↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) excel in complex tasks but there’s a difference between their performance on benchmarks and how well they do in real-world situations. Current evaluations often look at the best possible answer out of several tries (like choosing the best out of 10 attempts). This doesn’t show how consistent an LLM is, which is crucial for real-world use where reliable, predictable outcomes matter. Existing benchmarks might also be outdated or too easy due to data leakage (where the models has already seen some of the “test” data). This inconsistency poses challenges for real-world applications that need reliable and predictable performance.

This work tackles these issues with a two-pronged approach. First, they introduce G-Pass@k, a new evaluation metric. Instead of just looking at peak performance, G-Pass@k measures how often an LLM gives the right answer across multiple tries, showing both its best capability and its consistency. Second, they present LiveMathBench, a challenging new collection of up-to-date math problems, minimizing data leakage issues by incorporating latest problems from various mathematical competitions. Using G-Pass@k with LiveMathBench, the authors show that current LLMs, even the large ones, still have a long way to go in terms of consistent reasoning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper aids researchers in two key ways: 1) It introduces a new metric (G-Pass@k) that provides a continuous evaluation of LLM performance and stability, addressing a notable gap in existing evaluation methods which fail to capture consistency. 2) It offers a new benchmark dataset, LiveMathBench, of challenging, up-to-date mathematical problems to evaluate these advanced reasoning capabilities and consistency. It opens new avenues for developing more robust evaluation methods and for enhancing the “realistic” reasoning capabilities in complex tasks like mathematical problem-solving.

Visual Insights#

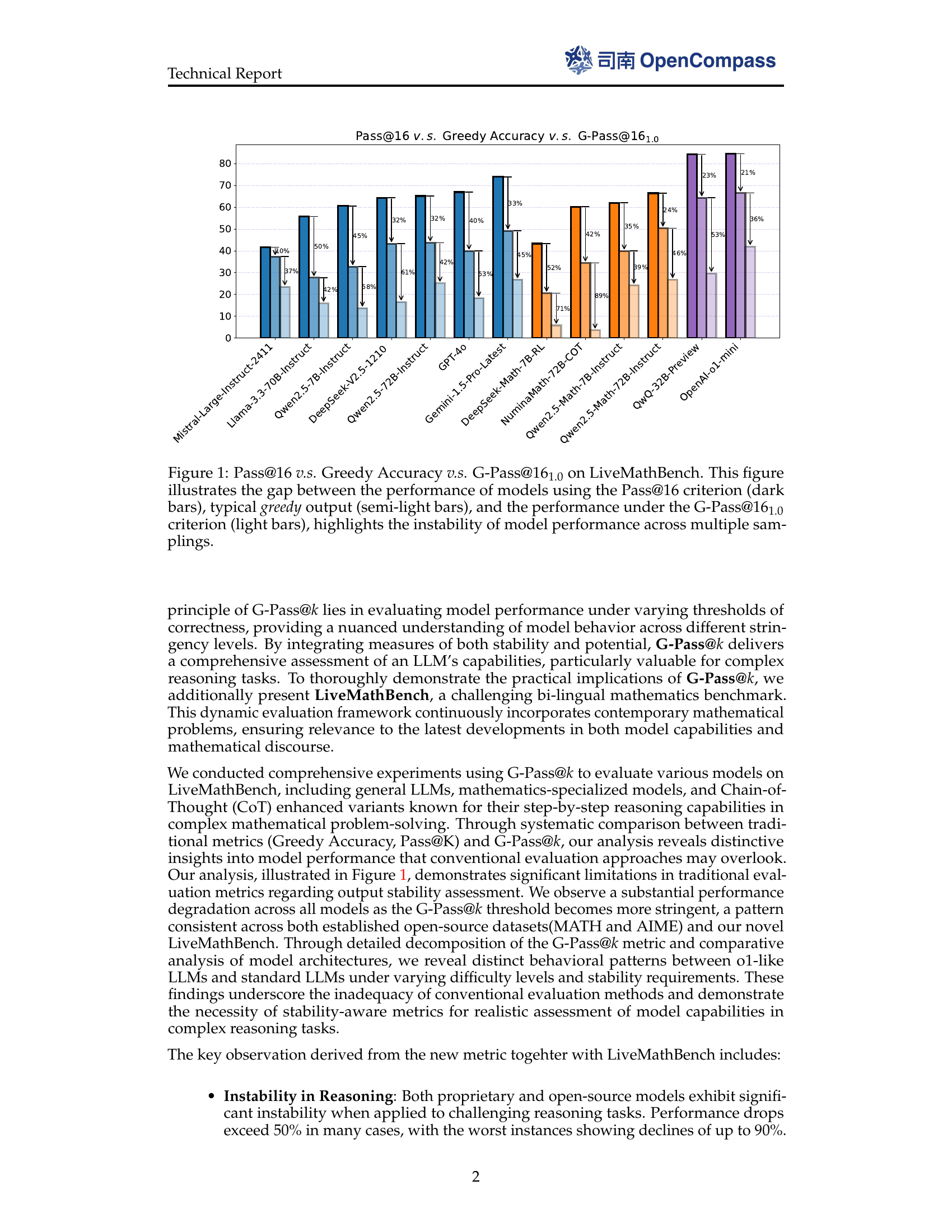

🔼 This figure compares the performance of several large language models (LLMs) on the LiveMathBench dataset using three different evaluation metrics: Pass@16, Greedy Accuracy, and G-Pass@16_1.0. Pass@16 represents the probability of getting the correct answer in 16 attempts. Greedy Accuracy refers to the accuracy of the model’s first attempt, without any sampling. G-Pass@16_1.0 measures the stability of the model by checking if it gets the correct answer in all 16 attempts. The figure uses a bar chart to show the scores for each model under each metric, highlighting the difference between peak potential (Pass@16) and consistent performance (G-Pass@16_1.0). The discrepancy between these metrics demonstrates the instability of LLM performance in complex reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Pass@16161616 v.s. Greedy Accuracy v.s. G-Pass@161.0subscript161.016_{1.0}16 start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1.0 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT on LiveMathBench. This figure illustrates the gap between the performance of models using the Pass@16Pass@16\text{Pass@}16Pass@ 16 criterion (dark bars), typical greedy output (semi-light bars), and the performance under the G-Pass@161.0G-Pass@subscript161.0\text{G-Pass@}16_{1.0}G-Pass@ 16 start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1.0 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT criterion (light bars), highlights the instability of model performance across multiple samplings.

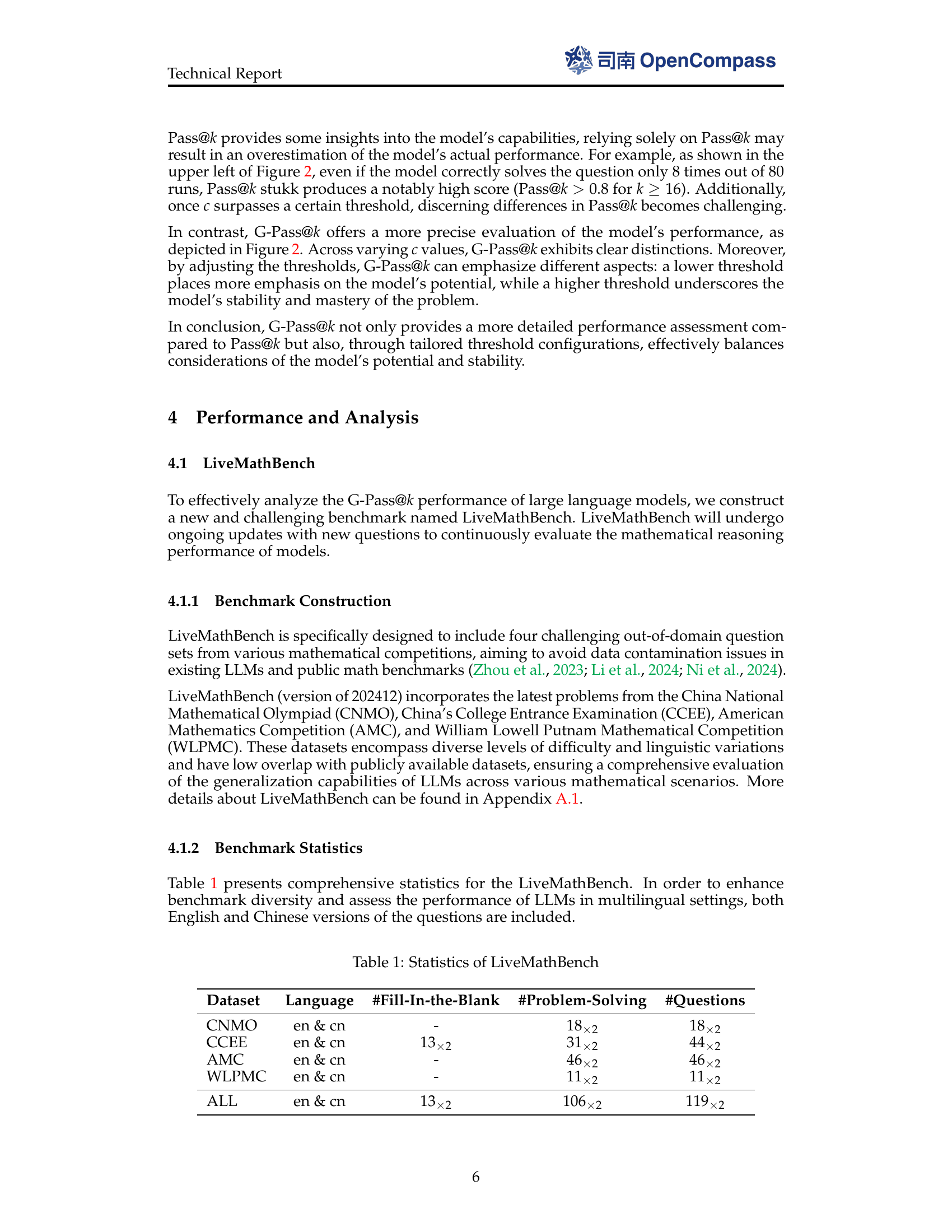

| Dataset | Language | #Fill-In-the-Blank | #Problem-Solving | #Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNMO | en & cn | - | 18×2 | 18×2 |

| CCEE | en & cn | 13×2 | 31×2 | 44×2 |

| AMC | en & cn | - | 46×2 | 46×2 |

| WLPMC | en & cn | - | 11×2 | 11×2 |

| ALL | en & cn | 13×2 | 106×2 | 119×2 |

🔼 This table presents the statistics of the LiveMathBench dataset, including the number of fill-in-the-blank and problem-solving questions for each subset (CNMO, CCEE, AMC, WLPMC) in both English and Chinese.

read the caption

Table 1: Statistics of LiveMathBench

In-depth insights#

LLM Reasoning Gaps#

LLM reasoning gaps reveal a disparity between benchmark performance and real-world application. While LLMs excel in controlled environments, their stability falters in dynamic scenarios. This instability stems from current evaluation metrics like greedy accuracy and Pass@k, which prioritize peak performance over consistent reasoning. The paper introduces G-Pass@k, a novel metric assessing both potential and stability across multiple samplings. This illuminates the discrepancy between theoretical capability and consistent accuracy. Moreover, merely increasing model size doesn’t guarantee improved stability, highlighting the need for evaluation methods focusing on robust, consistent reasoning rather than just peak performance.

G-Pass@k: Novel Metric#

The research paper introduces G-Pass@k, a novel metric designed to evaluate both the capability and consistency of Large Language Models (LLMs) in complex reasoning tasks, particularly mathematical problem-solving. Unlike traditional metrics like Pass@k or greedy accuracy, which primarily focus on peak performance or single-shot accuracy, G-Pass@k accounts for performance across multiple sampling attempts, providing a more realistic assessment of real-world LLM behavior where users often regenerate responses. It incorporates a threshold (τ) to measure performance under varying stringency levels, offering insights into both potential (τ→0) and stability (τ=1). This nuanced evaluation reveals a significant discrepancy between potential and stability in current LLMs, highlighting the need for developing more robust training and evaluation methods.

LiveMathBench Details#

LiveMathBench, a dynamic benchmark designed to rigorously evaluate large language models (LLMs), focuses on challenging mathematical reasoning. It incorporates diverse, contemporary problems from competitions like CNMO, CCEE, AMC, and WLPMC, minimizing data leakage. Single-choice questions are transformed into problem-solving tasks, requiring models to generate solutions. This benchmark’s continuous updates ensure ongoing assessment of LLM capabilities, reflecting advancements in model architectures and mathematical discourse. It serves as a robust evaluation tool for realistic reasoning proficiency, addressing the gap between benchmark results and real-world applications.

Model Instability Issues#

Model instability poses a significant challenge in real-world applications. Inconsistencies in model outputs, even with identical inputs, raise concerns about reliability. This instability stems from factors like random sampling during generation and model sensitivity to minor input variations. Evaluating instability requires metrics beyond single-point accuracy, emphasizing the need for methods like G-Pass@k to assess consistency across multiple generations. Furthermore, simply increasing model size doesn’t guarantee improved stability, indicating a need for architectural and training advancements that prioritize robustness alongside accuracy. This instability highlights a key discrepancy between potential and realized performance, limiting real-world effectiveness.

Overfitting & Stability#

Overfitting, while potentially boosting performance on familiar data, can undermine stability when encountering novel or diverse inputs. This trade-off is crucial in reasoning tasks where consistency is paramount. A model excelling on seen data but faltering on unseen data isn’t truly reliable. This highlights the danger of over-reliance on benchmark results, which may reflect overfitting rather than robust reasoning. Prioritizing stability requires careful consideration of training data, and using evaluation metrics that explicitly assess consistency across multiple samples, rather than just peak performance. This reinforces the need to balance accuracy with stability for real-world applications where dependable reasoning is essential.

More visual insights#

More on figures

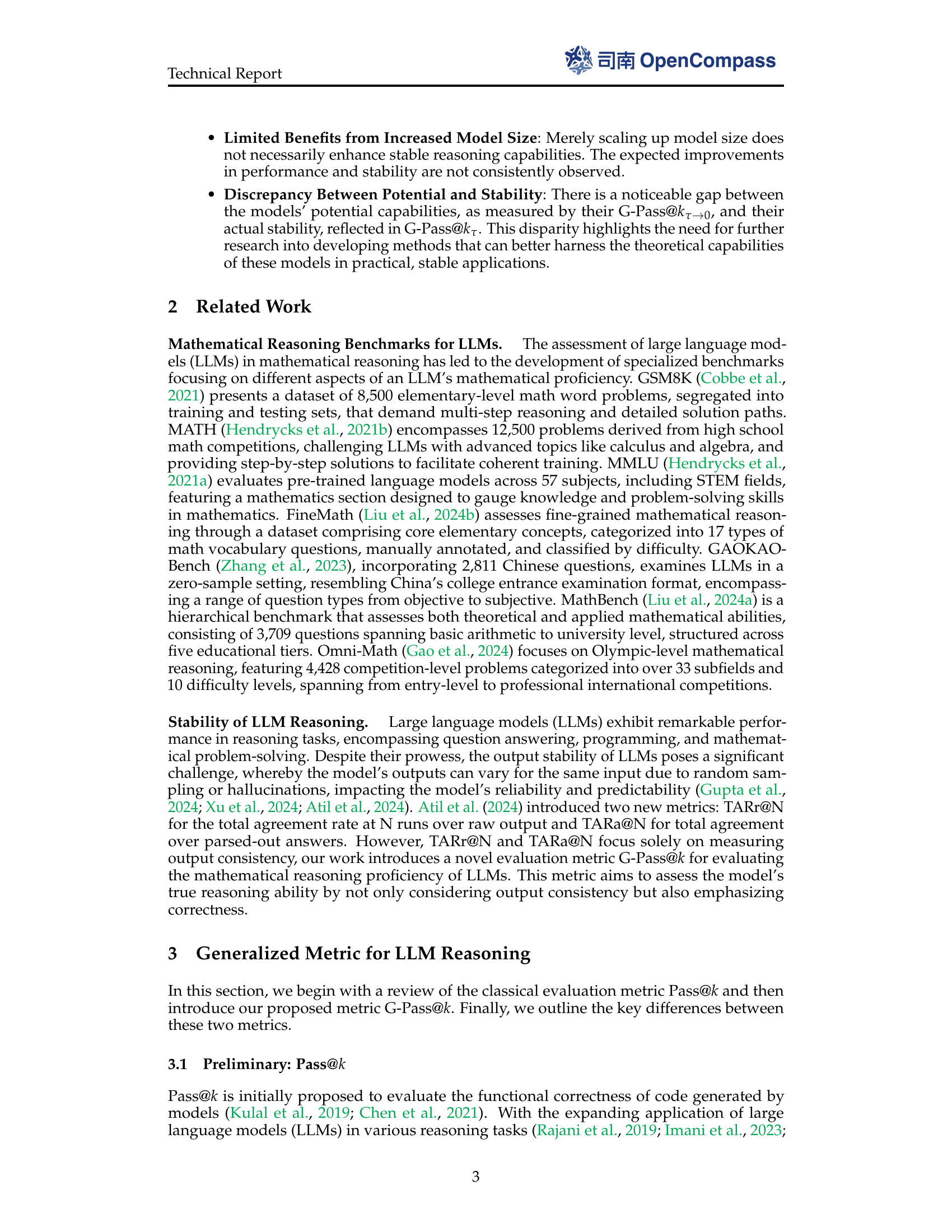

🔼 This figure compares Pass@k (the probability of getting at least one correct answer in k attempts) and the proposed G-Pass@k (generalized Pass@k that introduces a threshold and measures stability) given different c (number of correct answers). The plots are for different values of k, including 4, 8, 16, and 32. In the simulation, n (the number of trials) is set to 10 and c is varied.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of Pass@k𝑘kitalic_k and G-Pass@k𝑘kitalic_k. In our simulation configuration, we set n=10𝑛10n=10italic_n = 10, c={8,16,24,32}𝑐8162432c=\{8,16,24,32\}italic_c = { 8 , 16 , 24 , 32 }, and then calculate Pass@k𝑘kitalic_k and G-Pass@k𝑘kitalic_k.

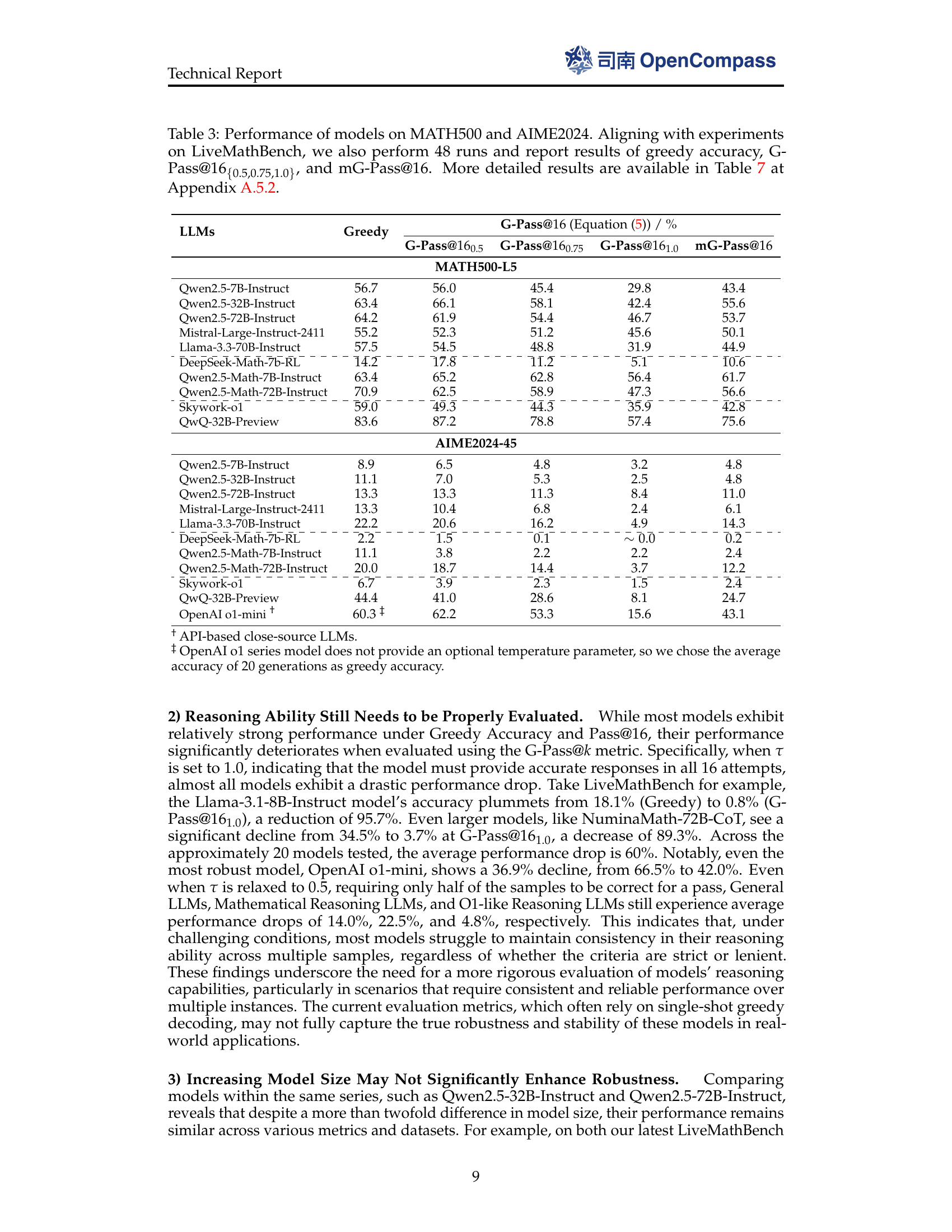

🔼 This figure shows how G-Pass@k changes with different k values (4, 8, and 16) at various thresholds (τ = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0) and different models (DeepSeek-Math-7b-RL, Qwen2.5-Math-72B-Instruct, and QwQ-32B-Preview). It aims to present the effectiveness of G-Pass@k for evaluating model performance and stability under various settings, where larger k can offer better differentiation for advanced models.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of G-Pass@k𝑘kitalic_k w.r.t. different values of k𝑘kitalic_k for DeepSeek-Math-7b-RL, Qwen2.5-Math-72B-Instruct, QwQ-32B-Preview.

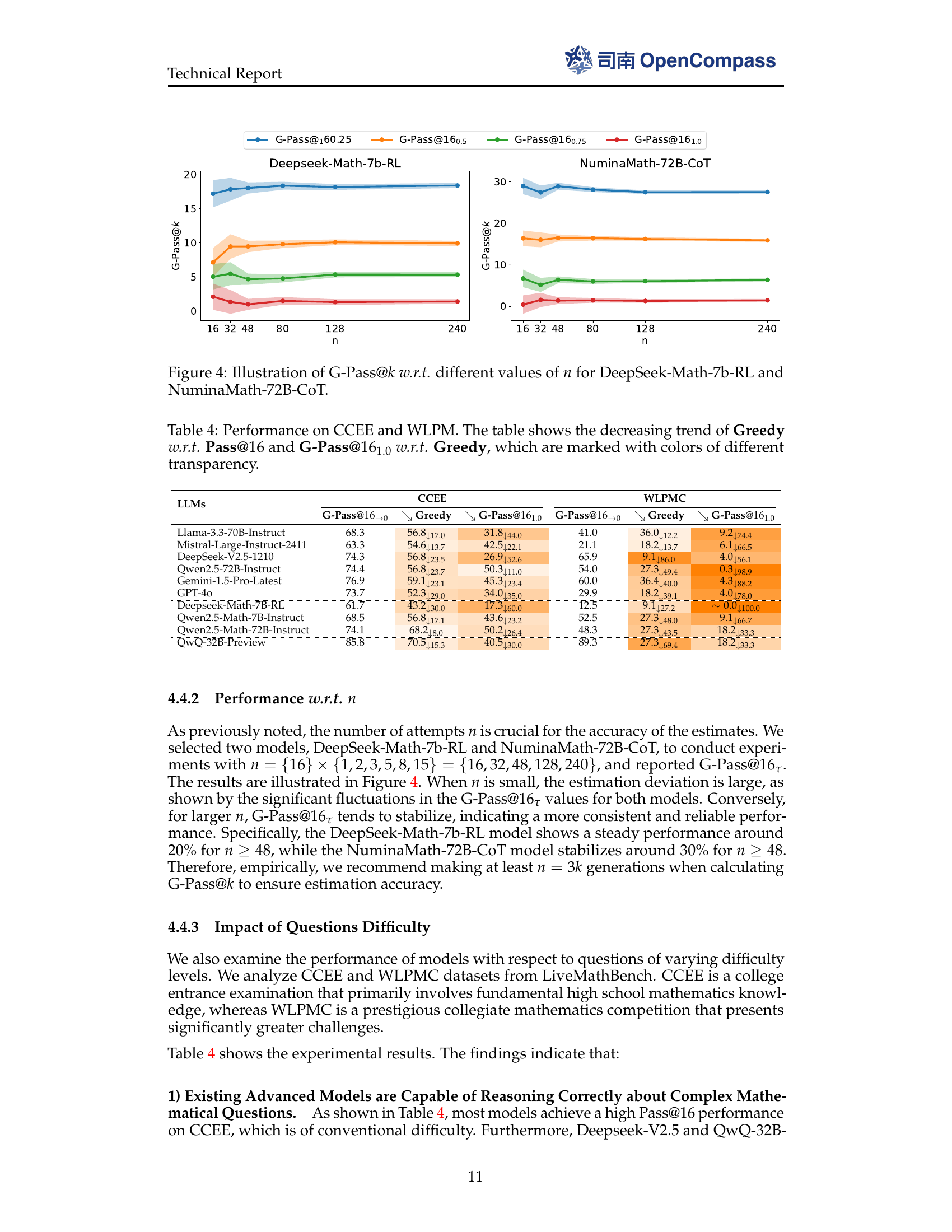

🔼 This figure shows the effect of the number of sampling attempts (n) on the stability metric G-Pass@k. The plot illustrates that with limited sample numbers, the stability metric G-Pass@k varies significantly, especially when the tolerance parameter \tau is small. With an increasing number of samples n, the estimation becomes more stable, with smaller fluctuations in G-Pass@k value. The figure includes two models DeepSeek-Math-7b-RL and NuminaMath-72B-CoT, showing that with a larger number of samples (n>48), the G-Pass@k values stabilize around 20% and 30%, respectively.

read the caption

Figure 4: Illustration of G-Pass@k𝑘kitalic_k w.r.t. different values of n𝑛nitalic_n for DeepSeek-Math-7b-RL and NuminaMath-72B-CoT.

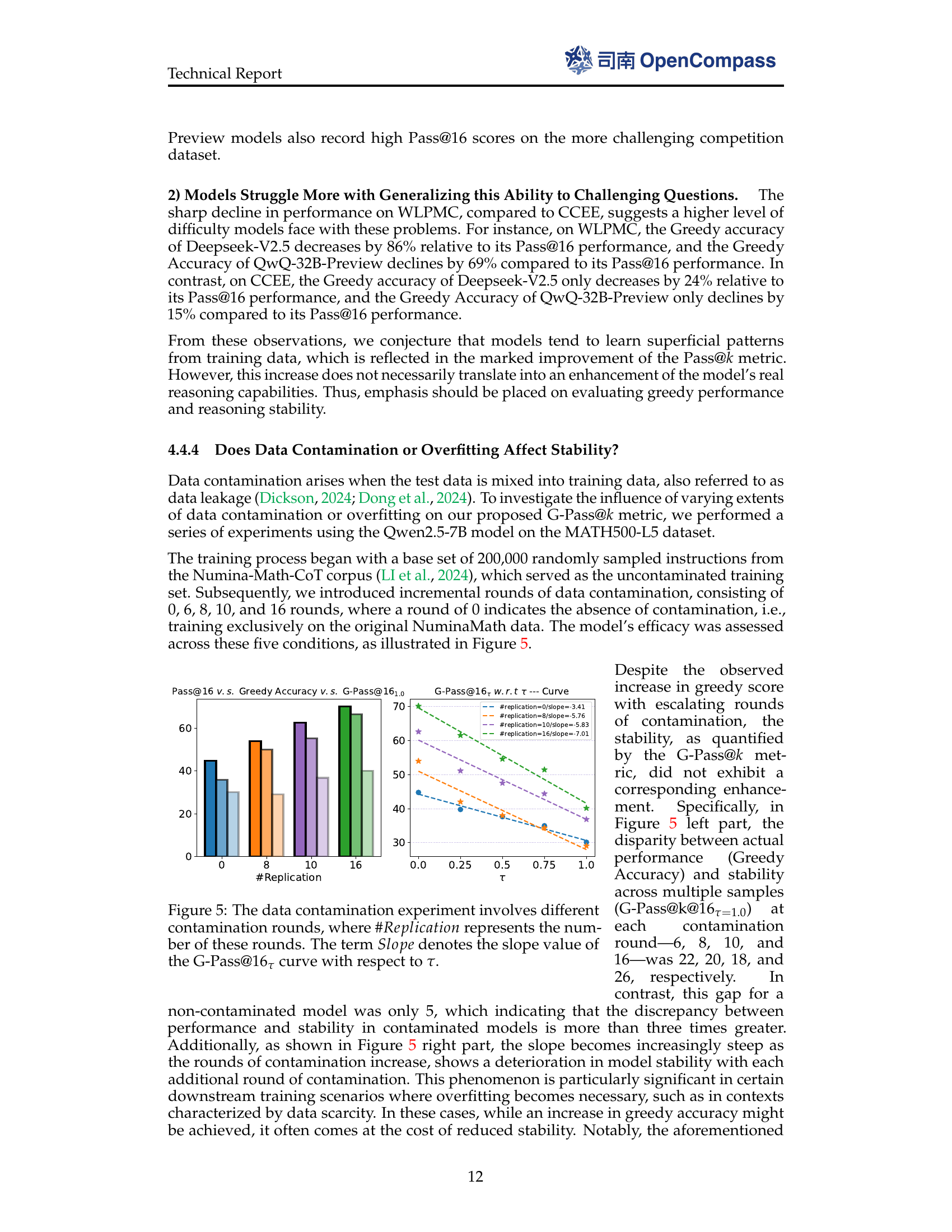

🔼 This figure shows the results of data contamination experiments on the Qwen2.5-7B model using the MATH500-L5 dataset. The x-axis (’#Replication’) represents the number of contamination rounds, which involves adding a portion of the MATH500-L5 data to the training set (Numina-Math-CoT). A value of 0 signifies no contamination (training only on the clean Numina-Math data). With increasing contamination, the model’s greedy performance generally improves, but its stability (G-Pass@16_{\tau=1.0}) suffers, widening the gap between potential and actual reliable performance. The right subplot focuses on the G-Pass@16 curve, showing that as contamination increases, the slope steepens (becomes more negative), further indicating a degradation in stability. The increasing slope magnitude (-3.41, -5.76, -5.83, -7.01) quantifies this.

read the caption

Figure 5: The data contamination experiment involves different contamination rounds, where #Replication#𝑅𝑒𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛\#Replication# italic_R italic_e italic_p italic_l italic_i italic_c italic_a italic_t italic_i italic_o italic_n represents the number of these rounds. The term Slope𝑆𝑙𝑜𝑝𝑒Slopeitalic_S italic_l italic_o italic_p italic_e denotes the slope value of the G-Pass@16τsubscript16𝜏16_{\tau}16 start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_τ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT curve with respect to τ𝜏\tauitalic_τ.

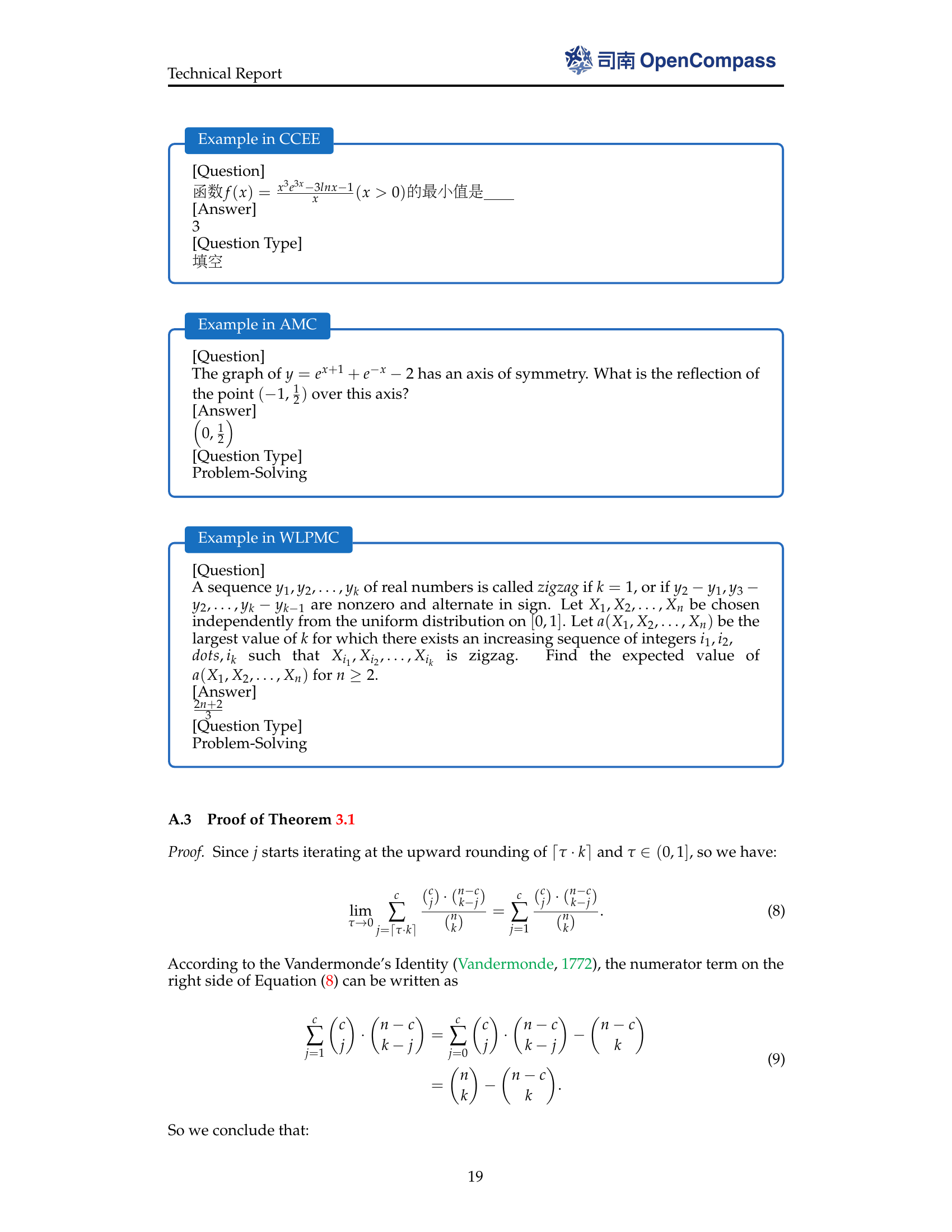

🔼 This figure presents the results of a simulation experiment designed to demonstrate that the proposed G-Pass@kτ metric provides an unbiased estimate, allowing for consistent comparisons across different values of n. The experiment assumes a model’s probability of providing a correct solution (p*) is set to 0.4. For various n values, multiple random Bernoulli samplings generate corresponding c values. These c values are then used to calculate G-Pass@kτ, subsequently determining the mean and variance to generate the plot. The consistency of the estimated values around the true probability demonstrates that G-Pass@kτ is an unbiased estimator.

read the caption

Figure 6: Illustration of estimation and the true value of G-Pass@kτsubscript𝑘𝜏k_{\tau}italic_k start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_τ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT.

More on tables

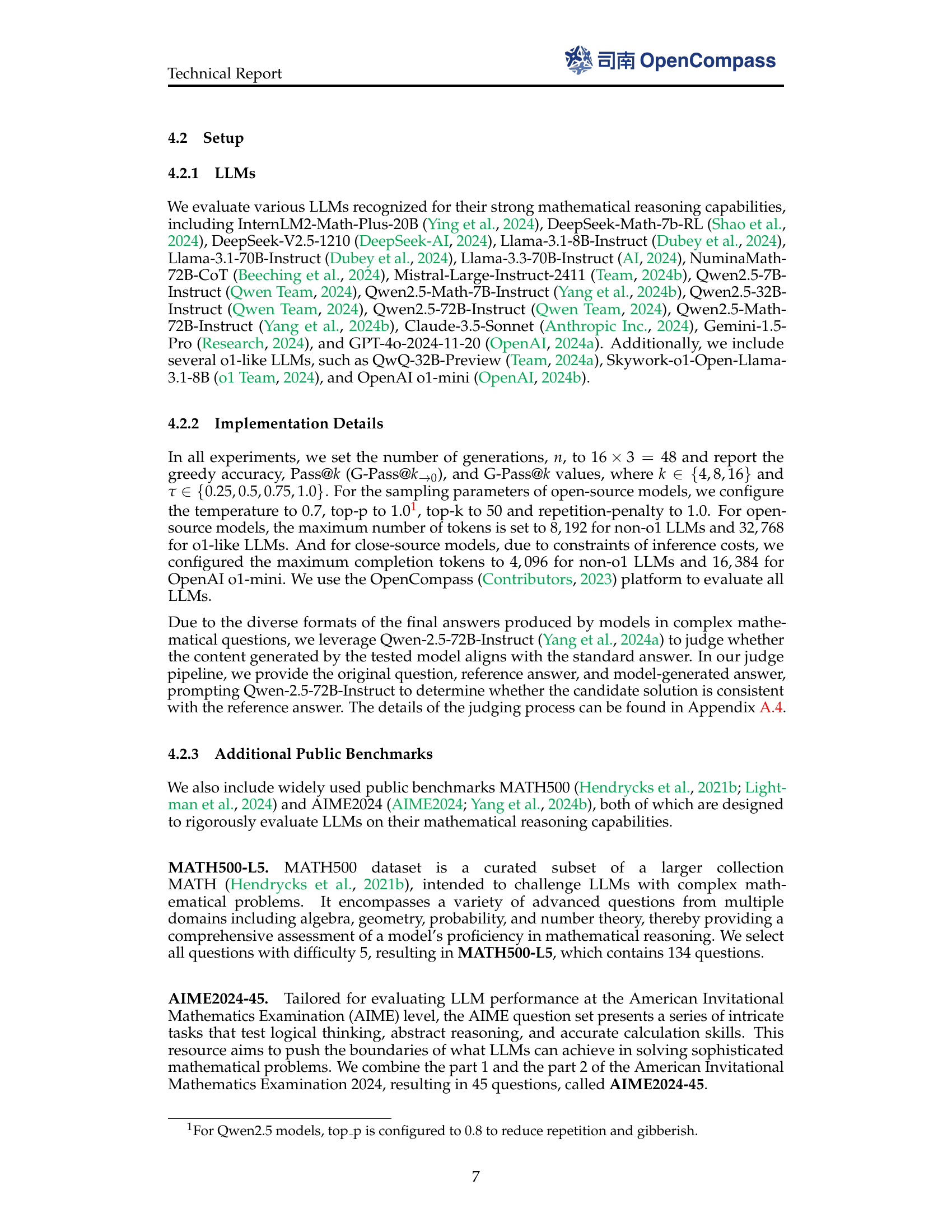

🔼 This table presents the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on the LiveMathBench dataset. It evaluates their mathematical reasoning capabilities using metrics that consider both accuracy and consistency across multiple runs. Specifically, it reports the greedy accuracy, G-Pass@16 (with thresholds of 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0), and mG-Pass@16. The table categorizes models into three groups: General LLMs, Mathematical Reasoning LLMs, and o1-like Reasoning LLMs. This allows for comparison of performance across different model types and sizes, providing insight into the impact of specialized training and architecture on mathematical reasoning abilities. It uses 48 samples per question.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance of models on LiveMathBench. We perform 48484848 runs and report results of greedy accuracy, and G-Pass@16{0.5,0.75,1.0}subscript160.50.751.016_{\{0.5,0.75,1.0\}}16 start_POSTSUBSCRIPT { 0.5 , 0.75 , 1.0 } end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and mG-Pass@16161616. A more detailed performance can be found in Table 6 at Section A.5.1.

| Models Need to Judge | Agreement | Disagreement | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deepseek-Math-7B-RL | 296 | 4 | 98.7 |

| Qwen2.5-32B-Instruct | 282 | 18 | 94.0 |

| Qwen2.5-Math-72B-Instruct | 287 | 13 | 95.7 |

| Mistral-Large-Instruct-2411 | 285 | 15 | 95.0 |

| QwQ-32B-Preview | 290 | 10 | 96.7 |

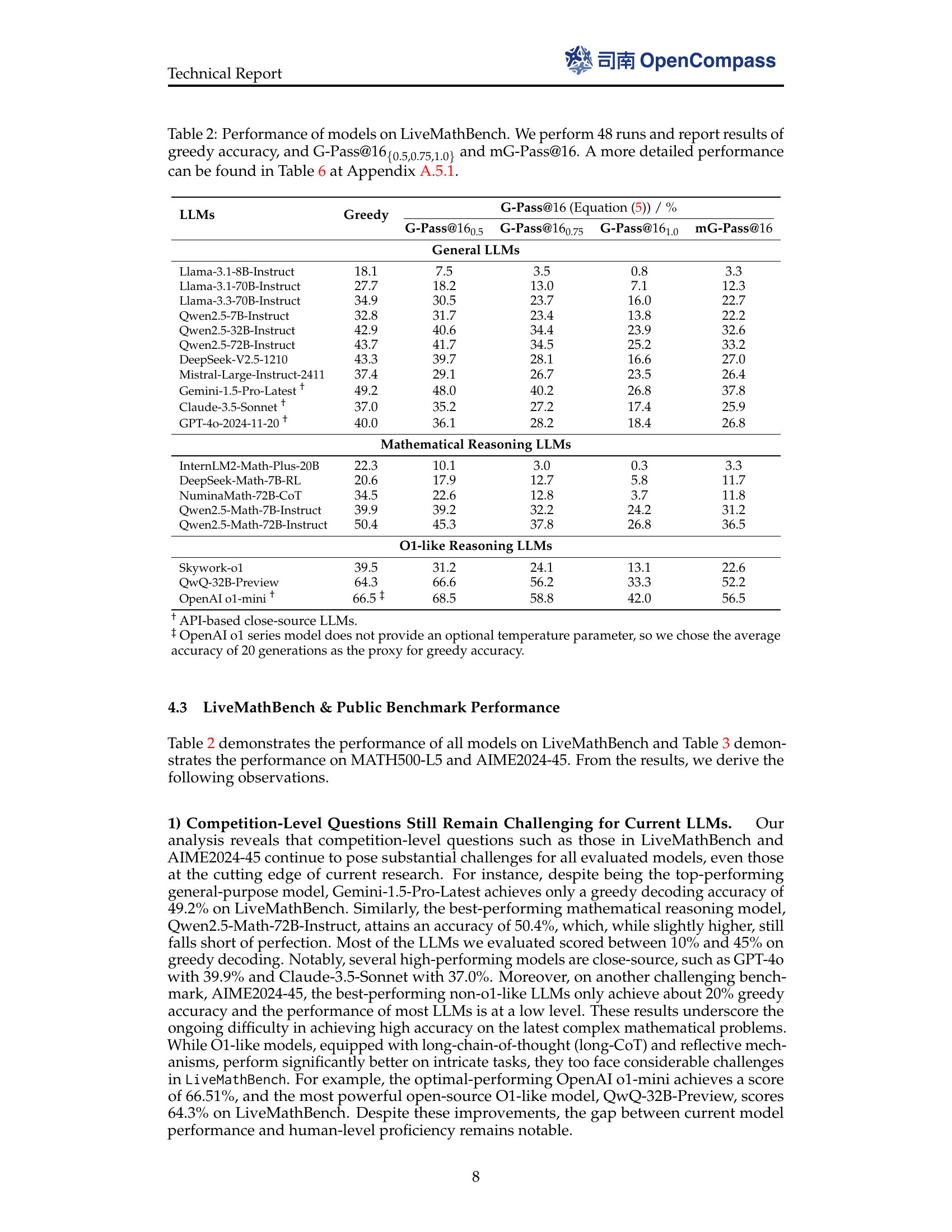

🔼 This table presents the evaluation results of various large language models (LLMs) on two mathematical reasoning benchmarks: MATH500-L5 and AIME2024-45. The evaluation metrics used are Greedy Accuracy, Pass@16 (equivalent to G-Pass@16 with τ→0), G-Pass@16 with varying thresholds (τ = 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0), and mG-Pass@16. These metrics assess different aspects of reasoning performance, including accuracy, stability, and potential. The table provides a comprehensive comparison of LLM capabilities in solving mathematical problems of varying complexity.

read the caption

Table 3: Performance of models on MATH500 and AIME2024. Aligning with experiments on LiveMathBench, we also perform 48484848 runs and report results of greedy accuracy, G-Pass@16{0.5,0.75,1.0}subscript160.50.751.016_{\{0.5,0.75,1.0\}}16 start_POSTSUBSCRIPT { 0.5 , 0.75 , 1.0 } end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, and mG-Pass@16161616. More detailed results are available in Table 7 at Section A.5.2.

Full paper#