↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

High-realism video diffusion models are computationally expensive, limiting their use on mobile devices. Existing acceleration methods primarily focus on reducing sampling steps, failing to address the inherent memory constraints. This paper presents MobileVD, the first mobile-optimized video diffusion model.

MobileVD addresses these issues by employing several optimizations. These include reducing frame resolution, introducing multi-scale temporal representations, and implementing novel pruning schemas to reduce channel and temporal block counts. Adversarial finetuning further accelerates the process by reducing denoising to a single step. The result is a model that is significantly more efficient while maintaining reasonable visual quality, achieving a 523x efficiency gain compared to SVD on a mobile device.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in mobile computer vision and AI. It demonstrates a significant advancement in mobile video generation, addressing a critical limitation of existing models. The techniques developed, particularly the novel pruning methods and channel compression, could be widely applicable to other resource-constrained AI applications. It opens doors for further research in efficient model design for on-device AI and improved video generation quality on mobile devices.

Visual Insights#

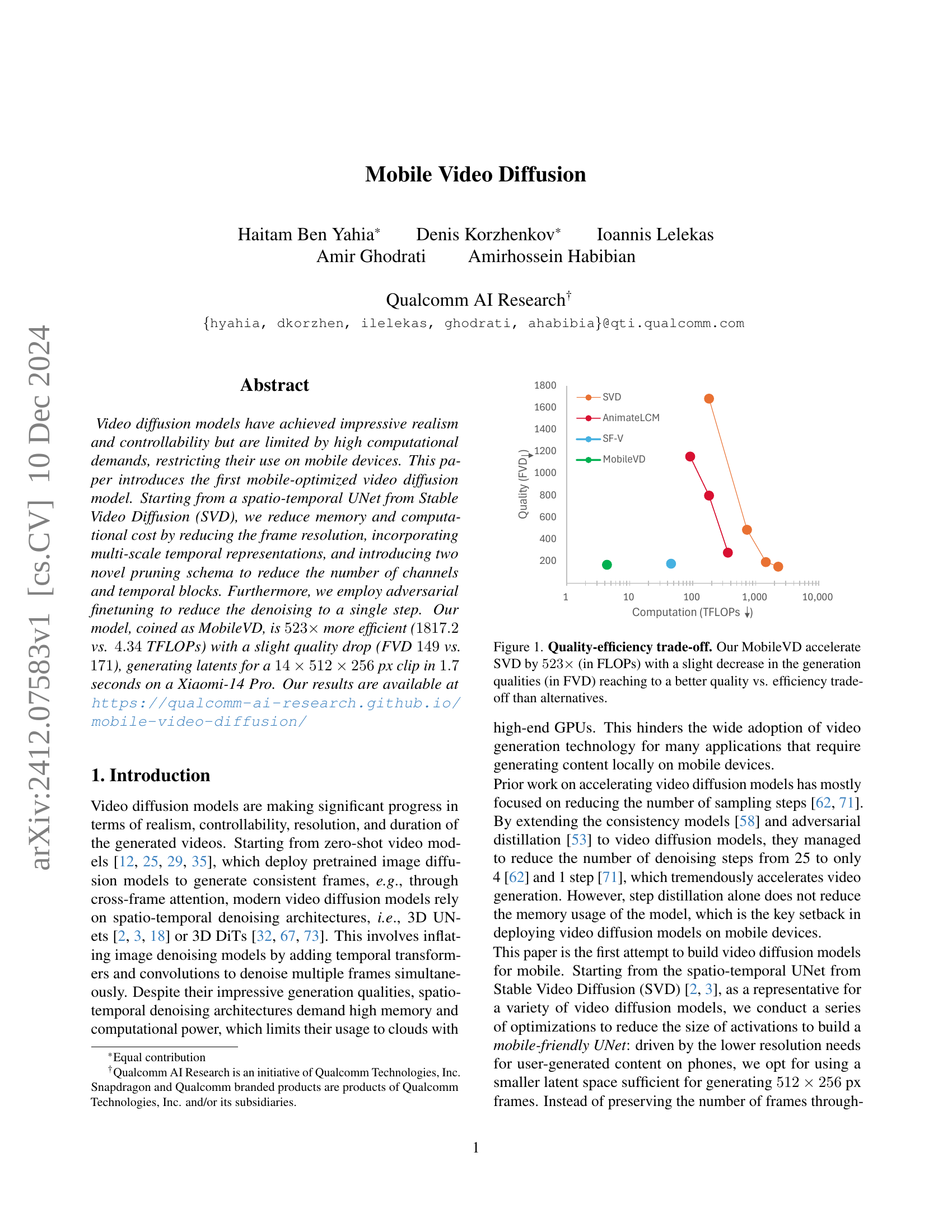

🔼 The figure illustrates the trade-off between computational efficiency and generated video quality for different video diffusion models. MobileVD, a novel mobile-optimized model, achieves a 523x speedup over Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) while incurring only a slight reduction in quality as measured by the Fréchet Video Distance (FVD). This improvement positions MobileVD favorably against competing models in terms of its quality-efficiency balance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Quality-efficiency trade-off. Our MobileVD accelerate SVD by 523×523\times523 × (in FLOPs) with a slight decrease in the generation qualities (in FVD) reaching to a better quality vs. efficiency trade-off than alternatives.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the MobileVD model with several state-of-the-art video generation models. It shows the floating point operations (FLOPs) and latency (time taken for processing) required for generating a single video frame. Importantly, it notes that the Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) values for some models are taken from an external source (Zhang et al., 2024), while others are measured using the same UCF-101 dataset and conditions for consistent comparison. The FVD, a metric of video quality, and FLOPs, and latency are reported for both high- and low-resolution settings.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with recent models. FLOPs and latency are provided for a single function evaluation with batch size of 1. For rows marked with asterisk∗ FVD measurements were taken from Zhang et al. [71], while performance metrics are based on our measurements for UNet used by SVD. For consistency with these results, FVD for SVD and our MobileVD model was measured on UCF-101 dataset at 7 frames per second.

In-depth insights#

MobileVD: Genesis#

The heading ‘MobileVD: Genesis’ suggests an exploration of the origins and foundational design principles behind the MobileVD model. A thoughtful analysis would delve into the selection of Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) as the base model, examining why SVD’s architecture was deemed suitable for mobile optimization, and what specific aspects made it a suitable starting point. The discussion should then proceed to cover the key architectural choices and modifications introduced for mobile efficiency, including resolution reduction, multi-scale temporal representations, and the crucial role of pruning schemes (channel funneling and temporal block pruning). Furthermore, a detailed look at the adversarial finetuning technique and its contribution to achieving single-step denoising would be essential. Finally, the section should critically evaluate the trade-offs between model size, computational cost, and generated video quality, emphasizing the inherent design challenges in balancing these competing requirements for mobile deployment. In essence, ‘MobileVD: Genesis’ should provide a comprehensive account of the design decisions and rationale leading to the creation of this innovative model, offering valuable insights into the process of optimizing complex generative models for resource-constrained environments.

UNet Optimization#

Optimizing the UNet architecture for mobile deployment is crucial due to its high computational demands. Strategies focus on reducing the model’s size and computational complexity without significantly sacrificing performance. This involves exploring different techniques, such as reducing input resolution, which lowers the computational burden but may impact visual quality if not carefully finetuned. Multi-scale temporal representations can also be beneficial, efficiently capturing motion dynamics across different temporal scales. Pruning techniques, eliminating less important channels or temporal blocks, further decrease model size. Channel funneling offers a novel approach, reducing intermediate channel dimensionality during inference. Finally, adversarial finetuning enables significant speedup by decreasing the number of denoising steps. The thoughtful combination of these techniques allows for a considerable reduction in computational cost while maintaining acceptable visual quality, thereby making video diffusion models deployable on mobile devices. Careful consideration of trade-offs between model size, computational cost, and quality is paramount.

MobileVD: Results#

A hypothetical ‘MobileVD: Results’ section would detail the performance of the mobile-optimized video diffusion model. Key metrics would include frames per second (FPS), achieved on target hardware (e.g., a Xiaomi 14 Pro). Comparisons against existing video diffusion models (like Stable Video Diffusion or others) would be essential, showcasing improvements in inference speed and efficiency (measured in TFLOPs). A crucial aspect would be assessing the trade-off between speed and visual quality (e.g., using Fréchet Video Distance - FVD). The results should demonstrate a substantial reduction in computational cost while maintaining acceptable visual fidelity compared to larger, non-mobile models. Ablation studies investigating the individual contributions of each optimization (e.g., resolution reduction, temporal multi-scaling) would validate the effectiveness of the proposed techniques. Finally, the section might include qualitative results, such as visual examples of videos generated by MobileVD to showcase its capabilities and quality.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, these studies are crucial for demonstrating the effectiveness of each proposed technique. By isolating the impact of individual parts, researchers can confidently attribute performance gains or losses to specific modifications. For instance, an ablation study might remove a particular module, such as a cross-attention layer or a temporal block, and then evaluate the model’s performance. This helps determine if that component significantly impacts the overall outcome. A well-designed ablation study will systematically vary the removed components, and measure the resulting changes in accuracy or efficiency. This rigorous approach helps to uncover unexpected interactions between components, ensuring a more robust and reliable understanding of model design. The results of ablation studies usually appear in tables and figures, which show the model’s performance under different configurations. These provide compelling evidence about the importance and effectiveness of different elements of the model architecture.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for mobile video diffusion models could focus on several key areas. Improving efficiency remains paramount, exploring more advanced compression techniques beyond channel pruning and low-rank approximations. Higher resolution and frame rate generation are crucial for practical applications, requiring substantial advancements in model architecture and training strategies. Enhanced controllability is another key focus, allowing users to fine-tune generated videos with more precise control over details, motion, and style. Addressing data limitations in the training process is vital; methods for efficiently utilizing smaller, domain-specific datasets are needed. Finally, exploring novel architectures such as transformers or diffusion models specifically designed for mobile hardware could lead to breakthroughs in both speed and quality. Robustness to noisy input and deployment on diverse hardware platforms are also important considerations. Ultimately, the aim is to develop versatile, user-friendly mobile tools capable of producing high-quality video content with minimal computational constraints.

More visual insights#

More on figures

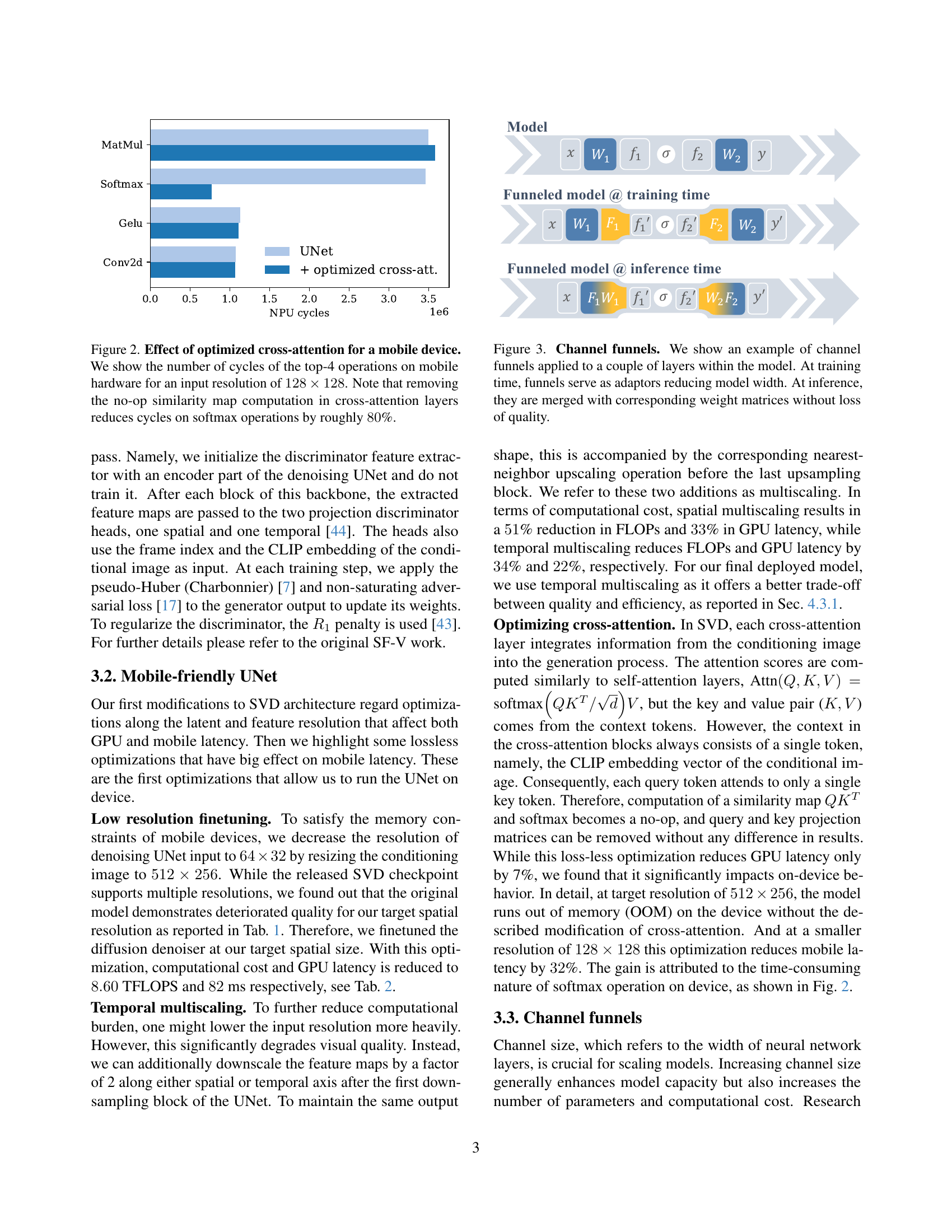

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of optimizing cross-attention mechanisms on mobile device performance. It displays the number of CPU cycles required for the four most computationally expensive operations (MatMul, Softmax, Gelu, and Conv2D) within the UNet architecture, using an input resolution of 128x128 pixels. A key finding highlighted is that removing unnecessary computations related to the similarity map in cross-attention layers leads to an approximately 80% reduction in the number of cycles needed for the Softmax operation, significantly improving efficiency on mobile hardware.

read the caption

Figure 2: Effect of optimized cross-attention for a mobile device. We show the number of cycles of the top-4 operations on mobile hardware for an input resolution of 128×128128128128\times 128128 × 128. Note that removing the no-op similarity map computation in cross-attention layers reduces cycles on softmax operations by roughly 80808080%.

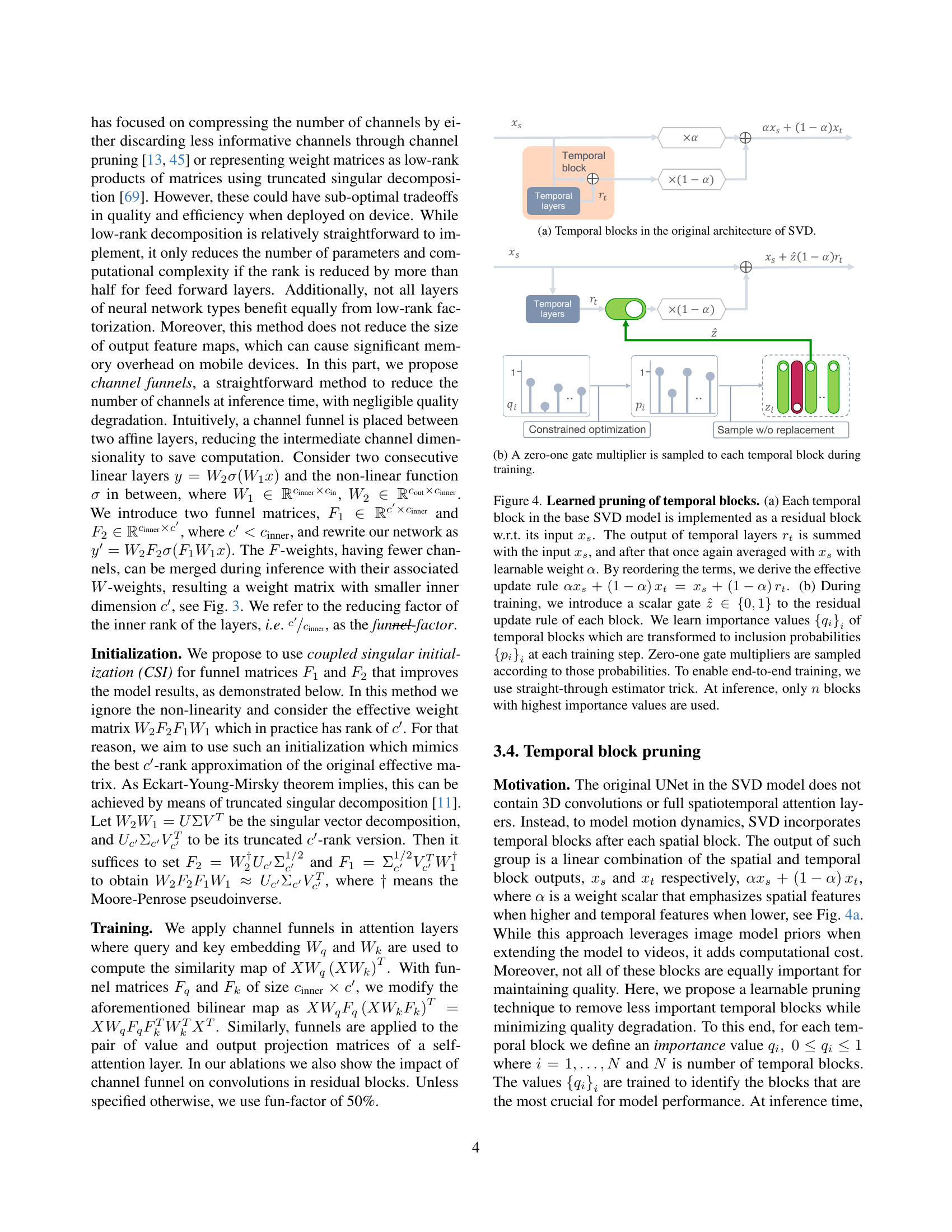

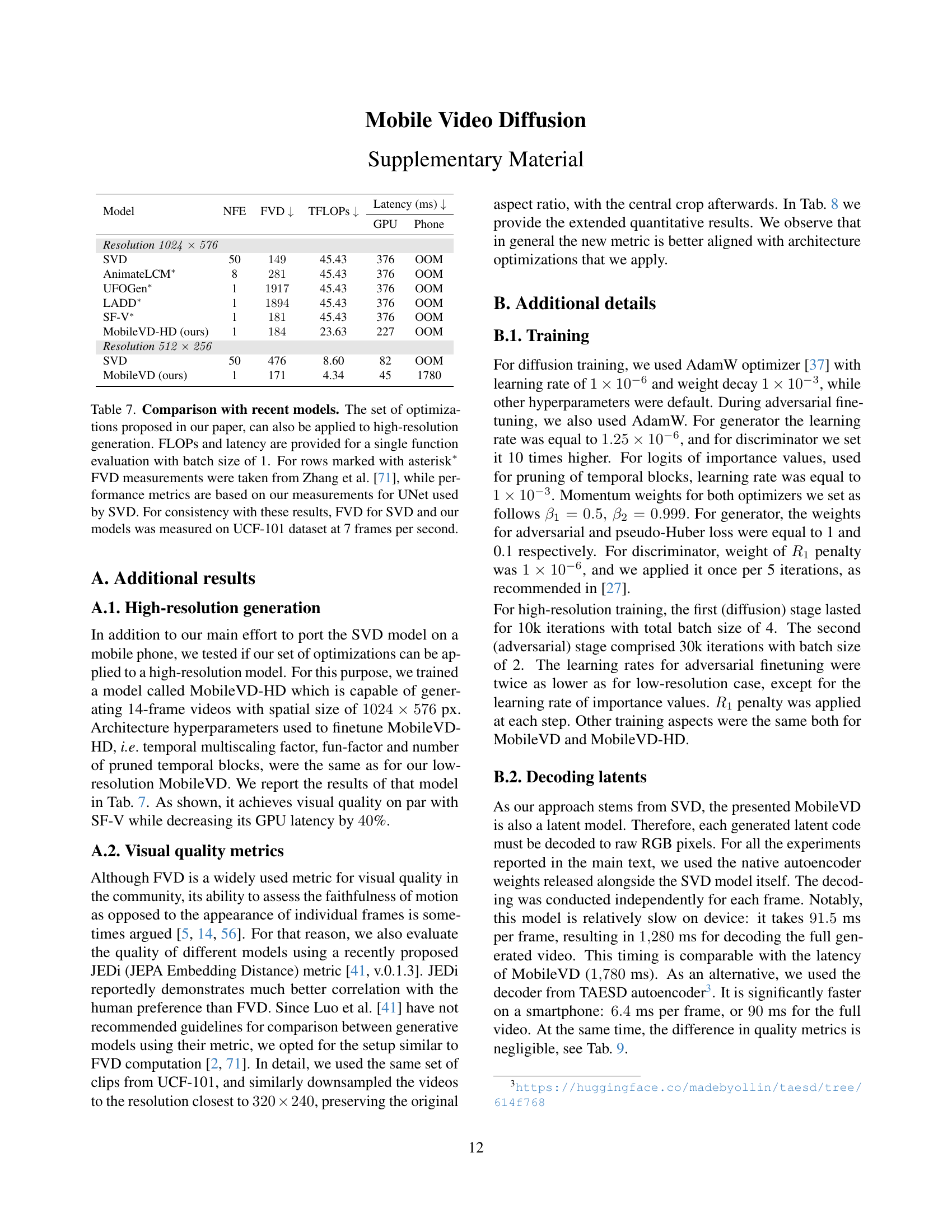

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of ‘channel funnels,’ a technique used to optimize the model’s efficiency. Channel funnels act as adaptors during training, reducing the model’s width (number of channels) and thus the number of parameters. This speeds up training without a significant impact on accuracy. Crucially, at inference time, the funnels are merged with the weight matrices, so there is no loss in accuracy or quality of the final output. The diagram visually shows the process, highlighting how the model’s width is reduced during training and restored during inference.

read the caption

Figure 3: Channel funnels. We show an example of channel funnels applied to a couple of layers within the model. At training time, funnels serve as adaptors reducing model width. At inference, they are merged with corresponding weight matrices without loss of quality.

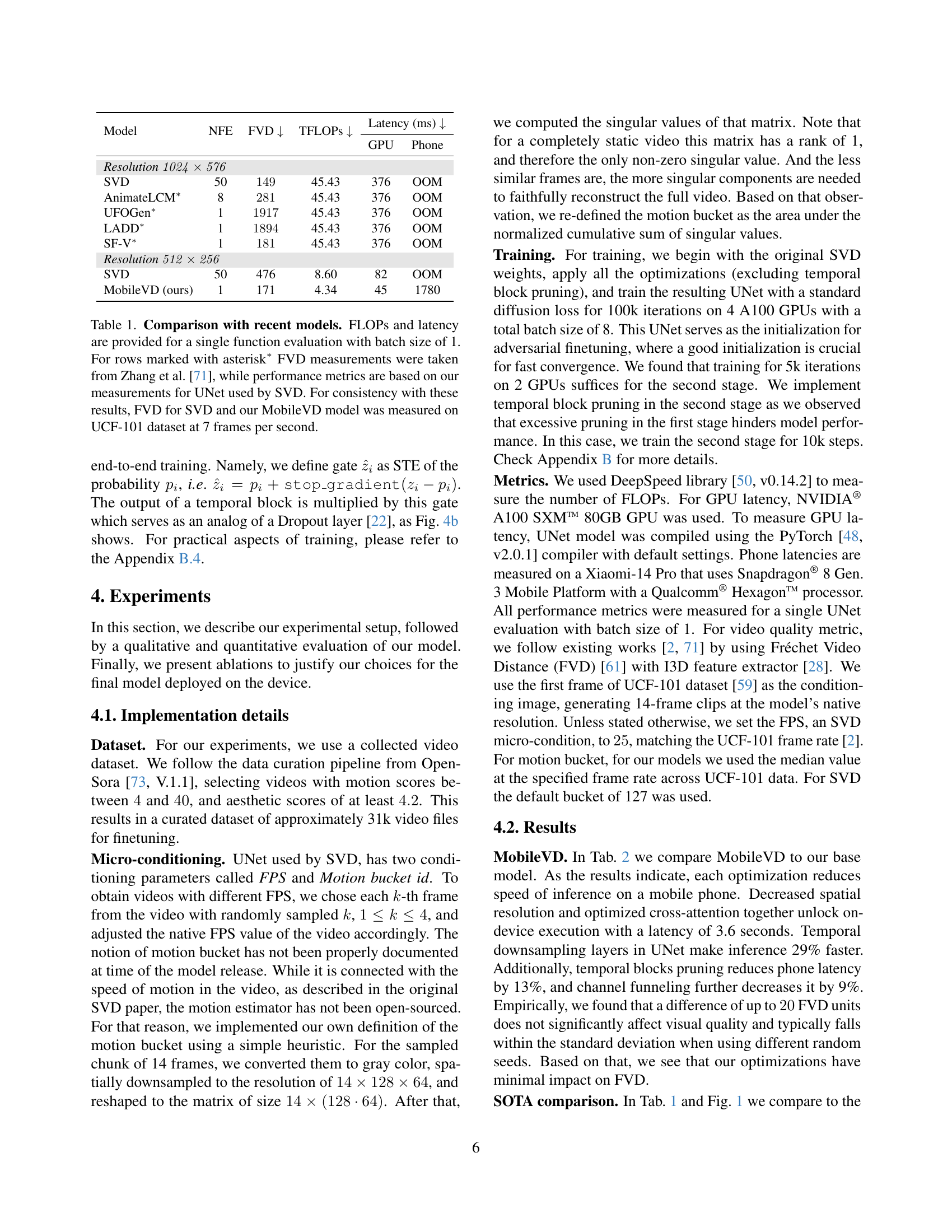

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of temporal blocks in Stable Video Diffusion (SVD). Panel (a) illustrates how the original SVD model incorporates temporal blocks to handle the temporal dynamics of videos. Each temporal block receives inputs from the spatial blocks, processes them through temporal layers, and then integrates the result with the spatial block output via a weighted sum, controlled by the parameter ‘a’, allowing for variable emphasis on spatial or temporal features.

read the caption

(a) Temporal blocks in the original architecture of SVD.

🔼 During training, a random binary gate (0 or 1) is applied to each temporal block. This gate determines whether the temporal block is active (gate=1) or inactive (gate=0) during that specific training iteration. This technique is used to perform a learnable pruning of temporal blocks where the network learns which temporal blocks are more important for generating high-quality videos. At inference time, only the most important temporal blocks (those with the highest learned importance scores) are used, resulting in a smaller and more efficient model.

read the caption

(b) A zero-one gate multiplier is sampled to each temporal block during training.

More on tables

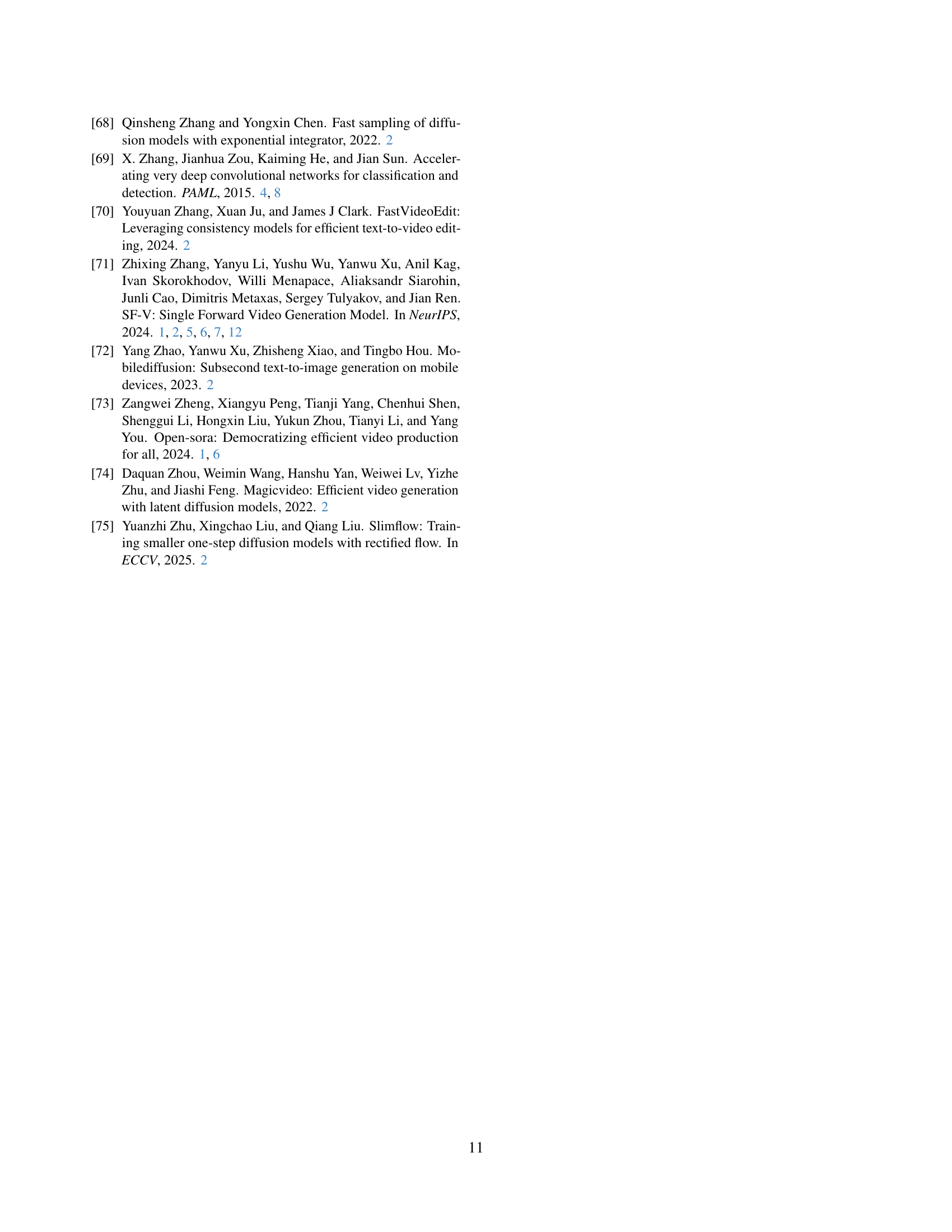

| Model | NFE | FVD ↓ | TFLOPs ↓ | GPU Latency (ms) ↓ | Phone Latency (ms) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution 1024x576 | |||||

| SVD | 50 | 149 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| AnimateLCM* | 8 | 281 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| UFOGen* | 1 | 1917 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| LADD* | 1 | 1894 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| SF-V* | 1 | 181 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| Resolution 512x256 | |||||

| SVD | 50 | 476 | 8.60 | 82 | OOM |

| MobileVD (ours) | 1 | 171 | 4.34 | 45 | 1780 |

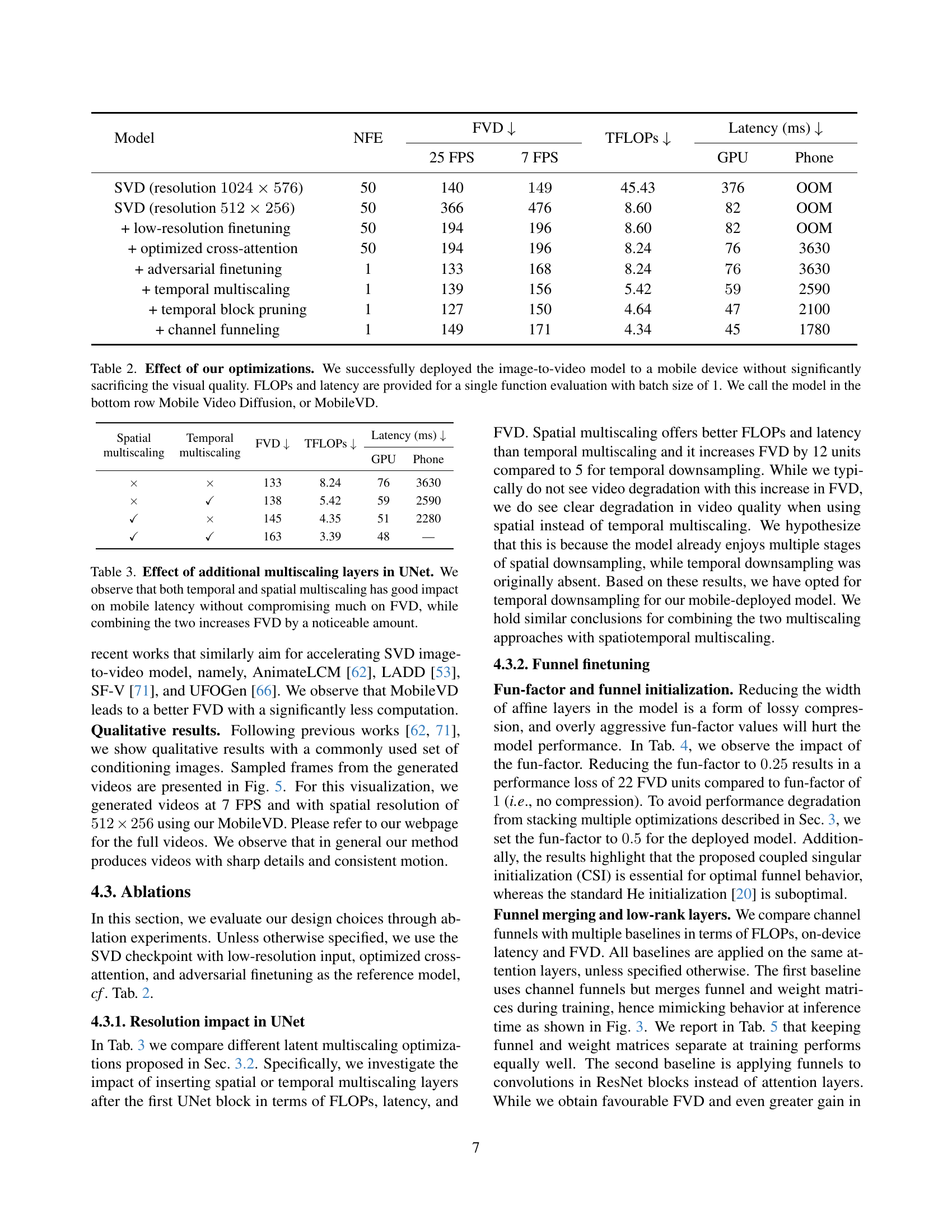

🔼 This table shows the impact of various optimizations on the performance and efficiency of a Stable Video Diffusion model adapted for mobile devices. The optimizations include lowering resolution, using optimized cross-attention, adversarial finetuning, temporal multiscaling, temporal block pruning, and channel funneling. The table shows the number of function evaluations (NFE), Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) values at both 25 frames per second (FPS) and 7 FPS, TeraFLOPS (TFLOPS), and latency in milliseconds (ms) on both a GPU and a mobile phone. The bottom row represents the final, optimized Mobile Video Diffusion (MobileVD) model.

read the caption

Table 2: Effect of our optimizations. We successfully deployed the image-to-video model to a mobile device without significantly sacrificing the visual quality. FLOPs and latency are provided for a single function evaluation with batch size of 1. We call the model in the bottom row Mobile Video Diffusion, or MobileVD.

| Model | NFE | FVD ↓ (25 FPS) | FVD ↓ (7 FPS) | TFLOPs ↓ | Latency (ms) ↓ (GPU) | Latency (ms) ↓ (Phone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVD (resolution 1024x576) | 50 | 140 | 149 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| SVD (resolution 512x256) | 50 | 366 | 476 | 8.60 | 82 | OOM |

| + low-resolution finetuning | 50 | 194 | 196 | 8.60 | 82 | OOM |

| + optimized cross-attention | 50 | 194 | 196 | 8.24 | 76 | 3630 |

| + adversarial finetuning | 1 | 133 | 168 | 8.24 | 76 | 3630 |

| + temporal multiscaling | 1 | 139 | 156 | 5.42 | 59 | 2590 |

| + temporal block pruning | 1 | 127 | 150 | 4.64 | 47 | 2100 |

| + channel funneling | 1 | 149 | 171 | 4.34 | 45 | 1780 |

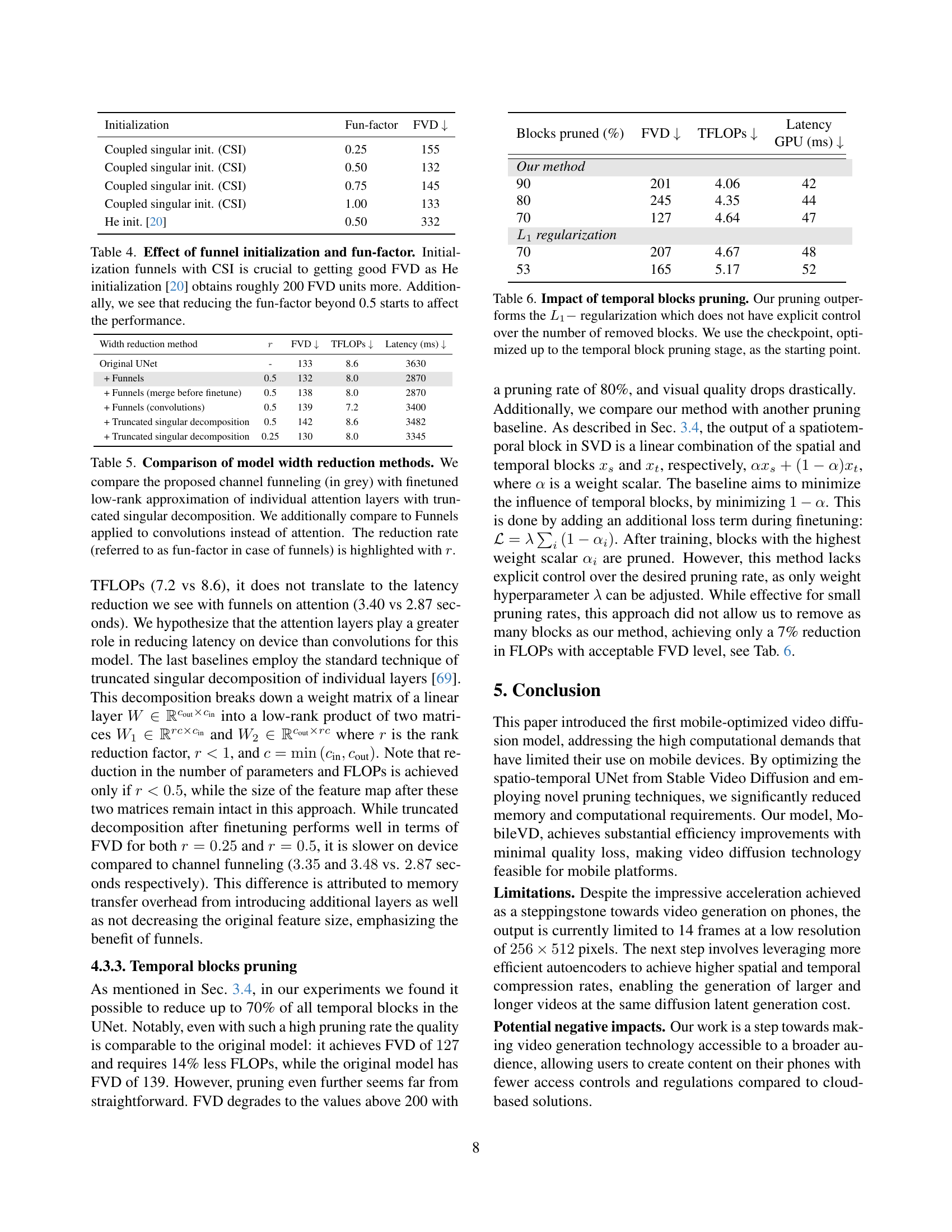

🔼 This table presents ablation study results on the impact of using multi-scale representations within the UNet architecture on mobile video diffusion model performance. It shows the effects of adding either spatial or temporal downsampling layers in the UNet, or both. The results are measured by FID (Fréchet Inception Distance) and TFLOPs, reflecting the trade-off between image quality and computational efficiency. The key takeaway is that while either spatial or temporal multi-scaling improves performance on mobile devices, combining both methods leads to a noticeable drop in image quality.

read the caption

Table 3: Effect of additional multiscaling layers in UNet. We observe that both temporal and spatial multiscaling has good impact on mobile latency without compromising much on FVD, while combining the two increases FVD by a noticeable amount.

| Spatial multiscaling | Temporal multiscaling | FVD ↓ | TFLOPs ↓ | Latency (ms) ↓ | Latency (ms) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| × | × | 133 | 8.24 | 76 | 3630 |

| × | ✓ | 138 | 5.42 | 59 | 2590 |

| ✓ | × | 145 | 4.35 | 51 | 2280 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 163 | 3.39 | 48 | — |

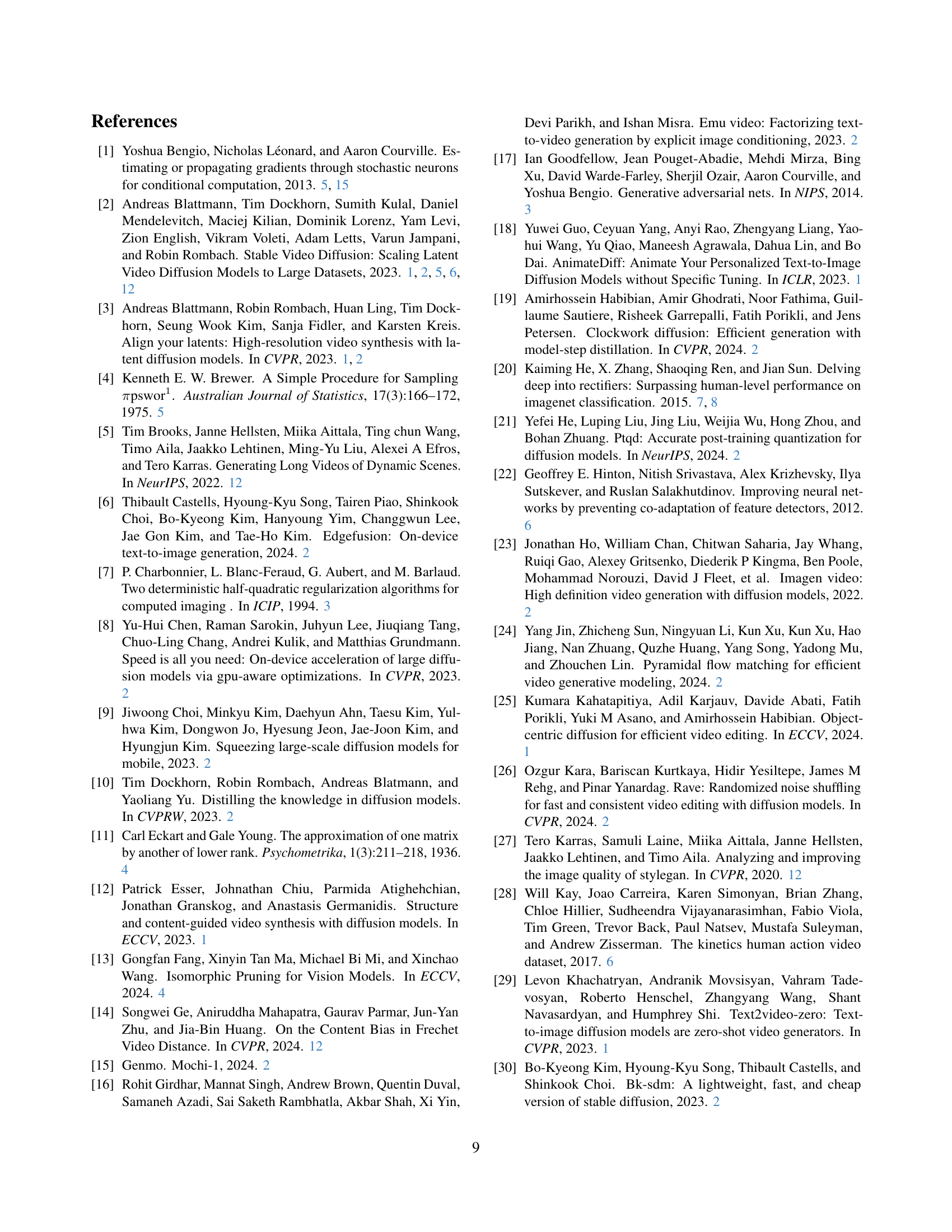

🔼 This table investigates the impact of two hyperparameters—channel funnel initialization methods (Coupled Singular Initialization (CSI) vs. He initialization) and the funnel factor—on the Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) metric. The results demonstrate that using CSI is significantly better than He initialization for achieving lower FVD scores. Furthermore, decreasing the funnel factor below 0.5 leads to a decline in model performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Effect of funnel initialization and fun-factor. Initialization funnels with CSI is crucial to getting good FVD as He initialization [20] obtains roughly 200 FVD units more. Additionally, we see that reducing the fun-factor beyond 0.5 starts to affect the performance.

| Initialization Method | Fun-factor | FVD ↓ |

|---|---|---|

| Coupled singular init. (CSI) | 0.25 | 155 |

| Coupled singular init. (CSI) | 0.50 | 132 |

| Coupled singular init. (CSI) | 0.75 | 145 |

| Coupled singular init. (CSI) | 1.00 | 133 |

| He init. [20] | 0.50 | 332 |

🔼 This table compares different methods for reducing the width of neural network layers, aiming to improve model efficiency. It contrasts channel funneling (the proposed method), finetuned low-rank approximation of attention layers using truncated singular value decomposition, and channel funneling applied to convolutional layers instead of attention layers. The ‘fun-factor’, representing the reduction rate, is indicated for channel funneling.

read the caption

Table 5: Comparison of model width reduction methods. We compare the proposed channel funneling (in grey) with finetuned low-rank approximation of individual attention layers with truncated singular decomposition. We additionally compare to Funnels applied to convolutions instead of attention. The reduction rate (referred to as fun-factor in case of funnels) is highlighted with r𝑟ritalic_r.

| Width reduction method | r | FVD ↓ | TFLOPs ↓ | Latency (ms) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original UNet | - | 133 | 8.6 | 3630 |

| + Funnels | 0.5 | 132 | 8.0 | 2870 |

| + Funnels (merge before finetune) | 0.5 | 138 | 8.0 | 2870 |

| + Funnels (convolutions) | 0.5 | 139 | 7.2 | 3400 |

| + Truncated singular decomposition | 0.5 | 142 | 8.6 | 3482 |

| + Truncated singular decomposition | 0.25 | 130 | 8.0 | 3345 |

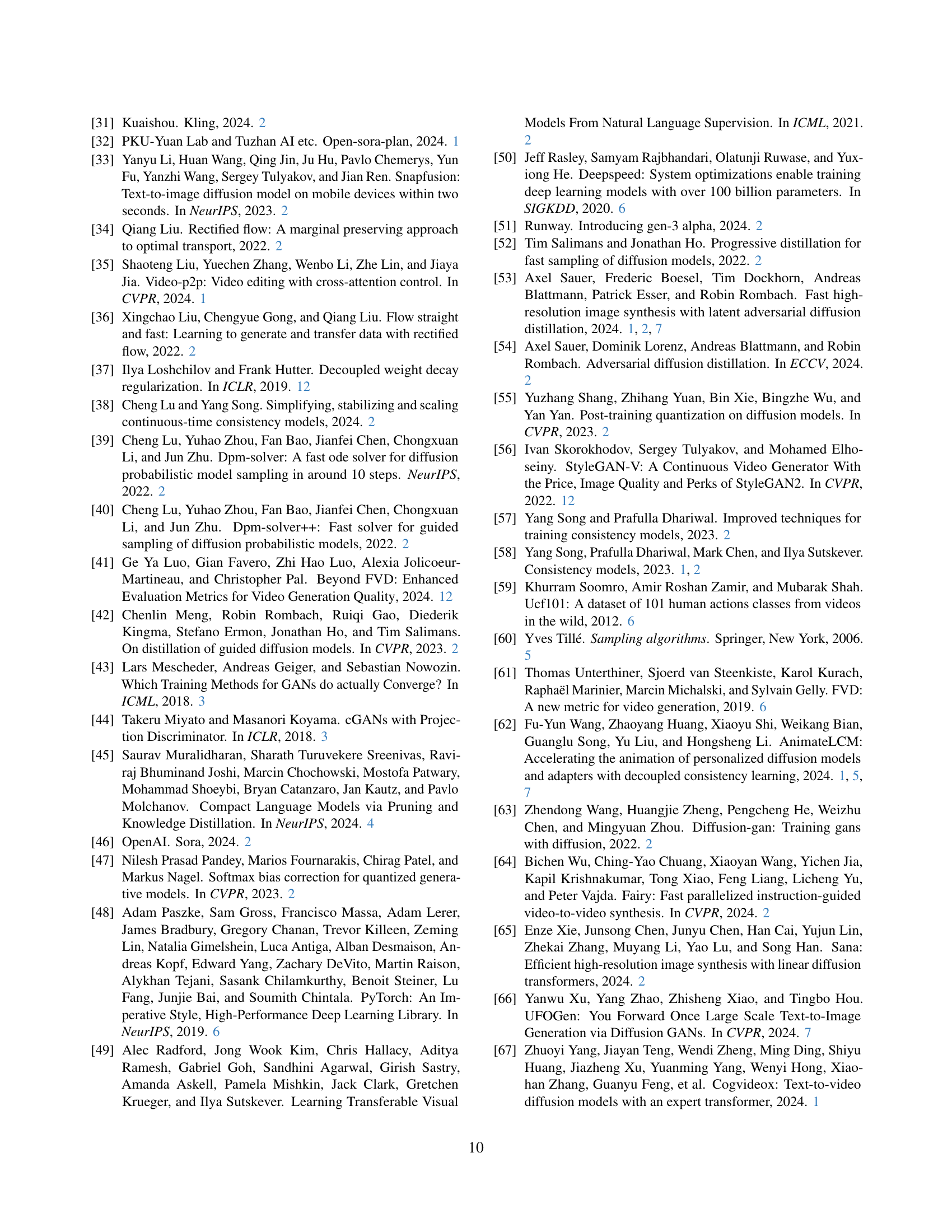

🔼 This table compares the performance of different temporal block pruning methods. Specifically, it shows how a learnable pruning technique outperforms L1 regularization, which lacks explicit control over the number of pruned blocks. The experiment starts with a model optimized up to the temporal block pruning stage. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in reducing computational cost while maintaining model performance.

read the caption

Table 6: Impact of temporal blocks pruning. Our pruning outperforms the L1−limit-fromsubscript𝐿1L_{1}-italic_L start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT - regularization which does not have explicit control over the number of removed blocks. We use the checkpoint, optimized up to the temporal block pruning stage, as the starting point.

| Blocks pruned (%) | FVD ↓ | TFLOPs ↓ | Latency GPU (ms) ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Our method | |||

| 90 | 201 | 4.06 | 42 |

| 80 | 245 | 4.35 | 44 |

| 70 | 127 | 4.64 | 47 |

| L1 regularization | |||

| 70 | 207 | 4.67 | 48 |

| 53 | 165 | 5.17 | 52 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed MobileVD model with several state-of-the-art video generation models. It includes the number of function evaluations (NFE), Fréchet Video Distance (FVD), TeraFLOPs (TFLOPS), and latency (in milliseconds) on both GPU and mobile phone. The comparison is done for both high-resolution (1024x576) and low-resolution (512x256) settings. Note that FVD values marked with an asterisk (*) were obtained from an external source (Zhang et al., 2024), while the other performance metrics are based on the authors’ measurements of the UNet used in Stable Video Diffusion (SVD). To ensure consistency, the FVD for SVD and MobileVD was measured on the UCF-101 dataset at 7 frames per second.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison with recent models. The set of optimizations proposed in our paper, can also be applied to high-resolution generation. FLOPs and latency are provided for a single function evaluation with batch size of 1. For rows marked with asterisk∗ FVD measurements were taken from Zhang et al. [71], while performance metrics are based on our measurements for UNet used by SVD. For consistency with these results, FVD for SVD and our models was measured on UCF-101 dataset at 7 frames per second.

| Model | NFE | FVD ↓ | TFLOPs ↓ | Latency (ms) ↓ GPU | Latency (ms) ↓ Phone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution 1024x576 | |||||

| SVD | 50 | 149 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| AnimateLCM* | 8 | 281 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| UFOGen* | 1 | 1917 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| LADD* | 1 | 1894 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| SF-V* | 1 | 181 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM |

| MobileVD-HD (ours) | 1 | 184 | 23.63 | 227 | OOM |

| Resolution 512x256 | |||||

| SVD | 50 | 476 | 8.60 | 82 | OOM |

| MobileVD (ours) | 1 | 171 | 4.34 | 45 | 1780 |

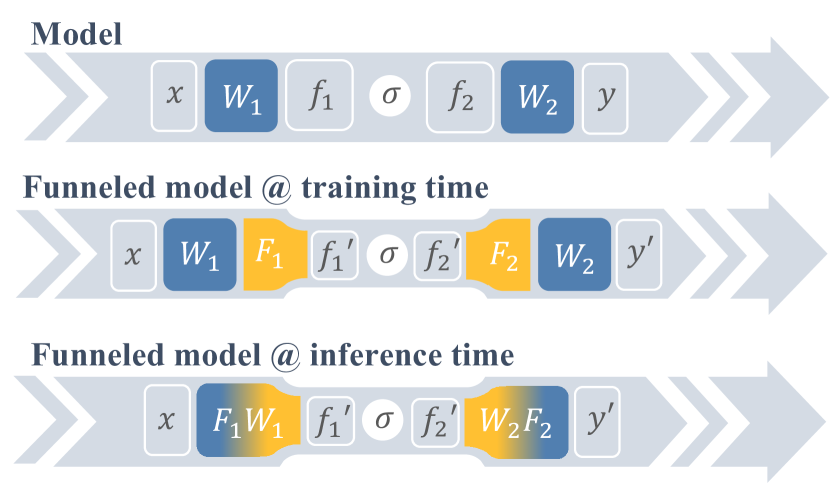

🔼 This table presents a quantitative analysis of the impact of various optimization techniques on the performance of a mobile video diffusion model. It compares the original Stable Video Diffusion (SVD) model with several optimized versions, showcasing the trade-offs between computational cost (measured in FLOPs and latency on both GPU and mobile phone), and visual quality (evaluated using the Fréchet Video Distance (FVD) and JEDi metrics). The optimizations include: low-resolution finetuning, optimized cross-attention, adversarial finetuning, temporal multi-scaling, temporal block pruning, and channel funneling. The table highlights the significant reduction in computational cost achieved by the MobileVD model (the final optimized version) while maintaining relatively good visual quality, demonstrating its suitability for mobile deployment. A high-resolution variant, MobileVD-HD, is also included, showcasing the scalability of the optimizations.

read the caption

Table 8: Effect of our optimizations. We successfully deployed the image-to-video model to a mobile device without significantly sacrificing the visual quality. FLOPs and latency are provided for a single function evaluation with batch size of 1. We call the model in the bottom row Mobile Video Diffusion, or MobileVD. The model trained with the same hyperparameters but intended for high-resolution generations is referred to as MobileVD-HD.

| Model | NFE | FVD ↓ (25 FPS) | FVD ↓ (7 FPS) | JEDi ↓ (25 FPS) | JEDi ↓ (7 FPS) | TFLOPs ↓ | Latency (ms) ↓ (GPU) | Latency (ms) ↓ (Phone) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | |||||||||

| SVD | 50 | 140 | 149 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 45.43 | 376 | OOM | |

| MobileVD-HD | 1 | 126 | 184 | 0.96 | 1.75 | 23.63 | 227 | OOM | |

| Resolution | |||||||||

| SVD | 50 | 366 | 476 | 1.05 | 1.14 | 8.60 | 82 | OOM | |

| + low-resolution finetuning | 50 | 194 | 196 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 8.60 | 82 | OOM | |

| + optimized cross-attention | 50 | 194 | 196 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 8.24 | 76 | 3630 | |

| + adversarial finetuning | 1 | 133 | 168 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 8.24 | 76 | 3630 | |

| + temporal multiscaling | 1 | 139 | 156 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 5.42 | 59 | 2590 | |

| + temporal block pruning | 1 | 127 | 150 | 0.97 | 1.32 | 4.64 | 47 | 2100 | |

| + channel funneling | 1 | 149 | 171 | 1.07 | 1.21 | 4.34 | 45 | 1780 |

🔼 This table compares the performance of two different decoders used to convert latent codes generated by the MobileVD model into actual RGB video frames. It shows that the TAESD decoder is significantly faster for on-device processing compared to the original decoder from SVD, while maintaining virtually identical visual quality as measured by the FVD and JEDi metrics. This indicates that the TAESD decoder is a suitable and more efficient alternative for mobile applications.

read the caption

Table 9: Impact of latent decoder. While being significantly faster on device, decoder from TAESD has little to no impact on visual quality as measured by FVD and JEDi.

Full paper#