↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current 3D generative models struggle with generating high-quality assets across diverse representations (meshes, point clouds, radiance fields, etc.) and lack flexible editing capabilities. Existing methods often prioritize either geometry or appearance, hindering the creation of versatile, high-quality 3D content. Additionally, many models require complex pre-processing or are computationally expensive.

This paper introduces a novel method that addresses these issues. It uses a unified latent representation called Structured LATents (SLAT), which integrates a sparsely populated 3D grid with dense visual features to capture both structure and appearance. The researchers trained a 2-billion parameter model using rectified flow transformers to generate SLAT representations and achieved high-quality 3D assets in various formats. The model demonstrated superior performance in flexible editing and outperformed existing models in multiple evaluations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in 3D generation due to its introduction of SLAT, a novel unified latent representation enabling versatile and high-quality 3D asset creation. Its flexible editing capabilities and superior performance over existing methods make it highly relevant to current AIGC trends and open new avenues for 3D modeling research, especially in areas demanding versatile output formats and high-quality results. The availability of code, models, and data further enhances its impact.

Visual Insights#

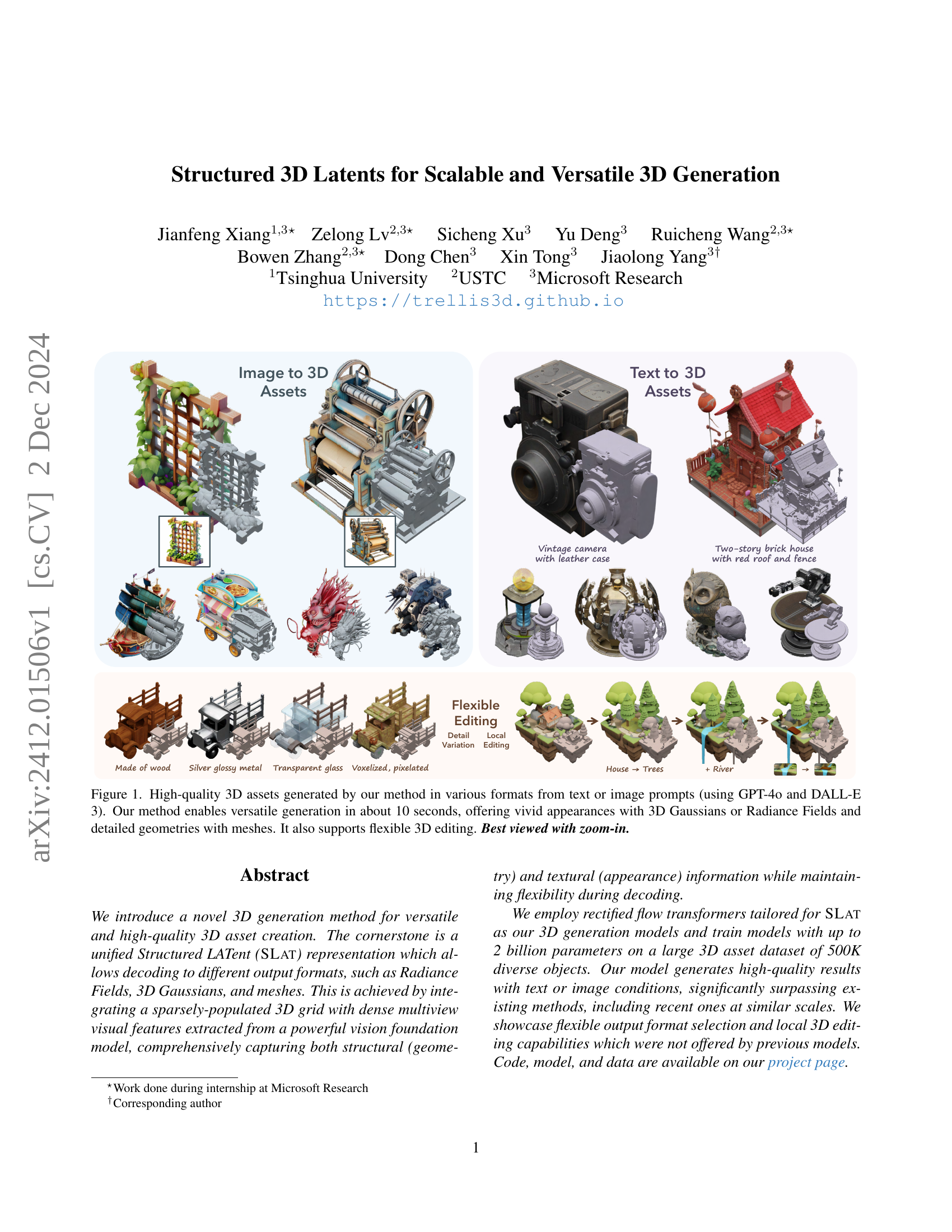

🔼 This figure showcases the high-quality 3D models generated using the novel method presented in the paper. The models are created from both text and image prompts, utilizing the powerful language models GPT-4 and DALL-E 3. The versatility of the approach is highlighted, demonstrating the generation of assets in various formats, including detailed meshes, and visually appealing representations using 3D Gaussians and Radiance Fields. The speed of generation (around 10 seconds) is also emphasized, along with the capability for flexible post-generation editing of the 3D assets.

read the caption

Figure 1: High-quality 3D assets generated by our method in various formats from text or image prompts (using GPT-4o and DALL-E 3). Our method enables versatile generation in about 10 seconds, offering vivid appearances with 3D Gaussians or Radiance Fields and detailed geometries with meshes. It also supports flexible 3D editing. Best viewed with zoom-in.

| Method | Appearance PSNR ↑ | Appearance LPIPS ↓ | Geometry CD ↓ | Geometry F-score ↑ | Geometry PSNR-N ↑ | Geometry LPIPS-N ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN3Diff | 26.44 | 0.076 | 0.0299 | 0.9649 | 27.10 | 0.094 |

| 3DTopia-XL | 25.34† | 0.074† | 0.0128 | 0.9939 | 31.87 | 0.080 |

| CLAY | – | – | 0.0124 | 0.9976 | 35.35 | 0.035 |

| Ours | 32.74/32.19‡ | 0.025/0.029‡ | 0.0083 | 0.9999 | 36.11 | 0.024 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the reconstruction fidelity achieved by different latent representations, including the proposed Structured Latent (SLAT) method and existing alternatives. The comparison is done in terms of both appearance and geometry, evaluating various metrics such as PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity), CD (Chamfer Distance), and F-score. The appearance fidelity is assessed using albedo color for some methods and radiance fields for others, as indicated by the symbols († and ‡). This detailed analysis demonstrates the superior performance of SLAT in accurately reconstructing high-quality 3D assets compared to other techniques.

read the caption

Table 1: Reconstruction fidelity of different latent representations. (†: evaluated using albedo color; ‡: evaluated via Radiance Fields)

In-depth insights#

Unified 3D Latent#

A unified 3D latent representation is crucial for achieving scalable and versatile 3D content generation. The core idea revolves around creating a single latent space capable of encoding diverse 3D asset characteristics, enabling decoding into multiple output formats like meshes, radiance fields, and 3D Gaussians. This unification simplifies the generation process, avoiding format-specific encoders and decoders. A successful unified 3D latent representation needs to effectively capture both geometric structure and visual appearance details, often achieved by integrating sparse 3D structures with rich visual features from powerful vision foundation models. Sparsity in the 3D structure is key for efficiency, focusing computational resources on relevant information, while the integrated visual features ensure high fidelity in the generated assets. Flexible editing capabilities are enhanced through locality inherent in the unified representation, allowing for targeted modifications. Overall, the unified 3D latent approach promises a paradigm shift towards standardized 3D generative modeling, offering improved efficiency and versatility.

Rectified Flow 3D#

Rectified flow models offer a compelling alternative to diffusion models for 3D generation. Their inherent ability to directly model the probability distribution of 3D data, rather than iteratively denoising, could lead to more efficient training and potentially higher-quality results. The use of rectified flows in a two-stage pipeline, first for structure generation and then for detailed latent encoding, is an innovative approach. However, challenges remain. The success of this method hinges on the effectiveness of the transformer architectures and the ability to seamlessly integrate the rectified flow framework with sparse 3D representations. Careful consideration of training procedures, including regularization techniques, is necessary to overcome the inherent complexities of high-dimensional 3D data. Future research should explore further refinements of the rectified flow architecture, including improvements in efficiency and scalability to even larger datasets. The potential to directly handle high-resolution 3D data without the computational constraints of diffusion is a significant advantage that warrants further investigation and may prove transformative to the field of 3D content generation.

High-Quality Assets#

The concept of “High-Quality Assets” in 3D generation is multifaceted, encompassing both geometric accuracy and visual fidelity. Geometric accuracy refers to the precision and realism of an asset’s shape, free from distortions or artifacts. Visual fidelity considers the asset’s texture, materials, lighting, and overall appearance, aiming for photorealism or a convincing stylistic rendering. Achieving high-quality assets necessitates a robust 3D generation model that can accurately represent complex shapes and appearances, handle diverse material properties effectively, and produce outputs in various desired formats like meshes, radiance fields, or 3D Gaussians. The challenge lies in balancing computational cost with the level of detail required. A successful model should be versatile enough to produce outputs at different scales, while also supporting flexible editing, ensuring that the generated assets not only look visually appealing but also possess realistic geometry that can be readily integrated into downstream applications. Ultimately, the pursuit of high-quality assets drives the evolution of 3D generative techniques, pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved computationally.

Flexible 3D Editing#

The concept of “Flexible 3D Editing,” while not explicitly a heading in the provided text, is a crucial outcome of the research on structured latent representations for 3D generation. The paper’s method allows for seamless manipulation of 3D assets due to the inherent locality of the structured latent representation. This locality allows modification in a specific region without affecting other parts, enabling intuitive and precise edits. The flexibility extends to various output formats (meshes, radiance fields, and 3D Gaussians), meaning edits made in one format can be seamlessly transferred to others. This unifying representation allows for the development of new editing tools, moving beyond simple transformations and towards localized modifications of shape, texture, and appearance, all within a unified framework. The capability for fitting-free training further enhances this flexibility by eliminating the need for pre-processing and simplifying the integration of diverse 3D asset types for editing.

Future of 3D Gen#

The future of 3D generation hinges on addressing current limitations and exploring new avenues. Improving efficiency is paramount; current methods are computationally expensive, hindering broader accessibility. Enhanced resolution and detail are crucial, pushing beyond current capabilities to achieve photorealism. Greater control and customization will empower users, enabling fine-grained manipulation and personalized asset creation. This requires advancements in latent space representations, incorporating both geometry and appearance information seamlessly. Integration with other AI tools, such as text-to-image and diffusion models, will drive further innovation and enable more creative and intuitive workflows. The development of more robust and versatile training datasets, capturing the complexity and diversity of real-world objects, is essential for improving the quality of generated assets. Ultimately, the goal is to make 3D content creation as effortless and intuitive as 2D generation, democratizing the production of high-quality 3D assets for various applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

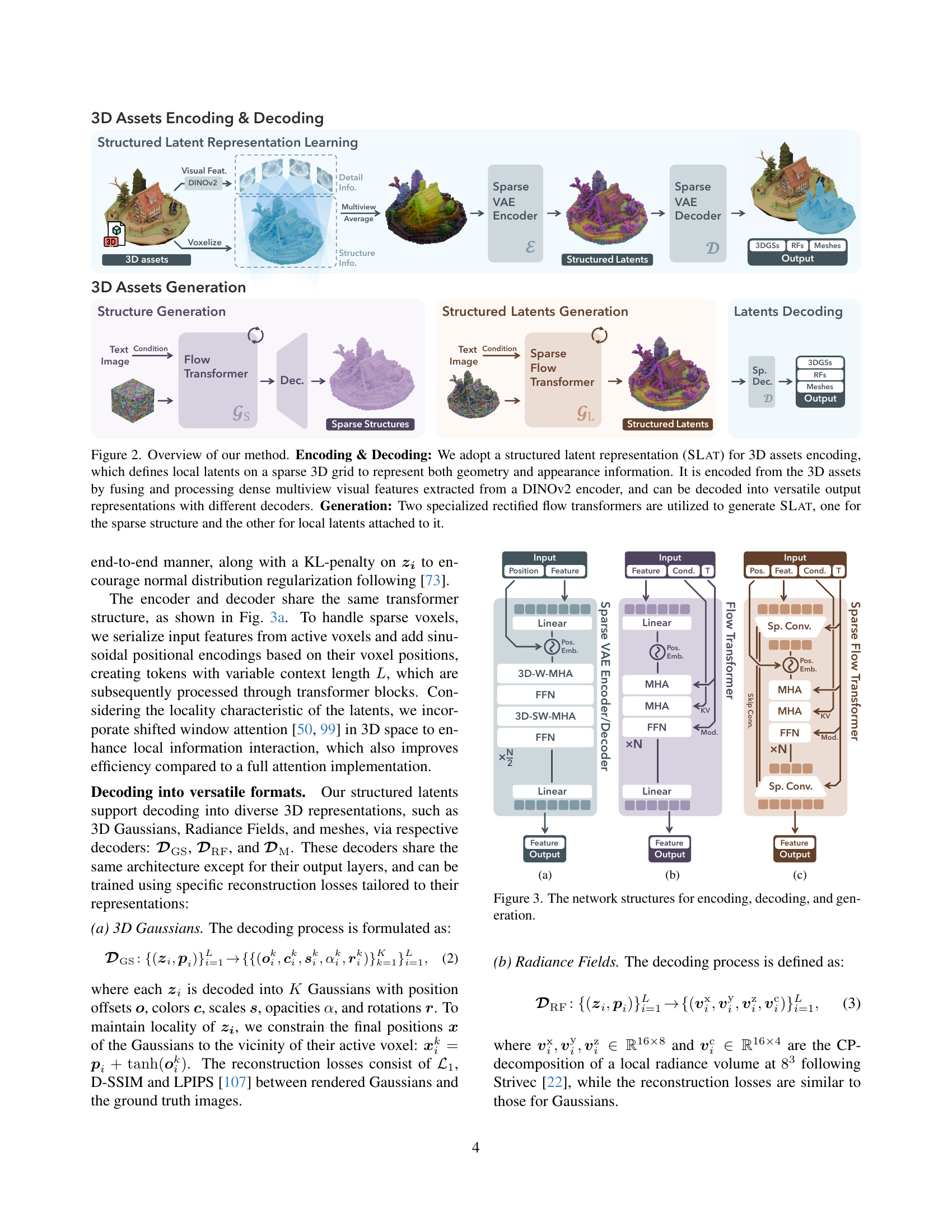

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed 3D generation method. The process begins with encoding, where a 3D asset is converted into a structured latent representation (SLAT). SLAT uses a sparse 3D grid with local latents representing geometry and appearance details. Dense multiview visual features, extracted from a DINOv2 encoder, are fused into these local latents. The SLAT is then decoded into various output formats (Radiance Fields, 3D Gaussians, and meshes) using specialized decoders. The generation process itself uses two rectified flow transformers, one for generating the sparse structure of the SLAT and another for generating the local latents associated with the sparse structure.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of our method. Encoding & Decoding: We adopt a structured latent representation (SLat) for 3D assets encoding, which defines local latents on a sparse 3D grid to represent both geometry and appearance information. It is encoded from the 3D assets by fusing and processing dense multiview visual features extracted from a DINOv2 encoder, and can be decoded into versatile output representations with different decoders. Generation: Two specialized rectified flow transformers are utilized to generate SLat, one for the sparse structure and the other for local latents attached to it.

🔼 The figure shows the overview of the proposed method for 3D asset generation. The method uses a structured latent representation (SLAT) that incorporates sparse 3D structures with dense multiview visual features to enable decoding to various output formats (e.g., radiance fields, 3D Gaussians, meshes). The generation process involves two stages: sparse structure generation and structured latents generation, both using rectified flow transformers. The SLAT enables flexible 3D editing capabilities.

read the caption

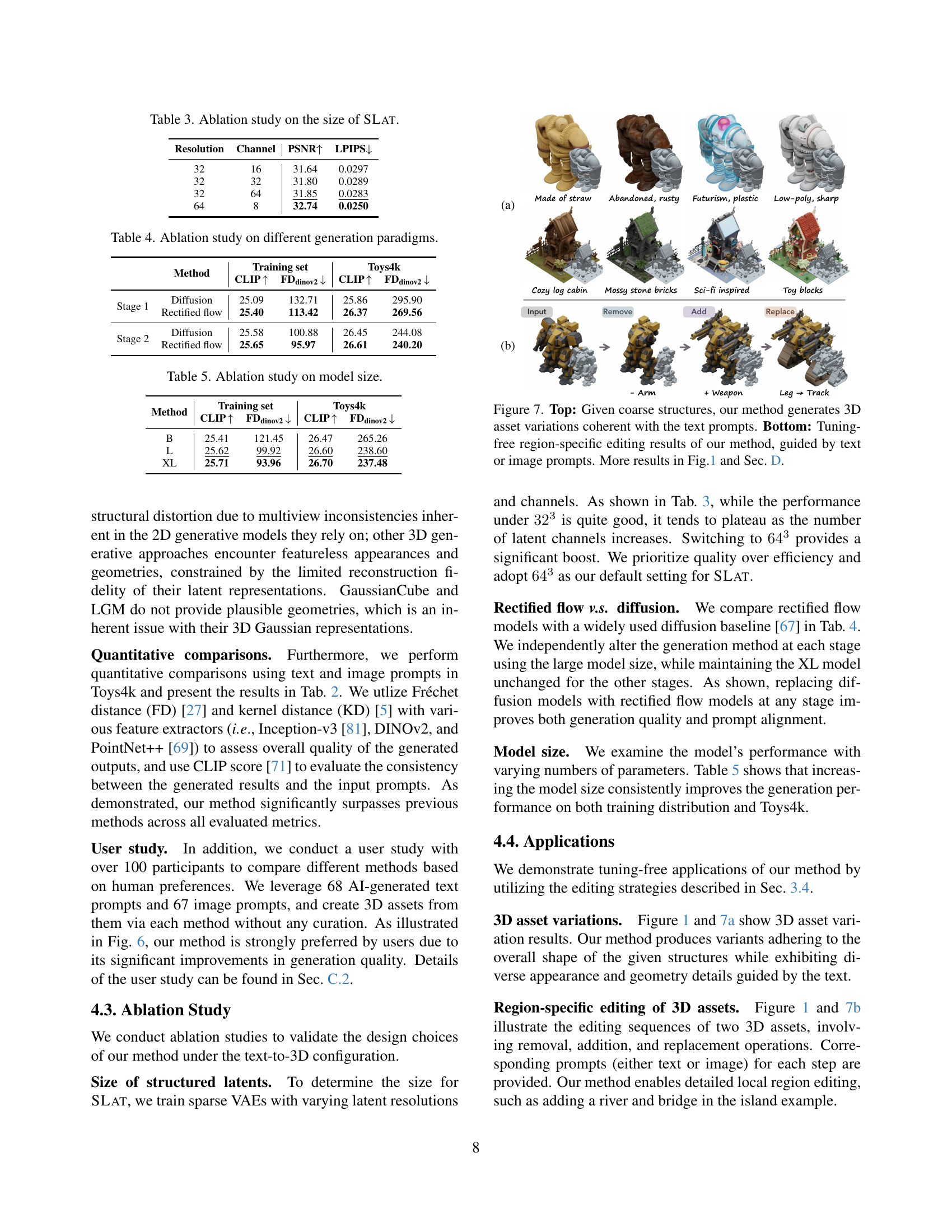

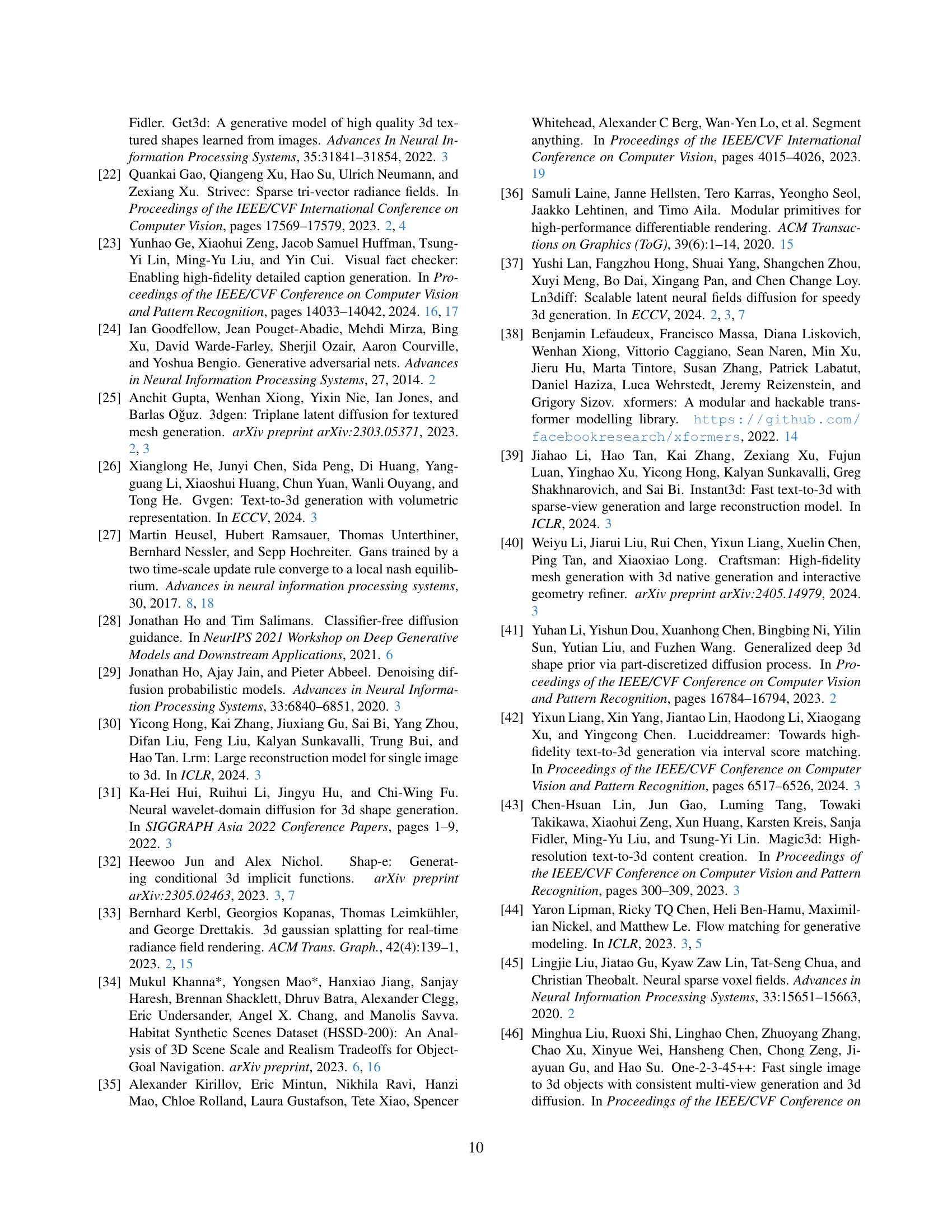

(a)

🔼 The figure shows examples of region-specific editing using the proposed method. It demonstrates the ability to make local changes to a 3D model, such as adding or removing features or replacing parts, while maintaining the overall coherence and quality of the model. The top row displays the original models, and the subsequent rows present the result of various modifications guided by text prompts, demonstrating the method’s versatility and flexibility in 3D editing.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 This figure shows the network architectures for encoding, decoding, and generation. (a) illustrates the sparse VAE encoder/decoder used for structured latent representation learning, employing a transformer architecture with 3D shifted window multi-head attention and feed-forward networks (FFNs) for processing sparse voxel features. (b) shows the rectified flow transformer (Gs) for sparse structure generation, which uses multi-head self-attention and cross-attention layers to process text or image conditions and generate a dense binary representation of the sparse structure. (c) displays the rectified flow transformer (GL) used for generating structured latents, again utilizing multi-head self-attention and cross-attention layers and incorporating sparse convolution downsampling/upsampling blocks to efficiently handle the sparse structure and generate high-resolution local latent vectors.

read the caption

(c)

🔼 This figure details the network architectures used in the paper’s proposed 3D generation method. It shows three main network diagrams: (a) Sparse VAE Encoder/Decoder, which maps between 3D asset visual features and structured latent representations; (b) Structure Generation Flow Transformer, responsible for creating the sparse 3D structure of the latent representation; and (c) Sparse Flow Transformer, which generates the detailed latent values within the sparse structure, conditioned on text or image prompts. Each diagram illustrates the various layers and components including linear layers, Multi-Head Attention (MHA), Feed-Forward Networks (FFN), sparse convolutions, and positional embeddings. The diagrams visually represent the flow of information through the networks during encoding, decoding, and generation processes.

read the caption

Figure 3: The network structures for encoding, decoding, and generation.

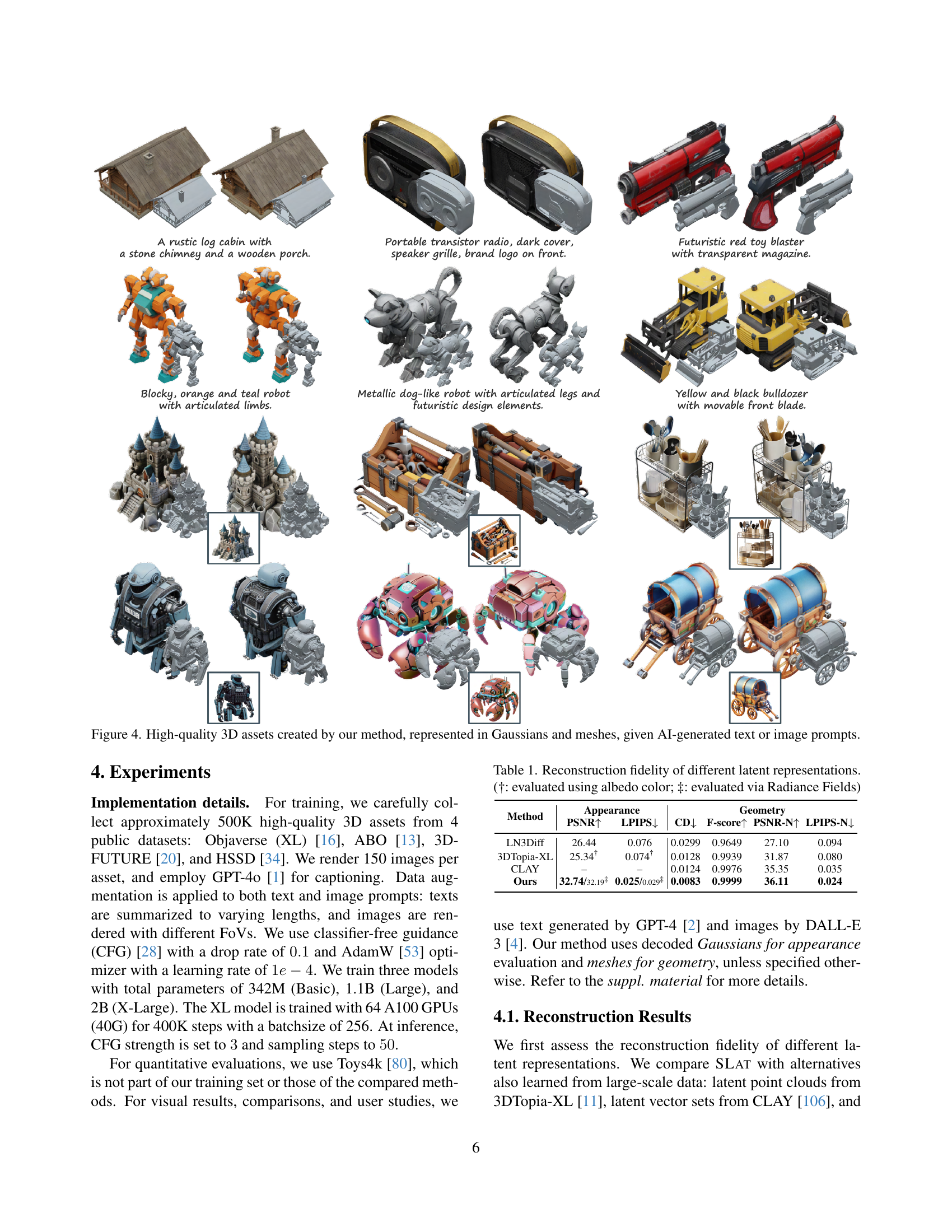

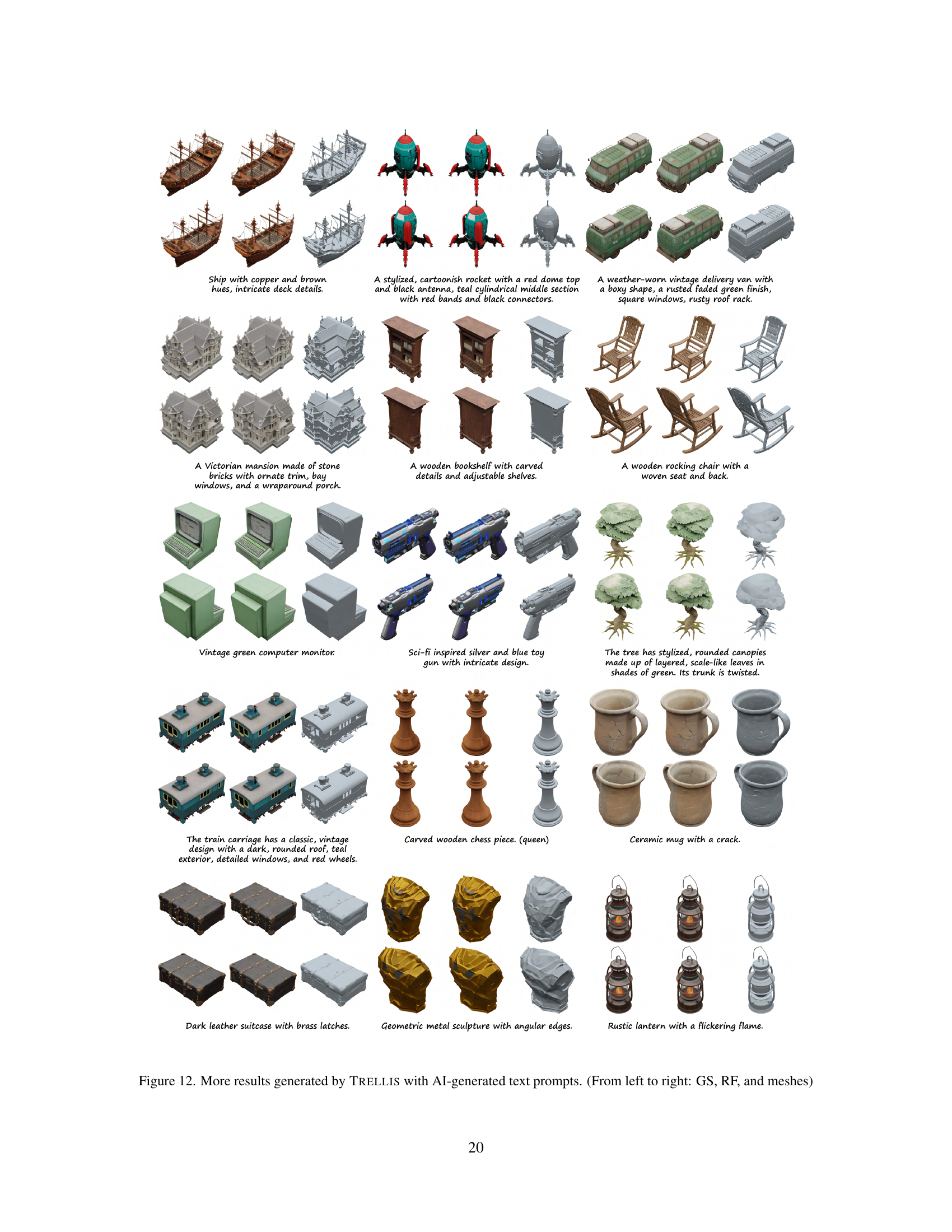

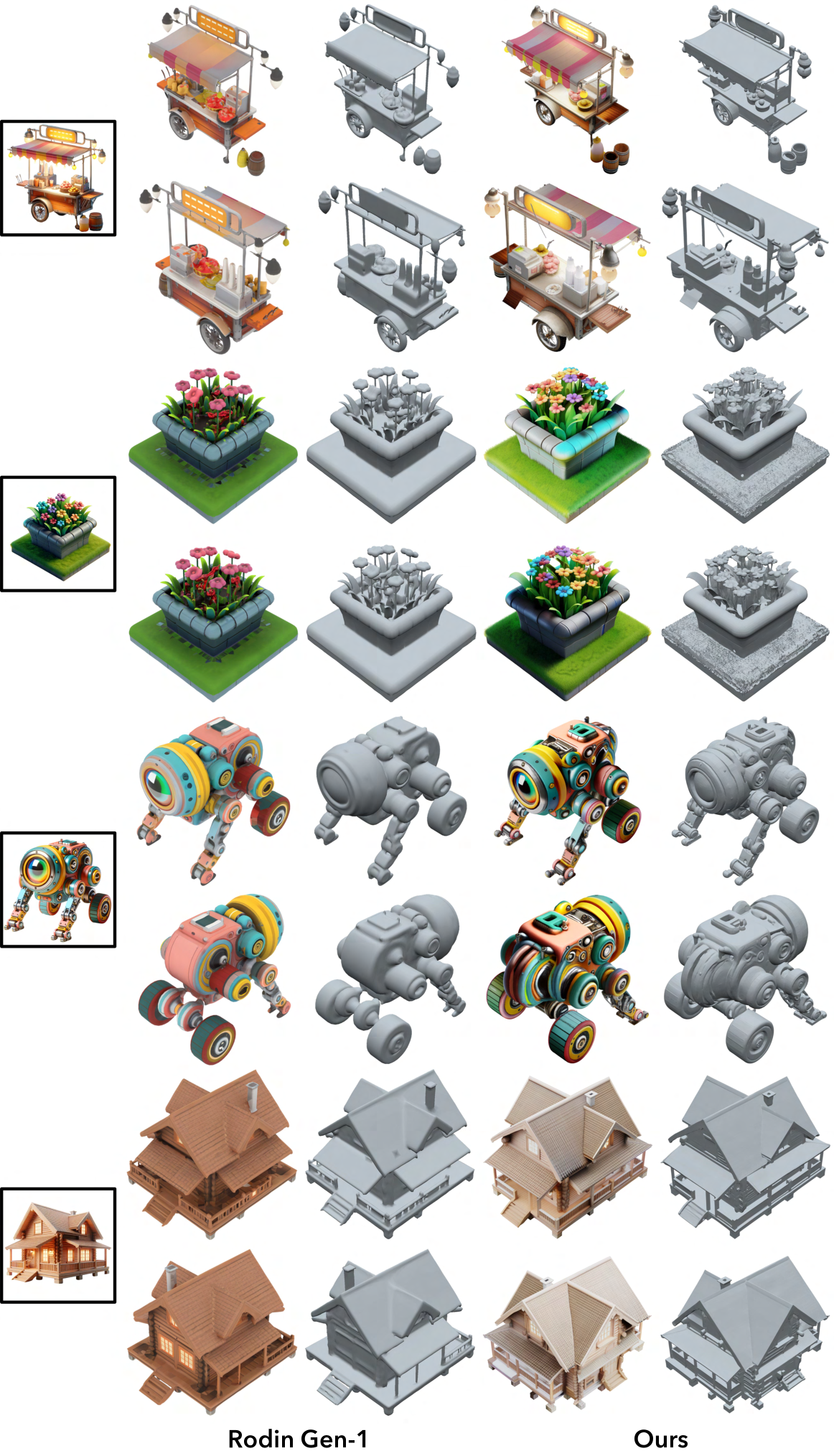

🔼 This figure showcases the high-quality 3D models generated using the method described in the paper. The models are rendered in two different formats: 3D Gaussians and meshes. The input to the model was AI-generated text and image prompts, demonstrating the system’s versatility and capability to produce detailed, realistic 3D assets from various input types.

read the caption

Figure 4: High-quality 3D assets created by our method, represented in Gaussians and meshes, given AI-generated text or image prompts.

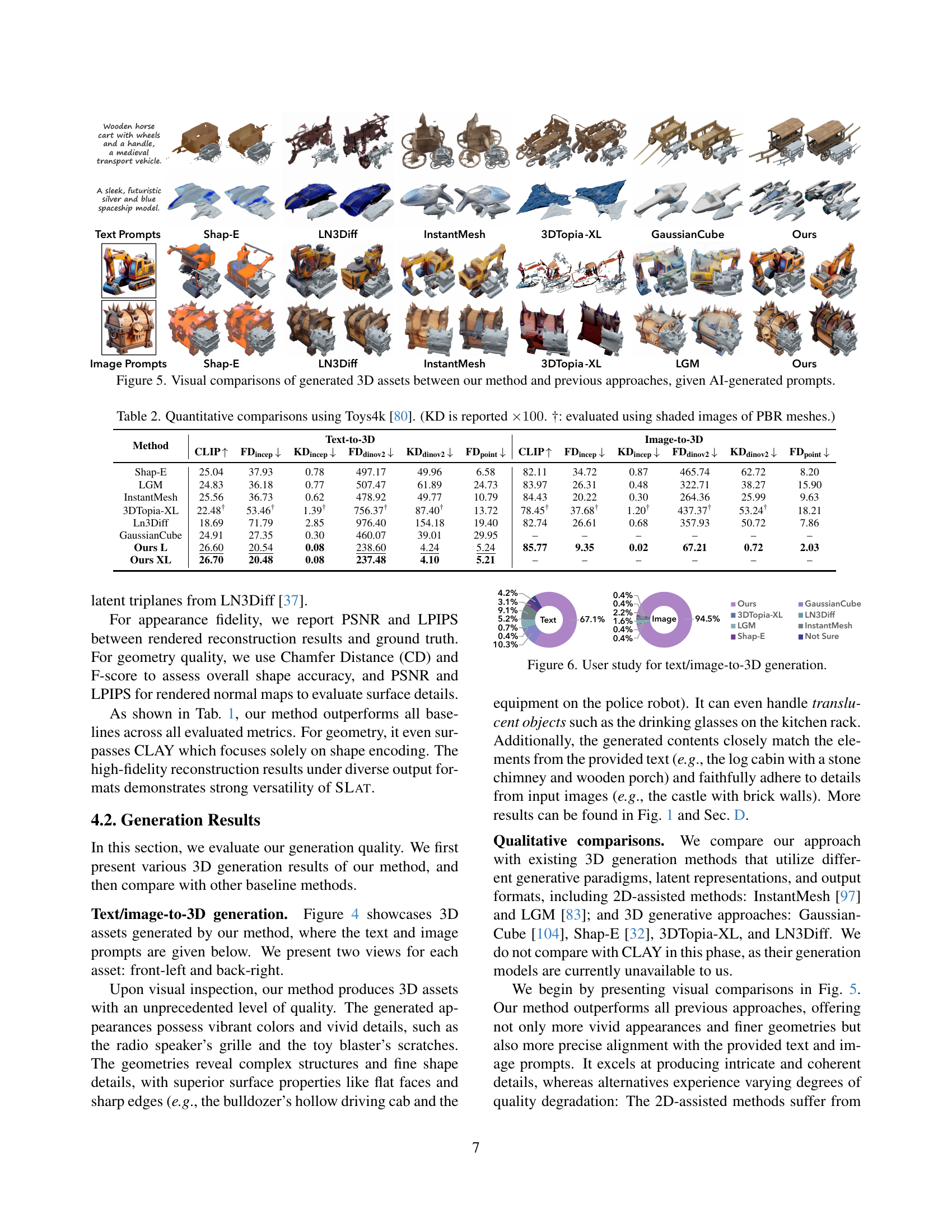

🔼 Figure 5 presents a visual comparison of 3D models generated by different methods. The models were generated from AI-generated text and image prompts. The figure allows for a direct visual assessment of the relative quality and detail of the 3D models produced by the proposed method compared to those produced by several existing state-of-the-art 3D generation methods. Each row shows the same object generated by a different method, demonstrating the differences in realism, detail and overall quality of the generation. This is valuable for quickly understanding the improvements achieved by the new method.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visual comparisons of generated 3D assets between our method and previous approaches, given AI-generated prompts.

🔼 The figure shows the results of a user study comparing different text-to-3D and image-to-3D generation methods. The study measured user preferences for the quality of generated 3D assets. Participants were shown pairs of assets and asked to select the best one based on a given prompt (text or image). The results visually represent the percentage of times each method was selected as the best.

read the caption

Figure 6: User study for text/image-to-3D generation.

🔼 This figure shows the overall architecture of the proposed method, which uses a structured latent representation (SLAT) for 3D asset encoding and decoding. The encoding process involves converting the 3D asset into voxels, aggregating multiview features from a powerful vision foundation model, and encoding these features into structured latents using a sparse VAE. The decoding process involves using separate decoders to map the structured latents into different output formats (Radiance Fields, 3D Gaussians, and meshes). The generation process uses two rectified flow transformers: one for generating the sparse structure of the SLAT and another for generating the local latents, conditioned on text or image prompts.

read the caption

(a)

🔼 The figure shows examples of tuning-free region-specific 3D editing using the method presented in the paper. The editing is guided by text prompts. The images illustrate how various modifications can be made to a 3D asset, such as removing, adding, or replacing parts of the asset. The results show the model’s ability to generate coherent local changes while maintaining the overall consistency of the model.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 This figure demonstrates two key capabilities of the proposed 3D generation method. The top row showcases the generation of multiple 3D asset variations from a single coarse structure, highlighting the method’s ability to produce diverse outputs while maintaining coherence with textual descriptions. Each variation uses the same basic 3D structure but differs in details guided by specific text prompts. The bottom row shows examples of region-specific editing. This feature allows for non-destructive modifications to selected parts of a generated 3D object. The user can specify changes through textual or image prompts, resulting in seamless integration of the edits into the original model. Further examples of both asset variation and editing are available in Figure 1 and Section D of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 7: Top: Given coarse structures, our method generates 3D asset variations coherent with the text prompts. Bottom: Tuning-free region-specific editing results of our method, guided by text or image prompts. More results in Fig.1 and Sec. D.

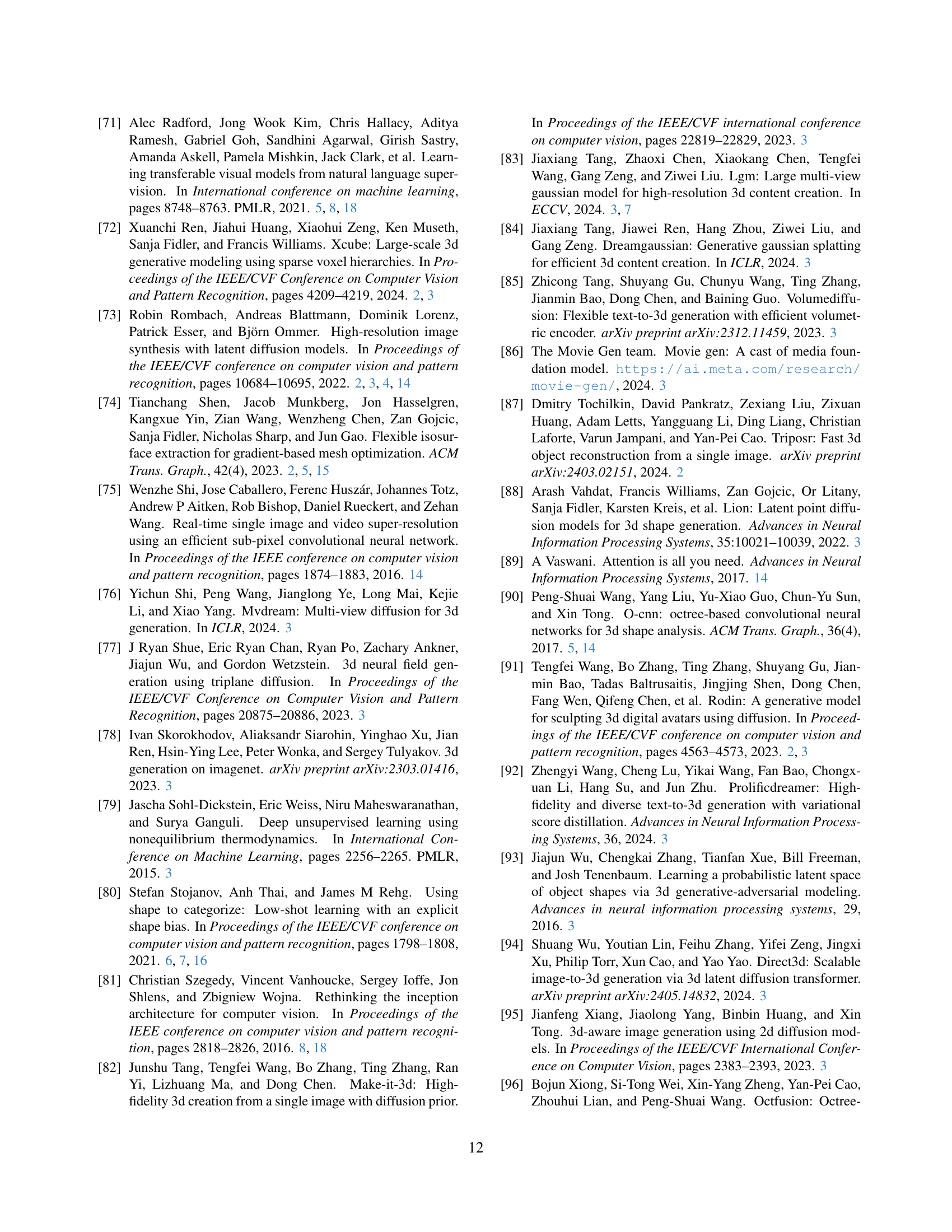

🔼 This figure displays the distribution of aesthetic scores for each dataset used in the training process. The histograms illustrate the frequency of different aesthetic scores (presumably ranging from low to high), providing a visual representation of the overall quality distribution in each of the datasets: Objaverse-XL (from Sketchfab and Github), ABO, 3D-FUTURE, and HSSD. The x-axis represents the aesthetic score, and the y-axis represents the frequency or density of assets with that particular score. The figure helps to show the relative quality of the different datasets and highlights the threshold used for data curation purposes (where aesthetic scores below a certain threshold were filtered out).

read the caption

Figure 8: Distribution of aesthetic scores in each dataset.

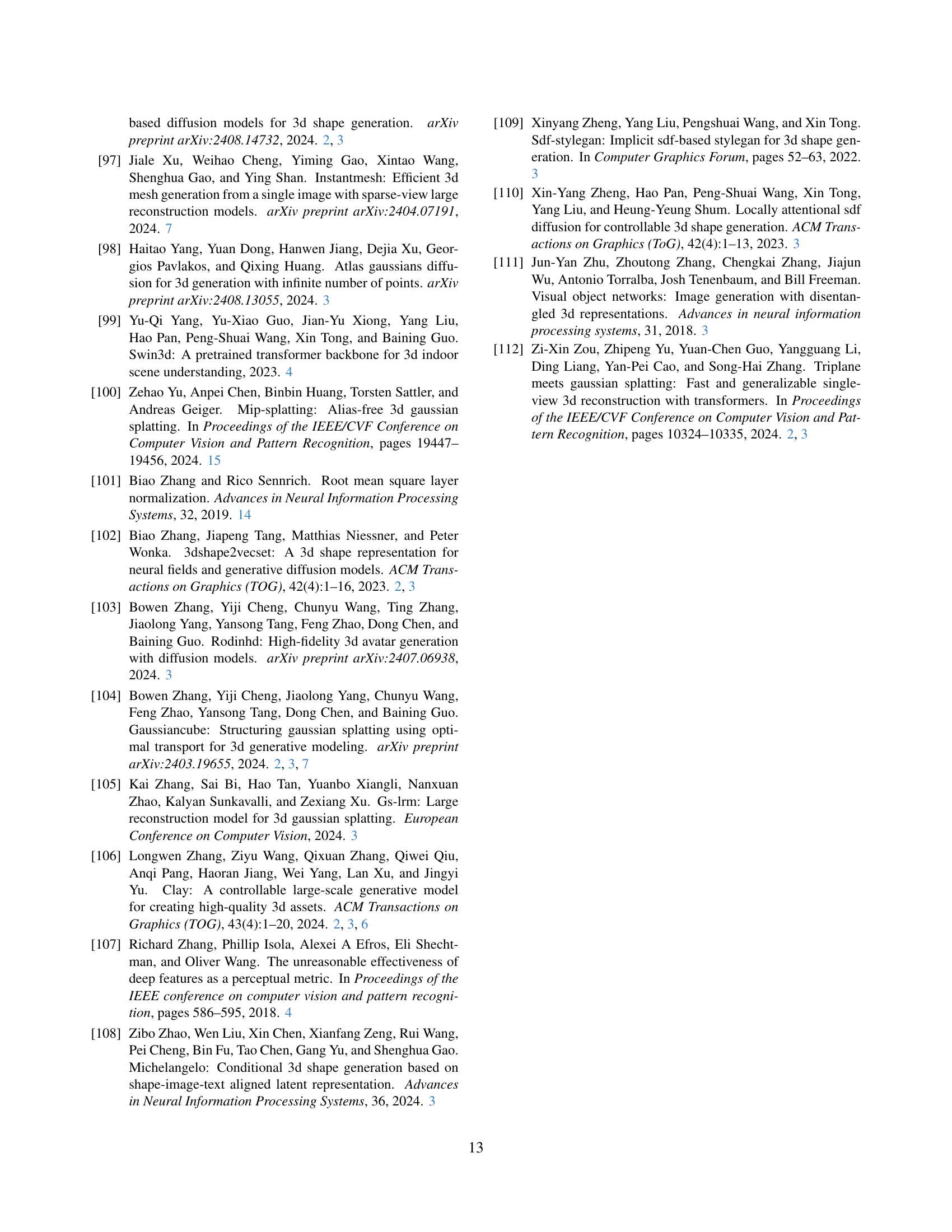

🔼 Figure 9 shows examples of 3D assets from the Objaverse-XL dataset, a large-scale collection of 3D models. Each asset is accompanied by its aesthetic score, which is a numerical value representing how visually appealing the model is. This figure illustrates the quality of 3D assets in the Objaverse-XL dataset, showing various levels of aesthetic scores and the corresponding visual quality. Higher aesthetic scores generally represent more visually appealing models.

read the caption

Figure 9: 3D asset examples from Objaverse-XL with their corresponding aesthetic scores.

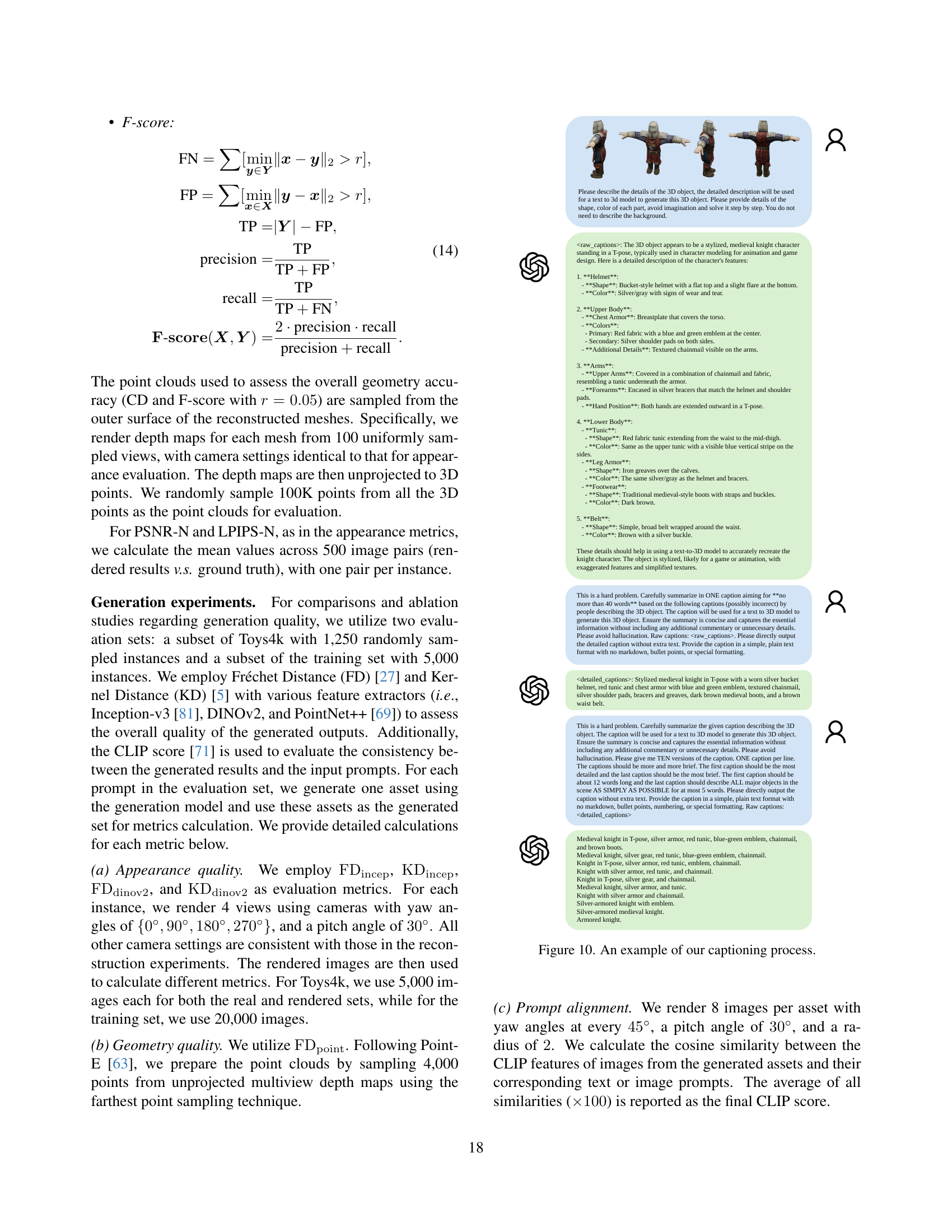

🔼 This figure illustrates the two-stage captioning process used in the paper to generate high-quality text descriptions for 3D assets. First, a detailed, raw caption is produced using GPT-40, providing a comprehensive description of the 3D object’s features. This raw caption is then summarized by GPT-40 into a concise, refined caption of no more than 40 words, suitable for use as a prompt with a text-to-3D model. The example shows the raw caption, followed by ten progressively shorter versions of the summary, demonstrating the refinement process from a highly detailed description to a short, impactful prompt.

read the caption

Figure 10: An example of our captioning process.

🔼 This figure displays the user interface used in the user study. Participants were shown side-by-side comparisons of 3D assets generated using different methods. Each trial presented a text prompt or reference image and several rotating videos of candidate 3D assets. Users selected the asset that best matched the reference image.

read the caption

Figure 11: User interface used in our user study.

More on tables

| Method | CLIP ↑ | FDincep ↓ | KDincep ↓ | FDdinov2 ↓ | KDdinov2 ↓ | FDpoint ↓ | CLIP ↑ | FDincep ↓ | KDincep ↓ | FDdinov2 ↓ | KDdinov2 ↓ | FDpoint ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shap-E | 25.04 | 37.93 | 0.78 | 497.17 | 49.96 | 6.58 | 82.11 | 34.72 | 0.87 | 465.74 | 62.72 | 8.20 |

| LGM | 24.83 | 36.18 | 0.77 | 507.47 | 61.89 | 24.73 | 83.97 | 26.31 | 0.48 | 322.71 | 38.27 | 15.90 |

| InstantMesh | 25.56 | 36.73 | 0.62 | 478.92 | 49.77 | 10.79 | 84.43 | 20.22 | 0.30 | 264.36 | 25.99 | 9.63 |

| 3DTopia-XL | 22.48† | 53.46† | 1.39† | 756.37† | 87.40† | 13.72 | 78.45† | 37.68† | 1.20† | 437.37† | 53.24† | 18.21 |

| Ln3Diff | 18.69 | 71.79 | 2.85 | 976.40 | 154.18 | 19.40 | 82.74 | 26.61 | 0.68 | 357.93 | 50.72 | 7.86 |

| GaussianCube | 24.91 | 27.35 | 0.30 | 460.07 | 39.01 | 29.95 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ours L | 26.60 | 20.54 | 0.08 | 238.60 | 4.24 | 5.24 | 85.77 | 9.35 | 0.02 | 67.21 | 0.72 | 2.03 |

| Ours XL | 26.70 | 20.48 | 0.08 | 237.48 | 4.10 | 5.21 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

🔼 Table 2 presents a quantitative comparison of different 3D generation methods using the Toys4k dataset. It compares performance on both text-to-3D and image-to-3D tasks. Metrics include CLIP score (a measure of alignment between generated assets and input text/image prompts), Fréchet Inception Distance (FDincep), Kernel Inception Distance (KDincep) (both multiplied by 100), Fréchet DINOv2 Distance (FDdinov2), Kernel DINOv2 Distance (KDdinov2) (both multiplied by 100), and Fréchet Point Distance (FDpoint). The ‘†’ symbol indicates that the PSNR and LPIPS values were calculated using shaded images of Physically Based Rendering (PBR) meshes for those specific metrics. This allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of both the appearance and geometry quality of the generated 3D models.

read the caption

Table 2: Quantitative comparisons using Toys4k [80]. (KD is reported ×100absent100\times 100× 100. †: evaluated using shaded images of PBR meshes.)

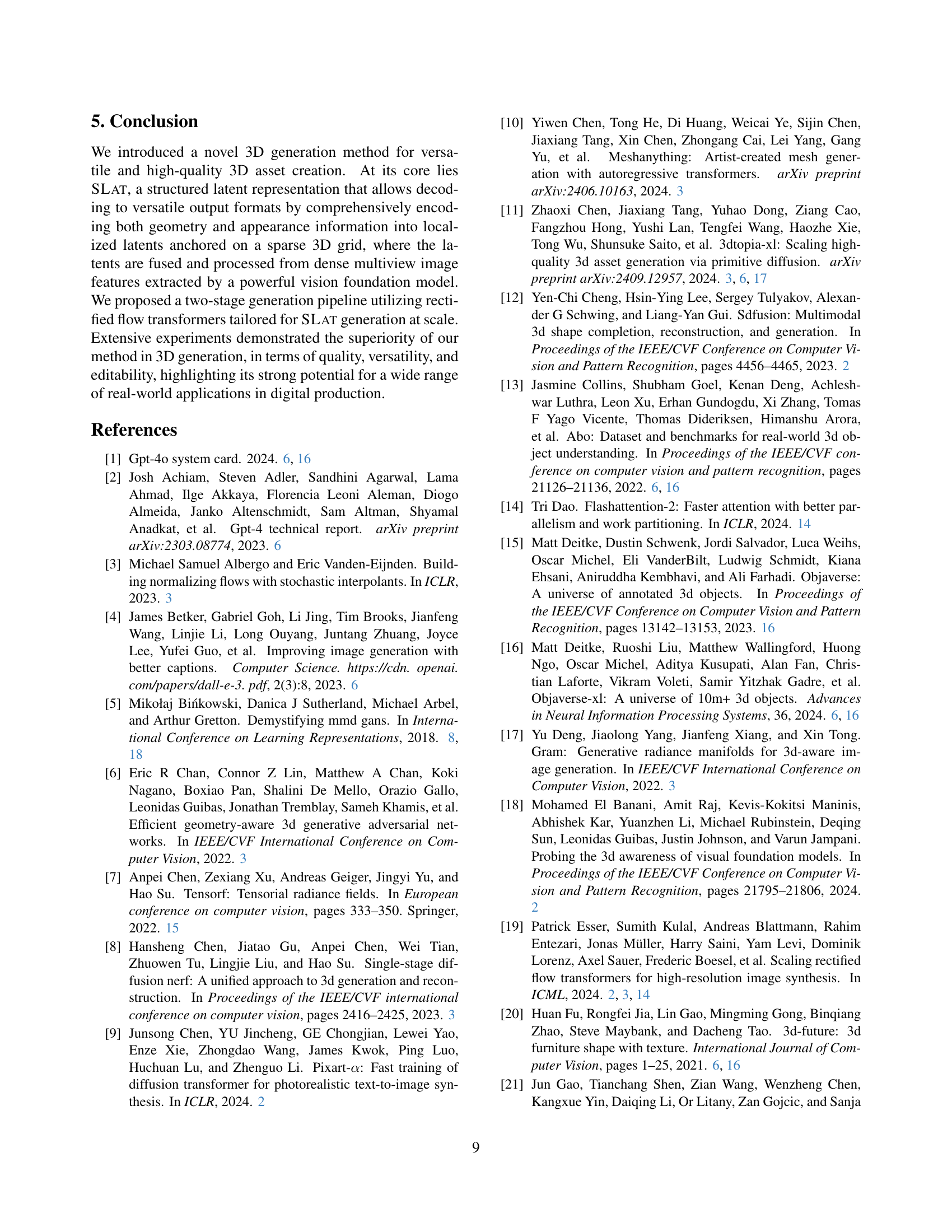

| Resolution | Channel | PSNR ↑ | LPIPS ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | 16 | 31.64 | 0.0297 |

| 32 | 32 | 31.80 | 0.0289 |

| 32 | 64 | 31.85 | 0.0283 |

| 64 | 8 | 32.74 | 0.0250 |

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of different SLAT (Structured Latent) sizes on the model’s performance. It varies the resolution and number of channels within the SLAT representation and assesses the resulting PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity) scores. Higher PSNR indicates better reconstruction quality, while lower LPIPS suggests improved perceptual similarity to the ground truth. The results show how changes to SLAT size affect the balance between reconstruction quality and perceptual fidelity.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study on the size of SLat.

| Method | Training set CLIP↑ | Training set FDdinov2↓ | Toys4k CLIP↑ | Toys4k FDdinov2↓ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Diffusion | 25.09 | 132.71 | 25.86 | 295.90 |

| Rectified flow | 25.40 | 113.42 | 26.37 | 269.56 | |

| Stage 2 | Diffusion | 25.58 | 100.88 | 26.45 | 244.08 |

| Rectified flow | 25.65 | 95.97 | 26.61 | 240.20 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing different generation paradigms. Specifically, it investigates the impact of using diffusion models versus rectified flow models at each stage of the two-stage generation process (structure generation and latent generation). The study is performed using the Toys4k dataset, assessing the performance using the CLIP score and Fréchet Inception Distance (FD). The table allows readers to analyze the effectiveness of each paradigm combination (diffusion or rectified flow for each stage) in generating high-quality 3D assets.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study on different generation paradigms.

| Method | Training set CLIP↑ | Training set FDdinov2↓ | Toys4k CLIP↑ | Toys4k FDdinov2↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 25.41 | 121.45 | 26.47 | 265.26 |

| L | 25.62 | 99.92 | 26.60 | 238.60 |

| XL | 25.71 | 93.96 | 26.70 | 237.48 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the effect of model size on the performance of the proposed 3D generation method. It shows how different model sizes (Basic, Large, and X-Large), each with varying numbers of parameters, impact the quality of 3D asset generation, as measured by CLIP score and Fréchet Inception Distance (FD-Inception). The performance is assessed using the Toys4k dataset, which is held-out from the training process, allowing for a fair evaluation of generalization ability.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study on model size.

| Network | #Layer | #Dim. | #Head | Block Arch. | Special Modules | #Param. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𝓔S | – | – | – | – | 3D Conv. U-Net | 59.3M |

| 𝓓S | – | – | – | – | 3D Conv. U-Net | 73.7M |

| 𝓔 | 12 | 768 | 12 | 3D-SW-MSA + FFN | 3D Swin Attn. | 85.8M |

| 𝓓GS | 12 | 768 | 12 | 3D-SW-MSA + FFN | 3D Swin Attn. | 85.4M |

| 𝓓RF | 12 | 768 | 12 | 3D-SW-MSA + FFN | 3D Swin Attn. | 85.4M |

| 𝓓M | 12 | 768 | 12 | 3D-SW-MSA + FFN | 3D Swin Attn. + Sp. Conv. Upsampler | 90.9M |

| 𝓖S-B (text ver.) | 12 | 768 | 12 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. | 157M |

| 𝓖S-L (text ver.) | 24 | 1024 | 16 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. | 543M |

| 𝓖S-XL (text ver.) | 28 | 1280 | 16 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. | 975M |

| 𝓖S-L (image ver.) | 24 | 1024 | 16 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. | 556M |

| 𝓖L-B (text ver.) | 12 | 768 | 12 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. + Sp. Conv. Downsampler / Upsampler + Skip Conn. | 185M |

| 𝓖L-L (text ver.) | 24 | 1024 | 16 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. + Sp. Conv. Downsampler / Upsampler + Skip Conn. | 588M |

| 𝓖L-XL (text ver.) | 28 | 1280 | 16 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. + Sp. Conv. Downsampler / Upsampler + Skip Conn. | 1073M |

| 𝓖L-L (image ver.) | 24 | 1024 | 16 | MSA + MCA + FFN | QK Norm. + Sp. Conv. Downsampler / Upsampler + Skip Conn. | 600M |

🔼 This table details the architectures of the neural networks used in the paper. It shows the number of layers, dimensions, number of attention heads, the types of blocks used (including Shifted Window Multihead Self-Attention and Multihead Cross-Attention blocks, and Sparse Convolutional blocks), and the total number of parameters for each network. The networks are categorized by their role in the overall system: encoders, decoders, and the two-stage generation process (sparse structure generation and latent generation). Understanding this table is key to comprehending the computational complexity and design choices made in the model.

read the caption

Table 6: Network configurations used in this paper. SW stands for “Shifted Window”, MSA and MCA for “Multihead Self-Attention” and “Multihead Cross-Attention”, and Sp. Conv. for “Sparse Convolution”.

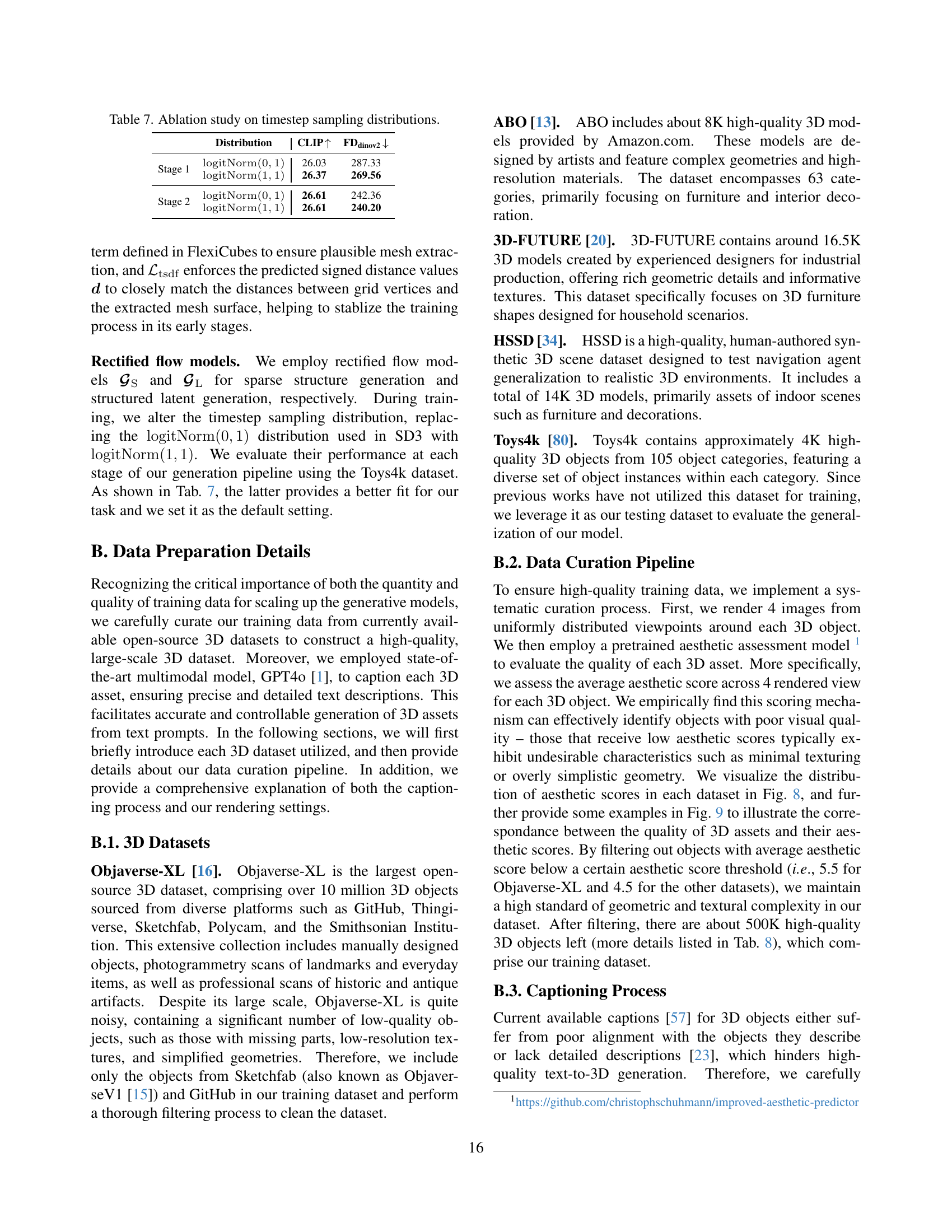

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to investigate the impact of different timestep sampling distributions on the performance of the model. Specifically, it examines the effect of using different probability distributions to sample timesteps during the training process of the model. The table shows how different sampling techniques (using logit Normal (0,1) and logit Normal (1,1) distributions) impact two key metrics: the CLIP score (a measure of prompt alignment) and the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) with DINOv2 features (a measure of image quality). This helps to determine the optimal timestep sampling strategy for improved model performance. The study is conducted separately for stage 1 and stage 2 of the model’s generation process.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation study on timestep sampling distributions.

| Distribution | CLIP↑ | FDdinov2↓ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | logitNorm(0,1) | 26.03 | 287.33 |

| logitNorm(1,1) | 26.37 | 269.56 | |

| Stage 2 | logitNorm(0,1) | 26.61 | 242.36 |

| logitNorm(1,1) | 26.61 | 240.20 |

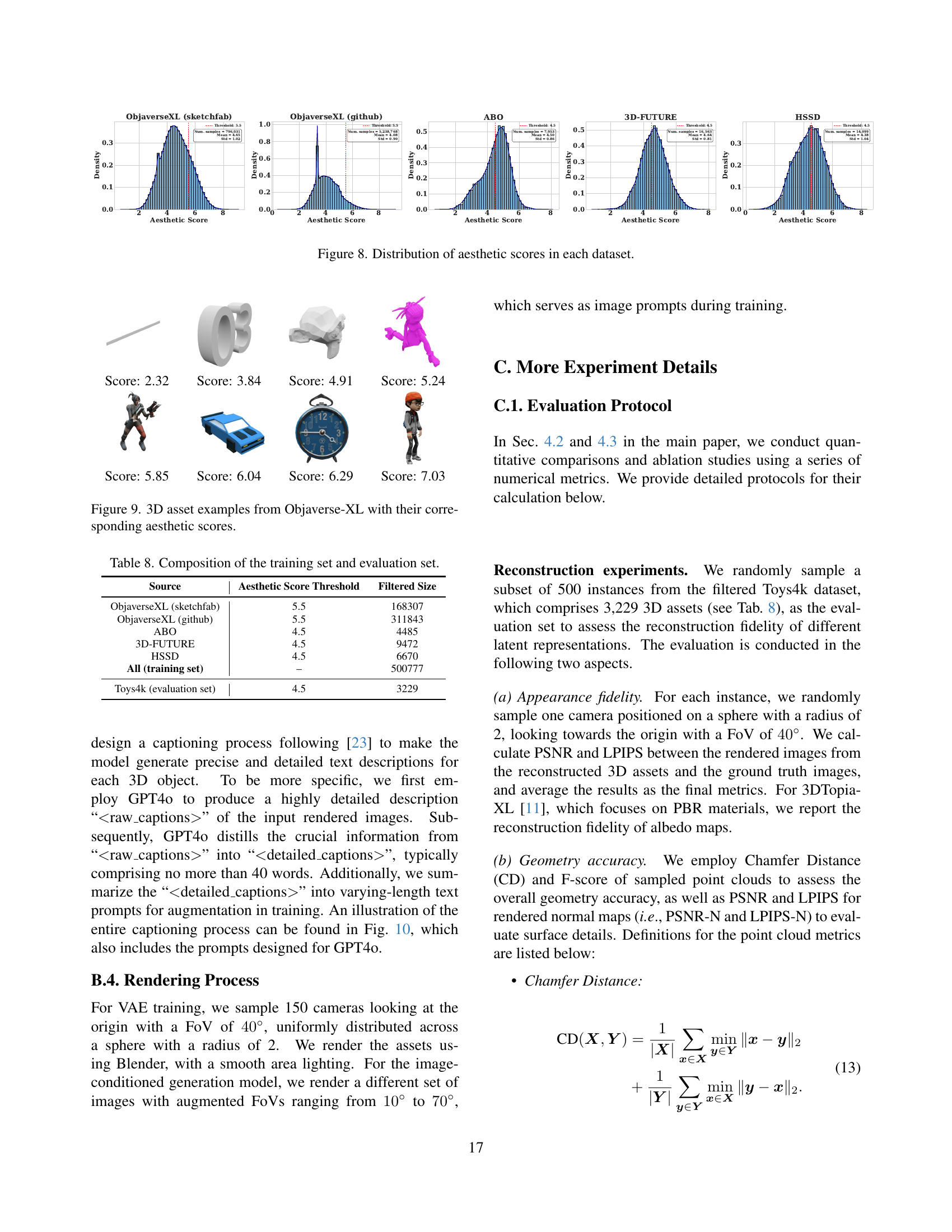

🔼 This table details the composition of the training and evaluation datasets used in the study. It shows the source of the 3D models (Objaverse-XL (Sketchfab), Objaverse-XL (Github), ABO, 3D-FUTURE, and HSSD), the threshold for aesthetic scores used to filter low-quality models, the number of samples remaining after filtering, and the average aesthetic score for each dataset. It also shows the size of the Toys4k dataset used for evaluation.

read the caption

Table 8: Composition of the training set and evaluation set.

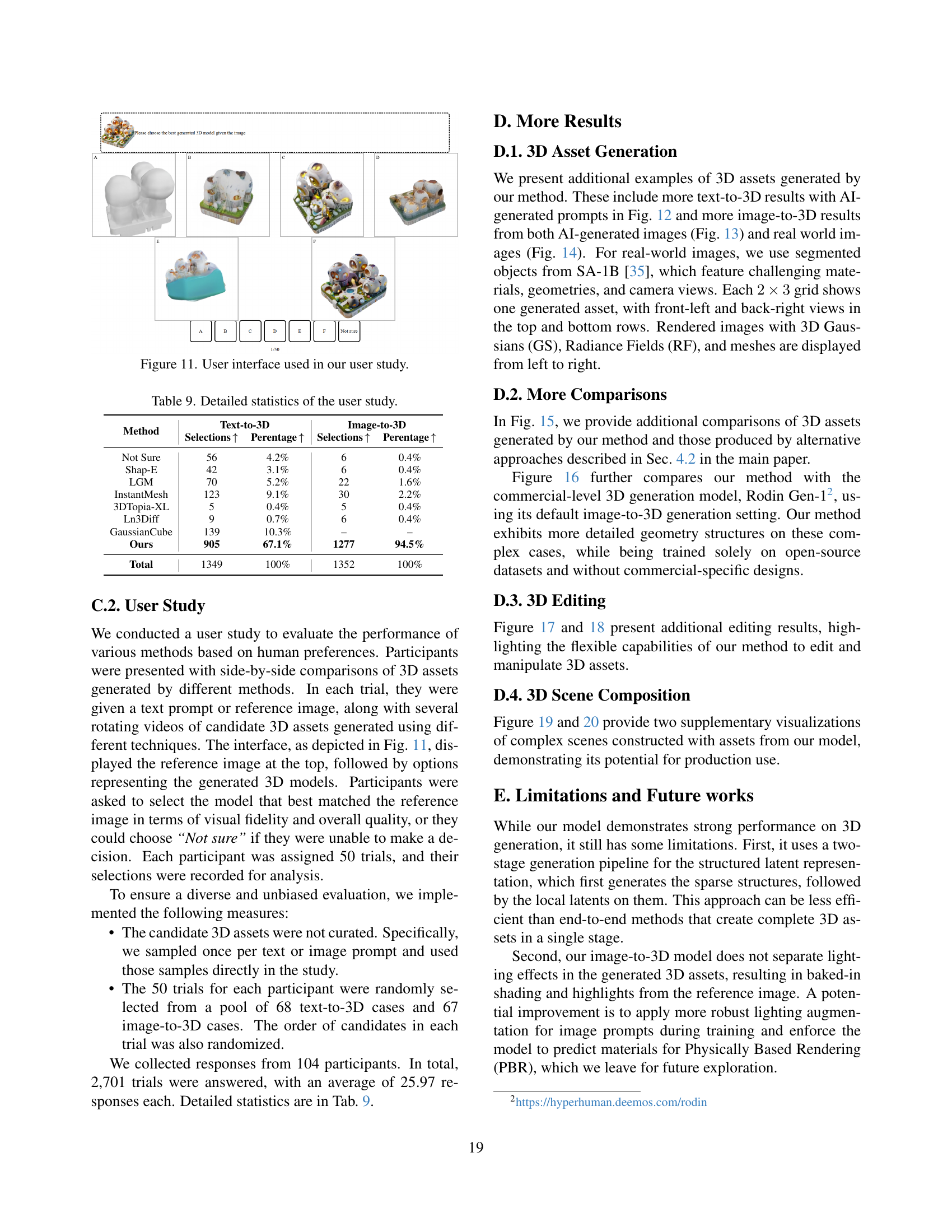

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of the results from a user study comparing different 3D asset generation methods. It shows the number of times each method was selected as the preferred model for both text-to-3D and image-to-3D generation tasks, along with the corresponding selection percentages. The ‘Not Sure’ category indicates instances where participants were unable to make a confident choice.

read the caption

Table 9: Detailed statistics of the user study.

Full paper#