↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

The widespread use of synthetic data in training large language models (LLMs) presents a significant challenge: model collapse, where iterative training on self-generated data leads to performance degradation. This paper investigates the impact of synthetic data on LLMs and explores methods to synthesize data without causing model collapse. The authors find a negative correlation between the proportion of synthetic data and model performance, attributing this to distributional shift and feature over-concentration in synthetic datasets.

To address this challenge, the authors propose token-level editing, a novel approach that modifies human-produced data at a token level using a pre-trained language model to create semi-synthetic data. This method is theoretically proven to prevent model collapse by keeping the test error bounded. Extensive experiments confirm the effectiveness of token-level editing across various training scenarios (pre-training from scratch, continual pre-training, and supervised fine-tuning), demonstrating improved model performance and data quality.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with synthetic data for language model training. It directly addresses the prevalent issue of model collapse, offering a novel theoretical framework and practical solution. This work is highly relevant given the increasing use of synthetic data and has the potential to significantly improve model performance and generalization capabilities. It opens exciting new avenues for research into data augmentation techniques and optimizing training data quality.

Visual Insights#

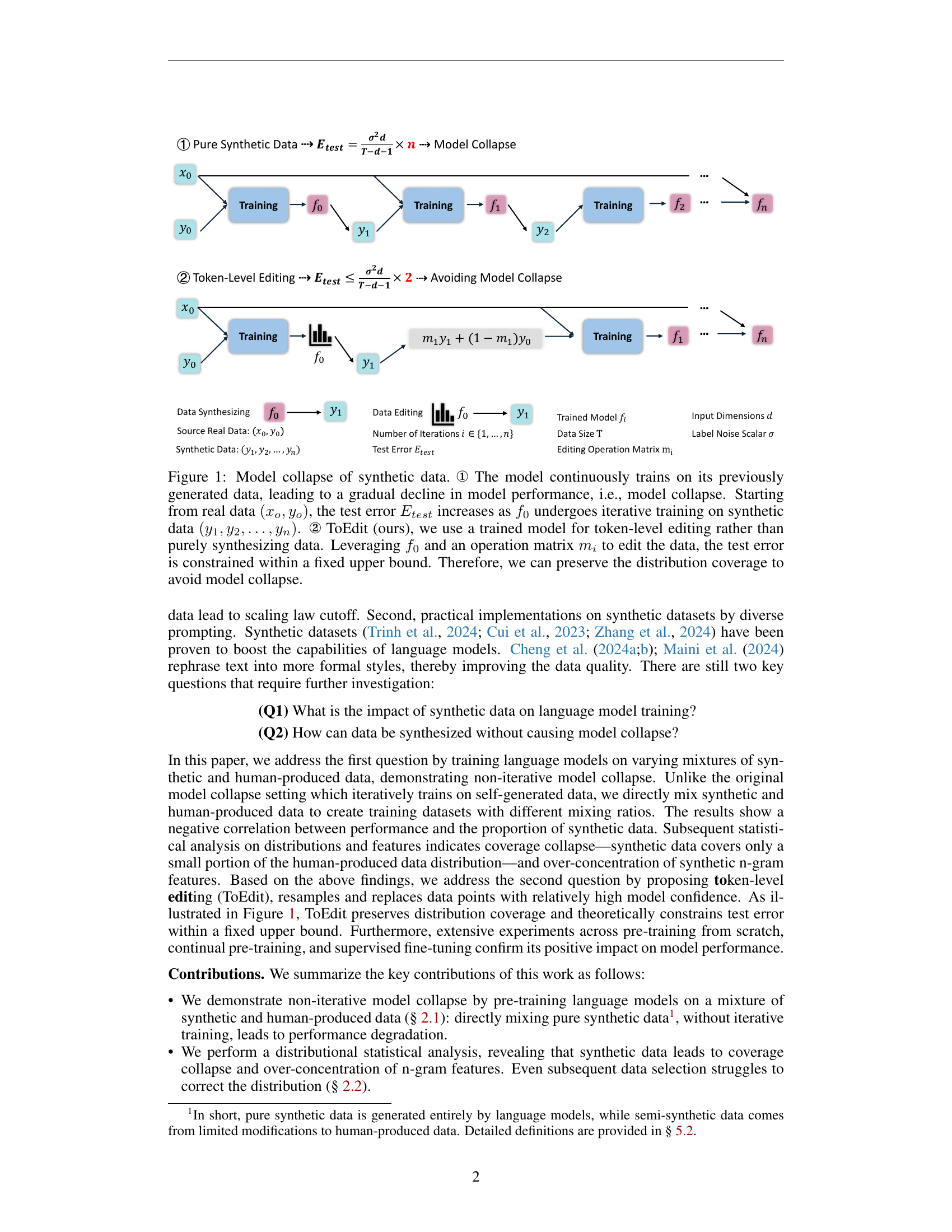

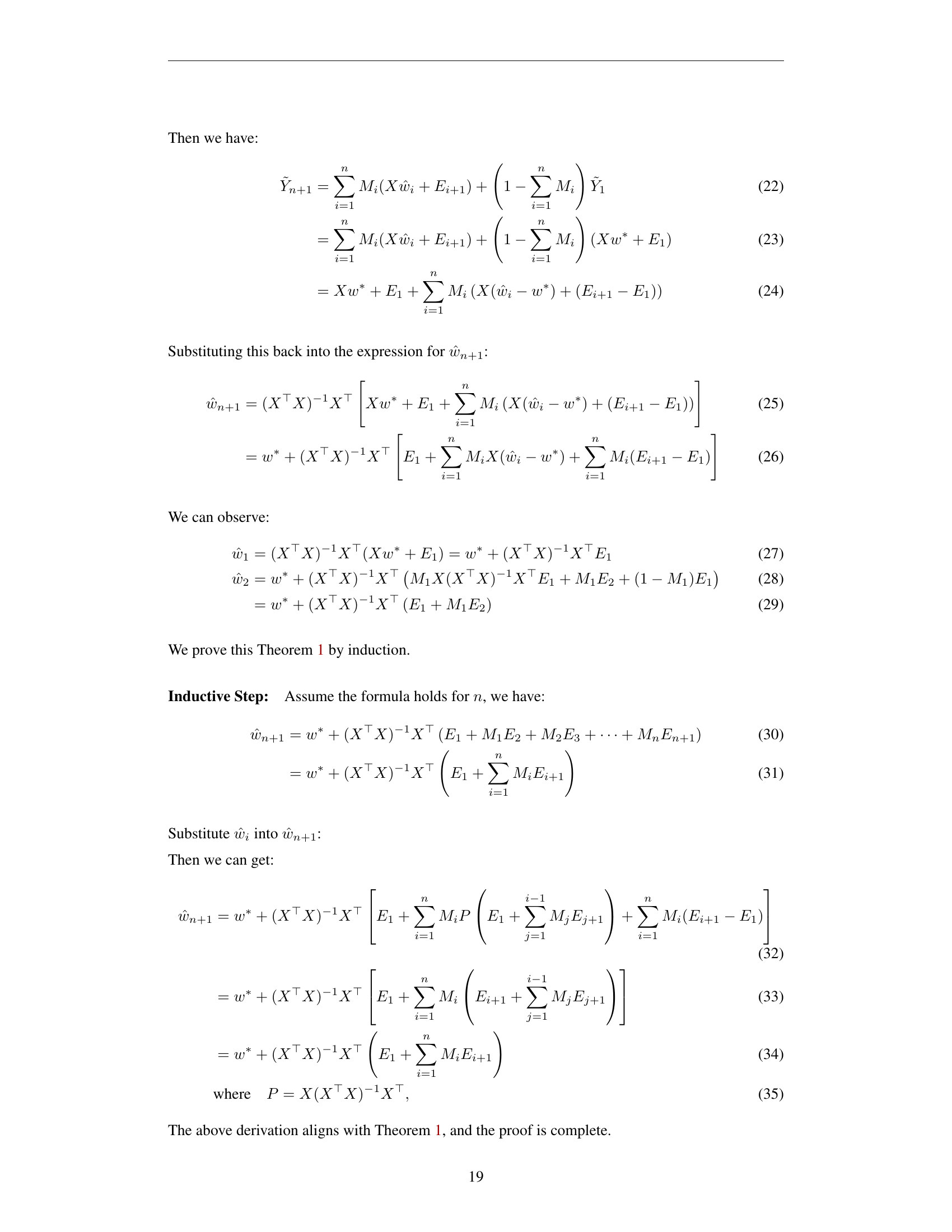

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of model collapse when using synthetic data for training and proposes a solution. In the first part, it shows how continuous training on self-generated data leads to an increase in the test error, which is the characteristic of model collapse. The second part introduces a method called ‘ToEdit’, where a pre-trained model is used for token-level editing of existing data instead of generating entirely new data. This method aims to constrain the test error within a bounded range, thereby preventing model collapse and maintaining distribution coverage.

read the caption

Figure 1: Model collapse of synthetic data. ① The model continuously trains on its previously generated data, leading to a gradual decline in model performance, i.e., model collapse. Starting from real data (xo,yo)subscript𝑥𝑜subscript𝑦𝑜(x_{o},y_{o})( italic_x start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_o end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , italic_y start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_o end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ), the test error Etestsubscript𝐸𝑡𝑒𝑠𝑡E_{test}italic_E start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_t italic_e italic_s italic_t end_POSTSUBSCRIPT increases as f0subscript𝑓0f_{0}italic_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 0 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT undergoes iterative training on synthetic data (y1,y2,…,yn)subscript𝑦1subscript𝑦2…subscript𝑦𝑛(y_{1},y_{2},\dots,y_{n})( italic_y start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , italic_y start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 2 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT , … , italic_y start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_n end_POSTSUBSCRIPT ). ② ToEdit (ours), we use a trained model for token-level editing rather than purely synthesizing data. Leveraging f0subscript𝑓0f_{0}italic_f start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 0 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and an operation matrix misubscript𝑚𝑖m_{i}italic_m start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_i end_POSTSUBSCRIPT to edit the data, the test error is constrained within a fixed upper bound. Therefore, we can preserve the distribution coverage to avoid model collapse.

| ArXiv | Books2 | Books3 | Math | Enron | EuroParl | FreeLaw | GitHub | PG-19 | HackerNews | NIH | Avg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human data | 22.26 | 25.39 | 22.87 | 10.84 | 23.50 | 30.73 | 12.04 | 4.15 | 16.88 | 32.54 | 23.53 | |

| 25% Synthetic Data | 21.86 | 26.32 | 23.87 | 11.05 | 24.85 | 35.02 | 12.84 | 4.35 | 17.99 | 33.80 | 23.76 | |

| 50% Synthetic Data | 22.50 | 28.01 | 25.75 | 10.84 | 26.56 | 41.99 | 14.02 | 4.67 | 19.70 | 36.12 | 24.61 | |

| 75% Synthetic Data | 24.35 | 31.19 | 28.98 | 11.81 | 30.30 | 56.32 | 16.03 | 5.30 | 22.75 | 40.44 | 26.19 | |

| Synthetic Data | 35.60 | 43.72 | 47.72 | 17.25 | 66.97 | 129.75 | 29.62 | 12.00 | 50.14 | 87.95 | 39.48 | |

| OpenSubts | OWT2 | Phil | Pile-CC | PubMed-A | PubMed-C | StackEx | Ubuntu | USPTO | Wikipedia | Youtube | Avg | |

| Human data | 28.08 | 25.77 | 33.56 | 26.78 | 18.97 | 15.49 | 10.81 | 20.86 | 19.32 | 24.31 | 21.54 | 21.37 |

| 25% Synthetic Data | 29.25 | 26.94 | 34.63 | 27.83 | 19.55 | 15.38 | 11.03 | 22.32 | 19.58 | 25.88 | 22.63 | 22.31 |

| 50% Synthetic Data | 31.00 | 28.76 | 37.48 | 29.36 | 20.51 | 15.89 | 11.54 | 23.53 | 20.51 | 27.57 | 24.91 | 23.90 |

| 75% Synthetic Data | 34.18 | 32.04 | 42.39 | 32.17 | 22.33 | 16.92 | 12.55 | 26.54 | 22.21 | 30.68 | 28.98 | 27.03 |

| Synthetic Data | 57.83 | 53.94 | 78.18 | 54.69 | 34.82 | 23.87 | 20.47 | 51.78 | 37.24 | 46.12 | 65.49 | 49.30 |

🔼 This table presents the perplexity (PPL) scores achieved by a GPT-2 Small language model (124M parameters) after being pre-trained on various mixtures of human-generated and synthetic text data. Different rows represent different proportions of synthetic data in the training dataset (ranging from 0% to 100%). Each column shows the PPL on a specific downstream task evaluation dataset. Higher PPL indicates lower performance. The results demonstrate a clear trend: as the proportion of synthetic data increases, the overall PPL increases across all downstream tasks, confirming the negative correlation between the amount of synthetic data and model performance shown graphically in Figure 2 of the paper.

read the caption

Table 1: PPL evaluation results for GPT-2 Small (124M) pre-trained on data mixture. The PPL increases as the proportion of synthetic data grows, providing further confirmation of Figure 2.

In-depth insights#

Synthetic Data Risks#

Synthetic data, while offering advantages in data augmentation and privacy preservation, presents inherent risks. Model collapse, where models overfit to synthetic data and lose generalization ability on real-world data, is a critical concern. This often stems from distributional shifts between synthetic and real data, leading to performance degradation on downstream tasks. Furthermore, the quality of synthetic data is paramount; poorly generated data can introduce biases and inaccuracies, impacting model fairness and reliability. Addressing these risks requires careful consideration of data generation methods, rigorous evaluation metrics focusing on real-world performance, and potentially the incorporation of techniques to detect and mitigate distributional shifts. Continuous monitoring and validation are also crucial to ensure synthetic data’s ongoing suitability for training and avoid unintended consequences.

Token-Level Editing#

The proposed method of token-level editing offers a novel approach to synthesizing high-quality training data for language models by directly modifying existing human-generated text instead of generating entirely new synthetic data. This approach directly addresses the issues of model collapse and data quality degradation often associated with purely synthetic datasets. The core concept involves using a pre-trained language model to identify tokens with high conditional probabilities, implying these are easily learned by the model. These tokens are then selectively replaced with tokens sampled from a prior distribution. This process theoretically prevents model collapse by constraining the test error within a bounded range and prevents overfitting to specific features, enhancing generalization capabilities. The efficacy of this method is supported by theoretical analysis and extensive experiments across various model training stages, highlighting improved model performance on downstream tasks compared to training with purely synthetic or human-only data. Token-level editing represents a significant advancement by offering a semi-supervised approach that leverages the strengths of both human-authored and model-generated data without succumbing to the limitations of either approach. The practical implications are significant as it presents a viable path towards harnessing synthetic data for enhancing large language models without incurring the risks of model collapse.

Model Collapse Proof#

A rigorous ‘Model Collapse Proof’ within a research paper would involve a formal mathematical demonstration that iterative training on synthetic data inevitably leads to performance degradation. This proof would likely leverage theoretical frameworks such as linear regression or information theory. Key elements would include defining a precise metric for ‘model collapse’ (e.g., divergence between synthetic and real data distributions), establishing an upper bound on model performance as a function of iterations, and demonstrating that this bound is reached under specified conditions. A robust proof might analyze distributional shifts within synthetic data, and show how these shifts systematically hinder the model’s ability to generalize to unseen, real-world data. Crucially, the proof should address the factors that lead to an accumulation of errors over iterations, such as the over-representation of certain features or the loss of long-tail phenomena. The demonstration should be supported by experiments showing that the proposed theoretical limits are indeed observed empirically. The overall goal would be to formally prove, rather than merely observe, the existence and mechanisms of model collapse.

Pre-training Analysis#

A pre-training analysis of large language models (LLMs) trained on synthetic data would involve a multifaceted investigation. It would start by comparing the performance of models trained on varying ratios of synthetic and real data, quantifying the impact of synthetic data on downstream tasks. Key metrics like perplexity and accuracy on benchmark datasets would be crucial. The analysis would delve into the underlying reasons for performance differences, potentially exploring distributional shifts between real and synthetic data. Feature-level analysis comparing n-gram frequencies or embedding space similarity could reveal whether synthetic data lacks the diversity or nuances of real-world data, leading to overfitting or model collapse. Statistical measures would help quantify these differences and confirm potential biases. Furthermore, the study could investigate if the quality of synthetic data generation methods affects LLM performance, and whether techniques like token editing improve model outcomes. Finally, the analysis should propose ways to create more effective and less harmful synthetic data for LLM pre-training, possibly by incorporating techniques to mitigate the identified shortcomings.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize refining data synthesis methods to mitigate coverage collapse and over-concentration of n-grams. This could involve exploring alternative generative models or incorporating techniques like data augmentation to enrich synthetic data distributions. Investigating advanced data selection methods beyond importance sampling is crucial to effectively combine synthetic and human-produced data. Theoretical analyses should move beyond linear regression models to encompass more complex models that better capture the nuances of language generation. Furthermore, the impact of synthetic data quality on downstream tasks like continual pre-training and fine-tuning warrants extensive investigation. Finally, the development of robust metrics to evaluate the quality and utility of synthetic data, going beyond simple perplexity scores, is a critical area needing further exploration. This will allow for a more precise assessment of the success of various synthetic data generation techniques.

More visual insights#

More on figures

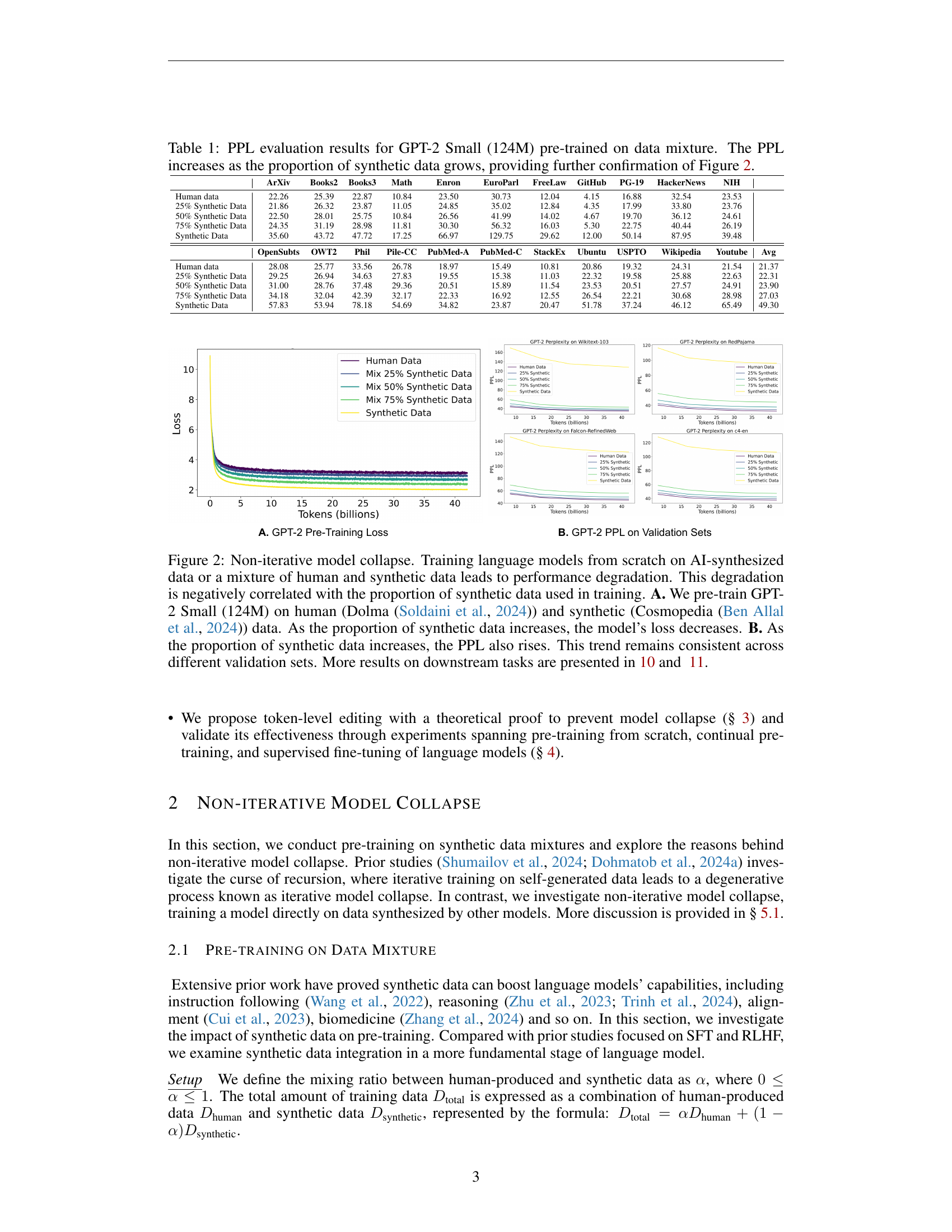

🔼 This figure demonstrates the negative impact of using synthetic data for training language models. In the experiment, GPT-2 Small (124M) was pre-trained using varying proportions of human-generated text (Dolma dataset) and AI-synthesized text (Cosmopedia dataset). Part A shows that, counter-intuitively, the model’s training loss decreases as the percentage of synthetic data increases. This is because the model is overfitting to the characteristics of the synthetic data. However, as shown in Part B, increased reliance on synthetic data results in significantly higher perplexity scores (PPL) across multiple validation sets, indicating a decline in the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. This demonstrates a negative correlation between the amount of synthetic data and overall model performance.

read the caption

Figure 2: Non-iterative model collapse. Training language models from scratch on AI-synthesized data or a mixture of human and synthetic data leads to performance degradation. This degradation is negatively correlated with the proportion of synthetic data used in training. A. We pre-train GPT-2 Small (124M) on human (Dolma (Soldaini et al., 2024)) and synthetic (Cosmopedia (Ben Allal et al., 2024)) data. As the proportion of synthetic data increases, the model’s loss decreases. B. As the proportion of synthetic data increases, the PPL also rises. This trend remains consistent across different validation sets. More results on downstream tasks are presented in 10 and 11.

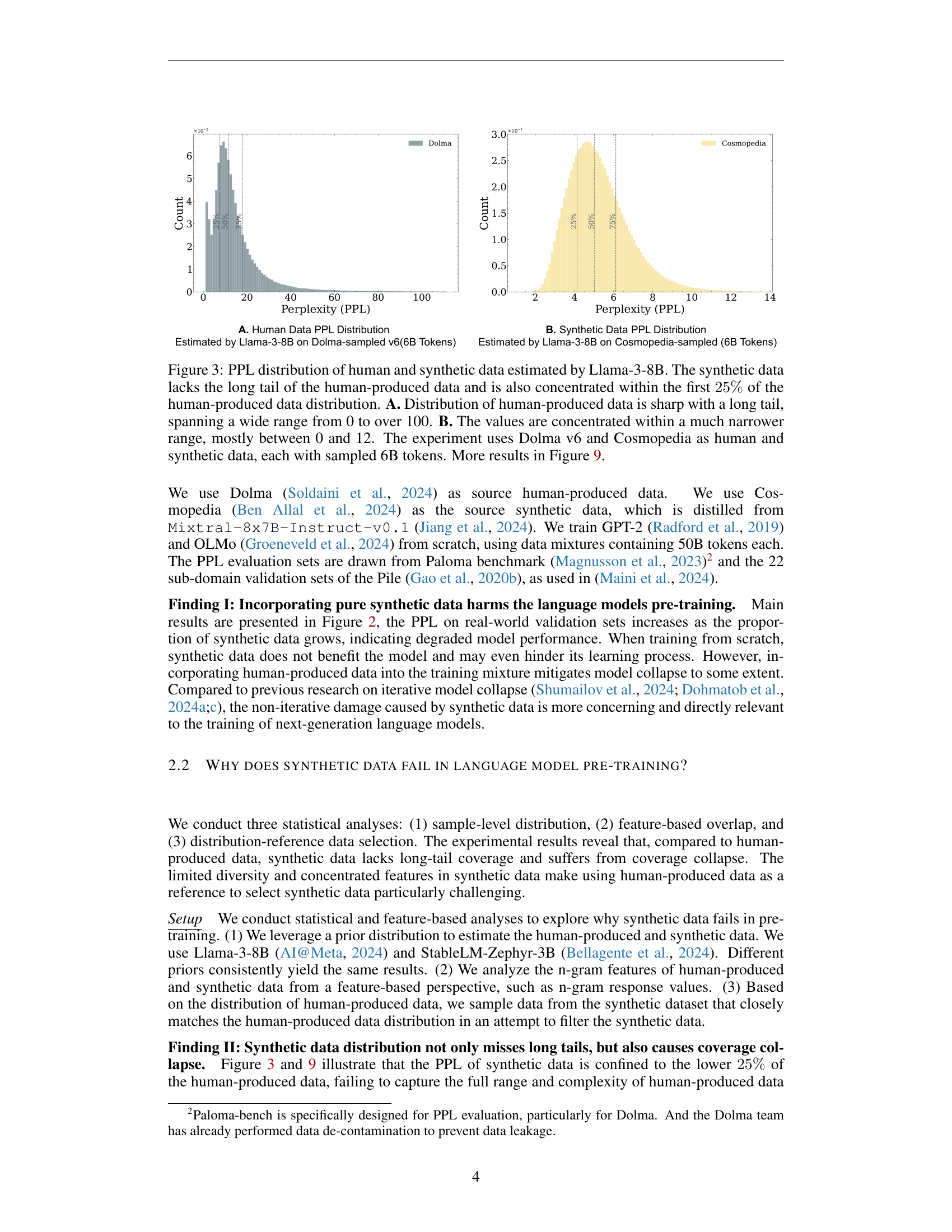

🔼 This figure compares the perplexity (PPL) distributions of human-generated text (Dolma v6) and synthetic text (Cosmopedia), both sampled at 6 billion tokens. The Llama-3-8B language model was used to estimate the PPL for each dataset. The human-generated text exhibits a sharp distribution with a long tail, ranging from a PPL of 0 to over 100. In contrast, the synthetic data shows a much narrower, concentrated distribution, with most PPL values falling between 0 and 12. This highlights a key difference: the synthetic data lacks the diversity and long tail present in the human-generated text, suggesting a potential limitation of relying solely on synthetic data for training language models.

read the caption

Figure 3: PPL distribution of human and synthetic data estimated by Llama-3-8B. The synthetic data lacks the long tail of the human-produced data and is also concentrated within the first 25%percent2525\%25 % of the human-produced data distribution. A. Distribution of human-produced data is sharp with a long tail, spanning a wide range from 0 to over 100. B. The values are concentrated within a much narrower range, mostly between 0 and 12. The experiment uses Dolma v6 and Cosmopedia as human and synthetic data, each with sampled 6B tokens. More results in Figure 9.

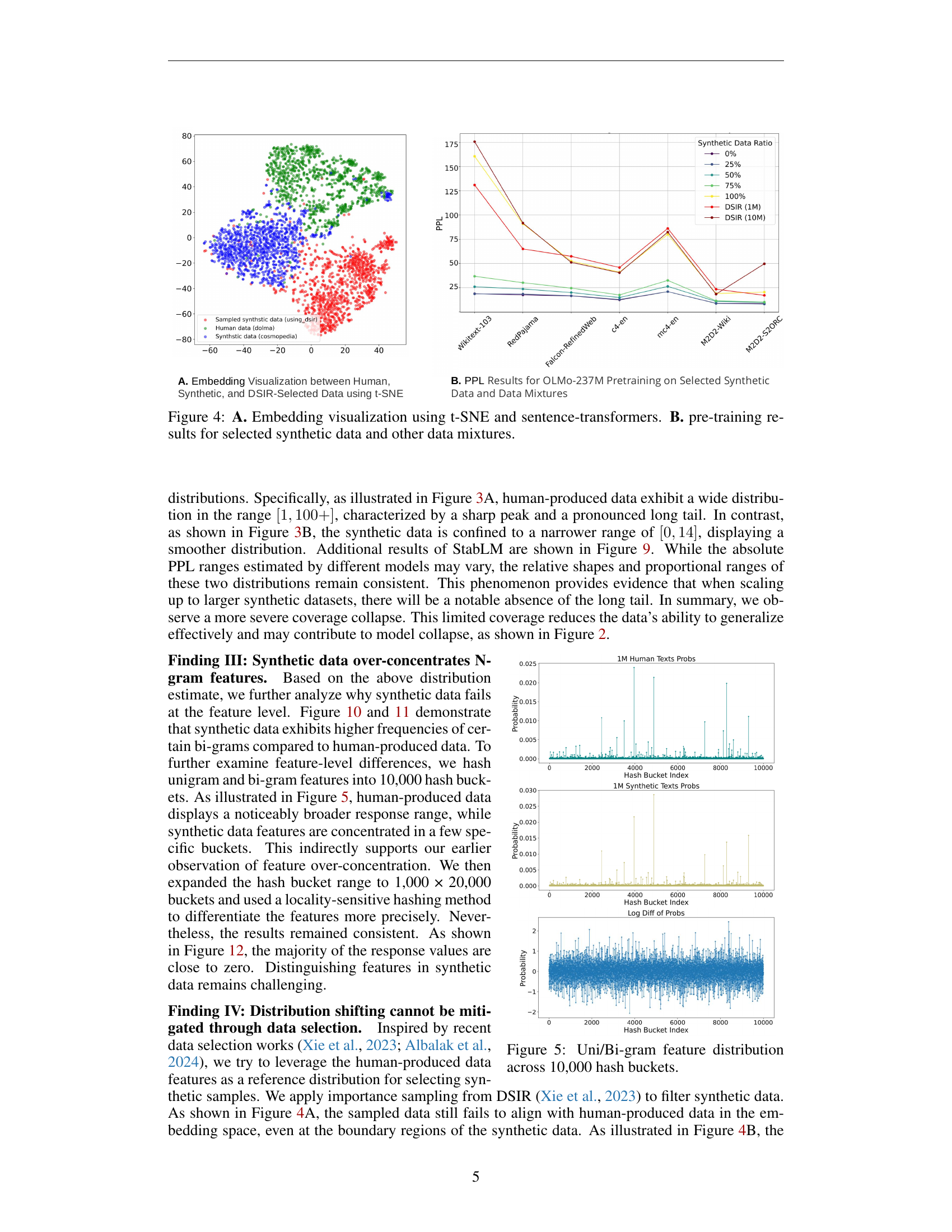

🔼 Figure 4 visualizes the results of experiments on synthetic data. Panel A shows a t-SNE embedding plot comparing the feature representations of human-produced data (Dolma), purely synthetic data (Cosmopedia), and synthetic data selected using the DSIR method. This helps to understand the distributional differences between the datasets. Panel B presents pre-training results using OLMo-237M. The perplexity (PPL) values are shown for various mixtures of human and synthetic data, along with results using only selected synthetic data. This showcases the impact of different data compositions on model performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: A. Embedding visualization using t-SNE and sentence-transformers. B. pre-training results for selected synthetic data and other data mixtures.

🔼 This figure visualizes the distribution of unigrams and bigrams from both human-produced and synthetic text data. The features are hashed into 10,000 buckets, allowing for a comparison of feature frequency and distribution between the two datasets. The figure aims to illustrate the differences in the feature landscape of the two data types, specifically highlighting the over-concentration of features in the synthetic data compared to the broader distribution in human-produced data, which suggests a lack of diversity and potential overfitting issues.

read the caption

Figure 5: Uni/Bi-gram feature distribution across 10,000 hash buckets.

🔼 The figure displays the probability distribution of tokens within the Dolma-sampled V6 dataset, as estimated by the Qwen-0.5B-Instruct model. The distribution exhibits a U-shape, indicating a concentration of tokens with both very high and very low probabilities, and a relative scarcity of tokens with intermediate probabilities. This U-shaped distribution is key to the paper’s proposed token-level editing method, which uses probability as a guide to modify tokens to improve the quality of synthetic data.

read the caption

Figure 6: U-shape token probability distribution of Dolma-sampled V6 estimated by Qwen-0.5B-Instruct (qwe, 2024).

🔼 This figure displays the results of pre-training the OLMo-237M language model using various mixtures of human-generated text data from the Dolma dataset and synthetic text data from the Cosmopedia dataset. The x-axis represents the amount of training data (in billions of tokens), and the y-axis shows the pre-training loss. Multiple lines are presented, each corresponding to a different proportion of synthetic data in the training mixture (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%). The figure visually demonstrates the impact of synthetic data on the model’s pre-training performance, revealing a trend of increasing loss as the proportion of synthetic data increases. This illustrates the concept of model collapse, where reliance on synthetic data negatively affects model performance.

read the caption

Figure 7: OLMo-237M pretraining with mixed human and synthetic data proportions. We pretrain the OLMo-237M model using a mixture of human data (Dolma (Soldaini et al., 2024)) and synthetic data (Cosmopedia (Ben Allal et al., 2024)).

🔼 This figure displays the perplexity (PPL) scores achieved by GPT-2 models trained from scratch on datasets with varying proportions of synthetic data. The PPL, a metric evaluating how well a language model predicts a given dataset (lower is better), is shown across several validation sets. The graph visualizes the impact of synthetic data on the model’s performance, illustrating how increasing the proportion of synthetic data affects the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data.

read the caption

Figure 8: GPT-2 perplexity (PPL) on validation sets, trained from scratch.

🔼 Figure 9 presents the probability distribution of perplexity (PPL) scores for both human-generated and synthetic text data. The PPL, calculated using the StableLM-Zephyr-3B language model, measures how well a model predicts the next word in a sequence, with lower scores indicating better predictability. The distribution of PPL scores for human text shows a long tail, meaning the model sometimes struggles to predict words accurately, reflecting the diversity and complexity of human language. In contrast, the distribution for synthetic data is concentrated within a much narrower range and lacks a long tail. This indicates that the synthetic text is less diverse and more predictable than human text, thus highlighting a key characteristic of synthetic data: it often fails to capture the full complexity and nuances present in real-world human language.

read the caption

Figure 9: PPL distribution of human and synthetic data estimated by StabLM-Zephyr-3B. This indicates that different prior distributions yielded the same result, which is consistent with Figure 3. The synthetic data lacks a long tail and is concentrated within a narrow portion of the distribution.

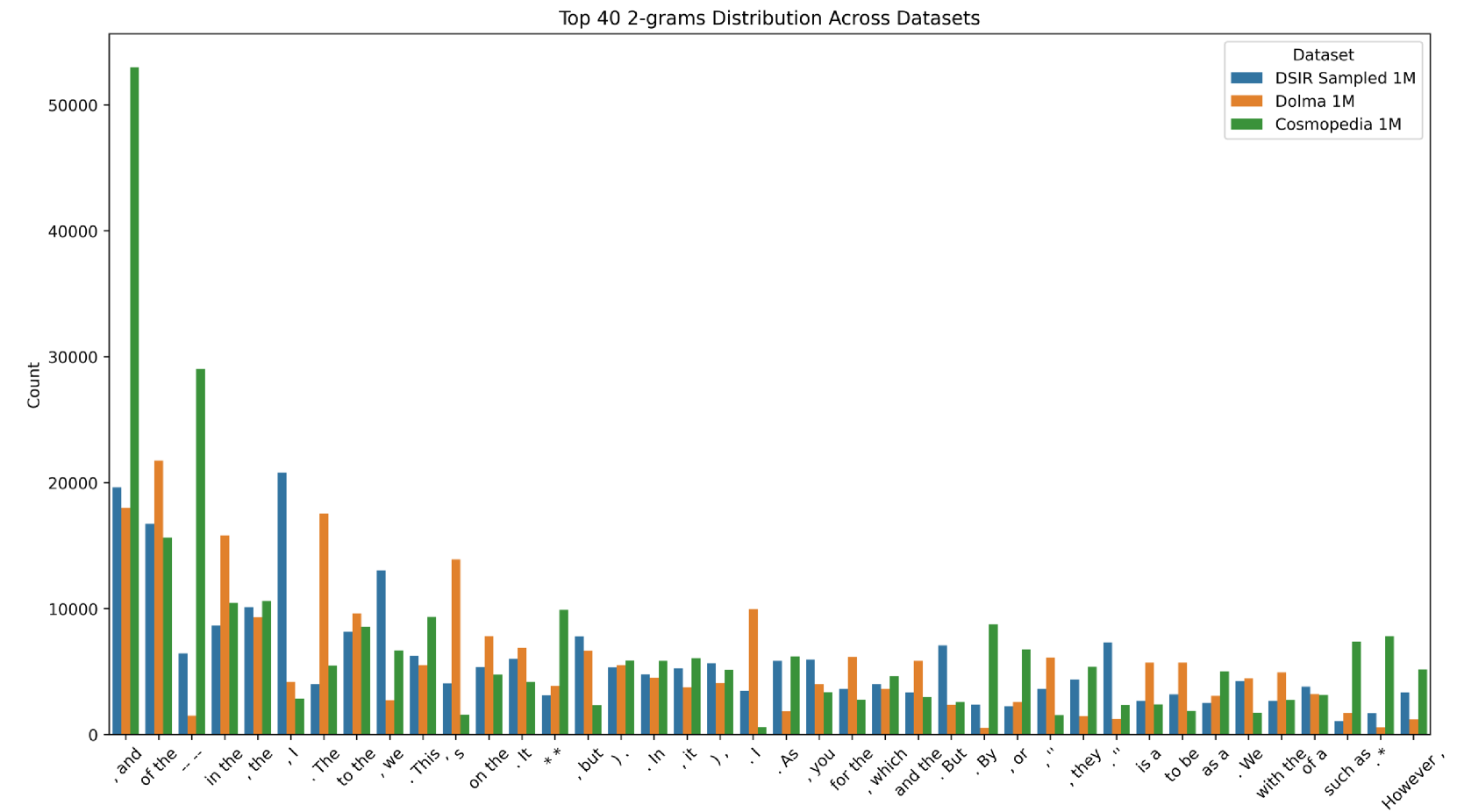

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the top 40 most frequent bi-grams (pairs of consecutive words) found in three different datasets: Dolma (human-written text), Cosmopedia (synthetic text generated by a language model), and a subset of Cosmopedia filtered using the DSIR (Data Selection via Importance Resampling) method. The bar chart visually represents the frequency of each bi-gram in each dataset, allowing for a direct comparison of the feature distributions across the different data sources. This comparison helps to highlight the differences in the linguistic features and patterns present in human-written text versus synthetic text, both before and after filtering by DSIR.

read the caption

Figure 10: The top 40 bi-grams from separately sampled 1M subsets of Dolma, Cosmopedia, and DSIR-selected datasets.

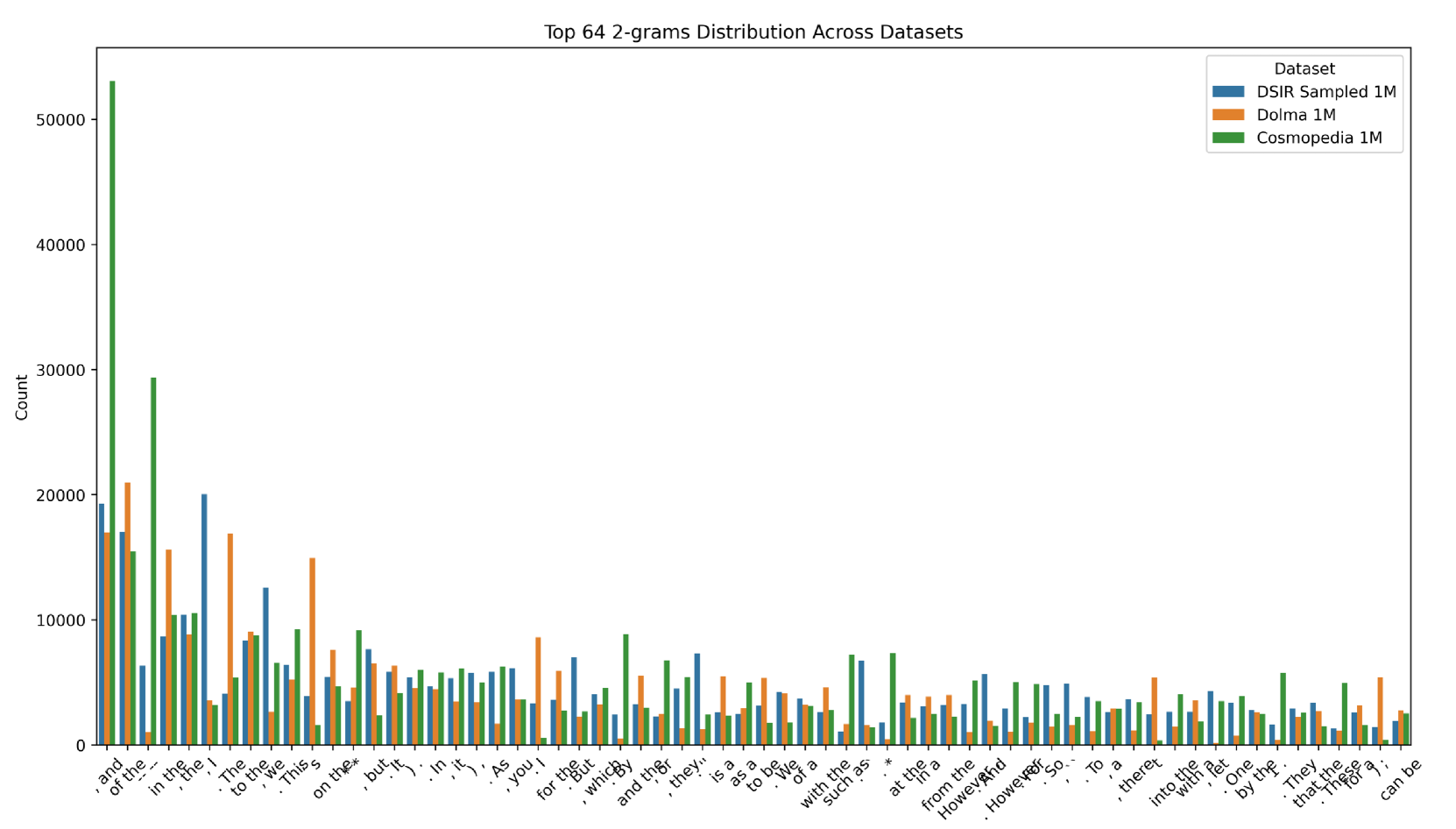

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the top 64 most frequent bi-grams (two-word combinations) found in three different datasets: Dolma (human-written text), Cosmopedia (synthetic text generated by a large language model), and a subset of Cosmopedia filtered using the DSIR (Data Selection via Importance Resampling) method. The bar chart visually represents the frequency of each bi-gram in the respective datasets, allowing for a direct comparison of the feature distributions between human-generated text and synthetic text, both before and after applying a data selection technique. This visualization helps illustrate the differences in the n-gram features between human-authored and synthetic text, particularly highlighting the over-concentration of certain bi-grams in the synthetic datasets.

read the caption

Figure 11: The top 64 bi-grams from separately sampled 1M subsets of Dolma, Cosmopedia, and DSIR-selected datasets.

🔼 Figure 12 presents a heatmap visualization of the distribution of locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) feature values obtained from density sampling of synthetic data. The heatmap shows the frequency of different feature values across a range of hash functions. A significant observation is that the feature values are heavily concentrated within a narrow range, showing a lack of diversity. This concentration, visualized as a sharp peak in the distribution, indicates a phenomenon called ‘feature collapse’. Feature collapse in synthetic data means that the generated data lacks the diversity and richness of features present in real, human-generated data. This limited feature coverage directly impacts the performance of language models trained on this type of data, limiting their ability to generalize well to unseen real-world examples.

read the caption

Figure 12: Density sampling response values. This result further confirms the issue of feature collapse in synthetic data.

More on tables

| Models | MQP | ChemProt | PubMedQA | RCT | USMLE | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLMo-1B | 52.59 | 17.2 | 51.40 | 32.70 | 28.90 | 36.63 |

| CPT | 52.29 | 21.00 | 58.50 | 34.90 | 27.49 | 38.83 |

| Δ ToEdit | 54.59 | 22.40 | 65.00 | 34.50 | 27.96 | 40.89 |

| LLama-3-8B | 66.80 | 28.59 | 60.8 | 73.85 | 40.61 | 54.13 |

| CPT | 72.29 | 29.4 | 69.1 | 72.65 | 36.76 | 56.04 |

| Δ ToEdit | 76.39 | 30.2 | 65.3 | 73.30 | 37.23 | 56.48 |

| Models | HeadLine | FPB | FiQA-SA | ConvFinQA | NER | Average |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| OLMo-1B | 69.00 | 47.03 | 48.05 | 4.83 | 62.19 | 46.22 |

| CPT | 70.31 | 49.78 | 40.36 | 18.72 | 60.44 | 47.92 |

| Δ ToEdit | 71.77 | 51.39 | 46.06 | 18.85 | 62.97 | 50.21 |

| LLama-3-8B | 81.28 | 63.58 | 81.60 | 52.88 | 72.53 | 70.37 |

| CPT | 85.68 | 54.22 | 81.88 | 67.78 | 67.43 | 71.40 |

| Δ ToEdit | 83.83 | 61.61 | 80.82 | 67.31 | 67.62 | 72.24 |

| Models | ARC-c | GPQA | GSM8K | MATH | MMLU | Average |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| OLMo-1B | 28.67 | 24.23 | 1.67 | 0.00 | 26.56 | 16.23 |

| CPT | 28.41 | 24.03 | 1.52 | 0.10 | 27.23 | 16.26 |

| Δ ToEdit | 28.92 | 28.12 | 2.20 | 0.10 | 23.63 | 16.59 |

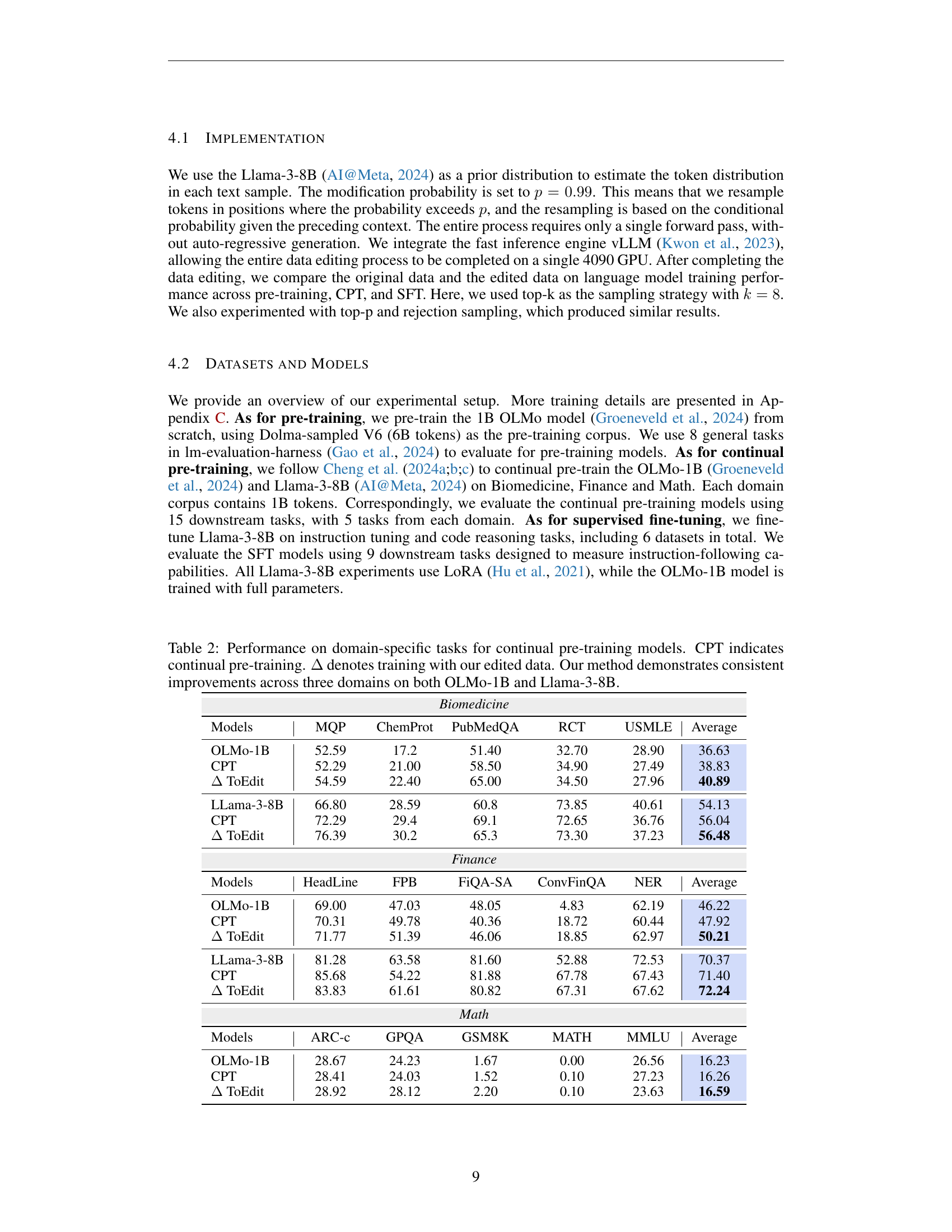

🔼 This table presents the results of continual pre-training experiments on language models, comparing performance across three domains (Biomedicine, Finance, Math). The models used are OLMo-1B and Llama-3-8B. For each model, the performance is measured with and without using the authors’ token-level editing technique (ToEdit) on the training data. The standard continual pre-training approach (CPT) is compared to the CPT approach that incorporates ToEdit. The table shows the average performance improvement across multiple tasks within each domain, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed data editing method in enhancing the models’ performance in domain-specific tasks.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance on domain-specific tasks for continual pre-training models. CPT indicates continual pre-training. ΔΔ\Deltaroman_Δ denotes training with our edited data. Our method demonstrates consistent improvements across three domains on both OLMo-1B and Llama-3-8B.

| PIQA | BoolQ | OBQA | ARC-c | ARC-e | HellaSwag | SIQA | Winogrande | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLMo-1B (PT) | 53.97 | 38.26 | 12.20 | 17.23 | 28.36 | 26.02 | 34.80 | 51.14 | 32.75 |

| Δ ToEdit | 54.13 | 38.65 | 12.80 | 18.43 | 27.48 | 25.94 | 34.95 | 52.49 | 33.11 |

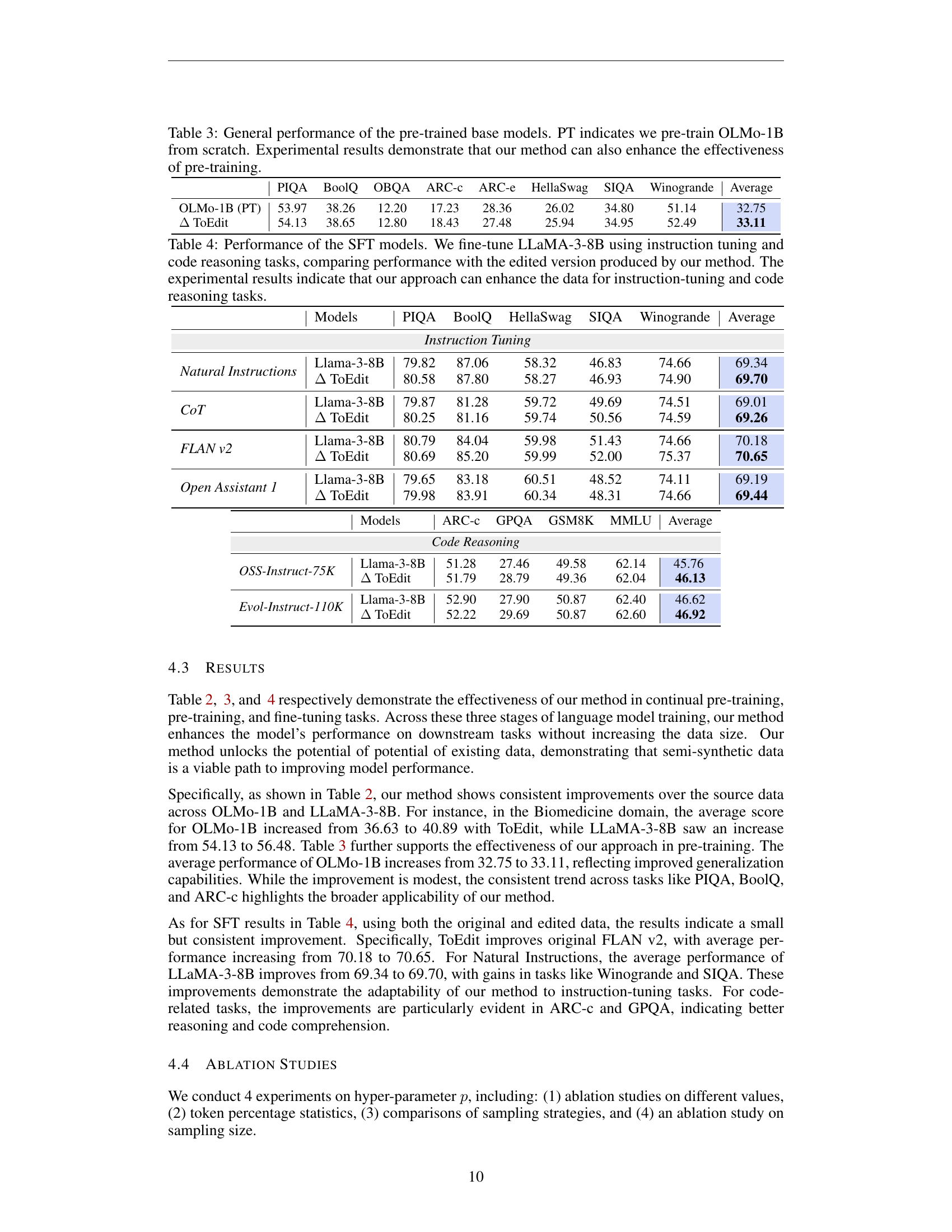

🔼 Table 3 presents the general performance comparison of pre-trained language models, specifically OLMo-1B, before and after applying the token-level editing technique introduced in the paper. The table shows results across various downstream tasks, highlighting the impact of pre-training from scratch (PT) versus pre-training enhanced by token-level editing on model performance. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method, even in the foundational stage of pre-training language models.

read the caption

Table 3: General performance of the pre-trained base models. PT indicates we pre-train OLMo-1B from scratch. Experimental results demonstrate that our method can also enhance the effectiveness of pre-training.

| Models | PIQA | BoolQ | HellaSwag | SIQA | Winogrande | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruction Tuning | |||||||

| Natural Instructions | Llama-3-8B | 79.82 | 87.06 | 58.32 | 46.83 | 74.66 | 69.34 |

| Δ ToEdit | 80.58 | 87.80 | 58.27 | 46.93 | 74.90 | 69.70 | |

| CoT | Llama-3-8B | 79.87 | 81.28 | 59.72 | 49.69 | 74.51 | 69.01 |

| Δ ToEdit | 80.25 | 81.16 | 59.74 | 50.56 | 74.59 | 69.26 | |

| FLAN v2 | Llama-3-8B | 80.79 | 84.04 | 59.98 | 51.43 | 74.66 | 70.18 |

| Δ ToEdit | 80.69 | 85.20 | 59.99 | 52.00 | 75.37 | 70.65 | |

| Open Assistant 1 | Llama-3-8B | 79.65 | 83.18 | 60.51 | 48.52 | 74.11 | 69.19 |

| Δ ToEdit | 79.98 | 83.91 | 60.34 | 48.31 | 74.66 | 69.44 |

🔼 This table presents the results of fine-tuning the LLaMA-3-8B language model using two sets of data: one original, and one processed using the authors’ token-level editing method. The model was fine-tuned on instruction tuning and code reasoning tasks. The table compares the performance of the model on various downstream tasks after training on both datasets, illustrating the improved performance achieved by using the edited dataset.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance of the SFT models. We fine-tune LLaMA-3-8B using instruction tuning and code reasoning tasks, comparing performance with the edited version produced by our method. The experimental results indicate that our approach can enhance the data for instruction-tuning and code reasoning tasks.

| Models | ARC-c | GPQA | GSM8K | MMLU | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code Reasoning | ||||||

| OSS-Instruct-75K | Llama-3-8B | 51.28 | 27.46 | 49.58 | 62.14 | 45.76 |

| Δ ToEdit | 51.79 | 28.79 | 49.36 | 62.04 | 46.13 | |

| Evol-Instruct-110K | Llama-3-8B | 52.90 | 27.90 | 50.87 | 62.40 | 46.62 |

| Δ ToEdit | 52.22 | 29.69 | 50.87 | 62.60 | 46.92 |

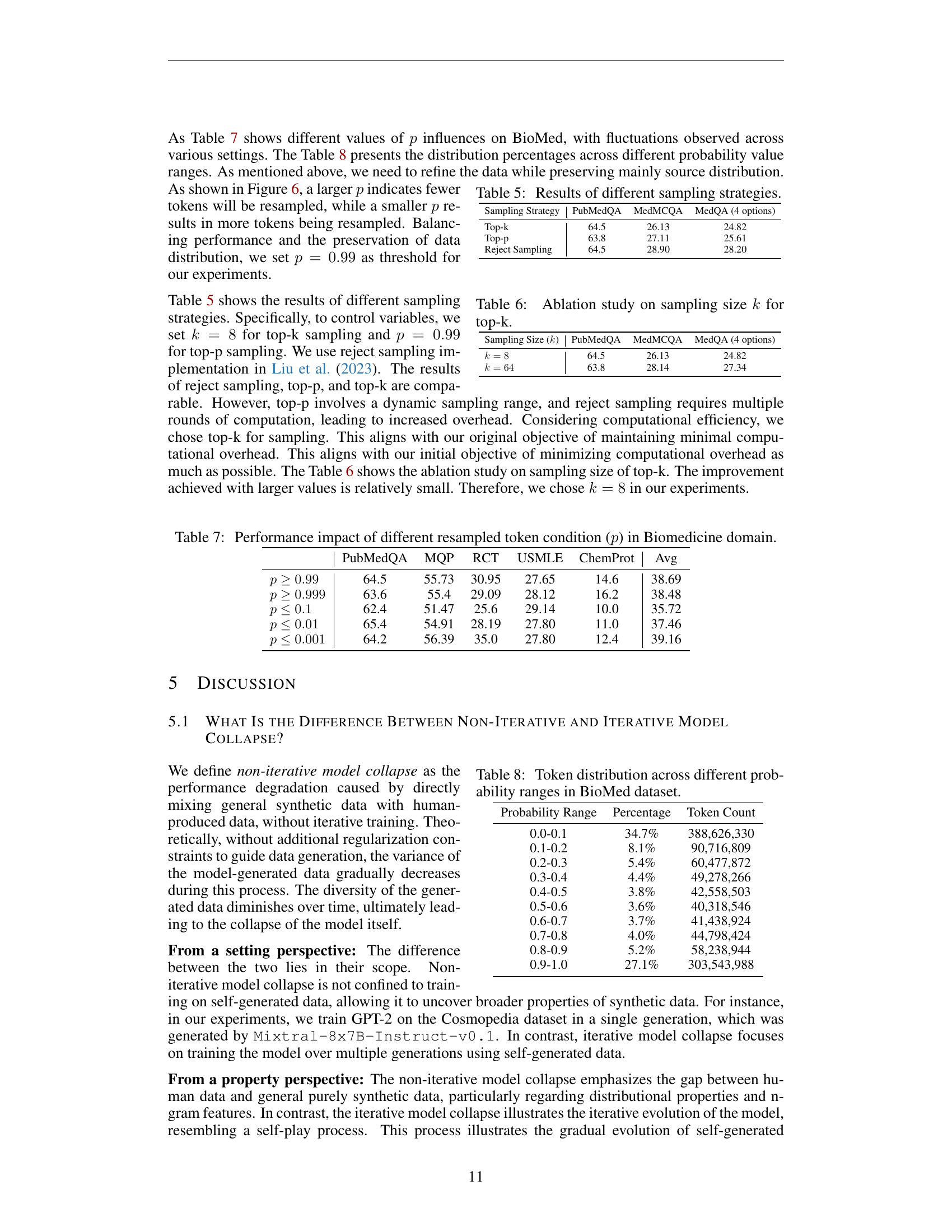

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different sampling strategies: top-k, top-p, and rejection sampling, on the PubMedQA, MedMCQA, and MedQA (4 options) tasks. It shows how different sampling methods affect the model’s ability to generalize and perform on these specific downstream tasks. The results are useful for understanding the trade-offs between these sampling techniques, helping to choose the best strategy for optimal model performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Results of different sampling strategies.

| Sampling Strategy | PubMedQA | MedMCQA | MedQA (4 options) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-k | 64.5 | 26.13 | 24.82 |

| Top-p | 63.8 | 27.11 | 25.61 |

| Reject Sampling | 64.5 | 28.90 | 28.20 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of different sampling sizes (k) on the performance of the top-k sampling strategy. The study examines how varying the value of k affects the performance on three downstream tasks: PubMedQA, MedMCQA, and MedQA (with 4 options). The results are used to determine the optimal k value that balances performance and computational efficiency.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation study on sampling size k𝑘kitalic_k for top-k.

| Sampling Size () | PubMedQA | MedMCQA | MedQA (4 options) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 64.5 | 26.13 | 24.82 | |

| 63.8 | 28.14 | 27.34 |

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of different resampling probability thresholds (p) on the performance of a language model trained on a biomedical dataset. Specifically, it shows how varying the threshold p, which determines the probability of replacing a token during data editing, affects the model’s performance across multiple evaluation metrics in the Biomedicine domain. The metrics shown are typical evaluation metrics for language models like MQP, ChemProt, PubMedQA, RCT, and USMLE.

read the caption

Table 7: Performance impact of different resampled token condition (p𝑝pitalic_p) in Biomedicine domain.

| p | PubMedQA | MQP | RCT | USMLE | ChemProt | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $p \geq 0.99$ | 64.5 | 55.73 | 30.95 | 27.65 | 14.6 | 38.69 |

| $p \geq 0.999$ | 63.6 | 55.4 | 29.09 | 28.12 | 16.2 | 38.48 |

| $p \leq 0.1$ | 62.4 | 51.47 | 25.6 | 29.14 | 10.0 | 35.72 |

| $p \leq 0.01$ | 65.4 | 54.91 | 28.19 | 27.80 | 11.0 | 37.46 |

| $p \leq 0.001$ | 64.2 | 56.39 | 35.0 | 27.80 | 12.4 | 39.16 |

🔼 This table shows the distribution of tokens within the BioMed dataset, categorized by their probability ranges. It illustrates the proportion of tokens falling into various probability intervals (e.g., 0.0-0.1, 0.1-0.2, etc.), providing insight into the data’s token probability distribution. This is relevant to understanding the characteristics of the data and how token probabilities relate to data quality and model training.

read the caption

Table 8: Token distribution across different probability ranges in BioMed dataset.

| Probability Range | Percentage | Token Count |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0-0.1 | 34.7% | 388,626,330 |

| 0.1-0.2 | 8.1% | 90,716,809 |

| 0.2-0.3 | 5.4% | 60,477,872 |

| 0.3-0.4 | 4.4% | 49,278,266 |

| 0.4-0.5 | 3.8% | 42,558,503 |

| 0.5-0.6 | 3.6% | 40,318,546 |

| 0.6-0.7 | 3.7% | 41,438,924 |

| 0.7-0.8 | 4.0% | 44,798,424 |

| 0.8-0.9 | 5.2% | 58,238,944 |

| 0.9-1.0 | 27.1% | 303,543,988 |

🔼 This table presents the percentage of tokens in the Natural Instructions dataset that required editing during the token-level editing process. The dataset contains a total of 4,671,834 tokens. The columns represent the generation number (Gen), indicating the iteration of the editing process, and the percentage of tokens requiring edits in that generation. The data shows a gradual decrease in the percentage of tokens requiring edits across generations, demonstrating the effectiveness of the token-level editing method in refining the data over successive iterations.

read the caption

Table 9: Percentage of tokens requiring edits in the Natural-Instructions dataset. The total number of tokens is 4,671,834. and “Gen” is short for “Generation”.

| Tokens (p>0.99) | Gen 1 (source) | Gen 2 | Gen 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 584,103 | 12.5% | 11.76% | 11.08% |

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of language models trained on different proportions of human-generated and synthetic text data. The models were evaluated on several downstream tasks from the Maini et al. (2024) benchmark, using GPT-2 as the base model. The results show how the model’s performance on these tasks changes with increasing amounts of synthetic data in the training set. It demonstrates the impact of synthetic data on language model generalization and performance.

read the caption

Table 10: Comparison of human and synthetic data performance across downstream tasks in (Maini et al., 2024), based on training with GPT-2.

| TruthfulQA | LogiQA | Wino. | PIQA | ARC-E | BoolQ | OBQA | Avg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Data | 32.68 | 23.03 | 51.3 | 64.42 | 44.4 | 60.98 | 15 | 41.69 |

| 25% Synthetic Data | 27.91 | 21.37 | 50.12 | 63.93 | 43.94 | 62.29 | 15.4 | 40.71 |

| 50% Synthetic Data | 30.84 | 22.58 | 52.41 | 63.33 | 44.02 | 62.14 | 16 | 41.62 |

| 75% Synthetic Data | 29.5 | 22.65 | 49.8 | 63.44 | 44.53 | 61.56 | 17.2 | 41.24 |

| Synthetic Data | 28.89 | 22.58 | 49.72 | 63 | 46.3 | 54.53 | 16.8 | 40.26 |

🔼 This table presents a detailed comparison of the performance achieved by language models trained on various mixtures of human and synthetic data. Specifically, it evaluates the performance on multiple downstream tasks using the OLMo-237M model. The results highlight the impact of using different ratios of synthetic data in the training process. The standard error for each result is included, providing a measure of the reliability of the results. The comparison includes results for models trained entirely on human data, models trained on mixtures of human and synthetic data at different ratios, and models trained on pure synthetic data. The table offers insights into the effects of synthetic data on the generalizability and performance of language models.

read the caption

Table 11: Comparison of human and synthetic data performance across downstream tasks in (Maini et al., 2024), based on training with OLMo-237M. ± indicates the standard error.

| TruthfulQA | LogiQA | Wino. | PIQA | ARC-E | OBQA | Avg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Data | 26.81 ± 1.550 | 21.06 ± 1.028 | 52.01 ± 1.404 | 56.69 ± 1.156 | 31.73 ± 0.9550 | 13.80 ± 1.543 | 33.68 |

| 25% Synthetic Data | 26.44 ± 1.543 | 21.25 ± 1.032 | 52.64 ± 1.403 | 57.02 ± 1.155 | 31.78 ± 0.9552 | 12.40 ± 1.475 | 33.59 |

| 50% Synthetic Data | 25.95 ± 1.534 | 20.04 ± 1.099 | 52.25 ± 1.408 | 56.64 ± 1.126 | 31.82 ± 0.9557 | 12.80 ± 1.495 | 33.25 |

| 75% Synthetic Data | 25.34 ± 1.522 | 20.87 ± 1.025 | 50.43 ± 1.405 | 55.60 ± 1.159 | 32.74 ± 0.9629 | 12.00 ± 1.454 | 32.83 |

| Synthetic Data | 23.01 ± 1.473 | 20.29 ± 1.014 | 49.33 ± 1.405 | 55.93 ± 1.158 | 33.33 ± 0.9673 | 14.20 ± 1.562 | 32.68 |

🔼 This table presents the perplexity (PPL) scores achieved by the GPT-2 124M language model during pretraining. The model was trained on various mixtures of human-generated data (Dolma) and synthetic data (Cosmopedia), with the proportions of each type of data varying across different rows. The columns represent different datasets used for evaluation (Wikitext-103, RedPajama, Falcon-RefinedWeb, c4-en, mc4-en). The table shows how the model’s performance, as measured by PPL, changes as the ratio of synthetic to human data in the training set is altered.

read the caption

Table 12: PPL results of GPT-2 124M pretraining on mixture of human and synthetic data.

| Synthetic Data Ratio | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 50% | 75% | 75% | 75% | 75% | 75% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tokens Size | 8.4B | 16.8B | 25.2B | 33.6B | 42B | 8.4B | 16.8B | 25.2B | 33.6B | 42B | 8.4B | 16.8B | 25.2B | 33.6B | 42B | |

| Epochs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Wikitext-103 | 45.97 | 39.87 | 37.65 | 36.91 | 36.32 | 50.29 | 43.15 | 40.46 | 39.43 | 38.65 | 58.66 | 48.75 | 45.20 | 43.42 | 42.95 | |

| RedPajama | 42.28 | 37.62 | 35.72 | 34.66 | 34.24 | 46.89 | 41.42 | 39.37 | 38.21 | 37.72 | 55.72 | 49.26 | 46.27 | 44.81 | 44.30 | |

| Falcon-RefinedWeb | 56.40 | 50.62 | 48.26 | 47.13 | 46.66 | 61.06 | 54.34 | 51.72 | 50.39 | 49.87 | 69.32 | 61.50 | 58.28 | 56.77 | 56.19 | |

| c4-en | 48.15 | 43.14 | 40.98 | 39.91 | 39.41 | 51.79 | 46.06 | 43.90 | 42.73 | 42.23 | 58.60 | 52.22 | 49.26 | 47.87 | 47.27 | |

| mc4-en | 62.46 | 56.80 | 54.35 | 53.06 | 52.71 | 70.43 | 62.48 | 59.61 | 57.66 | 57.07 | 80.37 | 71.77 | 67.90 | 65.31 | 64.82 |

🔼 This table presents the perplexity (PPL) scores achieved by the OLMo-237M language model during pretraining. The model was trained on various mixtures of human-produced and synthetic data. Different proportions of synthetic data (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%) were used in the training process. The table shows the PPL on several downstream datasets (Wikitext-103, RedPajama, Falcon-RefinedWeb, c4-en, mc4-en, M2D2-Wiki, M2D2-S2ORC), demonstrating the impact of varying synthetic data ratios on model performance.

read the caption

Table 13: PPL results of OLMo-237M pretraining on mixture of human and synthetic data.

| Synthetic Data Ratio | 0% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 100% | DSIR (1M) | DSIR (10M) | Edu Classifier (1M) | Edu Classifier (10M) | PPL Filter (1M) | PPL Filter (10M) | Density Sampling (1M) | Density Sampling (10M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique Tokens | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 0.6B | 8.4B | 0.75B | 7.4B | 0.97B | 9B | 0.6B | 7.1B |

| Training Tokens | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 8.4B | 10.5B | 7.4B | 13.68B | 9B | 8.9B | 7.1B |

| Epochs | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 1 | 14 | 1 |

| Wikitext-103 | 187.36 | 185.5 | 260.08 | 367.46 | 1605.73 | 1309.53 | 1757.03 | 1111.29 | 1612.95 | 738.36 | 1193.25 | 1188.40 | 1753.89 |

| RedPajama | 175.38 | 183.93 | 236.33 | 301.09 | 907.91 | 649.36 | 916.51 | 811.14 | 1104.75 | 376.36 | 645.82 | 789.67 | 896.18 |

| Falcon-RefinedWeb | 165.17 | 166.69 | 199.68 | 245.15 | 523.93 | 573.61 | 510.96 | 522.97 | 612.72 | 344.82 | 449.86 | 501.99 | 560.92 |

| c4-en | 123.88 | 127.68 | 147.69 | 174.48 | 410.19 | 457.96 | 404.63 | 415.88 | 487.97 | 286.95 | 367.44 | 414.55 | 457.71 |

| mc4-en | 208.91 | 208.94 | 263.35 | 324.91 | 800.40 | 861.01 | 823.12 | 769.86 | 955.70 | 476.81 | 662.00 | 740.75 | 844.53 |

| M2D2-Wiki | 88.24 | 87.34 | 107.77 | 114.19 | 189.06 | 234.45 | 183.17 | 161.58 | 206.45 | 130.43 | 162.08 | 167.20 | 205.50 |

| M2D2-S2ORC | 86.15 | 81.53 | 97.61 | 100.64 | 204.22 | 170.78 | 496.40 | 145.27 | 201.52 | 117.44 | 163.38 | 131.22 | 192.97 |

🔼 This table compares three different methods for generating synthetic data for language models: Cosmopedia, Rephrasing the Web, and ToEdit (the proposed method). It shows the type of synthetic data generated (purely synthetic vs. semi-synthetic), the approach used to generate the data, and the resulting impact on model training (model collapse or performance improvement).

read the caption

Table 14: Comparison of different synthetic data methods.

| Method | Data Type | Approach | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmopedia (Ben Allal et al., 2024) | Pure synthetic | Using a prompt to induce data from LLMs. | Reveal non-iterative model collapse. |

| Rephrasing the Web (Maini et al., 2024) | Semi-synthetic | Using a prompt and source content to guide LLMs to reformat source content. | Improve training performance. |

| ToEdit (Ours) | Semi-synthetic | Using the distribution of source content estimated by LLMs (single forward pass) to replace tokens. | Improve training performance. |

🔼 This table presents the perplexity (PPL) scores achieved by a GPT-2 language model (124M parameters) after being pre-trained on either purely human-generated text data or purely synthetic text data. It compares the model’s performance across various dataset sizes and training epochs, illustrating the impact of using only human-generated versus only synthetic data on the model’s ability to generalize well.

read the caption

Table 15: PPL results of GPT-2 124M pretraining on pure Human or Synthetic data.

| Data Type | Human Data (Dolma) | Synthetic Data (Cosmopedia) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tokens Size | 8.4B | 16.8B | 25.2B | 33.6B | 42B | 8.4B | 16.8B | 25.2B | 33.6B | 42B |

| Epochs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Wikitext-103 | 43.62 | 38.57 | 36.11 | 34.89 | 34.55 | 169.38 | 147.73 | 135.23 | 131.78 | 128.05 |

| RedPajama | 40.18 | 35.84 | 33.97 | 32.74 | 32.34 | 116.37 | 103.25 | 99.27 | 96.81 | 96.03 |

| Falcon-RefinedWeb | 54.85 | 49.10 | 46.93 | 45.43 | 44.90 | 146.97 | 132.60 | 127.68 | 124.32 | 122.69 |

| c4-en | 45.87 | 41.00 | 39.10 | 37.95 | 37.56 | 128.25 | 114.41 | 109.73 | 107.53 | 106.55 |

| mc4-en | 61.00 | 54.44 | 52.11 | 50.38 | 49.74 | 171.44 | 153.70 | 150.28 | 145.44 | 144.99 |

🔼 Table 16 provides a detailed breakdown of the Dolma dataset (version 1.6), which is a large-scale dataset used for training language models. It lists the source of the data, the type of documents included (e.g., web pages, code, social media posts, scientific papers), and the size of the dataset in terms of UTF-8 bytes, the number of documents, and the number of Unicode words. This information is valuable for understanding the composition and scale of the dataset used in training language models and helps to compare it to other datasets used in similar research.

read the caption

Table 16: Dolma dataset statistics (v1.6), quoted from source (Soldaini et al., 2024).

Full paper#