↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) allows multiple parties to collaboratively train a shared machine learning model on datasets with different features without directly sharing raw data. However, VFL is still susceptible to privacy attacks, like feature reconstruction, where attackers attempt to rebuild the private data. Existing attacks, like Model Inversion and Feature-space Hijacking, exploit knowledge of the data distribution and focus on models using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). These attacks work by accessing the model’s architecture or utilizing an auxiliary public dataset to infer the private data.

This paper demonstrates that a simple change in model architecture can significantly enhance data protection in VFL. The researchers theoretically and empirically prove that Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), networks made up of simple interconnected layers, are robust to feature reconstruction attacks, particularly state-of-the-art attacks like Model Inversion and Feature-space Hijacking. They highlight that these attacks are successful mostly because they use prior knowledge about the data distribution and CNNs lack specific architectural properties that MLPs possess. This work theoretically explains this behaviour and provides experiments confirming their results, suggesting that MLPs offer an effective defense mechanism against feature reconstruction attacks by themselves and do not require additional complex changes to their privacy-preserving structure.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This work has significant implications for privacy in Vertical Federated Learning (VFL). By demonstrating the resilience of MLP-based models to feature reconstruction attacks, it challenges the current focus on complex cryptographic and obfuscation methods. This opens new avenues for simpler, more efficient privacy-preserving techniques in VFL and encourages researchers to reconsider architectural design choices for enhanced privacy. It also highlights the limitations of certain attack strategies and the importance of evaluating privacy risks using human-centric metrics like FID.

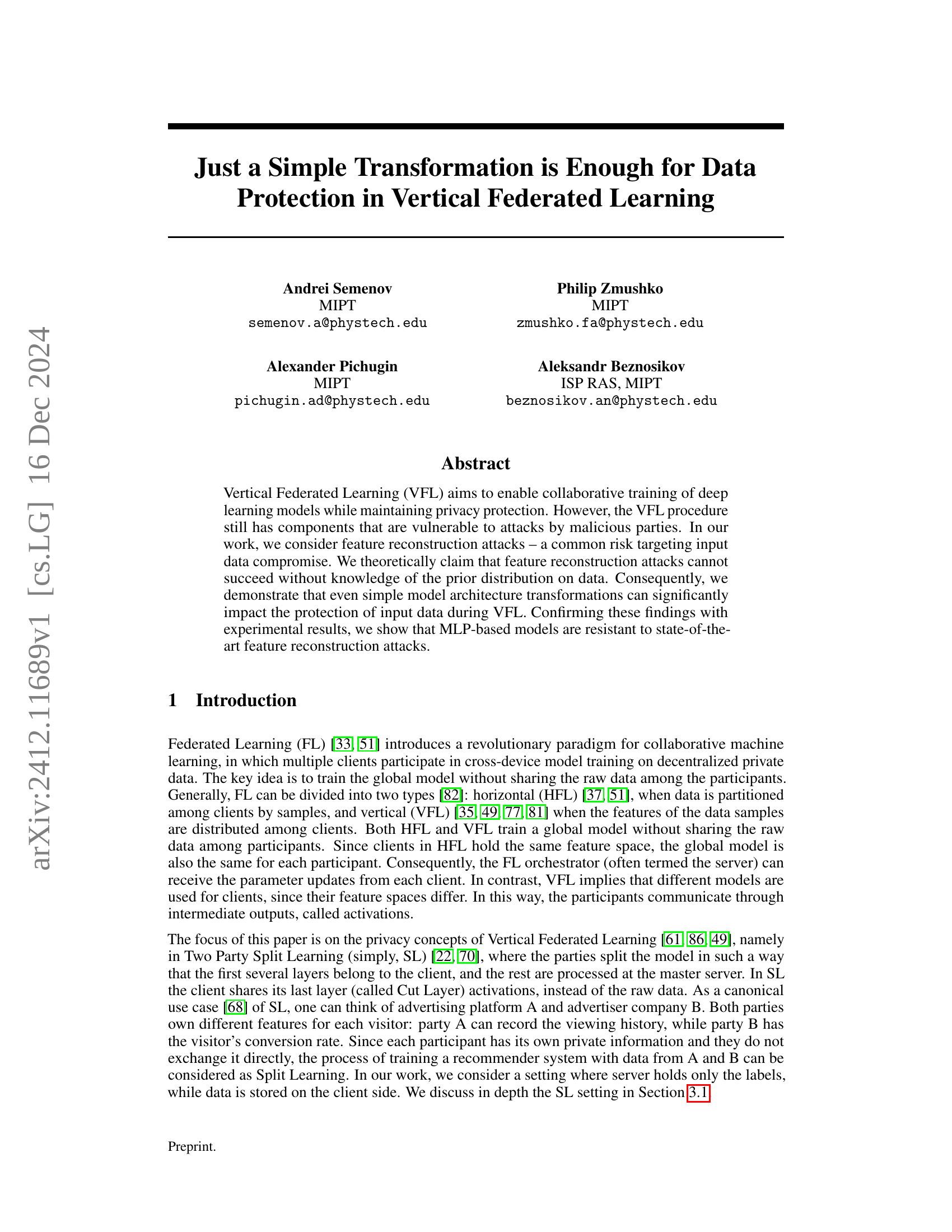

Visual Insights#

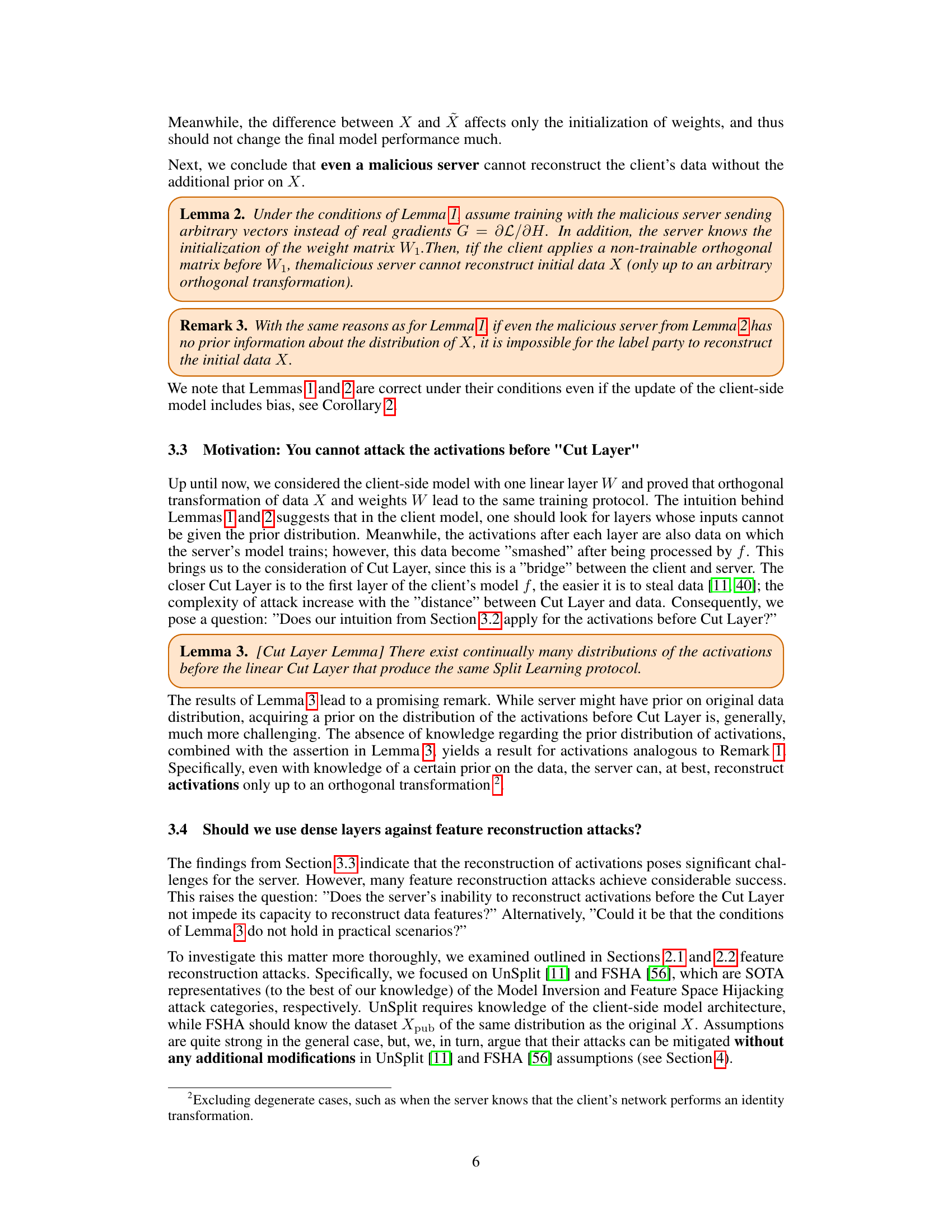

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the UnSplit attack’s effectiveness on MNIST data when employing different client-side models in a split learning setup. The top row displays the original MNIST images. The middle row showcases the reconstructed images when a CNN-based model is used on the client-side. Lastly, the bottom row reveals the reconstructed images when an MLP-based model is used on the client-side. The key observation is the failure of the UnSplit attack to reconstruct meaningful images when using the MLP-based client model, suggesting improved privacy preservation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results of UnSplit attack on MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): MLP-based client model.

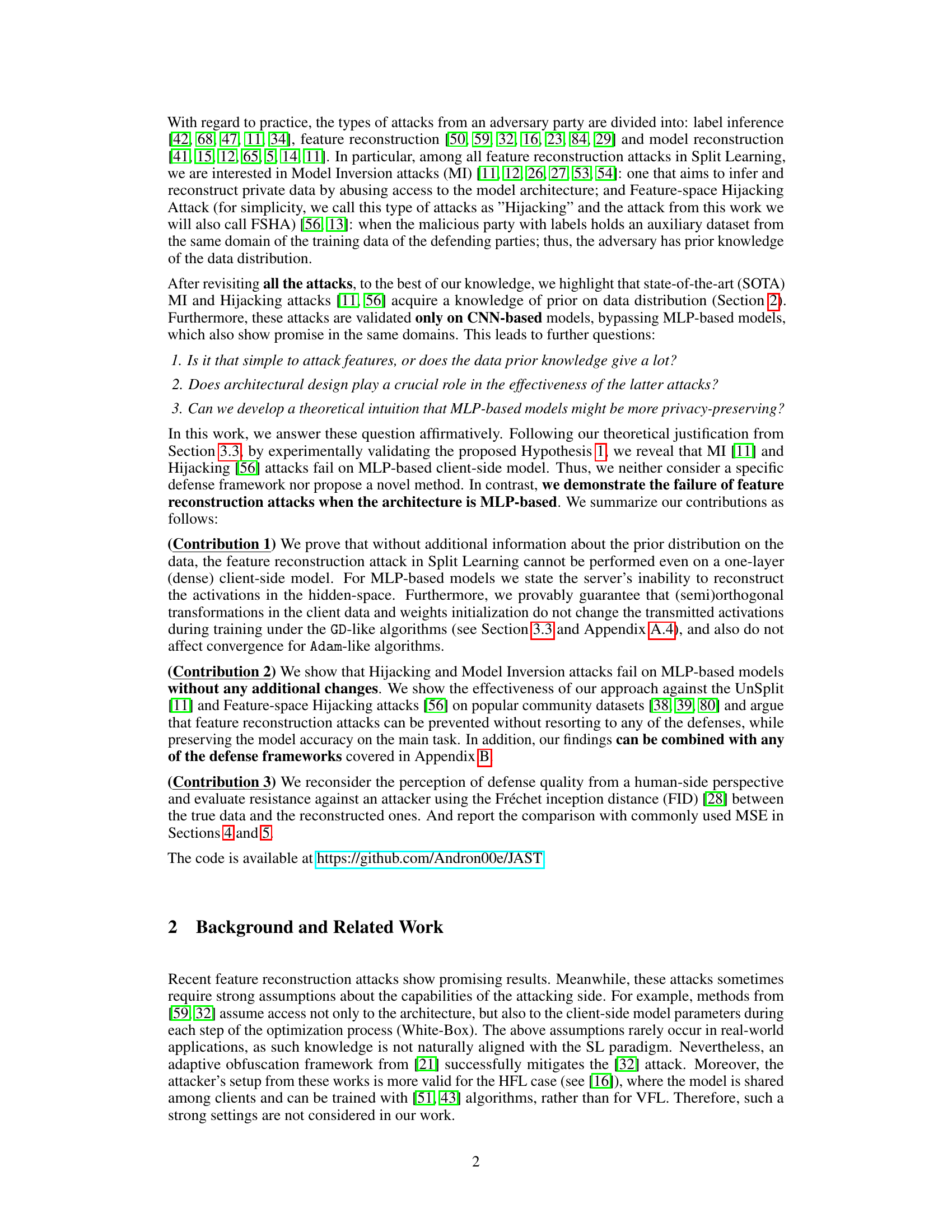

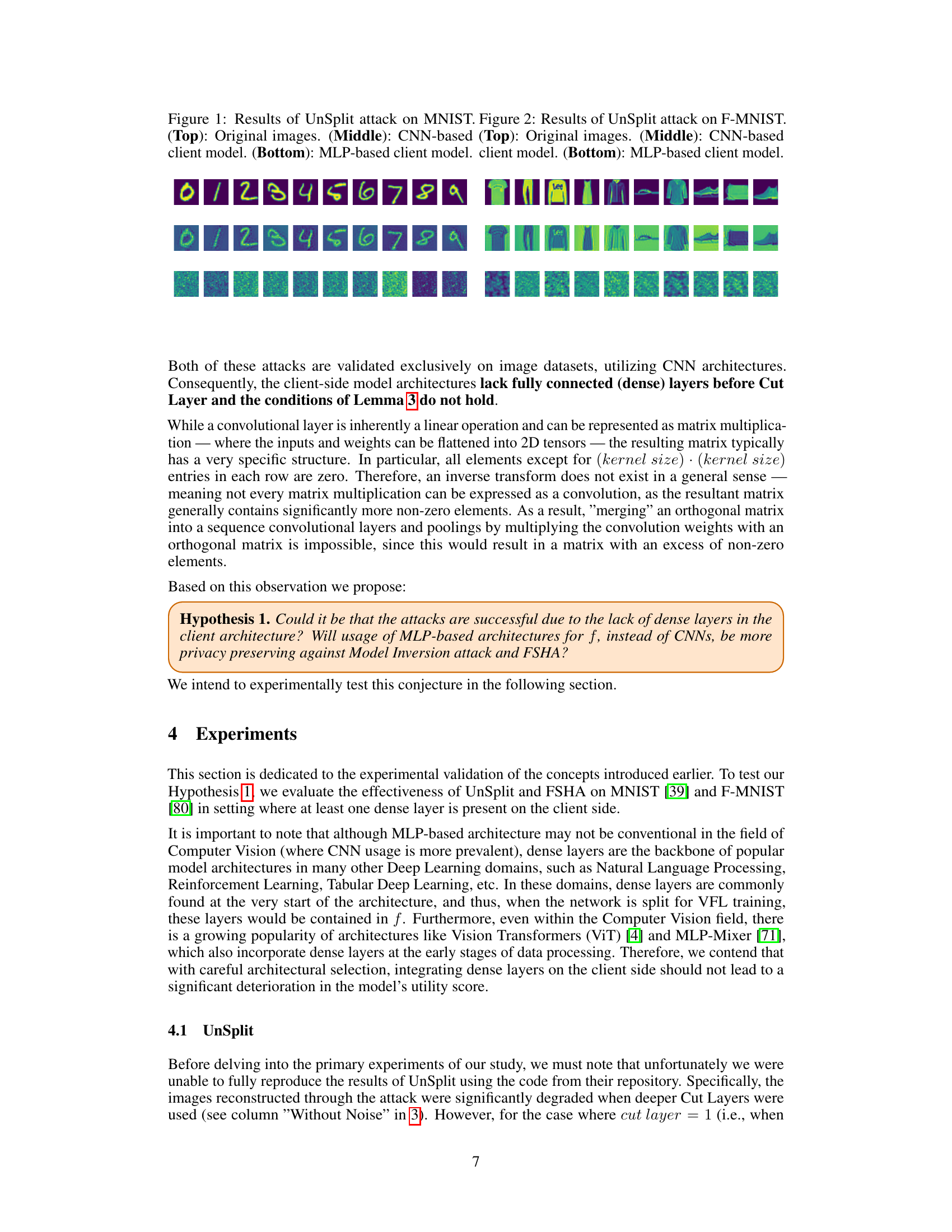

| Dataset | Model | MSE ([]mathcal{X}) | MSE ([]mathcal{Z}) | FID | Acc% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNIST | MLP-based | 0.27 | 3e-8 | 394 | 98.42% |

| MNIST | CNN-based | 0.05 | 2e-2 | 261 | 98.68% |

| F-MNIST | MLP-based | 0.19 | 4e-5 | 361 | 88.31% |

| F-MNIST | CNN-based | 0.37 | 4e-2 | 169 | 89.23% |

| CIFAR-10 | MLP-Mixer | 1.398 | 6e-6 | 423 | 89.29% |

| CIFAR-10 | CNN-based | 0.056 | 4e-3 | 455 | 93.61% |

🔼 This table presents the results of the UnSplit attack on image datasets MNIST, Fashion MNIST, and CIFAR-10. It compares the attack performance against both MLP-based and CNN-based client models using metrics such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) in the image space (MSE X), MSE in the activation space (MSE Z), Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), and the final accuracy of the trained models (Acc%). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of MLP-based models in resisting feature reconstruction attacks.

read the caption

Table 1: UnSplit attack on MNIST, F-MNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets.

In-depth insights#

VFL Data Privacy#

Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) aims to enhance data privacy during collaborative model training. It enables multiple parties with vertically partitioned data (different features for the same set of samples) to train a shared model without directly exchanging their raw data. However, VFL remains vulnerable to attacks such as feature reconstruction, model inversion, and label inference. Attackers exploit intermediate outputs (activations) or model architecture information to infer sensitive private data. Therefore, robust defense mechanisms are crucial for ensuring data protection in VFL. Several approaches exist, including adding noise (differential privacy), obfuscating data, and adversarial training. The effectiveness of these defenses depends on factors like noise levels, obfuscation techniques, and the specific attack model. Architectural design also plays a significant role in VFL privacy. Using MLP-based models for the client-side can improve data protection against some attacks, hindering feature reconstruction attempts. Further research is needed to develop more advanced defense strategies, address vulnerabilities of different architectures, and balance privacy with model utility in VFL.

Transformation Protection#

Analyzing data protection in Vertical Federated Learning (VFL), specifically focusing on feature reconstruction attacks, reveals that simple transformations can significantly enhance data privacy. Prior knowledge of data distribution is crucial for these attacks to succeed. Remarkably, MLP-based models demonstrate resilience against state-of-the-art attacks like Model Inversion and Feature-space Hijacking. This resilience stems from the inherent nature of dense layers within MLPs, disrupting the attacker’s ability to reconstruct activations, thereby protecting the original data. This observation highlights a potential shift in architectural design for privacy preservation in VFL, emphasizing the importance of MLPs or the inclusion of dense layers within existing architectures.

MLP-based VFL#

MLP-based VFL leverages Multilayer Perceptrons for vertical federated learning. This approach is particularly relevant where data features are distributed among multiple parties. Using MLPs offers an advantage: resistance to feature reconstruction attacks, like Model Inversion and Feature-Space Hijacking, which commonly exploit CNN vulnerabilities. This robustness stems from the dense layer structure in MLPs, disrupting the attacker’s ability to infer private data. Consequently, MLP-based VFL enhances privacy without complex cryptographic methods, simplifying implementation and reducing computational overhead while maintaining accuracy. Notably, the effectiveness extends even to simple MLP structures, highlighting its practicality. Further research could explore its potential in diverse domains beyond image datasets where MLPs are prevalent, like NLP and tabular learning.

Attack Failures#

Analyzing attack failures reveals critical insights into system vulnerabilities and defense strategies. A deep dive into unsuccessful attacks helps pinpoint specific weaknesses exploited. This understanding allows for targeted strengthening of defenses, prioritizing areas with demonstrated vulnerability. Moreover, studying attack failures can uncover novel attack vectors that were previously unknown. Examining the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) employed in failed attacks allows defenders to anticipate and proactively mitigate future threats. By understanding the reasons behind attack failures, such as detection mechanisms or system resilience, organizations can improve their overall security posture. This knowledge informs resource allocation, prioritizing defenses that have proven effective. Furthermore, studying attack failures encourages a proactive mindset, shifting from reactive responses to anticipatory defense. This includes continuous monitoring, vulnerability scanning, and penetration testing to identify and address weaknesses before they are successfully exploited.

Defense Quality#

Evaluating defense effectiveness against feature reconstruction attacks requires a human-centric approach. While MSE is commonly used, it doesn’t align well with human perception of image quality. FID offers a more perceptually aligned metric, reflecting how humans perceive differences between real and reconstructed images. This shift is crucial for assessing privacy risks, as a defense deemed successful by MSE might still reveal sensitive information discernible by humans. Therefore, FID provides a more robust evaluation of how well a defense truly safeguards against data leakage.

More visual insights#

More on figures

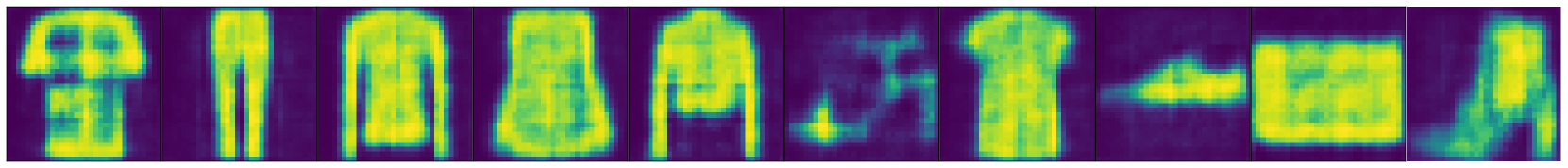

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the UnSplit attack’s effectiveness on Fashion-MNIST data when employed against two different client model architectures in a Split Learning setup. The top row displays the original Fashion-MNIST images. The middle row shows the reconstructed images when a CNN-based model is used on the client-side. The bottom row presents the reconstructed images when an MLP-based model is employed on the client-side. As can be seen, the CNN-based client model is vulnerable to the attack. The MLP-based client model, however, is resistant, with the attack failing to recover any meaningful representation of the original data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Results of UnSplit attack on F-MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): MLP-based client model.

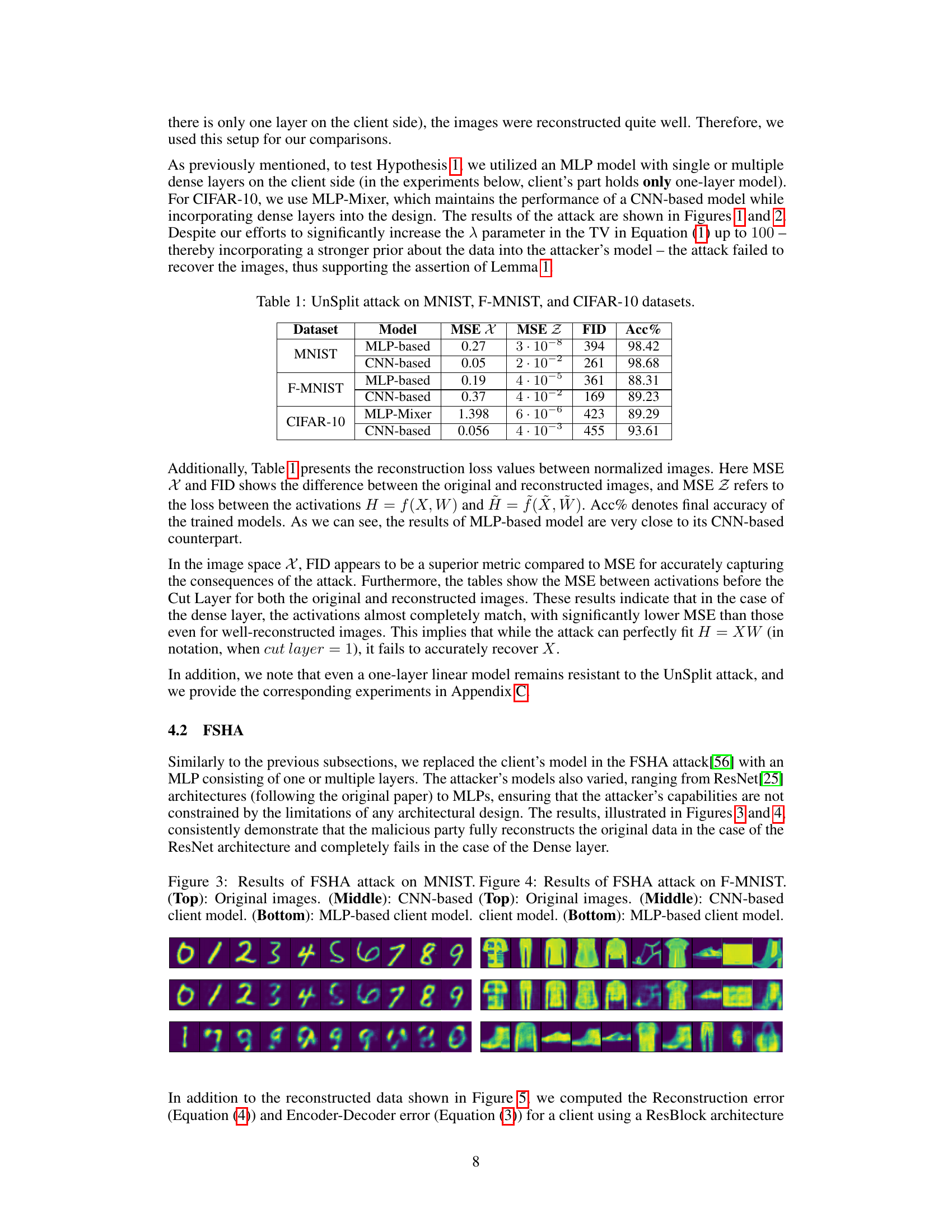

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the Feature-space Hijacking Attack (FSHA) performance on the MNIST dataset under two different client model architectures: a CNN-based model and an MLP-based model. The top row displays the original MNIST images. The middle row shows the reconstructed images when the client model uses a CNN architecture. The bottom row illustrates the attack outcome when using an MLP-based client model. The figure aims to visually demonstrate the effectiveness of FSHA against these two architectures by comparing the quality of the reconstructed images. As shown in the figure, the attack achieves higher reconstruction quality with the CNN client model and fails when the client-side architecture contains dense layers.

read the caption

Figure 3: Results of FSHA attack on MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): MLP-based client model.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the Feature-space Hijacking Attack (FSHA) on the Fashion-MNIST (F-MNIST) dataset with different client model architectures. The top row displays the original images. The middle row shows the reconstructed images when the client model is a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The bottom row shows the reconstructed images when the client model is a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). The comparison demonstrates that FSHA is effective in reconstructing the original images when a CNN is used but fails when an MLP is used, highlighting the vulnerability of CNN-based client models and the robustness of MLP-based client models to this specific attack.

read the caption

Figure 4: Results of FSHA attack on F-MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): MLP-based client model.

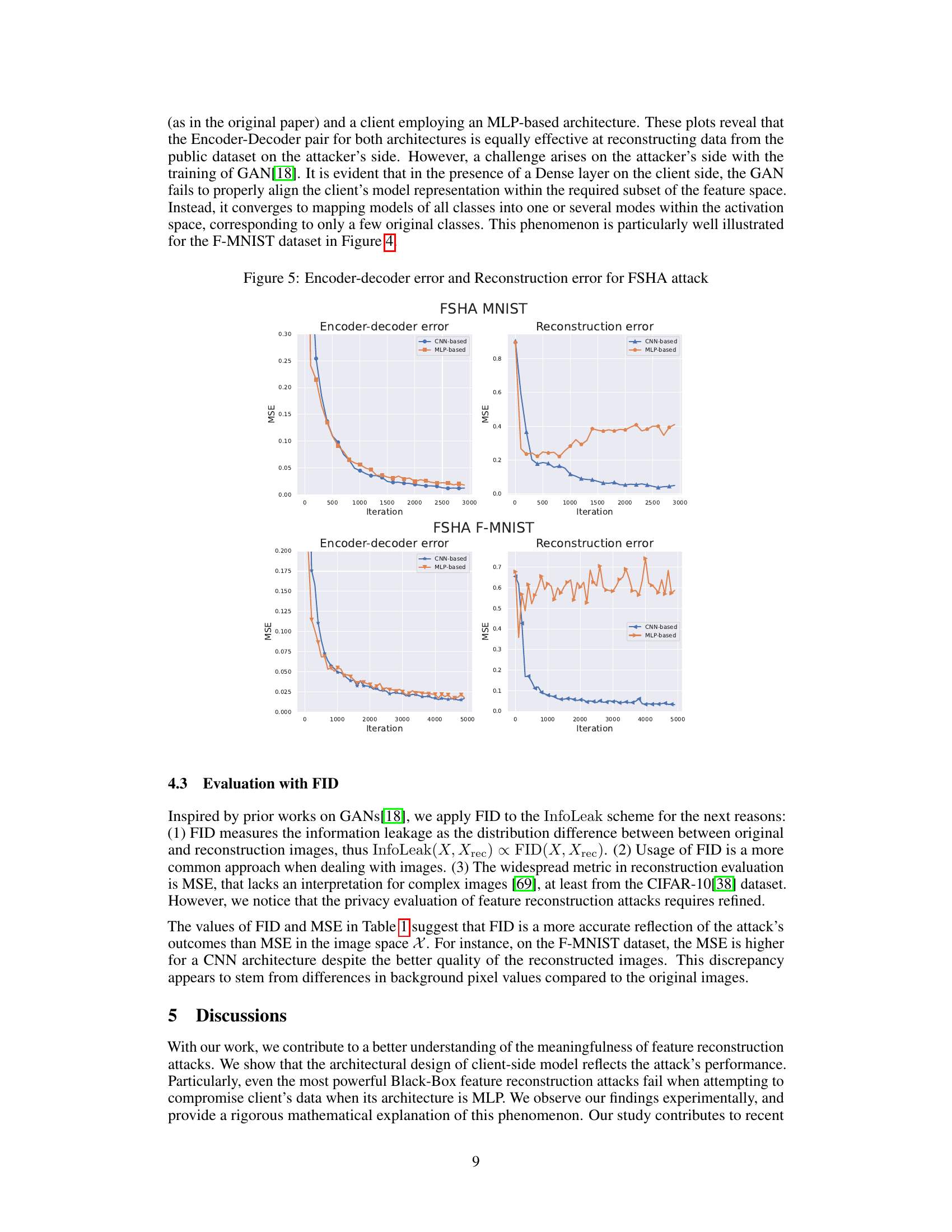

🔼 This figure presents the Encoder-Decoder error and the Reconstruction error for the Feature-space Hijacking Attack (FSHA). The Encoder-Decoder error represents the mean squared error (MSE) between the original images from a public dataset and the images reconstructed using an encoder-decoder model. The Reconstruction error, on the other hand, denotes the MSE between the original private data held by the client and the data reconstructed by the attacker (server) using the client’s model activations. The figure showcases these errors for both CNN-based and MLP-based client models across MNIST and Fashion-MNIST (F-MNIST) datasets. It illustrates that the encoder-decoder pair performs equally well in reconstructing public data, irrespective of the client’s model architecture. However, the attack’s success in reconstructing private data significantly depends on the client-side architecture, with MLP-based models demonstrating greater resistance to reconstruction.

read the caption

Figure 5: Encoder-decoder error and Reconstruction error for FSHA attack

🔼 Figure 6 presents a comparison of the UnSplit attack’s effectiveness on CIFAR-10 images when employing two different client model architectures within the Split Learning framework. The top row displays the original CIFAR-10 images. The middle row showcases the reconstructed images when a CNN-based model is used on the client-side. The bottom row presents the reconstructed images when an MLP-Mixer model is used on the client-side. The figure visually demonstrates that using the MLP-Mixer model, which incorporates dense layers, makes the UnSplit attack ineffective at reconstructing the original images, supporting Hypothesis 1 of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 6: Results of UnSplit attack on CIFAR-10. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): MLP-Mixer client model.

🔼 This figure demonstrates how the Adam optimizer’s performance can be affected by initialization when applied to the non-convex function f(y) = y² + 6sin²(y), where y = WᵀX. The plot shows the function’s value over optimization steps for two different initializations of W and X. The ‘before rotation’ line represents the optimization path with the original initialization, converging towards the global minimum at y = 0. The ‘after rotation’ line shows the optimization path after applying an orthogonal transformation to both W and X. In this scenario, the optimizer gets stuck in a local minimum, failing to reach the global optimum. This illustrates that for non-convex functions, the behavior of Adam, and potentially other adaptive optimizers, can be sensitive to the initial values of the weights and data.

read the caption

Figure 7: While optimizing the non-convex function f(x)𝑓𝑥f(x)italic_f ( italic_x ), Adam can get stuck in the local minima in depence on the initialization.

🔼 This figure presents Mean Squared Error (MSE) results across different classes for the UnSplit attack on three datasets: CIFAR-10, F-MNIST, and MNIST. The top row shows results on CIFAR-10 using both an MLP-Mixer and a CNN-based client model. The middle row displays results on F-MNIST with MLP and CNN-based client models. The bottom row presents results on MNIST also with MLP and CNN-based client models. Each plot within the rows shows the MSE for both the reconstructed image (Reconstruction MSE) and the intermediate activations at the cut layer (Cut Layer MSE). This allows for a comparison of the error in both the input space and the latent space at the cut layer for each class in the respective dataset.

read the caption

Figure 8: MSE across different classes for the UnSplit attack. (Top row): CIFAR-10 – MLP-Mixer and CNN-based models. (Middle row): F-MNIST – MLP and CNN-based models. (Bottom row): MNIST – MLP and CNN-based models.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the UnSplit attack’s reconstruction capabilities on the MNIST dataset, showcasing the impact of client-side model architecture. The top row displays the original MNIST images. The middle row illustrates the reconstructed images when the client utilizes a CNN-based model, while the bottom row shows the results when the client employs a smaller MLP-based model (SmallMLP) designed to have a similar number of parameters as the CNN. Notably, even with this smaller MLP model, the UnSplit attack struggles to reconstruct meaningful images, aligning with the paper’s core argument about the resistance of MLP-based architectures to such attacks.

read the caption

Figure 9: Results of UnSplit attack on MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): SmallMLP client model.

🔼 Figure 10 shows the reconstruction results of the UnSplit attack on the Fashion-MNIST (F-MNIST) dataset. The top row displays the original images. The middle row presents the reconstructions when a CNN-based model is used on the client-side, which in this case results in almost perfect reconstruction of the input data. The bottom row shows the reconstructions when a much smaller MLP-based model (SmallMLP) is used on the client-side. As expected by the theory presented in the paper, the attacker cannot succeed against SmallMLP, highlighting that the usage of simple transformations (like usage of MLP instead of CNN) can be enough for data protection in Vertical Federated Learning.

read the caption

Figure 10: Results of UnSplit attack on F-MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): SmallMLP client model.

🔼 This figure presents the results of the Feature Space Hijacking Attack (FSHA) on the MNIST dataset. The top row displays the original MNIST images. The middle row shows the reconstructed images when a CNN-based model is used on the client-side. The bottom row presents the reconstructed images when a smaller MLP-based model (SmallMLP) is used on the client-side. As can be seen, the FSHA attack successfully reconstructs the original images when the client uses a CNN-based model. However, it completely fails when the client model is a SmallMLP model.

read the caption

Figure 11: Results of FSHA attack on MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): SmallMLP client model.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the Feature-space Hijacking Attack (FSHA) results on the Fashion-MNIST (F-MNIST) dataset with two different client models. The top row displays the original images from the dataset. The middle row shows the reconstruction results when a CNN-based model is used on the client-side. The bottom row shows the results when a smaller MLP-based model (SmallMLP) is used on the client side. SmallMLP is not as accurate as the four-layer MLP in other experiments but is designed to match CNN’s number of parameters. As demonstrated, the CNN client model allows near-perfect reconstruction of the private data by the malicious server, while the MLP-based model effectively thwarts the attack.

read the caption

Figure 12: Results of FSHA attack on F-MNIST. (Top): Original images. (Middle): CNN-based client model. (Bottom): SmallMLP client model.

More on tables

| # Parameters / Model | MLP | MLP-Mixer | CNN | SmallMLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | 2,913,290 | 146,816 | 45,278 | 7,850 |

🔼 This table, located in Section 4, compares the number of parameters across different models used in the experiments: a four-layer MLP, an MLP-Mixer, a CNN, and a two-layer MLP (SmallMLP). The SmallMLP is designed to have a comparable number of parameters to the CNN while having reduced accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Number of parameters for different models across.

| Split Layer # | Without noise | With Noise |

|---|---|---|

| Ref. | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x36.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x37.png) |

| 1 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x38.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x39.png) |

| 2 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x40.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x41.png) |

| 3 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x42.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x43.png) |

| 4 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x44.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x45.png) |

| 5 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x46.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x47.png) |

| 6 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x48.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x49.png) |

| Ref. | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x50.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x51.png) |

| 1 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x52.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x53.png) |

| 2 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x54.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x55.png) |

| 3 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x56.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x57.png) |

| 4 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x58.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x59.png) |

| 5 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x60.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x61.png) |

| 6 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x62.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x63.png) |

| Ref. | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x64.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x65.png) |

| 1 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x66.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x67.png) |

| 2 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x68.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x69.png) |

| 3 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x70.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x71.png) |

| 4 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x72.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x73.png) |

| 5 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x74.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x75.png) |

| 6 | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x76.png) | ![[Uncaptioned image]](https://arxiv.org/html/2412.11689/x77.png) |

🔼 This table shows the results of reconstructing input images using the UnSplit attack with Differential Privacy (DP) defense, applied for various cut layers on MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets. The table compares the effectiveness of reconstruction with and without adding the DP noise. Each row represents a different split depth (cut layer), with ‘Ref.’ showing the original images. The DP noise variance (σ) is set differently for each dataset to balance privacy and utility. It’s worth noting that while the theoretical σ for CIFAR-10 is 7.1, it was lowered to 0.25 due to complications in training.

read the caption

Table 3: Estimated inputs with and without adding noise for various Cut Layers for the MNIST, F-MNIST, and CIFAR-10 datasets. The 'Ref.' row display the actual inputs, and the next rows display the attack results for different split depths. We took the following noise variance for different datasets: σ=1.6𝜎1.6\sigma=1.6italic_σ = 1.6 for MNIST, σ=2.6𝜎2.6\sigma=2.6italic_σ = 2.6 for F-MNIST, σ=0.25𝜎0.25\sigma=0.25italic_σ = 0.25 for CIFAR-10. Note that theoretical value of σ𝜎\sigmaitalic_σ for CIFAR-10 is 7.17.17.17.1, but we decided to lower it due to neural network learning issues.

Full paper#