↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current text-to-image models struggle to generate detailed visual narratives with effective control over character appearances and interactions, especially in multi-character scenes. This paper tackles this limitation by proposing the novel task of customized manga generation, focusing on creating manga images with multiple characters dynamically adapting to textual descriptions, altering expressions, poses, and actions as the narrative unfolds. The task also includes managing dialog layouts to achieve vivid and expressive manga panels.

To address this challenge, the authors introduce DiffSensei, a novel framework that integrates a diffusion-based image generator with a multimodal large language model (MLLM). The MLLM acts as a text-compatible identity adapter, allowing for seamless and dynamic adjustments to character features based on textual cues. DiffSensei also incorporates masked attention injection for precise layout control and a dialog embedding technique for managing dialog placement. The framework is evaluated on MangaZero, a large-scale dataset specifically designed for this task, demonstrating superior performance compared to existing models and significant advancements in text-adaptable character customization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision and natural language processing as it introduces a novel framework for customized manga generation, bridging multi-modal LLMs and diffusion models. It addresses the limitations of existing methods in controlling character appearances and interactions, paving the way for more expressive and dynamic visual storytelling. The proposed MangaZero dataset is also a significant contribution, providing valuable resources for future research in this area. This work is highly relevant to the current trends of combining large language models and diffusion models for image generation and is likely to stimulate further innovation and research in customized visual narrative generation.

Visual Insights#

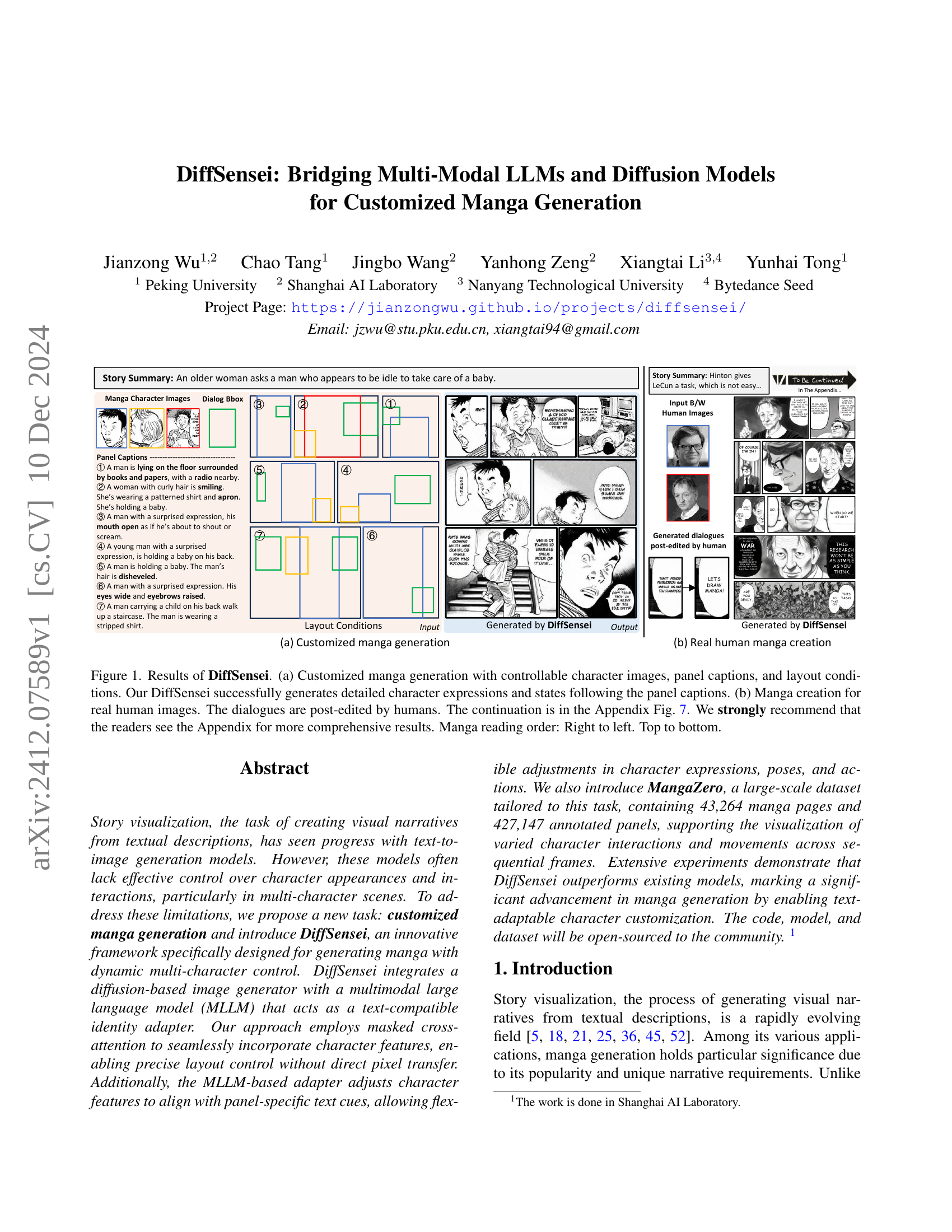

🔼 This figure showcases the capabilities of DiffSensei in generating manga. Panel (a) demonstrates customized manga generation where users control character appearances, panel captions, and layout. DiffSensei generates manga panels with accurate character expressions and poses that align with the given captions. Panel (b) shows a comparison using real human images; note that the dialogue in this panel was post-edited by a human. The full results and continuation of panel (b) can be found in Appendix Figure 7. Manga should be read from right-to-left and top-to-bottom.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of DiffSensei. (a) Customized manga generation with controllable character images, panel captions, and layout conditions. Our DiffSensei successfully generates detailed character expressions and states following the panel captions. (b) Manga creation for real human images. The dialogues are post-edited by humans. The continuation is in the Appendix Fig. 7. We strongly recommend that the readers see the Appendix for more comprehensive results. Manga reading order: Right to left. Top to bottom.

| Dataset | Type | Resolution | #Series | #Stories | #Panels | Caption | Character | Dialog | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PororoSV [18] | Animation | Fix | 1 | 15,336 | 73,665 | ✓ | × | × | 2003-2016 |

| FlintstonesSV [10] | Animation | Fix | 1 | 25,184 | 122,560 | ✓ | ✓ | × | 1960-1966 |

| StorySalon [21] | Animation | Fix | 446 | 18,255 | 159,778 | ✓ | × | × | YouTube |

| StoryStream [45] | Animation | Fix | 3 | 12,614 | 257,850 | ✓ | × | × | 1939-2013 |

| Manga109 [2] | B/W Manga | Vary | 109 | 10,602 | 103,850 | × | ✓ | ✓ | 1970-2010 |

| MangaZero | B/W Manga | Vary | 48 | 43,264 | 427,147 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1974-2024 |

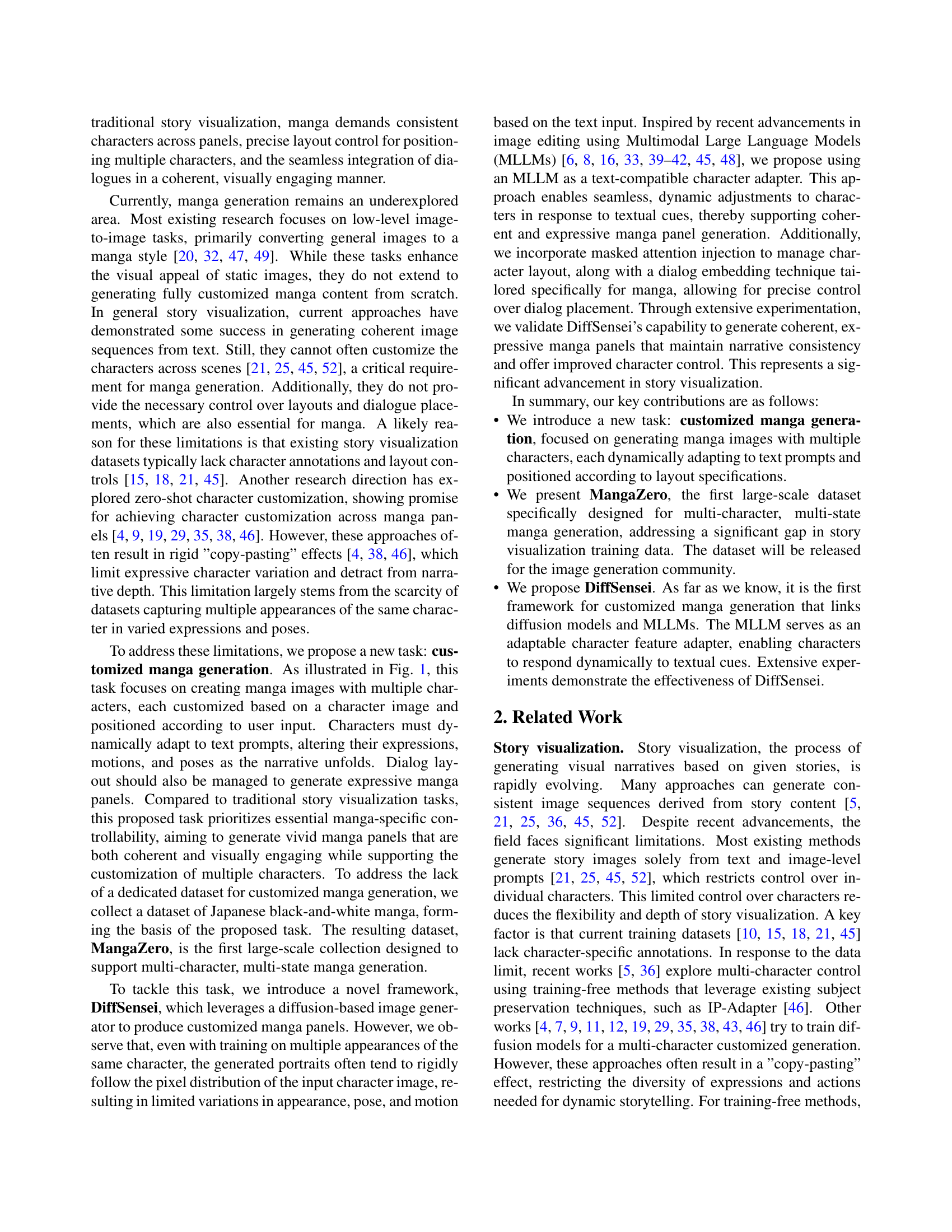

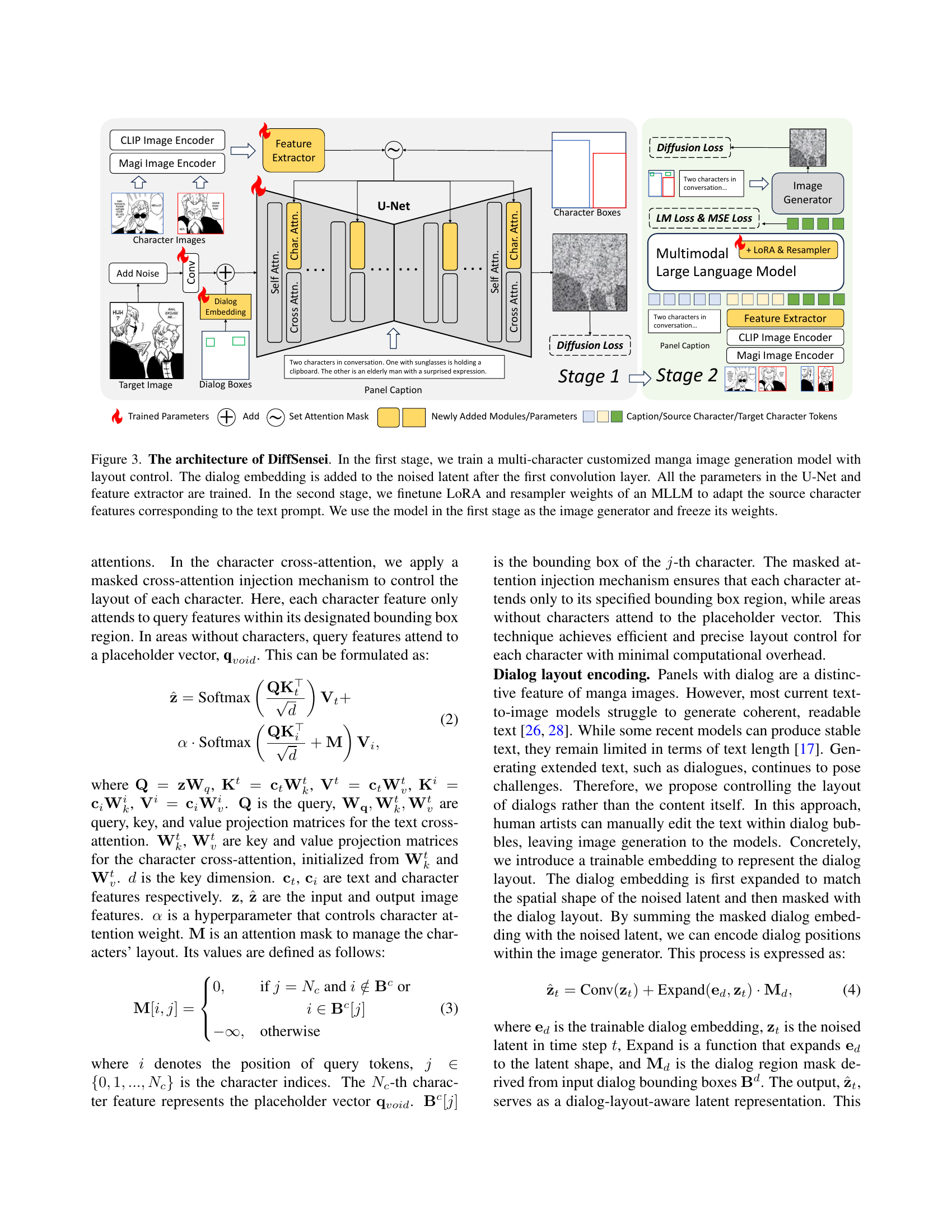

🔼 This table compares the MangaZero dataset with other publicly available datasets used for story visualization and manga generation. Key characteristics compared include the type of visual media (animation or manga), image resolution, the number of series, stories (manga pages in MangaZero), and panels (individual frames in MangaZero). Annotation details such as the presence of captions, character IDs, and dialogue annotations are also shown. The table highlights MangaZero’s size and comprehensiveness in terms of annotations and the time period of the included manga series.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison between MangaZero and related publically available datasets. A story is defined as a sequence of continuous images annotated consistently with character IDs. In MangaZero, a story means a manga page. A panel means a distinct story image, or called frame [45, 21]. Most series in MangaZero are still popular in 2024. Please see the Appendix for the dataset details.

In-depth insights#

Manga Generation#

The provided text focuses on “customized manga generation,” a novel task integrating multi-modal LLMs and diffusion models. Existing methods often struggle with precise control over character appearances and interactions, particularly in multi-character scenes. This new approach uses an MLLM as a text-compatible identity adapter, enabling dynamic adjustments to characters based on textual cues. This addresses the limitations of prior work, which often resulted in rigid “copy-pasting” effects and lacked dynamic character adaptation. A key contribution is the MangaZero dataset, a large-scale resource tailored for this task, containing diverse character interactions and layout controls. The framework, DiffSensei, demonstrates superior performance in generating coherent and expressive manga panels with text-adaptable character customization, marking a significant advancement in the field of story visualization and manga generation.

Multimodal LLMs#

Multimodal large language models (LLMs) represent a significant advancement in artificial intelligence, enabling systems to understand and generate information across various modalities, beyond text. These models are crucial for tasks like customized manga generation because they can seamlessly integrate textual descriptions with visual elements. By combining textual input with visual data, such as character images, LLMs provide a powerful mechanism to control character features dynamically. The models adjust character expressions, poses, and actions according to the story’s narrative, ensuring consistency and coherence across multiple panels. This is particularly valuable in manga, which requires maintaining consistent character representations throughout a story. Furthermore, multimodal LLMs enhance the generation process by offering precise control over layout. This enables the alignment of dialogues and characters’ positions with the text, creating a visually engaging and narratively consistent manga experience. The integration of LLMs with diffusion models, as demonstrated in the paper, showcases a synergistic approach where LLMs adapt character features while diffusion models generate the actual images. This results in high-quality, customized manga that adheres to textual prompts and specified visual constraints, overcoming the limitations of prior approaches.

Diffusion Models#

Diffusion models, a class of generative models, have revolutionized image synthesis. They work by gradually adding noise to an image until it becomes pure noise, then learning to reverse this process, generating images from noise. This approach allows for high-quality image generation and control over various aspects like style and resolution. Key advantages include their ability to create diverse and realistic outputs and the potential for fine-tuning to specific styles or datasets. However, challenges remain. Training these models is computationally expensive, requiring significant resources. Moreover, controlling specific aspects of the generated image, beyond broad features, remains an area of active research. The integration of diffusion models with other techniques, such as large language models, presents promising avenues for creating more complex and nuanced generative systems, as seen in applications like text-to-image generation and image editing.

MangaZero Dataset#

The MangaZero dataset represents a significant contribution to the field of AI-driven manga generation. Its creation directly addresses the scarcity of large-scale, high-quality datasets specifically tailored for multi-character, multi-state manga generation. This is crucial because existing datasets often lack the necessary annotations (character IDs, dialog boxes, layout specifications) required to train models capable of generating customized manga with dynamic character interactions. The dataset’s size (43,264 manga pages, 427,147 annotated panels) and inclusion of varied panel resolutions and character appearances allows for robust model training, enhancing the models’ ability to adapt and perform well in various scenarios. MangaZero’s focus on black-and-white manga streamlines the annotation process and also reflects the stylistic conventions of a significant portion of the manga market. The thorough annotation process, involving both automated and human verification steps, ensures high accuracy and consistency, creating a reliable foundation for future research in advanced manga generation techniques. This dataset is key to advancing the field beyond simple style transfer and into full-fledged, personalized manga creation.

DiffSensei Framework#

The DiffSensei framework represents a novel approach to customized manga generation, effectively bridging the gap between multimodal large language models (MLLMs) and diffusion models. Its core innovation lies in using an MLLM as a text-compatible identity adapter, enabling dynamic adjustments to character features based on textual cues within the manga narrative. This avoids the rigid “copy-pasting” effect often seen in other methods, allowing for more natural and expressive character variations. Further enhancing control, DiffSensei incorporates masked cross-attention injection for precise layout management, ensuring characters are positioned accurately according to the script and dialogue. The integration of dialog embedding further refines the panel generation process, enabling natural dialogue placement. The framework’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments using the MangaZero dataset, showcasing superior performance over existing manga generation models in terms of character customization, layout control, and narrative coherence. The open-sourcing of the code, model, and dataset encourages further research and development in this exciting area of AI-powered visual storytelling.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the three-step process used to create the MangaZero dataset. First, manga pages were downloaded from online manga websites. Second, these pages were automatically annotated using pre-trained models to identify panels, character bounding boxes, dialog boxes, and generate panel captions. Finally, human annotators reviewed and corrected the automatically generated character IDs to ensure accuracy and consistency.

read the caption

Figure 2: We construct MangaZero through three steps: 1) Download manga pages from the internet. 2) Annotate manga panels autonomously with pre-trained models. 3) Human calibration for the character ID annotation.

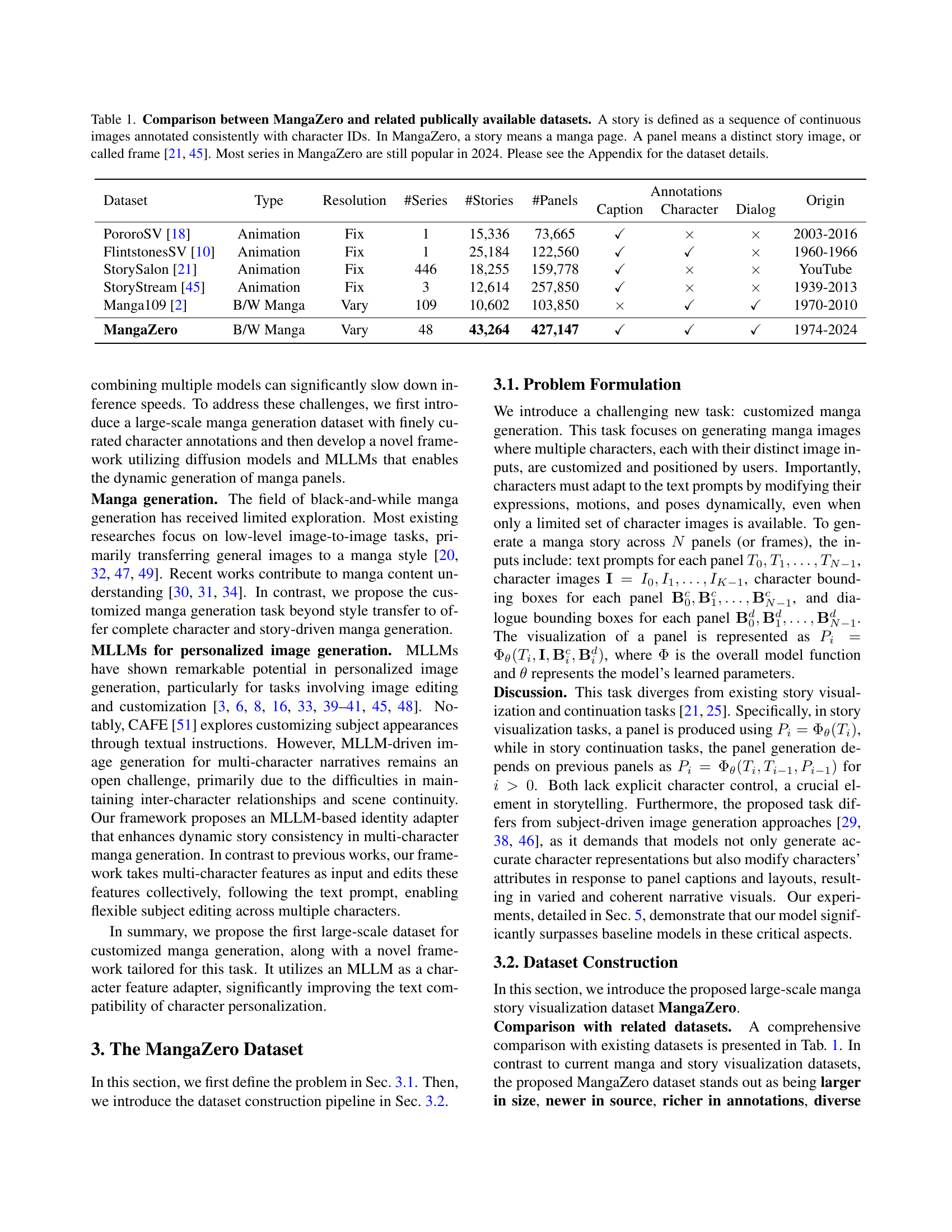

🔼 DiffSensei’s architecture is a two-stage process. Stage 1 trains a multi-character manga generation model with layout control using a diffusion model (U-Net). Dialog embeddings are incorporated early in the process. All U-Net and feature extractor parameters are learned. Stage 2 fine-tunes a multimodal large language model (MLLM) using LoRA and a resampler to adapt source character features to the text prompt. The stage 1 model serves as the image generator with fixed weights.

read the caption

Figure 3: The architecture of DiffSensei. In the first stage, we train a multi-character customized manga image generation model with layout control. The dialog embedding is added to the noised latent after the first convolution layer. All the parameters in the U-Net and feature extractor are trained. In the second stage, we finetune LoRA and resampler weights of an MLLM to adapt the source character features corresponding to the text prompt. We use the model in the first stage as the image generator and freeze its weights.

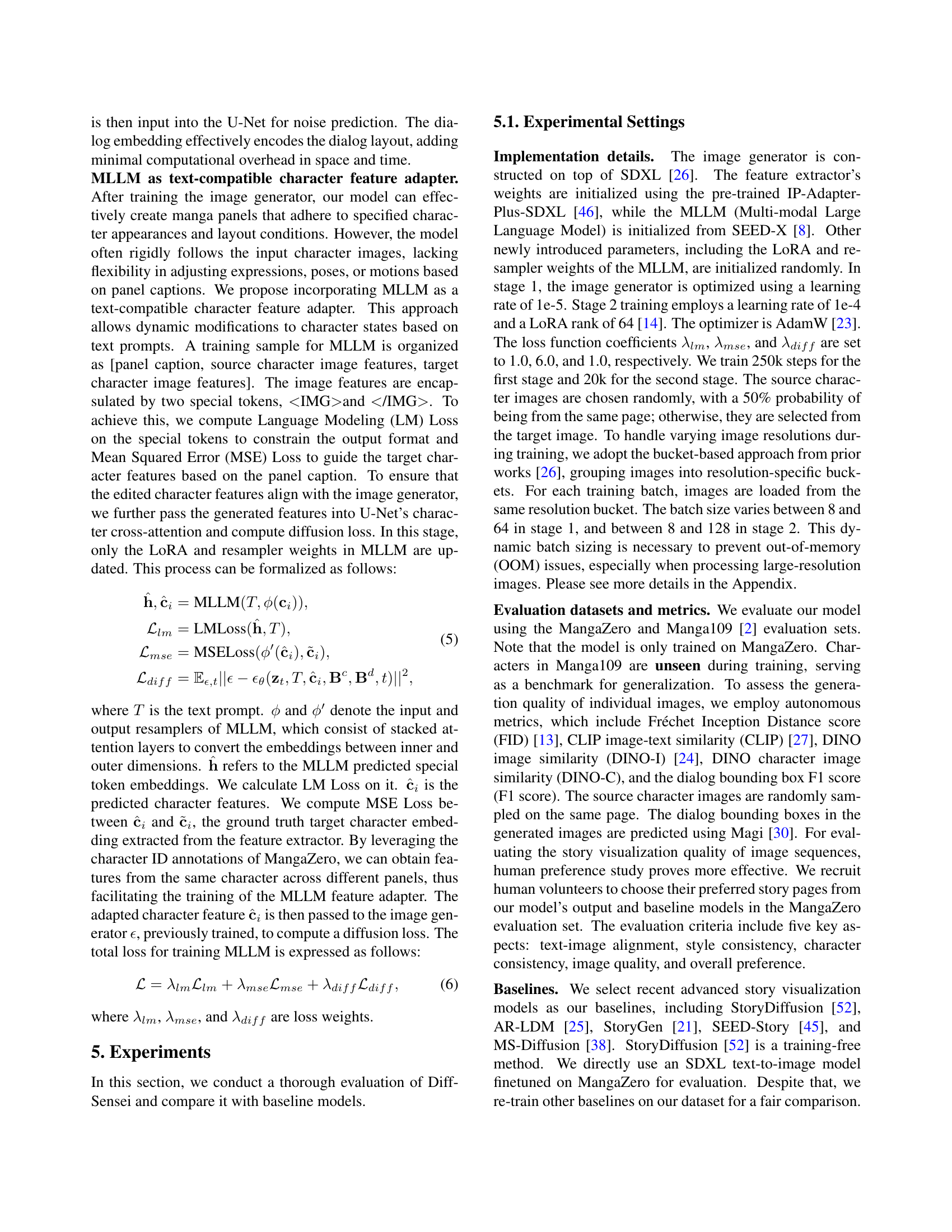

🔼 Figure 4 presents a qualitative comparison of DiffSensei against several baseline methods for customized manga generation. It highlights DiffSensei’s superior ability to maintain character consistency across generated panels while adhering to textual prompts. The figure showcases how DiffSensei successfully generates detailed manga panels that accurately reflect the specified text descriptions and layouts, capturing even subtle details highlighted in the panel captions. Baseline methods that utilize reference images (indicated by ‘*’) demonstrate limitations in character preservation and text-driven customization. Those re-trained with dialog embedding (’†’) show some improvement. The comparison underscores DiffSensei’s advantage in preserving character features and incorporating textual information for dynamic and detailed manga generation.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative comparison with baselines. Baselines followed by a “*” use reference images as input rather than character images. Methods marked by “†” means re-trained with dialog embedding. Our model excels at preserving the characters while following the text prompt. Our DiffSensei successively generates highlighted details in panel captions. Better viewed with zoom-in.

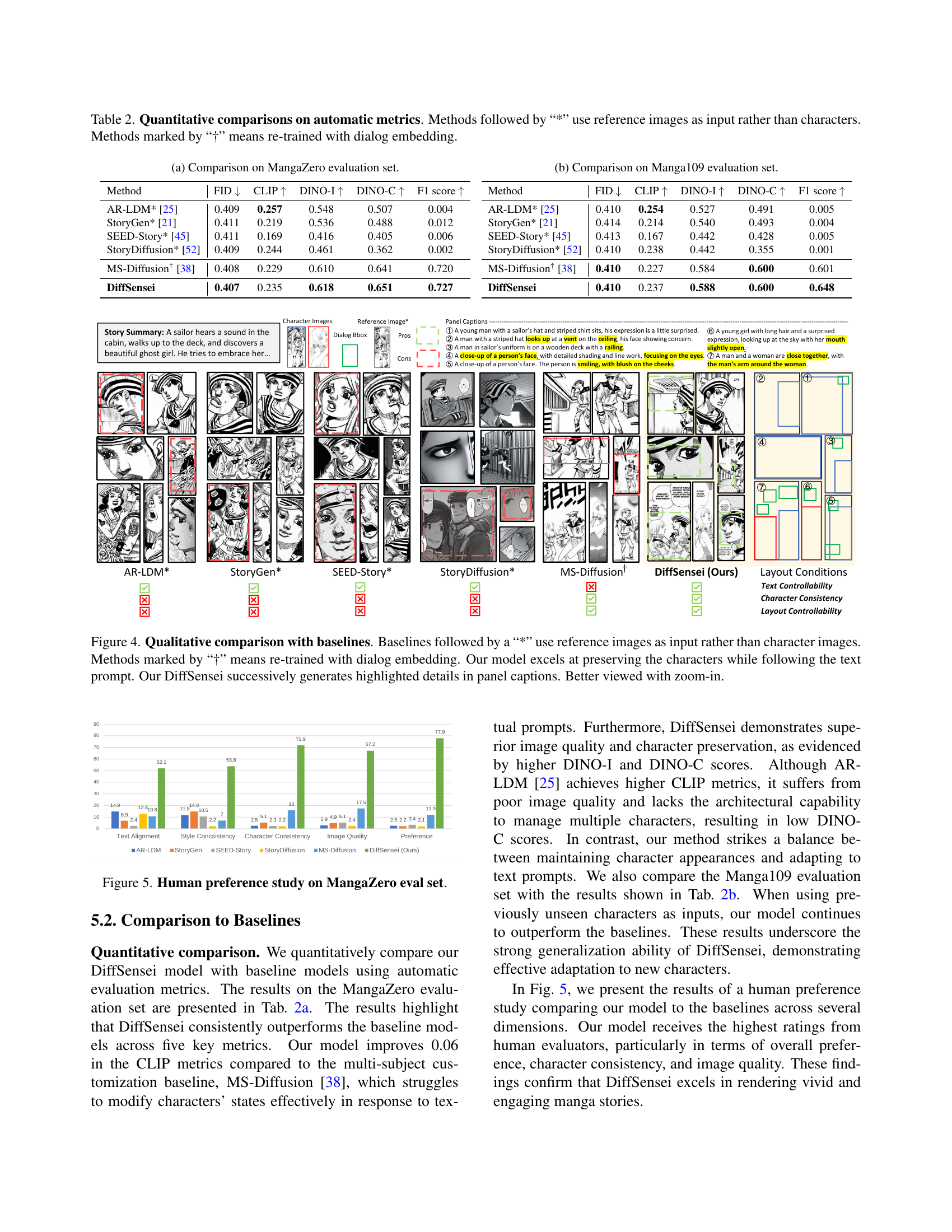

🔼 This bar chart presents the results of a user preference study conducted on the MangaZero evaluation set. The study compared DiffSensei’s generated manga pages against several baseline models across five key aspects: text-image alignment, style consistency, character consistency, image quality, and overall preference. Each bar represents the average score for a specific model on a particular aspect, offering a direct visual comparison of user perception of each model’s performance. This allows for easy identification of the model that most successfully fulfills the criteria of effective manga generation.

read the caption

Figure 5: Human preference study on MangaZero eval set.

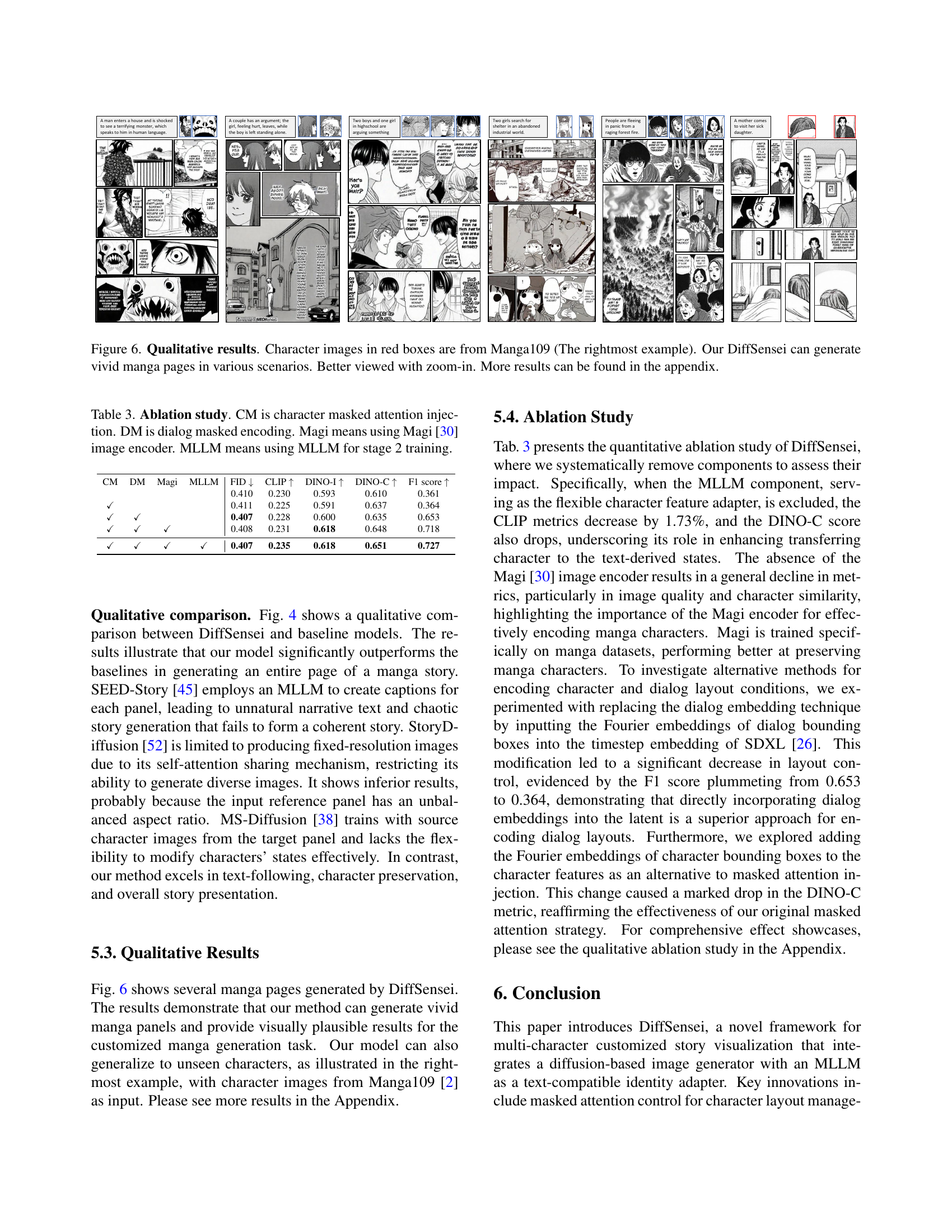

🔼 Figure 6 presents qualitative results demonstrating DiffSensei’s ability to generate manga pages across diverse scenarios. Character images within red boxes are sourced from the Manga109 dataset, highlighting the model’s capacity to incorporate external character styles. The figure showcases DiffSensei’s proficiency in generating detailed expressions and poses, aligning with narrative captions. For a more comprehensive collection of results, refer to the appendix.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative results. Character images in red boxes are from Manga109 (The rightmost example). Our DiffSensei can generate vivid manga pages in various scenarios. Better viewed with zoom-in. More results can be found in the appendix.

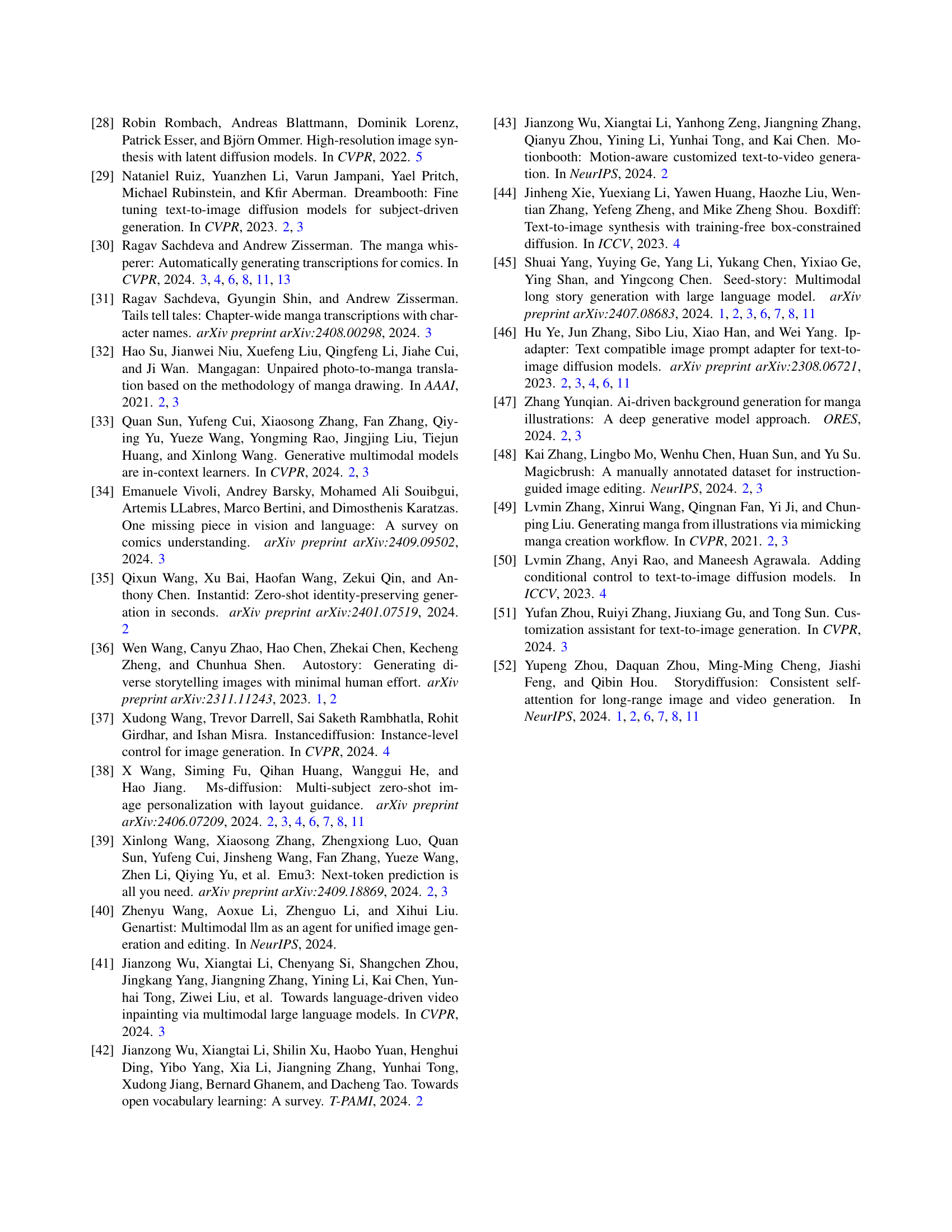

🔼 This figure shows a long manga story illustrating a fictional narrative about Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun, and Yoshua Bengio’s journey to create an AI model surpassing Transformers. The story depicts their challenges, self-doubt, eventual success, and subsequent Nobel Prize win, highlighting the power of perseverance in scientific endeavors.

read the caption

Figure 7: A complete long manga story about Hinton, LeCun, and Bengio winning the Nobel Prize.

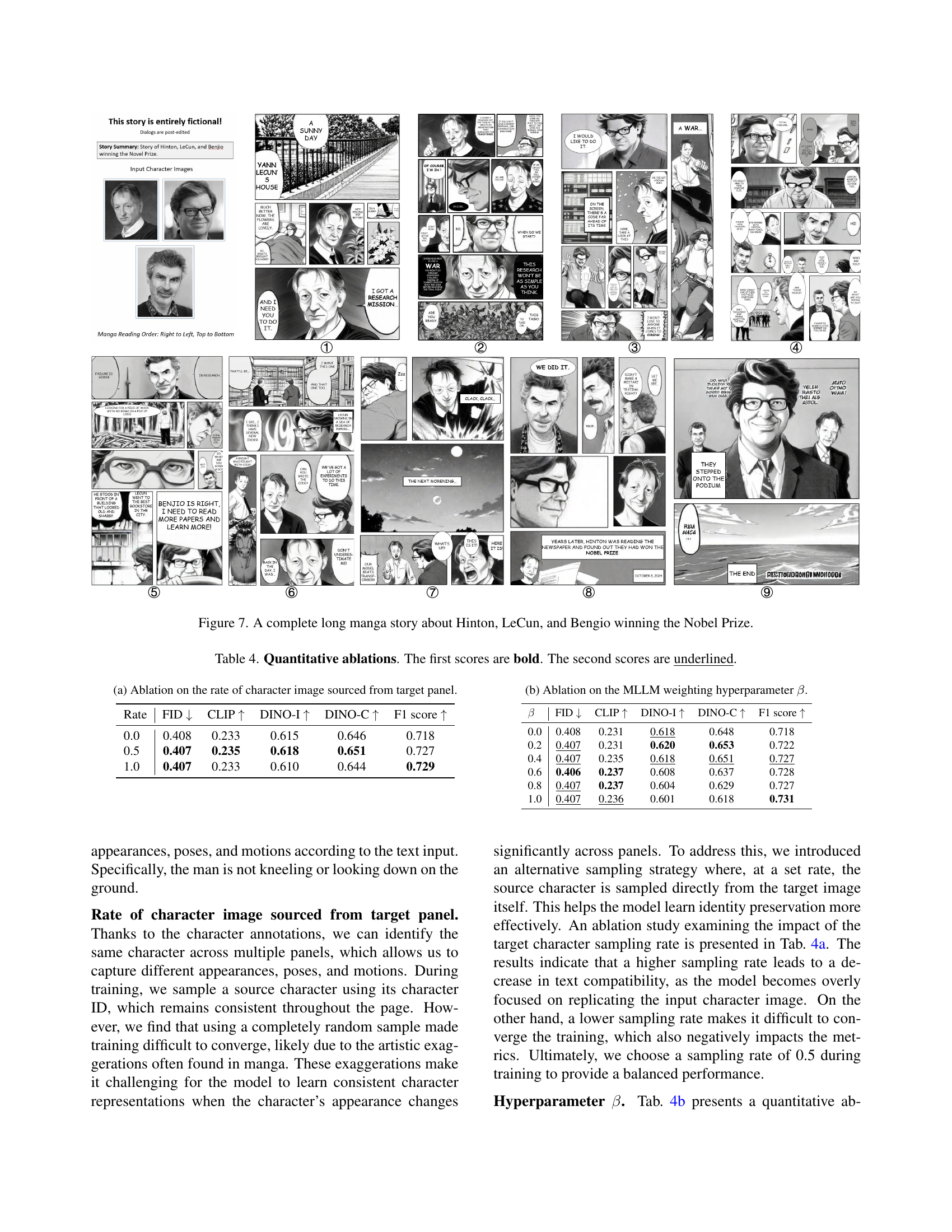

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of the proposed DiffSensei model against several baseline methods for customized manga generation. It showcases the strengths of DiffSensei in generating manga panels with multiple characters, each adapting dynamically to the textual prompts. The comparison highlights how DiffSensei outperforms baselines in preserving character identities, controlling layouts, and creating coherent narratives, even when handling unseen characters or adapting to text cues. The asterisk (*) indicates methods that utilize reference images as input instead of individual character images, while the dagger (†) marks methods that were retrained with dialog embedding.

read the caption

Figure 8: More qualitative comparisons with baselines. Baselines followed by a “*” use reference images as input rather than character images. Methods marked by “†” means re-trained with dialog embedding.

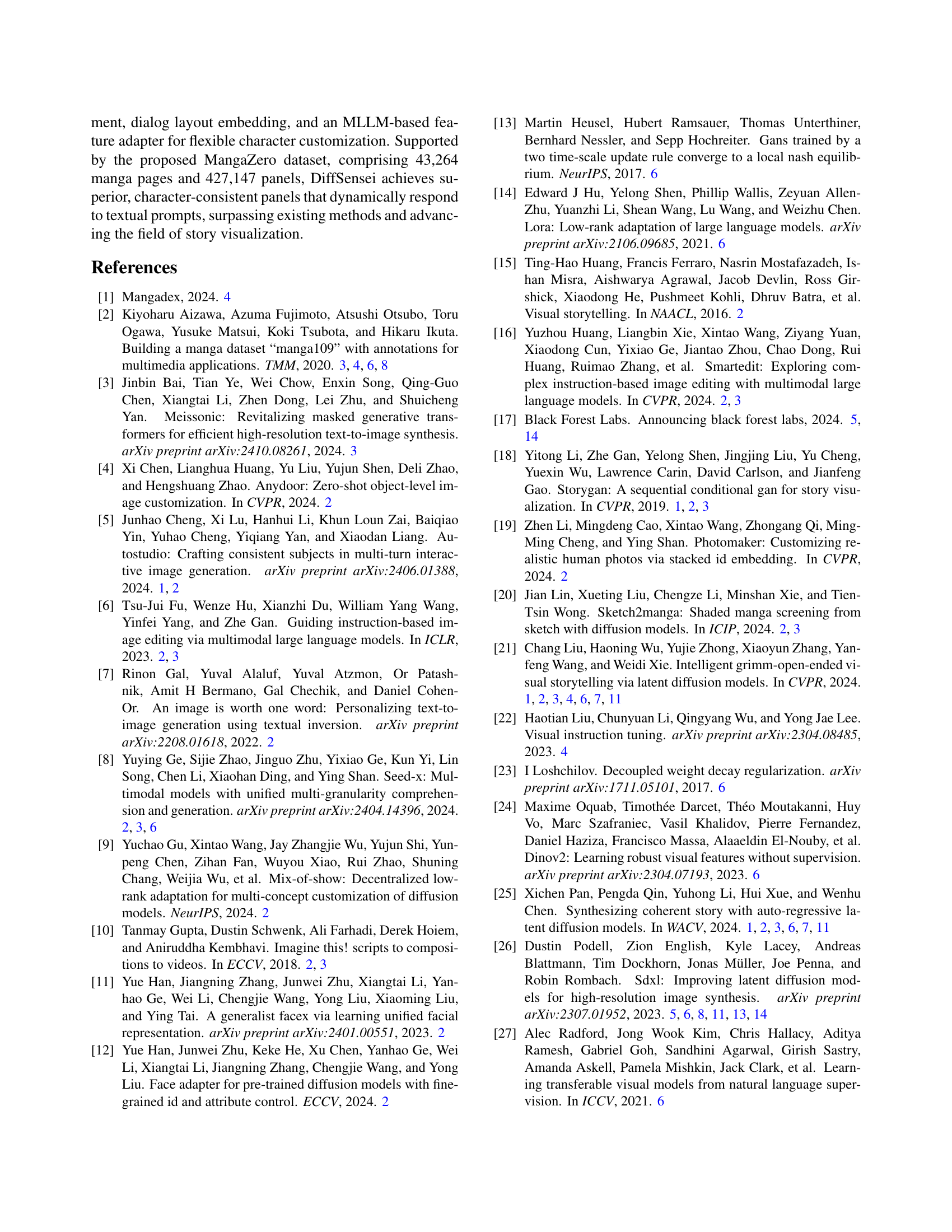

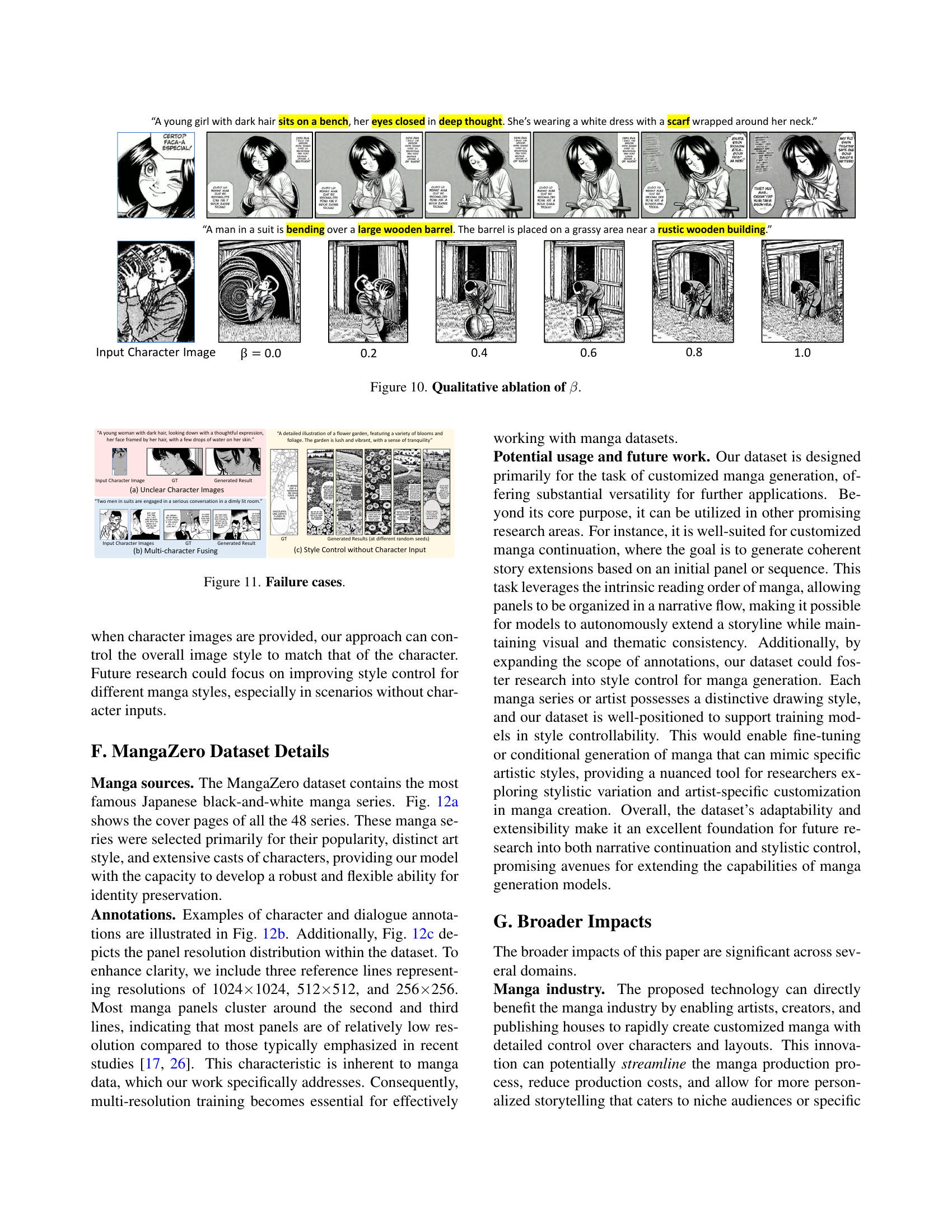

🔼 This ablation study investigates the individual contributions of different modules within the DiffSensei framework. It shows the impact of removing character masked attention injection (CM), dialog masked encoding (DM), the Magi [30] image encoder, or the second-stage Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) training. By systematically excluding each component, the figure demonstrates the effect on the model’s performance, measured by FID, CLIP, DINO-I, DINO-C, and F1-score. This provides insights into the relative importance of each component for achieving high-quality customized manga generation.

read the caption

Figure 9: Qualitative ablation of the proposed modules. CM is character masked attention injection. DM is dialog masked encoding. Magi means using Magi [30] image encoder. MLLM means using MLLM for stage 2 training.

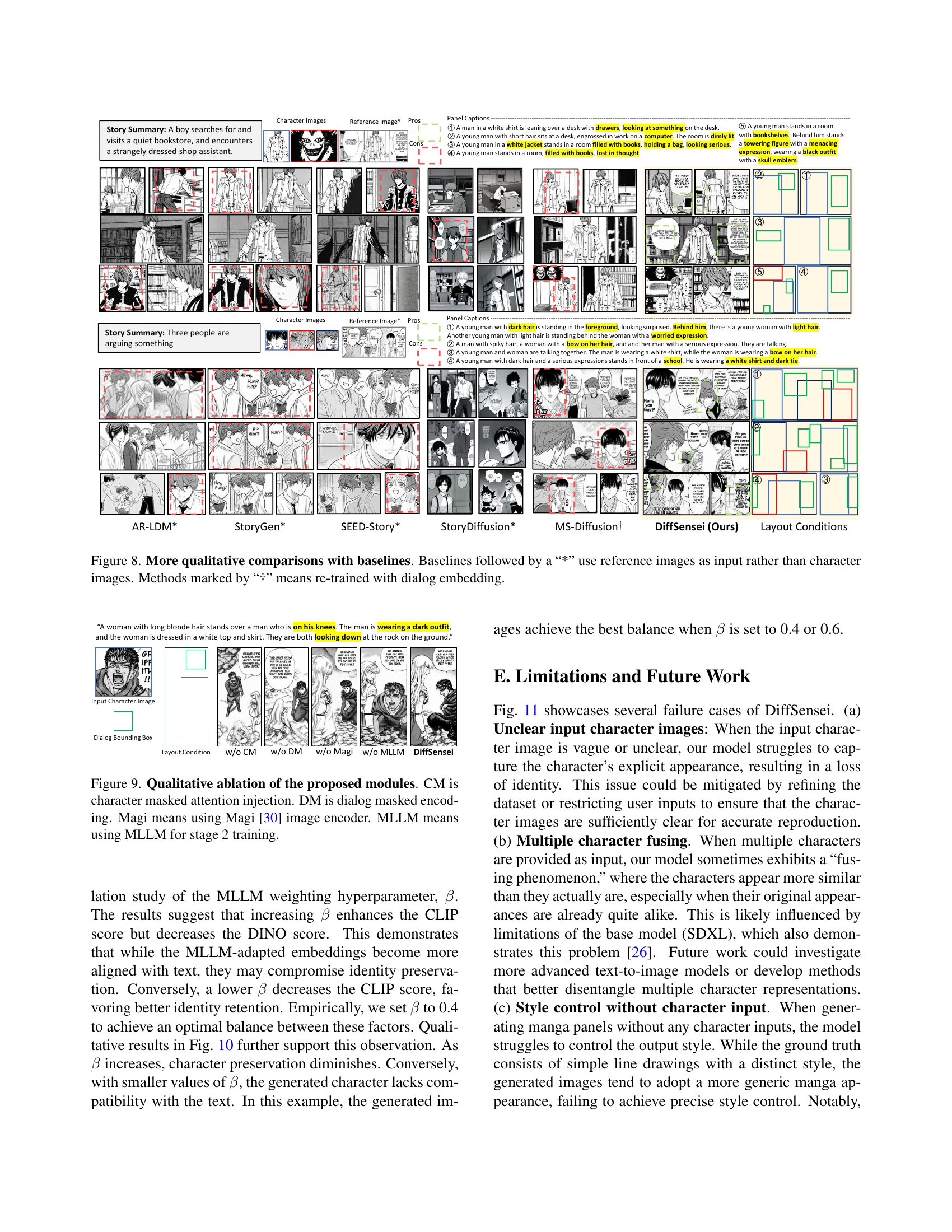

🔼 This figure shows an ablation study on the effect of the hyperparameter β (beta) in DiffSensei. Beta controls the weighting between original character features and MLLM-adapted features. The figure displays several manga panels generated with different values of β, demonstrating how altering this parameter impacts the balance between character identity preservation (low β) and text-driven customization (high β). Specifically, it illustrates the trade-off between maintaining the original visual characteristics of the character and allowing the model to dynamically adapt the appearance based on textual prompts. Qualitative differences in the generated manga are observed for each β value.

read the caption

Figure 10: Qualitative ablation of β𝛽\betaitalic_β.

🔼 This figure showcases several failure cases encountered by the DiffSensei model. Specifically, it highlights instances where the model struggles with (a) unclear input character images resulting in identity loss, (b) multiple character inputs causing character fusion, and (c) generating images in a consistent style without character input, leading to a generic manga style. These examples demonstrate the limitations of DiffSensei in handling various input conditions and highlight areas for future improvement.

read the caption

Figure 11: Failure cases.

🔼 This figure displays the covers of 48 different manga series included in the MangaZero dataset. These series were selected for their popularity, diverse art styles, and varied character casts, making them suitable for training a model on customized manga generation.

read the caption

(a) Covers of manga series.

🔼 This figure shows example annotations from the MangaZero dataset. The image displays several manga panels with bounding boxes drawn around individual characters and dialog bubbles. Each character bounding box is assigned a unique character ID for consistent tracking throughout a manga story, while dialog boxes highlight speech and thought bubbles within the panels. This demonstrates the detailed annotation work involved in creating MangaZero to support customized manga generation.

read the caption

(b) Examples of character and dialog annotations.

🔼 The figure shows the distribution of panel resolutions in the MangaZero dataset. The x-axis represents the width of the panel, and the y-axis represents the height. The plot shows a concentration of panels around 512x512 and 1024x1024 pixels, indicating a prevalence of these resolutions in the dataset.

read the caption

(c) Resolution distribution.

🔼 Figure 12 presents details of the MangaZero dataset, a crucial component of the research. It showcases three key aspects: (a) Cover images of the 48 different manga series included in the dataset, highlighting the diversity of styles and artistic choices. (b) Examples illustrating the annotations for characters and dialogue within the manga panels; this demonstrates the level of detail and precision in the dataset’s labeling. (c) A histogram visualizing the distribution of panel resolutions in the dataset. This graph indicates the range of panel sizes and their frequencies, showing whether the dataset has a balance of high- and low-resolution manga pages.

read the caption

Figure 12: Details of the MangaZero dataset.

🔼 Figure 13 presents examples of manga pages generated by the DiffSensei model. Each example shows the input (story summary, character images, dialog boxes, and layout conditions) alongside the corresponding output generated by the model. The examples showcase the model’s ability to generate manga panels with multiple characters, dynamic expressions and poses that adapt to textual cues, and precise control over dialog and layout. Part 1 suggests there are additional examples in subsequent figures.

read the caption

Figure 13: DiffSensei generated results with inputs (Part1).

🔼 This figure displays additional examples of manga pages generated by the DiffSensei model. The input includes story summaries, character images, dialog boxes, and layout conditions. Each row shows the input elements, the layout designed based on these conditions, and the final output generated by DiffSensei, illustrating the model’s ability to generate manga panels according to the given specifications and constraints. It highlights the framework’s capacity for generating multi-character scenes with detailed character interaction and expressions.

read the caption

Figure 14: DiffSensei generated results with inputs (Part2).

More on tables

| Method | FID ↓ | CLIP ↑ | DINO-I ↑ | DINO-C ↑ | F1 score ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR-LDM* [25] | 0.409 | 0.257 | 0.548 | 0.507 | 0.004 |

| StoryGen* [21] | 0.411 | 0.219 | 0.536 | 0.488 | 0.012 |

| SEED-Story* [45] | 0.411 | 0.169 | 0.416 | 0.405 | 0.006 |

| StoryDiffusion* [52] | 0.409 | 0.244 | 0.461 | 0.362 | 0.002 |

| MS-Diffusion† [38] | 0.408 | 0.229 | 0.610 | 0.641 | 0.720 |

| DiffSensei | 0.407 | 0.235 | 0.618 | 0.651 | 0.727 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different image generation models using automatic metrics. The models are evaluated based on their performance in generating manga images. A key distinction is made between models that use reference images as input (marked with *) and those that do not. The table also indicates which models were retrained using dialog embedding (marked with †). Metrics include FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), CLIP (CLIP image-text similarity), DINO-I (DINO image similarity), DINO-C (DINO character image similarity), and F1 score (dialog bounding box F1 score). Higher scores generally indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Quantitative comparisons on automatic metrics. Methods followed by “*” use reference images as input rather than characters. Methods marked by “†” means re-trained with dialog embedding.

| Method | FID ↓ | CLIP ↑ | DINO-I ↑ | DINO-C ↑ | F1 score ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR-LDM* [25] | 0.410 | 0.254 | 0.527 | 0.491 | 0.005 |

| StoryGen* [21] | 0.414 | 0.214 | 0.540 | 0.493 | 0.004 |

| SEED-Story* [45] | 0.413 | 0.167 | 0.442 | 0.428 | 0.005 |

| StoryDiffusion* [52] | 0.410 | 0.238 | 0.442 | 0.355 | 0.001 |

| MS-Diffusion† [38] | 0.410 | 0.227 | 0.584 | 0.600 | 0.601 |

| DiffSensei | 0.410 | 0.237 | 0.588 | 0.600 | 0.648 |

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different models’ performance on the MangaZero evaluation dataset. The comparison uses five key metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), CLIP image-text similarity (CLIP), DINO image similarity (DINO-I), DINO character image similarity (DINO-C), and dialog bounding box F1 score (F1 score). Each metric provides a quantitative measure of a model’s ability to generate manga pages that are visually appealing, semantically relevant, and faithful to the input text. The models included in this comparison are AR-LDM, StoryGen, SEED-Story, StoryDiffusion, MS-Diffusion, and the proposed model, DiffSensei. The models marked with ‘*’ use reference images as input rather than character images, and those marked with ‘†’ are re-trained with dialog embedding. The results offer insights into the strengths and weaknesses of each model regarding visual quality, text-image alignment, and character consistency.

read the caption

(a) Comparison on MangaZero evaluation set.

| CM | DM | Magi | MLLM | FID ↓ | CLIP ↑ | DINO-I ↑ | DINO-C ↑ | F1 score ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.410 | 0.230 | 0.593 | 0.610 | 0.361 | ||||

| ✓ | 0.411 | 0.225 | 0.591 | 0.637 | 0.364 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.407 | 0.228 | 0.600 | 0.635 | 0.653 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.408 | 0.231 | 0.618 | 0.648 | 0.718 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.407 | 0.235 | 0.618 | 0.651 | 0.727 |

🔼 Quantitative comparison results on Manga109 evaluation dataset using automatic metrics. The table shows the performance of different models (including DiffSensei and baselines) across multiple metrics: FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), CLIP (CLIP image-text similarity), DINO-I (DINO image similarity), DINO-C (DINO character image similarity), and F1 score (dialog bounding box F1 score). These metrics evaluate the quality of generated manga images and their alignment with the input text and character consistency. Manga109 contains unseen characters for the models during training, testing their generalization capabilities.

read the caption

(b) Comparison on Manga109 evaluation set.

| Rate | FID ↓ | CLIP ↑ | DINO-I ↑ | DINO-C ↑ | F1 score ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.408 | 0.233 | 0.615 | 0.646 | 0.718 |

| 0.5 | 0.407 | 0.235 | 0.618 | 0.651 | 0.727 |

| 1.0 | 0.407 | 0.233 | 0.610 | 0.644 | 0.729 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to evaluate the impact of different components in the DiffSensei model. The study systematically removes or replaces each component (character masked attention injection (CM), dialog masked encoding (DM), Magi image encoder, and MLLM for stage 2 training) and measures the performance on metrics such as FID, CLIP, DINO-I, DINO-C, and F1 score. This helps assess the contribution of each component to the overall model performance and understand their relative importance in customized manga generation.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study. CM is character masked attention injection. DM is dialog masked encoding. Magi means using Magi [30] image encoder. MLLM means using MLLM for stage 2 training.

| β | FID ↓ | CLIP ↑ | DINO-I ↑ | DINO-C ↑ | F1 score ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.408 | 0.231 | 0.618 | 0.648 | 0.718 |

| 0.2 | 0.407 | 0.231 | 0.620 | 0.653 | 0.722 |

| 0.4 | 0.407 | 0.235 | 0.618 | 0.651 | 0.727 |

| 0.6 | 0.406 | 0.237 | 0.608 | 0.637 | 0.728 |

| 0.8 | 0.407 | 0.237 | 0.604 | 0.629 | 0.727 |

| 1.0 | 0.407 | 0.236 | 0.601 | 0.618 | 0.731 |

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies performed on the DiffSensei model. It shows how the model’s performance changes when different components (character masked attention, dialog masked encoding, Magi image encoder, and the MLLM) are removed. The first row for each ablation shows the original performance of the model with all components included (in bold). The second row shows the model’s performance after removing one component (underlined). The metrics reported are FID, CLIP, DINO-I, DINO-C, and F1 score, which provide a quantitative assessment of the model’s performance on various aspects of manga generation.

read the caption

Table 4: Quantitative ablations. The first scores are bold. The second scores are underlined.

Full paper#