↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD) struggles with real-world applications due to its assumptions of pre-identified spans and provided sense candidates. This paper introduces Word Sense Linking (WSL), a new task that addresses these limitations. WSL combines span identification and sense linking directly from text, making it more practical and applicable.

The proposed approach uses a transformer-based retriever-reader architecture. The retriever generates candidate senses, while the reader identifies spans and links them to their most suitable meaning. Experiments show the superiority of this approach over adapting state-of-the-art WSD systems to WSL, highlighting significant performance gains, especially in recall, while addressing the challenges of real-world, unconstrained settings. The work also introduces a novel WSL dataset, enriching the existing WSD benchmark and furthering future research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limitations of existing Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD) systems. By introducing Word Sense Linking (WSL) and a novel architecture, it offers a more practical and realistic approach to WSD, bridging the gap between academic research and real-world applications. This work opens new avenues for improving the integration of lexical semantics into downstream tasks, impacting various NLP areas. Its comprehensive evaluation and dataset release also benefit the broader NLP community.

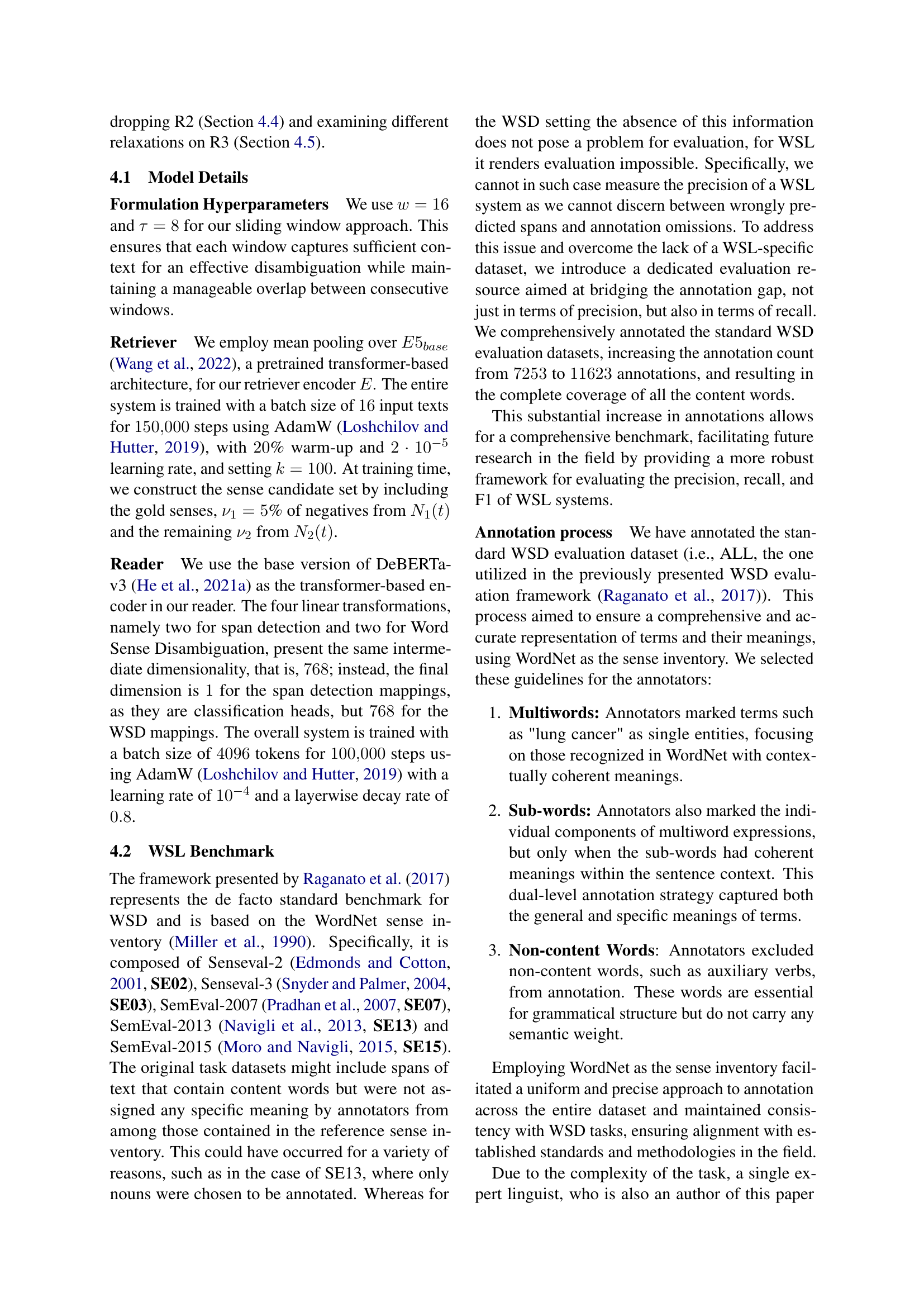

Visual Insights#

🔼 The figure illustrates the Word Sense Linking (WSL) process, which consists of three main stages. First, a retriever component identifies the top-k candidate senses for the input text, effectively performing Candidate Generation. Second, a reader component identifies the spans within the input text that need disambiguation, executing Concept Detection. Finally, the reader links each of these identified spans to its most suitable sense from the candidate senses, completing the Word Sense Disambiguation step. The overall process demonstrates how the WSL model determines both what parts of text to disambiguate and which meanings to assign to them.

read the caption

Figure 1: Our WSL process. First, the retriever identifies the top-k𝑘kitalic_k candidate senses (Candidate Generation). Then, the reader identifies the spans to be disambiguated (Concept Detection) and pairs each of these with their most suitable sense (Word Sense Disambiguation).

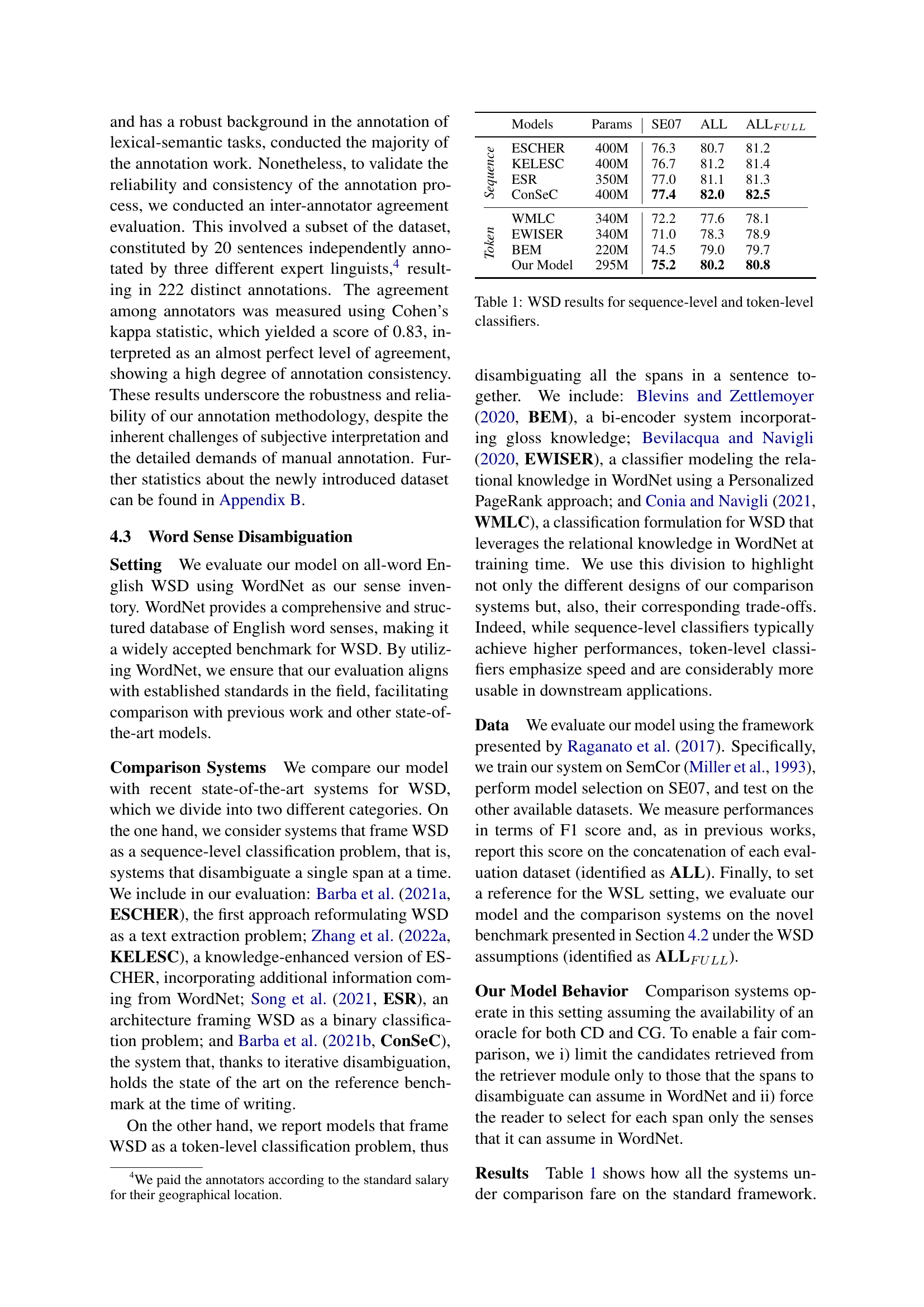

| Models | Params | SE07 | ALL | ALLFULL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sequence | ESCHER | 400M | 76.3 | 80.7 | 81.2 |

| KELESC | 400M | 76.7 | 81.2 | 81.4 | |

| ESR | 350M | 77.0 | 81.1 | 81.3 | |

| ConSeC | 400M | 77.4 | 82.0 | 82.5 | |

Token | WMLC | 340M | 72.2 | 77.6 | 78.1 |

| EWISER | 340M | 71.0 | 78.3 | 78.9 | |

| BEM | 220M | 74.5 | 79.0 | 79.7 | |

| Our Model | 295M | 75.2 | 80.2 | 80.8 |

🔼 This table presents the performance of various Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD) models, categorized into sequence-level and token-level classifiers, on the benchmark dataset ALL. It shows the F1 scores achieved by each model on the SE07 and ALL datasets, providing a comparison of different WSD approaches and their effectiveness in disambiguating word senses. The table also includes model parameters to allow for an analysis of the model’s complexity and performance trade-offs. The results highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various WSD systems and their suitability for sequence vs. token-based disambiguation.

read the caption

Table 1: WSD results for sequence-level and token-level classifiers.

In-depth insights#

WSD’s Sandbox#

The concept of “WSD’s Sandbox” encapsulates the limitations of traditional Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD) methods. These methods typically operate under restrictive assumptions, such as pre-identified spans of text needing disambiguation and a predefined set of possible word senses. This creates a controlled environment, akin to a sandbox, where WSD systems are evaluated on their ability to select the correct sense given these constraints. However, real-world text is rarely so neatly packaged, lacking explicit sense candidates and span boundaries. This “sandboxed” approach hinders the practical applicability of WSD to numerous downstream tasks. Moving beyond the sandbox necessitates techniques that can robustly handle the ambiguity inherent in natural language, requiring advancements in both concept detection and candidate sense generation, thus enabling a more flexible and effective approach to WSD that can adapt to unconstrained real-world data.

WSL: A New Task#

The proposed Word Sense Linking (WSL) task represents a significant advancement in lexical semantics, addressing the limitations of traditional Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD). WSL moves beyond the restrictive assumptions of WSD, which require pre-identified spans and provided sense candidates. Instead, WSL challenges systems to identify relevant spans within an input text and link them to the most suitable senses from a given inventory. This shift towards a more realistic scenario is crucial, as it better reflects the needs of downstream applications that often don’t have the luxury of pre-processed data. The introduction of WSL is a paradigm shift, fostering the integration of lexical semantics into broader NLP tasks. The evaluation dataset further strengthens this contribution, enabling rigorous assessment of system performance under the more challenging conditions of WSL. The task’s inherent flexibility and focus on real-world applicability promise to stimulate new research and innovative approaches to lexical disambiguation, bridging the gap between theoretical advances and practical implementations.

Retriever-Reader#

The Retriever-Reader architecture represents a powerful paradigm shift in information retrieval, particularly within the context of natural language processing tasks like Word Sense Linking (WSL). The retriever module efficiently pre-filters the vast search space by identifying and ranking relevant candidate senses from a given sense inventory. This drastically reduces the computational burden on the subsequent reader module, which then focuses on disambiguating specific spans of text based on the pre-selected candidates. This two-stage approach is particularly advantageous in scenarios with large sense inventories and long input texts. The synergistic combination of these two components offers enhanced efficiency and accuracy compared to traditional methods that attempt to process all information simultaneously. The retriever stage intelligently reduces the complexity of the task, resulting in more focused and effective processing by the reader. This approach allows the model to tackle the challenges of WSL, including concept detection and candidate generation, which would otherwise be computationally prohibitive.

WSL Evaluation#

A robust WSL (Word Sense Linking) evaluation requires a multifaceted approach. Benchmark datasets need to be carefully curated, addressing potential biases in existing WSD (Word Sense Disambiguation) corpora through comprehensive annotation of previously neglected spans. This is crucial to ensure a fair and accurate assessment of WSL systems’ performance. Evaluation metrics should not only capture the accuracy of sense linking but also the effectiveness of span identification (concept detection). The use of precision, recall, and F1-score, possibly combined with metrics specific to span detection, is essential. Furthermore, experimental setup should consider variations in data conditions, such as the availability of sense inventories and word-to-sense mappings, and the impact of these variations on system performance. Analyzing such factors provides insights into the robustness and generalizability of different WSL approaches, thereby revealing their suitability for real-world applications where data is often incomplete or noisy. Finally, comparative analysis with existing WSD systems, adapted to the WSL setting, will showcase the advantages and challenges of WSL and highlight its potential to advance lexical semantic processing in unconstrained environments.

Future of WSL#

The future of Word Sense Linking (WSL) is bright, driven by the need for more robust and adaptable natural language processing. Improved sense inventories and methods to better handle lexical variations and named entities are crucial. Supervised approaches to concept detection, moving beyond simple heuristics, will be necessary to improve span identification. Research should focus on better addressing challenges in low-resource settings, including those with incomplete word-to-sense mappings, and develop more sophisticated methods for handling the nuances of language. Cross-lingual WSL, expanding beyond English, is a critical area for future work. Ultimately, the success of WSL hinges on creating robust and accurate methods for disambiguating word senses in diverse and complex real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

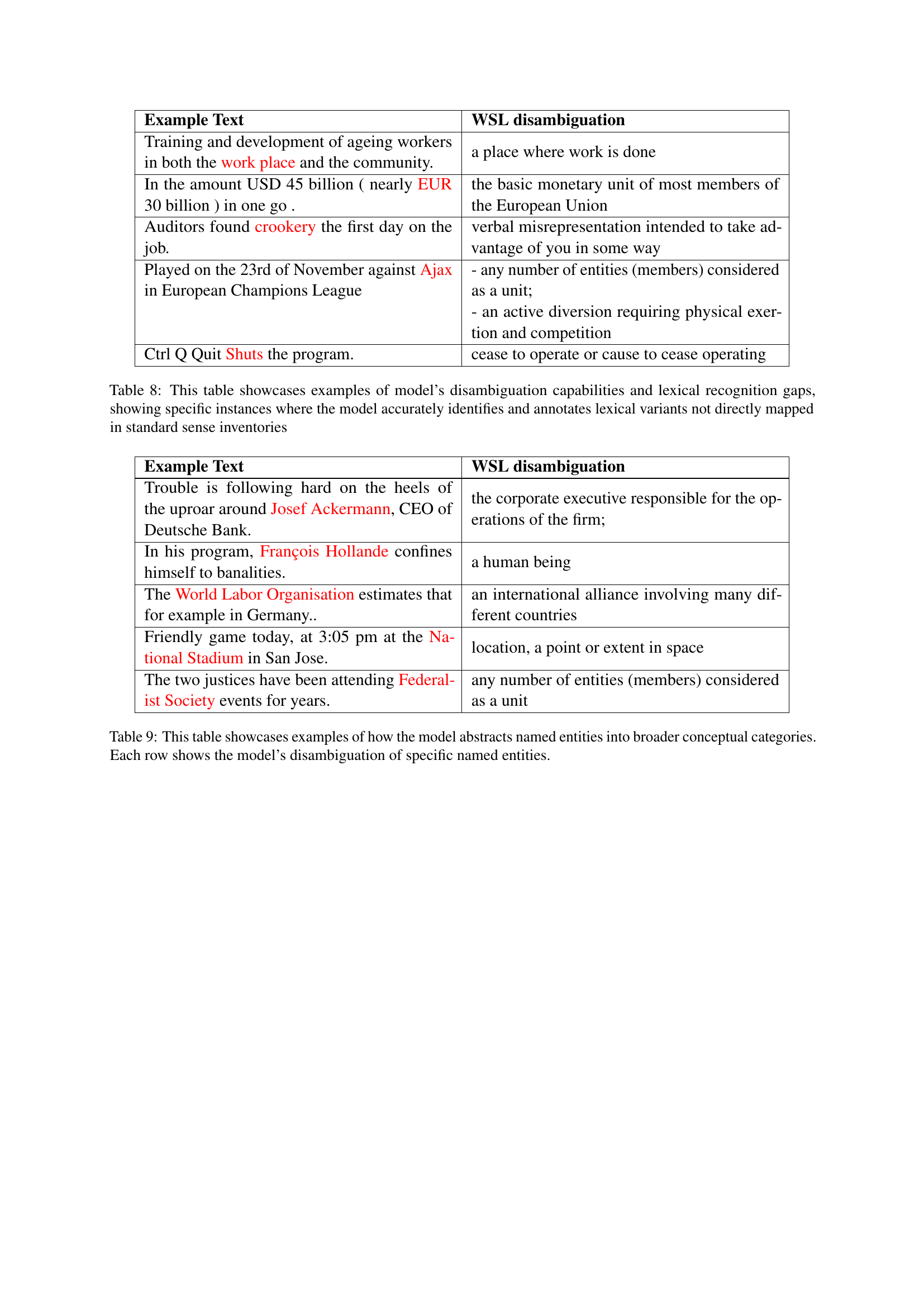

🔼 This figure shows the number of annotations for four different parts-of-speech (POS) tags (Noun, Verb, Adjective, and Adverb) across three datasets (Senseval2, Senseval3, and Semeval2015). The bars are divided into ‘OLD’ (blue) representing the original number of annotations in each dataset, and ‘NEW’ (orange) showing the number of annotations added by the authors through their comprehensive annotation process. This visualization helps to illustrate the extent of the data augmentation undertaken in the study to improve the balance and completeness of the datasets.

read the caption

Figure 2: The counts of four POS categories (NOUN, VERB, ADJ, ADV) for three different datasets (Senseval2, Senseval3, Semeval2015). Each POS category is subdivided into ’OLD’ (blue) and ’NEW’ (orange) data points, indicating the frequency of each annotation before and after our comprehensive annotation process.

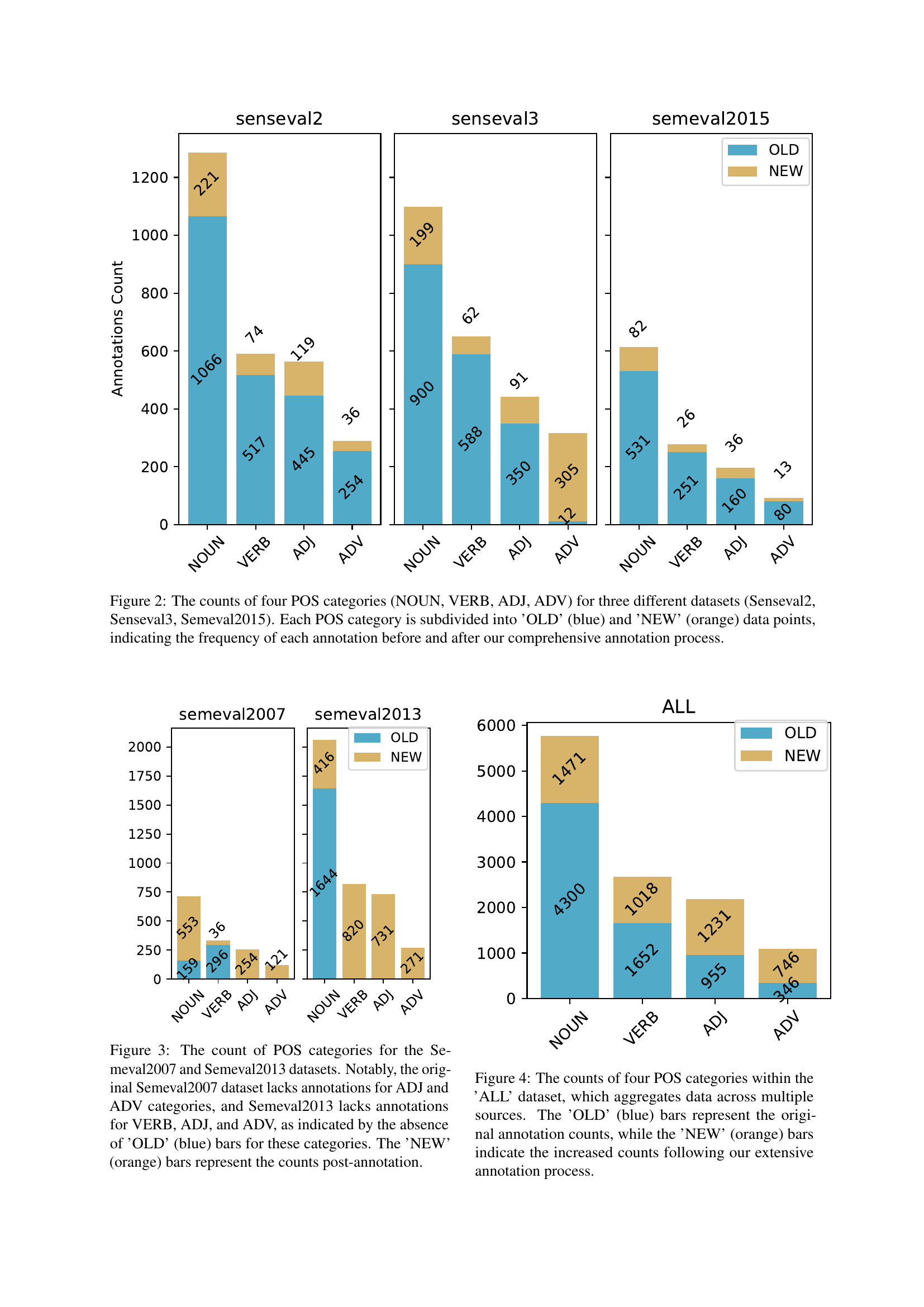

🔼 This figure shows the counts of four parts-of-speech (POS) categories (Noun, Verb, Adjective, Adverb) before and after annotation for the SemEval 2007 and SemEval 2013 datasets. The original datasets had missing annotations for certain POS tags; for example, SemEval 2007 lacked annotations for adjectives and adverbs, and SemEval 2013 lacked annotations for verbs, adjectives and adverbs. The blue bars represent the original (pre-annotation) counts and the orange bars represent the counts after the authors added annotations to address these gaps.

read the caption

Figure 3: The count of POS categories for the Semeval2007 and Semeval2013 datasets. Notably, the original Semeval2007 dataset lacks annotations for ADJ and ADV categories, and Semeval2013 lacks annotations for VERB, ADJ, and ADV, as indicated by the absence of ’OLD’ (blue) bars for these categories. The ’NEW’ (orange) bars represent the counts post-annotation.

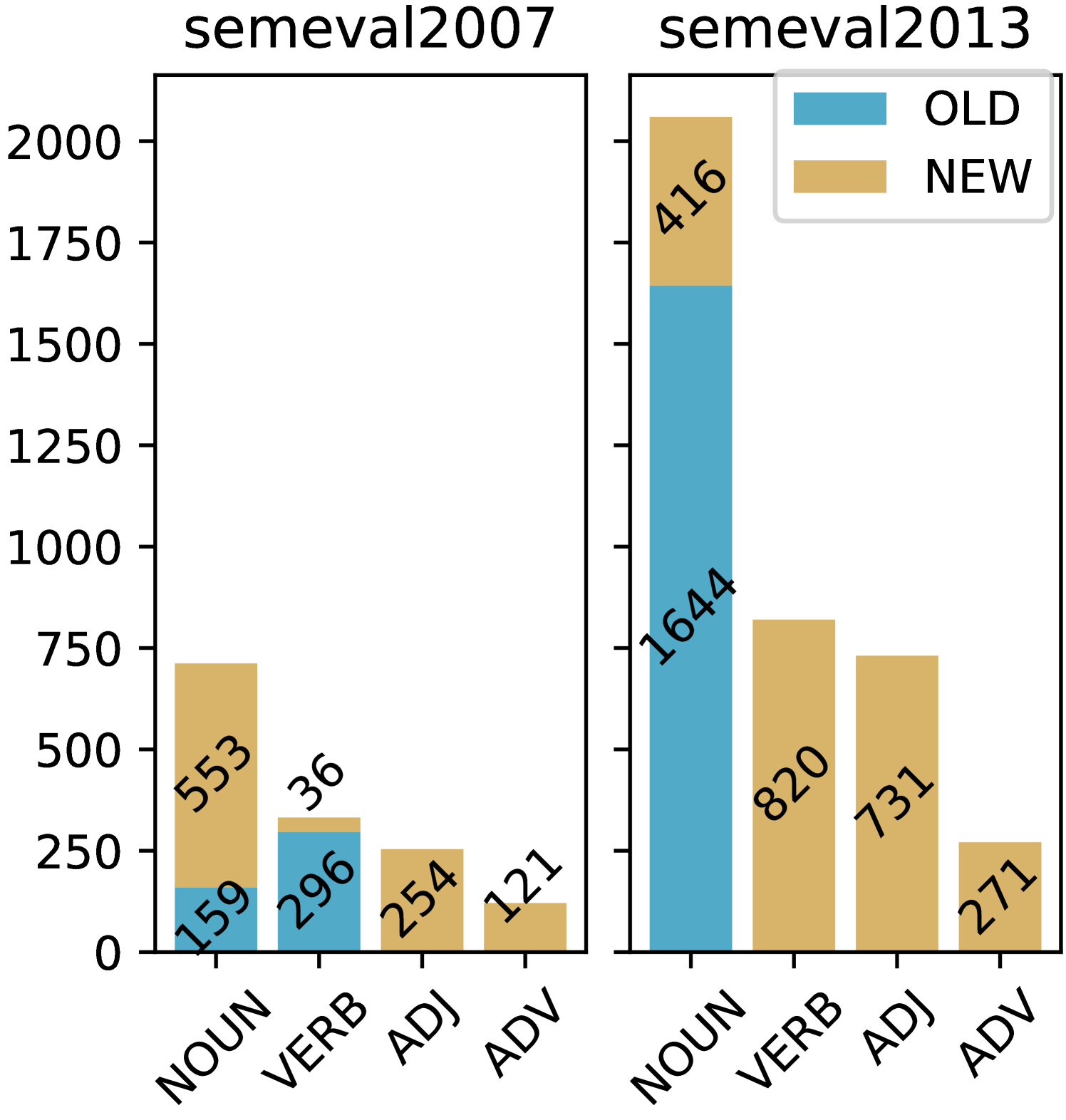

🔼 Figure 4 shows the number of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs in the combined dataset (ALL). The blue bars represent the original number of annotations in each POS category from the various source datasets. The orange bars show the significant increase in the number of annotations after the authors’ extensive annotation process, filling gaps in the original datasets.

read the caption

Figure 4: The counts of four POS categories within the ’ALL’ dataset, which aggregates data across multiple sources. The ’OLD’ (blue) bars represent the original annotation counts, while the ’NEW’ (orange) bars indicate the increased counts following our extensive annotation process.

More on tables

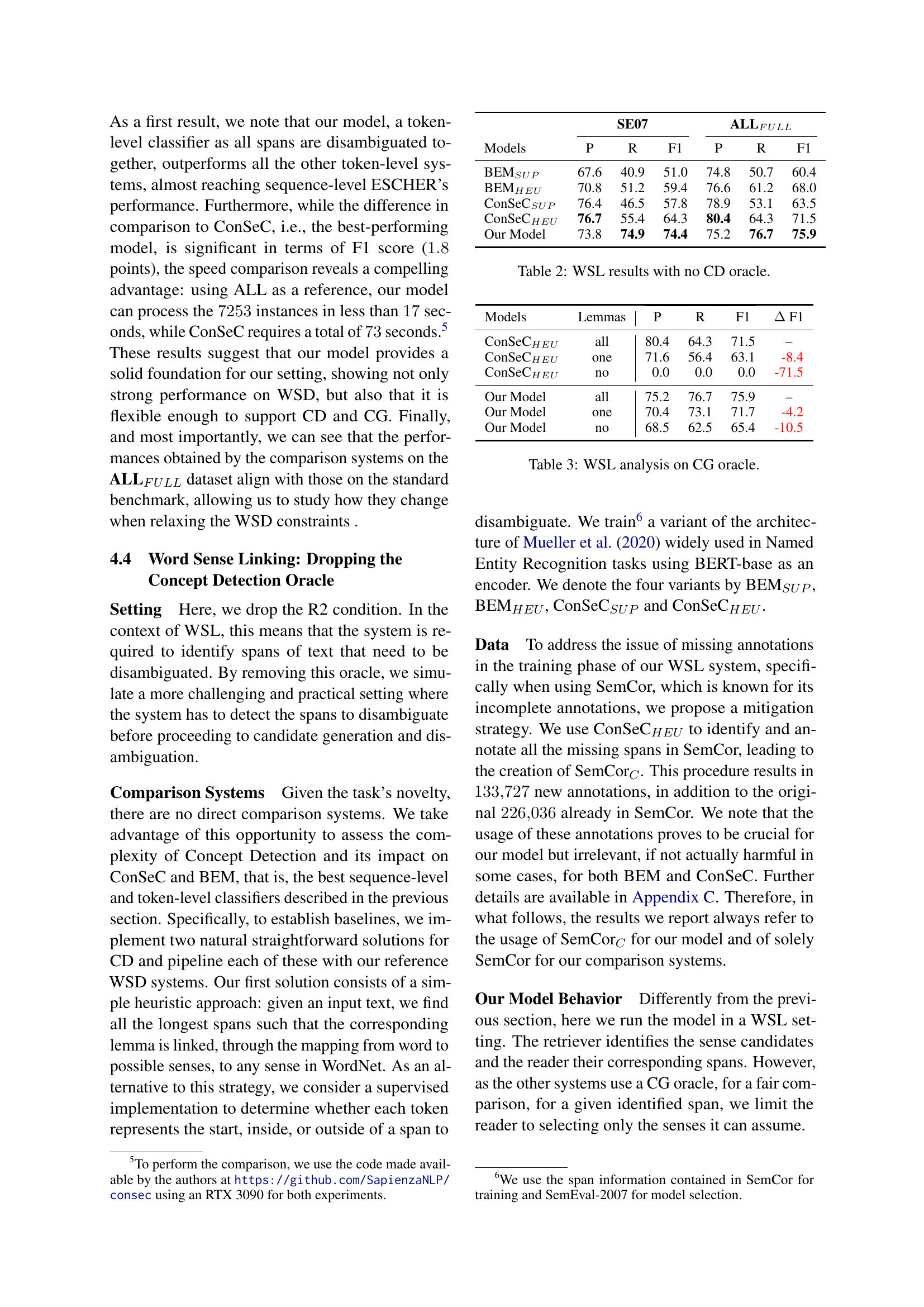

| Models | SE07 P | SE07 R | SE07 F1 | ALLFULL P | ALLFULL R | ALLFULL F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEMSUP | 67.6 | 40.9 | 51.0 | 74.8 | 50.7 | 60.4 |

| BEMHEU | 70.8 | 51.2 | 59.4 | 76.6 | 61.2 | 68.0 |

| ConSeCSUP | 76.4 | 46.5 | 57.8 | 78.9 | 53.1 | 63.5 |

| ConSeCHEU | 76.7 | 55.4 | 64.3 | 80.4 | 64.3 | 71.5 |

| Our Model | 73.8 | 74.9 | 74.4 | 75.2 | 76.7 | 75.9 |

🔼 This table presents the results of the Word Sense Linking (WSL) experiment conducted without the Concept Detection (CD) oracle. It compares the performance of different models, including ConSeC, BEM, and the proposed model, in the WSL setting where the system must identify the spans to disambiguate itself. The table shows Precision, Recall, and F1-score metrics for each model across the SE07 and ALLFULL datasets. It demonstrates the performance impact of removing the CD oracle from the standard WSD setting and highlights the robustness of the proposed model when compared to state-of-the-art WSD systems adapted to this challenging WSL setting.

read the caption

Table 2: WSL results with no CD oracle.

| Models | Lemmas | P | R | F1 | Δ F1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConSeCHEU | all | 80.4 | 64.3 | 71.5 | – | |

| ConSeCHEU | one | 71.6 | 56.4 | 63.1 | -8.4 | |

| ConSeCHEU | no | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -71.5 | |

| Our Model | all | 75.2 | 76.7 | 75.9 | – | |

| Our Model | one | 70.4 | 73.1 | 71.7 | -4.2 | |

| Our Model | no | 68.5 | 62.5 | 65.4 | -10.5 |

🔼 This table presents the results of the Word Sense Linking (WSL) experiment, focusing on the impact of relaxing the Candidate Generation (CG) oracle. It compares the performance of the proposed model and the ConSeCHEU system under three different conditions: 1. all: using all available lemmas. 2. one: using only the most frequent lemma for each sense. 3. no: using no lemmas at all. The comparison highlights how the models behave with increasingly limited CG information, demonstrating the robustness of the proposed model in scenarios where the CG oracle is incomplete or absent.

read the caption

Table 3: WSL analysis on CG oracle.

| Models | Params | ALL R@100 (Δ) |

|---|---|---|

| baseline | 109M | 96.5 |

| - bert-base-uncased | 109M | 88.7 (-7.8) |

| - E5_{small} | 33M | 94.2 (-2.3) |

| - just main lemma | 109M | 92.5 (-4.0) |

| - no lemma | 109M | 85.3 (-11.2) |

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the retriever module of a Word Sense Linking (WSL) model. The baseline model uses a BERT-base uncased architecture. Each row shows the results of modifying the baseline model. The changes include using different encoder architectures (E5small, bert-base-uncased), varying the textual representation of the senses in the inventory (using only the most frequent lemma or no lemma at all), and measuring the effect of these modifications on the model’s recall@100 (R@100) performance. The table highlights the impact of these changes on retrieval accuracy, indicating the importance of different design choices for the WSL system.

read the caption

Table 4: Results in terms of the ablation study on the Retriever Module. Each row represents a change made to the baseline model and the corresponding impact on performance.

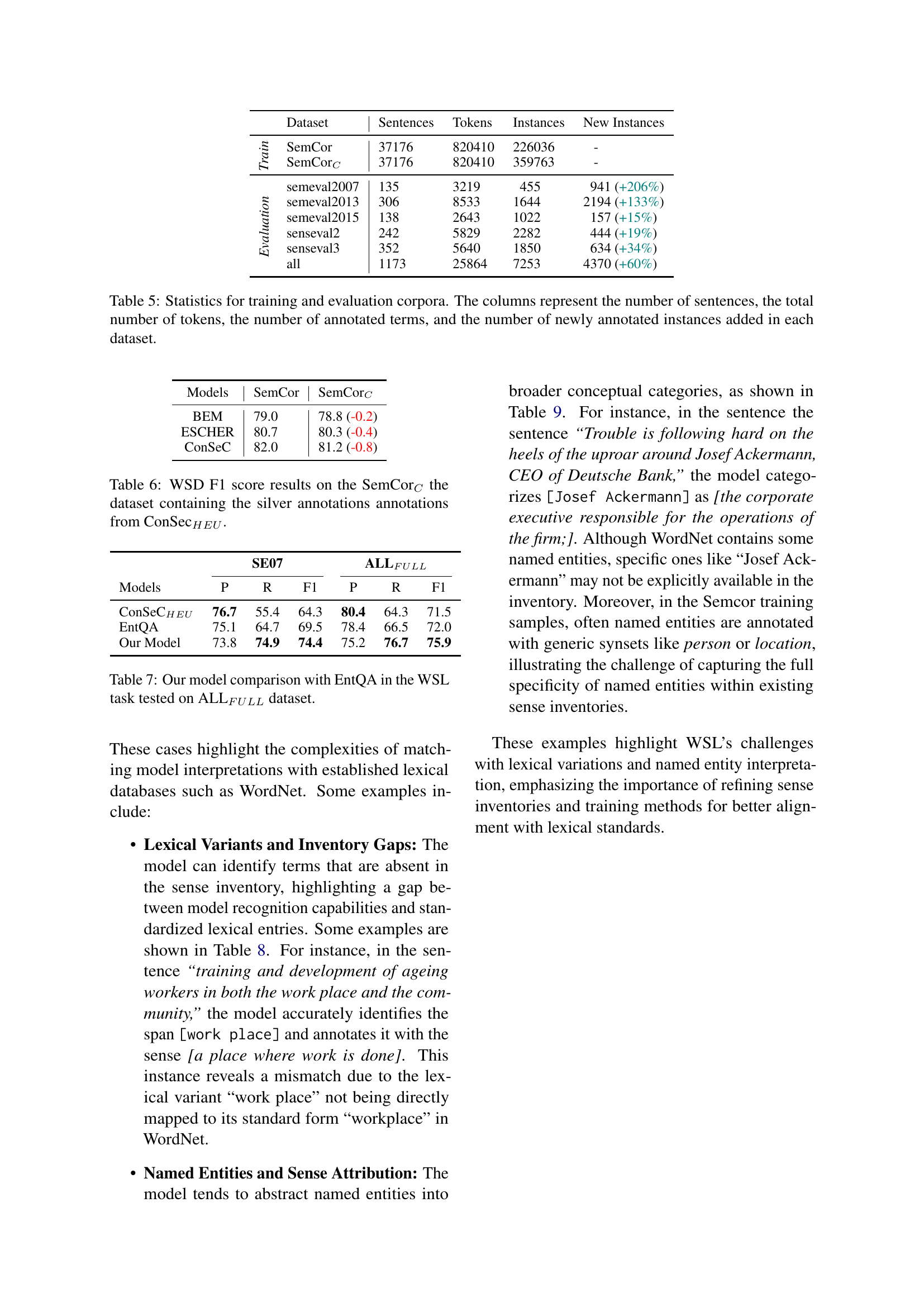

| Dataset | Sentences | Tokens | Instances | New Instances | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | SemCor | 37176 | 820410 | 226036 | - |

| SemCorC | 37176 | 820410 | 359763 | - | |

| Eval | semeval2007 | 135 | 3219 | 455 | 941 (+206%) |

| semeval2013 | 306 | 8533 | 1644 | 2194 (+133%) | |

| semeval2015 | 138 | 2643 | 1022 | 157 (+15%) | |

| senseval2 | 242 | 5829 | 2282 | 444 (+19%) | |

| senseval3 | 352 | 5640 | 1850 | 634 (+34%) | |

| all | 1173 | 25864 | 7253 | 4370 (+60%) |

🔼 Table 5 presents a detailed statistical overview of the training and evaluation corpora used in the Word Sense Linking (WSL) study. It breaks down the datasets into several key metrics: the original number of sentences, the total count of tokens (words and punctuation), the pre-existing number of annotated terms (spans of text associated with specific meanings), and crucially, the number of new annotated instances added as part of the current research. This last column is particularly important because it highlights the significant expansion of the datasets achieved through this work. This augmented annotation addresses gaps in previous datasets, improving the accuracy and overall quality of the WSL model evaluation.

read the caption

Table 5: Statistics for training and evaluation corpora. The columns represent the number of sentences, the total number of tokens, the number of annotated terms, and the number of newly annotated instances added in each dataset.

| Models | SemCor | SemCorC |

|---|---|---|

| BEM | 79.0 | 78.8 (-0.2) |

| ESCHER | 80.7 | 80.3 (-0.4) |

| ConSeC | 82.0 | 81.2 (-0.8) |

🔼 This table presents the Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD) F1 scores achieved by different models on the SemCorC dataset. SemCorC is a version of the SemCor dataset that includes additional annotations generated by the ConSeC HEU model, to address the issue of missing annotations in the original dataset. The F1 score, a metric that balances precision and recall, provides a comprehensive measure of the models’ accuracy in assigning the correct word sense to each word.

read the caption

Table 6: WSD F1 score results on the SemCorC the dataset containing the silver annotations annotations from ConSecHEU.

| Models | SE07 P | SE07 R | SE07 F1 | ALLFULL P | ALLFULL R | ALLFULL F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ConSeCHEU | 76.7 | 55.4 | 64.3 | 80.4 | 64.3 | 71.5 |

| EntQA | 75.1 | 64.7 | 69.5 | 78.4 | 66.5 | 72.0 |

| Our Model | 73.8 | 74.9 | 74.4 | 75.2 | 76.7 | 75.9 |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed WSL model against the EntQA model. Both models were evaluated on the ALLFULL dataset using the Word Sense Linking (WSL) task. The table shows the precision, recall, and F1-score achieved by each model. The results highlight the superior performance of the proposed model in terms of overall F1-score, recall, and efficiency.

read the caption

Table 7: Our model comparison with EntQA in the WSL task tested on ALLFULL dataset.

| Example Text | WSL disambiguation |

|---|---|

| Training and development of ageing workers in both the workplace and the community. | a place where work is done |

| In the amount USD 45 billion (nearly EUR 30 billion) in one go. | the basic monetary unit of most members of the European Union |

| Auditors found crookery the first day on the job. | verbal misrepresentation intended to take advantage of you in some way |

| Played on the 23rd of November against Ajax in European Champions League | - any number of entities (members) considered as a unit; |

| - an active diversion requiring physical exertion and competition | |

| Ctrl Q Quit Shuts the program. | cease to operate or cause to cease operating |

🔼 This table presents examples where the model successfully disambiguates words, highlighting instances of lexical variants that are not directly mapped in standard sense inventories like WordNet. It demonstrates the model’s ability to handle such variations, and simultaneously points out limitations in the sense inventory itself, where certain forms or nuances are missing.

read the caption

Table 8: This table showcases examples of model’s disambiguation capabilities and lexical recognition gaps, showing specific instances where the model accurately identifies and annotates lexical variants not directly mapped in standard sense inventories

| Example Text | WSL disambiguation |

|---|---|

| Trouble is following hard on the heels of the uproar around Josef Ackermann, CEO of Deutsche Bank. | the corporate executive responsible for the operations of the firm; |

| In his program, François Hollande confines himself to banalities. | a human being |

| The World Labor Organisation estimates that for example in Germany.. | an international alliance involving many different countries |

| Friendly game today, at 3:05 pm at the National Stadium in San Jose. | location, a point or extent in space |

| The two justices have been attending Federalist Society events for years. | any number of entities (members) considered as a unit |

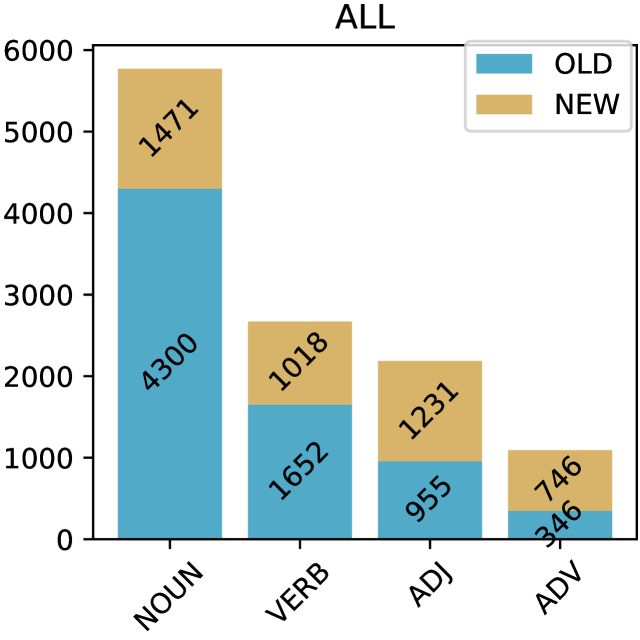

🔼 This table presents instances where the model’s word sense disambiguation (WSD) output for named entities is categorized under broader conceptual categories in WordNet, rather than being linked to their specific entries. Each row provides an example sentence, the identified named entity, and how the model classified it within WordNet’s hierarchy. This demonstrates the model’s tendency to generalize named entities, which may reflect either limitations of WordNet’s coverage or the model’s preference for higher-level classifications.

read the caption

Table 9: This table showcases examples of how the model abstracts named entities into broader conceptual categories. Each row shows the model’s disambiguation of specific named entities.

Full paper#