↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Process Reward Models (PRMs) offer superior performance in various AI applications by providing denser feedback during training, but their development is hindered by the high cost and effort of step-level data annotation. Existing methods for automatic annotation, such as Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), incur excessive computational overhead and produce noisy annotations, thereby limiting the scalability of PRMs.

This paper introduces a novel approach to efficiently train PRMs by utilizing readily available response-level labels. The core idea lies in parameterizing the reward function as a log-likelihood ratio of policy and reference models. The method is shown to implicitly learn a strong PRM using only this cheaper outcome data, eliminating the need for additional step-level annotations. Experiments demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms strong baselines on a challenging mathematical reasoning task, with substantial improvements in data efficiency and training cost.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it significantly reduces the cost and effort of training process reward models (PRMs), a critical advancement for various AI applications. Its novel approach makes PRM training accessible to a broader research community and enables further investigation into more complex AI tasks. The findings challenge existing assumptions about PRM training, opening up new avenues of research and potential breakthroughs in areas such as reinforcement learning and decision-making. The method is particularly beneficial for scenarios with scarce data, making high-quality PRMs accessible for a wider range of tasks and datasets.

Visual Insights#

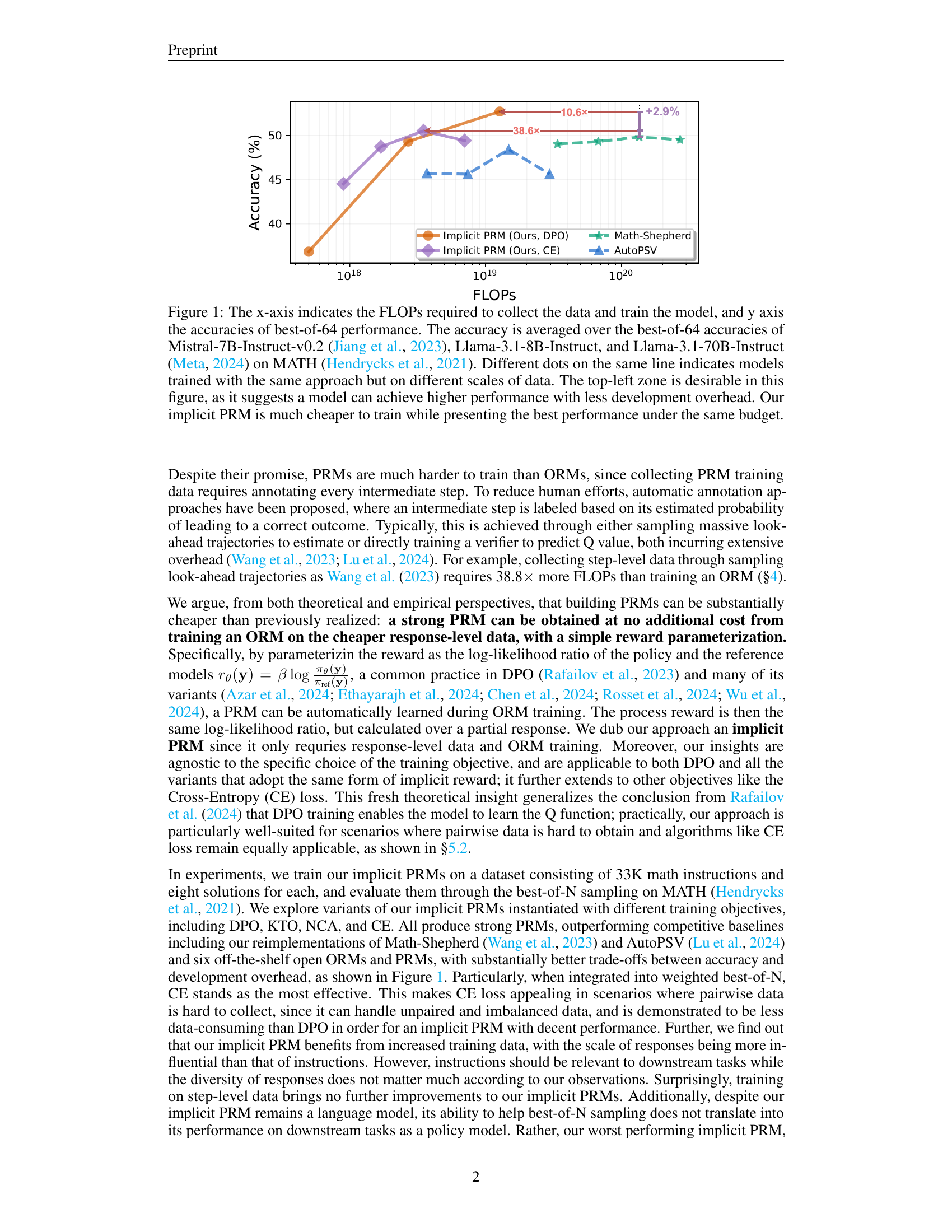

🔼 This figure compares different reward models based on their training cost (FLOPs) and performance (best-of-64 accuracy on the MATH dataset). The performance is averaged across three different language models: Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, and Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct. Each point on a line represents a model trained with the same method but with a different amount of training data. The ideal model would be located in the top-left corner, indicating high accuracy with low training cost. The results show that the proposed ‘implicit PRM’ achieves the best accuracy while having significantly lower training costs compared to other methods.

read the caption

Figure 1: The x-axis indicates the FLOPs required to collect the data and train the model, and y axis the accuracies of best-of-64 performance. The accuracy is averaged over the best-of-64 accuracies of Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 (Jiang et al., 2023), Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, and Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct (Meta, 2024) on MATH (Hendrycks et al., 2021). Different dots on the same line indicates models trained with the same approach but on different scales of data. The top-left zone is desirable in this figure, as it suggests a model can achieve higher performance with less development overhead. Our implicit PRM is much cheaper to train while presenting the best performance under the same budget.

| Type | Reward Model | Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2 | Llama-3.1-8B-Inst | Llama-3.1-70B-Inst | Avg. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pass@1: 9.6 | @4 | @16 | @64 | Pass@1: 44.6 | @4 | @16 | Pass@1: 63.2 | @4 | @16 | ||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| ORM | EurusRM-7B | 17.2 | 21.0 | 20.4 | 49.6 | 51.6 | 51.8 | 69.0 | 69.6 | 72.2 | 46.9 |

| SkyworkRM-Llama3.1-8B | 16.0 | 19.6 | 23.4 | 49.0 | 50.4 | 48.2 | 70.4 | 72.6 | 72.0 | 46.8 | |

| ArmoRM-Llama3-8B | 16.6 | 21.0 | 23.2 | 47.8 | 48.6 | 49.4 | 70.6 | 70.8 | 71.0 | 46.6 | |

| PRM | Math-Shepherd-7B | 16.0 | 21.0 | 20.4 | 50.0 | 52.4 | 52.8 | 66.4 | 65.8 | 65.6 | 45.6 |

| RLHFlow-8B-Mistral-Data | 19.4 | 25.2 | 30.2 | 51.8 | 52.0 | 50.6 | 70.8 | 71.0 | 71.2 | 49.1 | |

| RLHFlow-8B-DS-Data | 17.2 | 23.0 | 25.2 | 54.4 | 54.2 | 55.8 | 68.6 | 70.4 | 73.0 | 49.1 | |

| Baselines | Math-Shepherd | 17.6 | 24.4 | 26.8 | 50.0 | 51.4 | 52.8 | 68.6 | 69.4 | 68.8 | 47.8 |

| AutoPSV | 16.6 | 20.6 | 22.2 | 52.2 | 51.4 | 52.2 | 68.4 | 65.4 | 62.4 | 45.7 | |

| Implicit PRM | DPO | 18.6 | 24.4 | 28.8 | 54.0 | 55.4 | 57.0 | 71.8 | 71.2 | 72.2 | 50.4 |

| KTO | 15.6 | 18.4 | 18.6 | 49.6 | 51.8 | 50.8 | 72.6 | 67.0 | 67.2 | 45.7 | |

| NCA | 18.6 | 23.8 | 28.0 | 52.4 | 53.4 | 55.2 | 69.0 | 73.0 | 71.6 | 49.4 | |

| CE | 18.8 | 24.0 | 28.0 | 52.6 | 54.4 | 53.0 | 70.6 | 67.0 | 67.2 | 48.4 | |

| CE (Dataset-wise Balanced) | 18.0 | 23.6 | 27.0 | 52.6 | 54.2 | 52.6 | 68.6 | 66.8 | 67.0 | 47.8 | |

| CE (Inst.-wise Balanced) | 17.6 | 22.6 | 26.2 | 52.6 | 55.2 | 54.6 | 69.4 | 71.2 | 72.0 | 49.0 |

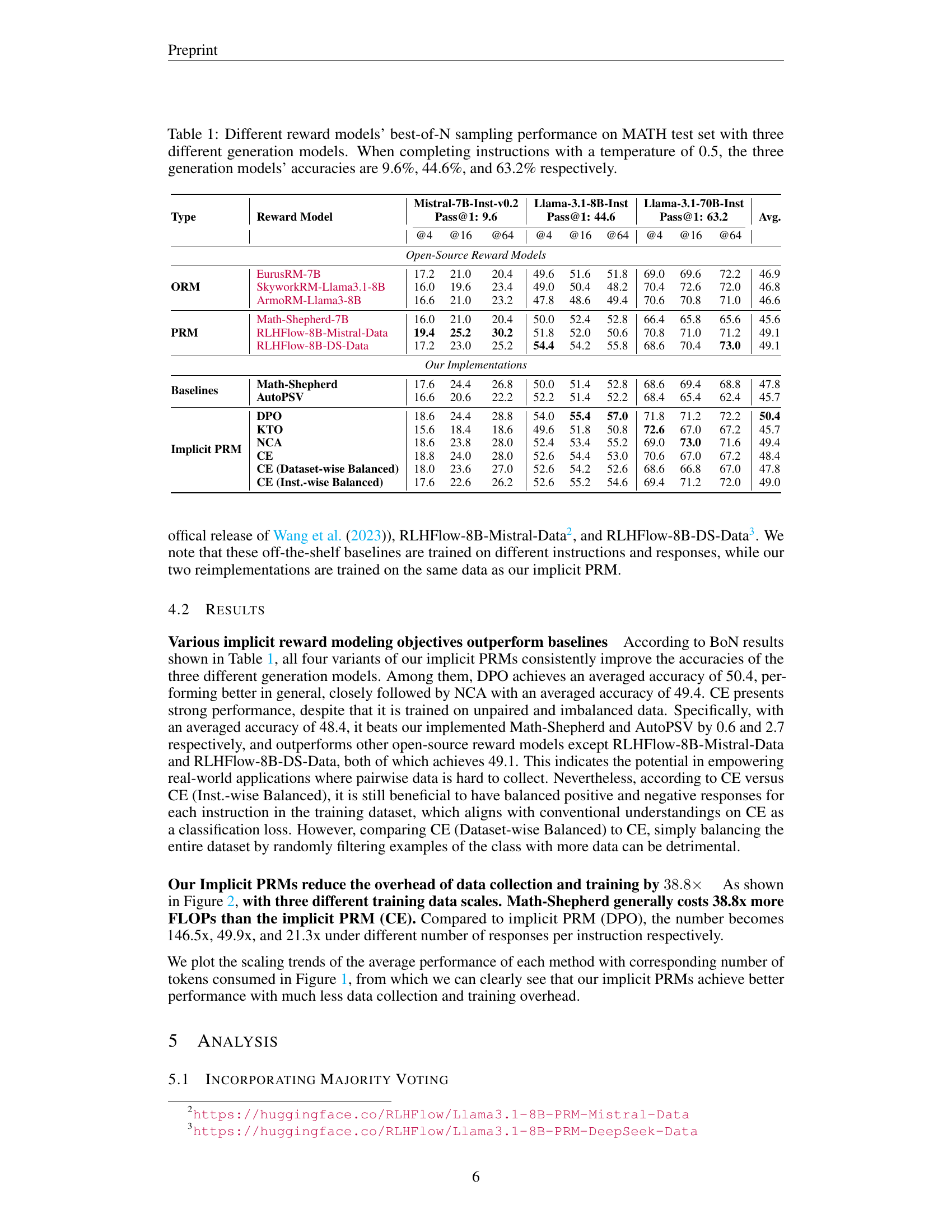

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various reward models’ performance on the MATH dataset, using best-of-N sampling. Three different large language models (LLMs) were used as generation models: Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Inst, and Llama-3.1-70B-Inst. The models’ individual pass@1 accuracies (when completing instructions with a temperature of 0.5) are shown in the caption (9.6%, 44.6%, and 63.2% respectively). The table shows the performance (pass@k, where k = 4, 16, and 64) of different reward models, categorized as outcome reward models (ORMs) and process reward models (PRMs), including both open-source and custom-implemented models. The goal is to evaluate the effectiveness of various reward models in improving the accuracy of the LLMs during best-of-N sampling.

read the caption

Table 1: Different reward models’ best-of-N sampling performance on MATH test set with three different generation models. When completing instructions with a temperature of 0.5, the three generation models’ accuracies are 9.6%, 44.6%, and 63.2% respectively.

In-depth insights#

Implicit PRM Training#

Implicit PRM training offers a groundbreaking approach to process reward model (PRM) development by eliminating the need for costly and time-consuming step-level annotations. Instead of directly training a PRM on meticulously labeled intermediate steps, this method cleverly leverages the readily available response-level labels from outcome reward model (ORM) training. The core idea is to parameterize the reward function as the log-likelihood ratio between a policy model and a reference model. This clever technique allows the ORM to implicitly learn a PRM during its training phase. This paradigm shift is particularly significant because it dramatically reduces the data requirements and computational burden associated with PRM training, making the technology significantly more accessible. The implied PRM’s performance is surprisingly competitive with, and even surpasses, explicitly trained PRMs that utilize computationally expensive methods like Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) for data augmentation. Furthermore, this approach’s inherent flexibility makes it adaptable to diverse loss functions, further enhancing its versatility and practicality. This innovative approach represents a major advancement in PRM training, promising to democratize access to this powerful technique for various applications.

Reward Parameterization#

Reward parameterization is a crucial aspect of reward modeling, particularly in the context of process reward models (PRMs). The choice of parameterization significantly impacts the model’s ability to learn and generalize effectively. A well-chosen parameterization can simplify the training process and lead to better performance, potentially avoiding the need for expensive step-level labels in the case of PRMs. This paper explores parameterizing the reward as the log-likelihood ratio of policy and reference models. This approach offers several advantages: it implicitly obtains a PRM at no additional cost, it’s objective-agnostic, applicable to various loss functions (e.g., DPO and CE), and theoretically avoids the noisy estimations associated with methods like MCTS. The choice of reference model is another key consideration, potentially impacting efficiency and performance. While the reference model can add inference cost, the authors demonstrate scenarios where it can be omitted without significant performance loss. Finally, the study of different reward parameterization choices (e.g., linear transformations of hidden states, generative logits) helps highlight the advantages of log-likelihood ratio parameterization for balancing efficiency and performance in PRM training.

Data Efficiency Gains#

The concept of ‘Data Efficiency Gains’ in the context of process reward models (PRMs) centers on reducing the substantial data requirements associated with training these models compared to outcome reward models (ORMs). Traditional PRM training demands labels for every intermediate step of a reasoning process, leading to significant annotation costs and limitations in scalability. The research likely explores methods to achieve comparable or improved performance with fewer labeled steps, perhaps by leveraging the information implicitly present in the ORM training data. This could involve sophisticated reward parameterization techniques, as suggested in some research, which enable the extraction of process-level feedback from full response-level feedback, effectively utilizing data more efficiently. The analysis would involve assessing the performance improvements achieved with reduced data under various objectives, evaluating the impact of different loss functions, and perhaps comparing against strong MCTS-based baselines. Ultimately, the goal is to demonstrate substantial data efficiency improvements while maintaining or exceeding the performance of conventional PRM training approaches, making PRM training more accessible and scalable for broader applications.

Majority Voting Boost#

The concept of a ‘Majority Voting Boost’ in the context of a process reward model (PRM) for enhancing large language model (LLM) performance is intriguing. It suggests that combining the individual predictions of multiple PRMs, possibly trained with different objectives or data subsets, and selecting the final prediction based on a majority vote could significantly improve accuracy. This approach leverages the collective wisdom of multiple models to mitigate individual weaknesses and biases. The effectiveness hinges on the diversity of the PRMs; if they all make similar mistakes, majority voting won’t help. Therefore, diverse training data, model architectures, or objective functions are crucial to realize the potential of this boost. An interesting point to explore would be the specific voting strategy employed: simple majority, weighted majority based on individual model performance, or more sophisticated ensemble methods. A further consideration is the computational cost associated with training and running multiple PRMs, and whether this increase is justified by the improvement in accuracy. The potential to optimize computational resources while maintaining the accuracy benefit of majority voting should also be investigated. Finally, a detailed analysis of the types of errors each PRM makes and how majority voting corrects these errors would provide a valuable understanding of this technique’s efficacy.

Limitations of PRMs#

Process Reward Models (PRMs), while offering advantages over Outcome Reward Models (ORMs) by providing finer-grained feedback, suffer from significant limitations. Data acquisition for PRMs is substantially more expensive, requiring annotations for each intermediate reasoning step, unlike ORMs which only need final outcome labels. This makes large-scale PRM training challenging. The accuracy of automatically generated step-level labels, often relying on methods like Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), is questionable; noisy labels can negatively impact PRM performance. Furthermore, the effectiveness of PRMs is heavily dependent on the quality of the underlying language model used for generation, raising concerns about potential bias amplification and the difficulty in achieving reliable and consistent performance across diverse tasks. Finally, the increased computational cost during both training and inference due to the handling of multiple steps presents a practical hurdle for widespread adoption. Addressing these limitations is crucial for wider application of PRMs in complex reasoning tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

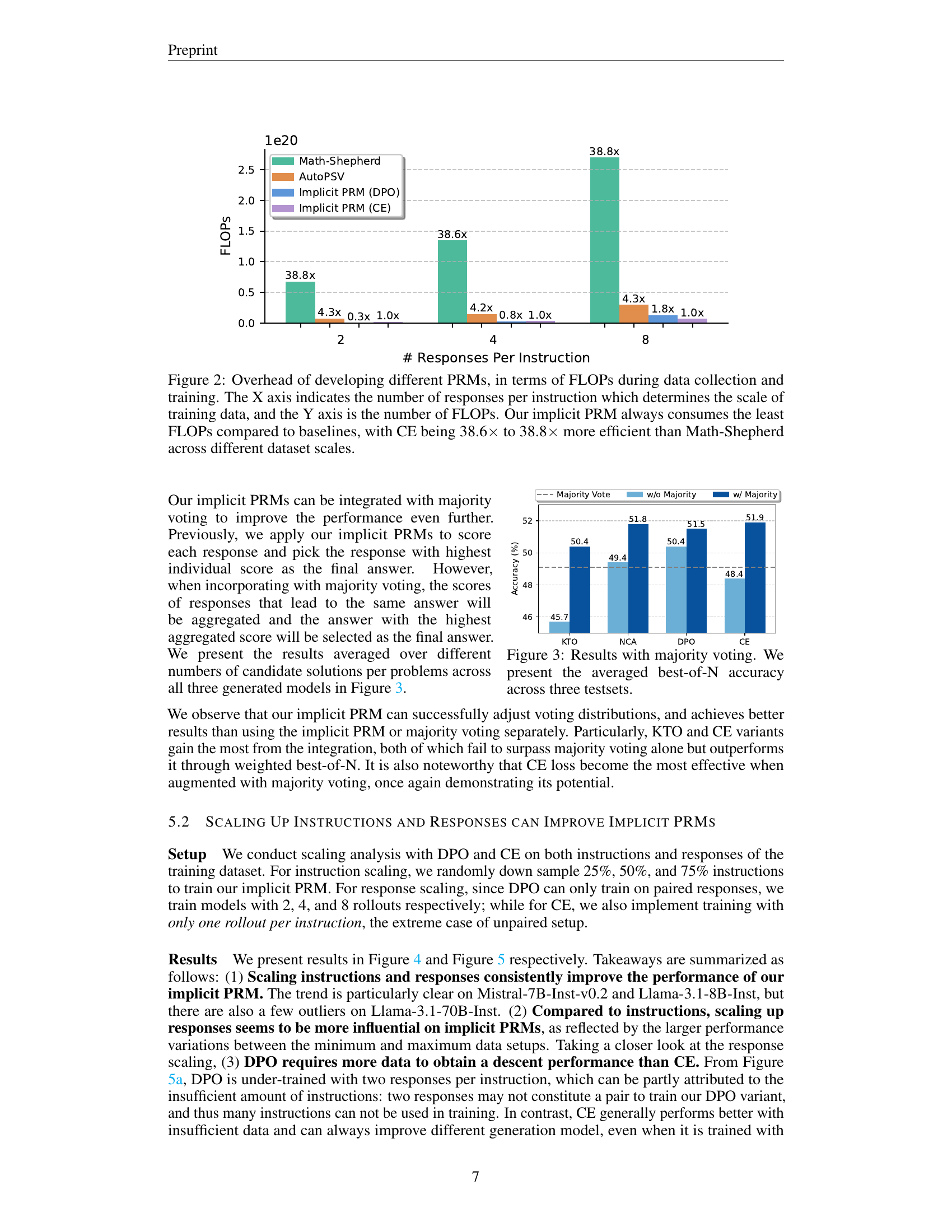

🔼 This figure illustrates the computational cost of training different process reward models (PRMs), comparing the proposed implicit PRM with existing methods. The x-axis represents the number of responses per instruction, which directly impacts the size of the training dataset. The y-axis displays the total FLOPs (floating-point operations) required for both data collection and model training. The figure demonstrates that the implicit PRM consistently requires significantly fewer FLOPs than other PRMs, highlighting its computational efficiency. Specifically, the implicit PRM using the cross-entropy (CE) loss function is shown to be 38.6 to 38.8 times more efficient than the Math-Shepherd method, showcasing a substantial reduction in computational resources.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overhead of developing different PRMs, in terms of FLOPs during data collection and training. The X axis indicates the number of responses per instruction which determines the scale of training data, and the Y axis is the number of FLOPs. Our implicit PRM always consumes the least FLOPs compared to baselines, with CE being 38.6×\times× to 38.8×\times× more efficient than Math-Shepherd across different dataset scales.

🔼 Figure 3 presents the average best-of-N accuracy across three different test sets (Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, and Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct) when using majority voting. The bar chart displays the performance improvement obtained by using majority voting to aggregate the scores of multiple model responses that lead to the same answer, compared to not using majority voting.

read the caption

Figure 3: Results with majority voting. We present the averaged best-of-N accuracy across three testsets.

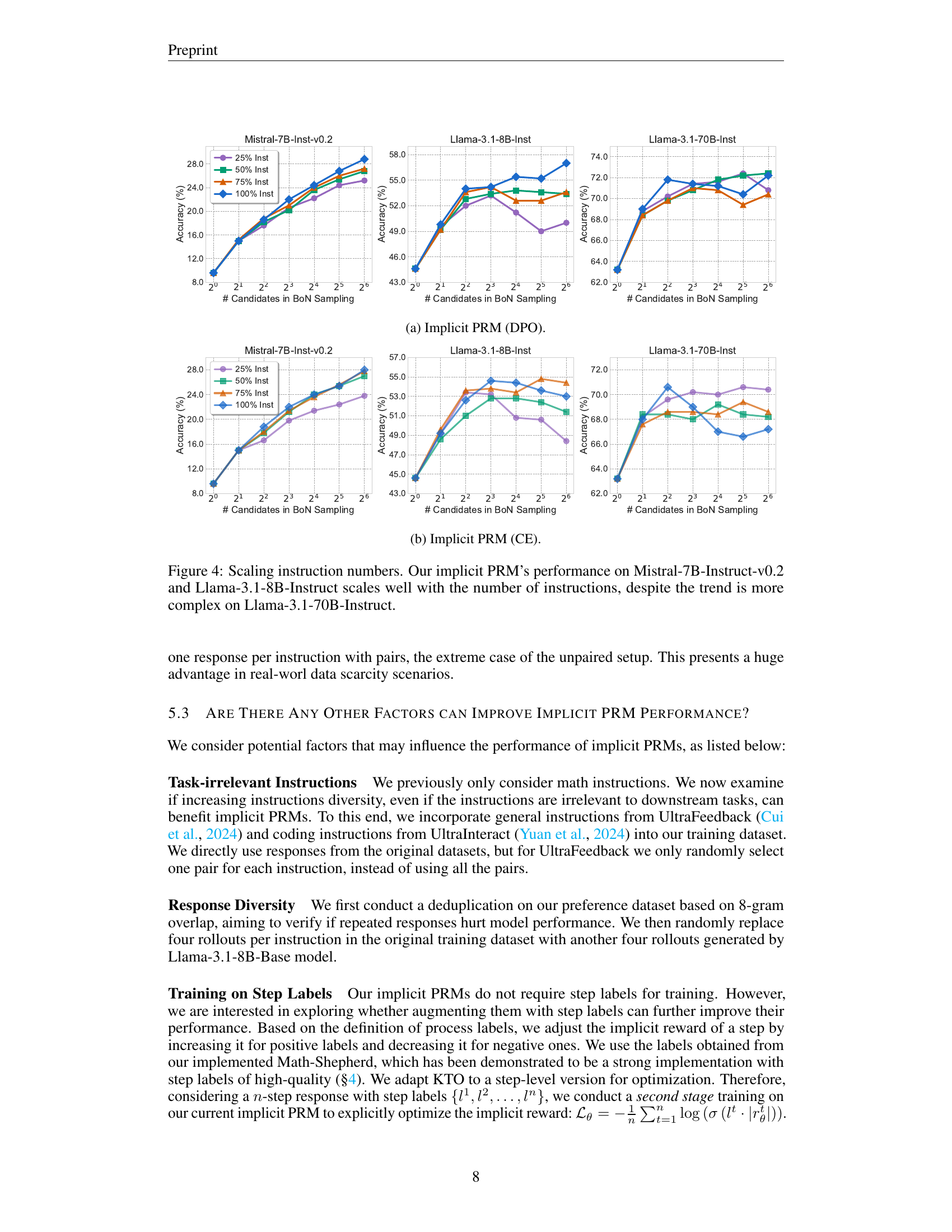

🔼 The figure shows the results of scaling up the number of instructions used to train an implicit PRM using the DPO objective. The x-axis represents the number of candidates considered in the best-of-N sampling, while the y-axis shows the accuracy. Different colored lines represent the performance of the implicit PRM trained on different proportions of the original instruction dataset (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%). The figure displays the results on three different generation models: Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Inst, and Llama-3.1-70B-Inst. It demonstrates how the performance of the implicit PRM scales with the amount of training data.

read the caption

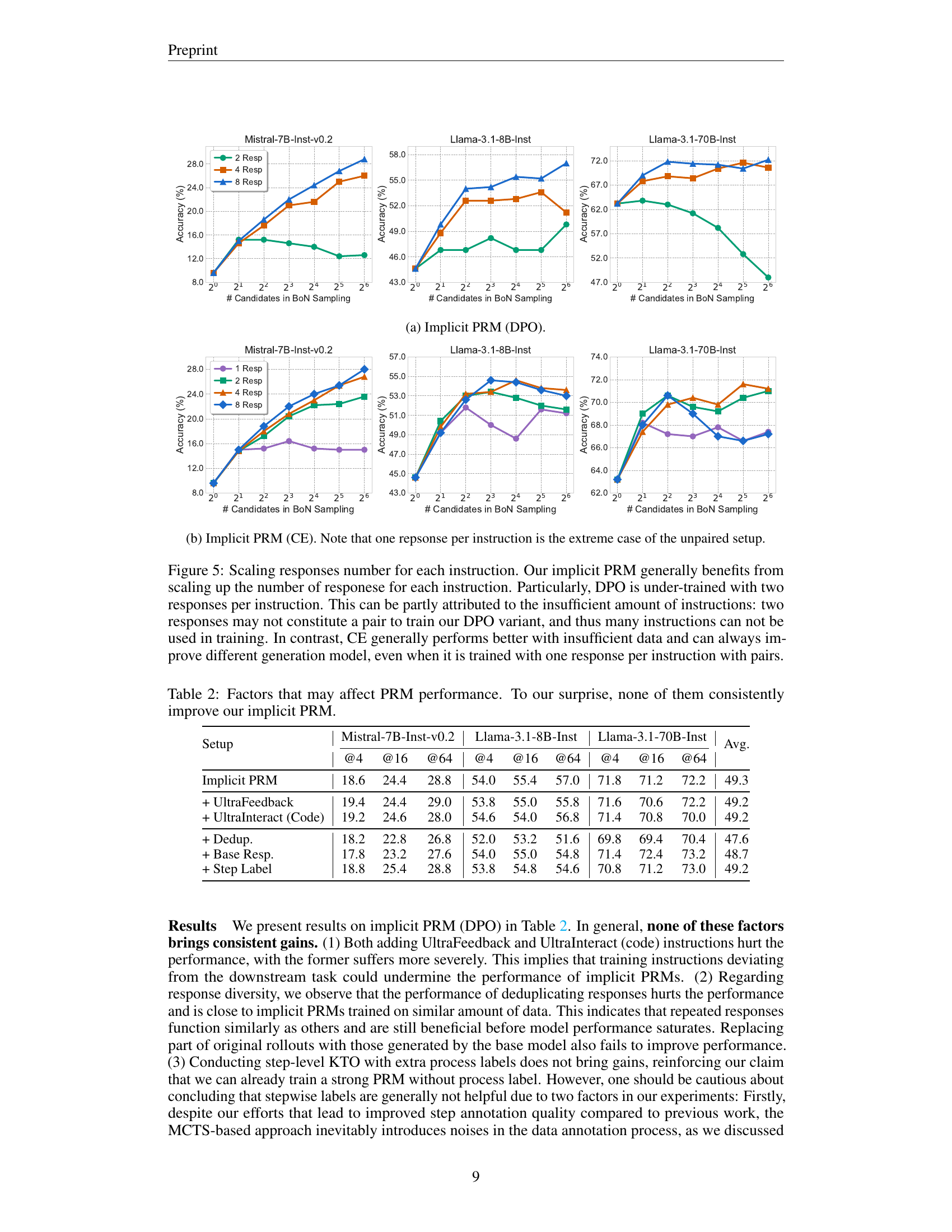

(a) Implicit PRM (DPO).

🔼 This figure shows the results of scaling the number of responses per instruction when training an Implicit PRM using the cross-entropy (CE) loss. It presents the best-of-N sampling performance on three different language models (Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Inst, Llama-3.1-70B-Inst) across various numbers of responses per instruction (1, 2, 4, 8). The x-axis represents the number of candidates considered in best-of-N sampling, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The figure illustrates how the model’s performance improves with more responses per instruction, showcasing the effect of data scaling on the Implicit PRM trained with CE loss.

read the caption

(b) Implicit PRM (CE).

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments on scaling the number of instructions used to train implicit PRMs. The x-axis represents the number of candidates considered in the best-of-N sampling process. The y-axis represents the accuracy achieved. Three different language models (Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, and Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct) were used. The results show that for Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, the performance of the implicit PRM generally improves as the number of training instructions increases. However, the trend is more complex and less consistent for Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct, highlighting potential differences in how these models benefit from increased training data.

read the caption

Figure 4: Scaling instruction numbers. Our implicit PRM’s performance on Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 and Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct scales well with the number of instructions, despite the trend is more complex on Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct.

🔼 The figure shows the result of scaling up the number of instructions for the Implicit PRM using the DPO objective. It presents the best-of-N sampling performance on three different language models: Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Inst, and Llama-3.1-70B-Inst. The x-axis shows the number of candidates considered in the best-of-N sampling, and the y-axis shows the accuracy. Different colored lines represent different scales of training data (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of the instructions). The figure demonstrates the effect of scaling instruction data on the performance of the Implicit PRM with DPO.

read the caption

(a) Implicit PRM (DPO).

More on tables

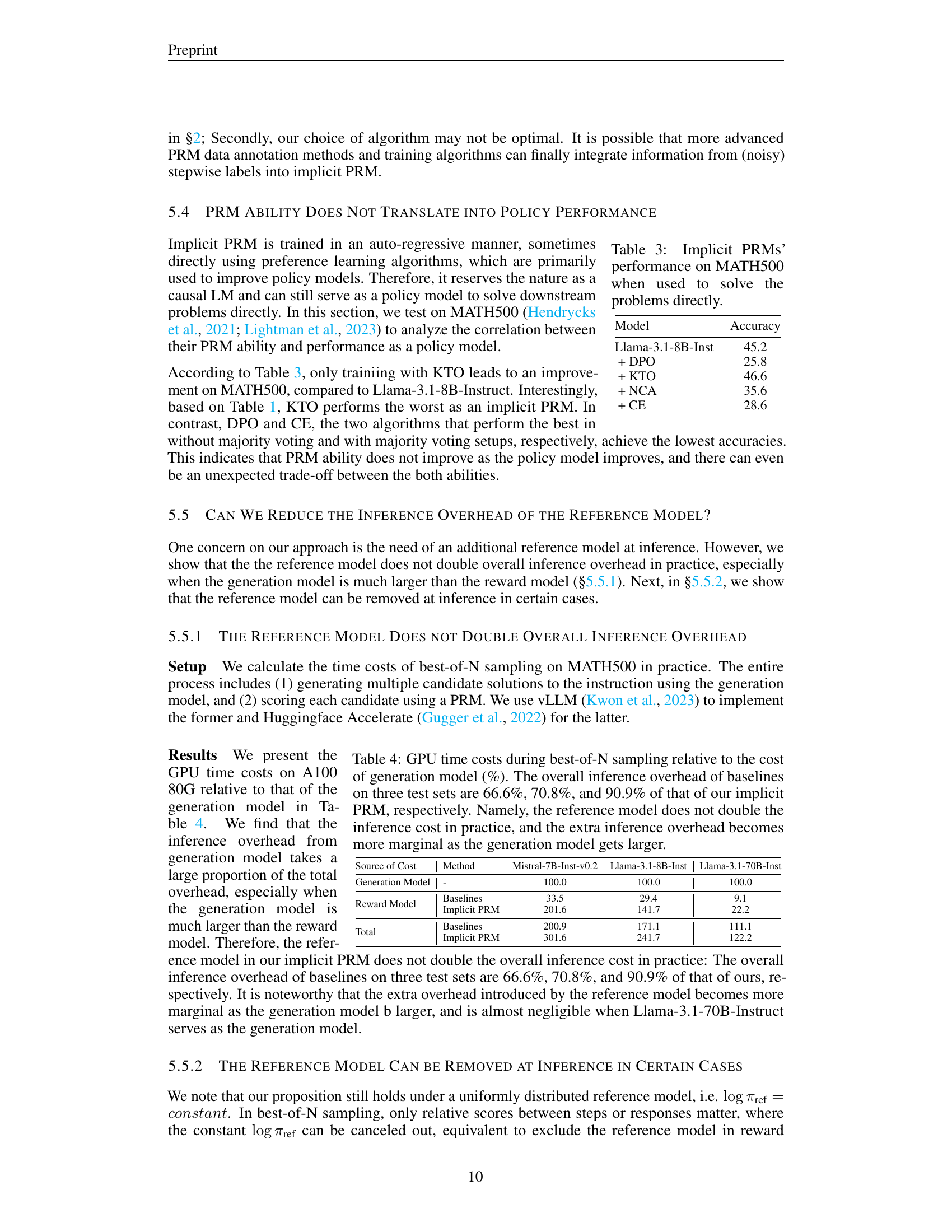

| Setup | Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2 | Llama-3.1-8B-Inst | Llama-3.1-70B-Inst | Avg. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| @4 | @16 | @64 | @4 | @16 | @64 | @4 | @16 | @64 | ||

| Implicit PRM | 18.6 | 24.4 | 28.8 | 54.0 | 55.4 | 57.0 | 71.8 | 71.2 | 72.2 | 49.3 |

| + UltraFeedback | 19.4 | 24.4 | 29.0 | 53.8 | 55.0 | 55.8 | 71.6 | 70.6 | 72.2 | 49.2 |

| + UltraInteract (Code) | 19.2 | 24.6 | 28.0 | 54.6 | 54.0 | 56.8 | 71.4 | 70.8 | 70.0 | 49.2 |

| + Dedup. | 18.2 | 22.8 | 26.8 | 52.0 | 53.2 | 51.6 | 69.8 | 69.4 | 70.4 | 47.6 |

| + Base Resp. | 17.8 | 23.2 | 27.6 | 54.0 | 55.0 | 54.8 | 71.4 | 72.4 | 73.2 | 48.7 |

| + Step Label | 18.8 | 25.4 | 28.8 | 53.8 | 54.8 | 54.6 | 70.8 | 71.2 | 73.0 | 49.2 |

🔼 Table 2 investigates the impact of various factors on implicit Process Reward Model (PRM) performance. It explores whether incorporating additional data (instructions from different sources, removal of duplicate responses, or replacement with diverse responses) or incorporating step-level labels from a Math-Shepherd model improves the performance of the implicit PRM. The results show that none of these factors consistently enhance the implicit PRM’s performance. This suggests that the implicit PRM is surprisingly robust and data efficient, achieving good results even without these extra factors.

read the caption

Table 2: Factors that may affect PRM performance. To our surprise, none of them consistently improve our implicit PRM.

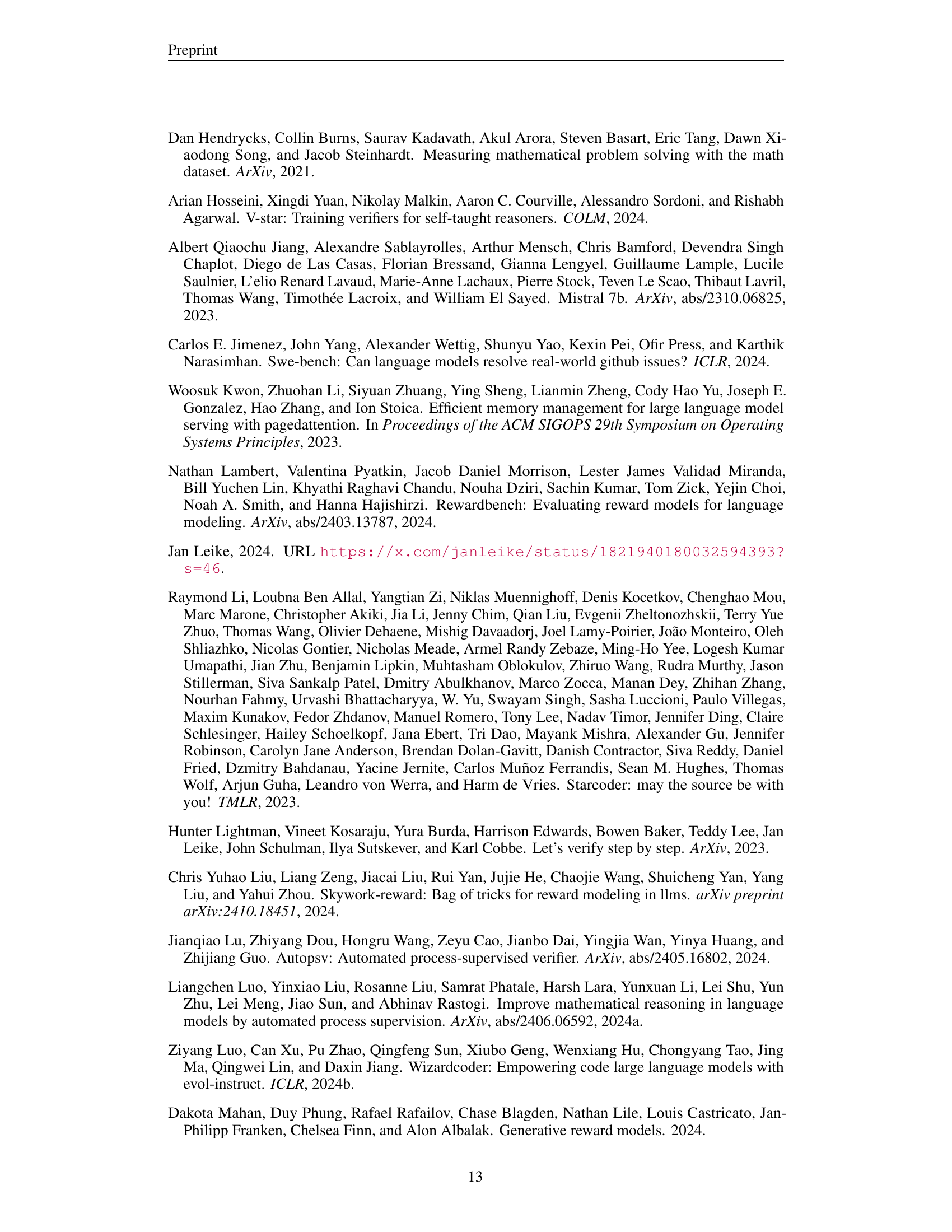

| Model | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Llama-3.1-8B-Inst | 45.2 |

| + DPO | 25.8 |

| + KTO | 46.6 |

| + NCA | 35.6 |

| + CE | 28.6 |

🔼 This table presents the results of using implicit PRMs (trained using different reward modeling objectives) as policy models to directly solve problems from the MATH500 dataset. It contrasts the performance of the implicit PRMs, each instantiated with a different objective (DPO, KTO, NCA, and CE), against the baseline performance of Llama-3.1-8B-Inst to assess whether the ability of a model to function as an effective process reward model correlates with its ability to perform well as a policy model on the same tasks.

read the caption

Table 3: Implicit PRMs’ performance on MATH500 when used to solve the problems directly.

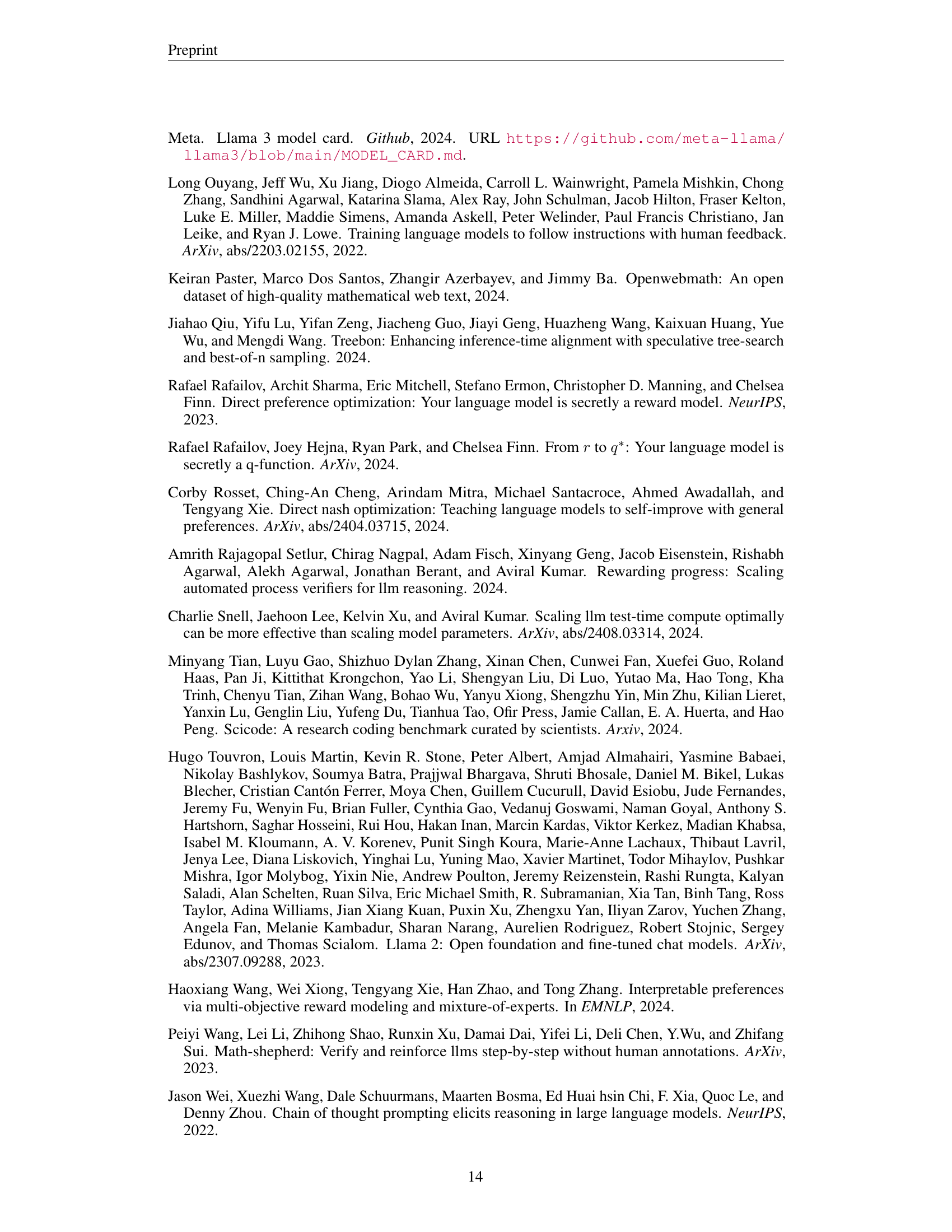

| Source of Cost | Method | Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2 | Llama-3.1-8B-Inst | Llama-3.1-70B-Inst |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation Model | - | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Reward Model | Baselines | 33.5 | 29.4 | 9.1 |

| Implicit PRM | 201.6 | 141.7 | 22.2 | |

| Total | Baselines | 200.9 | 171.1 | 111.1 |

| Implicit PRM | 301.6 | 241.7 | 122.2 |

🔼 This table compares the GPU time costs for best-of-N sampling using different reward models, relative to the time cost of the generation model. It shows the breakdown of time spent on generation versus reward model calculation for several baseline methods and the proposed implicit PRM. The key finding is that the additional cost of the reference model in the implicit PRM does not significantly increase the overall inference time, especially when the generation model is substantially larger than the reward model. The percentages provided illustrate that the baselines have considerably higher overall inference overheads than the implicit PRM.

read the caption

Table 4: GPU time costs during best-of-N sampling relative to the cost of generation model (%). The overall inference overhead of baselines on three test sets are 66.6%, 70.8%, and 90.9% of that of our implicit PRM, respectively. Namely, the reference model does not double the inference cost in practice, and the extra inference overhead becomes more marginal as the generation model gets larger.

| Setup | Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2 | Llama-3.1-8B-Inst | Llama-3.1-70B-Inst | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Inference | @4 | @16 | @64 |

| Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct w/o Ref | 14.8 | 16.2 | 18.4 | 49.0 |

| + DPO w/ Ref w/ Ref | 18.6 | 24.4 | 28.8 | 54.0 |

| + DPO w/ Ref w/o Ref | 17.8 | 23.4 | 27.8 | 54.2 |

| + DPO w/o Ref w/ Ref | 17.8 | 23.4 | 28.4 | 54.0 |

| + DPO w/o Ref w/o Ref | 17.4 | 22.6 | 25.6 | 54.8 |

🔼 This table investigates the impact of removing the reference model from both the training and inference phases of the implicit PRM. The results show that removing the reference model does not consistently harm the performance of the implicit PRM. Surprisingly, the reference model (Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct) itself performs well in best-of-N sampling, suggesting that a strong pre-trained model might obviate the need for the extra reference model in certain situations. The table compares the best-of-N sampling performance on three different generation models (Mistral-7B-Inst-v0.2, Llama-3.1-8B-Inst, Llama-3.1-70B-Inst) under different setups: with and without the reference model during training and inference, along with the performance of the reference model used as a standalone reward model.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablating reference model in both training and inference. Neither consistently hurts our implicit PRM. More surprisingly, the reference model, Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct, already perfroms well on Best-of-N sampling.

Full paper#