↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current contrastively-trained Vision-Language Models (VLMs) excel at image-text retrieval but lack robust language understanding. While Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) offer superior language capabilities, their autoregressive nature limits their effectiveness in discriminative tasks. This creates a need for models that combine the best of both approaches.

This paper introduces VladVA, a novel method that addresses this limitation. VladVA employs a carefully designed training framework that combines contrastive and next-token prediction losses, enabling the fine-tuning of LVLMs for discriminative tasks. This approach results in significant improvements over existing state-of-the-art models on various benchmarks, demonstrating the effectiveness of combining generative and discriminative training strategies for enhanced vision-language understanding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between generative and discriminative vision-language models, offering a novel approach to enhance discriminative capabilities. It addresses limitations of existing methods by leveraging the strengths of Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) while achieving state-of-the-art results. This opens new avenues for research in efficient fine-tuning techniques and parameter-efficient adaptation strategies.

Visual Insights#

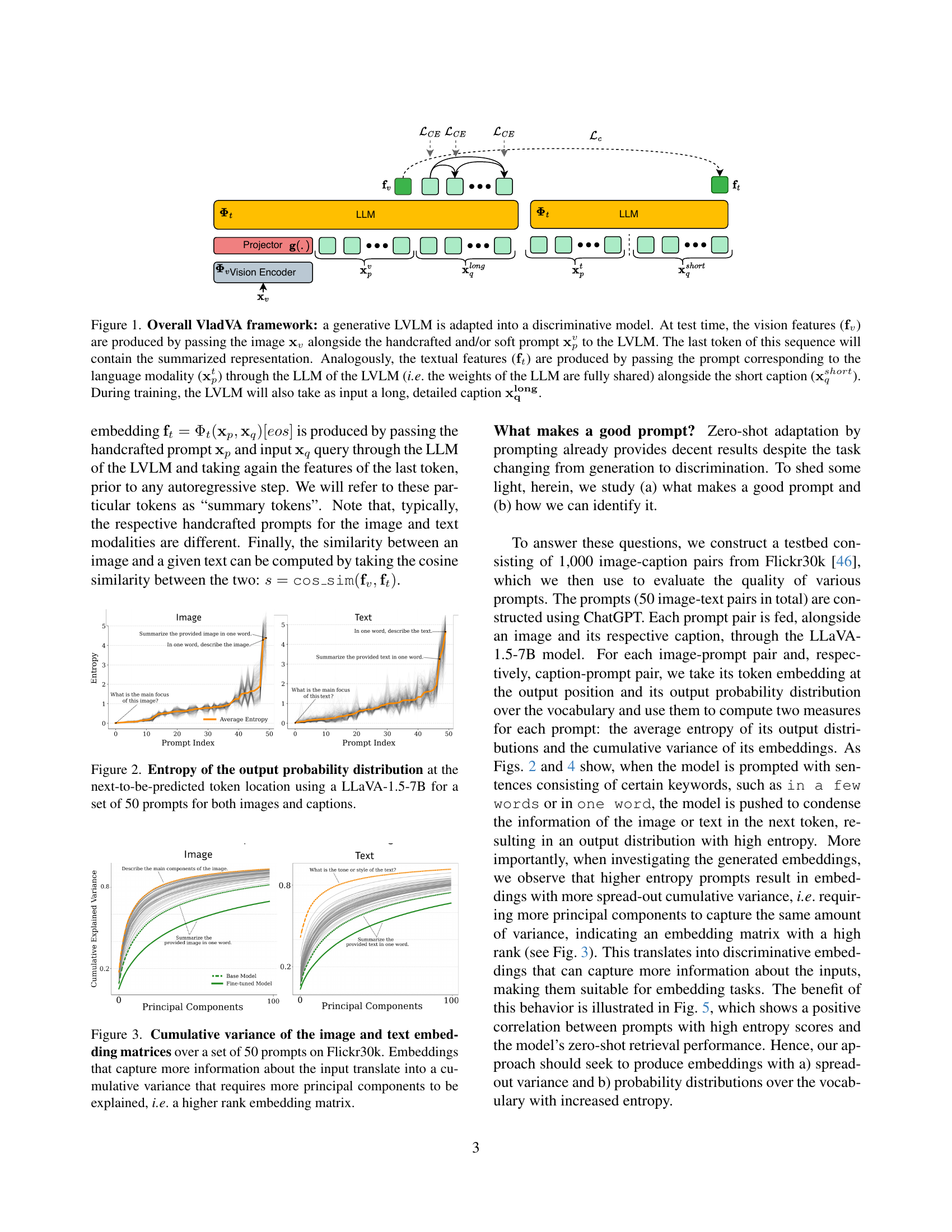

🔼 The VladVA framework adapts a generative Large Vision-Language Model (LVLM) for discriminative tasks. At test time, image features are generated by passing an image and a prompt (handcrafted or soft) through the LVLM; the final token represents a summarized image embedding. Similarly, text features are created by processing a text prompt and short caption through the LVLM’s Language Model (LLM). During training, a longer, detailed caption is also used.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overall VladVA framework: a generative LVLM is adapted into a discriminative model. At test time, the vision features (𝐟vsubscript𝐟𝑣\mathbf{f}_{v}bold_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_v end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) are produced by passing the image 𝐱vsubscript𝐱𝑣\mathbf{x}_{v}bold_x start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_v end_POSTSUBSCRIPT alongside the handcrafted and/or soft prompt 𝐱pvsubscriptsuperscript𝐱𝑣𝑝\mathbf{x}^{v}_{p}bold_x start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_v end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_p end_POSTSUBSCRIPT to the LVLM. The last token of this sequence will contain the summarized representation. Analogously, the textual features (𝐟tsubscript𝐟𝑡\mathbf{f}_{t}bold_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) are produced by passing the prompt corresponding to the language modality (𝐱ptsuperscriptsubscript𝐱𝑝𝑡\mathbf{x}_{p}^{t}bold_x start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_p end_POSTSUBSCRIPT start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_t end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT) through the LLM of the LVLM (i.e. the weights of the LLM are fully shared) alongside the short caption (𝐱qshortsuperscriptsubscript𝐱𝑞𝑠ℎ𝑜𝑟𝑡\mathbf{x}_{q}^{short}bold_x start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_q end_POSTSUBSCRIPT start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_s italic_h italic_o italic_r italic_t end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT). During training, the LVLM will also take as input a long, detailed caption 𝐱𝐪𝐥𝐨𝐧𝐠superscriptsubscript𝐱𝐪𝐥𝐨𝐧𝐠\mathbf{x_{q}^{long}}bold_x start_POSTSUBSCRIPT bold_q end_POSTSUBSCRIPT start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT bold_long end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT.

| Method | Flickr30K R@1 | Flickr30K R@10 | COCO R@1 | COCO R@10 | nocaps R@1 | nocaps R@10 | Flickr30K R@1 | Flickr30K R@10 | COCO R@1 | COCO R@10 | nocaps R@1 | nocaps R@10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP (ViT-B) [36] | 58.8 | 89.8 | 30.5 | 66.8 | 46.8 | 85.1 | 77.8 | 98.2 | 51.0 | 83.5 | 67.3 | 95.6 |

| CLIP (ViT-L) [36] | 67.3 | 93.3 | 37.0 | 71.5 | 48.6 | 85.7 | 87.2 | 99.4 | 58.1 | 87.8 | 70.0 | 96.2 |

| BLIP (ViT-L) [28] | 70.0 | 95.2 | 48.4 | 83.2 | 62.3 | 93.4 | 75.5 | 97.7 | 63.5 | 92.5 | 72.1 | 97.7 |

| BLIP2 (ViT-L) [29] | 74.5 | 97.2 | 50.0 | 86.1 | 63.0 | 93.8 | 86.1 | 99.4 | 63.0 | 93.1 | 74.4 | 98.3 |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-G/14) [37] | 77.8 | 96.9 | 48.8 | 81.5 | 63.7 | 93.2 | 91.5 | 99.6 | 66.3 | 91.8 | 81.0 | 98.7 |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-BigG/14) [37] | 79.5 | 97.1 | 51.3 | 83.0 | 65.1 | 93.5 | 92.9 | 97.1 | 67.3 | 92.6 | 82.3 | 98.8 |

| EVA-02-CLIP (ViT-E/14+) [38] | 78.8 | 96.8 | 51.1 | 82.7 | 64.5 | 92.9 | 93.9 | 99.8 | 68.8 | 92.8 | 83.0 | 98.9 |

| EVA-CLIP (8B) [39] | 80.3 | 97.2 | 52.0 | 82.9 | 65.3 | 93.2 | 94.5 | 99.7 | 70.1 | 93.1 | 83.5 | 98.6 |

| EVA-CLIP (18B) [39] | 83.3 | 97.9 | 55.6 | 85.2 | 69.3 | 94.8 | 95.3 | 99.8 | 72.8 | 94.2 | 85.6 | 99.2 |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 59.6 | 89.3 | 34.4 | 69.6 | 46.9 | 83.3 | 65.6 | 92.3 | 35.6 | 70.5 | 52.1 | 88.1 |

| E5-V (LLaVA-Next-8B) [23] | 79.5 | 97.6 | 52.0 | 84.7 | 65.9 | 94.3 | 88.2 | 99.4 | 62.0 | 89.7 | 74.9 | 98.3 |

| E5-V (LLaVA-1.5-7B) [23] | 76.7 | 96.9 | 48.2 | 82.1 | 62.0 | 93.0 | 86.6 | 99.0 | 57.4 | 88.4 | 71.9 | 97.0 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 85.0 | 98.5 | 59.0 | 88.6 | 72.3 | 96.5 | 94.3 | 99.9 | 72.9 | 94.4 | 85.7 | 99.5 |

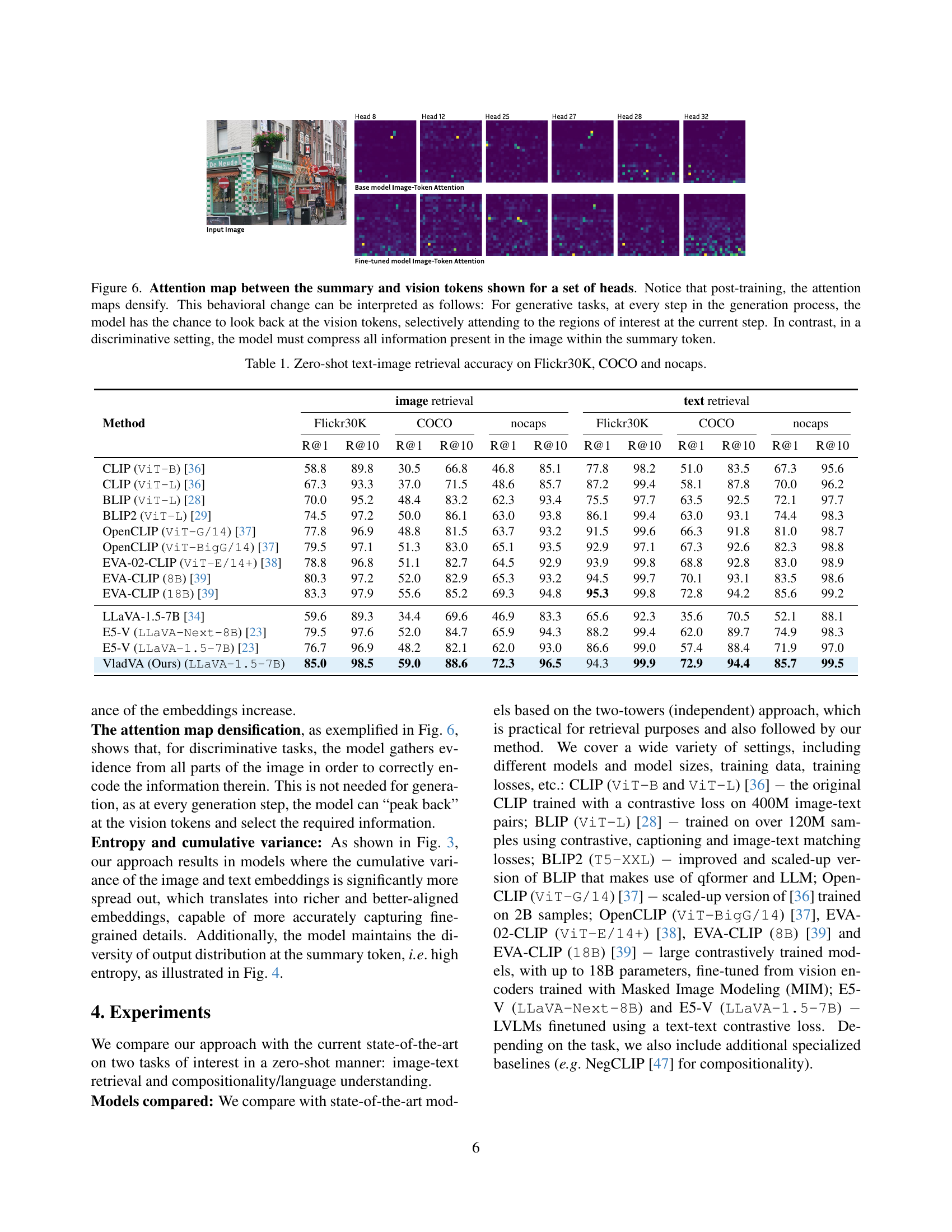

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot performance of different vision-language models on three image-text retrieval benchmarks: Flickr30K, COCO, and nocaps. Zero-shot indicates that the models were evaluated without any additional fine-tuning specific to these datasets. The results are reported as Recall@1 and Recall@10, which represent the percentage of times the correct image/text was among the top 1 and top 10 retrieval results, respectively. The table allows comparison of various models’ capabilities in image-to-text and text-to-image retrieval tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Zero-shot text-image retrieval accuracy on Flickr30K, COCO and nocaps.

In-depth insights#

LVLM Fine-tuning#

The concept of “LVLM Fine-tuning” centers on adapting large vision-language models (LVLMs) for enhanced performance on specific discriminative tasks. LVLMs, unlike contrastively trained models like CLIP, typically employ an autoregressive approach which makes them less suitable for direct image-text discrimination. Fine-tuning LVLMs involves modifying their parameters to improve their accuracy on tasks like image-text retrieval, where the goal is to identify semantically similar image-text pairs. This contrasts with the generative tasks LVLMs are often used for. A key challenge addressed is the need for methods that can effectively convert a generative LVLM architecture into a strong discriminative model. Effective fine-tuning strategies involve careful loss function design, often integrating contrastive losses for similarity assessment alongside next-token prediction losses which aid in compositional understanding. Furthermore, parameter-efficient techniques such as soft prompting and LoRA adapters are crucial for controlling computational cost and mitigating potential overfitting. Success in LVLM fine-tuning translates to significant improvements in discriminative tasks, and importantly, demonstrates the ability to harness the compositional strengths of LVLMs, which are typically associated with generative tasks, for improved performance in discriminative settings. This opens new possibilities for leveraging the reasoning capabilities of large language models within the context of visual data analysis and image-text understanding.

VladVA Framework#

The VladVA framework presents a novel approach to fine-tuning Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) for discriminative tasks. It cleverly bridges the gap between the contrastive learning paradigm of CLIP-like models and the generative capabilities of LVLMs. Instead of directly applying contrastive loss, which often proves detrimental for LVLMs, VladVA employs a hybrid training strategy incorporating both contrastive and next-token prediction losses. This dual-loss approach allows the model to learn from image-text pairs of variable length and granularity, fostering strong discriminative capabilities along with enhanced compositional understanding. The framework’s parameter-efficient adaptation method, leveraging soft prompting and LoRA adapters, enables efficient fine-tuning without the computational burden of full model training. This adaptive technique is crucial for scalability. VladVA’s design incorporates careful consideration of prompting strategies, selecting prompts that maximize both the entropy and variance of the output embeddings, ensuring the generated representations capture comprehensive information, improving discrimination and retrieval performance. The ablation studies further confirm the significance of each component in the VladVA architecture, highlighting its meticulous design and thorough evaluation. In essence, VladVA represents a significant step toward unlocking the full potential of LVLMs for discriminative tasks.

Contrastive Loss#

Contrastive loss, a cornerstone of many vision-language models, aims to learn embeddings that pull similar image-text pairs closer together while pushing dissimilar pairs further apart in a shared semantic space. The effectiveness hinges on the quality of the positive and negative samples used during training. High-quality positive pairs (similar images and texts) are crucial for guiding the model towards meaningful representations. Conversely, the selection of negative samples directly impacts the model’s ability to distinguish between semantically different pairs, with poorly chosen negatives potentially hindering performance. The choice of distance metric, often cosine similarity, also influences the results, affecting the model’s sensitivity to subtle differences or strong similarities in the data. Additionally, the balance between the contrastive loss and other potential loss functions, such as next-token prediction losses, significantly affects the overall model’s performance and ability to handle nuanced language understanding. While contrastive loss has proven effective, its inherent limitations, particularly concerning compositional understanding and bag-of-words effects, have driven exploration of more sophisticated training strategies, including hybrid approaches combining contrastive learning with other techniques.

Parameter Efficiency#

The concept of parameter efficiency is crucial for adapting large vision-language models (LVLMs) for discriminative tasks. Direct fine-tuning of LVLMs is computationally expensive, especially when aiming for large batch sizes necessary for contrastive learning. Therefore, the authors explore and adopt a parameter-efficient adaptation method combining soft prompting and LoRA adapters. Soft prompting provides a computationally efficient way to adapt the model to specific tasks by introducing learnable vectors into the input sequence. LoRA adapters further enhance efficiency by only training a small set of low-rank matrices, avoiding the need for training the entire model. This combination significantly reduces the computational cost and memory requirements while achieving strong performance improvements. The ablation studies demonstrate the positive impact of both components, highlighting their importance for achieving significant gains over state-of-the-art CLIP-like models and showcasing the success of this parameter-efficient approach in unlocking the full potential of LVLMs for discriminative vision-language tasks. The effectiveness of this strategy is crucial for deploying these sophisticated models in resource-constrained environments.

Compositionality#

The research paper investigates the crucial aspect of compositionality in Vision-Language Models (VLMs). Compositionality, the ability of a model to understand and generate meaning from the combination of individual elements, is a significant challenge for VLMs. The authors highlight that while contrastively-trained models like CLIP excel at zero-shot image retrieval, they often fall short when it comes to understanding complex relationships between visual and textual elements. This limitation is described as “bag-of-words” behavior. The paper proposes a novel training framework for Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) to improve compositionality. By incorporating both contrastive and next-token prediction losses, the authors aim to address the shortcomings of previous approaches. The results demonstrate that this method, VladVA, achieves significant improvements in compositionality benchmarks compared to state-of-the-art models, showcasing its effectiveness in addressing a critical limitation of existing VLMs and paving the way for more robust and nuanced vision-language understanding.

More visual insights#

More on figures

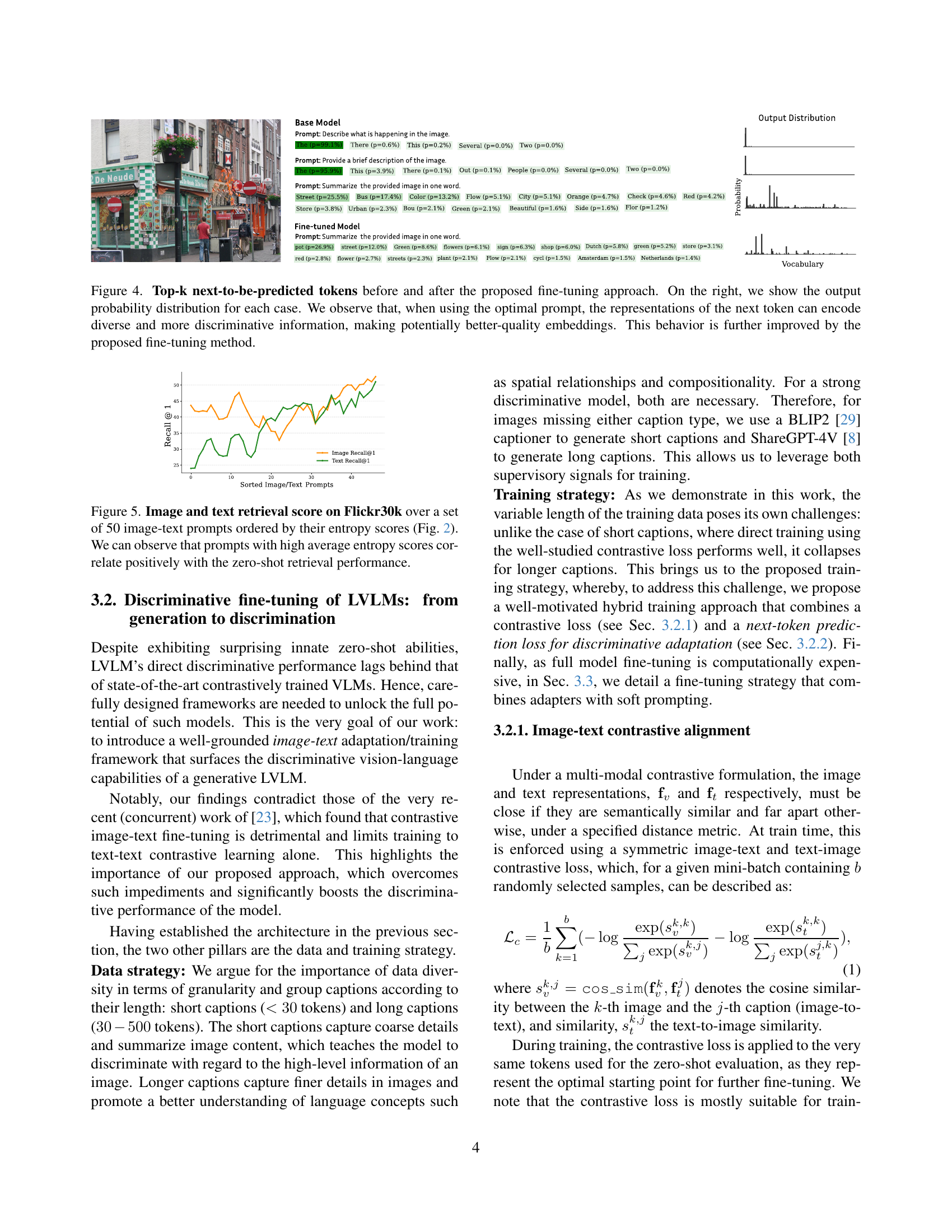

🔼 This figure visualizes the entropy of the probability distribution for the next predicted token. It uses the LLaVA-1.5-7B model and evaluates 50 different prompts for both image and text inputs. The x-axis represents the prompt index, and the y-axis represents the entropy. Separate lines show entropy values for image prompts and text prompts. The goal is to show the effect of different prompt types on the model’s output uncertainty and information content. Higher entropy indicates greater uncertainty.

read the caption

Figure 2: Entropy of the output probability distribution at the next-to-be-predicted token location using a LLaVA-1.5-7B for a set of 50 prompts for both images and captions.

🔼 Figure 3 visualizes the cumulative variance of embedding matrices generated from 50 different prompts applied to image and text data from the Flickr30k dataset. The x-axis represents the number of principal components used in the principal component analysis (PCA), while the y-axis shows the cumulative variance explained. The key insight is that richer embeddings, carrying more information about the input image or text, exhibit higher cumulative variance. This means a larger number of principal components are needed to capture the significant portion of the variance in those richer embeddings. In simpler terms, a higher cumulative variance signifies a higher-rank embedding matrix, indicating greater complexity and information density within the embedding.

read the caption

Figure 3: Cumulative variance of the image and text embedding matrices over a set of 50 prompts on Flickr30k. Embeddings that capture more information about the input translate into a cumulative variance that requires more principal components to be explained, i.e. a higher rank embedding matrix.

🔼 This figure shows the top-k predicted tokens (words) before and after fine-tuning a vision-language model. The left side displays the predicted words and their probabilities for various prompts. The right side shows the probability distribution of these predictions. The results demonstrate that using an optimized prompt and the proposed fine-tuning method leads to more diverse and discriminative information encoded in the predicted tokens. This improved representation, in turn, yields potentially higher-quality embeddings for image and text data.

read the caption

Figure 4: Top-k next-to-be-predicted tokens before and after the proposed fine-tuning approach. On the right, we show the output probability distribution for each case. We observe that, when using the optimal prompt, the representations of the next token can encode diverse and more discriminative information, making potentially better-quality embeddings. This behavior is further improved by the proposed fine-tuning method.

🔼 This figure displays the relationship between prompt entropy and zero-shot retrieval performance on the Flickr30k dataset. Fifty image-text prompt pairs were ranked by their average entropy (as calculated and shown in Figure 2). The graph plots recall@1 for both image and text retrieval against the sorted prompt indices. The results show a positive correlation: prompts with higher entropy tend to yield better zero-shot retrieval performance.

read the caption

Figure 5: Image and text retrieval score on Flickr30k over a set of 50 image-text prompts ordered by their entropy scores (Fig. 2). We can observe that prompts with high average entropy scores correlate positively with the zero-shot retrieval performance.

🔼 Figure 6 visualizes the attention maps between the summary token and vision tokens across various attention heads. Before fine-tuning (pre-training), the attention is sparsely distributed across the image, reflecting the model’s generative approach where it focuses on specific regions at each step of the generation process. After fine-tuning, the attention maps become denser and more uniformly distributed across the image. This shift indicates the model’s transition to a discriminative behavior where it needs to comprehensively integrate all image information into a single, compact summary token.

read the caption

Figure 6: Attention map between the summary and vision tokens shown for a set of heads. Notice that post-training, the attention maps densify. This behavioral change can be interpreted as follows: For generative tasks, at every step in the generation process, the model has the chance to look back at the vision tokens, selectively attending to the regions of interest at the current step. In contrast, in a discriminative setting, the model must compress all information present in the image within the summary token.

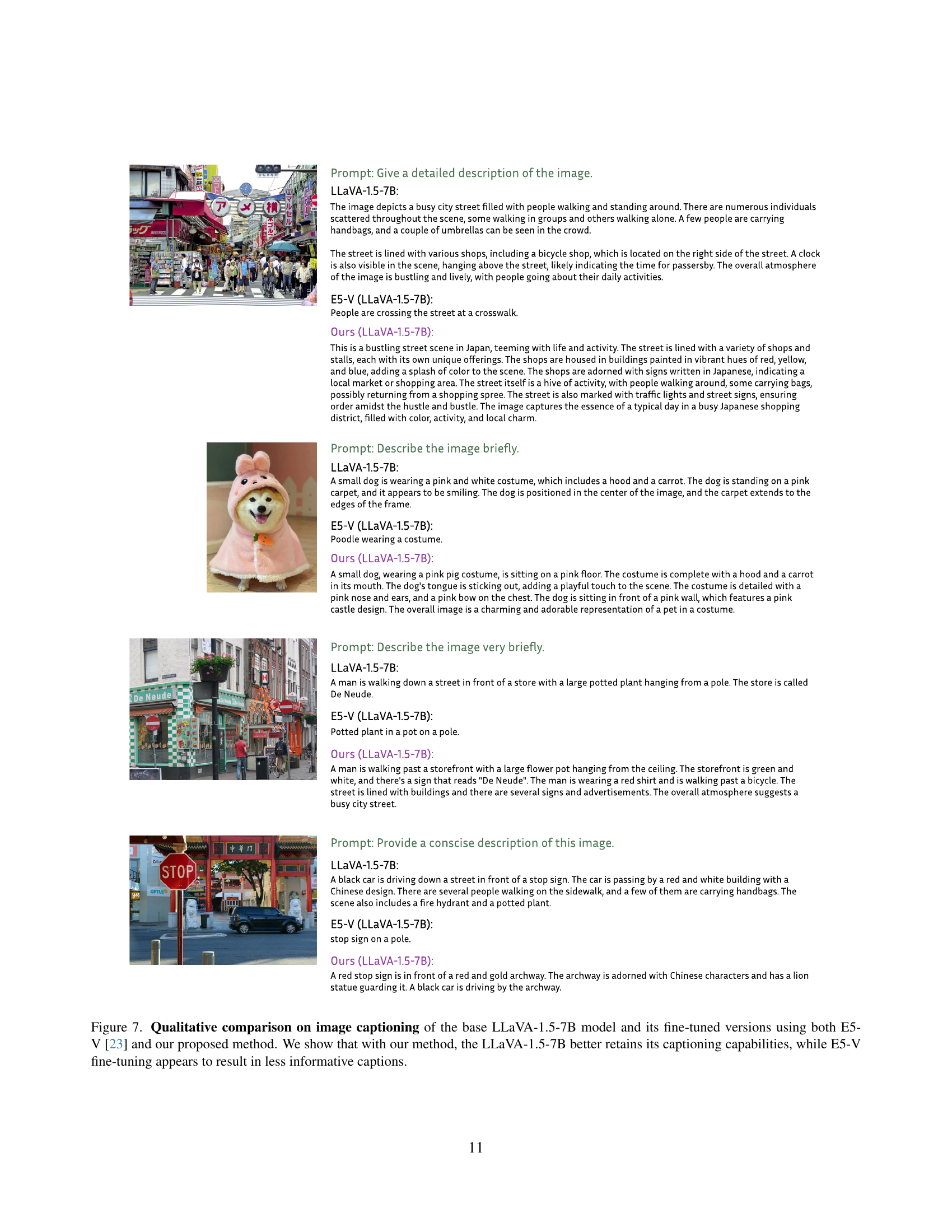

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of image captioning results generated by three different models: the original LLaVA-1.5-7B model and the same model after fine-tuning using two different methods – E5-V and the authors’ proposed method. The comparison highlights how well each method preserves the original model’s captioning capabilities while enhancing discriminative image-text capabilities. The figure shows that the proposed method better retains the LLaVA model’s ability to produce detailed and informative captions, unlike the E5-V method which generates less descriptive and shorter captions.

read the caption

Figure 7: Qualitative comparison on image captioning of the base LLaVA-1.5-7B model and its fine-tuned versions using both E5-V [23] and our proposed method. We show that with our method, the LLaVA-1.5-7B better retains its captioning capabilities, while E5-V fine-tuning appears to result in less informative captions.

More on tables

| Method | Params (B) | Replace Object | Replace Attribute | Replace Relation | Replace Object | Swap Attribute | Swap Object | Add Attribute | Add Object |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | – | 100 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 99 | |

| CLIP (ViT-B) [36] | 0.15 | 90.9 | 80.1 | 69.2 | 61.4 | 64.0 | 77.2 | 68.8 | |

| CLIP (ViT-L) [36] | 0.43 | 94.1 | 79.2 | 65.2 | 60.2 | 62.3 | 78.3 | 71.5 | |

| BLIP (ViT-L) [28] | 0.23 | 96.5 | 81.7 | 69.1 | 66.6 | 76.8 | 92.0 | 85.1 | |

| BLIP2 (ViT-L) [29] | 1.17 | 97.6 | 81.7 | 77.8 | 62.1 | 65.5 | 92.4 | 87.4 | |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-G/14) [37] | 1.37 | 95.8 | 85.0 | 72.4 | 63.0 | 71.2 | 91.5 | 82.1 | |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-BigG/14) [37] | 2.54 | 96.6 | 87.9 | 74.9 | 62.5 | 75.2 | 92.2 | 84.5 | |

| EVA-02-CLIP (ViT-E/14+) [38] | 5.04 | 97.1 | 88.5 | 74.2 | 67.3 | 74.1 | 91.8 | 83.9 | |

| EVA-CLIP (8B) [39] | 8.22 | 96.4 | 86.6 | 74.8 | 66.1 | 74.6 | 91.3 | 82.0 | |

| EVA-CLIP (18B) [39] | 18.3 | 97.5 | 88.8 | 76.1 | 65.3 | 76.0 | 92.4 | 85.0 | |

| NegCLIP [47] | 0.15 | 92.7 | 85.9 | 76.5 | 75.2 | 75.4 | 88.8 | 82.8 | |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 7.06 | 88.0 | 81.6 | 76.1 | 60.9 | 58.8 | 67.0 | 62.4 | |

| E5-V (LLaVA-Next-8B) [23] | 8.36 | 96.7 | 89.5 | 85.3 | 75.0 | 70.1 | 89.2 | 83.5 | |

| E5-V (LLaVA-1.5-7B) [23] | 7.06 | 95.8 | 86.6 | 81.6 | 62.9 | 64.0 | 93.5 | 88.0 | |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 7.06 | 98.1 | 92.1 | 86.8 | 79.0 | 82.9 | 95.2 | 95.8 |

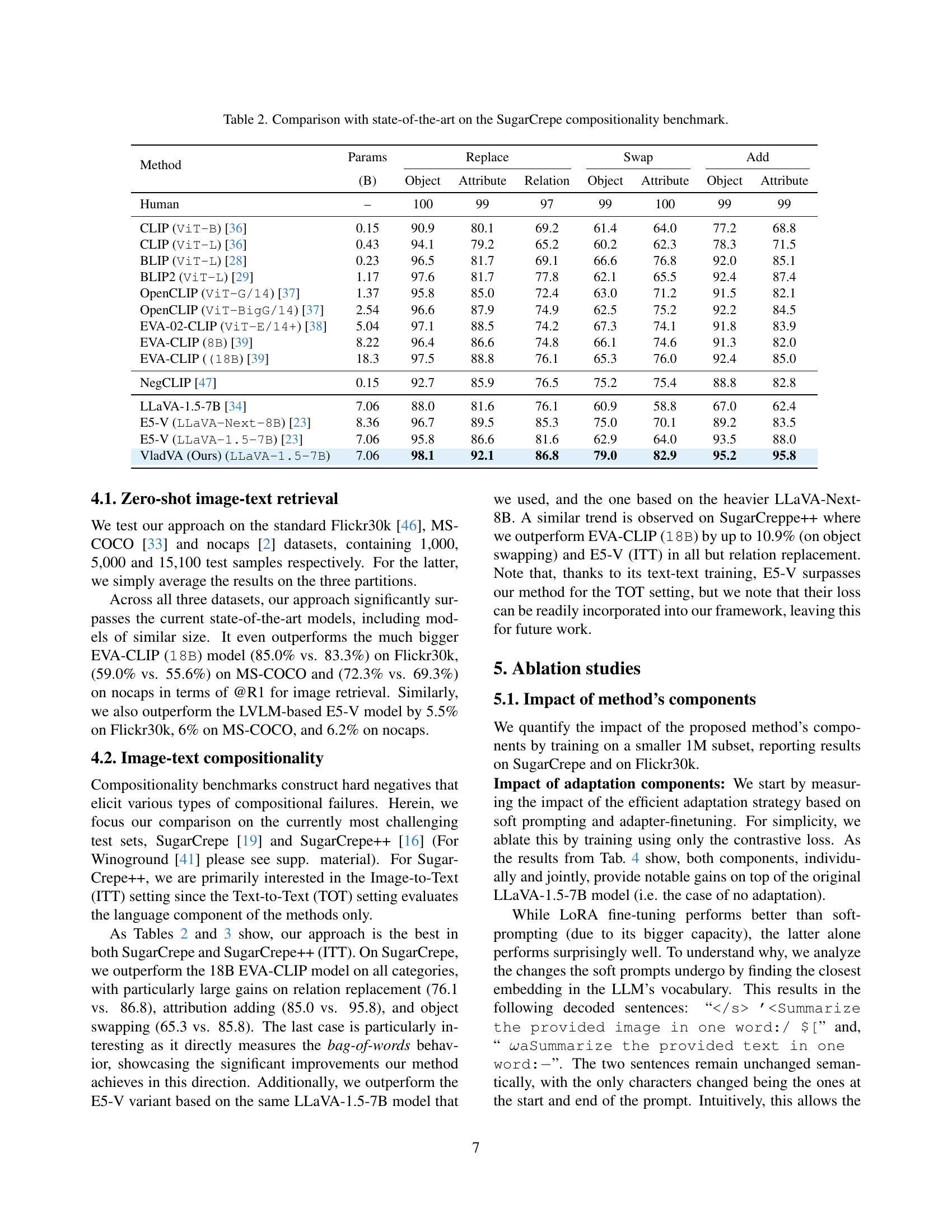

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of various state-of-the-art vision-language models on the SugarCrepe compositionality benchmark. The benchmark evaluates how well models understand the compositional nature of language and vision, by testing their ability to reason about relationships between objects and attributes in images. The table shows the number of parameters (in billions) for each model, as well as their performance across three specific compositionality tests: object replacement, attribute replacement, and relation replacement. Performance is expressed in terms of accuracy. The purpose is to show how well the proposed VladVA model performs relative to the existing leading models in the field.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison with state-of-the-art on the SugarCrepe compositionality benchmark.

| Method | Params | Swap Object | Swap Attribute | Replace Object | Replace Attribute | Replace Relation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (B) | ITT | TOT | ITT | TOT | ITT | TOT | ITT | TOT | ITT | TOT | |

| Human | – | 100.00 | 96.7 | 96.7 | 93.3 | 100.00 | 97.00 | 100.00 | 98.3 | 100.00 | 96.7 |

| CLIP (ViT-B) [36] | 0.15 | 45.2 | 19.7 | 45.2 | 33.0 | 86.8 | 83.7 | 65.6 | 59.1 | 56.3 | 38.62 |

| CLIP (ViT-L) [36] | 0.43 | 46.0 | 14.5 | 44.5 | 28.7 | 92.0 | 81.3 | 68.8 | 56.3 | 53.4 | 39.1 |

| BLIP (ViT-L) [28] | 0.23 | 46.8 | 29.8 | 60.1 | 52.5 | 92.6 | 89.1 | 71.7 | 75.0 | 56.8 | 57.7 |

| BLIP2 (ViT-L) [29] | 1.17 | 37.9 | 39.5 | 51.9 | 55.4 | 94.8 | 96.9 | 73.2 | 86.5 | 65.1 | 69.6 |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-G/14) [37] | 1.37 | 40.7 | 27.4 | 54.2 | 49.6 | 93.1 | 89.4 | 72.5 | 73.1 | 57.6 | 51.4 |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-BigG/14) [37] | 2.54 | 48.8 | 28.2 | 57.7 | 52.4 | 94.2 | 90.5 | 76.4 | 72.6 | 59.4 | 53.6 |

| EVA-02-CLIP (ViT-E/14+) [38] | 5.04 | 48.4 | 28.2 | 56.3 | 49.4 | 94.5 | 88.9 | 76.3 | 70.6 | 59.4 | 49.4 |

| EVA-CLIP (8B) [39] | 8.22 | 43.6 | 25.4 | 55.2 | 46.9 | 93.7 | 85.8 | 73.4 | 67.9 | 59.7 | 49.2 |

| EVA-CLIP (18B) [39] | 18.3 | 45.2 | 25.4 | 55.5 | 47.6 | 94.1 | 85.1 | 77.0 | 69.8 | 60.4 | 47.8 |

| NegCLIP [47] | 0.15 | 55.3 | 34.7 | 58.0 | 56.5 | 89.5 | 94.5 | 69.4 | 76.3 | 52.3 | 51.6 |

| CLIP-SVLC [14] | 0.15 | 43.0 | 18.9 | 48.4 | 34.6 | 80.9 | 91.6 | 57.0 | 66.9 | 47.3 | 51.3 |

| BLIP-SGVL [18] | 0.15 | 13.2 | – | 38.8 | – | 53.8 | – | 34.4 | – | 30.7 | – |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 7.06 | 23.8 | 30.7 | 28.0 | 29.5 | 58.1 | 63.0 | 46.8 | 58.1 | 52.3 | 63.4 |

| E5-V (LLaVA-Next-8B) [23] | 8.36 | 50.8 | 48.4 | 49.7 | 56.9 | 93.1 | 97.6 | 76.1 | 87.1 | 74.7 | 84.4 |

| E5-V (LLaVA-1.5-7B) [23] | 7.06 | 39.5 | 42.3 | 40.7 | 48.5 | 89.7 | 94.6 | 71.7 | 86.4 | 72.0 | 81.5 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 7.06 | 56.1 | 36.7 | 63.0 | 62.5 | 95.0 | 93.0 | 78.2 | 82.3 | 71.1 | 66.3 |

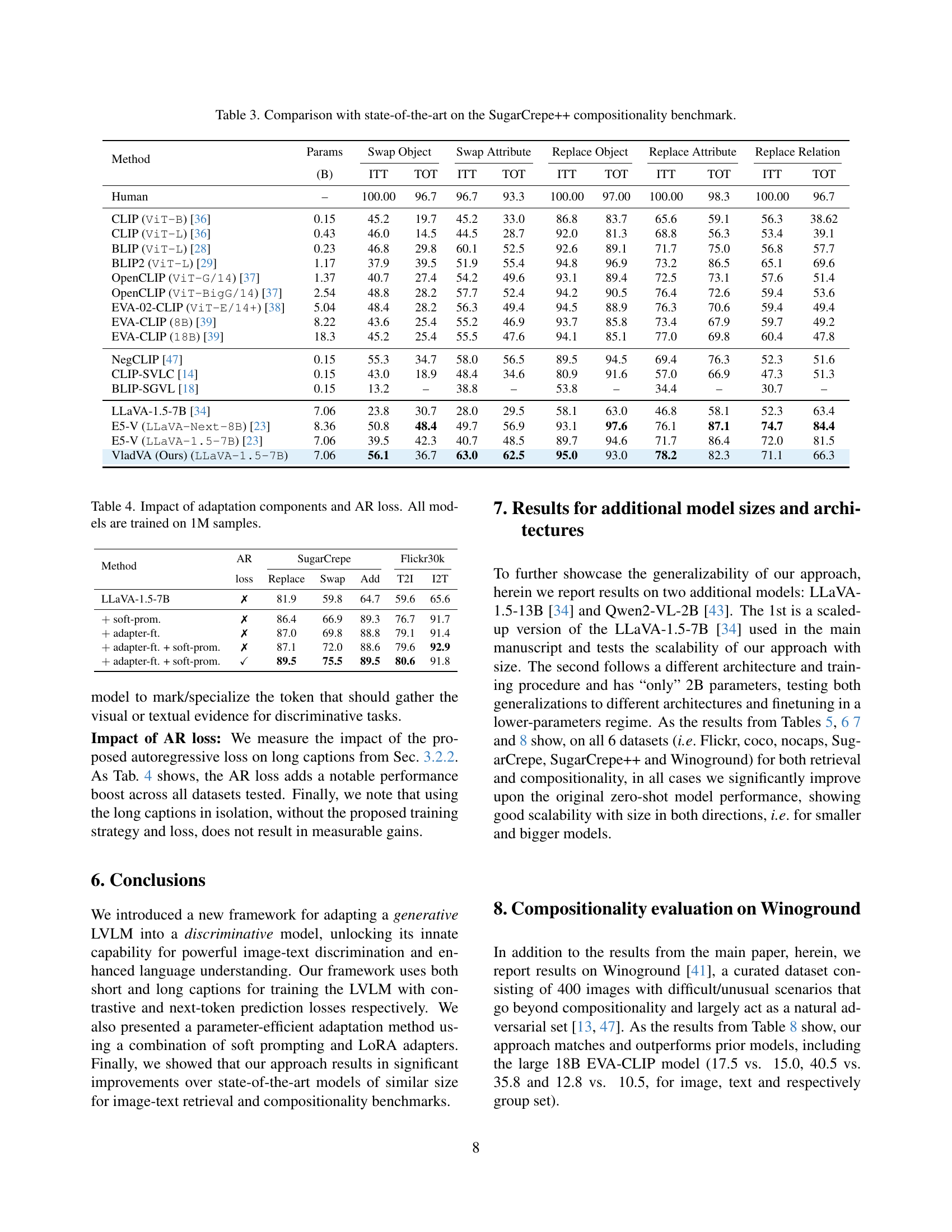

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various state-of-the-art models on the SugarCrepe++ benchmark, which assesses the compositionality of vision-language models. It shows the performance of different models across several sub-tasks, specifically those involving object and attribute replacement and swapping, and relation replacement. The results highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each model in handling different types of compositional challenges within image-text understanding.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison with state-of-the-art on the SugarCrepe++ compositionality benchmark.

| Method | AR | SugarCrepe loss | SugarCrepe Replace | SugarCrepe Swap | SugarCrepe Add | Flickr30k T2I | Flickr30k I2T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLaVA-1.5-7B | ✗ | 81.9 | 59.8 | 64.7 | 59.6 | 65.6 | |

| + soft-prom. | ✗ | 86.4 | 66.9 | 89.3 | 76.7 | 91.7 | |

| + adapter-ft. | ✗ | 87.0 | 69.8 | 88.8 | 79.1 | 91.4 | |

| + adapter-ft. + soft-prom. | ✗ | 87.1 | 72.0 | 88.6 | 79.6 | 92.9 | |

| + adapter-ft. + soft-prom. | ✓ | 89.5 | 75.5 | 89.5 | 80.6 | 91.8 |

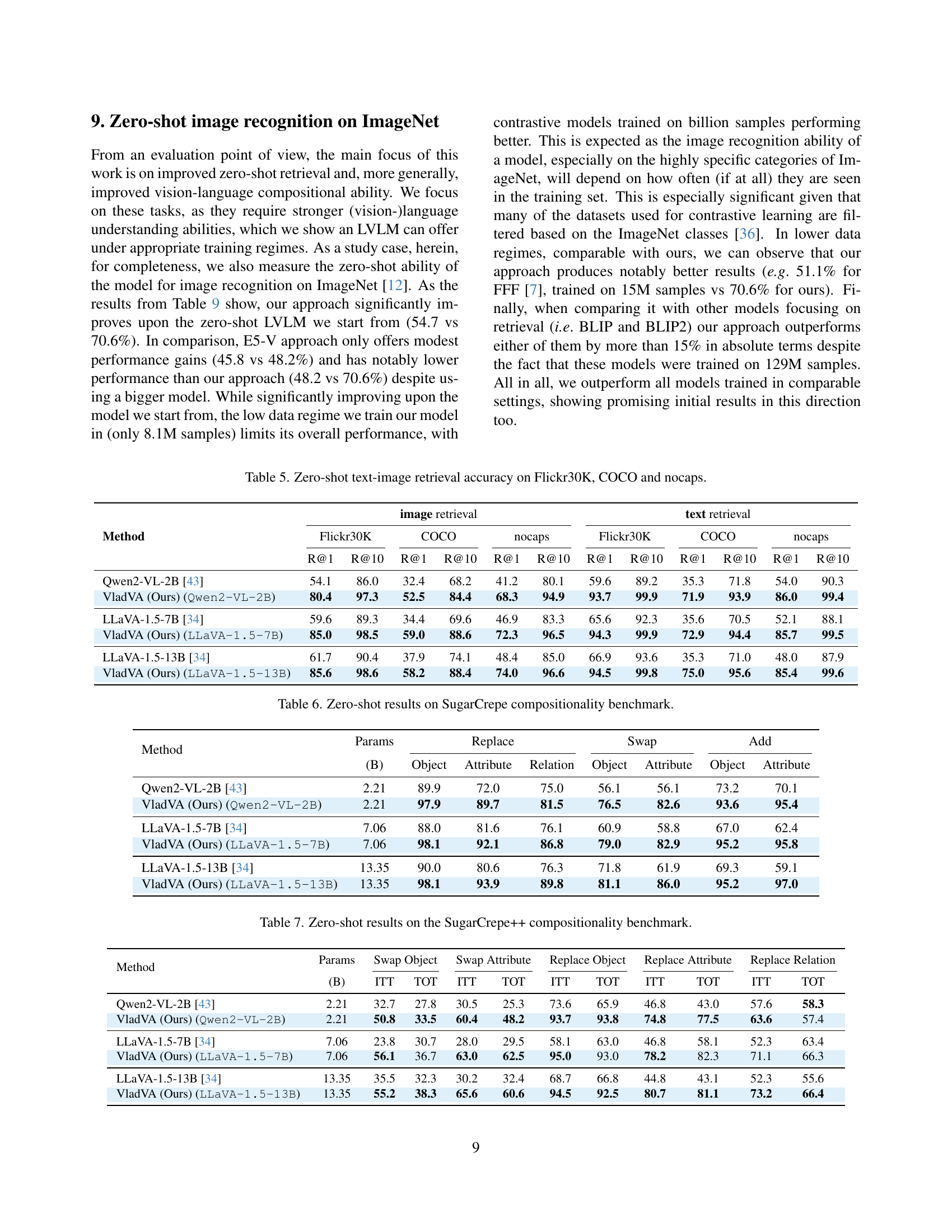

🔼 This table presents an ablation study analyzing the impact of different components in the VladVA model, trained on a smaller subset of 1 million samples. It shows the results for various configurations, such as using soft prompting, LoRA adapters, and/or the autoregressive (AR) loss, on two image-text retrieval benchmarks: SugarCrepe and Flickr30k. The purpose is to determine the contribution of each component and whether the autoregressive loss helps improve the model’s discriminative capabilities.

read the caption

Table 4: Impact of adaptation components and AR loss. All models are trained on 1M samples.

| Method | Flickr30K R@1 | Flickr30K R@10 | COCO R@1 | COCO R@10 | nocaps R@1 | nocaps R@10 | Flickr30K R@1 | Flickr30K R@10 | COCO R@1 | COCO R@10 | nocaps R@1 | nocaps R@10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| image retrieval | ||||||||||||

| text retrieval | ||||||||||||

| Qwen2-VL-2B [43] | 54.1 | 86.0 | 32.4 | 68.2 | 41.2 | 80.1 | 59.6 | 89.2 | 35.3 | 71.8 | 54.0 | 90.3 |

| VladVA (Ours) (Qwen2-VL-2B) | 80.4 | 97.3 | 52.5 | 84.4 | 68.3 | 94.9 | 93.7 | 99.9 | 71.9 | 93.9 | 86.0 | 99.4 |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 59.6 | 89.3 | 34.4 | 69.6 | 46.9 | 83.3 | 65.6 | 92.3 | 35.6 | 70.5 | 52.1 | 88.1 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 85.0 | 98.5 | 59.0 | 88.6 | 72.3 | 96.5 | 94.3 | 99.9 | 72.9 | 94.4 | 85.7 | 99.5 |

| LLaVA-1.5-13B [34] | 61.7 | 90.4 | 37.9 | 74.1 | 48.4 | 85.0 | 66.9 | 93.6 | 35.3 | 71.0 | 48.0 | 87.9 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-13B) | 85.6 | 98.6 | 58.2 | 88.4 | 74.0 | 96.6 | 94.5 | 99.8 | 75.0 | 95.6 | 85.4 | 99.6 |

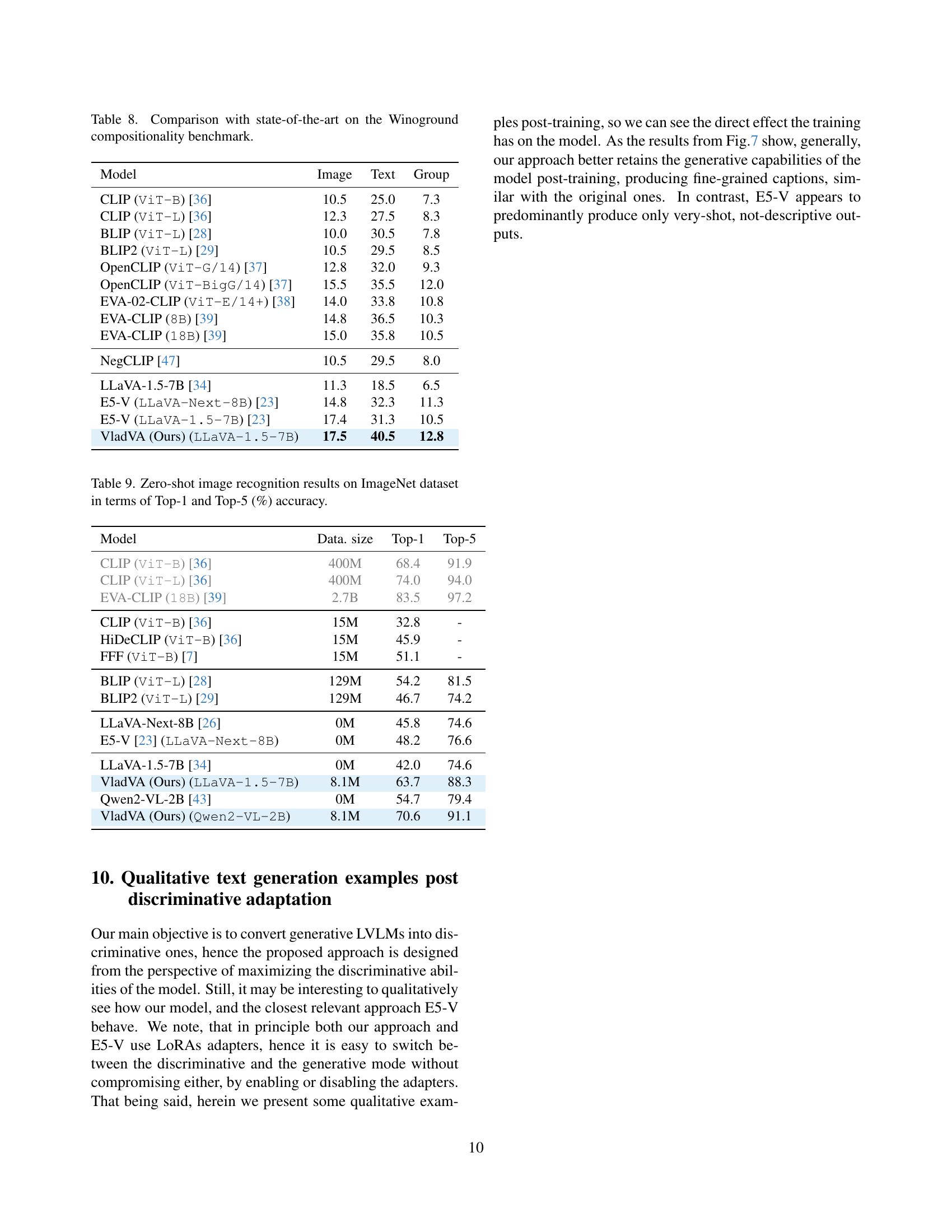

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot performance of various models on three benchmark datasets: Flickr30K, COCO, and nocaps. It shows the recall@1 and recall@10 scores for both image retrieval (given a text query, how accurately the model retrieves the correct image) and text retrieval (given an image, how accurately the model retrieves the correct text description). The results illustrate the relative effectiveness of different models in zero-shot image-text matching tasks.

read the caption

Table 5: Zero-shot text-image retrieval accuracy on Flickr30K, COCO and nocaps.

| Method | Params | Replace Object | Replace Attribute | Replace Relation | Swap Object | Swap Attribute | Add Object | Add Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen2-VL-2B [43] | 2.21 | 89.9 | 72.0 | 75.0 | 56.1 | 56.1 | 73.2 | 70.1 |

| VladVA (Ours) (Qwen2-VL-2B) | 2.21 | 97.9 | 89.7 | 81.5 | 76.5 | 82.6 | 93.6 | 95.4 |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 7.06 | 88.0 | 81.6 | 76.1 | 60.9 | 58.8 | 67.0 | 62.4 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 7.06 | 98.1 | 92.1 | 86.8 | 79.0 | 82.9 | 95.2 | 95.8 |

| LLaVA-1.5-13B [34] | 13.35 | 90.0 | 80.6 | 76.3 | 71.8 | 61.9 | 69.3 | 59.1 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-13B) | 13.35 | 98.1 | 93.9 | 89.8 | 81.1 | 86.0 | 95.2 | 97.0 |

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot performance of various vision-language models on the SugarCrepe compositionality benchmark. SugarCrepe tests the models’ ability to understand and generate captions correctly in scenarios with varying degrees of compositional complexity (e.g., replacing, swapping, or adding objects or attributes). The results are broken down by the type of compositionality challenge and measure the model’s accuracy for both image-to-text (ITT) and text-to-text (TOT) tasks, illustrating the relative strengths and weaknesses of different models in handling compositional language.

read the caption

Table 6: Zero-shot results on SugarCrepe compositionality benchmark.

| Method | Params | Swap Object | Swap Attribute | Replace Object | Replace Attribute | Replace Relation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen2-VL-2B [43] | 2.21 | 32.7 | 27.8 | 30.5 | 25.3 | 73.6 | 65.9 | 46.8 | 43.0 | 57.6 | 58.3 |

| VladVA (Ours) (Qwen2-VL-2B) | 2.21 | 50.8 | 33.5 | 60.4 | 48.2 | 93.7 | 93.8 | 74.8 | 77.5 | 63.6 | 57.4 |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 7.06 | 23.8 | 30.7 | 28.0 | 29.5 | 58.1 | 63.0 | 46.8 | 58.1 | 52.3 | 63.4 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 7.06 | 56.1 | 36.7 | 63.0 | 62.5 | 95.0 | 93.0 | 78.2 | 82.3 | 71.1 | 66.3 |

| LLaVA-1.5-13B [34] | 13.35 | 35.5 | 32.3 | 30.2 | 32.4 | 68.7 | 66.8 | 44.8 | 43.1 | 52.3 | 55.6 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-13B) | 13.35 | 55.2 | 38.3 | 65.6 | 60.6 | 94.5 | 92.5 | 80.7 | 81.1 | 73.2 | 66.4 |

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot performance of various vision-language models on the SugarCrepe++ benchmark. SugarCrepe++ is a challenging dataset designed to evaluate the compositionality capabilities of these models by testing their ability to correctly interpret images and text with various compositional manipulations, including object, attribute, and relation replacements and swaps. The results show the accuracy of each model across different compositionality tasks, enabling a detailed comparison of their performance in handling complex language and vision interactions.

read the caption

Table 7: Zero-shot results on the SugarCrepe++ compositionality benchmark.

| Model | Image | Text | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP (ViT-B) [36] | 10.5 | 25.0 | 7.3 |

| CLIP (ViT-L) [36] | 12.3 | 27.5 | 8.3 |

| BLIP (ViT-L) [28] | 10.0 | 30.5 | 7.8 |

| BLIP2 (ViT-L) [29] | 10.5 | 29.5 | 8.5 |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-G/14) [37] | 12.8 | 32.0 | 9.3 |

| OpenCLIP (ViT-BigG/14) [37] | 15.5 | 35.5 | 12.0 |

| EVA-02-CLIP (ViT-E/14+) [38] | 14.0 | 33.8 | 10.8 |

| EVA-CLIP (8B) [39] | 14.8 | 36.5 | 10.3 |

| EVA-CLIP (18B) [39] | 15.0 | 35.8 | 10.5 |

| NegCLIP [47] | 10.5 | 29.5 | 8.0 |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 11.3 | 18.5 | 6.5 |

| E5-V (LLaVA-Next-8B) [23] | 14.8 | 32.3 | 11.3 |

| E5-V (LLaVA-1.5-7B) [23] | 17.4 | 31.3 | 10.5 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 17.5 | 40.5 | 12.8 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of various state-of-the-art vision-language models on the Winoground benchmark. Winoground is a challenging dataset designed to evaluate the compositional abilities of these models, specifically focusing on how well they understand the relationship between objects, attributes, and relations in images. The table shows the results for each model’s performance on image, text, and a combined image and text evaluation, providing a comprehensive assessment of their ability to correctly interpret compositional aspects of visual scenes.

read the caption

Table 8: Comparison with state-of-the-art on the Winoground compositionality benchmark.

| Model | Data size | Top-1 | Top-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP (ViT-B) [36] | 400M | 68.4 | 91.9 |

| CLIP (ViT-L) [36] | 400M | 74.0 | 94.0 |

| EVA-CLIP (18B) [39] | 2.7B | 83.5 | 97.2 |

| CLIP (ViT-B) [36] | 15M | 32.8 | - |

| HiDeCLIP (ViT-B) [36] | 15M | 45.9 | - |

| FFF (ViT-B) [7] | 15M | 51.1 | - |

| BLIP (ViT-L) [28] | 129M | 54.2 | 81.5 |

| BLIP2 (ViT-L) [29] | 129M | 46.7 | 74.2 |

| LLaVA-Next-8B [26] | 0M | 45.8 | 74.6 |

| E5-V [23] (LLaVA-Next-8B) | 0M | 48.2 | 76.6 |

| LLaVA-1.5-7B [34] | 0M | 42.0 | 74.6 |

| VladVA (Ours) (LLaVA-1.5-7B) | 8.1M | 63.7 | 88.3 |

| Qwen2-VL-2B [43] | 0M | 54.7 | 79.4 |

| VladVA (Ours) (Qwen2-VL-2B) | 8.1M | 70.6 | 91.1 |

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot image recognition performance of various models on the ImageNet dataset. The results are evaluated using two metrics: Top-1 accuracy (the percentage of images correctly classified as the most likely class) and Top-5 accuracy (the percentage of images correctly classified among the five most likely classes). The table allows comparison of different models’ ability to generalize to unseen ImageNet images without any specific training on this dataset.

read the caption

Table 9: Zero-shot image recognition results on ImageNet dataset in terms of Top-1 and Top-5 (%) accuracy.

Full paper#