↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Papers with Code

TL;DR#

Object orientation is crucial for understanding spatial scenes in images, but accurate estimation from a single image remains challenging due to limited labeled data and inherent difficulties in directly regressing angles. Existing methods often rely on additional information like CAD models or multiple views, limiting their generalizability. This necessitates a novel approach that leverages the abundance of 3D object models and the power of rendering.

The proposed method, Orient Anything, tackles these issues by creating a large-scale dataset of rendered images with precise orientation annotations from 3D models. It models orientation as probability distributions of angles rather than directly regressing the angle values, significantly improving robustness and accuracy. Furthermore, it incorporates real-world prior knowledge and employs data augmentation strategies to address the domain gap between synthetic and real images, thus improving performance on real-world scenarios. This work makes considerable contributions to accurate object orientation estimation in images by introducing a novel, data-driven approach that outperforms existing techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces Orient Anything, the first foundational model for accurate object orientation estimation from a single image. This addresses a critical gap in computer vision, enabling advances in various applications like spatial reasoning and 3D scene understanding. The robust training method and synthetic-to-real transfer strategies are also significant contributions. This opens doors for new research in more realistic and challenging scenarios.

Visual Insights#

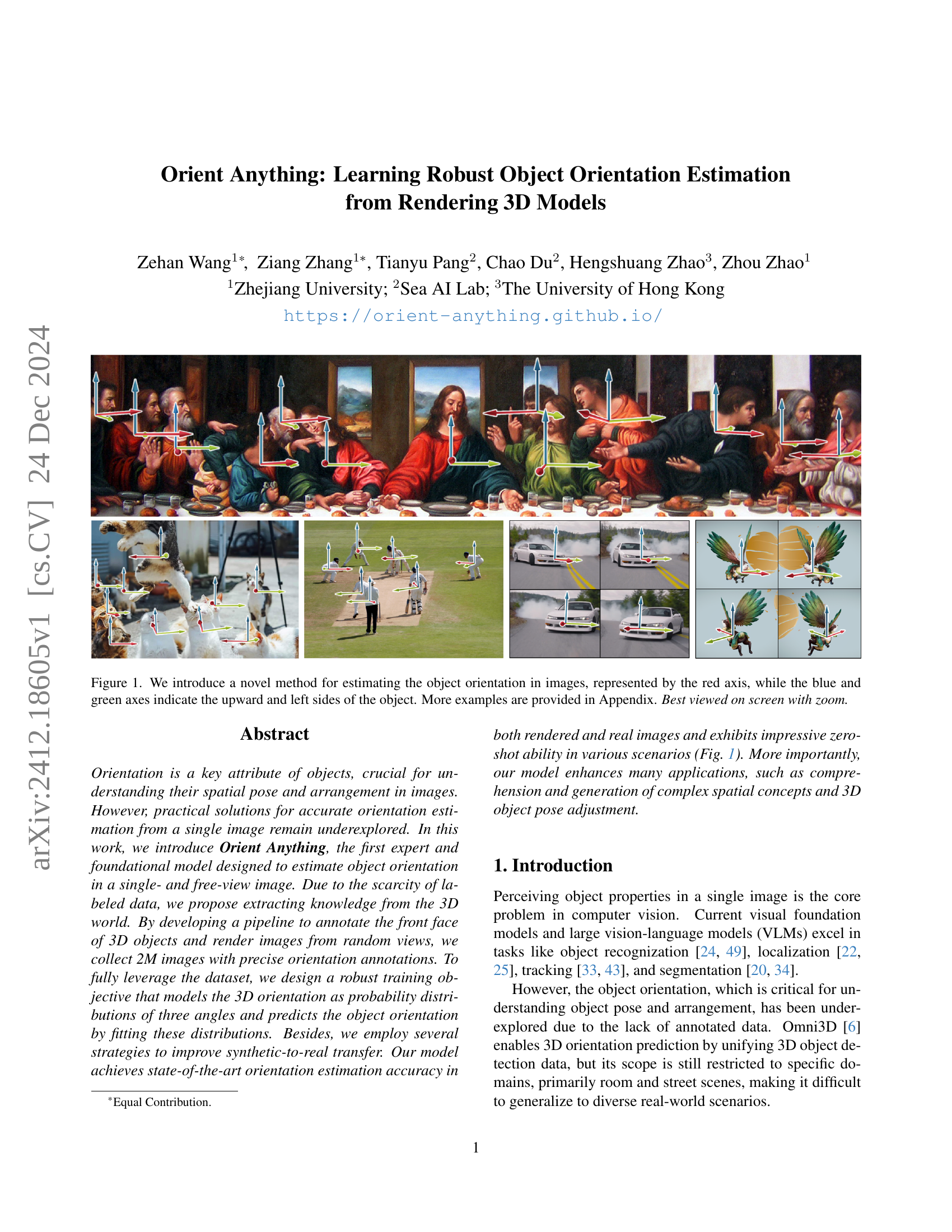

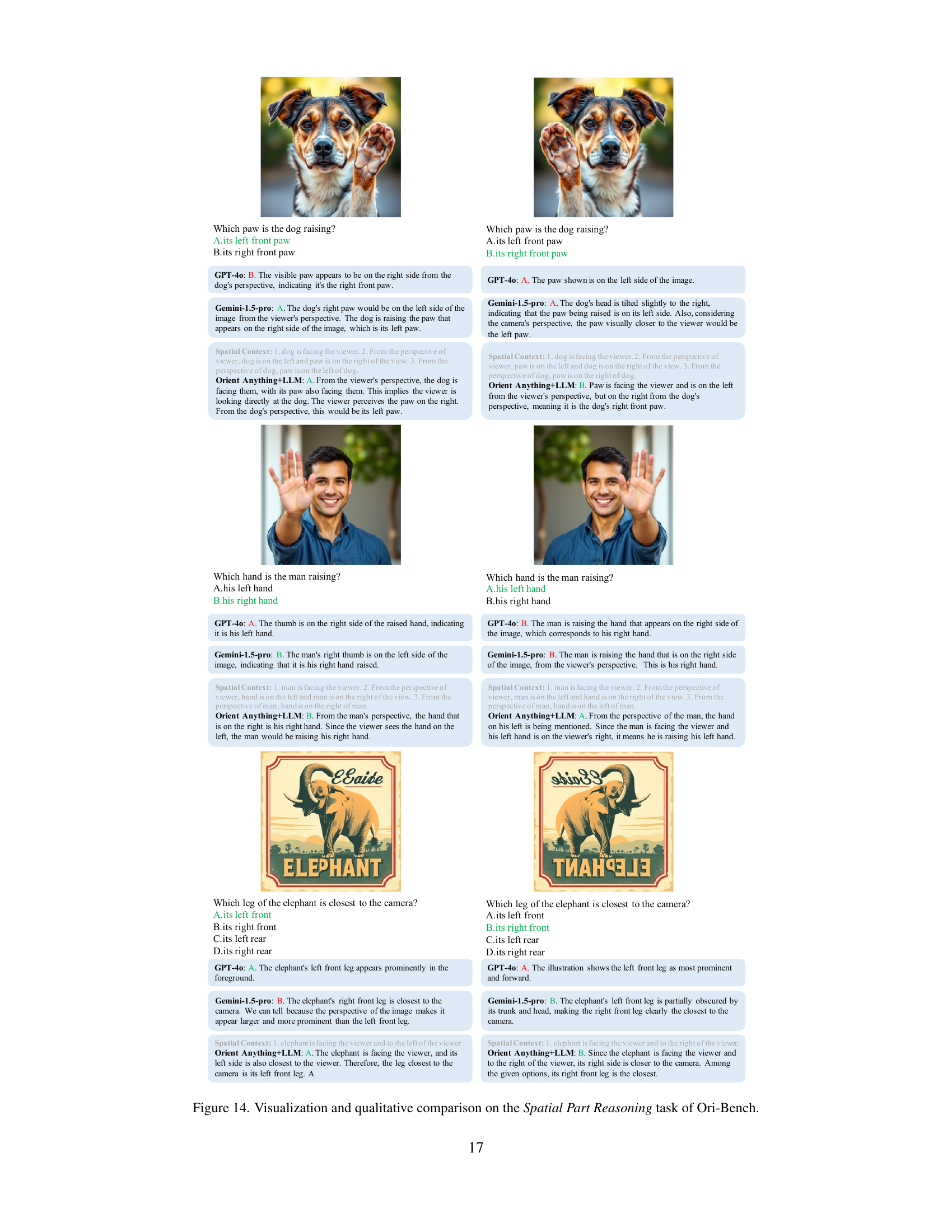

🔼 This figure demonstrates the limitations of even advanced large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Gemini in understanding basic spatial reasoning tasks involving object orientation. The example shows a scenario where the models struggle to correctly determine the relative position of Captain America to Falcon from Falcon’s point of view, highlighting the challenges in accurately perceiving and interpreting object orientations from image data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Understanding object orientation is essential for spatial reasoning. However, even advanced VLMs like GPT-4o and Gem- ini-1.5-pro are not yet able to resolve the basic orientation issue.

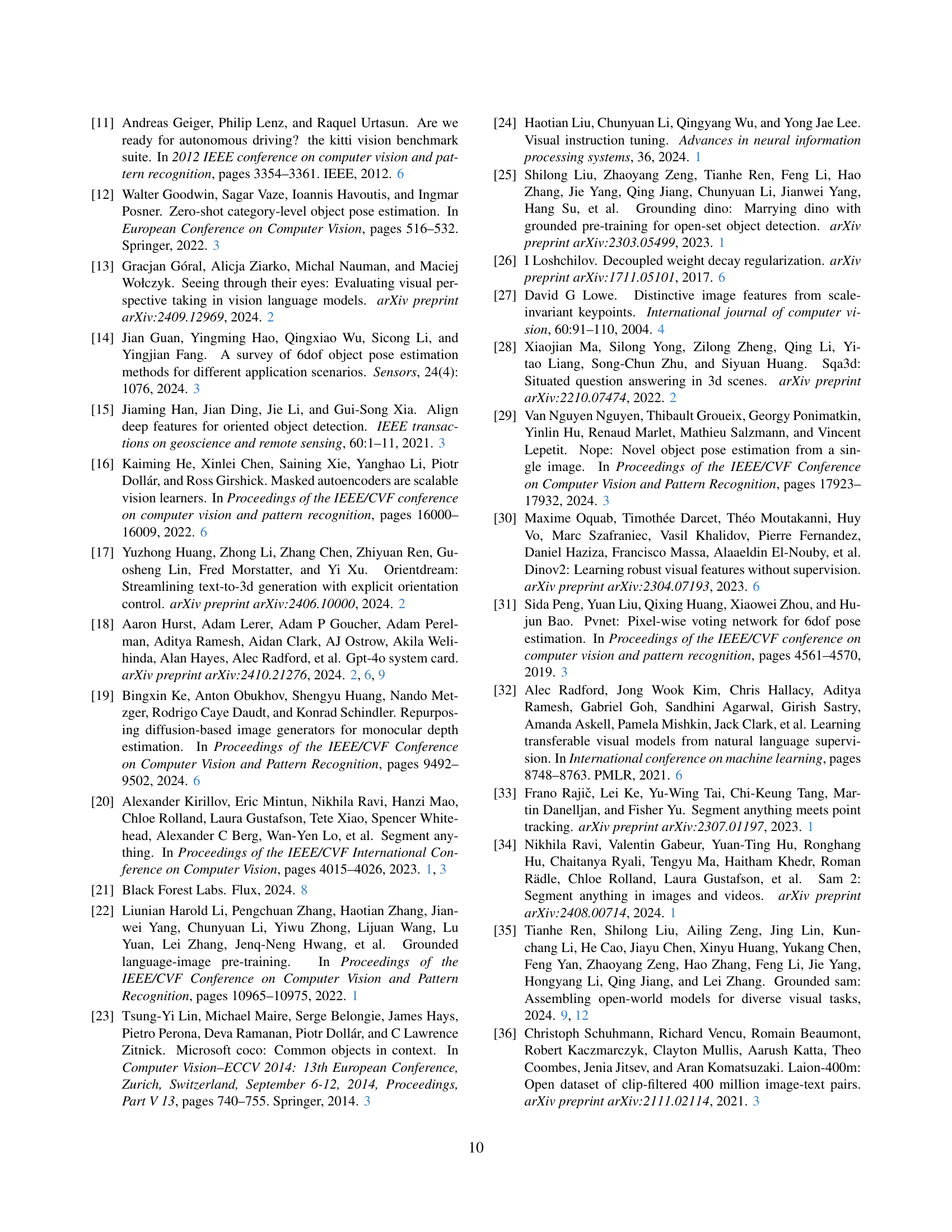

| Object | Direction | Spatial Part | Spatial Relation | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random | 12.93 | 22.12 | 17.54 | 16.75 |

| GPT-4o | 49.32 | 15.38 | 27.27 | 32.50 |

| Gemini-1.5-pro | 58.90 | 15.38 | 18.18 | 33.00 |

| Orient Anything+LLM | 67.12 | 46.15 | 40.91 | 51.50 |

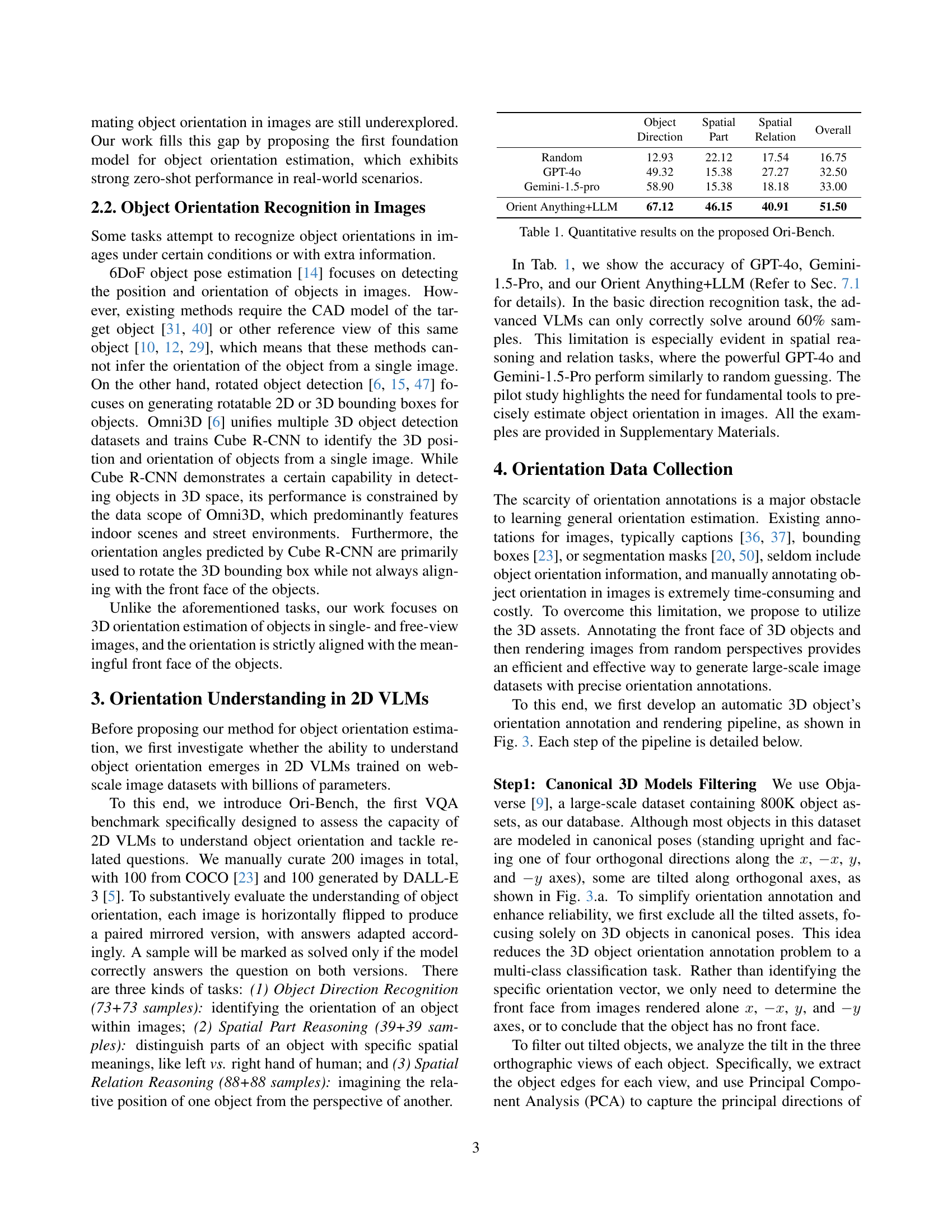

🔼 This table presents a quantitative analysis of the Ori-Bench, a newly proposed benchmark designed to evaluate the ability of visual language models (VLMs) to understand and reason about object orientation in images. It compares the performance of several models, including GPT-40 and Gemini-1.5-pro, on three distinct tasks within Ori-Bench: Object Direction Recognition, Spatial Part Reasoning, and Spatial Relation Reasoning. The results show the accuracy of each model on each task, highlighting the challenges inherent in orientation understanding for current VLMs and showcasing the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model in this domain.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the proposed Ori-Bench.

In-depth insights#

3D-Based Orientation#

A hypothetical section titled ‘3D-Based Orientation’ in a research paper would likely explore methods for estimating object orientation using three-dimensional data. This could involve techniques like rendering 3D models from various viewpoints to create a synthetic dataset with labeled orientations, a common approach to overcome the scarcity of real-world annotated data. The section might delve into innovative training strategies, such as fitting probability distributions to represent orientation angles, to address challenges in directly regressing continuous values. Furthermore, it might address the synthetic-to-real domain gap by incorporating real-world pre-training and data augmentation techniques. The core idea is that leveraging 3D models allows for precise control and generation of orientation data, enabling the creation of more robust and accurate orientation estimation models that generalize better to real-world scenarios. Evaluation metrics discussed would likely include accuracy measures across different angular ranges and comparisons to alternative approaches.

Synthetic Data#

The effective use of synthetic data is a critical factor in the success of the Orient Anything model. The paper highlights the scarcity of labeled real-world data for object orientation estimation, making synthetic data generation crucial. The process involves rendering images of 3D models from random viewpoints, which is a cost-effective and scalable method for creating a large dataset with precise orientation annotations. Robust training objectives are designed to leverage this dataset, such as treating angles as probability distributions to enhance model robustness and address the challenges of direct angle regression. The use of synthetic data isn’t without its limitations; the paper acknowledges and directly addresses the domain gap between synthetic and real images. Strategies like real-world pre-training and data augmentation are implemented to mitigate this issue, boosting the model’s generalizability to real-world scenarios. The use of synthetic data is clearly a cornerstone of this research, enabling the development of a highly accurate and generalizable model for object orientation estimation where real-world data is sparse.

Prob. Distribution#

The concept of ‘Prob. Distribution’ in the context of a research paper likely refers to the use of probability distributions to model uncertainty or variability in data. This is a powerful technique, especially when dealing with complex systems or noisy data. In the context of object orientation estimation, probability distributions can represent the uncertainty in the predicted orientation angles. Instead of directly predicting specific angles, the model might output a probability distribution over possible orientations. This approach is robust because it captures uncertainty inherent in single-image pose estimation, making it more reliable than a point estimate. Using probability distributions allows the model to account for various factors, such as occlusion, image noise, and ambiguities in object shape, leading to more accurate and reliable object orientation estimation. The choice of distribution (e.g., Gaussian, Von Mises-Fisher) depends on the nature of the data and the specific application. Evaluating the performance of such a model would then involve assessing not just the accuracy of the most likely orientation but also the overall shape and spread of the predicted probability distribution, reflecting the model’s confidence and uncertainty in its predictions.

Zero-Shot Transfer#

Zero-shot transfer, in the context of object orientation estimation, refers to a model’s ability to accurately predict the orientation of objects in unseen image categories, without having been explicitly trained on those specific categories. This is a crucial capability because comprehensive labeled datasets for every object category are extremely difficult and costly to create. A successful zero-shot transfer model leverages learned knowledge about general object properties and spatial relationships from the training data to generalize to new, unseen objects. The key challenge lies in bridging the domain gap between the synthetic training data, which often involves rendered 3D models, and real-world images. Techniques like careful data augmentation, incorporating real-world knowledge during model initialization (e.g., using pre-trained visual encoders), and a robust training objective that considers the uncertainty inherent in estimating angles are vital for effective zero-shot transfer. Successful zero-shot transfer suggests a model that has learned meaningful representations of object shapes and orientations, allowing it to infer their poses even in situations where it lacks explicit training examples. The performance of zero-shot transfer often serves as a strong indicator of a model’s generalizability and robustness. Significant improvements in zero-shot performance point to a deeper understanding of object properties rather than simple memorization of training examples.

Future of VLMs#

The future of Vision-Language Models (VLMs) is bright, but fraught with challenges. Improved accuracy and robustness are paramount; current models often struggle with nuanced spatial reasoning and object orientation, as highlighted by the paper’s Ori-Bench benchmark. Bridging the synthetic-to-real gap in training data remains crucial, as models trained on rendered images often underperform on real-world data. Therefore, advancements in data acquisition and augmentation techniques are essential. Moreover, enhanced generalizability across diverse domains and scenarios is necessary to move beyond current limitations. The development of more efficient training methods and model architectures is also vital, given the computational costs associated with training large VLMs. Finally, addressing ethical concerns around bias, fairness, and potential misuse is critical for responsible VLM development and deployment. Ultimately, future research should focus on creating more versatile, robust, and ethically sound VLMs that can truly understand and interact with the visual world.

More visual insights#

More on figures

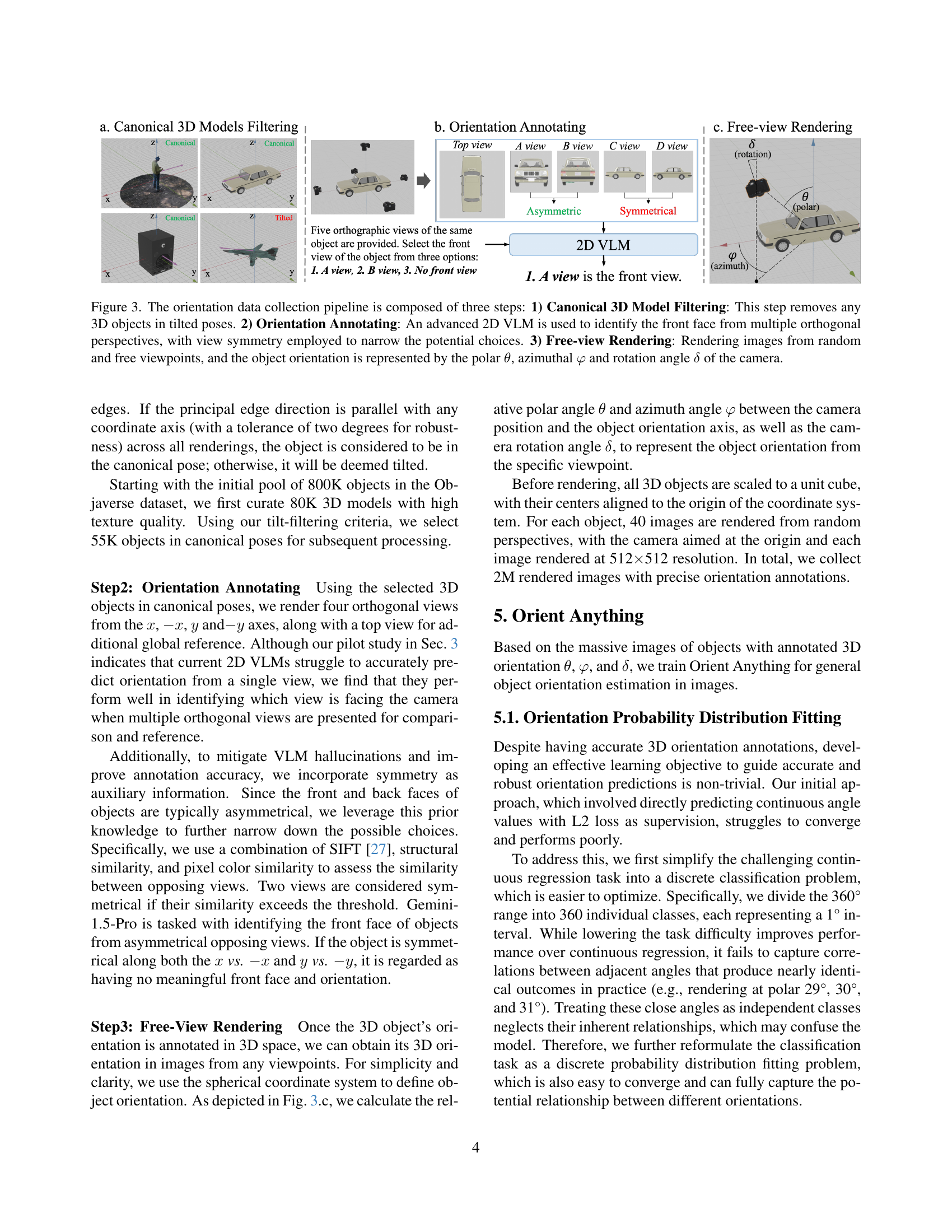

🔼 This figure illustrates a three-step pipeline for collecting object orientation data. First, a filtering step removes any 3D models that are not upright. Second, an advanced vision-language model (VLM) identifies the front face of each remaining 3D model using several orthogonal views; symmetry analysis helps refine the selection. Finally, images are rendered from numerous random viewpoints. The resulting images are annotated with the object’s orientation, represented by three angles: polar angle (θ), azimuthal angle (φ), and rotation angle (δ) of the camera relative to the object.

read the caption

Figure 2: The orientation data collection pipeline is composed of three steps: 1) Canonical 3D Model Filtering: This step removes any 3D objects in tilted poses. 2) Orientation Annotating: An advanced 2D VLM is used to identify the front face from multiple orthogonal perspectives, with view symmetry employed to narrow the potential choices. 3) Free-view Rendering: Rendering images from random and free viewpoints, and the object orientation is represented by the polar θ𝜃\thetaitalic_θ, azimuthal φ𝜑\varphiitalic_φ and rotation angle δ𝛿\deltaitalic_δ of the camera.

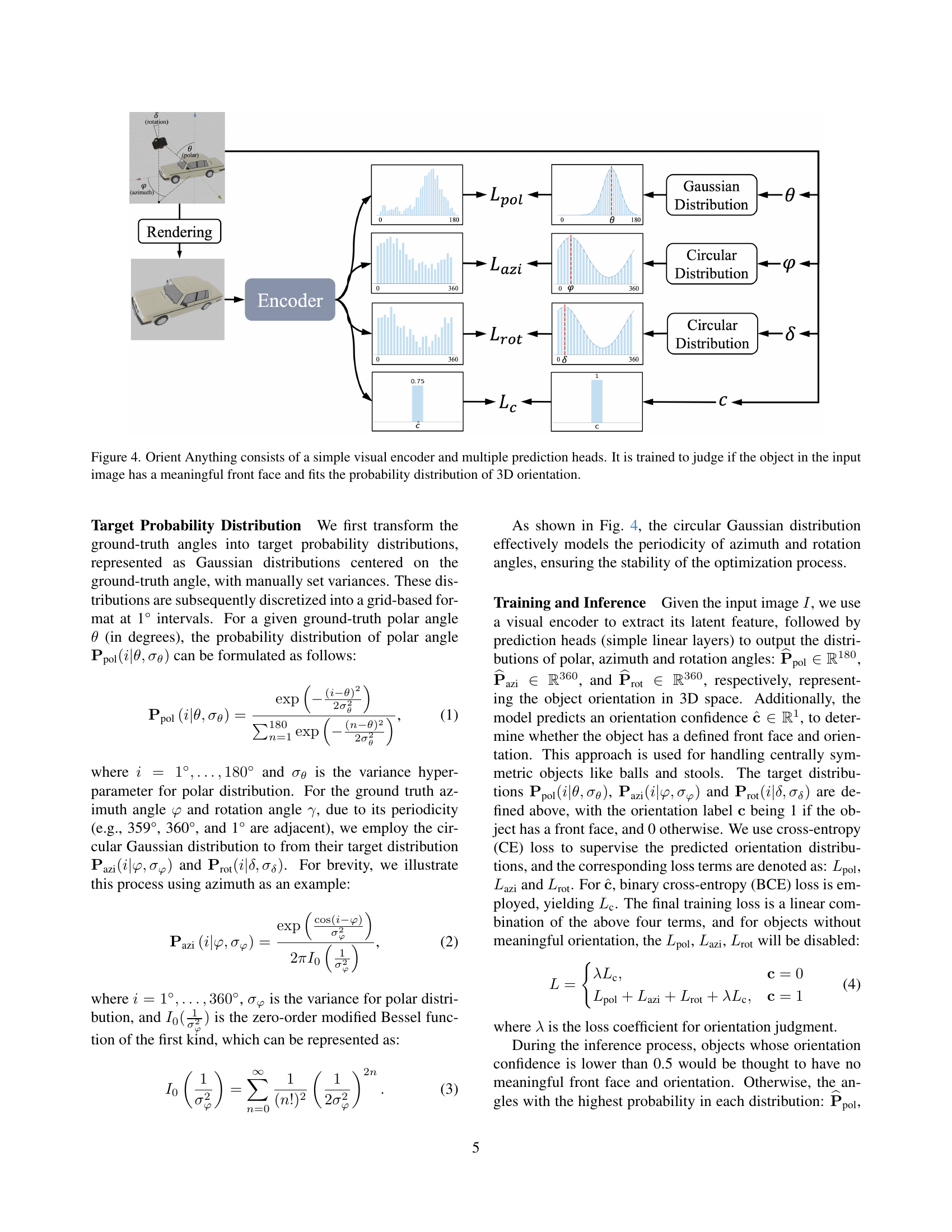

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Orient Anything model. The model takes an input image and processes it through a visual encoder. This encoder extracts relevant visual features. Multiple prediction heads then branch off from the encoder, each responsible for estimating a specific aspect of the object’s 3D orientation (polar angle, azimuth angle, and rotation angle). Crucially, a separate confidence head predicts whether the object in the image has a clearly defined front face. This confidence estimation improves the overall robustness of the orientation prediction by identifying and handling cases with poor-defined frontal aspects. The training process focuses on aligning the predicted orientation parameters to learned probability distributions of these parameters, rather than relying on direct regression, which improves robustness. The model is trained to accurately predict these parameters and whether a front face can be reliably identified in the image.

read the caption

Figure 3: Orient Anything consists of a simple visual encoder and multiple prediction heads. It is trained to judge if the object in the input image has a meaningful front face and fits the probability distribution of 3D orientation.

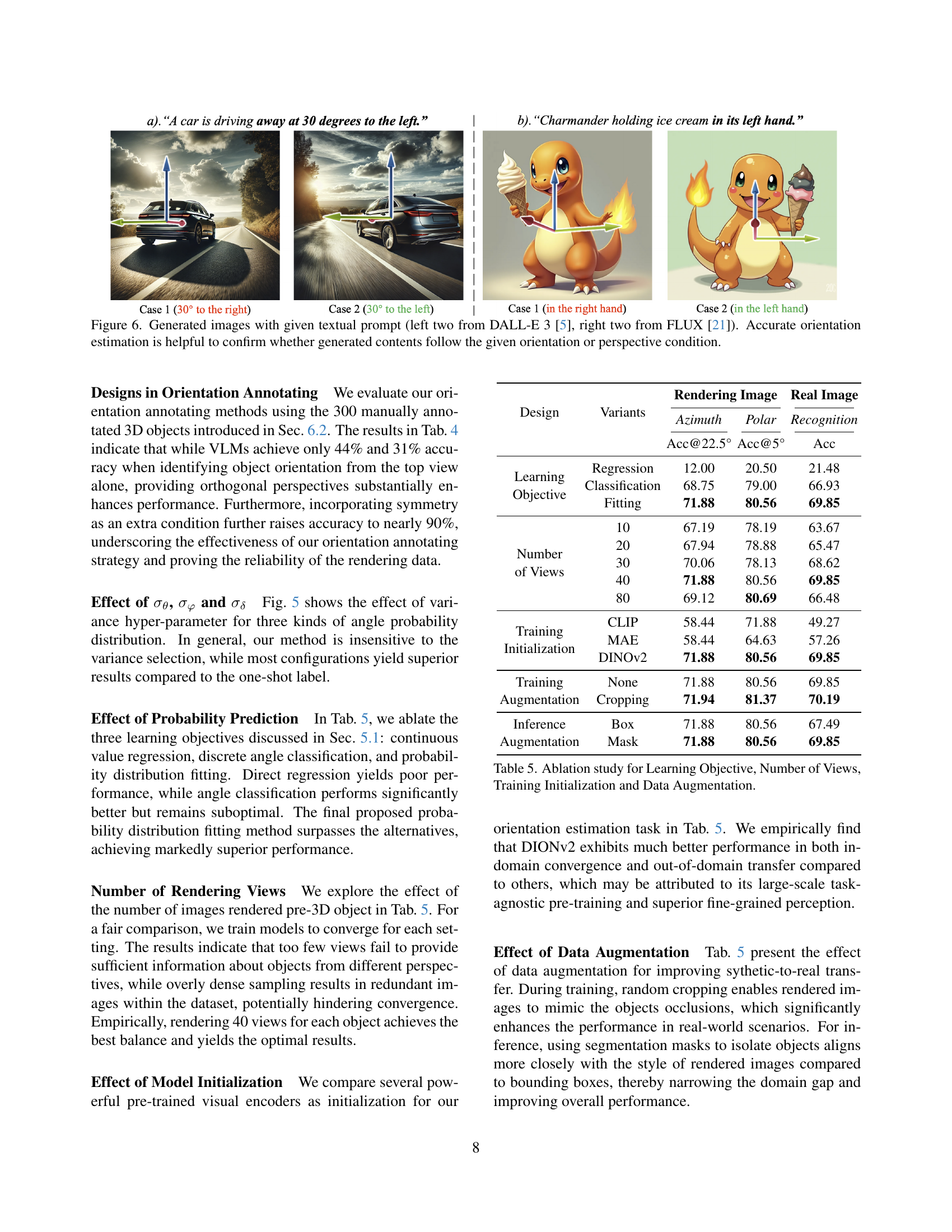

🔼 This ablation study analyzes the influence of variance hyperparameters (σθ, σφ, and σδ) on the accuracy of angle prediction in the Orient Anything model. The x-axis represents the values of each hyperparameter, while the y-axis displays the corresponding accuracy (Acc@22.5° for azimuth, Acc@5° for polar and Acc@5° for rotation). The different colored lines represent the accuracy of different angles. The results demonstrate the model’s robustness and relative insensitivity to the specific choice of these hyperparameters within a reasonable range.

read the caption

Figure 4: Ablation study for hyper-parameter σθsubscript𝜎𝜃\sigma_{\theta}italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_θ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT, σφsubscript𝜎𝜑\sigma_{\varphi}italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_φ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT and σδsubscript𝜎𝛿\sigma_{\delta}italic_σ start_POSTSUBSCRIPT italic_δ end_POSTSUBSCRIPT.

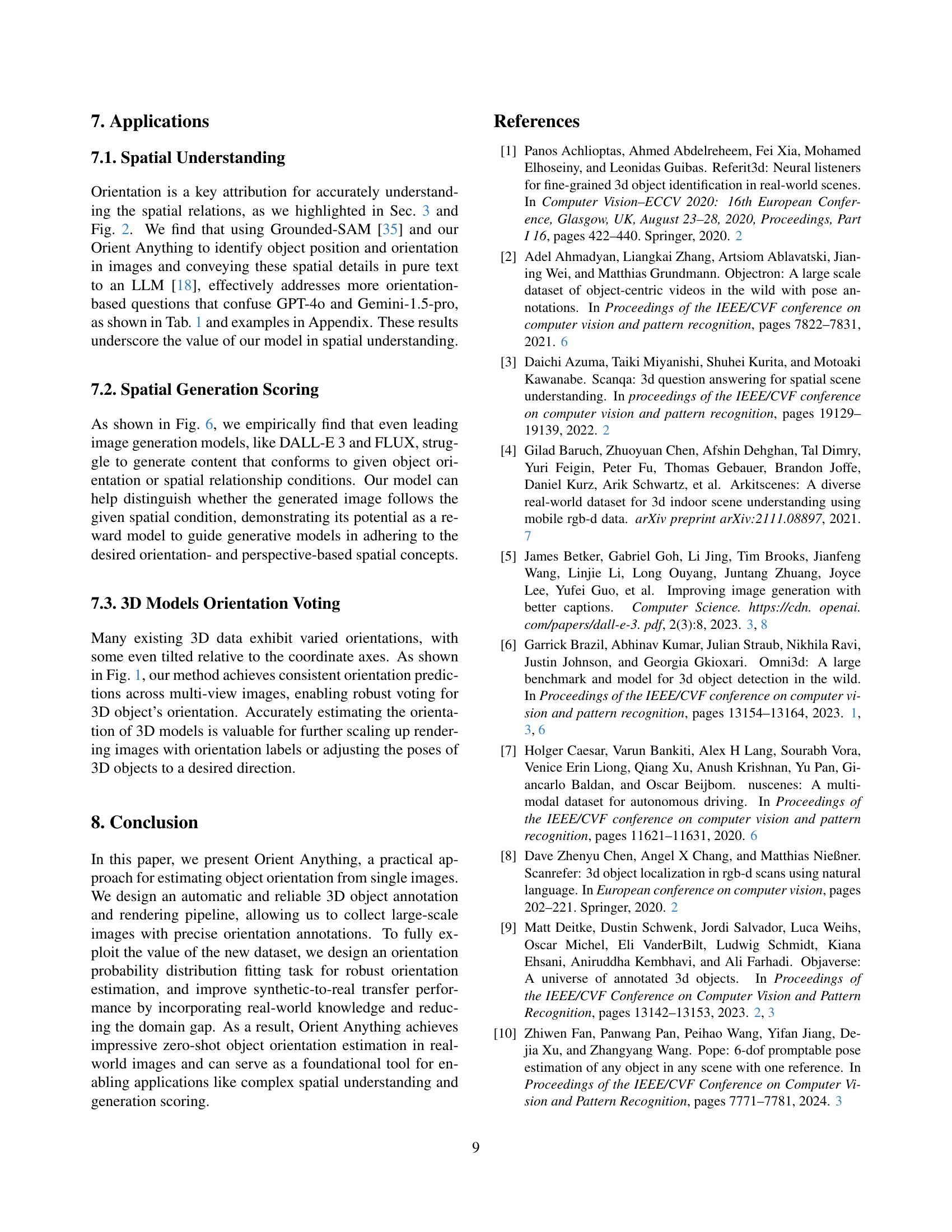

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of accurate object orientation estimation on image generation models. Two pairs of images are shown, each pair generated from the same textual prompt but with differing results. The first pair shows images generated by DALL-E 3, while the second pair is from FLUX. The differences in the generated images highlight how precise object orientation significantly affects the outcome and shows that accurate object orientation estimation (as provided by the model presented in the paper) can be used to verify whether the generated content adheres to the desired orientation and perspective.

read the caption

Figure 5: Generated images with given textual prompt (left two from DALL-E 3 [5], right two from FLUX [21]). Accurate orientation estimation is helpful to confirm whether generated contents follow the given orientation or perspective condition.

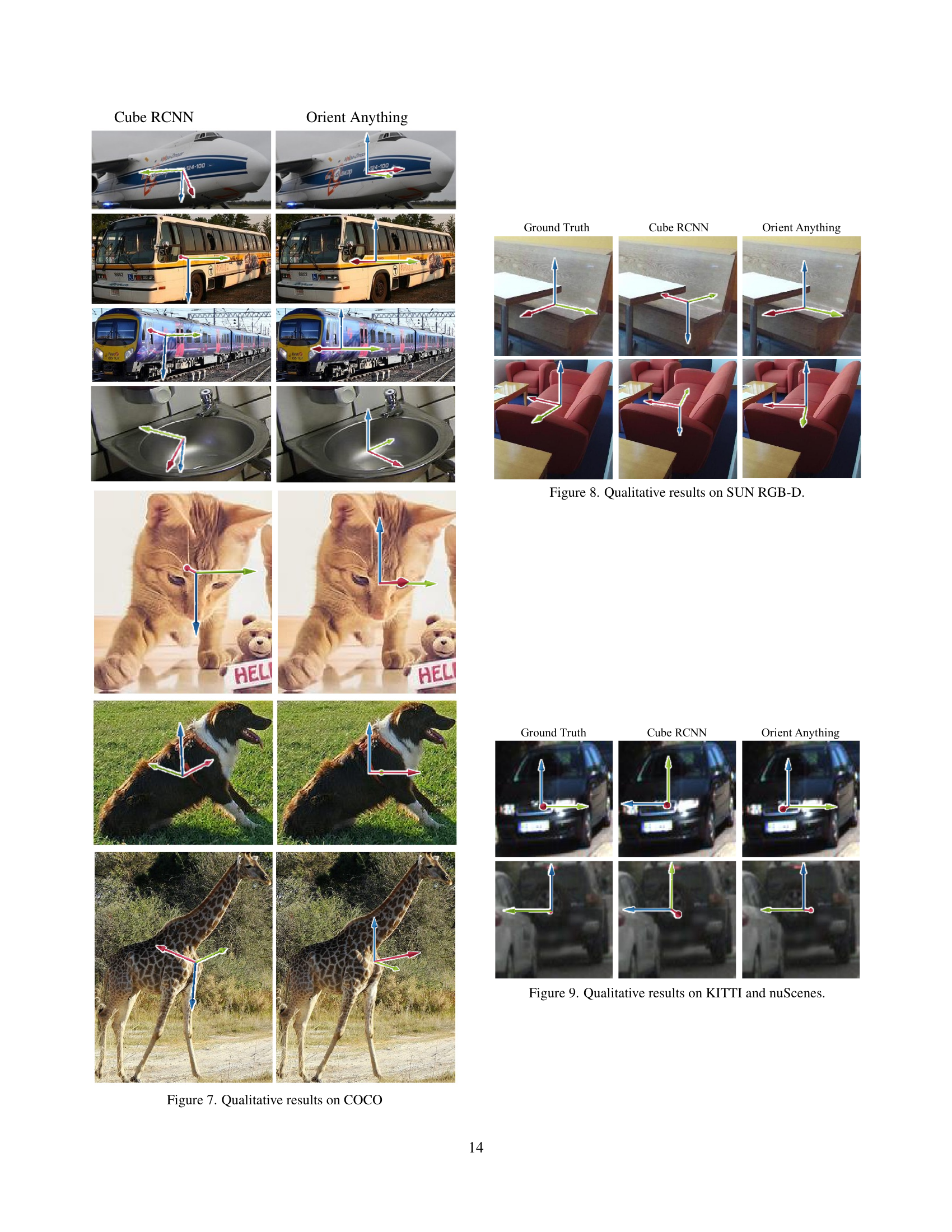

🔼 This figure displays a qualitative comparison of object orientation estimation results on a subset of images from the COCO dataset. For each image, the ground truth orientation is shown alongside estimations produced by the Cube RCNN model and the Orient Anything model proposed in the paper. The visual comparison allows for an assessment of the accuracy and robustness of each model in estimating object orientation across various object categories and viewpoints within the COCO dataset.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative results on COCO

🔼 This figure displays a qualitative comparison of object orientation estimation results on the SUN RGB-D dataset. It shows three columns for each object: Ground Truth (the actual orientation), Cube R-CNN (a previous method’s estimation), and Orient Anything (the authors’ method’s estimation). Each object is shown with its estimated orientation represented by a set of axes; discrepancies between the estimations and the ground truth highlight the performance differences of the methods.

read the caption

Figure 7: Qualitative results on SUN RGB-D.

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of object orientation estimation results on the KITTI and nuScenes datasets. For each dataset, several example images are displayed, showing the ground truth orientation (represented by coordinate axes), the orientation estimated by the Cube RCNN method, and the orientation estimated by the Orient Anything method. The results visually demonstrate the superior accuracy of the Orient Anything model in predicting object orientations.

read the caption

Figure 8: Qualitative results on KITTI and nuScenes.

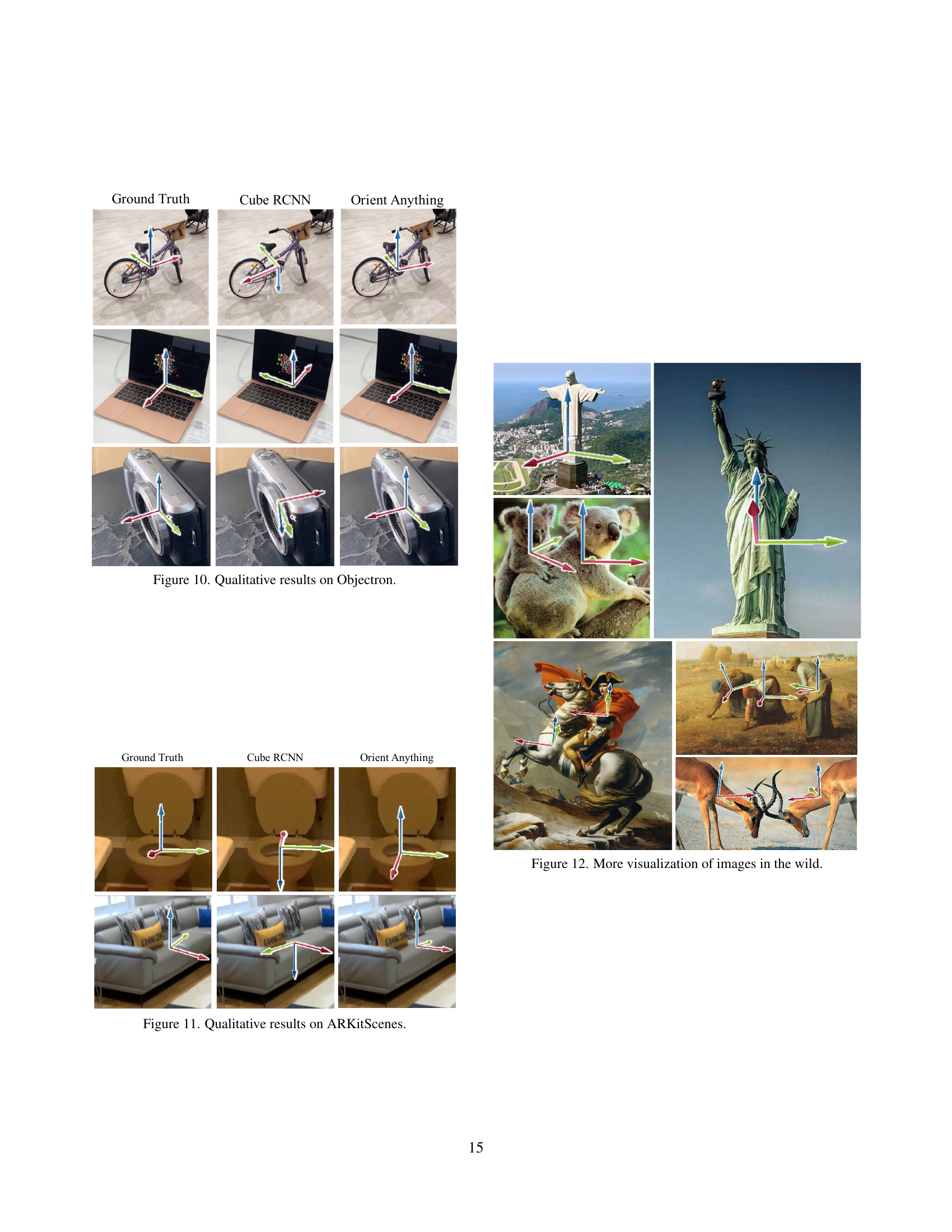

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of object orientation estimation results on the Objectron dataset. For several images of objects, it displays the ground truth orientation (the actual orientation), the orientation predicted by the Cube RCNN model, and the orientation estimated by the Orient Anything model. This visual comparison demonstrates the relative accuracy of the different models in estimating 3D object orientation.

read the caption

Figure 9: Qualitative results on Objectron.

More on tables

| Object | Direction |

|---|

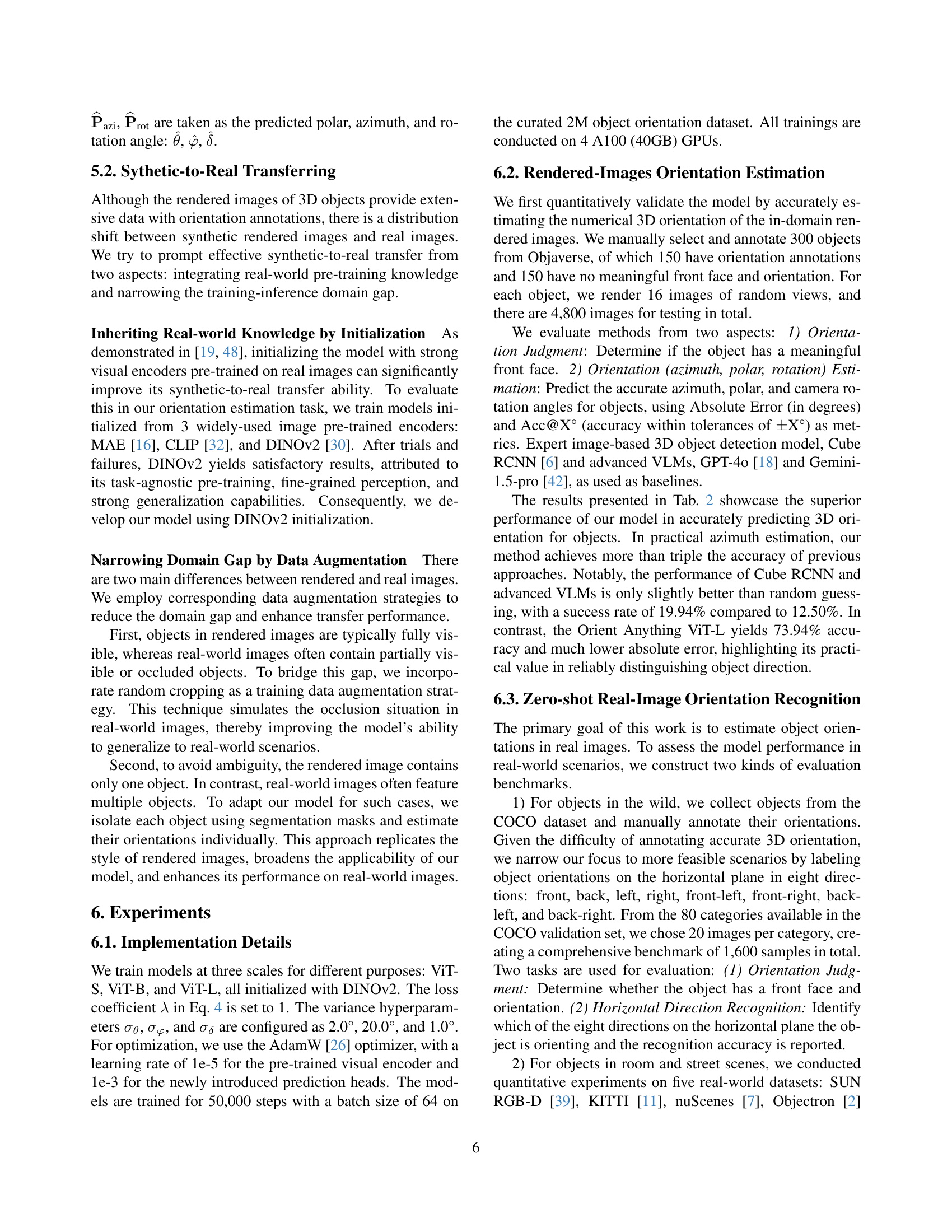

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of object orientation estimation performance on both synthetic (rendered) and real-world images. It evaluates different models, including the proposed ‘Orient Anything’ at various scales (ViT-S, ViT-B, ViT-L), against baselines such as Cube RCNN and large language models (LLMs) like GPT-40 and Gemini-1.5-pro. The metrics used include accuracy of orientation judgment (Does the object have a meaningful front face?), and the absolute error and accuracy at different tolerance thresholds (±5°, ±22.5°) for the estimation of azimuth, polar, and rotation angles. Bold values highlight the best performing model for each metric.

read the caption

Table 2: Orientation estimation on both in-domain rendered images and out-of-domain real images. The best results are bold.

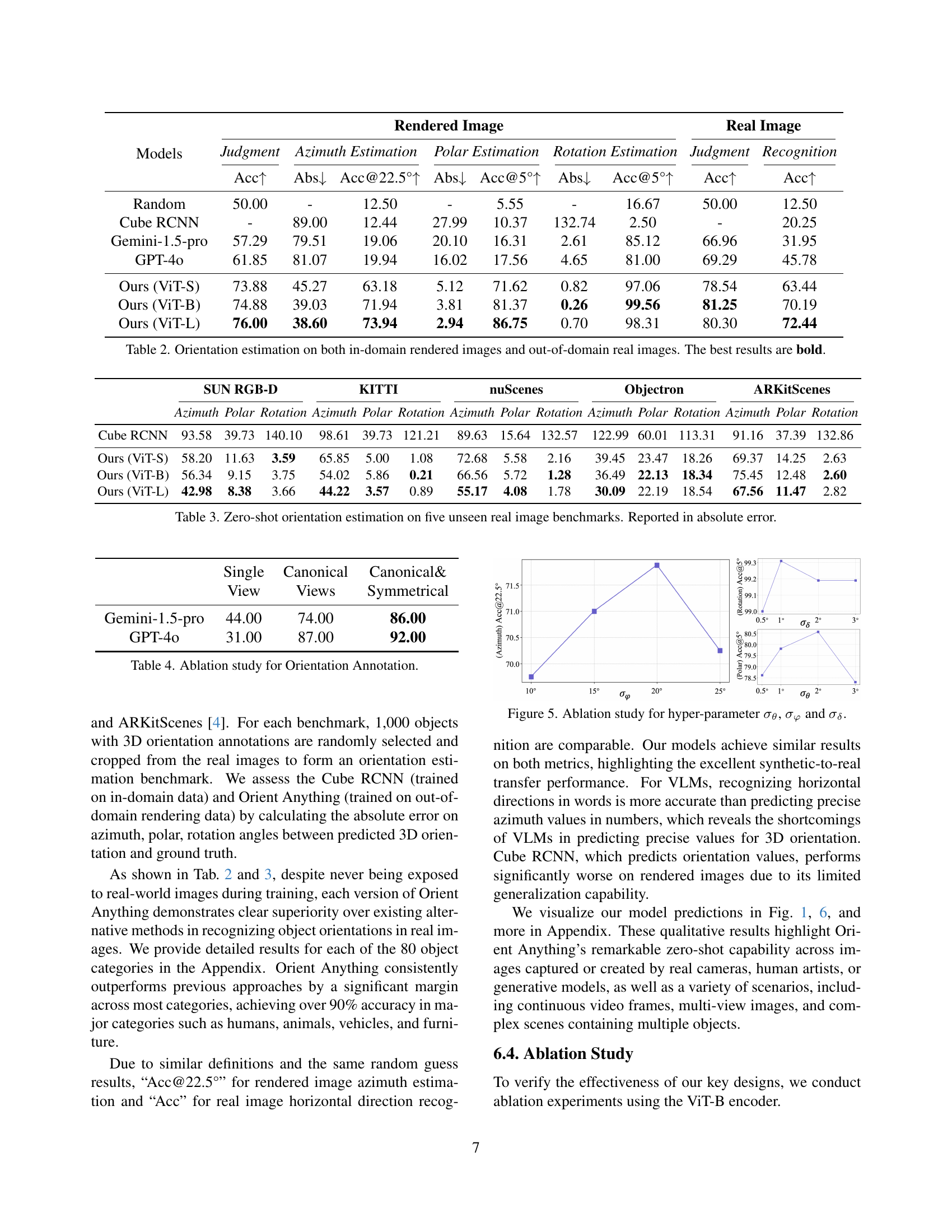

| Spatial | Part |

|---|

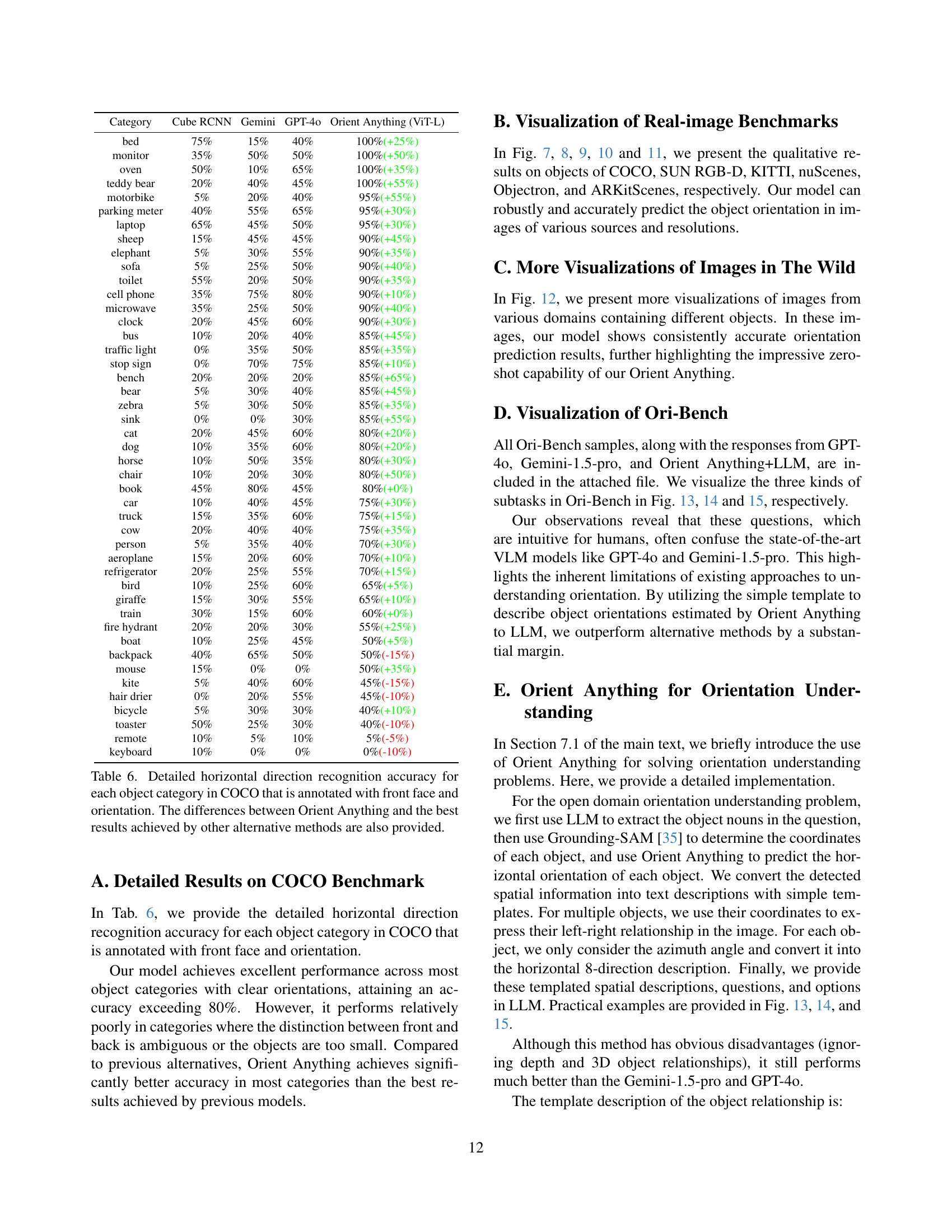

🔼 This table presents the results of zero-shot object orientation estimation on five real-world image datasets: SUN RGB-D, KITTI, nuScenes, Objectron, and ARKitScenes. The model was trained only on synthetically generated data and not on any of these real-world datasets. The performance is evaluated using absolute error in degrees for the azimuth, polar, and rotation angles of the 3D object orientation. Lower absolute errors indicate better performance, showing the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data.

read the caption

Table 3: Zero-shot orientation estimation on five unseen real image benchmarks. Reported in absolute error.

| Spatial | Relation |

|---|

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of different annotation methods on object orientation estimation accuracy. It compares the performance of using a single view, multiple canonical views, and multiple views incorporating symmetry analysis to identify the front face of the 3D objects before rendering images for training. The results demonstrate how combining multiple views, particularly with symmetry analysis, significantly improves the accuracy of orientation prediction.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study for Orientation Annotation.

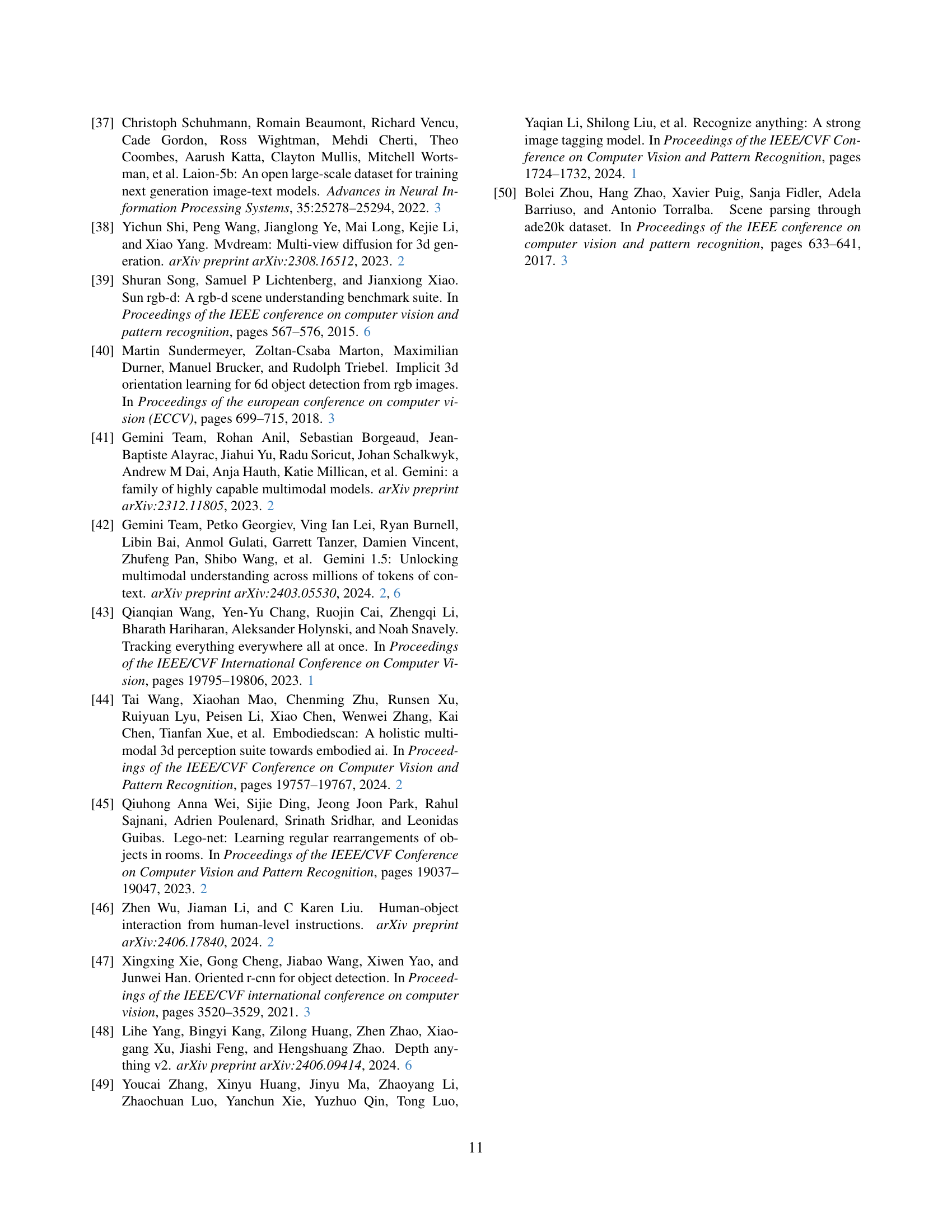

| Models | Rendered Image | Real Image | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Judgment | Azimuth Estimation | Polar Estimation | Rotation Estimation | Judgment | Recognition | ||||

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Acc↑ | Abs↓ | Acc@22.5°↑ | Abs↓ | Acc@5°↑ | Abs↓ | Acc@5°↑ | Acc↑ | Acc↑ | |

| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Random | 50.00 | - | 12.50 | - | 5.55 | - | 16.67 | 50.00 | 12.50 |

| Cube RCNN | - | 89.00 | 12.44 | 27.99 | 10.37 | 132.74 | 2.50 | - | 20.25 |

| Gemini-1.5-pro | 57.29 | 79.51 | 19.06 | 20.10 | 16.31 | 2.61 | 85.12 | 66.96 | 31.95 |

| GPT-4o | 61.85 | 81.07 | 19.94 | 16.02 | 17.56 | 4.65 | 81.00 | 69.29 | 45.78 |

| Ours (ViT-S) | 73.88 | 45.27 | 63.18 | 5.12 | 71.62 | 0.82 | 97.06 | 78.54 | 63.44 |

| Ours (ViT-B) | 74.88 | 39.03 | 71.94 | 3.81 | 81.37 | 0.26 | 99.56 | 81.25 | 70.19 |

| Ours (ViT-L) | 76.00 | 38.60 | 73.94 | 2.94 | 86.75 | 0.70 | 98.31 | 80.30 | 72.44 |

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation experiments conducted to analyze the impact of various design choices on the model’s performance. Specifically, it investigates the effects of different learning objectives (regression, classification, and probability distribution fitting), varying the number of rendered images used per object, different model initializations (using pre-trained weights from MAE, CLIP, and DINOv2), and the use of data augmentation techniques (random cropping and mask-based object isolation). The results help determine which combination of these factors yielded the best performance in terms of azimuth and recognition accuracy.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study for Learning Objective, Number of Views, Training Initialization and Data Augmentation.

| SUN RGB-D | KITTI | nuScenes | Objectron | ARKitScenes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azimuth | Polar | Rotation | Azimuth | Polar | Rotation | Azimuth | Polar | Rotation | Azimuth | Polar | Rotation | Azimuth | Polar | Rotation | |

| Cube RCNN | 93.58 | 39.73 | 140.10 | 98.61 | 39.73 | 121.21 | 89.63 | 15.64 | 132.57 | 122.99 | 60.01 | 113.31 | 91.16 | 37.39 | 132.86 |

| Ours (ViT-S) | 58.20 | 11.63 | 3.59 | 65.85 | 5.00 | 1.08 | 72.68 | 5.58 | 2.16 | 39.45 | 23.47 | 18.26 | 69.37 | 14.25 | 2.63 |

| Ours (ViT-B) | 56.34 | 9.15 | 3.75 | 54.02 | 5.86 | 0.21 | 66.56 | 5.72 | 1.28 | 36.49 | 22.13 | 18.34 | 75.45 | 12.48 | 2.60 |

| Ours (ViT-L) | 42.98 | 8.38 | 3.66 | 44.22 | 3.57 | 0.89 | 55.17 | 4.08 | 1.78 | 30.09 | 22.19 | 18.54 | 67.56 | 11.47 | 2.82 |

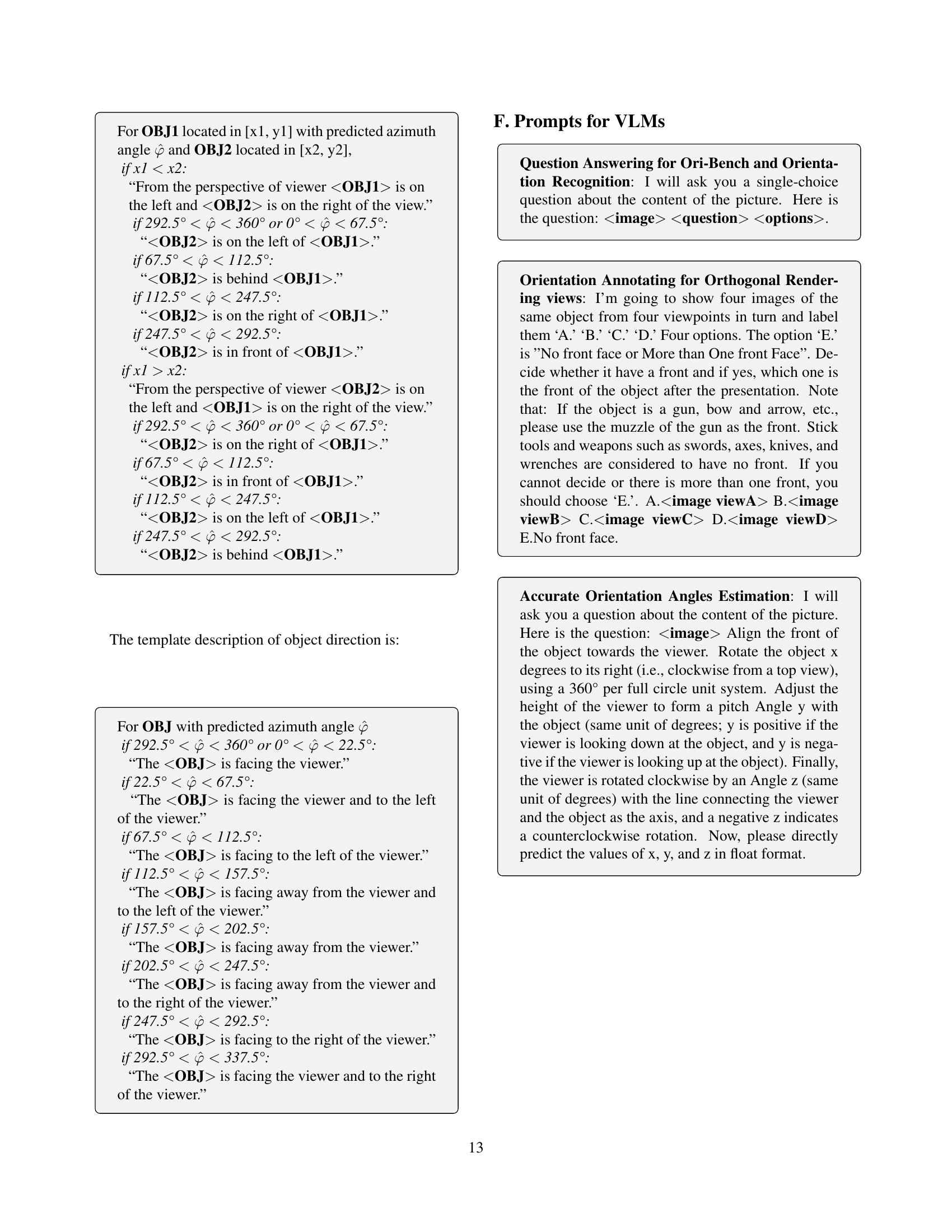

🔼 Table 6 presents a detailed breakdown of the horizontal direction recognition accuracy achieved by Orient Anything and other comparative methods across various object categories within the COCO dataset. Each object category includes data only if it was annotated with a discernible front face and clear orientation. The table highlights Orient Anything’s performance relative to the best-performing alternative method for each category, showcasing its strengths and weaknesses in handling different types of objects and orientations.

read the caption

Table 6: Detailed horizontal direction recognition accuracy for each object category in COCO that is annotated with front face and orientation. The differences between Orient Anything and the best results achieved by other alternative methods are also provided.

Full paper#