↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Instruction-guided image editing has seen significant progress, but existing datasets often lack the quality and diversity needed for reliable model evaluation. Many existing datasets rely on limited human feedback or are generated using models, potentially misaligning them with actual human preferences. This limits the ability to effectively evaluate and improve the performance of image editing models.

HumanEdit addresses these limitations by providing a high-quality human-rewarded dataset. It features 5,751 high-resolution images with diverse editing instructions, meticulously curated through a four-stage annotation pipeline. This rigorous process ensured accuracy and reliability, enabling more robust model evaluations. HumanEdit also includes masks for all images and supports mask-free editing for a subset of the data, promoting diverse and realistic editing scenarios. The dataset’s comprehensive nature sets a new benchmark for future research and model development in instruction-guided image editing.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in image editing and computer vision because it introduces a high-quality, human-annotated dataset, HumanEdit, addressing limitations in existing datasets. HumanEdit enables more accurate and reliable evaluation of image editing models, facilitating advancements in instruction-guided image editing. Its comprehensive nature, including diverse editing tasks and high-resolution images, sets a new benchmark for future research and opens avenues for exploring advanced editing techniques.

Visual Insights#

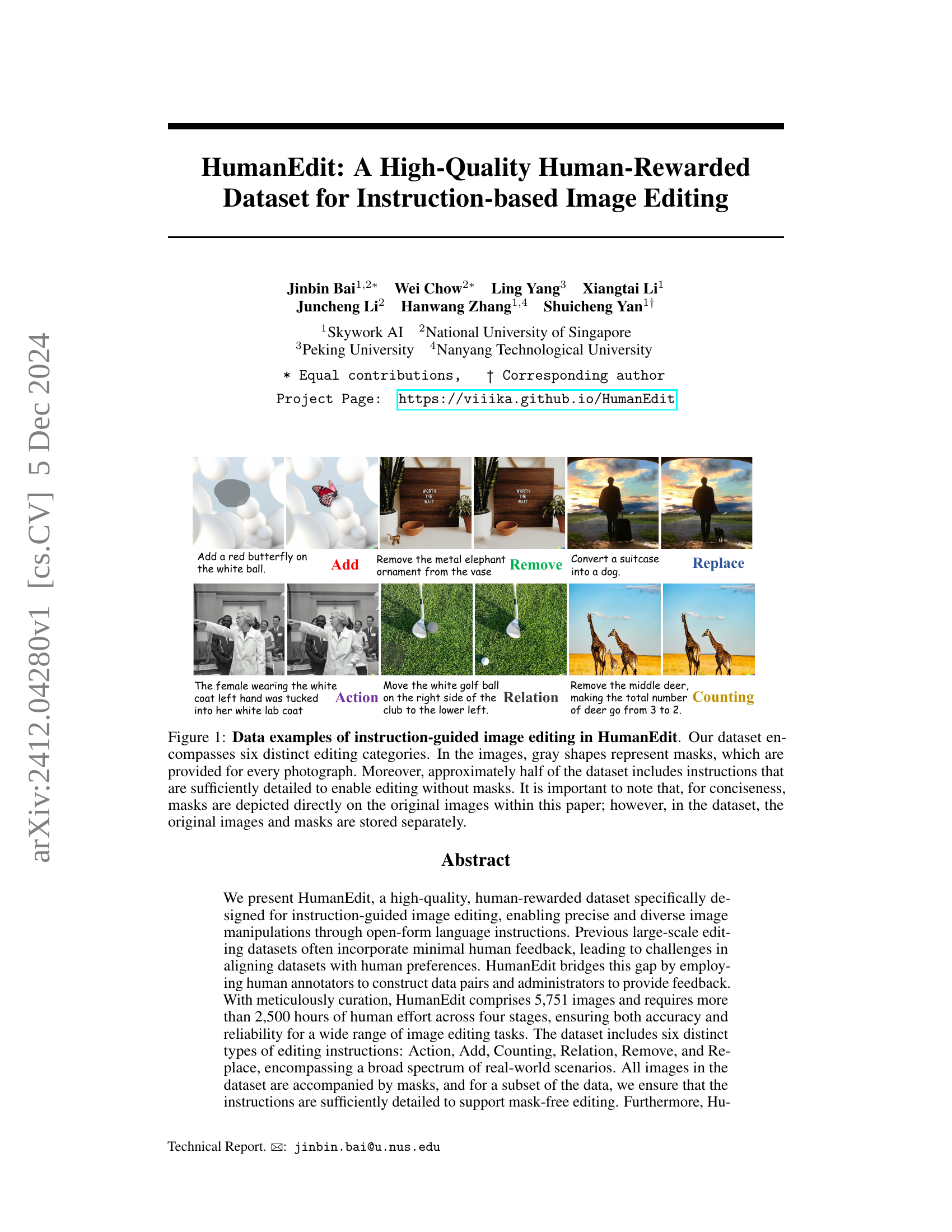

🔼 This figure showcases examples from the HumanEdit dataset, illustrating the six different image editing categories it covers: Action, Add, Counting, Relation, Remove, and Replace. Each example shows an original image with an overlaid gray mask indicating the area to be modified. The corresponding instruction specifies the desired edit. Importantly, the caption highlights that while masks are shown here for clarity, approximately half of the dataset’s instructions are detailed enough for editing without explicit masks. In the dataset itself, images and their respective masks are stored as separate files.

read the caption

Figure 1: Data examples of instruction-guided image editing in HumanEdit. Our dataset encompasses six distinct editing categories. In the images, gray shapes represent masks, which are provided for every photograph. Moreover, approximately half of the dataset includes instructions that are sufficiently detailed to enable editing without masks. It is important to note that, for conciseness, masks are depicted directly on the original images within this paper; however, in the dataset, the original images and masks are stored separately.

| Add | Rmove | Replace | Action | Counting | Relation | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HumanEdit-full | 801 | 1,813 | 1,370 | 659 | 698 | 410 |

| HumanEdit-core | 30 | 188 | 97 | 37 | 20 | 28 |

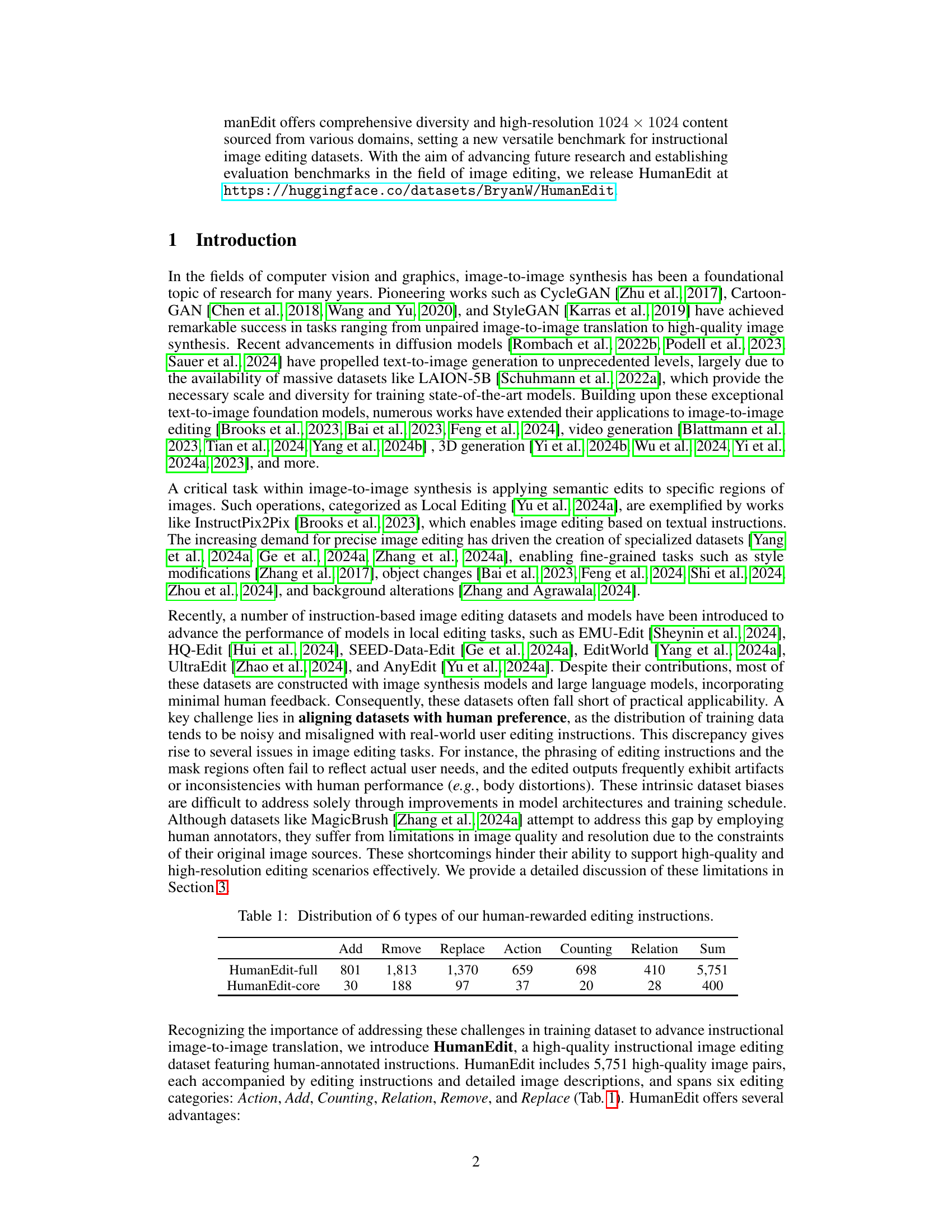

🔼 This table shows the distribution of the six different types of image editing instructions used in the HumanEdit dataset. The dataset was created using human annotators and administrators to ensure quality and alignment with human preferences. Each row represents a category of editing instructions, and the numbers indicate how many images in the dataset belong to each category. These numbers sum up to the total number of images in the HumanEdit dataset (5,751). The categories are Action, Add, Counting, Relation, Remove, and Replace. This breakdown illustrates the diversity of editing tasks encompassed within the dataset, highlighting the dataset’s scope and versatility.

read the caption

Table 1: Distribution of 6 types of our human-rewarded editing instructions.

In-depth insights#

HumanEdit Dataset#

The HumanEdit dataset represents a significant contribution to the field of instruction-based image editing. Its high-quality, human-annotated images and diverse editing instructions address the limitations of previous datasets that often relied on minimal human feedback. The meticulous curation process, involving multiple rounds of validation and quality control, ensures high data accuracy and consistency. HumanEdit’s mask differentiation capability supports both mask-free and mask-provided editing scenarios, enhancing its versatility. The dataset’s broad range of editing tasks, encompassing six distinct categories, along with its high-resolution images and diverse sources, establishes it as a robust benchmark for evaluating and developing future image editing models. The inclusion of a detailed guidance book further facilitates research and ensures reproducibility. Overall, HumanEdit’s comprehensive nature, combined with its focus on human preferences, positions it as a valuable tool for advancing research in instruction-based image editing.

Annotation Pipeline#

The effectiveness of any image editing dataset hinges on the quality of its annotations. A robust annotation pipeline is crucial, and this paper’s approach is noteworthy. It employs a four-stage process. First, rigorous annotator training and selection ensures consistency in annotation style. Second, careful image curation focuses on high-resolution, high-quality imagery, sourced from Unsplash, avoiding the limitations of smaller, model-generated datasets. The third stage involves creating diverse and detailed editing instructions, along with masks where needed, leveraging DALL-E 2. Finally, a multi-level quality control process is implemented, involving both automated checks and human review. This thorough approach is key in bridging the gap between model-generated datasets and the human preference for high-quality, diverse, and nuanced image editing instructions. The multi-stage review process, involving internal platform workers and administrators significantly reduces errors and ensures high-quality data suitable for rigorous benchmarks and model training.

Benchmark Results#

A thorough analysis of benchmark results in a research paper requires a multifaceted approach. It’s crucial to understand the metrics used (e.g., L1, L2, CLIP, DINO), as different metrics emphasize various aspects of image quality. Direct comparison across different methods necessitates careful consideration of factors like model architecture, training data, and hyperparameter choices. The dataset’s characteristics (image resolution, diversity, and the inclusion of mask-free editing) significantly influence benchmark performance, and understanding the dataset’s limitations is essential for interpreting results. Analyzing results across various editing categories (add, remove, replace, etc.) helps uncover the strengths and weaknesses of different methods for specific tasks. A robust analysis should also include a qualitative assessment of the generated images, comparing visual quality and fidelity to the reference images. Finally, a discussion of potential biases and limitations inherent in the benchmark process and the dataset itself is critical for drawing balanced and meaningful conclusions.

DALL-E2’s Limits#

DALL-E 2, while a powerful image generation model, reveals limitations when tasked with complex image editing. Inherent inconsistencies in generating edits, especially those involving subtle changes or precise counts, show the challenges in achieving pixel-perfect results based solely on textual instructions. Furthermore, the model’s tendency toward oversimplification is apparent in the failure to properly execute more complex edits involving object relations or actions, instead often resulting in unintended changes or loss of detail. These issues, alongside limitations in understanding nuanced instructions, highlight the need for more sophisticated approaches for instruction-based image editing. Addressing these issues will likely require combining DALL-E 2 with more robust methods such as incorporating detailed masking, improving instruction parsing, and better handling of contextual relationships within images. The observed discrepancies underscore the importance of human oversight and iterative refinement in the image editing process to ensure alignment between desired outcomes and actual generated results.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for instruction-based image editing should prioritize improving the robustness and generalization capabilities of current models. This includes addressing limitations in handling complex instructions, particularly those involving nuanced relationships or actions. Addressing inherent biases and inconsistencies in existing datasets is crucial, requiring more sophisticated annotation methods and potentially, the use of alternative data generation techniques beyond existing LLMs and diffusion models. Furthermore, research should focus on developing more efficient and scalable models that can process high-resolution images quickly and require minimal computational resources. Finally, exploring novel evaluation metrics beyond pixel-level comparisons is essential to better assess the quality and alignment of edits with user intent, and to ensure that models meet real-world user needs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

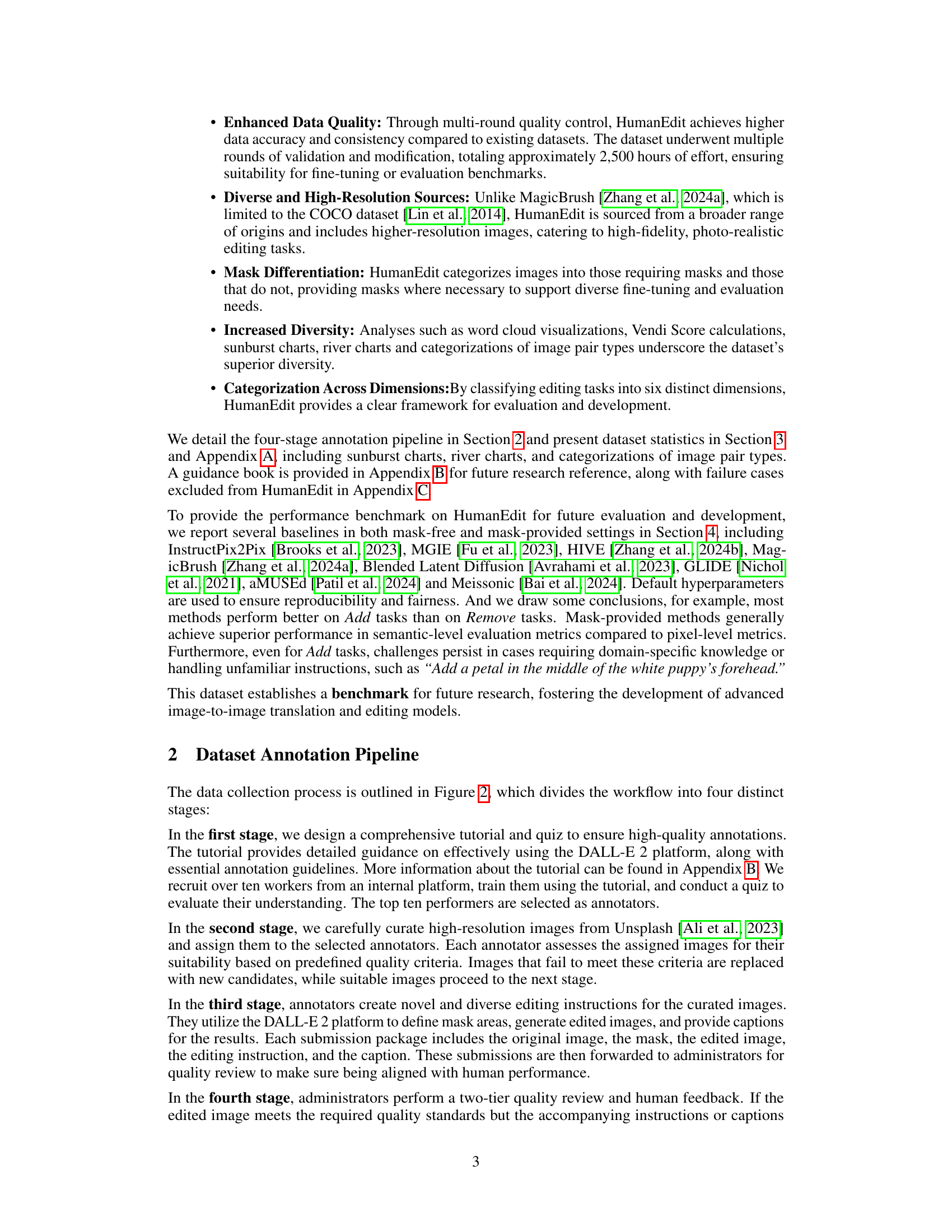

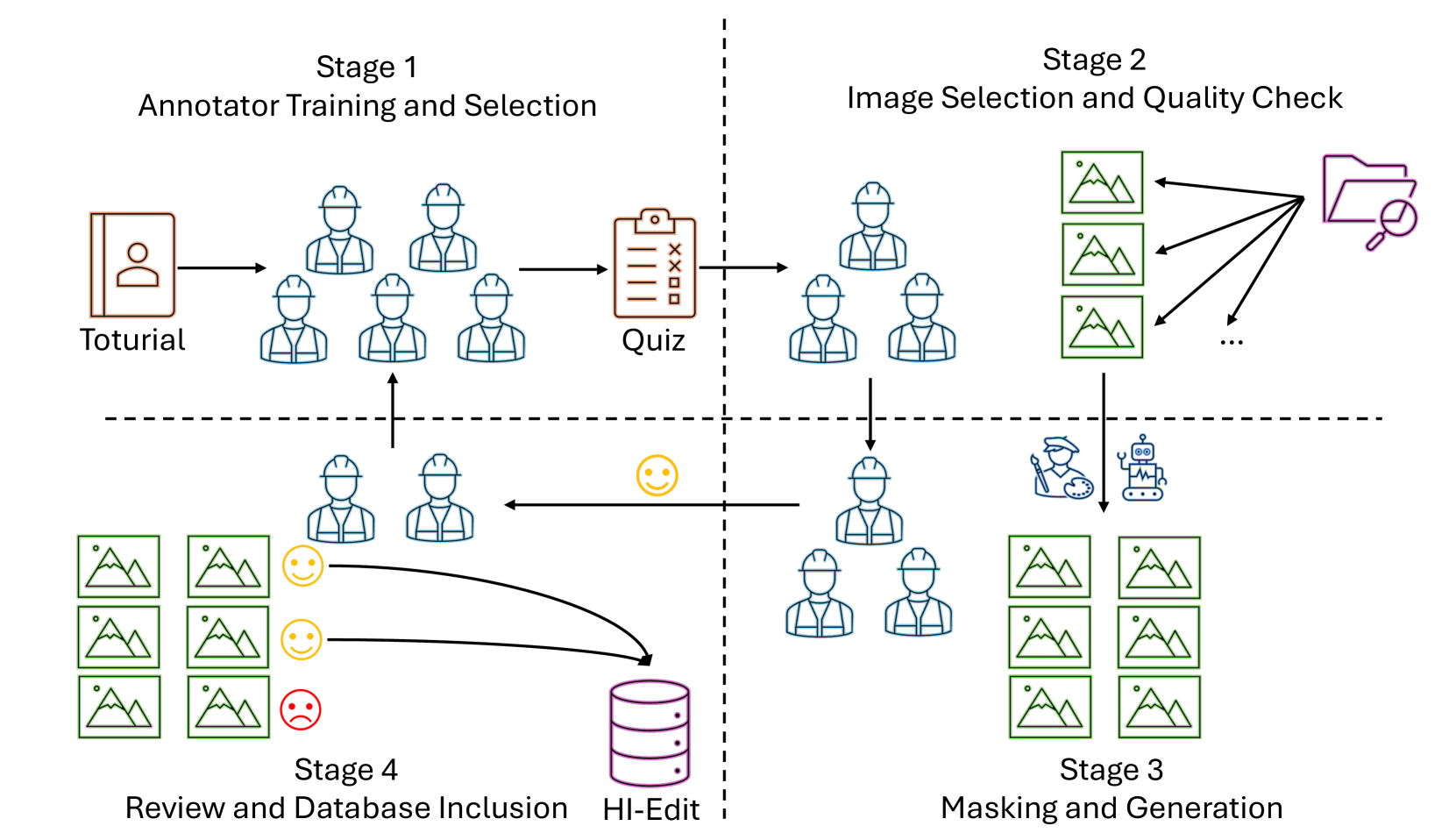

🔼 This figure illustrates the four-stage data collection process used to create the HumanEdit dataset. Stage 1 involves training and selecting annotators through a tutorial and quiz. Stage 2 focuses on selecting and quality-checking images sourced from Unsplash. In Stage 3, annotators create editing instructions, masks (where applicable), and generate edited images. Finally, Stage 4 includes a two-tier quality review and feedback process to ensure accuracy and consistency, resulting in the final HumanEdit dataset.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of data collection process.

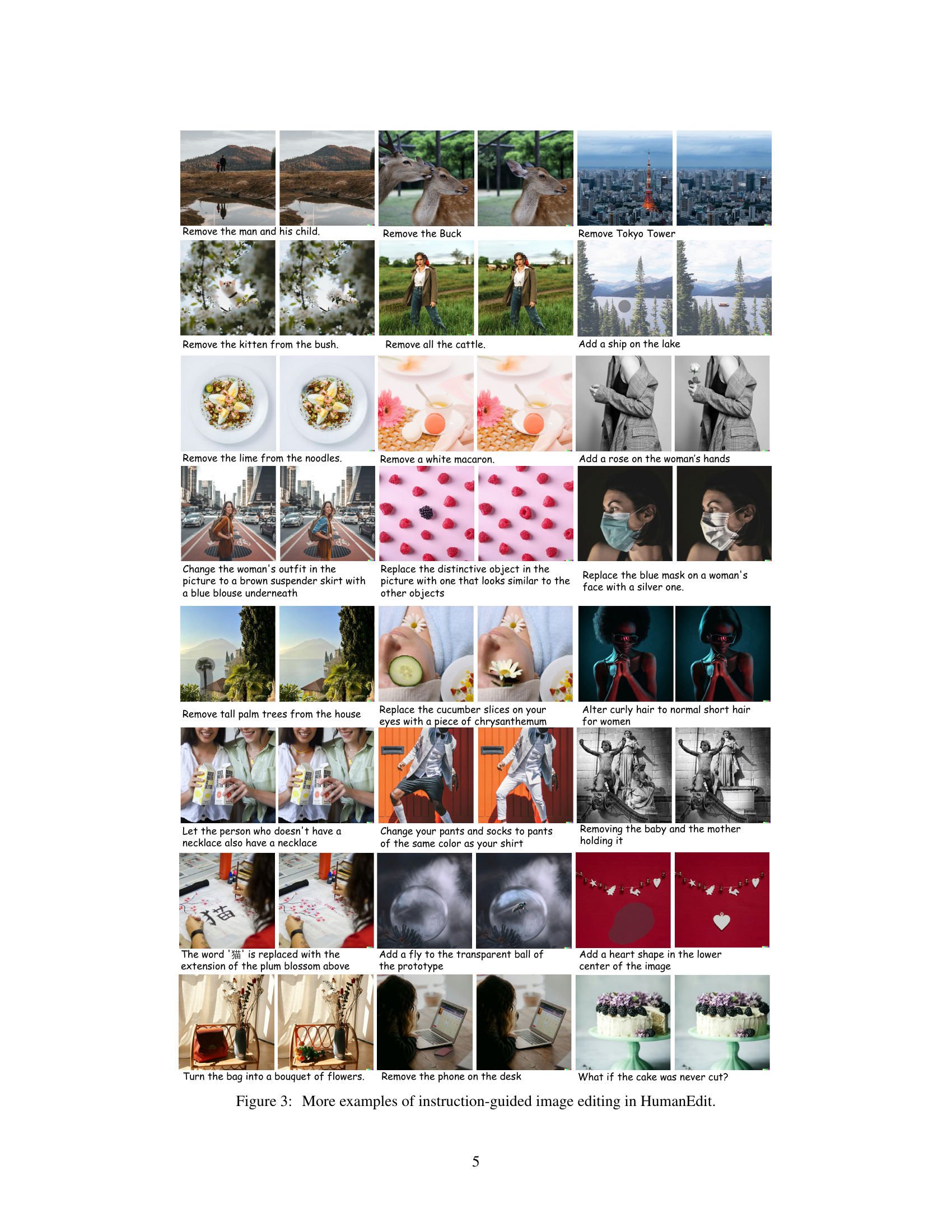

🔼 Figure 3 presents additional examples showcasing the diverse capabilities of HumanEdit for instruction-guided image editing. It visually demonstrates the wide range of edits the dataset encompasses, including adding, removing, replacing, changing actions of objects, counting and modifying relationships between objects within images. These examples highlight the realism and complexity of edits possible using the HumanEdit dataset, illustrating the detailed and nuanced instructions paired with the images.

read the caption

Figure 3: More examples of instruction-guided image editing in HumanEdit.

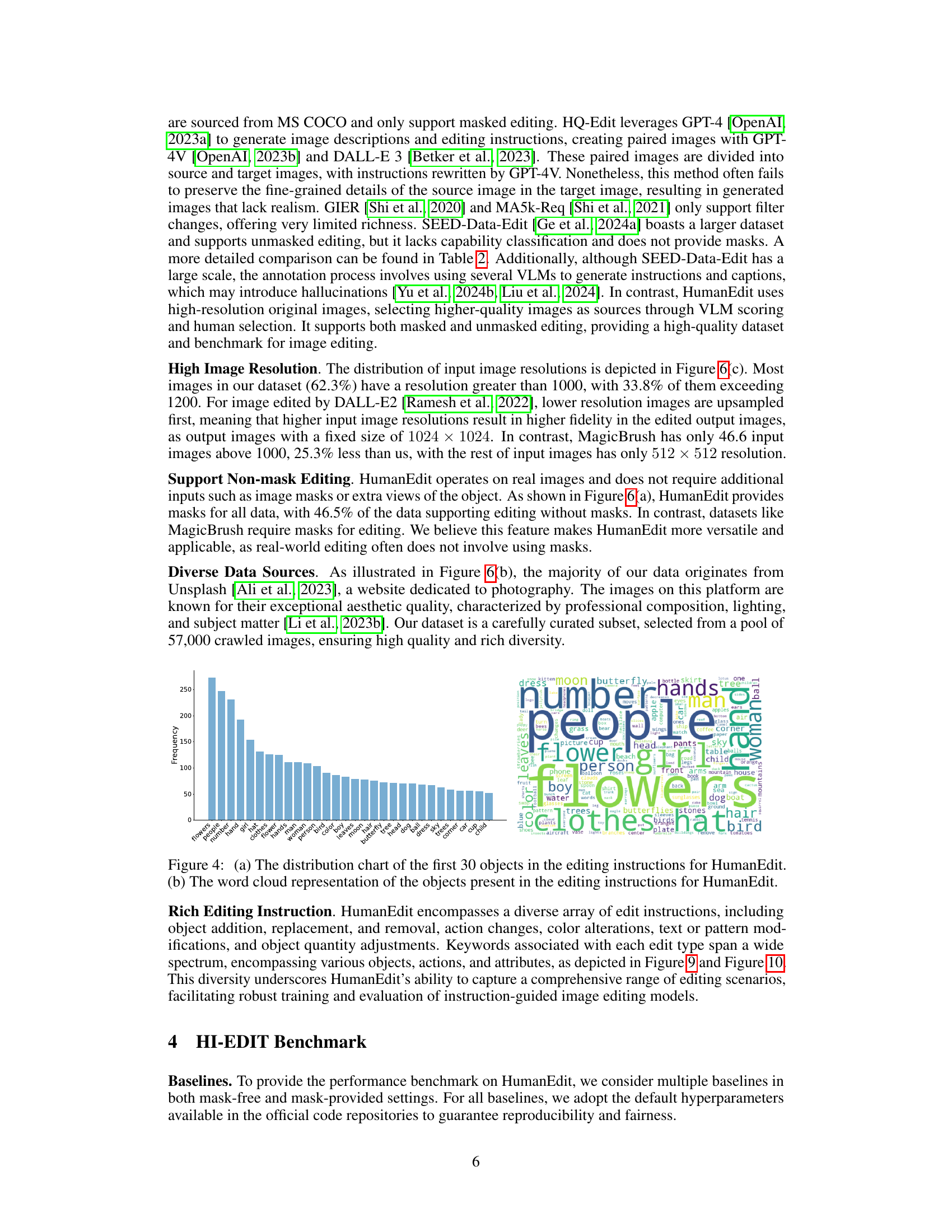

🔼 Figure 4 presents a dual visualization of the objects described within the editing instructions of the HumanEdit dataset. Panel (a) shows a distribution chart of the top 30 most frequent objects mentioned in these instructions, providing a quantitative view of object prevalence. Panel (b) offers a word cloud representation of all objects mentioned in the editing instructions, providing a qualitative and visual representation of the dataset’s object diversity and the relative frequency of object mentions. Together, the two panels offer insights into the types and frequency of objects involved in the image editing tasks of HumanEdit.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) The distribution chart of the first 30 objects in the editing instructions for HumanEdit. (b) The word cloud representation of the objects present in the editing instructions for HumanEdit.

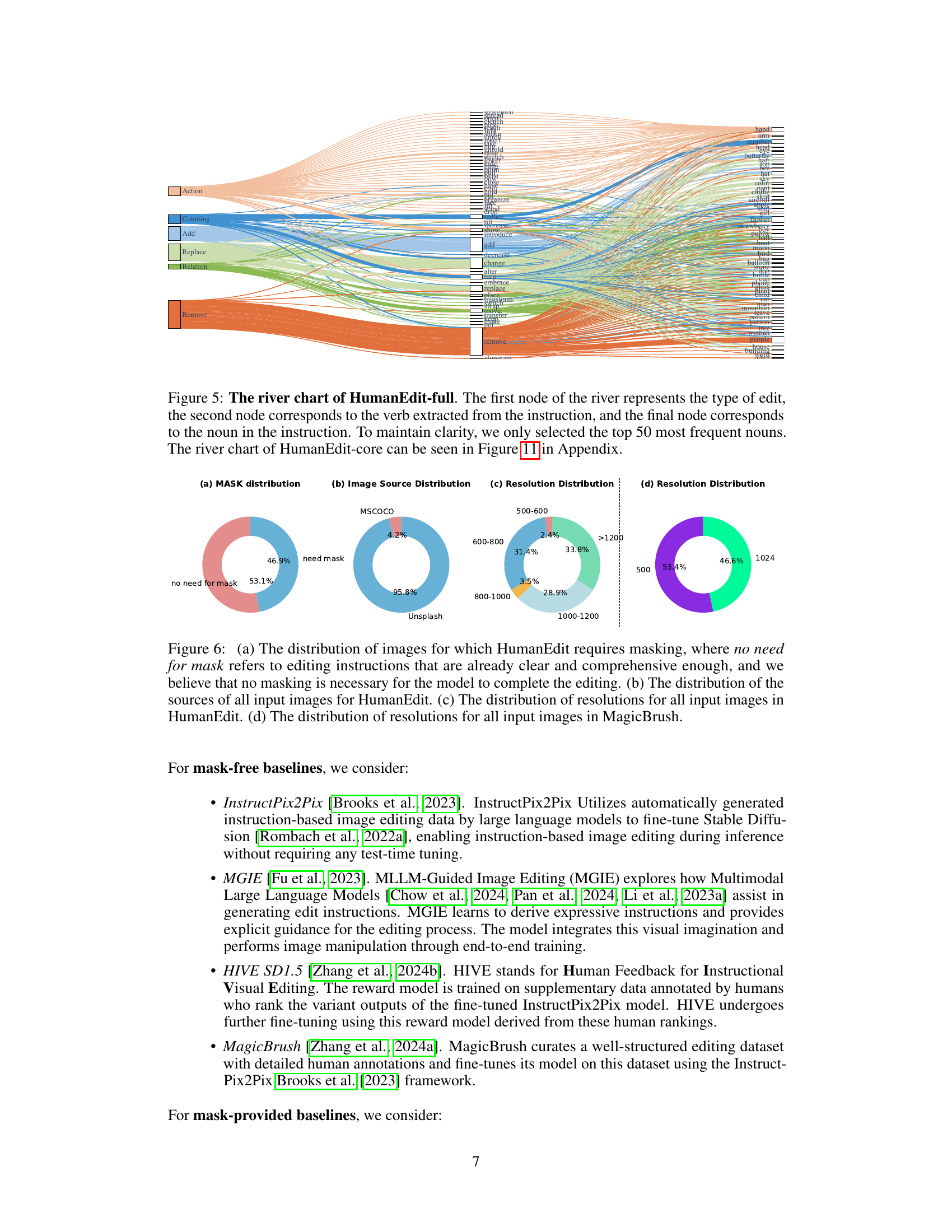

🔼 This river chart visualizes the relationships between different aspects of image editing instructions within the HumanEdit-full dataset. It shows three levels of detail: the type of edit (e.g., Add, Remove, Replace), the verb used in the instruction (e.g., add, remove, change), and the noun representing the object of the edit (e.g., flower, tree, person). The chart’s structure reveals common patterns in how users phrase editing instructions, highlighting frequently occurring combinations of edit type, verb, and noun. Only the top 50 most frequent nouns are included for clarity. A similar chart for the HumanEdit-core dataset is found in Figure 11 of the Appendix.

read the caption

Figure 5: The river chart of HumanEdit-full. The first node of the river represents the type of edit, the second node corresponds to the verb extracted from the instruction, and the final node corresponds to the noun in the instruction. To maintain clarity, we only selected the top 50 most frequent nouns. The river chart of HumanEdit-core can be seen in Figure 11 in Appendix.

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comprehensive analysis of HumanEdit and MagicBrush datasets through four subfigures: (a) Compares the necessity of masks in HumanEdit, showing a significant portion (53.1%) of instructions are detailed enough to allow mask-free editing. (b) Shows the diverse sources of images for HumanEdit, highlighting the predominance of Unsplash images. (c) Presents a distribution analysis of the resolutions of images within HumanEdit, indicating a majority (62.3%) possess resolutions above 1000 pixels. (d) Provides a comparative resolution analysis between HumanEdit and MagicBrush datasets, illustrating the superior resolution of HumanEdit.

read the caption

Figure 6: (a) The distribution of images for which HumanEdit requires masking, where no need for mask refers to editing instructions that are already clear and comprehensive enough, and we believe that no masking is necessary for the model to complete the editing. (b) The distribution of the sources of all input images for HumanEdit. (c) The distribution of resolutions for all input images in HumanEdit. (d) The distribution of resolutions for all input images in MagicBrush.

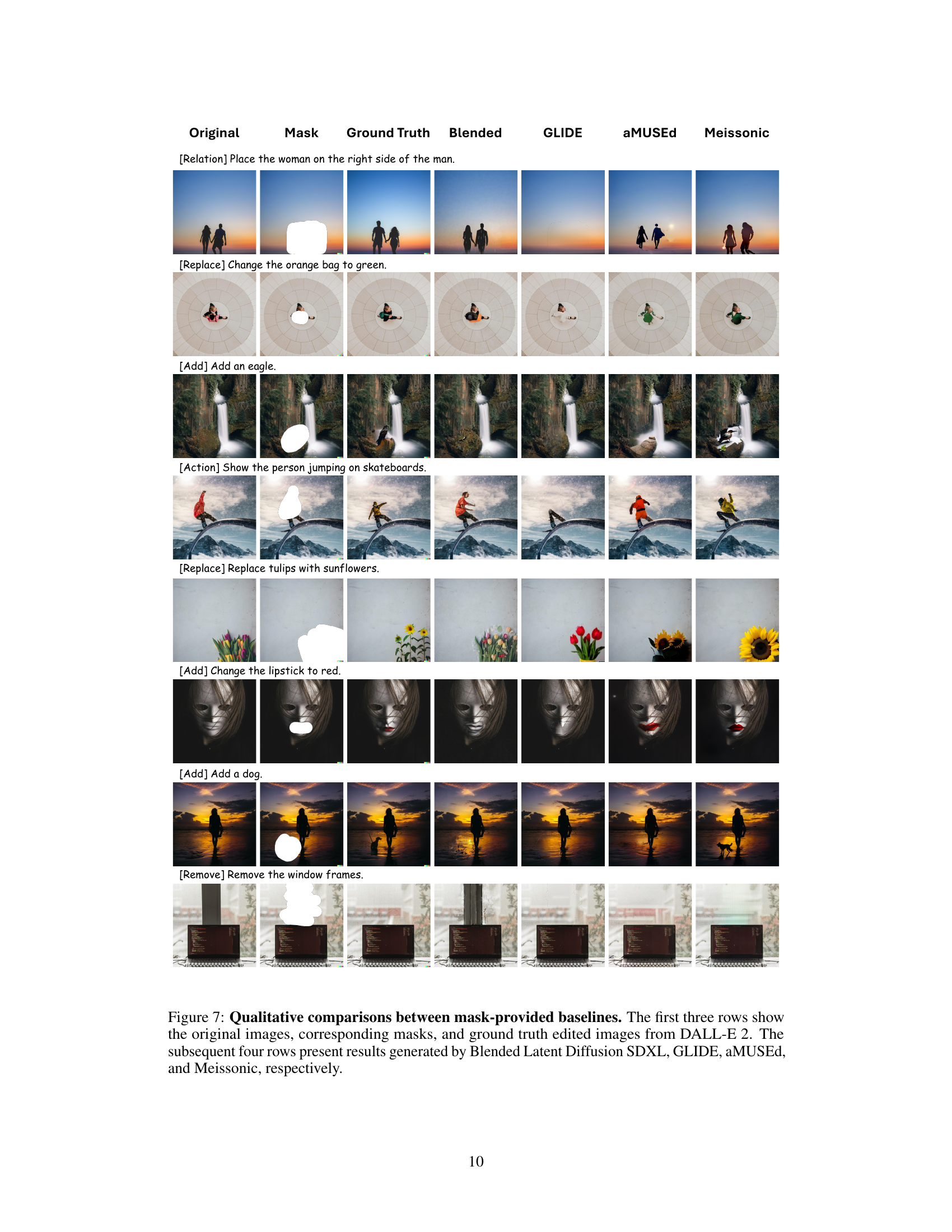

🔼 Figure 7 presents a qualitative comparison of different image editing models’ performance on a masked image editing task. The top three rows display the original image, the corresponding mask (the region to be edited), and the ground truth (desired) edited image created using DALL-E 2. The four rows below show the results obtained from four other state-of-the-art models: Blended Latent Diffusion SDXL, GLIDE, aMUSEd, and Meissonic. This allows for a visual assessment of each model’s ability to accurately and realistically modify the masked area of the image, based on implicit instructions.

read the caption

Figure 7: Qualitative comparisons between mask-provided baselines. The first three rows show the original images, corresponding masks, and ground truth edited images from DALL-E 2. The subsequent four rows present results generated by Blended Latent Diffusion SDXL, GLIDE, aMUSEd, and Meissonic, respectively.

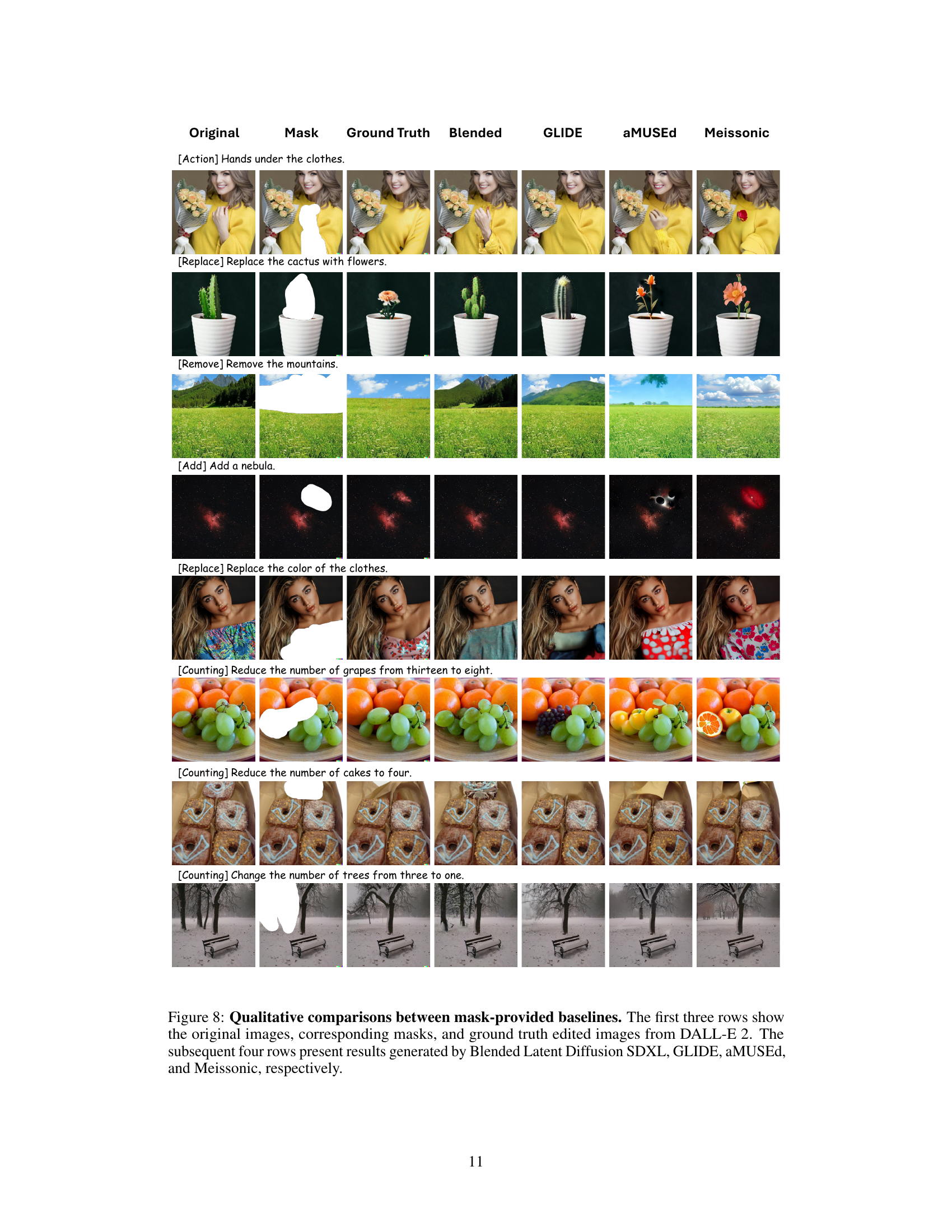

🔼 Figure 8 presents a qualitative comparison of different image editing models on a subset of the HumanEdit dataset. The top three rows display example images from the dataset: the original image, the corresponding mask indicating the region to be edited, and the ground truth result produced using DALL-E 2. The following four rows showcase how four other models, specifically Blended Latent Diffusion SDXL, GLIDE, aMUSEd, and Meissonic, performed on the same image editing tasks. This visual comparison highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each model in terms of accurately implementing the editing instructions and producing visually appealing results.

read the caption

Figure 8: Qualitative comparisons between mask-provided baselines. The first three rows show the original images, corresponding masks, and ground truth edited images from DALL-E 2. The subsequent four rows present results generated by Blended Latent Diffusion SDXL, GLIDE, aMUSEd, and Meissonic, respectively.

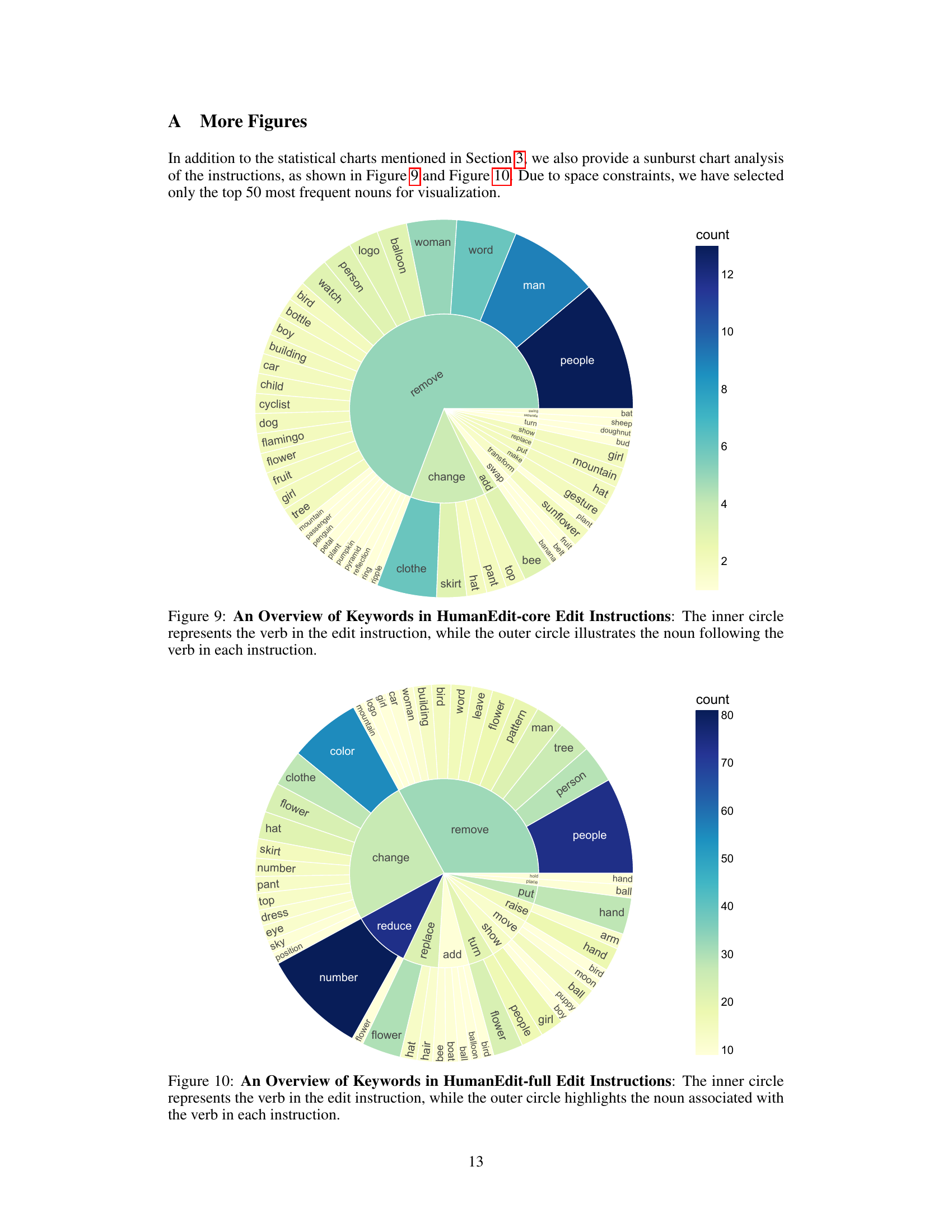

🔼 This figure is a sunburst chart visualizing the keywords used in the instructions of the HumanEdit-core dataset. The inner ring represents the action verbs used (e.g., ‘add’, ‘remove’, ‘change’), and the outer ring displays the nouns (objects) associated with each verb. This hierarchical structure helps demonstrate the relationship between the actions and objects in the dataset’s instruction set, providing insights into the types of editing operations and target elements prevalent within HumanEdit-core.

read the caption

Figure 9: An Overview of Keywords in HumanEdit-core Edit Instructions: The inner circle represents the verb in the edit instruction, while the outer circle illustrates the noun following the verb in each instruction.

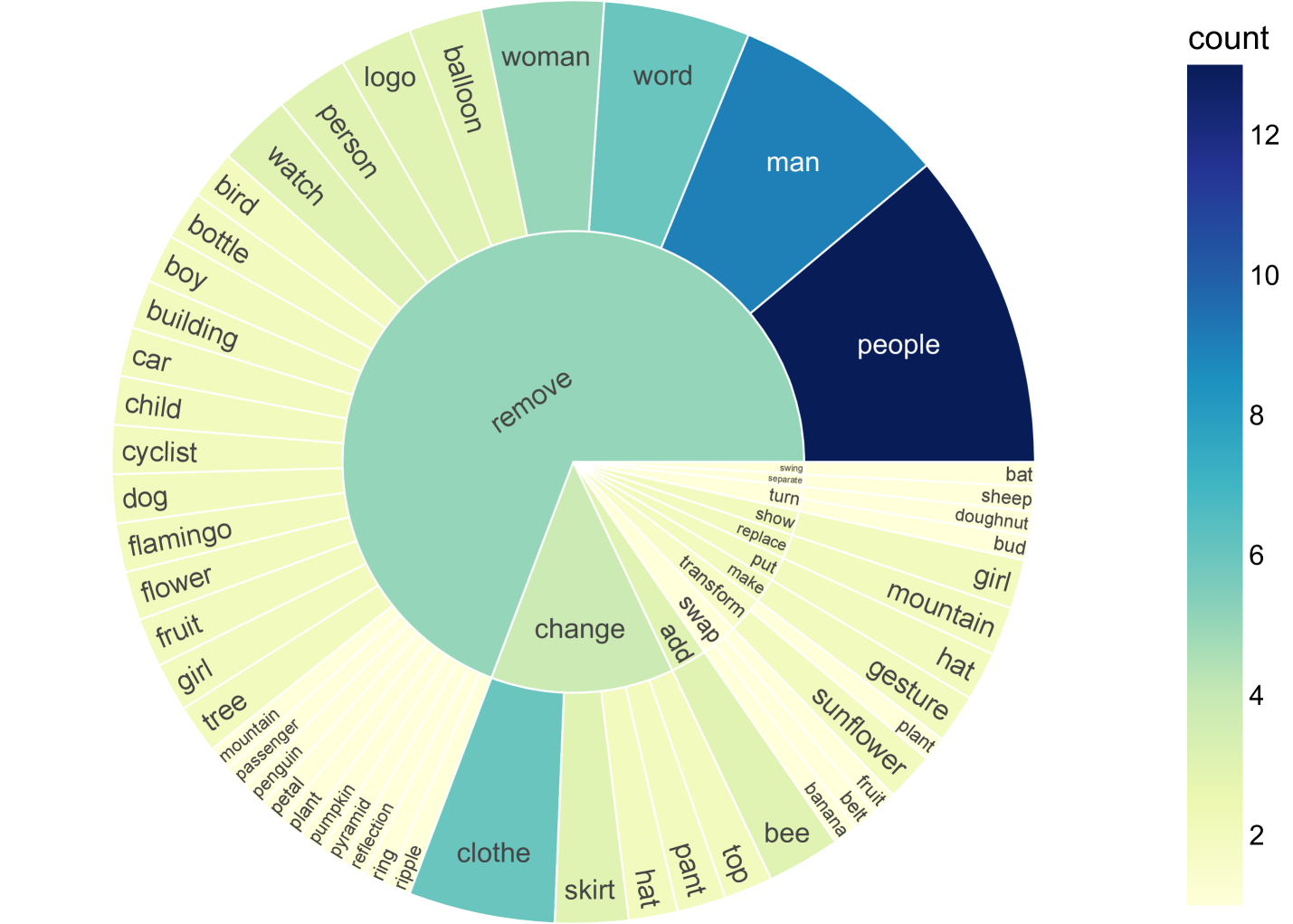

🔼 This figure is a sunburst chart visualizing the keywords used in the instructions of the HumanEdit-full dataset. The inner circle represents the verb (action word) from each instruction (e.g., ‘add’, ‘remove’, ‘replace’). The outer ring displays the nouns (objects) most frequently associated with those verbs. This provides a visual representation of the types of image editing operations included in the HumanEdit-full dataset and their object focus. It shows the relationship between verbs and nouns within image editing instruction.

read the caption

Figure 10: An Overview of Keywords in HumanEdit-full Edit Instructions: The inner circle represents the verb in the edit instruction, while the outer circle highlights the noun associated with the verb in each instruction.

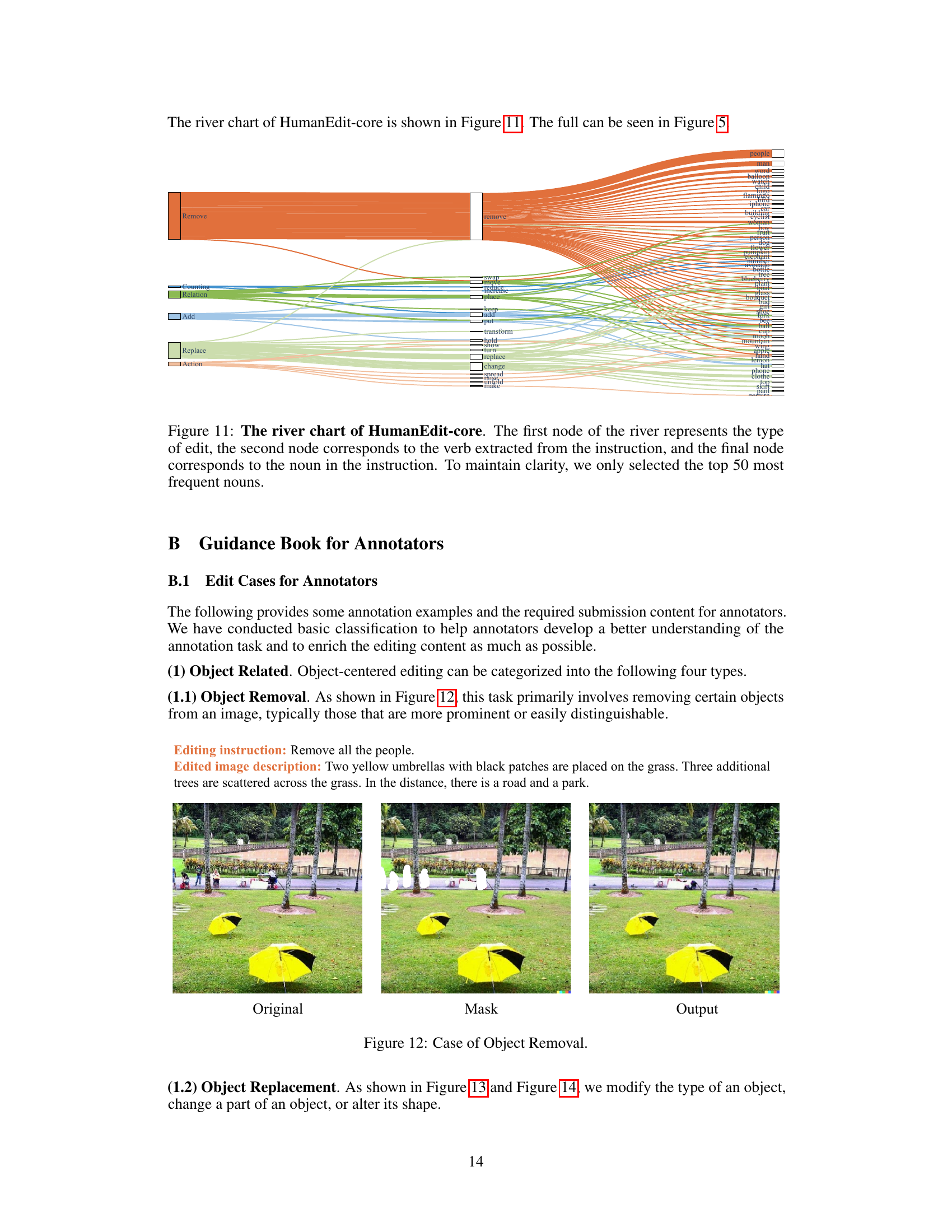

🔼 This river chart visualizes the relationships between different aspects of the editing instructions in the HumanEdit-core dataset. It shows the flow from the type of edit (e.g., Add, Remove, Replace) to the verb used in the instruction (e.g., add, remove, change), and finally to the most frequent nouns involved in the instruction (e.g., flower, person, car). This hierarchical representation helps to understand the distribution and common patterns in the image editing tasks described within the HumanEdit-core dataset. Only the top 50 most frequent nouns are included for clarity.

read the caption

Figure 11: The river chart of HumanEdit-core. The first node of the river represents the type of edit, the second node corresponds to the verb extracted from the instruction, and the final node corresponds to the noun in the instruction. To maintain clarity, we only selected the top 50 most frequent nouns.

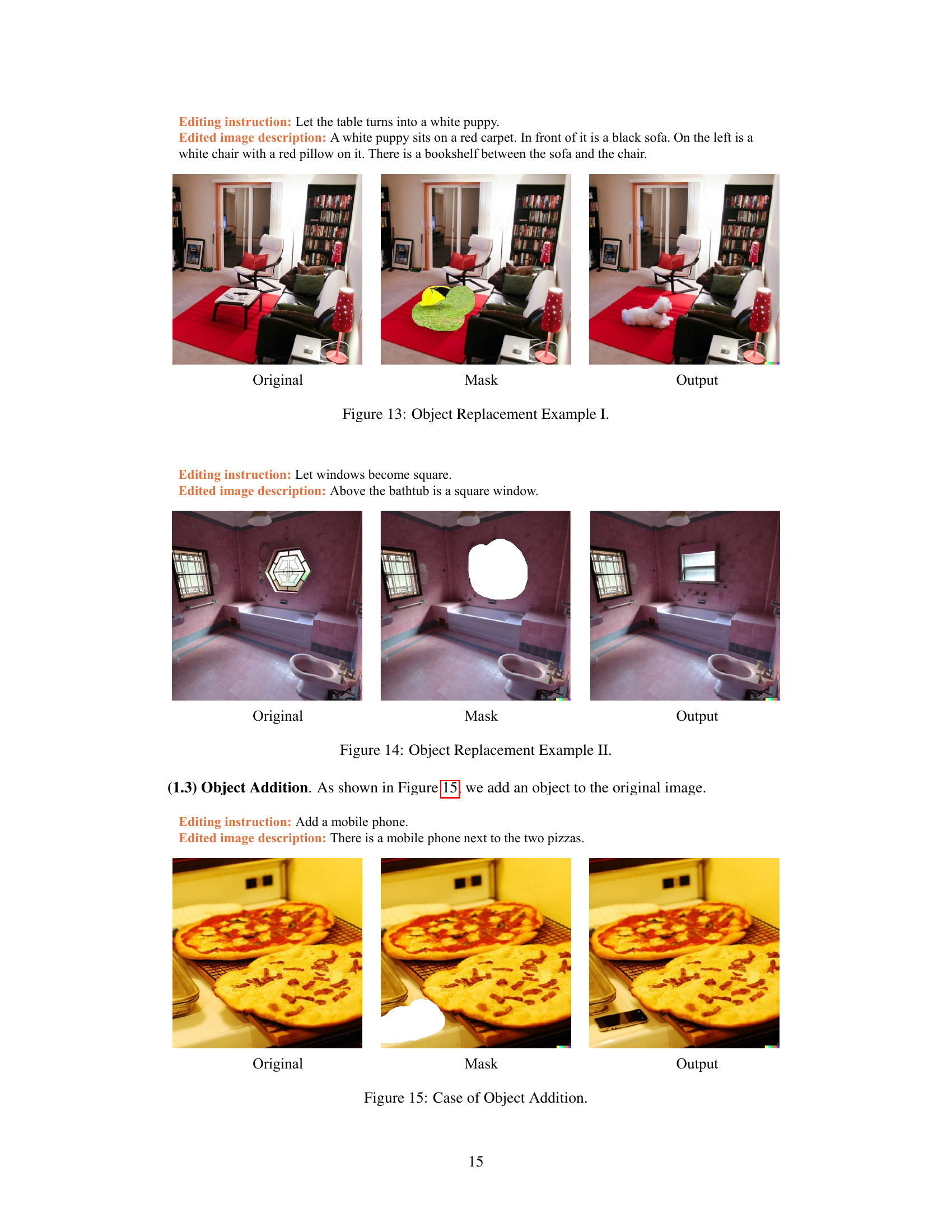

🔼 This figure shows an example of object removal from an image in the HumanEdit dataset. The original image contains multiple objects, including a yellow tent and trees. The mask highlights the area where the tent is located. The output image shows the tent has been successfully removed leaving only the background and trees.

read the caption

Figure 12: Case of Object Removal.

🔼 This figure shows an example of object replacement in image editing. The original image contains a wooden table with various items on it. The editing instruction is to replace the table with a white puppy. The mask highlights the area of the table. The output image shows a white puppy sitting where the table was, with the surrounding environment remaining the same.

read the caption

Figure 13: Object Replacement Example I.

🔼 This figure shows an example of object replacement in image editing. The original image shows a bathroom with a curved window above the bathtub. The mask highlights the window area for modification. The edited image replaces the curved window with a square window, demonstrating the successful application of the object replacement technique.

read the caption

Figure 14: Object Replacement Example II.

🔼 This figure shows an example of the ‘Object Addition’ category from the HumanEdit dataset. It illustrates how a new object (a mobile phone) is added to an existing image, demonstrating a typical instruction-guided image editing task included in the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 15: Case of Object Addition.

🔼 This figure shows an example of object counting change in the HumanEdit dataset. The original image contains one object, and the edited image contains four objects. This illustrates the type of editing task involving modifying the number of objects in a scene. The task involves increasing or decreasing the count of objects already present in the image, not adding objects that weren’t originally there, or removing them entirely (those would be classified as ‘add’ and ‘remove’ respectively). The number of objects cannot be changed from zero to a non-zero number or vice-versa.

read the caption

Figure 16: Case of Object Counting Change.

🔼 This figure shows an example of an image editing task where an action is changed. The original image shows an elephant. The mask highlights the elephant’s trunk. The edited image shows the elephant with its trunk raised.

read the caption

Figure 17: Case of Action Change.

🔼 This figure shows an example of relation change in image editing. The original image shows a cloth basket with gloves on the right and other items on the left. The edited image shows the same items but with the gloves moved from the right side to the left side of the basket, demonstrating a change in spatial relationship between objects.

read the caption

Figure 18: Case of Relation Change.

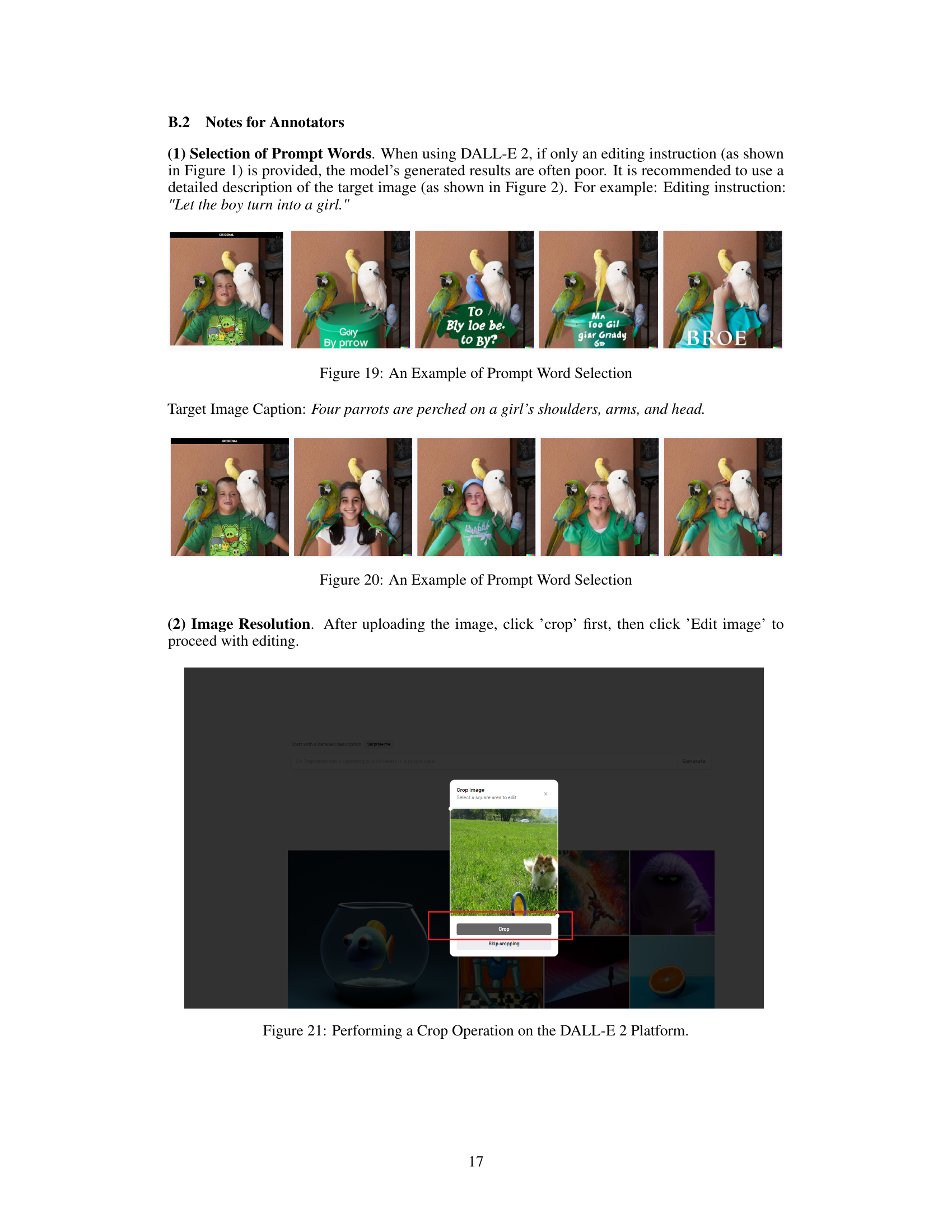

🔼 This figure shows an example of how to choose effective prompt words when using the DALL-E 2 platform for image editing. The top row displays various prompt word combinations, while the bottom row shows the images generated based on each prompt. The different images generated illustrate how different word choices can lead to different results. This highlights the importance of careful prompt selection for achieving desirable image editing outcomes.

read the caption

Figure 19: An Example of Prompt Word Selection

🔼 Figure 20 shows an example of selecting appropriate prompt words when using the DALL-E 2 platform for image editing. The image demonstrates the importance of using detailed and descriptive prompts to ensure that the model generates high-quality results that match the user’s intent. Using vague or incomplete prompts can lead to undesired or inaccurate edits. The figure showcases different word choices, highlighting how the selection impacts the generated images.

read the caption

Figure 20: An Example of Prompt Word Selection

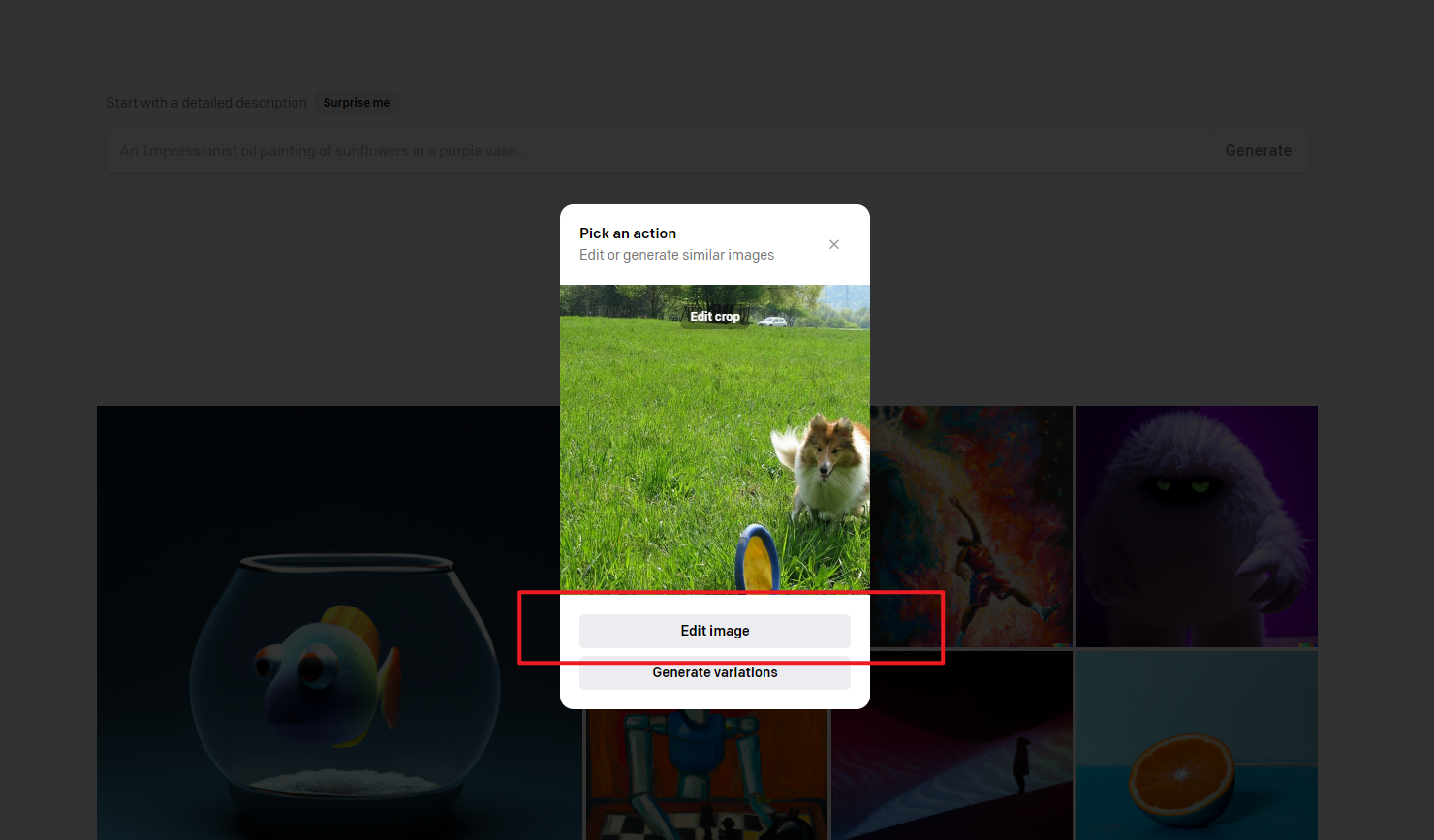

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the DALL-E 2 platform’s interface. The user is in the process of cropping an image before initiating an image editing task. The screenshot highlights the cropping tools and options available within the platform, illustrating one step in the image preparation workflow for instruction-guided image editing.

read the caption

Figure 21: Performing a Crop Operation on the DALL-E 2 Platform.

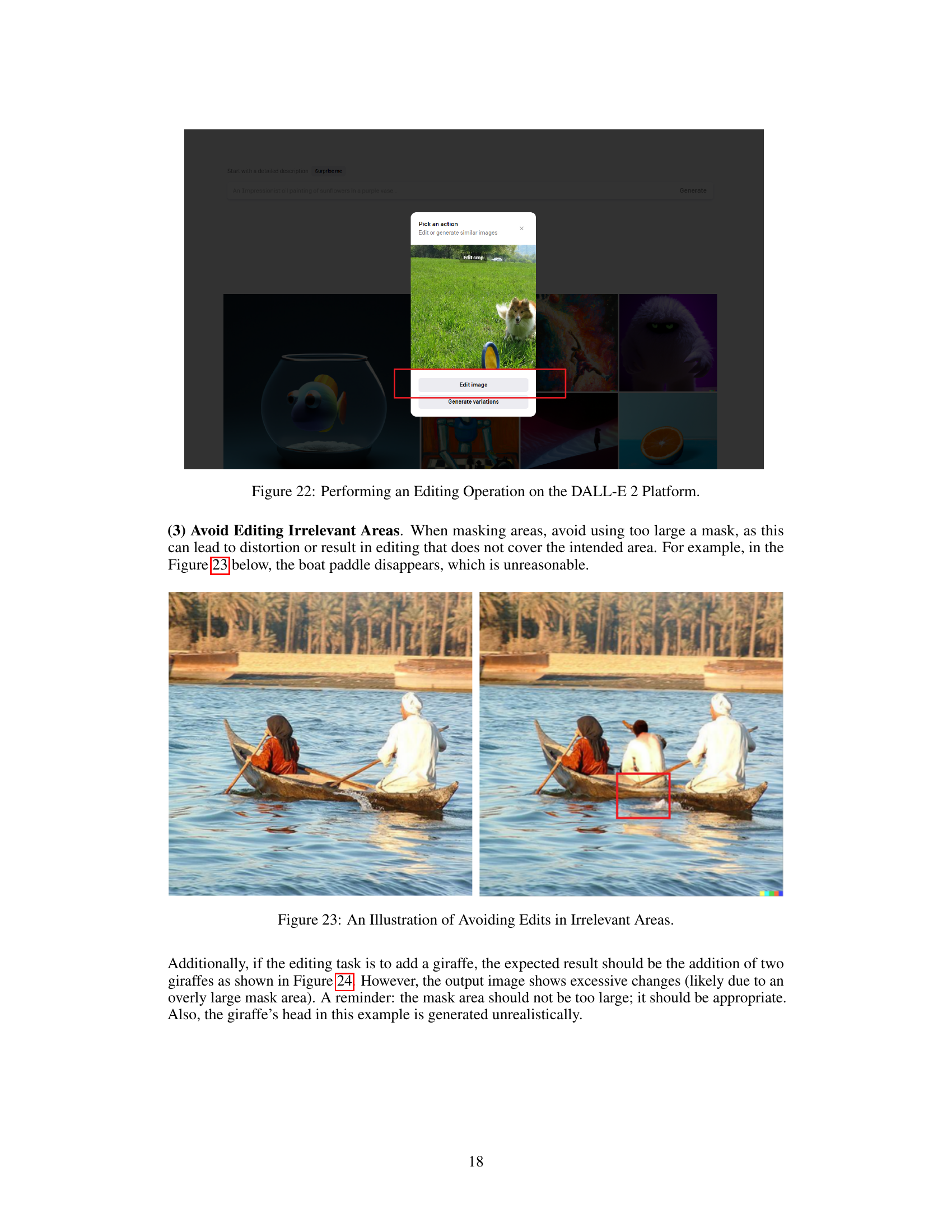

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the DALL-E 2 platform interface during an image editing operation. The user has selected an image and is presented with options to ‘Edit or generate similar images.’ The screenshot demonstrates the steps involved in using the platform for image editing, specifically highlighting the ‘Edit Image’ option.

read the caption

Figure 22: Performing an Editing Operation on the DALL-E 2 Platform.

🔼 The figure illustrates a common mistake in image editing where the mask used for editing is too large, encompassing unintended areas. This leads to undesirable and unintended edits. In this example, a mask used to alter a section of a photograph inadvertently removes a portion of a boat’s paddle. The instruction for this task is implied to only be applied to the people in the boat.

read the caption

Figure 23: An Illustration of Avoiding Edits in Irrelevant Areas.

🔼 This figure illustrates a common mistake in image editing tasks. The instruction is to add a giraffe to the scene, but the mask is too large, encompassing areas unrelated to the addition. This results in unwanted edits to parts of the image besides the desired addition of a giraffe. In particular, the generated giraffe’s head appears unnatural. The example highlights the importance of using precise masks that only target the intended editing area to prevent unexpected artifacts in the final image.

read the caption

Figure 24: An Illustration of Avoiding Edits in Irrelevant Areas.

🔼 The figure demonstrates a common mistake during image editing: selecting too large of a mask area. The instruction is to remove a person, but the selected mask includes a car. This highlights the importance of precise mask selection to avoid unwanted edits to irrelevant parts of the image. The example illustrates the effect of an improperly placed or sized mask in the DALL-E2 platform and the resulting unwanted changes to parts of the image outside the target edit area.

read the caption

Figure 25: An Illustration of Avoiding Edits in Irrelevant Areas.

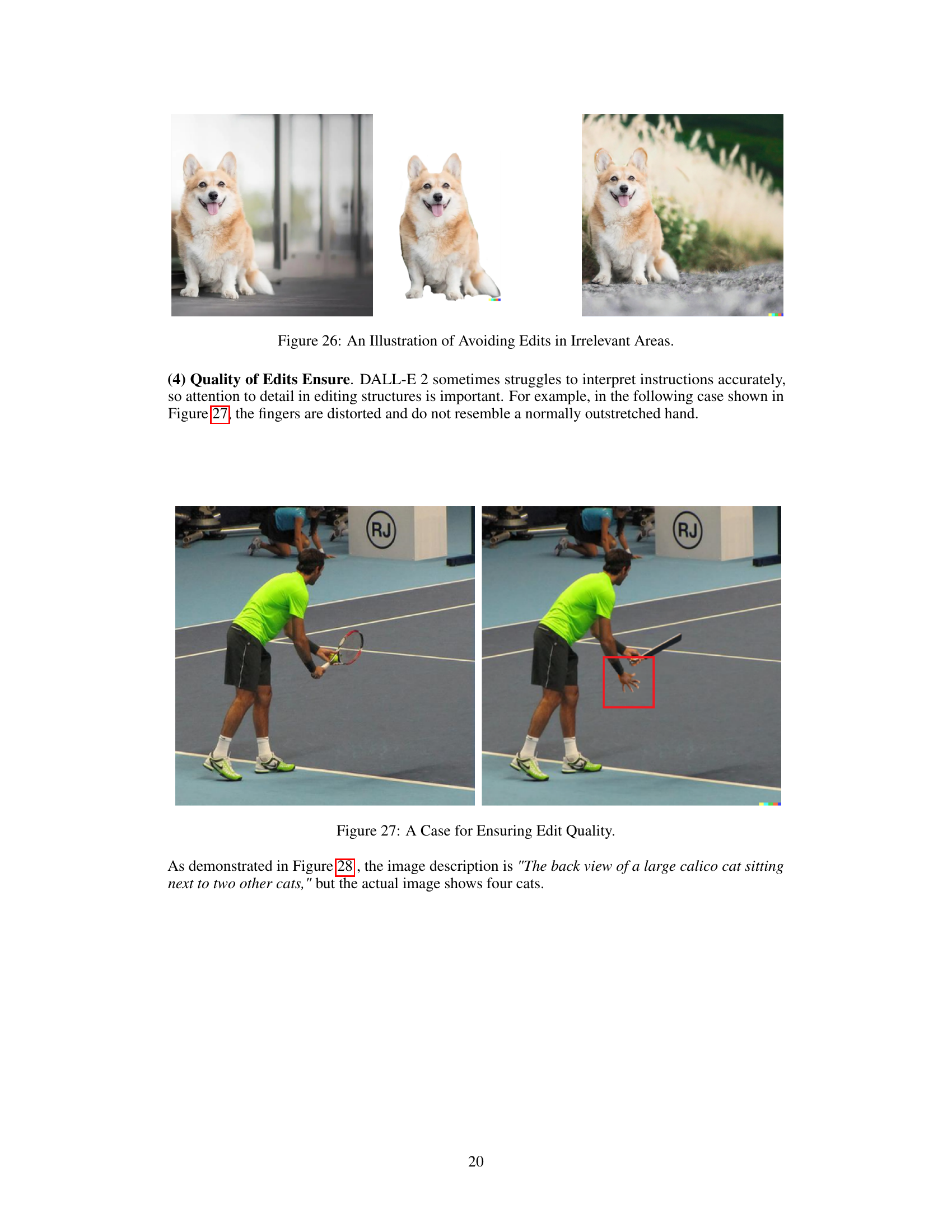

🔼 Figure 26 shows an example of proper masking in image editing. The instruction is to change the background of an image featuring a dog. The annotator correctly masked all areas except the dog itself, ensuring that only the background is altered during the editing process. This demonstrates how a properly masked area prevents unintended changes to the main subject of the image, resulting in more precise and accurate editing.

read the caption

Figure 26: An Illustration of Avoiding Edits in Irrelevant Areas.

🔼 The figure shows an example where DALL-E 2 struggles to accurately interpret the instruction to edit an image. Specifically, it shows an image where the instruction was to edit the hand in a tennis player’s image to be outstretched, but instead, DALL-E 2 distorted the fingers making it look unnatural and unrealistic. This highlights the importance of attention to detail in editing instructions to obtain high-quality edits.

read the caption

Figure 27: A Case for Ensuring Edit Quality.

🔼 The image shows a case where DALL-E 2 fails to accurately interpret editing instructions, resulting in an unrealistic outcome. The instruction intended to remove a person from the scene, but instead part of the car’s door also disappeared, highlighting a limitation of the model in precise object removal and maintaining realistic scene context.

read the caption

Figure 28: A Case for Ensuring Edit Quality.

🔼 The image shows a failure case from the HumanEdit dataset. The instruction was to remove a person from the scene, but DALL-E 2 also removed part of a car, resulting in an unrealistic and inconsistent edit. This highlights the challenges in ensuring high-quality results with instruction-based image editing models, and that excessive masking can lead to undesirable artifacts.

read the caption

Figure 29: A Case for Ensuring Edit Quality.

🔼 Figure 30 demonstrates the importance of maintaining stylistic consistency between the original image and its edited version. The original image is in black and white, showing a woman in a dark dress. The successful edits retain this black and white aesthetic, and changes are made without introducing color. Unsuccessful edits (marked with an X) fail to preserve the original style, resulting in a colorized or otherwise altered image. This highlights a key quality control aspect of the HumanEdit dataset, ensuring the edited images align with the original style to maintain data quality and consistency.

read the caption

Figure 30: An Illustration of Consistency in Style Before and After Editing.

🔼 Figure 31 showcases examples of images deemed valid or invalid for inclusion in the HumanEdit dataset. The first image is considered valid due to meeting the quality and resolution standards required by the HumanEdit dataset annotation pipeline. In contrast, the remaining three images are deemed invalid. Image (b) contains unusual artifacts, image (c) has poor image quality, and image (d) displays low resolution and lacks sufficient visual information; these flaws render them unsuitable for HumanEdit.

read the caption

Figure 31: Examples of valid and invalid images. The first image is valid, while the following three images are invalid.

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the DALL-E 2 platform’s interface. The user is presented with options to either start with a detailed description or upload an image. To proceed with uploading an image, the user should click the ‘Try DALL-E’ button. This step is the initial stage of using the DALL-E 2 platform for image editing within the HumanEdit dataset creation process.

read the caption

Figure 32: Log in to the DALL·E 2 platform and click 'Try DALL-E' to upload an image.

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the DALL-E 2 platform’s interface after an image has been uploaded. The user is presented with a cropping tool to select the desired area of the image for editing. This step is crucial because it allows the user to focus on the specific part of the image they want to modify, ensuring precise and effective edits with the DALL-E 2’s editing tools. The cropping stage refines the area of interest prior to applying editing instructions or generating variations.

read the caption

Figure 33: After uploading the image, a cropping page will be displayed.

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the DALL-E 2 platform’s editing interface. After uploading an image and performing a crop, the user clicks the ‘Edit’ button to proceed to the next stage of the image editing process, where they can provide editing instructions and a mask (if needed).

read the caption

Figure 34: Click the 'Edit' button to enter the editing window.

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the DALL-E 2 platform’s image editing interface. The user is in the process of selecting a region of the image to edit. Using a rectangular selection tool, the user is dragging the selection points to define the area that will be the focus of subsequent editing instructions.

read the caption

Figure 35: Drag the editing points to select the area to be edited.

🔼 This figure shows a screenshot of the DALL-E 2 platform’s image editing interface. The user is in the process of adding instructions for an image edit. A mask has already been applied to a region of the image. The user is about to type detailed instructions into the text box to guide the AI in creating the desired edit. The interface includes options for selecting the editing area using a mask and inputting the desired edits through natural language.

read the caption

Figure 36: Input the editing instructions in the text bo.

🔼 This figure shows the results of using the DALL-E 2 platform to generate edited images based on user-provided instructions and mask. The user has input an instruction and selected an area of the image to modify. The platform then generates several versions of the edited image, showcasing the capabilities of the model to make changes according to user specifications.

read the caption

Figure 37: Generate edited images.

🔼 This figure shows the results of regenerating edited images using the DALL-E 2 platform. The initial attempt at image editing yielded unsatisfactory results, so the user employed the platform’s ‘regenerate’ function to produce alternative versions. The images illustrate the iterative process of refining image edits, where the original prompt may need to be modified or made more precise to achieve desired results.

read the caption

Figure 38: Regenerate edited images.

🔼 The figure displays multiple image generation attempts from the DALL-E 2 platform. The user is trying to create an image of a girl with four parrots perched on her. Despite multiple attempts using the ‘regenerate’ function, the results are still unsatisfactory and fall short of meeting the specified requirements. The parrots’ positioning and overall image quality need improvement, illustrating that even with a detailed description, generating a precisely desired image using AI can be challenging and require careful refinement of instructions.

read the caption

Figure 39: Regenerated images are still not satisfactory and may require revised instructions.

🔼 This figure shows the final step of the image editing process using the DALL-E 2 platform. After generating multiple edited images based on the user’s instructions, the user selects the most satisfactory result and clicks the download button. This action concludes the annotation task for that particular image.

read the caption

Figure 40: Download and finish the editing process.

🔼 Figure 41 showcases examples of unsatisfactory image editing results generated by DALL-E 2. These examples highlight common issues such as a parrot incorrectly perched on another parrot, facial distortions, and an unrealistic depiction of a blue parrot seemingly suspended in mid-air. These examples are used to illustrate common errors that should be avoided during the image editing and annotation process to maintain high data quality.

read the caption

Figure 41: Defective Image Example.

🔼 Figure 42 shows an example of the materials that annotators need to submit as a group to the platform. It includes four columns: the original image before editing, the mask used during editing, the editing instruction provided, the expected image description, and the final edited image.

read the caption

Figure 42: Submission Example.

🔼 The figure showcases an example where the instruction given to DALL-E 2 was to ‘make the nose larger.’ However, the model failed to apply this modification to the image. This demonstrates a case of mismatch between the intended editing outcome (as described in the instruction) and the actual result produced by the AI model. Such discrepancies highlight the limitations of current image editing AI models in accurately interpreting and implementing specific instructions for image manipulation.

read the caption

Figure 43: An Illustration of the Mismatch Between Editing Results and Instructions.

🔼 The figure shows an example where the instruction ‘a lantern hanging in front of the window’ was given to DALL-E 2. However, instead of adding a lantern, DALL-E 2 simply removed the existing object without replacing it with a lantern, demonstrating a mismatch between the intended editing and the actual result. This highlights a limitation of DALL-E 2’s editing capabilities where the model sometimes fails to follow the instructions accurately.

read the caption

Figure 44: An Illustration of the Mismatch Between Editing Results and Instructions.

🔼 This figure shows an example where the instruction given to DALL-E 2 was to generate an image containing ‘a plate of cucumbers and a bouquet of roses’. However, the generated image only includes cucumbers; the roses, as specified in the instruction, are missing. This illustrates a mismatch between the user’s instruction and the model’s output, highlighting a limitation of DALL-E 2’s ability to reliably fulfill complex image editing requests.

read the caption

Figure 45: An Illustration of the Mismatch Between Editing Results and Instructions.

🔼 This figure shows an example where DALL-E 2 struggles with a specific type of editing task, highlighting its limitations. The instruction was to have a girl standing on tiptoe. Despite numerous attempts, the model failed to accurately achieve the desired effect, illustrating the limitations of the model in handling subtle or complex actions related to human poses. This showcases a failure case from the dataset where such a result would have been excluded because it didn’t meet quality standards.

read the caption

Figure 46: An Illustration of the Limited Editing Capabilities for Specific Types.

🔼 This figure shows several attempts to edit an image of an owl’s face, specifically aiming to make the owl close its eyes. Despite numerous attempts using the DALL-E 2 model, the results were inconsistent and unsuccessful in achieving the desired effect, consistently altering the state of the owl’s eyes without achieving the objective of closing them. This highlights the limited editing capabilities of the model for specific types of tasks or images.

read the caption

Figure 47: An Illustration of the Limited Editing Capabilities for Specific Types.

🔼 This figure illustrates the limitations of DALL-E 2 in performing specific types of image editing tasks. Specifically, it shows examples where the instruction was to add a red barbell, yet the model struggled to add the barbell accurately, either omitting the object or decreasing the number of objects present. This demonstrates the model’s insensitivity to object count and its limitations in reliably executing addition-based edit instructions.

read the caption

Figure 48: An Illustration of the Limited Editing Capabilities for Specific Types.

🔼 This figure showcases examples where DALL-E 2 struggles with specific types of editing tasks. It demonstrates limitations in its ability to precisely manipulate image details according to nuanced instructions. The examples highlight difficulties in tasks such as subtly shifting object positions or modifying counts of items. It visually reinforces the limitations of current image editing models, especially when dealing with fine-grained control over image content.

read the caption

Figure 49: An Illustration of the Limited Editing Capabilities for Specific Types.

🔼 Figure 50 shows an example where DALL-E 2 struggles with a specific type of editing task. The instruction likely involved a subtle change to an object’s characteristics or its relation to other elements in the image. The generated images demonstrate DALL-E 2’s inability to consistently and accurately perform this kind of fine-grained edit. This highlights the inherent limitations of current image editing models in handling certain types of instructions.

read the caption

Figure 50: An Illustration of the Limited Editing Capabilities for Specific Types.

🔼 Figure 51 shows several examples where DALL-E 2 struggles to perform edits, specifically focusing on limitations with editing certain types of content. The examples highlight the model’s inconsistencies and challenges in achieving the desired edits precisely, especially when dealing with complex or nuanced instructions. These examples are part of the failure cases presented in the paper, showing limitations of the DALL-E 2 model that were not included in the final HumanEdit dataset.

read the caption

Figure 51: An Illustration of the Limited Editing Capabilities for Specific Types.

🔼 Figure 52 shows examples where DALL-E 2 struggles to perform nuanced edits, specifically highlighting its limitations in handling certain types of content. The model’s ability to accurately and consistently modify aspects of an image is inconsistent in this case. This illustrates that while DALL-E 2 may handle simpler editing tasks well, more complex or subtle instructions present significant challenges. The figure serves as an example of inherent limitations in the model’s capabilities that would not make these images suitable for inclusion in the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 52: An Illustration of the Limited Editing Capabilities for Specific Types.

🔼 In Figure 53, the generated image from DALL-E 2 exhibits distortion in the flower’s petals. The editing instruction likely aimed to add or modify a pattern on the flower, but the execution resulted in an unnatural, warped appearance of the flower petals, demonstrating limitations in the model’s ability to precisely execute fine-grained image manipulations.

read the caption

Figure 53: An example of object distortion.

🔼 This figure in the HumanEdit paper showcases a failure case where the DALL-E 2 model did not correctly implement the given instruction. The instruction was to add a printed pattern to the image, however, the model failed to do so and produced an image that is identical to the original one.

read the caption

Figure 54: The discrepancy between the instruction and the generated image.

🔼 The image showcases a subtle editing effect where the instruction was likely to make the dog’s ears stand up. However, the result shows only a very slight change and may not be noticeable to the casual observer. This exemplifies a limitation of the DALL-E 2 model’s ability to execute fine-grained instructions precisely.

read the caption

Figure 55: An example of subtle editing effects.

More on tables

| Dataset | Real Image for Edit | Real-world Scenario | Human | Ability Classification | Mask | Non-Mask Editing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| GIER (Shi et al., 2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MA5k-Req (Shi et al., 2021) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| TEdBench (Kawar et al., 2023) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| HQ-Edit (Hui et al., 2024) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| SEED-Data-Edit (Ge et al., 2024a) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| AnyEdit (Yu et al., 2024a) | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

| HumanEdit | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ✓ | ✓ |

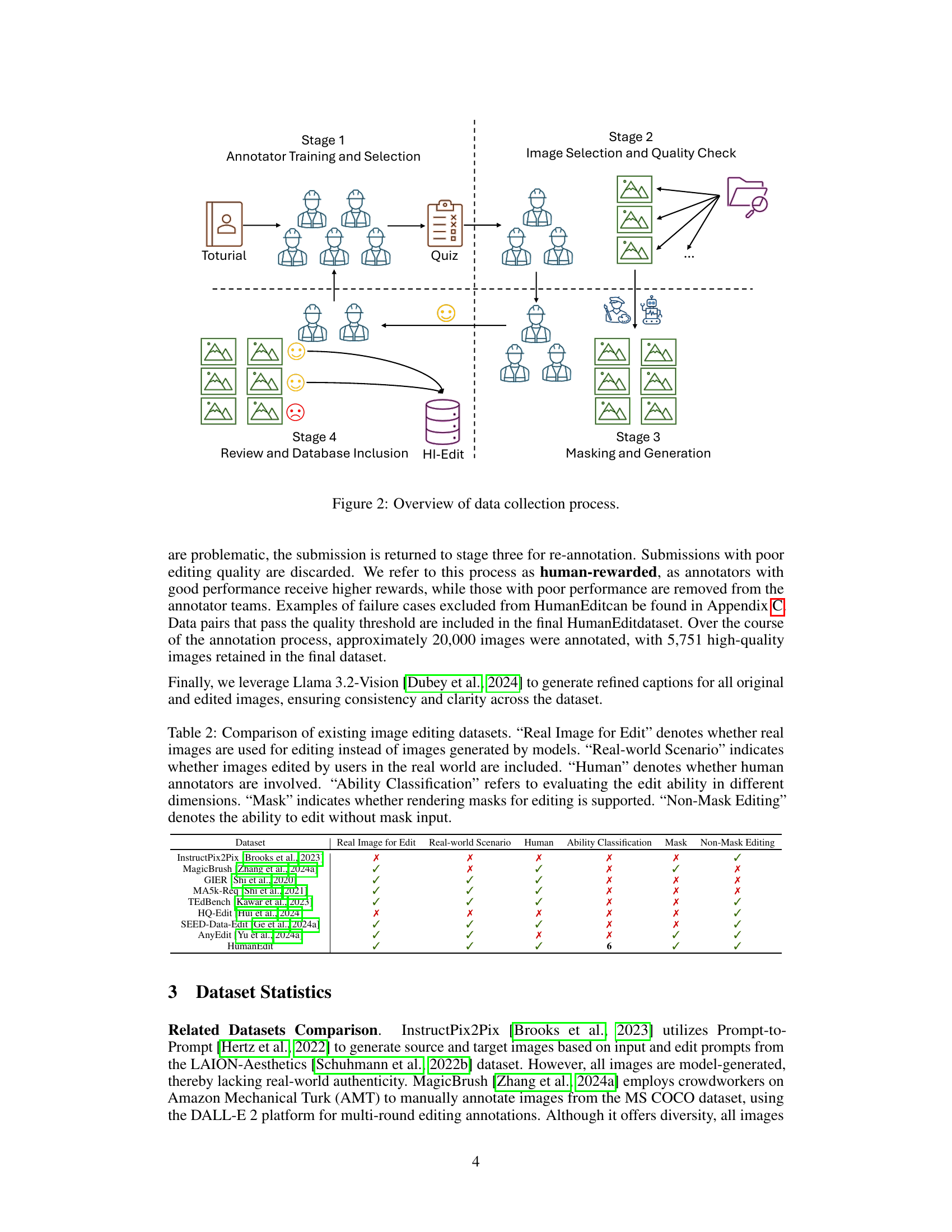

🔼 This table compares several existing image editing datasets across key characteristics. It highlights whether the datasets use real-world images as opposed to model-generated ones, whether they incorporate edits performed by real users, and the level of human involvement in the annotation process. The comparison also includes information about whether the datasets categorize edits into distinct dimensions (ability classification), whether masks are provided to support editing, and whether mask-free editing is possible.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of existing image editing datasets. “Real Image for Edit” denotes whether real images are used for editing instead of images generated by models. “Real-world Scenario” indicates whether images edited by users in the real world are included. “Human” denotes whether human annotators are involved. “Ability Classification” refers to evaluating the edit ability in different dimensions. “Mask” indicates whether rendering masks for editing is supported. “Non-Mask Editing” denotes the ability to edit without mask input.

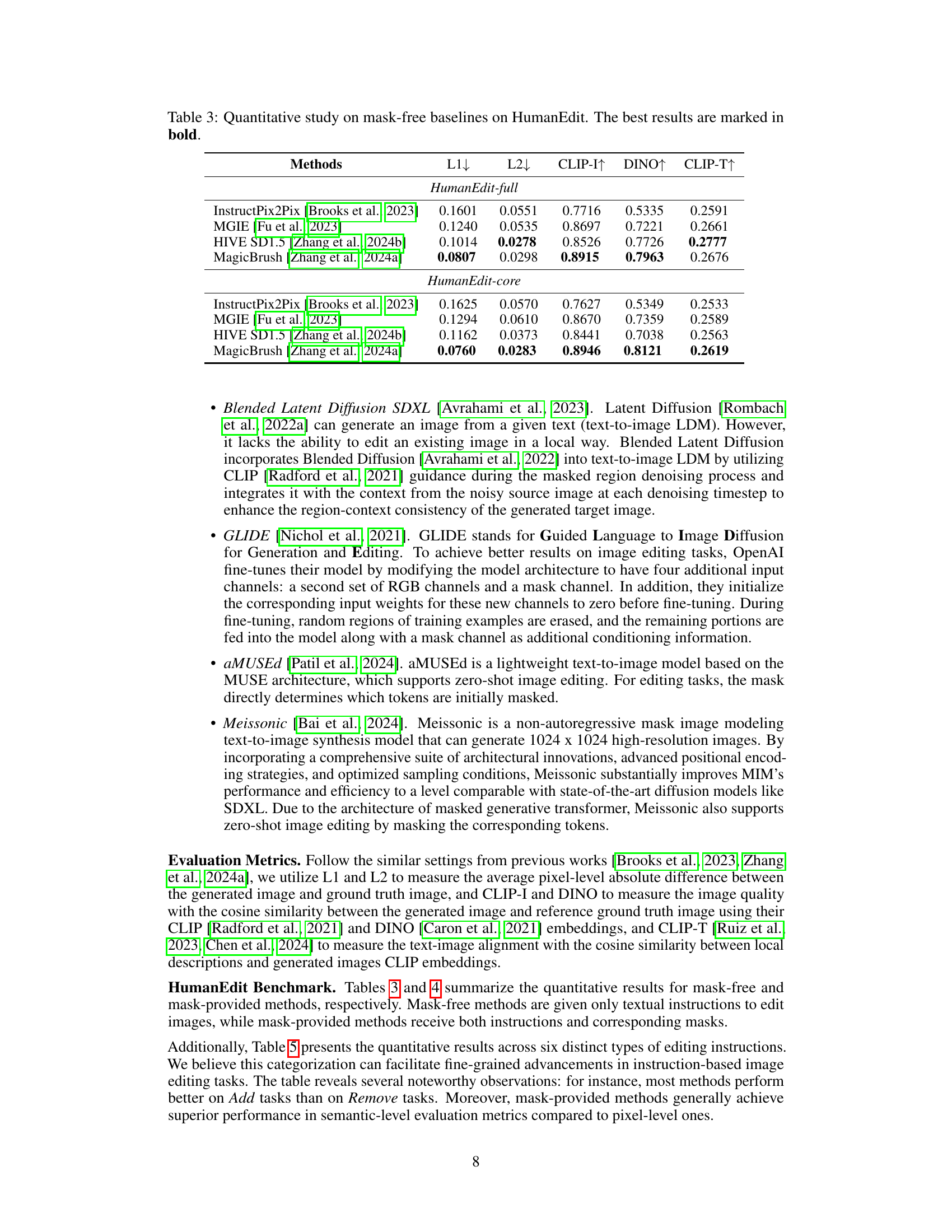

| Methods | L1↓ | L2↓ | CLIP-I↑ | DINO↑ | CLIP-T↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HumanEdit-full | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1601 | 0.0551 | 0.7716 | 0.5335 | 0.2591 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.1240 | 0.0535 | 0.8697 | 0.7221 | 0.2661 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.1014 | 0.0278 | 0.8526 | 0.7726 | 0.2777 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.0807 | 0.0298 | 0.8915 | 0.7963 | 0.2676 |

| HumanEdit-core | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1625 | 0.0570 | 0.7627 | 0.5349 | 0.2533 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.1294 | 0.0610 | 0.8670 | 0.7359 | 0.2589 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.1162 | 0.0373 | 0.8441 | 0.7038 | 0.2563 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.0760 | 0.0283 | 0.8946 | 0.8121 | 0.2619 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of several mask-free baselines on the HumanEdit dataset. The baselines are evaluated using five metrics: L1 loss, L2 loss, CLIP-I similarity, DINO similarity, and CLIP-T similarity. Lower is better for L1 and L2 loss, while higher is better for the similarity metrics. The results are presented for two subsets of the HumanEdit dataset: HumanEdit-full and HumanEdit-core, allowing for a comparison of performance across different dataset scales and complexities. The best performing model for each metric in each dataset subset is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 3: Quantitative study on mask-free baselines on HumanEdit. The best results are marked in bold.

| Methods | L1 ↓ | L2 ↓ | CLIP-I ↑ | DINO ↑ | CLIP-T ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HumanEdit-full | |||||

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0481 | 0.0151 | 0.9178 | 0.8481 | 0.2681 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0391 | 0.0120 | 0.9388 | 0.8800 | 0.2676 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0673 | 0.0187 | 0.9149 | 0.8588 | 0.2771 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0627 | 0.0177 | 0.9324 | 0.8806 | 0.2710 |

| HumanEdit-core | |||||

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0496 | 0.0162 | 0.9116 | 0.8550 | 0.2640 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0379 | 0.0113 | 0.9413 | 0.8961 | 0.2656 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0665 | 0.0184 | 0.9138 | 0.8743 | 0.2747 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0608 | 0.0166 | 0.9348 | 0.8943 | 0.2694 |

| HumanEdit-mask | |||||

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0478 | 0.0154 | 0.9065 | 0.8223 | 0.2650 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0377 | 0.0117 | 0.9343 | 0.8687 | 0.2665 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0654 | 0.0179 | 0.9097 | 0.8497 | 0.2785 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0604 | 0.0166 | 0.9303 | 0.8783 | 0.2715 |

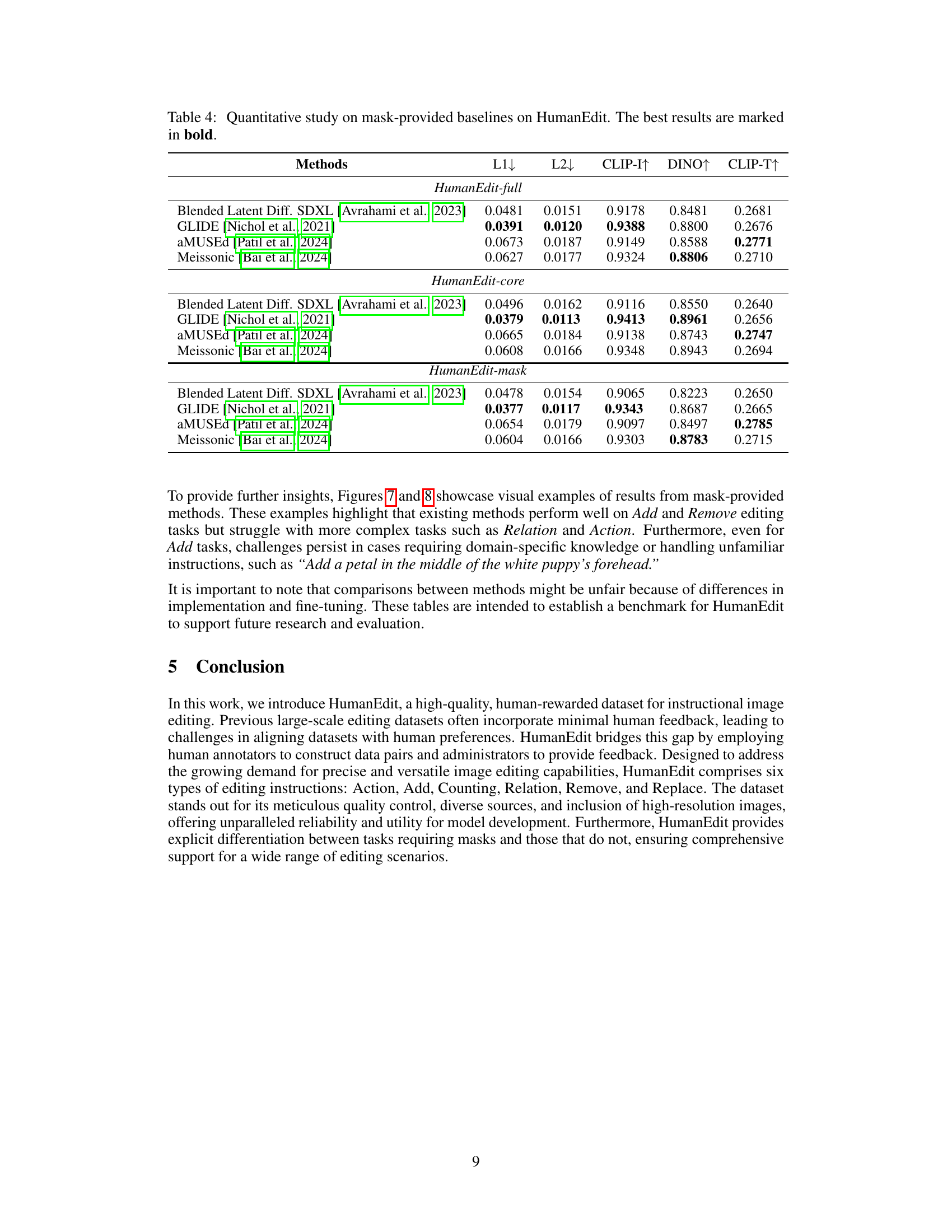

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different baselines on the HumanEdit dataset. The baselines are models used for image editing, and they are evaluated using mask-provided settings, meaning that the models are given both the image to edit and a mask indicating the region of interest. The evaluation metrics used are L1, L2, CLIP-I, DINO, and CLIP-T, which measure various aspects of the quality and consistency between the generated edited images and the ground truth (actual) edited images. The best performing model for each metric is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 4: Quantitative study on mask-provided baselines on HumanEdit. The best results are marked in bold.

| Methods | L1↓ | L2↓ | CLIP-I↑ | DINO↑ | CLIP-T↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HumanEdit-Add | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1152 | 0.0329 | 0.8135 | 0.6230 | 0.2764 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.0934 | 0.0274 | 0.8770 | 0.7391 | 0.2806 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.0885 | 0.0234 | 0.8863 | 0.7811 | 0.2706 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.0580 | 0.0167 | 0.9102 | 0.8562 | 0.2745 |

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0344 | 0.0073 | 0.9285 | 0.8856 | 0.2665 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0315 | 0.0078 | 0.9410 | 0.8995 | 0.2600 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0581 | 0.0130 | 0.9148 | 0.8672 | 0.2695 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0544 | 0.0129 | 0.9303 | 0.8787 | 0.2669 |

| HumanEdit-Action | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1324 | 0.0398 | 0.7514 | 0.5789 | 0.2617 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.0982 | 0.0383 | 0.8788 | 0.7909 | 0.2658 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.0972 | 0.0280 | 0.8592 | 0.7613 | 0.2640 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.0723 | 0.0245 | 0.9028 | 0.8357 | 0.2668 |

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0416 | 0.0109 | 0.9391 | 0.9015 | 0.2712 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0384 | 0.0114 | 0.9487 | 0.9018 | 0.2683 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0629 | 0.0156 | 0.9230 | 0.8919 | 0.2732 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0577 | 0.0145 | 0.9430 | 0.9126 | 0.2677 |

| HumanEdit-Counting | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1628 | 0.0586 | 0.8124 | 0.5850 | 0.2716 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.1380 | 0.0641 | 0.8726 | 0.6971 | 0.2716 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.1211 | 0.0442 | 0.8826 | 0.7431 | 0.2705 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.1058 | 0.0434 | 0.8677 | 0.7103 | 0.2707 |

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0527 | 0.0180 | 0.9334 | 0.8892 | 0.2766 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0392 | 0.0127 | 0.9523 | 0.9104 | 0.2772 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0699 | 0.0213 | 0.9270 | 0.8816 | 0.2814 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0674 | 0.0217 | 0.9394 | 0.8967 | 0.2750 |

| HumanEdit-Remove | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1624 | 0.0504 | 0.7240 | 0.4188 | 0.2325 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.1259 | 0.0572 | 0.8677 | 0.7235 | 0.2525 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.1179 | 0.0375 | 0.8362 | 0.6562 | 0.2474 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.0690 | 0.0232 | 0.8985 | 0.8249 | 0.2572 |

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0451 | 0.0133 | 0.9055 | 0.8322 | 0.2608 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0313 | 0.0072 | 0.9493 | 0.9119 | 0.2661 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0621 | 0.0156 | 0.9148 | 0.8702 | 0.2715 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0557 | 0.0132 | 0.9367 | 0.9048 | 0.2673 |

| HumanEdit-Relation | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1741 | 0.0647 | 0.8069 | 0.5851 | 0.2828 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.1420 | 0.0656 | 0.8762 | 0.7061 | 0.2768 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.1298 | 0.0460 | 0.8689 | 0.7005 | 0.2793 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.0884 | 0.0334 | 0.8985 | 0.7865 | 0.2823 |

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0628 | 0.0213 | 0.9190 | 0.8174 | 0.2832 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0553 | 0.0192 | 0.9136 | 0.7983 | 0.2755 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0809 | 0.0267 | 0.9076 | 0.8095 | 0.2862 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0825 | 0.0283 | 0.9171 | 0.8142 | 0.2768 |

| HumanEdit-Replace | |||||

| InstructPix2Pix (Brooks et al., 2023) | 0.1910 | 0.0770 | 0.7887 | 0.5692 | 0.2697 |

| MGIE (Fu et al., 2023) | 0.1391 | 0.0620 | 0.8603 | 0.6946 | 0.2698 |

| HIVE SD1.5 (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 0.1265 | 0.0443 | 0.8582 | 0.7087 | 0.2726 |

| MagicBrush (Zhang et al., 2024a) | 0.0984 | 0.0409 | 0.8757 | 0.7513 | 0.2716 |

| Blended Latent Diff. SDXL (Avrahami et al., 2023) | 0.0567 | 0.0206 | 0.9095 | 0.8096 | 0.2683 |

| GLIDE (Nichol et al., 2021) | 0.0495 | 0.0188 | 0.9194 | 0.8247 | 0.2663 |

| aMUSEd (Patil et al., 2024) | 0.0761 | 0.0237 | 0.9072 | 0.8259 | 0.2861 |

| Meissonic (Bai et al., 2024) | 0.0710 | 0.0227 | 0.9239 | 0.8462 | 0.2762 |

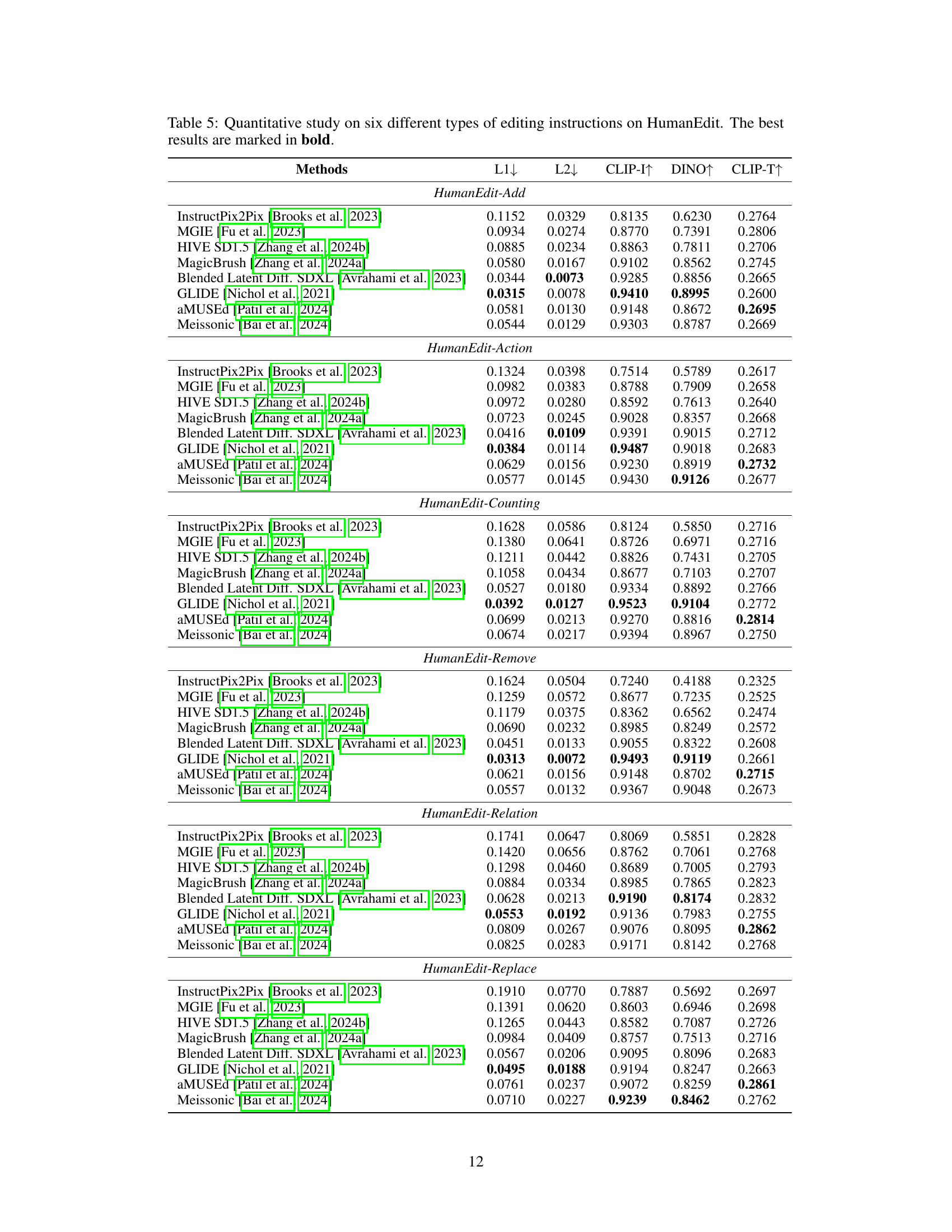

🔼 Table 5 presents a quantitative analysis of six distinct image editing instruction types within the HumanEdit dataset. The table compares the performance of various baselines (InstructPix2Pix, MGIE, HIVE SD1.5, MagicBrush, Blended Latent Diffusion SDXL, GLIDE, aMUSEd, and Meissonic) across these instructions. Evaluation metrics include L1 and L2 distance (measuring pixel-level differences), CLIP-I and DINO scores (assessing image quality), and CLIP-T scores (evaluating text-image alignment). The best-performing method for each metric and instruction type is highlighted in bold, enabling a nuanced comparison of model capabilities across various editing tasks.

read the caption

Table 5: Quantitative study on six different types of editing instructions on HumanEdit. The best results are marked in bold.

Full paper#