↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are powerful but computationally expensive for inference. Existing optimization techniques often compromise accuracy or require extensive resources. This paper introduces Puzzle, a novel framework to efficiently optimize LLMs for specific hardware. Puzzle employs neural architecture search (NAS) and a blockwise local knowledge distillation strategy to explore and refine model architectures that meet strict hardware constraints, while simultaneously maintaining high accuracy.

Puzzle’s effectiveness is demonstrated through Llama-3.1-Nemotron-51B, a model optimized for inference on a single NVIDIA H100 GPU. Nemotron-51B achieves a 2.17x speedup and maintains 98.4% of its parent model’s accuracy, showcasing Puzzle’s ability to achieve substantial performance gains without sacrificing accuracy. The low computational cost of Puzzle, requiring just 45 billion tokens compared to over 15 trillion for the original model, makes it a practical tool for LLM optimization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on LLM optimization and efficient inference because it introduces a novel framework, Puzzle, that significantly improves inference speed and reduces computational cost without sacrificing accuracy. The findings offer new avenues for model optimization, especially in the context of limited hardware resources, and provide a practical approach applicable to various LLMs, thus advancing the field of efficient AI. The open-sourcing of the optimized model, Nemotron-51B, further enhances its significance and usability.

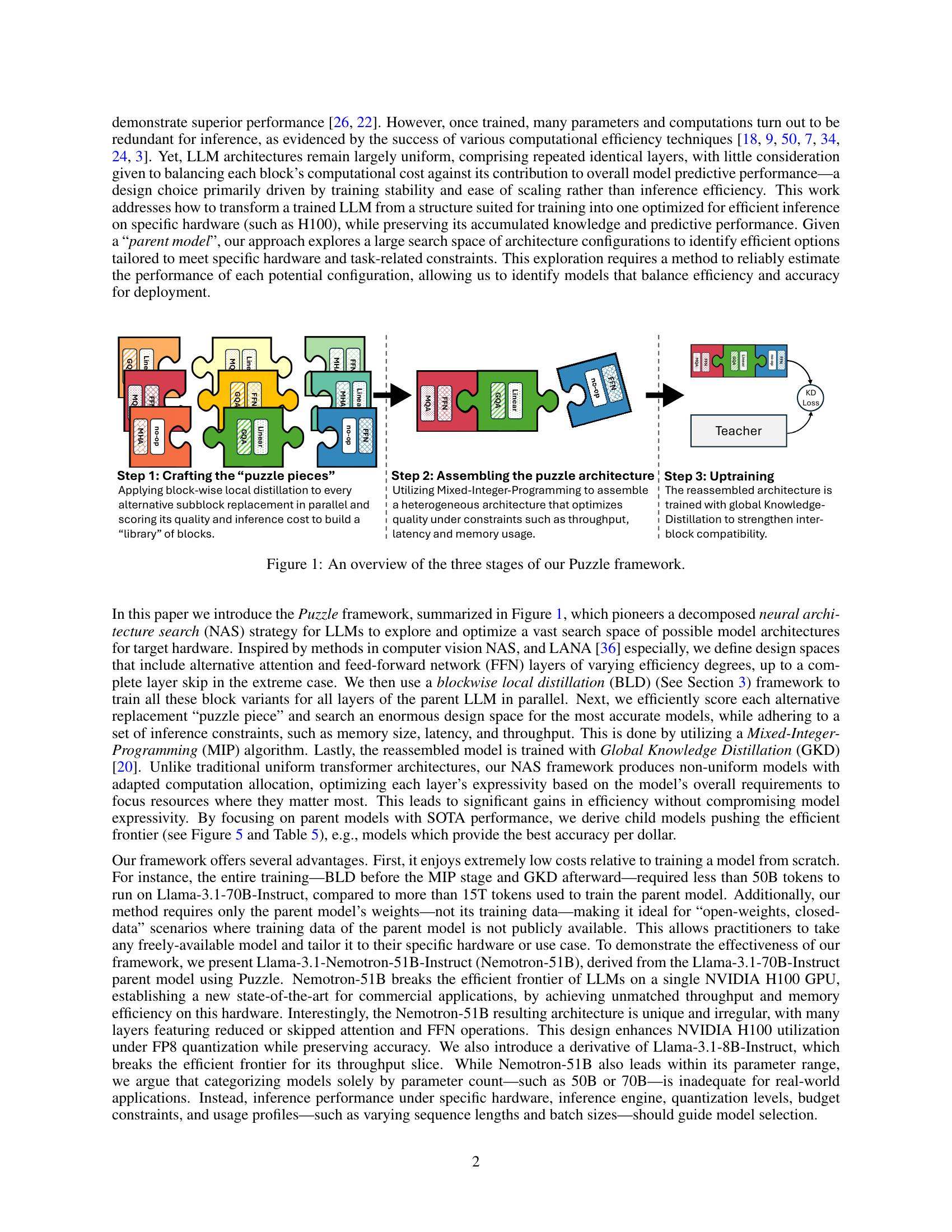

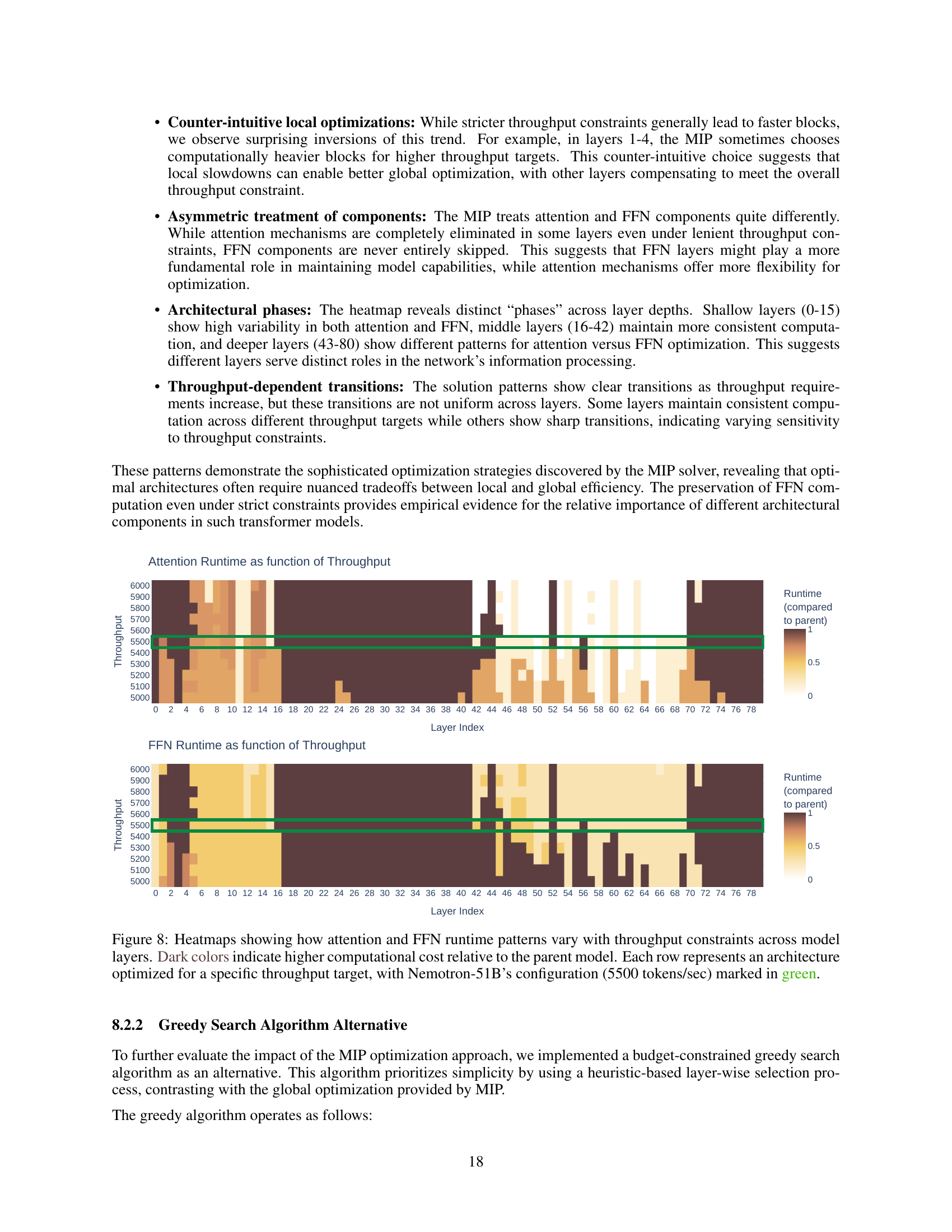

Visual Insights#

🔼 The Puzzle framework consists of three stages. In Stage 1, ‘Crafting the Puzzle Pieces,’ block-wise local distillation is used to train alternative sub-block replacements for each layer of the parent LLM in parallel. Each alternative replacement is scored based on its quality and inference cost. This creates a library of scored blocks, like puzzle pieces. Stage 2, ‘Assembling the Puzzle Architecture,’ utilizes mixed-integer programming (MIP) to assemble an optimized heterogeneous architecture by selecting the best-scoring blocks from the library, while satisfying constraints such as latency, memory usage, and throughput. Finally, Stage 3, ‘Uptraining,’ involves training the assembled architecture using global knowledge distillation to improve inter-block compatibility and performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: An overview of the three stages of our Puzzle framework.

| text{KLD}}$** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 78.39 | 8.67 | 82.55 | 0.19 |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | 78.55 | 7.71 | 77.83 | 0.31∗ |

| ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 79.26 | 8.85 | 83.88 | 0.14 |

| ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | 79.33 | 8.68 | 83.07 | 0.10 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 79.04 | 7.80 | 78.52 | 0.30∗ |

| ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 79.40 | 8.74 | 83.40 | 0.16 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 79.45 | 8.66 | 83.03 | 0.14 |

| ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 79.61 | 8.87 | 84.16 | 0.11 |

| Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct (parent) | 81.66 | 8.93 | 85.48 | 0.00 | ||

| Nemotron-51B-Instruct (child)† | 80.20 | 8.99 | 85.10 | 0.08 |

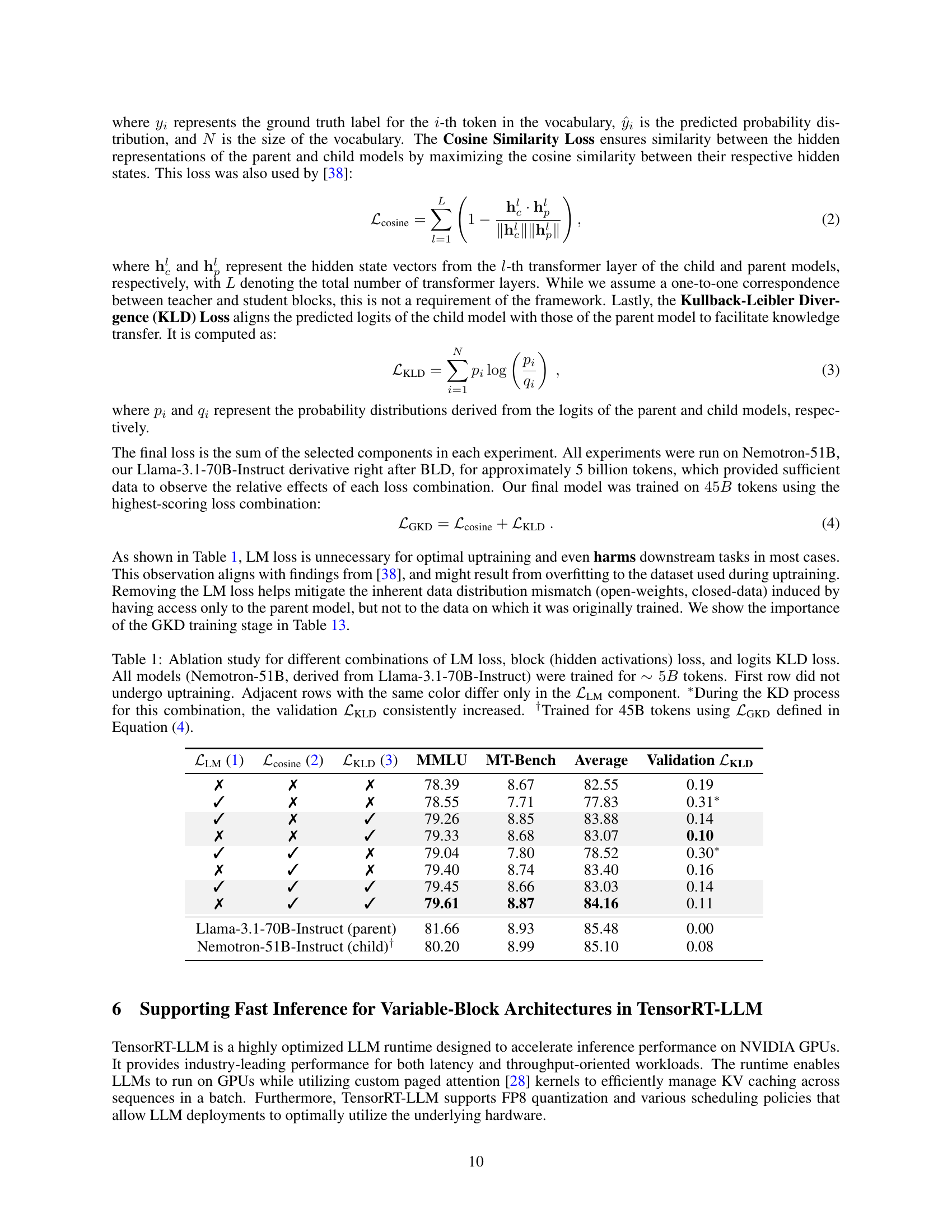

🔼 This table presents an ablation study evaluating different loss function combinations during the knowledge distillation (KD) process for fine-tuning the Nemotron-51B model. It investigates the impact of including the language modeling loss (ℒLM), hidden state cosine similarity loss (ℒcosine), and Kullback-Leibler divergence loss (ℒKLD). Each row represents a different combination of these losses used during the 5 billion token training phase. The results show the impact of each loss component on downstream task performance (MMLU, MT-Bench), and overall validation ℒKLD. The table highlights that the combination of cosine similarity loss and KL-divergence loss resulted in the best performance, while including the LM loss negatively impacts performance in most scenarios. Note that one model was additionally trained for 45B tokens using the best-performing loss combination.

read the caption

Table 1: Ablation study for different combinations of LM loss, block (hidden activations) loss, and logits KLD loss. All models (Nemotron-51B, derived from Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct) were trained for ∼5Bsimilar-toabsent5𝐵\sim 5B∼ 5 italic_B tokens. First row did not undergo uptraining. Adjacent rows with the same color differ only in the ℒLMsubscriptℒLM\mathcal{L}_{\text{LM}}caligraphic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT LM end_POSTSUBSCRIPT component. ∗During the KD process for this combination, the validation ℒKLDsubscriptℒKLD\mathcal{L}_{\text{KLD}}caligraphic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT KLD end_POSTSUBSCRIPT consistently increased. †Trained for 45B tokens using ℒGKDsubscriptℒGKD\mathcal{L}_{\text{GKD}}caligraphic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT GKD end_POSTSUBSCRIPT defined in Equation (4).

In-depth insights#

Inference-Optimized LLMs#

Inference-optimized LLMs represent a crucial advancement in large language model (LLM) technology, addressing the critical challenge of high computational costs during inference. Reducing inference costs is vital for wider LLM adoption, especially in resource-constrained environments and applications requiring real-time responses. Optimizations focus on techniques like model compression (e.g., pruning, quantization), architectural modifications (e.g., modifying attention mechanisms), and efficient hardware utilization. The goal is to maintain or minimally compromise accuracy while significantly improving inference speed and reducing memory footprint. This involves a trade-off: more aggressive optimization might lead to greater efficiency but potentially lower accuracy. Therefore, research into inference optimization often involves innovative search algorithms and sophisticated evaluation metrics to effectively navigate the complexity of this trade-off space, ensuring models are not only efficient but also capable of performing at a satisfactory level.

Puzzle Framework#

The Puzzle framework, as described in the research paper, presents a novel approach to optimizing Large Language Models (LLMs) for inference. It leverages a three-stage process: Crafting puzzle pieces involves using blockwise local distillation (BLD) to create a library of alternative sub-blocks, enabling parallel training and efficient exploration of the architecture search space. Assembling the puzzle architecture utilizes mixed-integer programming (MIP) to select the optimal combination of sub-blocks, balancing accuracy and efficiency under specific hardware constraints. Finally, uptraining refines the assembled architecture via global knowledge distillation (GKD), enhancing inter-block compatibility and overall model performance. This decomposed approach offers significant computational advantages over traditional methods, making it practical to optimize LLMs with tens of billions of parameters. Puzzle’s key strength lies in its adaptability; it can be tailored to diverse hardware and inference scenarios by modifying constraints within the MIP optimization stage, leading to efficient deployment-ready models. The framework’s real-world impact is demonstrated through the creation of Llama-3.1-Nemotron-51B-Instruct, showcasing significant speed improvements while preserving accuracy. This highlights the importance of focusing on inference optimization, rather than solely on parameter count, when selecting LLMs for specific applications.

Blockwise Distillation#

Blockwise distillation is a crucial technique presented in the paper for efficient neural architecture search (NAS). Instead of distilling an entire large language model (LLM) at once, which is computationally expensive, it breaks down the distillation process into smaller, manageable units. Each block of the LLM is distilled independently and in parallel, significantly reducing the training time and resource requirements. This parallel processing enables the exploration of a vast search space efficiently, allowing for identifying optimal LLM architectures tailored to specific hardware constraints. The independent training of blocks also increases stability and allows for higher learning rates, leading to faster convergence. By focusing on individual blocks, the approach simplifies the overall distillation process and makes it more tractable. This decomposition is key to enabling the unprecedented scale of NAS achieved in the paper. The efficacy of blockwise distillation is highlighted by its success in generating efficient LLMs, such as Nemotron-51B, which retains high accuracy while achieving significant improvements in inference throughput. However, it’s important to note that blockwise distillation alone does not guarantee compatibility between blocks in the final architecture, hence the paper suggests the utilization of a global knowledge distillation step after this stage. This two-stage distillation process (blockwise, then global) is critical to the Puzzle framework’s effectiveness.

Decomposed NAS#

Decomposed Neural Architecture Search (NAS) offers a scalable solution for optimizing large language models (LLMs). Unlike traditional NAS which searches the entire architecture space, decomposed NAS breaks down the search into smaller, manageable sub-problems. This approach significantly reduces the computational cost associated with evaluating numerous architectural configurations. Blockwise local distillation plays a crucial role, training sub-blocks independently and efficiently, before they are assembled into the final model. The mixed-integer programming (MIP) approach is a valuable tool for optimizing the selection of these blocks to meet specified hardware constraints, allowing for efficient model deployment. By decomposing the search, this methodology allows for exploring a vastly larger design space and efficiently building accurate and efficient LLMs for target hardware and constraints.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of a research paper on large language model (LLM) optimization would ideally delve into several key areas. Extending the framework to handle more complex tasks, such as multi-modal processing (vision-language) or tasks requiring complex reasoning like chain-of-thought prompting, would be crucial. Further research should investigate more sophisticated search algorithms than Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP), perhaps incorporating reinforcement learning or evolutionary strategies for more efficient architecture exploration. A deeper understanding of the relationship between model architectures and specific capabilities is also needed, paving the way for more targeted optimization strategies. Robustness evaluations concerning distribution shifts and the models’ ability to adapt to new tasks through fine-tuning would validate the approach’s practicality and adaptability in real-world scenarios. Finally, exploring techniques for dynamic architecture adaptation is key; this would allow models to adjust their structure during inference based on specific needs, further improving efficiency and performance. These future directions would not only advance the field but also ensure Puzzle’s continued relevance and effectiveness across different tasks and hardware environments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

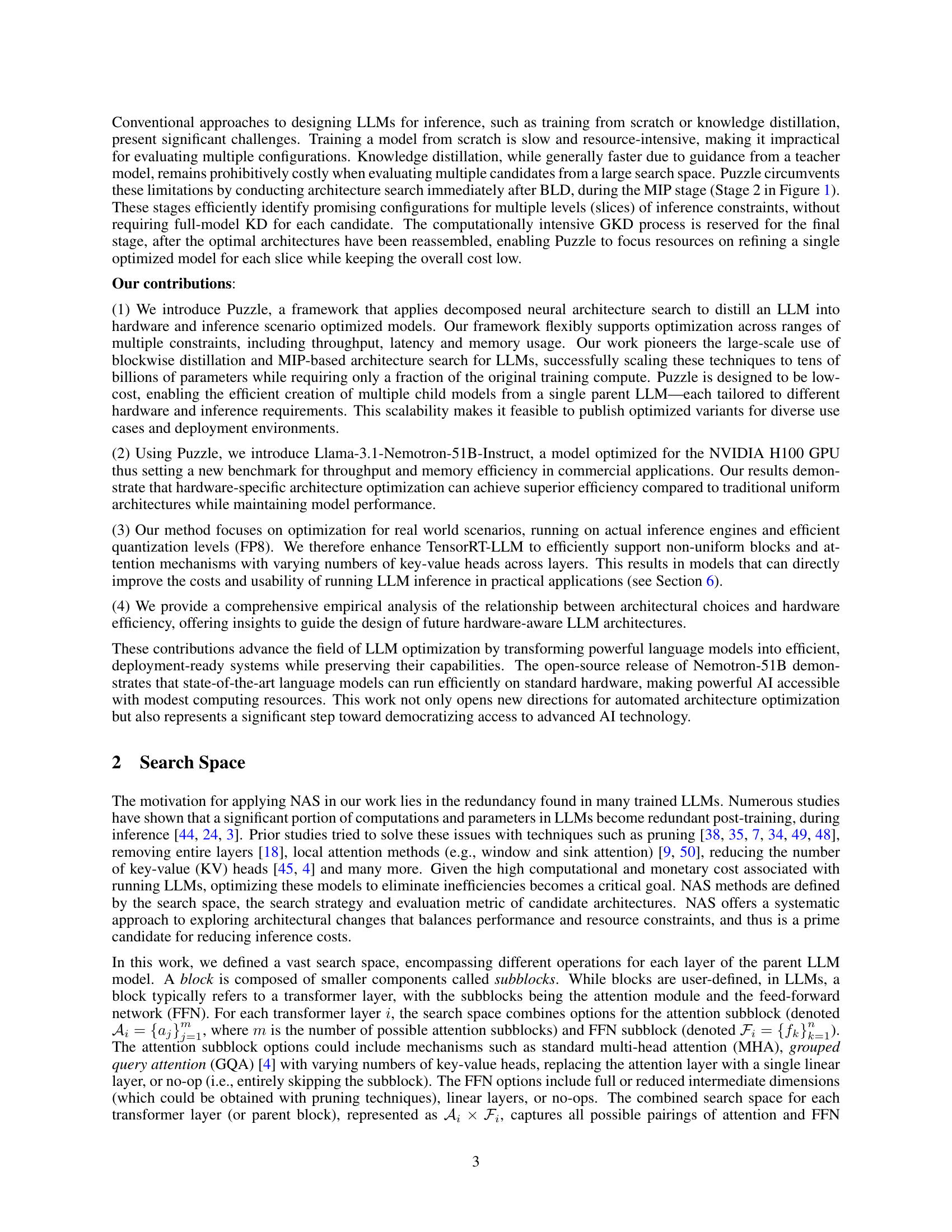

🔼 The figure illustrates the Blockwise Local Distillation (BLD) process, a key component of the Puzzle framework. Instead of distilling an entire model at once, BLD trains individual blocks (typically transformer layers) of the child model independently and in parallel. Each child block is trained to mimic its corresponding parent block using the parent’s activations as input. This is done separately for each block, allowing for parallelization across multiple GPUs and resulting in significant computational savings. The individual trained blocks are then assembled to form the complete, optimized child model. The loss function used is the mean squared error (MSE) between the parent block’s output and the child block’s output.

read the caption

Figure 2: Blockwise local distillation (BLD): each block is trained in parallel and independently.

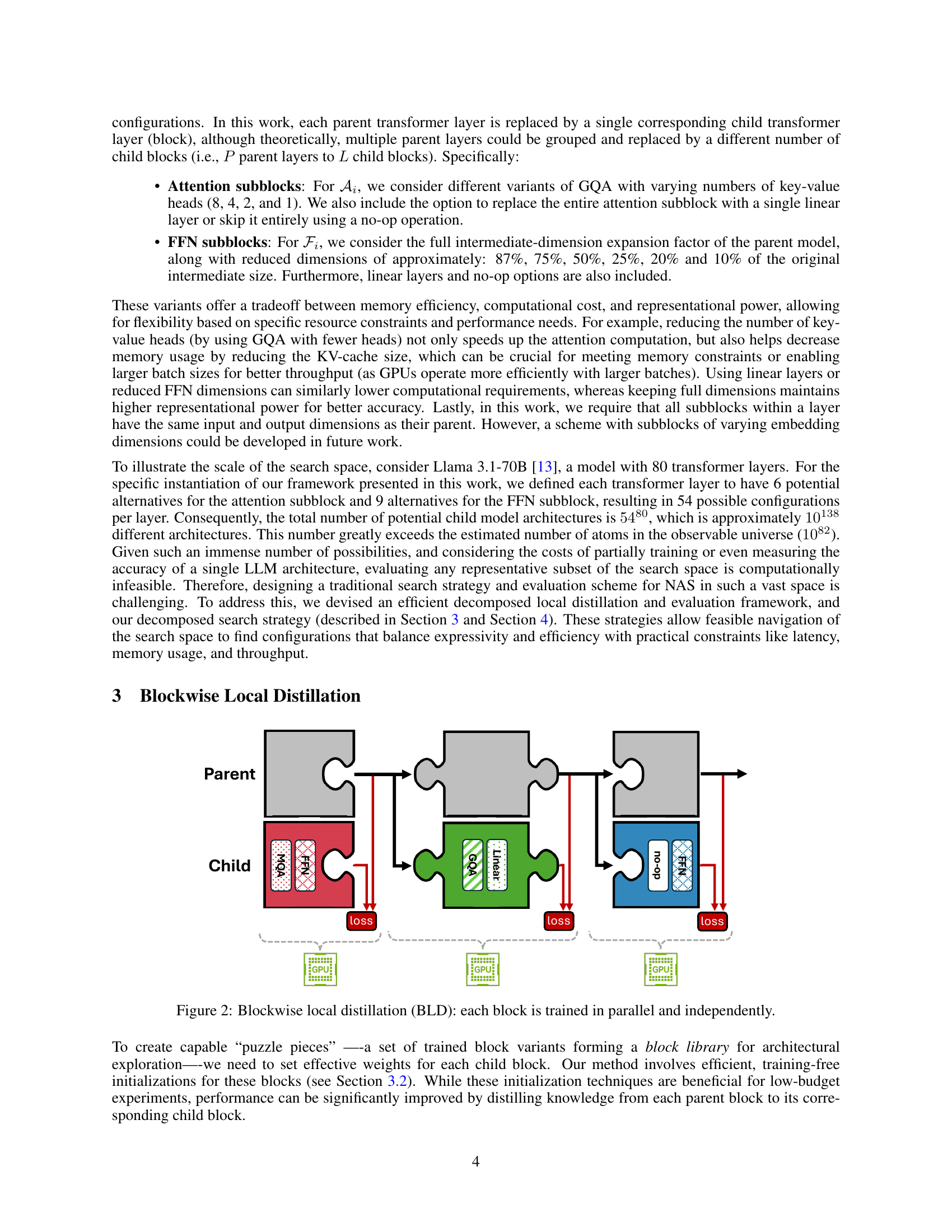

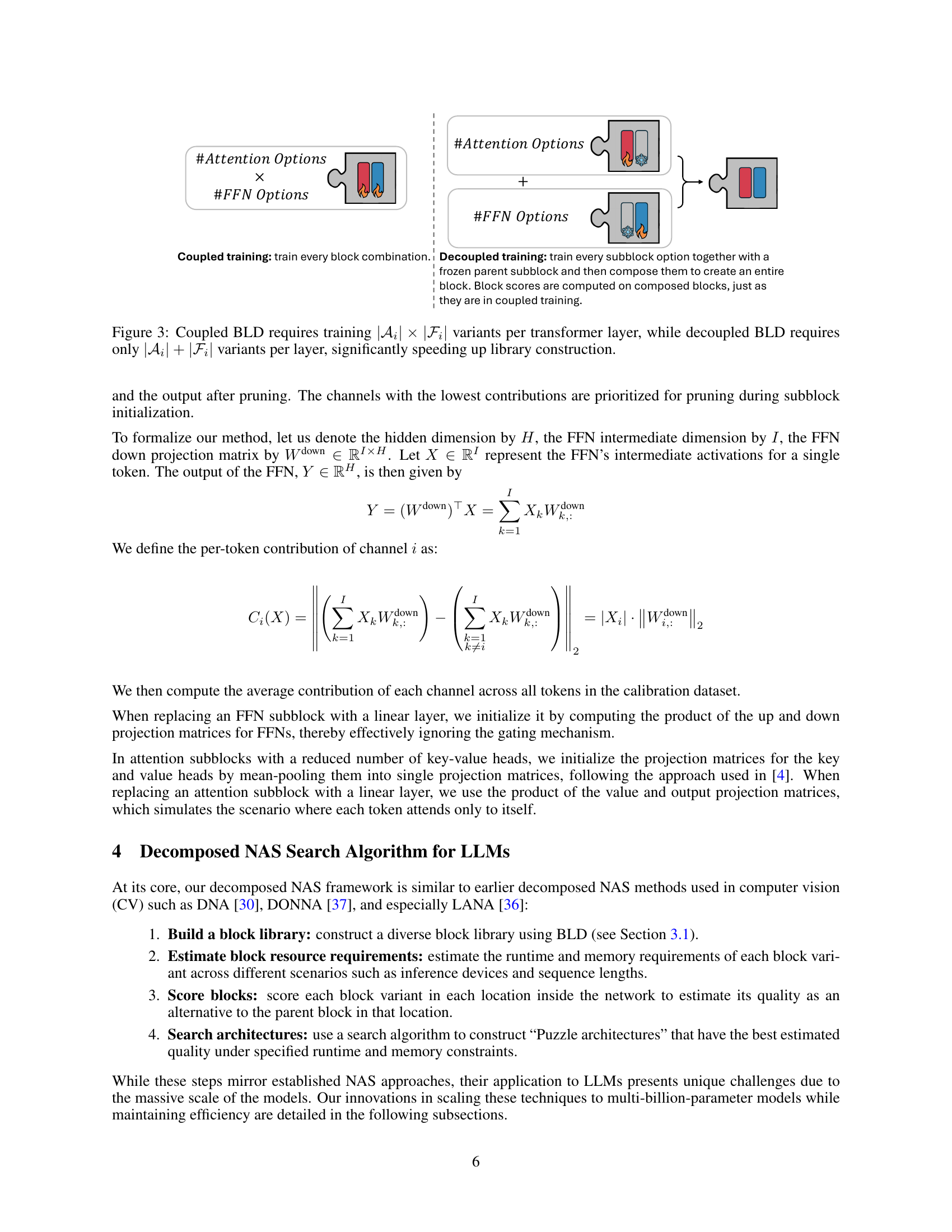

🔼 The figure illustrates the computational cost difference between coupled and decoupled Blockwise Local Distillation (BLD) methods in training sub-blocks for Neural Architecture Search (NAS). Coupled BLD trains all combinations of attention sub-block variants (|Ai|) and FFN sub-block variants (|Fi|) for each layer, resulting in |Ai| * |Fi| training instances per layer. In contrast, decoupled BLD trains each sub-block type separately, resulting in |Ai| + |Fi| training instances per layer. This significantly reduces the overall training cost, accelerating the construction of the block library required for the NAS process.

read the caption

Figure 3: Coupled BLD requires training |𝒜i|×|ℱi|subscript𝒜𝑖subscriptℱ𝑖|\mathcal{A}_{i}|\times|\mathcal{F}_{i}|| caligraphic_A start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT | × | caligraphic_F start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT | variants per transformer layer, while decoupled BLD requires only |𝒜i|+|ℱi|subscript𝒜𝑖subscriptℱ𝑖|\mathcal{A}_{i}|+|\mathcal{F}_{i}|| caligraphic_A start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT | + | caligraphic_F start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT | variants per layer, significantly speeding up library construction.

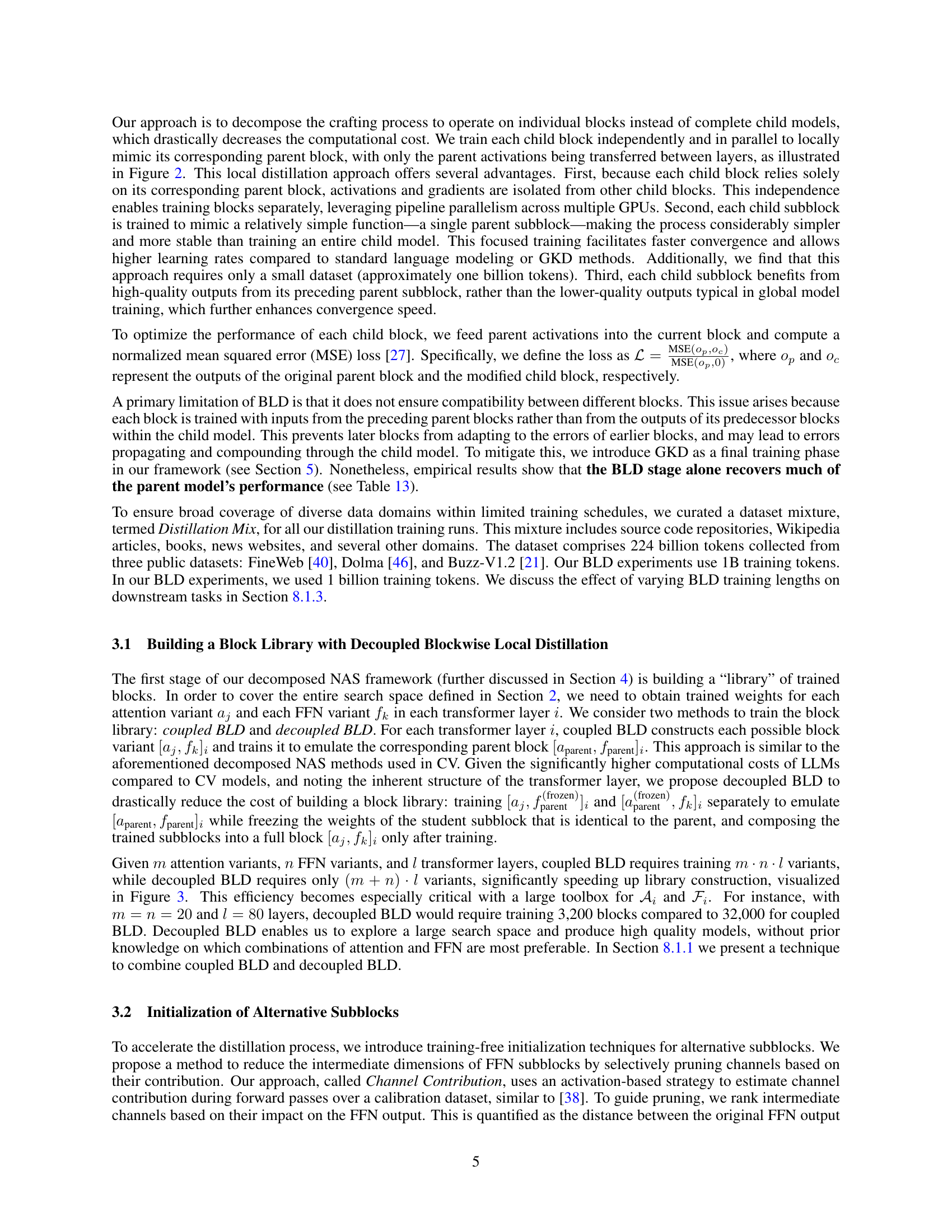

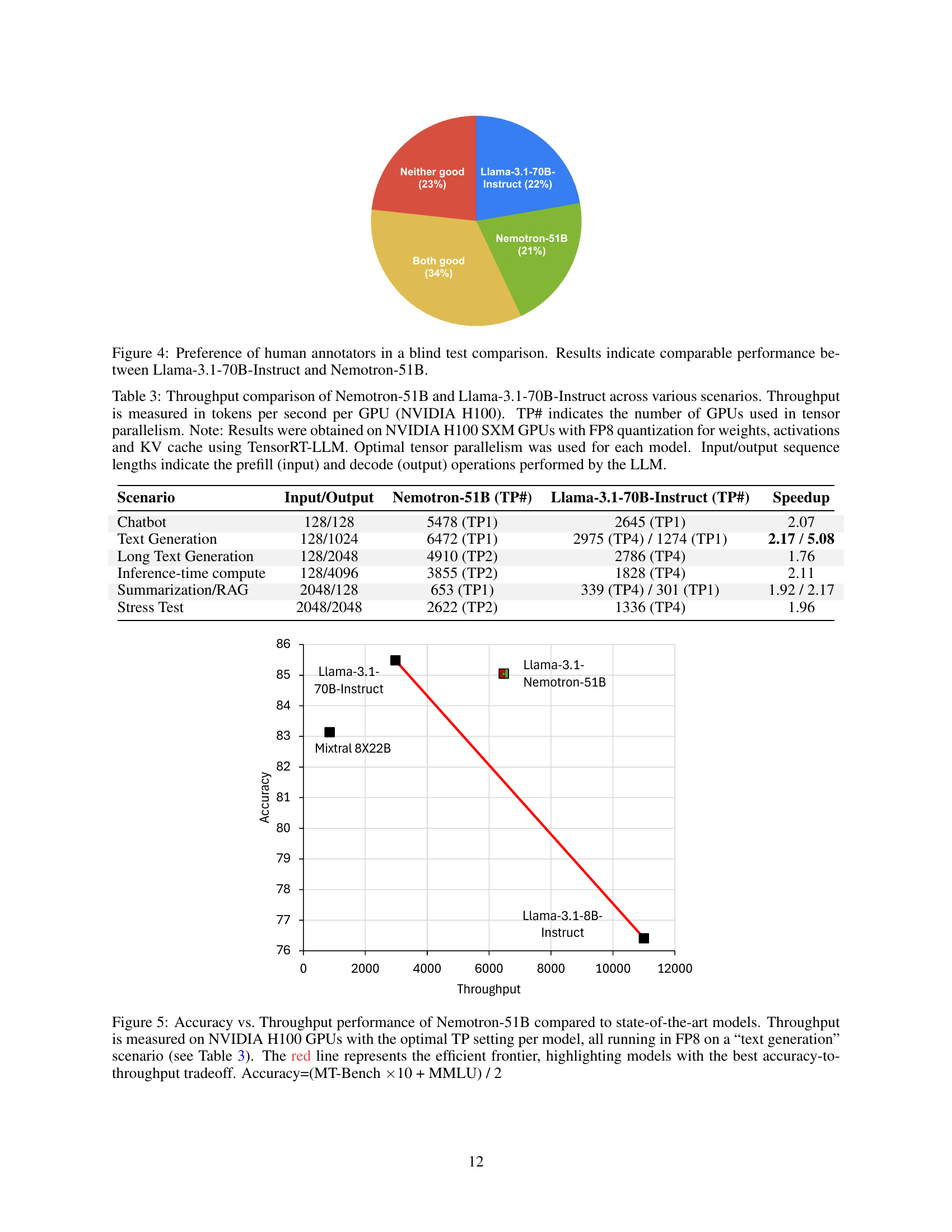

🔼 Human annotators conducted a blind test comparing the performance of Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct and Nemotron-51B across various tasks. The results show that there is no statistically significant difference in perceived quality between the two models, indicating that Nemotron-51B, despite having significantly fewer parameters, maintains performance comparable to its larger counterpart.

read the caption

Figure 4: Preference of human annotators in a blind test comparison. Results indicate comparable performance between Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct and Nemotron-51B.

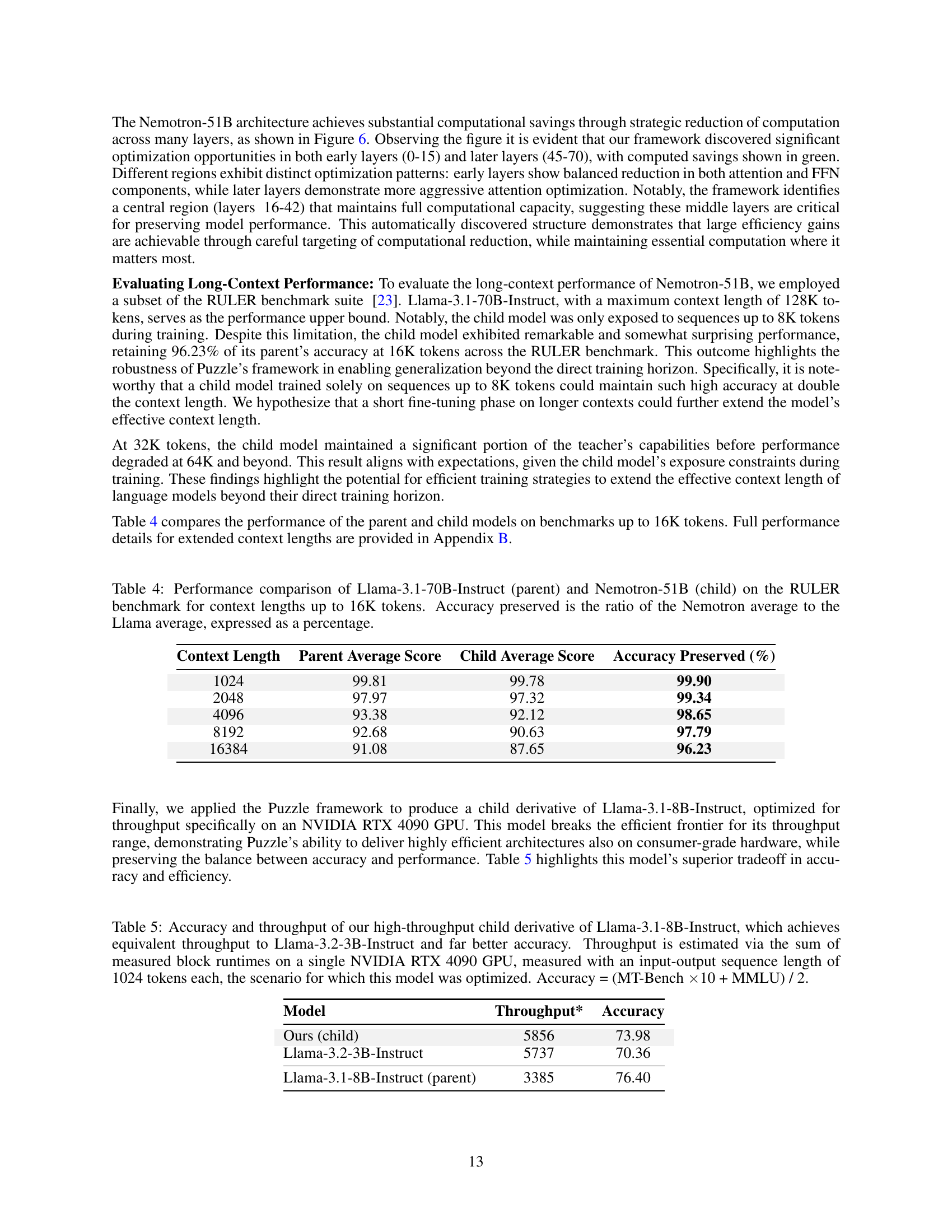

🔼 Figure 5 illustrates the performance of Nemotron-51B against other state-of-the-art large language models. The x-axis represents the throughput (tokens processed per second) achieved on NVIDIA H100 GPUs using FP8 precision and optimal tensor parallelism for each model during text generation tasks (as defined in Table 3). The y-axis shows the accuracy, calculated as the average of MT-Bench scores multiplied by 10 and MMLU scores, divided by 2. The red line indicates the Pareto frontier; points on or above the line represent models with optimal accuracy-to-throughput ratios. Nemotron-51B is shown to achieve high accuracy with good throughput, making it efficient for real-world deployment.

read the caption

Figure 5: Accuracy vs. Throughput performance of Nemotron-51B compared to state-of-the-art models. Throughput is measured on NVIDIA H100 GPUs with the optimal TP setting per model, all running in FP8 on a “text generation” scenario (see Table 3). The red line represents the efficient frontier, highlighting models with the best accuracy-to-throughput tradeoff. Accuracy=(MT-Bench ×\times×10 + MMLU) / 2

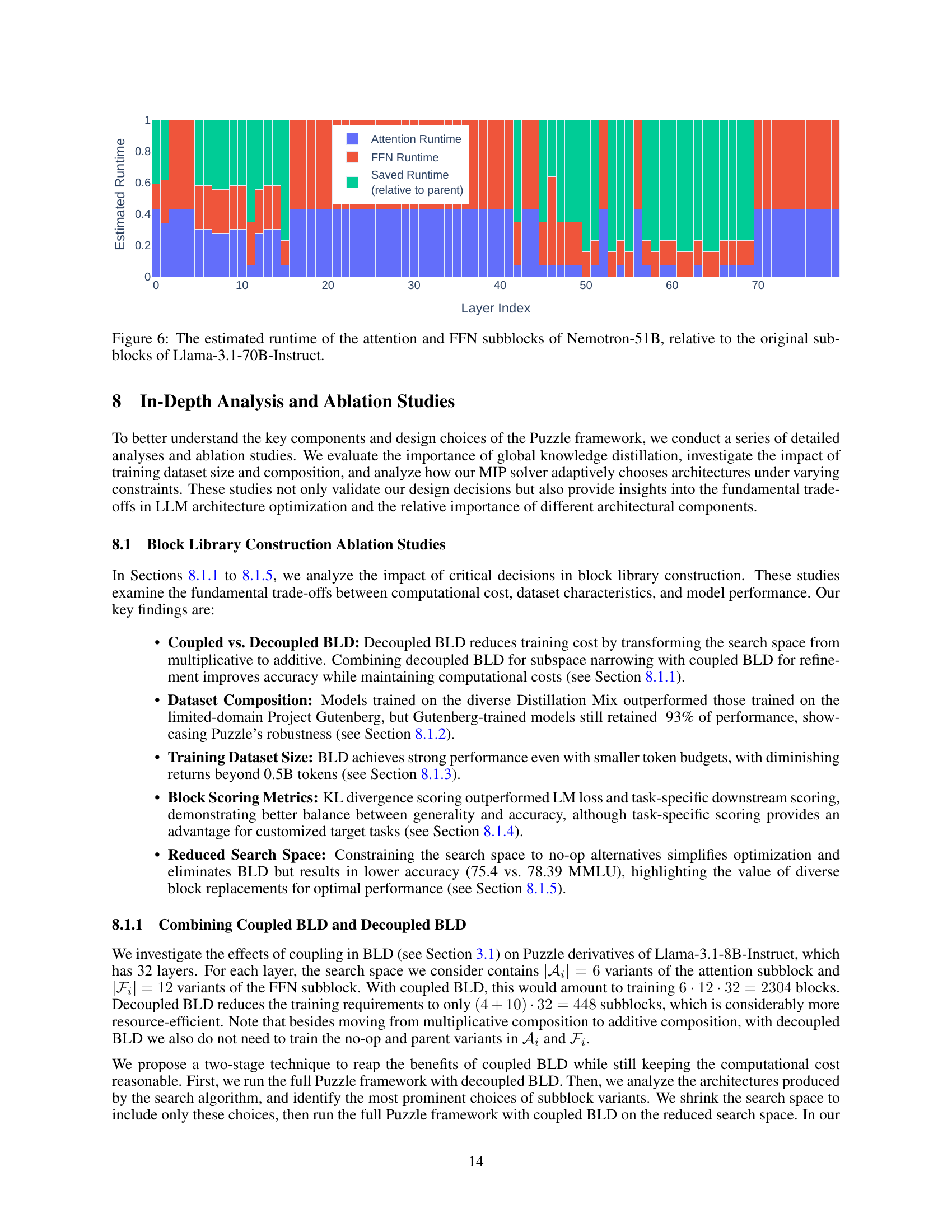

🔼 Figure 6 shows a comparison of the runtime of attention and feed-forward network (FFN) sub-blocks in Nemotron-51B, a smaller model created by the Puzzle framework, compared to the original Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct model. The graph plots the estimated runtime of each sub-block type (attention and FFN) across the layers of Nemotron-51B, expressed as a fraction of the original runtime in Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct. This allows visualization of where the Puzzle framework made significant optimizations (shown in green), leading to reduced computation time in Nemotron-51B. The graph also highlights that certain layers retained their original computational complexity, indicating that these sections of the model were deemed critical for maintaining model performance.

read the caption

Figure 6: The estimated runtime of the attention and FFN subblocks of Nemotron-51B, relative to the original subblocks of Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct.

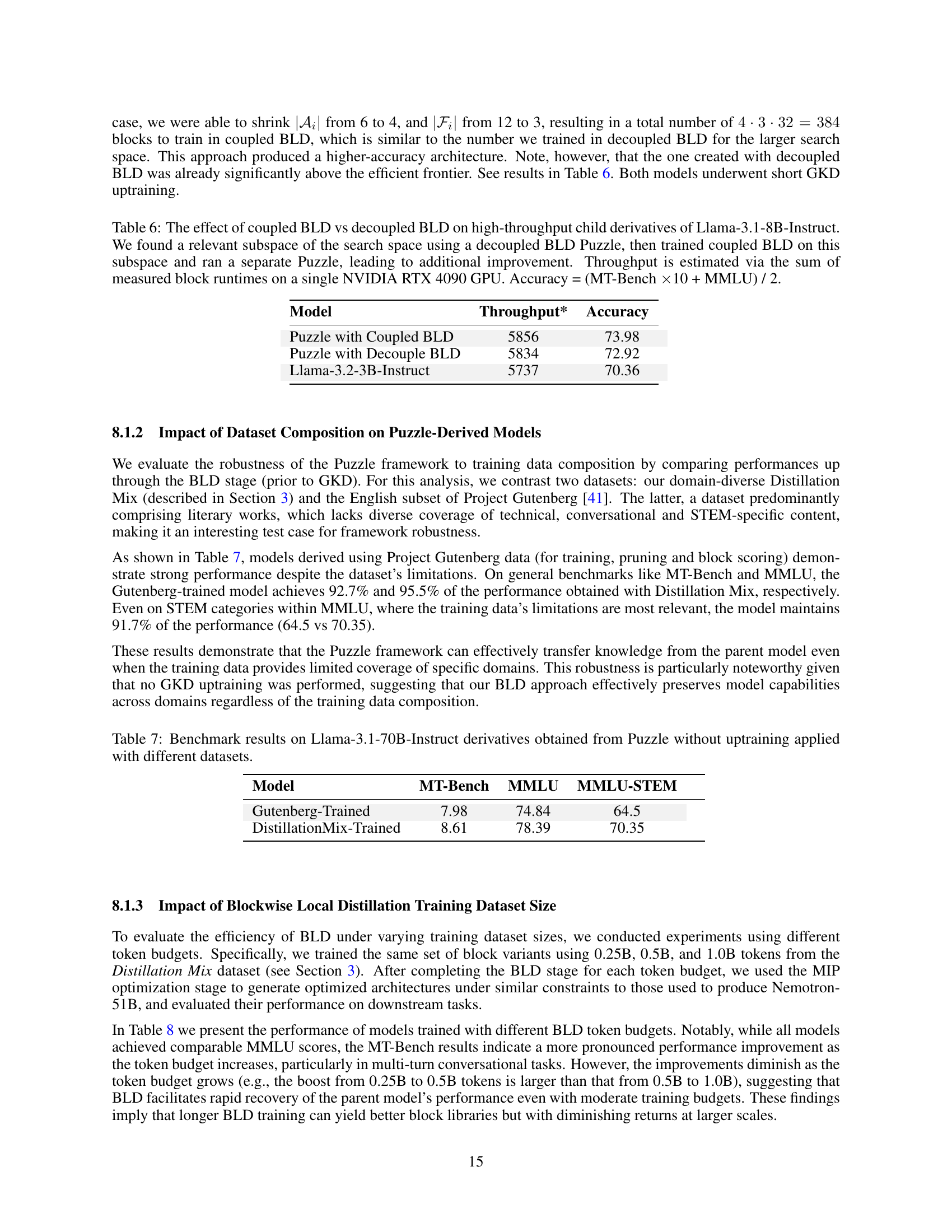

🔼 Figure 7 compares different methods for scoring alternative blocks during neural architecture search (NAS) for LLMs. It shows the accuracy and throughput of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct models optimized using two different scoring metrics: LM loss and KL divergence. LM loss measures the overall quality decrease when replacing a block, while KL divergence measures the difference between the original and modified models’ outputs. The results indicate that using KL divergence for scoring leads to better model architectures (higher accuracy) compared to using LM loss. The accuracy is calculated as the average of MT-Bench and MMLU scores, weighted 10:1, and throughput is estimated based on the sum of block runtimes on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

read the caption

Figure 7: Accuracy vs. Throughput performance of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct child derivatives, some constructed using LM loss as replace-1-block scores, and some constructed using KL divergence as replace-1-block scores. LM loss aims to capture the general quality degradation induced by changing a specific parent block, while KL divergence aims to capture the distance from the parent model induced by this change. KL divergence results in better architecture choices. Accuracy = (MT-Bench ×\times×10 + MMLU) / 2. Throughput is estimated via the sum of measured block runtimes on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

More on tables

| Benchmark | Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct | Nemotron-51B | Accuracy Preserved (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winogrande [43] | 85.08 | 84.53 | 99.35 |

| ARC Challenge [11] | 70.39 | 69.20 | 98.30 |

| MMLU [19] | 81.66 | 80.20 | 98.21 |

| HellaSwag [52] | 86.44 | 85.58 | 99.01 |

| GSM8K [12] | 92.04 | 91.43 | 99.34 |

| TruthfulQA [31] | 59.86 | 58.63 | 97.94 |

| XLSum English [17] | 33.86 | 31.61 | 93.36 |

| MMLU Chat* | 81.76 | 80.58 | 98.55 |

| GSM8K Chat* | 81.58 | 81.88 | 100.37 |

| Instruct HumanEval (n=20) [10]** | 75.85 | 73.84 | 97.35 |

| MT-Bench [53] | 8.93 | 8.99 | 100.67 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of the smaller, optimized model Nemotron-51B against its larger parent model Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct across multiple established language model benchmarks. For each benchmark, it shows the accuracy achieved by both models and calculates the percentage of the parent model’s accuracy that the smaller model retains (Accuracy Preserved). This illustrates the extent to which Nemotron-51B maintains performance while being significantly more efficient. The benchmarks include a variety of tasks assessing different capabilities of the language model, allowing for a more thorough comparison. Notes are provided to clarify specific variations of certain benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 2: Accuracy comparison of Nemotron-51B with Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct across several benchmarks. Accuracy preserved is the ratio of child to parent accuracy. *Chat prompt as defined in Adler et al. [2]. **version by CodeParrot.

| Scenario | Input/Output | Nemotron-51B (TP#) | Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct (TP#) | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chatbot | 128/128 | 5478 (TP1) | 2645 (TP1) | 2.07 |

| Text Generation | 128/1024 | 6472 (TP1) | 2975 (TP4) / 1274 (TP1) | 2.17 / 5.08 |

| Long Text Generation | 128/2048 | 4910 (TP2) | 2786 (TP4) | 1.76 |

| Inference-time compute | 128/4096 | 3855 (TP2) | 1828 (TP4) | 2.11 |

| Summarization/RAG | 2048/128 | 653 (TP1) | 339 (TP4) / 301 (TP1) | 1.92 / 2.17 |

| Stress Test | 2048/2048 | 2622 (TP2) | 1336 (TP4) | 1.96 |

🔼 This table compares the inference throughput of the Nemotron-51B model and its parent model, Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct, across different scenarios. Throughput is measured in tokens per second per NVIDIA H100 GPU. The number of GPUs used for tensor parallelism is also shown. The experiments used FP8 quantization for weights, activations, and KV cache with the TensorRT-LLM inference engine. Optimal tensor parallelism was used for both models. The input/output sequence lengths show the lengths used for the prefill (input) and decoding (output) steps of each LLM.

read the caption

Table 3: Throughput comparison of Nemotron-51B and Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct across various scenarios. Throughput is measured in tokens per second per GPU (NVIDIA H100). TP# indicates the number of GPUs used in tensor parallelism. Note: Results were obtained on NVIDIA H100 SXM GPUs with FP8 quantization for weights, activations and KV cache using TensorRT-LLM. Optimal tensor parallelism was used for each model. Input/output sequence lengths indicate the prefill (input) and decode (output) operations performed by the LLM.

| Context Length | Parent Average Score | Child Average Score | Accuracy Preserved (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1024 | 99.81 | 99.78 | 99.90 |

| 2048 | 97.97 | 97.32 | 99.34 |

| 4096 | 93.38 | 92.12 | 98.65 |

| 8192 | 92.68 | 90.63 | 97.79 |

| 16384 | 91.08 | 87.65 | 96.23 |

🔼 This table presents a detailed comparison of the performance of Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct (the original, larger model) and Nemotron-51B (the optimized, smaller model) on the RULER benchmark. The RULER benchmark tests various reasoning abilities of language models across different context lengths (the amount of text the model processes at once). The table shows the average scores achieved by both models at context lengths of 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, and 16384 tokens. A key metric is ‘Accuracy Preserved,’ which indicates the percentage of the original model’s accuracy retained by Nemotron-51B at each context length. This illustrates how well the optimization process maintained performance while reducing model size and computational needs. It helps to understand the tradeoff between model size and accuracy in different context lengths.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance comparison of Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct (parent) and Nemotron-51B (child) on the RULER benchmark for context lengths up to 16K tokens. Accuracy preserved is the ratio of the Nemotron average to the Llama average, expressed as a percentage.

| Model | Throughput* | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Ours (child) | 5856 | 73.98 |

| Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct | 5737 | 70.36 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (parent) | 3385 | 76.40 |

🔼 Table 5 presents a comparison of the performance of three language models: a new high-throughput model derived from Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct using the Puzzle framework, Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, and the original Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. The comparison focuses on throughput (tokens processed per second) and accuracy. Throughput is measured using a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, processing input and output sequences of 1024 tokens each. Accuracy is calculated as the average of two benchmarks: MT-Bench multiplied by 10, and MMLU, divided by 2. The table highlights that the new Puzzle-derived model achieves a throughput comparable to Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct while demonstrating significantly higher accuracy.

read the caption

Table 5: Accuracy and throughput of our high-throughput child derivative of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, which achieves equivalent throughput to Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct and far better accuracy. Throughput is estimated via the sum of measured block runtimes on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, measured with an input-output sequence length of 1024 tokens each, the scenario for which this model was optimized. Accuracy = (MT-Bench ×\times×10 + MMLU) / 2.

| Model | Throughput* | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Puzzle with Coupled BLD | 5856 | 73.98 |

| Puzzle with Decouple BLD | 5834 | 72.92 |

| Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct | 5737 | 70.36 |

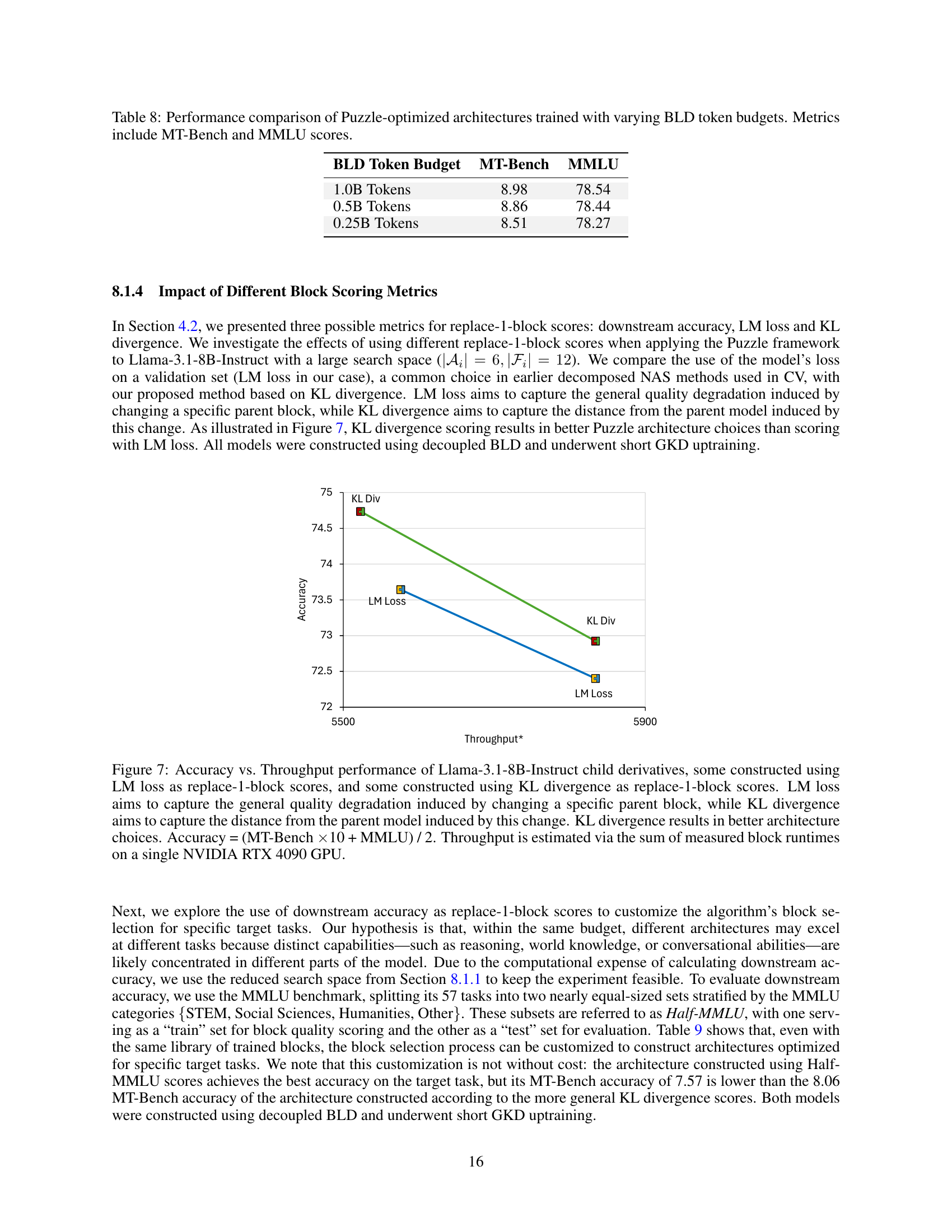

🔼 This table compares the performance of two different approaches to building a library of blocks for training a smaller, more efficient language model (LLM) from a larger one. The first approach uses ‘decoupled BLD,’ which trains the blocks independently to save computational resources. The second then uses ‘coupled BLD,’ training combinations of blocks together after having identified a smaller, more promising search space using the decoupled method. The table shows that the two-stage approach (decoupled followed by coupled BLD) leads to better performance (higher accuracy) compared to using only the decoupled approach, showcasing the effectiveness of this combined strategy for efficient LLM optimization. Throughput is calculated for a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. Accuracy is a combined score from the MT-Bench and MMLU benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 6: The effect of coupled BLD vs decoupled BLD on high-throughput child derivatives of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. We found a relevant subspace of the search space using a decoupled BLD Puzzle, then trained coupled BLD on this subspace and ran a separate Puzzle, leading to additional improvement. Throughput is estimated via the sum of measured block runtimes on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. Accuracy = (MT-Bench ×\times×10 + MMLU) / 2.

| Model | MT-Bench | MMLU | MMLU-STEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gutenberg-Trained | 7.98 | 74.84 | 64.5 |

| DistillationMix-Trained | 8.61 | 78.39 | 70.35 |

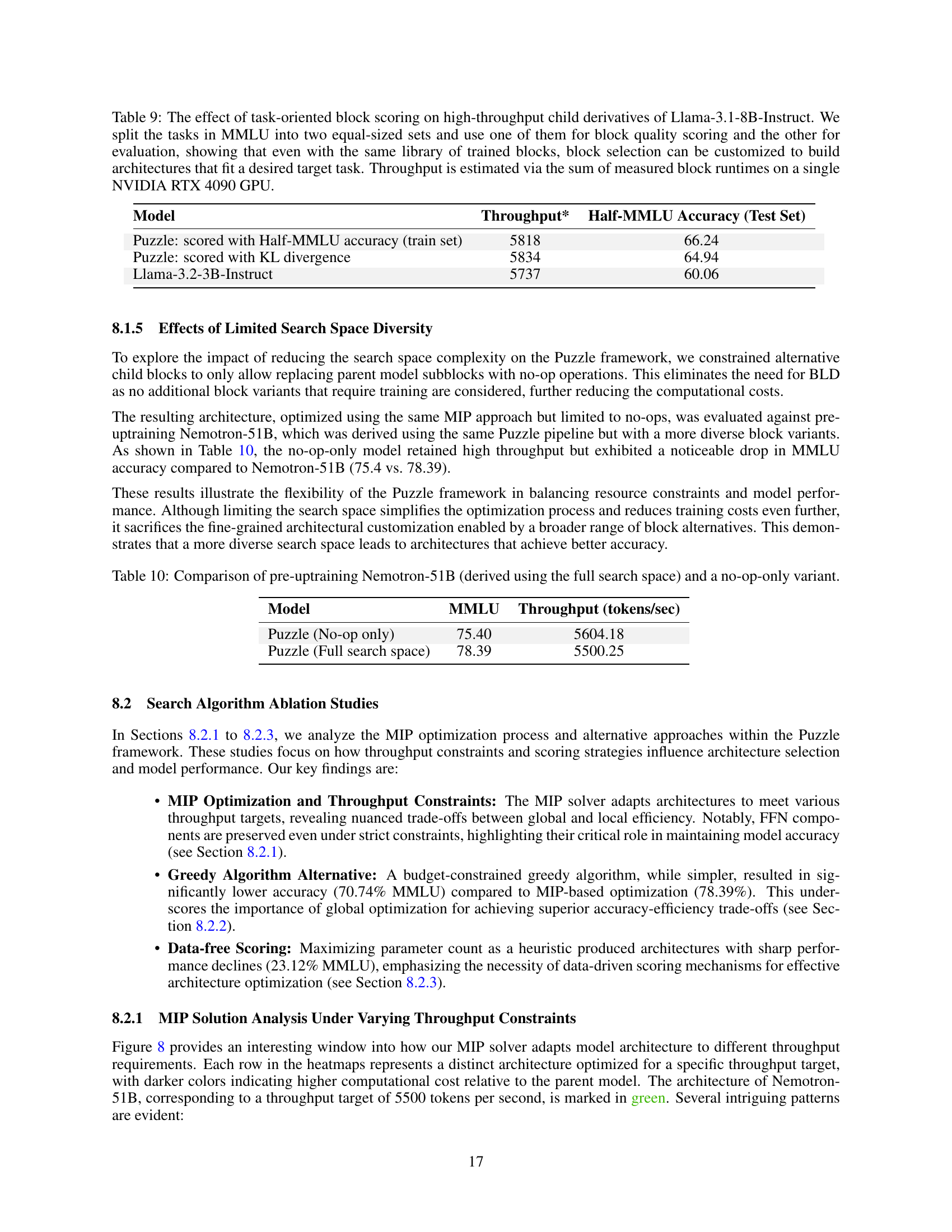

🔼 This table presents the results of applying the Puzzle framework to create LLM derivatives from the Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct model, without the final global knowledge distillation (GKD) uptraining step. It compares the performance of models trained on two different datasets: the diverse Distillation Mix and the more limited Project Gutenberg dataset. The performance metrics include the MT-Bench and MMLU scores to evaluate the models’ capabilities across various tasks and domains. The purpose is to assess how well the Puzzle framework preserves model performance with different training data.

read the caption

Table 7: Benchmark results on Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct derivatives obtained from Puzzle without uptraining applied with different datasets.

| BLD Token Budget | MT-Bench | MMLU |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0B Tokens | 8.98 | 78.54 |

| 0.5B Tokens | 8.86 | 78.44 |

| 0.25B Tokens | 8.51 | 78.27 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of LLMs whose architectures were optimized using the Puzzle framework. The models were trained with varying amounts of training data during the Blockwise Local Distillation (BLD) phase. The comparison focuses on two key metrics: MT-Bench scores and MMLU scores. This allows assessment of how much the amount of training data in the BLD stage impacts downstream performance in terms of these two metrics.

read the caption

Table 8: Performance comparison of Puzzle-optimized architectures trained with varying BLD token budgets. Metrics include MT-Bench and MMLU scores.

| Model | Throughput* | Half-MMLU Accuracy (Test Set) |

|---|---|---|

| Puzzle: scored with Half-MMLU accuracy (train set) | 5818 | 66.24 |

| Puzzle: scored with KL divergence | 5834 | 64.94 |

| Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct | 5737 | 60.06 |

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the effect of using different block scoring metrics within the Puzzle framework. Specifically, it investigates how using a subset of the MMLU benchmark for scoring blocks (Half-MMLU), rather than a general metric like KL divergence, impacts the resulting child model’s performance. The experiment used a reduced search space to manage computational costs. The table shows the throughput (estimated via summed block runtimes on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU) and accuracy (measured using the test set from the split MMLU benchmark) of different models to illustrate how tailoring block scoring to specific downstream tasks can influence the final model’s strengths and weaknesses.

read the caption

Table 9: The effect of task-oriented block scoring on high-throughput child derivatives of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. We split the tasks in MMLU into two equal-sized sets and use one of them for block quality scoring and the other for evaluation, showing that even with the same library of trained blocks, block selection can be customized to build architectures that fit a desired target task. Throughput is estimated via the sum of measured block runtimes on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

| Model | MMLU | Throughput (tokens/sec) |

|---|---|---|

| Puzzle (No-op only) | 75.40 | 5604.18 |

| Puzzle (Full search space) | 78.39 | 5500.25 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of two versions of the Nemotron-51B model. One version was created using the full search space of the Puzzle framework’s architecture search, while the other was constrained to only use ’no-op’ operations (meaning no alterations made to the original model’s architecture). The comparison focuses on the MMLU score, which measures accuracy across diverse tasks, and the throughput (in tokens per second), indicating inference speed. This demonstrates the impact of search space size on model accuracy and efficiency.

read the caption

Table 10: Comparison of pre-uptraining Nemotron-51B (derived using the full search space) and a no-op-only variant.

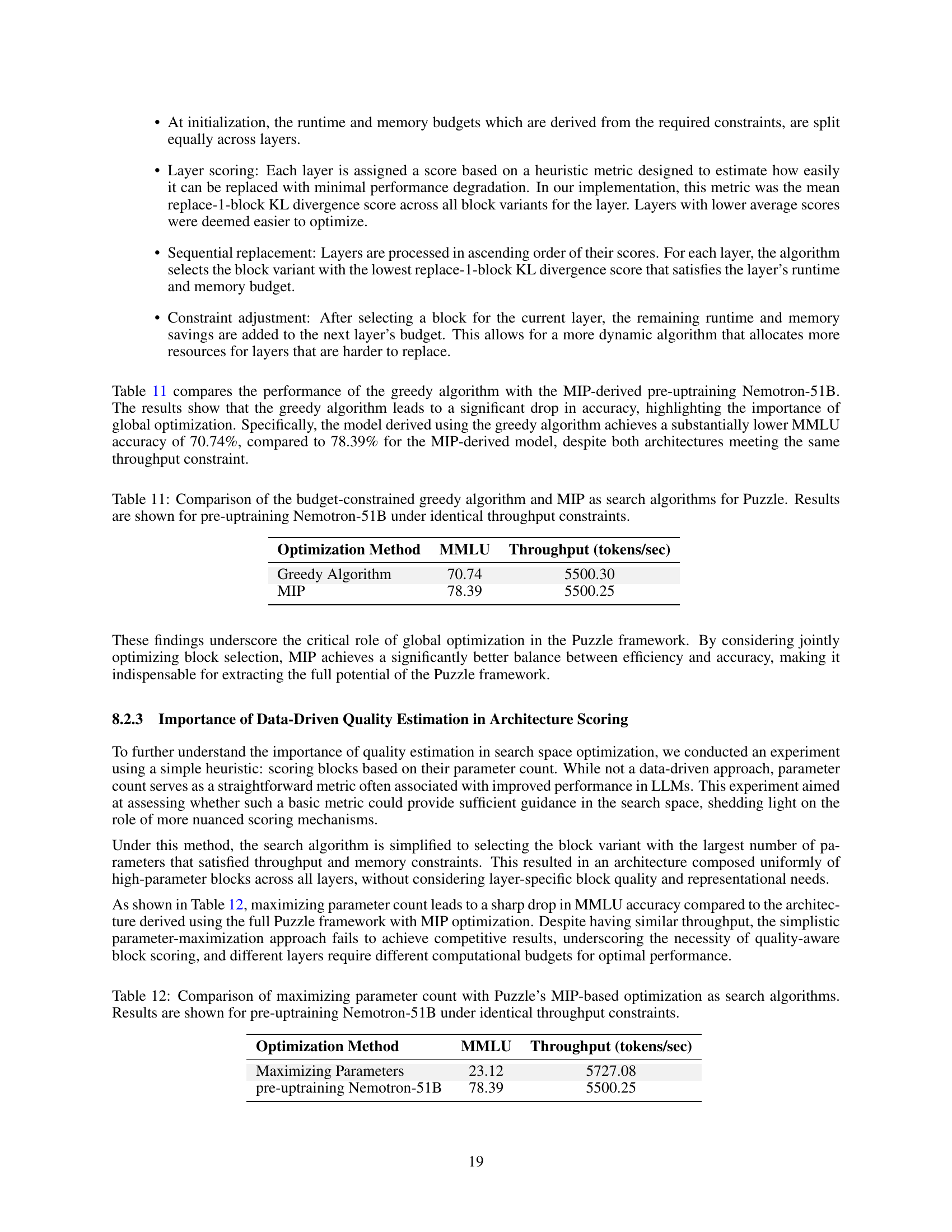

| Optimization Method | MMLU | Throughput (tokens/sec) |

|---|---|---|

| Greedy Algorithm | 70.74 | 5500.30 |

| MIP | 78.39 | 5500.25 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of two different search algorithms used in the Puzzle framework for optimizing the Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct model: a greedy algorithm and a Mixed Integer Programming (MIP) approach. Both algorithms aim to find the best architecture that meets specific throughput requirements (tokens per second) while maintaining accuracy. The table shows the MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) score and the achieved throughput (tokens/sec) for each algorithm applied to the Nemotron-51B model before the final global knowledge distillation (GKD) uptraining step. This allows for a direct comparison of the algorithms’ effectiveness in finding a suitable architecture based solely on their search capabilities.

read the caption

Table 11: Comparison of the budget-constrained greedy algorithm and MIP as search algorithms for Puzzle. Results are shown for pre-uptraining Nemotron-51B under identical throughput constraints.

| Optimization Method | MMLU | Throughput (tokens/sec) |

|---|---|---|

| Maximizing Parameters | 23.12 | 5727.08 |

| pre-uptraining Nemotron-51B | 78.39 | 5500.25 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of two different search algorithms used in the Puzzle framework for optimizing the architecture of the Nemotron-51B language model before the final uptraining stage. One algorithm uses a simple heuristic of maximizing the number of parameters, while the other utilizes Puzzle’s mixed-integer programming (MIP) approach. Both algorithms operate under identical throughput constraints to ensure a fair comparison. The table presents the MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) scores and throughput achieved by both algorithms, highlighting the superior performance of the MIP-based optimization method.

read the caption

Table 12: Comparison of maximizing parameter count with Puzzle’s MIP-based optimization as search algorithms. Results are shown for pre-uptraining Nemotron-51B under identical throughput constraints.

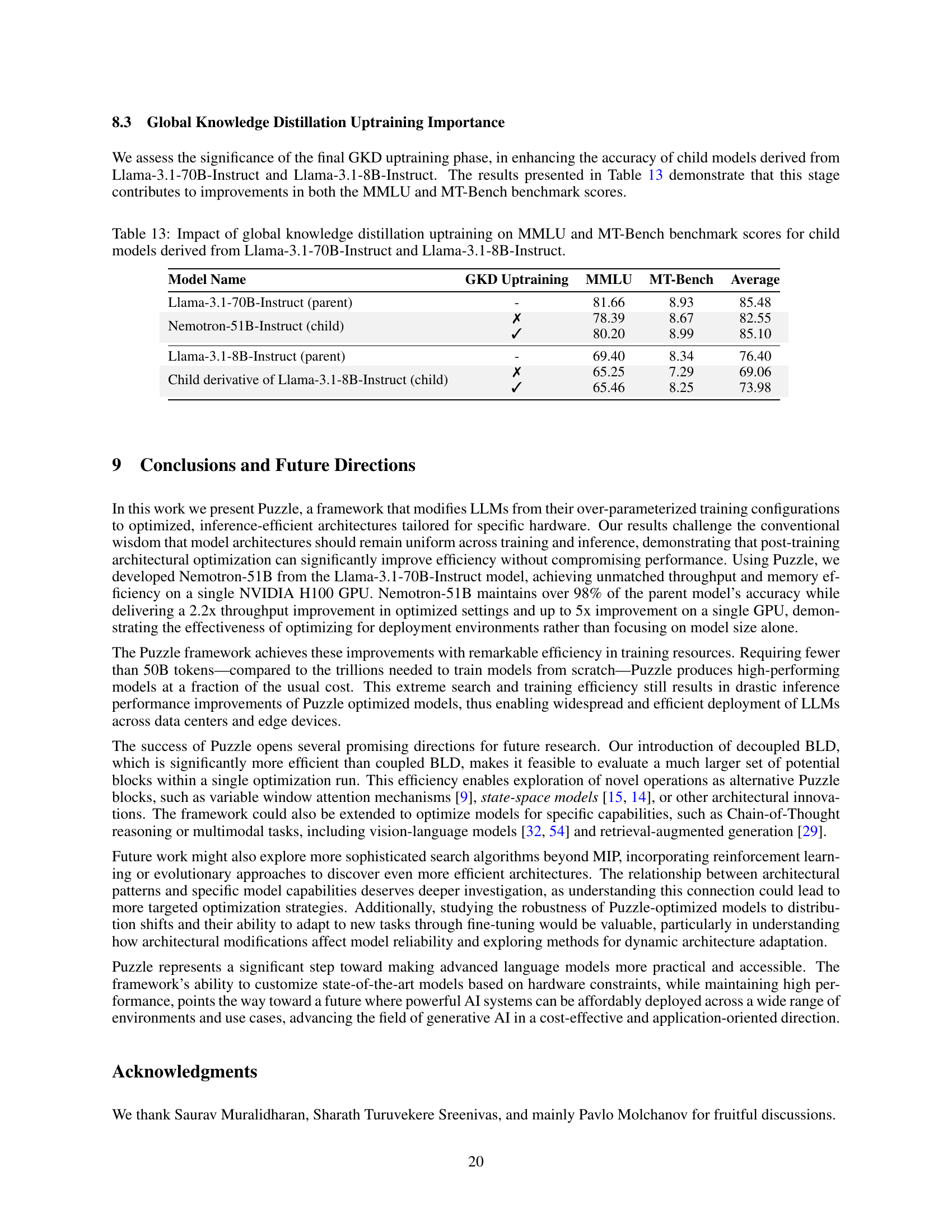

| Model Name | GKD Uptraining | MMLU | MT-Bench | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct (parent) | - | 81.66 | 8.93 | 85.48 |

| ✗ | 78.39 | 8.67 | 82.55 | |

| Nemotron-51B-Instruct (child) | ✓ | 80.20 | 8.99 | 85.10 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (parent) | - | 69.40 | 8.34 | 76.40 |

| ✗ | 65.25 | 7.29 | 69.06 | |

| Child derivative of Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (child) | ✓ | 65.46 | 8.25 | 73.98 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of global knowledge distillation (GKD) uptraining on the performance of smaller language models derived from two larger models: Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct. The table shows the MMLU and MT-Bench benchmark scores for each model with and without the GKD uptraining step, allowing for a direct comparison of performance gains achieved through this final training stage.

read the caption

Table 13: Impact of global knowledge distillation uptraining on MMLU and MT-Bench benchmark scores for child models derived from Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct.

| Context Length | qa_hotpotqa | qa_squad | common_words_extraction* | variable_tracking_1_4 | variable_tracking_2_2 | freq_words_extraction_2 | freq_words_extraction_3.5 | Average | Accuracy Preserved (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | |||||||||

| 1024 | N/A | N/A | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.40 | 99.67 | 99.81 | - |

| 2048 | N/A | 88.40 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.53 | 99.87 | 97.97 | - |

| 4096 | 67.60 | 87.40 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.87 | 99.00 | 99.80 | 93.38 | - |

| 8192 | 67.80 | 83.80 | 99.96 | 100.00 | 99.40 | 97.87 | 99.93 | 92.68 | - |

| 16384 | 63.20 | 82.00 | 98.86 | 100.00 | 96.87 | 96.67 | 99.93 | 91.08 | - |

| 32768 | 61.60 | 77.20 | 93.48 | 100.00 | 97.93 | 95.53 | 100.00 | 89.39 | - |

| 65536 | 55.4 | 72.60 | 26.16 | 99.96 | 97.93 | 94.53 | 99.87 | 78.06 | - |

| 131072 | 33.65 | 49.04 | 2.37 | 56.85 | 36.33 | 78.61 | 85.71 | 48.94 | - |

| Child | |||||||||

| 1024 | N/A | N/A | 99.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.40 | 99.53 | 99.78 | 99.9 |

| 2048 | N/A | 86.20 | 99.86 | 99.96 | 99.67 | 98.40 | 99.80 | 97.32 | 99.34 |

| 4096 | 63.40 | 85.00 | 99.92 | 100.00 | 98.93 | 97.73 | 99.87 | 92.12 | 98.65 |

| 8192 | 58.20 | 80.80 | 99.34 | 100.00 | 99.60 | 96.67 | 99.80 | 90.63 | 97.79 |

| 16384 | 53.40 | 75.60 | 93.50 | 99.72 | 96.80 | 94.73 | 99.80 | 87.65 | 96.23 |

| 32768 | 45.60 | 70.60 | 51.92 | 98.28 | 93.67 | 90.27 | 99.47 | 78.54 | 87.86 |

| 65536 | 7.4 | 15.20 | 2.28 | 3.48 | 7.87 | 36.93 | 8.67 | 11.6 | 14.86 |

| 131072 | 3.80 | 3.20 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.07 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 2.67 |

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive comparison of the performance of the Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct model (parent model) and its distilled version, Nemotron-51B (child model), across various tasks and context lengths within the RULER benchmark. It showcases how well Nemotron-51B, a smaller and more efficient model, retains the accuracy of its larger counterpart. For each task and context length, the table shows the parent model’s accuracy, the child model’s accuracy, and the percentage of the parent’s accuracy that is preserved by the child model. This allows for a direct comparison of accuracy and showcases the effectiveness of the distillation technique. The asterisk (*) indicates variations in certain metrics that depend on the specific context length used. The benchmark names are linked to their specific implementations and settings in the official Github repository.

read the caption

Table 14: Full performance comparison of the parent (Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct) and child (Nemotron-51B) models on a subset of the RULER benchmark across all context lengths. Accuracy preserved is the ratio of the child score to the parent score, expressed as a percentage. The names of the benchmarks refer to their implementation and settings used in the official github repository. *Varies depending on context length

Full paper#