↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Current multi-modal conversation datasets mostly focus on two-party interactions with limited visual context, hindering research on more realistic, complex scenarios. The lack of speaker information in these datasets further limits the ability to model character-centric understanding, a key aspect of natural conversation.

This paper introduces Friends-MMC, a novel dataset addressing these issues. Friends-MMC uses the TV series “Friends” to create a dataset with rich multi-modal data (video, audio, text) and crucial speaker annotations. The study benchmarks two core tasks: conversation speaker identification and response prediction, demonstrating that using the proposed methodologies that incorporate speaker information leads to improved performance compared to text-only methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limitations of existing multi-modal conversation datasets by introducing Friends-MMC, a dataset focused on multi-party conversations with rich visual and audio context. This allows researchers to advance the understanding of complex real-world interactions, driving progress in AI, especially in areas like embodied AI and conversational AI. The proposed methods for speaker identification and response prediction also provide valuable baselines for future research.

Visual Insights#

🔼 Figure 1 shows an example of a multi-modal, multi-party conversation from the Friends-MMC dataset. The image displays several characters from the TV show Friends along with corresponding dialogue. The task of conversation speaker identification involves determining which speaker produced each utterance (represented by dotted arrows). The task of conversation response prediction focuses on identifying the final utterance within the conversation snippet (enclosed in a dotted rectangle). Note that only a single video frame is shown as visual context for clarity.

read the caption

Figure 1: An example of multi-modal multi-party conversation. The task of conversation speaker identification is to infer the dotted arrows pointing from characters to utterances, and the task of conversation response prediction is to infer the last utterance in the dotted rectangular. Only one frame of the video is shown as the visual context to avoid clutter.

| 5 turns | 8 turns | |

|---|---|---|

| train | test | |

| # sessions | 13584 | 2017 |

| # unique turns | 21092 | 3069 |

| # words in utterance | 18.87 | 20.28 |

| # speakers in each session | 2.83 | 2.85 |

| # face tracks per clip | 2.41 | 3.12 |

| avg. secs per face track | 2.31 | 2.71 |

| % speakers not in current clip | 13.43 | 1.03 |

| % speakers not in all clips | 6.13 | 0.17 |

| # faces per frame | 1.61 | 2.20 |

| % speakers not in current frame | 24.05 | 6.52 |

| % speakers not in all frames | 9.53 | 1.01 |

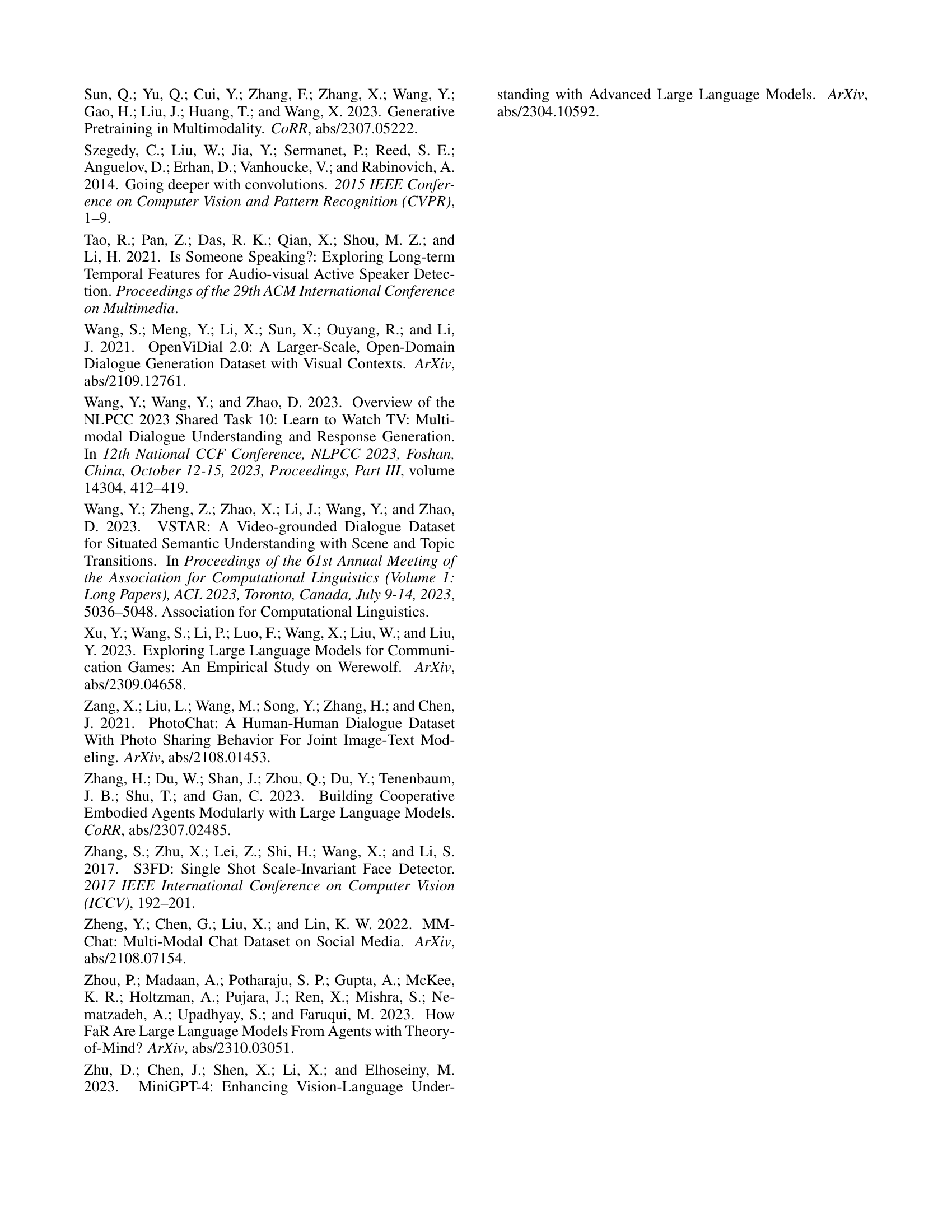

🔼 Table 1 presents a statistical overview of the Friends-MMC dataset. It breaks down the dataset into three subsets: a training set, a standard test set, and a more challenging ’test-noisy’ set. For each set, it provides key statistics including the number of sessions, unique turns, words per utterance, average number of speakers per session, the percentage of speakers whose faces are not detected in the current frame or clip, and the number of face tracks per clip. These statistics offer valuable insights into the dataset’s composition and complexity, highlighting the potential challenges for modeling multi-modal multi-party conversations.

read the caption

Table 1: Dataset Statistics of Friends-MMC. We provide a train set, a test set and a more challenging test-noisy set.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal MMC#

Multimodal MMC, or Multimodal Multi-party Conversation, represents a significant advancement in conversational AI. It moves beyond the limitations of traditional multimodal dialogue systems, which often involve only two participants and a pre-defined visual context, by focusing on realistic, multi-party interactions deeply embedded within rich, dynamic visual and auditory scenes. This shift necessitates more sophisticated models capable of character-centric understanding, distinguishing between speakers and tracking their contributions within the complex interplay of multiple modalities. The challenge lies not only in processing the various inputs (text, audio, video) simultaneously but also in intelligently fusing this information to accurately discern speaker roles, predict responses, and comprehensively understand the conversational flow. The key advantage is in creating AI systems that better mirror real-world human interaction, which would unlock many valuable applications. Research in this area is crucial for developing robust, human-like conversational agents that can participate naturally in complex, multi-modal scenarios.

Speaker ID Model#

A robust speaker identification model for multi-modal multi-party conversations needs to effectively integrate visual and textual cues. Visual modeling could leverage facial recognition and analysis of visual context within video frames to identify the active speaker. However, this alone is insufficient due to occlusions and similar appearances. Textual modeling should capture conversational context, utilizing techniques like dialogue context encoding and speaker-specific language models to disambiguate utterances. A fusion strategy is crucial, likely involving a weighted combination of visual and textual probabilities, potentially using a mechanism like quadratic binary optimization to combine the modalities’ scores. This integrated approach is essential because visual data alone is not always reliable for speaker identification in dynamic, multi-party settings. Successfully integrating multiple modalities will be key for achieving high accuracy and robustness in such a complex scenario. The system needs to handle scenarios where speakers are not visually present, relying solely on contextual clues from the text. Therefore, the model’s architecture must be flexible and robust, capable of handling various scenarios and information availability.

Friends-MMC Dataset#

The Friends-MMC dataset represents a significant contribution to the field of multi-modal multi-party conversation understanding. Its novelty lies in its real-world setting, drawn from the popular TV series Friends, providing a more natural and complex conversational structure than typical lab-created datasets. The dataset’s rich multi-modality, including video, audio, transcripts, facial tracks, and speaker labels, presents researchers with an unprecedented opportunity to train and evaluate models that can accurately understand nuanced interactions among multiple individuals. The inclusion of speaker labels is particularly important, facilitating research into character-centered understanding, an area lacking in most existing resources. Annotation challenges, particularly automatic face labeling, are acknowledged, highlighting the meticulous effort in constructing a high-quality dataset. The dataset’s release encourages more research into the complexities of multi-party conversations with multi-modal inputs, helping bridge the gap between theoretical research and real-world applications.

Response Prediction#

Response prediction in multi-modal, multi-party conversations presents unique challenges. Unlike traditional dialogue systems, predicting responses here requires understanding not only the conversational history and visual context but also the dynamics of multiple speakers. Speaker identification is crucial, as it informs the model about the perspective and communication style influencing each utterance, making the task significantly more complex than simple next-utterance prediction. The presence of visual information adds another layer of intricacy, demanding that the model correctly interpret visual cues – facial expressions, gestures, and scene context – and integrate them with linguistic data. Effective models must learn to disentangle speaker roles and intentions, resolving ambiguities arising from overlapping speech or indirect references. This requires advanced techniques beyond standard sequence-to-sequence models and may necessitate incorporating knowledge graphs or other relational representations to capture multi-party interaction patterns. Ultimately, successful response prediction in this setting hinges on the model’s ability to robustly fuse diverse modalities and build a comprehensive understanding of the situated context of the conversation, surpassing simple keyword matching or basic contextual understanding.

Future of MMC#

The future of Multi-modal Multi-party Conversation (MMC) understanding is bright, driven by the increasing availability of large, high-quality datasets like Friends-MMC. Further research should focus on developing more sophisticated models that can effectively integrate various modalities, including text, audio, and video, to achieve a deeper, more nuanced understanding of multi-party interactions. Addressing the challenges of speaker diarization in noisy or complex environments is crucial, perhaps through advancements in robust audio-visual feature extraction and novel attention mechanisms. Improving the efficiency and scalability of MMC models for real-time applications is another important direction, especially considering the computational demands of processing multiple modalities simultaneously. Exploring the use of advanced techniques such as graph neural networks to capture the intricate relationships between speakers and the flow of conversation could unlock significant advancements. Finally, developing benchmark tasks and evaluation metrics that better reflect the complexities of real-world MMC scenarios is vital for pushing forward the field and fostering further innovation. The ultimate goal is to create truly intelligent systems capable of seamlessly participating in and understanding complex, multi-modal conversations among multiple individuals, ushering in a new era of human-computer interaction.

More visual insights#

More on figures

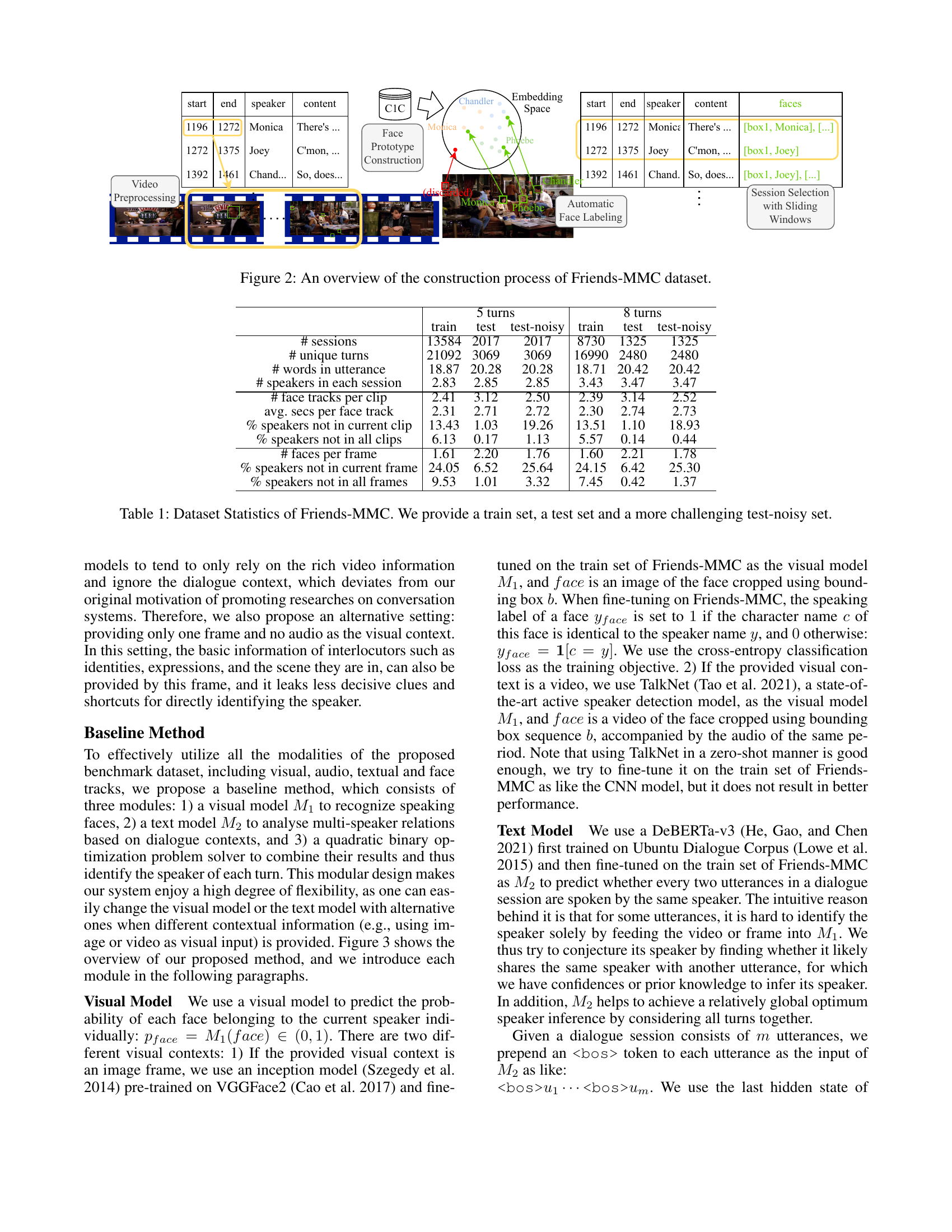

🔼 This figure illustrates the data pipeline for creating the Friends-MMC dataset. It begins with video preprocessing, where video clips are extracted based on timestamps from subtitles. Next, face detection and tracking identify and group faces across frames, forming face tracks. These tracks are then labeled with character names using a face prototype matching approach, leveraging pre-trained models and a similarity threshold. A validation step ensures accuracy against manually labeled data. The process culminates in session selection using sliding windows, combining multiple consecutive turns into dialogue sessions, which finally produces the Friends-MMC dataset.

read the caption

Figure 2: An overview of the construction process of Friends-MMC dataset.

🔼 Figure 3 illustrates the architecture of the proposed baseline model for conversation speaker identification. It’s a modular design with three main components: a visual module (M1) represented in yellow, a textual module (M2) in green, and a quadratic binary optimization solver in blue. The visual module processes visual features (either from an image or a video) to estimate the probability of each detected face being the speaker. The textual module analyzes the conversational context to identify relations between utterances. These two modules’ outputs are then combined using the optimization solver to determine the final speaker identification for each turn.

read the caption

Figure 3: Model overview of the three modules in different colors: the visual (M1subscript𝑀1M_{1}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) is yellow, the textual (M2subscript𝑀2M_{2}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 2 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) is green, and the optimization solver taking vision and text reward matrix as input is blue.

More on tables

| 5 turns | 5 turns | 8 turns | 8 turns | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| noisy | noisy | ||||

| 0 | random | 31.82 | 32.61 | 28.54 | 29.03 |

| (std.dev.) | (0.25) | (0.47) | (0.49) | (0.27) | |

| Frame Only | |||||

| 1 | $M_{1}$(CNN) | 72.88 | 63.72 | 72.90 | 62.51 |

| Video Only | |||||

| 2 | $M_{1}$(TalkNet) | 80.89 | 70.91 | 81.00 | 70.50 |

| Text Only | |||||

| 3 | $M_{2}$ | 33.24 | 33.85 | 29.09 | 29.33 |

| 4 | GPT 3.5 (3-shot) | 37.21 | 37.24 | 33.35 | 32.81 |

| Use image and text modality | |||||

| 5 | Violet | 32.66 | 33.16 | 27.73 | 28.86 |

| 6 | LLaVA v1.5-13B | 46.30 | 42.39 | 45.73 | 41.41 |

| 7 | Emu-14B | 61.76 | 58.23 | 60.96 | 56.46 |

| 8 | $M_{1}$(CNN) + $M_{2}$ | 75.81 | 68.61 | 74.53 | 67.21 |

| 9 | $M_{1}$(CNN) + $M_{2}^{ | ||||

| ormalsize †}$ | 84.90 | 78.01 | 90.80 | 83.93 | |

| 10 | GPT-4o (0-shot) | 66.36 | 65.60 | 63.64 | 61.02 |

| 11 | Human | 82.25 | - | 84.49 | - |

| Use video and text modality | |||||

| 12 | $M_{1}$(TalkNet) + $M_{2}$ | 83.21 | 74.12 | 83.60 | 75.00 |

| 13 | $M_{1}$(TalkNet) + $M_{2}^{ | ||||

| ormalsize †}$ | 90.88 | 83.09 | 95.10 | 89.69 |

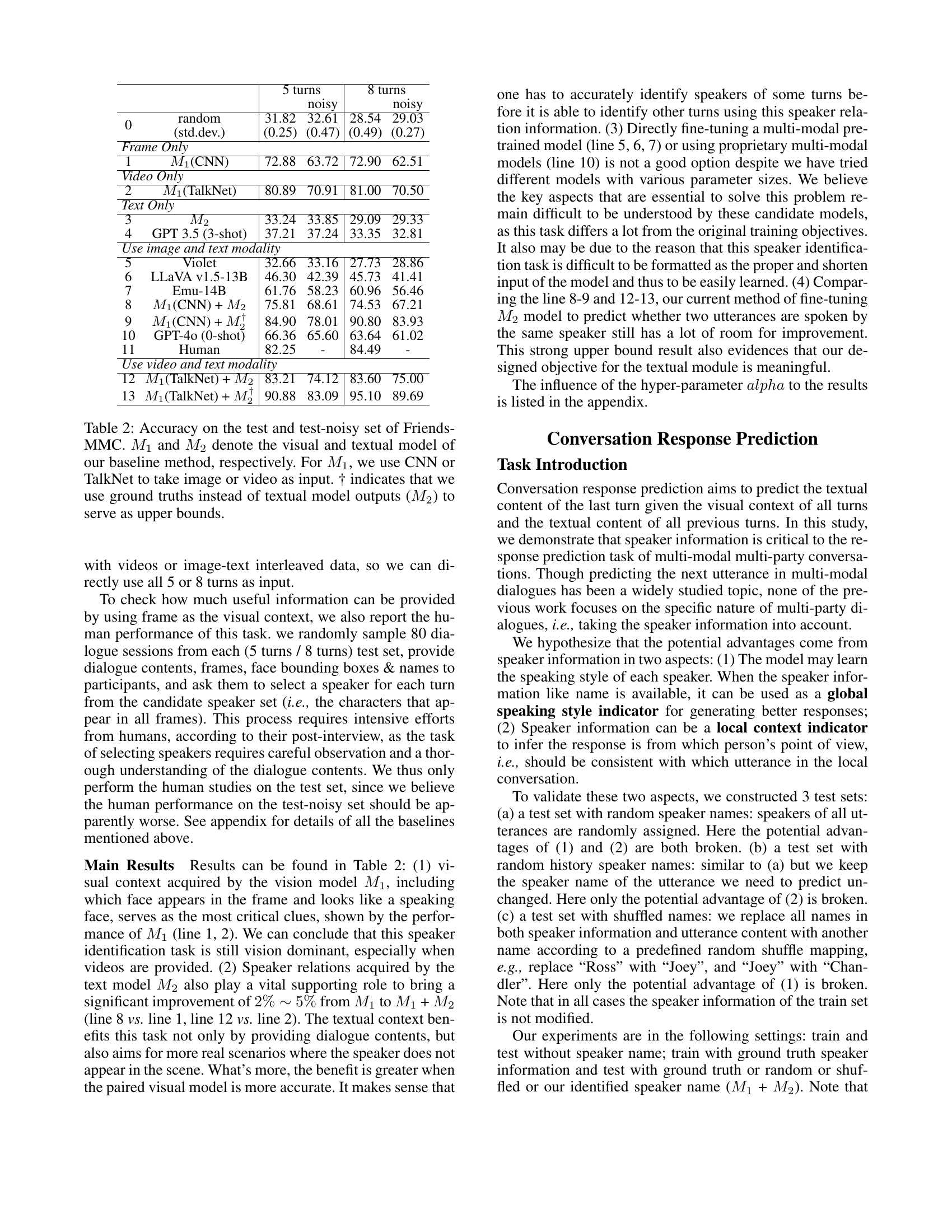

🔼 Table 2 presents the accuracy results of the proposed baseline model for conversation speaker identification on the Friends-MMC dataset. It compares performance using different combinations of modalities: image-only (CNN), video-only (TalkNet), text-only (M2 and GPT-3.5), image+text, and video+text. The table also shows results from various pre-trained models such as Violet, LLaVA, and Emu for comparison, and includes a human performance baseline. The ’test-noisy’ set is a more challenging subset of the test set with 20% of face tracks randomly removed. The results show how using both visual and textual information improves accuracy significantly over using a single modality, and that the proposed baseline outperforms pre-trained models.

read the caption

Table 2: Accuracy on the test and test-noisy set of Friends-MMC. M1subscript𝑀1M_{1}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and M2subscript𝑀2M_{2}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 2 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denote the visual and textual model of our baseline method, respectively. For M1subscript𝑀1M_{1}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 1 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, we use CNN or TalkNet to take image or video as input. † indicates that we use ground truths instead of textual model outputs (M2subscript𝑀2M_{2}italic_M start_POSTSUBSCRIPT 2 end_POSTSUBSCRIPT) to serve as upper bounds.

| Model | Speaker | 5 turns | 8 turns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Llama2-7B | No | 30.69 | 36.98 |

| Random | 31.23 | 43.32 | |

| Random History | 31.63 | 43.40 | |

| Shuffled | 35.20 | 48.60 | |

| Ground truth | 36.89 | 49.36 | |

| $M_{1}$(CNN) + $M_{2}$ | 34.16 | 45.81 | |

| $M_{1}$(TalkNet) + $M_{2}$ | 34.56 | 46.64 | |

| Emu-14B | No | 30.49 | 31.09 |

| Random | 29.35 | 31.55 | |

| Random History | 29.45 | 31.25 | |

| Shuffled | 33.02 | 35.17 | |

| Ground truth | 34.06 | 36.30 | |

| $M_{1}$(CNN) + $M_{2}$ | 31.98 | 33.89 | |

| $M_{1}$(TalkNet) + $M_{2}$ | 32.97 | 34.64 |

🔼 This table presents the accuracy of conversation response prediction results. The model predicts the most likely final utterance from a set of ten candidate utterances, given the visual context and preceding utterances. Results are broken down by different experimental conditions, including whether the model was trained with ground truth speaker information, random speaker information, shuffled speaker names, or speaker information predicted by the model. The accuracy is shown for both 5-turn and 8-turn conversations.

read the caption

Table 3: Accuracy of conversation response prediction by selecting one from a set of ten utterances as candidates.

Full paper#