TL;DR#

Current Vision-Language Models (VLMs) struggle with scalability and deployment on resource-limited devices. Larger models offer better performance but require more computational resources. This is a critical barrier to widespread adoption of VLMs in real-world applications.

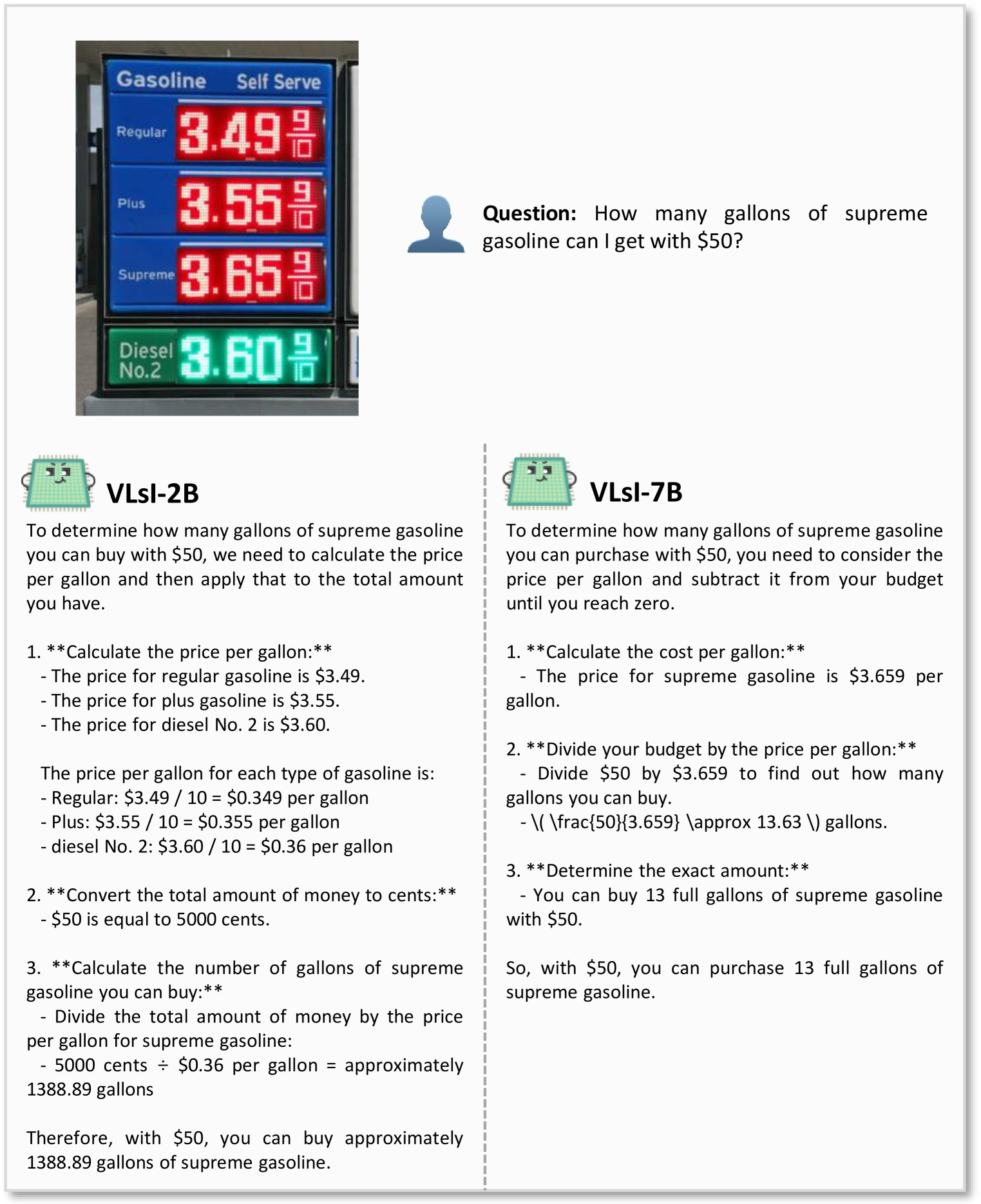

The paper introduces VLSI, a novel VLM family, which uses a unique layer-wise distillation technique. This process involves mapping features from each layer of a large VLM into a natural language space using ‘verbalizers’. Then, it aligns smaller VLMs’ layer-wise reasoning with larger VLMs. This approach significantly improves the efficiency and effectiveness of smaller VLMs without compromising accuracy, achieving notable performance gains compared to the state-of-the-art on various benchmarks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents VLSI, a novel and efficient approach to building Vision-Language Models (VLMs). It addresses the critical challenge of deploying high-performing VLMs on resource-constrained devices by introducing a unique layer-wise distillation process. This work directly contributes to the growing area of efficient deep learning and opens up new avenues for research in model compression and knowledge transfer. Its findings are highly relevant for researchers working on resource-efficient AI systems and deploying them in real-world applications.

Visual Insights#

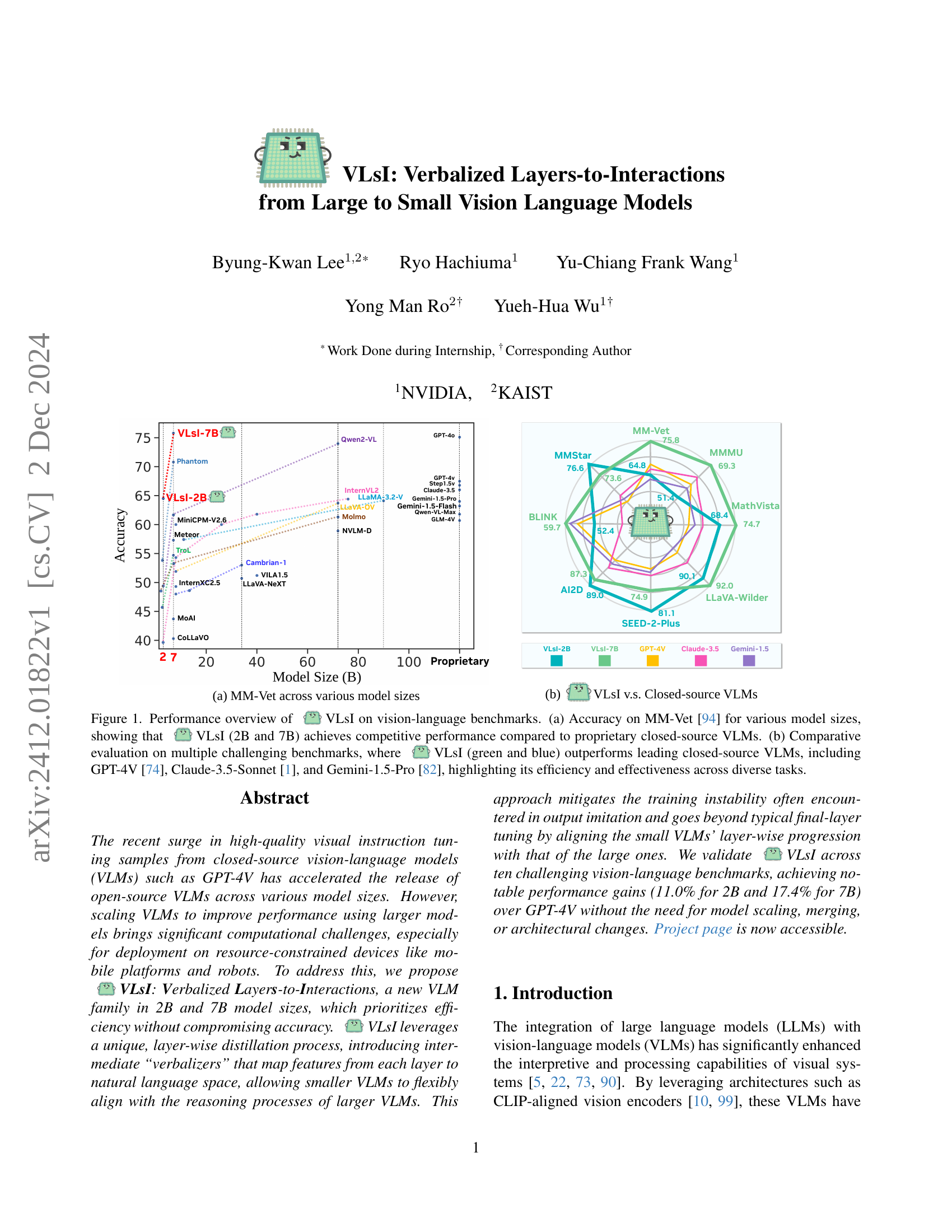

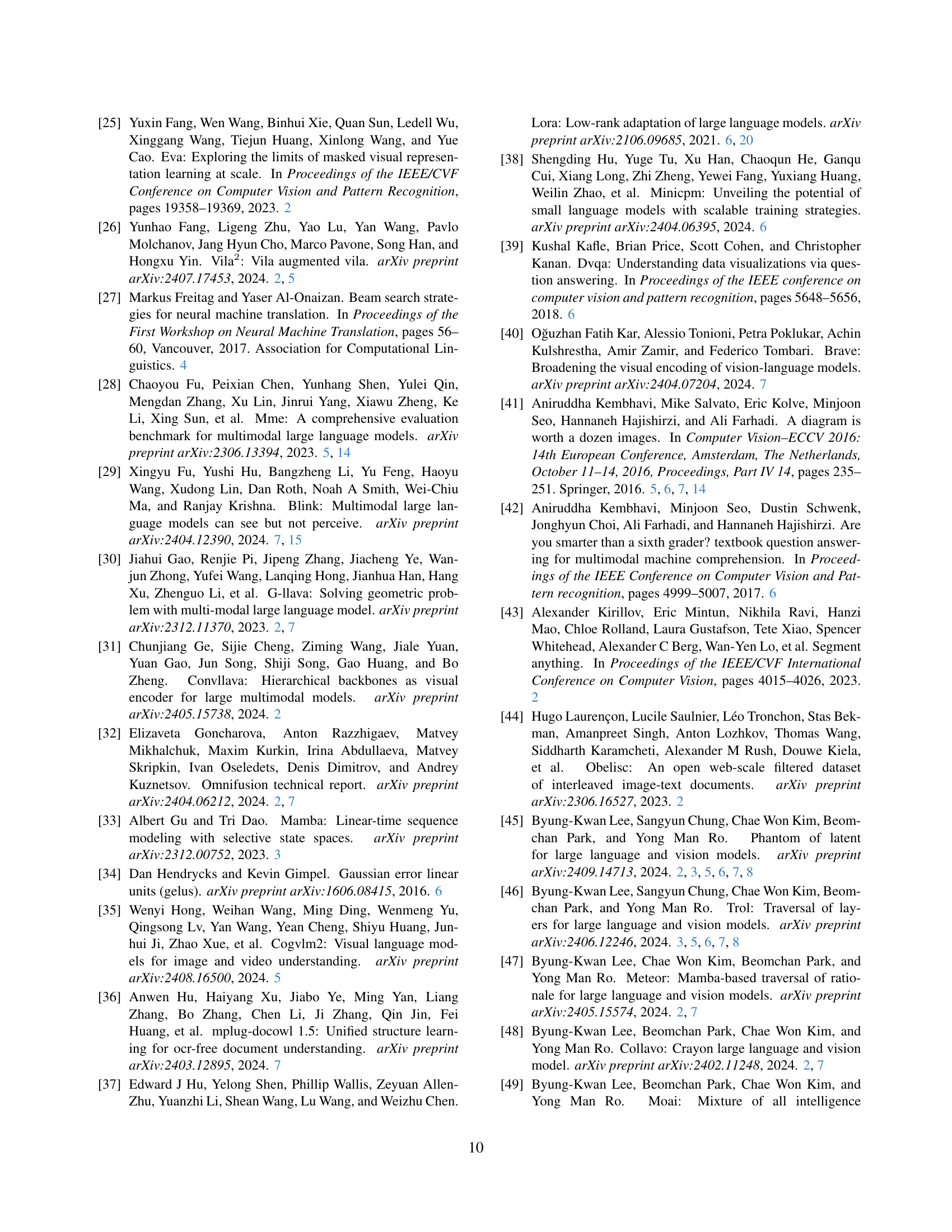

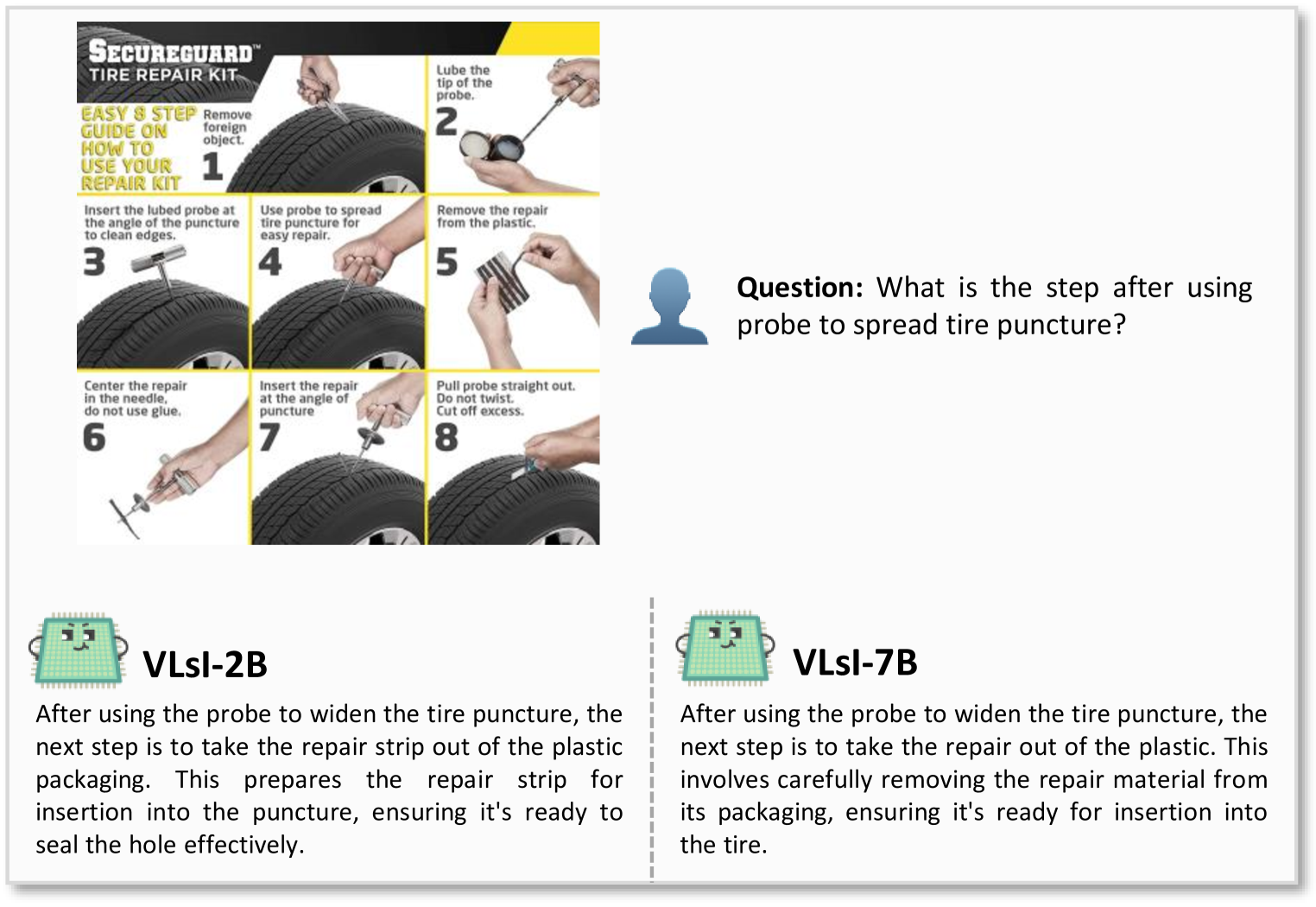

🔼 Figure 1 presents a performance comparison of the proposed VLSI model against other Vision-Language Models (VLMs) on various benchmark datasets. Panel (a) focuses on the MM-Vet benchmark, demonstrating that VLSI, in its 2B and 7B parameter versions, achieves accuracy comparable to leading proprietary closed-source VLMs of similar size. Panel (b) broadens the comparison across several challenging benchmarks, showing that VLSI surpasses the performance of top closed-source models (GPT-4V, Claude-3.5-Sonnet, and Gemini-1.5-Pro) while maintaining significantly higher efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 1: Performance overview of VLsI on vision-language benchmarks. (a) Accuracy on MM-Vet [94] for various model sizes, showing that VLsI (2B and 7B) achieves competitive performance compared to proprietary closed-source VLMs. (b) Comparative evaluation on multiple challenging benchmarks, where VLsI (green and blue) outperforms leading closed-source VLMs, including GPT-4V [74], Claude-3.5-Sonnet [1], and Gemini-1.5-Pro [82], highlighting its efficiency and effectiveness across diverse tasks.

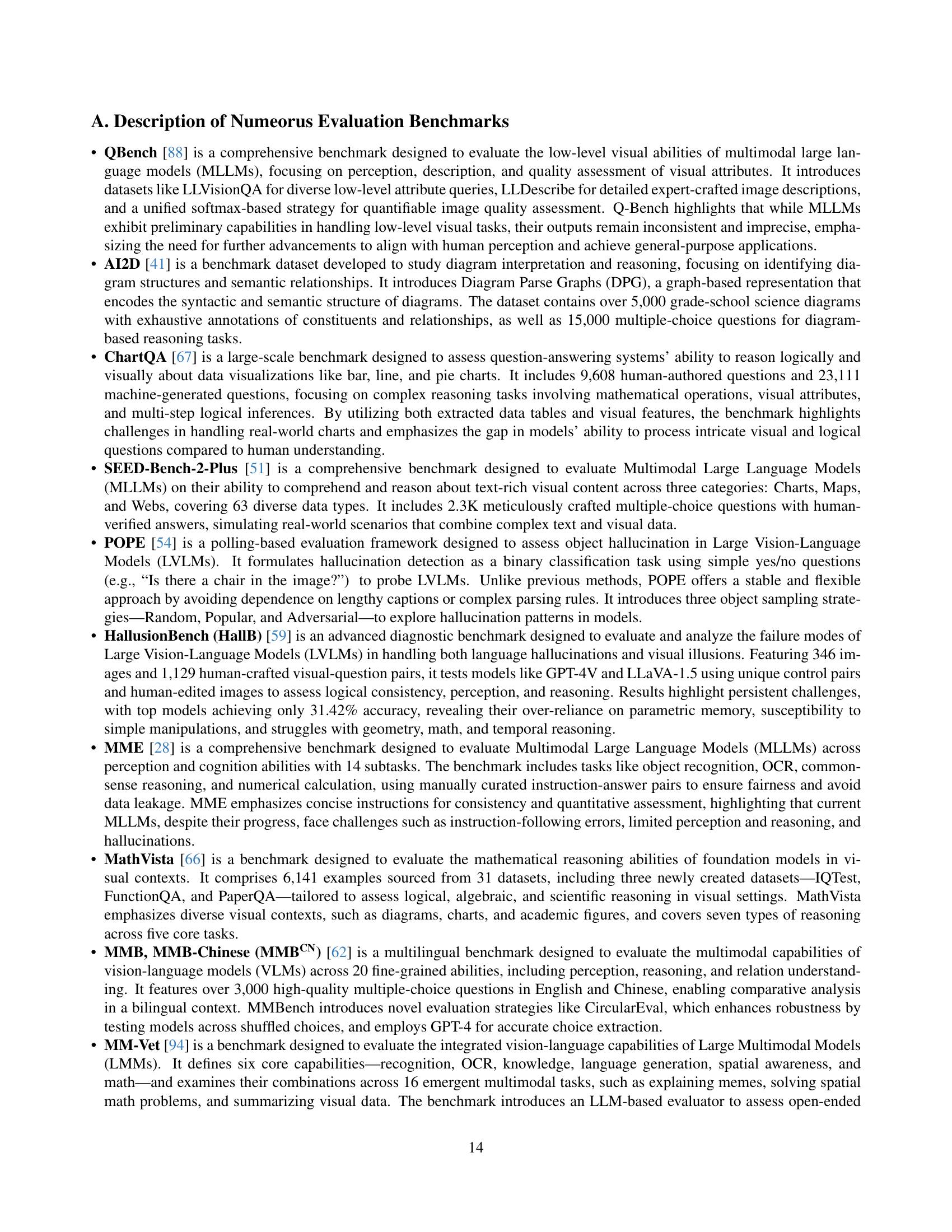

| VLMs | QBench | AI2D | ChartQA | POPE | HallB | MME | MathVista | MMB | MMBCN | MM-Vet | MMMU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLaVA-NeXT-7B [61] | - | - | - | 86.5 | - | 1851 | 34.6 | 69.6 | 63.3 | 43.9 | 35.1 | |

| LLaVA-NeXT-8B [61] | - | 71.6 | 69.5 | - | - | 1972 | 37.5 | 72.1 | - | - | 41.7 | |

| LLaVA-NeXT-13B [61] | - | 70.0 | 62.2 | 86.7 | - | 1892 | 35.1 | 70.0 | 68.5 | 47.3 | 35.9 | |

| MM1-7B [69] | - | - | - | 86.6 | - | 1858 | 35.9 | 72.3 | - | 42.1 | 37.0 | |

| MM1-MoE-7B<binary data, 1 bytes><binary data, 1 bytes>32 [69] | - | - | - | 87.8 | - | 1992 | 40.9 | 72.7 | - | 45.2 | 40.9 | |

| MiniGemini-HD-7B [56] | - | - | - | - | - | 1865 | 32.2 | 65.8 | - | 41.3 | 36.8 | |

| MiniGemini-HD-13B [56] | - | - | - | - | - | 1917 | 37.0 | 68.6 | - | 50.5 | 37.3 | |

| Cambrian-1-8B [84] | 73.0 | 73.3 | - | - | - | 49.0 | 75.9 | - | - | 42.7 | ||

| Cambrian-1-13B [84] | 73.6 | 73.8 | - | - | - | 48.0 | 75.7 | - | - | 40.0 | ||

| Eagle-8B [77] | 76.1 | 80.1 | - | - | - | 52.7 | 75.9 | - | - | 43.8 | ||

| Eagle-13B [77] | 74.0 | 77.6 | - | - | - | 54.4 | 75.7 | - | - | 41.6 | ||

| VILA1.5-8B [58] | - | - | - | 85.6 | - | - | - | 75.3 | 69.9 | 43.2 | 38.6 | |

| VILA1.5-13B [58] | - | - | - | 86.3 | - | - | - | 74.9 | 66.3 | 44.3 | 37.9 | |

| VILA2-8B [26] | - | - | - | 86.7 | - | - | - | 76.6 | 71.7 | 50.0 | 38.3 | |

| CogVLM2-8B [35] | - | 73.4 | 81.0 | - | - | 1870 | - | 80.5 | - | 60.4 | 44.3 | |

| LLaVA-OneVision-7B [52] | - | 81.4 | 80.0 | - | - | 1998 | 63.2 | 80.8 | - | 57.5 | 48.8 | |

| InternVL2-8B [10] | - | 83.8 | 83.3 | - | - | 2210 | 58.3 | 81.7 | 81.2 | 54.2 | 49.3 | |

| MiniCPM-V2.5-8B [92] | - | - | - | - | - | 2025 | 54.3 | 77.2 | 74.2 | - | 45.8 | |

| MiniCPM-V2.6-8B [92] | - | - | - | - | - | 2348 | 60.6 | - | - | 60.0 | 49.8 | |

| TroL-7B [46] | 73.6 | 78.5 | 71.2 | 87.8 | 65.3 | 2308 | 51.8 | 83.5 | 81.2 | 54.7 | 49.9 | |

| Phantom-7B [45] | 73.8 | 79.5 | 87.8 | 87.7 | 65.4 | 2126 | 70.9 | 84.8 | 84.7 | 70.8 | 51.2 | |

| Qwen2-VL-7B [87] | 77.5 | 77.5 | 83.0 | 88.9 | 65.7 | 2327 | 58.2 | 83.0 | 80.5 | 62.0 | 54.1 | |

| 77.5 | 87.3 | 86.1 | 88.6 | 74.2 | 2338 | 74.7 | 86.3 | 85.5 | 75.2 | 69.3 |

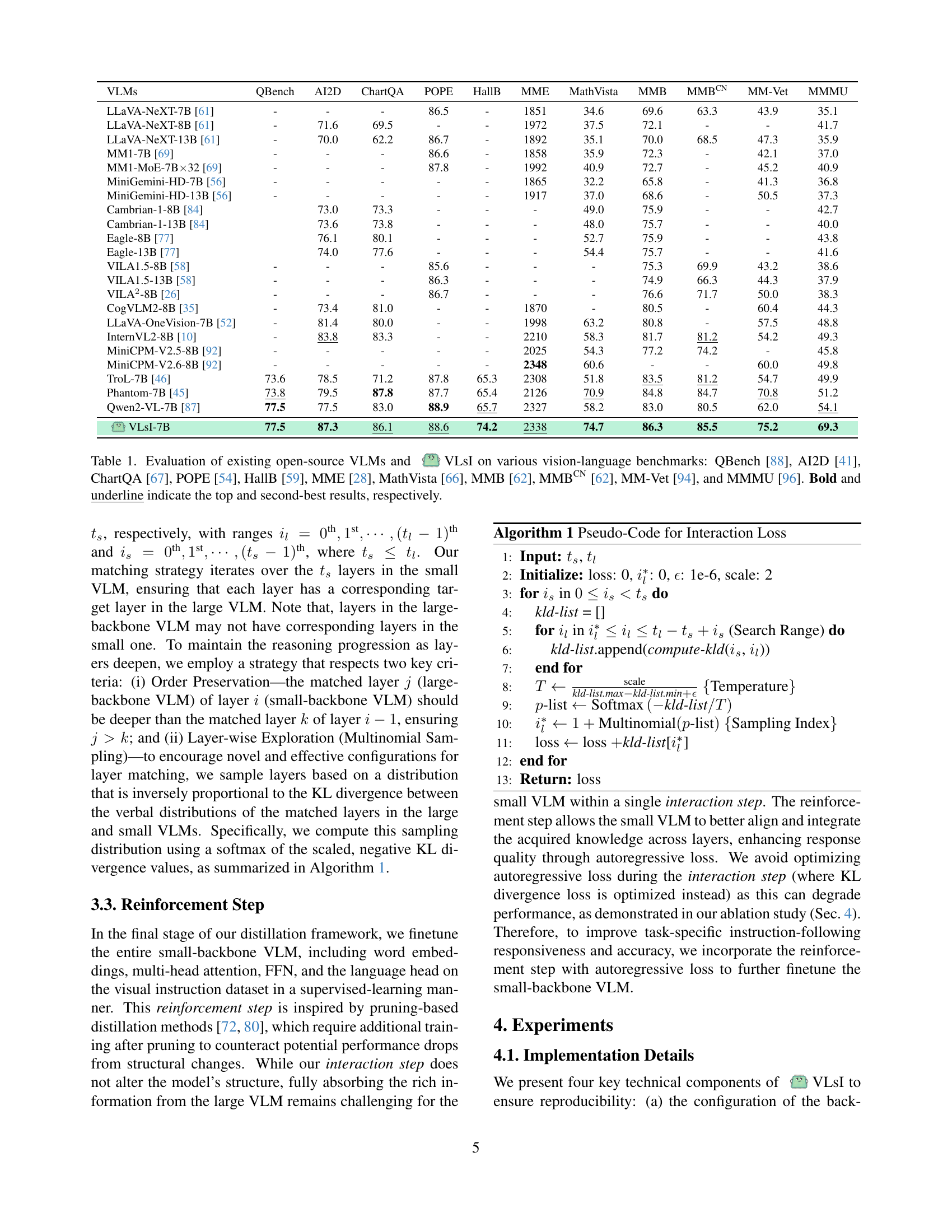

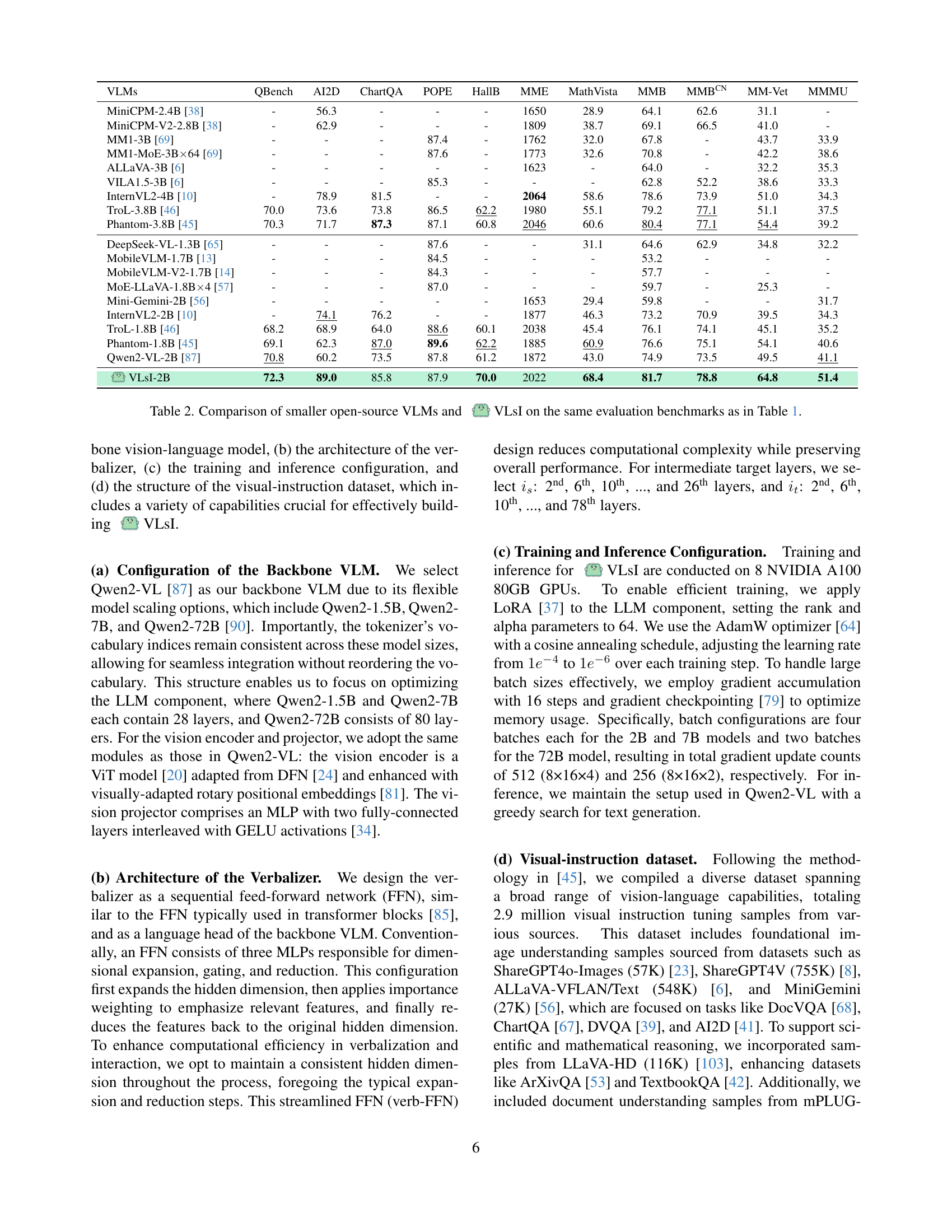

🔼 Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of various open-source Vision-Language Models (VLMs) and the newly proposed VLSI model. The evaluation is conducted across ten prominent vision-language benchmarks, assessing performance across diverse tasks. These benchmarks cover a wide range of capabilities, including low-level visual abilities (QBench), diagram interpretation (AI2D), chart-based reasoning (ChartQA), object hallucination detection (POPE), visual and logical reasoning in various settings (HallB, MME, MathVista, MMB, MMBCN, MM-Vet), and multimodal understanding and reasoning (MMMU). The table highlights VLSI’s competitive performance against existing models, particularly in achieving superior results on multiple benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation of existing open-source VLMs and VLsI on various vision-language benchmarks: QBench [88], AI2D [41], ChartQA [67], POPE [54], HallB [59], MME [28], MathVista [66], MMB [62], MMBCNCN{}^{\text{CN}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT CN end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT [62], MM-Vet [94], and MMMU [96]. Bold and underline indicate the top and second-best results, respectively.

In-depth insights#

VLSI: Layer-wise Distillation#

The concept of “VLSI: Layer-wise Distillation” presents a novel approach to knowledge transfer in Vision-Language Models (VLMs). Instead of the typical final-layer distillation, VLSI emphasizes a layer-by-layer approach, transferring knowledge incrementally. This is achieved by introducing intermediate “verbalizers” that translate the features from each layer into natural language. This strategy offers several key advantages: enhanced interpretability by making the reasoning process of the VLM more transparent, improved alignment between the large and small VLMs by aligning their layer-wise progression, and mitigated training instability often encountered in direct output imitation. By prioritizing layer-wise natural language alignment, VLSI effectively bridges the performance gap between large and small models without the need for model scaling or architectural changes, thus demonstrating significant efficiency gains. The use of natural language as an intermediary layer is a particularly innovative aspect of this technique, enabling a more flexible and effective knowledge transfer.

Benchmark Performance#

A thorough analysis of benchmark performance in a research paper requires careful consideration of several aspects. First, the choice of benchmarks is crucial. A robust evaluation needs a diverse set of established and relevant benchmarks that capture the full spectrum of the model’s capabilities. Simply relying on a single, widely used benchmark might mask weaknesses or strengths depending on that particular benchmark’s biases. Second, performance metrics should be clearly defined and appropriate for the specific tasks. Accuracy alone might not be sufficient; additional metrics like precision, recall, F1-score, or specific metrics relevant to the task itself should be incorporated to provide a more complete performance profile. Third, comparative analysis against state-of-the-art models is essential to establish the model’s position within the field. The results should be presented and discussed comparatively to highlight both strengths and weaknesses relative to existing approaches. Finally, a discussion of limitations related to the benchmarks themselves or the evaluation setup must be included. Acknowledging limitations ensures transparency and allows for informed interpretations of the results, ultimately contributing to a more complete and nuanced understanding of benchmark performance.

Ablation Study Insights#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a Vision-Language Model (VLM), this might involve removing specific modules (e.g., visual encoder, verbalizer, interaction module), or altering training parameters (e.g., removing reinforcement learning). Analyzing the resulting performance changes across multiple benchmarks reveals critical insights into the model’s architecture and training process. Key insights often include identifying the most impactful components, understanding the interplay between different modules, and evaluating the effectiveness of various training strategies. For instance, an ablation study might show that a specific module significantly improves reasoning capabilities, or that a particular training step is crucial for achieving high accuracy on certain tasks. Ultimately, ablation studies provide quantitative evidence to support design choices and offer a principled way to optimize the overall model architecture and training for improved efficiency and performance.

Efficient VLM Scaling#

Efficient Vision Language Model (VLM) scaling tackles the challenge of improving VLM performance without the associated computational costs of larger models. Current approaches often involve architectural modifications or adding specialized modules, but these methods introduce complexity and may hinder deployment on resource-constrained devices. A more efficient approach focuses on knowledge distillation, transferring knowledge from large, powerful VLMs to smaller, more efficient ones. This requires careful consideration of how to effectively transfer the reasoning processes of larger models, rather than simply mimicking their final outputs. Layer-wise distillation, where intermediate layers generate verbal responses in natural language, is a promising technique. This method enhances interpretability and alignment, allowing smaller VLMs to learn the reasoning progression of larger models more effectively. The resulting smaller VLMs retain high accuracy and efficiency, making them suitable for deployment across various platforms. Another key challenge involves managing the interaction between large and small VLMs, which requires robust algorithms for adaptive layer matching. This prevents unnecessary computational costs during the distillation process and facilitates transfer of knowledge across layers effectively.

Future Research Scope#

The ‘Future Research Scope’ section of a research paper on Vision Language Models (VLMs) should delve into several promising avenues. Improving efficiency and scalability is crucial, particularly for deployment on resource-constrained devices. This necessitates exploring novel architectural designs and optimization techniques that minimize computational costs without sacrificing performance. Addressing biases and ethical concerns in VLMs is paramount. Research should focus on developing methodologies for detecting and mitigating biases in training data and model outputs, ensuring fairness and equitable outcomes. Enhanced explainability and interpretability of VLMs is vital. This could involve creating techniques to visualize and understand the internal reasoning processes of VLMs, leading to greater trust and transparency. Extending capabilities to more complex tasks is another critical area. This would include developing VLMs capable of handling nuanced reasoning, commonsense knowledge, and multi-modal interactions. Finally, the paper should suggest research on benchmarking and evaluation, developing more rigorous and comprehensive benchmarks that accurately assess the overall performance of VLMs across various domains and tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

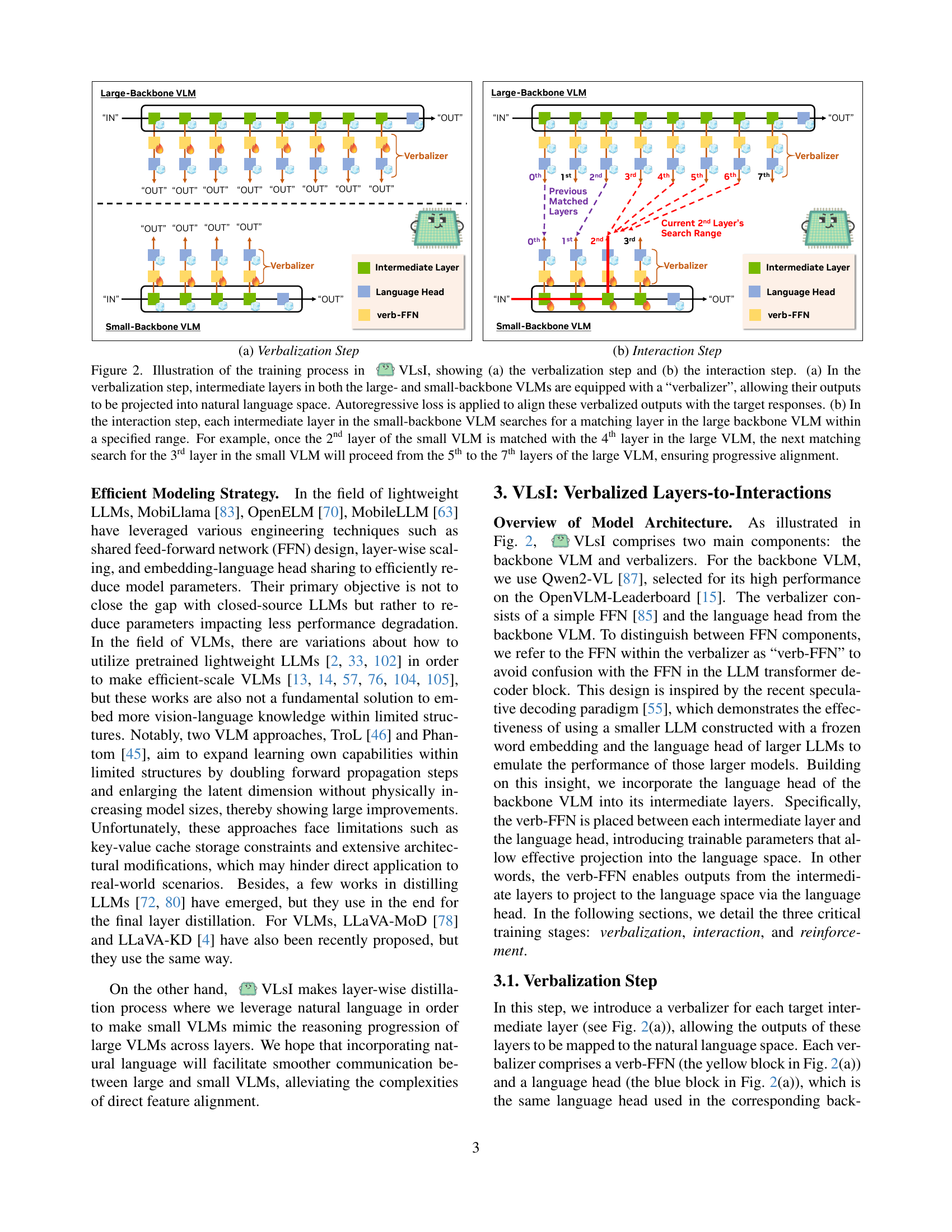

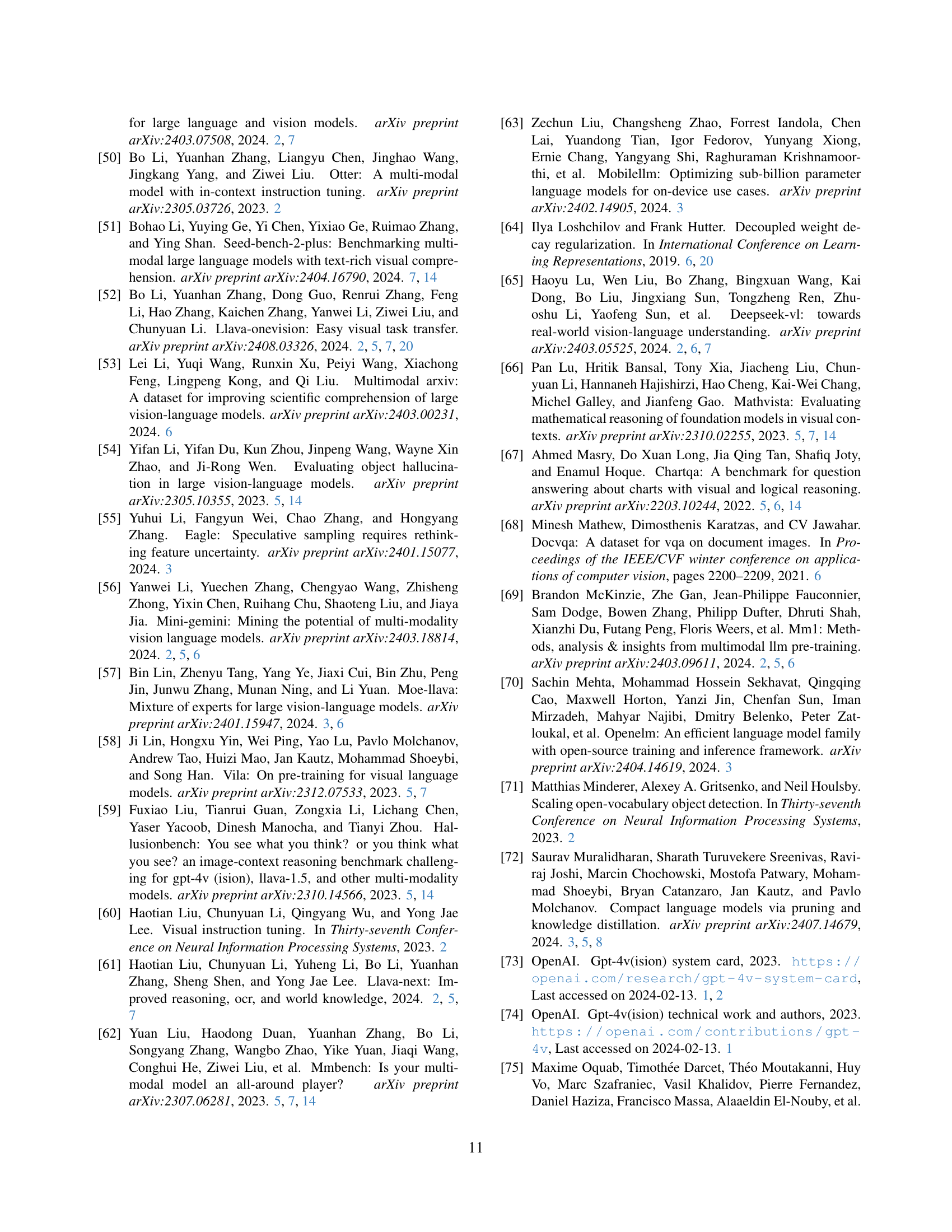

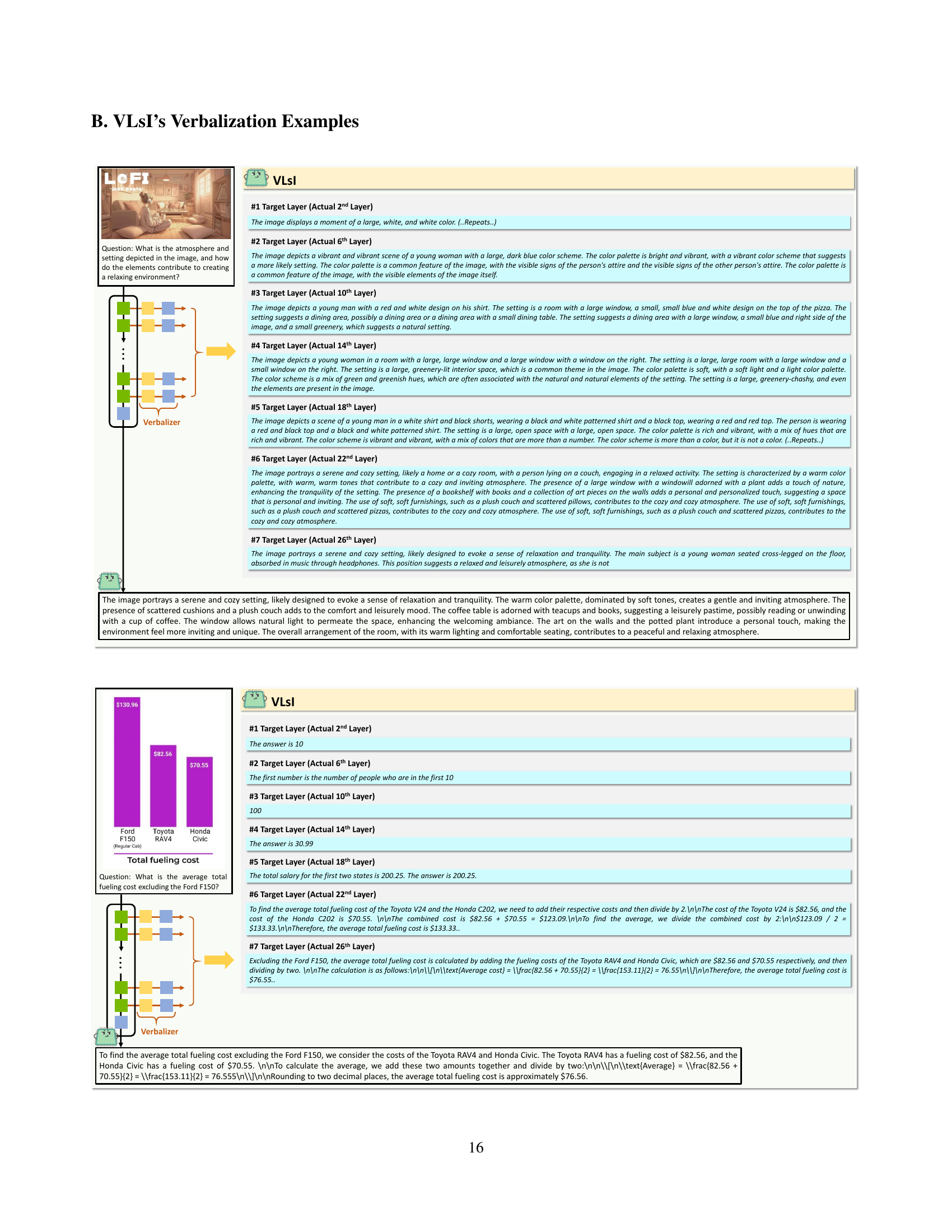

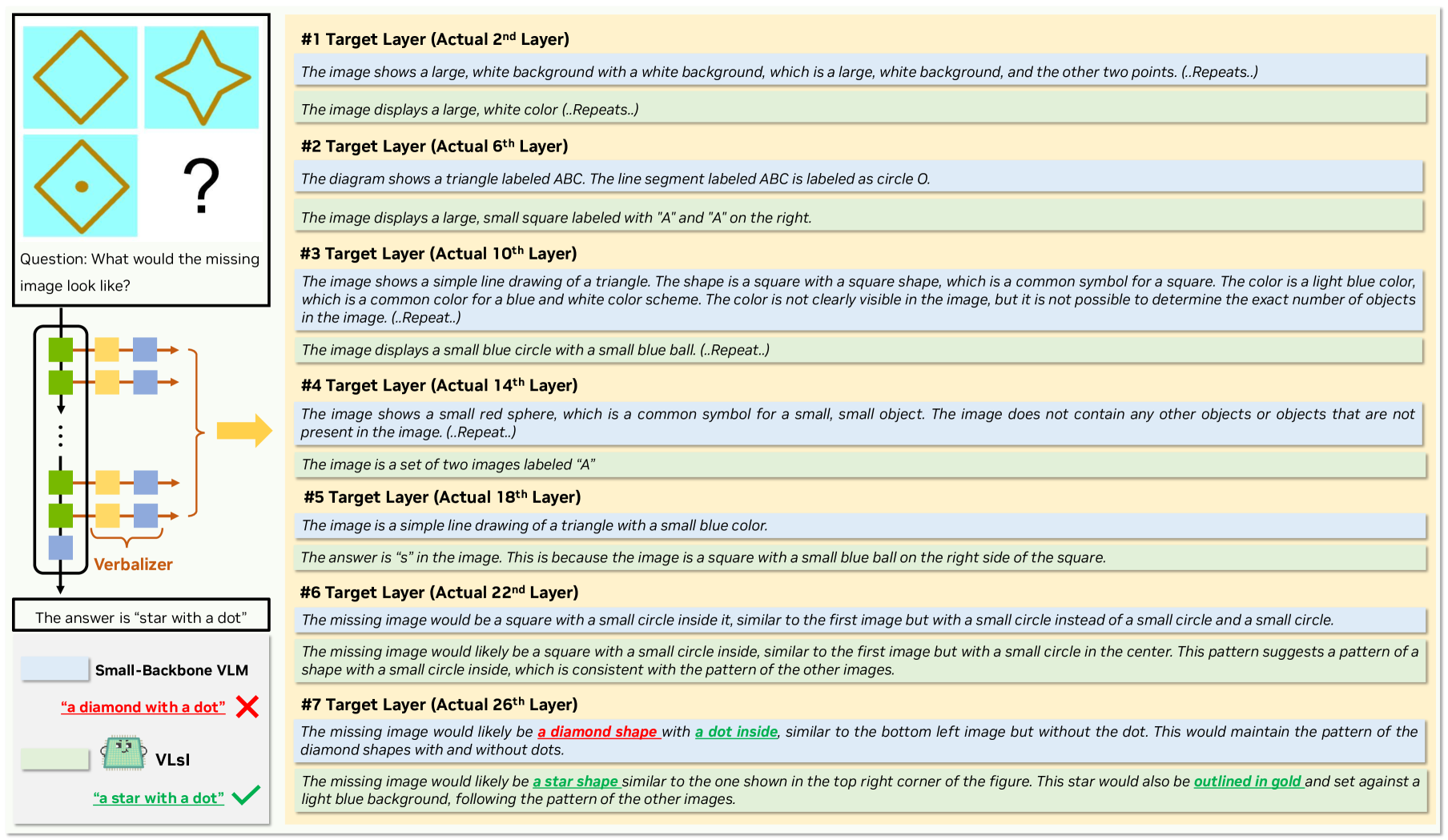

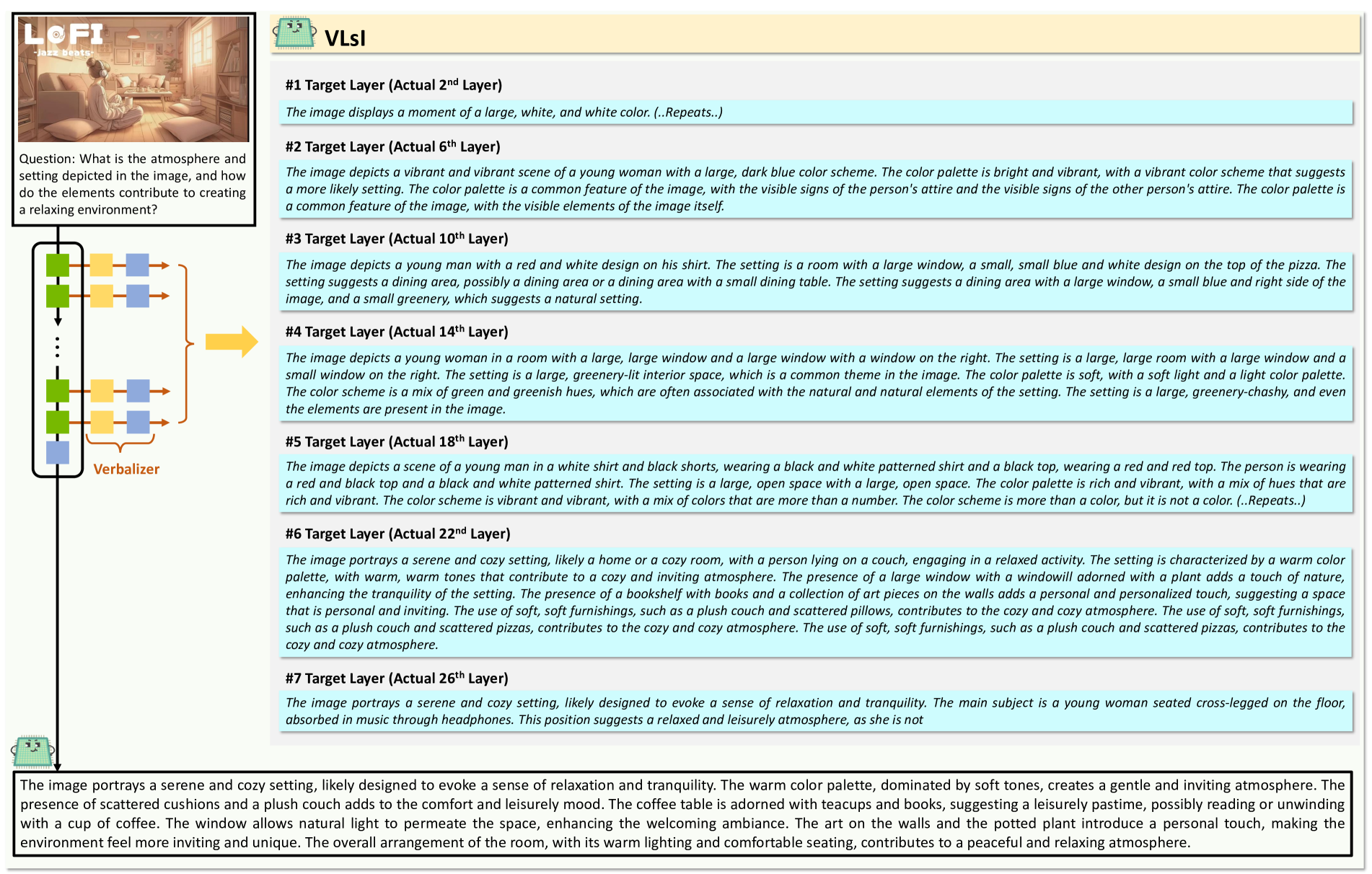

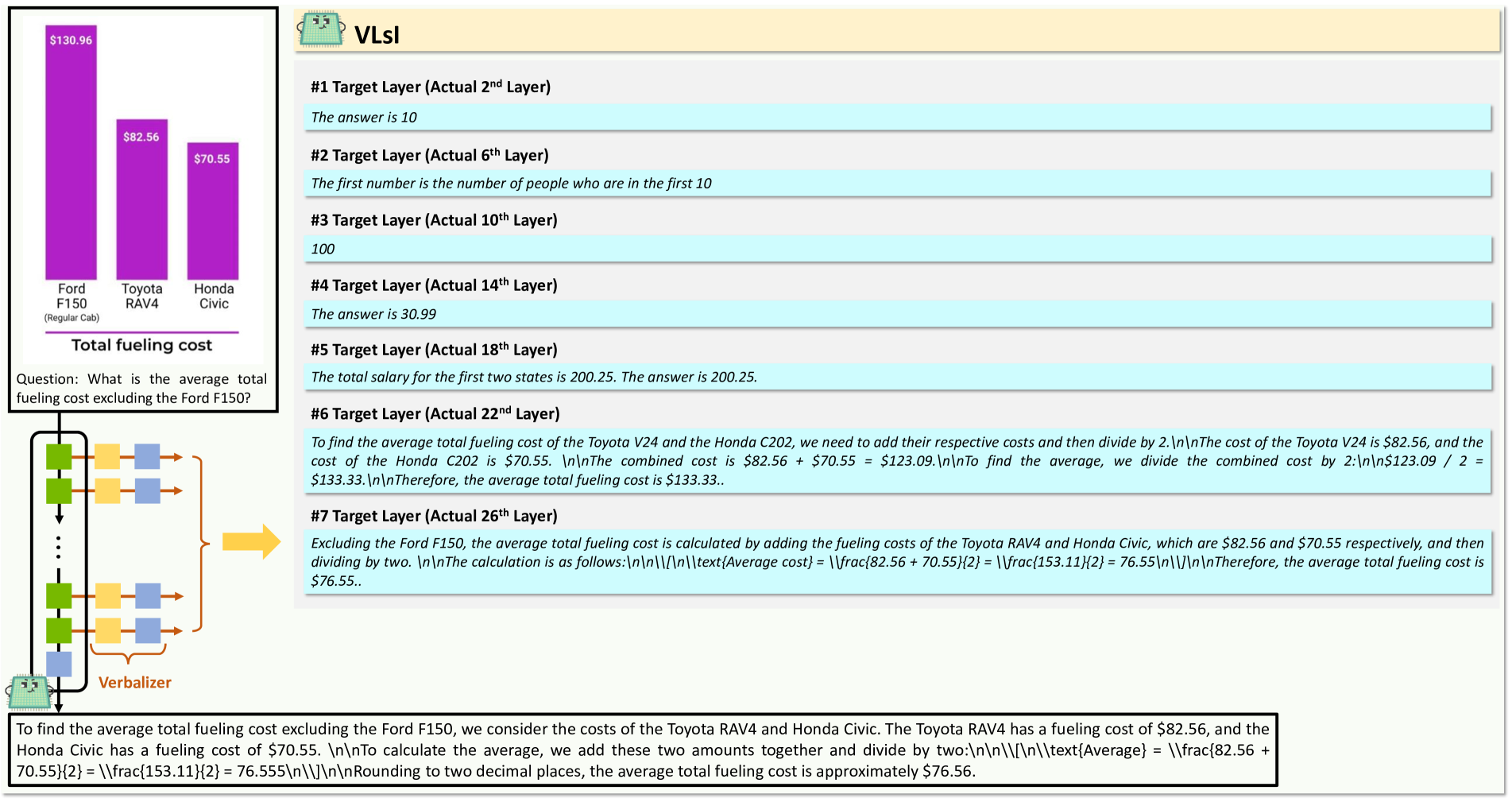

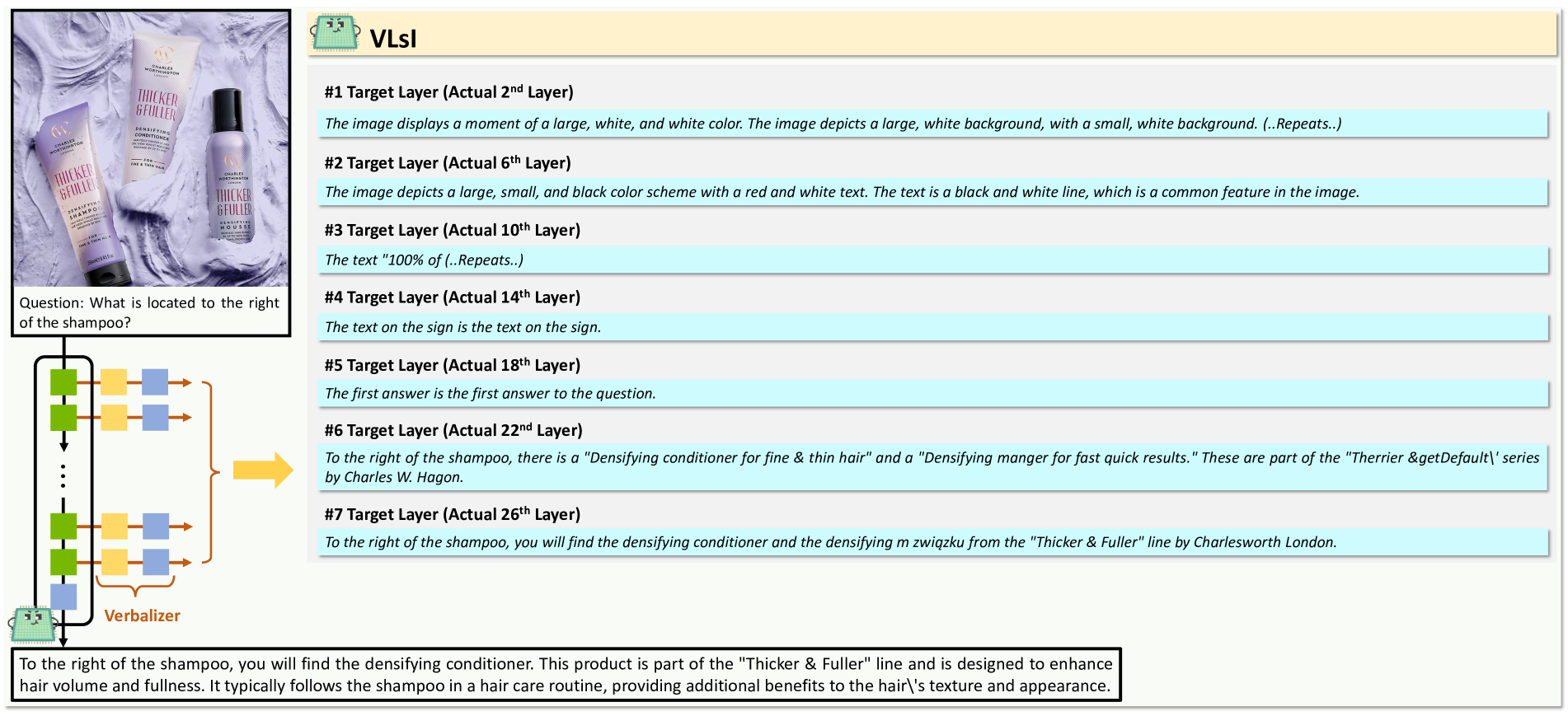

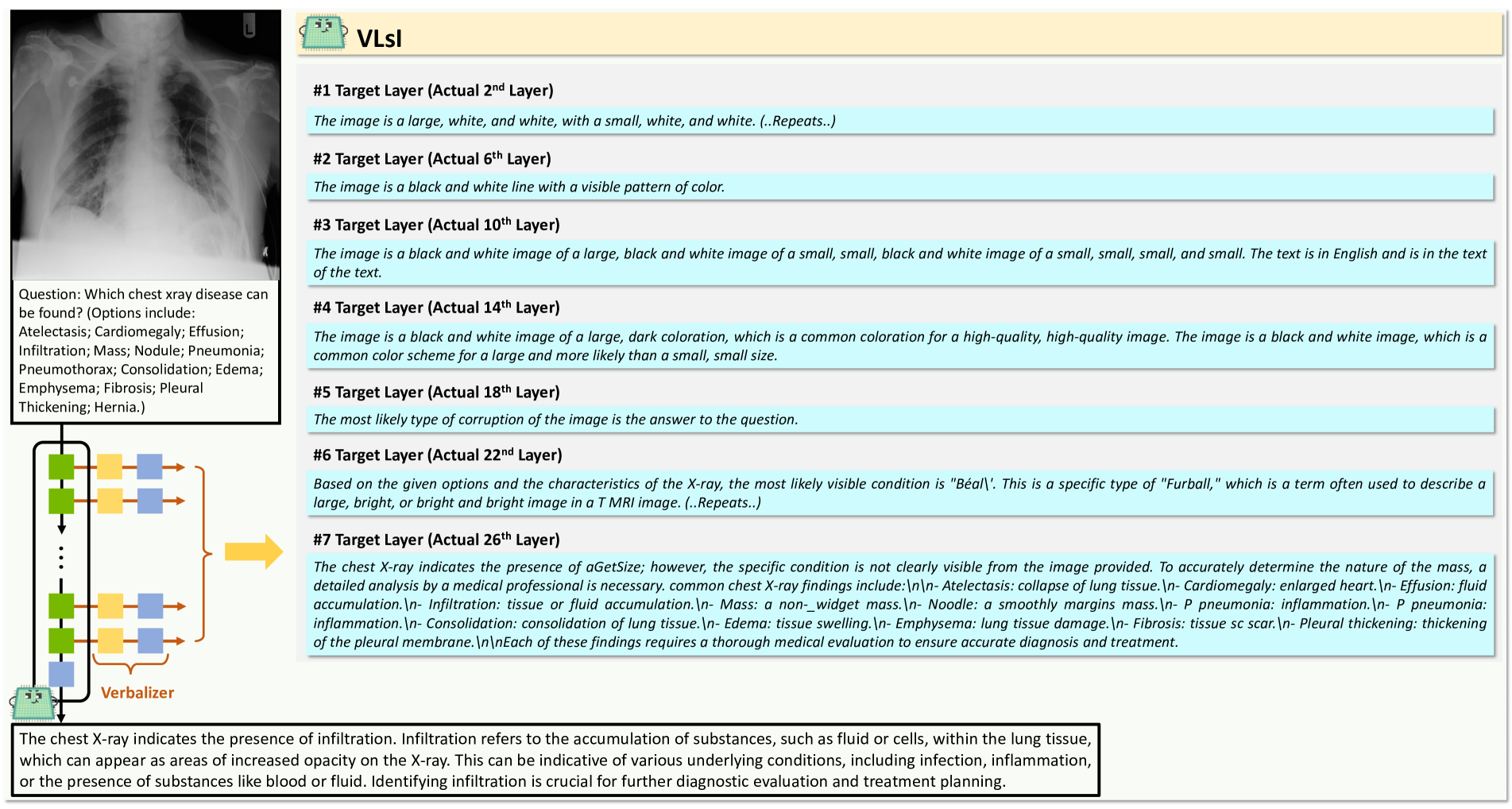

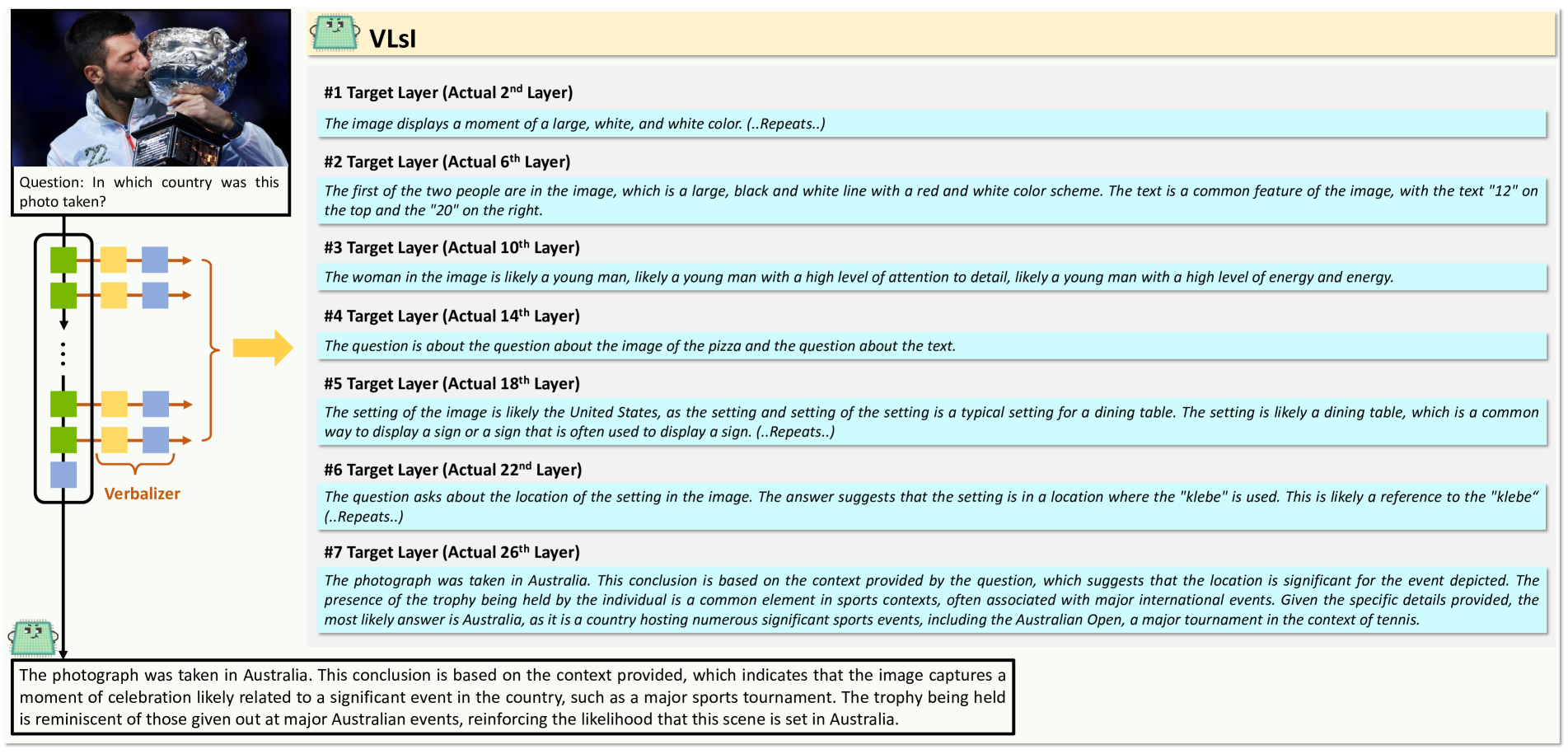

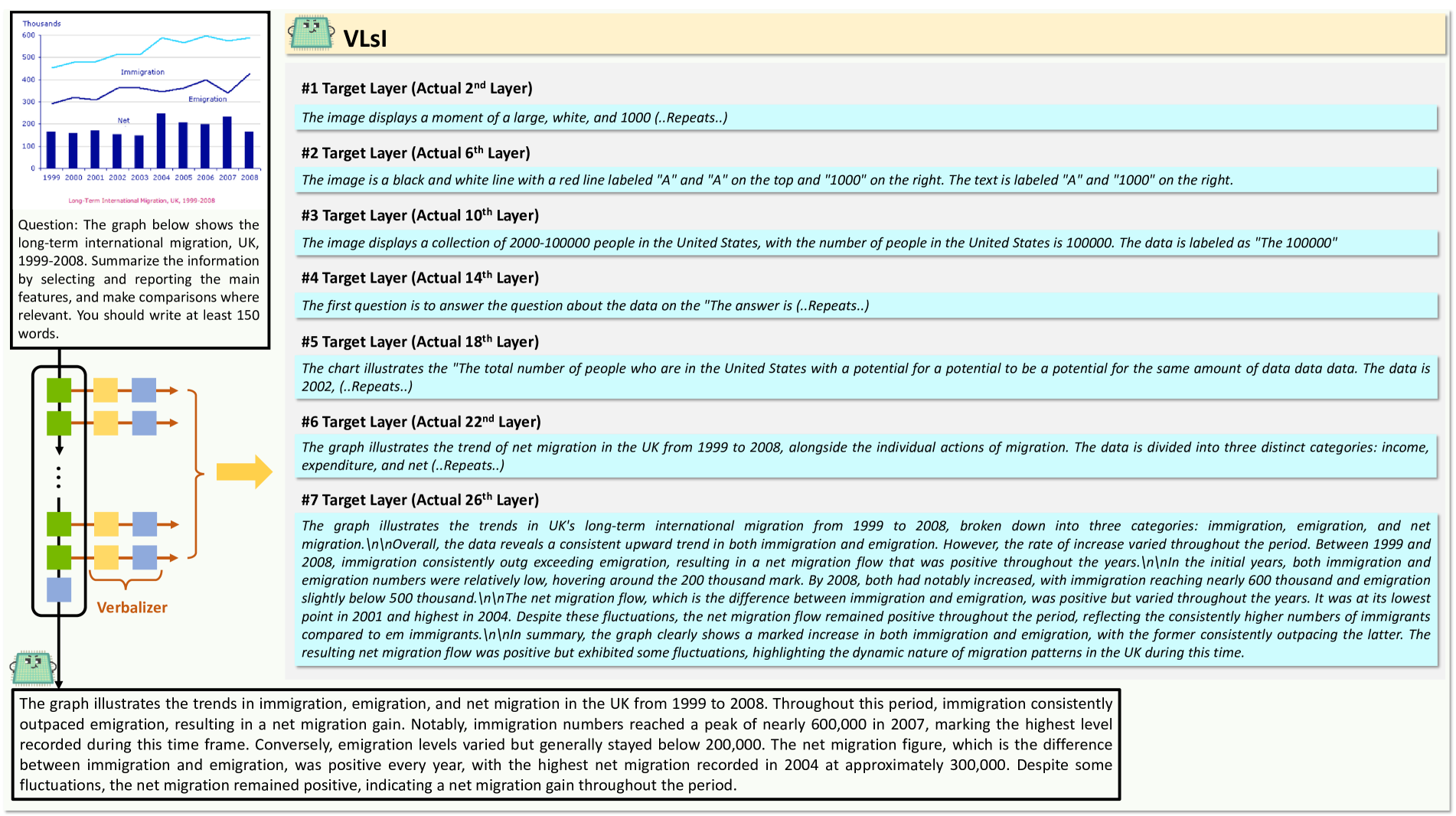

🔼 This figure illustrates the verbalization step of the VLSI (Verbalized Layers-to-Interactions) training process. In this step, intermediate layers in both the large and small backbone VLMs are equipped with a ‘verbalizer.’ This verbalizer allows the layer’s output to be projected into natural language space. Autoregressive loss is then used to align the verbalized outputs with the target responses. This process makes the intermediate layers’ outputs interpretable as text-based responses, enhancing interpretability and alignment with the larger model. The verbalization step is crucial for enabling effective layer-wise knowledge transfer from the large to small VLM.

read the caption

(a) Verbalization Step

🔼 This figure illustrates the second step of the VLSI training process, the ‘Interaction Step’. The goal is to establish a layer-wise mapping between the large and small backbone Vision Language Models (VLMs). The small VLM searches for corresponding layers in the large VLM based on intermediate verbal outputs. This ensures that the small VLM mimics the reasoning process of the larger VLM layer by layer. The search for matching layers is shown as a range search within the larger VLM, suggesting an adaptive, rather than strictly one-to-one mapping strategy.

read the caption

(b) Interaction Step

🔼 This figure illustrates the training process of the VLSI model, focusing on two key steps: verbalization and interaction. The verbalization step (a) involves adding a ‘verbalizer’ module to intermediate layers of both large and small Vision Language Models (VLMs). These verbalizers translate the layer’s feature representations into natural language descriptions. The model then uses autoregressive loss to align these verbalized descriptions with the ground truth responses, effectively teaching the smaller VLM to produce similar textual output at each layer. The interaction step (b) shows how the model finds corresponding layers between the large and small VLMs. It doesn’t directly map layers one-to-one, but rather searches within a defined range to find the best matching layers that align in terms of their reasoning progression. This adaptive layer matching ensures that the small VLM learns to follow the reasoning process of the large VLM effectively.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of the training process in VLsI, showing (a) the verbalization step and (b) the interaction step. (a) In the verbalization step, intermediate layers in both the large- and small-backbone VLMs are equipped with a “verbalizer”, allowing their outputs to be projected into natural language space. Autoregressive loss is applied to align these verbalized outputs with the target responses. (b) In the interaction step, each intermediate layer in the small-backbone VLM searches for a matching layer in the large backbone VLM within a specified range. For example, once the 2ndnd{}^{\text{nd}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT nd end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT layer of the small VLM is matched with the 4thth{}^{\text{th}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT th end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT layer in the large VLM, the next matching search for the 3rdrd{}^{\text{rd}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT rd end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT layer in the small VLM will proceed from the 5thth{}^{\text{th}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT th end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT to the 7thth{}^{\text{th}}start_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT th end_FLOATSUPERSCRIPT layers of the large VLM, ensuring progressive alignment.

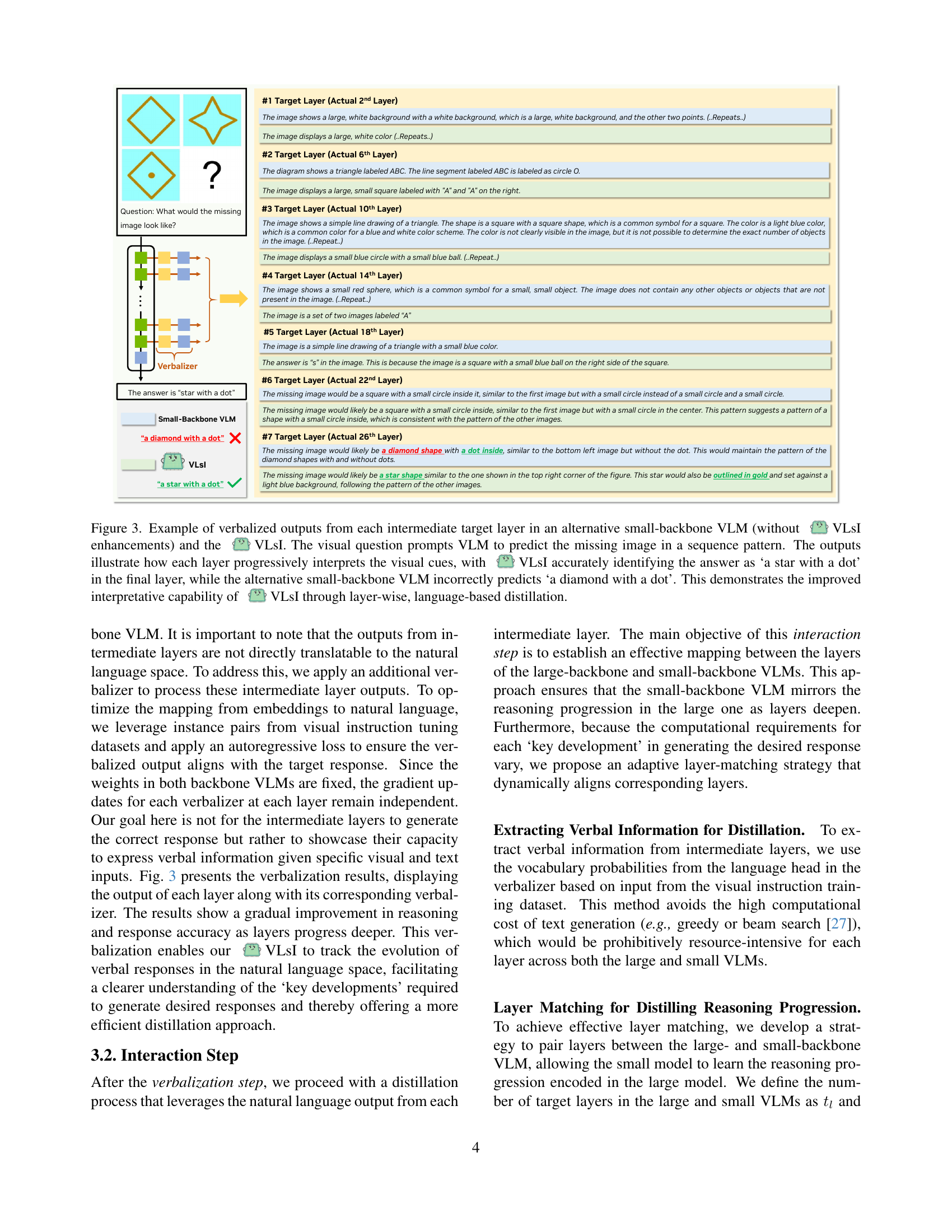

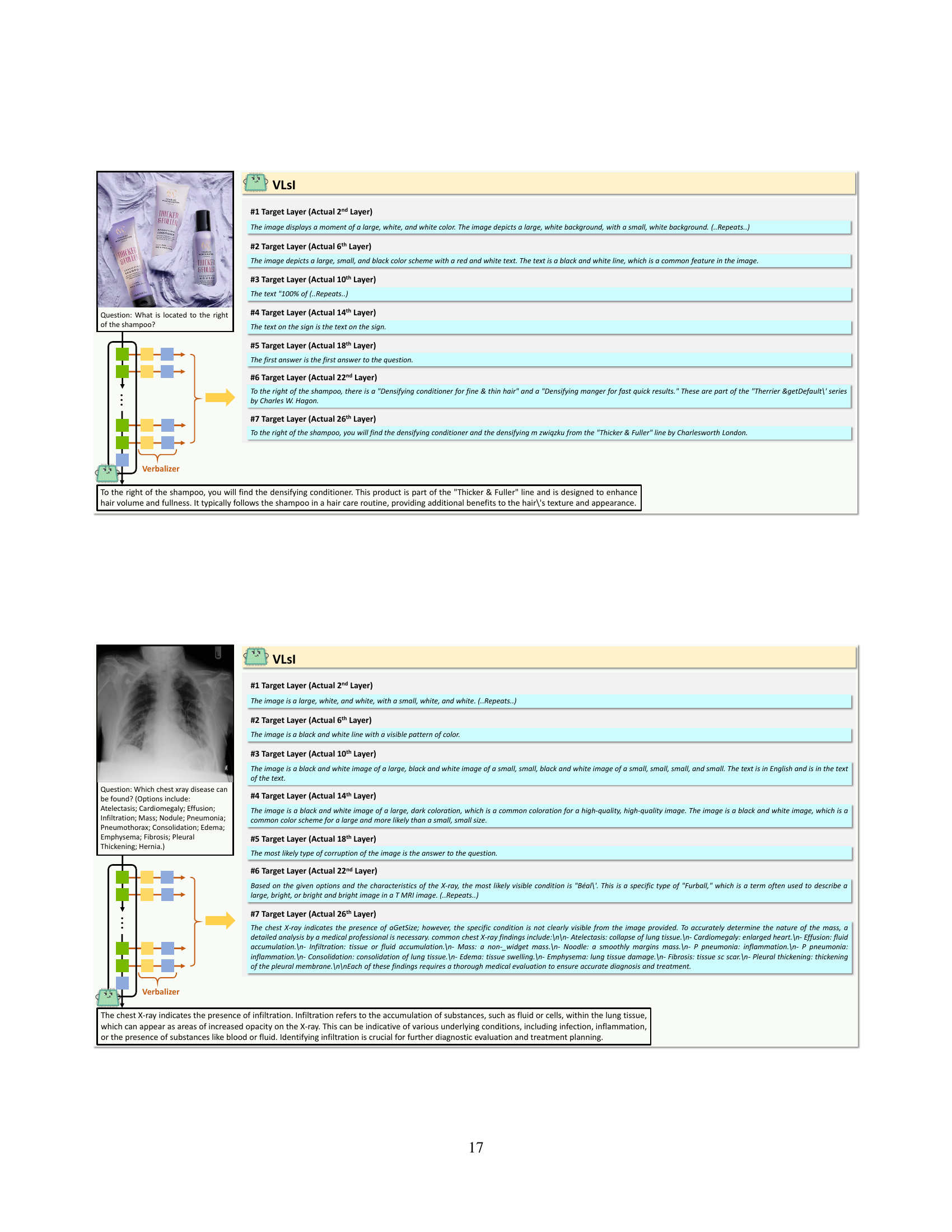

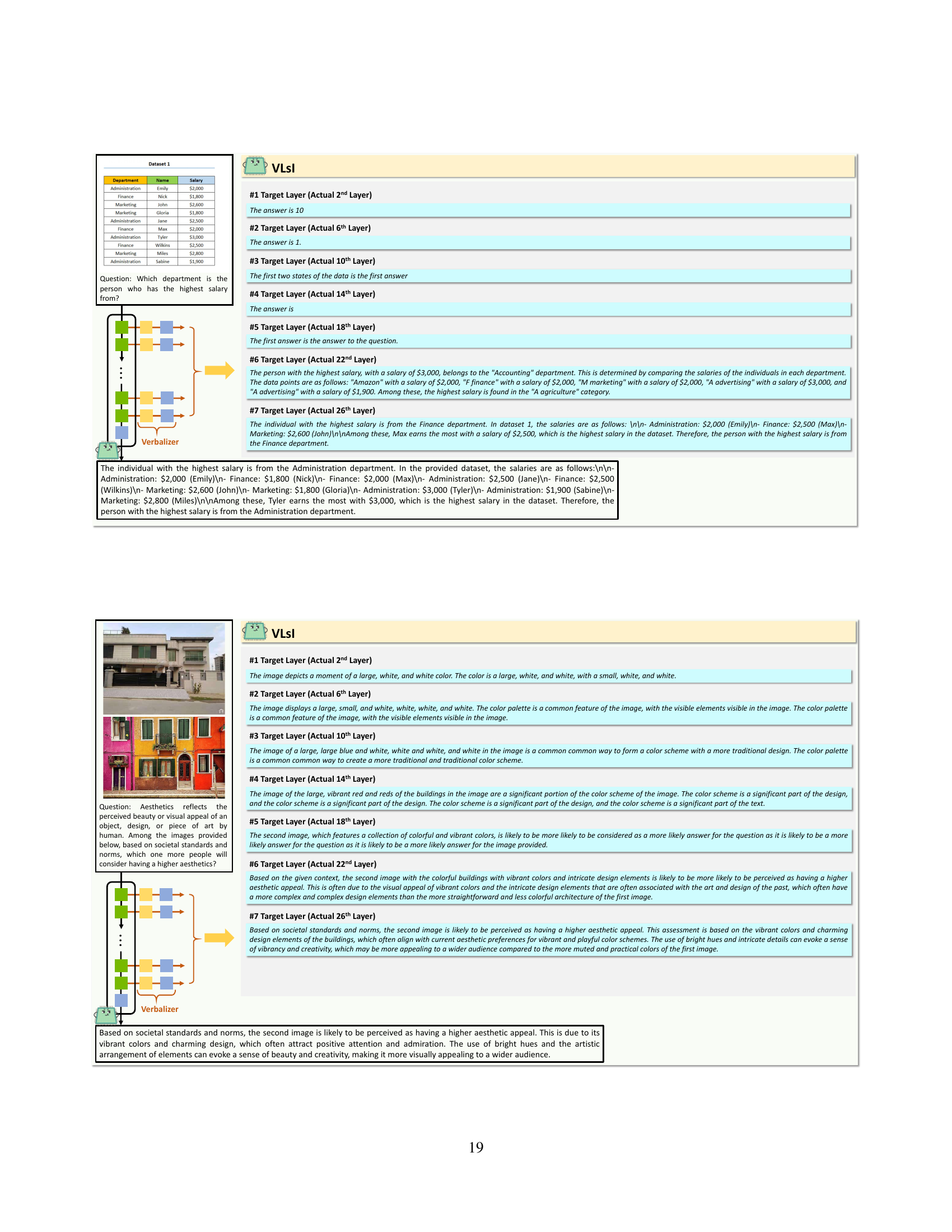

🔼 Figure 3 demonstrates the effectiveness of VLSI’s layer-wise, language-based distillation method. It shows the verbalized outputs at each intermediate layer of a small-backbone VLM (without VLSI enhancements) and VLSI when asked to predict the missing image in a sequence. The alternative small-backbone VLM incorrectly identifies the missing image as a ‘diamond with a dot’, while VLSI correctly predicts ‘a star with a dot’. This difference illustrates how VLSI progressively interprets visual cues at each layer, leading to a more accurate final prediction. The figure highlights the improved interpretative capabilities of VLSI compared to a standard small-backbone VLM.

read the caption

Figure 3: Example of verbalized outputs from each intermediate target layer in an alternative small-backbone VLM (without VLsI enhancements) and the VLsI. The visual question prompts VLM to predict the missing image in a sequence pattern. The outputs illustrate how each layer progressively interprets the visual cues, with VLsI accurately identifying the answer as ‘a star with a dot’ in the final layer, while the alternative small-backbone VLM incorrectly predicts ‘a diamond with a dot’. This demonstrates the improved interpretative capability of VLsI through layer-wise, language-based distillation.

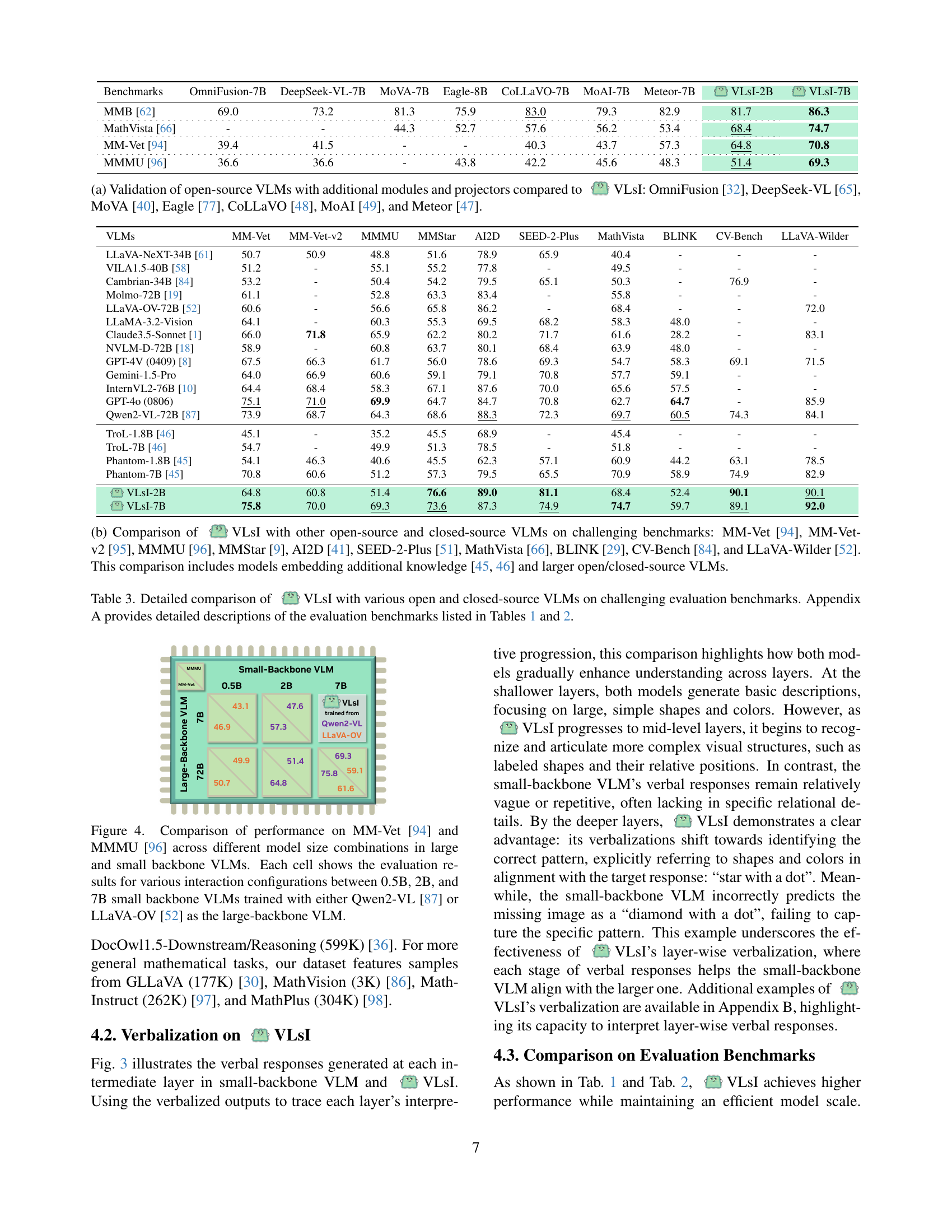

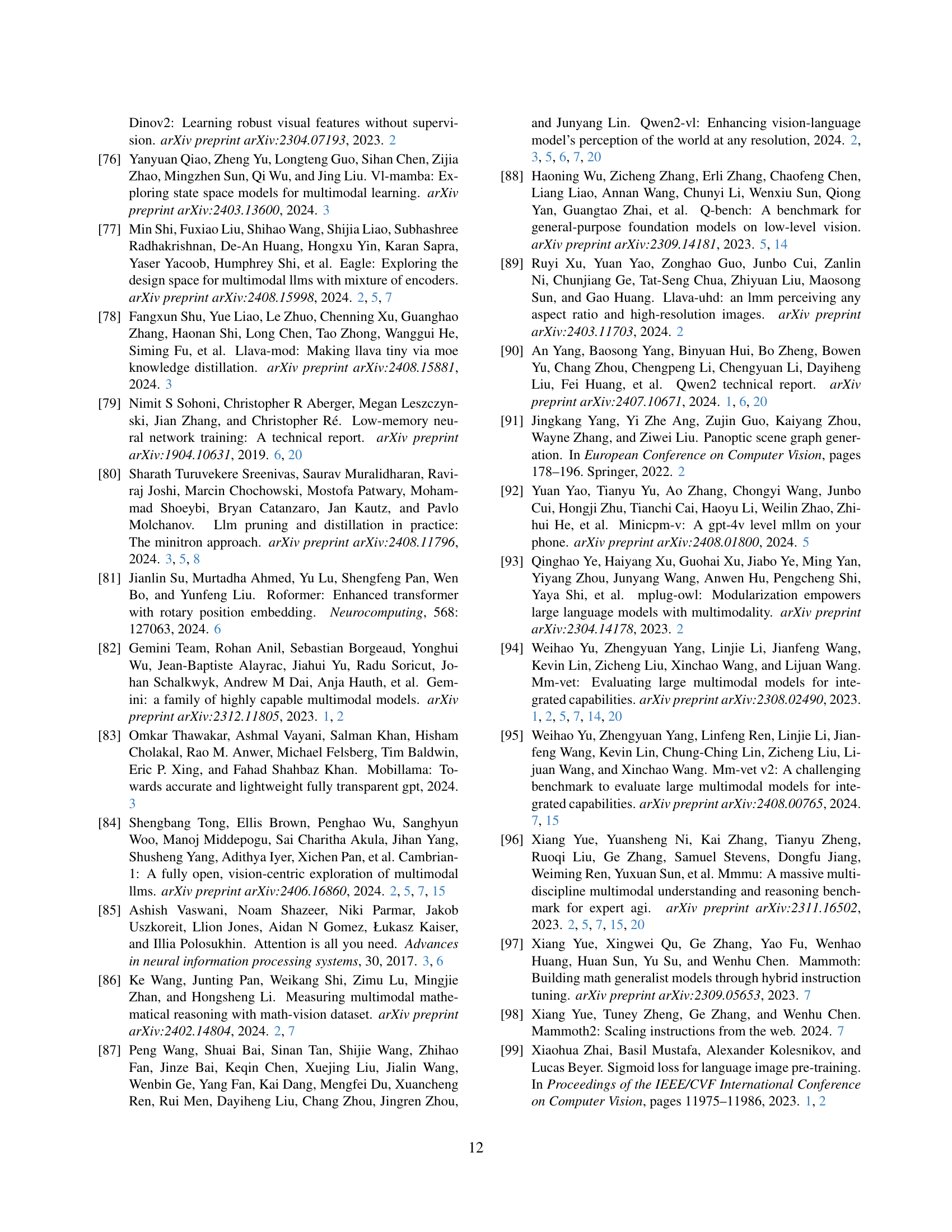

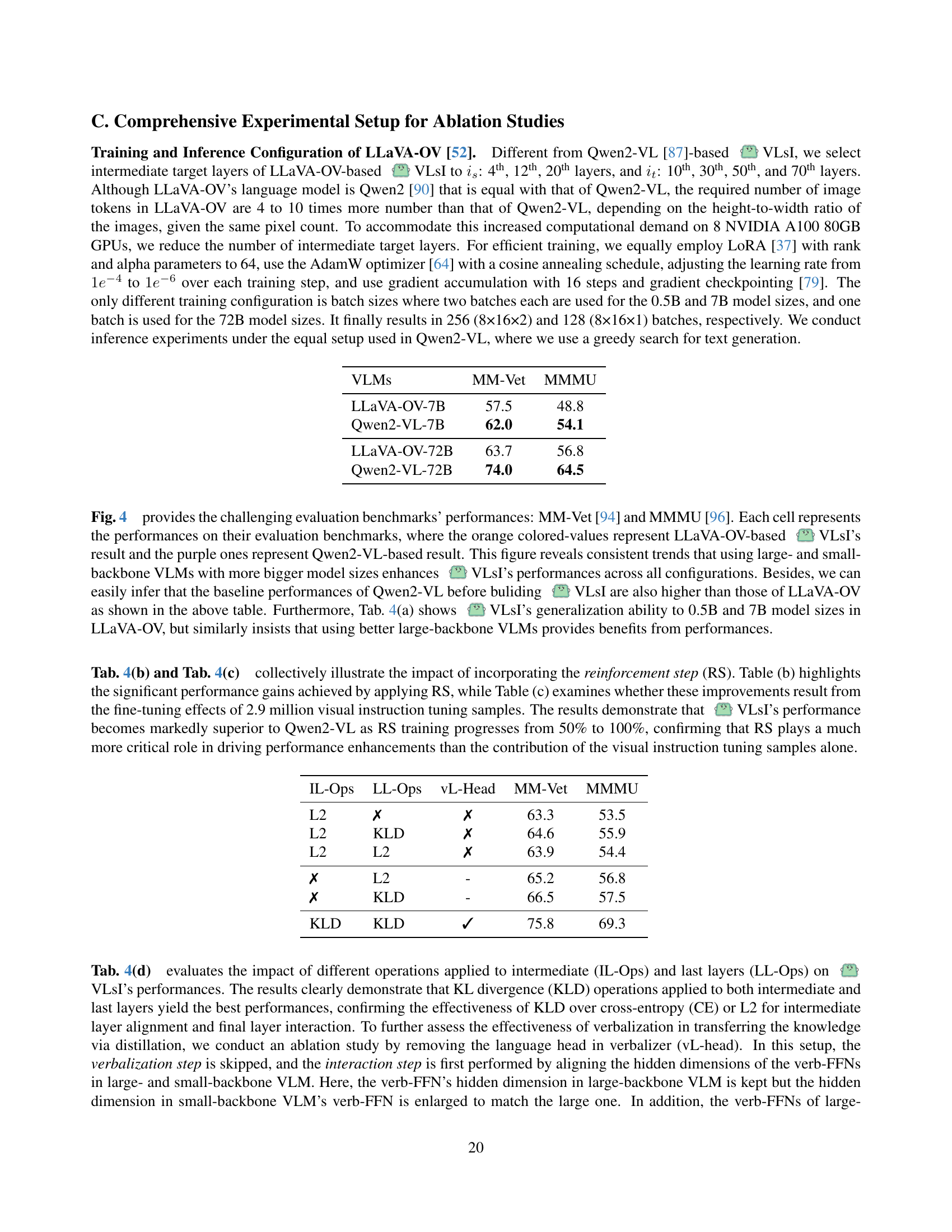

🔼 Figure 4 presents a detailed comparison of the performance achieved by various Vision-Language Models (VLMs) on two established benchmarks: MM-Vet and MMMU. The experiment focuses on evaluating the impact of different model sizes and training strategies. Specifically, the figure explores the performance differences when using small backbone VLMs (0.5B, 2B, and 7B parameters) trained using either Qwen2-VL or LLaVA-OV as the large backbone VLM. Each cell within the figure represents the performance achieved under a particular interaction configuration between a specific small backbone VLM and a large backbone VLM. This setup allows for a thorough analysis of how different model sizes and training approaches influence the final performance on these complex vision-language tasks.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of performance on MM-Vet [94] and MMMU [96] across different model size combinations in large and small backbone VLMs. Each cell shows the evaluation results for various interaction configurations between 0.5B, 2B, and 7B small backbone VLMs trained with either Qwen2-VL [87] or LLaVA-OV [52] as the large-backbone VLM.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of two different backbone Vision Language Models (VLMs), Qwen2-VL and LLaVA-OV, when used as the foundation for building the VLSI model. It shows how the choice of backbone VLM impacts the final performance of the VLSI model across various metrics on different vision-language benchmarks. The results illustrate that the performance of the VLSI model can be significantly influenced by the capabilities of its underlying backbone VLM.

read the caption

(a) Backbone VLMs

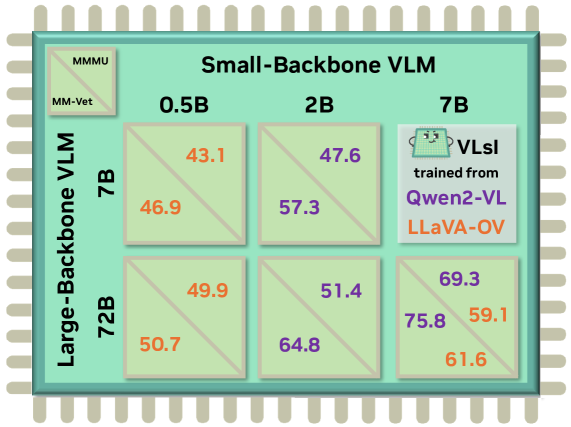

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of applying different operations to intermediate and last layers within the VLSI model. It compares the effectiveness of using cross-entropy (CE), L2 loss, and Kullback-Leibler divergence (KLD) for both intermediate layer matching and the final layer interaction. The results illustrate the relative performance of various loss functions, showing the optimal combination for transferring knowledge from large to small VLMs.

read the caption

(d) Operations for Intermediate/Last Layers

🔼 This ablation study investigates the effect of the reinforcement step (RS) in the VLSI model training. It compares the model’s performance on multiple vision-language benchmarks (MMB, BLINK, MM-Vet, MMMU) when the reinforcement step is included versus when it’s excluded. The results demonstrate the impact of the reinforcement step on enhancing performance across different benchmarks, highlighting its effectiveness in fine-tuning the model for improved accuracy and responsiveness.

read the caption

(b) Use of Reinforcement Step (RS)

🔼 This figure details the ablation study on different layer matching strategies used in the VLSI model. It compares the performance of different strategies: Random Index, Bottom-k Index (where k represents the number of bottom indices selected), and Multinomial Sampling. The results demonstrate the impact of various components on matching layer effectiveness within the distillation process. Order preservation and adaptive temperature further enhance performance. The best results are achieved when utilizing multinomial sampling, incorporating order preservation, and adjusting temperature dynamically.

read the caption

(e) Components in Matching Strategy

🔼 This figure shows the ablation study results on the impact of the reinforcement step (RS) training iterations on the performance of VLSI. It compares the model’s performance across various settings: using only the interaction step without RS, and using RS with 50% and 100% of the total training iterations. The results demonstrate the impact of adding the RS, which further enhances the VLSI model’s performance on various vision-language benchmarks.

read the caption

(c) Percentage of Training Iterations in RS

🔼 This figure details the architecture of the verbalizer module used in the VLSI model. The verbalizer is a crucial component of VLSI’s layer-wise distillation process. It projects intermediate layer features from both the large and small backbone VLMs into a natural language space. This allows for a flexible alignment between the reasoning processes of these models of differing sizes, improving efficiency and accuracy without the need for scaling or architectural changes. The verbalizer is comprised of a feed-forward network (verb-FFN) and a language head, facilitating a text-based output.

read the caption

(f) Verbalizer Architecture

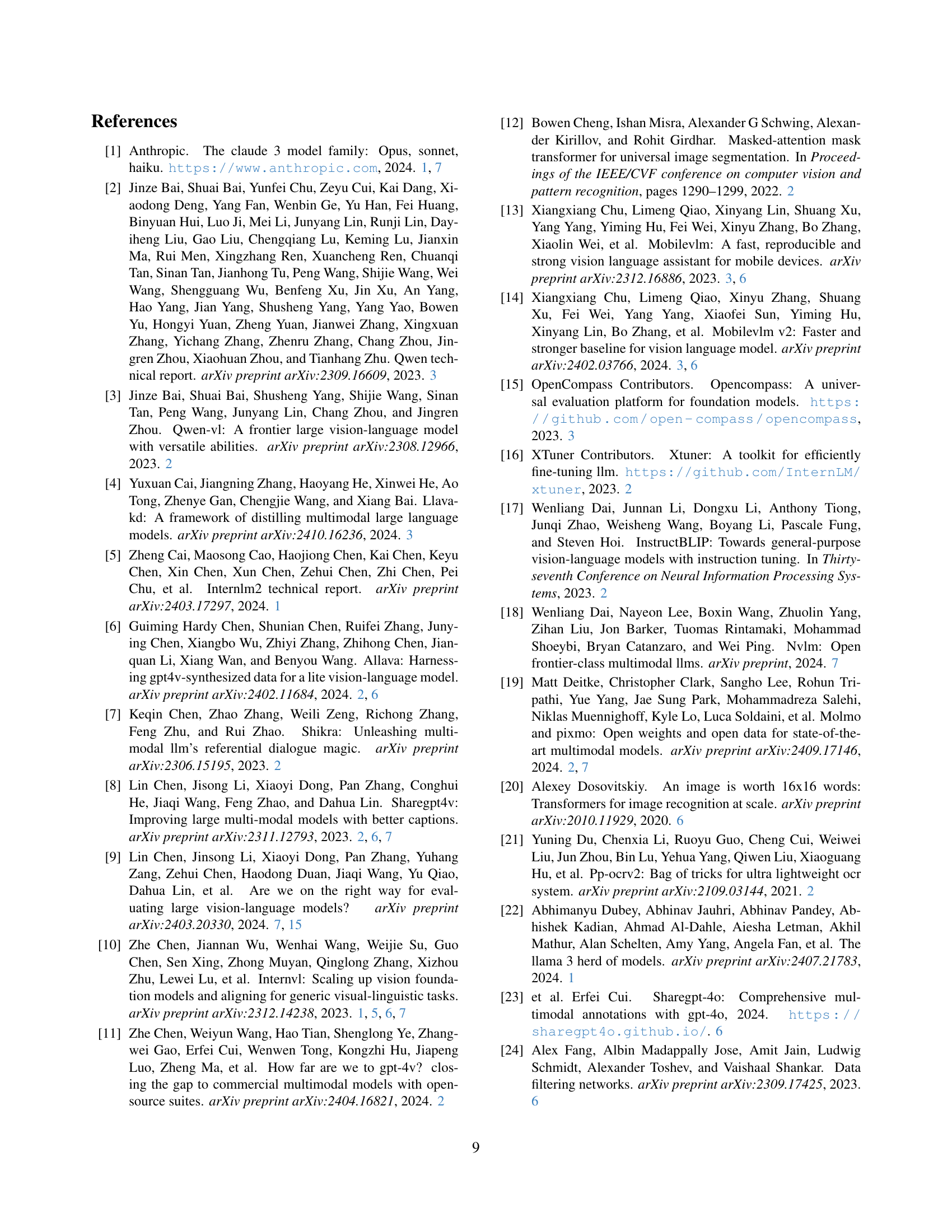

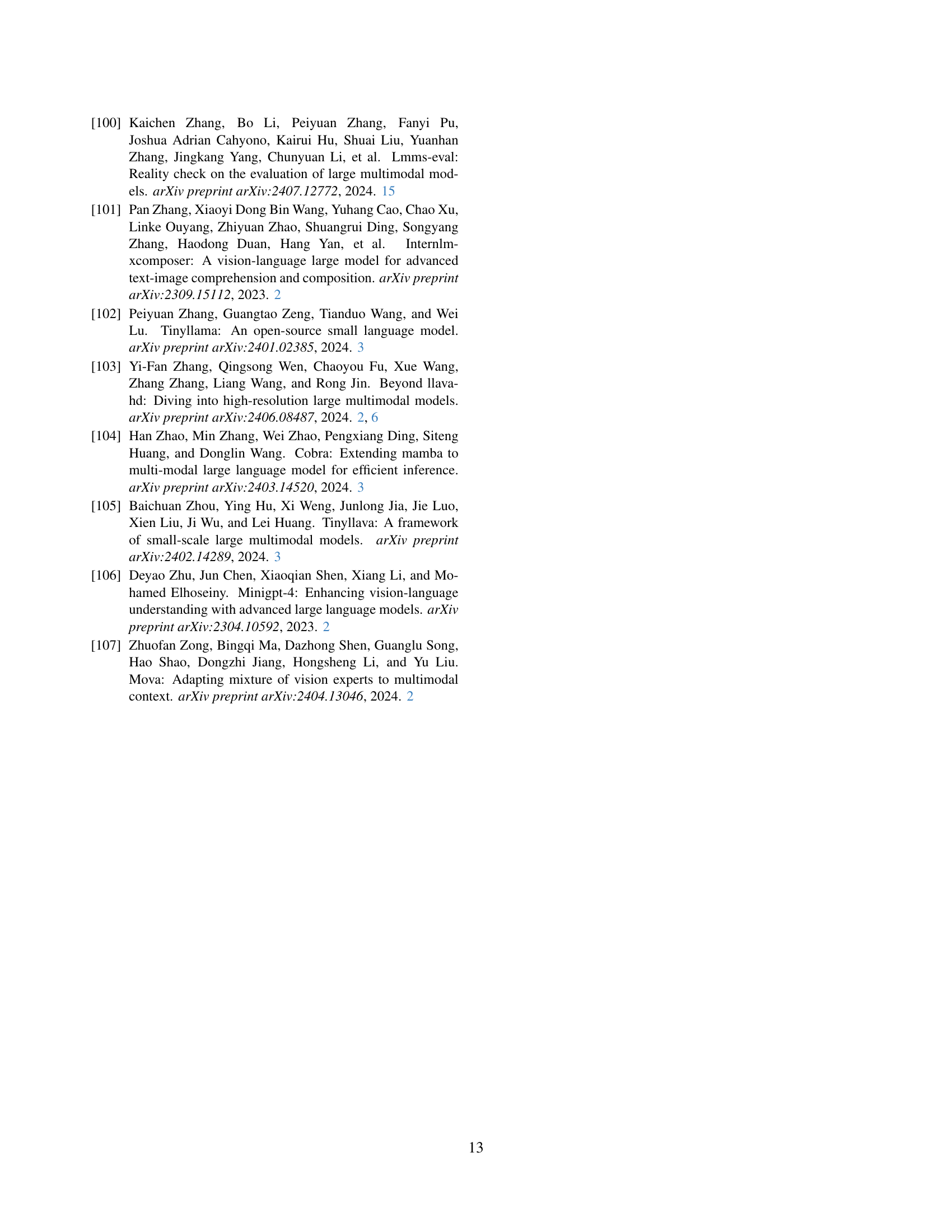

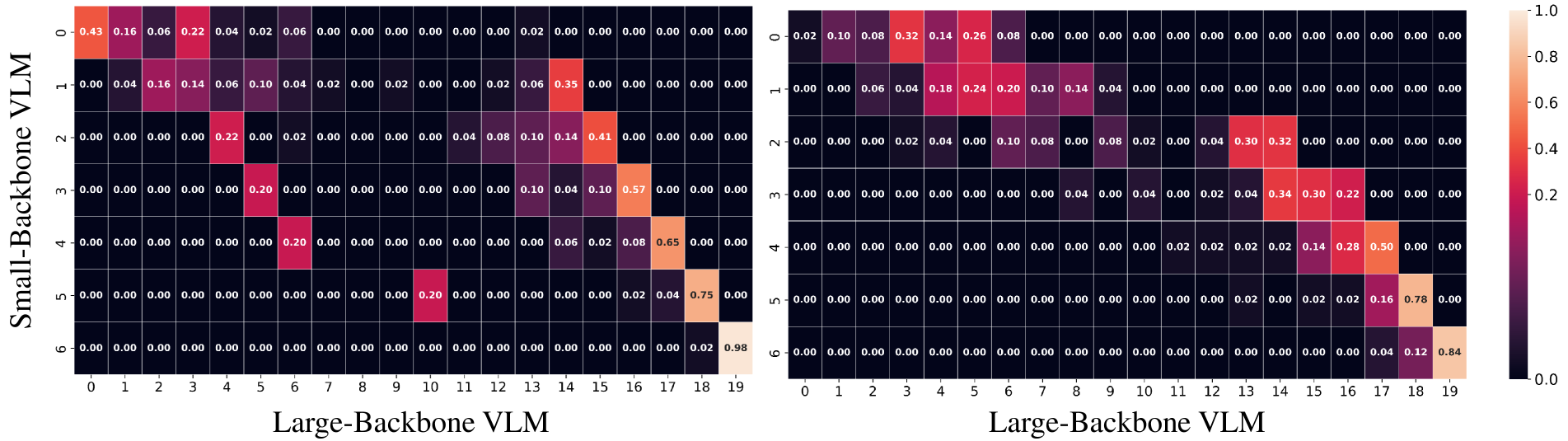

🔼 This figure visualizes how the alignment between layers of small and large Vision Language Models (VLMs) evolves during the interaction step of the VLSI training process. The heatmaps represent the distribution of matched indices between layers. The left heatmap shows this distribution at the training’s start, while the right one displays it at the end. A change in distribution indicates that the smaller VLM is learning to align its layer-wise reasoning process with that of the larger VLM throughout training.

read the caption

Figure 5: Distribution changes of the matched indices between small-backbone and large-backbone VLMs at the interaction step. The left figure shows the distribution at the beginning of training, while the right figure shows it at the end.

More on tables

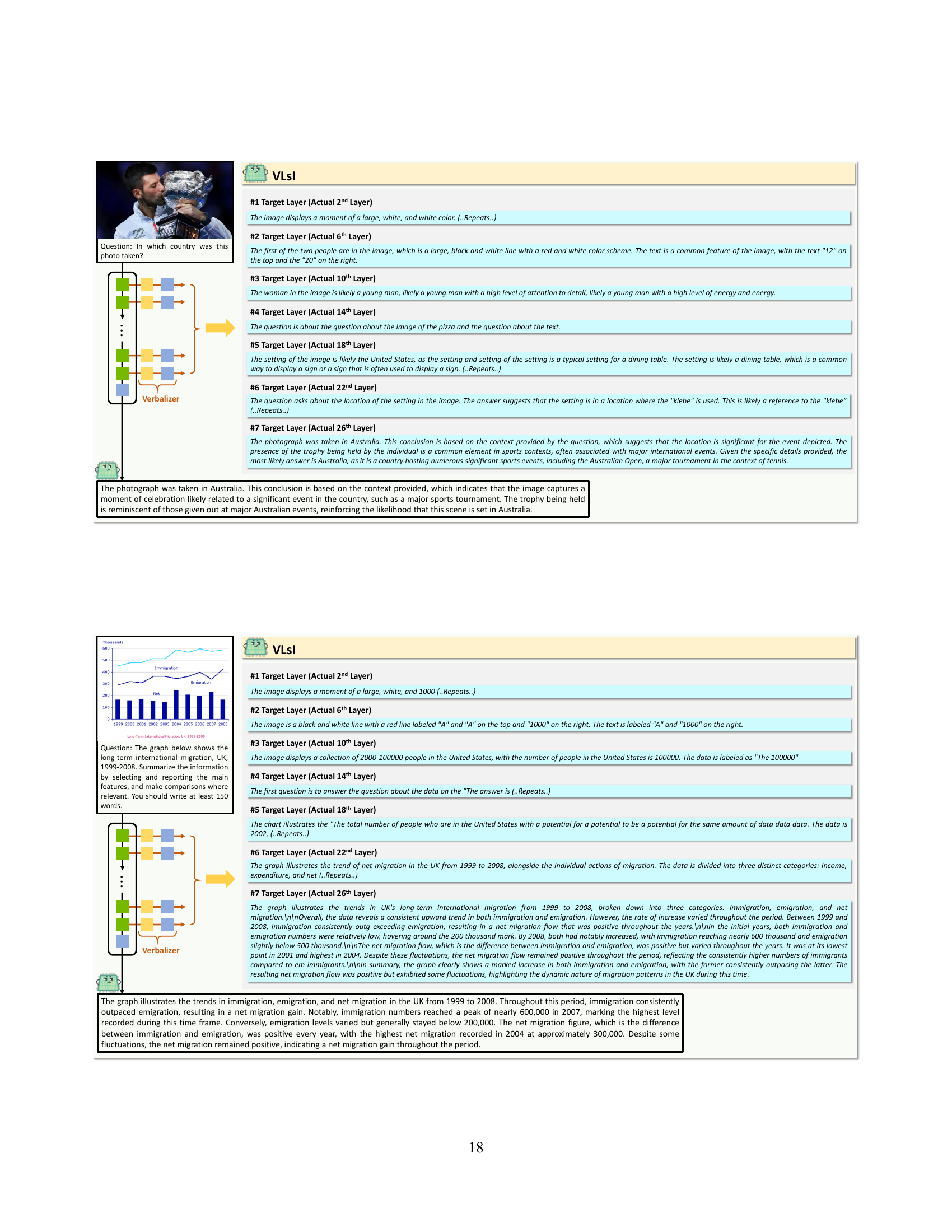

| VLMs | QBench | AI2D | ChartQA | POPE | HallB | MME | MathVista | MMB | MMBCN | MM-Vet | MMMU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiniCPM-2.4B [38] | - | 56.3 | - | - | - | 1650 | 28.9 | 64.1 | 62.6 | 31.1 | - | |

| MiniCPM-V2-2.8B [38] | - | 62.9 | - | - | - | 1809 | 38.7 | 69.1 | 66.5 | 41.0 | - | |

| MM1-3B [69] | - | - | - | 87.4 | - | 1762 | 32.0 | 67.8 | - | 43.7 | 33.9 | |

| MM1-MoE-3B64 [69] | - | - | - | 87.6 | - | 1773 | 32.6 | 70.8 | - | 42.2 | 38.6 | |

| ALLaVA-3B [6] | - | - | - | - | - | 1623 | - | 64.0 | - | 32.2 | 35.3 | |

| VILA1.5-3B [6] | - | - | - | 85.3 | - | - | - | 62.8 | 52.2 | 38.6 | 33.3 | |

| InternVL2-4B [10] | - | 78.9 | 81.5 | - | - | 2064 | 58.6 | 78.6 | 73.9 | 51.0 | 34.3 | |

| TroL-3.8B [46] | 70.0 | 73.6 | 73.8 | 86.5 | 62.2 | 1980 | 55.1 | 79.2 | 77.1 | 51.1 | 37.5 | |

| Phantom-3.8B [45] | 70.3 | 71.7 | 87.3 | 87.1 | 60.8 | 2046 | 60.6 | 80.4 | 77.1 | 54.4 | 39.2 | |

| DeepSeek-VL-1.3B [65] | - | - | - | 87.6 | - | - | 31.1 | 64.6 | 62.9 | 34.8 | 32.2 | |

| MobileVLM-1.7B [13] | - | - | - | 84.5 | - | - | - | 53.2 | - | - | - | |

| MobileVLM-V2-1.7B [14] | - | - | - | 84.3 | - | - | - | 57.7 | - | - | - | |

| MoE-LLaVA-1.8B4 [57] | - | - | - | 87.0 | - | - | - | 59.7 | - | 25.3 | - | |

| Mini-Gemini-2B [56] | - | - | - | - | - | 1653 | 29.4 | 59.8 | - | - | 31.7 | |

| InternVL2-2B [10] | - | 74.1 | 76.2 | - | - | 1877 | 46.3 | 73.2 | 70.9 | 39.5 | 34.3 | |

| TroL-1.8B [46] | 68.2 | 68.9 | 64.0 | 88.6 | 60.1 | 2038 | 45.4 | 76.1 | 74.1 | 45.1 | 35.2 | |

| Phantom-1.8B [45] | 69.1 | 62.3 | 87.0 | 89.6 | 62.2 | 1885 | 60.9 | 76.6 | 75.1 | 54.1 | 40.6 | |

| Qwen2-VL-2B [87] | 70.8 | 60.2 | 73.5 | 87.8 | 61.2 | 1872 | 43.0 | 74.9 | 73.5 | 49.5 | 41.1 | |

| VLSI-2B | 72.3 | 89.0 | 85.8 | 87.9 | 70.0 | 2022 | 68.4 | 81.7 | 78.8 | 64.8 | 51.4 |

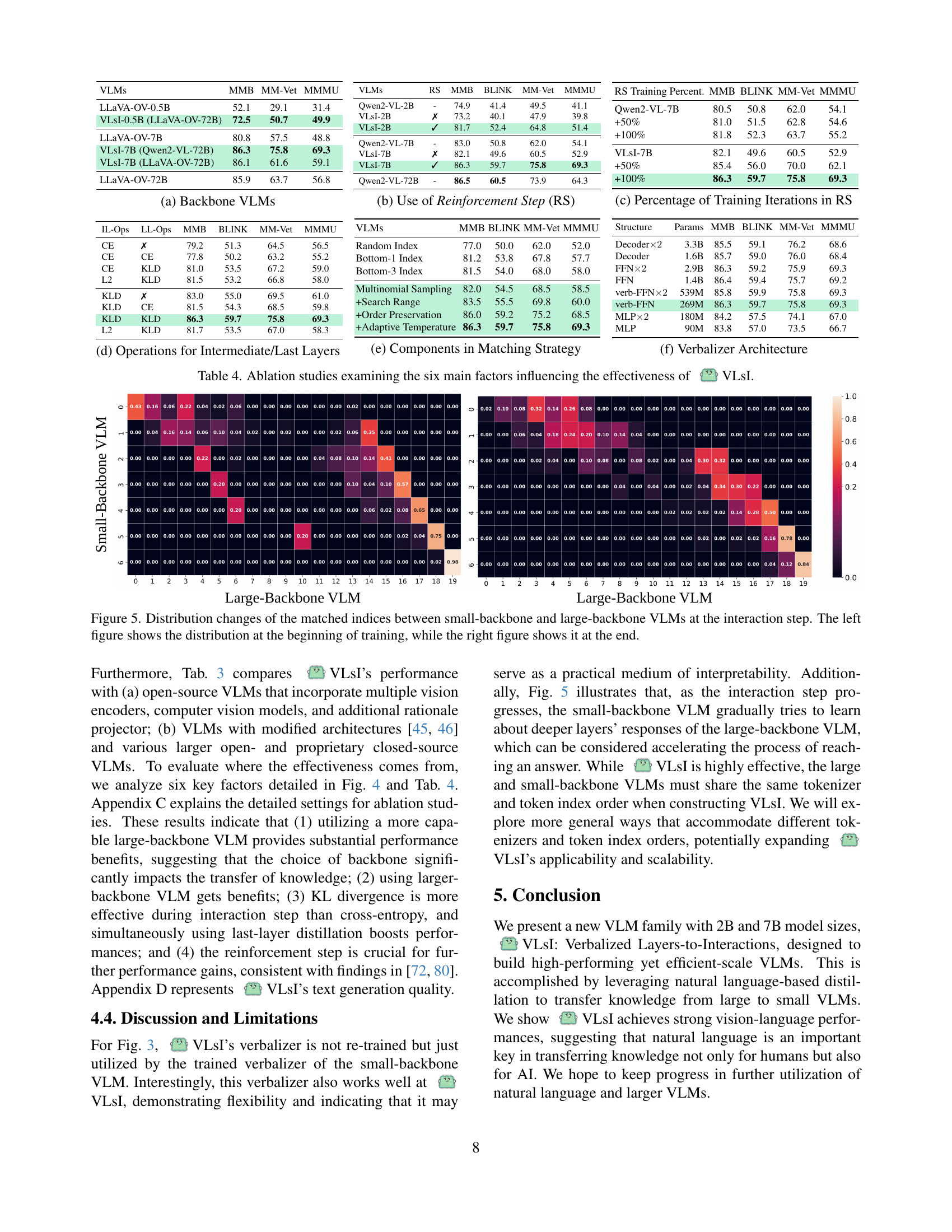

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of various smaller open-source vision-language models (VLMs) and the proposed VLSI model on a set of common vision-language benchmarks. It allows for a direct comparison of VLSI’s performance against existing open-source models of similar scale, highlighting its efficiency and accuracy in handling a variety of vision-language tasks. The benchmarks used are the same as those in Table 1, enabling a consistent evaluation across model sizes and architectures.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of smaller open-source VLMs and VLsI on the same evaluation benchmarks as in Table 1.

| Benchmarks | OmniFusion-7B | DeepSeek-VL-7B | MoVA-7B | Eagle-8B | CoLLaVO-7B | MoAI-7B | Meteor-7B | VLsI-2B | VLsI-7B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMB [62] | 69.0 | 73.2 | 81.3 | 75.9 | 83.0 | 79.3 | 82.9 | 81.7 | 86.3 |

| MathVista [66] | - | - | 44.3 | 52.7 | 57.6 | 56.2 | 53.4 | 68.4 | 74.7 |

| MM-Vet [94] | 39.4 | 41.5 | - | - | 40.3 | 43.7 | 57.3 | 64.8 | 70.8 |

| MMMU [96] | 36.6 | 36.6 | - | 43.8 | 42.2 | 45.6 | 48.3 | 51.4 | 69.3 |

🔼 Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of various open-source Vision-Language Models (VLMs) on the MM-Vet and MMMU benchmarks. It contrasts the performance of VLMs enhanced with additional modules and projectors against the performance of VLSI. The models compared against VLSI include OmniFusion, DeepSeek-VL, MoVA, Eagle, CoLLaVO, MoAI, and Meteor. This allows for an assessment of VLSI’s performance relative to existing state-of-the-art methods that utilize specialized modules or architectures.

read the caption

(a) Validation of open-source VLMs with additional modules and projectors compared to VLsI: OmniFusion [32], DeepSeek-VL [65], MoVA [40], Eagle [77], CoLLaVO [48], MoAI [49], and Meteor [47].

| VLMs | MM-Vet | MM-Vet-v2 | MMMU | MMStar | AI2D | SEED-2-Plus | MathVista | BLINK | CV-Bench | LLaVA-Wilder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLaVA-NeXT-34B [61] | 50.7 | 50.9 | 48.8 | 51.6 | 78.9 | 65.9 | 40.4 | - | - | - |

| VILA1.5-40B [58] | 51.2 | - | 55.1 | 55.2 | 77.8 | - | 49.5 | - | - | - |

| Cambrian-34B [84] | 53.2 | - | 50.4 | 54.2 | 79.5 | 65.1 | 50.3 | - | 76.9 | - |

| Molmo-72B [19] | 61.1 | - | 52.8 | 63.3 | 83.4 | - | 55.8 | - | - | - |

| LLaVA-OV-72B [52] | 60.6 | - | 56.6 | 65.8 | 86.2 | - | 68.4 | - | - | 72.0 |

| LLaMA-3.2-Vision | 64.1 | - | 60.3 | 55.3 | 69.5 | 68.2 | 58.3 | 48.0 | - | - |

| Claude3.5-Sonnet [1] | 66.0 | 71.8 | 65.9 | 62.2 | 80.2 | 71.7 | 61.6 | 28.2 | - | 83.1 |

| NVLM-D-72B [18] | 58.9 | - | 60.8 | 63.7 | 80.1 | 68.4 | 63.9 | 48.0 | - | - |

| GPT-4V (0409) [8] | 67.5 | 66.3 | 61.7 | 56.0 | 78.6 | 69.3 | 54.7 | 58.3 | 69.1 | 71.5 |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro | 64.0 | 66.9 | 60.6 | 59.1 | 79.1 | 70.8 | 57.7 | 59.1 | - | - |

| InternVL2-76B [10] | 64.4 | 68.4 | 58.3 | 67.1 | 87.6 | 70.0 | 65.6 | 57.5 | - | - |

| GPT-4o (0806) | 75.1 | 71.0 | 69.9 | 64.7 | 84.7 | 70.8 | 62.7 | 64.7 | - | 85.9 |

| Qwen2-VL-72B [87] | 73.9 | 68.7 | 64.3 | 68.6 | 88.3 | 72.3 | 69.7 | 60.5 | 74.3 | 84.1 |

| TroL-1.8B [46] | 45.1 | - | 35.2 | 45.5 | 68.9 | - | 45.4 | - | - | - |

| TroL-7B [46] | 54.7 | - | 49.9 | 51.3 | 78.5 | - | 51.8 | - | - | - |

| Phantom-1.8B [45] | 54.1 | 46.3 | 40.6 | 45.5 | 62.3 | 57.1 | 60.9 | 44.2 | 63.1 | 78.5 |

| Phantom-7B [45] | 70.8 | 60.6 | 51.2 | 57.3 | 79.5 | 65.5 | 70.9 | 58.9 | 74.9 | 82.9 |

| 64.8 | 60.8 | 51.4 | 76.6 | 89.0 | 81.1 | 68.4 | 52.4 | 90.1 | 90.1 |

| 75.8 | 70.0 | 69.3 | 73.6 | 87.3 | 74.9 | 74.7 | 59.7 | 89.1 | 92.0 |

🔼 Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of VLSI’s performance against other prominent Vision-Language Models (VLMs), both open-source and closed-source, across a range of challenging benchmarks. These benchmarks assess diverse capabilities, including visual and reasoning skills. The models compared include those enhanced with additional knowledge modules and larger models with greater parameter counts, offering a comprehensive overview of VLSI’s performance in relation to state-of-the-art systems.

read the caption

(b) Comparison of VLsI with other open-source and closed-source VLMs on challenging benchmarks: MM-Vet [94], MM-Vet-v2 [95], MMMU [96], MMStar [9], AI2D [41], SEED-2-Plus [51], MathVista [66], BLINK [29], CV-Bench [84], and LLaVA-Wilder [52]. This comparison includes models embedding additional knowledge [46, 45] and larger open/closed-source VLMs.

| VLMs | MMB | MM-Vet | MMMU |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLaVA-OV-0.5B | 52.1 | 29.1 | 31.4 |

| VLsI-0.5B (LLaVA-OV-72B) | 72.5 | 50.7 | 49.9 |

| LLaVA-OV-7B | 80.8 | 57.5 | 48.8 |

| VLsI-7B (Qwen2-VL-72B) | 86.3 | 75.8 | 69.3 |

| VLsI-7B (LLaVA-OV-72B) | 86.1 | 61.6 | 59.1 |

| LLaVA-OV-72B | 85.9 | 63.7 | 56.8 |

🔼 Table 3 presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed VLSI model against a range of open-source and closed-source Vision-Language Models (VLMs) across a set of challenging evaluation benchmarks. The table highlights VLSI’s performance relative to these other models, showcasing its strengths and weaknesses on different tasks. The specific benchmarks used are detailed in Appendix A of the paper for readers seeking further information on the nature of the individual evaluation tasks.

read the caption

Table 3: Detailed comparison of VLsI with various open and closed-source VLMs on challenging evaluation benchmarks. Appendix A provides detailed descriptions of the evaluation benchmarks listed in Tables 1 and 2.

| IL-Ops | LL-Ops | MMB | BLINK | MM-Vet | MMMU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE | ✗ | 79.2 | 51.3 | 64.5 | 56.5 |

| CE | CE | 77.8 | 50.2 | 63.2 | 55.2 |

| CE | KLD | 81.0 | 53.5 | 67.2 | 59.0 |

| L2 | KLD | 81.5 | 53.2 | 66.8 | 58.0 |

| KLD | ✗ | 83.0 | 55.0 | 69.5 | 61.0 |

| KLD | CE | 81.5 | 54.3 | 68.5 | 59.8 |

| KLD | KLD | 86.3 | 59.7 | 75.8 | 69.3 |

| L2 | KLD | 81.7 | 53.5 | 67.0 | 58.3 |

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of six key factors on the performance of the VLSI model. The factors investigated include the choice of backbone Vision-Language Model (VLM), the inclusion of a reinforcement step in the training process, the percentage of training iterations dedicated to the reinforcement step, the type of operations used for intermediate and last layers, the components of the layer matching strategy, and the architecture of the verbalizer. Each row represents a different experimental setup modifying one or more of these factors, while the columns display the resulting performance metrics on the MM-Vet and MMMU benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation studies examining the six main factors influencing the effectiveness of VLsI.

Full paper#