↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current robotic visuomotor policy learning methods face challenges. Diffusion-based models improve accuracy but are computationally expensive. Autoregressive models offer efficiency but lack precision. This paper introduces CARP, a new approach aiming to solve these issues.

CARP addresses these challenges by employing a two-stage approach: 1) Multi-scale action tokenization creates efficient representations; 2) Coarse-to-fine autoregressive prediction refines actions progressively. This method achieves competitive accuracy, surpassing or matching existing methods while significantly improving inference speed (up to 10x faster). This makes it well-suited for resource-constrained real-world robotic applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in robotics and machine learning because it presents a novel and efficient approach to visuomotor policy learning. It directly addresses the limitations of existing methods by combining the strengths of autoregressive and diffusion models, offering a high-performance, flexible, and scalable solution. This work is highly relevant to current trends in generative modeling and its application to robotics, opening new avenues for research in multi-task learning and real-world robotic applications.

Visual Insights#

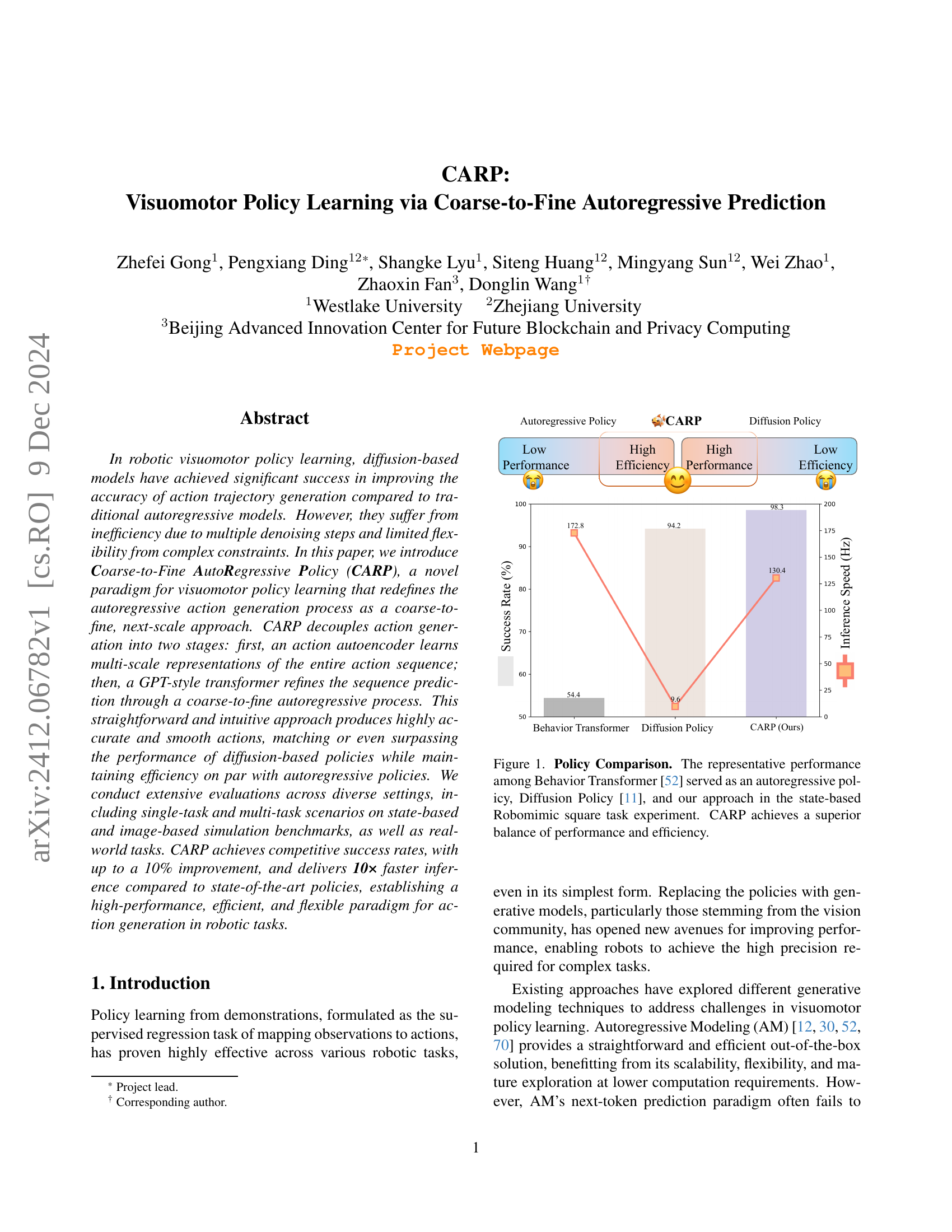

🔼 This figure compares the performance and efficiency of three different visuomotor policy learning methods on a state-based square task from the Robomimic benchmark. The methods compared are: Behavior Transformer (an autoregressive method), Diffusion Policy (a diffusion-based method), and CARP (the authors’ proposed method). The graph shows that CARP achieves a superior balance of high performance and high efficiency compared to the other two approaches.

read the caption

Figure 1: Policy Comparison. The representative performance among Behavior Transformer [52] served as an autoregressive policy, Diffusion Policy [11], and our approach in the state-based Robomimic square task experiment. CARP achieves a superior balance of performance and efficiency.

| Policy | Lift | Can | Square | Params/M | Speed/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BET [52] | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 2.12 |

| DP-C [11] | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 65.88 | 35.21 |

| DP-T [11] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 8.97 | 37.83 |

| CARP (Ours) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 3.07 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different robotic control policies on state-based simulation tasks. The policies are evaluated on three tasks of increasing difficulty: Lift, Can, and Square. The metrics reported include the average success rate (across the top three performing checkpoints), the model size (in millions of parameters), and the inference speed (in actions per second) required to generate 400 actions. The results show that CARP outperforms BET and achieves comparable performance to state-of-the-art diffusion-based policies (DP), while being significantly smaller and faster.

read the caption

Table 1: State-Based Simulation Results (State Policy). We report the average success rate of the top 3 checkpoints, along with model parameter scales and inference time for generating 400 actions. CARP significantly outperforms BET and achieves competitive performance with state-of-the-art diffusion models, while also surpassing DP in terms of model size and inference speed.

In-depth insights#

CARP’s Novel Design#

CARP introduces a novel approach to visuomotor policy learning by redefining the autoregressive process as coarse-to-fine, leveraging multi-scale action tokenization and a GPT-style transformer. This contrasts sharply with traditional methods, such as diffusion models, which rely on iterative denoising. CARP’s multi-scale tokenization captures global action structure while maintaining temporal locality, overcoming the limitations of purely sequential predictions. The coarse-to-fine refinement allows for efficient generation of highly accurate and smooth action trajectories, surpassing the accuracy of diffusion methods and maintaining the efficiency of autoregressive ones. This hybrid approach offers a compelling balance between performance and efficiency, making it highly suitable for real-world robotic applications. The use of Cross-Entropy loss further enhances the model’s performance by allowing for multi-modal action distribution predictions. The overall design is elegantly straightforward, offering a powerful and efficient framework for generating complex actions and achieving robustness in challenging robotic tasks.

Multi-Scale Tokenization#

The concept of “Multi-Scale Tokenization” offers a powerful approach to representing sequential data, such as action sequences in robotics. Instead of treating each action as an independent unit, this method breaks down the sequence into multiple scales, each capturing different levels of granularity and temporal dependencies. This hierarchical representation allows the model to simultaneously capture both short-term, fine-grained details and long-term, global patterns within the action sequence. The coarser scales provide a high-level overview of the action trajectory, while finer scales provide more detailed information. This multi-scale approach is crucial for improving the model’s ability to predict and generate complex actions, particularly in scenarios requiring long-range dependencies and precise coordination. By decoupling the representation of actions into multiple scales, the model can avoid the limitations of traditional autoregressive models, which often struggle to capture long-term dependencies. A key advantage is the increased robustness and efficiency achieved by this approach. The use of a multi-scale autoencoder (VQVAE) to learn these token maps further enhances the model’s ability to understand and generate diverse and accurate sequences. The multi-scale tokens are designed to preserve temporal locality while capturing the overall structure of the action, providing a versatile and robust representation that improves prediction and control of robot actions. This approach also has implications for other sequential data processing tasks, wherever a hierarchical structure exists.

Coarse-to-Fine Inference#

A hypothetical “Coarse-to-Fine Inference” section in a research paper would likely detail a method for progressively refining predictions, starting from a coarse-grained overview and iteratively increasing the level of detail. This approach contrasts with traditional methods that make single-step predictions. The core idea is to leverage a hierarchical representation of data or a multi-scale model architecture. Early stages focus on capturing broad patterns, while later stages concentrate on fine details and high precision. This strategy offers several potential advantages: improved efficiency by reducing the computational burden of high-resolution prediction at early stages, enhanced robustness to noise or uncertainties by first establishing a stable, coarse-grained understanding, and potentially better generalization capabilities by learning features at different levels of abstraction. The process might involve sequentially applying different model components or refining intermediate predictions through iterative feedback mechanisms. A key challenge is to efficiently integrate information across different scales while avoiding information loss. Successful implementation would require careful design of the hierarchical representation, the optimization of the refinement process, and rigorous evaluation of its performance compared to single-step alternatives. The detailed description would include algorithmic steps, architectural diagrams, and experimental results demonstrating the effectiveness of the coarse-to-fine strategy.

Sim & Real-World Tests#

A robust evaluation of any robotics algorithm necessitates both simulation and real-world testing. Simulations offer controlled environments for extensive experimentation, allowing for efficient parameter sweeps and exploration of the model’s behavior across diverse scenarios. However, real-world tests are crucial for validating the algorithm’s generalizability and robustness, as real-world conditions are inherently unpredictable and complex. A discrepancy between simulation and real-world performance could highlight limitations in the simulation model or reveal unexpected behaviors only apparent in the physical world. Careful selection of simulation benchmarks is critical to ensure that the simulation captures the essence of real-world challenges. The transition from simulation to real-world should be gradual, starting with simpler tasks in a controlled setting to gain confidence before proceeding to more complex real-world scenarios. Thorough analysis that compares simulated and real-world results and highlights areas of agreement or disagreement is essential to build a trustworthy and reliable robotic system.

Future Work Directions#

Future research directions stemming from the CARP paper could involve several key improvements. Extending CARP’s multimodality is crucial; while the paper addresses the limitations of unimodality in existing autoregressive methods, fully realizing CARP’s potential for handling diverse sensory inputs (e.g., tactile, auditory) remains an important next step. This could involve exploring more sophisticated loss functions or architectural modifications to better handle multimodal data streams. Another promising avenue lies in improving the model’s efficiency and scalability. While CARP demonstrates significant speed improvements over diffusion models, further optimization through algorithmic advancements or hardware acceleration techniques could enhance its real-world applicability in resource-constrained environments. Furthermore, leveraging the strengths of the GPT-style architecture more fully should be explored. This could involve investigating techniques for improved context utilization, possibly through the incorporation of more advanced attention mechanisms or the exploitation of techniques like mixture of experts. Finally, a significant area for future exploration involves evaluating CARP in more complex and diverse robotic manipulation scenarios. The paper’s experiments are impressive but more testing in real-world environments with greater variability and complexity would further establish its robustness and generalizability. In essence, moving from simulated scenarios to real world applications with a greater diversity of tasks is key to showing CARP’s true potential and effectiveness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

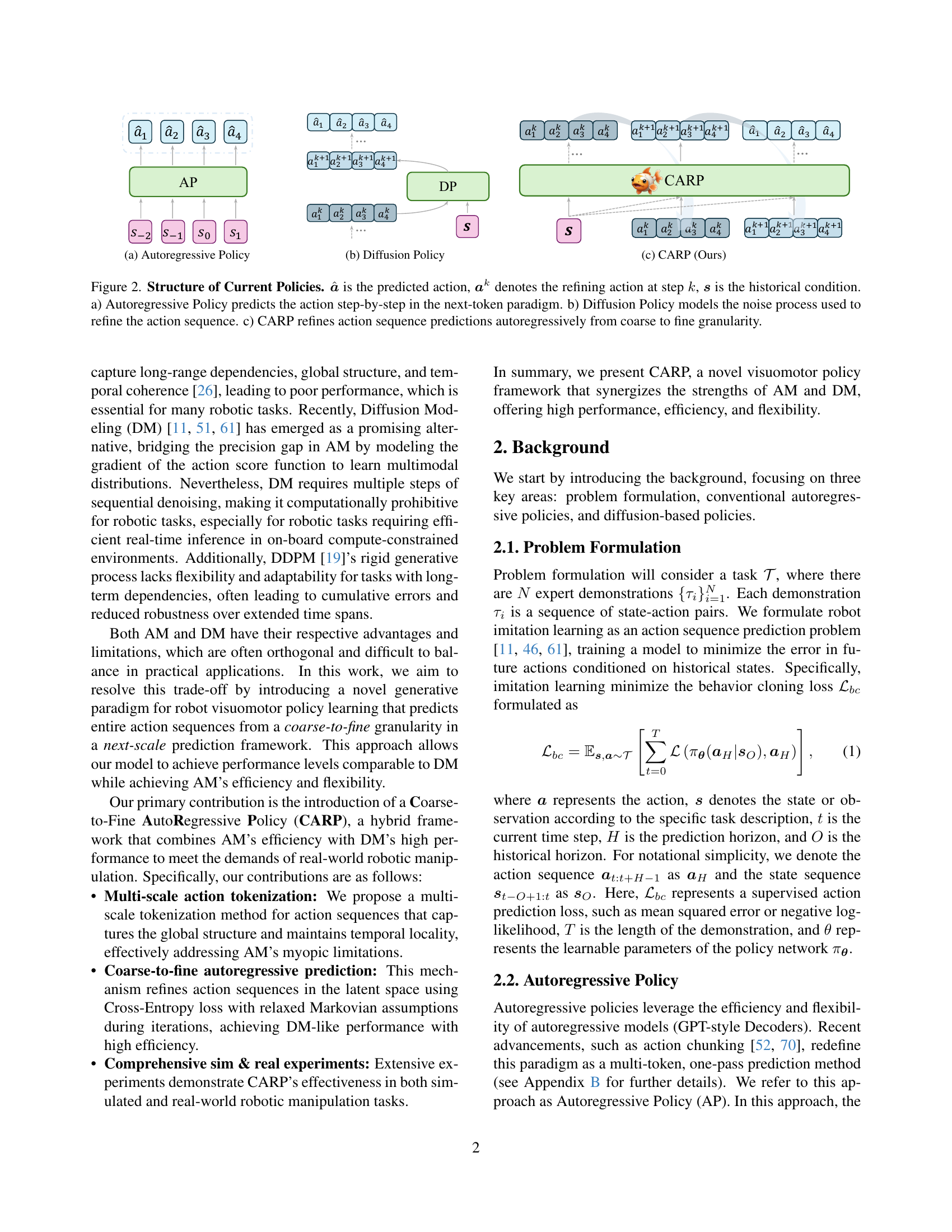

🔼 This figure illustrates the structure of an autoregressive policy. In this type of policy, the next action is predicted based solely on previous actions (a1, a2, a3, a4…) and the current state (s0, s1, s2…). The prediction process unfolds sequentially, step-by-step.

read the caption

(a) Autoregressive Policy

🔼 This figure illustrates the structure of a diffusion-based policy for visuomotor control. It depicts how an action sequence is modeled as a series of denoising steps, starting from random noise and progressively refining towards a noise-free action sequence. Each step involves a conditional probability model (e.g., a neural network) that transforms the noisy action sequence based on the current observation and the action history. This iterative refinement process allows the policy to capture the complexity and uncertainty inherent in robot actions, but can also lead to computational inefficiencies due to multiple denoising steps.

read the caption

(b) Diffusion Policy

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of CARP (Coarse-to-Fine Autoregressive Policy), a novel visuomotor policy learning framework. Unlike traditional autoregressive methods that predict actions sequentially, one step at a time, CARP introduces a coarse-to-fine approach. The action sequence is first encoded into multiple token maps at different scales (coarse to fine), capturing the global structure and temporal coherence of the entire sequence. A transformer then refines the sequence predictions in a coarse-to-fine autoregressive process using these multi-scale representations. This design allows CARP to maintain efficiency while capturing long-range dependencies and generating highly accurate and smooth actions.

read the caption

(c) CARP (Ours)

🔼 Figure 2 illustrates the differences in action prediction mechanisms between traditional autoregressive policies, diffusion-based models, and the proposed CARP model. (a) Autoregressive Policies predict actions sequentially, one at a time, based on the current prediction and the history. (b) Diffusion Policies generate an action sequence by iteratively refining a noisy prediction through a denoising process. (c) CARP improves efficiency and accuracy by using a coarse-to-fine approach. It first generates a coarse prediction of the entire sequence, then refines this prediction step by step in a next-scale fashion, gradually increasing the granularity.

read the caption

Figure 2: Structure of Current Policies. 𝒂^^𝒂\hat{\boldsymbol{a}}over^ start_ARG bold_italic_a end_ARG is the predicted action, 𝒂ksuperscript𝒂𝑘\boldsymbol{a}^{k}bold_italic_a start_POSTSUPERSCRIPT italic_k end_POSTSUPERSCRIPT denotes the refining action at step k𝑘kitalic_k, 𝒔𝒔\boldsymbol{s}bold_italic_s is the historical condition. a) Autoregressive Policy predicts the action step-by-step in the next-token paradigm. b) Diffusion Policy models the noise process used to refine the action sequence. c) CARP refines action sequence predictions autoregressively from coarse to fine granularity.

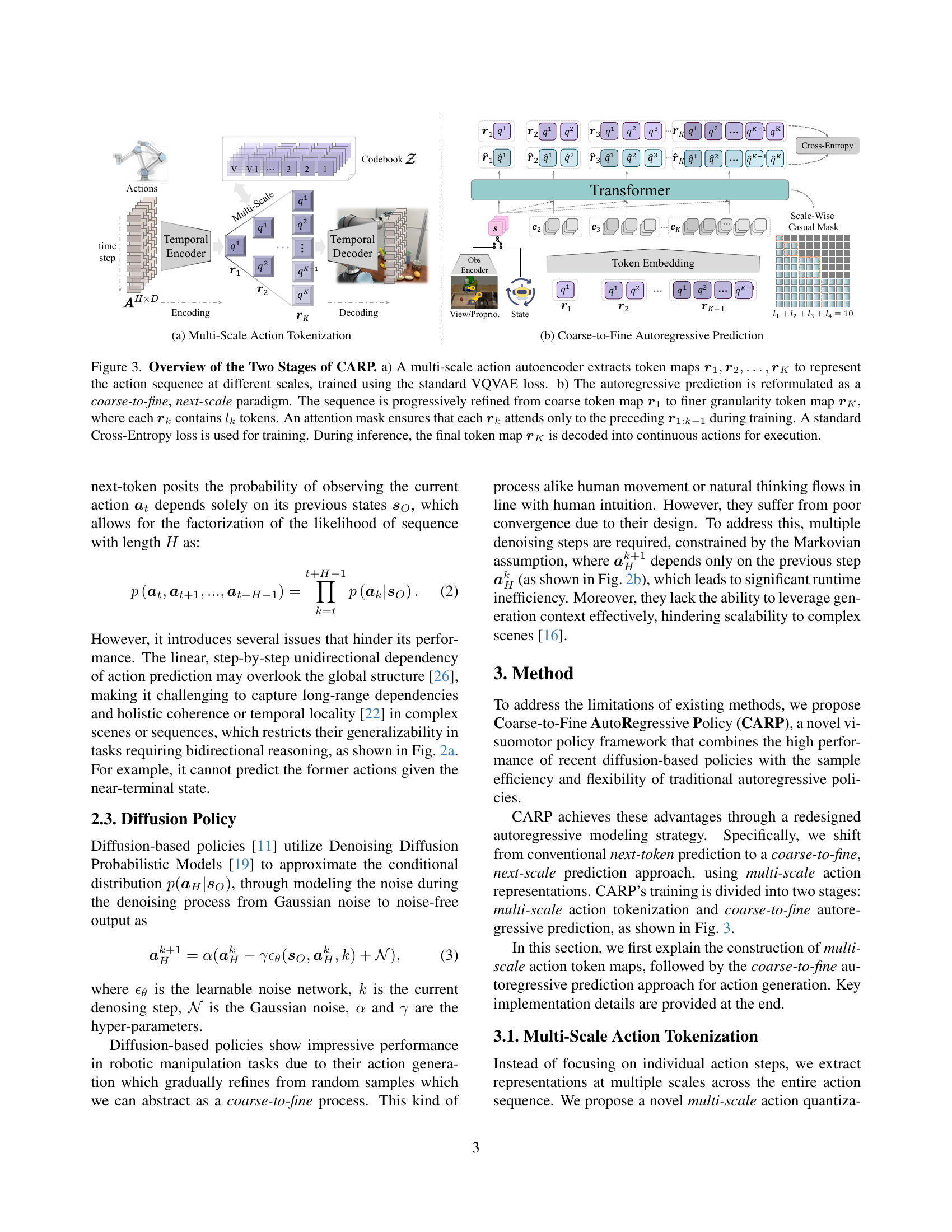

🔼 This figure shows the process of multi-scale action tokenization in CARP. An action autoencoder takes a sequence of actions as input and generates multiple token maps at different scales (r1, r2…rk). Each token map represents the action sequence at a particular scale, capturing the action sequence’s global structure and maintaining its temporal locality. The autoencoder consists of an encoder, a quantizer, and a decoder, enabling a hierarchical encoding and decoding of action sequences.

read the caption

(a) Multi-Scale Action Tokenization

🔼 This figure shows the second stage of the CARP (Coarse-to-Fine Autoregressive Policy) model. It illustrates how the autoregressive prediction process is structured as a coarse-to-fine, next-scale approach. The model progressively refines action predictions from a coarse representation (r1) to a finer representation (rk), with each step attending only to the preceding steps. The final token map (rk) is then decoded into continuous actions for execution. A cross-entropy loss is used during training.

read the caption

(b) Coarse-to-Fine Autoregressive Prediction

🔼 Figure 3 illustrates the two-stage process of CARP (Coarse-to-Fine Autoregressive Policy). Stage (a) shows a multi-scale action autoencoder. This autoencoder takes an action sequence as input and produces multiple token maps (r1, r2… rK), each representing the sequence at a different level of detail. These maps are generated using a Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder (VQVAE) which minimizes the reconstruction error. Stage (b) shows the autoregressive prediction process. Starting from the coarsest token map (r1), the model progressively refines the action sequence through finer-grained token maps (r2, r3… rK). An attention mechanism ensures that each token map considers only the previous maps during training. The training uses a cross-entropy loss function. During inference, only the final, most detailed token map (rK) is decoded to generate a continuous action sequence.

read the caption

Figure 3: Overview of the Two Stages of CARP. a) A multi-scale action autoencoder extracts token maps 𝒓1,𝒓2,…,𝒓Ksubscript𝒓1subscript𝒓2…subscript𝒓𝐾\boldsymbol{r}_{1},\boldsymbol{r}_{2},\dots,\boldsymbol{r}_{K}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 2 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , … , bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_K end_POSTSUBSCRIPT to represent the action sequence at different scales, trained using the standard VQVAE loss. b) The autoregressive prediction is reformulated as a coarse-to-fine, next-scale paradigm. The sequence is progressively refined from coarse token map 𝒓1subscript𝒓1\boldsymbol{r}_{1}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT to finer granularity token map 𝒓Ksubscript𝒓𝐾\boldsymbol{r}_{K}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_K end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, where each 𝒓ksubscript𝒓𝑘\boldsymbol{r}_{k}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_k end_POSTSUBSCRIPT contains lksubscript𝑙𝑘l_{k}italic_l start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_k end_POSTSUBSCRIPT tokens. An attention mask ensures that each 𝒓ksubscript𝒓𝑘\boldsymbol{r}_{k}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_k end_POSTSUBSCRIPT attends only to the preceding 𝒓1:k−1subscript𝒓:1𝑘1\boldsymbol{r}_{1:k-1}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 : italic_k - 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT during training. A standard Cross-Entropy loss is used for training. During inference, the final token map 𝒓Ksubscript𝒓𝐾\boldsymbol{r}_{K}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_K end_POSTSUBSCRIPT is decoded into continuous actions for execution.

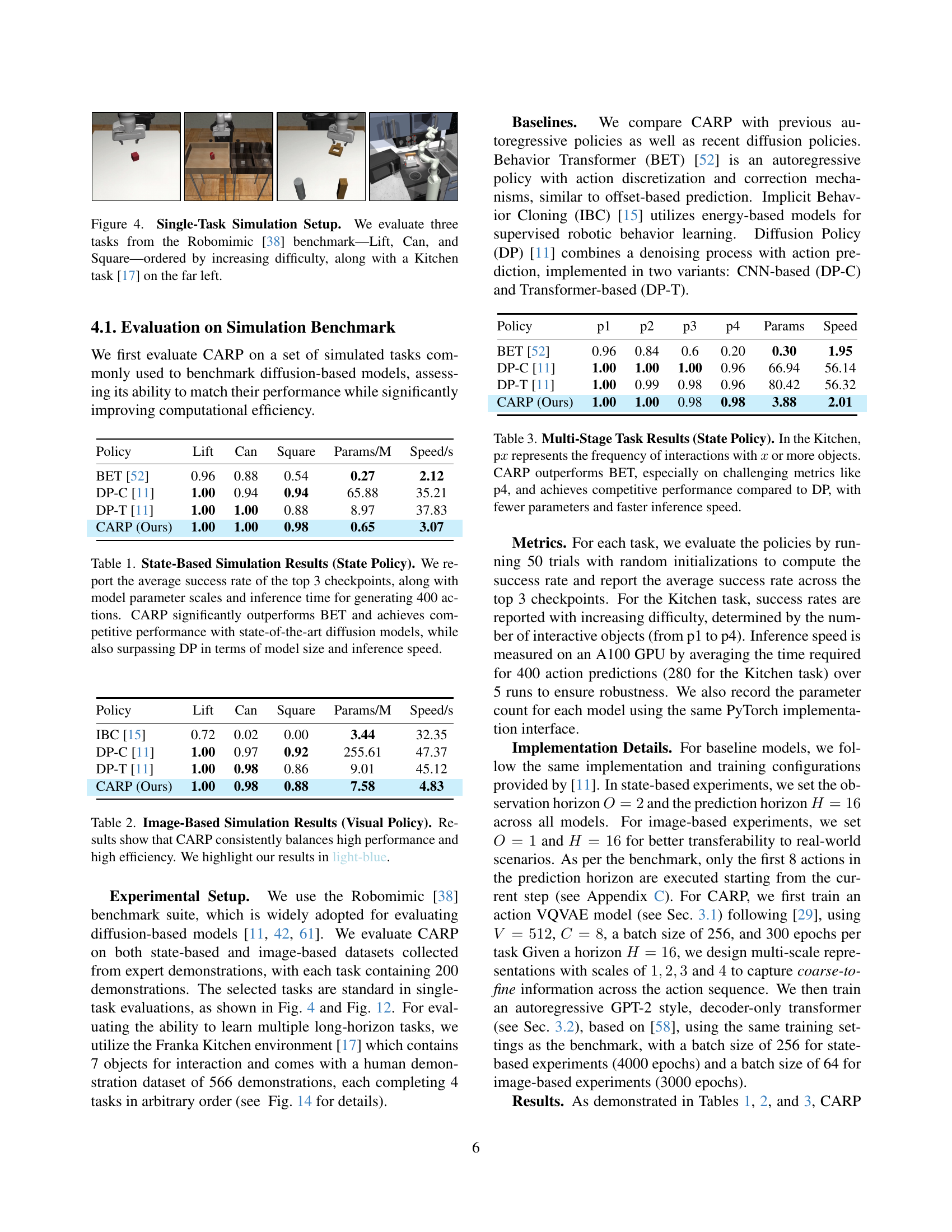

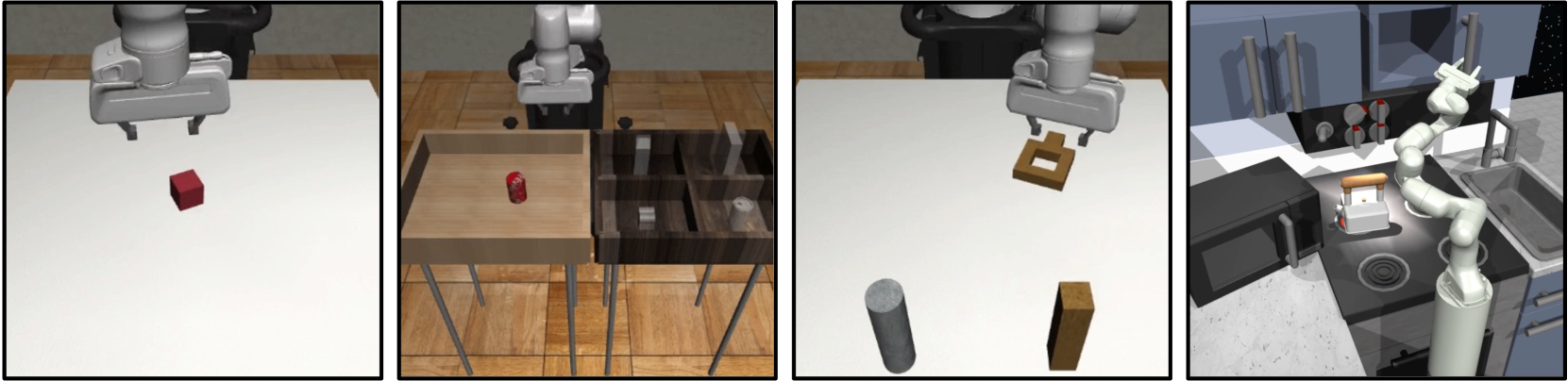

🔼 Figure 4 shows the experimental setup for single-task simulations used in the paper. Four tasks are shown: ‘Lift’, ‘Can’, and ‘Square’ from the Robomimic benchmark, ordered from easiest to hardest, and a ‘Kitchen’ task from a separate benchmark. These tasks are used to evaluate the performance of different robotic control policies in a controlled simulated environment.

read the caption

Figure 4: Single-Task Simulation Setup. We evaluate three tasks from the Robomimic [38] benchmark—Lift, Can, and Square—ordered by increasing difficulty, along with a Kitchen task [17] on the far left.

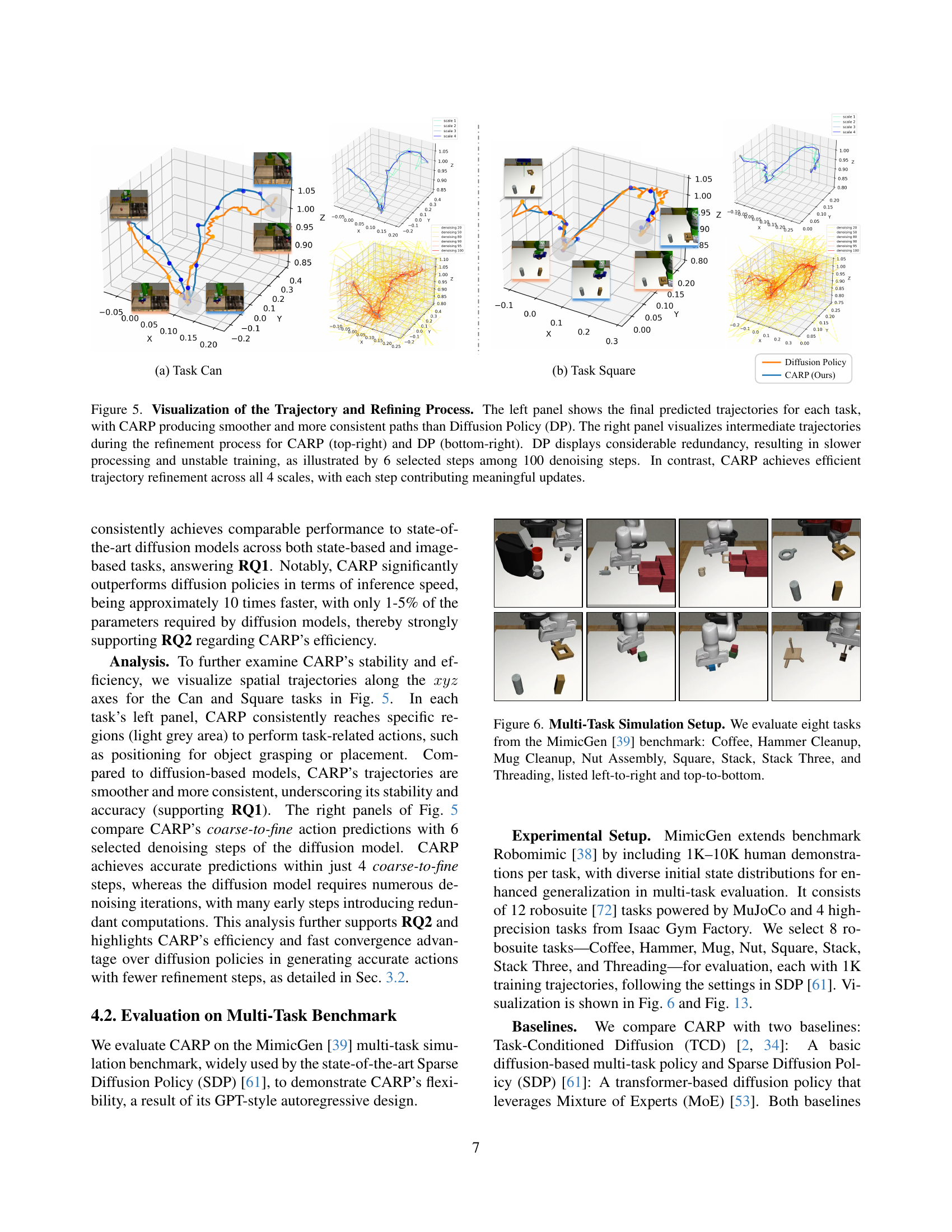

🔼 This figure compares the trajectory generation process of CARP and Diffusion Policy (DP). The left side displays the final trajectories for the ‘Can’ and ‘Square’ tasks, showing CARP’s smoother and more consistent paths compared to DP’s less refined results. The right side visualizes the intermediate steps during trajectory refinement for both methods. It highlights the redundancy of DP’s 100-step denoising process (6 steps are shown), leading to slower processing and unstable training, while CARP efficiently refines the trajectory across 4 scales, with each step providing significant improvements.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualization of the Trajectory and Refining Process. The left panel shows the final predicted trajectories for each task, with CARP producing smoother and more consistent paths than Diffusion Policy (DP). The right panel visualizes intermediate trajectories during the refinement process for CARP (top-right) and DP (bottom-right). DP displays considerable redundancy, resulting in slower processing and unstable training, as illustrated by 6 selected steps among 100 denoising steps. In contrast, CARP achieves efficient trajectory refinement across all 4 scales, with each step contributing meaningful updates.

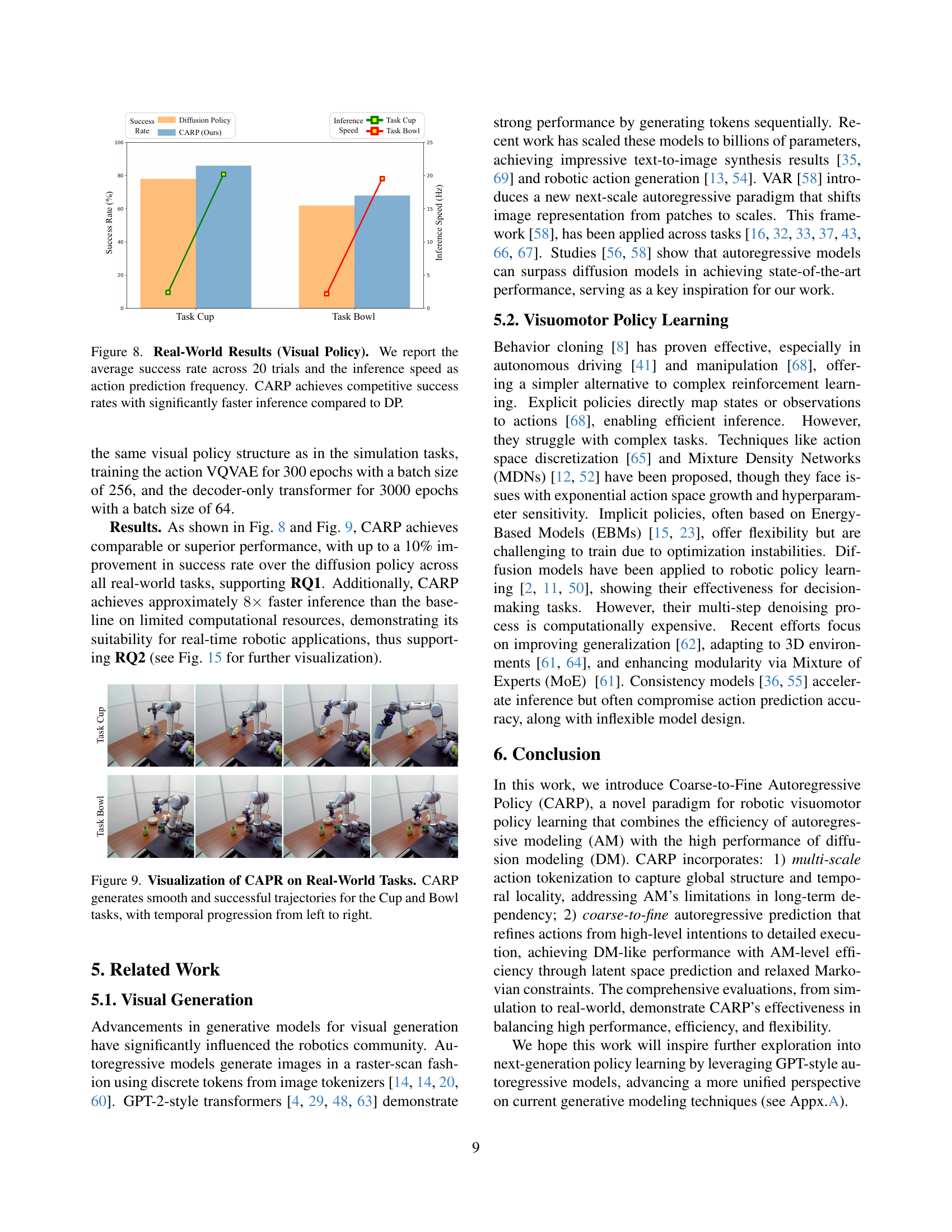

🔼 This figure showcases the eight multi-task simulation scenarios used to evaluate the CARP model. The tasks, sourced from the MimicGen benchmark, are displayed in a 2x4 grid, arranged from left to right and top to bottom. Each task presents a unique robotic manipulation challenge: Coffee, Hammer Cleanup, Mug Cleanup, Nut Assembly, Square (block arrangement), Stack (block stacking), Stack Three (stacking three blocks), and Threading (threading a needle). The visual representation offers a clear overview of the diverse manipulation skills tested within this experiment.

read the caption

Figure 6: Multi-Task Simulation Setup. We evaluate eight tasks from the MimicGen [39] benchmark: Coffee, Hammer Cleanup, Mug Cleanup, Nut Assembly, Square, Stack, Stack Three, and Threading, listed left-to-right and top-to-bottom.

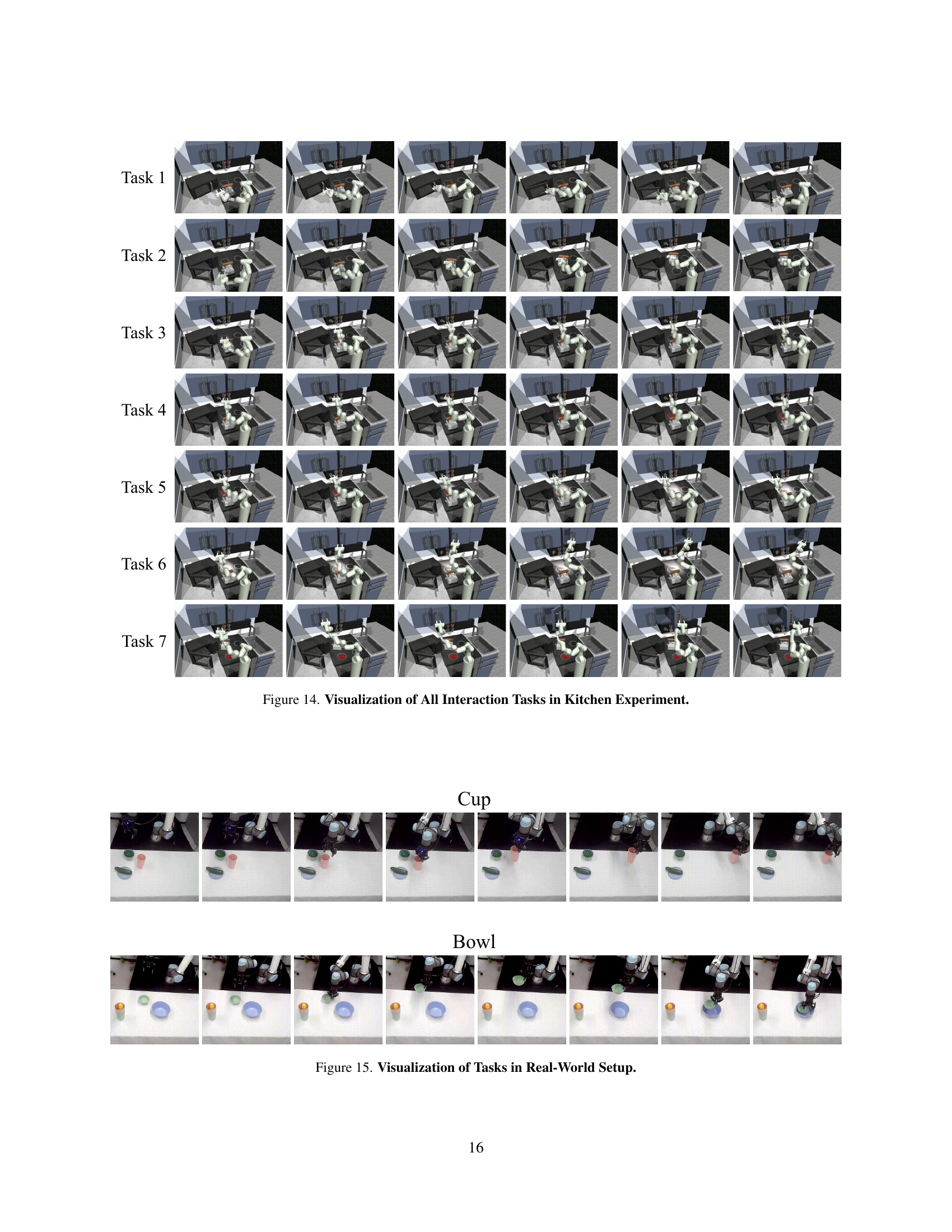

🔼 This figure shows the setup for real-world robotic manipulation experiments and example trajectories. The left panel depicts the experimental environment, including a UR5e robotic arm, a Robotiq-2f-85 gripper, and two RGB cameras (one wrist-mounted and one in a third-person view). The right panel displays example trajectories for two tasks: (top) picking up a cup from a table and placing it down, and (bottom) picking up a smaller bowl and placing it inside a larger bowl. These trajectories illustrate the robot’s successful execution of these tasks.

read the caption

Figure 7: Real-World Setup. The left panel shows the environment used for the experiment and demonstration collection. The right panel shows the trajectory from the Cup and Bowl datasets.

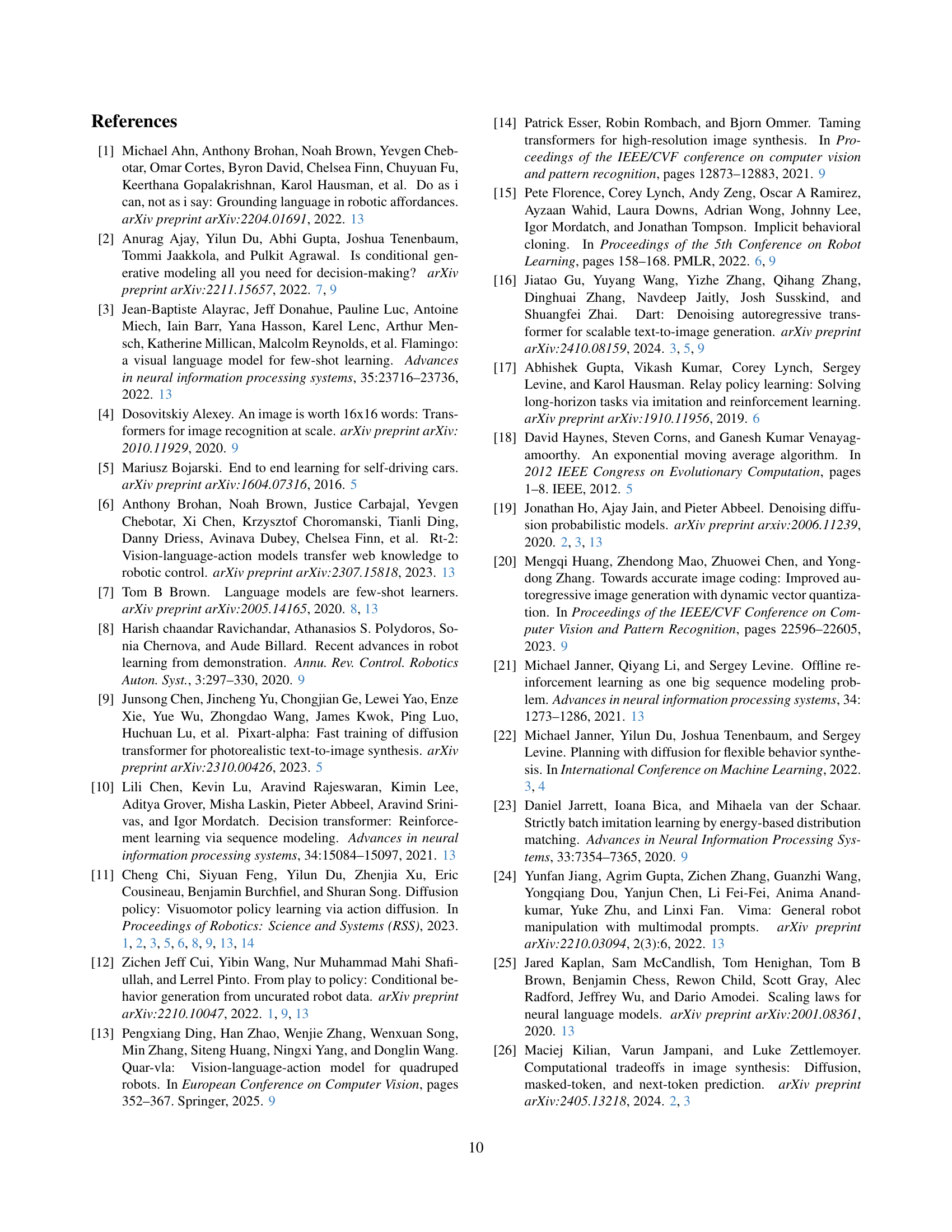

🔼 Figure 8 presents a bar chart summarizing the performance of CARP and Diffusion Policy (DP) on two real-world robotic manipulation tasks: Cup and Bowl. The chart displays both the average success rate (across 20 trials) and the inference speed (measured as action prediction frequency in Hertz) for each method on each task. The results show that CARP achieves comparable success rates to DP but with a significant improvement in inference speed, demonstrating its efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 8: Real-World Results (Visual Policy). We report the average success rate across 20 trials and the inference speed as action prediction frequency. CARP achieves competitive success rates with significantly faster inference compared to DP.

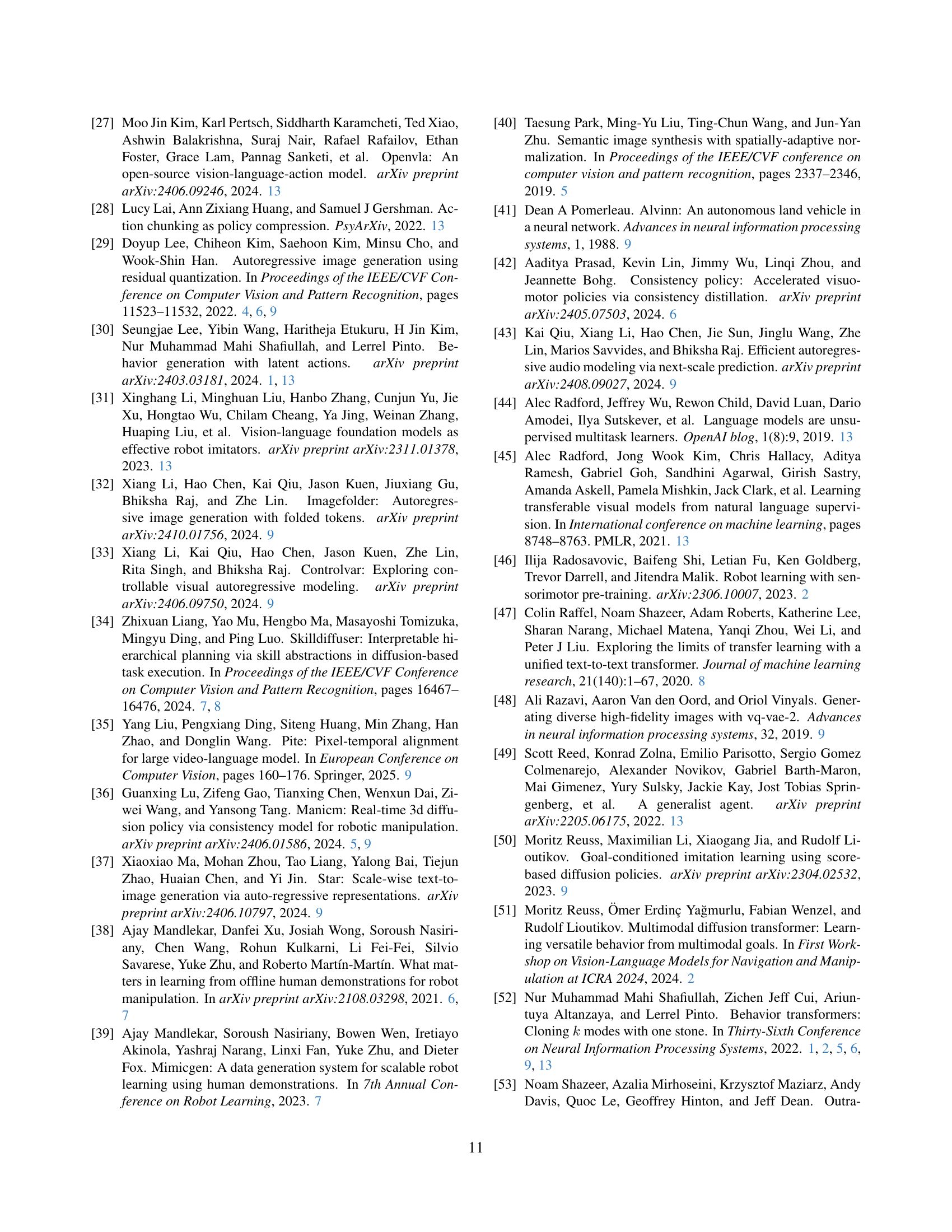

🔼 Figure 9 shows the results of applying the CARP model to two real-world robotic manipulation tasks: Cup and Bowl. For each task, a sequence of images demonstrates the robot’s actions, progressing from left to right to show the smooth and successful trajectory generated by the CARP algorithm. The images illustrate how CARP effectively plans and executes the manipulation tasks.

read the caption

Figure 9: Visualization of CAPR on Real-World Tasks. CARP generates smooth and successful trajectories for the Cup and Bowl tasks, with temporal progression from left to right.

🔼 During inference, CARP uses a coarse-to-fine prediction approach. It starts with a coarse representation of the action sequence (𝑟₁, 𝑟₂, etc.) and progressively refines it to the finest level (𝑟ₖ). This process leverages kv-caching to efficiently generate predictions, eliminating the need for causal masking. The final, most detailed representation (𝑟ₖ) is then decoded by the action VQVAE to produce the actual control commands for the robot arm.

read the caption

Figure 10: Coarse-to-Fine Autoregressive Inference. During inference, we leverage kv-caching to enable coarse-to-fine prediction without the need for causal masks. The finest-scale token map 𝒓Ksubscript𝒓𝐾\boldsymbol{r}_{K}bold_italic_r start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_K end_POSTSUBSCRIPT is subsequently decoded by the action VQVAE decoder into executable actions for the robotic arm.

🔼 Figure 11 illustrates the conventional approach of autoregressive policies in reinforcement learning. Unlike the action chunking method shown in Figure 2(a), this approach generates action tokens sequentially, meaning that each token’s prediction is solely dependent on the tokens generated before it in the sequence. This sequential, step-by-step process contrasts with methods that can predict multiple tokens or even the entire action sequence at once.

read the caption

Figure 11: Conventional Autoregressive Policy. In reinforcement learning, conventional autoregressive policies generate action tokens sequentially, where each token is predicted based on the previously generated tokens. This differs from the action chunking prediction shown in Fig. 2(a).

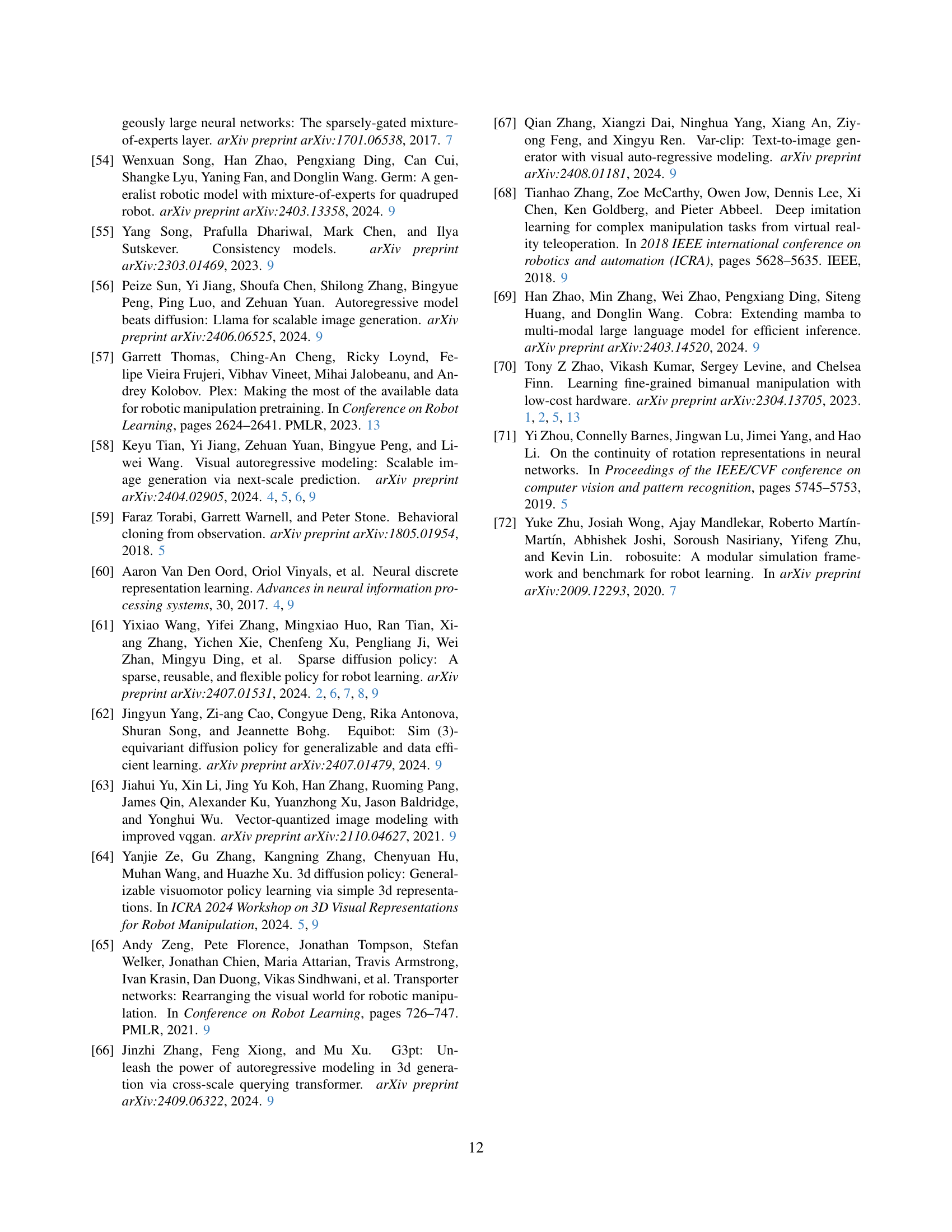

🔼 Figure 12 shows a visualization of the three single-task experiments from the Robomimic benchmark: Lift, Can, and Square, along with the Kitchen task. Each row represents one task and shows a sequence of images capturing the robot’s actions throughout the task execution.

read the caption

Figure 12: Visualization of Tasks in Single-Task Experiment.

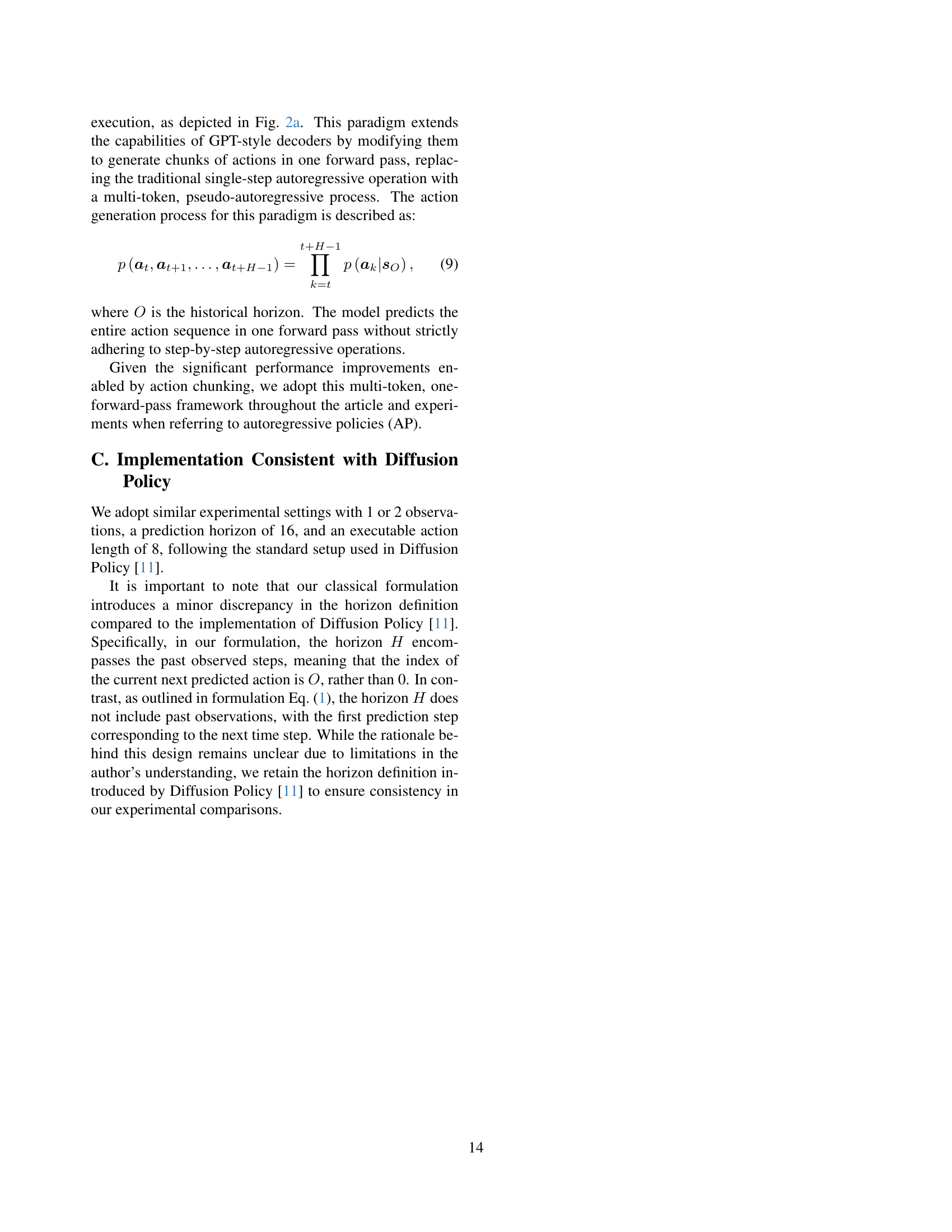

🔼 Figure 13 shows a visualization of the eight multi-task experiments from the MimicGen benchmark. Each row displays a sequence of images showing the robot performing the steps required for a given task. The tasks include Coffee, Hammer Cleanup, Mug Cleanup, Nut Assembly, Square, Stack, Stack Three, and Threading. The images illustrate the actions performed by the robot arm during the execution of each task, providing a visual representation of the robot’s performance.

read the caption

Figure 13: Visualization of Tasks in Multi-Task Experiment.

More on tables

| Policy | Lift | Can | Square | Params/M | Speed/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBC [15] | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 3.44 | 32.35 |

| DP-C [11] | 1.00 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 255.61 | 47.37 |

| DP-T [11] | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 9.01 | 45.12 |

| CARP (Ours) | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 7.58 | 4.83 |

🔼 This table presents the results of image-based visuomotor policy learning experiments on the Robomimic benchmark. It compares the performance of CARP against other state-of-the-art methods (IBC, DP-C, DP-T) across three tasks: Lift, Can, and Square, ordered by increasing difficulty. The metrics reported include the success rate (percentage of successful task completions) for each task, model size (in millions of parameters), and inference speed (in Hz). The results show that CARP achieves high success rates while maintaining computational efficiency, outperforming or matching the other methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Image-Based Simulation Results (Visual Policy). Results show that CARP consistently balances high performance and high efficiency. We highlight our results in light-blue.

| Policy | p1 | p2 | p3 | p4 | Params | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BET [52] | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.6 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 1.95 |

| DP-C [11] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 66.94 | 56.14 |

| DP-T [11] | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 80.42 | 56.32 |

| CARP (Ours) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 3.88 | 2.01 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different robot control policies on a multi-stage task, specifically the Franka Kitchen task. The policies compared are Behavior Transformer (BET), Diffusion Policy with CNN (DP-C), Diffusion Policy with Transformer (DP-T), and the proposed CARP method. The table shows the success rate (p1 to p4 indicating interaction with 1, 2, 3, or 4 or more objects respectively) for each policy, along with the number of parameters and inference speed in Hz. CARP demonstrates superior performance to BET, especially in more complex scenarios (p4), and matches DP’s accuracy while using fewer parameters and achieving faster inference speed.

read the caption

Table 3: Multi-Stage Task Results (State Policy). In the Kitchen, px𝑥xitalic_x represents the frequency of interactions with x𝑥xitalic_x or more objects. CARP outperforms BET, especially on challenging metrics like p4, and achieves competitive performance compared to DP, with fewer parameters and faster inference speed.

| Policy | Prams/M | Speed/s | Coffee | Hammer | Mug | Nut | Square | Stack | Stack three | Threading | Avg. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCD [34] | 156.11 | 107.15 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 0.53 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.68 |

| SDP [61] | 159.85 | 112.39 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.78 |

| CARP (Ours) | 16.08 | 6.92 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.85 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of different models on multiple robotic manipulation tasks using visual input. The metrics include success rates (averaged across the top 3 model checkpoints for each task and overall), the number of model parameters, and the inference speed (time to generate 400 action predictions). CARP demonstrates significantly improved performance (9-25% higher success rates) and efficiency (over 10x faster inference and substantially fewer parameters) compared to the baseline diffusion-based models.

read the caption

Table 4: Multi-Task Simulation Results (Visual Policy). Success rates are averaged across the top three checkpoints for each task, as well as the overall average across all tasks. We also report parameter count and inference time for generating 400 actions. CARP outperforms diffusion-based policies by 9%-25% in average performance, with significantly fewer parameters and over 10× faster inference.

Full paper#