↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current image watermarking methods are vulnerable to forgery and removal, particularly with the rise of sophisticated deepfake technology. These methods often distort the image distribution, revealing information about the watermarking technique itself. This makes them susceptible to attacks that exploit this vulnerability. The existing methods are also computationally expensive and inefficient.

This research proposes a novel two-stage watermarking framework, called WIND. WIND embeds information in the initial noise of an image using a diffusion model, making it virtually indistinguishable from non-watermarked images. A two-stage detection approach, first identifying a group of noises and then searching within the group, significantly improves efficiency and robustness. The results demonstrate that WIND is highly resistant to various forgery and removal attacks, surpassing the performance of existing watermarking methods. This method offers significant improvements in terms of both security and efficiency, opening up new possibilities for securing AI-generated content.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on image watermarking, deepfake detection, and AI-generated content authentication. It introduces a novel, robust method that addresses the vulnerabilities of existing techniques, paving the way for more secure and reliable solutions. The research is also highly relevant to the current trend of increasing use of generative AI models, as it directly contributes to the development of methods for verifying and authenticating AI generated content, which is becoming increasingly important for various applications. Furthermore, the proposed two-stage approach provides new avenues for research in the area of efficient watermarking, opening doors to optimize detection processes and improve the robustness to forgery attacks.

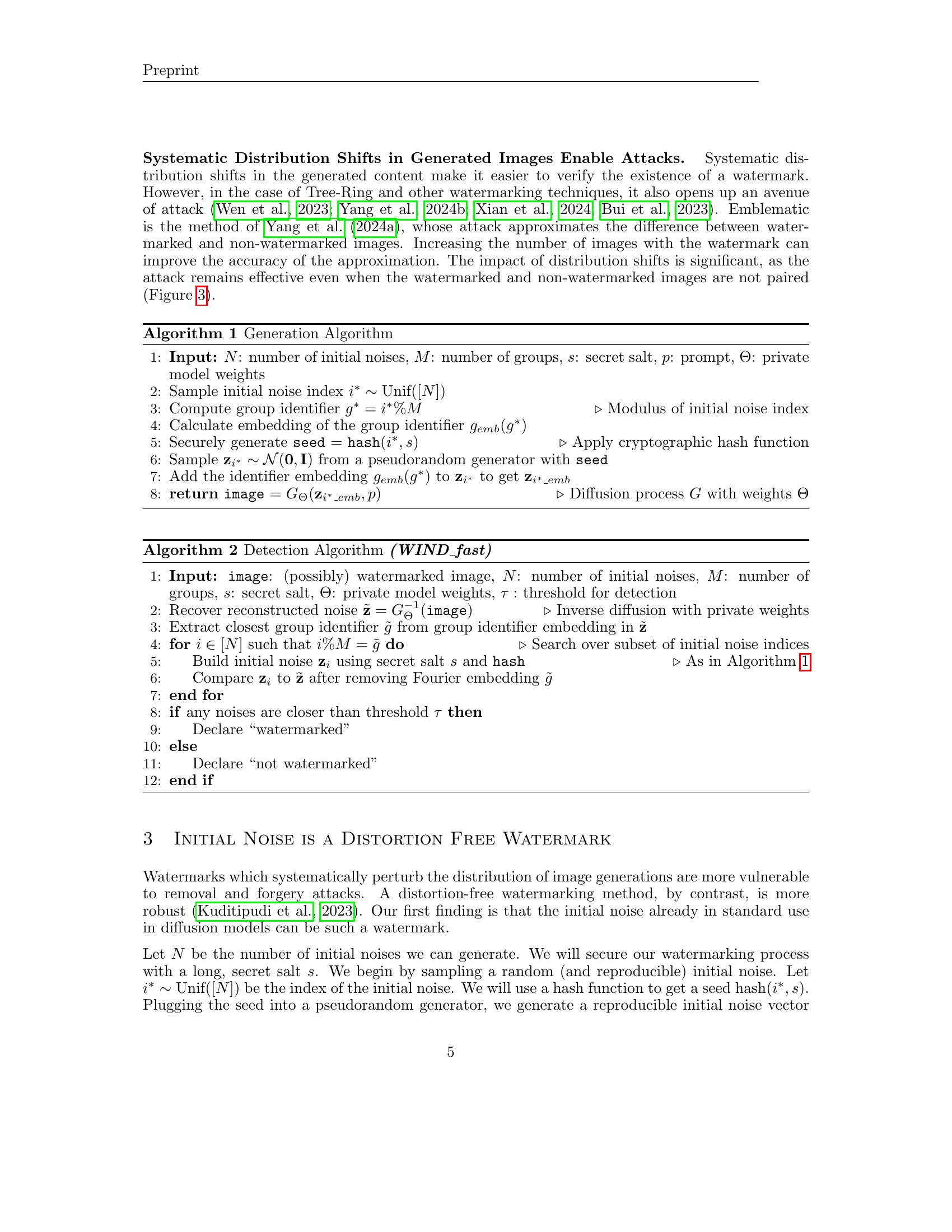

Visual Insights#

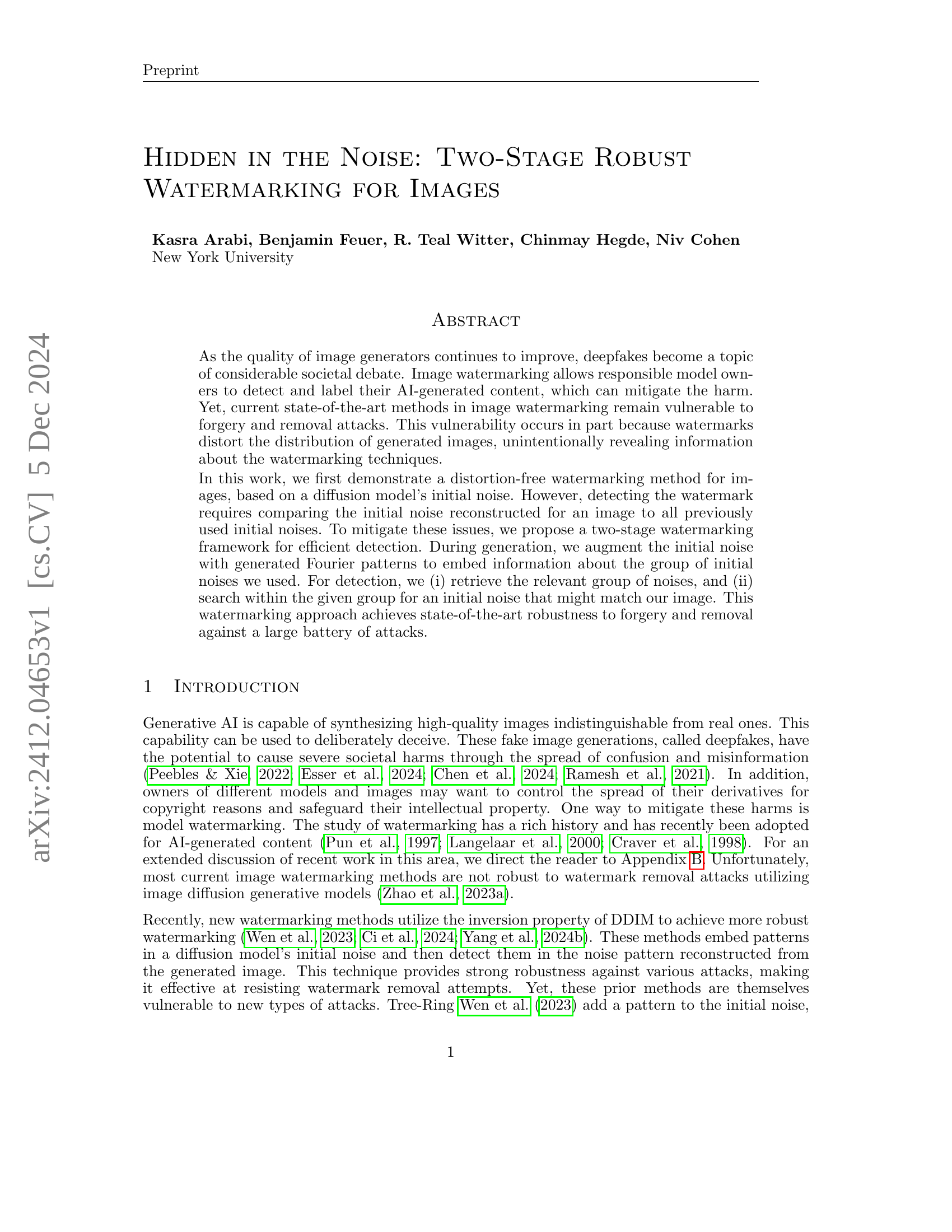

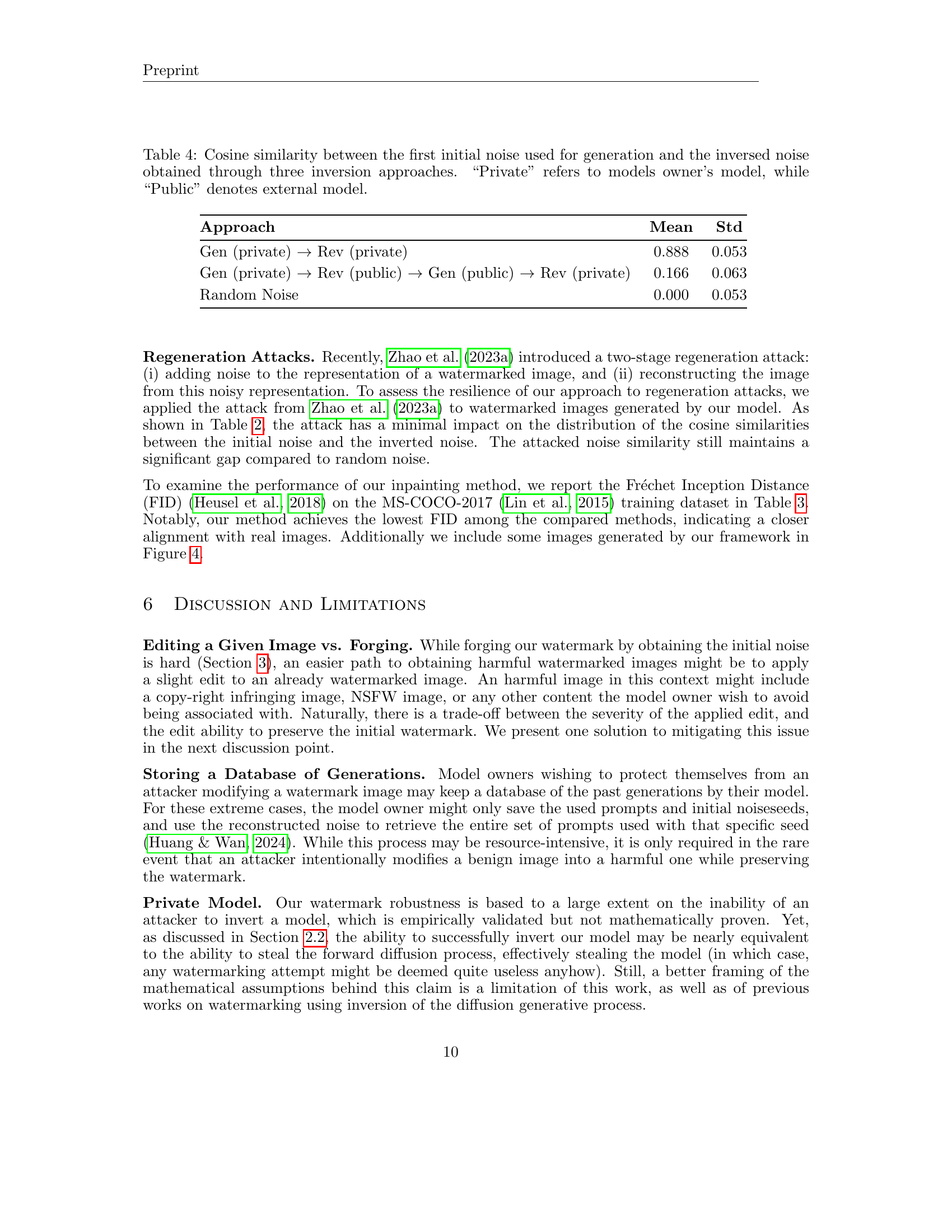

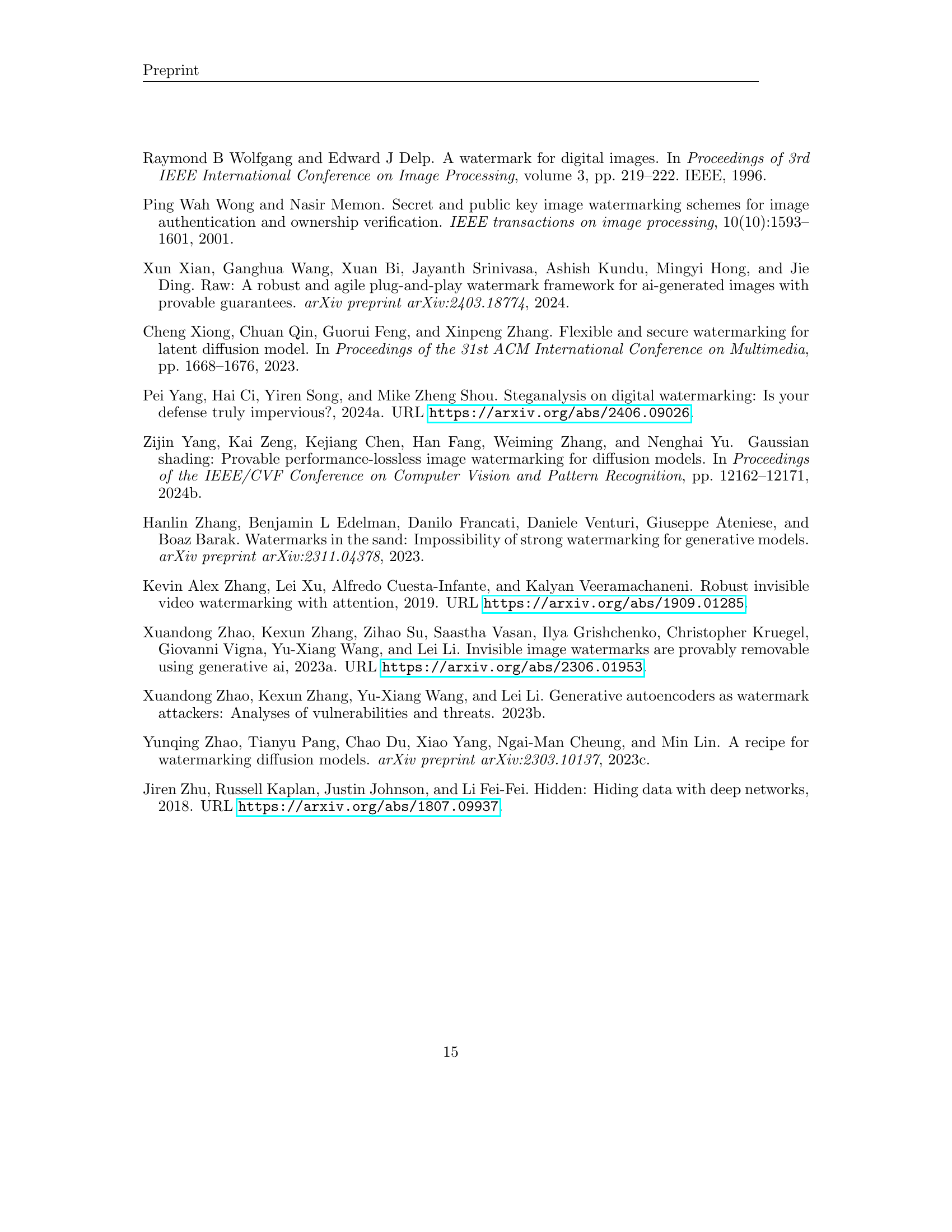

🔼 The WIND (Watermarking with Indistinguishable and Robust Noise for Diffusion Models) method uses N initial noise vectors, divided into M groups. During image generation, a secret salt and a randomly selected index (i*) are used to securely generate an initial noise vector (zi*). A group index (g*) is calculated (g* = i* % M), embedded into the noise using a Fourier pattern, and then the diffusion process generates the watermarked image. Watermark detection involves inverse diffusion to reconstruct the initial noise (z~). The algorithm then searches for the closest group index (g~) based on the Fourier pattern in z~, and finally compares the noise indices within that group (g~) to find a match with the original noise vector. This two-stage approach improves efficiency and robustness.

read the caption

Figure 1: The WIND method for robust image watermaking. The method is designed to use N𝑁Nitalic_N possible initial noises splitted to M𝑀Mitalic_M groups. Generation: Using a secret salt and an index i∗superscript𝑖i^{*}italic_i start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ∗ end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT, we securely and reproducibly generate initial noise 𝐳i∗subscript𝐳superscript𝑖\mathbf{z}_{i^{*}}bold_z start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ∗ end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT end_POSTSUBSCRIPT. We then embed a group index g∗superscript𝑔g^{*}italic_g start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT ∗ end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT of that noise to make easier retrieval possible and embed it using a Fourier pattern. Finally, we run diffusion with the embedded latent noise to produce a watermarked image. Detection: We reconstruct the initial noise 𝐳~~𝐳\tilde{\mathbf{z}}over~ start_ARG bold_z end_ARG. Next, we search over the possible group indices g𝑔gitalic_g for the closest Fourier pattern to the one embedded in 𝐳~~𝐳\tilde{\mathbf{z}}over~ start_ARG bold_z end_ARG. We then look over initial noises in group g~~𝑔\tilde{g}over~ start_ARG italic_g end_ARG to find the match.

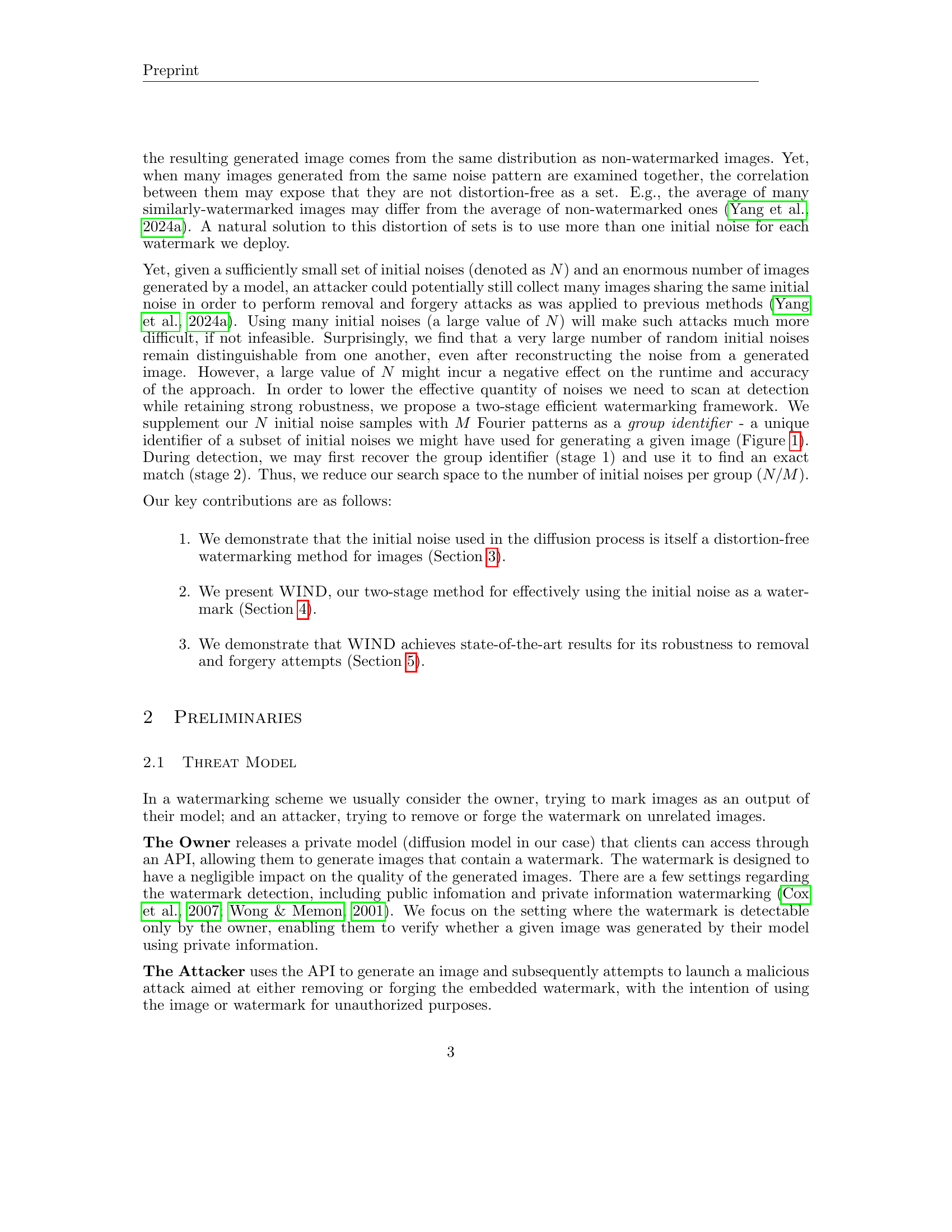

| Method | Keys | Clean | Rotate | JPEG | C&S | Blur | Noise | Bright | Avg ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree-Ring | 32 | 0.790 | 0.020 | 0.420 | 0.040 | 0.610 | 0.530 | 0.420 | 0.404 |

| 128 | 0.450 | 0.010 | 0.120 | 0.020 | 0.280 | 0.230 | 0.170 | 0.183 | |

| 2048 | 0.200 | 0.000 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.090 | 0.070 | 0.060 | 0.066 | |

| RingID | 32 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.530 | 0.990 | 1.000 | 0.960 | 0.926 |

| 128 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 0.280 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 0.940 | 0.883 | |

| 2048 | 1.000 | 0.860 | 1.000 | 0.080 | 0.970 | 0.950 | 0.870 | 0.819 | |

| WINDfast128 | 100000 | 1.000 | 0.780 | 1.000 | 0.470 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.960 | 0.887 |

| WINDfast2048 | 100000 | 1.000 | 0.870 | 0.960 | 0.060 | 0.960 | 0.950 | 0.900 | 0.814 |

| WINDfull128 | 100000 | 1.000 | 0.780 | 1.000 | 0.850 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.947 |

| WINDfull2048 | 100000 | 1.000 | 0.880 | 1.000 | 0.930 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 0.980 | 0.969 |

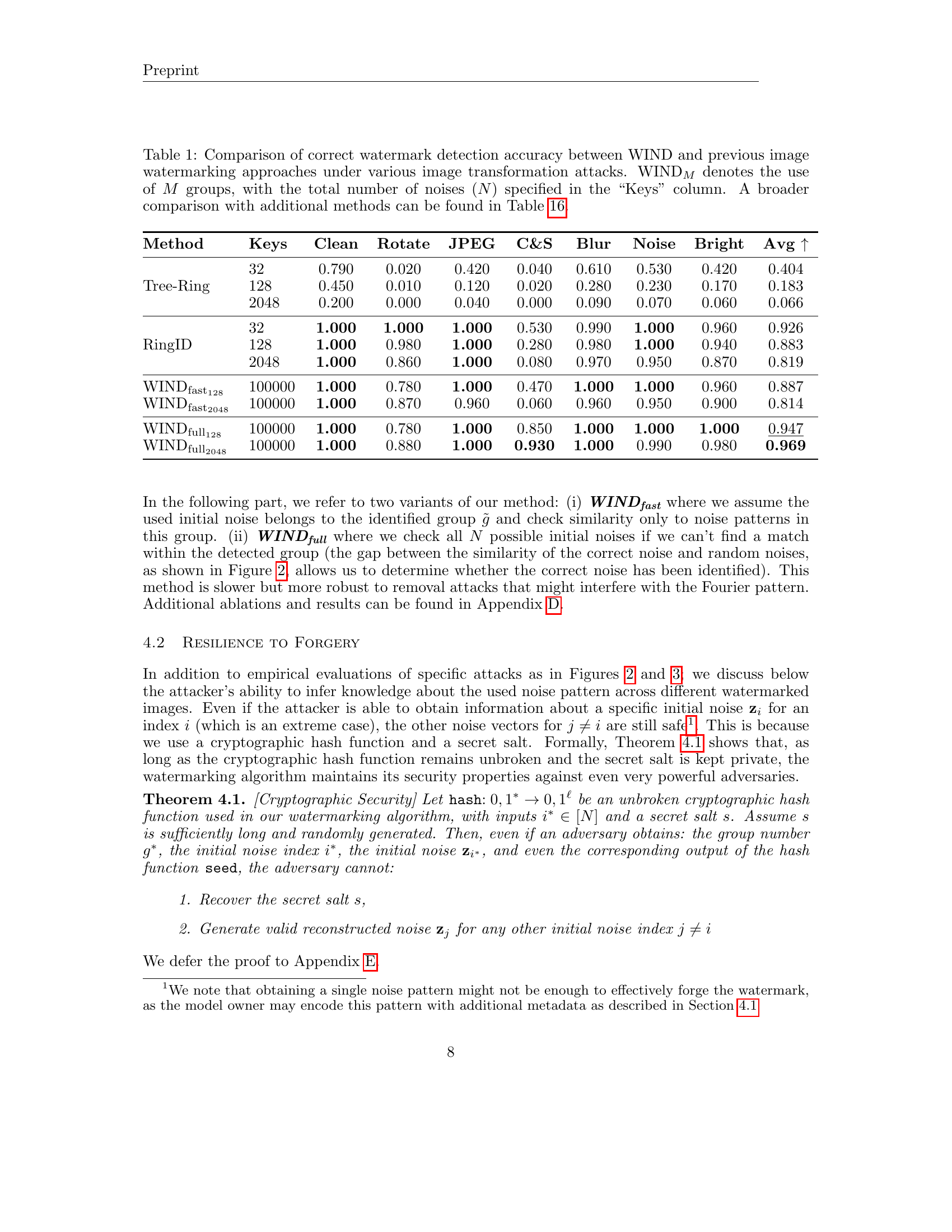

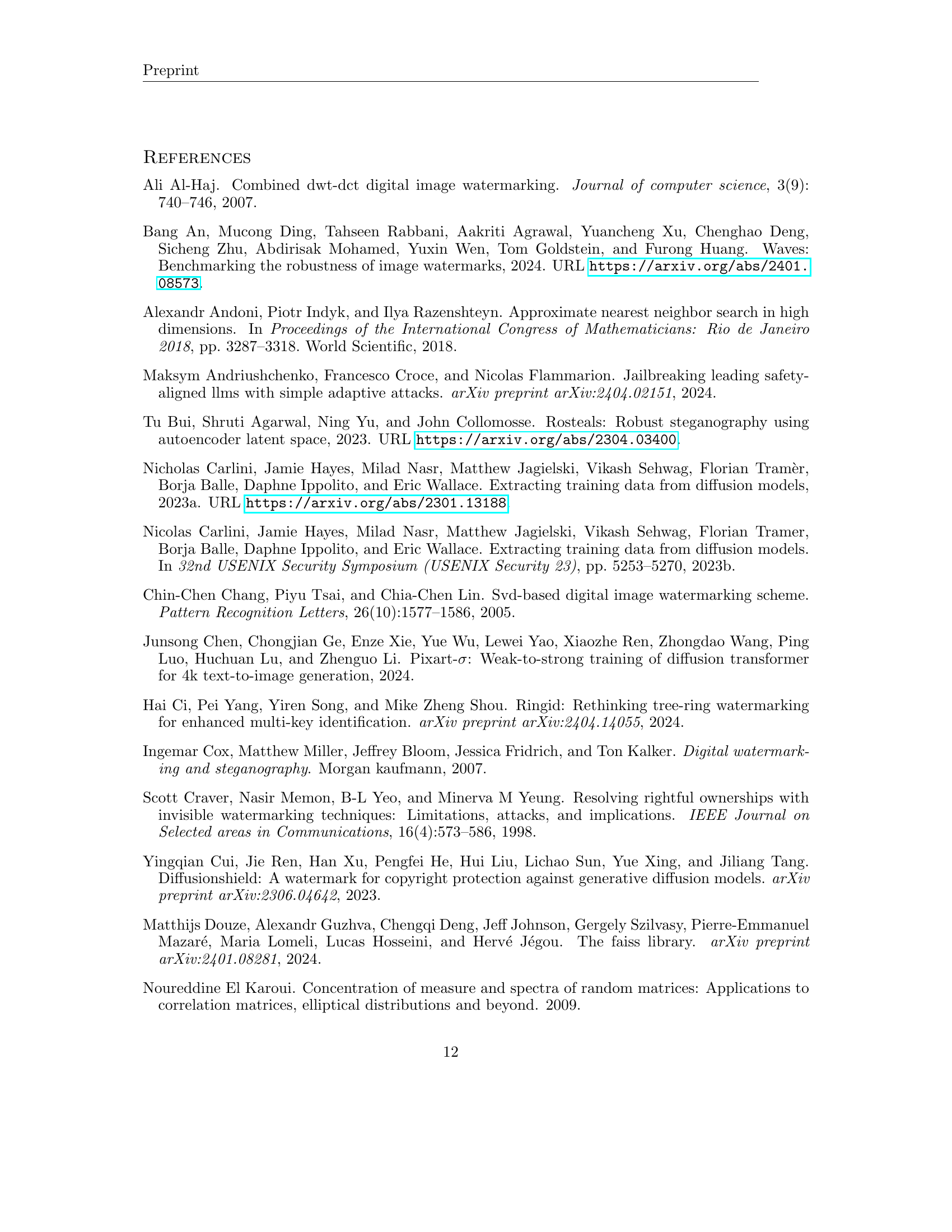

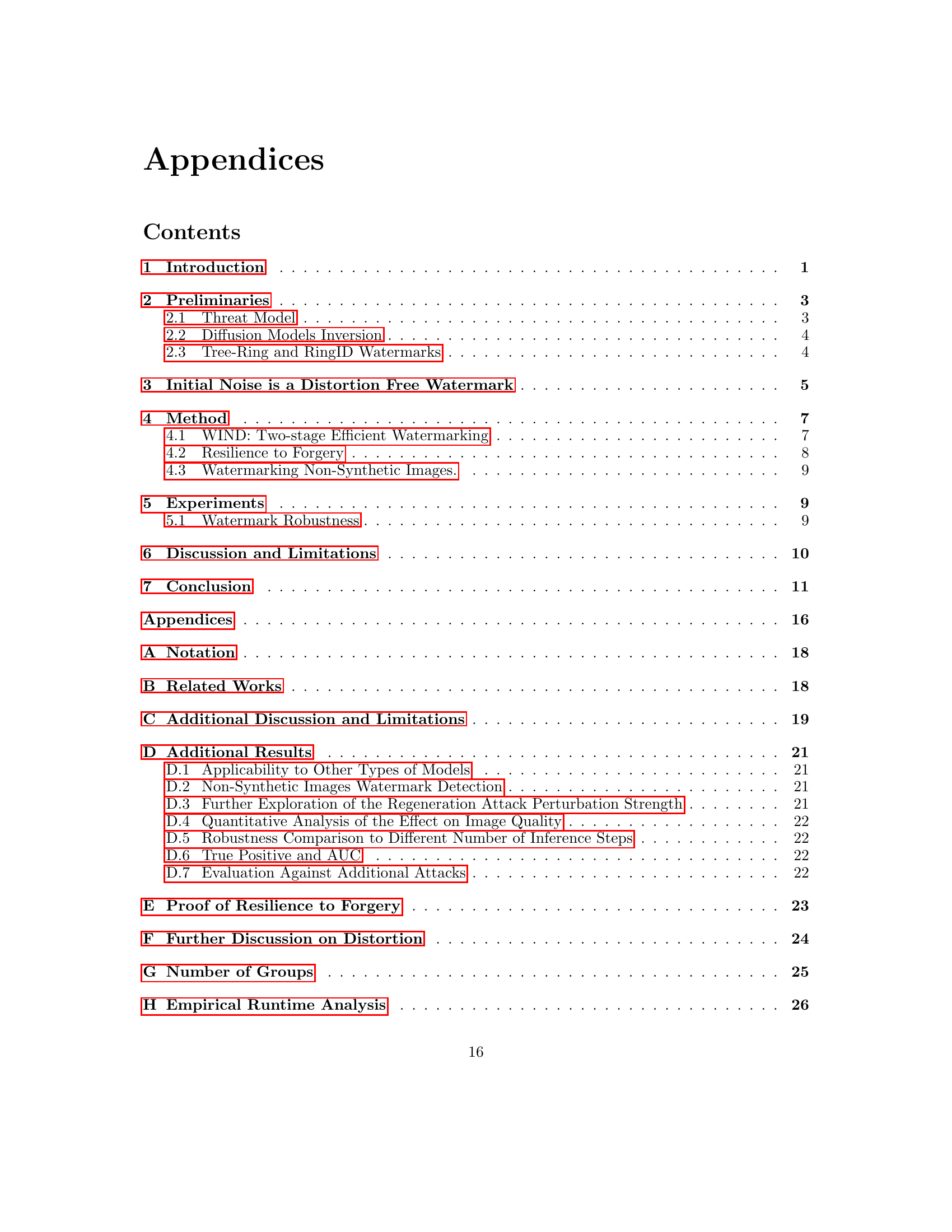

🔼 This table compares the accuracy of watermark detection for the proposed method (WIND) and two existing methods (Tree-Ring and RingID) across various image transformations (clean, rotation, JPEG compression, cropping and scaling, blurring, noise addition, brightness adjustment). The accuracy is evaluated for different numbers of initial noises used for the WIND method, denoted as WINDM (where M is the number of groups of noises). The table highlights the robustness of each method against common attacks that aim to remove or distort the watermark.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of correct watermark detection accuracy between WIND and previous image watermarking approaches under various image transformation attacks. WINDMsubscriptWIND𝑀\text{WIND}_{M}WIND start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_M end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denotes the use of M𝑀Mitalic_M groups, with the total number of noises (N𝑁Nitalic_N) specified in the “Keys” column. A broader comparison with additional methods can be found in Table 16.

In-depth insights#

Noise-based Watermarking#

Noise-based watermarking presents a novel approach to embedding imperceptible information within digital images, leveraging the inherent randomness of noise. Its strength lies in its potential for distortion-free watermarking, meaning the watermarked image statistically resembles an unwatermarked one, making it resistant to detection and removal attempts that target image distortions. By embedding the watermark in the initial noise vector of a diffusion model, the method cleverly avoids introducing visual artifacts. However, the reliance on initial noise necessitates careful management of noise patterns across multiple image generations to prevent statistical leakage. A two-stage framework is proposed to tackle this: augmenting the noise with a Fourier pattern for grouping similar noises and then searching within those groups for a match during detection. This two-stage process significantly improves efficiency and robustness, enabling efficient search across a large space of possible noise patterns while preserving strong resistance to both removal and forgery attacks. The cryptographic security of the method hinges on the secure generation of the initial noise, using secret salts and hash functions to maintain the integrity of the watermark.

Two-Stage Detection#

A two-stage detection system for watermarking offers a compelling approach to balance efficiency and robustness. The first stage, a coarse filtering, likely involves identifying a group or class of initial noise patterns using a fast algorithm like a hash function or nearest neighbor search. This significantly reduces the search space for the second stage. The second stage, fine-grained verification, then compares the reconstructed initial noise to candidates within the pre-selected group from the first stage, offering a precise match. This strategy is crucial as it addresses a key challenge of existing techniques: the computational cost of searching a vast number of potential watermarks. By significantly narrowing the search space, this two-stage approach enhances the practicality and speed of watermark detection while preserving accuracy. This method likely achieves a trade-off between computational cost and detection accuracy. A faster, less accurate first stage allows a slower, more accurate second stage, which is ideal for applications where security is paramount.

Robustness Analysis#

A robust watermarking scheme needs to withstand various attacks aiming to remove or forge the watermark. A thorough robustness analysis would assess the watermark’s resilience against a wide range of attacks including removal attacks (e.g., image manipulation, filtering, compression), forgery attacks (e.g., adding the watermark to unauthorized images), and geometric attacks (e.g., rotations, scaling, cropping). The analysis should not only focus on the watermark’s survival rate under these attacks but also quantify the impact on the detection accuracy. Quantitative metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score are crucial. Additionally, the analysis should consider the computational cost of both watermark embedding and detection, evaluating the trade-off between robustness and efficiency. Furthermore, a robust analysis should explore the effect of various parameters like the number of watermarks, the embedding strength, and the choice of image transformations on the overall performance. Investigating the impact of noise and other image artifacts is also important for realistic evaluation. Finally, the analysis should also take into account the potential for adaptive attacks, where an adversary learns from previous attacks to improve their chances of removing or forging the watermark.

Forgery Attack Limits#

Forgery attacks against watermarked images are a critical concern in digital watermarking research. A robust watermarking scheme must be designed to withstand such attacks. The ‘Forgery Attack Limits’ section of a research paper would likely delve into the types of forgeries attempted, the methods used to create them (e.g., deepfake techniques, image editing software), and importantly, the success rate of these forgeries in removing or altering the embedded watermark. The analysis would likely involve metrics to quantify the effectiveness of the forgery attempts, such as the percentage of successful watermark removals or distortions, or perhaps by examining the changes in the statistical properties of the watermarked images after a forgery attempt. A significant part would be dedicated to describing the limitations of current state-of-the-art forgery techniques and possibly proposing novel defenses or improvements to enhance robustness. Ultimately, this section provides critical information for evaluating the overall security and reliability of the watermarking method, particularly its resilience to sophisticated attack methods. A thorough examination of forgery attack limits allows researchers to gauge the real-world effectiveness of their watermarking schemes. The conclusions would ideally offer insights into future research directions, identifying areas where further improvements are needed to provide robust protection against evolving forgery methods.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for robust image watermarking should prioritize developing more sophisticated methods to embed watermarks, moving beyond simple patterns in initial noise. This could involve exploring more complex, less predictable encoding techniques that better resist removal attacks. Further research into distortion-free watermarking techniques is crucial; current methods often subtly alter the image distribution, revealing information about the watermark itself. The field would benefit from a deeper understanding of the interplay between watermark robustness and perceptual quality. Ultimately, the aim should be to create a system with imperceptible watermarks that are highly robust against a wide range of attacks, both known and unforeseen. This requires a comprehensive threat model encompassing existing and emerging image manipulation techniques, along with advancements in defensive measures. Finally, the development of efficient and scalable watermarking algorithms is paramount to ensure broad applicability across various scenarios and datasets.

More visual insights#

More on figures

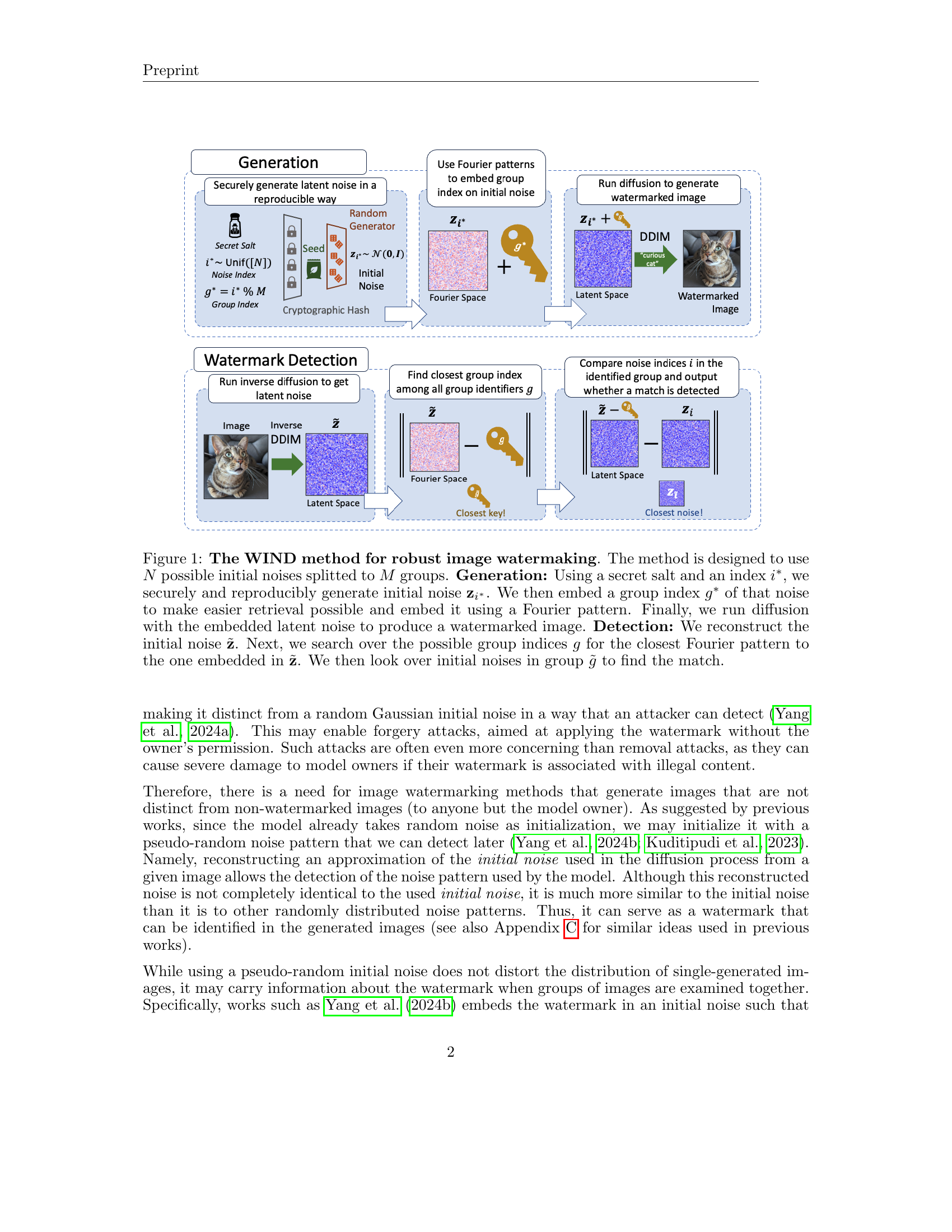

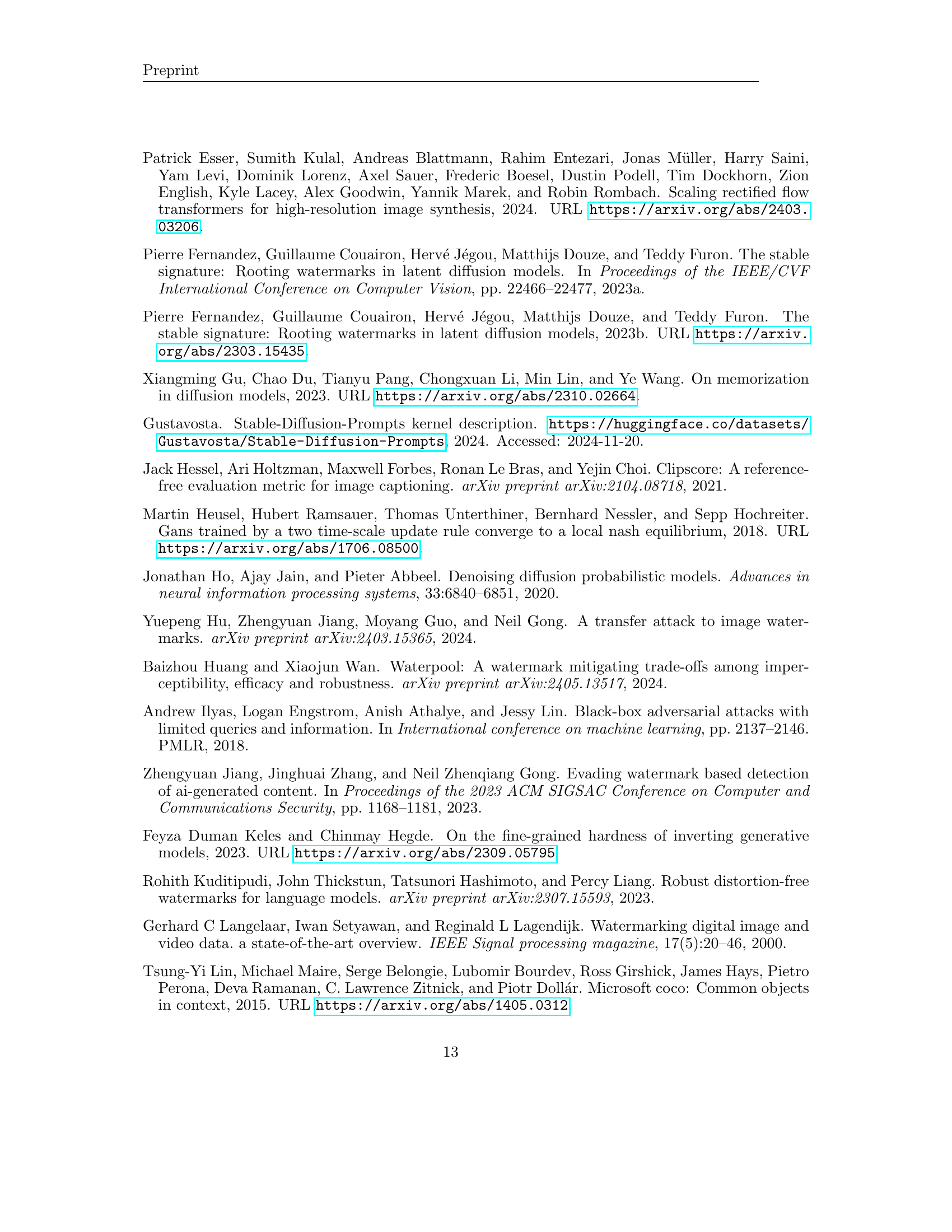

🔼 This figure displays histograms showing the cosine similarity between the original initial noise used to generate a watermarked image and three other noise sources. The first histogram shows the similarity to the noise reconstructed from the watermarked image using a reverse diffusion process (a perfect reconstruction scenario). The second histogram represents similarity to noise reconstructed from a forged image which was created by an attacker using a publicly available model to mimic the watermarked image, demonstrating the robustness of the method against such attacks. The third histogram shows the similarity to completely random noise, representing a baseline comparison. The results highlight the high similarity between the initial noise and the noise reconstructed from a legitimately watermarked image, while revealing a significant drop in similarity when compared to the forged and random noises. This difference validates the effectiveness of the proposed watermarking technique.

read the caption

Figure 2: Cosine similarity distribution between initial noise, and: (i) a noise reconstructed from a watermarked image (reconstructed noise) (ii) a noise reconstructed from a forged image using a public model to imitate our watermarked image (reconstruction attack, described in Section 3). (iii) Random noise. These results are reliant on the approximate inversion of DDIM without the ground-truth prompt.

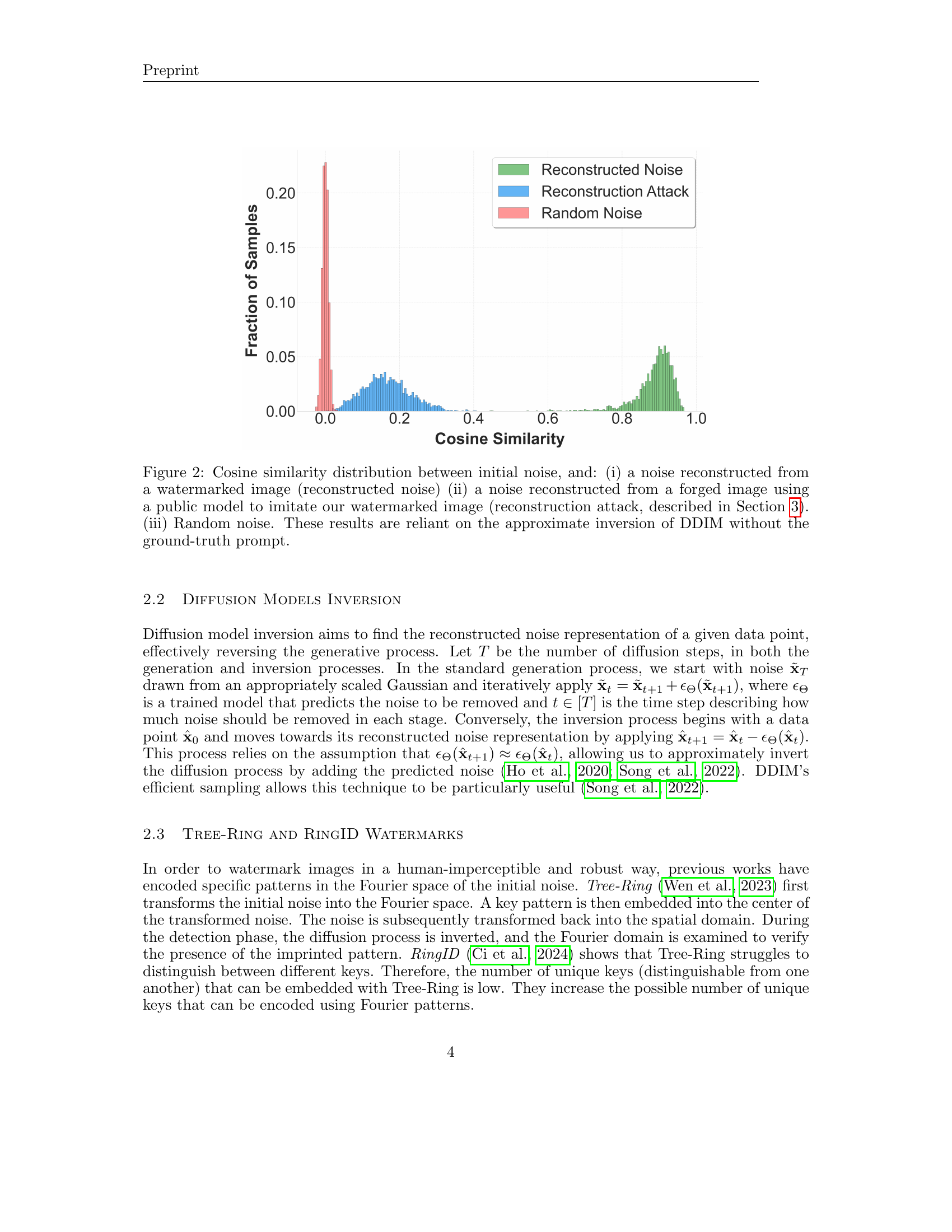

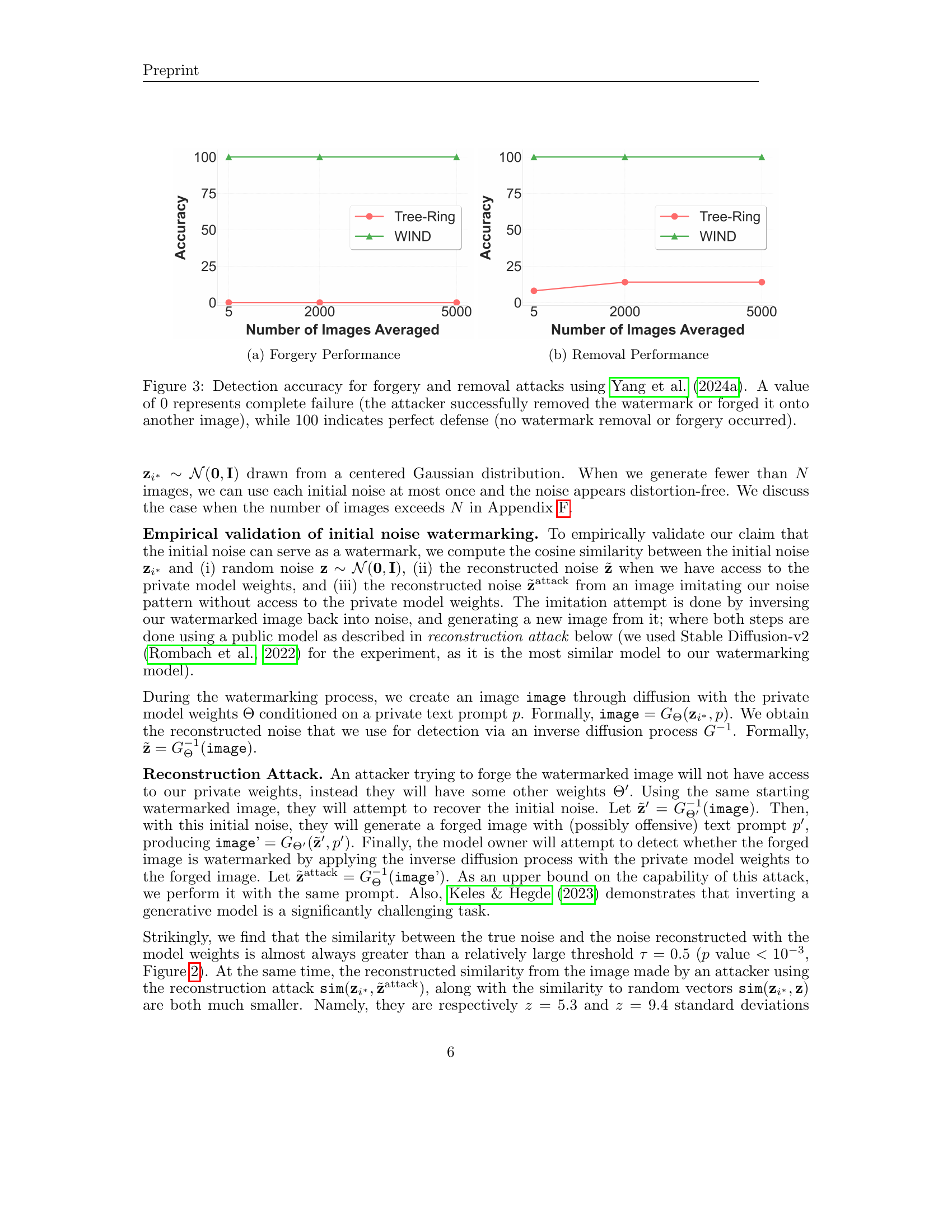

🔼 This figure displays the accuracy of watermark forgery detection across varying numbers of images. It showcases the effectiveness of the WIND method against forgery attacks by illustrating how the accuracy of detecting forged watermarks changes as the number of averaged images increases. A higher accuracy indicates better robustness against forgery. This is compared against the performance of a previous state-of-the-art method, Tree-Ring.

read the caption

(a) Forgery Performance

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy of watermark removal attacks. The x-axis represents the number of images averaged in the attack, and the y-axis represents the accuracy of the watermark detection. A value of 0 indicates complete failure (the watermark was successfully removed), while a value of 100 indicates perfect defense (the watermark was not removed). The figure compares the performance of the WIND method against the Tree-Ring method. It demonstrates the effectiveness of WIND in resisting watermark removal attacks, showing a significantly higher accuracy compared to Tree-Ring across various numbers of averaged images.

read the caption

(b) Removal Performance

🔼 This figure showcases the performance comparison between the proposed WIND watermarking method and the Tree-Ring method in terms of robustness against forgery and removal attacks, following the methodology introduced by Yang et al. (2024a). The x-axis represents the number of images averaged for evaluation. The y-axis indicates the accuracy of watermark detection (0% representing complete failure; 100% representing perfect defense). Separate graphs illustrate the accuracy for forgery attacks (left) and removal attacks (right), highlighting the superior performance of WIND.

read the caption

Figure 3: Detection accuracy for forgery and removal attacks using Yang et al. (2024a). A value of 0 represents complete failure (the attacker successfully removed the watermark or forged it onto another image), while 100 indicates perfect defense (no watermark removal or forgery occurred).

🔼 This figure showcases a qualitative comparison of images watermarked using three different methods: WIND, Tree-Ring, and RingID. Each method’s effectiveness in embedding a watermark while preserving the image’s visual quality is visually demonstrated. The images represent diverse subjects and styles to illustrate the performance of the watermarking techniques across various contexts. The figure emphasizes the visual quality of the watermarked images, indicating that the watermark is not readily apparent to the naked eye. For a quantitative analysis of these methods, including detailed metrics of the watermarking algorithms’ performance, refer to Appendix D. Appendix J includes additional qualitative results beyond those shown in Figure 4.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative results of watermarked images generated using WIND, Tree-Ring, and RingID. See Appendix D for quantitative results. See Appendix J for additional qualitative results.

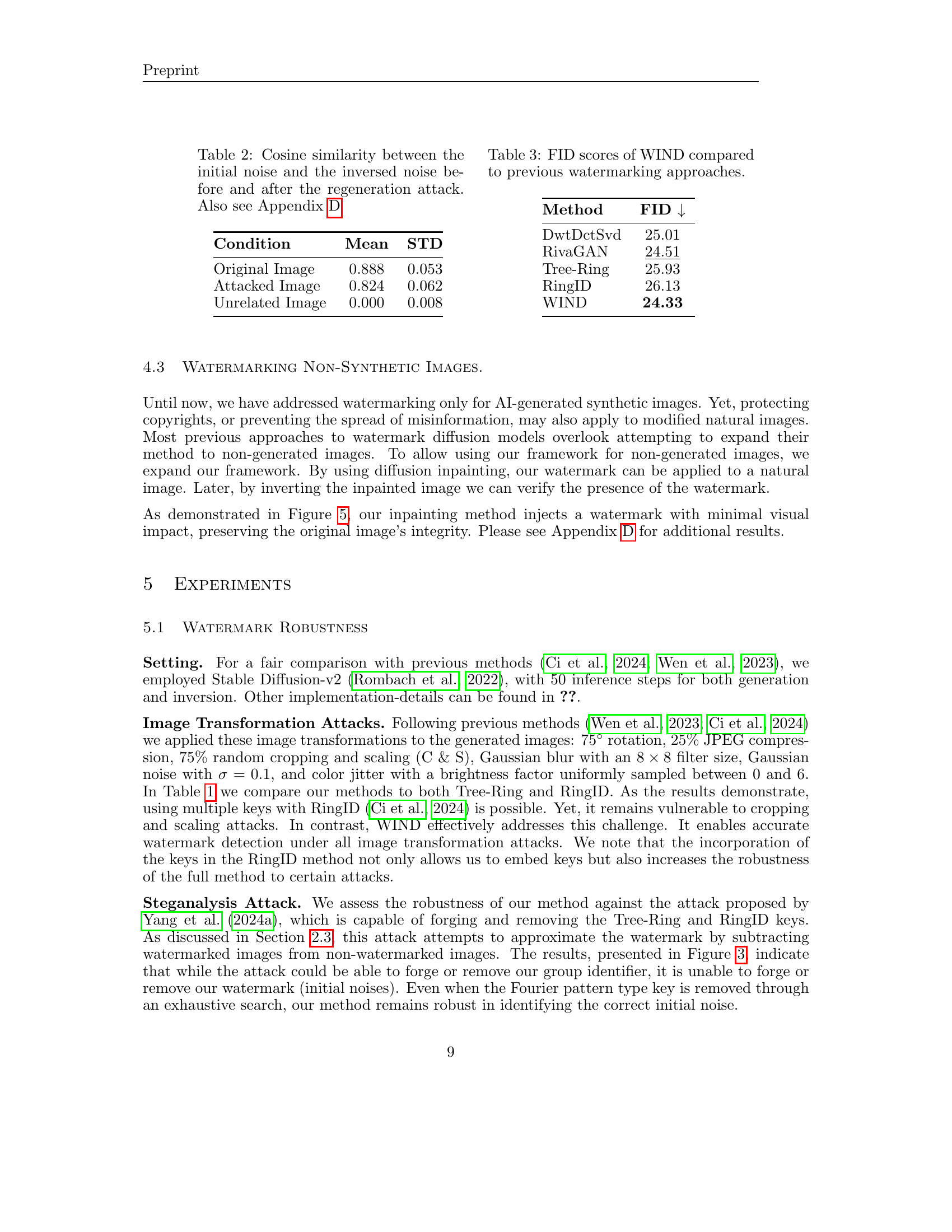

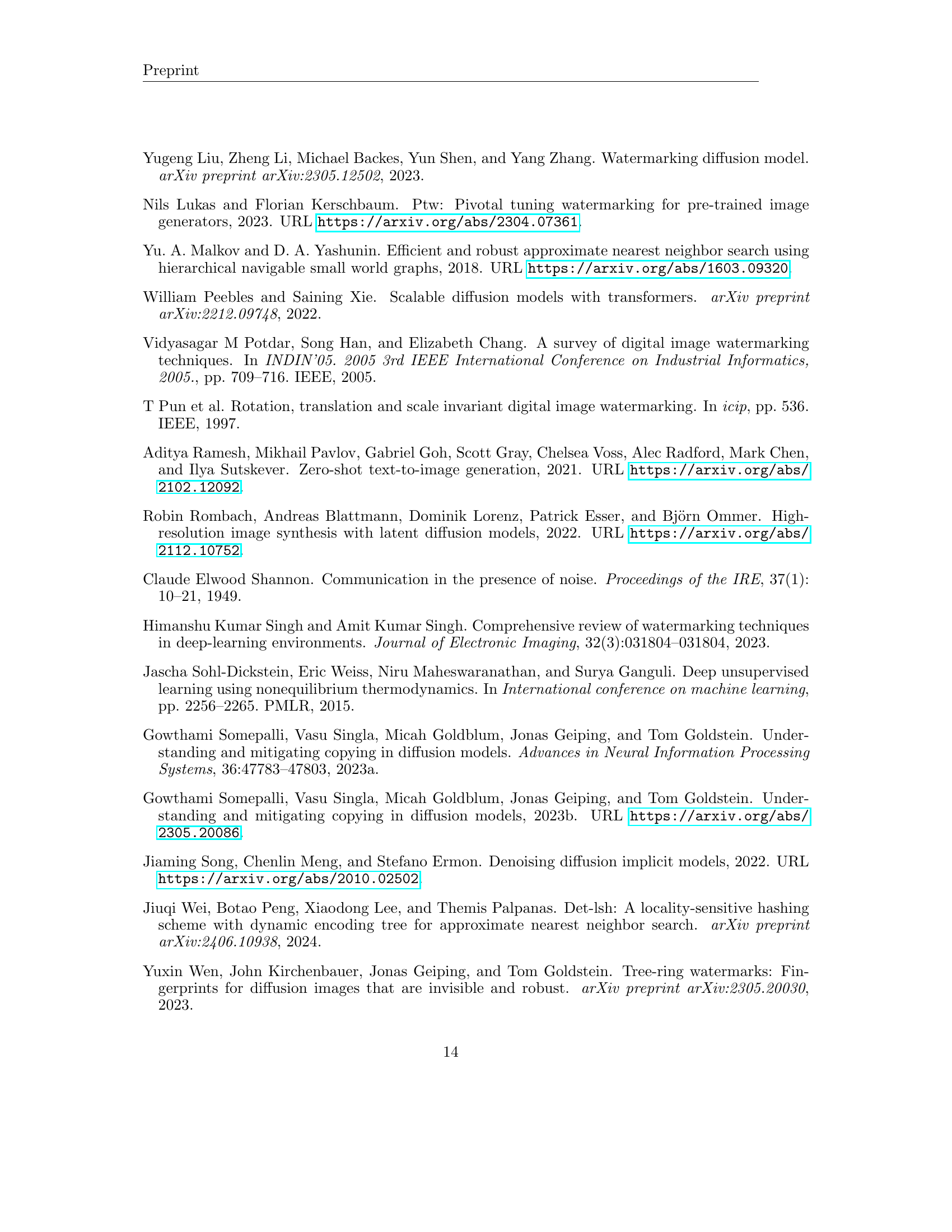

🔼 This table presents a quantitative analysis of the robustness of the proposed watermarking method against regeneration attacks. It displays the cosine similarity scores between the original initial noise used during image generation and the noise reconstructed from the watermarked image. The similarity is measured both before and after a regeneration attack is applied to the watermarked image. The table demonstrates that even after a regeneration attack, the cosine similarity between the original and reconstructed noise remains significantly high, indicating the resilience of the watermarking method to this type of attack. Further details and analysis are provided in Appendix D of the paper.

read the caption

Table 2: Cosine similarity between the initial noise and the inversed noise before and after the regeneration attack. Also see Appendix D

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores for different image watermarking techniques. The FID score is a metric used to evaluate the quality of generated images by comparing them to a dataset of real images; lower scores indicate higher image quality. The table shows that the proposed WIND method achieves a lower FID score compared to other methods (Tree-Ring, RingID, RivaGAN, DwtDctSvd), demonstrating that images watermarked using WIND maintain higher image quality.

read the caption

Table 3: FID scores of WIND compared to previous watermarking approaches.

More on tables

| Condition | Mean | STD |

|---|---|---|

| Original Image | 0.888 | 0.053 |

| Attacked Image | 0.824 | 0.062 |

| Unrelated Image | 0.000 | 0.008 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of cosine similarity scores between the initial noise used during image generation and the reconstructed noise obtained using different inversion methods. Three scenarios are compared: 1) using the model owner’s private model for both generation and inversion; 2) using the owner’s private model for generation and a public model for inversion; and 3) comparing the initial noise against completely random noise. This comparison helps demonstrate the robustness of using initial noise as a distortion-free watermark, highlighting its resilience to attacks that might attempt to reconstruct the noise using external models.

read the caption

Table 4: Cosine similarity between the first initial noise used for generation and the inversed noise obtained through three inversion approaches. “Private” refers to models owner’s model, while “Public” denotes external model.

| Method | FID ↓ |

|---|---|

| DwtDctSvd | 25.01 |

| RivaGAN | 24.51 |

| Tree-Ring | 25.93 |

| RingID | 26.13 |

| WIND | 24.33 |

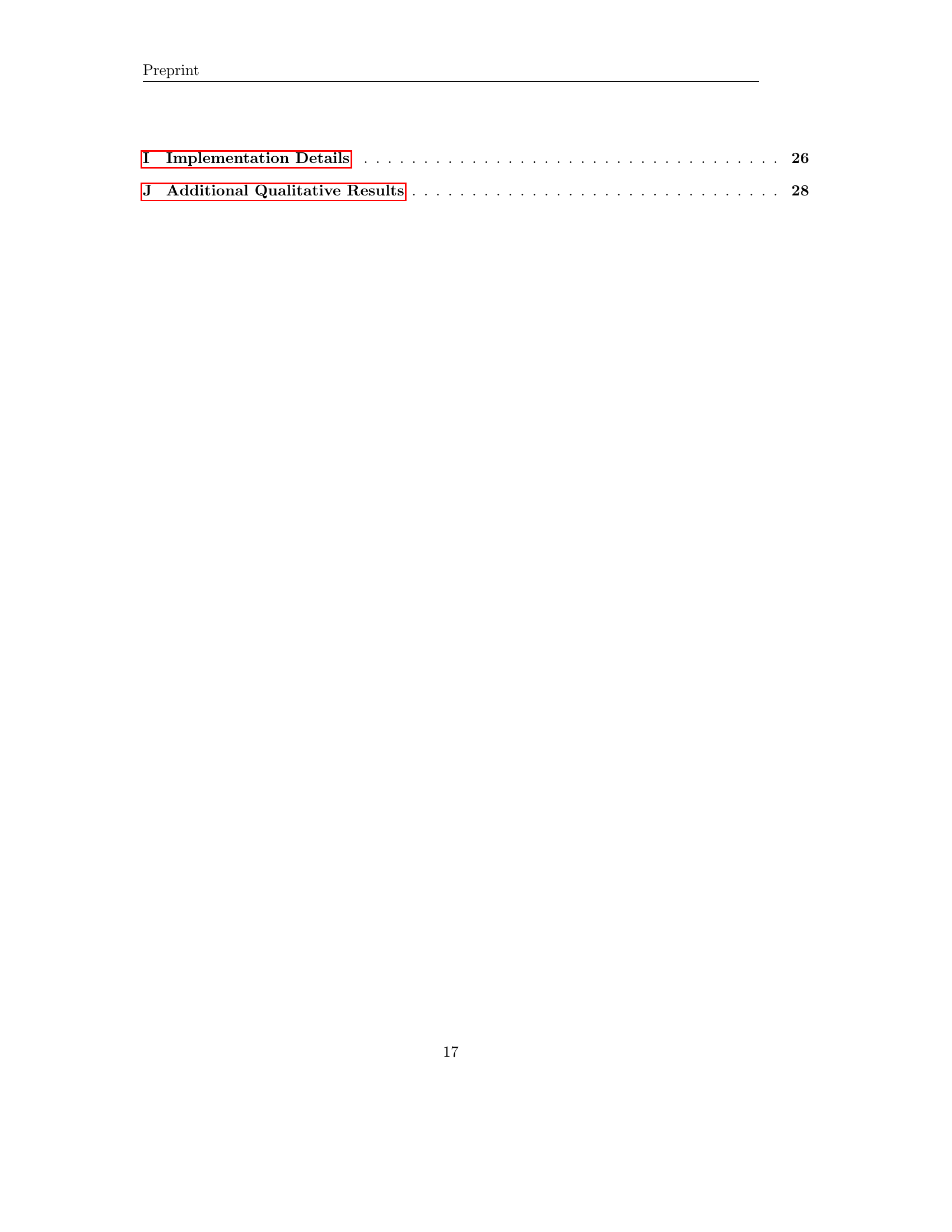

🔼 This table lists the notations used throughout the paper. For each notation, it provides a short description to clarify its meaning within the context of the paper’s mathematical and algorithmic descriptions.

read the caption

Table 5: Notations used in the paper.

| Approach | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|

| Gen (private) → Rev (private) | 0.888 | 0.053 |

| Gen (private) → Rev (public) → Gen (public) → Rev (private) | 0.166 | 0.063 |

| Random Noise | 0.000 | 0.053 |

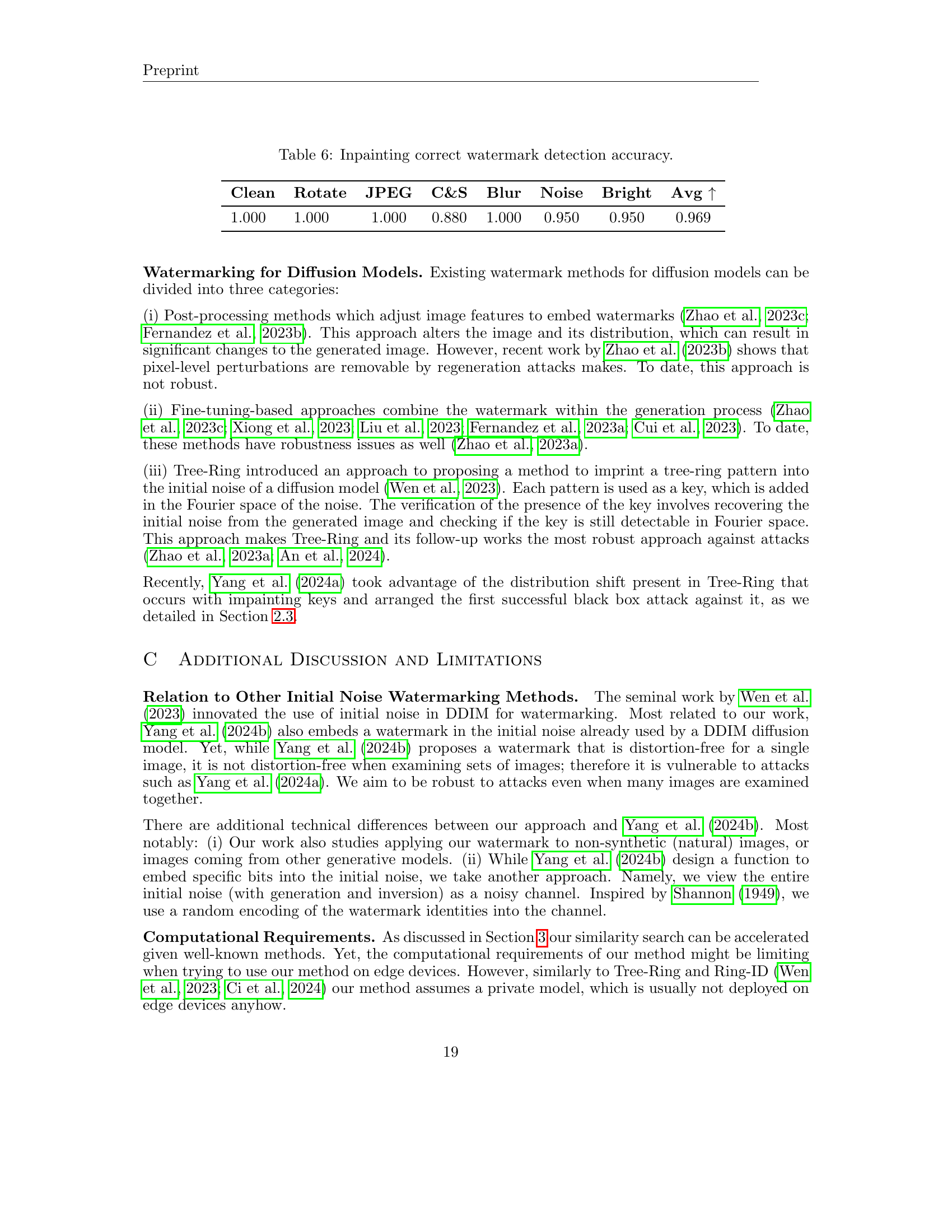

🔼 This table presents the accuracy of watermark detection after applying various image transformations (Clean, Rotate, JPEG, C&S, Blur, Noise, Bright) to images that have been watermarked using the inpainting method. The accuracy is measured as the percentage of correctly identified watermarked images after each transformation.

read the caption

Table 6: Inpainting correct watermark detection accuracy.

| Before | After | Before | After |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the effect of varying the number of inference steps during the image generation and reconstruction processes on the accuracy of watermark detection. Different numbers of steps were tested (20, 50, 100, 200), and the detection accuracy is reported for several image transformation attacks (Clean, Rotate, JPEG, C&S, Blur, Noise, Bright) to assess the robustness of the watermarking method under different conditions.

read the caption

Table 7: Impact of different inference steps on detection accuracy.

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| N | Number of initial noises |

| M | Number groups |

| s | Secret salt for cryptographic security |

| i | Index of initial noise: i∈[N] |

| g | Index of group: g=i%M |

| hash | A cryptographic hash function |

| z | Initial noise |

| τ | Threshold for declaring an image is watermarked |

| T | Number of diffusion steps |

| Θ | Weights of a diffusion model |

| p | Text prompt for diffusion |

| GΘ | Diffusion model with weights Θ |

| G-1Θ | Inverse diffusion model with weights Θ |

🔼 This table presents the error bars, specifically the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and True Positive Rate at 1% False Positive Rate (TPR@1%FPR), for the WIND watermarking method. These metrics provide a more comprehensive understanding of the accuracy and reliability of the WIND method in detecting watermarks, showing the variability and range of its performance.

read the caption

Table 8: Error bars of WIND.

| Clean | Rotate | JPEG | C&S | Blur | Noise | Bright | Avg ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.880 | 1.000 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.969 |

🔼 This table presents the success rates of several additional attacks against the proposed watermarking method, WIND. These attacks are designed to test the robustness of WIND beyond the standard image transformation attacks. The attacks included are WeVade, Random Search, Transfer Attack, and NES Query. Each attack aims to remove or forge the watermark in different ways. The results show the percentage of successful attacks for each method.

read the caption

Table 9: Success rate of additional attacks.

| Steps | Clean | Rotate | JPEG | C&S | Blur | Noise | Bright | Avg ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 1.000 | 0.780 | 1.000 | 0.880 | 0.920 | 1.000 | 0.960 | 0.934 |

| 50 | 1.000 | 0.930 | 1.000 | 0.940 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.976 |

| 100 | 1.000 | 0.930 | 1.000 | 0.940 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 0.980 |

| 200 | 1.000 | 0.850 | 1.000 | 0.940 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.970 |

🔼 This table presents the CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) scores for images before and after applying the WIND watermarking technique. The CLIP score measures the alignment between an image and its textual description, indicating the image’s quality and semantic consistency. By comparing the scores before and after watermarking, we can assess the impact of the watermark on the image’s perceptual quality and semantic meaning. A negligible difference suggests that WIND’s watermarking process does not significantly affect image quality.

read the caption

Table 10: Effect of WIND on CLIP score.

| AUC | TP@1% |

|---|---|

| 0.971 | 1.000 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the structural similarity index (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) values for several different image watermarking techniques. It shows how well each method preserves the quality of the watermarked images compared to the originals. The methods compared are WIND (with and without group identifiers), Tree-Ring, RingID, RivaGAN, SSL, and StegaStamp. SSIM and PSNR are common metrics for evaluating the perceptual quality and distortion of an image. Higher values for both metrics generally indicate better image quality after watermarking.

read the caption

Table 11: SSIM and PSNR values of initial noise-based watermarking approaches. WINDw/ow/o{}_{\text{w/o}}start_FLOATSUBSCRIPT w/o end_FLOATSUBSCRIPT refers to the method without group identifiers

| Method | WeVade | Random Search | Transfer Attack | NES Query |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 2% | 3% | 2% |

🔼 This table presents the time taken for watermark detection in seconds using three different methods: WIND, Tree-Ring, and RingID. The detection times are compared to show the relative computational efficiency of each watermarking technique.

read the caption

Table 12: Detection time (second)

| CLIP Before Watermark | CLIP After Watermark |

|---|---|

| 0.366 | 0.360 |

🔼 This table presents the accuracy of retrieving the initial noise from a set of 10,000 samples. The 10,000 samples were divided into different numbers of groups (32, 128, 512, and 2048), and each group was subjected to various image transformation attacks (clean, rotate, JPEG compression, cropping and scaling, blur, noise addition, and brightness adjustment). The results demonstrate how the number of groups affects the accuracy of retrieving the original noise after applying these transformations.

read the caption

Table 13: Accuracy of retrieving the initial noise from 10,000 noise samples, divided into varying numbers of groups, under different image transformation attacks.

| WIND | Tree-Ring | RingID |

|---|---|---|

| 22 | 20 | 14 |

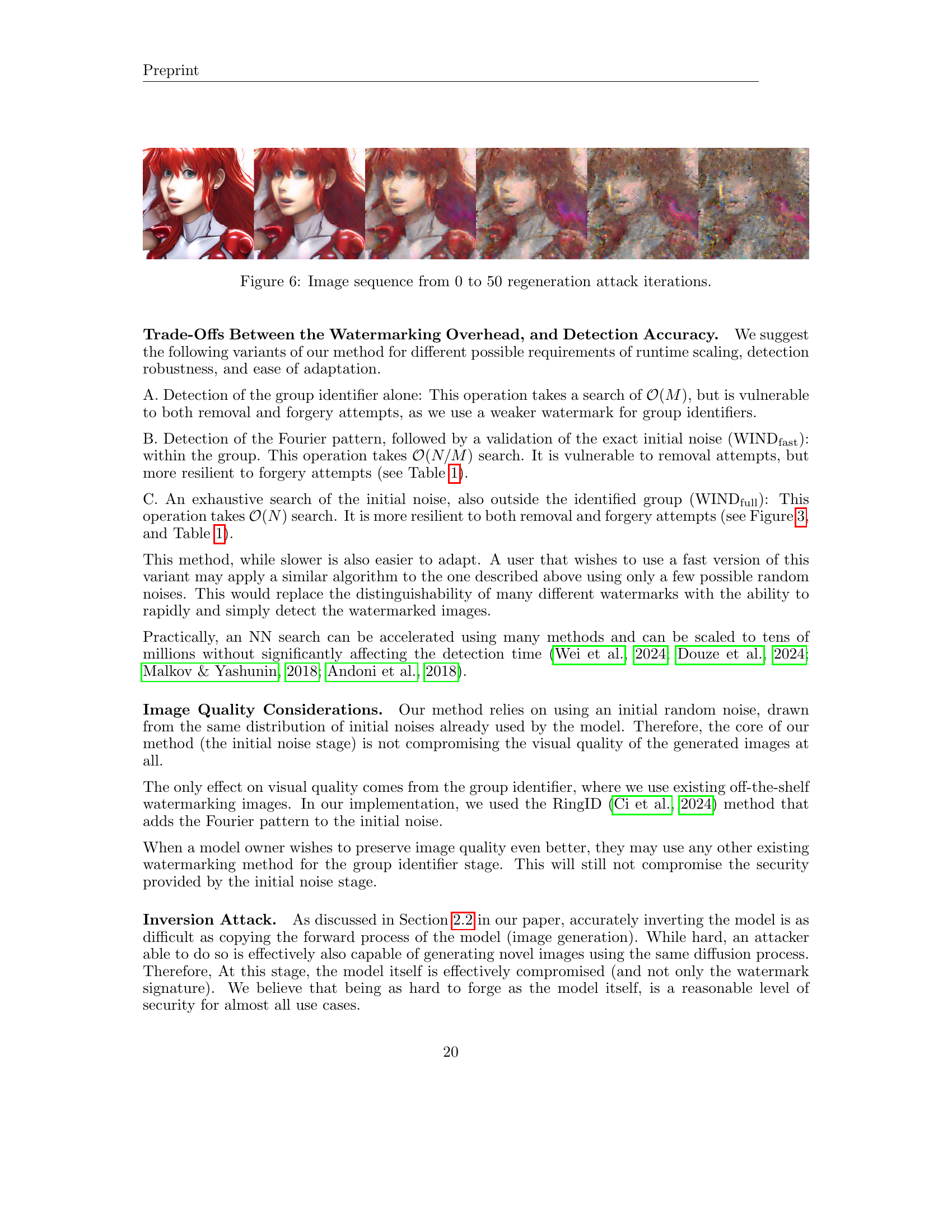

🔼 This table presents the results of a robustness test against iterative regeneration attacks. The experiment involved repeatedly applying a regeneration attack to watermarked images and then measuring the accuracy of the watermark detection system. The table shows the cosine similarity between the original and reconstructed noise after each iteration of the attack and the detection rate (percentage of correctly identified watermarks). This demonstrates the resilience of the watermarking method against this specific type of attack.

read the caption

Table 14: Correct watermark detection after iterative regeneration attack.

| Groups | Clean | Rotate | JPEG | C&S | Blur | Noise | Bright | Avg ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | 1.000 | 0.540 | 1.000 | 0.700 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 0.960 | 0.884 |

| 128 | 1.000 | 0.810 | 1.000 | 0.820 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 0.944 |

| 512 | 1.000 | 0.890 | 1.000 | 0.880 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 0.964 |

| 2048 | 1.000 | 0.930 | 1.000 | 0.940 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.976 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) and Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) values achieved by different watermarking methods when applied to non-synthetic images. SSIM and PSNR are common metrics used to assess the quality of an image after a watermark is added. Higher values indicate better image quality, meaning the watermarking method has less impact on the original image’s appearance. The table allows for a quantitative comparison of the trade-off between watermarking robustness and perceptual quality across several methods.

read the caption

Table 15: SSIM and PSNR values for non-synthetic image watermarking approaches.

| Iteration | Cosine Similarity | Detection Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.493 | 100% |

| 20 | 0.342 | 100% |

| 30 | 0.243 | 100% |

| 40 | 0.170 | 100% |

| 50 | 0.121 | 100% |

🔼 This table compares the accuracy of watermark detection for the WIND method against several existing image watermarking techniques. The comparison is done across a range of common image manipulations (transformations), including rotation, JPEG compression, cropping and scaling, blurring, adding noise, and changing brightness. The accuracy of watermark detection is presented as an average across these various attacks. The WIND method is tested with different numbers of initial noise groups (M) and a total number of noises (N) to demonstrate the impact of these parameters on robustness. Results show how well each watermarking technique preserves the watermark integrity under different attacks.

read the caption

Table 16: Comparison of correct watermark detection accuracy between WIND and previous image watermarking approaches under various image transformation attacks. WINDMsubscriptWIND𝑀\text{WIND}_{M}WIND start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_M end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denotes the use of M𝑀Mitalic_M groups, with the total number of noises (N𝑁Nitalic_N) specified in the “Keys” column.

Full paper#