↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Large multimodal models (LMMs) struggle with reasoning, particularly due to the scarcity of high-quality annotated data. Self-evolving training, where models learn from their own outputs, presents a promising solution, but its application in the multimodal domain has been limited. This paper addresses this gap by systematically investigating self-evolving training for multimodal reasoning. This includes exploring different training methods, reward models, and prompt variations, highlighting key factors influencing training effectiveness.

The researchers propose M-STAR, a novel framework that incorporates the best practices discovered during this systematic investigation. M-STAR demonstrates a significant improvement in multimodal reasoning abilities across various benchmarks and different model sizes. Notably, it achieves these advancements without human annotation, thus addressing the scarcity of annotated data. The study also reveals important insights into the dynamics of self-evolving training and introduces techniques for optimizing model exploration and exploitation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multimodal learning because it introduces a novel self-evolving training framework (M-STAR) that significantly enhances reasoning abilities in large multimodal models without requiring additional human-annotated data. This addresses a key limitation in the field and opens new avenues for research into more efficient and scalable training methods for complex AI systems. The release of the model’s policy and reward models further facilitates future investigation and replication.

Visual Insights#

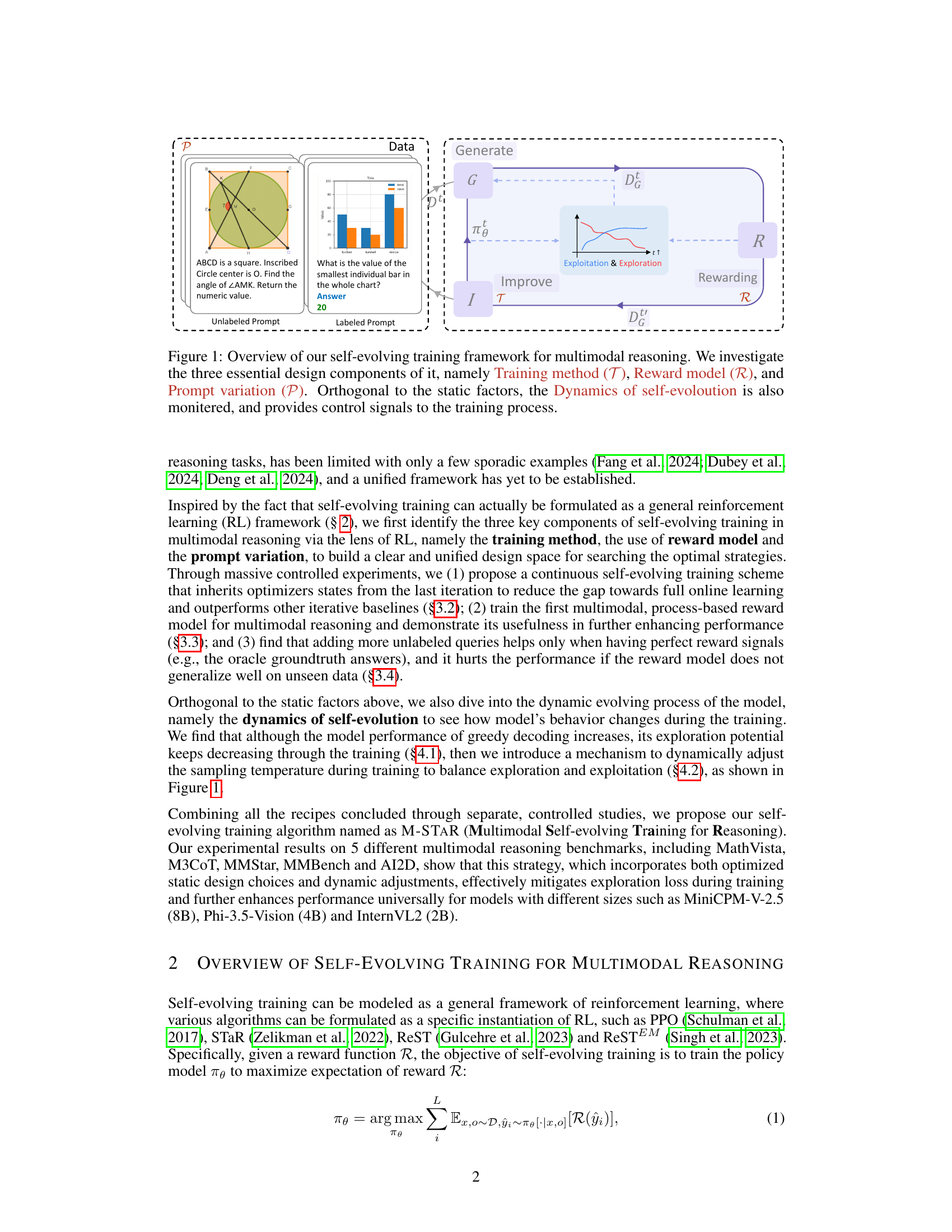

🔼 This figure illustrates the self-evolving training framework for multimodal reasoning. It highlights three key factors: the training method (how the model is updated), the reward model (how the model’s performance is evaluated), and prompt variation (how the input prompts are modified). The framework also monitors the dynamics of self-evolution, using the observed dynamics to provide feedback and adjust the training process. This dynamic adjustment helps optimize the model’s reasoning abilities.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our self-evolving training framework for multimodal reasoning. We investigate the three essential design components of it, namely Training method (𝒯𝒯\mathcal{T}caligraphic_T), Reward model (ℛℛ\mathcal{R}caligraphic_R), and Prompt variation (𝒫𝒫\mathcal{P}caligraphic_P). Orthogonal to the static factors, the Dynamics of self-evoloution is also monitered, and provides control signals to the training process.

| Method | \mathcal{M} | \mathcal{O} | Iteration Interval (#) | MathV360K | MathVista |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiniCPM-V-2.5 | - | - | - | 13.6 | 52.4 |

| +warmup | - | - | - | 38.8 | 52.6 |

| SFT | - | - | - | 44.3 | 54.8 |

| Iterative RFT | \pi_{\theta}^{t} | \times | 100%(180K) | 42.3 | 55.7 |

| RestEM | \pi_{\theta}^{0} | \times | 100%(180K) | 42.3 | 55.1 |

| Continous Self-Evolving | \pi_{\theta}^{t} | \checkmark | 100%(180K) | 42.2 | 56.7 |

| 50%(90K) | 43.1 | 56.2 | |||

| 25%(45K) | 43.1 | 57.2 | |||

| 12.5%(22K) | 42.3 | 56.1 | |||

| 6.25%(11K) | 41.0 | 56.8 |

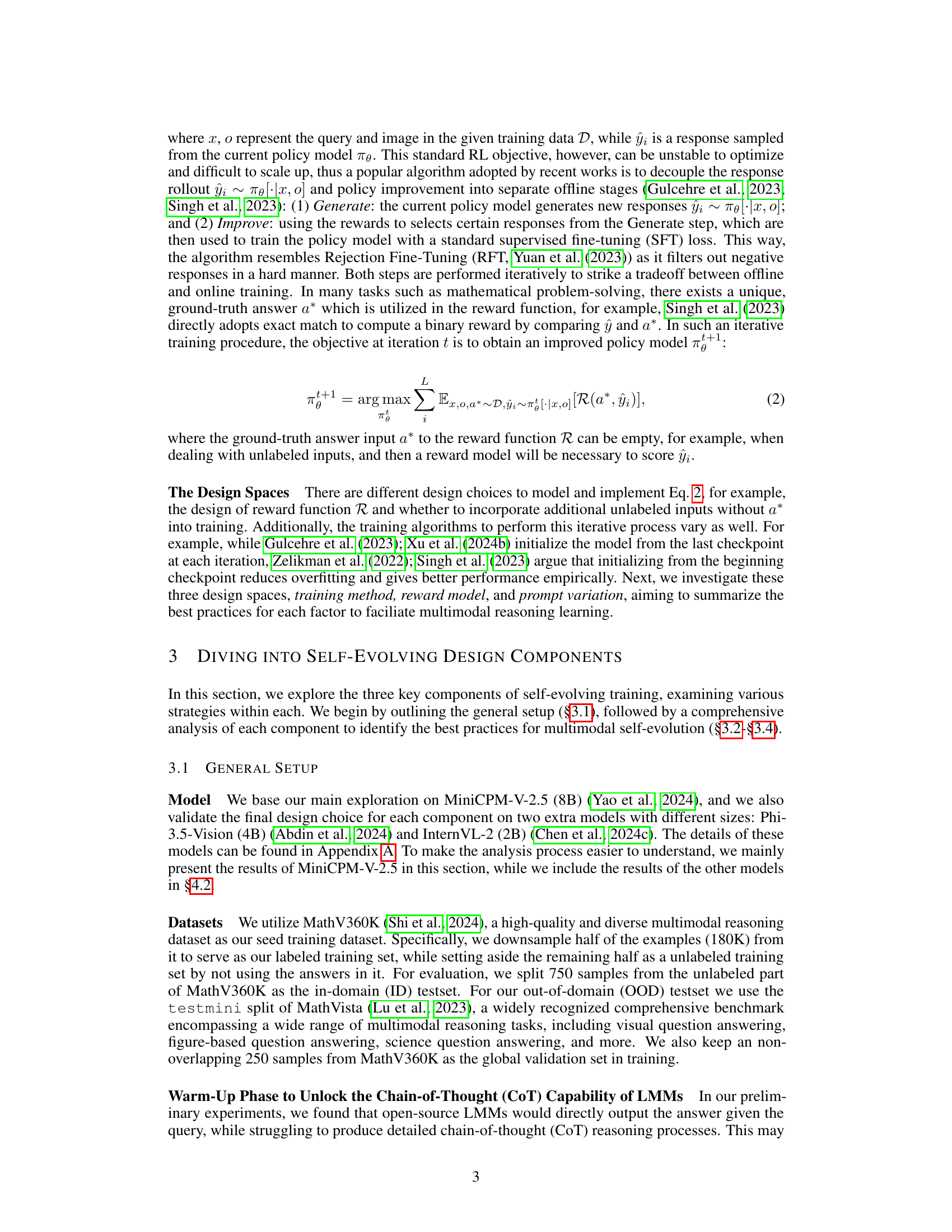

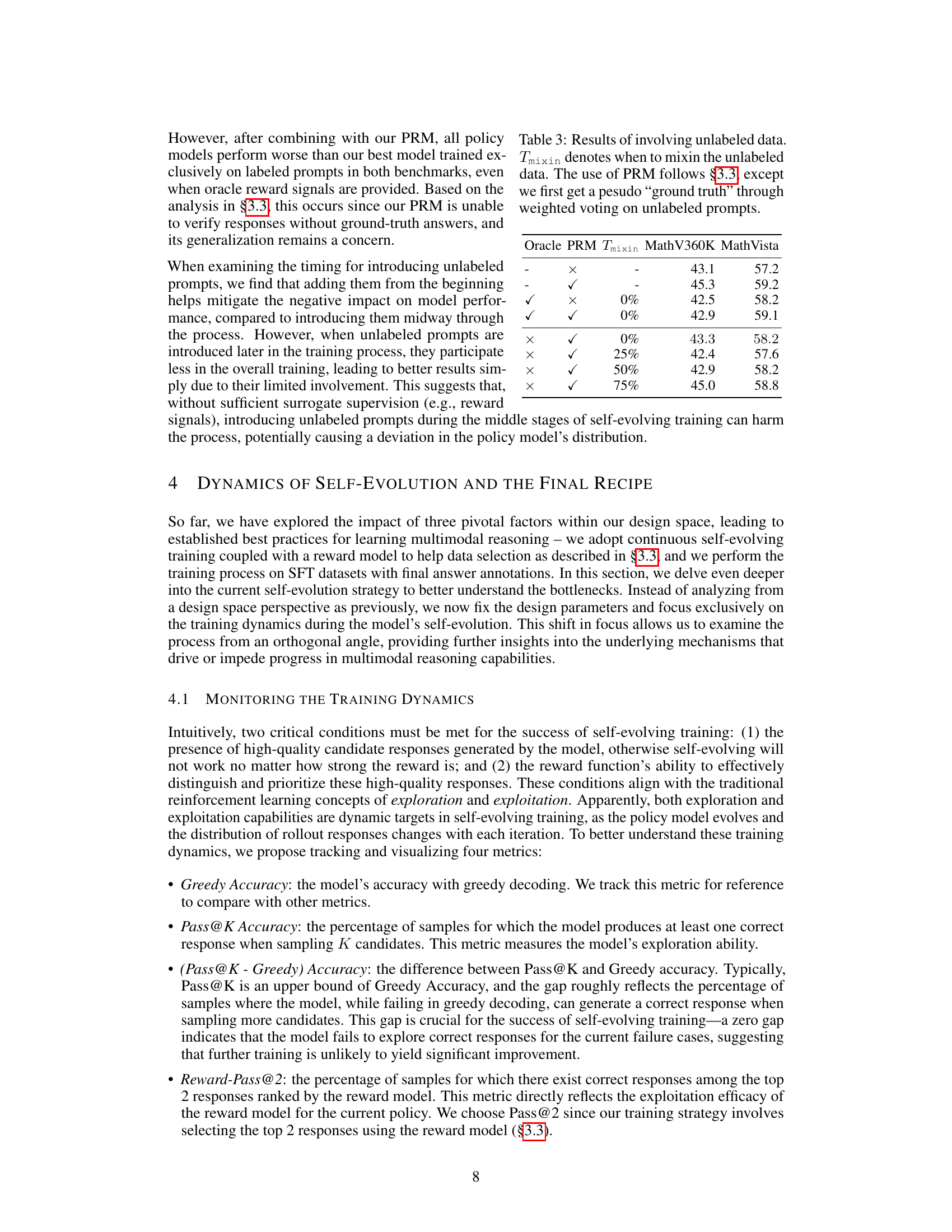

🔼 Table 1 presents a detailed comparison of different self-evolving training methods and their impact on model accuracy. It explores the effects of varying the training method (continuous vs. iterative), the initialization of the policy model at each iteration, and the size of the data processed in each iteration (iteration interval). The table shows accuracy results on the MathV360K and MathVista datasets. For a complete breakdown of performance across all MathVista subtasks, please refer to Table 4 in the paper.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy results (%) of self-evolving training using various training methods and iteration intervals. Iteration Interval (#) stands for the ratio of data we traverse in one iteration, and we also record the number of corresponding queries. ℳℳ\mathcal{M}caligraphic_M represents the policy model from which training is initialized in each iteration. 𝒪𝒪\mathcal{O}caligraphic_O denotes whether the optimization process is continuous, i.e., the optimizer states and lr scheduler are inherited from the last checkpoint. Please refer to Table 4 to check the full results on all sub-tasks of MathVista.

In-depth insights#

Self-Evolving Multimodal Training#

Self-evolving multimodal training represents a significant advancement in artificial intelligence, aiming to enhance the reasoning capabilities of large multimodal models (LMMs). The core idea is to leverage the model’s own outputs to iteratively improve its performance, thereby reducing reliance on extensive, manually annotated datasets which are often scarce and expensive to create for multimodal tasks. This approach addresses the limitations of traditional supervised learning methods by enabling continuous learning and adaptation. Key challenges lie in designing effective reward mechanisms to guide the model’s self-improvement and strategies to manage the exploration-exploitation trade-off. Reward models play a critical role in evaluating the quality of the model’s generated reasoning steps, ensuring that the self-evolving process steers towards improvements in accuracy and logical soundness. Furthermore, careful consideration of prompt variation and training methodologies is crucial for ensuring both the robustness and efficiency of the self-evolving process. The success of self-evolving multimodal training hinges on the ability to create a feedback loop that effectively guides the model’s learning without leading to overfitting or instability. Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated reward models, exploring diverse training strategies, and rigorously evaluating the generalization capabilities of models trained using this paradigm.

M-STAR Framework#

The M-STAR framework, as described in the research paper, presents a novel approach to self-evolving training for multimodal reasoning. Its core innovation lies in the systematic investigation and optimization of three key factors: training method, reward model, and prompt variation. The framework doesn’t merely propose individual techniques but rather emphasizes a holistic approach, carefully examining the interplay between these elements. Continuous self-evolving training, which bridges the gap between iterative training and online RL, is a crucial component. The introduction of a process-based reward model (PRM) goes beyond simple binary rewards, capturing the quality of intermediate reasoning steps. Finally, the framework incorporates adaptive exploration strategies that dynamically adjust the model’s exploration-exploitation balance. This adaptive mechanism ensures the model’s continual improvement without sacrificing its ability to discover novel solutions and address unforeseen challenges. The overall goal is to create a universally effective method applicable to various model sizes and multimodal reasoning benchmarks, and the results demonstrate significant performance gains on several datasets, without needing additional human annotation, making it a compelling approach in the field.

Reward Model Impact#

The effectiveness of self-evolving training hinges significantly on the design of the reward model. A poorly designed reward model can lead to suboptimal learning, where the model fails to accurately assess the quality of its own reasoning steps and doesn’t prioritize improvement in critical areas. Sparse binary rewards, while simple to implement, often lack the richness needed to guide the model effectively. Therefore, the paper investigates richer reward models that take into account the intermediate steps in the reasoning process, providing more nuanced feedback. The impact of these process-based reward models is shown to be substantial, leading to improved performance compared to models trained with only sparse binary rewards. However, even sophisticated reward models can suffer limitations, especially when dealing with unseen data or unreliable evaluations. Careful design and tuning are crucial for reward models to effectively guide exploration and exploitation during self-evolving training, striking a balance between precision and diversity.

Unlabeled Data Challenges#

The use of unlabeled data presents significant challenges in self-evolving training for multimodal reasoning. The primary hurdle is the lack of ground truth to guide the learning process. Unlike supervised learning, where labeled data provides direct feedback, self-evolving models must rely on indirect signals (e.g., reward models, pseudo-labels) which may be noisy or unreliable, potentially hindering learning or even leading to catastrophic forgetting. Effective reward functions are crucial but difficult to design for complex multimodal tasks. A poorly designed reward can misguide the model, favoring suboptimal or nonsensical responses. Balancing exploration and exploitation becomes critical. The model needs to generate diverse outputs to explore the solution space but also needs to focus on refining high-quality answers. An insufficient exploration may lead to premature convergence to a suboptimal solution; however, excessive exploration wastes resources without providing substantial progress. Handling the inherent ambiguity and complexity of multimodal data adds another layer of difficulty. The model needs to integrate and reason effectively across different modalities (e.g., text, image, audio), which is inherently more challenging than single-modality reasoning. Ultimately, overcoming these challenges requires careful consideration of the reward model, the training algorithm, and the strategies used to manage exploration and exploitation.

Exploration-Exploitation Tradeoff#

The exploration-exploitation tradeoff is a central challenge in reinforcement learning, and this paper’s investigation into self-evolving training for multimodal reasoning highlights its significance. Self-evolving models must balance between exploring novel solution paths (exploration) and exploiting already-known successful strategies (exploitation). Initially, exploration is crucial to uncover diverse reasoning strategies and avoid premature convergence on suboptimal solutions. However, as training progresses, the model needs to shift towards exploitation to refine its most promising strategies and enhance performance on seen tasks. The paper proposes a method to dynamically adjust the exploration-exploitation balance through temperature control during training, preventing over-exploitation and maintaining sufficient exploration capacity. This dynamic approach is crucial to the success of the self-evolving training framework, allowing the model to adapt its search behavior throughout training and achieve improved reasoning capabilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

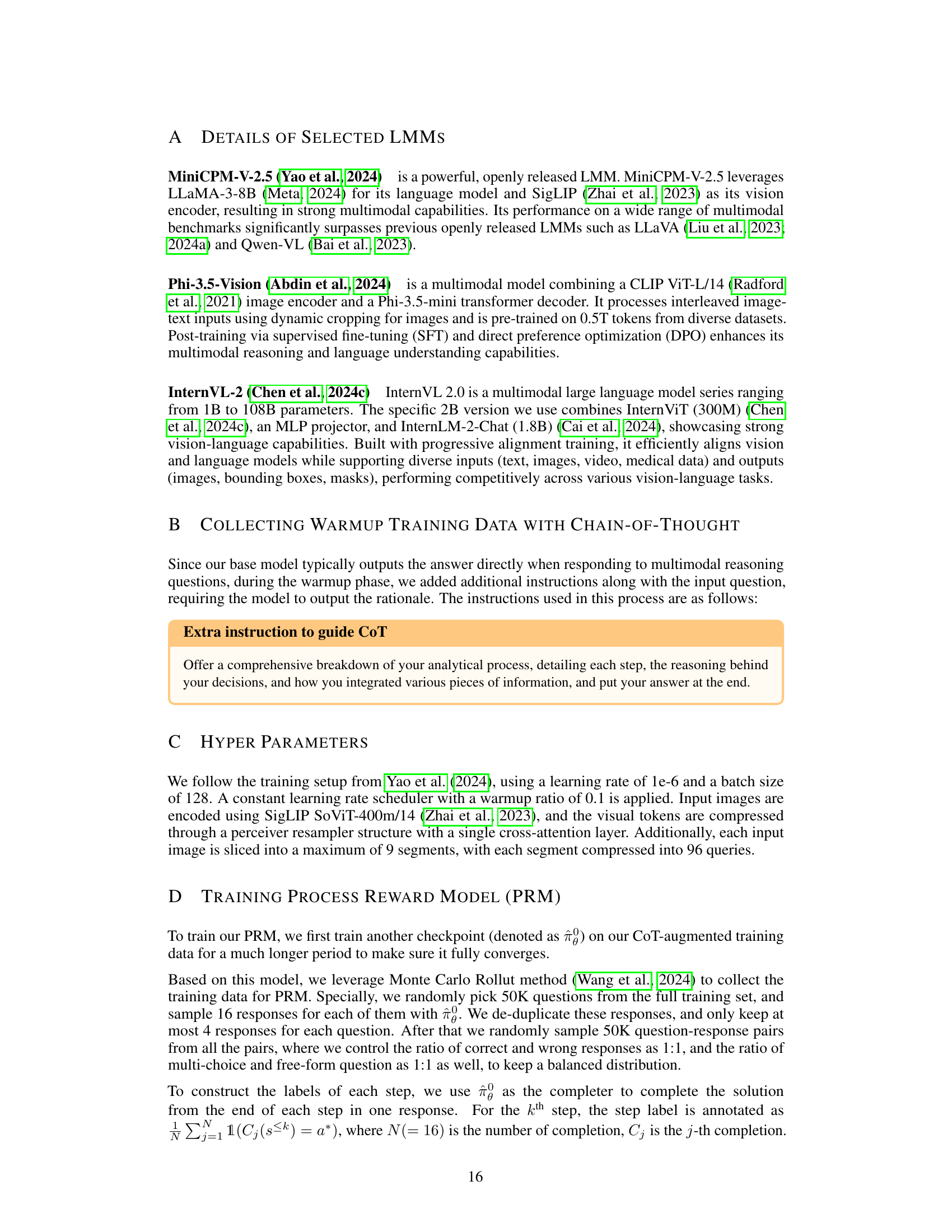

🔼 This figure shows the trend of Pass@K accuracy across different temperatures during the self-evolving training process. Pass@K represents the percentage of samples where at least one correct response is generated when sampling K candidates. The figure illustrates how the exploration ability of the model (Pass@K) changes at different temperatures (0.5, 0.7, 1.0, 1.2, 1.5, 1.7, 2.0) throughout the training process. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis represents the Pass@K accuracy. Different colored lines correspond to the different temperatures, showing how exploration varies at each temperature over the course of training.

read the caption

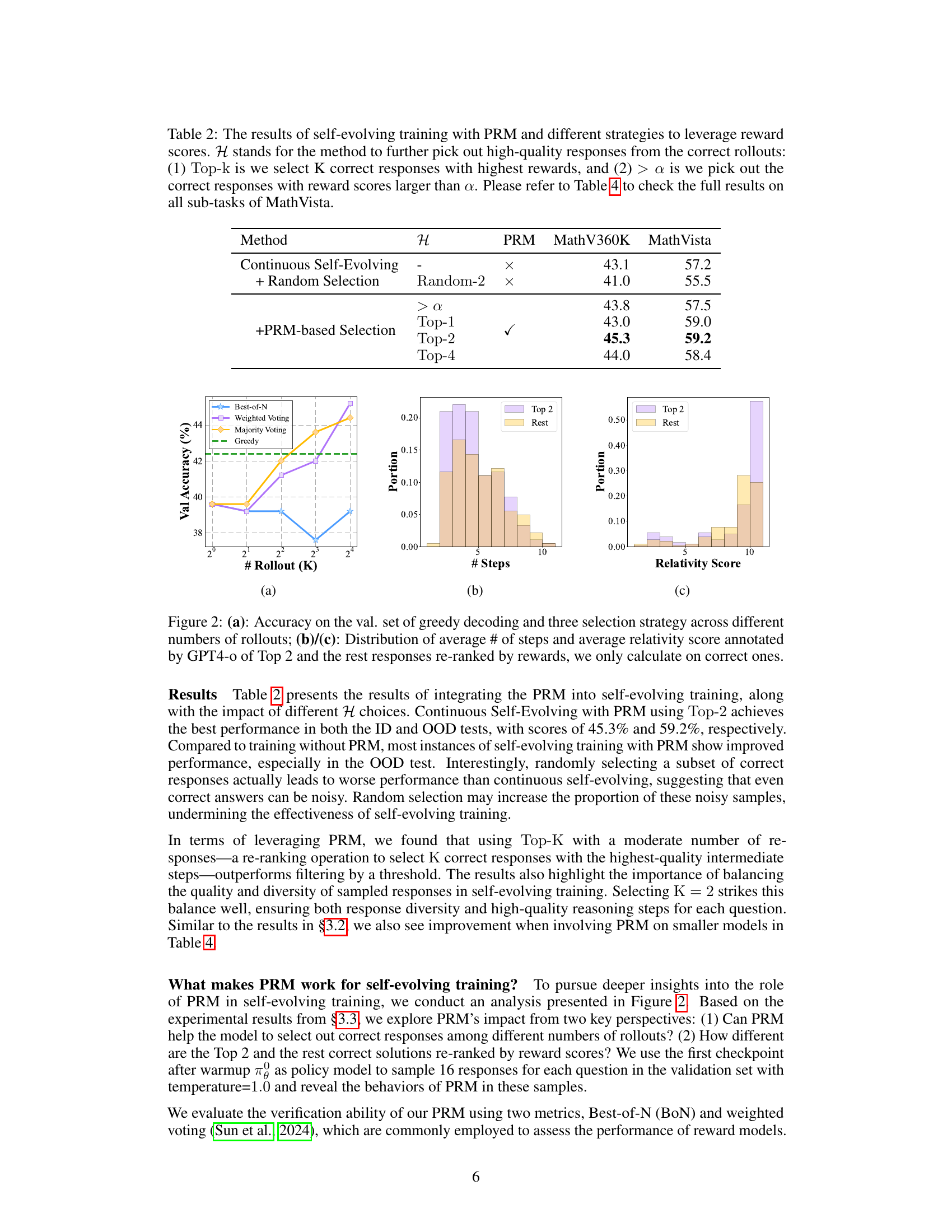

(a)

🔼 This histogram shows the distribution of the average number of reasoning steps in correct responses re-ranked by the reward model (PRM). The x-axis represents the number of steps, and the y-axis represents the frequency or count of responses with that many steps. The distribution is compared for the top 2 responses selected by the PRM and for the rest of the correct responses, highlighting the difference in the complexity of reasoning between the PRM’s top choices and other correct responses. The PRM tends to select responses with a fewer number of steps, implying that the model is prioritizing more concise reasoning paths.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 The figure shows the distribution of the relativity scores for the top 2 responses (selected by the PRM) and the rest of the correct responses. The relativity score, annotated by GPT-4, measures how directly relevant a response is to the given question. The x-axis represents the relativity score (ranging from 0 to 10), and the y-axis shows the frequency/proportion of responses with that score. The figure illustrates that responses selected by the PRM tend to have higher relativity scores, meaning they are more directly related to the question and contain fewer irrelevant steps, demonstrating the effectiveness of the PRM in selecting high-quality responses.

read the caption

(c)

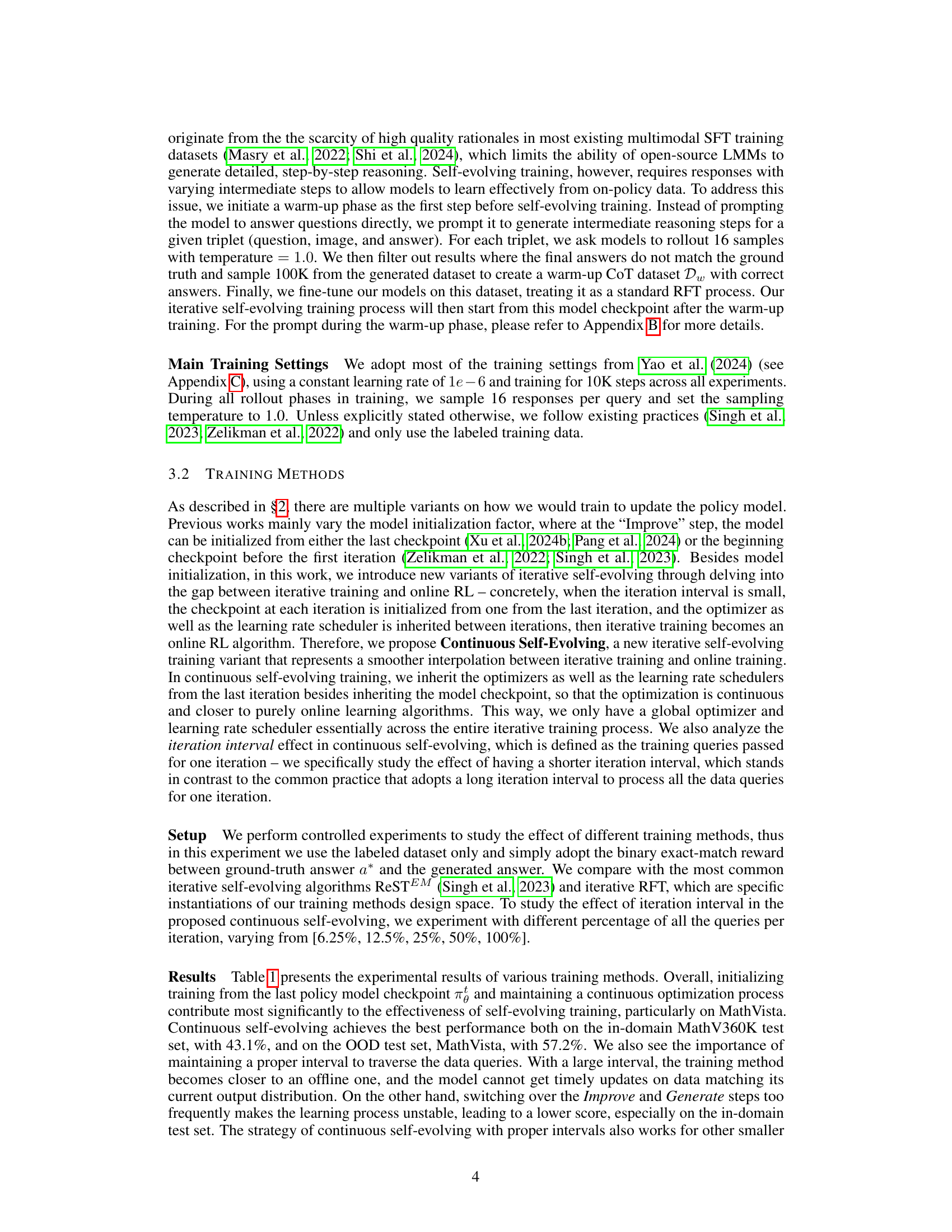

🔼 This figure analyzes the impact of using a process reward model (PRM) on selecting high-quality responses in a self-evolving training framework. Panel (a) shows how the validation accuracy of greedy decoding changes with different numbers of response rollouts (K) and three different selection strategies (Top-K, Random Selection, and PRM-based selection). Panels (b) and (c) provide further insight into the characteristics of the top-2 responses selected by the PRM compared to the rest of the correct responses. Panel (b) displays the distribution of the average number of reasoning steps, while panel (c) shows the distribution of the average relativity score (as annotated by GPT-4) for these responses. The relativity score indicates how directly related each response is to the original question. Only correct responses are included in the analysis of panels (b) and (c).

read the caption

Figure 2: (a): Accuracy on the val. set of greedy decoding and three selection strategy across different numbers of rollouts; (b)/(c): Distribution of average # of steps and average relativity score annotated by GPT4-o of Top 2 and the rest responses re-ranked by rewards, we only calculate on correct ones.

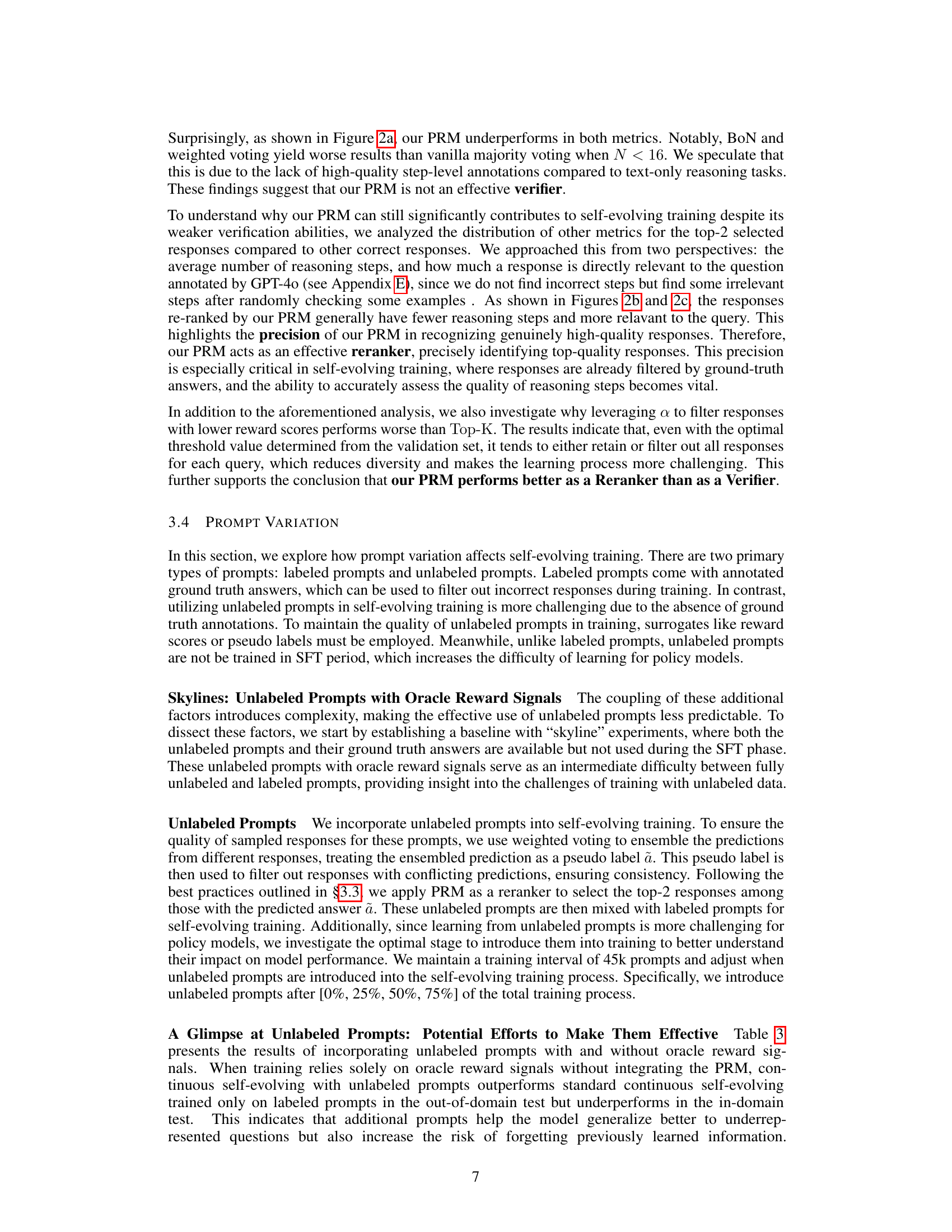

🔼 This figure shows two line graphs plotting the validation accuracy over training steps. The blue line represents the greedy decoding accuracy, showing a consistent increase in performance as training progresses. The orange line shows the Pass@K accuracy, which displays an opposite trend. Pass@K measures the model’s ability to find at least one correct answer among K samples. The decreasing trend indicates a loss of exploration capability during training, which could limit the model’s potential for improvement and lead to performance saturation. This contrast highlights the trade-off between exploitation (greedy decoding) and exploration (Pass@K) during self-evolving training, where initially high exploration is gradually lost in favor of increased exploitation as training progresses.

read the caption

Figure 3: The opposite trend of Greedy Decoding Accuracy and Pass@K.

🔼 This figure shows the trend of Pass@K metric during the self-evolving training process with different temperatures. Pass@K represents the percentage of samples for which the model generates at least one correct response when sampling K candidates. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis shows the Pass@K accuracy. Different colored lines represent different temperatures used during the generation process. The figure reveals the impact of temperature on the model’s exploration ability and how it changes over the training process. Higher temperatures generally maintain better exploration abilities during later training stages, as indicated by slower decreases in Pass@K compared to lower temperatures.

read the caption

(a)

🔼 This histogram shows the distribution of the number of reasoning steps in correct responses, categorized into two groups: those re-ranked to the top 2 by the process reward model (PRM) and the rest. The PRM’s ability to select responses with fewer steps, indicating a more focused and efficient reasoning process, is highlighted.

read the caption

(b)

🔼 The figure shows the distribution of the relativity score of the top 2 responses re-ranked by rewards and other correct responses annotated by GPT-4. The relativity score measures how directly related a response is to the question. This analysis helps to understand why the process reward model (PRM) improves the quality of the responses, even though the PRM itself isn’t a strong verifier of response correctness.

read the caption

(c)

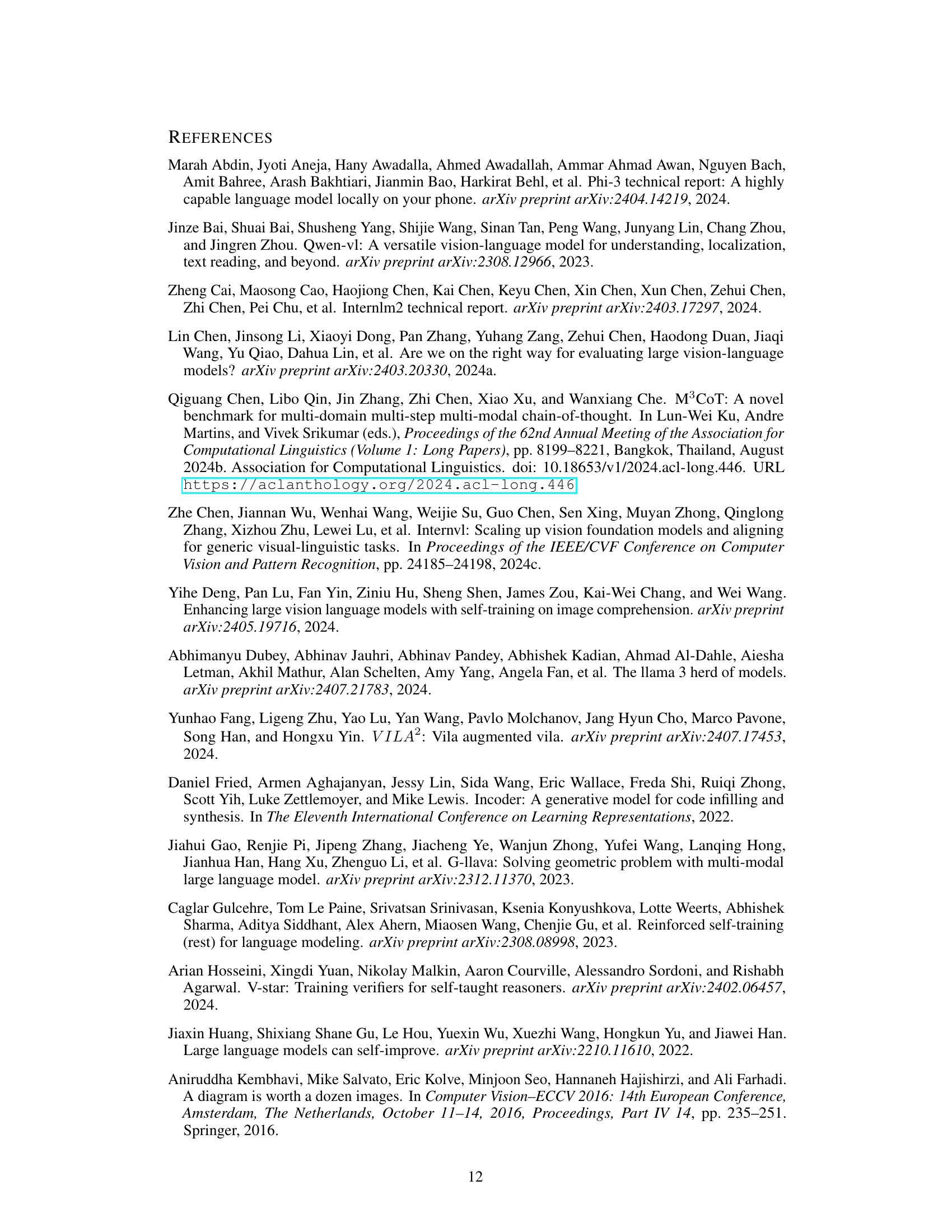

🔼 Figure 4 presents a detailed analysis of the training dynamics of a multimodal self-evolving model. It displays three key metrics over the course of training: (a) Pass@K, which measures the model’s ability to generate at least one correct answer among K samples at various temperatures, demonstrating a decline in exploration capability as training progresses; (b) the difference between Pass@K and Greedy decoding accuracy, highlighting the diminishing exploration-exploitation trade-off; and (c) Reward-Pass@2, showcasing the rapid saturation of the reward model’s ability to identify high-quality responses. All metrics are calculated on a held-out validation set to ensure unbiased evaluation of the model’s performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a): Pass@K decreases for all different temperatures; (b): The gap between Pass@K and Greedy Decoding; (c): The Reward-Pass@2 saturates quickly. All metrics, including the greedy decoding accuracy, are calculated on validation set.

🔼 Figure 5 presents a comparison of the performance of two training strategies: one using a dynamic temperature adjustment, and another using a fixed temperature (T=1.0). The figure displays the smoothed trends of two key metrics: Pass@K (measuring the model’s exploration ability) and Reward-Pass@2 (measuring the exploitation efficacy of the reward model). The dynamic strategy aims to balance exploration and exploitation by adapting the temperature based on performance, while the static approach maintains a constant temperature throughout the training process. By comparing the curves of these metrics under both strategies, the figure illustrates the effects of adaptive temperature tuning on exploration and exploitation in self-evolving training.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparing the smoothed Pass@K and Reward-Pass@2 curves with the optimal static training progress, which fixs T=1.0𝑇1.0T=1.0italic_T = 1.0.

More on tables

| mathcal{H} | PRM | MathV360K | MathVista | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Self-Evolving | - | × | 43.1 | 57.2 |

| + Random Selection | Random-2 | × | 41.0 | 55.5 |

| +PRM-based Selection | ✓ | |||

| >α | 43.8 | 57.5 | ||

| Top-1 | 43.0 | 59.0 | ||

| Top-2 | 45.3 | 59.2 | ||

| Top-4 | 44.0 | 58.4 |

🔼 Table 2 presents the results of experiments using different methods to leverage reward scores within a process reward model (PRM) for self-evolving training. The table compares the performance of self-evolving training with PRM, using two different strategies to select high-quality responses from the correct rollouts. The first strategy selects the top k responses with the highest reward scores (Top-k), while the second strategy selects all responses with reward scores above a certain threshold (> α). The table shows the performance metrics (MathV360K and MathVista) for each method and helps to determine the best strategy for utilizing the PRM in self-evolving training. More detailed results broken down by subtask are available in Table 4.

read the caption

Table 2: The results of self-evolving training with PRM and different strategies to leverage reward scores. ℋℋ\mathcal{H}caligraphic_H stands for the method to further pick out high-quality responses from the correct rollouts: (1) Top−kTopk\operatorname{Top-k}roman_Top - roman_k is we select K correct responses with highest rewards, and (2) >αabsent𝛼>\alpha> italic_α is we pick out the correct responses with reward scores larger than α𝛼\alphaitalic_α. Please refer to Table 4 to check the full results on all sub-tasks of MathVista.

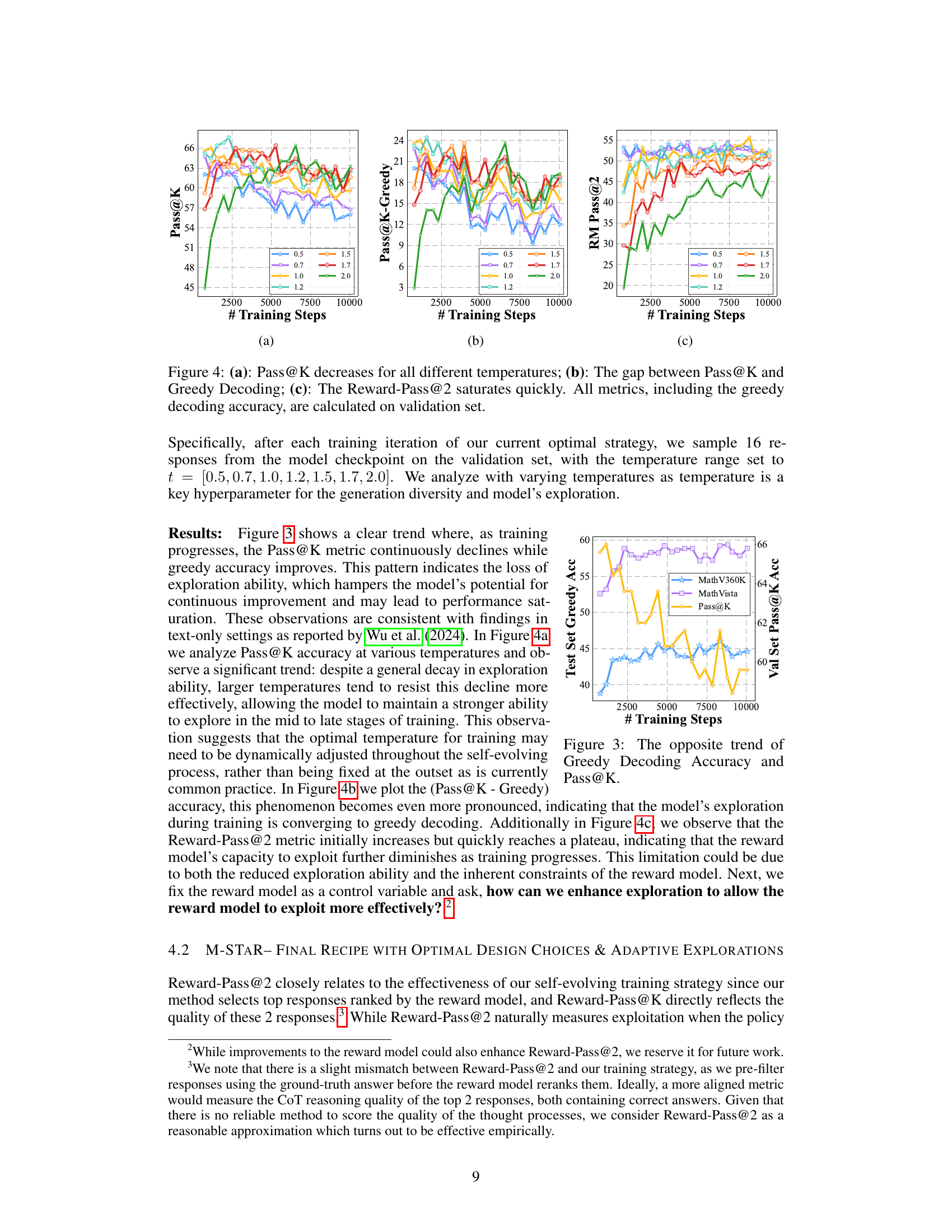

| Oracle | PRM | Tmixin | MathV360K | MathVista |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | × | - | 43.1 | 57.2 |

| - | ✓ | - | 45.3 | 59.2 |

| ✓ | × | 0% | 42.5 | 58.2 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 0% | 42.9 | 59.1 |

| × | ✓ | 0% | 43.3 | 58.2 |

| × | ✓ | 25% | 42.4 | 57.6 |

| × | ✓ | 50% | 42.9 | 58.2 |

| × | ✓ | 75% | 45.0 | 58.8 |

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments investigating the impact of incorporating unlabeled data into the self-evolving training process. It explores different strategies for mixing labeled and unlabeled data at various stages of training. The ‘Tmixin’ column indicates the percentage of training completed before unlabeled data is introduced. The use of a Process Reward Model (PRM) is consistent with the method described in section 3.3 of the paper, but a ‘pseudo ground truth’ is obtained using a weighted voting scheme for the unlabeled prompts. The table shows the performance in terms of accuracy on MathV360K and MathVista datasets for several configurations, enabling analysis of the effects of different timing for unlabeled data introduction, with and without the PRM.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of involving unlabeled data. Tmixinsubscript𝑇mixinT_{\texttt{mixin}}italic_T start_POSTSUBSCRIPT mixin end_POSTSUBSCRIPT denotes when to mixin the unlabeled data. The use of PRM follows §3.3, except we first get a pesudo “ground truth” through weighted voting on unlabeled prompts.

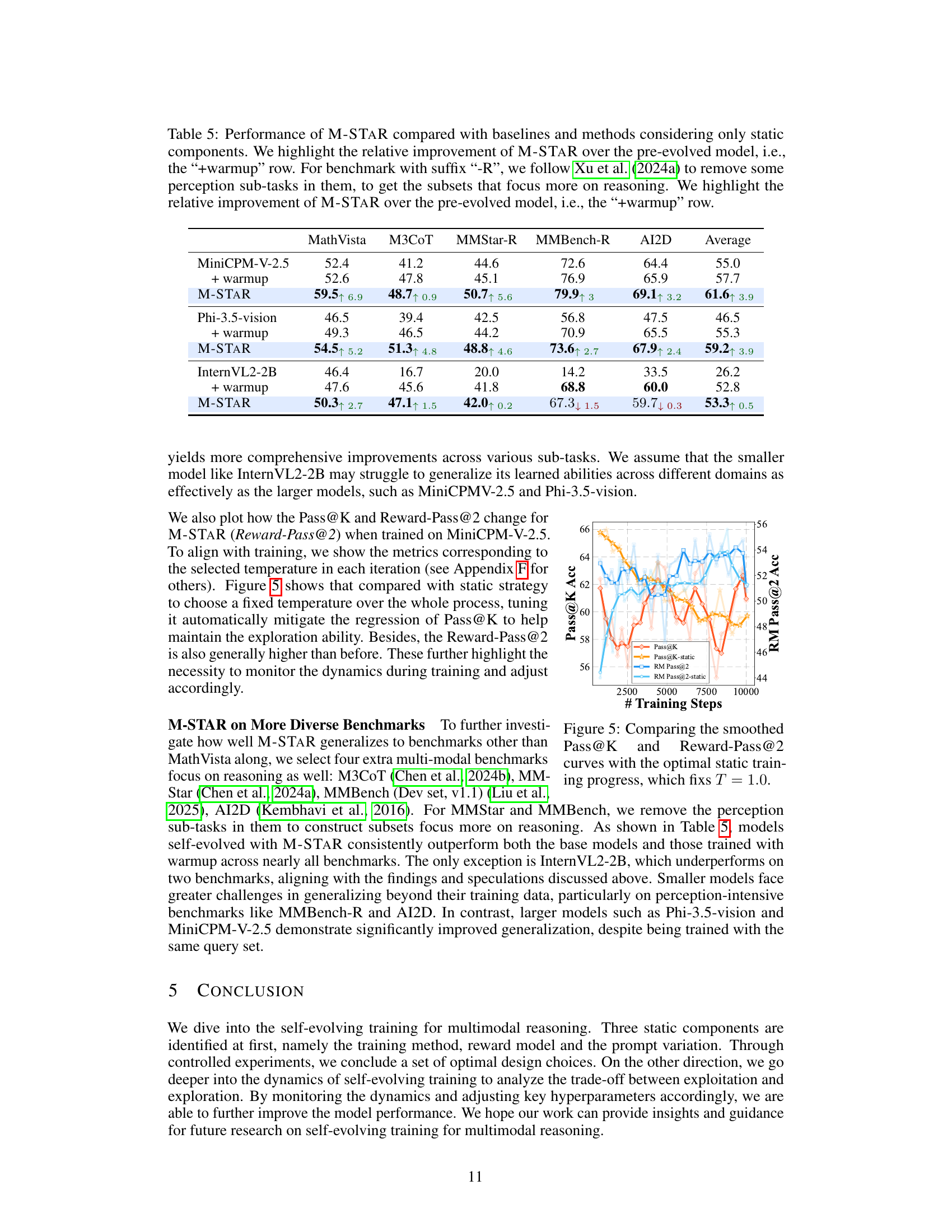

| MathVista | M3CoT | MMStar-R | MMBench-R | AI2D | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiniCPM-V-2.5 | 52.4 | 41.2 | 44.6 | 72.6 | 64.4 | 55.0 |

| + warmup | 52.6 | 47.8 | 45.1 | 76.9 | 65.9 | 57.7 |

| M-STaR | 59.5↑ 6.9 | 48.7↑ 0.9 | 50.7↑ 5.6 | 79.9↑ 3 | 69.1↑ 3.2 | 61.6↑ 3.9 |

| Phi-3.5-vision | 46.5 | 39.4 | 42.5 | 56.8 | 47.5 | 46.5 |

| + warmup | 49.3 | 46.5 | 44.2 | 70.9 | 65.5 | 55.3 |

| M-STaR | 54.5↑ 5.2 | 51.3↑ 4.8 | 48.8↑ 4.6 | 73.6↑ 2.7 | 67.9↑ 2.4 | 59.2↑ 3.9 |

| InternVL2-2B | 46.4 | 16.7 | 20.0 | 14.2 | 33.5 | 26.2 |

| + warmup | 47.6 | 45.6 | 41.8 | 68.8 | 60.0 | 52.8 |

| M-STaR | 50.3↑ 2.7 | 47.1↑ 1.5 | 42.0↑ 0.2 | 67.3↓ 1.5 | 59.7↓ 0.3 | 53.3↑ 0.5 |

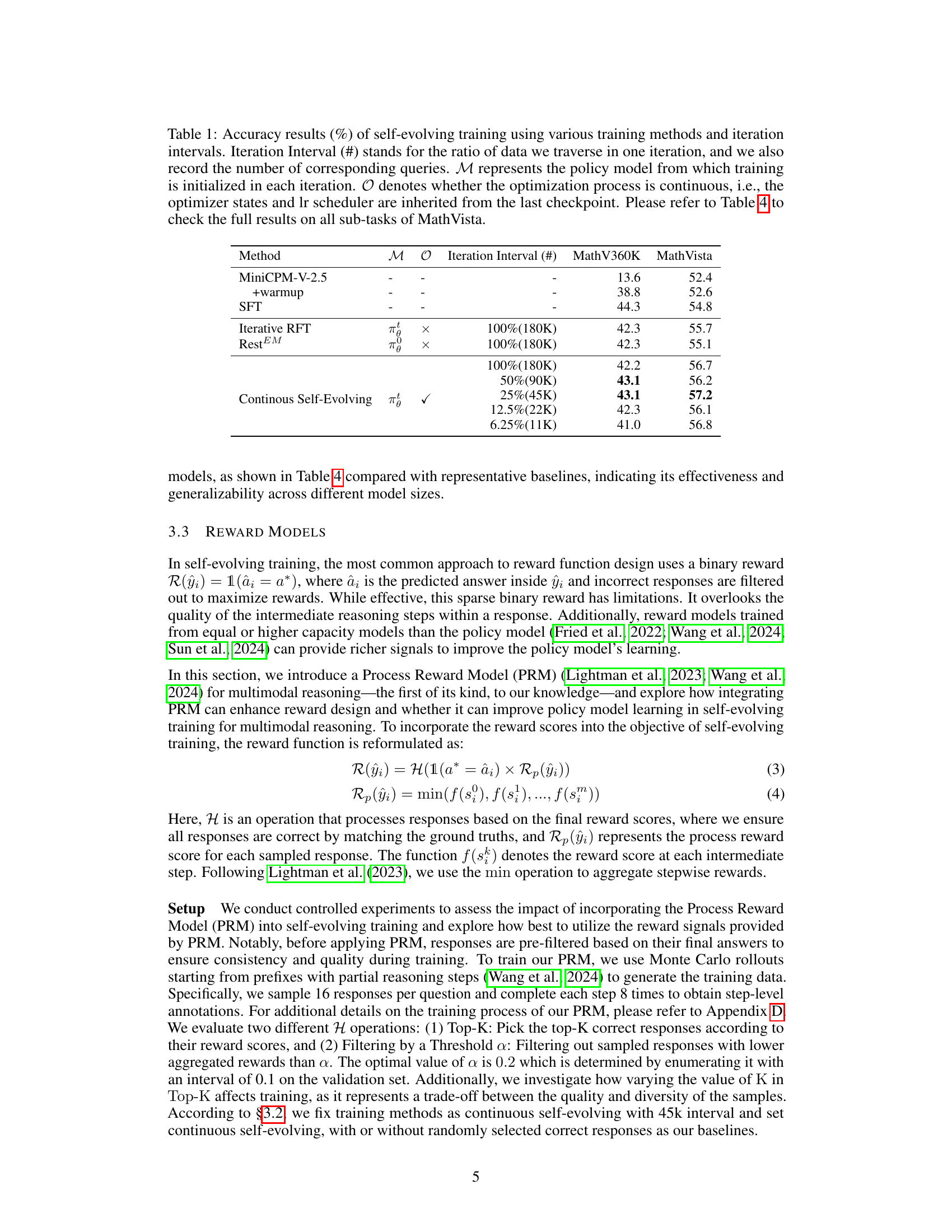

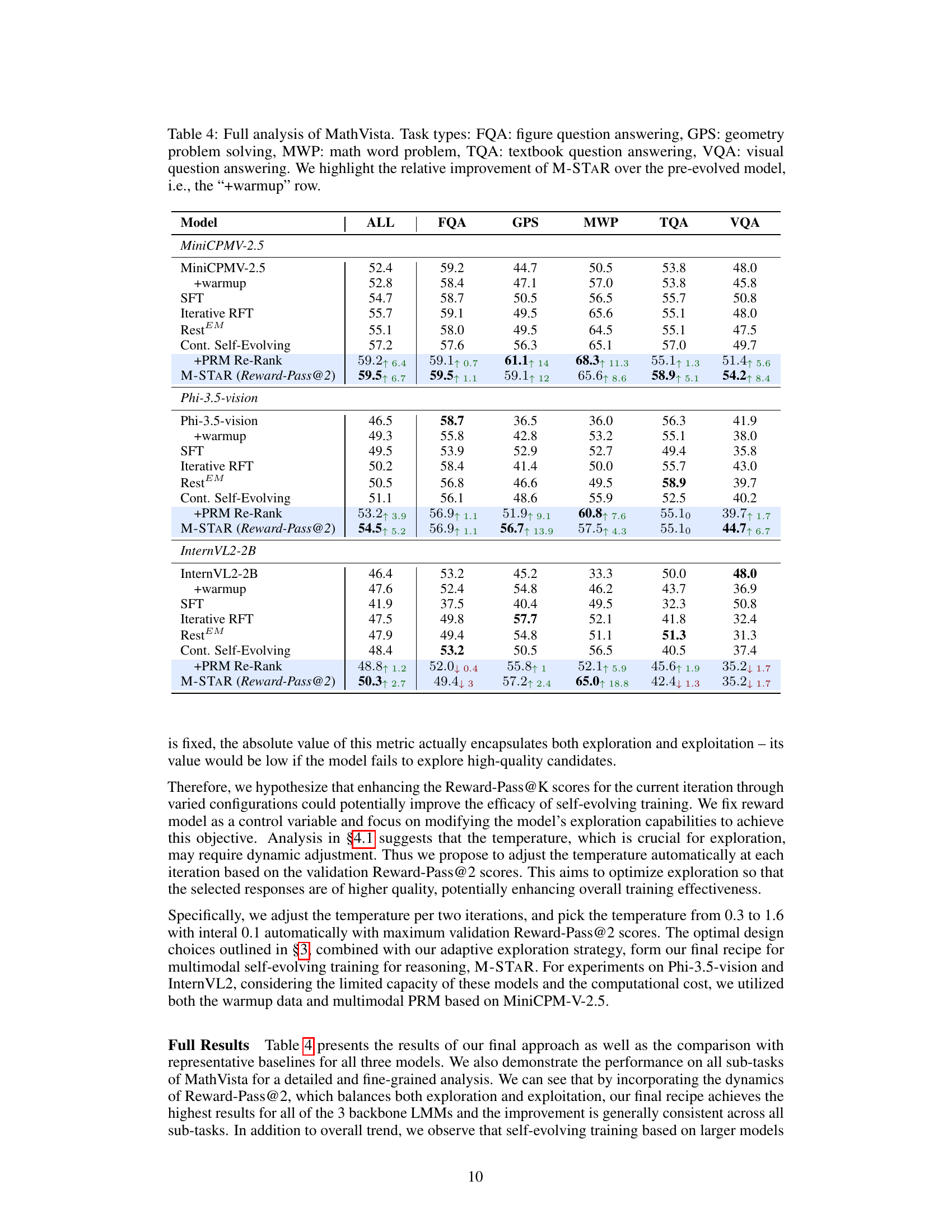

🔼 Table 4 presents a comprehensive breakdown of the MathVista benchmark results, categorized by task type: Figure Question Answering (FQA), Geometry Problem Solving (GPS), Math Word Problem (MWP), Textbook Question Answering (TQA), and Visual Question Answering (VQA). The table compares the performance of several models, including a baseline model (+warmup) which has undergone a warm-up phase, various self-evolving training methods, and finally the proposed M-STaR model. The key focus is on illustrating the significant performance gains achieved by M-STaR relative to the pre-evolved model (+warmup) across all task types within MathVista, demonstrating its robustness and effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 4: Full analysis of MathVista. Task types: FQA: figure question answering, GPS: geometry problem solving, MWP: math word problem, TQA: textbook question answering, VQA: visual question answering. We highlight the relative improvement of M-STaR over the pre-evolved model, i.e., the “+warmup” row.

Full paper#