↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Many existing methods in language-guided visual navigation focus on specific tasks, limiting their generalizability. This paper tackles this issue by proposing a unified framework. A key challenge is that diverse tasks have conflicting learning objectives, hindering simple data-mixing training approaches.

To solve this, the researchers developed a novel State-Adaptive Mixture of Experts (SAME) model. SAME enables agents to dynamically adapt to different instruction granularities and observation complexities. The model achieves state-of-the-art or comparable performance across seven different navigation tasks, demonstrating its versatility and effectiveness. This unified approach allows for better knowledge sharing across tasks and improved generalization capabilities compared to using multiple task-specific agents.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the limitations of existing methods in language-guided visual navigation by proposing a novel, unified approach. It introduces SAME, a state-adaptive mixture of experts model, enabling agents to handle diverse navigation tasks with improved performance. This work is relevant to current trends in multi-task learning and embodied AI, opening new avenues for developing more versatile and robust AI agents capable of operating in complex, real-world environments.

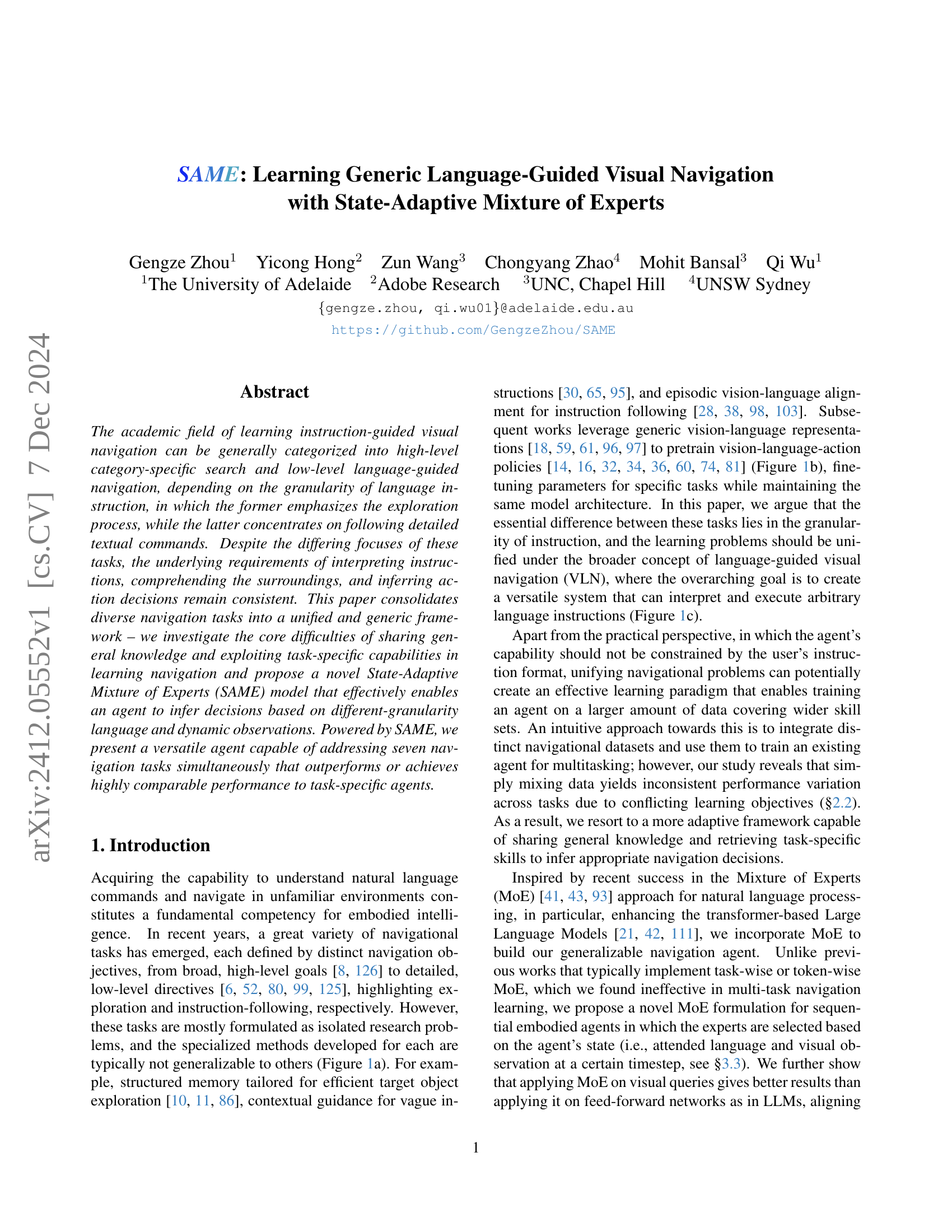

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the three different approaches to language-guided visual navigation tasks. (a) shows the traditional approach of using separate models for each task, each tailored to the specificity of its instructions. This method is not efficient or easily scalable. (b) displays a similar approach of using the same model but with different parameters for each task. This approach is better, but still not as flexible or versatile. (c) shows the proposed method by the authors, a unified model capable of handling diverse instructions with varying levels of granularity (high-level, coarse-grained, and fine-grained), achieving a more versatile and generalizable navigation system.

read the caption

Figure 1: We consolidate diverse navigation tasks into a unified language-guided navigation framework sorted by language granularity. Previous approaches utilize task-specific designs tailored to address particular types of language instructions, as shown in (a) and (b). In contrast, we propose a versatile system that can interpret and execute arbitrary language instructions as shown in (c).

| Training Data | R2R (Val Unseen) | REVERIE (Val Unseen) | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2R* | REVERIE* | MP3D* | TL | NE ↓ |

| ✓ | 14.33 | 3.82 | ||

| ✓ | 17.55 | 6.22 | ||

| ✓ | 20.76 | 8.55 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 14.03 | 4.01 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 19.17 | 7.13 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14.21 | 4.10 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of the DuET model [16] when trained on different combinations of datasets. It shows the impact of data diversity on the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. The results are presented in terms of Trajectory Length (TL), Navigation Error (NE), Success Rate (SR), and SPL, which are common evaluation metrics for visual navigation tasks. The asterisk (*) indicates that Habitat-rendered images were used in the training process. The gray numbers represent the zero-shot performance of the model on held-out datasets, which were not used during training, highlighting the model’s ability to generalize. Different training data combinations were tested to understand how data mixing affects performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of single-run performance with a different mixture of training data for DuET [16]. ∗*∗ indicates utilizing Habitat-rendered images. Numbers in gray indicated zero-shot inference results on held-out datasets.

In-depth insights#

VLN Task Unification#

The concept of “VLN Task Unification” in the research paper centers on the idea of consolidating diverse visual navigation tasks under a single, unified framework. This approach challenges the traditional method of developing task-specific models for various navigation scenarios (e.g., high-level object search, precise low-level instruction following). The core argument is that these tasks share underlying requirements like instruction interpretation and environment understanding, despite differences in instruction granularity. The paper advocates for a generalizable agent capable of addressing multiple task types simultaneously, promoting better data efficiency and potentially improved generalization compared to models trained on individual, isolated tasks. This unification is not merely a methodological change, but a fundamental shift towards building more robust and adaptable AI agents. A key component of this unification is likely to be a model architecture that effectively utilizes both shared knowledge across tasks and task-specific capabilities, perhaps using a modular design or a similar approach to leverage the strength of each.

SAME Model Details#

A hypothetical section titled ‘SAME Model Details’ would delve into the architectural specifics of the State-Adaptive Mixture of Experts (SAME) model. This would likely include a detailed explanation of the expert networks, their individual specializations in handling different aspects of language-guided navigation (e.g., exploration vs. precise following of instructions), and the gating mechanism that dynamically selects which experts are active at each step based on the agent’s current state. Crucially, it would describe how the multimodal input (visual observations and language instructions) is processed and utilized for expert selection, highlighting the model’s state-adaptive nature. The description would also address any novel training strategies, loss functions, or optimizations employed to ensure effective knowledge sharing and prevent conflicts between the experts. Finally, discussion of the model’s modularity, flexibility, and generalizability across diverse navigation tasks would be crucial, demonstrating its capabilities and advantages over task-specific approaches.

Multi-task Learning#

Multi-task learning (MTL) in the context of vision-language navigation (VLN) presents a compelling approach to improve model efficiency and generalization. By training a single model on multiple VLN tasks simultaneously, MTL aims to leverage shared knowledge and transfer skills across different tasks, potentially outperforming single-task models. However, the paper highlights significant challenges, such as conflicting learning objectives arising from the varying levels of language granularity and task-specific nuances across datasets. The State-Adaptive Mixture of Experts (SAME) architecture proposed is specifically designed to overcome these challenges. SAME dynamically adapts to the task’s requirements using a routing mechanism, effectively enabling the model to retrieve task-specific capabilities while leveraging the shared knowledge. This state-adaptive mechanism is a crucial innovation that distinguishes SAME from traditional MTL approaches, which often struggle with the inherent conflicts when naively merging datasets. The success of SAME underscores the importance of carefully considering the architecture’s design when applying MTL to VLN, emphasizing the need for a more flexible and adaptive approach to address the diverse nature of the tasks.

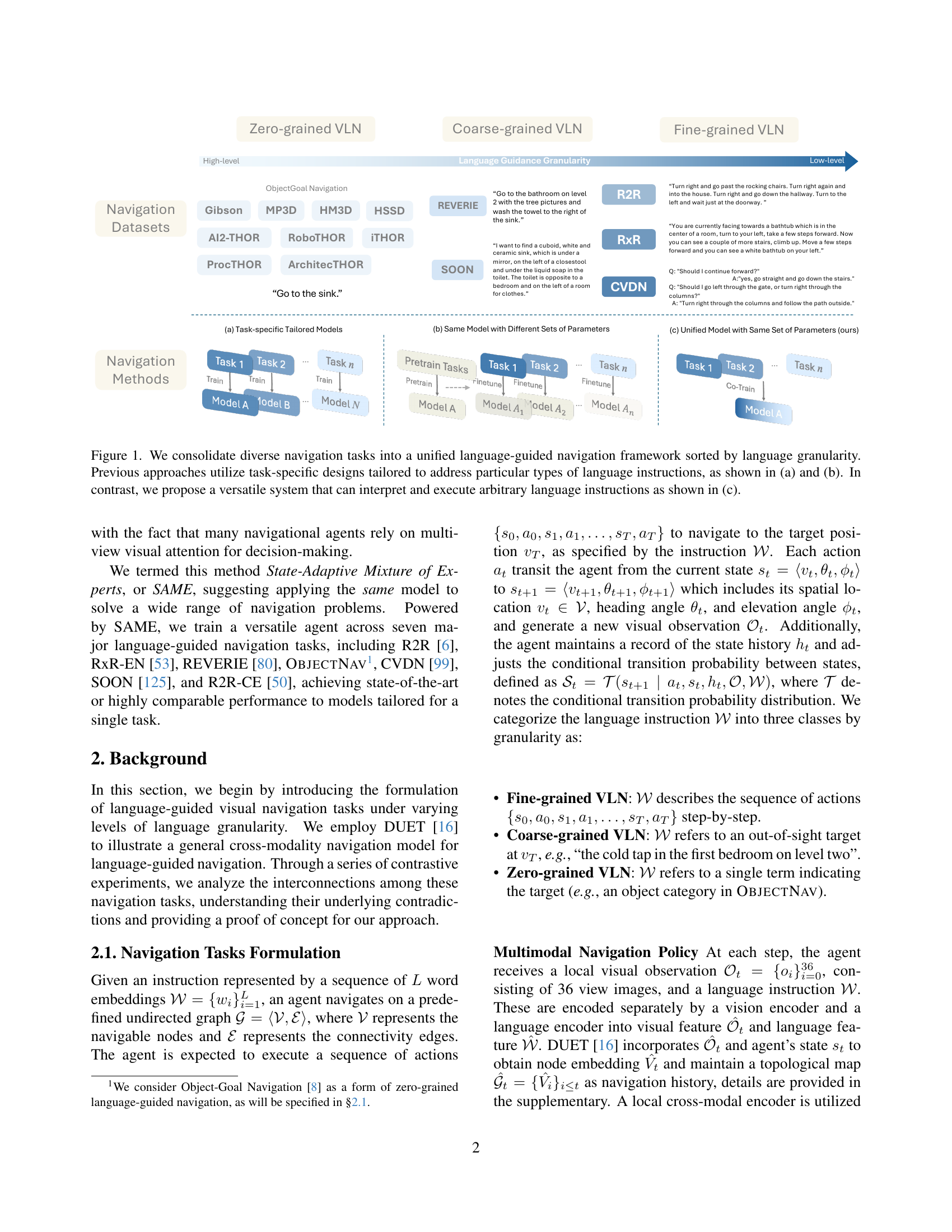

MoE Routing Strategies#

The core of the proposed SAME model lies in its innovative approach to Mixture of Experts (MoE) routing. Instead of the typical token-wise or task-wise routing, SAME employs a state-adaptive strategy. This means expert selection is dynamically determined based on the agent’s current state, encompassing both visual observations and the processed language instruction. This approach is particularly crucial for handling the diverse granularity of language instructions across various navigation tasks. By considering both the low-level details of specific commands and the high-level goals implicit in more ambiguous directives, SAME’s routing mechanism allows for a more flexible and contextually appropriate response. The multimodality of the input features used for routing further enhances the system’s ability to adapt to dynamic environmental changes. The results demonstrate that this novel state-adaptive strategy outperforms both task-wise and token-wise MoE methods, showcasing the importance of considering the dynamic interplay between language and observation when selecting specialized expert networks for navigation.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending SAME to handle more complex instructions involving multiple steps, conditional actions, and nuanced language is a key area. Investigating the impact of different MoE architectures and routing mechanisms on performance would provide valuable insights into optimizing the model’s efficiency. Analyzing the robustness of SAME across a wider variety of environments with diverse visual and linguistic characteristics would enhance its generalizability. Furthermore, exploring the potential for transfer learning, where knowledge gained from one navigation task is readily applied to others, deserves investigation. Finally, integrating external knowledge sources, such as maps or object databases, could significantly augment the agent’s capabilities and improve its decision-making process in complex scenarios. Evaluating SAME’s efficiency and scalability with significantly larger datasets and more intricate environments is also important. The incorporation of uncertainty estimation, addressing challenges arising from noisy or ambiguous data, represents another crucial area. The research could also focus on developing more efficient training strategies for the multi-task setting of SAME, potentially using curriculum learning or meta-learning to improve learning speed and generalization.

More visual insights#

More on tables

| Routing Condition | R2R (Val Unseen) | REVERIE (Val Unseen) | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | NE↓ | SR↑ | SPL↑ | TL | NE↓ | SR↑ | SPL↑ | TL | NE↓ | SR↑ | SPL↑ | |

| w/o MoE | 11.76 | 2.98 | 73.09 | 65.79 | 13.17 | 5.90 | 40.39 | 35.40 | 16.13 | 3.16 | 72.31 | 42.72 |

| Token-wised MoE [93] | ||||||||||||

| Token Embedding | 13.28 | 2.98 | 73.99 | 64.81 | 16.78 | 5.60 | 43.45 | 35.40 | 15.69 | 3.04 | 74.38 | 44.97 |

| Task-wised MoE | ||||||||||||

| Task Embedding | 12.98 | 3.13 | 72.84 | 64.81 | 14.90 | 5.71 | 43.71 | 36.58 | 14.96 | 3.17 | 71.13 | 43.88 |

Text [CLS] | 14.45 | 2.92 | 74.67 | 64.12 | 19.22 | 5.46 | 45.50 | 36.56 | 15.63 | 3.11 | 71.32 | 42.75 |

| w/ Task Embedding | 15.80 | 2.95 | 73.61 | 62.80 | 21.50 | 5.44 | 43.85 | 34.10 | 18.26 | 3.00 | 72.40 | 39.98 |

| State-Adaptive MoE (ours) | ||||||||||||

| SAME | 13.51 | 2.90 | 73.69 | 64.92 | 16.32 | 5.38 | 45.67 | 37.95 | 15.60 | 3.10 | 71.43 | 43.39 |

| w/ Task Embedding | 14.00 | 2.89 | 74.50 | 64.66 | 17.65 | 5.66 | 42.32 | 33.61 | 17.20 | 2.86 | 73.39 | 42.07 |

| w/o Pretrain | 14.71 | 4.66 | 59.05 | 49.02 | 14.19 | 6.26 | 38.43 | 32.40 | 19.93 | 3.08 | 70.94 | 38.48 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of a single run of the model with different Mixture of Experts (MoE) routing methods. The performance is evaluated across three different visual navigation tasks: R2R (fine-grained instructions), REVERIE (coarse-grained instructions), and ObjectNav-MP3D (zero-grained instructions). The metrics used for comparison include Trajectory Length (TL), Navigation Error (NE), Success Rate (SR), and Success rate penalized by Path Length (SPL). Different MoE routing strategies are compared, such as no MoE, token-wise MoE, task-wise MoE and the proposed State-Adaptive MoE (SAME), with and without task embedding. This allows for assessment of how different routing mechanisms impact performance across tasks with varying levels of language instruction detail.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of single-run performance with different MoE routing conditions on R2R, REVERIE, and ObjectNav-MP3D.

| MoE Experts Position | R2R (Val Unseen) TL | R2R (Val Unseen) NE↓ | R2R (Val Unseen) SR↑ | R2R (Val Unseen) SPL↑ | REVERIE (Val Unseen) TL | REVERIE (Val Unseen) NE↓ | REVERIE (Val Unseen) SR↑ | REVERIE (Val Unseen) SPL↑ | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) TL | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) NE↓ | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) SR↑ | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) SPL↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Forward | 13.18 | 3.08 | 73.44 | 64.86 | 16.02 | 5.62 | 42.77 | 35.28 | 16.02 | 3.09 | 71.37 | 42.24 |

| Visual Query | 13.51 | 2.90 | 73.69 | 64.92 | 16.32 | 5.38 | 45.67 | 37.95 | 15.60 | 3.10 | 71.43 | 43.39 |

| Textual Key & Value | 15.58 | 2.82 | 75.35 | 63.85 | 20.30 | 5.36 | 45.61 | 34.75 | 17.57 | 3.10 | 72.17 | 42.67 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of a model using different Mixture of Experts (MoE) configurations. The model’s performance is evaluated on three different visual navigation tasks: R2R (fine-grained instructions), REVERIE (coarse-grained instructions), and ObjectNav-MP3D (zero-grained instructions). The different MoE configurations vary in where the MoE is applied within the model architecture (feed-forward network, visual query, textual key and value). The metrics used to evaluate performance are Trajectory Length (TL), Navigation Error (NE), Success Rate (SR), and SPL.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of single-run performance with different MoE experts’ positions on R2R, REVERIE, and ObjectNav-MP3D.

| Methods | CVDN | RxR-EN | R2R | SOON | REVERIE | ObjectNav-MP3D | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Val | Test | Val unseen | Val unseen | Val unseen | Test unseen | Val unseen | Test unseen | Val unseen | Test unseen | Val | Test | |||||||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| GP ↑ | GP ↑ | SR ↑ | nDTW ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ | |||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Separate Model for Each Task: | ||||||||||||||||||

| SF [28] | - | - | - | - | 36 | - | 35 | 28 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RCM [103] | - | - | - | - | 43 | - | 43 | 38 | - | - | - | - | 9.3 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 6.7 | - | - |

| EnvDrop [98] | - | - | - | - | 52 | 48 | 51 | 47 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PREVALENT [34] | 3.15 | 2.44 | - | - | 58 | 53 | 54 | 51 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| VLN ↻BERT [36] | - | - | - | - | 63 | 57 | 63 | 57 | - | - | - | - | 25.5 | 21.1 | 24.6 | 19.5 | - | - |

| HAMT [15] | 5.13 | 5.58 | 56.4 | 63.0 | 66 | 61 | 65 | 60 | - | - | - | - | 33.0 | 30.2 | 30.4 | 26.7 | - | - |

| HOP+ [81] | - | - | - | - | 67 | 61 | 66 | 60 | - | - | - | - | 36.1 | 31.1 | 33.8 | 28.2 | - | - |

| DUET [16] | - | - | - | - | 72 | 60 | 69 | 59 | 36.3 | 22.6 | 33.4 | 21.4 | 47.0 | 33.7 | 52.5 | 36.1 | - | - |

| AutoVLN [17] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 41.0 | 30.7 | 40.4 | 27.9 | 55.9 | 40.9 | 55.2 | 38.9 | - | - |

| BEVBert [3] | - | - | 66.7 | 69.6 | 75 | 64 | 73 | 62 | - | - | - | - | 51.8 | 36.4 | 52.8 | 36.4 | - | - |

| GridMM [107] | - | - | - | - | 75 | 64 | 73 | 62 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| VER [67] | - | - | - | 76 | 65 | 76 | 66 | - | - | - | - | 56.0 | 39.7 | 56.8 | 38.8 | - | - | |

| GOAT [101] | - | - | 68.2 | 66.8 | 78 | 68 | 75 | 65 | 40.4 | 28.1 | 40.5 | 25.2 | 53.4 | 36.7 | 57.7 | 40.5 | - | - |

| ScaleVLN [106] | 6.12 | 6.97 | - | - | 79 | 70 | 77 | 68 | - | - | - | - | 57.0 | 41.8 | 56.1 | 39.5 | - | - |

| Unified Model for All Tasks: | ||||||||||||||||||

| MT-RCM [104] | 4.65 | 3.91 | - | - | 47 | 41 | 45 | 40 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| NaviLLM [121] | 6.16 | 7.90 | - | - | 67 | 59 | 68 | 60 | 38.3 | 29.2 | 35.0 | 26.3 | 42.2 | 35.7 | 39.8 | 32.3 | - | - |

| ScaleVLN† | 5.93 | - | 46.7 | 49.7 | 76 | 67 | - | - | 33.2 | 25.4 | - | - | 41.9 | 34.4 | - | - | 72.3 | 43.4 |

| SAME (ours) | 6.94 | 7.07 | 50.5 | 51.2 | 76 | 66 | 74 | 64 | 36.1 | 25.4 | 38.2 | 27.1 | 46.4 | 36.1 | 48.6 | 37.1 | 76.3 | 42.7 |

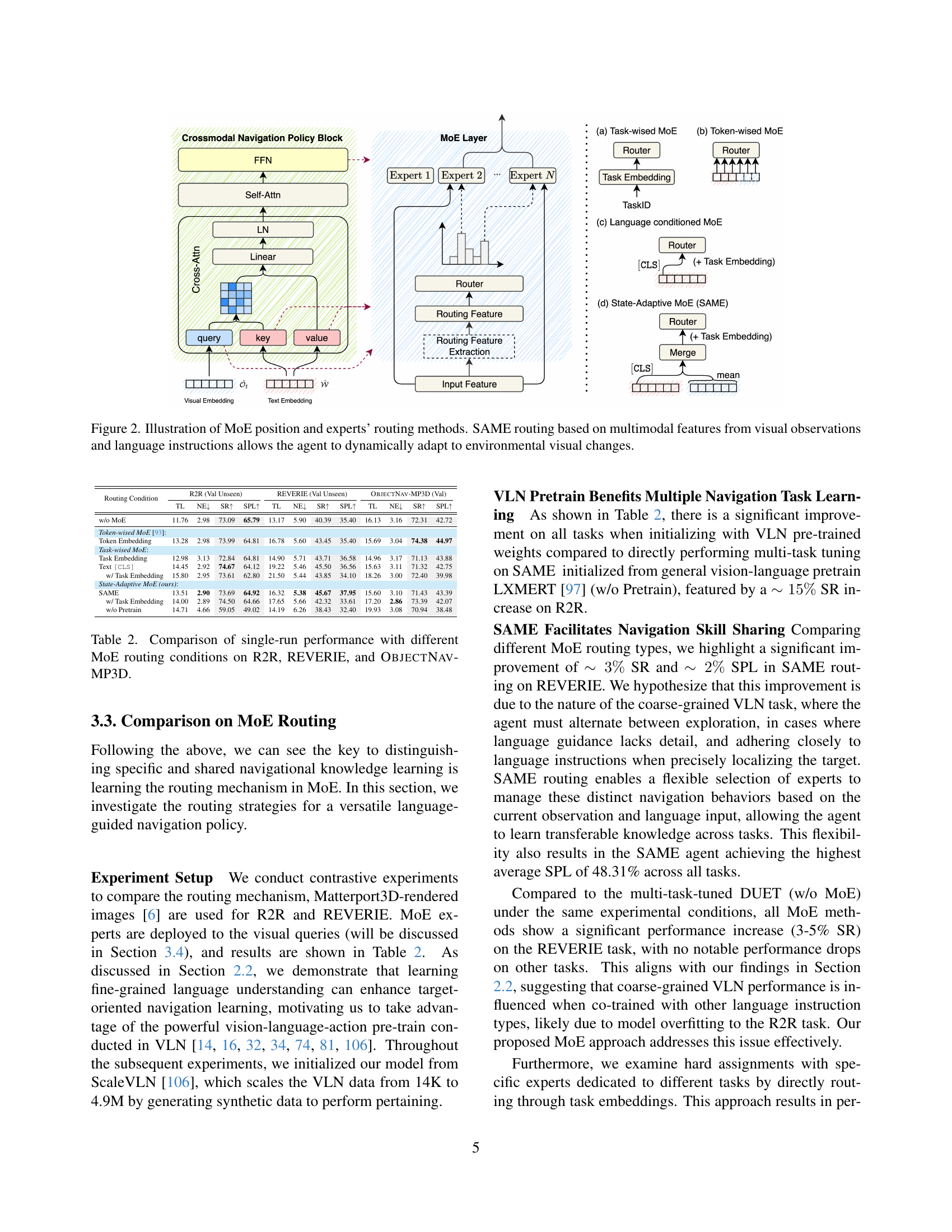

🔼 Table 4 presents a comparison of different methods’ performance on various visual navigation tasks within a discrete environment. The tasks vary in terms of the level of detail in the language instructions, ranging from fine-grained (requiring precise step-by-step instructions) to coarse-grained (providing higher-level guidance) to zero-grained (simply specifying an object goal). The table shows results for both models designed for specific tasks and a single model trained for all tasks. The performance metrics used include success rate, trajectory length, navigation error, and SPL (Success weighted by Path Length), and nDTW (normalized Dynamic Time Warping). The table highlights the performance of the proposed SAME model compared to state-of-the-art methods. Note that some models are only evaluated on a subset of the tasks, and some methods (ObjectNav-MP3D) designed for a continuous environment are not directly comparable to those evaluated in this discrete environment.

read the caption

Table 4: Agents performance across all tasks in the discrete environment [6]. ††\dagger† indicates our implementation of multi-task tuning. Note that existing methods tailored for ObjectNav-MP3D are proposed in continuous environments, which will be evaluated in Table 5 below.

| Methods | R2R-CE (Val unseen) NE ↓ | R2R-CE (Val unseen) SR ↑ | R2R-CE (Val unseen) SPL ↑ | MP3D (Val) SR ↑ | MP3D (Val) SPL ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaVid [117] | 5.47 | 37 | 36 | - | - |

| ScaleVLN [106] | 4.80 | 55 | 51 | - | - |

| ETPNav [4] | 4.71 | 57 | 49 | - | - |

| BEVBert [3] | 4.57 | 59 | 50 | - | - |

| SemExp [10] | - | - | - | 28 | 11 |

| PONI [86] | - | - | - | 32 | 12 |

| Habitat-Web [87] | - | - | - | 35 | 10 |

| SAME (ours) | 5.31 | 47 | 38 | 43 | 21 |

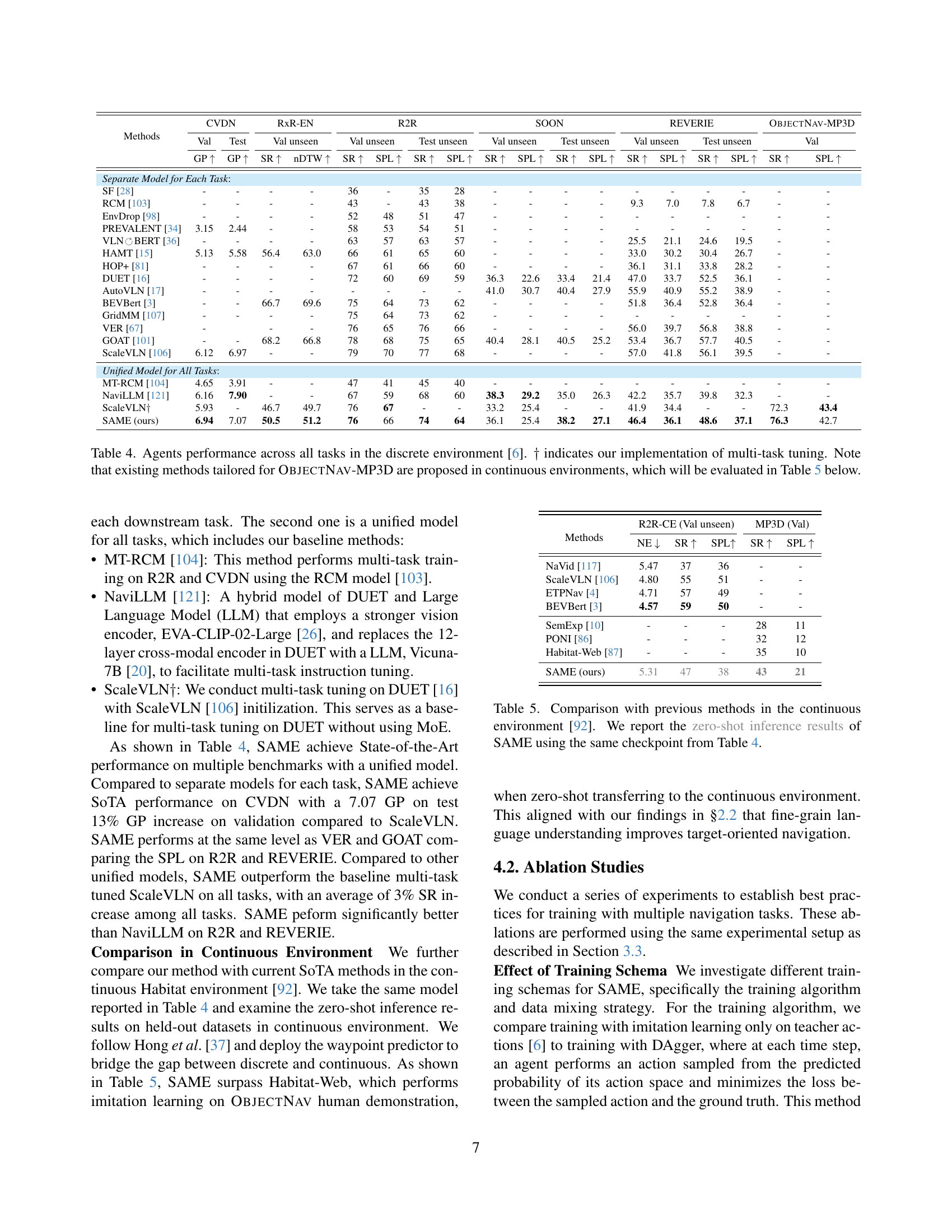

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed SAME model with state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on continuous environment datasets for vision-language navigation. It specifically focuses on the zero-shot transfer performance. The SAME model’s results are taken from the same checkpoint used in Table 4 (discrete environment results). The table shows that even without further training on the continuous datasets, SAME performs competitively with or better than other existing methods.

read the caption

Table 5: Comparison with previous methods in the continuous environment [92]. We report the zero-shot inference results of SAME using the same checkpoint from Table 4.

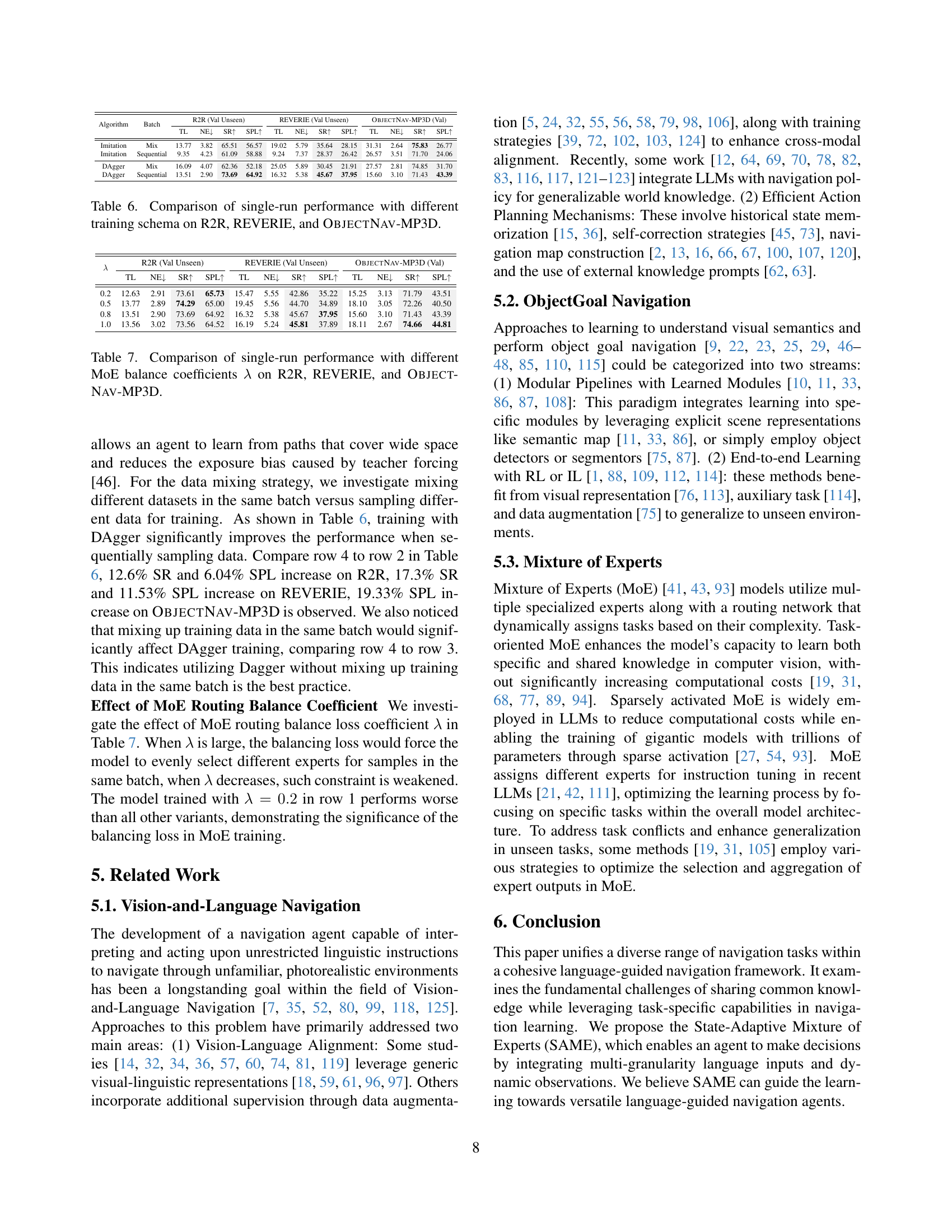

| Algorithm | Batch | R2R (Val Unseen) TL | R2R (Val Unseen) NE↓ | R2R (Val Unseen) SR↑ | R2R (Val Unseen) SPL↑ | REVERIE (Val Unseen) TL | REVERIE (Val Unseen) NE↓ | REVERIE (Val Unseen) SR↑ | REVERIE (Val Unseen) SPL↑ | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) TL | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) NE↓ | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) SR↑ | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) SPL↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imitation | Mix | 13.77 | 3.82 | 65.51 | 56.57 | 19.02 | 5.79 | 35.64 | 28.15 | 31.31 | 2.64 | 75.83 | 26.77 |

| Imitation | Sequential | 9.35 | 4.23 | 61.09 | 58.88 | 9.24 | 7.37 | 28.37 | 26.42 | 26.57 | 3.51 | 71.70 | 24.06 |

| DAgger | Mix | 16.09 | 4.07 | 62.36 | 52.18 | 25.05 | 5.89 | 30.45 | 21.91 | 27.57 | 2.81 | 74.85 | 31.70 |

| DAgger | Sequential | 13.51 | 2.90 | 73.69 | 64.92 | 16.32 | 5.38 | 45.67 | 37.95 | 15.60 | 3.10 | 71.43 | 43.39 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of single-run performance across three different vision-language navigation (VLN) tasks (R2R, REVERIE, and ObjectNav-MP3D) under various training schemas. Specifically, it contrasts performance when using imitation learning versus DAgger (an iterative training algorithm that refines the policy using feedback from simulated agent actions) and also compares the impact of mixing datasets in the same training batch versus processing them sequentially.

read the caption

Table 6: Comparison of single-run performance with different training schema on R2R, REVERIE, and ObjectNav-MP3D.

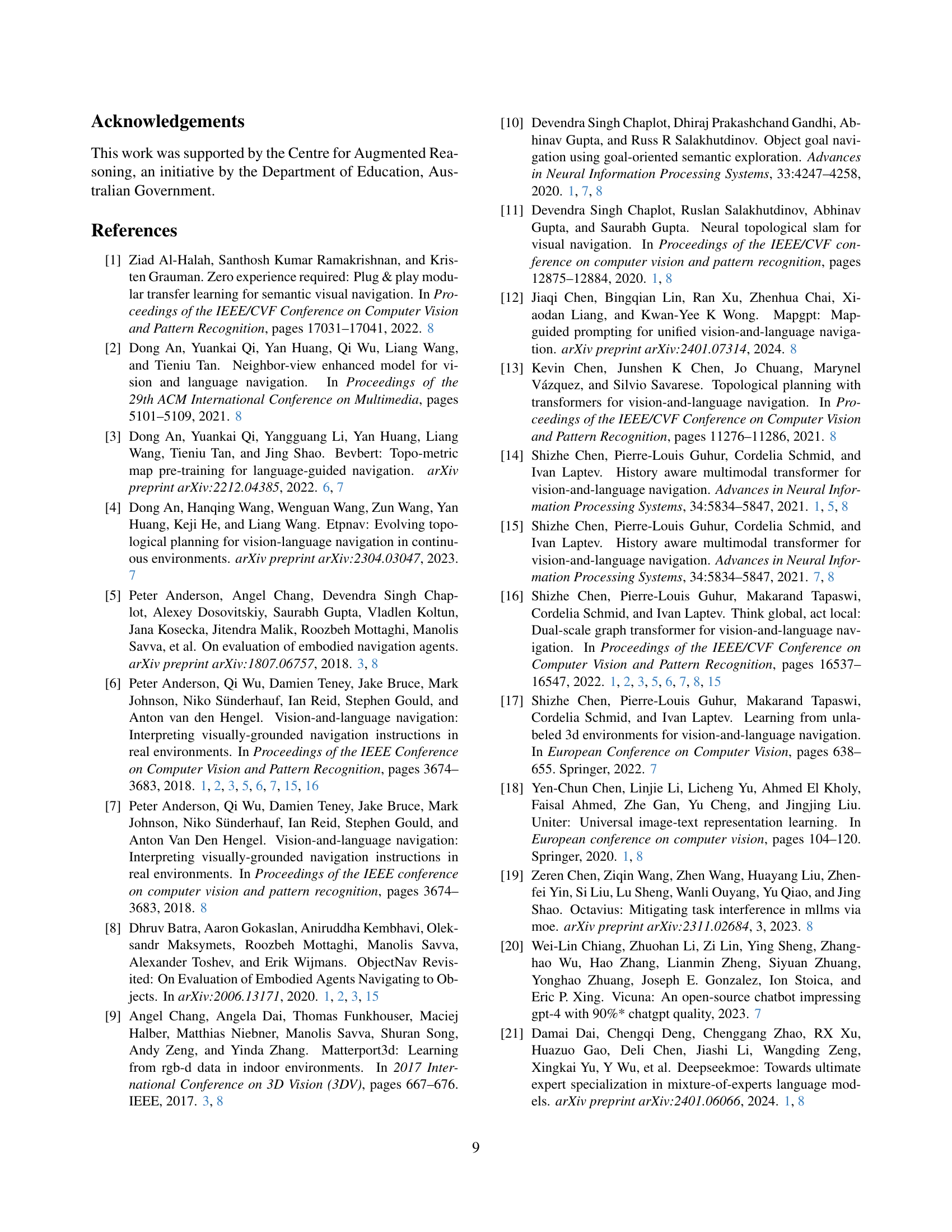

| λ | R2R (Val Unseen) | REVERIE (Val Unseen) | ObjectNav-MP3D (Val) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL | NE↓ | SR↑ | SPL↑ | TL | NE↓ | SR↑ | SPL↑ | TL | NE↓ | SR↑ | SPL↑ | |

| 0.2 | 12.63 | 2.91 | 73.61 | 65.73 | 15.47 | 5.55 | 42.86 | 35.22 | 15.25 | 3.13 | 71.79 | 43.51 |

| 0.5 | 13.77 | 2.89 | 74.29 | 65.00 | 19.45 | 5.56 | 44.70 | 34.89 | 18.10 | 3.05 | 72.26 | 40.50 |

| 0.8 | 13.51 | 2.90 | 73.69 | 64.92 | 16.32 | 5.38 | 45.67 | 37.95 | 15.60 | 3.10 | 71.43 | 43.39 |

| 1.0 | 13.56 | 3.02 | 73.56 | 64.52 | 16.19 | 5.24 | 45.81 | 37.89 | 18.11 | 2.67 | 74.66 | 44.81 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of single-run performance metrics across three vision-and-language navigation datasets (R2R, REVERIE, and ObjectNav-MP3D) when varying the load balancing coefficient (λ) in the Mixture of Experts (MoE) model. The load balancing coefficient controls the distribution of inputs across different experts, impacting model performance. The table allows readers to observe the effect of this coefficient on various metrics such as Trajectory Length (TL), Navigation Error (NE), Success Rate (SR), and SPL. This analysis is crucial for optimizing the performance of the MoE model within a multi-task learning context.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison of single-run performance with different MoE balance coefficients λ𝜆\lambdaitalic_λ on R2R, REVERIE, and ObjectNav-MP3D.

| Benchmark | TL | NE ↓ | nDTW ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ | TL | NE ↓ | GP ↑ | SR ↑ | SPL ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2R [6] | 13.65 | 2.73 | 71.05 | 76.25 | 66.16 | 14.80 | 3.03 | – | 73.92 | 64.41 |

| RxR-EN [52] | 22.69 | 6.53 | 51.20 | 50.52 | 42.19 | – | – | – | – | – |

| REVERIE [80] | 18.87 | 5.18 | 48.54 | 46.35 | 36.12 | 19.47 | – | – | 48.60 | 37.10 |

| SOON [125] | 34.42 | 8.12 | – | 36.11 | 25.42 | 37.99 | – | – | 38.18 | 27.11 |

| CVDN [99] | 30.90 | 12.72 | – | 24.48 | 17.23 | – | – | 7.07 | 18.15 | 12.18 |

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive overview of the performance achieved by the SAME model across various Vision-and-Language Navigation (VLN) benchmarks. It details the results for different metrics including Trajectory Length (TL), Navigation Error (NE), normalized Dynamic Time Warping (nDTW), Success Rate (SR), and Success Path Length (SPL). The benchmarks cover a range of tasks with varying levels of language granularity and complexity. Results are shown for both validation and test sets where available, enabling a thorough assessment of SAME’s generalization capabilities across different VLN tasks.

read the caption

Table 8: Full results of SAME on all VLN benchmarks.

Full paper#