↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current text-to-image models struggle to precisely control fine-grained visual attributes like lighting, texture, and dynamics, limiting their practical applications. Existing methods often fall short in generalizability and lack fine-grained control. This paper tackles this by introducing the FiVA dataset, which features a large collection of high-quality images annotated with a comprehensive taxonomy of visual attributes.

The proposed FiVA-Adapter framework leverages the FiVA dataset to achieve better control. It disentangles visual attributes from source images and seamlessly integrates them into the generation process. This enables users to selectively apply desired characteristics, improving customization and enhancing image generation flexibility. The results demonstrate improved controllability, textual alignment, and flexibility compared to existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on controllable image generation. FiVA, a new dataset with fine-grained visual attributes and a corresponding adaptation framework, directly addresses the limitations of current text-to-image models in precisely controlling visual aspects. It opens exciting new avenues for research, potentially improving image quality and user experience in various applications. This work’s focus on decoupling and adapting visual attributes is timely and relevant to current research trends.

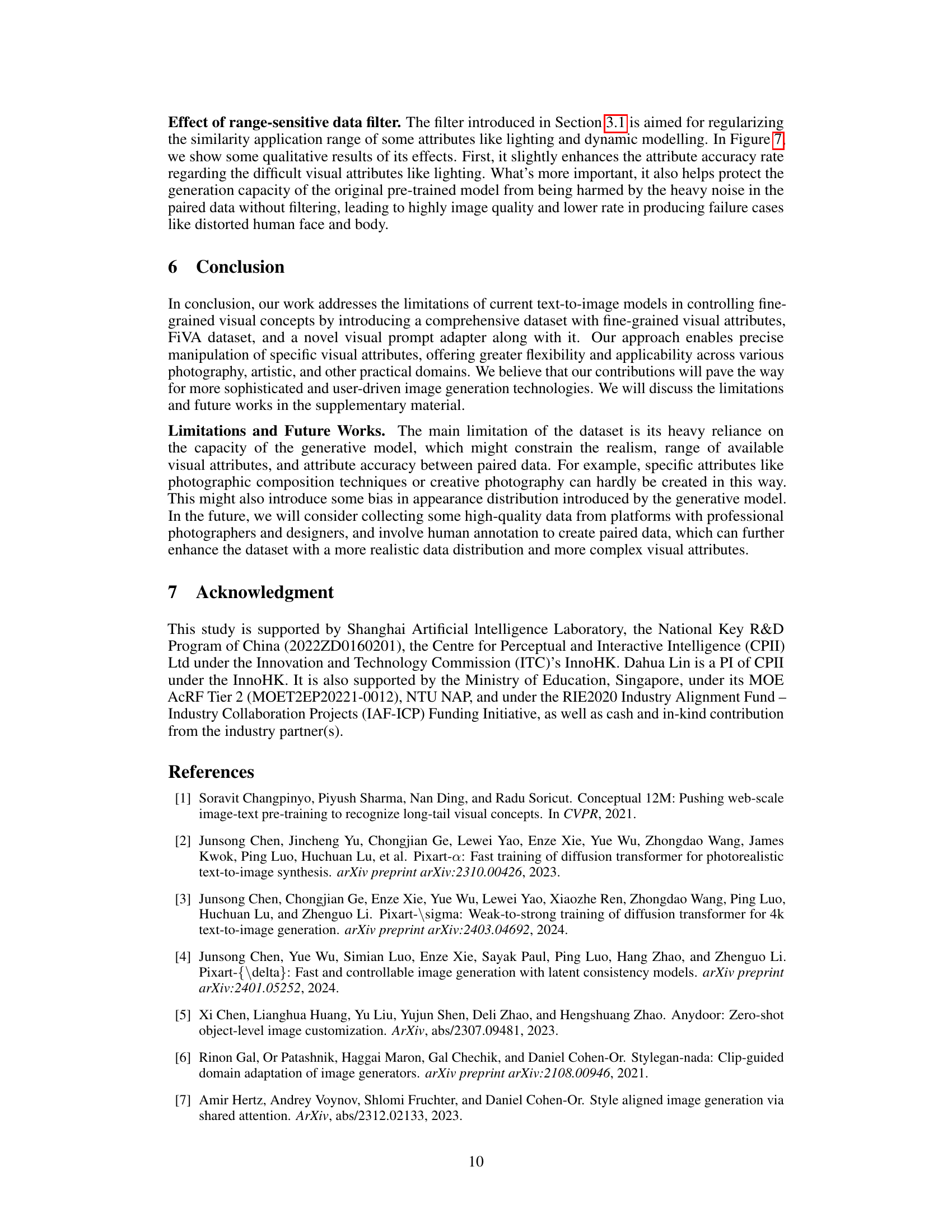

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 provides a high-level overview of the FiVA project. It showcases the dataset’s organization around a core set of fine-grained visual attributes (color, stroke, lighting, design, etc.), each illustrated with example images. The figure also highlights the FiVA-Adapter, a proposed framework built upon the FiVA dataset that facilitates user control over these attributes in image generation models. This control allows users to selectively combine specific attributes from multiple reference images to customize the output of text-to-image models. The ultimate aim is to improve the controllability and quality of images generated using text prompts.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview. We propose the FiVA dataset and adapter to learn fine-grained visual attributes for better controllable image generation.

| Attributes | Color | Stroke | Lighting | Dynamic | Focus_and_DoF | Design | Rhythm | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 429K | 301K | 370K | 89K | 107K | 66K | 52K | 202K |

| Accuracy | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.84 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.15 |

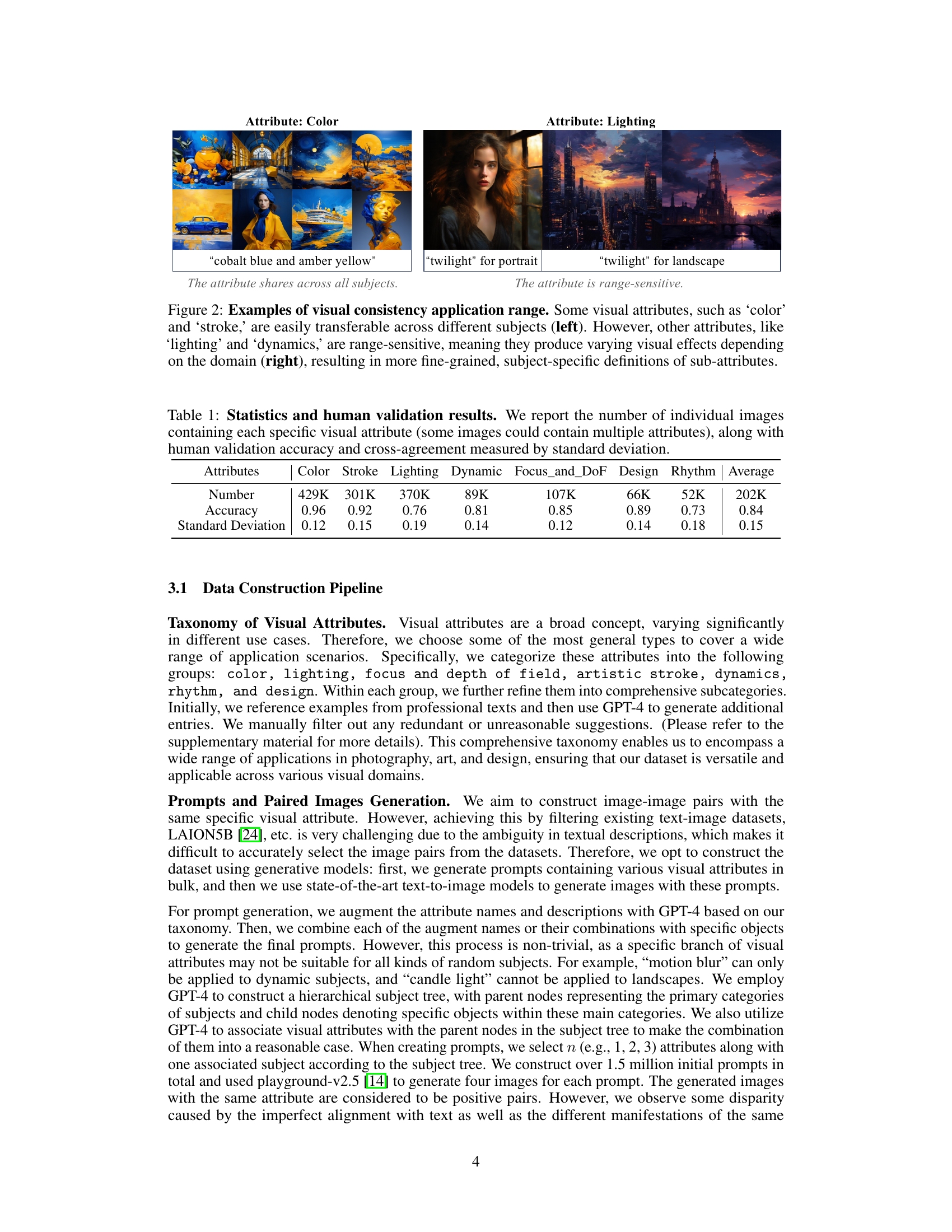

🔼 This table presents a statistical summary of the FiVA dataset, focusing on its visual attributes. It details the number of images annotated for each attribute (color, stroke, lighting, dynamics, focus and depth of field, design, and rhythm), highlighting that some images possess multiple attributes. Furthermore, it reports the accuracy of human validation for each attribute, indicating the level of agreement among annotators in assessing the presence of each visual attribute. Finally, it includes the standard deviation for each attribute, quantifying the level of inter-annotator agreement.

read the caption

Table 1: Statistics and human validation results. We report the number of individual images containing each specific visual attribute (some images could contain multiple attributes), along with human validation accuracy and cross-agreement measured by standard deviation.

In-depth insights#

FiVA Dataset#

The FiVA dataset represents a substantial contribution to the field of text-to-image generation. Its fine-grained visual attribute annotations allow for a level of control previously unattainable. The dataset’s size (around 1 million high-quality images) and organized taxonomy provide a robust foundation for training and evaluating models. The automated generation pipeline, leveraging advanced 2D generative models, is a novel approach, mitigating the limitations and costs associated with manually annotating real-world images. However, reliance on generative models introduces potential biases in the dataset’s distribution. Future work should focus on addressing these biases and expanding the range of visual attributes to enhance its diversity and ensure a truly representative capture of visual aesthetics. The choice to focus on synthetic data, while efficient, necessitates careful consideration of generalizability to real-world applications. The FiVA-Adapter framework proposed alongside the dataset demonstrates a practical application of the finely annotated data, showcasing the potential of this resource for generating highly customizable images.

Attribute Adaptation#

Attribute adaptation in the context of text-to-image generation is a crucial step towards achieving fine-grained control over the synthesized visuals. It involves disentangling various visual attributes present in reference images and selectively applying them to a new image generated based on a text prompt. This process moves beyond simple style transfer, which often conflates disparate elements like texture, color, and lighting into a single ‘style’ vector. A successful attribute adaptation system must effectively decompose these attributes, enabling precise manipulation of individual characteristics. This requires sophisticated models that can parse and represent attributes separately, then recombine them coherently to produce a unified visual output that aligns with user intent. Challenges lie in the creation of suitable datasets for training such models, requiring annotations that capture nuanced attributes across diverse image domains. Moreover, robust handling of ambiguous or conflicting attribute requests is essential for practical application. The overall goal is to provide users with intuitive and granular control over image generation, empowering them to create highly customized and realistic synthetic images.

Multimodal Encoding#

Multimodal encoding, in the context of text-to-image generation, is a crucial technique for effectively integrating information from different modalities such as text and images. A successful multimodal encoder must robustly capture the semantic relationships between the text description and the visual attributes of the images. This requires careful consideration of how to represent the diverse features within each modality and how to combine these representations to produce a unified embedding that benefits image generation. The core challenge lies in aligning the often abstract, linguistic features of text with the concrete, pixel-based details of images. Techniques like attention mechanisms and transformers are often employed to establish these correspondences. Different architectures may involve separate encoders for each modality followed by a fusion layer, or a shared encoder that processes both text and images concurrently. The choice of architecture significantly impacts the controllability and quality of the generated images, with superior methods producing images that closely match the text description while exhibiting specific visual attributes extracted from reference images. The effectiveness of the multimodal encoding heavily influences the overall performance of the text-to-image model, impacting factors such as visual fidelity, semantic consistency, and the model’s ability to handle complex instructions that involve multiple visual attributes from several sources. The focus should be on disentangling the different visual features and enabling selective incorporation of attributes from different sources for superior user control.

Dataset Limitations#

The primary limitation of the FiVA dataset stems from its reliance on the capabilities of current generative models. This dependence introduces a degree of artificiality, potentially limiting the realism and diversity of the visual attributes represented. The range of visual attributes might be constrained by the generative models’ limitations, resulting in a less comprehensive representation of aesthetic characteristics. The accuracy of attribute representation is also affected by potential biases introduced by these models, potentially leading to inconsistencies in the visual data. Furthermore, the reliance on automated data generation processes might inadvertently introduce subtle biases that are not easily detectable. Addressing these issues might involve supplementing the dataset with real-world images, integrating human annotation to enhance accuracy, and employing techniques to mitigate model bias, thereby strengthening the overall quality and scope of FiVA.

Future Directions#

Future research should focus on enhancing the dataset’s realism and diversity by incorporating real-world images and exploring a wider range of visual attributes beyond the current scope. Addressing the dataset’s reliance on generative models is crucial, as this reliance might introduce bias in appearance distribution. Investigating alternative data acquisition methods, such as human annotation or collaborative data gathering, would improve the dataset’s quality and remove generative model-induced limitations. Furthermore, future work could involve exploring more sophisticated techniques for disentangling visual attributes, perhaps using advanced representation learning methods or incorporating domain-specific knowledge. This would enable more nuanced and precise control over image generation, surpassing the current limitations of simple style transfer. Finally, the development of robust evaluation metrics is essential, moving beyond simplistic user studies and CLIP scores. Exploring more rigorous quantitative methods and addressing the inherent subjectivity involved in evaluating the aesthetics of generated images are needed. The development of new applications leveraging this enhanced control over fine-grained visual attributes is another important avenue for future research. This could include advancements in personalized image creation, sophisticated image editing tools, and novel artistic expression through AI.

More visual insights#

More on figures

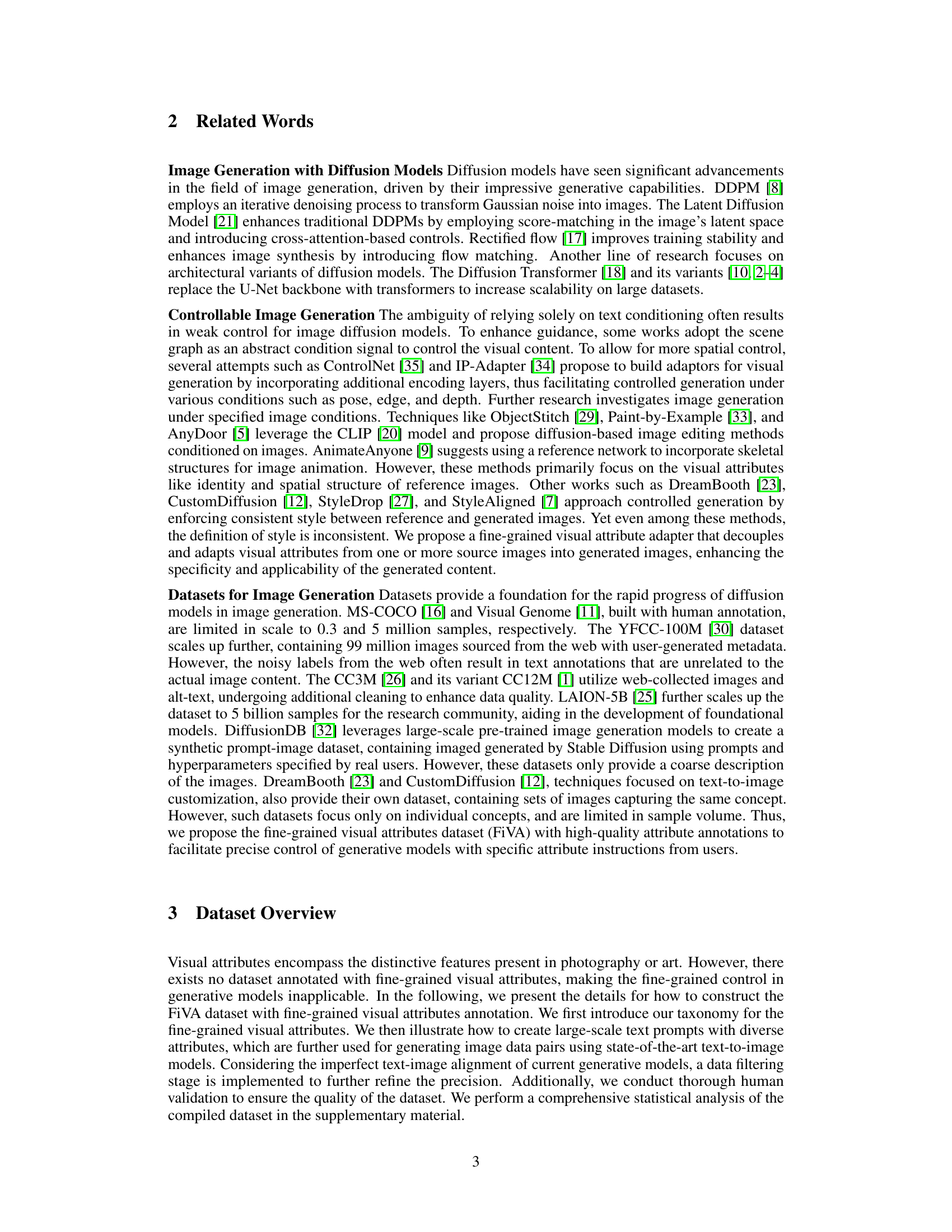

🔼 Figure 2 demonstrates how the application range of visual attributes varies. Attributes like color and stroke maintain consistency across different subjects. However, attributes such as lighting and dynamics are range-sensitive, producing different visual effects depending on the subject or scene. This necessitates more granular, subject-specific definitions for these range-sensitive attributes.

read the caption

Figure 2: Examples of visual consistency application range. Some visual attributes, such as ‘color’ and ‘stroke,’ are easily transferable across different subjects (left). However, other attributes, like ‘lighting’ and ‘dynamics,’ are range-sensitive, meaning they produce varying visual effects depending on the domain (right), resulting in more fine-grained, subject-specific definitions of sub-attributes.

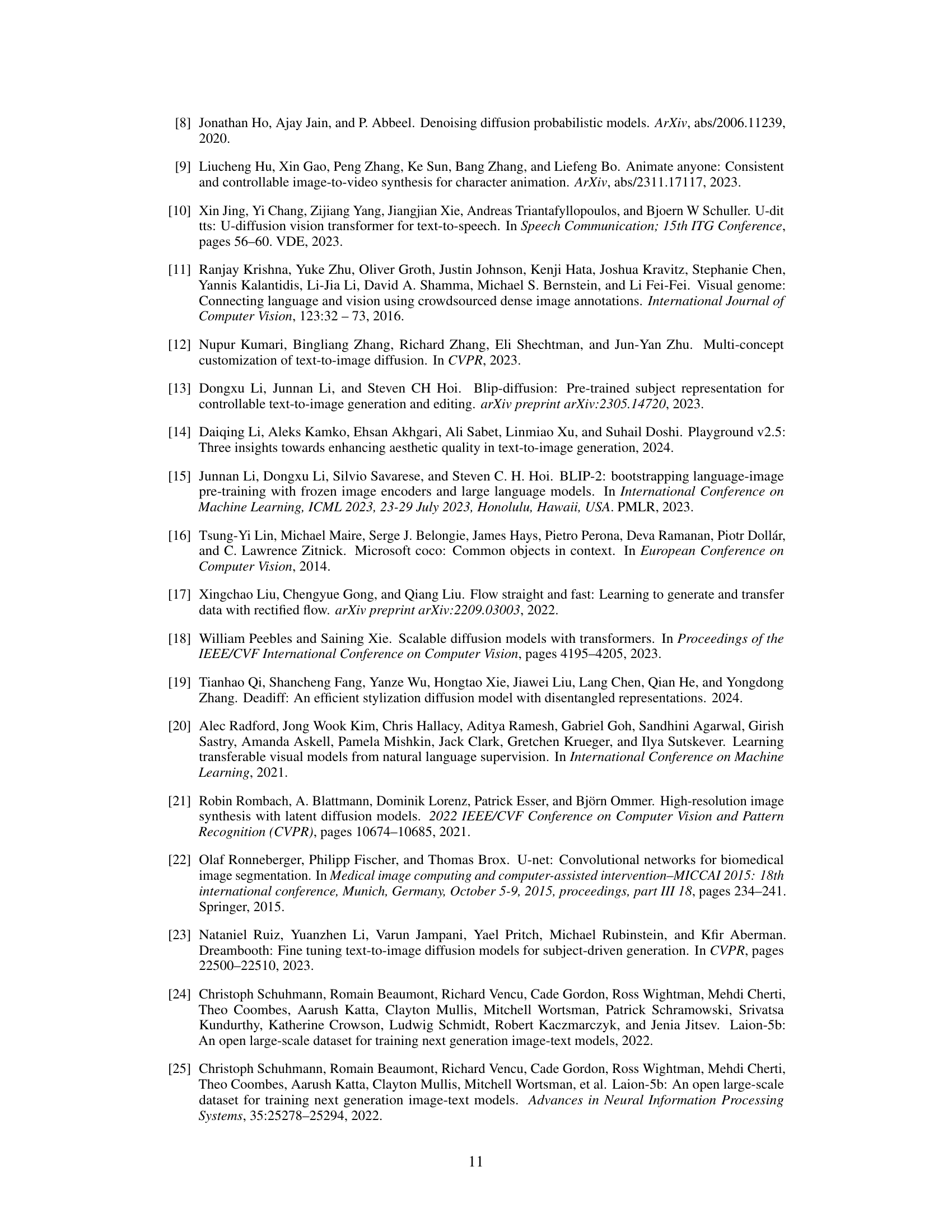

🔼 The figure illustrates the architecture and training pipeline of the FiVA-Adapter, a novel framework designed for fine-grained visual attribute adaptation in text-to-image diffusion models. FiVA-Adapter consists of two main components: 1) an Attribute-specific Visual Prompt Extractor, which extracts relevant visual feature embeddings from input images based on specified attributes; and 2) a Multi-image Dual Cross-Attention Module, which integrates these attribute-specific features along with text prompts into the diffusion model to generate images with precisely controlled attributes. The pipeline shows how image features are extracted, fused with text embeddings, and processed through cross-attention modules before feeding into the U-Net for image generation.

read the caption

Figure 3: FiVA-Adapter architecture and training pipeline. FiVA-Adapter has two key designs: 1) Attribute-specific Visual Prompt Extractor, 2) Multi-image Dual Cross-Attention Module.

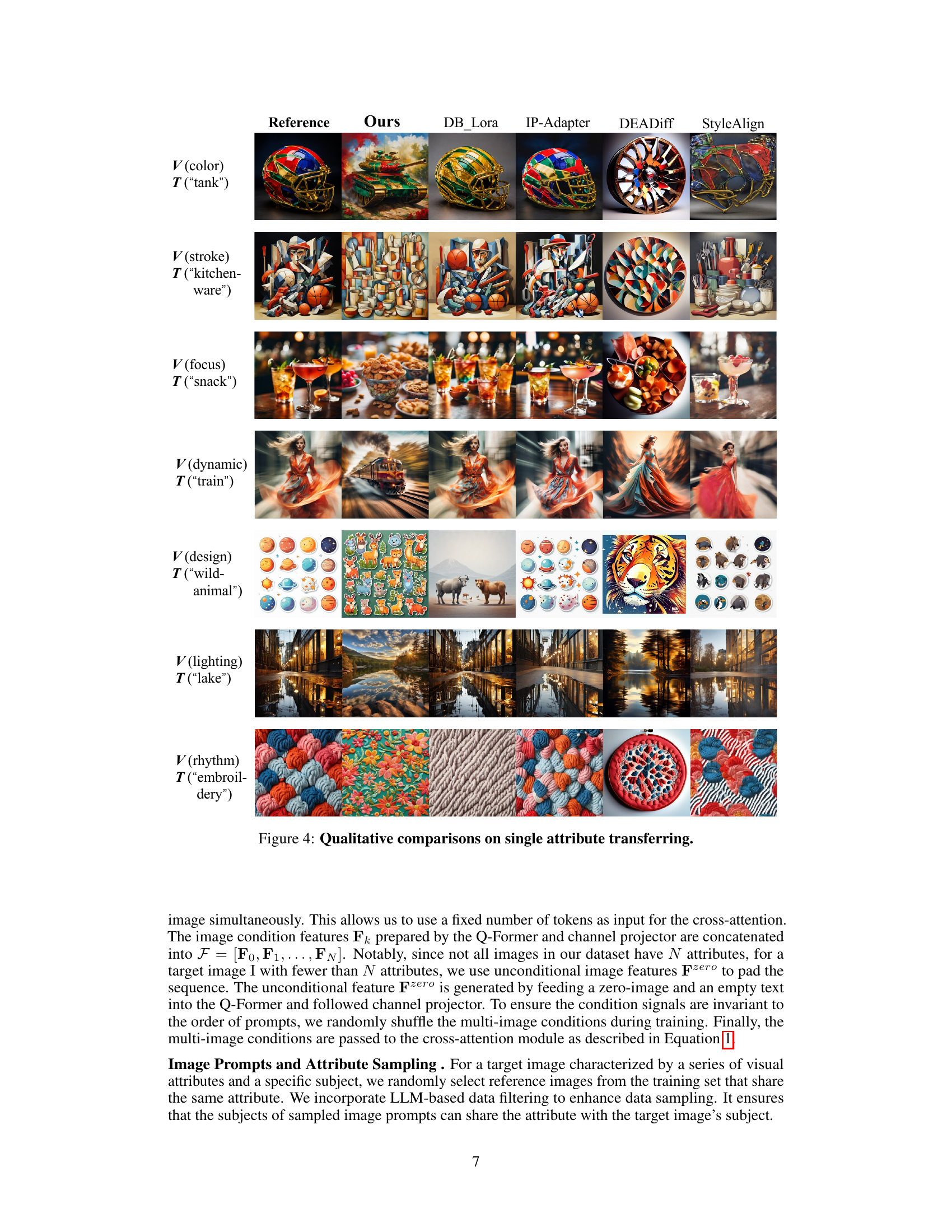

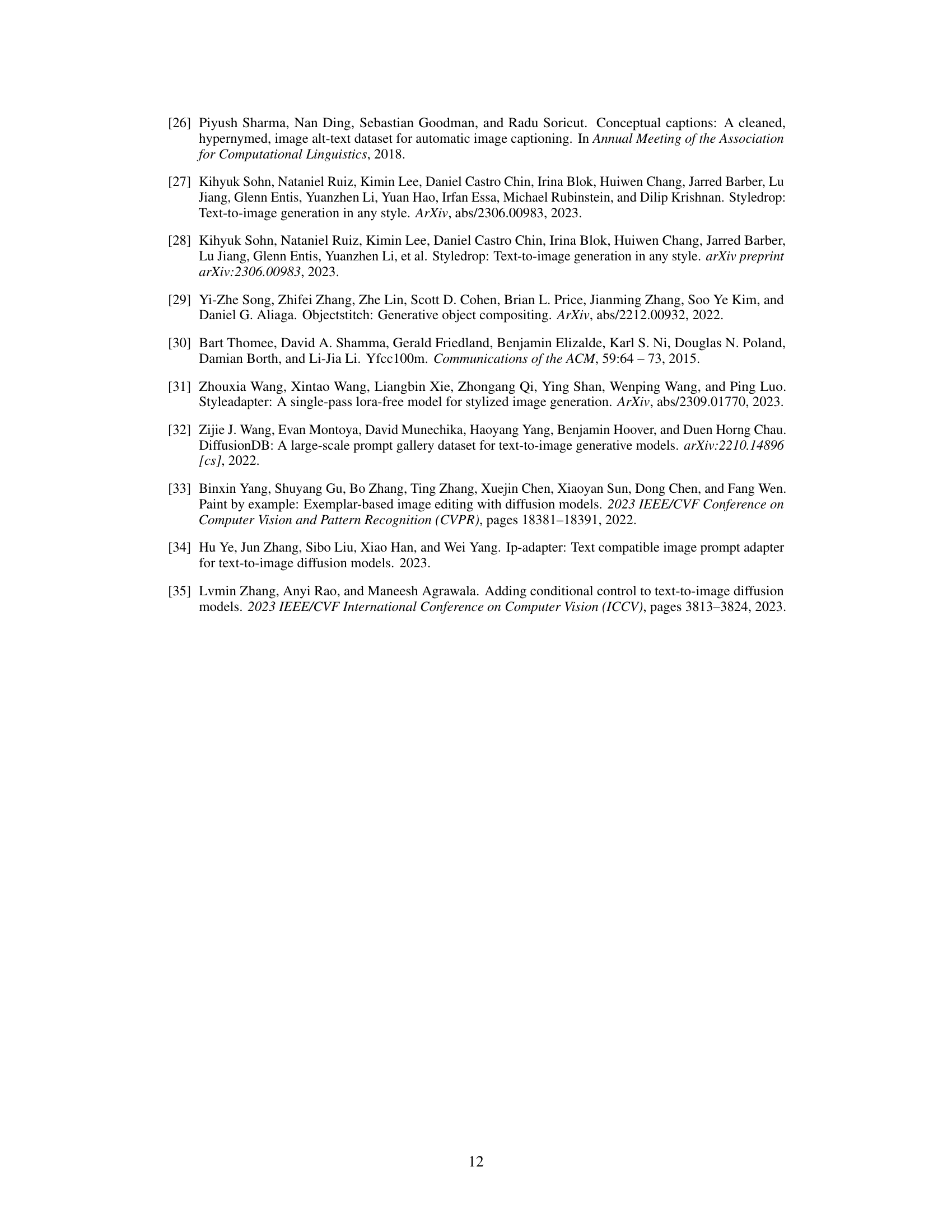

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of different methods for transferring a single visual attribute from a reference image to a generated image. It shows the results of several methods including the proposed FiVA-Adapter alongside baselines such as DreamBooth Lora, IP-Adapter, DEADiff, and StyleAlign. For each method, a series of images demonstrates the transfer of attributes like color, stroke, focus, dynamics, design, lighting, and rhythm. The comparison highlights the effectiveness of FiVA-Adapter in accurately transferring the desired attributes while maintaining the overall integrity and consistency of the target image.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative comparisons on single attribute transferring.

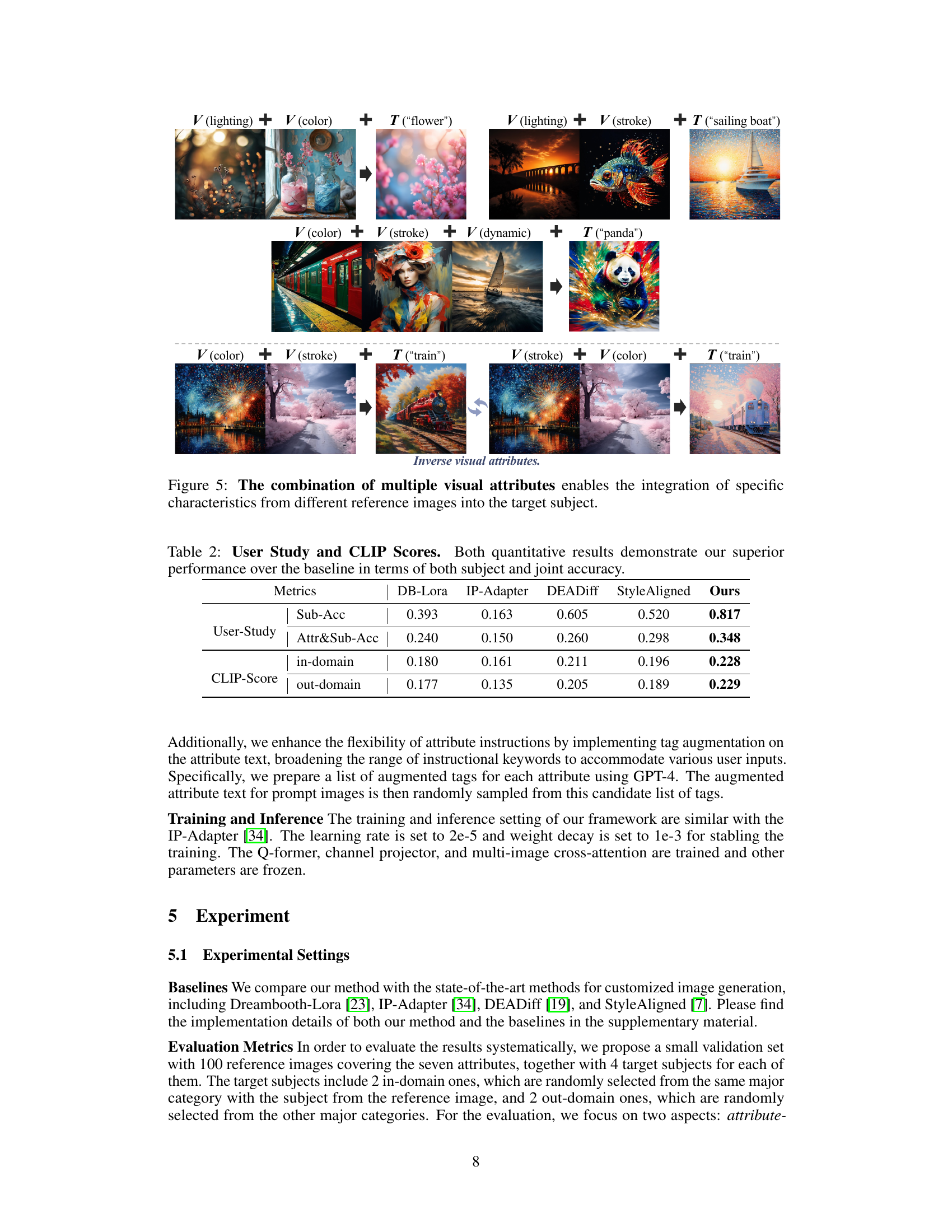

🔼 Figure 5 showcases the capability of the FiVA-Adapter to combine visual attributes from multiple source images. The figure demonstrates that by using the framework, specific visual characteristics (like color, stroke, lighting, or dynamics) extracted from different reference images can be successfully integrated into a single generated image, creating a customized result that reflects the combined attributes of the sources while adhering to a target subject or theme. This highlights the flexibility and power of the approach in controlling fine-grained aspects of image generation.

read the caption

Figure 5: The combination of multiple visual attributes enables the integration of specific characteristics from different reference images into the target subject.

🔼 Figure 6 demonstrates that by using different tags in the prompt, various visual attributes can be extracted from a single reference image. This showcases the fine-grained control offered by the FiVA-Adapter in isolating and manipulating specific visual aspects for subsequent image generation.

read the caption

Figure 6: Attribute decomposition. One reference image can be decomposed into different attributes via different tags.

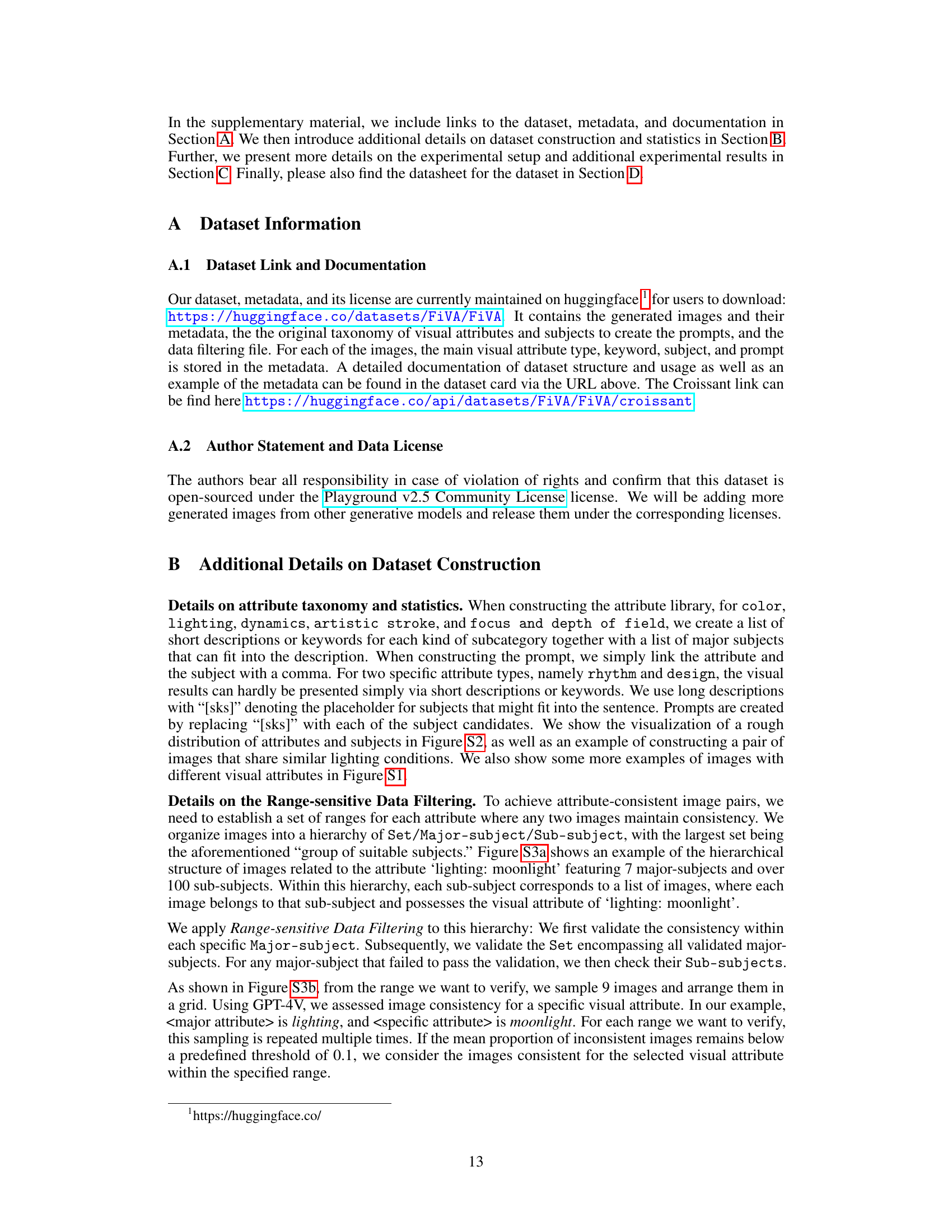

🔼 This ablation study demonstrates the effect of a range-sensitive data filter on the quality of image generation. The filter is designed to improve the accuracy of attribute transfer while maintaining the original generation capacity. Removing the filter leads to reduced attribute accuracy and increased generation failures, highlighting the importance of the filter in ensuring high-quality and consistent results.

read the caption

Figure 7: Ablation on range-sensitive data filter. It helps improve the attribute accuracy and protect the original generation capacity.

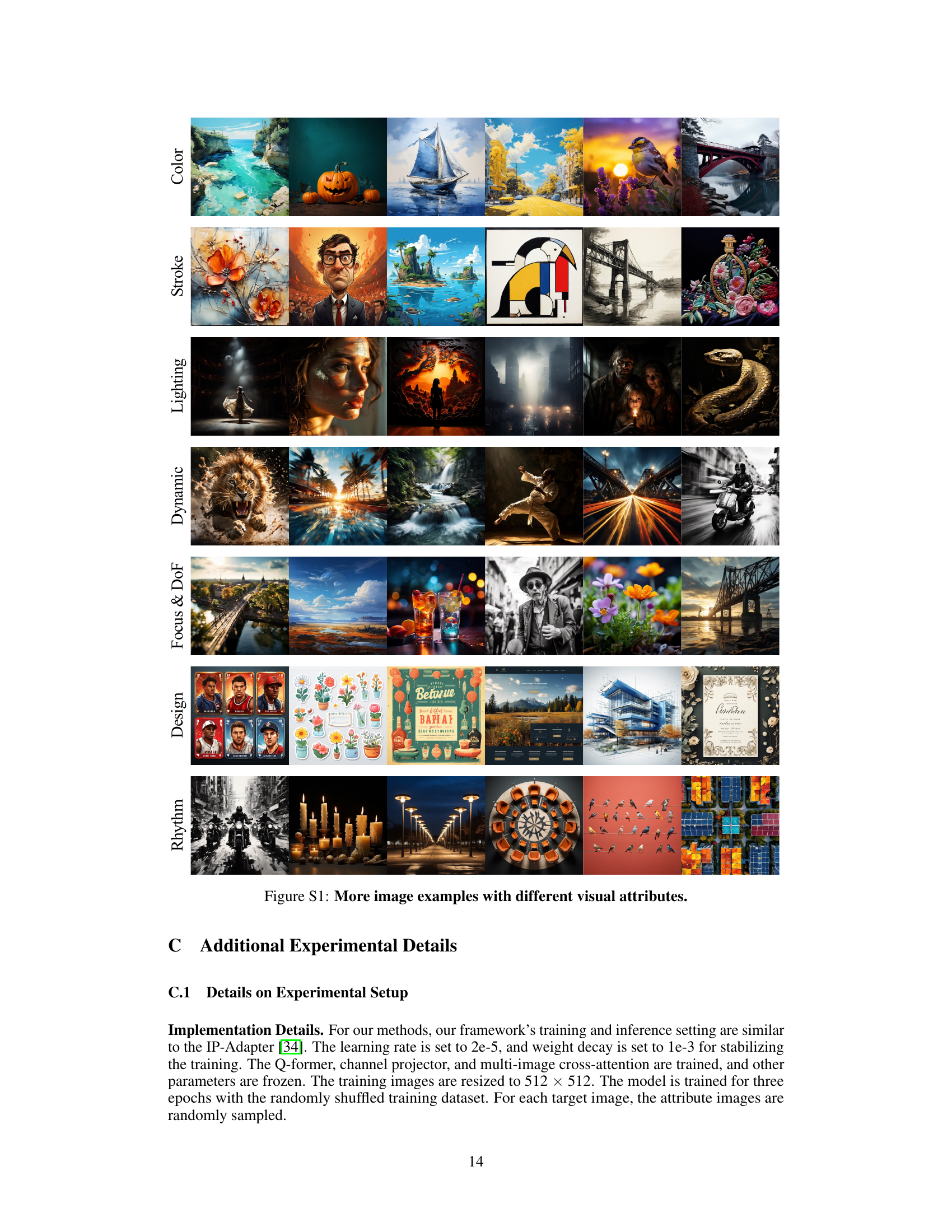

🔼 This figure displays a collection of images showcasing the diverse range of visual attributes captured in the FiVA dataset. Each row highlights a specific attribute (e.g., color, stroke, lighting, dynamics, focus & depth of field, design, rhythm), displaying multiple example images representing variations within that attribute. This visually demonstrates the breadth and granularity of visual characteristics included within the dataset used to train the FiVA-Adapter model.

read the caption

Figure S1: More image examples with different visual attributes.

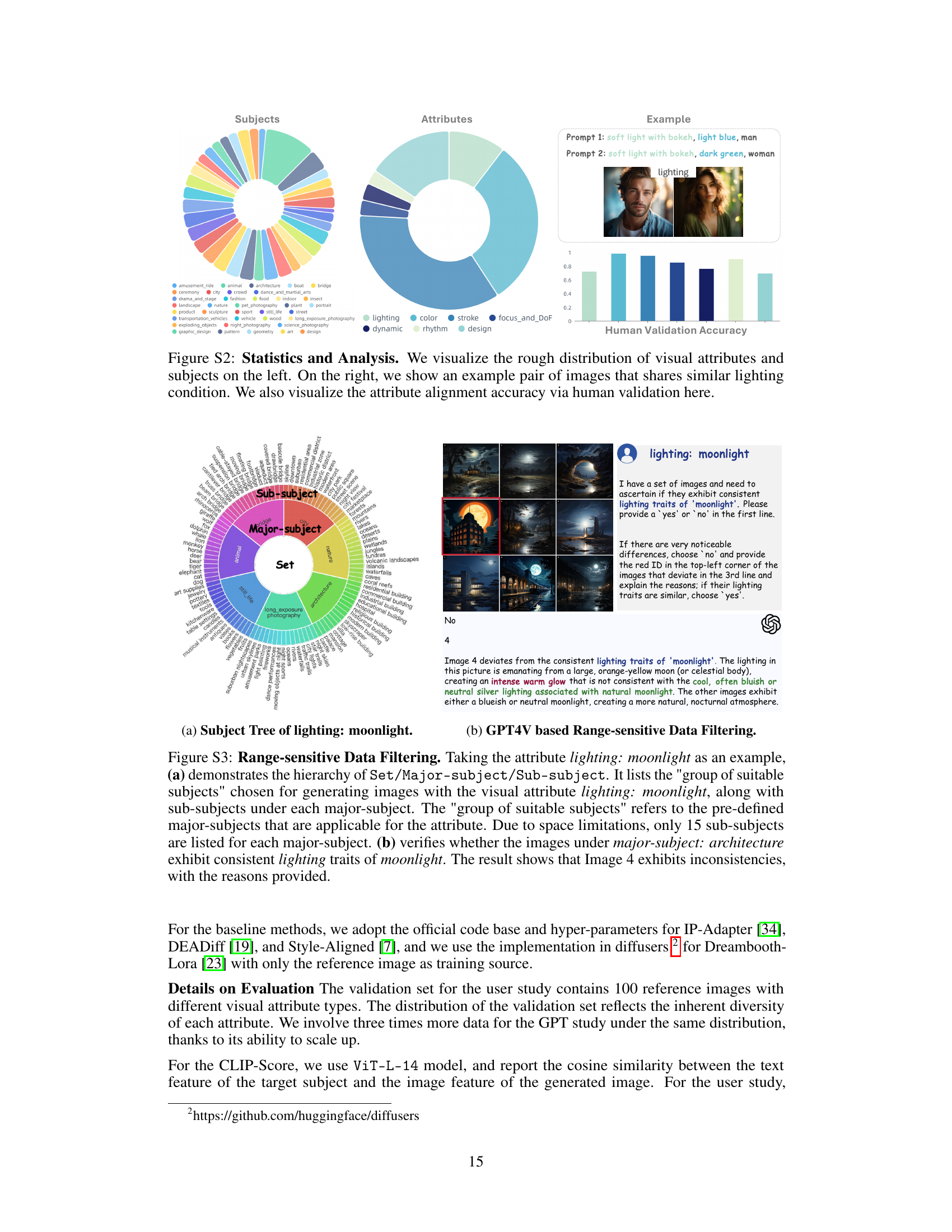

🔼 Figure S2 presents a comprehensive analysis of the FiVA dataset. The left side displays the overall distribution of visual attributes (e.g., color, lighting, stroke) and subjects (e.g., animals, architecture, cityscapes) using pie charts. This visualization provides a clear overview of the dataset’s composition, highlighting the prevalence of different visual aspects and subject categories. The right side showcases an example of an image pair from the dataset exhibiting similar lighting conditions. This example visually demonstrates the core concept of the dataset, where images possess shared visual attributes. Finally, the figure incorporates a chart illustrating the attribute alignment accuracy obtained through human validation. This quantitative measure underscores the quality and reliability of the attribute annotations in the dataset.

read the caption

Figure S2: Statistics and Analysis. We visualize the rough distribution of visual attributes and subjects on the left. On the right, we show an example pair of images that shares similar lighting condition. We also visualize the attribute alignment accuracy via human validation here.

🔼 This figure shows a hierarchical tree structure representing the organization of images based on the visual attribute ’lighting: moonlight’. The tree starts with a root node representing the entire set of images. This is broken down into major subject categories (e.g., City, Nature, Architecture), each further divided into sub-categories (e.g., City -> urban skylines, suburban nightscapes, etc.). This hierarchical structure is used in a range-sensitive data filtering process to ensure consistency in visual attributes across different image subjects.

read the caption

(a) Subject Tree of lighting: moonlight.

🔼 This figure shows the process of range-sensitive data filtering using GPT-4V. The process starts with a hierarchical subject tree that organizes images based on their visual attributes. For each attribute, GPT-4V is used to assess the consistency of visual effects across different subjects. If the consistency is high, then the images are considered to have similar visual effects. If not, the process is repeated at a lower level in the hierarchy. This ensures that only attribute-consistent image pairs are retained in the dataset.

read the caption

(b) GPT4V based Range-sensitive Data Filtering.

🔼 Figure S3 illustrates the process of range-sensitive data filtering used to create a high-quality dataset for fine-grained visual attribute control. Part (a) shows the hierarchical structure used to organize subjects and sub-subjects based on their suitability for specific visual attributes (in this case, ’lighting: moonlight’). The top level (‘Set’) represents all suitable subjects, which are broken down into major subjects, and finally sub-subjects to ensure fine-grained control. Due to space constraints, only 15 sub-subjects are shown for each major subject. Part (b) demonstrates a specific example of the validation process performed to check the consistency of the ‘moonlight’ attribute within the ‘architecture’ major subject. Nine example images are presented, and it is explained that image 4 shows inconsistent lighting characteristics compared to the others. This inconsistency is highlighted along with the explanation.

read the caption

Figure S3: Range-sensitive Data Filtering. Taking the attribute lighting: moonlight as an example, (a) demonstrates the hierarchy of Set/Major-subject/Sub-subject. It lists the 'group of suitable subjects' chosen for generating images with the visual attribute lighting: moonlight, along with sub-subjects under each major-subject. The 'group of suitable subjects' refers to the pre-defined major-subjects that are applicable for the attribute. Due to space limitations, only 15 sub-subjects are listed for each major-subject. (b) verifies whether the images under major-subject: architecture exhibit consistent lighting traits of moonlight. The result shows that Image 4 exhibits inconsistencies, with the reasons provided.

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of attribute input augmentation on model robustness. Two sets of models were trained: one with tag augmentation and one without. The models were then tested on inputs with slight deviations from the standard attribute names used during training. The results show that models trained with tag augmentation were more resilient to these variations and produced successful outputs, while those without augmentation failed to generate correct results.

read the caption

Figure S4: Ablation on attribute input augmentation. Models trained with tag augmentation handle slight deviations in input text during inference, while those without augmentation would fail in these cases.

🔼 Figure S5 presents a qualitative evaluation of the FiVA-Adapter’s performance on real-world images. The figure showcases example images generated by the FiVA-Adapter using real-world images as input, demonstrating its ability to generalize beyond the synthetic dataset used for training. The results highlight the adaptability and versatility of the method for fine-grained attribute adaptation in diverse image domains.

read the caption

Figure S5: Examples with real-world images. We demonstrate that our adapter can be effectively extended to real-world images, which have a different distribution from generated images.

More on tables

| Metrics | DB-Lora | IP-Adapter | DEADiff | StyleAligned | Ours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User-Study | |||||

| Sub-Acc | 0.393 | 0.163 | 0.605 | 0.520 | 0.817 |

| Attr&Sub-Acc | 0.240 | 0.150 | 0.260 | 0.298 | 0.348 |

| CLIP-Score | |||||

| in-domain | 0.180 | 0.161 | 0.211 | 0.196 | 0.228 |

| out-domain | 0.177 | 0.135 | 0.205 | 0.189 | 0.229 |

🔼 This table presents the results of a user study and CLIP score evaluations comparing the proposed FiVA-Adapter method to several baselines for controllable image generation. The metrics used are Subject Accuracy (measuring how accurately the generated image matches the intended subject) and Attribute & Subject Accuracy (measuring the joint accuracy of both subject and attribute). Both in-domain (subjects from the same category as the reference image) and out-of-domain (subjects from different categories) evaluations are included to assess the model’s generalization capabilities. The results demonstrate that FiVA-Adapter outperforms the baselines in terms of both subject and joint accuracy, indicating its superior performance in controllable image generation.

read the caption

Table 2: User Study and CLIP Scores. Both quantitative results demonstrate our superior performance over the baseline in terms of both subject and joint accuracy.

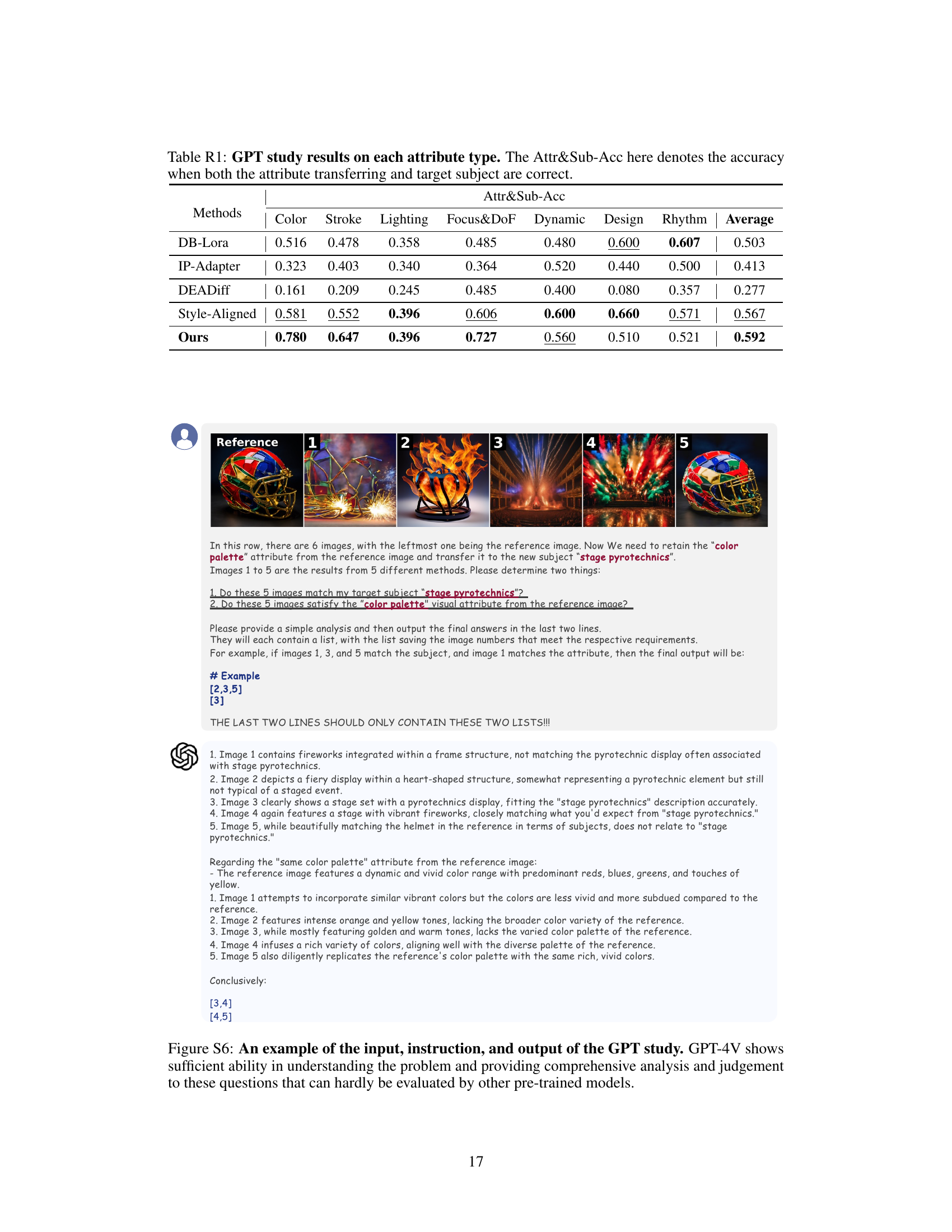

| Methods | Color | Stroke | Lighting | Focus&DoF | Dynamic | Design | Rhythm | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB-Lora | 0.516 | 0.478 | 0.358 | 0.485 | 0.480 | 0.600 | 0.607 | 0.503 |

| IP-Adapter | 0.323 | 0.403 | 0.340 | 0.364 | 0.520 | 0.440 | 0.500 | 0.413 |

| DEADiff | 0.161 | 0.209 | 0.245 | 0.485 | 0.400 | 0.080 | 0.357 | 0.277 |

| Style-Aligned | 0.581 | 0.552 | 0.396 | 0.606 | 0.600 | 0.660 | 0.571 | 0.567 |

| Ours | 0.780 | 0.647 | 0.396 | 0.727 | 0.560 | 0.510 | 0.521 | 0.592 |

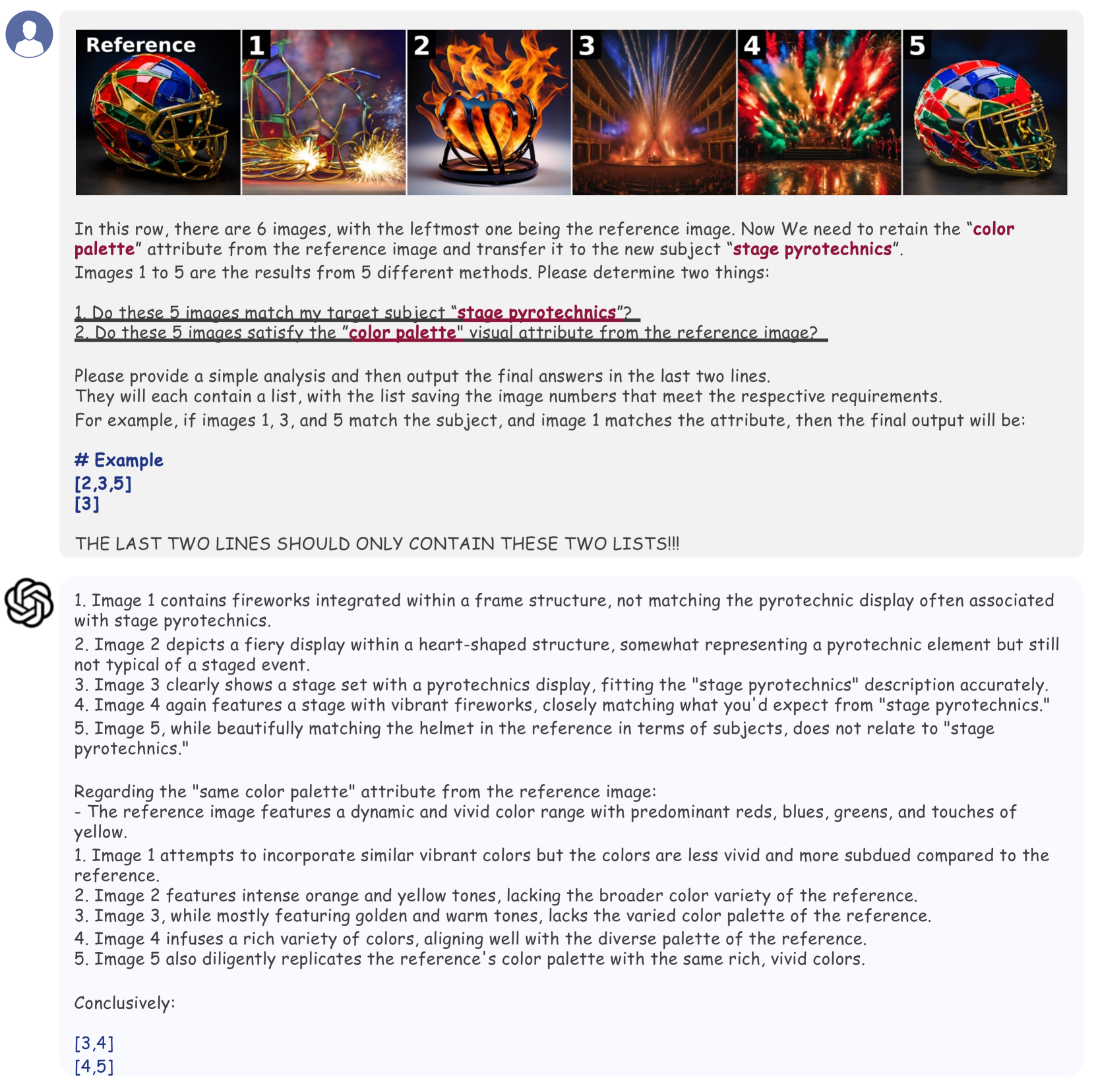

🔼 This table presents the results of a qualitative user study using GPT-4V, a large language model, to evaluate the performance of different image generation methods on various visual attributes. Specifically, it assesses the accuracy of each method in transferring a single visual attribute (color, stroke, lighting, focus and depth of field, dynamic, design, rhythm) from a reference image to a target image, while also ensuring that the generated image’s subject accurately matches the target. The ‘Attr&Sub-Acc’ metric combines both attribute transfer accuracy and subject accuracy, indicating whether both aspects were correctly generated.

read the caption

Table R1: GPT study results on each attribute type. The Attr&Sub-Acc here denotes the accuracy when both the attribute transferring and target subject are correct.

Full paper#