↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current open-source multimodal large language models (MLLMs) struggle with complex reasoning tasks due to limitations in existing instruction-tuning datasets. These datasets often lack detailed rationales and focus on simpler tasks, hindering the development of robust MLLMs. This limits the models’ ability to tackle complex real-world problems requiring deeper reasoning.

To address these challenges, the researchers present MAmmoTH-VL, a novel approach to creating a large-scale multimodal instruction-tuning dataset. They leverage open-source models to rewrite existing datasets, adding detailed rationales and increasing task complexity. This resulted in a dataset containing 12 million instruction-response pairs. Training an MLLM on this dataset leads to state-of-the-art performance on various benchmarks, particularly those involving complex reasoning, showcasing the method’s effectiveness. This work significantly contributes to the open-source MLLM community by offering a scalable and efficient way to build high-quality multimodal datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multimodal learning and large language models. It introduces a scalable and cost-effective methodology for creating high-quality instruction-tuning datasets, addressing a major bottleneck in the field. The resulting dataset and model significantly advance the state-of-the-art, opening new avenues for research and providing valuable resources for the broader community.

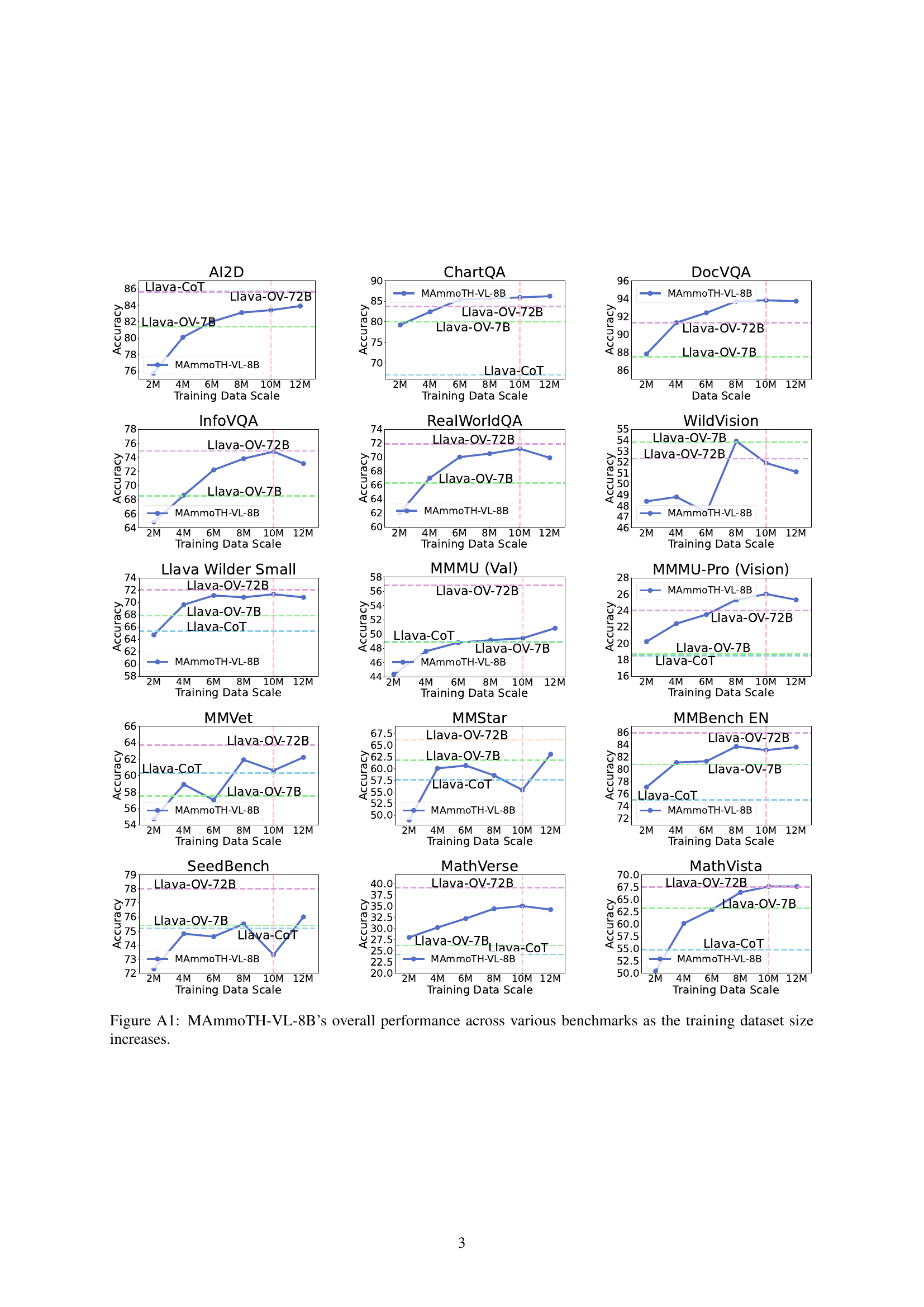

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 presents a performance comparison of the MAmmoTH-VL-8B model against several baseline models across eight multimodal datasets. The key finding is that using a simple rewriting technique with open-source language models significantly improves the quality of visual instruction data. This rewriting method encourages chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. Training MAmmoTH-VL-8B on this enhanced data leads to substantial gains in performance that scale with the model size. LLaVA-OneVision and LLaVA-CoT models serve as baselines for comparison.

read the caption

Figure 1: Scaling effects of MAmmoTH-VL-8B on eight multimodal evaluation datasets. A simple rewriting approach using open models improves the quality of visual instruction data by eliciting chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. Training on this rewritten data demonstrates significant performance gains through increased model scale. Llava-OneVision-7B&72B (Li et al., 2024b) and Llava-CoT (Xu et al., 2024a) are included as references.

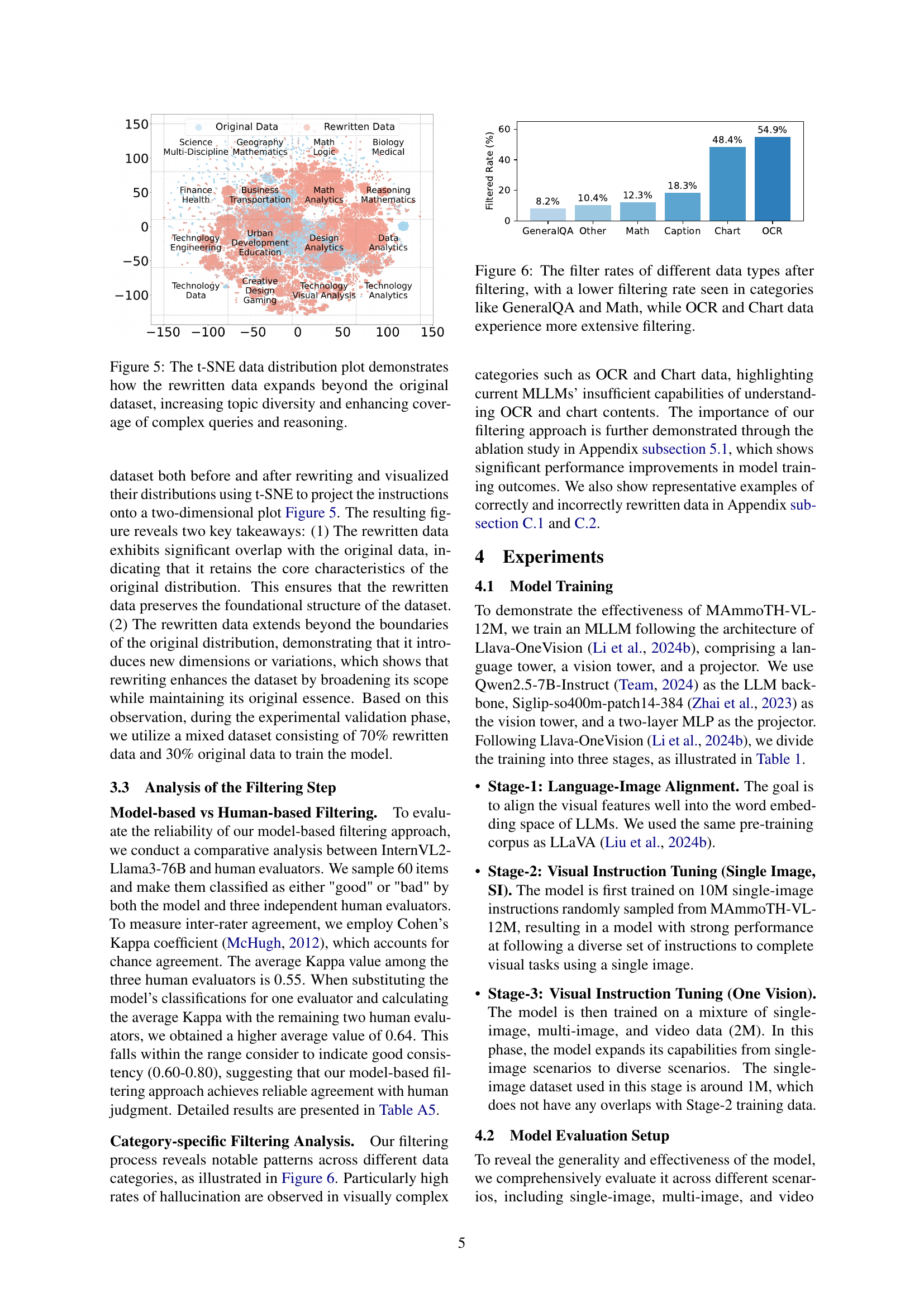

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters and settings used during the three-stage training process of the MAmmoTH-VL-8B multimodal large language model. It specifies the resolution, number of tokens, dataset used, number of samples, vision tower architecture, LLM backbone, trainable model parameters, batch size, maximum model length, and learning rates for the vision and language model components for each training stage. The stages represent distinct phases in the model’s training: Language-Image Alignment, Visual Instruction Tuning (Single Image), and Visual Instruction Tuning (One Vision).

read the caption

Table 1: Detailed configuration for each training stage of the MAmmoTH-VL-8B model.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal Reasoning#

Multimodal reasoning, the capacity to integrate and interpret information from diverse sources like text, images, and audio, is a crucial frontier in AI. The paper’s focus on eliciting this ability in large language models (LLMs) is significant because current models often struggle with reasoning-heavy multimodal tasks. This highlights a critical gap between the potential of multimodal LLMs and their actual performance. The proposed solution—a scalable, cost-effective method for creating instruction-tuning datasets with rich rationales—directly addresses this weakness. By focusing on reasoning-intensive tasks and detailed rationales, the methodology aims to move beyond simplistic tasks that dominate existing datasets. The results, showing significant improvement in reasoning benchmarks, demonstrate the success of this approach. This improvement is particularly notable in tasks requiring intricate reasoning and alignment between different modalities, suggesting the methodology’s effectiveness in fostering higher-order cognitive abilities in LLMs. However, limitations exist, particularly regarding dataset scale for multimodal tasks involving video and multiple images. Future research could explore methods to efficiently scale data collection and tackle the complexities inherent in processing these more demanding data types. The overall contribution emphasizes the need for high-quality, reasoning-focused datasets and the potential of open-source methods to bridge the gap between cutting-edge research and practical application.

Instruction Tuning#

Instruction tuning is a crucial technique for aligning large language models (LLMs) with human intentions. It involves fine-tuning pre-trained LLMs on a dataset of instruction-response pairs, enabling the model to better understand and follow diverse instructions. The key to successful instruction tuning lies in the quality and diversity of the instruction dataset. A high-quality dataset comprises various instructions, encompassing diverse levels of complexity and nuanced expression, often including detailed rationales or chain-of-thought reasoning. The scale of the dataset also significantly impacts performance, with larger, more diverse datasets leading to superior results. Furthermore, the choice of model architecture and training methodology is critical for optimizing performance and ensuring that the LLM generalizes well to unseen instructions. Careful consideration of these factors ensures a fine-tuned LLM capable of reliably following complex and nuanced instructions, ultimately enhancing its overall utility and usability.

Data Augmentation#

Data augmentation is a crucial technique in machine learning, particularly when dealing with limited datasets. In the context of multimodal learning, it is even more critical as obtaining large, diverse, high-quality multimodal datasets is expensive and time-consuming. The paper explores a novel, cost-effective approach for data augmentation that involves using open-source large language models (LLMs) to rewrite and enhance existing visual instruction datasets. This process focuses on eliciting chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning by adding detailed rationales and intermediate steps to simplistic instruction-response pairs, thus greatly expanding the amount of training data. The effectiveness of this approach is validated through experiments demonstrating significant performance gains compared to models trained on non-augmented data. The strategy prioritizes a scalable and open-source solution and avoids reliance on computationally expensive or proprietary methods for generating augmented data. The pipeline’s steps – data collection, augmentation using open LLMs, and rigorous filtering – are designed for broad applicability. Furthermore, the research highlights the importance of self-filtering techniques for data quality control, and addresses potential issues such as hallucinations during the generation of augmented data.

Open-Source Methods#

The embrace of open-source methodologies in research significantly impacts reproducibility and accessibility. Open-source code allows other researchers to verify results, adapt methods, and build upon existing work, fostering collaboration and accelerating progress. Open-access datasets democratize research by removing financial barriers and enabling broader participation. This inclusivity encourages diverse perspectives and contributes to more robust and generalizable findings. However, relying solely on open-source tools can present challenges. The quality of open-source tools and datasets can vary significantly, requiring careful evaluation and validation. Furthermore, the open-source landscape may lack the comprehensive features or specialized functionalities available in commercial software, potentially limiting the scope of some research endeavors. Successfully leveraging open-source methods requires a strategic approach, balancing cost-effectiveness with the need for quality and appropriate functionality. While open-source offers significant advantages, researchers must consider its limitations to ensure the reliability and impact of their research.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model or system to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, this involves isolating variables to determine their effect on overall performance. For a multimodal model, ablation could focus on removing specific components like the visual encoder, language model, or the fusion mechanism to understand their importance. A well-designed ablation study should highlight the relative impact of various model components, offering insights into which parts are most crucial and others that are less impactful or even detrimental. It also helps to validate design choices, determine if features are overfitting or underfitting, and refine future model iterations. By carefully controlling which components are removed and measuring the consequent changes in performance metrics, researchers can draw definitive conclusions about the model’s architecture and its strengths and weaknesses. This process is essential in building robust and explainable AI models. The insights gained from a comprehensive ablation study are invaluable to guide future research and development efforts, allowing for more efficient and effective model design.

More visual insights#

More on figures

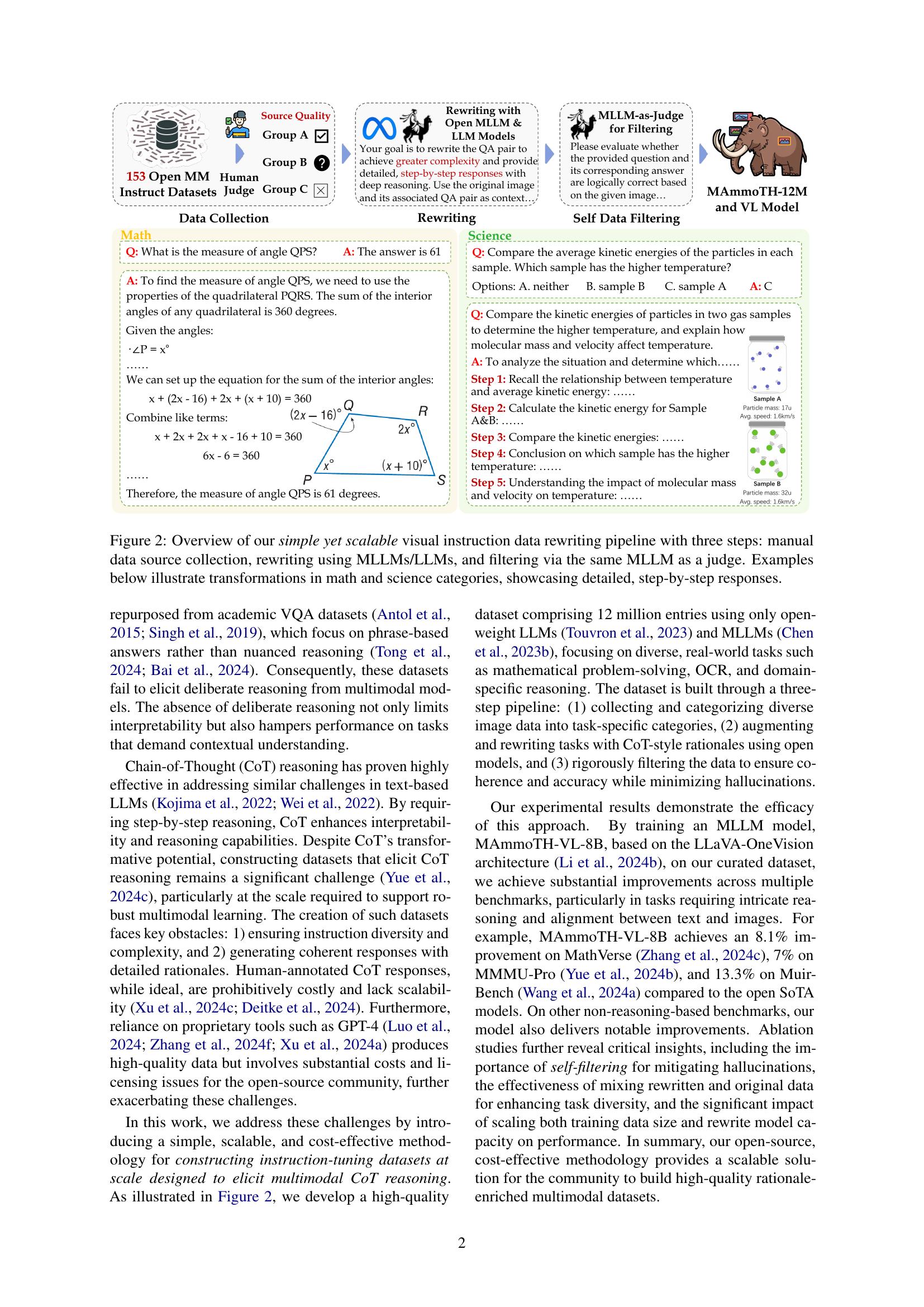

🔼 Figure 2 illustrates the three-step pipeline used to create the MAmmoTH-VL instruction dataset. First, existing open-source multimodal datasets are manually collected and categorized. Second, these datasets are rewritten using large language models (LLMs) and multimodal LLMs (MLLMs) to generate more complex questions and answers with detailed, step-by-step reasoning. This rewriting process elicits Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning, improving the quality of the instructions. Finally, the same MLLM acts as a judge to filter out low-quality or hallucinated entries. The figure provides examples illustrating how simple question-answer pairs are transformed into more detailed, step-by-step CoT responses in both math and science domains.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of our simple yet scalable visual instruction data rewriting pipeline with three steps: manual data source collection, rewriting using MLLMs/LLMs, and filtering via the same MLLM as a judge. Examples below illustrate transformations in math and science categories, showcasing detailed, step-by-step responses.

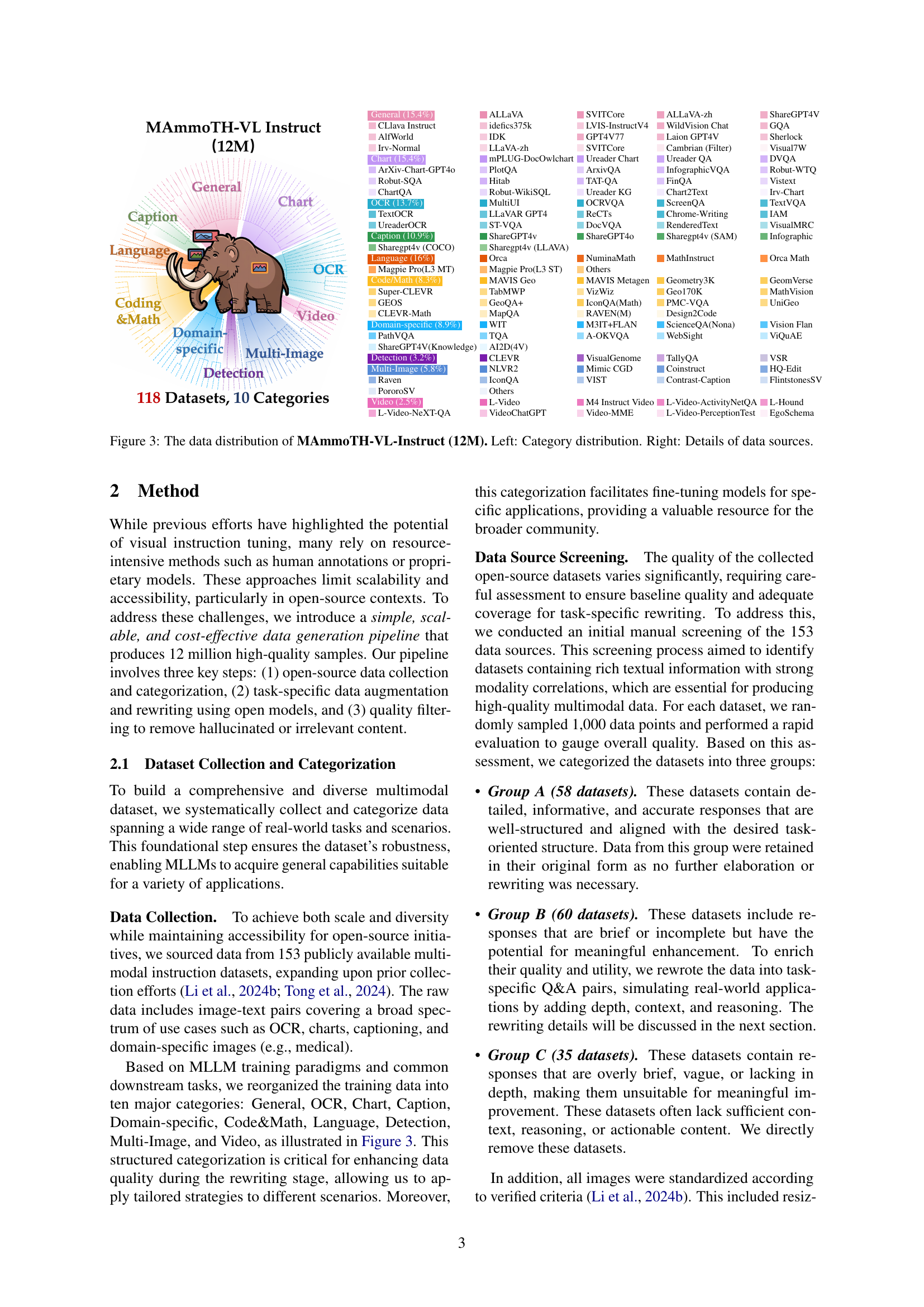

🔼 Figure 3 presents a comprehensive overview of the MAmmoTH-VL-Instruct dataset, which comprises 12 million multimodal instruction-response pairs. The left panel displays the category distribution within the dataset, illustrating the proportion of data points belonging to ten major categories: General, OCR, Chart, Caption, Domain-specific, Code&Math, Language, Detection, Multi-Image, and Video. Each category represents a distinct set of tasks or scenarios covered by the data. The right panel provides detailed information about the individual data sources used to build the MAmmoTH-VL-Instruct dataset, demonstrating the breadth and diversity of the data collection process. The figure clearly highlights both the diversity of the tasks covered and the range of sources that contributed to the construction of this large-scale dataset.

read the caption

Figure 3: The data distribution of MAmmoTH-VL-Instruct (12M). Left: Category distribution. Right: Details of data sources.

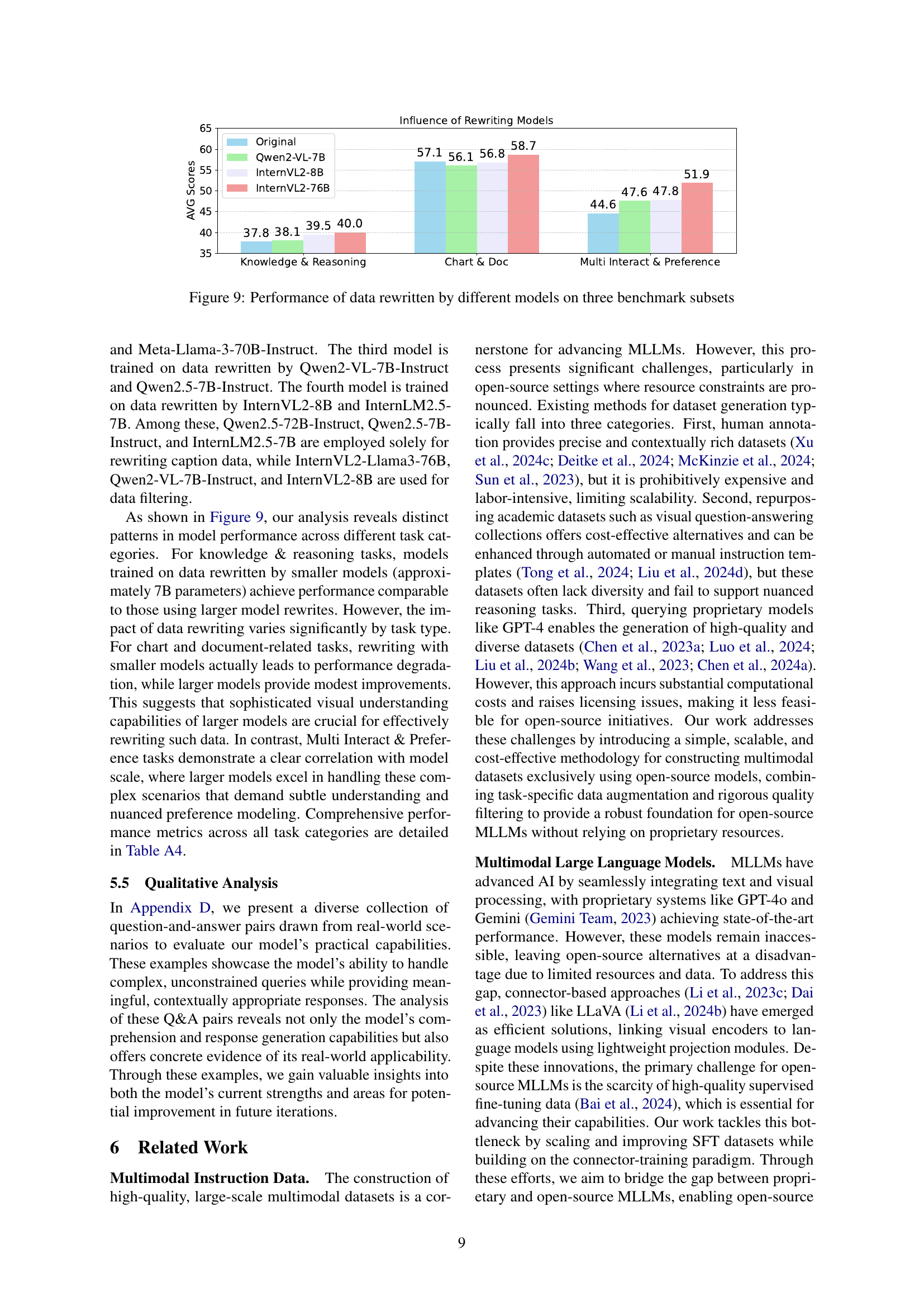

🔼 Figure 4 presents a comparison of the quality of original and rewritten multimodal instruction data. Two key metrics are shown: (1) A model-based evaluation of Content and Relevance scores. This shows that the rewritten data receives higher scores from the language model judge, indicating improved quality. (2) A comparison of Token Length distributions. The rewritten data shows longer token lengths than the original data, demonstrating that the rewriting process has added detailed rationales to the instruction-response pairs.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of original and rewritten data across two metrics: (1) Content and Relevance Scores judged by MLLMs show that rewritten data scores higher, indicating improved quality; (2) Token Length distribution suggests that rewritten data tends to be longer, including more tokens for rationales.

🔼 This t-SNE plot visualizes the difference in topic distribution between the original and rewritten multimodal instruction datasets. The original dataset’s points cluster more tightly, indicating less diversity in the types of instructions and questions. The rewritten dataset shows a wider spread of points, demonstrating a significant increase in the variety of tasks and the complexity of reasoning required to answer them. The expansion beyond the original dataset’s clusters indicates that the rewriting process successfully generated new and diverse instructions that go beyond the scope of existing datasets, improving coverage of complex reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Figure 5: The t-SNE data distribution plot demonstrates how the rewritten data expands beyond the original dataset, increasing topic diversity and enhancing coverage of complex queries and reasoning.

🔼 This figure shows the percentage of data filtered out during the data cleaning process for different categories of data. The filtering aimed to remove low-quality or hallucinated data entries. The results reveal that certain data types, like those involving general question answering (GeneralQA) and mathematical problems (Math), had lower filter rates, indicating higher initial data quality. In contrast, Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and chart-related data (Chart) experienced significantly more extensive filtering, suggesting that these categories contained a higher proportion of problematic data points requiring removal.

read the caption

Figure 6: The filter rates of different data types after filtering, with a lower filtering rate seen in categories like GeneralQA and Math, while OCR and Chart data experience more extensive filtering.

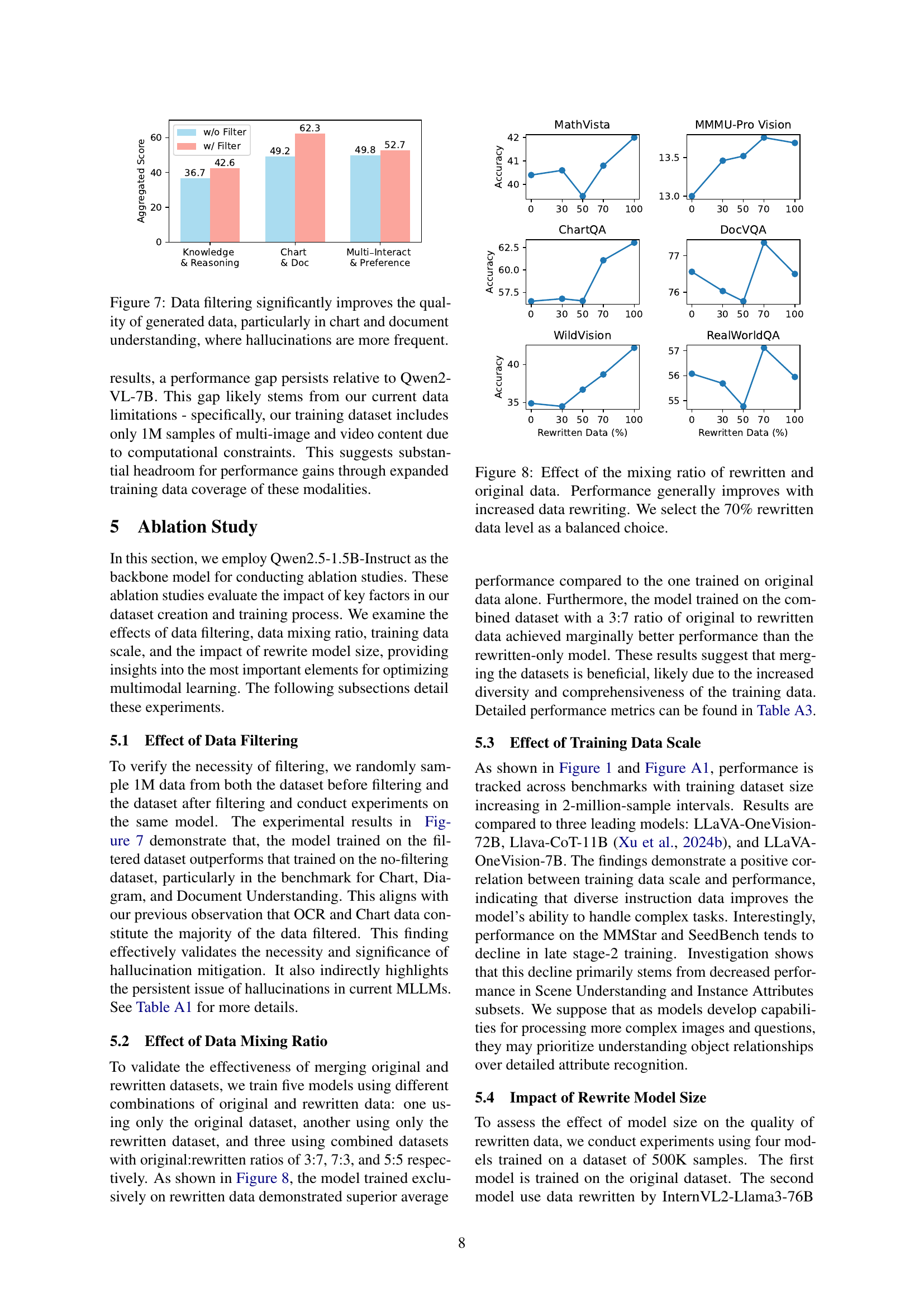

🔼 This figure presents a bar chart comparing the performance of a model trained on filtered and unfiltered data. The chart shows that filtering significantly improves the model’s accuracy, especially in tasks involving chart and document understanding. This improvement is attributed to the reduction of hallucinations, which are errors where the model generates incorrect information that seems plausible but isn’t supported by the data. The results highlight the importance of data filtering in improving the overall quality and reliability of datasets for training multimodal large language models (MLLMs).

read the caption

Figure 7: Data filtering significantly improves the quality of generated data, particularly in chart and document understanding, where hallucinations are more frequent.

More on tables

| Stage-1 | Stage-2 | Stage-3 |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 384 | 384 × {1×1, …} |

| #Tokens | 729 | Max 729×5 |

| Dataset | LCS | Single Image |

| #Samples | 558K | 10M |

| Vision Tower | siglip-so400m-patch14-384 | siglip-so400m-patch14-384 |

| LLM Backbone | Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct | Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct |

| Trainable Model Parameters | Projector: 20.0M | Full Model: 8.0B |

| Batch Size | 512 | 256 |

| Model Max Length | 8192 | 8192 |

| Learning Rate: ψvision | 1×10-3 | 2×10-6 |

| Learning Rate: {θproj,ΦLLM} | 1×10-3 | 1×10-5 |

| Epoch | 1 | 1 |

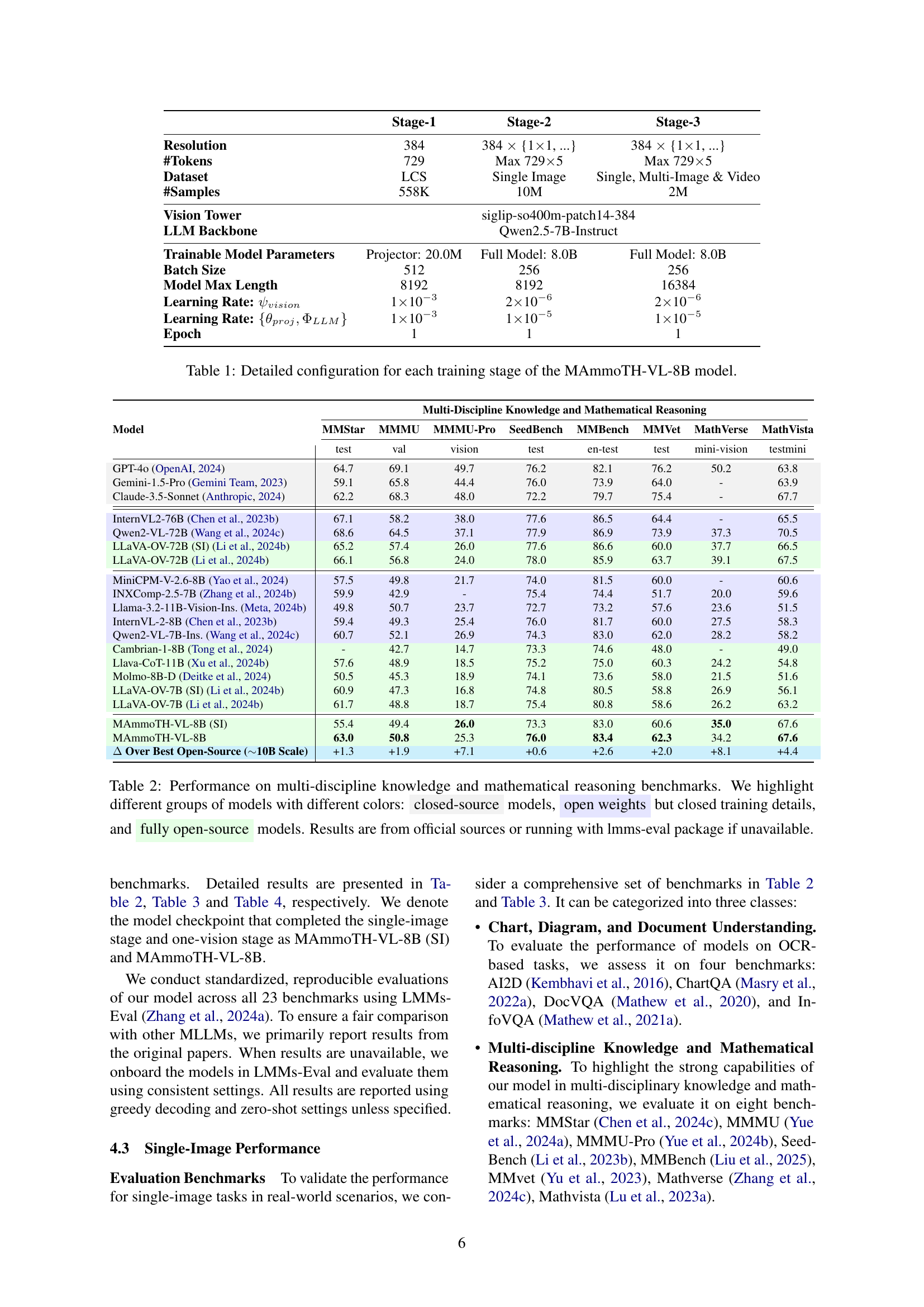

🔼 Table 2 presents the performance comparison of various large language models (LLMs) across a suite of benchmark tests evaluating multi-disciplinary knowledge and mathematical reasoning capabilities. The benchmarks cover diverse tasks requiring complex reasoning and problem-solving skills. Models are categorized into three groups based on their accessibility and transparency: closed-source (proprietary), open-weight (model weights are publicly available but training details are not), and fully open-source (both weights and training details are open). Performance metrics were sourced either from the official publications of the respective LLMs or calculated using the lmms-eval package. This table is crucial for illustrating the significant improvement achieved by the proposed MAmmoTH-VL-8B model, particularly when compared to fully open-source models of a similar size.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance on multi-discipline knowledge and mathematical reasoning benchmarks. We highlight different groups of models with different colors: closed-source models, open weights but closed training details, and fully open-source models. Results are from official sources or running with lmms-eval package if unavailable.

| Model | MMStar | MMMU | MMMU-Pro | SeedBench | MMBench | MMVet | MathVerse | MathVista |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Discipline Knowledge and Mathematical Reasoning | ||||||||

| Model | MMStar | MMMU | MMMU-Pro | SeedBench | MMBench | MMVet | MathVerse | MathVista |

| test | val | vision | test | en-test | test | mini-vision | testmini | |

| GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024) | 64.7 | 69.1 | 49.7 | 76.2 | 82.1 | 76.2 | 50.2 | 63.8 |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro (Gemini Team, 2023) | 59.1 | 65.8 | 44.4 | 76.0 | 73.9 | 64.0 | - | 63.9 |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet (Anthropic, 2024) | 62.2 | 68.3 | 48.0 | 72.2 | 79.7 | 75.4 | - | 67.7 |

| InternVL2-76B (Chen et al., 2023b) | 67.1 | 58.2 | 38.0 | 77.6 | 86.5 | 64.4 | - | 65.5 |

| Qwen2-VL-72B (Wang et al., 2024c) | 68.6 | 64.5 | 37.1 | 77.9 | 86.9 | 73.9 | 37.3 | 70.5 |

| LLaVA-OV-72B (SI) (Li et al., 2024b) | 65.2 | 57.4 | 26.0 | 77.6 | 86.6 | 60.0 | 37.7 | 66.5 |

| LLaVA-OV-72B (Li et al., 2024b) | 66.1 | 56.8 | 24.0 | 78.0 | 85.9 | 63.7 | 39.1 | 67.5 |

| MiniCPM-V-2.6-8B (Yao et al., 2024) | 57.5 | 49.8 | 21.7 | 74.0 | 81.5 | 60.0 | - | 60.6 |

| INXComp-2.5-7B (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 59.9 | 42.9 | - | 75.4 | 74.4 | 51.7 | 20.0 | 59.6 |

| Llama-3.2-11B-Vision-Ins. (Meta, 2024b) | 49.8 | 50.7 | 23.7 | 72.7 | 73.2 | 57.6 | 23.6 | 51.5 |

| InternVL-2-8B (Chen et al., 2023b) | 59.4 | 49.3 | 25.4 | 76.0 | 81.7 | 60.0 | 27.5 | 58.3 |

| Qwen2-VL-7B-Ins. (Wang et al., 2024c) | 60.7 | 52.1 | 26.9 | 74.3 | 83.0 | 62.0 | 28.2 | 58.2 |

| Cambrian-1-8B (Tong et al., 2024) | - | 42.7 | 14.7 | 73.3 | 74.6 | 48.0 | - | 49.0 |

| Llava-CoT-11B (Xu et al., 2024b) | 57.6 | 48.9 | 18.5 | 75.2 | 75.0 | 60.3 | 24.2 | 54.8 |

| Molmo-8B-D (Deitke et al., 2024) | 50.5 | 45.3 | 18.9 | 74.1 | 73.6 | 58.0 | 21.5 | 51.6 |

| LLaVA-OV-7B (SI) (Li et al., 2024b) | 60.9 | 47.3 | 16.8 | 74.8 | 80.5 | 58.8 | 26.9 | 56.1 |

| LLaVA-OV-7B (Li et al., 2024b) | 61.7 | 48.8 | 18.7 | 75.4 | 80.8 | 58.6 | 26.2 | 63.2 |

| MAmmoTH-VL-8B (SI) | 55.4 | 49.4 | 26.0 | 73.3 | 83.0 | 60.6 | 35.0 | 67.6 |

| MAmmoTH-VL-8B | 63.0 | 50.8 | 25.3 | 76.0 | 83.4 | 62.3 | 34.2 | 67.6 |

| Δ Over Best Open-Source (~10B Scale) | +1.3 | +1.9 | +7.1 | +0.6 | +2.6 | +2.0 | +8.1 | +4.4 |

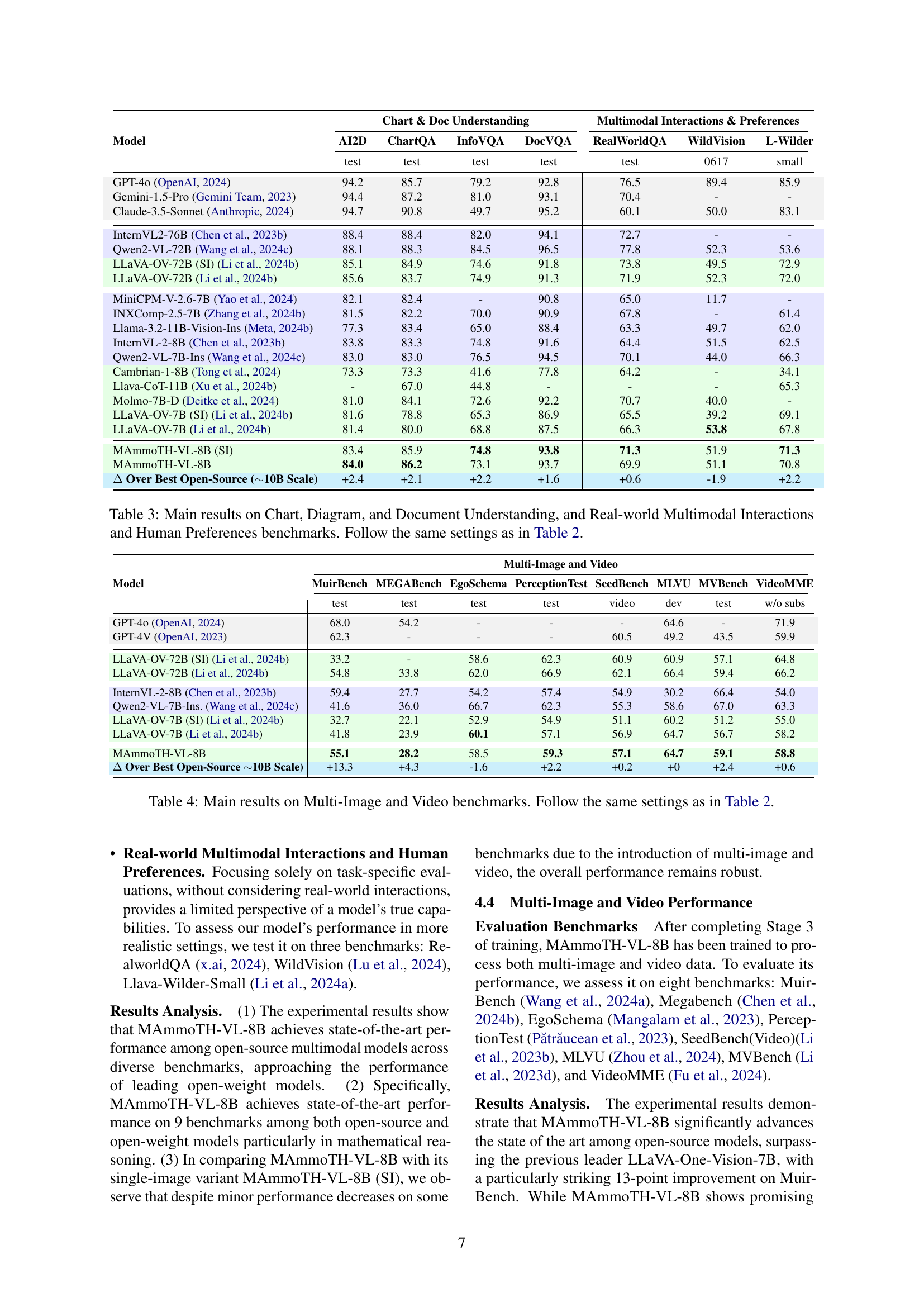

🔼 Table 3 presents the performance of various models on a range of benchmarks focused on Chart & Doc Understanding, and Multimodal Interactions & Preferences. These benchmarks evaluate the models’ abilities to comprehend and reason with charts, diagrams, documents, and real-world multimodal scenarios, measuring their accuracy and overall performance in nuanced interaction tasks. Results are compared using consistent evaluation settings as established in Table 2.

read the caption

Table 3: Main results on Chart, Diagram, and Document Understanding, and Real-world Multimodal Interactions and Human Preferences benchmarks. Follow the same settings as in Table 2.

| Model | AI2D | ChartQA | InfoVQA | DocVQA | RealWorldQA | WildVision | L-Wilder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chart & Doc Understanding | |||||||

| AI2D | ChartQA | InfoVQA | DocVQA | RealWorldQA | WildVision | L-Wilder | |

| test | test | test | test | test | 0617 | small | |

| GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024) | 94.2 | 85.7 | 79.2 | 92.8 | 76.5 | 89.4 | 85.9 |

| Gemini-1.5-Pro (Gemini Team, 2023) | 94.4 | 87.2 | 81.0 | 93.1 | 70.4 | - | - |

| Claude-3.5-Sonnet (Anthropic, 2024) | 94.7 | 90.8 | 49.7 | 95.2 | 60.1 | 50.0 | 83.1 |

| InternVL2-76B (Chen et al., 2023b) | 88.4 | 88.4 | 82.0 | 94.1 | 72.7 | - | - |

| Qwen2-VL-72B (Wang et al., 2024c) | 88.1 | 88.3 | 84.5 | 96.5 | 77.8 | 52.3 | 53.6 |

| LLaVA-OV-72B (SI) (Li et al., 2024b) | 85.1 | 84.9 | 74.6 | 91.8 | 73.8 | 49.5 | 72.9 |

| LLaVA-OV-72B (Li et al., 2024b) | 85.6 | 83.7 | 74.9 | 91.3 | 71.9 | 52.3 | 72.0 |

| MiniCPM-V-2.6-7B (Yao et al., 2024) | 82.1 | 82.4 | - | 90.8 | 65.0 | 11.7 | - |

| INXComp-2.5-7B (Zhang et al., 2024b) | 81.5 | 82.2 | 70.0 | 90.9 | 67.8 | - | 61.4 |

| Llama-3.2-11B-Vision-Ins (Meta, 2024b) | 77.3 | 83.4 | 65.0 | 88.4 | 63.3 | 49.7 | 62.0 |

| InternVL-2-8B (Chen et al., 2023b) | 83.8 | 83.3 | 74.8 | 91.6 | 64.4 | 51.5 | 62.5 |

| Qwen2-VL-7B-Ins (Wang et al., 2024c) | 83.0 | 83.0 | 76.5 | 94.5 | 70.1 | 44.0 | 66.3 |

| Cambrian-1-8B (Tong et al., 2024) | 73.3 | 73.3 | 41.6 | 77.8 | 64.2 | - | 34.1 |

| Llava-CoT-11B (Xu et al., 2024b) | - | 67.0 | 44.8 | - | - | - | 65.3 |

| Molmo-7B-D (Deitke et al., 2024) | 81.0 | 84.1 | 72.6 | 92.2 | 70.7 | 40.0 | - |

| LLaVA-OV-7B (SI) (Li et al., 2024b) | 81.6 | 78.8 | 65.3 | 86.9 | 65.5 | 39.2 | 69.1 |

| LLaVA-OV-7B (Li et al., 2024b) | 81.4 | 80.0 | 68.8 | 87.5 | 66.3 | 53.8 | 67.8 |

| MAmmoTH-VL-8B (SI) | 83.4 | 85.9 | 74.8 | 93.8 | 71.3 | 51.9 | 71.3 |

| MAmmoTH-VL-8B | 84.0 | 86.2 | 73.1 | 93.7 | 69.9 | 51.1 | 70.8 |

| Δ Over Best Open-Source (~10B Scale) | +2.4 | +2.1 | +2.2 | +1.6 | +0.6 | -1.9 | +2.2 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of various models on benchmarks involving multiple images and videos. It compares different models’ performance across several datasets, showing their scores and highlighting the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model in handling more complex, multi-modal data. This allows for a comparison to assess which models are best suited for tasks that demand processing of rich visual information from multiple sources.

read the caption

Table 4: Main results on Multi-Image and Video benchmarks. Follow the same settings as in Table 2.

| Model | MuirBench | MEGABench | EgoSchema | PerceptionTest | SeedBench | MLVU | MVBench | VideoMME |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Image and Video | ||||||||

| Model | MuirBench | MEGABench | EgoSchema | PerceptionTest | SeedBench | MLVU | MVBench | VideoMME |

| test | test | test | test | video | dev | test | w/o subs | |

| GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024) | 68.0 | 54.2 | - | - | - | 64.6 | - | 71.9 |

| GPT-4V (OpenAI, 2023) | 62.3 | - | - | - | 60.5 | 49.2 | 43.5 | 59.9 |

| LLaVA-OV-72B (SI) (Li et al., 2024b) | 33.2 | - | 58.6 | 62.3 | 60.9 | 60.9 | 57.1 | 64.8 |

| LLaVA-OV-72B (Li et al., 2024b) | 54.8 | 33.8 | 62.0 | 66.9 | 62.1 | 66.4 | 59.4 | 66.2 |

| InternVL-2-8B (Chen et al., 2023b) | 59.4 | 27.7 | 54.2 | 57.4 | 54.9 | 30.2 | 66.4 | 54.0 |

| Qwen2-VL-7B-Ins. (Wang et al., 2024c) | 41.6 | 36.0 | 66.7 | 62.3 | 55.3 | 58.6 | 67.0 | 63.3 |

| LLaVA-OV-7B (SI) (Li et al., 2024b) | 32.7 | 22.1 | 52.9 | 54.9 | 51.1 | 60.2 | 51.2 | 55.0 |

| LLaVA-OV-7B (Li et al., 2024b) | 41.8 | 23.9 | 60.1 | 57.1 | 56.9 | 64.7 | 56.7 | 58.2 |

| MAmmoTH-VL-8B | 55.1 | 28.2 | 58.5 | 59.3 | 57.1 | 64.7 | 59.1 | 58.8 |

| Δ Over Best Open-Source ~10B Scale | +13.3 | +4.3 | -1.6 | +2.2 | +0.2 | +0 | +2.4 | +0.6 |

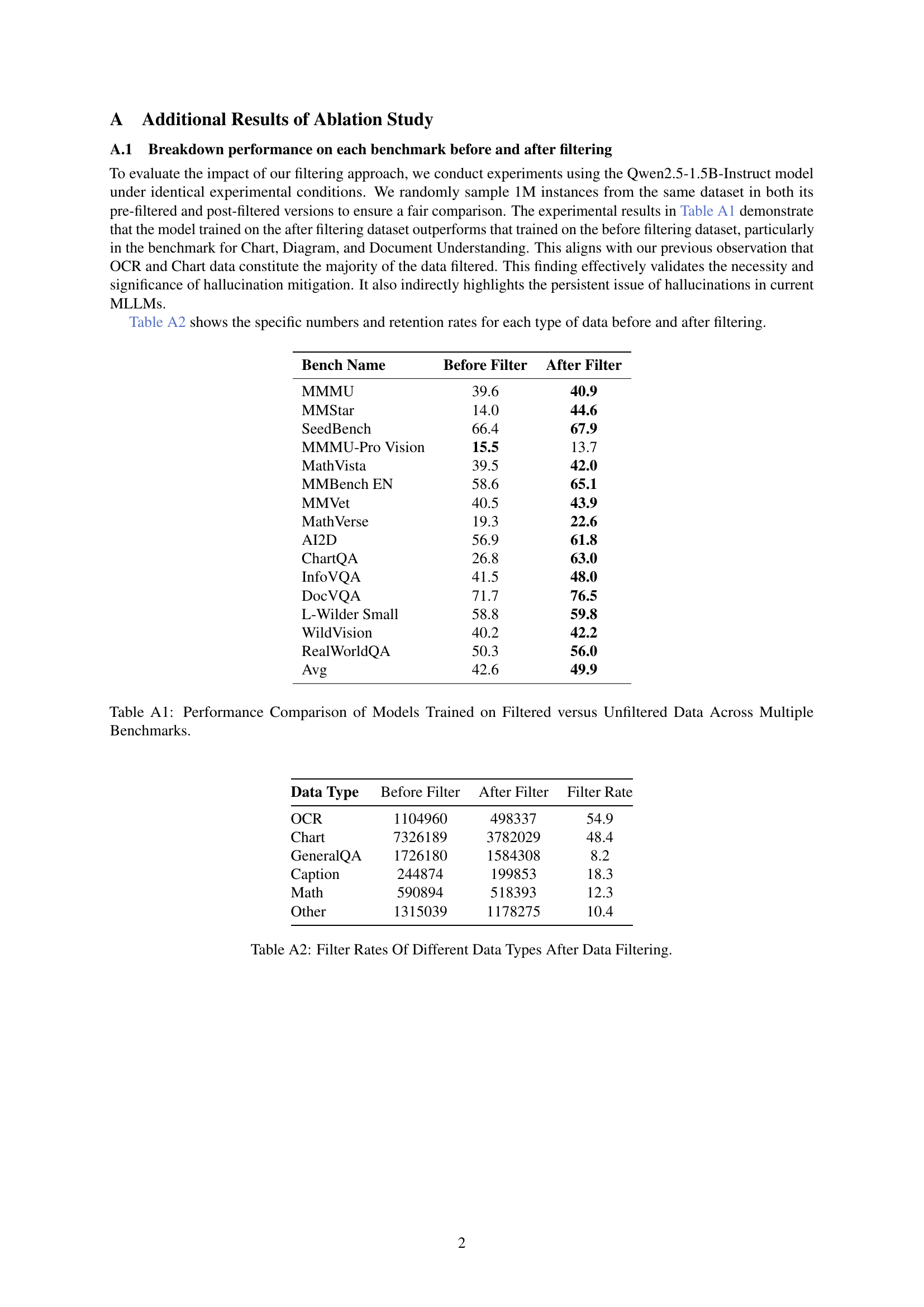

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance achieved by models trained on filtered versus unfiltered datasets across a range of benchmarks. It highlights the impact of the data filtering process on model accuracy, providing a detailed breakdown of performance differences across various evaluation metrics. The benchmarks likely include diverse tasks and datasets, showcasing a comprehensive assessment of the models’ capabilities after training on data subjected to different preprocessing techniques. The table allows for an understanding of the effectiveness of data filtering in improving the overall model performance and the influence of data quality on the outcome.

read the caption

Table A1: Performance Comparison of Models Trained on Filtered versus Unfiltered Data Across Multiple Benchmarks.

| Bench Name | Before Filter | After Filter |

|---|---|---|

| MMMU | 39.6 | 40.9 |

| MMStar | 14.0 | 44.6 |

| SeedBench | 66.4 | 67.9 |

| MMMU-Pro Vision | 15.5 | 13.7 |

| MathVista | 39.5 | 42.0 |

| MMBench EN | 58.6 | 65.1 |

| MMVet | 40.5 | 43.9 |

| MathVerse | 19.3 | 22.6 |

| AI2D | 56.9 | 61.8 |

| ChartQA | 26.8 | 63.0 |

| InfoVQA | 41.5 | 48.0 |

| DocVQA | 71.7 | 76.5 |

| L-Wilder Small | 58.8 | 59.8 |

| WildVision | 40.2 | 42.2 |

| RealWorldQA | 50.3 | 56.0 |

| Avg | 42.6 | 49.9 |

🔼 This table presents the percentage of data retained after filtering for different data types within the MAmmoTH-VL dataset. The filtering process aimed to remove low-quality or hallucinated data, focusing on data sets related to Charts, Diagrams, and Documents. The filter rate represents the proportion of data deemed acceptable and retained for model training after this quality-control process. The data types are categorized and analyzed individually to show where the filtering process had a greater effect, indicating potential areas for future data improvements or improvements in the model’s ability to filter such data.

read the caption

Table A2: Filter Rates Of Different Data Types After Data Filtering.

| Data Type | Before Filter | After Filter | Filter Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCR | 1104960 | 498337 | 54.9 |

| Chart | 7326189 | 3782029 | 48.4 |

| GeneralQA | 1726180 | 1584308 | 8.2 |

| Caption | 244874 | 199853 | 18.3 |

| Math | 590894 | 518393 | 12.3 |

| Other | 1315039 | 1178275 | 10.4 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of models trained on datasets with varying ratios of original and rewritten data. It shows how the model’s performance changes across multiple benchmarks as the proportion of rewritten data in the training set increases. The benchmarks used are likely for a multimodal large language model (MLLM). The different mix ratios show how the model performs using only original data, only rewritten data, and combinations of both.

read the caption

Table A3: Benchmark Performance Of Models Trained On Data With Different Mix Ratios.

| Bench Name | Rewrite | Original | Mix 3:7 | Mix 7:3 | Mix 5:5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMMU | 40.9 | 41.9 | 41.5 | 41.3 | 41.7 |

| MMStar | 44.6 | 43.3 | 43.4 | 42.3 | 43.7 |

| SeedBench | 67.9 | 69.9 | 68.7 | 69.3 | 68.9 |

| MMMU-Pro Vision | 13.7 | 13.0 | 13.8 | 13.5 | 13.5 |

| MathVista | 42.0 | 40.4 | 41.8 | 40.6 | 39.5 |

| MMBench EN | 65.1 | 67.8 | 66.1 | 67.9 | 66.4 |

| MMVet | 43.9 | 37.3 | 45.5 | 40.7 | 38.9 |

| MathVerse | 22.6 | 19.8 | 21.4 | 21.0 | 20.4 |

| AI2D | 61.8 | 63.1 | 62.9 | 62.5 | 62.8 |

| ChartQA | 63.1 | 56.5 | 61.1 | 56.8 | 56.6 |

| InfoVQA | 48.0 | 47.3 | 49.0 | 45.7 | 45.6 |

| DocVQA | 76.5 | 76.6 | 77.4 | 76.0 | 75.7 |

| L-Wilder Small | 59.8 | 56.4 | 60.9 | 56.8 | 57.4 |

| WildVision | 42.2 | 34.9 | 38.7 | 34.5 | 36.7 |

| RealworldQA | 56.0 | 56.1 | 57.1 | 55.7 | 54.8 |

| Avg | 49.9 | 48.3 | 50.0 | 48.3 | 48.2 |

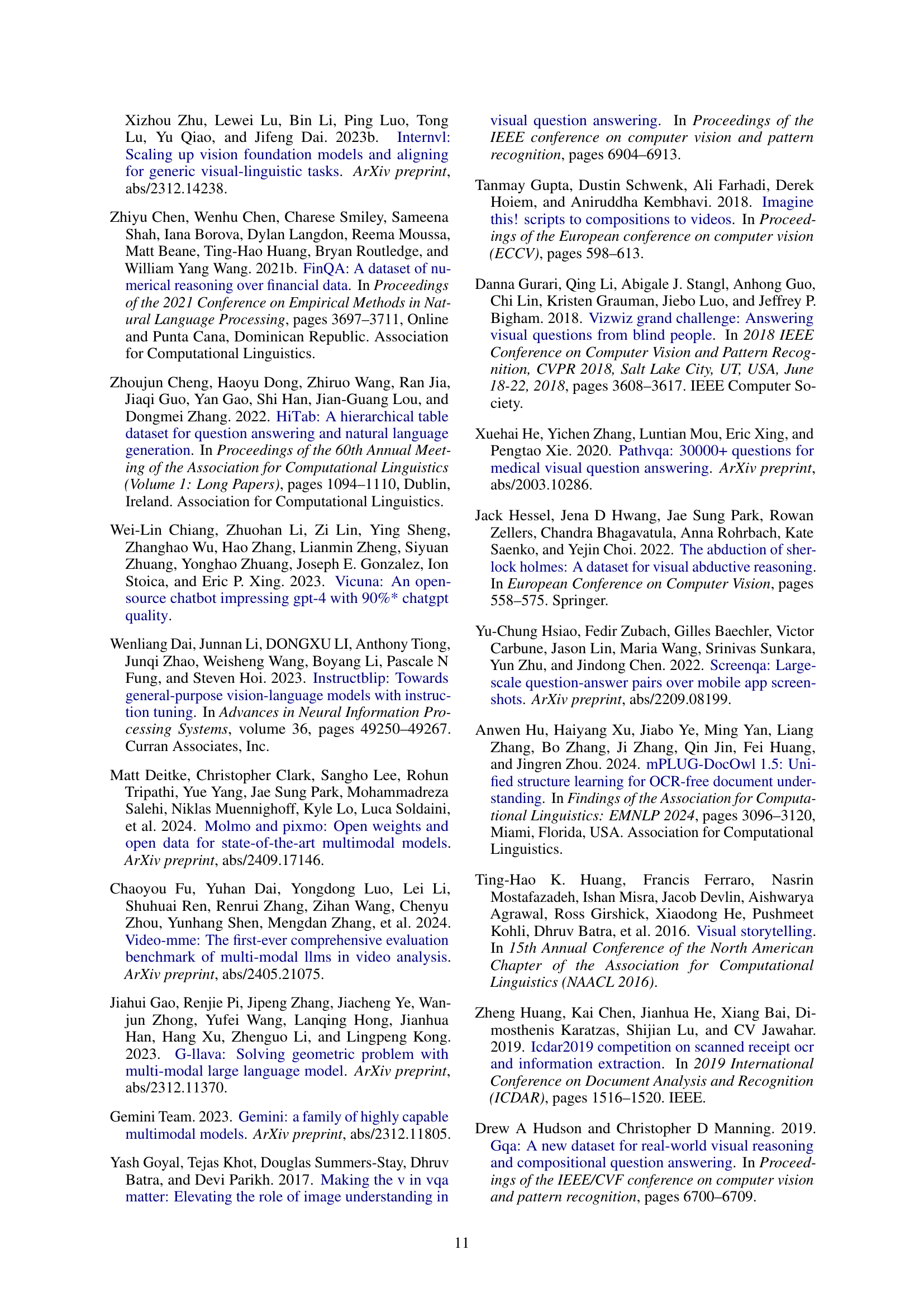

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance achieved by various models trained on datasets created using different rewriting techniques. The models were evaluated across multiple benchmarks, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of how rewriting methods impact performance. Each model’s performance is presented as a score for each benchmark, allowing for a direct comparison across different rewriting approaches.

read the caption

Table A4: Performance On Different Benchmarks Of Models Trained On Data Rewritten By Different Models

| Bench Name | Original | Rewrite (Qwen2-VL-7B) | Rewrite (InternVL2-8B) | Rewrite (InternVL2-76B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMMU | 40.4 | 40.6 | 40.9 | 40.78 |

| MMStar | 40.9 | 41.7 | 41.7 | 37.9 |

| SeedBench | 50.6 | 52.1 | 65.0 | 67.0 |

| MMMU-Pro Vision | 12.3 | 12.9 | 12.9 | 15.3 |

| MathVista | 36.4 | 38.8 | 37.4 | 39.0 |

| MMBench EN | 65.8 | 59.1 | 60.1 | 58.3 |

| MMVet | 38.6 | 38.1 | 38.6 | 41.1 |

| MathVerse | 17.6 | 21.6 | 19.8 | 20.6 |

| AI2D | 61.8 | 62.3 | 61.7 | 59.6 |

| ChartQA | 49.4 | 48.1 | 50.6 | 58.7 |

| InfoVQA | 43.8 | 43.1 | 43.7 | 44.3 |

| DocVQA | 73.4 | 70.8 | 71.3 | 72.2 |

| L-Wilder Small | 44.5 | 55.7 | 55.7 | 60.5 |

| WildVision | 32.7 | 32.0 | 30.8 | 41.7 |

| RealWorldQA | 56.5 | 55.1 | 56.8 | 53.5 |

| Avg | 46.8 | 47.3 | 48.4 | 50.0 |

🔼 This table presents the inter-rater reliability scores (Cohen’s Kappa) comparing the model’s filtering decisions against three human evaluators. The values show how consistently the model’s automated filtering process agrees with human judgment in identifying high-quality data entries.

read the caption

Table A5: Kappa Value Between Any Two.

| \ | Model | Evaluator1 | Evaluator2 | Evaluator3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | - | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.63 |

| Evaluator1 | 0.73 | - | 0.70 | 0.42 |

| Evaluator2 | 0.70 | 0.70 | - | 0.53 |

| Evaluator3 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 0.53 | - |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the quality of original and rewritten multimodal instruction data. Specifically, it shows the average content and relevance scores for each dataset before and after the rewriting process. Higher scores indicate better quality data, implying richer information content and stronger alignment between the visual and textual components. The scores were obtained using an MLLM (large language model) as a judge.

read the caption

Table A6: Comparison of Original and Rewrite Average Content and Relevance Scores

Full paper#