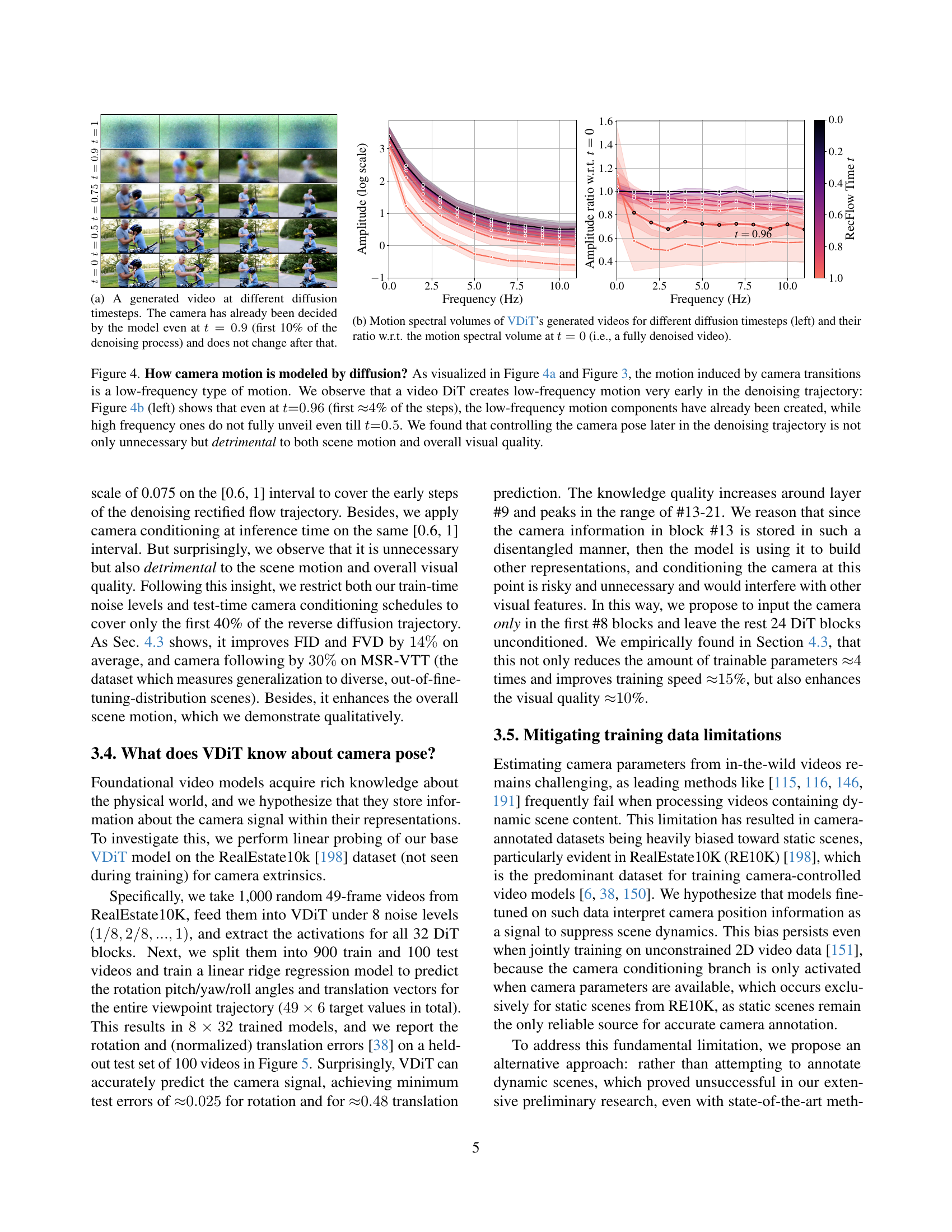

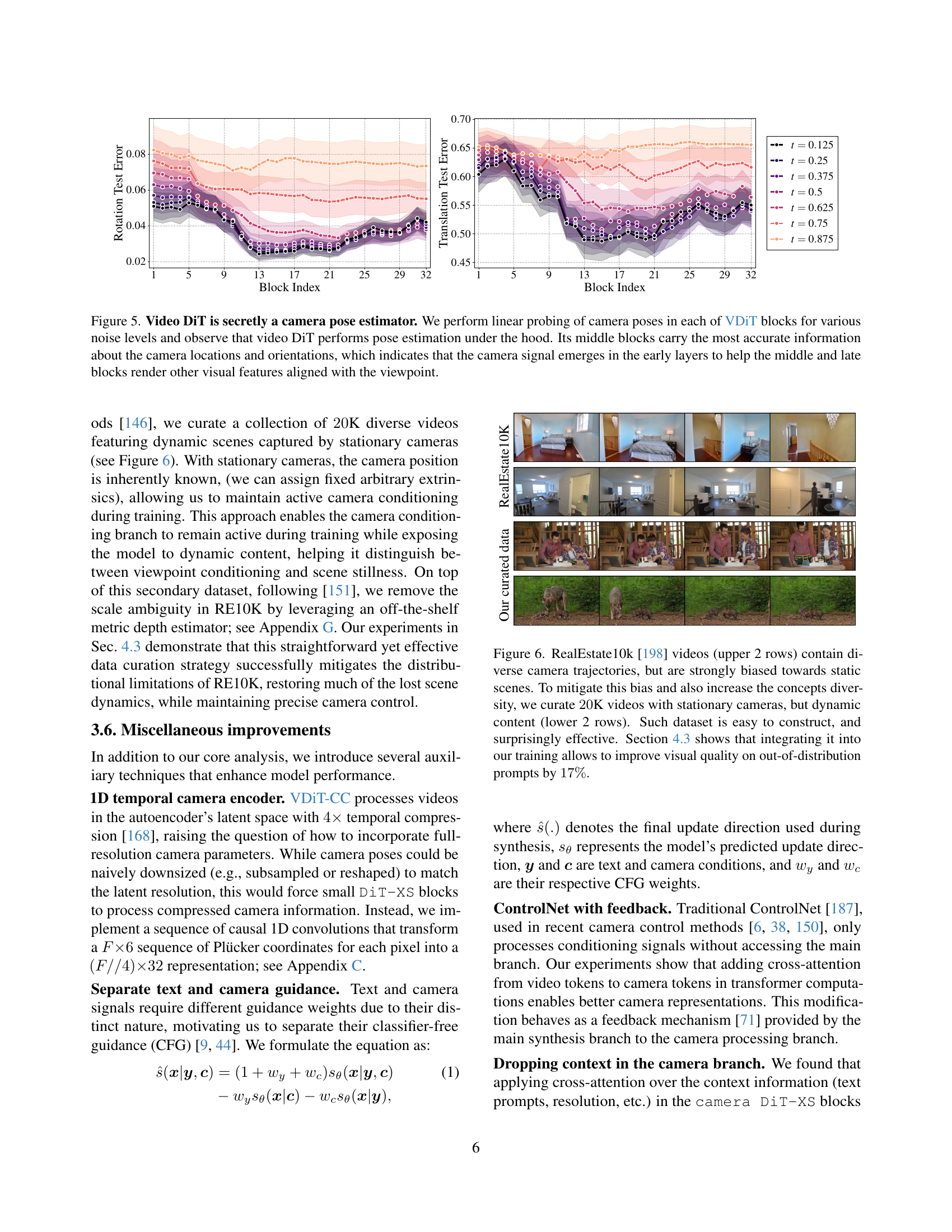

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of a linear probing experiment to determine whether a pre-trained Video Diffusion Transformer (VDiT) implicitly learns camera pose information. The experiment uses the RealEstate10K dataset and tests various noise levels in the VDiT’s internal representations. The results show that camera pose information is surprisingly well-encoded within the VDiT’s architecture. The middle layers of the model contain the most accurate camera information, suggesting that camera signals are processed early in the network to guide later layers in generating visually consistent outputs aligned with the camera viewpoint.

read the caption

Figure 5: Video DiT is secretly a camera pose estimator. We perform linear probing of camera poses in each of VDiT blocks for various noise levels and observe that video DiT performs pose estimation under the hood. Its middle blocks carry the most accurate information about the camera locations and orientations, which indicates that the camera signal emerges in the early layers to help the middle and late blocks render other visual features aligned with the viewpoint.

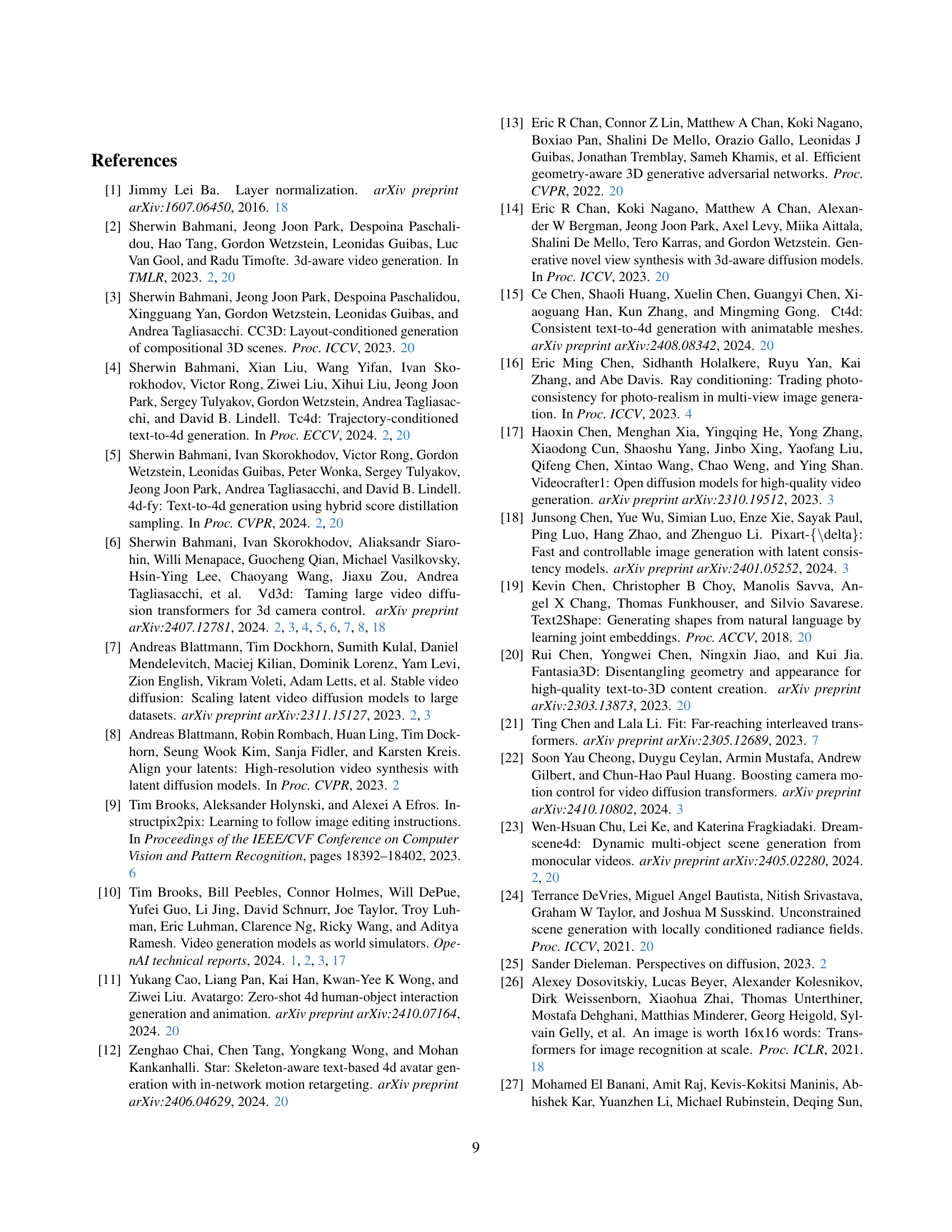

🔼 The figure shows a comparison of two video datasets used for training a video generation model. The top two rows display examples from the RealEstate10k dataset, which contains diverse camera movements but is biased towards static scenes. The bottom two rows show examples from a curated dataset of 20k videos featuring dynamic scenes filmed with stationary cameras. This curated dataset was created to address the bias in RealEstate10k and improve the model’s ability to generate dynamic scenes. Including this dataset in the training process led to a 17% improvement in visual quality when generating videos with out-of-distribution prompts (prompts unseen during training).

read the caption

Figure 6: RealEstate10k [198] videos (upper 2 rows) contain diverse camera trajectories, but are strongly biased towards static scenes. To mitigate this bias and also increase the concepts diversity, we curate 20202020K videos with stationary cameras, but dynamic content (lower 2 rows). Such dataset is easy to construct, and surprisingly effective. Section 4.3 shows that integrating it into our training allows to improve visual quality on out-of-distribution prompts by 17%percent1717\%17 %.

Full paper#