↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are becoming increasingly powerful, but understanding their internal workings remains a challenge. A major obstacle is ‘polysemanticity,’ where individual neurons respond to multiple, unrelated concepts. Existing methods like Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) have limitations, including post-hoc training that negatively impacts performance and limited scalability. This paper tackles this problem.

The researchers introduce MONET, a new LLM architecture that directly integrates sparse dictionary learning into Mixture-of-Experts training. This allows for a significant increase in the number of experts while maintaining parameter efficiency. Experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of MONET in improving interpretability, enabling knowledge manipulation over various domains and languages. The results suggest that scaling the number of experts significantly contributes to creating more transparent and controllable LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to improving the interpretability of large language models (LLMs). MONET offers a solution to the challenge of polysemanticity in LLMs, a significant hurdle in understanding how these models work. By enhancing interpretability, this research opens doors for better alignment of LLMs with human values, improved control over model behavior, and the prevention of undesirable outputs like toxic content generation. This work is highly relevant to the current trends in mechanistic interpretability and AI safety, and the findings have the potential to shape future research in this rapidly developing field.

Visual Insights#

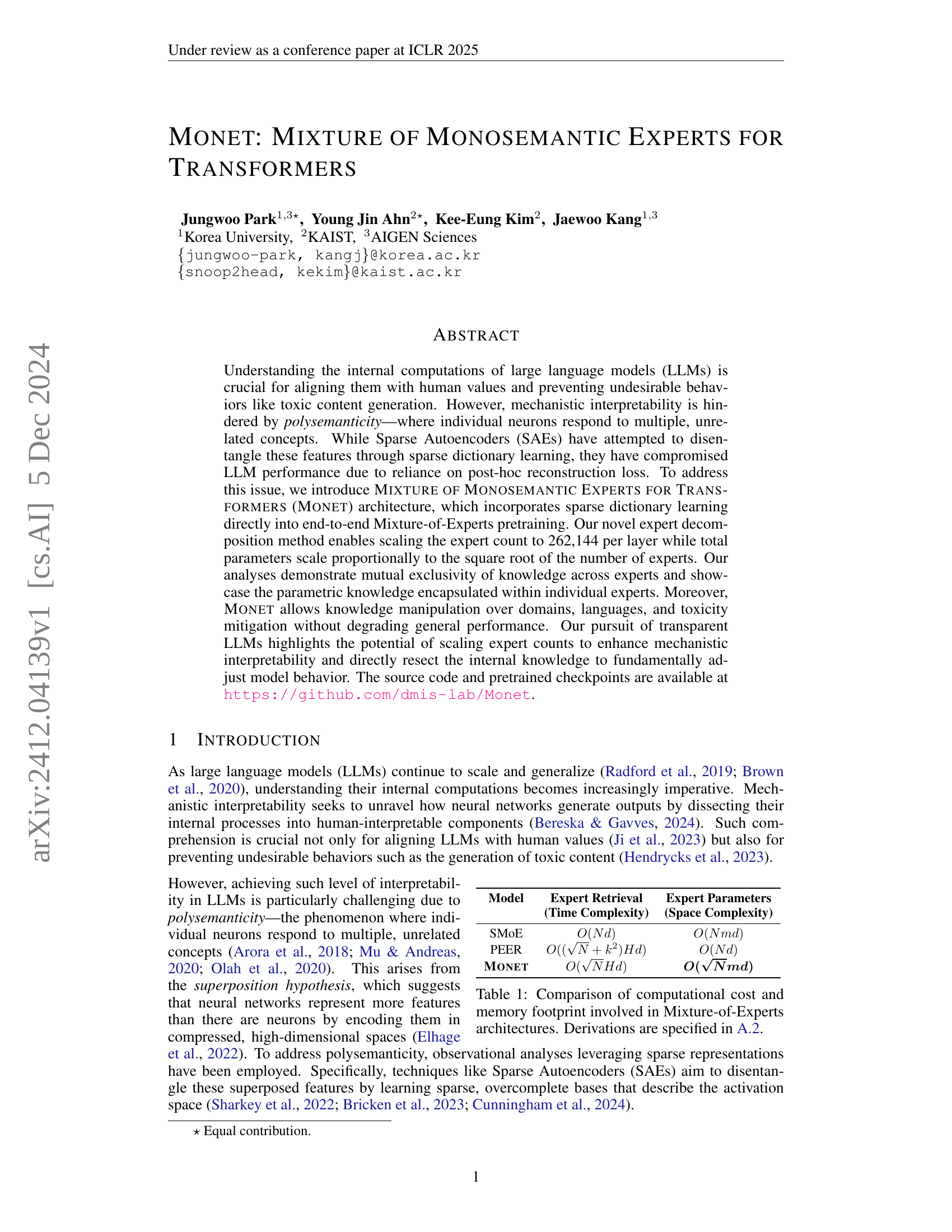

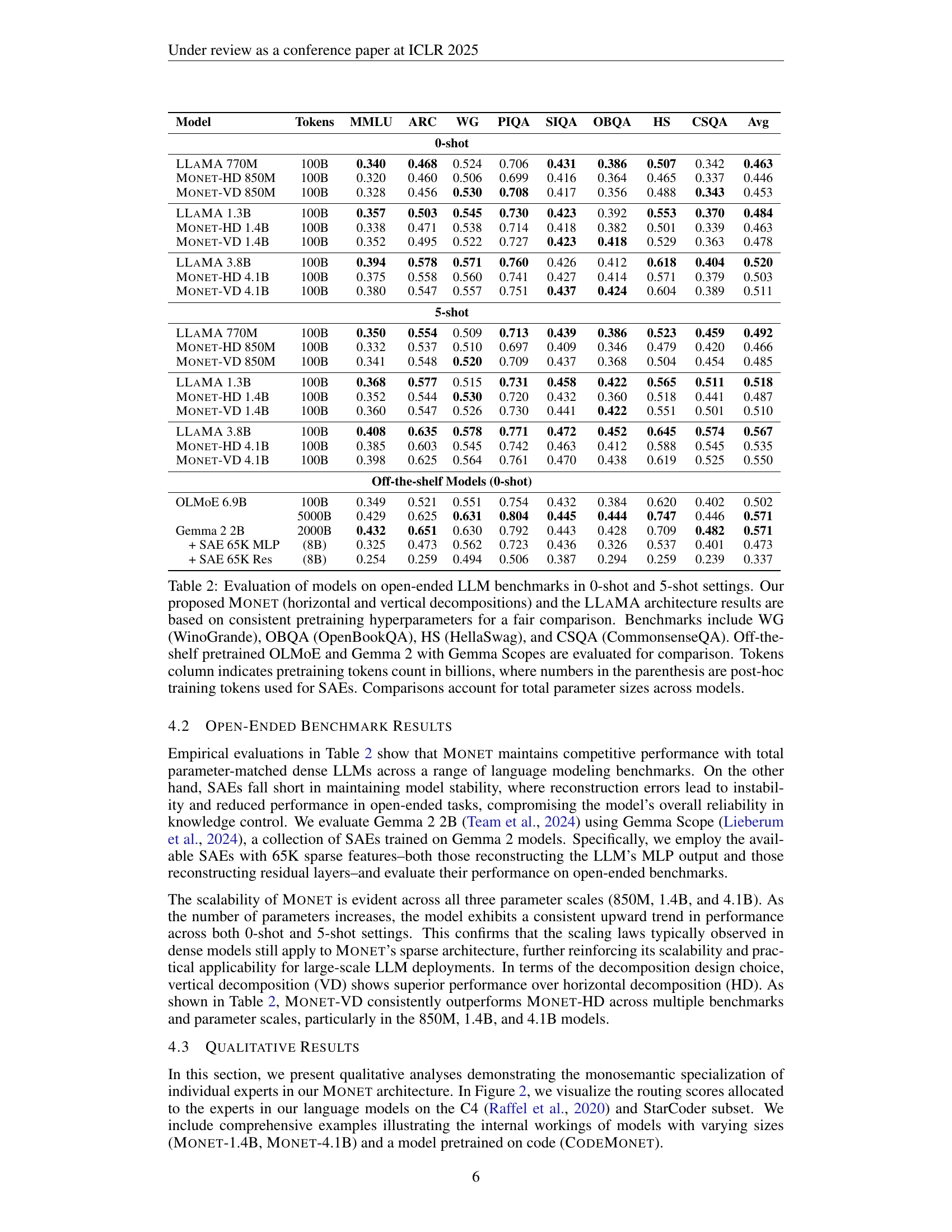

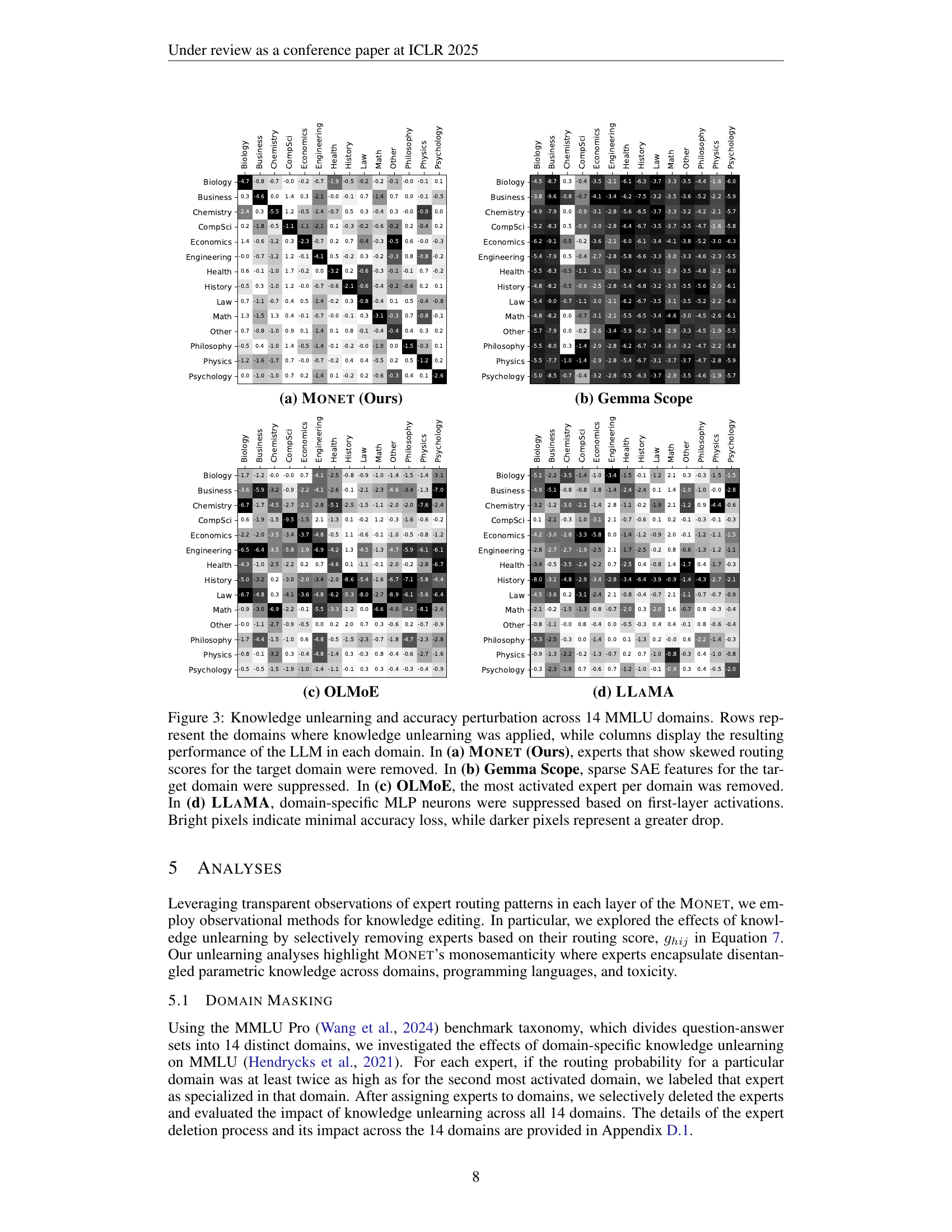

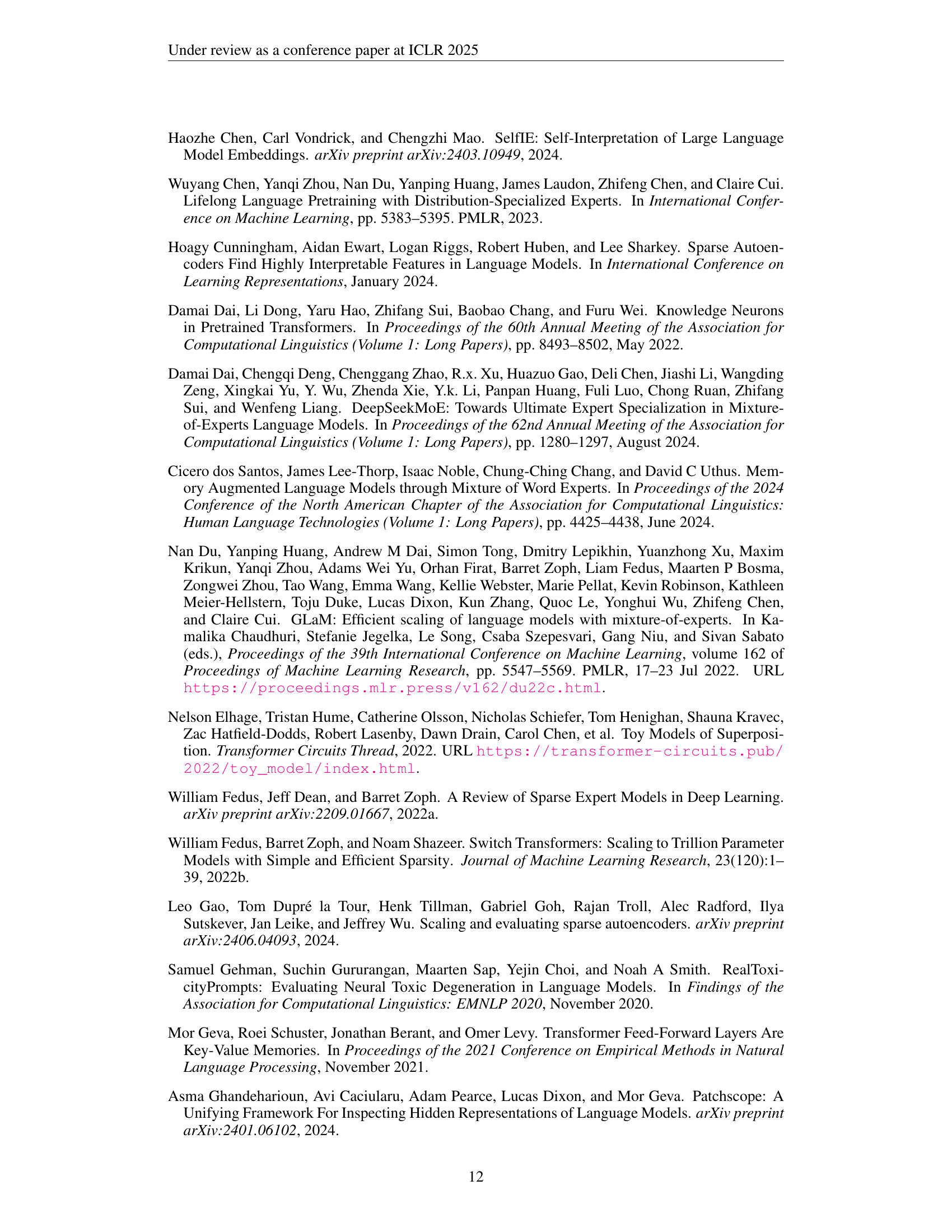

🔼 Figure 1 compares three different approaches for scaling the number of experts in large language models. The first, PEER, uses a straightforward method where each of N experts is stored separately and retrieved using product keys. This leads to memory usage that increases linearly with N (O(N)). The second approach, Monet-HD (Horizontal Decomposition), improves efficiency by splitting each expert into a ‘bottom’ and ’top’ layer. During inference, these components are combined dynamically, reducing the memory requirement to the square root of N (O(√N)). The third approach, Monet-VD (Vertical Decomposition), employs a similar strategy but divides the layers into left and right segments, maintaining the same memory efficiency as Monet-HD (O(√N)).

read the caption

Figure 1: Architectural comparison of expert scaling approaches in large language models. (1) PEER stores N𝑁Nitalic_N standalone experts accessed via product key retrieval, resulting in memory usage that grows linearly with the number of experts, O(N)𝑂𝑁O(N)italic_O ( italic_N ). (2) Our proposed Monet-HD (Horizontal Decomposition) partitions experts into bottom and top layers, dynamically composing experts. This reduces space complexity to O(N)𝑂𝑁O(\sqrt{N})italic_O ( square-root start_ARG italic_N end_ARG ). (3) Monet-VD (Vertical Decomposition) orthogonally partitions layers with left and right segments, while maintaining the same space complexity.

| Model | Expert Retrieval (Time Complexity) | Expert Parameters (Space Complexity) |

|---|---|---|

| SMoE | O(Nd) | O(Nmd) |

| PEER | O(( | |

| √N+k2)Hd) | O(Nd) | |

| Monet | O( | |

| √NHd) | O( | |

| √Nmd) |

🔼 This table compares the computational cost (time complexity) and memory usage (space complexity) of three different Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures: SMOE, PEER, and MONET. It shows how these costs scale with the number of experts (N) and other parameters (d, k, H, m). The time complexity refers to the time taken for expert retrieval, while space complexity indicates the memory required for storing expert parameters. Detailed derivations of these complexities are provided in section A.2 of the paper.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of computational cost and memory footprint involved in Mixture-of-Experts architectures. Derivations are specified in A.2.

In-depth insights#

Monosemantic Experts#

The concept of “Monosemantic Experts” in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on creating specialized neural network components that respond to a single, well-defined concept or semantic meaning. This is a significant departure from the traditional polysemantic nature of LLMs where individual neurons often exhibit diverse and overlapping activations. The core benefit of monosemantic experts is improved interpretability. By isolating concepts into dedicated experts, we can better understand the LLM’s internal reasoning processes. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing challenges such as polysemy and disentangling overlapping features, leading to more transparent and controllable models. The practical implications include enhanced alignment with human values, facilitating easier detection and mitigation of undesirable behaviors like toxicity, and improving the robustness of LLM outputs. Although the creation and management of a vast number of monosemantic experts pose significant computational challenges, the potential rewards in terms of improved model understanding and control make this a promising avenue for future LLM research.

MoE Architecture#

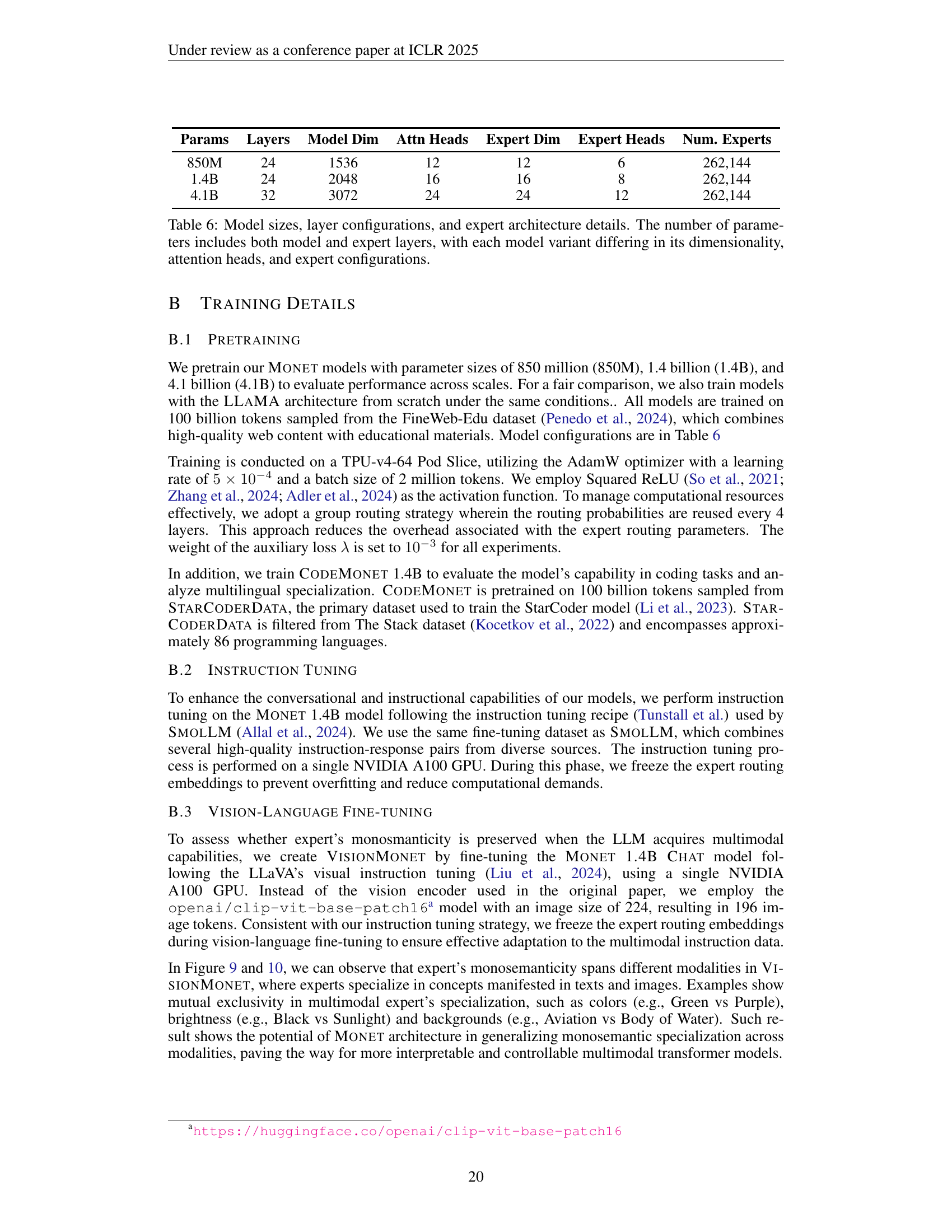

The research paper explores Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures as a mechanism to enhance the interpretability and performance of large language models (LLMs). A core challenge addressed is the polysemanticity of neurons in LLMs, where single neurons respond to multiple, unrelated concepts. Traditional MoE approaches, however, often suffer from limitations such as a limited number of experts, leading to knowledge hybridity, and inefficient parameter scaling. The proposed MONET architecture directly addresses these issues by incorporating sparse dictionary learning directly into MoE pretraining. This allows for a significant increase in the number of experts (up to 262,144 per layer) while maintaining parameter efficiency through novel decomposition methods. This scaling of experts is crucial for achieving monosemanticity, where individual experts encapsulate distinct, interpretable knowledge. The architecture also incorporates techniques such as parameter-efficient expert retrieval and load balancing loss to improve computational efficiency and ensure uniform expert usage. MONET’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments showcasing knowledge manipulation over domains and languages without performance degradation, highlighting its potential for transparent and controllable LLMs.

Knowledge Editing#

The concept of ‘Knowledge Editing’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) is a significant advancement in the field of mechanistic interpretability. It proposes methods to directly manipulate an LLM’s internal knowledge representations, allowing for targeted adjustments of model behavior without extensive retraining. This capability is particularly valuable in addressing issues like bias mitigation and toxicity reduction. The approach likely involves identifying specific neurons or groups of neurons (experts) responsible for certain knowledge domains and then selectively modifying their activation patterns. This can be achieved through various techniques, such as modifying connection weights, adjusting neuron thresholds, or even removing specific components entirely. Success hinges on disentangling polysemantic features of LLMs, where individual neurons respond to multiple, unrelated concepts, as well as ensuring that these edits do not introduce adverse effects in other parts of the model. The effectiveness of knowledge editing will depend on the granularity of the knowledge representation within the model and the precision of the methods used. Ethical considerations around knowledge editing are paramount, requiring careful consideration of the potential implications of such powerful technology and the development of appropriate safeguards.

Parameter Efficiency#

Parameter efficiency is a crucial aspect of large language models (LLMs), especially as they grow increasingly massive. The paper explores this by introducing a novel expert decomposition method within their Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture. This approach enables scaling the number of experts significantly, impacting model capacity and potentially improving mechanistic interpretability. The key innovation is that the total number of parameters scales proportionally to the square root of the number of experts, rather than linearly. This is achieved through techniques like horizontal and vertical decomposition of expert networks, thus reducing memory requirements. The paper highlights that the parameter-efficient design allows for a much larger number of experts (262,144 per layer) compared to previous MoE approaches, leading to more specialized and disentangled knowledge representation within each expert. This is a significant advancement addressing limitations of previous methods that sacrificed performance for sparsity or struggled to effectively scale expert counts. The effectiveness of this parameter-efficient architecture is demonstrated through experiments and benchmarks, showing competitive performance with much larger dense LLMs while maintaining efficient resource utilization. This parameter efficiency is directly linked to improved interpretability and the ability for robust knowledge manipulation without impacting overall model performance.

Future of LLMs#

The future of LLMs hinges on addressing current limitations and exploring new avenues. Improving interpretability is crucial, moving beyond black-box models to understand their decision-making processes. This involves developing techniques to visualize and analyze internal representations, potentially using methods like those explored in the paper to disentangle polysemantic neurons. Enhanced efficiency is another key area; current models are computationally expensive, demanding significant resources for training and inference. Future development will likely focus on creating more efficient architectures and training paradigms. Further advancements will also likely involve combining LLMs with other modalities, such as vision and robotics, to create more versatile and powerful AI systems. Finally, ethical considerations will play a pivotal role, focusing on mitigating bias, ensuring fairness, and addressing potential misuse. Robust safety mechanisms are crucial to manage risks associated with increasingly powerful LLMs, guiding development toward beneficial and responsible applications.

More visual insights#

More on tables

| Model | Tokens | MMLU | ARC | WG | PIQA | SIQA | OBQA | HS | CSQA | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-shot | ||||||||||

| LLaMA 770M | 100B | 0.340 | 0.468 | 0.524 | 0.706 | 0.431 | 0.386 | 0.507 | 0.342 | 0.463 |

| Monet-HD 850M | 100B | 0.320 | 0.460 | 0.506 | 0.699 | 0.416 | 0.364 | 0.465 | 0.337 | 0.446 |

| Monet-VD 850M | 100B | 0.328 | 0.456 | 0.530 | 0.708 | 0.417 | 0.356 | 0.488 | 0.343 | 0.453 |

| LLaMA 1.3B | 100B | 0.357 | 0.503 | 0.545 | 0.730 | 0.423 | 0.392 | 0.553 | 0.370 | 0.484 |

| Monet-HD 1.4B | 100B | 0.338 | 0.471 | 0.538 | 0.714 | 0.418 | 0.382 | 0.501 | 0.339 | 0.463 |

| Monet-VD 1.4B | 100B | 0.352 | 0.495 | 0.522 | 0.727 | 0.423 | 0.418 | 0.529 | 0.363 | 0.478 |

| LLaMA 3.8B | 100B | 0.394 | 0.578 | 0.571 | 0.760 | 0.426 | 0.412 | 0.618 | 0.404 | 0.520 |

| Monet-HD 4.1B | 100B | 0.375 | 0.558 | 0.560 | 0.741 | 0.427 | 0.414 | 0.571 | 0.379 | 0.503 |

| Monet-VD 4.1B | 100B | 0.380 | 0.547 | 0.557 | 0.751 | 0.437 | 0.424 | 0.604 | 0.389 | 0.511 |

| 5-shot | ||||||||||

| LLaMA 770M | 100B | 0.350 | 0.554 | 0.509 | 0.713 | 0.439 | 0.386 | 0.523 | 0.459 | 0.492 |

| Monet-HD 850M | 100B | 0.332 | 0.537 | 0.510 | 0.697 | 0.409 | 0.346 | 0.479 | 0.420 | 0.466 |

| Monet-VD 850M | 100B | 0.341 | 0.548 | 0.520 | 0.709 | 0.437 | 0.368 | 0.504 | 0.454 | 0.485 |

| LLaMA 1.3B | 100B | 0.368 | 0.577 | 0.515 | 0.731 | 0.458 | 0.422 | 0.565 | 0.511 | 0.518 |

| Monet-HD 1.4B | 100B | 0.352 | 0.544 | 0.530 | 0.720 | 0.432 | 0.360 | 0.518 | 0.441 | 0.487 |

| Monet-VD 1.4B | 100B | 0.360 | 0.547 | 0.526 | 0.730 | 0.441 | 0.422 | 0.551 | 0.501 | 0.510 |

| LLaMA 3.8B | 100B | 0.408 | 0.635 | 0.578 | 0.771 | 0.472 | 0.452 | 0.645 | 0.574 | 0.567 |

| Monet-HD 4.1B | 100B | 0.385 | 0.603 | 0.545 | 0.742 | 0.463 | 0.412 | 0.588 | 0.545 | 0.535 |

| Monet-VD 4.1B | 100B | 0.398 | 0.625 | 0.564 | 0.761 | 0.470 | 0.438 | 0.619 | 0.525 | 0.550 |

| Off-the-shelf Models (0-shot) | ||||||||||

| OLMoE 6.9B | 100B | 0.349 | 0.521 | 0.551 | 0.754 | 0.432 | 0.384 | 0.620 | 0.402 | 0.502 |

| 5000B | 0.429 | 0.625 | 0.631 | 0.804 | 0.445 | 0.444 | 0.747 | 0.446 | 0.571 | |

| Gemma 2 2B | 2000B | 0.432 | 0.651 | 0.630 | 0.792 | 0.443 | 0.428 | 0.709 | 0.482 | 0.571 |

| + SAE 65K MLP (8B) | 0.325 | 0.473 | 0.562 | 0.723 | 0.436 | 0.326 | 0.537 | 0.401 | 0.473 | |

| + SAE 65K Res (8B) | 0.254 | 0.259 | 0.494 | 0.506 | 0.387 | 0.294 | 0.259 | 0.239 | 0.337 |

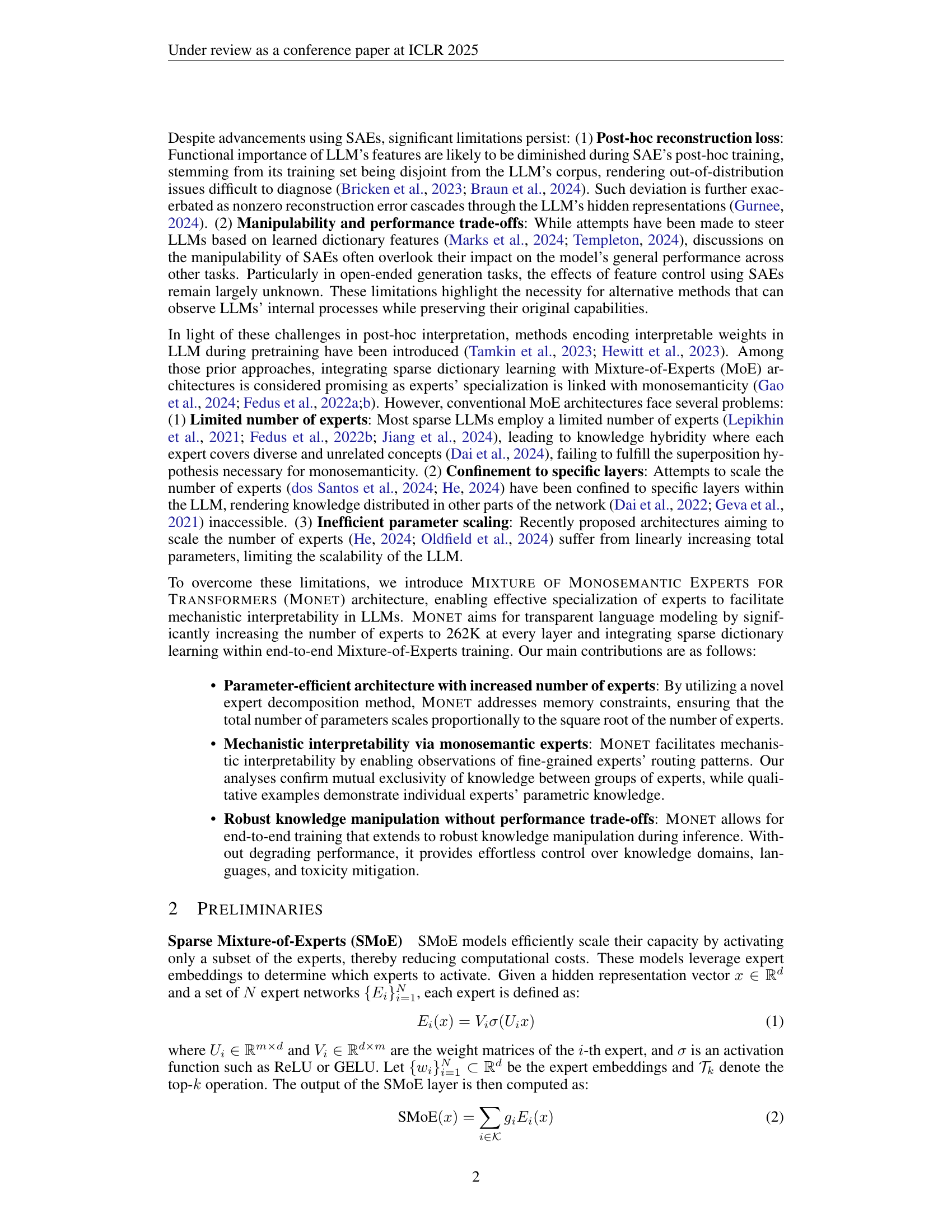

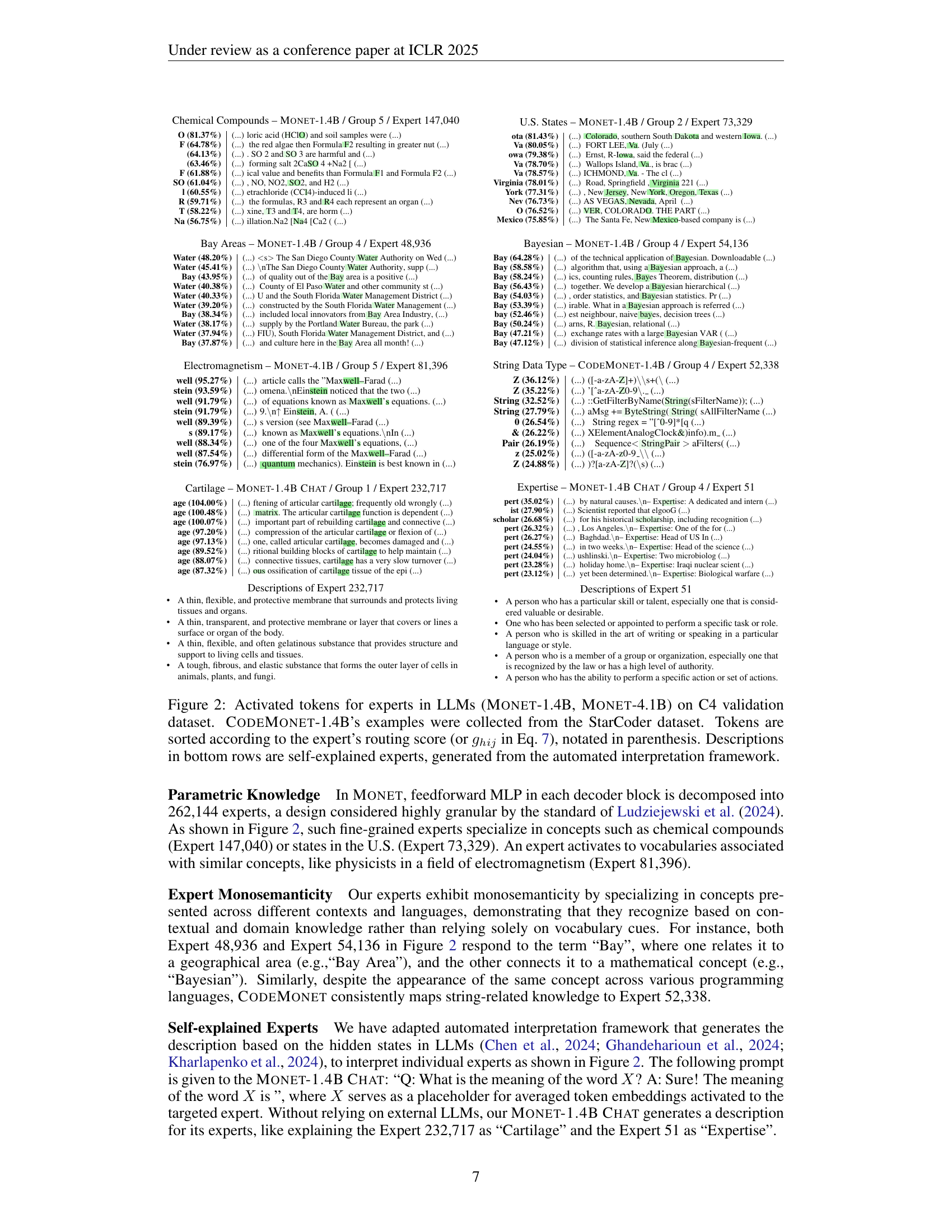

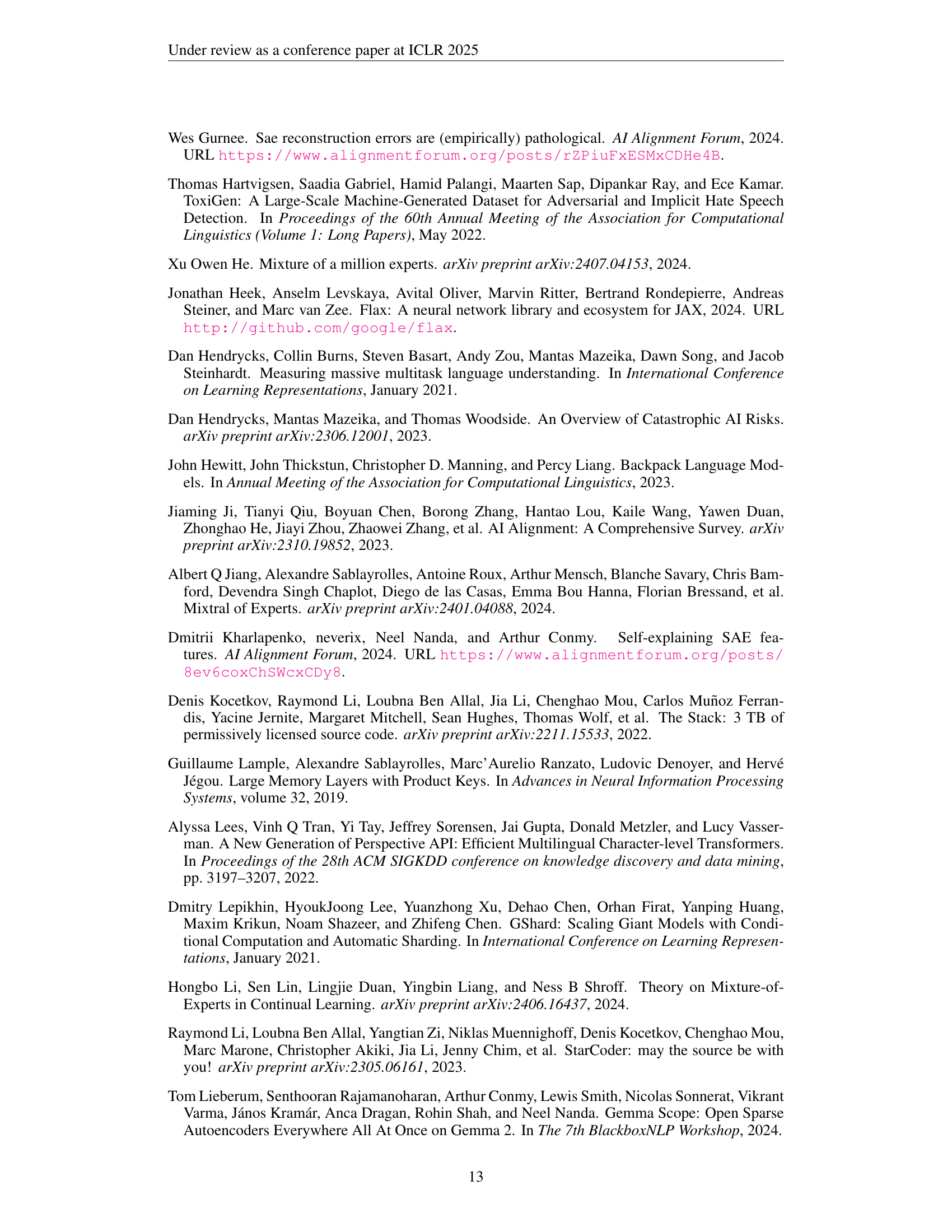

🔼 This table presents the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on several open-ended question answering benchmarks. The models are evaluated under both zero-shot (0-shot) and five-shot (5-shot) settings. Zero-shot means the model is given the question without any context examples, while five-shot means the model receives five context examples before being asked the question. The models compared include the authors’ proposed MONET architecture (with both horizontal and vertical decompositions), the LLaMA architecture, and existing models like OLMoE and Gemma 2 (using Gemma Scopes). For fair comparison, all MONET and LLaMA models were trained using consistent pre-training hyperparameters. The table shows the performance scores for each model on several benchmarks, namely WinoGrande (WG), OpenBookQA (OBQA), HellaSwag (HS), and CommonsenseQA (CSQA). The ‘Tokens’ column indicates the number of tokens used in the pre-training phase (in billions); numbers in parentheses denote the number of tokens used for post-hoc training of Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs), where applicable. The comparison of models takes into account their total parameter size for a fair evaluation.

read the caption

Table 2: Evaluation of models on open-ended LLM benchmarks in 0-shot and 5-shot settings. Our proposed Monet (horizontal and vertical decompositions) and the LLaMA architecture results are based on consistent pretraining hyperparameters for a fair comparison. Benchmarks include WG (WinoGrande), OBQA (OpenBookQA), HS (HellaSwag), and CSQA (CommonsenseQA). Off-the-shelf pretrained OLMoE and Gemma 2 with Gemma Scopes are evaluated for comparison. Tokens column indicates pretraining tokens count in billions, where numbers in the parenthesis are post-hoc training tokens used for SAEs. Comparisons account for total parameter sizes across models.

| Formula | Description |

|---|---|

| O (81.37%) | (…)loric acid (HClO) and soil samples were (…) |

| F (64.78%) | (…) the red algae then Formula F2 resulting in greater nut (…) |

| (64.13%) | (…) . SO 2 and SO 3 are harmful and (…) |

| (63.46%) | (…) forming salt 2CaSO 4 +Na 2 [ (…) |

| F (61.88%) | (…) ical value and benefits than Formula F1 and Formula F2 (…) |

| SO (61.04%) | (…) , NO, NO 2 , SO 2 , and H 2 (…) |

| l (60.55%) | (…) etrachloride (CCl 4 )-induced li (…) |

| R (59.71%) | (…) the formulas, R3 and R4 each represent an organ (…) |

| T (58.22%) | (…) xine, T3 and T4, are h (…) |

| Na (56.75%) | (…) illation.Na 2 [Na 4 [Ca 2 ( (…) |

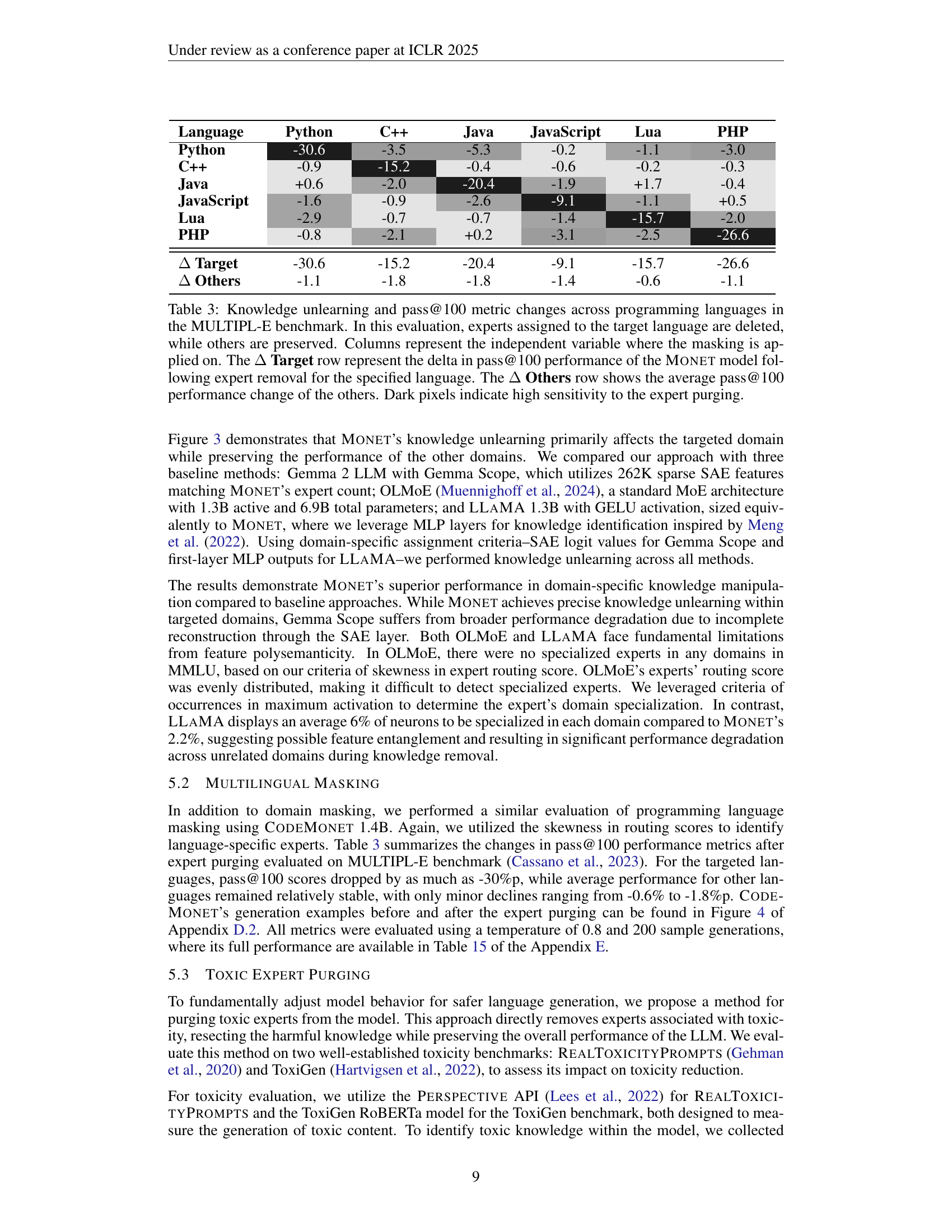

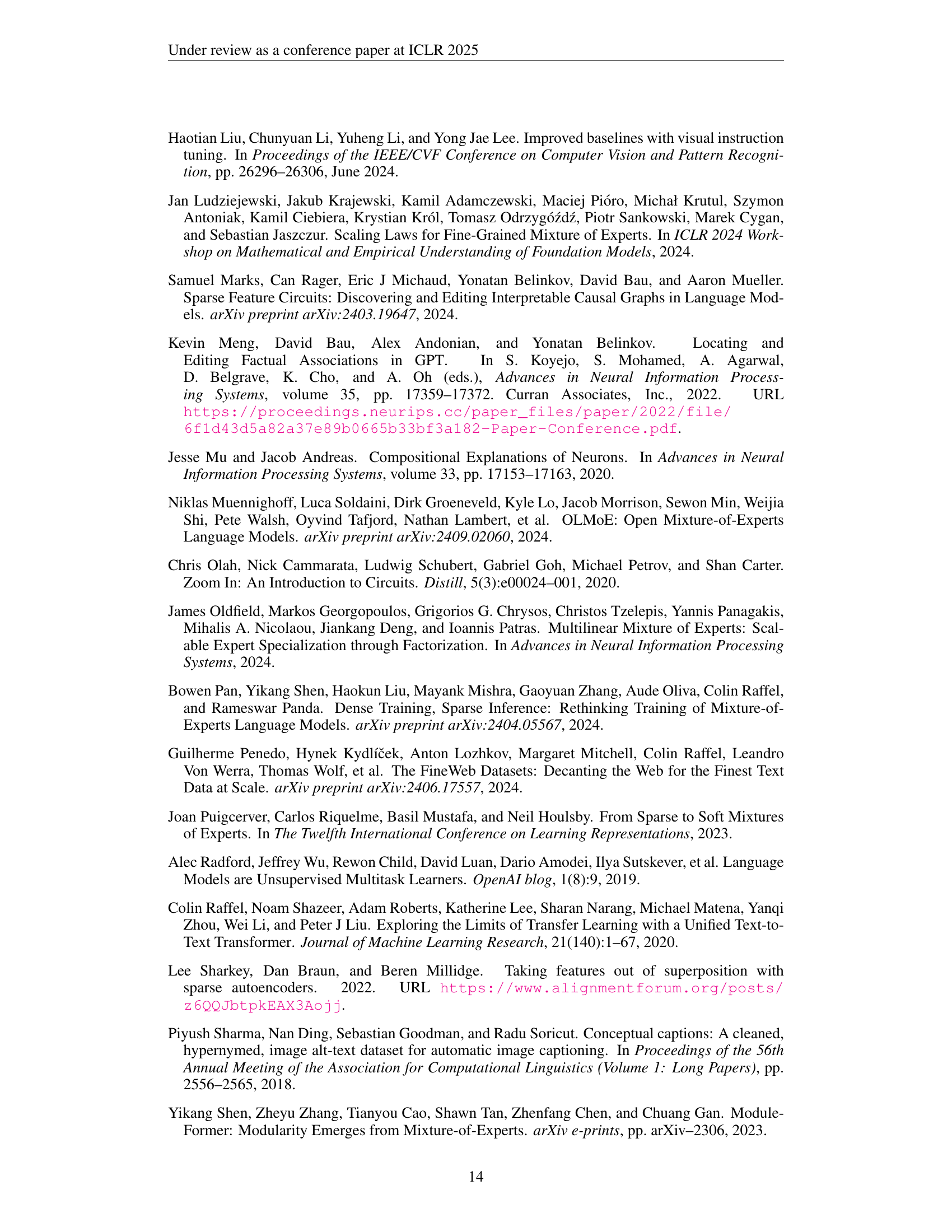

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of removing experts associated with specific programming languages on the performance of the Monet model. The Monet model is a large language model designed for code generation. The MULTIPL-E benchmark was used to assess the model’s performance after removing the experts. The table shows the change in pass@100 (the percentage of test cases where the model correctly generated code) for each programming language (both the target language where experts were removed and other languages). The ‘Δ Target’ row indicates the performance drop for the specific language whose experts were removed. The ‘Δ Others’ row shows the average performance change in other languages. Darker shading indicates a more substantial drop in performance, signifying higher sensitivity to the removal of experts in that particular language.

read the caption

Table 3: Knowledge unlearning and pass@100 metric changes across programming languages in the MULTIPL-E benchmark. In this evaluation, experts assigned to the target language are deleted, while others are preserved. Columns represent the independent variable where the masking is applied on. The ΔΔ\Deltaroman_Δ Target row represent the delta in pass@100 performance of the Monet model following expert removal for the specified language. The ΔΔ\Deltaroman_Δ Others row shows the average pass@100 performance change of the others. Dark pixels indicate high sensitivity to the expert purging.

| Location | Percentage |

|---|---|

| ota (81.43%) | (…) Colorado, southern South Dakota and western Iowa. (…) |

| Va (80.05%) | (…) FORT LEE, Va. (July (…) |

| owa (79.38%) | (…) Ernst, R-Iowa, said the federal (…) |

| Va (78.70%) | (…) Walops Island, Va., is brac (…) |

| Va (78.57%) | (…) RICHMOND, Va. - The cl (…) |

| Virginia (78.01%) | (…) Road, Springfield , Virginia 221 (…) |

| York (77.31%) | (…) , New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas (…) |

| Nev (76.73%) | (…) AS VEGAS, Nev.ada, April (…) |

| O (76.52%) | (…) VER, COLORADO. THE PART (…) |

| Mexico (75.85%) | (…) The Santa Fe, New Mexico-based company is (…) |

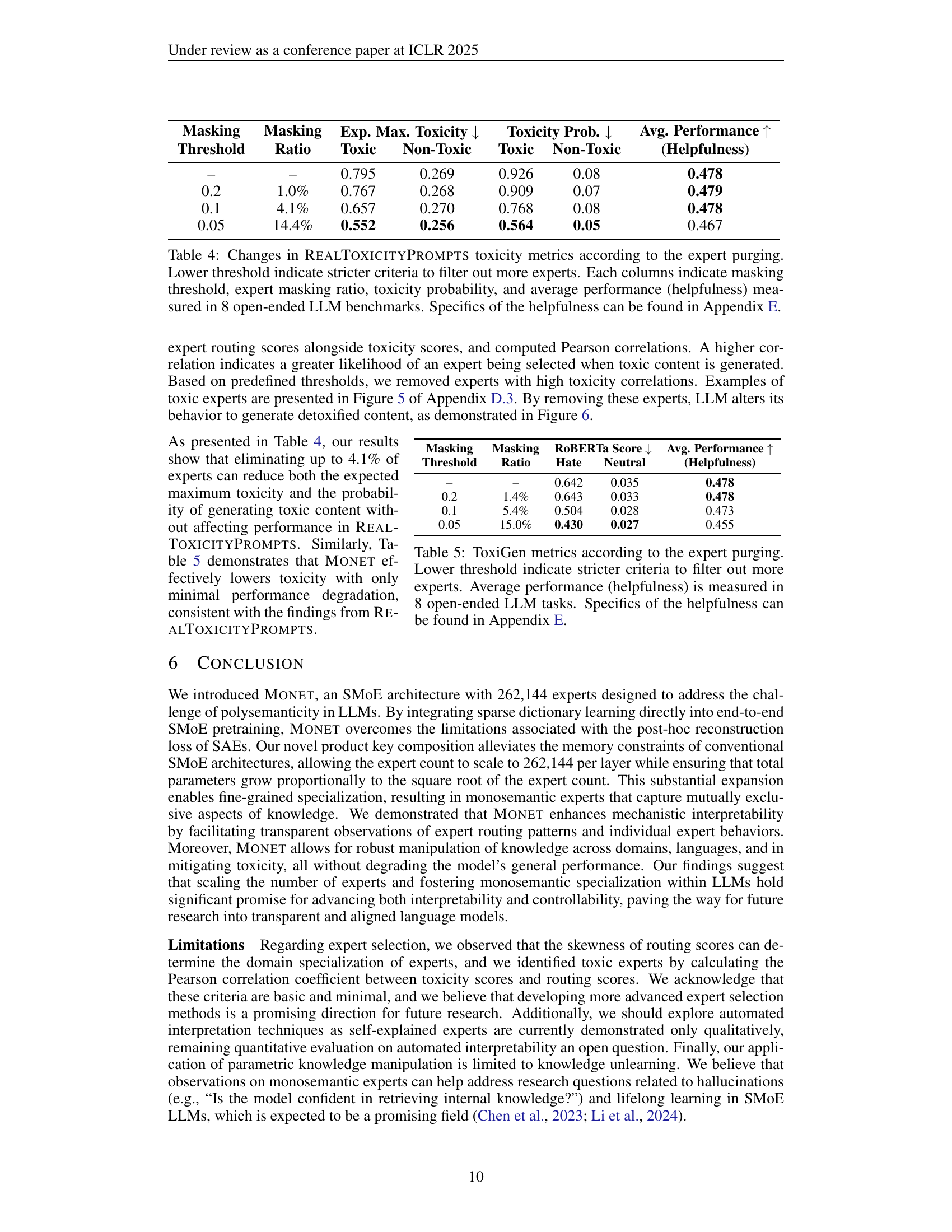

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of removing toxic experts from a large language model (LLM) on its toxicity and overall performance. The experiment used different thresholds to determine how many experts to remove, resulting in varying levels of expert removal (masking ratio). The table shows the effect on the maximum toxicity score (the highest toxicity score observed across all generated responses), the probability of a toxic response (the proportion of responses exceeding a toxicity threshold of 0.5), and the average performance across eight open-ended LLM benchmarks (helpfulness). A lower threshold for expert removal leads to a stricter filtering process, resulting in fewer experts and a lower toxicity probability, but also potentially impacting helpfulness. Appendix E contains more details about how the helpfulness scores were calculated across the benchmark tasks.

read the caption

Table 4: Changes in RealToxicityPrompts toxicity metrics according to the expert purging. Lower threshold indicate stricter criteria to filter out more experts. Each columns indicate masking threshold, expert masking ratio, toxicity probability, and average performance (helpfulness) measured in 8 open-ended LLM benchmarks. Specifics of the helpfulness can be found in Appendix E.

| Water (%) | Description |

|---|---|

| Water (48.20%) | (…) The San Diego County Water Authority on Wed (…) |

| Water (45.41%) | (…) The San Diego County Water Authority, supp (…) |

| Bay (43.95%) | (…) of quality out of the Bay area is a positive (…) |

| Water (40.38%) | (…) County of El Paso Water and other community st (…) |

| Water (40.33%) | (…) U and the South Florida Water Management District (…) |

| Water (39.20%) | (…) constructed by the South Florida Water Management (…) |

| Bay (38.34%) | (…) included local innovators from Bay Area Indust (…) |

| Water (38.17%) | (…) supply by the Portland Water Bureau, the park (…) |

| Water (37.94%) | (…) FIU), South Florida Water Management District, and (…) |

| Bay (37.87%) | (…) and culture here in the Bay Area all month! (…) |

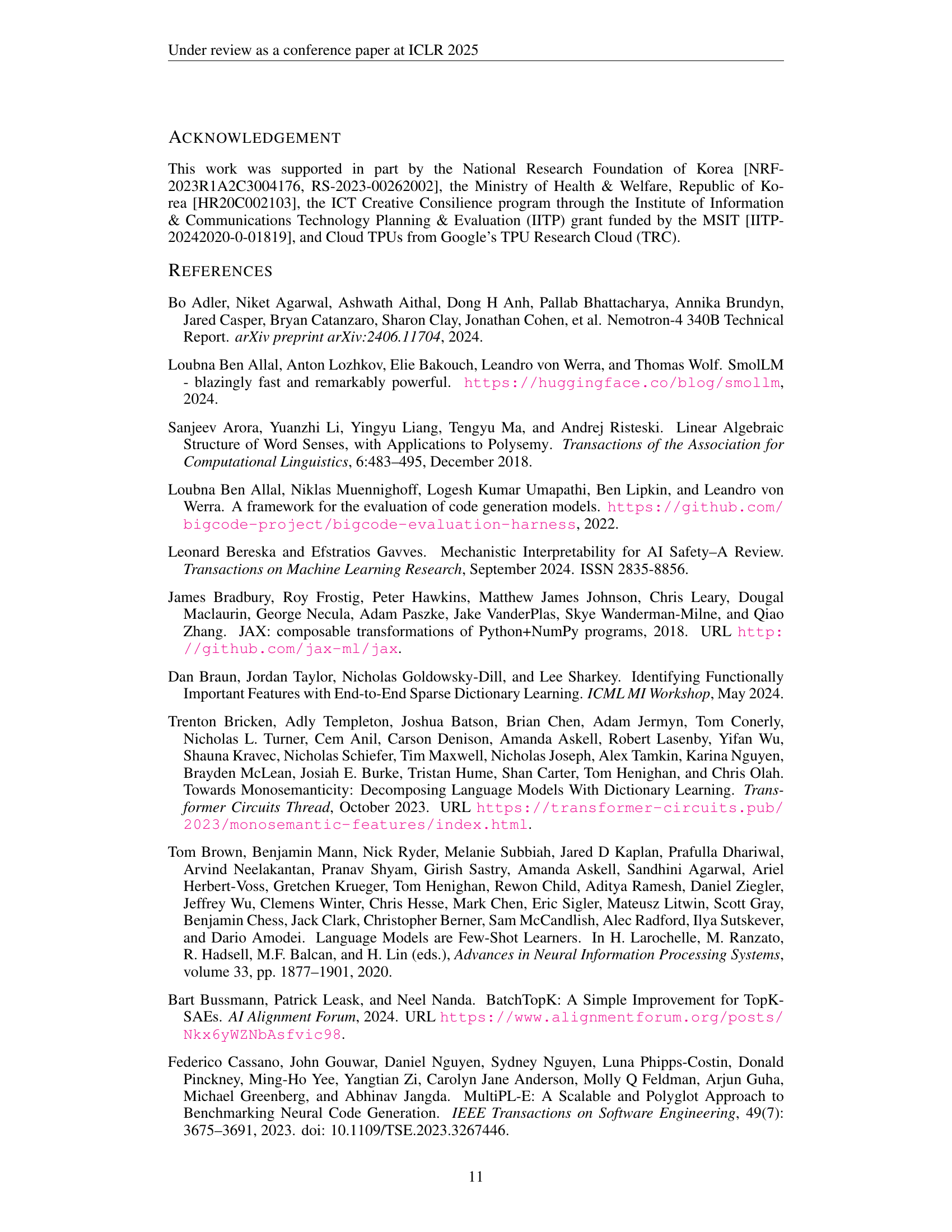

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the impact of removing toxic experts from a large language model (LLM) using the ToxiGen dataset. The experiments varied a threshold for identifying and removing these experts; a lower threshold leads to more experts being removed, resulting in a stricter filtering process. The table shows the ratio of experts removed, the resulting maximum toxicity scores (measured by the ToXiGen RoBERTa model) and the probability of generating toxic responses. Finally, the table also reports the average performance (helpfulness) of the LLM across eight open-ended benchmark tasks after applying each level of expert purging. A more detailed breakdown of these helpfulness metrics can be found in Appendix E.

read the caption

Table 5: ToxiGen metrics according to the expert purging. Lower threshold indicate stricter criteria to filter out more experts. Average performance (helpfulness) is measured in 8 open-ended LLM tasks. Specifics of the helpfulness can be found in Appendix E.

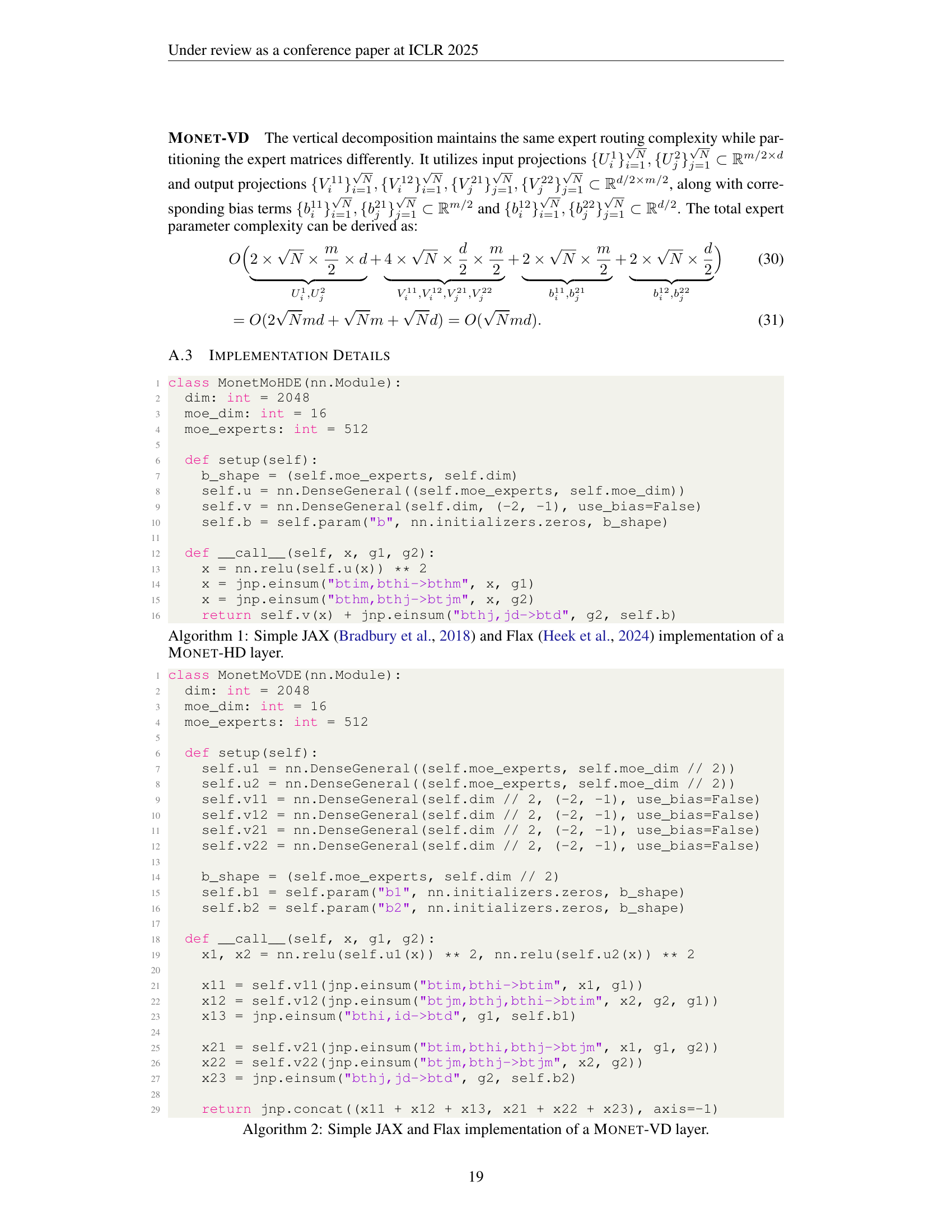

🔼 This table details the architecture of three different MONET models (850M, 1.4B, and 4.1B parameters), comparing their size, depth, width, attention heads, expert dimensions, expert heads, and total number of experts. It highlights how these architectural choices impact the overall parameter count and illustrate variations in model configurations across different scales.

read the caption

Table 6: Model sizes, layer configurations, and expert architecture details. The number of parameters includes both model and expert layers, with each model variant differing in its dimensionality, attention heads, and expert configurations.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| well (95.27%) | (…) article calls the ”Maxwell–Farad (…) |

| stein (93.59%) | (…) omena. stein noticed that the two (…) |

| well (91.79%) | (…) of equations known as Maxwell’s equations. (…) |

| stein (91.79%) | (…) 9. ↑ stein, A. (…) |

| well (89.39%) | (…) s version (see well–Farad (…) |

| s (89.17%) | (…) known as Maxwell’s equations. |

| In (…) | |

| well (88.34%) | (…) one of the four Maxwell’s equations, (…) |

| well (87.54%) | (…) differential form of the well–Farad (…) |

| stein (76.97%) | (…) quantum mechanics). stein is best known in (…) |

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of varying auxiliary loss weights on the model’s performance. Auxiliary losses, specifically uniformity and ambiguity, were used to encourage balanced expert usage and distinct expert specialization, respectively. The table shows the 5-shot average performance across various benchmarks for different values of the auxiliary loss weights (lambda), illustrating how changes to these weights affect the model’s ability to balance expert usage and maintain distinct expert roles.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation results showing the impact of varying auxiliary loss weights.

| Token | Percentage | Snippet |

|---|---|---|

| Z (36.12%) | (…) [-a-zA-Z]+\s+((…) | |

| Z (35.22%) | (…) ’[^a-zA-Z0-9._] (…) | |

| String (32.52%) | (…) ::GetFilterByName(String(sFilterName)); (…) | |

| String (27.79%) | (…) aMsg += ByteString( String(sAllFilterName (…) | |

| 0 (26.54%) | (…) String regex = ”[^0-9]*[q (…) | |

| & (26.22%) | (…) XElementAnalogClock&)info).m_ (…) | |

| Pair (26.19%) | (…) Sequence< StringPair > aFilters(…) | |

| z (25.02%) | (…) [-a-zA-Z0-9_\ (…) | |

| Z (24.88%) | (…) )?[a-zA-Z]?( | |

| (…) |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effect of varying the number of expert routing groups in the MONET architecture. It shows how different group sizes impact the model’s performance (measured by average 5-shot accuracy across various benchmarks), the total number of parameters, and the floating point operations (FLOPs) required for forward computation. The purpose is to evaluate the trade-off between computational efficiency and model performance when adjusting the granularity of expert routing.

read the caption

Table 8: Impact of different routing group sizes.

| age (%) | Description |

|---|---|

| age (104.00%) | (…) fttening of articular cartilage; frequently old wrongly (…) |

| age (100.48%) | (…) matrix. The articular cartilage function is dependent (…) |

| age (100.07%) | (…) important part of rebuilding cartilage and connective (…) |

| age (97.20%) | (…) compression of the articular cartilage or flexion of (…) |

| age (97.13%) | (…) one, called articular cartilage, becomes damaged and (…) |

| age (89.52%) | (…) ritional building blocks of cartilage to help maintain (…) |

| age (88.07%) | (…) connective tissues, cartilage has a very slow turnover (…) |

| age (87.32%) | (…) ous ossification of cartilage tissue of the epi (…) |

🔼 This table shows the number of experts in the MONET-1.4B model that are specialized in each of 14 different domains within the MMLU benchmark. The model’s architecture uses multiple routing groups to distribute processing across experts. This table breaks down the expert counts for each domain across each of the 6 routing groups, and then shows the total number of experts assigned to each domain across all groups. This provides insight into how the model’s knowledge is distributed and specialized within its expert network.

read the caption

Table 9: Number of experts masked as domain-specialized experts in Monet-1.4B. The table reports the number of experts assigned to each domain across all routing groups. Each group corresponds to one of the 6 routing groups, and the total number of experts per domain is provided.

🔼 This table shows the number of experts in the CodeMonet-1.4B model that are specialized in each of six programming languages. The model uses a Mixture of Experts (MoE) architecture, meaning it has many different expert networks, each specializing in a different area. This table breaks down how many experts are dedicated to each programming language, across all the different ‘routing groups’ (the mechanism that decides which experts are used for each task). A higher number indicates a greater specialization of experts in that particular language within the CodeMonet-1.4B model.

read the caption

Table 10: Number of experts masked as language-specialized experts in CodeMonet-1.4B. The table reports the number of experts assigned to each programming language across all routing groups.

| Language | Python | C++ | Java | JavaScript | Lua | PHP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Python | -30.6 | -3.5 | -5.3 | -0.2 | -1.1 | -3.0 |

| C++ | -0.9 | -15.2 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.2 | -0.3 |

| Java | +0.6 | -2.0 | -20.4 | -1.9 | +1.7 | -0.4 |

| JavaScript | -1.6 | -0.9 | -2.6 | -9.1 | -1.1 | +0.5 |

| Lua | -2.9 | -0.7 | -0.7 | -1.4 | -15.7 | -2.0 |

| PHP | -0.8 | -2.1 | +0.2 | -3.1 | -2.5 | -26.6 |

| Δ Target | -30.6 | -15.2 | -20.4 | -9.1 | -15.7 | -26.6 |

| Δ Others | -1.1 | -1.8 | -1.8 | -1.4 | -0.6 | -1.1 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the impact of removing specific groups of experts from the MONET model on its performance across various domains of the MMLU benchmark. Each row represents a domain in the MMLU benchmark (e.g., Biology, Business, Chemistry, etc.). Each column represents a category of experts that have been removed from the model (e.g., experts specializing in Biology, Business, etc.), with a final column displaying the original model performance with no experts removed. The values within the table show the performance (accuracy) of the MONET model on the given MMLU domain after removing the specified experts. The ‘ΔΔ Target’ row shows the change in accuracy for the target domain (the domain listed in the row) due to expert removal. The ‘ΔΔ Others’ row shows the average change in accuracy across all other domains not listed in the row. This allows for an assessment of how removing a specific type of expert affects performance on a particular domain, as well as its impact on overall performance.

read the caption

Table 11: General performance of Monet on MMLU domains after masking specialized experts. Columns represent the categories of masked experts, while rows display the MMLU performance for each domain following the removal the corresponding experts. The column “None” contains the original performance of the Monet without any experts removed. The row labeled “ΔΔ\Deltaroman_Δ Target” indicates the accuracy change in the target domain due to unlearning, while the row labeled “ΔΔ\Deltaroman_Δ Others” reflects the average performance change across all other domains.

| Masking Threshold | Masking Ratio | Exp. Max. Toxicity ↓ | Toxicity Prob. ↓ | Avg. Performance ↑ (Helpfulness) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | – | 0.795 | 0.269 | 0.926 | 0.08 | 0.478 |

| 0.2 | 1.0% | 0.767 | 0.268 | 0.909 | 0.07 | 0.479 |

| 0.1 | 4.1% | 0.657 | 0.270 | 0.768 | 0.08 | 0.478 |

| 0.05 | 14.4% | 0.552 | 0.256 | 0.564 | 0.05 | 0.467 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of the pretrained Gemma 2 language model on the MMLU benchmark after selectively removing features learned by Gemma Scope Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs). Each column represents a category of SAE features that were suppressed before the evaluation, and each row displays the resulting performance on a specific domain within the MMLU benchmark. Due to the high granularity of the data, zooming in on the table is necessary for full comprehension of the results. The table shows the impact of removing specific knowledge from different domains on the model’s overall performance across various domains.

read the caption

Table 12: General performance of pretrained Gemma 2 on MMLU domains after suppressing features of Gemma Scope SAE. Columns indicate categories of the suppressed features, and rows display domain-specific MMLU performance. Please zoom in for detailed results.

| Masking | Masking | RoBERTa Score ↓ | Avg. Performance ↑ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | Ratio | Hate | Neutral | (Helpfulness) |

| – | – | 0.642 | 0.035 | 0.478 |

| 0.2 | 1.4% | 0.643 | 0.033 | 0.478 |

| 0.1 | 5.4% | 0.504 | 0.028 | 0.473 |

| 0.05 | 15.0% | 0.430 | 0.027 | 0.455 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of removing specific knowledge from the OLMoE language model. Each column represents a domain or category of knowledge that was selectively removed (masked) from the model. Each row represents a specific domain within the MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) benchmark. The table shows the model’s performance on each MMLU domain after the specified category of knowledge was removed. The ‘None’ column shows the baseline performance before any knowledge was removed. The ‘Target’ row shows the change in performance for the specific domain that had its knowledge removed, while the ‘Others’ row shows the average performance change across all other domains. The numbers in the table represent the performance scores, enabling a comparison of model performance before and after selective knowledge removal.

read the caption

Table 13: General performance of OLMoE after masking specialized experts. Columns represent the categories of masked experts, while rows display the MMLU performance for each domain following the removal the corresponding experts. Please zoom in for detailed results.

| Params | Layers | Model Dim | Attn Heads | Expert Dim | Expert Heads | Num. Experts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 850M | 24 | 1536 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 262,144 |

| 1.4B | 24 | 2048 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 262,144 |

| 4.1B | 32 | 3072 | 24 | 24 | 12 | 262,144 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of a Large Language Model (LLM) called LLaMA after selectively removing information from its internal processing layers, specifically focusing on Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs). The table is organized with rows representing different domains of knowledge (as measured by the MMLU benchmark) and columns showing the impact of suppressing information from particular categories of MLPs. Each cell in the table shows the LLM’s performance on a specific domain after removing information from a category of MLPs. This allows for analysis of how the LLM’s knowledge is affected by the removal of various feature types. Due to the complexity of the data, zooming in is recommended for a better understanding of the detailed results.

read the caption

Table 14: General performance of LLaMA after suppressing logits in MLPs. Columns indicate categories of the suppressed features, and rows display domain-specific MMLU performance. Please zoom in for detailed results.

| λ | Uniformity ↓ | Ambiguity ↓ | Avg. (5-shot) |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | 6.433 | 0.611 | 0.505 |

| 2 × 10⁻⁴ | 6.347 | 0.584 | 0.505 |

| 1 × 10⁻³ | 6.280 | 0.497 | 0.510 |

| 5 × 10⁻³ | 6.262 | 0.260 | 0.502 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of the CodeMonet model on the MULTIPL-E benchmark, a coding task evaluation dataset, across six different programming languages. The ‘pass@100’ metric indicates the percentage of test cases successfully solved by the model. The experiment involved selectively removing (‘purging’) experts in the model that specialized in each programming language. The purpose was to assess the impact of this selective removal of knowledge (unlearning) on the model’s performance. The ‘None’ column shows CodeMonet’s original performance on the benchmark without any expert removal.

read the caption

Table 15: CodeMonet’s pass@100 performance on MULTIPL-E benchmark across programming languages after purging experts specialized in each language. The column “None” stands for the original performance of CodeMonet according to each language.

| Group Size | Params | FLOPs | Avg. (5-shot) |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | 1.345B | 6225.52T | 0.518 |

| 4 | 1.465B | 6745.30T | 0.510 |

| 1 | 1.767B | 8017.81T | 0.511 |

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the MONET model’s performance on two benchmark datasets for toxicity detection: RealToxicityPrompts and ToxiGen. The evaluation is performed under zero-shot conditions, meaning the model receives no prior training on these specific datasets. The table shows how the model’s performance (measured across several metrics like MMLU, ARC, WG, PIQA, SIQA, OBQA, HS, and CSQA) varies depending on different thresholds for identifying and removing toxic experts. The thresholds are determined by calculating Pearson correlations between expert activation patterns and toxicity scores. Lower thresholds indicate a stricter criterion for removing experts, resulting in a potentially more safe but less performant model.

read the caption

Table 16: Model performance on RealToxicityPrompts and ToxiGen with varying correlation thresholds, evaluated under zero-shot settings.

Full paper#